Submitted by International Review on

In the first part of this article, published in the International Review n°150, we considered the role of women in the emergence of culture among our species Homo sapiens, on the basis of a critique of Christophe Darmangeat’s book Le communisme primitif n’est plus ce qu’il était.[1] In this second, and final, part we propose to examine what we feel to be one of the most fundamental problems posed by primitive communist society: how did the evolution of the genus Homo produce a species whose very survival is based on mutual confidence and solidarity, and more particularly what was woman’s role in this process. In doing so, we are basing ourselves substantially on the work of the British anthropologist Chris Knight.

Women’s role in primitive society

What then, according to Christophe Darmangeat, is women’s role and situation in primitive society? We cannot here repeat the entire argument contained in his book illustrated by a solid knowledge of the ethnography and striking examples. We will limit ourselves to a summary of its conclusions.

What then, according to Christophe Darmangeat, is women’s role and situation in primitive society? We cannot here repeat the entire argument contained in his book illustrated by a solid knowledge of the ethnography and striking examples. We will limit ourselves to a summary of its conclusions.

A first observation, which might seem to be obvious but in reality is not, is that the sexual division of labour is a universal constant of human society until the appearance of capitalism. Capitalism remains a fundamentally patriarchal society, based on exploitation (which includes sexual exploitation, the sex industry being one of the most profitable in modern times). Nonetheless, by directly exploiting the labour of women workers, and by developing machinery to a point where physical strength no longer plays a significant part in the labour process, capitalism has destroyed the division between “masculine” and “feminine” roles in social labour; in doing so, it has laid the foundations for a true liberation of women in communist society.[2]

The situation of women varies enormously among the different primitive societies which anthropologists have been able to study: in some cases, women suffer from an oppression which can bear more than a passing resemblance to class oppression, while in others they benefit not only from social esteem, but, hold a real social power. Where such power exists, it is based on the possession of rights over production, amplified by society’s religious and ritual life: to take just one example, Bronislav Malinowski (in Argonauts of the Western Pacific) tells us that the women of the Trobriand Islands not only have a monopoly on the work of horticulture (of great importance in the islands’ economy), but also over certain forms of magic, including those considered to be the most dangerous.[3]

However, while the sexual division of labour can cover very different situations from one people and mode of existence to another, there is one rule which is applied almost without exception: everywhere, it is men alone who have the right to bear arms and who therefore have a monopoly of warfare. As a result, they also have a monopoly over what one might call “foreign relations”. As social inequality began to develop, first with food storage then from the Neolithic onwards with full-blown agriculture and the emergence of private property and social classes, this specific situation of men allowed them little by little to dominate the whole of social life. In this sense, Engels was doubtless right to say in Origins of the family that “The first class opposition that appears in history coincides with the development of the antagonism between man and woman in monogamous marriage, and the first class oppression coincides with that of the female sex by the male”.[4] Nonetheless, one needs to avoid a too schematic view here, since even the first civilisations are far from being homogeneous in this respect. A comparative study of several early civilisations[5] shows us a broad spectrum: while the situation of women in meso-American and Inca societies was an unenviable one, amongst the Yoruba in Africa for example, women not only owned property and exercised a monopoly over certain industries, they also carried out large-scale trade on their own account and could even command diplomatic and military expeditions.

The question of mythology

Up to now we have remained, with Darmangeat, in the domain of the studies of “historically known” primitive societies (in the sense that they have been described by literate societies, from the ancient world to modern anthropology). This can teach us about the situation since the invention of writing in about the 4th millenium BCE, at best. But what are we to say of the 200,000 years of anatomically modern Man’s existence that precede it? How are we to understand the crucial moment when nature gave way to culture as the main determining factor in human behaviour, and how are genetic and cultural elements combined in human society? To answer this question, a purely empirical view of known societies is clearly inadequate.

One of the striking aspects of the study of early civilisations cited above, is that however varied the image they present of women’s condition, they all have legends which refer to women as chiefs, sometimes identified with goddesses. All of them have also seen a decline in women’s situation over time. One is tempted to see a general rule here: the further we go back in time, the more social authority women possess.

This impression is confirmed if we consider more primitive societies. On every continent, we find similar or even identical myths: once, women held power but since then men have stolen it, and now it is they who rule. Everywhere, women’s power is associated with the most powerful magic of all: the magic based on women’s monthly cycle and their menstrual blood, even to the point where we often encounter male rituals where men imitate menstruation.[6]

What can we deduce from this ubiquitous reality? Can we conclude that it represents a historical reality, and that there once existed a first society where women had a leading, if not necessarily a ruling role?

For Darmangeat, the answer is unequivocal and negative: “the idea that when myths speak of the past, they necessarily speak of a real past, however deformed, is an extremely bold, not to say untenable hypothesis” (p167). Myths “tell stories, which have meaning only in relation to the present situation which they have the function of justifying. The past of which they speak is invented solely in order to fulfil this objective” (p173).

This argument poses two problems.

The first, is that Darmangeat claims to be a marxist who remains faithful to Engels’ method while updating his conclusions. Yet while Engels’ Origins of the family is based extensively on Lewis Morgan, it also attributes considerable importance to the work of the Swiss jurist Johann Bachofen, who was the first to use mythology as a basis for understanding the relations between the sexes in the distant past. According to Darmangeat, Engels “is clearly cautious in his adoption of Bachofen’s theory of matriarchy (...) although he abstains from criticising the Swiss jurist’s theory, Engels only gives it a very qualified support. There is nothing surprising here: given his own analysis of the reasons for one sex’s domination of the other, Engels could hardly accept that before the development of private property, men’s domination over women was preceded by women’s domination over men; he envisaged the prehistoric relation between the sexes much more as a certain form of equality” (pp150-151).

Engels may well have remained prudent as to Bachofen’s conclusions, but he has no hesitation as to Bachofen’s method, which uses mythological analysis to uncover historical reality: in his Preface to the 4th edition of Origins of the family (in other words, having had plenty of time to restructure his work and include any corrections he thought necessary), Engels takes up Bachofen’s analysis of the Orestes myth (in particular the version of the Greek tragedian Aescylus), and concludes with this comment: “This new but undoubtedly correct interpretation of the Oresteia is one of the best and finest passages in the whole book (...) [Bachofen] was the first to replace the vague phrases about some unknown primitive state of sexual promiscuity by proofs of the following facts: that abundant traces survive in old classical literature of a state prior to monogamy among the Greeks and Asiatics when not only did a man have sexual intercourse with several women, but a woman with several men, without offending against morality (...) Bachofen did not put these statements as clearly as this, for he was hindered by his mysticism. But he proved them; and in 1861 that was a real revolution”.

This brings us to the second issue: how are myths to be explained? Myths are part of material reality just as much as any other phenomenon: they are therefore themselves determined by that reality. Darmangeat proposes two possible determinants: either they are simply “stories” invented by men to justify their domination over women, or they are irrational: “During prehistory, and for a long time afterwards, natural or social phenomena were universally and inevitably interpreted through a magico-religious prism. This does not mean that rational thought did not exist; it means that, even when it was present, it was always combined to a certain extent with an irrational discourse: the two were not perceived as different, still less as incompatible” (p319). What more need be said? All these myths built around the mysterious powers conferred by menstrual blood and the moon, not to mention women’s original power, are merely “irrational” and so outside the field of scientific explanation. At best, Darmangeat is ready to accept that myths must satisfy the human mind’s requirement of coherence;[7] but if that is the case, then unless we accept a purely idealist explanation in the original sense of the term, we must answer another question: where does this “demand” come from? For Lévi-Strauss, the source of the remarkable unity of primitive societies’ myths throughout the Americas was to be found in the innate structure of the human mind, hence the name “structuralism” given to his work and theory;[8] Darmangeat’s “requirement of coherence” looks like a pale reflection of Lévi-Strauss’ structuralism.

This leaves us without an any explanation on two crucial points: why do myths take the form they do, and how are we to explain their universality?

If they are no more than “stories” invented to justify male domination, then why invent such unlikely ones? If we take the Bible, the Book of Genesis gives us a perfectly logical explanation for male domination: God created men first! Logical that is, as long as we are prepared to accept the unlikely notion, which anyone can see contradicted year in year out, that woman came out of the body of man. Why then invent a myth which not only claims that women once held power, but which is accompanied by the demand that men continue to carry out the rites associated with this power, to the point of imagining male menstruation? This practice, attested throughout the world amongst hunter-gatherers where male domination is powerful, consists of men making their own blood flow in certain important rituals, by lacerating their members and in particular the penis, in a conscious imitation of menstrual bleeding.

Were this kind of ritual limited to one people, or one group of peoples, one might accept that this was nothing but an accidental and “irrational” invention. But when we find it spread throughout the world, on every continent, then if we are to remain true to historical materialism we must seek its social determinants.

At all events, it seems to us necessary from the materialist standpoint to take the myths and rituals which structure society seriously as sources of knowledge about it, something that Darmangeat fails to do.

The origin of women’s oppression

We can summarise Darmangeat’s thinking as follows: at the origins of women’s oppression lies the sexual division of labour, which systematically reserves to men big game hunting and the use of arms. However interesting his work, this seems to us to leave two questions unanswered.

It seems obvious enough that with the emergence of class society, based necessarily on exploitation and so on oppression, the monopoly of weapons is almost a self-sufficient explanation for male domination in it (at least in the long term; the overall process is doubtless more complex than that). Similarly, it seems a priori reasonable to suppose that the monopoly of weapons played a part in the emergence of male domination contemporaneous with the emergence of social inequalities prior to the appearance of class society properly so-called.

By contrast, and this is our first question, Darmangeat is much less clear why the sexual division of labour should reserve this role to men, since he himself tells us that “physiological reasons (...) have difficulty explaining why women were excluded from the hunt” (p314-315). Nor is it clear why the hunt, and the food which is its product, should be more prestigious than the product of gathering or of gardening, especially when the latter is the major source of social resources.

More fundamentally still, where does the first division of labour come from, and why should it be sexually based? Here we find Darmangeat losing himself in his own imagination: “We can imagine that even an embryonic specialisation allowed the human species to acquire a greater effectiveness than if its members had continued to exercise every activity without distinction (...) We can also imagine that this specialisation operated in the same direction, by strengthening social ties in general, and ties within the family group in particular”.[9] Well of course, “we can imagine”... but is this not rather what was supposed to be demonstrated?

As for the question “why the division of labour came about on the basis of sex”, for Darmangeat this “does not seem very difficult. It seems obvious enough that for the members of prehistoric society, this was the most immediately obvious difference”.[10] We can object here that while sexual differences must certainly have seemed “immediately obvious” to the first human beings, this is not a self-sufficient explanation for the emergence of a sexual division of labour. Primitive societies abound in classifications, notably those based on totems. Why should the division of labour not be based on totemism? This is obviously a mere flight of fancy – but no more so than Darmangeat’s hypothesis. More seriously, Darmangeat makes no mention of another extremely obvious difference, and one which is everywhere important in archaic societies: that of age.

When it comes down to it, Darmangeat’s book – despite its rather ostentatious title – does not enlighten us much. Women’s oppression is based on the sexual division of labour. So be it. But when we ask where this division comes from, we are “reduced to mere hypotheses, we can imagine that certain biological constraints, probably linked to pregnancy and breast-feeding, provided the physiological substrate for the sexual division of labour and the exclusion of women from the hunt” (p322).[11]

From genes to culture

At the end of his argument, Darmangeat leaves us with the following conclusion: at the origin of women’s oppression lies the sexual division of labour and despite everything, this division was itself a formidable step forward in labour productivity, even if its origins lie hidden in a far-off and inaccessible past.

Darmangeat seeks here to remain faithful to the marxist “model”. But what if the problem has been posed back to front? If we consider the behaviour of those primates that are closest to man, chimpanzees in particular, we find that it is only the males that hunt – the females are too busy feeding and looking after their young (and protecting them from the males: we should not forget that male primates often practice infanticide of other males’ children in order to gain access to the mother for their own reproductive needs). There is thus nothing specifically human about the “division of labour” between males who hunt and females who do not. The problem – what demands explanation – is not why the hunt is reserved to the male of Homo sapiens, but why it is the male sapiens, and only the male sapiens, that shares the produce of his hunt. What is striking, when we compare Homo sapiens to its primate cousins, is the range of often very strict rules and taboos, to be found from the burning deserts of Australia to the Arctic ice, which require the collective consumption of the product of the hunt. The hunter does not have the right to consume his own product, he must bring it back to camp for distribution to others. The rules that govern this distribution vary considerably from one people to another, but their existence is universal.

It is also worth pointing out that Homo sapiens’ sexual dimorphism is a good deal less than that of Homo erectus, which in the animal world is generally indicative of more equal relations between the sexes.

Everywhere, sharing food and collective meals are at the foundations of the first societies. Indeed, the shared meal has survived to modern times: even today it is impossible to imagine any great moment in life (birth, marriage, or burial) without a collective meal. When people come together in simple friendship, as often as not it is around a common meal, whether it be round the barbecue in Australia or around the restaurant table in France.

This sharing of food, which seems to come down to us from time immemorial is an aspect of human collective and social life very different from that of our far-off ancestors. We are confronted here with what the Darwinologist Patrick Tort has called the “reverse effect” of evolution, or what Chris Knight has described as a “priceless expression of the ‘selfishness’ of our genes”: the mechanisms described by Darwin and Mendel, and confirmed by modern genetics, have generated a social life where solidarity plays a central part, whereas these same mechanisms work through competition.[12]

This question of sharing seems fundamental to us, but it is only a part of a much broader scientific problem: how are we to explain the process which transformed a species whose changes in behaviour were determined by the slow rhythm of genetic evolution, into our own, whose behaviour – although of course it is still founded on our genetic heritage – changes thanks to the much more rapid evolution of culture? And how are we to explain that a mechanism based on competition has created a species which can only survive through solidarity: the mutual solidarity of women in childbirth and childrearing, the solidarity of men in the hunt, the solidarity of the hunters towards society as a whole when they contribute the product of the chase, the hale in solidarity with the old or injured no longer able to hunt or to find their own food, the solidarity of the old towards the young, in whom they inculcate not only the knowledge of nature and the world vital for survival, but the social, historical, ritual and mythical knowledge which make possible the survival of a structured society. This seems to us the fundamental problem posed by the question of “human nature”.

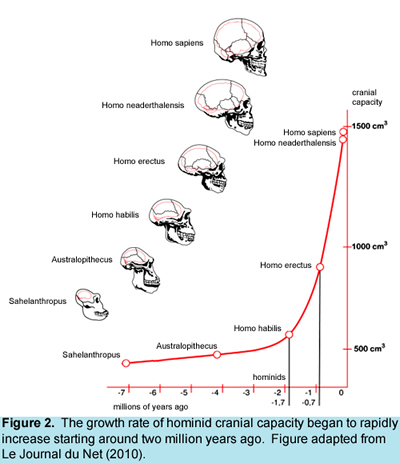

This passage from one world to another took place during a crucial period of several hundred thousand years, a period which we could indeed describe as “revolutionary”.[13] It is closely linked to the evolution of the human brain in size (and presumably in structure, though this is obviously much more difficult to detect in the archaeological record). The increase in brain size poses a whole series of problems for our evolving species, not the least of which is its sheer energy consumption: about 20% of an individual’s total energy intake, an enormous proportion.

Although the species undoubtedly gained from the process of encephalisation, it posed a real problem for the females. The size of the head means that birth must occur earlier, otherwise the baby could not pass through the mother’s pelvis. This in turn implies a much longer period of dependence in the infant born “prematurely” compared to other primates; the growth of the brain demands more nourishment, both structural and energetic (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates). We seem to be confronted with an insoluble enigma, or rather an enigma which nature solved only after a long period during which Homo erectus lived, and spread out of Africa, but apparently did not change very much either in behaviour or in morphology. And then comes a period of rapid evolution which sees an increase in brain size and the appearance of all the specifically human forms of behaviour: language, symbolic culture, art, the intensive use of tools and their great variety, etc.

There is another enigma to go with this one. We have noted the radical changes in the behaviour of the male Homo sapiens, but the physiological and behavioural changes in the female are no less remarkable, especially from the standpoint of reproduction.

There is a striking difference in this respect between the female Homo sapiens and other primates. Amongst the latter (and especially those that are the closest to us), the female generally signals to males in the clearest possible way her period of ovulation (and hence of greatest fecundity): genital organs highly visible, a “hot” behaviour especially towards the dominant male, a characteristic odour. Amongst humans, quite the opposite holds true: the sexual organs are hidden and do not change appearance during ovulation, while the human female is not even aware of being “on heat”.

At the other end of the ovulation cycle, the difference between Homo sapiens and other primates is equally striking: an abundant and visible menstrual flow, the contrary to chimpanzees for example. Since loss of blood implies a loss of energy, natural selection should in principle operate against abundant blood flow; it could be explained by some selected advantage – but what?

Another remarkable characteristic of human menstrual flow is its periodicity and synchronicity. Many studies have shown the ease with which groups of women synchronise their periods, and Knight reproduces a table of ovulation periods among primates which shows that only the human female has a period that perfectly matches the lunar cycle: why? Or is it just a coincidence?

One might be tempted to put all this to one side as irrelevant in explaining the appearance of language, and human specificity in general. Such a reaction, moreover, would be in perfect conformity with current ideology, which sees women’s periods as something, if not exactly taboo, at least somewhat negative: think of all those advertisements for “feminine hygiene” products which boast their ability to render the period invisible. To discover, in reading Knight’s book, the immense importance of menstrual blood and everything associated with it in primitive human society, is thus all the more startling for us as members of modern society. And the belief in the enormous power – for good and evil – of women’s periods, seems to be a universal phenomenon. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that menstrual flows “regulate” everything, up to and including the harmony of the universe.[14] Even among peoples where there is strong male domination, and where everything is done to devalue women, their periods inspire fear in men. Menstrual blood is considered “polluting” to a point which seems barely sane – and this is precisely a sign of its power. One is even tempted to conclude that men’s violence towards women is directly in proportion to the fear that women inspire in men.[15]

The universality of this belief is significant and demands explanation. We can imagine three possible ones:

- It might be the result of structures set in the human mind, as Lévi-Strauss’ structuralism suggested. Today, we would say rather that it is set in the human genetic heritage – but this seems to contradict everything that is known about genetics.

- It might be put down to the principle of “same cause, same effects”. Societies that are similar from the point of view of their relations of production and their technique produce similar myths.

- The similarity of myths might, finally, be put down to a common historical origin. If this were the case, given that the different societies where menstrual myths are expressed are widely separated geographically, the common origin must belong to a far distant past.

Knight favours the third explanation: he does indeed see the universal mythology around menstruation as something that is very old, going right back to the very origins of humanity.

The emergence of culture

How are these different questions linked together? What can be the link between women’s menstruation and collective hunting? And between the two and other emergent phenomena: language, symbolic culture, a society based on shared rules? These questions seem to us fundamental because all these “evolutions” are not isolated phenomena, but elements in a single process leading from Homo erectus to ourselves. The hyper-specialisation of modern science has the great disadvantage (largely recognised by scientists themselves) of making it very difficult to understand an entire process which cannot be encompassed by any single specialisation.

What we find most remarkable in Knight’s work is precisely this effort to bring together genetic, archaeological, paleontological and anthropological data in a “theory of everything” for human evolution, analogous to the efforts of the theoretical physicists who have given us super-string or quantum loop gravity theory.[16]

Let us therefore attempt to summarise this theory, known today as “sex strike theory”. To simplify and schematise, Knight hypothesises a modification in the behaviour, first of Homo females confronted by the difficulties of childbirth and childrearing: the females turn away from the dominant male to give their attention to secondary males in a sort of mutual help pact. The males accept to leave the females for the hunt, and to bring back the product of the chase; in return, they have an access to females, and therefore a chance to reproduce, that was denied to them by the dominant male.

This modification in the behaviour of the males – which at the outset, let us remember, is subject to the laws of evolution – is only possible under certain conditions, and two in particular: on the one hand, it is not possible for the males to find an access to females elsewhere; on the other, the males must be confident that they will not be supplanted in their absence. These are therefore collective behaviours. The females – who are the motive force in this evolutionary process – must maintain a collective refusal of sex to the males. This collective refusal is signalled visibly to the males, and other females by the menstrual flow, synchronised on a “universal” and visible event: the lunar cycle and the tides which accompany it in the semi-aquatic environment of the Rift valley where mankind first appeared.

Solidarity is born: amongst the females first of all, then also amongst the males. Collectively excluded from access to the females, they can put into practice an increasingly organised collective hunt of large game, which demands a capacity for planning and solidarity in the face of danger.

Mutual confidence is born from the collective solidarity within each sex, but also between the sexes: the females confident in male participation in childrearing, the males confident that they will not be excluded from the chance to reproduce.

This theoretical model allows us to resolve the enigma that Darmangeat leaves unanswered: why are women absolutely excluded from the hunt? According to Knight’s model, this exclusion can only be absolute, since if some females – and in particular those unencumbered by any young – were to join the hunt with the males, then the latter would have access to fertile females and would no longer be forced to share the product of the hunt with nursing females and their young. For the model to function, the females are obliged to maintain a total solidarity amongst themselves. From this starting point, it is possible to understand the taboo which maintains an absolute separation between women and the hunt, and which is the foundation for all the other taboos that revolve around menstruation and the blood of the hunt, and which forbid women from handling any cutting tool. The fact that this taboo, from being a source of women’s strength and solidarity, should in other circumstances become a source of social weakness and oppression, may seem paradoxical at first sight: in reality, it is a striking example of a dialectical reversal, one more illustration of the deeply dialectical logic of all evolutionary and historical change. [17]

The females who are most successful in imposing this new behaviour amongst themselves, and on the males, leave more descendants. The process of encephalisation can continue. The way is open toward the development of the human.

Mutual solidarity and confidence are thus born, not from a sort of beatific mysticism but on the contrary from the pitiless laws of evolution.

This mutual confidence is a precondition for the emergence of a true capacity for language, which depends on the mutual acceptance of common rules (rules as basic as the idea that a single word has the same meaning for me as it does for you, for example), and of a human society based on culture and law, no longer subjected to the slow rhythm of genetic evolution, but able to adapt much more rapidly to new environments. Logically, one of the first elements of the new culture is the transfer from the genetic into the cultural domain (if we can put it like this) of everything that made the emergence of this new social form possible: the most ancient myths and rituals thus turn around women’s menstruation (and the moon which guarantees their synchronisation), and its role in the regulation not only of the social but also the natural order.

A few difficulties, and a possible continuation

As Knight says himself, his theory is a sort of “origins myth” which remains a hypothesis. This obviously is not a problem in itself: without hypothesis and speculation, there would be no scientific advance; it is religion, not science, which tries to establish certain truths.

For ourselves, we would like to raise two objections to the narrative that Knight proposes.

The first concerns elapsed time. When Blood Relations was published in 1991, the first signs of artistic expression and therefore of the existence of a symbolic culture capable of supporting the myths and rituals which are at the heart of his hypothesis, dated back a mere 60,000 years. The first remains of modern humans dated back about 200,000 years: so what happened during the 140,000 “missing” years? And what could we envisage might be the precursor of a full-blown symbolic culture, for example among our immediate ancestors?

This does not so much put the theory into question, as pose a problem which calls for further research. Since the 1990s, excavations in South Africa (Blombos Caves, Klasies River, Kelders) seem to have pushed back the use of art and abstract symbolism to 80,000 or even 140,000 BCE;[18] as far as Homo erectus is concerned, the remains discovered at Dmanisi in Georgia in the early 2000s and dated back to about 1.8 million years, seem already to indicate a certain level of solidarity: one individual lived for several years without teeth, which suggests that others helped him to eat.[19] At the same time, their tools were still primitive and according to the specialists they did not yet practice big game hunting. This should not surprise us: Darwin in his day had already established that human characteristics such as empathy, the appreciation of beauty, and friendship, all exist in the animal realm, even if at a rudimentary level when compared to mankind.

Our second objection is more important and concerns the “motive force” pushing towards the increase in human brain size. Knight is more concerned with determining how this increase was possible, and so this question is not a central one for him: according to his interview at our congress, he has basically adopted the “increasing social complexity” theory, of human beings having to adapt to life in ever larger groups (this is the theory put forward by Robin Dunbar,[20] and also taken up by J-L Dessalles in his book Why we speak, whose arguments he presented at our previous congress). We cannot go into the details here, but this theory seems to us not without its difficulties. After all, the size of primate groups may vary from a dozen in the case of gorillas, to several hundred for Hamadryas baboons: it would therefore be necessary both to show why the hominins had social needs over and above those of baboons (this is far from being achieved), and to demonstrate that hominins lived in ever larger groups, up to the “Dunbar number” for example.[21]

On the whole, we prefer to tie the process of encephalisation and the development of language to the growing importance of “culture” (in the broadest sense) in human ability to adapt to the environment. There is often a tendency to think of culture solely in material terms (stone tools, etc.). But when we study the lives of hunter-gatherers in our own epoch, we are more than anything impressed by their profound knowledge of their natural surroundings: animal behaviour, the properties of plants, etc. Any hunting animal “knows” the behaviour of its prey, and can adapt to it up to a certain point. With human beings, however, this knowledge is not genetic but cultural, and must be transmitted from generation to generation. While mimicry may allow the transmission of a certain limited degree of “culture” (monkeys using a stick to fish for termites for example), it seems obvious that the transmission of human (or indeed proto-human) knowledge demands something more than mimicry.

One may also suggest that the more culture replaces genetics in determining our behaviour, the transmission of what we might call “spiritual” culture (myth, ritual, the knowledge of sacred places, etc.) takes on ever greater importance in maintaining group cohesion. This in turn leads us to link the development of language to another external sign, anchored in our biology: women’s “early” menopause followed by a long period where they are not reproductively active, which is another characteristic that human females do not share with their primate cousins.[22] How then could an “early” menopause have been favoured by natural selection, despite apparently limiting female reproductive potential? The most likely hypothesis seems to be that the menopausal female helps her daughter to better ensure the survival of her own grand-children, and therefore of her own genetic heritage.[23]

The problems we have just discussed concern the period covered by Blood Relations. But there is another difficulty which concerns the period of known history. It is obvious that the primitive societies of which we have knowledge (and which Darmangeat describes) are very different from Knight’s hypothetical first human societies. Just to take the example of Australia, whose aboriginal society is one of the most primitive known on the technical level, the persistence of myths and ritual practices which attribute great importance to menstruation goes side by side with complete male domination over women. If we suppose that Knight’s hypothesis is broadly correct, then how are we to explain what appears to be a veritable “male counter-revolution”? In his Chapter 13 (p449), Knight proposes a hypothesis to explain this: he suggests that it is the disappearance of the megafauna – species such as the giant Wombat – and a period of dry weather at the end of the Pleistocene, which disturbed hunting patterns and put an end to the abundance which he considers to be the material condition for primitive communism’s survival. In 1991, Knight himself wrote that this hypothesis remains to be tested in the archaeological record, and his own investigation is limited to Australia. At all events, it seems to us that this problem opens up a wide field of investigation which would allow us to envisage a real history of the longest period of humanity’s existence: from our origins to the invention of agriculture.[24]

The communist future

How can the study of human origins clarify our view of a future communist society? Darmangeat tells us that capitalism is the first human society which makes it possible to imagine an end to the sexual division of labour, and equality for women – an equality which is today set in law in a few countries, but which is nowhere an equality in fact: “while capitalism has neither improved nor worsened women’s lot as such, it is by contrast the first system which has made it possible to pose the question of their equality with men; and although it has proved unable to make this equality a reality, it has nonetheless brought together the elements which will bring it into being”.[25]

Two criticisms seem to us in order here: the first is that it ignores the immense importance of women’s integration into the world of wage labour. Despite itself, capitalism has given working-class women, for the first time in the history of class society, a real material independence from men, and hence the possibility of taking part on an equal footing with men in the struggle for the liberation of the proletariat, and so of humanity as a whole.

The second concerns the very notion of equality. This notion is stamped with the mark of the democratic ideology inherited from capitalism, and it is not the goal of a communist society which will, on the contrary, recognise the differences between individuals and – to use Marx’s expression – “inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!”.[26] Now, outside the domain of science fiction, women have both an ability and a need that men will never have: to give birth.[27] This capacity has to be exercised, or human society has no future, but it is also a physical function and therefore a need for women.[28] A communist society must therefore offer every woman who desires it the possibility of giving birth with joy, in confidence that her child will be welcomed into the human community.

Here perhaps we can draw a parallel with the evolutionist vision that Knight proposes. Proto-women launched the process of evolution towards Homo sapiens and symbolic culture, because they could no longer raise their children alone: they had to oblige the males to provide material aid to childbearing and the education of the young. In doing so, they introduced into human society the principle of solidarity among women occupied by their children, among men occupied by the hunt, and between men and women sharing their joint social responsibilities.

Today, we are confronting a situation where capitalism reduces us more and more to the status of atomised individuals, and childbearing women suffer most as a result. Not only does the “rule” of capitalist society reduce the family to its smallest expression (mother, father, children), the general disintegration of social life means that more and more women find themselves bringing up even their very young children alone, and the need to find work often distances them from their own mothers, sisters, or aunts who once used to be the natural support network for any woman with small children. The “world of work” is pitiless for women with children, obliged to wean their infants after a few months at best (depending on the maternity holidays available, if any) and to leave them with a nurse, or – if they are unemployed – to find themselves cut off from social life and forced to look after their babies alone on the most limited resources.

In a sense, working class women today find themselves in a situation analogous to their distant ancestors – and only a revolution can improve their situation. Just as the “revolution” that Knight hypothesises allowed women to surround themselves with the social support first of other women, then of men, for the bearing and education of their children, so the communist revolution to come must put at its heart the support for women’s childbearing, and the collective education of children. Only a society which gives a privileged place to its children and youth can claim to offer a hope for the future: from this standpoint, capitalism stands condemned by the very fact that a growing proportion of its youth is considered “surplus to requirements”.

Jens

[1] Éditions Smolny, Toulouse 2009 et 2012. Unless otherwise stated, quotes and page references are taken from the first edition.

[2] Darmangeat puts forward some interesting ideas on the increased importance of physical strength in determining sex roles following the invention of agriculture (ploughing for example).

[3] Darmangeat insists, no doubt rightly, that involvement in social production is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for ensuring women a favourable situation in society.

[4] In the section on “The monogamous family”.

[5] Bruce Trigger, Understanding early civilizations.

[6] Knight’s book devotes a section to "male menstruation" (p428). Also available in PDF on Chris Knight’s website.

[7] “The human mind has its requirements, one of which is coherence” (p319). We will not here go into the question of where these “requirements” come from, nor why they take their particular forms – questions which Darmangeat leaves unanswered.

[8] For a glowing, but critical account of Lévi-Strauss’ thinking, the reader can refer to Knight’s chapter on “Levi-Strauss and ‘The Mind’”.

[9] C. Darmangeat, 2nd edition, pp214-215

[10] Idem.

[11] Oddly enough, Darmangeat himself only a few pages previously points out that in certain North American Indian societies, under special conditions, “women could do everything; they mastered the whole range of both feminine and masculine activity” (p314).

[12] See the article on Patrick Tort’s L’effet Darwin, and Chris Knight’s article on solidarity and the selfish gene.

[13] Cf. “The great leaps forward” by Anthony Stigliani

[14] It is interesting to note that in French (and Spanish) the word for a woman’s period is “les règles” (or, “la regla”), which also means “the rules”.

[15] This is a theme which recurs throughout Darmangeat’s book. See amongst others the example of the Huli in New Guinea (p222, 2nd edition).

[16] And better still, to have rendered this theory readable and accessible to the non expert reader.

[17] Hence, when Darmangeat tells us that Knight’s thesis “says not a word about the reasons why women have been systematically and completely forbidden to hunt and to handle weapons”, we cannot help wondering whether he has read the book to its conclusion.

[19] See the article published in La Recherche: "Etonnants primitifs de Dmanisi"

[20] See for example Dunbar’s The human story. Robin Dunbar explains the evolution of language through the increase in the size of human groups; language appeared as a less costly form of grooming, through which our primate cousins maintain their friendships and alliances. “Dunbar’s number” has entered anthropological theory as the greatest number of close relationships that the human brain is capable of retaining (about 150); Dunbar considers that this would have been the maximum size of the first human groups.

[21] The Hominins (the branch of the evolutionary tree to which modern humans belong) diverged from the Panins (the branch containing chimpanzees and bonobos) some 6-9 million years ago).

[22] cf. “Menopause in non-human primates” (US National Library of Medecine).

[23] See this summary of the “grandmother hypothesis”.

[24] Some work has already been done in this direction, in a country at the antipodes of Australia, by the anthropologist Lionel Sims, in an article titled “The ‘Solarization’ of the moon: manipulated knowledge at Stonehenge” published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal 16:2.

[25] Darmangeat, op.cit., p426.

[26] It is not for nothing that Marx wrote, in his Critique of the Gotha programme, “Right, by its very nature, can consist only in the application of an equal standard; but unequal individuals (and they would not be different individuals if they were not unequal) are measurable only by an equal standard insofar as they are brought under an equal point of view, are taken from one definite side only -- for instance, in the present case, are regarded only as workers and nothing more is seen in them, everything else being ignored”.

[27] One of today’s very rare original science fiction writers, Iain M Banks, has created a pan-galactic society (“The Culture”) which is communist in all but name, where humans have reached such a degree of control over their hormonal functions that they are able to change sex at will, and therefore to give birth also.

[28] Which does not of course mean that all women would want, still less should be obliged, to give birth.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace