Submitted by International Review on

A visit to the "Truth and Memory" exhibition of British war artists, currently showing at London’s Imperial War Museum, prompts some thought about the complex relationship between art, politics and propaganda.

For a start, there is a striking contrast between the paintings in "Truth and Memory" and the conventional World War I special exhibit on the ground floor.1 Where the art is raw, harrowing, the museum exhibit is bland and colourless. Juxtapositions of military uniforms, weapons, reproductions of propaganda posters – a film of muddy fields: nothing there to shock even the most sensitive spectator. There are tin hats and jackets for visitors to try on and take selfies, but heaven forbid that we should be reminded of what this war really was, of the horror and the stench of death in the trenches. World War I has been sanitised and packaged for tourist consumption and it seems unlikely that those who visit it will learn very much, or indeed anything at all.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the World War I exhibit, in your face on the ground floor, is packed with a queue of families waiting to get in, while the exhibition of war art, discreetly hidden away on the third floor behind frosted glass doors, is almost empty. This exhibition is organised in two parts, on opposite sides of the Museum: one part called "Truth" exhibits paintings produced during the conflict, mostly by artists employed by the British War Propaganda Bureau who in some cases were already serving soldiers; the part called "Memory" contains paintings produced after the war, both independent and official. It has to be said that this section is by far the least interesting, artistically and for what it has to say about the war itself. The pictures are for the most part still, almost peaceful, they seem distant from reality, lacking in immediacy, as if both the artist and the spectators – and certainly the state – wanted not to remember but to forget, or at least to gloss over memory with a patina that would relegate the war safely to the past. Only two pictures strike us with any force. One, "A battery shelled" by Percy Wyndham Lewis (who fought in the artillery) shows the soldiers working under fire reduced to machine-like stick figures, while those outside the danger zone are detached, indifferent.

The other, "Over the top" by John Nash (brother of the much better-known artist Paul Nash) evokes the futility of the endless assaults which ended with tens of thousands dead and a military result of zero; there is something dreadful about the soldiers’ hopeless advance towards certain death, all the more so when we know that Nash portrays here an attack by his own unit, the 1st Artists Rifles, which ended with barely a man left alive or uninjured.

One is inclined to think that after the war, for the most part, people wanted to forget or at least to return to life and leave war behind. And that the governments were only to happy to let them do so because World War I had – for many – discredited capitalist society and the governments that managed it.

Society, ideology, the search for truth

Bourgeois society has a more paradoxical relationship to truth than any previous class society. This is due to two factors: the conditions and demands of industrial production; and the specific characteristics of bourgeois class domination.

Capitalism is the first mode of production which cannot live without constantly revolutionising and overturning the productive process through the application of scientific and technical innovation. At the outset, as bourgeois society begins to emerge within its feudal shell, this is not immediately apparent: the woollen textile industry in 13th century England begins to break out of the constricting bonds of the feudal guild system, but the technology remains largely unchanged. The revolution is social, not yet technical, based on new ways of organising production and trade. By the 17th century, experimental science aims to contribute to the improvement of manufacture, and by the 18th century scientific investigation of nature is applied to industry and becomes a productive force in its own right. Today, quantum mechanics and relativity theory may seem abstruse and even weird – nonetheless, a multitude of products in everyday use are dependent on their effects.

Capitalism, then, depends on science. But science itself rests on two pillars: the assumption that a world exists independent of thought, be it human or divine; and the conviction that it is possible to understand this material world through free investigation and freedom of debate.2 A precondition for the development of capitalism and bourgeois society is therefore the victory of Copernicus and Galileo over the Catholic church and the Inquisition: the Catholic church cannot be allowed to maintain its monopoly over thought.

Class rule under capitalism is also unique. Indeed, the bourgeois class is the first in history to pretend that its class domination does not exist, the first to justify its own rule by basing it on "the will of the people". Bourgeois society is therefore the most hypocritical in history.

Yet, if this were all there were to it, such domination would not long survive. The bourgeoisie dominates, but it must not be seen to dominate; its hypocrisy must be sincere. Nor can the search for truth be limited to the domain of science, prevented from spilling out into the social and artistic sphere, for science and art are not two separate worlds, they do not at all rely on antithetical or even different qualities of the human mind. The bourgeoisie then, is forced to give free rein to the search for truth as much in the artistic as in the scientific domain, under pain of loosing out to its competitors. It was the United States, not Nazi Germany, that succeeded in producing the atomic bomb.

There is another new characteristic of capitalist society: for the first time, the revolutionary class is an exploited class. Even more important, this exploited class is a cultured class. For the first time, the exploited class must be educated in order to master the intricacies of capitalist production: workers must be able to read and write, to handle increasingly complex technical and social tasks. Capitalism itself educates and trains the masses of workers in the skills necessary not just to master social organisation but to lay claim to the heritage of all humanity’s artistic, scientific, and technical knowledge and achievements which it will use to satisfy human needs, including human cultural needs. More: at its best, the proletarian class has never been satisfied with the scraps from the table of bourgeois culture, it has set out to grasp this culture and make it its own. "Marxism has won its historic significance as the ideology of the revolutionary proletariat because, far from rejecting the most valuable achievements of the bourgeois epoch, it has, on the contrary, assimilated and refashioned everything of value in the more than two thousand years of the development of human thought and culture".3

The greater the presence within society of this cultured, revolutionary and exploited class, the less the bourgeoisie can rely solely on lies and repression. Only in regimes where the workers have been utterly crushed – regimes like Nazi Germany or the Stalinist USSR – is it possible for propaganda to rely solely on the ideological knout.

The British ruling class, perhaps more than any other, is aware of this strange, shifting, and contradictory situation, aware that it must play the propaganda game in two directions. We are almost tempted to answer Winston Churchill’s famous dictum that "In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies" by turning it round: "Lies are so precious that they must be surrounded by a bodyguard of truth".

Art and propaganda

"There's an east wind coming, Watson."

"I think not, Holmes. It is very warm."

"Good old Watson! You are the one fixed point in a changing age. There's an east wind coming all the same, such a wind as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast. But it's God's own wind none the less, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared".4

These words are spoken at the very end of Arthur Conan Doyle’s last "Sherlock Holmes" story, His Last Bow, in which Holmes foils a German master spy just before the outbreak of war. The fictitious Holmes only echoes here sentiments that were expressed by real characters at the outbreak of war: Collins-Baker, Keeper at the National Gallery, writing in August 1914, believed that art would benefit from a "cleansing war",5 and this was a not uncommon view in the British establishment who hoped the war would "regenerate" art and society and rid both of the disturbances of Cubism, Modernism, and everything offensive to so-called "good taste".

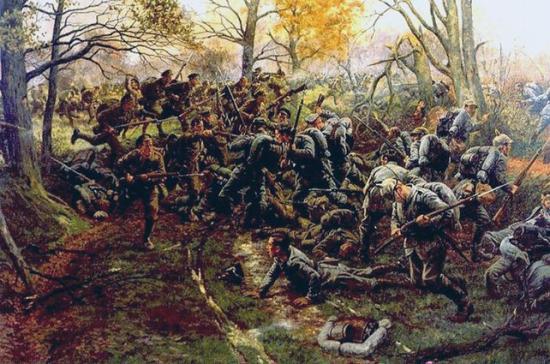

Previous wars had been celebrated "realistically" and patriotically as a series of heroic engagements – the kind of thing that could have been produced during the Crimean war for example:

Doubtless the reactionary wing of the British ruling class and its art establishment expected such painting to drown out foreign, decadent, and corrupting influences. But this turned out to be a dying genre. As we enter the exhibition we are presented, symbolically, with one example: William Barnes Wollen’s "2nd Ox & Bucks defeating the Prussian Guard at Nonne Bosschen".

Step into the next room, and we are in a different world altogether, and here we want to focus on the evolution of two artists who followed diametrically opposed directions from the artistic standpoint as a result of their war experience: CRW Nevinson and William Orpen.

Nevinson was 25 when war broke out, and joined the Friends Ambulance Unit set up by the Quakers; he was profoundly shocked by his experience and this clearly informed his art. He was already in 1914 an established landscape painter associated with the Italian Futurist movement and particularly the painter Marinetti who would later be one of Mussolini’s supporters. In 1914, Marinetti had declared that "We wish to glorify war – the only hygiene of the world" (a sentiment he shared with a Catholic reactionary such as the poet Hilaire Belloc for example, and others that we have cited above), yet there is no trace of any glorification of war in Nevinson’s work. On the contrary, Nevinson declared in 1915 that "Unlike my Italian Futurist friends, I do not glory in war for its own sake, nor can I accept the doctrine that war is the only healthgiver (…) In my pictures (…) I have tried to express the emotion produced by the apparent ugliness and dullness of modern warfare".6 In 1915, he told the Daily Express: "Our Futurist technique is the only possible medium to express the crudeness, violence, and brutality of the emotions seen and felt on the present battlefields of Europe". Nevinson uses these Futurist techniques of juxtaposed planes and sombre colouring to show man reified and dehumanised, transformed into an adjunct of the machine in a war which was mechanised more than ever before: his painting "La mitrailleuse" ("The machine gun", 1915) is emblematic of this attitude. In "Return to the trenches", the soldiers have almost been transformed themselves into machines.

Nevinson was 25 when war broke out, and joined the Friends Ambulance Unit set up by the Quakers; he was profoundly shocked by his experience and this clearly informed his art. He was already in 1914 an established landscape painter associated with the Italian Futurist movement and particularly the painter Marinetti who would later be one of Mussolini’s supporters. In 1914, Marinetti had declared that "We wish to glorify war – the only hygiene of the world" (a sentiment he shared with a Catholic reactionary such as the poet Hilaire Belloc for example, and others that we have cited above), yet there is no trace of any glorification of war in Nevinson’s work. On the contrary, Nevinson declared in 1915 that "Unlike my Italian Futurist friends, I do not glory in war for its own sake, nor can I accept the doctrine that war is the only healthgiver (…) In my pictures (…) I have tried to express the emotion produced by the apparent ugliness and dullness of modern warfare".6 In 1915, he told the Daily Express: "Our Futurist technique is the only possible medium to express the crudeness, violence, and brutality of the emotions seen and felt on the present battlefields of Europe". Nevinson uses these Futurist techniques of juxtaposed planes and sombre colouring to show man reified and dehumanised, transformed into an adjunct of the machine in a war which was mechanised more than ever before: his painting "La mitrailleuse" ("The machine gun", 1915) is emblematic of this attitude. In "Return to the trenches", the soldiers have almost been transformed themselves into machines.

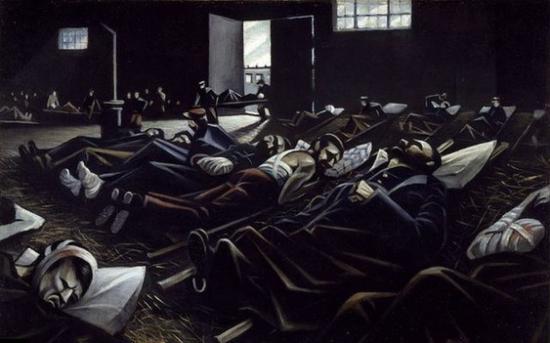

Nevinson fully intended his art to be an indictment of war and its motivations. Of his painting "La Patrie" ("The fatherland", 1916) he wrote "I regard this picture, quite apart from how it is painted, as expressing an absolutely NEW outlook on the so-called ‘sacrifice’ of war. It is the last word on the ‘horror of war’ for the generations to come"7

Nevinson’s paintings were well received when he exhibited them in November 1916, despite the fact that his modern and "foreign" style typified everything that the more patriotic and reactionary side of British society abhorred. But after two years of war, war weariness and disenchantment were setting in, and Nevinson’s ferocious critique caught the mood better than official government propaganda. Leading critics accepted that "modern methods were needed to depict modern war" and even the Times saw in his work "a nightmare of insistent unreality, untrue but actual, something that certainly happens but to which our reason will not consent".8

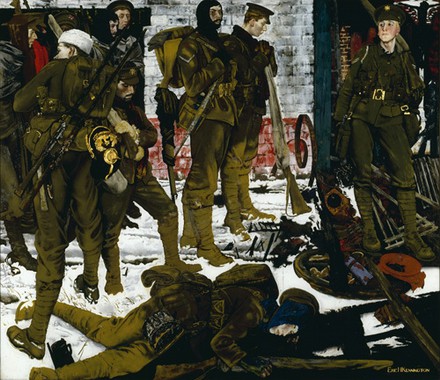

Another painting which created a sensation when it was exhibited in 1916 was Eric Kennington’s "The Kensingtons at Laventie". This painting shows his own unit shortly before he himself was wounded (Kennington appears in the background on the left wearing a balaclava helmet).

Another painting which created a sensation when it was exhibited in 1916 was Eric Kennington’s "The Kensingtons at Laventie". This painting shows his own unit shortly before he himself was wounded (Kennington appears in the background on the left wearing a balaclava helmet).

The enthusiastic reception given to Kennington’s and Nevinson’s work was in large part due to the public’s perception of these paintings as more truthful, more credible, than the drawings produced on the basis of photographs or second hand accounts, in the illustrated magazines: first, because they portrayed a reality that people knew to be far closer to the truth, both visually and emotionally, and second because the artists were, or had been, serving soldiers with real experience of the front line.

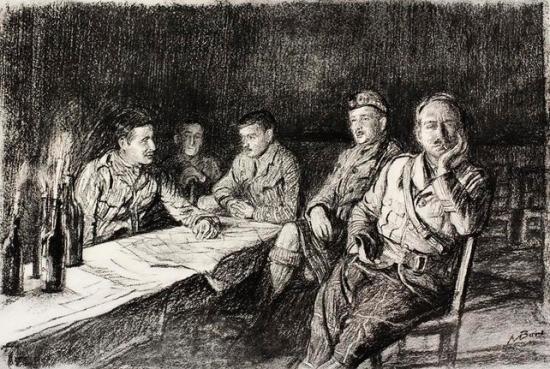

These paintings were all produced before either Nevinson or Kennington had been employed as a war artist by the British Department of Information. The latter was the successor to the Bureau of War Propaganda, which had been set up in secret in August 1914 and at first concentrated on the written word, organising the output in favour of Britain’s war effort of well-known writers like John Buchan and HG Wells. One of the Bureau’s first efforts was the "Report on alleged German outrages" (also known as the Bryce Report), which accused the German army of war crimes against civilians following the invasion of Belgium. By May 1916, the Bureau’s chairman, the Liberal MP Charles Masterman, an ally of the Prime Minister Lloyd George, decided to respond to the demand for illustrations from the picture press by recruiting the well-known artist Muirhead Bone (who had lobbied hard for the establishment of an Official War Artists scheme), who was sent to tour the front with an honorary commission.  The sketches he brought back, despite their graphic excellence, are bland and lifeless compared with the raw emotion evident in Nevinson’s art.

The sketches he brought back, despite their graphic excellence, are bland and lifeless compared with the raw emotion evident in Nevinson’s art.

Even his "Soldiers’ cemetery" is scarcely more stirring than an image of a country churchyard:

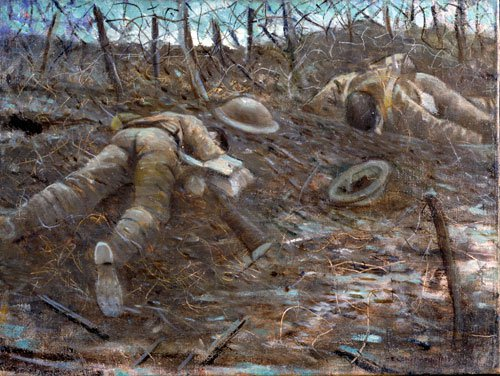

This was doubtless what prompted the Ministry of Information to open up to younger artists, especially those serving on the front whose work the public would accept as more authentic. At the same time, bringing artists under the aegis of the Ministry meant that their exhibitions were subject to military censorship. By the time that his second, hugely successful exhibition opened in 1918 Nevinson seems to have come to the conclusion that only a return to realism was adequate to express his horror at the war, as we can see in the picture ironically entitled "Paths of Glory" – a title later used by Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 anti-war film starring Kirk Douglas. The irony of the title is only too evident when we see the corpses face down in the mud, already bloated by decomposition.

If Nevinson’s earlier work showed man dehumanised, reduced to the status of a machine, incorporated into the machine one might almost say, we can wonder whether he felt the need to escape from the aesthetic, even an aesthetic of the machine, to show the true horror of what war was doing not to machines but to real human beings of flesh and blood with whom we can identify and sympathise – something we cannot do with a machine.

The painting was banned by the authorities. Nevinson hung it in the exhibition anyway, obscured by a large ribbon inscribed with the word "Censored".

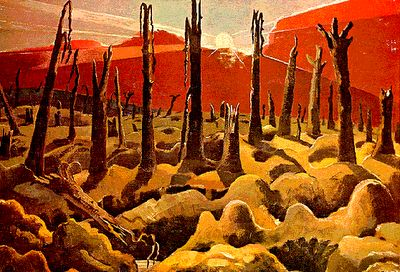

Paul Nash, another war artist who was to become one of Britain’s best known landscape artists of the 20th Century, commented bitterly on his employment as a war artist: "I am no longer an artist. I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth and may it burn their lousy souls". And the public could surely not escape the implications of this painting entitled "We are building a new world".

Paul Nash, another war artist who was to become one of Britain’s best known landscape artists of the 20th Century, commented bitterly on his employment as a war artist: "I am no longer an artist. I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth and may it burn their lousy souls". And the public could surely not escape the implications of this painting entitled "We are building a new world".

Truth will out

While Nevinson moved from the modernist to the traditional, another very different artist moved almost in the opposite direction. William Orpen was nearly 40 when war broke out, and a popular well-established, and even wealthy high society portrait painter. Sent to France as a war artist with the rank of Major, he was derided by some for his privileged and safe situation well away from any combat experience, and indeed the earliest portraits he produced could readily serve as propaganda images of British troops, especially the pilots treated by the press and the propaganda machines as the new "knights in shining armour" of modern warfare.

His portrait of the young pilot Lieutenant Rhys Davids, killed shortly afterwards in a dogfight, was much reproduced.

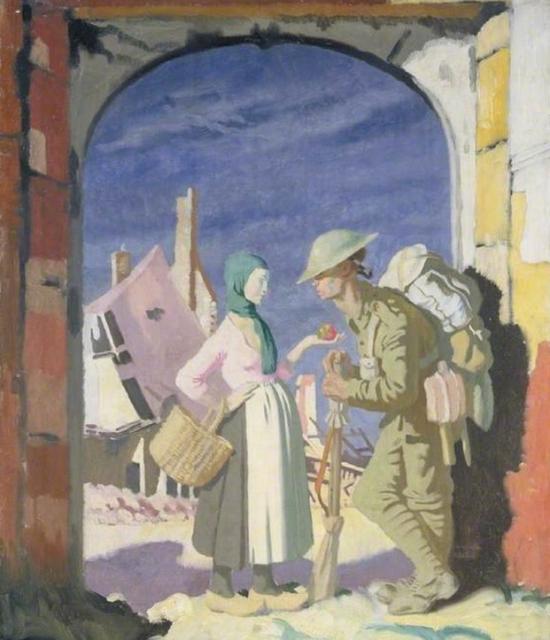

Orpen’s portraits of Generals Haig and Trenchard were also widely praised and he could have stuck to merely doing more of the same, but he did not.9 On the contrary, he was increasingly disturbed by the effects of war on those involved in it, both soldiers and civilians, and as time went on he turned more and more to an imagery that sometimes approaches a Dali-esque surrealism.

We know that he had been shocked to see young French prostitutes plying for trade at a burial ceremony. Maybe it was this that prompted his "Adam and Eve at Péronne":

There is something almost pornographic about this picture. Here there is no loss of innocence – it is already long gone, lost in the wreckage of war that we see in the background. Eve’s modest headscarf contrasts oddly with her plunging neckline and the somehow cynical expression on her face, while the bored indifference of the young soldier suggests someone who has seen so much death that he has become indifferent to life.

The same soldier turns up in "The mad woman of Douai", depicting a scene Orpen had witnessed of a woman raped shortly beforehand by retreating German troops . Here he appears equally indifferent to the rape, to the tragedy of the victim, and to the hastily buried corpse whose foot we see sticking out of its grave in the foreground.

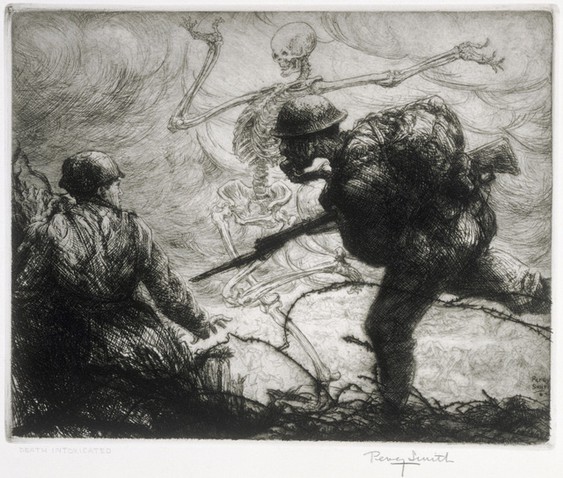

Tucked away in a room at the back of the exhibition is a series of seven etchings by Percy Delf Smith, who was a gunner in the Royal Marines on the front.

Where some of Orpen’s pictures reprise themes from Goya (for example, "Bombing, Night"), Smith returns to the imagery of decadent medieval society with its omnipresent portrayals of death. These are some of the most shocking pictures in the exhibition.

In "Death awed", even Death shies away from the slaughter, epitomised by the two boots still filled with the stumps of legs, while "Death intoxicated" makes a mockery of dance as Death cavorts deliriously behind a soldier about to spit an enemy on his bayonet.

It seems natural enough to want, almost to expect, that artists who move us by their critical spirit should share our ideas. Natural, but profoundly mistaken. The artists who figure here – and to them we could add poets like Wifred Owen and Siegried Sassoon, and German Expressionists like Otto Dix or Käthe Kollwitz – were profoundly revolted by the war, indeed several of them suffered nervous breakdowns of varying degrees of severity by the end of the war. But none of them were in the least moved by a proletarian political viewpoint; in some cases they were not even particularly attractive as people.

We sometimes forget that the great masters who we admire today were not alone, on the contrary (with very rare exceptions) they were the greatest exponents of an effort in which many were engaged. And when artists rise above the common run that surrounds them, when their art reaches heights that continue to touch us today when so many lesser contemporaries have been forgotten, then it somehow communicates to us something that goes beyond the artist himself. At such moments, the artist is attuned to something in the social atmosphere, something which is very often not explicit. Is it really an accident, that some of these most stinging indictments of the War should have been produced in the same year – and could almost have served as illustrations for – Rosa Luxemburg’s Junius Pamphlet. In Junius, Luxemburg declared: "Violated, dishonored, wading in blood, dripping filth – there stands bourgeois society. This is it [in reality]. Not all spic and span and moral, with pretense to culture, philosophy, ethics, order, peace, and the rule of law – but the ravening beast, the witches’ sabbath of anarchy, a plague to culture and humanity. Thus it reveals itself in its true, its naked form". Is it not precisely this that we see reaching out to grip us from the picture frames of the Imperial War Museum? And is it not precisely because there existed, somewhere, a mind capable of Junius, and a workers’ movement bloodied and betrayed but still alive and capable of taking up and transforming into social action the ideas of Junius, that there could also exist a critical artistic spirit capable of speaking not to the consciousness, as Luxemburg did, but directly to the emotions. In doing so, they speak to something constant in human nature, something truly human (as Marx might have said) which can only react with revulsion to the monstrous machine of death that capitalism had become.

Where is the art of World War II?

It is striking, at all events, that while World War I produced some of Britain’s greatest 20th century painting, not to mention some of Germany’s most outstanding artistic expression, nothing of the kind can be said of World War II which produced absolutely nothing comparable.

In part, this was the result of technical evolution. When illustrated magazines like the famous Picture Post looked to show the war in images, they turned less to artists than to photographers, and in particular to the new breed of war photographers such as the great Robert Capa. Much more importantly, the ruling class on both sides of the conflict had a much firmer grasp on the importance of propaganda. The Nazi regime exerted a state control over artistic production, denouncing the Expressionists as "degenerate art":  Otto Dix, though he remained in Germany, retreated into a self-imposed exile both personal and artistic, and the great enemy of capitalist war and social corruption spent his last years painting innocuous, though technically irreproachable, portraits such as "Nelly as Flora" from 1940.

Otto Dix, though he remained in Germany, retreated into a self-imposed exile both personal and artistic, and the great enemy of capitalist war and social corruption spent his last years painting innocuous, though technically irreproachable, portraits such as "Nelly as Flora" from 1940.

Hitler was a great admirer of British war propaganda, and the British themselves lost no time, when war began, in setting up a "War Artists Advisory Committee" subordinated to the Ministry of Information. We need only compare Paul Nash’s almost lyrical "Battle of Britain" with his "We are making a new world" to see that the critical spirit of the latter has completely disappeared.

Or again, compare Alfred Thomson’s 1943 painting of an injured airman receiving treatment, with Nevinson’s World War I depiction of a hospital scene in "La Patrie". Here we have an image of calm peacefulness, far removed from the agony and the anguish of the field hospital.

Or again, compare Alfred Thomson’s 1943 painting of an injured airman receiving treatment, with Nevinson’s World War I depiction of a hospital scene in "La Patrie". Here we have an image of calm peacefulness, far removed from the agony and the anguish of the field hospital.

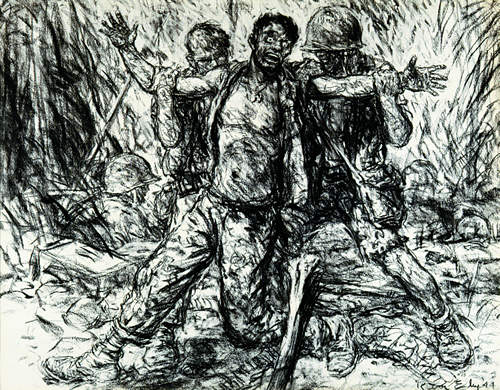

The critical spirit had not entirely disappeared. Some of the American combat artists featured on the PBS site "They drew fire" – and doubtless it is significant that these men were themselves faced with the terror of war – produced art which echoes the horror experienced by the combatants of World War I.

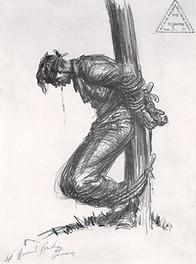

Of one sketch, the artist Howard Brodie wrote: "My most searing memory of any war was during the Battle of the Bulge, when Germans posing as GI's infiltrated our lines. I heard we were going to execute three of them… A defenceless human is entirely different than a man in action. To see these three young men calculatingly reduced to quivering corpses before my eyes really burned into my being. That's the only drawing I've ever had that's been censored. All coverage of the execution was censored".

And there is certainly nothing glorious about Kerr Eby’s "Helping wounded man" (Eby had served on an ambulance crew during World War I).

The United States’ involvement in World War I had been relatively minor, certainly the involvement of the population as a whole in the fighting was incomparably less than was the case in the European countries, and far less than it was to be in World War II. Perhaps we can explain the powerful effect of the images above by the naïvety of the American working class which – although it had to confront one of the most brutal fractions of the capitalist class in its struggles, had yet to experience the insane barbarism of full-scale modern warfare.

These forthright portrayals of war’s brutality – and the insanity it inflicts on human beings that we see staring out of the eyes of Eby’s "wounded man" – reveal an honest search for artistic truth, which shows that integrity and humanity continued to survive even in the heart of barbarism. But there is one aspect missing when we compare these to the World War I works: a sense of a broader social criticism that goes beyond the individual reaction to individually experienced events. Marx was wrong to say that only bad artists put titles on their paintings (Britain’s greatest landscape artist, William Turner, not only gave his works long titles, he sometimes accompanied them with lines from his own poetry), and titles such as "Paths of Glory" or "We are making a new world" underscore for us the broader protest of the artist against the war, its causes and its consequences.

Thanks to "socialist realism", Russian painting of World War II was anything but realistic, and during the Korean War the principles of socialist realism seem to have been applied with equal enthusiasm by both the Americans and the Chinese.

Vietnam: art against war

It is only with the Vietnam War that art truly returns to a critical onslaught against war, and here it is art of a new kind that comes front-stage: photography.

Photography and painting are very different technical skills: where the painter sketches to prepare a final work, the photographer will take hundreds, sometimes even thousands of shots. Where the painter adds to his work, little by little, teasing out the truth by adding paint, the photographer rejects, pares down to a single shot which best embodies the event, the scene, or the face that he is trying to represent. And of course, black and white photography in particular involves a subtle work with chemicals in the darkroom to deepen shadow, highlight, and bring the focus onto the essentials.

At their highest expression, painting and photography can, like all art, both express a search for truth. And hence we have one of the most emblematic pictures from the Vietnam war. Vietnamese photographer Nick Ut's photo of Trang Bang after Napalm Attack (8th June, 1972). No painting from World War I portrayed the sheer horror, barbarity, and above all senselessness of this war better than does this photo.

Nick Ut was a photographer with Associated Press, a non-profit news cooperative founded during the Mexican War of 1846, which produced much of the best – most emotionally true – photography to come out of the Vietnam War.10 The war itself came at a very specific moment, and was in some ways unique in the annals of war photography. For one thing it was “the first war in which reporters were routinely accredited to accompany military forces, yet not subject to censorship.”11 This was a lesson that the United States, in particular, was to learn for future wars. The Gulf Wars, for example, were rigorously censored with television reporting being systematically verified before going on air. All those "live" reports were live only in the sense that they came with a few minutes delay while the military censor checked their content as it streamed: under such conditions, many reporters learned to censor themselves.

Pictures like Ut’s, or like Art Greenspon’s photo of American soldiers awaiting a helicopter coming to evacuate the wounded, are more than just war photography telling a striking story, they are also a form of social criticism. Although there are relatively few pictures of Vietcong troops other than prisoners, we are left in no doubt who are the principal sufferers in the war: the civilians first and foremost, of course, but also the "grunts" as the American GI conscripts were called to distinguish them from the "lifers", or professional military (and of course the South Vietnamese army and the Vietcong had their equivalents): overwhelmingly, it was the conscripts, workers in uniform, who were sent into the most dangerous situations on the front lines.

If this form of social criticism were possible, this is not just because the American army had not yet learnt about censorship. A picture, whether it be painting or photography, is always communication. The artist communicates his truth, but he can only do so if the truth is also heard, if within society there are those able to hear and understand this truth. Those who regard art are also part of its meaning. So it is no accident that these photographs come from 1968 and 1972, from the Vietnam war and not the Korean (just as it is no accident that M.A.S.H., a satirical film about the Korean war, was only made in 1970), for this is the period when the post-war reconstruction is coming to an end and the class struggle is once again on the rise, finding its most momentous expression in May ‘68 in France.

The "spirit of the age", the Zeitgeist, can seem an ungraspable, nebulous notion. Yet when we consider this artistic production that grew out of wars brought to an end either because the working class revolted directly against the war itself (World War I), or because the workers revolted against the effects of the crisis of which the war was a part, and increasingly refused to fight (the Vietnam War), it seems to us clear that such art was only possible because within society there existed a working class with "radical chains", a class which is historically opposed to the present state of society, even if the workers themselves are not aware of it, much less the artists. Balzac, as Engels said, went beyond his own class prejudices in portraying truthfully what he saw: so the artists of the First World War bring to us something that goes beyond what they themselves were because they have teased out the truth that underlies the surface. The relationship between artistic expression within capitalism and the revolt against it, is by no means a mechanical one. Art is not great because it is socialist. Like science, art has its own dynamic and the artist’s first responsibility is to be true to himself. One is tempted to paraphrase what Engels’ said of science: ".... the more ruthlessly and disinterestedly [art] proceeds, the more it finds itself in harmony with the interests of the workers."

Jens

1The topography of the Museum has its own significance. The World War I exhibit is to be found immediately, on the ground floor, in a dramatic gallery housing aircraft and originals of the German V1 and V2 missiles from World War II. The war artists of the "Truth and Memory" exhibition are housed far more discreetly, in two galleries on opposite sides of the third floor.

2The fate of the Stalinist USSR’s agricultural production as a result of the ideological imposition of Lysenko’s theories of evolution is a counter-example. And of course, the fact that the scientific world often fails to live up to this necessity does not in any way invalidate it.

3Lenin, "On proletarian culture", 1920

4Read the whole book on Project Gutenberg

5See Paul Gough, A terrible beauty, Sansom & Co., 2010, p17

6Quote drawn from the generally thoughtful labels that accompany the exhibits.

7Quoted in this useful and intelligent review of Paul Gough’s book about Britain’s war artists, A terrible beauty.

8From one of the exhibition labels.

9It is significant also that he donated his entire collection of war paintings to the Imperial War Museum, feeling that it was morally wrong to profit from painting a war where so many suffered.

11See the article just cited.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace