World Revolution 2010s - 331 to 384

- 8508 reads

Site structure:

- World Revolution [1]

World Revolution 2010

- 4404 reads

.

World Revolution no.331, February 2010

- 2878 reads

The ruling class can’t avoid cutting our living standards

- 2256 reads

The election campaign is already underway and one of the main points at issue between the parties is the problem of Britain's vast mountain of debt. On January 25 Brown and Cameron held back-to-back press conferences where they addressed the issue head on. Cameron accused the government of "moral cowardice" for failing to take "early action" to deal with the £178 billion budget deficit. He warned that the UK was borrowing £6000 every second. Brown, speaking the day before the official figures announced the ‘end of the recession', countered by arguing that sweeping cuts would put the ‘recovery' at risk.

Brown said: "I am confident that the UK economy is emerging from recession. But there are dangerous global forces...which mean that the world and the UK economy remain fragile. ..That is why we are all agreed around the world that we must reduce our deficits steadily, according to a plan, but that we must do nothing this year which would put the recovery, growth, and jobs at risk. Just as we were right to intervene stop collapsing banks destroying the financial economy...so it is right now we do what is necessary to lock in the economy for 2010" (Guardian 25/1/10)

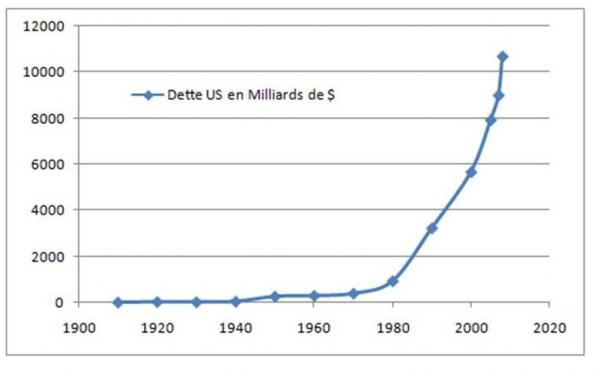

Cameron is right to point out, as he does in the Tories' glossy poster campaign, that "we can't go on like this". The so-called economic boom of the last decade, advertised by Brown and New Labour as proof that the British economy was achieving the highest rates of growth for over two hundred years, was an utter fraud, based on the very flight into debt that plunged it into the ‘credit crunch' of 2008. Despite all the talk of coming out of recession, the underlying brittleness of the UK economy is plainly recognised by the international bourgeoisie. Thus Bill Gross, co-founder of the world's biggest buyer of bonds, the California-based Pimco, warned that Britain is a "must to avoid" for investors and that its economy lies "on a bed of nitro-glycerine". Because it has the "highest debt levels and a finance-oriented economy" it is completely exposed to the financial storms beating at the doors of the world economy (Guardian 27/1/10).

The huge burden of debt building up on the shoulders of the UK economy creates tremendous inflationary pressures which, in the long term, threaten to completely undermine the value of the UK's currency. Cameron is not wrong to say that this state of affairs is untenable.

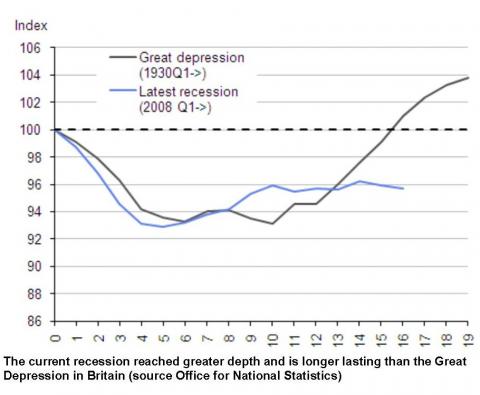

Brown, for his part, is right to say that the ‘recovery' is fragile. The recent recession was the deepest since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The official claim that Britain has emerged from the recession is based on a few months of 0.1% growth. Brown doesn't dwell too much on the fact that in Britain today most ‘growth' is in any case not based on the production of real values but on the semi-mythical realm of financial manipulation and speculation. Nevertheless he is also quite right to say that without the ‘supportive actions' taken by the government, the recession would have been far more catastrophic than it was. Unfortunately the ‘supportive action' has largely involved the kinds of measures that got the economy into its current mess in the first place: international borrowing on a huge scale, doling out money to the consumer to boost demand (the ‘scrappage scheme' which has kept the ailing UK car industry puttering on for a little longer) and, most transparent of all, "quantitative easing": printing money.

Capitalism's historic bankruptcy

That's enough credit to the politicians. They are merely expressing different aspects of the complete impasse reached by the economic system that they both defend: the capitalist mode of production. This is not new and it is certainly not limited to Britain.

The great slump of the 1930s was the first demonstration, on the economic level, that the capitalist system had become an obstacle to social progress: its inherent tendency towards overproduction had created the absurdity of generalised poverty and unemployment despite, and even because of, its enormous productive potential, and this was not a temporary glitch but a genuine crisis of old age, dragging the world into the huge destruction of the Second World War. In the wake of the war the world bourgeoisie recognised that there was no going back to relying on the ‘hidden hand of the market' to restore the economy to health, and it never again abandoned the ‘supportive action' of the state to keep the economy in motion. This was the hey-day of Keynesian polices: in all countries, the resort to debt and state spending was a crucial factor in the post-war economic boom.

But when the world economic crisis resurfaced at the end of the 1960s, to a considerable extent in the form of currency devaluations and inflation, it became clear that ‘supporting' the economy through permanent state intervention also had its down side. And over the past four decades the economic arguments have swung back and forth between ‘Thatcherites' and ‘neo-liberals' on the one hand, warning about the need to slim down the burden of state expenditure, and on the other hand the heirs of Keynes who have argued that such cuts can only revive the 1930s spectre of depression and mass unemployment. This same old argument is being played out by Cameron and Brown today.

In short: capitalism is caught in a cleft stick: if it goes on relying on massive levels of debt and state spending, it heads towards galloping inflation, financial melt-downs - and in the end, the seizing up of the economic machine. But if it makes the massive and immediate cuts demanded by its burden of debt, it ends up in the same place only faster.

Of course things are never so clear cut as in a politician's press conference. Brown and New Labour are no strangers to cuts in public spending and have already accepted that the next Labour government will indeed have to make huge inroads on expenditure on health, education, pensions and the rest. They only differ from the Tories in the pace and choice of cuts to be made (see WR 330, ‘2010: workers face sweeping cuts'). And the Tories, for all their hymns to free enterprise and a smaller state, have never hesitated to use the state machine to bolster up the decrepit capitalist economy, whether through outright nationalisations or more subtle forms of supervision and control.

What is certain is that, whichever party wins the next election, they will loyally serve the dictates of the capitalist economy, which, in a time of crisis, can only mean increasing attacks on the living conditions of the working class, through wage freezes, cuts in welfare benefits, and spiralling unemployment.

Amos 29/1/10

General and theoretical questions:

- Economic crisis [2]

Recent and ongoing:

- Elections [3]

- Attacks on workers [4]

The fraud of ‘humanitarian aid’ in Haiti

- 4708 reads

It is guesswork, but the figures are so far: 200,000 dead, one-and-a-half million homeless, hundreds of thousands of orphans. Just a few days ago, three weeks after the quake, the UN said that it was "still far short" of providing food and water to those who need it. There are now around 20,000 US soldiers in Haiti or offshore, billeted, fed and provisioned. Most onshore are carrying heavy machine guns and grenades with the occasional small box marked "aid" for the TV cameras. In controlling the airport, the US army has prevented massive amounts of help from landing and being distributed. Last week, the US stopped planes from flying out the critically injured for four days at least. This is an operation undertaken not on behalf of the Haitian masses but of US imperialism. The CIA is probably already involved building up its local gangsters once again.

All the usual suspects of the "international community" are involved but it is America that is stamping its feet on the grounds of this misery in order to defend its imperialist interests against all and any rivals who might want to exert their influence. This sickening response by the US also shows the seamless continuity of the Clinton/Bush/Obama administrations in the interests of US imperialism, and particularly the wretched hollowness of Obama.

The general tone of the British media was "security". Just like New Orleans the hurt and damaged masses were seen as a threat. The BBC news vied with Sky to play this up with a reporter giving warnings of violence and "insecurity" over an image that clearly showed laughing young men flattening cardboard boxes to help people make some sort of shelter. It was all about to kick off according to the BBC and its supine reporters and this explained the woeful lack of assistance. Dr. Evan Lyon of a medical aid group which had been working up to 3am every morning in the heart of the capital where reporters feared to tread, said on January 20th: "There's no US military presence, no UN guards, no Haitian police, no violence and no insecurity". Indeed, for the great part, the Haitian masses, even amongst the devastation, showed great spirit, mutual aid and self-organisation (just like in New Orleans and almost every other major disaster) up to the point of organising committees and patrols in Port-au-Prince to keep criminal elements out.

But it's not all bad news; James Dobbins, Clinton's envoy to Haiti said that "This disaster is an opportunity to accelerate oft-delayed reforms". What he means is US imperialism picking up what's left for its own profit. And more good news: while food and medical aid was being turned away by US military control of the airport, a plane-load of Scientologists landed with their healing hands. The Mormons also came, and then the Baptists, who, with the help of the US military, rounded up and abducted who knows how many "orphans", in an operation reminiscent of South American military juntas. Given the modern history of child abuse by the Christian churches and the US/Haitian connections in people trafficking, it's not surprising that the Baptists thought that they could just scoop up dozens of children, without a change of clothes and anything to eat, and spirit them away into God knows what. What's also shown here is the connection between US imperialism and Christian fundamentalism.

"Rebuilding" Haiti is a sick joke. All that will be rebuilt is the security forces, some symbolic structures and what's profitable to the US. Proper rebuilding to protect the masses will not take place because it is not profitable for capitalism. The same will apply to whole swathes of the Caribbean likely to be hit by the continuing subduction where millions more are at risk (of the 600,000 killed by earthquakes in the last ten years, 99% have been killed in urban sprawls).

Aid as imperialism

"Aid" is another lie that is also part of any imperialist strategy. We've seen it in Britain regarding British "aid" to Palestine, which ignores the plight and basic wants of the poor and is mainly directed to building up the security forces. US General Colin Powell said that NGO's were the "force multipliers for the US government". They are sometimes set up, used or infiltrated by the intelligence services. Already groaning under IMF debt, the loans given to Haiti by governments will have to be paid back with interest (while donations freely given go to pay for overpriced goods and services). A recent UN account of 21 disasters over the last 20 years show "a 25% increase in their external debt as a result of aid". In such situations what services there are will be cut and taxes and energy prices will go up in order to pay back the loans.

The poor of Haiti have been remorselessly attacked and abused by the "international community" and particularly the USA. The extent of this disaster shows capitalism's responsibility for it and its total incapacity to be able to deal with its aftermath because profits are its key. This is one of the greatest disasters of our time and our solidarity must go to the Haitian masses.

Baboon 5/2/10.

Geographical:

Recent and ongoing:

Unions use ‘anti-union’ laws against the workers

- 2170 reads

Sometimes we meet people who are concerned that, faced with enormous attacks on its living standards, the working class response is nowhere near the level needed to resist them. This is an understandable concern but we need to approach the question from a different angle. For a start we have to consider the class struggle on an international scale, and if we look around the world we can see many example of open and sometimes massive reactions by workers (see the articles on Turkey [9], Greece [10] and Algeria [11] in this issue for example). But even if we restrict our horizon to the UK, over the last few months we have seen a good deal of discontent among workers in many different sectors and industries facing attacks on pay, pensions, hours and conditions and redundancies - bus drivers in London, Leeds, Rotherham, health service workers in North Devon, London Underground electricians, workers at Fujitsu, South Yorkshire firemen etc. And before that the postal workers' strikes, several strikes in colleges, such as Tower Hamlets. And now Unite is balloting BA cabin crew - again - and the PCS balloting civil servants about strike action.

It takes courage to fight back today

The train of rising unemployment, underemployment, debt, and increased workloads set in motion by the economic crisis certainly demands a response from those facing these attacks, particularly as we know there will be worse to come over the next few years, as much as capitalism can get away with. But in the context of such an open crisis, it can also be harder to struggle, particularly as the bosses can use the threat of unemployment as blackmail against workers, as we saw with postal workers last year and BA workers since December.

When BA cabin crew voted 90% in favour of strike action at the end of last year they did so knowing that the airline is under financial pressure: earlier in the recession it appealed for its employees to work for free one month; they have seen other airlines go into administration, and they know redundancies are coming. In fact it was precisely the fact that over 800 of the workers who voted in the first ballot had been made redundant that gave BA the legal excuse to challenge that ballot.

Civil servants are being balloted by the PCS for strike action against the loss of redundancy protection and compensation terms. It is an open secret that whoever wins the next election will impose cuts in government spending and job losses in the civil service.

Workers face many other difficulties in struggling today. The economic crisis makes bosses more desperate, more intransigent, more bullying. Then there is the law which is used to intimidate workers, and provide an alibi for the unions.

Class struggle is against the law

The injunction against the strike of BA cabin crew called for 12 days over Christmas and New Year, as well as a similar injunction by First London buses, overturning massive votes in favour of action, have led to complaints that "Trade union rights have never been more under threat in this country" (Martin Mayer, Chair of United Left, on libcom.org). In fact Unite has done very well out of the injunction: it has been able to appear very militant while calling off any action.

But injunctions are not the only way the law affects the class struggle. First of all for a strike to be legal there has to be a ballot and notice given to employers. This doesn't threaten the unions but strengthens them while weakening the position of the workers who face long drawn out negotiations, repeated ballots, action called on and off as a walk-on part ‘to force the bosses to negotiate'. Whether in BA or Royal Mail this simply shows the control the union has over the workers.

Then there is the ban on ‘secondary picketing'. This does not threaten the unions either, since they base themselves on negotiation with specific employers. In fact it strengthens them against their members, workers who need to spread their struggles if they are to impose a favourable relation of force. This complements the state policy of breaking up industries into multiple ‘provider' franchises - for instance it would be illegal to link up struggles by bus drivers not only in Leeds and Rotherham, but also in First London and CT Plus in the same city. A situation so ridiculous that Unite is campaigning for a single pay scale for bus drivers across London - allowing the union to appear to want to link these workers without any real links in struggle.

The fact is that when workers are able to go into struggle without ballots, without giving statutory notice to bosses, when they can turn the sympathy of other workers into an extension of the strike to those workers, then they are much more powerful, much more likely to win concessions. The Lindsey strikes a year ago and last June demonstrated that, ending with the announcement of new jobs. What has prevented those strikes being a beacon for the working class today, in the way the Tekel strike is in Turkey, is the difficulty they had with the divisions imposed between British workers employed by British contractors and foreign workers employed by foreign contractors, feeding illusions in nationalism - although these divisions were beginning to be addressed at the end, with appeals to Italian workers for example.

Scab unions?

Those who peddle the notion that unions are the way to defend workers' interests are getting upset at BA setting up the Professional Cabin Crew Council as a ‘scab union' alternative to Bassa (Unite), and also that the pilots' union has declared itself ‘neutral' on the issue of BA training other staff to replace stewards in the event of a strike. Yet "Unite's alternative proposal, "The Way Forward", agrees to allow new crew to work on different pay and conditions. It also agrees to a two-year pay freeze" (https://www.socialistworker.co.uk/art.php?id=20113 [12]). Just like the CWU which called off the postal strikes last year in favour on negotiations on how to bring in the Royal Mail modernisation programme (job losses and increased workloads), Unite is also working to bring in management's cuts in a controlled and negotiated way, a way that won't risk too much resistance. That's what unions are there for.

Alex 5/2/10

Geographical:

- Britain [13]

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [14]

- Union manouevres [15]

Capitalism doesn’t wage war 'democratically'

- 2183 reads

The Chilcot Inquiry is now the 5th inquiry linked to the Iraq War. Six years after the invasion and despite the withdrawal of British forces, the conflict continues to haunt the British ruling class.

This is not surprising, for the Iraq War has been a disaster for the British bourgeoisie. From the start, they were divided over whether to participate in the American misadventure which led to destabilising faction battles. The swift crushing of Saddam's regime was then followed by a long and costly occupation which ended in defeat and humiliation as British troops were increasingly regarded as irrelevant both by the Iraqi government and the local militias. British military weakness has been exposed to the world and its close ties to the Bush administration have left it diplomatically marginalised.

At home, there has been extreme disquiet over the war within the mass of the population. Not only were the lies and distortions of Blair and Campbell exposed almost as soon as they left their offices, the war triggered some of the biggest demonstrations in history. Blair - who in other respects had been an extremely successful prime minister for British capitalism - was permanently damaged by the accusations of deceit.

No wonder, then, that the ruling class wants to learn lessons from the debacle! So we can believe Gordon Brown when he announced to the House of Commons that the aim of the Chilcot Inquiry would be to "strengthen the health of our democracy, our diplomacy and our military" (15.6.09).

Certainly the bourgeoisie aims to recover ground on all three of these terrains but it is on the democratic terrain that they are hoping to make the most impact. After all, airing (some) of their dirty laundry in public reinforces the idea that despite all the "errors" made by this or that politician, in the end the system is democratic.

But the reality is that capitalist states do not wage wars ‘democratically'. Initiating war is decided on the basis of the strategic interests of the national capital and such decisions are taken in the highest echelons of the state machine.

The masses are not consulted in this process - in fact, it is largely acknowledged by military planners that one of the biggest obstacles to military operations is the reluctance of the domestic population. An integral aspect to so-called "information dominance" is convincing the masses to support the actions of the state. This is the reason for the Blair faction's overproduction of "dodgy dossiers" and open prevarication in the run-up to the war.

If these lies were so quickly exposed in some parts of the media, this was simply because the British bourgeoisie wasn't unified in its support for the war. And, indeed, this is part of the issue that the numerous inquiries seek to address: the way that the Blair faction's foreign policy was increasingly detached from the general interests of the state and ruling class as a whole. The internal conflict has done serious damage to the state's future capacity to mislead a population that now regards the ruling class' justifications for humanitarian war with a new cynicism.

Whatever Blair's failures in the eyes of his capitalist compatriots, he continues to provide loyal service to the bourgeois state. His unrepentant and provocative testimony feeds the highly personalised presentation of the war as some kind peculiarity linked to Blair's supposed Manichean vision of good and evil. It is thus "Blair's War", not the war of the British capitalist state and certainly not of capitalism as a whole.

Workers cannot allow themselves to be hoodwinked by this ideological assault. War is the inevitable product of decaying capitalism and the inexorable pressure of competition between nation states. It can only be fought by tackling its root cause: the capitalist profit system itself.

Ishamael 2/2/10

When Britain welcomed Saddam's brutality

Saddam Hussein took power in 1979 in "what the British ambassador described as ‘the first smooth transfer of power in Iraq since 1958', when a group of army officers overthrew the monarchy.

The ambassador noted, however, what this ‘smooth transfer' had involved. Within the first 24 hours of Saddam's rule, ‘21 prominent Iraqis, including five members of the ruling Revolutionary Command Council, executed'.

Britain was confident in Saddam's ability to crush dissent. ‘Strong-arm methods may be needed to steady the ship' wrote a Foreign Office official. ‘Saddam will not flinch'." (FT 30.12.09)

Geographical:

- Britain [13]

Recent and ongoing:

- War in Iraq [16]

- Chilcott Inquiry [17]

Labour and Tory are on the same side in the class war

- 1836 reads

In early December, when Gordon Brown said that Tory plans for inheritance tax had been dreamt up "on the playing fields of Eton" David Cameron knew what he had to do. He pointed out that "I never hide my background" but "if they want to fight a class war, fine, go for it."

With a general election due in the next few months it's time for the political parties to try and look as though they offer alternative approaches to the running of the capitalist economy and its state machine. It's all propaganda to make it look as though there's some sort of choice on offer between the different competing teams.

The ‘class war' language is not very fierce in the hands of Labour and its left-wing supporters, but it has succeeded in convincing a third of voters that the Tories are the party of the ‘upper classes'.

In this campaign you get Ken Livingstone (Guardian 28/1/10) say of a future Tory government that "Those on average incomes, the least well-off, the unemployed, teachers, health workers and others must suffer the effects of a savage attack on social and public spending....These are the real open class-war policies". To his right David Miliband (on the Andrew Marr Show 24/1/10) declared that changes to inheritance tax will bring the "biggest redistribution of wealth to the wealthy in two generations." From his left Socialist Worker (16/1/10) can see that "behind the Eton toff's smiles is the real, vicious face of the Tories".

The trouble with such rhetoric is that for it to have an impact we have to forgot what's happened during the 13 years of the Blair/Brown regime, one that's been in office for twice as long as any previous Labour government.

Livingstone talks of the effects of policies on the unemployed or least well-off and describes them as "open class-war policies" - as though they were something exceptionally terrible in a Tory future. In reality attacks on the conditions of work and life of the working class have been undertaken throughout the life of the Labour government, in continuity with its Tory predecessor, as well as with any future governing team.

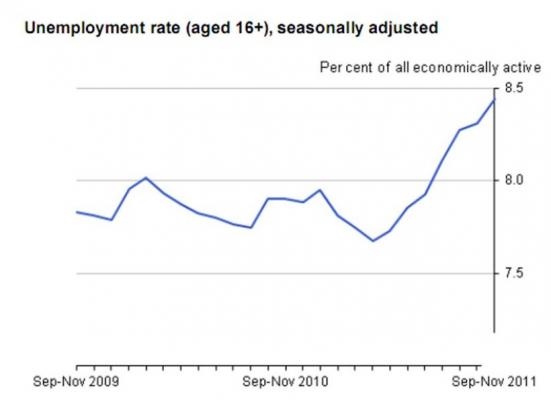

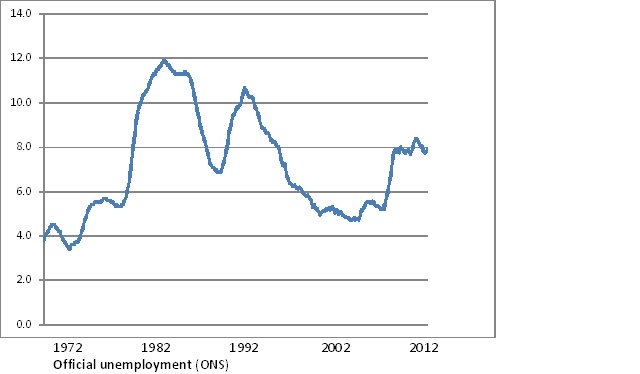

Because Labour retained most of the Tory manipulations of statistics (and added some of their own) it's difficult to know exactly how many million people are out of work in the UK. But this is clearly an area where the working class has been seriously hit and, whatever the official figures, the situation is every bit as bad, if not worse, than under Thatcher in the early 80s. Official statistics put unemployment at about 7.8%, but the official rate for ‘underemployment' (that is those who want to work longer hours, obviously for the money, not for the good of their health) has risen to nearly 10%.

The British economy shrank by nearly 5% in 2009, the worst drop since the 1920s, and it's the working class that has had to pay the price. Officially 1.3 million people lost their jobs in the current recession, and those who have returned to work have typically taken a 30% drop in income. In 2009 10 million people had their pay cut, frozen or got a rise that was below the inflation rate. According to various estimates: 1.7 million people were not made redundant because they took pay cuts or were prepared to work part time; more than a million people are working part time who explicitly want full time work. As for what is to come, 6 million public sector workers face effective pay freezes for the foreseeable future because of Labour measures. A ‘think-tank' has proposed that the middle-aged are left to fester on the dole as it's more important to try and find jobs for younger workers. Suicides are on the rise. Mental health co-ordinators are being introduced into Job Centres who will be able to recommend the quick fix therapy of CBT without a doctor's referral.

The working class is suffering from capitalism's crisis, yet more than 90% of bankers' mega-bonuses still get paid. The gap between the wealth of the rich and the poverty of the poor is much the same as it was 60 years ago. The class struggle exists because different classes have opposing interests. As communists we are open about defending the interests of the exploited class; but both the Tories and Labour (and its left wing hangers on) have long ago proved that in this war, they are firmly in the camp of the ruling class.

Car 2/2/10

Recent and ongoing:

- Elections [3]

Greek workers face brutal austerity package

- 2429 reads

One year ago, there were three weeks of massive struggles in the streets of Greece over the police murder of a young anarchist, Alexandros Grigoropoulos. But the movement on the street and in the schools and universities had great difficulty linking up with the struggles in the workplace. There was only one strike, that of primary school teachers for one morning, in support of the movement, even though this was a time of massive labour unrest, including a general strike, and the links still couldn't be made.

However, in Greece the workers' actions have continued beyond the end of the protest movement up until today. Indeed Labour Minister, Andreas Lomberdos, has been warning that the measures needed to lift the national debt crisis that is threatening to kick Greece out of the euro-zone might result in bloodshed. The new Socialist government is talking of uniting all of the bourgeois parties and is seeking to forge an emergency national unity government that will be able to suspend articles of the constitution protecting the right to public assembly, demonstration and strike.

Even before the government announced its ‘reforms' (read attacks on the working class) to reduce the budget deficit from 12.7% to 2.8% by 2012, there was a large wave of workers' struggles. There have been strikes of dockworkers, Telecom workers, dustbin men, doctors, nurses, kindergarten and primary school teachers, taxi drivers, steel workers, and municipal workers, all for what seems like separate reasons but actually all in response to attacks that the state and capital has already been forced to make to try to make workers pay for the crisis.

Before the austerity package was put forward (and approved by the EU) Prime Minister Papandreou warned that it would be "painful." And on 29 January, before any details were announced, in response to the existing "stability programme" there was an angry demonstration by firefighters and other public sector workers in Athens.

The government's 3- year plan included a comprehensive wage freeze for public sector workers and a 10% reduction in allowances. Estimates put this as equivalent to a pay cut of anything from 5-15%. Retiring government workers will not be replaced, but there is also the prospect of the age of retirement being raised as a way for the state to save on pension costs.

The fact that the state is now being forced to implement even more severe attacks against an already combative working class show the depths to which the crisis has effected Greece. Minister Lomberdos spelled it out very clearly when he said that these measures "can only be implemented in a violent way". However, attacks made against all sectors of workers at the same time open up the real possibility for workers to make a common struggle over joint demands.

If you examine carefully what the unions in Greece have been doing you can see that their actions are keeping the struggles divided. On 4/5 February there was a 48-hour official strike by customs officers and tax officials that shut down ports and border crossing points, while some farmers were still maintaining their blockades. The Independent (5/2/10) headlined "Strikes bring Greece to its knees" and described the action as the "first of an expected rash of rowdy strikes"

This ‘expected rash' of strikes involves plans for a public sector strike and march to parliament to protest against the attacks on pensions by the Adedy union on 10 February ; a strike called by PAME, the Stalinist union, on 11 February; and a private sector strike by the GSEE, the largest union, representing 2 million workers, on 24 February.

Divided in this way the working class is not going to bring the Greek state to its knees. The Financial Times (5/2/10) thought that up to now the "unions have reacted mildly to the government's austerity plans, reflecting a mood of willingness to make sacrifices to overcome the economic crisis" but identified "a growing union backlash against the government's austerity programme." In reality the unions have not neglected their support for the Socialist government, but, with the growing anger being expressed by the working class, they know that if they don't stage some actions then there is the possibility that workers will begin to see through the union charade. At the moment the unions have put on their radical face, broken off dialogue on future plans for pensions and scheduled one and two day strikes on a variety of dates. The unions were indeed willing for workers to make sacrifices, but now they have to take account of the backlash from the working class.

For workers, in the future development of their struggles, there is a need to be wary not only of the unions but of other ‘false friends.' The KKE (Greek Communist Party), for example, which does have some influence in the working class, was, a year ago, calling protesters secret agents of ‘dark foreign forces', and ‘provocateurs'. Now they say that ‘workers and farmers have the right to resort to any means of struggle to defend their rights'. Should they return to their old tune there are other left-wing forces like the Trotskyists who will be there to rally workers against fascists or other right wingers, or against the influence of American imperialism - for anything except workers moving towards taking their struggles into their own hands. With strikes in neighbouring Turkey happening at the same time as strikes in Greece, the unions and their allies will be particularly concerned that all the problems facing workers are portrayed as being specifically Greek, and not affecting workers internationally.

One thing that is distinctive about the situation in Greece has been the proliferation of various armed groups that bomb public buildings but, in the process, create little more than a flaming alternative to mainstream spectacles, while encouraging further state repression. These groups, with exotic names like the Conspiracy of Cells of Fire, Guerrilla Group of Terrorists or the Nihilist Faction, offer nothing to the working class. Workers build class solidarity, consciousness, and confidence through taking part in their own struggles, and developing their own forms of organisation, not through sitting at home and watching bombs set by leftist radicals on TV. The sound of a workers' mass meeting discussing how to organise their own struggle scares the ruling class more than a thousands bombs.

DD (updated by WR 5/2/10)

Geographical:

- Greece [18]

Recent and ongoing:

Algeria: the proletariat is angry

- 1982 reads

Throughout January there have been numerous strikes and street demonstrations in Algeria[1]. Aware that this might be a ‘bad example' and stimulate reflection in a part of the proletariat, especially among immigrant workers who can't help but be affected by these experiences, the French bourgeoisie has given very little media attention to all this.

Demonstrations by unemployed workers in Annaba in east Algeria, by the homeless or badly housed in a whole series of places, workers' strikes in Oran, Mostaganem, Constantine and especially in the industrial suburbs of Algiers, where there was an important level of protest - all this has been subject to the black-out. With the brutal acceleration of the economic crisis, bringing inflation, declining purchasing power and various other attacks, the working class, which has been weakened in recent years, has once again raised its head. There has been a real surge in workers' anger in numerous regions, above all in the heart of the industrial sector. The zone of Rouiba, an industrial suburb to the east of Algiers, seems to have been in the limelight. Everyone remembers that this is where the so-called ‘Semolina revolt' of 1988 broke out[2]. But unlike the latter, which was a rebellion by a starving general population, a revolt of the non-exploiting strata, this time we saw a more specific mobilisation of the proletariat, with its own demands, demands which have always belonged to the workers' movement: for wages, for pensions, against lay-offs.

The workers of the SNVI (Societé Nationale des Véhicules Industriels, formerly SONACOM) were the first to enter the fray. At the end of 2009 the government decided to end the opportunity for its employees to retire early, an undertaking introduced in 1998. In response, the strike spread like wildfire, hitting both public sector and private sector enterprises, with over 10,000 out on strike. Workers at Mobsco, Cameg, Hydroaménagement, ENAD, Baticim and other companies joined the struggle out of solidarity with their class brothers. The workers then confronted major anti-riot police forces in the centre of the town, where the unions had led them[3].

Parallel to these struggles in the capital, on the back of endless and tumultuous revolts by the young jobless, 7,200 workers from the steel complex at Arcelor Mittal in El Hadjar, Annaba, 600 km east of Algiers, came out on strike against the planned closure of the coking plant and the suppression of 320 jobs. Faced with the hardening of a ‘general, and unlimited' strike, and with the evident determination of the workers, the bosses applied to have the strike declared illegal. Here the UGTA union federation was a very useful auxiliary in sabotaging the movement, calling on the workers to go back to work and accept at face value the bosses' promises to invest in the rehabilitation of the coking plant. The reality is that such cuts are inevitable and the idea of rehabilitating the plant is a smokescreen. The trade unions can't say this though!

This social ferment once again shows the growing militancy of workers around the world. WH 23/1/10

[1] Sources: https://www.prs12.com/spip.php?article11934 [20], www.mico.over-blog.org [21], https://www.afrik.com/article18531.html [22] and also the newspaper El Vatan.

[2] In 1988 the ‘Semolina revolt' broke out in response to a brutal rise in basic foodstuffs. It was suppressed by the army at a cost of more than 500 dead. See Révolution Internationale no 314

[3] Following these events, which came after the new tripartite agreement (government, bosses and union) which codified the latest attacks, the boss of the UGTA was denounced as a ‘sell out'.

Recent and ongoing:

'The (im)possibility of revolution'-and the need for militant political discussion

- 2802 reads

"At the next election millions will vote for pro-capitalist political parties that offer little except cutbacks and austerity. Despite economic crisis, climate chaos and disastrous wars, people see no alternative to capitalism - and revolution seems, at best, an impossible dream. Yet all three speakers at this debate believe this situation cannot last indefinitely. Their differing interpretations of anthropology, economics and history each show that a 21st Century global revolution is a real possibility - not just a dream. Could they be right? Come and join the debate."

This was part of the flyer for the meeting on ‘The (im)possibility of revolution?' held at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London on 21st January. The fact that the meeting drew around 100 people is a manifestation of the fact that a growing minority in society is once again asking serious questions about the future being offered to us by the capitalist system. It was addressed by three speakers: the anthropologist Chris Knight; William Dixon, a professor of economics and former member of the old Radical Chains group; and Hillel Ticktin, a Professor of Marxist Studies in Glasgow and editor of the sophisticated leftist journal Critique.

All three presentations made interesting listening. We have previously written about Chris Knight's anthropological theories, centred round the hypothesis that a key element in the emergence of modern human beings was the collective refusal of females to submit to the domination of alpha males, initiating a "human revolution" which installed a truly communal distribution of the products of the hunt. Since the development of our human nature is directly linked to the appearance of primitive communism there is a real potential for mankind restoring, on a higher level, a communist way of living[1].

Both Dixon and Ticktin, examining the history of capitalism in the light of the recent plunge into open economic crisis, put forward the argument that capitalism was signalling its own end. Ticktin in particular insisted that the perspective of the decline of capitalism has always been an integral component of marxism - and that today capitalism is not only in decline but is already showing signs of disintegration, a wearing out of all the traditional means of prolonging its senile existence (finance capital, social democratic reformism, etc). As already mentioned, Ticktin edits a leftist journal and for years he has been a defender of the essentially Trotskyist view that the Stalinist regimes are not capitalist. But it is still significant that the deepening of the crisis is leading him to elaborate a version of the theory of capitalist decline, which is a foundation stone for the advocacy of revolutionary class positions.

Numerous questions and comments were made by those who had come to the meeting. Someone asked why there had not been more working class resistance in the wake of the credit crunch. Another whether the "Bolivarian revolution" in Venezuela offers us a way forward. Another whether capitalism could go green. Unfortunately, there was little possibility of developing any of these questions. The meeting lasted approximately 2 hours. Each speaker was given about 20 minutes to present their positions, thus accounting for the first hour, there was then about 30 minutes for participants to ask questions and make comments ... followed by another 30 minutes for the speakers to respond to what had been said. In such an atmosphere it is extremely difficult for a debate to actually develop. Unsurprisingly, most comments were not followed up or really taken any notice of, but had the feeling of just being individual responses to the presentations.

The shame of it is that this kind of meeting exactly appeals to the kinds of questions that are increasingly being asked by more and more people: What does the present economic crisis mean? What would a future society look like? And how the study of anthropology is able to help us to understand not just past societies but also key aspects of a future one - the issue of solidarity, how to live in harmony with our environment, etc.

However the elephant in the room was the question of how we are to bring about the revolution which was the topic under discussion. In this respect, the limits of the academic approach - albeit an approach which is able to offer many detailed and even profound contributions to historical research - became apparent. People can come to such a meeting and passively listen to ‘experts' giving presentations and responding to questions, without posing the question of militant political engagement, the recognition that capitalism begins to be challenged above all through the conscious, collective action of workers and through the participation of revolutionary organisations within that action. Debate and discussion are the lifeblood of revolutionary organisations and the working class struggle generally. However, it is the framework in which such debates are held that determines their effectiveness in helping the development of consciousness.

Graham 05/02/10

[1]. https://en.internationalism.org/2008/10/Chris-Knight [25]

People:

- Chris Knight [26]

- Hillel Ticktin [27]

- William Dixon [28]

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [29]

Yemen, Somalia, Iran: the drive to war accelerates

- 2440 reads

Barack Obama's war against America's ‘mortal enemy', al Qaida, is growing in scale. Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq have already been drawn into this battle to ‘defend civilisation'. We now have to add Yemen, Somalia and, to a lesser degree, Subsaharan Africa, all of which have also been the scene of ‘targeted raids' and other incursions. Meanwhile the policy of the ‘open hand' towards Iran, announced at the beginning of Obama's presidency and geared towards a diplomatic approach to Iran's nuclear ambitions, is now once again giving way to the clenched fist :

"The US is dispatching Patriot defensive missiles to four countries - Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Kuwait - and keeping two ships in the Gulf capable of shooting down Iranian missiles. Washington is also helping Saudi Arabia develop a force to protect its oil installations.

American officials said the move is aimed at deterring an attack by Iran and reassuring Gulf states fearful that Tehran might react to sanctions by striking at US allies in the region. Washington is also seeking to discourage Israel from a strike against Iran by demonstrating that the US is prepared to contain any threat" (Guardian 1/2/10).

The USA, already completely bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, is thus continuing its headlong plunge into war by stepping up its military presence in this entire region.

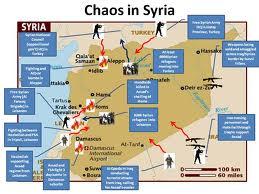

The strategic importance of Yemen and Somalia

A simple question is posed: what interest do these two countries represent for American imperialism? Yemen, with its very meagre oil resources, has become a real desert, ravaged by years of war. In 1990, the Arab republic of North Yemen and the Popular Democratic Republic of South Yemen got together to form the Republic of Yemen. Since then there has been non-stop war. The Yemeni population of 21 million is one of the poorest in the world. The country is on the verge of cracking up.

As for Somalia, the situation is even worse. This country of 9 million inhabitants is a vast killing field. War has been raging for more than 20 years. The population is in almost permanent flight from all kinds of armed gangs and desperate for shelter and food. The last government to date doesn't even control the whole of its capital city, Mogadishu. The so-called transition government is locked in a conflict with the Islamist groups: Hizbul Islam, led by Sheikh Aweys, a former mentor of the current president; and the al-Shabab group which is linked to al-Qaida. In the regions of Somaliland and Puntland, the search for any semblance of order and stability has been totally abandoned. The fishermen of the coast have turned to piracy to survive, the seas there having been infested by nuclear waste from various European naval ships. Since the collapse of the government in 1990, the USA has been in military occupation of part of the terrain. This was pushed through by the ‘Restore Hope' operation in 1992. This was also the time when France's Bernard Kouchner arrived in Somalia carrying sacks of rice on his shoulder, discretely followed by some French army contingents!

But what is of such interest to imperialist predators like the USA and many others? To respond to this question, you only need to look at a map. Between Somalia and Yemen lies the Gulf of Aden, which is the maritime route towards the Red Sea and the oil fields of the Persian Gulf. The Straits of Ormuz are therefore one of the most surveillanced and coveted areas in the world. More than 20% of the world's oil supplies and more than half the world's oil tankers go through this route. This is also the route through which Chinese imperialism, which is becoming more and more aggressive, is infiltrating towards Mozambique, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar. In this period of deep economic crisis and sharpening imperialist tensions, controlling the supplies of black gold and the main maritime routes is indispensible for any imperialist power that wants to play a world role. It is a vital weapon of war.

This is why the failed attempt to blow up an American passenger plane heading to Detroit from Amsterdam, carried out on Christmas Day by the Nigerian Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab in the name of al-Qaida, has made it possible to reopen the Pandora's Box of the struggle against terrorism. The fact that this young Nigerian had stayed in Yemen and had been trained there by al-Qaida was the perfect pretext. The reaction was swift. "Washington and London expressed their will to cooperate further in the anti-terrorist struggle in Yemen and Somalia. London and Washington envisage financing a special unit of anti-terrorist police in Yemen and giving added support to the Yemeni coast guard, Downing Street said" (Jeune Afrique, 26/1/0). French imperialism didn't want to be left out and immediately made the same kind of declaration. The president of Yemen, Ali Abdullah, has been in power for 30 years and is an ally of the US. The American army has already sent him missiles and special troops. With the Houti guerrillas in the north being supported by Iran, war is raging, for example round the town of Sa'dah. In a country in such a state of instability, only a direct military presence can serve the needs of a major power. A new American base was already set up there last year, under the banner of anti-terrorism, and the arrival of extra US troops, who will be facing rebellions in both the North and the South of the country, is yet another step by US imperialism into a quagmire with no escape, as in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Iran problem and the accelerating decline of US leadership

The recent deployment of tens of thousands of extra US troops in Afghanistan shows very clearly that America is not capable of winning this war. The fact that Pakistan is one of the major prizes in this conflict has resulted in the destabilisation of the Islamabad government, its army and its national unity in a region where Indian and Chinese imperialism are also very active. But although the US is being strongly challenged by China, it has also been reduced to asking it, as well as Russia, for help in dealing with the growing ambitions of Iran, which has been strengthened by the destruction of the Saddam regime in Iraq and which is seeking to extend its influence into Lebanon, southern Iraq, Yemen and elsewhere, as well as taking steps towards equipping itself with a nuclear arsenal : "Two high US officials went to China before the presidential visit and warned the Chinese that if they didn't support Washington over the Iranian dossier, Israel would go onto the attack, provoking chaos in the oil supplies which are so vital to China. Iran is the country's second biggest oil supplier and Chinese enterprises have invested massively there. To loosen this constraint, the USA also proposed that the Chinese should reduce their dependence of Iranian supplies. The Americans' proposals seem to have been listened to. For the first time in a number of years, China voted in favour of the International Atomic Agency condemning Iran" (J Pomfret and J Warrick of the Washington Post, Counter Info 27/1/09). Russia is thus also being courted by the US, which needs their help: this is why they suspended their programme of installing missiles in Poland and the Czech Republic. But Russia and China both have good reasons to continue encouraging Tehran's destabilising role in the Middle East.

These appeals for help are also a real admission of weakness. After the attack on the Twin Towers in 2001, George Bush Jnr launched the USA into a war campaign, striking out almost alone in a bid to demonstrate the absolute military supremacy of the world's leading power. This whole campaign has been a failure. But the ‘new' Obama policy, which uses different language but which is just as warlike, won't produce anything better, either for American imperialism or, obviously, for humanity.

Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, and now Somalia and Yemen, the war waged in the name of the struggle against radical Islamism is expanding. Each blood-stained step forward by American imperialism exposes its growing powerlessness. In Afghanistan, the USA's inability to defeat the Taliban has become increasingly evident, with mounting calls to negotiate with its more ‘moderate' elements. In Iraq, bomb outrages continue non-stop, the most recent being a deadly suicide bombing of a Shia religious procession at the end of January, leaving sores of dead and maimed. For the USA, Yemen can only be a new Iraq or a new Afghanistan. For the population of these countries, the worst is yet to come. Imperialism in decay sows death wherever it goes. For the working class of all countries, whether or not directly affected, this reality is increasingly evident and intolerable.

A/Rossi 27/1/10

Geographical:

- Somalia [30]

- Middle East and Caucasus [31]

People:

- Barack Obama [32]

Recent and ongoing:

- Imperialist Rivalries [33]

- Yemen [34]

World Revolution no.332, March 2010

- 2795 reads

Greece, Spain, Portugal…The state is bankrupt

- 8592 reads

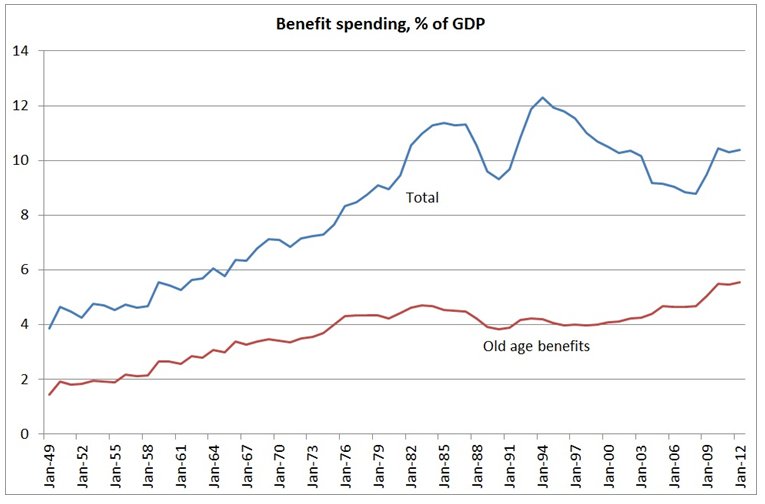

Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland, France, Germany, Britain...everywhere the same crisis, everywhere the same attacks. The ruling class is revealing its true colours. Its cold and inhuman language boils down to the same basic message: ‘if you want to avoid the worst, if you don't want total economic break-down, you are going to have to pull in your belts like never before'. Obviously not all the capitalist states are in the same situation of uncontrollable deficit and cessation of payment, but all know that they are heading inexorably in that direction. And all of them make use of this reality to defend their sordid interests. Where are they going to find the money to make at least a small dent in the monstrous deficits? You don't have to look far. While some of them have already launched the offensive against the working class, all of them are at least preparing the ground ideologically.

Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain: a foretaste of what is in store for the whole working class

The Greek austerity plan aimed at reducing public debt is both cynical and brutal. The country's finance minister said that "the civil servants must show their patriotism and give an example". In other words they must accept without question a cut in their wages and the removal of benefits; they must put up with the fact that posts made vacant by retirement won't be replaced, that the retirement age is pushed beyond 65 and that they can be made redundant and thrown away like used kleenex. All to defend the national economy, which belongs to the exploiter's state, the bosses and all those who suck the workers' blood. All the national bourgeoisies of Europe are playing an active part in this drastic austerity plan. Germany, France, Britain and Spain are all paying close attention to the policies being put into place by the Greek state. They want the following message to be broadcast to the proletariat on an international scale: 'look at Greece: its people are forced to accept sacrifices to save the economy. You are going to have to do the same thing yourselves'.

First it was the households of America, then the banks, then the big companies, now the state itself is faced with bankruptcy. Its response: orchestrate pitiless attacks on living standards. In the months ahead there will be a draconian reduction of public sector workers' jobs - in Britain they are already talking about 250,000 local government jobs going, and that's even before the elections have been got out of the way. These cuts will of course impact severely on everyone's living standards. For the bourgeoisie, the workers are like cattle who they can take to the slaughterhouse when their interests dictate it. The situation is identical in Portugal, Ireland, and Spain: the same savage plans, the same catalogue of anti-working class measures. And it's not just in Europe. In the most powerful country in the world, the USA, unemployment stands at 17%; 20 million people have joined the ranks of the ‘poor' and 35 million survive thanks to food vouchers. And every day that passes brings a further dive into misery.

States faced with their own insolvency

How did we get to this? For the bourgeoisie as a whole, and especially its left wing fractions, the response is very simple. It's all the fault of the bankers and mastodons like Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan etc. It's true that the financial system has gone mad. It can see nothing beyond its immediate interests - it's the old ‘after me, the deluge' approach. It's now known that it was the big banks which, in order to get more money, accelerated Greece's cessation of payments and bet on its bankruptcy. They will no doubt do the same thing tomorrow with Portugal or Spain. The great world banks and financial instructions are indeed a bunch of crooks. But these ultimately suicidal policies of the world of high finance are not the cause of the crisis of capitalism. On the contrary, they are its effects - which, at a certain stage, have become an aggravating factor in it.

As usual, the bourgeoisie of all stripes is lying to us. It is trying to create a vast smokescreen. And it is playing for high stakes. It has to do everything it can to prevent workers making the link between the growing insolvency of the banks and the bankruptcy of the entire capitalist system. Because that's the true state of affairs: capitalism is dying and the madness of its financial sphere is one of the symptoms.

When the crisis broke out with such a bang in the middle of 2007, the failure of the banking system was evident everywhere, especially in the USA. This situation was simply the product of decades of the policy of generalised debt, encouraged by the states themselves in order to create the markets needed to sell commodities. But when the individuals and companies could no longer repay their debts, the banks found themselves on the edge of collapse, and the capitalist economy with them. It was at this point that the states had to take over a large part of the debts of the private sector and come up with monumental and costly plans to try to limit the recession.

Now it's the states themselves which are in debt up to their necks, unable to cope and without having saved the private sector. They are staring bankruptcy in the face. Of course a state is not a company: when it can no longer pay its debts, it can't just lock the doors. It can go for more debt at higher rates of interest, print more paper money, dip into everyone's savings. But a time comes when the debts (or at least the interest on them) have to be paid back, even by a state. To understand this, we only have to look at what's happening now with the Greek, Portuguese, and even Spanish states. In Greece the state has tried to finance itself by borrowing on the international markets. The results of this are now with us. The whole world, knowing perfectly well that the Greece is insolvent, offered it very short term loans at rates of interest of over 8%. It goes without saying that that such an economic situation is insupportable. What solutions are left then? Equally short term loans from other states like Germany and France. But even if these states can temporarily put something into Greece's coffers, they won't then be able to bale out Portugal, then Spain, and maybe even Britain. They will never have enough liquidity. These policies could only end up crippling them financially. Even a country like the USA, which can count on the international domination of the dollar, is seeing its public deficit growing all the time. Half of all America's states are bankrupt. In California, the state government is no longer paying its public servants in dollars but with a kind of local money, vouchers which are only valid on Californian soil!

In short, there is no economic policy that can pull all these states out of their insolvency. In order to put things off, they have no choice but to make big cuts in their ‘expenses'. This is precisely what Greece is now doing, along with Portugal, Spain, and soon all the rest. These will not be like the austerity plans the working class has been through regularly since the end of the 1960s. Capitalism is going to have to make the working class pay very heavily for the survival of the system. The image we need to have in mind is that of the soup kitchens of the 1930s. This is the future that the crisis of capitalism is preparing for us. In the face of growing poverty, only the massive resistance of the world working class can open a perspective of a new society without exploitation, commodity production and profit, which are the real roots of today's economic crisis.

Tino 3/3/10

Geographical:

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [29]

- Attacks on workers [4]

Workers respond to austerity attacks

- 3797 reads

The eyes of the world ruling class are on Greece today, not only because the failure of its economy is a harbinger of what lies in store for the rest of Europe, but above all because the bourgeoisie is well aware that the social situation in Greece is a real powder-keg.

In December 2008, the country was shaken by a month-long social uprising, led mainly by proletarian youth, following the police murder of a young anarchist. This year the austerity measures announced by the Socialist government - which include wage cuts for public sector workers, a delay in the retirement age and tax increases on alcohol and cigarettes - are threatening to ignite an explosion not only among the students and the unemployed but also the main battalions of the employed working class. It is thus of the utmost importance - for the bourgeoisie - to be able to provide examples of workers tamely accepting austerity measures ‘for the good of the economy'. Unfortunately for them, this is not exactly the scenario being played out in Greece at the moment.

In the two weeks leading up to the announcement of the government package, there had been a widely followed 24 hour general strike against the threatened austerity measures, a longer running strike by customs officials which paralysed exports and imports, as well as actions by government employees, fishermen and others.

The events following the announcement of the package at the beginning of March showed even more clearly that there is a clear and present proletarian danger.

"Just hours after the announcement of the new measures, layed-off workers of Olympic Airways attacked riot police lines guarding the State General Accountancy and have occupied the building, in what they call a open-ended occupation. The action has led to the closing of Athens' main commercial street, Panepistimiou, for long hours.

On Thursday morning, workers under the Communist Party union umbrella PAME occupied the Ministry of Finance on Syntagma square (which remains under occupation) as well as the county headquarters of the city of Trikala. Later, PAME also occupied 4 TV station in the city in Patras, and the state TV station of Salonica, forcing the news broadcasters to play a DVD against government measures.

On Thursday afternoon, two protest marches took to the streets of Athens. The first, called by PAME, and the second by OLME, the teachers union and supported by ADEDY. The latter gathered around 10,000 people despite less than 24h notice, and during its course limited clashes developed with the riot police which was pilled [sic] with rocks outside the EU Commission building. Also two protest marches took to the streets of Salonica at the same time. A protest march was also realised in the city of Lamia.

Finally, the party offices of PASOK in the town of Arta were smashed by what it is believed to be people enraged by the measures" (from the blog by Taxikipali a regular contributor to libcom.org: https://libcom.org/news/mass-strikes-greece-response-new-measures-04032010 [38]).

Soon after these lines were written, another post by the same blogger wrote about the long running battles that broke out at the Athens demonstration following a police assault on Manolis Glezos, an icon of the anti-Nazi resistance during the war (https://libcom.org/news/long-battles-erupt-athens-protest-march-05032010 [39]). At the time of writing a whole number of further strikes and demonstrations have been planned.

Unions radicalise to keep control

In December 2008 the movement was largely spontaneous and often organised itself around general assemblies in the occupied schools and universities. The HQ of the Communist Party (KKE) union confederation was itself occupied, expressing a clear distrust of the Stalinist union apparatus which had frequently denounced the young protesters both as lumpen-proletarians and spoiled sons and daughters of the bourgeoisie.

Today however the KKE has shown that it is still a vital instrument of bourgeois rule by taking charge of the strikes, demonstrations and occupations. There has certainly been overt rage against the Socialist GSEE union, which is seen as a direct tool of the PASOK government: Panagopoulos, the boss of GSEE, an umbrella of private sector unions, was physically attacked at the demo and had to be rescued by the Presidential Guard, but so far the KKE and its unions have been able to present themselves as the leading and organising force of the movement.

The danger for the Greek bourgeoisie is that if the present mood of defiance continues, the workers will begin to see beyond this false radicalism, and that in seeking to take their struggles beyond the set-pieces imposed by the union machinery, workers will be compelled to take things into their own hands, adopting the ‘assemblyist' model which began to take shape in December 2008.

But even in its present stage, the struggle in Greece is a real worry for the international ruling class as a whole. Similar austerity measures in Spain, centred round a two years postponement of retirement age, provoked angry demonstrations in a number of cities, while in Portugal, on 4 March (the same day as the Athens demonstrations) hospitals, schools and transport were severely disrupted as public sector workers staged a 24-hour strike against a wage freeze and other austerity measures. The stoppage also hit courts, customs offices and refuse collections.

In France, there have been expressions of active militancy among teachers, railway workers, shop employees and oil workers. In the latter case, solidarity strikes spread from one refinery to another, and across different oil companies, after threats to close the Total refinery near Dunkirk.

In sum, the mood of fear and passivity which tended to reign when the economic crisis took a dramatic turn for the worse in 2008 is beginning to be replaced by one of indignation, as workers openly ask: why should we pay for capitalism's crisis?

Of course these stirrings of class consciousness can be and are being sidetracked into ideological dead ends, notably through the world-wide campaign to blame it all on the bankers or on ‘neo-liberalism'. In Greece, the fact that the German bourgeoisie was most pointed in its refusal to bale out the Greek economy led the PASOK government to play on the anti-German sentiments that still survive from the Nazi occupation.

But reality and ideology inevitably clash. The crisis is evidently world wide and everywhere the rulers are calling for sacrifices to save their moribund system. In resisting these calls, workers in all countries will grow to recognise their common interests in opposing and ultimately overturning the system that exploits them and drives them towards poverty.

Amos 6/3/10

Geographical:

Recent and ongoing:

BA, civil servants, workers face union divisions

- 1793 reads

In the lead-up to the General Election all serious factions of the bourgeoisie have openly put forward the need to introduce the most savage cuts, most of them aimed at the public sector. As opposed to the 1997 election slogan of New Labour - "things can only get better" - things got bad and are getting worse. Already we are faced with an all-out attack on pay and conditions. Many different sectors of workers have faced stringent attacks, provoking different struggles to defend jobs and wages, the postal workers and oil refinery workers being among the most notable examples.

Today, we are seeing sectors of workers less known for their tradition of militancy being forced into strike action to defend themselves. British Airways cabin crew and civil service workers have voted for strike action.

On Monday and Tuesday 8/9 March up to a quarter of a million civil service workers could strike. These strikes follow a ballot which saw a vote for strike action and a vote for an overtime ban. These strikes will involve Job Centre staff, tax workers, coastguards and court staff, who are looking at losing up to a third of their redundancy entitlements, costing them tens of thousands of pounds if they lose their jobs. The measures being proposed will save the government up to £500 million; but this is a essentially a warm-up by the government paving the way for future cuts.

In this situation facing tens of thousands of government employees, the PCS (the Public and Commercial Services union) are attempting to emulate the postal union, the CWU, in introducing a series of rolling strikes which not only separate these sectors of workers from others but will also sap the energy from the movement. This is really pernicious because this sector covers such a wide range of workers. All face the possibility of striking on different days and in different sectors, or, like the postal workers, the possibility of a long drawn out series of strikes which are easily prey to the manipulations of the PCS.

In British Airways, against management plans to introduce a new fleet on lower pay and worse conditions, a prelude to cutting pay and conditions including cutting existing crew members across the fleet, British Airways cabin crew voted overwhelmingly for strike action. Here, the carve-up before there were any strikes was blatant. There was a meeting of Unite branches at Kempton Park racecourse on 25 February attended by more than a thousand workers in which there was a clear majority for strike action.

This provoked a comment from Len McCluskey, Unite's assistant general secretary: "We won't be giving any deadlines to anybody. Calm needs to be injected into the situation." A further statement was made by a Unite spokesman in the Guardian (4/3/10): "Negotiations are certainly ongoing. We do not want to create any sense that we are not serious about negotiating. And announcing strike dates would do that. We will announce strike dates when all other options have been exhausted".

In an atmosphere of management harassment and paranoia BA is attempting to divide cabin crew by setting up a new union, the PCCC (Professional Cabin Crew Council) which claims that it represents ‘ordinary' cabin crew. In the meantime, cabin crew are expected to work with reduced staff and if they talk to passengers about the strike or their grievances they are severely disciplined by BA management. They are also being attacked by the media who emphasise at each and every opportunity the ‘inconvenience' that a strike will force upon the innocent public. It is the sort of intimidation that smacks of the bombastic bullying and harassment meted out to postal workers during last year's strikes.

The prevarication from Unite is aimed at keeping control of the situation and reaching a settlement with BA, or in a, for the union, worse case scenario reduce the strike action. At the time of writing, it is looking increasingly likely that the union will come up with a deal which is worse than useless to the workers:

"Hopes of a deal in the British Airways cabin crew dispute were rising last night as the unions offered to take a pay cut. The Unite union and its cabin crew branch put forward a cost-saving plan that would involve taking a 3.5 per cent pay cut and freezing salaries for two years." (Daily Mail, 6/3/10) To this the Guardian (5/3/10) added the possibility of "An agreement to create a ‘new fleet' consisting of new, lower-paid recruits on separate planes." This looks like a classic example of ‘divide and rule.

It is a sign of the times when sectors such as BA's cabin crew workers or civil service workers are being brought into struggle. It is an expression of both the depth of the economic crisis and the fundamental need of the British bourgeoisie to make all sectors of workers pay for the crisis. By the same token, these disputes express the need for all workers to fight together. Workers have to draw the lessons of past struggles, in particular the postal workers who are still waiting for the results of union/management ‘negotiations'. The postal workers are in this position because they allowed the CWU to isolate them. Allowing the union to reduce the struggle to specialised negotiations with the bosses can only sap workers' will to fight and their ability to control and spread the struggle.

Melmoth 6/3/10

see also

Geographical:

- Britain [13]

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [14]

- Trade Unions [41]

Avatar – the only dream capitalism can sell is a world without capitalism

- 2130 reads

This article, from the printed edition of World Revolution, has already been published online here [42]

Recent and ongoing:

- Film Review [43]

- ideology [44]

Corruption – an integral part of parliamentary politics

- 2291 reads

People go into bourgeois politics for diverse reasons, but few are able to resist the opportunity to use their membership of parliament or government as a way of lining their own pockets. Their loyalty to the state as it deceives and exploits the population is amply rewarded by large salaries, bribes, luxurious privileges, and ‘plenty of time on their hands'.

The ongoing MP expenses scandal at Westminster revealed this basic truth of the workings of the democratic machinery of the state. It's certainly interesting to know the ugly details of the swinish greed of those whose job it is extol the principles of equality and social responsibility.

It's also instructive to see the increasing scale of the politicians' avarice: it seems that the more capitalism sinks into its irresolvable crisis, the more those responsible for the system try to save their own skins at the expense of the population with ever greater theft from the public purse. The colossal bonuses paid to top bank employees, often the same people who were responsible for losses of billions of pounds during the credit crunch, echoes in the private sector MPs' sordid milking of the public cow.

But a question needs answering. Why does the bourgeois press and other media parade all this venality in front of our noses on the front pages and the first item on news bulletins? Why not continue to keep it quiet in order not to enrage the mass of the population which is meanwhile sinking deeper into poverty?

The bourgeoisie learnt long ago - possibly with the enquiries into child labour in the factories in the 19th century - that it couldn't completely hide the vast corruption and inhumanity of the system from the eyes of the working class. It had to find a way of presenting it to them which would preserve the existing social system from any serious threat from the exploited and divert the latter into false solutions. Thus, the most intelligent and powerful ruling classes in the world have sometimes give us a glimpse of the truth while, at the same time, portraying their intrinsic, exploiting nature as something temporary, exceptional, or if widespread, something that can be reformed if enough energy and pressure is applied through the existing democratic machinery. Here the leftists today show their worth to capitalism by pretending we can ‘smash' all the various abuses of the system.

Thus the MPs' expenses scandal was uncovered by a persistent and courageous lone journalist (already dramatised in a TV film); MPs have been sacked, and have had to repay the expenses they falsely claimed, while senior politicians have united to pledge to clean up public life, blah, blah, blah.

However this familiar process of redemption after a public scandal has not been very convincing; the electoral process has not yet been reinvigorated. Today the bourgeoisie has less room to manoeuvre and the scandals are more and more enormous.

The corruption of MPs is not an abuse of the system, it is the democratic system.

Como 6/3/10

see also

Geographical:

- Britain [13]

Recent and ongoing:

SWP dragging workers to the polling booths

- 2045 reads

When a general election comes around leftist groups are put in an embarrassing position. Typically they call themselves ‘socialist' or ‘revolutionary' and, as part of their basic function, criticise the Labour Party, whether in government of opposition. The problem they have at election time is how to retain their ‘radical' credentials while taking part in the whole parliamentary circus.

In the pages of Socialist Worker (13/2/10) you can read their answer to the very concrete question "Who do you vote for?" Because "After 13 years of bloody war, privatisation and assaults on workers' living standards, some workers say they will never vote Labour again" the SWP is participating in a Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) which is standing 50 candidates. Elsewhere they will call for a vote for other groups like Respect.

This is a simple scheme enabling workers to let off steam and protest about Labour with a trip to the polling station to vote for groups and parties that put forward the same state capitalist policies as Labour. It won't mean voting Labour, just for Labour policies.

However the SWP note "Unfortunately in most areas, workers won't have a TUSC or other left candidate to vote for. The choice will be much more stark - vote Labour or don't vote at all." They don't explain why the workers who say they're never going to vote Labour again because of the experience of the last 13 years have got it wrong. Where millions are in a position to see that all the parties are offering the same austerity policies, the SWP claim that "there is an important difference between Labour and the Tories. Basically it comes down to class. Labour still retains a link with the organised working class through its union affiliations."

There is no class difference between Labour and Tory parties. The unions do indeed have links with Labour, but their function is to control the working class and undermine its struggles. Among the minority of workers who are in unions there is a growing suspicion of their pretence to represent workers.

The SWP say they will not "cover up" Labour's "horrendous record," but then give reasons to vote for them. For the SWP "A class line will open up as the election gets closer. Most workers will grudgingly line up with Labour against the Tories." Actually, a real class line separates those who tout for the Labour Party and the electoral process from those who insist that the working class can only defend itself through its collective struggle.