Submitted by International Review on

The press and television news around the world regularly send images of Mexico in which fighting, corruption and murder resulting from the “war against drug trafficking” are brought to the fore. But all this appears as a phenomenon alien to capitalism or abnormal, whereas in fact all the barbaric reality that goes with it is deeply rooted in the dynamics of the current system of exploitation. It is, in its full extent, the behaviour of the ruling class that is revealed, through competition and heightened political rivalries between its various fractions. Today, such a process of plunging into barbarism and the decomposition of capitalism is effectively dominant in certain regions of Mexico.

At the beginning of the 1990s, we said that “Amongst the major characteristics of capitalist society's decomposition, we should emphasise the bourgeoisie's growing difficulty in controlling the evolution of the political situation.”1 This phenomenon appeared more clearly in the last decade of the 20th century when it became a major trend.

It is not only the ruling class that is affected by decomposition; the proletariat and other exploited classes also suffer its most pernicious effects. In Mexico, mafia groups and the actual government enrol, for the war in which they are engaged, elements belonging to the most impoverished sectors of the population. The clashes between these groups, which indiscriminately hit the population, leaving hundreds of victims on the casualty list, the government and mafias call “collateral damage.” The result is a climate of fear that the ruling class has used to prevent and contain social reactions to the continuous attacks on the living conditions of the population.

Drug trafficking and the economy

In capitalism, drugs are nothing more than a commodity whose production and distribution necessarily requires labour, even if it is not always voluntary or waged. Slavery is common in this environment, which not only employs the voluntary and paid labour of a lumpen milieu for criminal activities, but also of labourers and others like carpenters (for example, for the construction of houses and shops) who are forced, in order to survive in the misery offered by capitalism, to serve the capitalist producers of illegal goods.

What is experienced today in Mexico has already existed (and still exists) in other parts of the world: the mafias profit from this misery, and their collusion with the state structures allows them to “protect their investment” and their activities in general. In Colombia, in the 1990s, the investigator H. Tovar-Pinzón gave a number of factors to explain why poor peasants became the first accomplices of the drug trafficking mafias: “A property produced, for example, ten cargoes of corn per year which permitted a gross receipt of 12,000 Colombian pesos. This same property could produce a hundred arrobas of coca, which represented for the owner a gross revenue of 350,000 pesos per year. Why not change the crop when one can gain thirty times more?”.2

What happened in Colombia has expanded across the whole of Latin America, drawing into drug trafficking, not only the peasant proprietors, but also the great mass of landless labourers who sell their labour power to them. This great mass of workers becomes easy prey to the mafia, because of the extremely low wages granted by the legal economy. In Mexico, for example, a labourer employed to cut sugar cane receives little more than two dollars per ton (27 pesos) and will see his wage increased when he produces an illegal commodity. In doing so, a large portion of workers employed in this activity loses its class condition. These workers are increasingly implicated in the world of organised crime and in direct contact with the gunmen and drug carriers with whom they share directly a daily life in a context of the trivialisation of murder and crime. Closely involved in this atmosphere, the contagion leads them progressively towards lumpenisation. This is one of the harmful effects of advanced decomposition directly affecting the working class.

There are estimates that the drug trafficking mafias in Mexico employ 25% more people than McDonald's worldwide.3 It should also be added that beyond the use of farmers, mafia activity involves racketeering and prostitution imposed on hundreds of young people. Today, drugs are an additional branch of the capitalist economy, that is to say that exploitation is present in it as in any other economic activity but, in addition, the conditions of illegality push competition and the war for markets to take much more violent forms.

The violence to gain markets and increase profits is all the fiercer with the importance of the gain. Ramón Martinez Escamilla, member of the Economic Research Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, believes that “the phenomenon of drug trafficking represents between 7 and 8 % of Mexico’s GDP”.4 These figures, compared to the 6% of Mexico’s GDP which represents the fortune of Carlos Slim, the biggest tycoon in the world, give an indication of the growing importance of the drug trade in the economy, permitting us to deduce the barbarity that it engenders. Like any capitalist, the drug trafficker has no other objective than profit. To explain this process, it is enough to recall the words of the trade unionist Thomas Dunning (1799-1873), quoted by Marx:

“With adequate profit, capital is very bold. A certain 10 per cent will ensure its employment anywhere; 20 per cent certain will produce eagerness; 50 per cent, positive audacity; 100 per cent will make it ready to trample on all human laws; 300 per cent, and there is not a crime at which it will scruple, nor a risk it will not run, even to the chance of its owner being hanged. If turbulence and strife will bring a profit, it will freely encourage both.”5

Based on contempt for human life and on exploitation, these vast fortunes certainly find refuge in tax havens but are also used directly by the legal capitalists who are responsible for the task of laundering them. Examples abound to illustrate this, such as the entrepreneur Zhenli Ye Gon, or more recently, the financial institution HSBC. In these two examples, it was revealed that the individual or institution was laundering the vast fortunes of the drug cartels, whether it was for the promotion of political projects (in Mexico and elsewhere) or for “honourable” investments.

Edgar Buscaglia6 states that companies of all kinds have been “designated as dubious by intelligence agencies in Europe and the United States, including the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the U.S. Treasury Department, but nobody has wanted to undermine Mexico, basically because many of them fund election campaigns.”7

There are other marginal processes (but no less significant) that enable the integration of the mafia in the economy, such as the violent depopulation of properties and of vast territories, to the extent that some areas of the country are now “ghost towns”. Some figures suggest the displacement, in recent years, of a million and a half people fleeing “the war between the army and the narcos.”8

It is essential to point out the impossibility, for the plans of the drug mafias, of existing outside the realm of the states. These are the structures that protect and help them move their money towards the financial giants, but are also the seat of the government teams of the bourgeoisie who mix their interests with those of drug cartels. It is obvious that the mafia could hardly have as much business if they did not receive the support of sectors of the bourgeoisie involved in the governments. As we have argued in the “Theses on Decomposition”, “it is more and more difficult to distinguish the government apparatus from gangland.”9

Mexico, an example of advanced capitalist decomposition

Since 2006, almost sixty thousand people have been killed, either by the bullets of the mafia units or those of the official army; a majority of those killed were victims of the war between drug cartels, but this does not diminish the responsibility of the state, whatever the government says. It is impossible to blame one or the other, because of the links between the mafia groups and the state itself. If difficulties have been growing at this level, it is precisely because the fractures and divisions within the bourgeoisie are amplified and, at any time, any place, can become a battleground between fractions of the bourgeoisie; of course, the state structure itself is also a place to where these conflicts are expressed. Each mafia group emerges under the leadership of a fraction of the bourgeoisie, and so the economic competition that these political quarrels create makes these conflicts grow and multiply day by day.

In the 19th century, during the ascendant period of capitalism, the drugs trade (opium for example) was already the cause of political difficulties leading to wars, revealing the barbaric essence of this system in the states’ direct involvement in the production and distribution of goods such as drugs. However, such a situation was still inseparable from the strict vigilance and the maintenance of a framework of firm discipline on this business by the state and the dominant class, allowing it to reach political agreements and avoiding anything that that would weaken the cohesion of the bourgeoisie.10 Thus, even if the “Opium War” - declared principally by the British state - illustrated a behavioural trait of capital, we can understand why the drug trade was not, however, a dominant phenomenon of the 19th century.

The importance of drugs and the formation of mafia groups become increasingly important during the decadent phase of capitalism. While the bourgeoisie tried to limit and adjust by laws and regulations the cultivation, preparation and trafficking of certain drugs during the first decades of the 20th century, this was only in order to properly control the trade of this commodity.

The historical evidence shows that “drug industry” is not an activity divorced from the bourgeoisie and its state. Rather, it is this same class that is responsible for expanding its use and profiting from the benefits it provides, and at the same time expanding its devastating effects in humans. States in the 20th century, have massively distributed drugs to armies. The United States gives the best example of such use to “stimulate” the soldiers during the war: Vietnam was a huge laboratory and it is not surprising that it was effectively Uncle Sam who encouraged the demand for drugs in the 1970s, and responded by boosting their production in the countries of the periphery.

At the beginning of the second half of the 20th century in Mexico, the importance of the production and distribution of drugs was still far from being significant and remained under the strict control of government authorities. The market was also tightly controlled by the army and the police. From the 1980s, the American government encouraged the development of the production and consumption of drugs in Mexico and throughout Latin America.

The “Iran-Contra” affair (1986) revealed that the government of Ronald Reagan, to overcome reductions in the budget to support armed bands opposed to the Nicaraguan government (the “contras”), used funds from the sale of arms to Iran and, especially, from drug trafficking via the CIA and the DEA. The government of the United States pushed the Colombian mafias to increase production, even deploying, to this end, military and logistical support to the governments of Panama, Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, Colombia and Guatemala, to facilitate the passage of this coveted commodity. To “expand the market”, the American bourgeoisie began to produce cocaine derivatives much more cheaply and therefore easier to sell massively, despite being more devastating.

These same practices, used by the American ‘godfather’ to raise funds to enable it to carry out its putchist adventures, have also been used in Latin America to fight against the guerrillas. In Mexico, the so-called “dirty war” waged by the state in the 1970s and 80s against the guerrillas was financed by the money coming from drugs. The army and paramilitary groups (such as the White Brigade or the Jaguar Group) then had carte blanche to murder, kidnap and torture. Some military projects like “Operation Condor” (which supposedly targeted drug production), were actually directed against the guerrillas and served at the same time to protect poppy and marijuana crops.

At that time, the discipline and cohesion of the Mexican bourgeoisie permitted it to keep the drug market under control. Recent journalistic enquiries say that there was absolutely no drug shipment that was beyond the control and supervision of the army and federal police.11 The state assured, under a cloak of steel, the unity of all sectors of the bourgeoisie, and when a group or individual capitalist showed disagreements, it was settled peacefully through privileges or power sharing. Thus was unity maintained in the so-called “revolutionary family.”12

With the collapse of the Eastern imperialist bloc the unity of the opposing bloc led by the United States also disappeared, which in turn provoked a growth of “every man for himself” among the different national fractions of certain countries. In Mexico, this breakdown showed itself in the dispute in broad daylight between fractions of the bourgeoisie at all levels: parties, clergy, regional governments, federal governments... Each fraction was trying to gain a greater share of power, without any of them taking the risk of putting into question the historic discipline behind the United States.

In the context of this general brawl, opposing bourgeois forces have fought over the distribution of power. These internal pressures have led to attempts to replace the ruling party and “decentralise” the responsibilities of law enforcement. Thus local authorities, represented by the state governments and the municipal presidents have declared their regional control. This, in turn, has added to the chaos: the federal government and each municipality or region, in order to reinforce its political and economic control, has associated itself with a particular mafia band. Each ruling fraction protects and strengthens this or that cartel according to its interests, thus ensuring impunity, which explains the violent arrogance of the mafias.

The magnitude of this conflict can be seen in the settling of accounts between political figures. It is estimated for example that in the last five years, twenty-three mayors and eight municipal presidents have been assassinated, and the threats made to secretaries of state and candidates are innumerable. The bourgeois press tries to pass off the people murdered as victims who, in the majority of cases, have been the subjects of a settling of scores between rival gangs or within these bands, for treachery.

By analysing these events we can understand that the drug problem cannot be resolved within capitalism. To limit the excesses of barbarism, the only solution for the bourgeoisie is to unify its interests and to regroup around a single mafia band, thus isolating the other bands to keep them in a marginal existence.

The peaceful resolution of this situation is very unlikely, especially because of the acute division between bourgeois factions in Mexico, making it difficult and unlikely to achieve even a temporary cohesion permitting a pacification. The dominant trend seems to be the advance of barbarism... In an interview dated June 2011, Buscaglia estimated the magnitude of drug trafficking in the life of the bourgeoisie: “Nearly 65% of electoral campaigns in Mexico are contaminated by money from organised crime, mainly drug trafficking”.13

Workers are the direct victims of the advance of capitalist decomposition expressed through phenomena such as “the war against drugs” and they are also the target of the economic attacks imposed by the bourgeoisie faced with the deepening of the crisis; this is undoubtedly a class that suffers from great poverty, but it is not a contemplative class, it is a body capable of reflecting, of becoming conscious of its historical condition and reacting collectively.

Decay and crisis ... capitalism is a system in putrefaction

Drugs and murder are major news items both inside and outside the country, and if the bourgeoisie gives them such importance it is also because this allows it to disguise the effects of the economic crisis.

The crisis of capitalism did not originate in the financial sector, as claimed by the bourgeois “experts”. It is a profound and general crisis of the system that spares no country. The active presence of mafias in Mexico, although it weighs heavily on the exploited, does not erase the effects on them of the crisis; quite the contrary, it makes them worse.

The main cause of the tendencies towards recession affecting global capitalism is widespread insolvency, but it would be a mistake to believe that the weight of sovereign debt is the only indicator to measure the advance of the crisis. In some countries, such as Mexico, the weight of indebtedness does not create major problems yet, though in the last decade, according to the Bank of Mexico, sovereign debt has increased by 60% to reach 36.4% of GDP at the end 2012 according to forecasts. This amount is obviously modest when compared to the level of debt of countries like Greece (where it has reached 170% of GDP), but does this imply that Mexico is not exposed to the deepening crisis? The answer of course is no.

Firstly, the fact that indebtedness is not as important in Mexico than in other countries does not mean that it will not become so.

The difficulties of the Mexican bourgeoisie in reviving capital accumulation are illustrated particularly in the stagnation of economic activity. GDP is not even able to reach its 2006 levels (see Figure 1) and, moreover, the recent fleeting embellishment has concerned the service sector, especially trade (as explained by the state institution in charge of statistics, the INEGI). Furthermore, it must also be taken into consideration that if this sector boosts domestic trade (and permits GDP to grow), this is because consumer credit has increased (at the end of 2011 the use of credit cards increased by 20 % compared to the previous year).

The mechanisms used by the ruling class to confront the crisis are neither new nor unique to Mexico: increasing levels of exploitation and boosting the economy through credit. The application of such measures helped the United States in the 1990s to give the illusion of growth. Anwar Shaikh, a specialist in the American economy, explains: “The main impetus for the boom came the dramatic fall in the rate of interest and the spectacular collapse of real wages in relation to productivity (growth of the rate of exploitation), which together raised significantly the rate of profit of the company. Both variables played different roles in different places...”14

The mechanisms used by the ruling class to confront the crisis are neither new nor unique to Mexico: increasing levels of exploitation and boosting the economy through credit. The application of such measures helped the United States in the 1990s to give the illusion of growth. Anwar Shaikh, a specialist in the American economy, explains: “The main impetus for the boom came the dramatic fall in the rate of interest and the spectacular collapse of real wages in relation to productivity (growth of the rate of exploitation), which together raised significantly the rate of profit of the company. Both variables played different roles in different places...”14

Such measures are repeated at the pace of the advance of the crisis, even though their effects are more and more limited, because there is no alternative but to continue to use them, further attacking the living conditions of the workers. Official figures, for what they’re worth, attest to the precariousness of these solutions. It is not surprising that the health of Mexican workers is based on the cheapest available calories in sugar (the country is the second largest consumer of soft drinks after the United States, every Mexican consuming some 150 litres on average per year) or cereals.

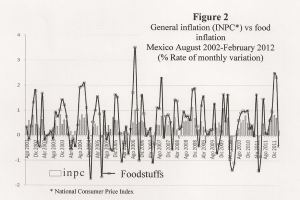

It is therefore not surprising that Mexico is a country whose adult population is more prone to problems of obesity which culminate in chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. Degradation of living conditions has reached such extremes that more children between 12 and 17 are forced to work (according to CEPALC, 25% in rural areas and 15% in the city). By compressing wages, the bourgeoisie has managed to claw back financial resources destined for consumption by the workers, seeking to increase the mass of surplus value appropriated by the capital. This situation is even more serious for the living conditions of the working class, as shown in Figure 2, because food prices are rising faster than the general price index used by the state to assert that the problem of inflation is under control.

Spokespersons for Latin American governments start from the principle that if economic conflicts affect the central countries (the United States and Europe), the rest of the world is untouched by this dynamic, especially as the IMF and the ECB are supplied with liquidity by the governments of these regions, including Mexico. But this does not mean at all that these economies are not threatened by the crisis. These same insolvency processes that spread throughout Europe today were the lot of Latin America during the 1980s and, with them, the severe measures arising from draconian austerity plans (which gave rise to what was called the Washington Consensus).

Spokespersons for Latin American governments start from the principle that if economic conflicts affect the central countries (the United States and Europe), the rest of the world is untouched by this dynamic, especially as the IMF and the ECB are supplied with liquidity by the governments of these regions, including Mexico. But this does not mean at all that these economies are not threatened by the crisis. These same insolvency processes that spread throughout Europe today were the lot of Latin America during the 1980s and, with them, the severe measures arising from draconian austerity plans (which gave rise to what was called the Washington Consensus).

The depth and breadth of the crisis can be manifested differently in different countries, but the bourgeoisie uses the same strategies in all countries, even those who are not strangled by increasing sovereign debt.

The plans to reduce costs that the bourgeoisie applies less and less discreetly, the layoffs and increased exploitation, cannot in any way promote any recovery.

The rates of unemployment and impoverishment achieved by Mexico help us to understand how the crisis extends and deepens elsewhere. Coparmex, the employers' organisation, recognises that in Mexico 48% of the economically active population is in “underemployment”,15 which in more straightforward language means in a precarious situation: low wages, temporary contracts, days getting longer and longer without any medical insurance. This mass of the unemployed and precarious is the product of “labour flexibility” imposed by the bourgeoisie to increase exploitation and to push the main effects of the crisis onto our shoulders.

Poverty and exploitation are the drivers of discontent

Many regions, mainly in rural areas, which are subject to curfew and constant supervision by armed patrols, whether military, police or mafia (if not both), and who murder under the slightest pretext, make life a nightmare for the exploited. To this are added the permanent attacks on the economic level. In early 2012, the Mexican bourgeoisie announced a “labour reform” which, as elsewhere in the world, will bring the cost of the labour force down to a more attractive level for capital, thus reducing production costs and further increasing the rate of exploitation.

The “labour reform” aims to increase the rates and hours of work, but also to lower wages (reduction of direct wages and elimination of substantial parts of the indirect wage), the project also providing for increases in the number of years of service required to qualify for retirement.

This threat began to materialise in the education sector. The state has chosen this area to make an initial attack that will be a warning to others elsewhere. It can afford to do this because although the workers are numerous and have a great tradition of militancy, they are very tightly controlled by the trade union structure, both formal (National Union of Education Workers – SNTE) and “democratic” (National Coordination of Education Workers – CNTE). Thus the government was able to deploy the following strategy: first causing discontent by announcing a “universal assessment”16, and then staging a series of manoeuvres (interminable demonstrations, negotiations separated by region...), relying on the unions to exhaust, isolate and thus defeat the strikers, convincing them of the futility of the “struggle “and so demoralising and intimidating all workers.

Although teachers have been the subject of special treatment, the “reforms” apply nevertheless gradually and unobtrusively to all workers. The miners, for example, are already experiencing these attacks which reduce the cost of the labour force and make their working conditions more precarious. The bourgeoisie considers it normal that, for a pittance (the maximum salary a miner can claim is $455 per month), workers spend in the pits and galleries long and intensive working days which often well exceed eight hours, in unspeakable safety conditions worthy of those that prevailed in the 19th century. It is this that explains, on the one hand, why the profit rate of mining companies in Mexico is among the highest, and on the other, the dramatic increase in “accidents” in the mines, with their growing tally of wounded and dead. Since 2000, in the one state of Coahuila, the most active mining area in the country, more than 207 workers have died as a result of collapsing galleries or firedamp explosions.

This misery, to which is added the criminal activities of the governments and the mafias, provokes a growing discontent among the exploited and oppressed which begins to express itself, even if it is still with great difficulties. In other countries such as Spain, Britain, Chile, Canada, the streets have been overrun with demonstrations expressing the courage to fight against the reality of capitalism, even though this was not yet clearly the force of a class in society, the working class.

In Mexico, the mass protests called by students of the “#yo soy 132” (“I am 132”) movement, although they have been framed from the outset by the electoral campaign of the bourgeoisie for the presidential elections, are nevertheless the product of a social unrest which is smouldering. It is not to console ourselves that we affirm this; we don’t delude ourselves with the illusion of a working class advancing unabated in a process of struggle and clarification, we are just trying to understand reality. We need to take into account that the development of mobilisations throughout the world is not homogeneous and that within them, the working class as such does not assume a dominant position. Because of its difficulty to recognise itself as a class in society with the capacity to constitute a force within it, the working class lacks confidence in itself, is afraid to launch itself in the struggle and to lead that struggle. Such a situation promotes, within these movements, the influence of bourgeois mystifications which put forward reformist “solutions” as possible alternatives to the crisis of the system. This general trend is also present in Mexico.

It is only by recognising the difficulties faced by the working class that we can understand that the movement animating the creation of the group “# yo soy 132” also expresses the disgust with governments and parties of the ruling class. The latter was able to react very quickly to the threat by linking the group to the false hopes raised by the elections and democracy, and converting it into a hollow organ, useless to the struggle of the exploited (who were coming closer to this group believing that it had found a way to fight), but very useful to the bourgeoisie which continues to use “#yo soy 132” to divert the combativity of young workers outraged by the reality of capitalism.

The ruling class knows perfectly well that increasing attacks will inevitably provoke a response from the exploited. José A Gurría, Secretary-General of the OECD, expressed this in these terms on February 24: “What can happen when you mix the decline in growth, high unemployment and growing inequality? The result can only be the Arab Spring, the Indignants of Puerta del Sol and those in Wall Street”. That is why, faced with this latent discontent, the Mexican bourgeoisie promotes the campaign protesting the election of Pena Nieto1718 to the presidency of the republic, a unifying slogan that sterilises any combativity, along with the more radical statements of Lopez Obrador181819 and of “# yo soy 132” ensuring that nothing will go further than the defence of democracy and its institutions.

Accentuated by the adverse effects of decomposition, the capitalist crisis has generalised the impoverishment of the proletariat and other oppressed but has thereby shown the naked reality, in all its cruelty: capitalism can offer us nothing but unemployment, poverty, violence and death.

The profound crisis of capitalism and the destructive advance of decomposition announces the dangers that represent the survival of capitalism, affirming the imperative necessity of its destruction by the only class capable of confronting it, the proletariat.

Rojo, March 2012

1 1. See International Review n 62, “Decomposition, final phase of the decadence of capitalism” point 9.

2 2. Nueva sociedad no. 130, Columbia, 1994, “The economy of coca in Latin America. The Colombian paradigm” (our translation).

3 3. Cf. See “Narco SA, una empresa global” on www.cnnexpansion.com.

44. La Jornada , 25 June 2010 (our translation).

55. Karl Marx, Capital, Volume I, “The development of capitalist production”; Section VIII, “Primitive accumulation”, Chapter XXXI, “Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist”, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch31.htm

66. International Programme Coordinator for Justice and Development at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico (ITAM).

77. La Jornada , 24 March, 2010 (our translation).

88. In the northern states of the country such as Durango, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas, some areas are considered “ghost towns” after being abandoned by the population. Villagers who were engaged in agriculture have been obliged to flee, liquidating their property at low prices in the best case or abandoning it altogether The plight of workers is even more serious because their mobility is limited due to lack of means, and when they manage to flee to other areas, they are forced to live in the worst conditions of insecurity, in addition to continuing to repay loans for housing they were forced to abandon.

99. �See International Review no. 62, op. cit., point 8.

1010. Even today, for some countries such as the United States, despite being the largest consumers of drugs, the armed clashes and the casualties they cause are mainly concentrated outside their borders.

1111.� See Anabel Hernández, Los del narco Señores (“Drug Lords”), Edition Grijalbo, Mexico 2010.

1212.� This is the so-called unity that the bourgeoisie had achieved with the creation of the National Revolutionary Party (PNR, 1929), which was consolidated by transforming it into the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that remained in power until 2000.

1313.� See “Edgardo Buscaglia: el fracaso de la guerra contra el narco - Por el diario Alemán Die Tageszeitung” on nuestraaparenterendicion.com

1414. In “The first great depression of the 21st century” 2010.

15 The official institution (INEGI) for its part calculates that the rate of “informal” workers is 29.3%.

16 “The universal assessment” is part of the “Alliance for Education Quality” (ACE). This is not only to impose an evaluation system to make workers compete with each other and reduce the number of positions, but also to increase the workload, compress wages, facilitate rapid redundancy protocols and low-cost pensions...

17. Leader of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (social democrat).

18. Leader of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (left social democrat).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace