International Review 2010s : 140 - 163

- 5933 reads

Index of International Reviews for the decade 2010

Site structure:

2010 - 140 to 143

- 4640 reads

International Review no.140 - 1st quarter 2010

- 3456 reads

Copenhagen Summit: Save the planet? No, they can't!

- 3564 reads

"Copenhagen ends in failure" (Guardian, UK) "Fiasco in Copenhagen", "Grotesque conclusion", "Worse than useless" (Financial Times, UK), "A worthless summit" (The Asian Age, India), "A cold shower", "The worst agreement in history" (Liberation, France)... The international press is nearly unanimous[1] that this supposedly historic summit was a catastrophe. In the end the participatory countries signed an accord in the form of a vague promise for the future, which guaranteed nothing and committed no one: reducing warming to 2°C in 2050. "The failure of Copenhagen is even worse than one could imagine" according to Herton Escobar, the science specialist of the daily O Estado De Sao Paulo (Brazil), "The greatest diplomatic event in history didn't produce the least commitment".[2] All those who had believed in a miracle, the birth of "green capitalism", have seen their illusions melt away like a glacier in the Arctic or Antarctic.

An international summit to calm fears

The Copenhagen summit was preceded by an immense publicity campaign. The media barrage was orchestrated on an international scale. All the television channels, newspapers and magazines made this event an historic moment. There is no shortage of examples.

From the 5th June 2009 the documentary film by Yann Arthus Bertrand, Home, a dramatic and implacable exposition of the scale of the world ecological catastrophe, was shown simultaneously and without charge in 70 countries (on television, internet, and in the cinemas).

Hundreds of intellectuals and ecological associations have issued pompous declarations to "raise consciousness" and "bring popular pressure to bear on the politicians". In France the Nicolas Hulot foundation launched an ultimatum: "The future of the planet and with it, the fate of a billion starving people... is at stake in Copenhagen. Either solidarity or chaos: humanity has the choice". In the United States the same urgent message was delivered: "The nations of the world meet in Copenhagen from 7 to 18 December 2009 for a conference on climate that has been called the last chance. It's all or nothing, make or break, literally, sink or swim. In fact it's the most important diplomatic meeting in the history of the world."[3]

The day of the opening of the summit, 56 newspapers in 45 countries took the unprecedented initiative of speaking with a single voice from one and the same editorial: "Unless we unite to act decisively climate change will ravage our planet [...] Climate change [...] will have indelible consequences and our chances of controlling it will be played out in the next 14 days. We call on the representatives of the 192 countries meeting in Copenhagen not to hesitate, not to quarrel or blame each other [...] Climate change affects the whole world and must be resolved by the whole world."[4]

These declarations are half true. Scientific research shows that the planet is indeed in the process of being ravaged. Global warming is worsening, and with it, desertification, fires, cyclones... Species are disappearing rapidly with pollution and the intensive exploitation of resources. 15 to 37% of biodiversity will be lost from now till 2050. Today one in 4 mammals, one in 8 birds, a third of amphibians and 70% of plants are in danger of extinction.[5] According to the World Humanity Forum climate change will lead to the death of 300,000 people a year (half from malnutrition)! In 2050 there will be "250 million climatic refugees".[6] Well, yes, it is urgent. Humanity is confronted with a vital historic challenge!

Conversely the other half of the message is a great lie designed to delude the world proletariat. It calls for the responsibility of governments and international solidarity faced with climate danger, as if states were able to forget or overcome their national interests to unite and cooperate in the interests of the well being of humanity. This is a lullaby to reassure a working class worried about the ongoing destruction of the planet and the suffering of hundreds of millions of people.[7] The environmental catastrophe clearly shows that only an international solution can work. To prevent workers thinking too much by themselves about a solution, the bourgeoisie wants to pretend that it is capable of putting aside national divisions and, according to the international editorial of 56 newspapers, of "not getting lost in quarrels", "not blaming each other" and understanding that "climate change affects the whole world and must be resolved by the whole world".

The least one can say is that this objective has completely failed. If Copenhagen has shown anything it is that capitalism can only produce hot air.

Moreover there was no illusion to create, nothing good could emerge from this summit. Capitalism has always destroyed the environment. In the 19th century, London was an immense factory spewing smoke and the Thames became a sewer. The only goal of this system is to produce profit and accumulate capital by any means. It hardly matters that in order to do so it must burn forests, pillage the oceans, pollute rivers and unbalance the climate... Capitalism and ecology are mutually antagonistic. All the international meetings, the committees, the summits (like Rio de Janeiro in 1992 or Kyoto in 1997) have always been fig leaves, theatrical ceremonies to make us think that the "great and the good" are concerned with the future of the planet. The Nicolas Hulots, Yann Arthus Bertrands, Bill McKibbens and Al Gores[8] want to make us think that it will be different this time, that faced with the urgency of the situation, the leaders will come to their senses. While all these ideologues wave their arms in the air, these same leaders brandish their eco...nomic weapons! This is the reality: capitalism is divided into nations, competing one against the other, waging an unceasing commercial and if necessary military war.

A single example. The North Pole is disappearing. The scientists see a veritable ecological catastrophe: rise in sea levels, changes in salination and alteration of currents, destabilisation of infrastructures and erosion of coasts following the melting of glaciers, the liberation of CO2 and methane from defrosted soil, degradation of arctic eco-systems.[9] Capitalist states see this as an opportunity to exploit the resources made newly available and open new sea routes free from ice. Russia, Canada, the United States, Denmark (via Greenland) are presently waging an implacable diplomatic war, including the use of military intimidation. Thus, last August, "Some 700 members of the Canadian Forces, from the army, navy and air force, participated in the pan-Canadian operation NANOOK 09. The exercise was designed to prove that Canada is capable of asserting its sovereignty in the Arctic, a region contested by the US, Denmark, and above all Russia, whose recent tactics like the sending of planes or submarines has irritated Ottawa". [10] Since 2007 Russia has regularly sent combat aircraft to overfly the Arctic and sometimes Canadian waters as it did during the Cold War.

Capitalism and ecology are indeed always antagonistic!

The bourgeoisie can no longer even save appearances

"The failure of Copenhagen" is thus anything but a surprise. We said in International Review n° 138: "World capitalism is totally incapable of the degree of international co-operation necessary to address the ecological threat. Especially in the period of social decomposition, with the disappearance of economic blocs, and a growing tendency for each nation to play its own card on the international arena, in the competition of each against all, such co-operation is impossible."[11] It is more surprising, by contrast, that all the heads of state didn't even succeed in saving appearances. Usually a final agreement is signed with great ceremony, phoney objectives are proclaimed and everybody is happy. This time, it was officially a "historic failure". The tensions and bartering have emerged from the corridors and taken centre stage. Even the traditional photo of national leaders, arm in arm with smiles of self-congratulation, was not taken. Which says it all!

This failure is so patent, ridiculous and shameful that the bourgeoisie must keep a low profile. The noisy preparations for the Copenhagen Summit have been succeeded by a deafening silence. Thus, just after the international meeting, the media contented themselves with a few discreet lines reporting the failure (while systematically blaming other nations for it) then carefully avoiding this dirty history in the following days.

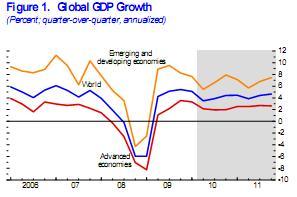

Why, unusually, did the national leaders not succeed in making it seem a success? In two words: the economic crisis.

Contrary to what has been claimed everywhere recently, the gravity of the present recession is not pushing the heads of state into "the adventure of the green economy". On the contrary the brutality of the crisis stirs up tensions and international competition. The Copenhagen Summit revealed the war that has been unleashed among the great powers. It is no longer the time to appear cooperative and to proclaim accords (even phoney ones). The knives are out. Too bad about the photo!

Since summer 2007 and the fall of the world economy into the most serious recession in the history of capitalism, there is a growing temptation to listen to the sirens of protectionism. There is a growth of every man for himself. Obviously it has always been in capitalism's nature to be divided into nations that devote themselves to implacable economic war. But the 1929 Crash and the crisis of the 30s revealed to the bourgeoisie the danger of a total absence of rules and international coordination for world commerce. In particular, after the Second World War the blocs of east and west organised themselves internally and constructed a minimum framework of economic relations. Extreme protectionism, for example, was everywhere recognised as damaging to world commerce and therefore to every nation. Accords such as Bretton Woods in 1944 and institutions policing the new rules like the International Monetary Fund have lessened the effects of economic slowdown that hit capitalism after 1967.

But the seriousness of the present crisis has weakened all these rules of functioning. The bourgeoisie has certainly tried to react in a unified fashion, organising the G20 in Pittsburgh and London, but the spirit of everyone for themselves has repeatedly reasserted itself. The plans for recovery are less and less coordinated between nation states and so the economic war is becoming more aggressive. The Copenhagen Summit strikingly confirms this tendency.

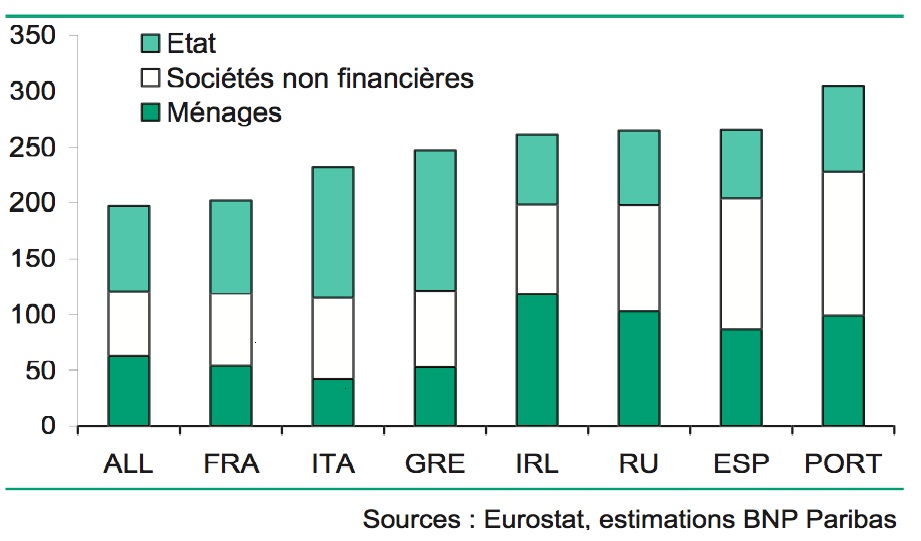

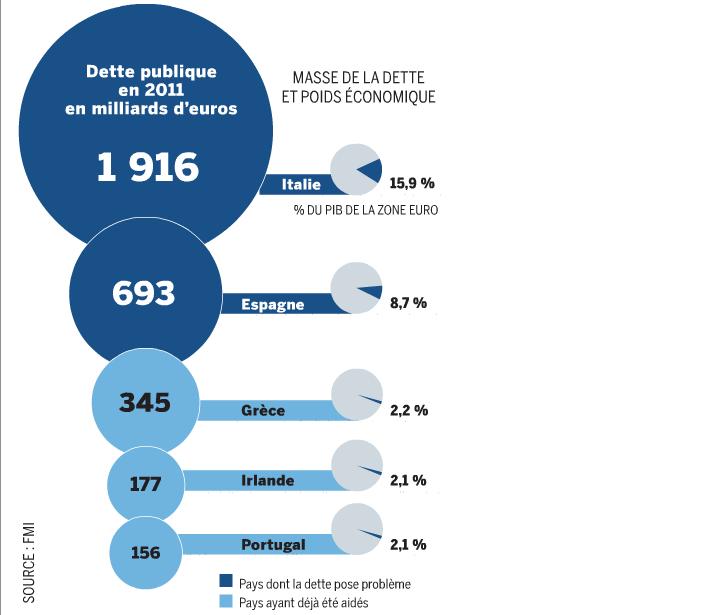

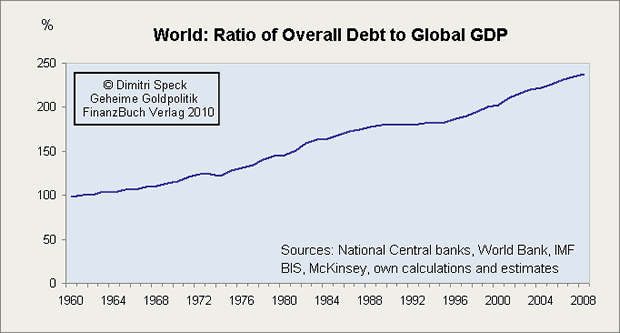

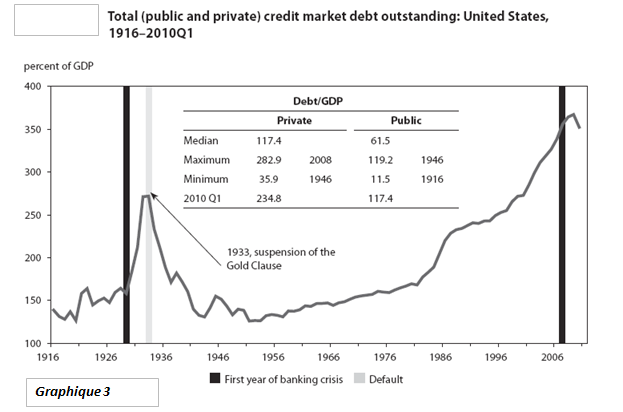

Contrary to all the lies about a light at the end of the tunnel and recovery of the world economy the recession continues to deepen and even accelerate anew at the end of 2009. "Dubai: the bankruptcy of the Emirate", "Greece is on the edge of bankruptcy"[12] - such news has been like a thunderclap. Each national state senses that its economy is in danger and is conscious that the future will bring an increasingly profound recession. To prevent the capitalist economy from sinking too rapidly into a depression, the bourgeoisie has had no other choice since summer 2007 than to create money on a massive scale in order to pay the public and budgetary deficits. Thus, as a report titled "Worst-case debt scenario" published in November 2009 by the bank Société Générale says: "The worst could be in front of us... state rescue packages over the last year have merely transferred private liabilities onto sagging sovereign shoulders, creating a fresh set of problems. First among them the deficit... High public debt looks entirely unsustainable in the long run. We have almost reached a point of no return for government debt".[13] Global indebtedness is much too high in most of the developed countries in relation to their GDP. In the United States and the European Union public debt in two years time will represent 125% of GDP. In the United Kingdom it will reach 105% and in Japan 270% (according to the report). Société Generale is not the only one to sound the alarm. In March 2009 Credit Suisse drew up a list of the 10 countries most threatened by bankruptcy by comparing deficits with GDP. For the moment this top ten comprises, in order, Iceland, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Estonia, Greece, Spain, Latvia, Rumania, Great Britain, the United States, Ireland and Hungary.[14] Another proof of the concern is on the financial markets where a new acronym has appeared: the PIGS. "Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain are going to shake the world. After Iceland and Dubai, these four overindebted countries of the euro zone are considered as possible time bombs of the world economy."[15]

In reality, all nation states, faced with their debt mountains must react with new austerity policies. Concretely that means:

develop a very strong fiscal pressure (raising taxes);

diminish expenses still more drastically by suppressing tens or hundreds of thousands of public sector jobs, reducing pensions, unemployment pay, welfare and health costs in a draconian way;

and, evidently, carry out a more and more aggressive commercial policy on the world market.

In short, this disastrous economic situation exacerbates competition. Each country today is disinclined to accept the least concession; it wages a battle royal against other bourgeoisies to survive. It was this tension, this economic war that was played out at Copenhagen.

Ecological quotas are economic weapons

At Copenhagen all the countries came, not to save the planet, but to defend themselves by hook or by crook. Their only goal was to use "ecology" to adopt rules which advantaged them while disadvantaging their rivals.

The United States and China were accused, by the majority of the other countries, of being mainly at fault for the failure. They both refused to fix any figure for the lowering of CO2 emissions, which are the main cause of climate warming. But the two greatest polluters on the planet have the most to lose.[16] "If the objectives of the IPCC[17] are retained [a lowering of CO2 by 40% by 2050] in 2050 every person in the world must emit only 1.7 tonnes of CO2 per year. Now each American produces about 20 tonnes!"[18] As for China its industry is almost entirely derived from coal that "creates 20% of the world emissions of CO2. That is more than all transport combined: cars, lorries, trains, boats and planes."[19] So one can understand why all the other countries tried so hard to "fix objective figures" for the lowering of CO2!

But the United States and China by no means made common cause. The Middle Empire had, on the contrary demanded a lowering by 40% of CO2 emissions by 2050...for the United States and Europe, while claiming that it should naturally be omitted because it was an "emerging country". "Emerging countries, notably India and China, demanded that the rich countries make a strong reduction of greenhouse gases but refused themselves to be subject to objective constraints".[20]

India used almost the same strategy: a lowering for others but not for itself. It justified its policy by the fact that "it sheltered hundreds of millions of poor and so the country could hardly be expected to make major efforts". The "emerging countries" or "developing countries", often presented in the press as the first victims of the Copenhagen fiasco, have not hesitated to use the misery of their populations to defend their bourgeois interests. The Sudanese delegate, who represented Africa, compared the situation to that of the holocaust. "It is a solution founded on the values that sent 6 million people to the gas ovens in Europe."[21] These leaders, who starve their population and who sometimes even massacre them, dare today to invoke their suffering. In Sudan for example, millions of people are being massacred today with weapons; there's no need to wait for the climate to do it in the future.

And Europe, she who plays at being the lady of good virtue, how does she defend "the future of the planet"? Let's take several examples. The French president Nicolas Sarkozy made a thunderous declaration on the last-but-one day of the summit, "If we continue like this, it's failure. [...] all of us, we must make compromises [...] Europe and the rich countries, we must recognise that our responsibility is greater than the others. Our commitment must be stronger. [...] Who will dare to say that Africa and the poorer countries do not need money? [...] Who will dare say that you don't need a body to compare respect for the commitments of each?"[22] Behind these great tirades hides a more sinister reality. The French state and Nicolas Sarkozy were fighting for a lower target for CO2 emissions and, above all, for unlimited nuclear power, that vital resource of the French economy. This energy also carries a heavy weight of menace, like a sword of Damocles hanging over humanity. The accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power station caused between 4,000 and 200,000 deaths according to estimates (depending on whether the victims of cancers caused by radiation are included). With the economic crisis, in the decades to come, states will less and less have the means to maintain nuclear power stations, and accidents will become more and more probable. And today, nuclear power pollutes massively. The French state wants us to believe that radioactive waste is treated "carefully" at La Hague when in fact to economise it exports a large part of it to Russia: "nearly 13% of the radioactive material produced by our nuclear industry sits somewhere at the end of Siberia. To be exact, in the atomic complex of Tomsk-7, a secret city of 30,000 inhabitants forbidden to journalists. There, each year since the middle of the 1990s, 108 tons of depleted uranium from French nuclear power stations has come, in containers, put aside in a huge parking lot under the open sky."[23] Another example. The countries of Northern Europe have the reputation of being at the leading edge of ecology, real little models. And yet, as far as the struggle against deforestation is concerned... "Sweden, Finland, or Austria did everything to prevent change."[24] The reason? Their energy production is extremely dependent on wood and they are huge exporters of paper. Sweden, Finland and Austria were therefore to be found at Copenhagen on the side of China which, itself, as the world's biggest producer of wooden furniture, did not want to hear any more talk of some limit to deforestation. This is not just a detail: "Deforestation is in effect responsible for a fifth of global emissions of CO2." [25] and "The destruction of the forests weighs heavily in the climatic balance [...] Around 13 million hectares of forest are cut down every year, the equivalent of the area of England, and it is this massive deforestation which makes Indonesia and Brazil the third and fourth largest emitters of CO2 on the planet."[26] These three European countries, officially living proof that a green capitalist economy is possible (sic!), "saw themselves awarded the prize of Fossil of the Day[27] during the first day of the negotiations for their refusal to accept their responsibility concerning the conversion of forested land."[28]

The country that sums up all the bourgeois cynicism which surrounds "ecology" is Russia. For months, the country of Putin has cried loud and strong that it is favourable to an agreement on targets for CO2 emissions. This position is a little surprising when one knows the state of nature in Russia. Siberia is polluted by radioactivity. Its nuclear weapons (bombs, submarines...) rust in graveyards. Will the Russian state show any remorse? "Russia presents itself as a model nation on the subject of CO2 emissions. But this is nothing but a conjuring trick. Here's why. In November, Dimitri Medvedev [the Russian president] was engaged in reducing Russian emissions by 20% by 2020 (from a base in 1990[29]), more than the European Union. But there was only one constraint since, in reality, Russian emissions had already reduced by... 33% since 1990 because of the collapse of Russian GNP after the fall of the Soviet Union. In effect, Moscow wants the power to emit more CO2 in the years to come in order to not curb its growth (if this returns). The other countries are not going to accept this position easily."[30]

Capitalism will never be "green". Tomorrow, the economic crisis will hit even harder. The fate of the planet will be the last worry of the bourgeoisie. It will look out for only one thing: to support its national economy, while confronting other countries with ever increasing force; in shutting down less profitable factories, even if it means leaving them to rot; lowering production costs; cutting maintenance budgets for factories and power stations (nuclear or coal-fired), which will also mean more pollution and industrial accidents. This is the future capitalism has in store: a profound economic crisis, a polluted and deteriorating infrastructure, and growing suffering for humanity.

It is time to destroy capitalism before it destroys the planet and decimates humanity!

Pawel (6 January 2010)

[1]. Only American and Chinese papers conjured up a "success", a "step forward". We will say why a little later.

[2]. https://www.estadao.com.br/estadaodehoje/20091220/not_imp484972,0.php

[3]. Bill McKibben, American writer and militant in the magazine Mother Jones.

[4]. https://www.courrierinternational.com/article/2009/12/07/les-quotidiens-...

[5]. https://www.planetoscope.com/biodiversite

[6]. https://www.futura-sciences.com/fr/news/t/climatologie-1/d/rechauffement...

[7]. This is not to exclude the fact that a great many intellectuals and responsible ecological organisations themselves believe in the history they have invented. This is very possibly the case.

[8]. Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize for his struggle against global warming with his documentary "An Inconvenient Truth"!

[9]. https://m.futura-sciences.com/2729/show/f9e437f24d9923a2daf961f70ed44366...

[10]. https://www.radio-canada.ca/nouvelles/National/2009/08/19/001-harper-exe...

[11] "The myth of the ‘green economy'". Third quarter 2009.

[12]. Liberation, 27 November and 9 December 2009. The list has only grown since the end of 2008 and beginning of 2009 when Iceland, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Estonia were already dubbed "bankrupt states ".

[13]. Report made public by the British Daily Telegraph, 18 November 2009. (https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/6599281/Societe-Generale-t...)

[14]. Source: https://weinstein-forcastinvest.net/apres-la-grece-le-top-10-des-faillit...

[15]. Le nouvel Observateur, French magazine, from 3rd to 9th December.

[16]. Hence the cry of victory from the American and Chinese press (highlighted in our introduction), for whom the absence of an agreement is a "step forward". .

[17]. The group of inter-governmental experts on the evolution of the climate.

[18]. Le nouvel Observateur , 3 to 9 December (special Copenhagen issue).

[19]. Idem.

[20]. https://www.rue89.com/planete89/2009/12/19/les-cinq-raisons-de-lechec-du...

[21]. Les Echos, 19 December 2009.

[22]. Le Monde, 17 December 2009.

[23]. "Nos déchets nucléaires sont cachés en Sibérie", Libération, 12 Octobre 2009.

[24]. Euronews (European television channel), 15 December 2009 (fr.euronews.net/2009/12/15/copenhague-les-emissions-liees-a-la-deforestation-font-debat)

[25]. www.rtl.be/info/monde/international/wwf-l-europe-toujours-faible-dans-la-lutte-contre-la-deforestation-143082.aspx

[26]. La Tribune (French daily), 19 December 2009 (www.latribune.fr/depeches/associated-press/le-projet-anti-deforestation-...).

[27]. This prize is awarded by a group of 500 environmental NGOs and "rewards" individuals or states which, to use a euphemism, "drag their feet" in the struggle against global warming. During the week of Copenhagen, almost every country earned the right to their Fossil of the Day (www.naturavox.fr/en-savoir/article/fossil-of-the-day-award).

[28]. Le Soir (Belgian daily), 10 December 2009 (blogs.lesoir.be/empreinte-eco/2009/12/10/redd-l%E2%80%99avenir-des-forets-tropicales-se-decide-a-copenhague).

[29]. 1990 is the reference year for greenhouse gas emissions for all countries since the Kyoto Protocol.

[30]. Le nouvel Observateur from 3rd to 9th December 2009.

General and theoretical questions:

Recent and ongoing:

Immigration and the workers’ movement

- 7782 reads

The United Nations estimates that there are as many as 200 million immigrants - approximately three percent of the world's population - living outside their home country, double the number in 1980. In the United States, there are 33 million foreign-born residents, approximately 11.7 percent of the population; in Germany 10.1 million, 12.3 percent; in France 6.4 million, 10.7 percent; in the United Kingdom 5.8 million, 9.7 percent; in Spain 4.8 million, 8.5 percent; in Italy 2.5 million, 4.3 percent; in Switzerland 1.7 million, 22.9 percent; and in the Netherlands 1.6 million.[1] Bourgeois government and media sources estimate that there are more than 12 million illegal immigrants in the US, and more than 8 million in the European Union. In this context, immigration has emerged as a hot button political issue throughout the capitalist metropoles and even within the Third World itself, as the anti-immigrant riots in South Africa last year demonstrate.

While it varies from country to country in its details, the bourgeoisie's attitude towards mass migration generally follows a three-faceted pattern: 1) encouraging immigration for economic and political reasons; 2) simultaneously restricting it and trying to control it, and 3) orchestrating ideological campaigns to stir up racism and xenophobia against immigrants in order to divide the working class against itself.

Encouraging immigration. The ruling class relies upon immigrant workers, legal and illegal, to fill low paid jobs that are not attractive to native workers, to serve as a reserve army of unemployed and underemployed workers to depress wages for the entire working class and to fill workforce shortages created by aging populations and declining native birth rates. In the US, the ruling class is abundantly aware that entire industries, such as retail, construction, meat and poultry processing, janitorial services, hotels, restaurants, and home health and child care, rely heavily on immigrant labor, both legal and illegal. This is why the demands by the far right for the deportation of 12 million illegal immigrants and the curtailment of legal immigration in no way represents a rational policy alternative for the dominant fraction of the American ruling class, and has been rejected as irrational, impractical, and harmful to the American economy.

Restricting and controlling. At the same time, the dominant fraction recognizes a need to resolve the status of undocumented immigrants to alleviate a multitude of social, economic and political problems, including the availability and delivery of medical, social, educational and other public services, as well as a variety of legal questions pertaining to the American-born children of immigrants and their property. This was the backdrop to the proposed immigration reform in spring 2007 in the US, which was supported by the Bush administration and the Republican leadership, the Democrats (including the left personified by the late senator Edward Kennedy), and major corporations. Far from being a pro-immigrant law, the legislation called for the militarization and tightening of the border, the legalization of illegal immigrants already in the country, and measures to control and restrict the future flow of immigrants. While it provided a means for illegal immigrants currently in the country to legalize their status, it was in a no way an "amnesty," as it included time delays and huge fines.

Ideological campaigns. Anti-immigrant propaganda campaigns vary from country to country, but the central message is remarkably similar, targeting primarily "Latinos" in the US and Muslims in Europe, with the allegation that recent immigrants, particularly undocumented immigrants, are responsible for worsening economic and social conditions faced by the native working class, by taking jobs, depressing wages, overcrowding schools with their children, draining social welfare programs, increasing crime, and just about any other social woe you can think of. This is a classic example of capitalism's strategy of "divide and rule", to divide workers against themselves, to blame each other for their problems, to fight over the crumbs, rather than to understand that it is the capitalist system itself that is responsible for their suffering. This serves to undermine the working class's ability to regain its consciousness of its class identity and unity, which is feared most of all by the bourgeoisie. Most typically the division of labor within the bourgeoisie assigns the rightwing to stir up and exploit anti-immigrant sentiment in all the capitalist metropoles with varying degrees of success, resonating within certain sectors of the proletariat, but nowhere else has it reached the barbaric level exemplified by the xenophobic riots against immigrants in South Africa in May 2008.

Worsening conditions in the underdeveloped countries in the years ahead, including not only the effects of decomposition and war, but also climate change, will mean that the immigration question is likely to increase in significance in the future. It is crucial that the workers' movement is clear about the meaning of the immigration phenomenon, the strategy of the bourgeoisie with regard to immigration in terms of its policies and its ideological campaigns, and the proletarian perspective on this question. In this article, we will examine the role of population migration in capitalist history, the history of the immigration question within the workers' movement, the immigration policy of the bourgeoisie, and an orientation for revolutionary intervention in regard to immigration.

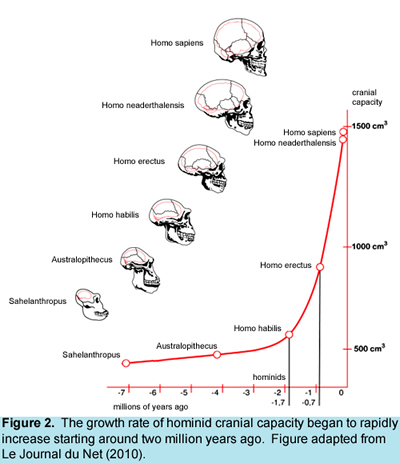

Immigration and capitalist development

Migration has been a central characteristic of human populations from the very beginnings of human history, driven largely by the need to survive in the face of difficult conditions. For example, anatomically modern humans, homo sapiens, developed in Africa about 160,000 to 200,000 years ago, and are believed to have begun a series of migrations out of Africa towards Asia and Europe 150,000 to 50,000 years ago, driven by unstable climatic and environmental conditions linked to various ice ages. The subsequent property relations of slave society and feudalism tied humans to the land, but even under these modes of production, populations migrated, conquering new areas, overcoming indigenous populations. As with other questions confronting the working class, it useful to analyze the question of immigration in the context of the ascendancy and decadence of capitalism.

In the ascendant period, capitalism placed tremendous importance on the mobility of the working class as a factor in the development of its mode of production. Under feudalism the toiling population was bound to the land, hardly moving throughout their lives. By expropriating the agricultural producers, capitalism obliged large populations to move from the countryside to the towns, to sell their labor power, providing a much needed pool of labor. As World Revolution n° 300 noted in "The working class is a class of immigrants", "In the early history of capitalism, its period of ‘primitive accumulation', the first wage laborers had their ties with feudal masters severed and ‘great masses of men are suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence, and hurled onto the labor market as free, unprotected and rightless proletarians. The expropriation of the agricultural producer, of the peasant, from the soil is the basis of the whole process' (Marx, Capital Vol.1, Ch. 26)." As Lenin put it, "Capitalism necessarily creates mobility of the population, something not required by previous systems of social economy and impossible under them on anything like a large scale".[2] As ascendancy progressed, mass migration was critically important for the development of capitalism in its period of industrialization. The movement and relocation of masses of workers to where capital needed them was essential. From 1848 to 1914, 50 million people left Europe, the overwhelming majority settling in the United States. Twenty million migrated from Europe to the US between 1900 and 1914 alone. In 1900 the US population was approximately 75 million and in 1914 it was approximately 94 million; which means that in 1914 more than one in five was a recently arrived immigrant - not counting immigrants arriving before 1900. If the children of immigrants who were born in the US are included in the count, then the impact of immigrants on social life is even more significant. During this period the US bourgeoisie essentially followed a policy completely open to immigration (with the exception of restrictions on Asian immigrants). For the immigrant workers who uprooted themselves, the motivation was the opportunity to improve their standard of living, to escape the effects of poverty and famine, oppression, and limited opportunity.

While it pursued a policy of encouraging immigration, the bourgeoisie did not hesitate at the same time to use ideological campaigns of xenophobia and racism as a means to divide the working class against itself. So called "native workers" - some of whom were themselves only second or third generation descendants of immigrants were pitted against newcomers, who were denounced because of their linguistic, cultural, and religious differences. Even between newly arrived immigrant groups ethnic antagonisms were employed as fodder for the "divide and rule" strategy. It is important to remember that the fear and mistrust of outsiders has deep-seated psychological roots in society, and that capitalism has not hesitated to exploit this phenomenon for its own nefarious purposes. The bourgeoisie, especially in the U.S, has used this tactic of "divide and rule" to undermine the historic tendency towards class unity and to better subjugate the proletariat. Engels noted in a letter to Schlüter in 1892 that the American "bourgeoisie knows much better even than the Austrian Government how to play off one nationality against the other: Jews, Italians, Bohemians, etc., against Germans and Irish, and each one against the other..."[3] It is a classic ideological weapon of the enemy class.

Whereas immigration in the period of capitalist ascendance was largely fueled by the need to satisfy the labor force requirements of a rapidly expanding, historically progressive mode of production, in decadence, with the slowing down of exponential growth rates, the motivation for immigration came from more negative factors. The pressure to escape persecution, famine and poverty, which motivated millions of workers in the ascendant period to migrate in search of work and an improved standard of living, inevitably increased in the decadent period at a higher level of urgency. The changing characteristics of modern warfare in decadence in particular gave new impetus to mass migration and the flood of refugees. In ascendance wars were limited primarily to the conflict between professional armies on the battlefields. With the onset of decadence the nature of war changed dramatically, involving the mobilization of the entire population and economic apparatus of the national capital. This consequently made terrorization and demoralization of the civilian population a primary tactical objective, and contributed to massive refugee migrations of the 20th and now the 21st centuries. During the current war in Iraq, for example, an estimated two million people have become refugees, seeking safety primarily in Jordan and Syria. Immigrants fleeing the increasingly barbaric conditions in their home countries are further victimized along the way by corrupt police and military, mafias and criminals, who extort them, brutalize them, and rob them in their desperate journey to a hoped-for better life. Many of them die or disappear along the way and some of them fall into the hands of human traffickers. Remarkably the forces of capitalist law and order appear incapable or unwilling to do anything to alleviate these social evils that accompany mass migration in the current period.

In the US, decadence was accompanied by an abrupt change from a wide open immigration policy (except for the long-standing restrictions on Asian immigrants) to highly restrictive governmental immigration policies. With the change in economic period, there was indeed less need for a continuing massive influx of labor. But this was not the only reason to further restrict immigration; racist and "anti-communist" factors were equally present. The National Origins Act enacted in 1924 limited the number of immigrants from Europe to 150,000 persons per year, and allocated the quota for each country on the basis of the ethnic makeup of the US population in 1890 - before the massive waves of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe arrived in the US. Targeting of eastern European immigrant workers in this manner was in part attributable to racism against "undesirable" elements like Italians, Greeks, Eastern Europeans, and Jews. During the period of the "Red Hysteria" in the US following the Russian Revolution, working class immigrants from Eastern Europe were regarded as likely to include a disproportionate number of "Bolsheviks" and those from Southern Europe, anarchists. In addition to restricting the flow of immigrants, the 1924 law created for the first time in the US the concept of the non-immigrant foreign worker - who could come to America to work but was barred from staying.

In 1950, the McCarran-Walter Act, heavily influenced by McCarthyism and the anti-communist hysteria of the Cold War, imposed new limits on immigration under cover of the struggle against Russian imperialism. In the late 1960's, with the onset of the open crisis of world capitalism, US immigration policy was liberalized, increasing the flow of immigrants into the US, not only from Europe, but Asia and Latin America, reflecting in part American capitalism's desire to match the European powers' success in tapping their former colonial countries for talented, skilled intellectual workers, such as scientists, medical doctors, nurses and other professions - the so-called "brain drain" from the underdeveloped countries - and to provide low-paid agricultural workers. The unintended consequence of the liberalization measures was a dramatic increase in illegal as well as legal immigration, particularly from Latin America.

In 1986, America's anti-immigrant policy was updated with enactment of the Simpson-Rodino Immigration and Naturalization Control Reform Act, which dealt with the influx of illegal immigrants from Latin America by imposing, for the first time in American history, sanctions (fines and even prison) against employers who knowingly employed undocumented workers. The influx of illegal immigrants had been heightened by the economic collapse of Third World countries during the 1970s, which triggered a wave of impoverished masses fleeing destitution in Mexico, Haiti, and war-ravaged El Salvador. The enormity of this uncontroled upsurge could be seen in the arrests of a record 1.6 million illegal immigrants in 1986 by US immigration police.

On the level of ideological campaigns, the use of the divide and rule strategy in regard to immigration, already utilized as a tactical weapon against the proletariat during the ascendance of capitalism, has been elevated to new heights in the period of capitalist decadence. Immigrants are blamed for flooding the metropoles, for cutting and depressing wages, for being the cause of epidemics of crime and cultural "pollution", overcrowding in schools, overburdening social programs - every imaginable social problem. This tactic has not been limited solely to the US, but has also been used in Britain, France, Germany and throughout Europe, where immigrants from Eastern Europe, Africa and the Middle East are scapegoated for the social ills of crisis-ridden, decomposing capitalism in remarkably similar ideological campaigns, demonstrating in this way that mass immigration is a manifestation of the global economic crisis and worsening social decomposition in less developed countries. All of this is done in order to throw up obstacles to block the development and spread of class consciousness within the working class, to try to hoodwink workers to prevent them from understanding that it is capitalism which creates war, economic crisis, and the full range of social problems characteristic of social decomposition.

The social impact of worsening decomposition and attendant crises including the growth of the ecological crisis will undoubtedly drive millions of refugees towards the developed countries in the years ahead. While these sudden, massive population shifts are handled differently by the bourgeoisie to routine immigration, they are still dealt with in a manner that reflects the basic inhumanity of capitalist society. Refugees are often herded into refugee camps, segregated from the surrounding society, and only slowly released and integrated, sometimes over many years, treated more as prisoners and undesirables than as fellow members of the human community. Such an attitude stands in stark contrast to the internationalist solidarity that would clearly be the proletarian perspective.

Historical position of the workers' movement on immigration

Confronting the existence of ethnic, racial, and linguistic differences between workers, the workers' movement has historically been guided by the principle that "workers have no country," a principle that has influenced both the internal life of the revolutionary workers' movement and the intervention of that movement in the class struggle. Any compromise on this principle represents a capitulation to bourgeois ideology.

So for example, in 1847 the German members of the Communist League in exile in London, though primarily concerned with propaganda work amongst German workers, adhered to an internationalist outlook and "maintained close relations with political fugitives from all manner of countries."[4] In Brussels, the League "held an international banquet to demonstrate the fraternal feelings harbored by the workers of each country for the workers of other countries...One hundred and twenty workers attended this banquet including Belgians, Germans, Swiss, Frenchman, Poles, Italians and one Russian."[5] Twenty years later, the same preoccupation prompted the First International to intervene in strikes with two central aims: to prevent the bourgeoisie from importing foreign strike-breakers and to provide direct support to the strikers, as they did in strikes by sieve-makers, tailors and basket makers in London and bronze workers in Paris.[6] When the economic crisis of 1866 prompted a wave of strikes throughout Europe, the General Council of the International "supported the strikers with advice and assistance, and it mobilized the international solidarity of the proletariat in their favor. In this way the International deprived the capitalist class of a very effective weapon, and employers were no longer able to check the militancy of their workers by importing cheap foreign labor. Where its influence was felt it sought to convince the workers that their own interests demanded that should support the wage struggles of their foreign comrades."[7] Similarly in 1871 when a movement for a nine hour workday arose in Britain, organized by the Nine Hour League, not the trade unions who remained aloof from the struggle, the First International supported the struggle by sending representatives to Belgium and Denmark "to prevent the agents of the employers recruiting strike-breakers there, a task which they performed with a considerable degree of success."[8]

The most significant exception to this internationalist position occurred in 1870-71 in the US, where the American section of the International opposed the immigration of Chinese workers to the US because they were used by capitalists to depress wages for white workers. A delegate from California complained that "the Chinese have driven out of employment thousands of white men, women, girls and boys." This position reflected a distorted interpretation of Marx's critique of Asiatic despotism as an anachronistic mode of production, whose dominance in Asia had to be overturned in order to integrate the Asian continent into modern productive relations, which would lead to the development of a modern proletariat in Asia. That Chinese laborers weren't yet proletarianized and were therefore susceptible to manipulation and super-exploitation by the bourgeoisie unfortunately became, not an impetus to extend solidarity and an effort to integrate them into the larger American working class, but a rationalization for racial exclusion.

In any case, the struggle for unity of the international working class continued in the Second International. A little over a hundred years ago at the Stuttgart Congress of the Second International in 1907, an attempt by the opportunists to support the restriction of Chinese and Japanese immigration by bourgeois governments was overwhelmingly defeated. Opposition was so great that the opportunists were actually forced to withdraw the resolution. Instead the Congress adopted an anti-exclusionist position for the workers' movement in all countries. In reporting on this Congress, Lenin wrote, "There was an attempt to defend narrow, craft interests, to ban the immigration of workers from backward countries (coolies-from China, etc.). This is the same spirit of aristocratism that one finds among workers in some of the ‘civilized' countries, who derive certain advantages from their privileged position, and are therefore, inclined to forget the need for international solidarity. But no one at the Congress defended this craft and petty-bourgeois narrow-mindedness. The resolution fully meets the needs of revolutionary Social Democracy."[9]

In the US, the opportunists attempted at the 1908, 1910 and 1912 Socialist Party congresses to push through resolutions to evade the decision of the Stuttgart Congress and voiced support for the American Federation of Labor's opposition to immigrants. But they were beaten back every time by comrades advocating international solidarity for all workers. One delegate admonished the opportunists that for the working class "there are no foreigners." Others insisted that the workers' movement must not join with capitalists against groups of workers. In a 1915 letter to the Socialist Propaganda League (the predecessor of the left wing of the Socialist Party that went on to found the Communist and Communist Labor parties in the US) Lenin wrote, "In our struggle for true internationalism and against ‘jingo-socialism' we always quote in our press the example of the opportunist leaders of the S.P. in America who are in favor of restrictions of Chinese and Japanese workers (especially after the Congress of Stuttgart, 1907 and against the decisions of Stuttgart). We think that one cannot be internationalist and at the same time in favor of such restrictions."[10]

Historically, immigrants have always played an important role in the workers' movement in the US. The first Marxist revolutionaries came to the US after the failure of the 1848 revolution in Germany and later constituted vital links to the European center of the First International. Engels introduced certain problematic conceptions regarding immigrants into the socialist movement in the US which, while accurate in certain aspects, were erroneous in others, some of which ultimately led to a negative impact on the organizational activities of the American revolutionary movement. Engels was concerned about the initial slowness of the working class movement to develop in the US. He understood that certain specificities in the American situation were involved, including the lack of a feudal tradition with a strong class system, and the existence of the frontier which served as a safety valve for the bourgeoisie, allowing discontented workers to escape from a proletarian existence to become a farmer or homesteader in the west. Another was the gulf between native and immigrant workers, in terms of economic opportunities and the inability of radicalized immigrant workers to communicate with native workers. For example, when he criticized the German socialist émigrés in America for not learning English, he wrote that "they will have to doff every remnant of their foreign garb. They will have to become out-and-out Americans. They cannot expect the Americans to come to them; they the minority, and the immigrants, must go to the Americans, who are the vast majority and the natives. And to do that, they must above all learn English."[11] It was true that there was a tendency for German immigrant revolutionaries to confine themselves to theoretical work in the 1880's and to disdain mass work with native, English-speaking workers, that led to Engels' comments. It was also true that the immigrant-led revolutionary movement did indeed have to open outward to English-speaking American workers, but the emphasis on Americanization of the movement implicit in these remarks proved to have disastrous consequences for the workers' movement, as it eventually pushed the most politically and theoretically developed and experienced workers into secondary roles, and put leadership in the hands of poorly formed militants, whose primary qualification was being a native, English-speaker. After the Russian Revolution, this same policy was pursued by the Communist International with even more disastrous consequences for the early Communist Party. Moscow's insistence that native American-born militants be placed in leadership positions catapulted opportunists and careerists like William Z. Foster to leadership positions, cast Eastern European revolutionaries with left communist leanings totally outside the leadership, and accelerated the triumph of Stalinism in the US party.

Similarly, another remark by Engels is also problematic: that the "great obstacle in America, it seems to me, lies in the exceptional position of the native workers... [The native working class] has developed and has also to a great extent organized itself on trade union lines. But it still takes up an aristocratic attitude and wherever possible leaves the ordinary badly paid occupations to the immigrants, of whom only a small section enter the aristocratic trades".[12] Though it accurately described how native and immigrant workers were effectively divided against each other, it implied wrongly that it was the native workers and not the bourgeoisie that were responsible for the gulf between different segments of the working class. Though this comment described the segmentation in the white immigrant working class, the new leftists in the 1960's interpreted it as a basis for the "white skin privilege theory."[13]

In any case, the history of the class struggle in the US itself disproved Engels' view that Americanization of immigrant workers was a precondition for building a strong socialist movement in the US. Class solidarity and unity across ethnic and linguistic roles was a central characteristic of the workers movement at the turn of the 20th century. The socialist parties in the US had a foreign language press that published dozens of daily and weekly newspapers in different languages. In 1912, the Socialist Party published 5 English and 8 foreign language daily newspapers, 262 English and 36 foreign weekly newspapers, and 10 English and 2 foreign news monthlies in the US, and this does not include the Socialist Labor Party publications. The Socialist Party had 31 foreign language federations within it: Armenian, Bohemian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hispanic, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, Japanese, Jewish, Latvian, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Romanian, Russian, Scandinavian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, South Slavic, Spanish, Swedish, Ukrainian and Yugoslav. These federations comprised a majority of the organization. The majority of the members of the Communist and Communist Labor Parties founded in 1919 were immigrants. Similarly the growth in Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) membership in the period before World War I came disproportionately from immigrants, and even the western IWW, which had a large "native" membership, had thousands of Slavs, Chicanos, and Scandinavians in their ranks.

The most famous IWW struggle, the Lawrence textile workers' strike of 1912, demonstrated the capacity for solidarity between immigrant and non-immigrant workers. Lawrence was a mill town in Massachusetts where workers laboured under deplorable conditions. Half the workers were teenage girls between 14 and 18 years of age. Skilled craft workers tended to be English speaking workers of English, Irish, and German ancestry. The unskilled workers included French-Canadian, Italian, Slavic, Hungarian, Portuguese, Syrian and Polish immigrants. A wage cut imposed at one of the mills prompted a strike by Polish women weavers, which quickly spread to 20,000 workers. A strike committee, organized under the leadership of the IWW, included two representatives from each ethnic group and demanded a 15 percent wage increase and no reprisals for strikers. Strike meetings were translated into twenty-five languages. When the authorities responded with violent repression, the strike committee launched a campaign by sending several hundred children of the striking workers to stay with working class sympathizers in New York City. When a second trainload of 100 children was being sent to worker sympathizers in New Jersey, the authorities attacked the children and their mothers, beating them and arresting them in front of national press coverage, which resulted in a national outpouring of solidarity. A similar tactic, sending the children of striking immigrant silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1913 to stay with "strike mothers" in other cities was also used by the IWW and again demonstrated class solidarity across ethnic barriers.

As World War I unfolded, the role of émigrés and immigrants in the leftwing of the socialist movement was particularly important. For example, on 14 January 1917, the day after he arrived in New York, Trotsky participated in a meeting at the Brooklyn home of Ludwig Lore, a German immigrant, to plan a "program of action" for the left forces in the American socialist movement. Also participating were Bukharin, who was already a US resident working as editor for Novy Mir, organ of the Russian Socialist Federation; several other Russian émigrés; S.J. Rutgers, a Dutch revolutionary who was a collaborator of Pannekoek's, and Sen Katayama, a Japanese émigré. According to eyewitness accounts, the discussion was dominated by the Russians with Bukharin arguing that the left should immediately split from the Socialist Party and Trotsky that the left should remain within the Party for the moment but should advance its critique by publishing an independent bi-monthly organ, which was the position adopted by the meeting. Had he not returned to Russia after the February Revolution, Trotsky would likely have served as leader of the leftwing of the American movement.[14] The co-existence of many languages was not an obstacle to the movement; on the contrary it was a reflection of its strength. At one mass rally in 1917, Trotsky addressed the crowd in Russian and others in German, Finnish, English, Latvian, Yiddish and Lithuanian.[15]

Bourgeois theorisation of anti-immigrant ideology

Bourgeois ideologists insist that today the characteristics of mass migration towards Europe and the US are totally different than in previous periods of history. Behind this is the idea that today immigrants are weakening, even destroying the societies that receive them, refusing to integrate into their new societies, and rejecting their political institutions and culture. In Europe, Walter Laqueur's The Last Days of Europe: Epitaph for an Old Continent makes the case that Muslim immigration is responsible for European decline. The central thesis argued by the bourgeois political scientist Samuel P. Huntington of Harvard University in his 2004 book, Who Are We: the Challenges to America's Identity is that Latin American, especially Mexican, immigrants who have arrived in the US in the last three decades are much less likely to speak English than earlier generations of immigrants coming from Europe because they all speak a common language, are concentrated in the same areas in segregated Spanish-speaking enclaves, are less interested in linguistically and culturally assimilating themselves and are encouraged not to learn English by activists who foment identity politics. Huntington further claims that the "bifurcation" of American society along white/black racial lines that has existed for generations is now threatened to be replaced by a cultural bifurcation between Spanish-speaking immigrants and native English speakers that puts American national identity and culture in the balance.

Both Laqueur and Huntington boast distinguished careers as cold war ideologists for the bourgeoisie. Laqueur is a conservative Jewish scholar, a Holocaust survivor, intensely pro-Israel, anti-Arab, and a consulting scholar with the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Cold War "think tank" linked closely to the Pentagon since 1962. Bush's former secretary of defense, Rumsfeld, consulted with the CSIS on a regular basis. Huntington, a political science professor from Harvard, served as an adviser to Lyndon Johnson during the Vietnam War and in 1968 recommended a policy of heavy bombardment of the Vietnamese countryside to undermine peasants' support for the Viet Cong and drive them into the cities. He later worked with the Trilateral Commission in the 1970s, authoring the Governability of Democracies report in 1976 and served as policy coordinator for the National Security Council in the late 1970's. In 1993 he wrote an article in Foreign Affairs, which was later expanded in 1996 into a book titled Clash of Civilizations in which he developed the thesis that after the collapse of the USSR, culture not ideology would become the dominant basis for conflicts in the world, and he predicted that an imminent clash of civilisations between Islam and the West would be the central international conflict in the future. Though Huntington's 2004 anti-immigrant tract was widely dismissed by academic scholars specializing in population studies and immigration and assimilation issues, his views got wide play among the media, pundits and policy "experts" in Washington.

Huntington's protestations that foreign speaking immigrants would refuse to learn English, resist assimilation, and contribute to cultural pollution are standard fare in the annals of US history. In the late 1700s, Benjamin Franklin feared that Pennsylvania would be overwhelmed by the "swarm" of immigrants from Germany. "Why should Pennsylvania," Franklin asked, "founded by the English, become a colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them?" In 1896, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) President Francis Walker, an influential economist, warned that American citizenship could be degraded by "the tumultuous access of vast throngs of ignorant and brutalized peasantry from the countries of eastern and southern Europe." President Theodore Roosevelt was so vexed by the influx of non-English speaking immigrants that he proposed that "every immigrant who comes here should be required within five years to learn English or leave the country." Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. made similar complaints about the socially, culturally and intellectually "inferior" immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. All of these fears and complaints of yesteryear are remarkably similar to Huntington's characterizations of the present situation.

The historic record has never supported these xenophobic fears. While there was always a certain segment of each immigrant group that aggressively sought to learn English, assimilate quickly and achieve economic success, assimilation tended to occur gradually - typically over a period of three generations. Immigrant adults generally retained their native language and cultural traditions in the US. They lived in ethnic neighborhoods, spoke their language in the community, in the shops, in religious settings, etc. They read native language newspapers, periodicals and books. Their children, who immigrated as youngsters or were born in the US, tended to be bilingual. They learned English in school and in the 20th century were surrounded by English in mass culture, but also spoke the native language of their parents in the home, and tended to marry within the national ethnic group. By the third generation, the grandchildren of the original immigrants generally lost the ability to speak the native language and were more likely to be unilingual English speakers. Their cultural assimilation was marked by a growing trend towards inter-marriage outside the original immigrant ethnic group. Despite the large Latino immigration in recent years, the same assimilation trends seem to be continuing intact in the current period in the US, according to recent studies by the Pew Hispanic Center and Princeton University sociologists.[16]

However, even if the current wave of immigration were in fact qualitatively different from previous ones, would it matter? If workers have no country, why would we be concerned whether assimilation takes place? Engels advocated Americanization in the 1880s not as an end itself, not as some timeless principle of the workers' movement, but as a means to build a mass-based socialist movement. But as we have seen, this notion that such Americanization was a necessary precondition to build working class unity was disproven by the practice of the workers' movement itself in the early 20th century, which unequivocally demonstrated that the workers' movement can embrace the diversity and international character of the proletariat and build a united movement against the ruling class.

While the 2008 xenophobic riots in South African slums are a warning sign that the bourgeoisie's anti-immigrant ideological campaigns lead ultimately to barbarism in social life, there is considerable evidence that capitalist propaganda severely exaggerates the level of anti-immigrant sentiment in the working class in the metropoles. In the US for example despite the best efforts of bourgeois media and rightwing propaganda to stir up hatred against immigrants around linguistic and cultural issues, the dominant attitude among the general population, including workers, is that immigrants are just workers trying to earn a living to support their families, that they are taking jobs that are too dirty and too low paying for "native" workers, and that it would be foolish to deport them.[17] In the class struggle itself there are increasing signs of solidarity between immigrant and "native" workers that is reminiscent of the internationalist unity at Lawrence in 1912. Examples include various struggles in 2008, such as the massive upheaval in Greece where immigrant workers joined the struggle, or in the Lindsey oil refinery strike in Britain in winter 2009 where immigrants clearly expressed their solidarity, or in the US in the Republic Window and Door factory occupation by Hispanic immigrant workers when "native" workers flocked to the plant bringing food and other supplies to show their support.

Revolutionary intervention on the immigration question

According to media reports, 80 percent of Britons believe the United Kingdom faces a population crisis caused by immigration; more than 50% fear that British culture is being diluted; 60 percent that Great Britain is more dangerous because of immigration; and 85% want immigration cut or stopped.[18] The fact that there is a certain level of receptivity to the irrational fears of racism and xenophobia propagated by bourgeois ideology among certain elements of the working class does not surprise us since the ideology of the dominant class in class society will exert immense influence on the working class until the development of an openly revolutionary situation. However, whatever the success of the intrusion of bourgeois ideology within the working class, for the revolutionary movement the principle that the world working class is a unity, that workers have no country, is the bedrock of proletarian international solidarity and working class consciousness. Anything that stresses, aggravates, manipulates, or contributes to the "disunity" of the working class is contrary to the internationalist nature of the proletariat as a class and is a manifestation of bourgeois ideology against which revolutionaries fight. Our responsibility is to defend the historic truth that workers have no country.

In any case, as usual the accusations of bourgeois ideology against immigrants are more myth than reality. Immigrants are more likely to be the victims of criminals than to be criminals themselves. In general immigrants are honest, hardworking workers, who labor long, arduous hours to earn money to support themselves and to send home to their families. They are often cheated by unscrupulous employers who pay them less than the minimum wage and refuse to pay them overtime rates, by unscrupulous landlords who charge them exorbitant rents in slum housing, and by all manner of thieves, muggers, and robbers - all of whom count on the immigrants' fear of the authorities to keep them from complaining about their victimization. Statistics show that crime tends to increase among the second and third generations in immigrant families; not because of their immigration status but due to the fact of their continued grinding poverty, discrimination and lack of opportunity as poor people.[19]

It is essential to be clear about the difference that exists today between the position of the Communist Left and that of all those who defend an anti-racist ideology (including those who pretend to be revolutionaries). Despite the denunciation of the racist character of anti-immigrant ideology, the actions they promote are on the same terrain. Rather than stressing the basic unity of the proletariat they emphasize its division. In an updated version of the old "white skin privilege theory," they blame workers who are suspicious of immigrants, not capitalism for anti-immigrant racism, and they even go on to glorify immigrant workers, as heroes who are purer than native born workers. The "anti-racists" support immigrants versus non-immigrants rather than stress working class unity. The ideology of multiculturalism which they propagate seeks to divert workers away from class consciousness to the terrain of "identity politics" in which ethnic, linguistic, and national "identity" is determinant and not membership of the same class. This poisonous ideology says that Mexican immigrant workers have more in common with the Mexican bourgeois elements than other workers. Faced with the discontent of immigrant workers against their persecution "anti-racism" ties them to the state. The solution proposed to immigrants' problems invariably stresses the resort to bourgeois legality, whether it is recruiting workers to the capitalist trade unions, or immigration law reform, or enrollment of immigrant workers in electoral politics, or formal recognition of legal "rights." Everything but the united class struggle of the proletariat.

The Communist Left's denunciation of the xenophobia and racism directed against immigrant workers is sharply distinguished from this anti-racist ideology. Our position is in direct continuity with the position defended by the revolutionary movement from the Communist League and the Communist Manifesto, the First International, the left in the Second International, the IWW, and the early Communist Parties. Our intervention stresses the fundamental unity of the proletariat, exposes the attempt of the bourgeoisie to divide the workers against themselves, opposes bourgeois legalism, identity politics, and inter-classism. For example, the ICC demonstrated this internationalist position in the US when it exposed the capitalist manipulation aimed at the demonstrations of 2006 (in favor of the legalization of immigrants) which were largely composed of Hispanic immigrants. As we wrote in Internationalism n° 139, these demonstrations were "in large measure a bourgeois manipulation," "totally on the terrain of the bourgeoisie, which provoked the demonstrations, manipulated them, controlled them, and openly led them," and were infected with nationalism, "whether it was Latino nationalism which cropped up in the opening moments of the demonstrations, or the sickening rush to affirm Americanism that followed more recently," which was "designed to completely short circuit any possibility for immigrants and American-born workers to recognize their essential unity."

Above all else, we must stand for the defense of the international unity of the working class. As proletarian internationalists we reject as bourgeois ideology such constructs as "cultural pollution," "linguistic pollution," "national identity," "distrust of foreigners," or "defence of the community or neighbourhood." On the contrary, our intervention must defend the historical acquisitions of the working class movement: that workers have no country; that the defense of national culture or language or identity is not a task or concern of the proletariat; that we must reject the efforts of those who try to use these bourgeois conceptions to exacerbate the differences within the working class, to undermine working class unity. Whatever intrusions of alien class ideology may have occurred historically, the red thread running through the entire history of the revolutionary workers movement is internationalist class solidarity and unity. The proletariat comes from many countries and speaks many languages but it is one worldwide class with the historic responsibility to confront the system of capitalist exploitation and oppression. We embrace the linguistic, cultural and ethnic diversity of our class as a strength, not a weakness, and stress the unity of the proletariat above all else and international proletarian solidarity in the face of attempts to divide us against ourselves. We must turn the principle that the workers have no country into a living reality that holds within itself the possibility to create a genuine human community in communist society. Anything else constitutes an abandonment of revolutionary principle.

Jerry Grevin, Winter 2009.

[1]. Muenz, Rainer. "Europe: Population and Migration in 2005." Retrieved Sept. 2009 from https://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=402

[2]. Lenin, The Development of Capitalism in Russia - also quoted in the same World Revolution article.

[3]. Engels to Hermann Schlüter (1892) in Marx and Engels on the Irish Question, Progress Publishers, Moscow 1971. p. 354.

[4]. Mehring, Franz, Karl Marx, p. 164.

[5]. Ibid. p. 167.

[6]. Stekloff, G.M., History of the First International, England: 1928. Chapter 7.

[7]. Mehring, op cit., p. 419.

[8]. Ibid. p. 486

[9]. Lenin, V.I. "The International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart," Proletary n° 17, Oct. 20, 1907 (We leave aside in this text controversies concerning the question of "aristocracy of labour" that Lenin implies.)

[10]. Lenin, V.I., Letter to the Secretary of the Socialist Propaganda League, Nov. 9, 1915.

[11]. Marx and Engels, Letters to Americans, p. 162-3, 290 (cited in Draper's, Roots of American Communism.)

[12]. Engels, Letter to Schlüter, op cit.

[13]. White skin privilege theory was an ideological concoction of the 1960's new leftists, which claimed that a supposed deal between the ruling class and the white working class granted white workers a higher standard of living at the expense of black workers who were victimized by racism and discrimination.

[14]. Draper, Theodore. The Roots of American Communism. Pp. 80-83

[15]. Ibid. p.79.

[16]. See "2003/2004 Pew Hispanic Center/the Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Latinos: Education" and Rambaut, Reuben G., Massey, Douglas, S. and Bean, Frank. D. "Linguistic Life Expectancies: Immigrant Language Retention in Southern California. Population and Development, 32 (3): 47-460. Sept. 2006.

[17] "Problems and Priorities," PollingReport.com, retrieved June 11, 2008.

[18]. Sunday Express. April 6, 2008.

[19]. States News Service, Immigration Fact Check: Responding to Key Myths, June 22, 2007

<!-- bmi_SafeAddOnload(bmi_load,"bmi_orig_img",0);//-->Recent and ongoing:

Science and the Marxist movement: The legacy of Freud

- 8976 reads

On the occasion of the recent bicentenary of Charles Darwin's birth, the ICC published several articles about this great scientist and his theory of the evolution of species.[1] These articles are an aspect of something that has always been present in the workers' movement: an interest in scientific questions, which is expressed at the highest level in the revolutionary theory of the proletariat, marxism. Marxism developed a critique of the idealist and religious views of human society and history which predominated in feudal and capitalist society but which also impregnated the socialist theories which marked the first steps of the workers' movement at the beginning of the 19th century. Against the latter, marxism saw as one of its first priorities the need to base the perspective of the future society, which would deliver humanity from exploitation, oppression and all the scourges which have afflicted it for millennia, not on the realisation of the abstract principles of equality and justice but on a material necessity flowing from the actual evolution of human history, and of nature, which is driven in the last instance by material forces and not by spiritual ones. This is why the workers' movement, beginning with Marx and Engels themselves, always paid particular attention to science.

Science appeared well before the beginning of the workers' movement and the working class itself. We can even say that the latter was only able to develop on a broad scale thanks to the progress of science, which was one of the preconditions for the rise of capitalism, the mode of production based on the exploitation of the proletariat. In this sense, the bourgeoisie is the first class in history which had an ineluctable need for science to ensure its own development and to affirm its own power over society. By appealing to science it was able to break the grip of religion which was the basic ideological instrument for the defence and justification of feudal society. But even more than this, science was the underpinning of the mastery of the technology of production and transport, which was a precondition for the expansion of capitalism. When the latter had reached its high point, bringing into being the force which the Communist Manifesto called its "gravedigger", the modern proletariat, the bourgeoisie turned back towards religion and the mystical visions of society which had the great merit of justifying a social order founded on exploitation and oppression, In doing so, while it continued to promote and finance all the research needed to guarantee its profits, to increase the productivity of labour power and improve the effectiveness of its military forces, it moved away from the scientific approach when it came to understanding how human society works.

It fell to the proletariat, in its struggle against capitalism and for its overthrow, to take up the flame of scientific understanding abandoned by the bourgeoisie. This is what it did in the mid-19th century by opposing the apologetics which had taken the place of the study of the economy, ie the skeleton of society, and putting forward a critical and revolutionary approach to this subject, a necessarily scientific vision, expressed for example in Karl Marx's Capital. This is why the revolutionary organisations of the proletariat have the responsibility of encouraging an interest in scientific knowledge and research, notably in the areas which relate to human society, to the human being and the psyche, domains where the ruling class has an interest in cultivating obscurantism. This does not mean that to be part of a communist organisation it is necessary to have studied science, to be capable of defending Darwin's theory or to resolve second degree equations. The bases for joining our organisation are contained in the platform which every militant has to agree with and has a responsibility to defend. Similarly, on a whole series of questions, for example the analysis we make of this or that aspect of the international situation, the organisation has to have a position which is expressed, generally speaking, in resolutions adopted by our congresses or by plenary meetings of our central organ. In these cases, it is not obligatory for each militant to agree with such statements of position. The simple fact that these resolutions are adopted after discussion and vote means that there can perfectly well be different points of view, which, if they persist and are sufficiently developed, can be expressed publicly in our press, as we can see with the debate on the economic basis of the boom that followed the second world war.

With regard to questions that deal with cultural matters

(film criticism, for example) or scientific issues, not only do they not need

to have the agreement of every militant (as is the case with the platform) but

in general they cannot be seen as representing the position of the

organisation, as is the case for resolutions adopted by congresses. Thus, like

the articles we published on Darwin, the article that follows, written on the

occasion of the 70th anniversary of the death of Sigmund Freud, does

not express the view of the ICC as such. It should be seen as a contribution to

a discussion involving not only militants of the ICC who may or may not agree

with its content, but also those outside our organisation. It is part of a

rubric of the International Review

that the ICC aims to make as lively as possible and which has the aim of giving