Submitted by ICConline on

A few months ago, the world seemed to be taking a step towards a nuclear confrontation over North Korea, with Trump’s threats of “fire and fury” and North Korea’s Great Leader boasting of its capacity for massive retaliation. Today the North and South Korean leaders are holding hands in public and promising us real steps towards peace; Trump will hold his face-to-face meeting with Kim Jong-un on 12 June in Singapore.

Only weeks ago, there was talk of World War Three breaking out over the war in Syria, this time with Trump warning Russia that his smart missiles were on their way in response to the chemical weapons attack in Douma. The missiles were launched, no Russian military units were hit, and it looked like we were back to the “normal”, everyday forms of slaughter in Syria.

Then Trump stirred the pot again, announcing that the US would be pulling out of the “Bad Deal” Obama made with Iran over its nuclear weapons programme. This immediately created divisions between the US and other western powers who consider that the agreement with Iran was working, and who now face the threat of US sanctions if they continue to trade or cooperate with Iran. And in the Middle East itself, the impact was no less immediate: for the first time a salvo of missiles was launched against Israel by Iranian forces in Syria, not merely their local proxy Hezbollah. Israel – whose Prime Minister Netanyahu had not long before performed a song and dance about Iranian violations of the nuclear treaty – reacted with its habitual speed and ruthlessness, hitting a number of Iranian bases in southern Syria.

Meanwhile Trump’s recent declaration of support for Jerusalem as the capital of Israel has inflamed the atmosphere on the occupied West Bank, particularly in Gaza, where Hamas has encouraged “martyrdom” protests and in one bloody day alone, Israel obliged by massacring more than 60 demonstrators (eight of them aged under 16) and wounding over 2,500 more who suffered injuries from live sniper and automatic fire, shrapnel from unknown sources and the inhalation of tear gas for the ‘crime’ of approaching border fences and, in some cases, of possession of rocks, slingshots and bottles of petrol attached to kites.

It’s easy to succumb to panic in a world that looks increasingly out of control – and then to slip into complacency when our immediate fears are not realised or the killing fields slip down the news agendas. But in order to understand the real dangers posed by the present system and its wars, it’s necessary to step back, to consider where we are in the unfolding of events on a historical and world-wide scale.

In the Junius Pamphlet, written from prison in 1915, Rosa Luxemburg wrote that the world war signified that capitalist society was already sinking into barbarism. “The triumph of imperialism leads to the destruction of culture, sporadically during a modern war, and forever, if the period of world wars that has just begun is allowed to take its damnable course to the last ultimate consequence”.

Luxemburg’s historical prediction was taken up by the Communist International formed in 1919: if the working class did not overthrow a capitalist system which had now entered its epoch of decay, the “Great War” would be followed by even greater, i.e. more destructive and barbaric wars, endangering the very survival of civilisation. And indeed this proved to be true: the defeat of the world revolutionary wave which broke out in reaction to the First World War opened the door to a second and even more nightmarish conflict. And at the end of six years of butchery, in which civilian populations were the first target, the unleashing of the atomic bomb by the USA against Japan gave material form to the danger that future wars would lead to the extermination of humanity.

For the next four decades, we lived under the menacing shadow of a third world war between the nuclear-armed blocs that dominated the planet. But although this threat came close to being carried out – as over the Cuba crisis in 1962 for example – the very existence of the US and Russian blocs imposed a kind of discipline over the natural tendency of capitalism to operate as a war of each against all. This was one element that prevented local conflicts – which were usually proxy battles between the blocs – from spiralling out of control. Another element was the fact that, following the world-wide revival of class struggle after 1968, the bourgeoisie did not have the working class in its pocket and was not sure of being able to march it off to war.

In 1989-91, the Russian bloc collapsed faced with growing encirclement by the USA and inability of the model of state capitalism prevailing in the Russian bloc to adapt to the demands of the world economic crisis. The statesmen of the victorious US camp crowed that, with the “Soviet” enemy out of the way, we would enter a new era of prosperity and peace. For ourselves, as revolutionaries, we insisted that capitalism would remain no less imperialist, no less militarist, but that the drive to war inscribed in the system would simply take a more chaotic and unpredictable form[1]. And this too proved to be correct. And it is important to understand that this process, this plunge into military chaos, has worsened over the past three decades.

The rise of new challengers

In the first years of this new phase, the remaining superpower, aware that the demise of its Russian enemy would bring centrifugal tendencies in its own bloc, was still able to exert a certain discipline over its former allies. In the first Gulf War, for example, not only did its former subordinates (Britain, Germany, France, Japan, etc) join or support the US-led coalition against Saddam, it even had the backing of Gorbachev’s USSR and the regime in Syria. Very soon however, the cracks started to show: the war in ex-Yugoslavia saw Britain, Germany and France taking up positions that often directly opposed the interests of the US, and a decade later, France, Germany and Russia openly opposed the US invasion of Iraq.

The “independence” of the USA’s former western allies never reached the stage of constituting a new imperialist bloc in opposition to Washington. But over the last 20 or 30 years, we have seen the rise of a new power which poses a more direct challenge to the US: China, whose startling economic growth has been accompanied by a widening imperialist influence, not only in the Far East but across the Asian landmass towards the Middle East and into Africa. But China has shown the capacity to play the long game in pursuit of its imperialist ambitions – as shown in the patient construction of its “New Silk Road” to the west and its gradual build up of military bases in the South China Sea.

Even though at the moment the North-South Korean diplomatic initiatives and the announced US-North-Korean summit may leave the impression that “peace” and “disarmament” can be brokered, and that the threat of nuclear destruction can be thwarted by the “leaders coming to reason”, the imperialist tensions between the US and China will continue to dominate the rivalries in the region, and any future moves around Korea will be overshadowed by their antagonism.

Thus, the Chinese bourgeoisie has been engaged in a long-term and world-wide offensive, undermining not only the positions of the US but also of Russia and others in Central Asia and in the Far East; but at the same time, Russian interventions in Eastern Europe and in the Middle East have confronted the US with the dilemma of having to face up to two rivals on different levels and in different regions. Tensions between Russia and a number of western countries, above all the US and Britain, have increased in a very visible manner recently. Thus alongside the already unfolding rivalry between the US and its most serious global challenger China, the Russian counter-offensive has become an additional direct challenge to the authority of the US.

It is important to understand that Russia is indeed engaging in a counter-offensive, a response to the threat of strangulation by the US and its allies. The Putin regime, with its reliance on nationalist rhetoric and the military strength inherited from the “Soviet” era, was the product of a reaction not only against the asset-stripping economic policies of the west in the early years of the Russian Federation, but even more importantly against the continuation and even intensification of the encirclement of Russia begun during the Cold War. Russia was deprived of its former protective barrier to the west by the expansion of the EU and of NATO to the majority of eastern European states. In the 90s, with its brutal scorched-earth policy in Chechnya, it showed how it would react to any hint of independence inside the Federation itself. Since then it has extended this policy to Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014 onwards) – states that were not part of the Federation but which risked becoming foci of western influence on its southern borders. In both cases, Moscow has used local separatist forces, as well as its own thinly-disguised military forces, to counter pro-western regimes.

These actions already sharpened tensions between Russia and the US, which responded by imposing economic sanctions on Russia, more or less supported by other western states despite their differences with the USA over Russian policy, generally based on their particular economic interests (this was especially true of Germany). But Russia’s subsequent intervention in Syria took these conflicts onto a new level.

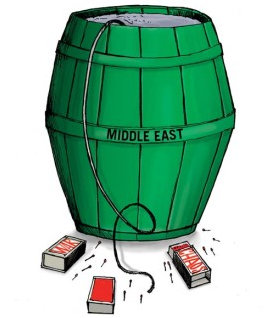

The Middle East maelstrom

In fact, Russia has always backed the Assad regime in Syria with arms and advisers. Syria has long been its last outpost in the Middle East following the decline of the USSR’s influence in Libya, Egypt and elsewhere. The Syrian port of Tartus is absolutely vital to its strategic interests: it is its main outlet to the Mediterranean, and Russian imperialism has always insisted on maintaining its fleet there. But faced with the threat of the defeat of the Assad regime by rebel forces, and by the advance of ISIS forces towards Tartus, Russia took the major step of openly committing troops and warplanes in the service of the Assad regime, showing no hesitation in taking part in the daily devastation of rebel-held cities and neighbourhoods, which has added significantly to the civilian death toll.

But America also has its forces in Syria, ostensibly in response to the rise of ISIS. And the US has made no secret of backing the anti-Assad rebels – including the jihadist wing which served the expansion of ISIS. Thus the potential for a direct confrontation between Russian and US forces has been there for some time. The two US military responses to the regime’s probable use of chemical weapons have a more or less symbolic character, not least because the use of “conventional” weapons by the regime has killed far more civilians than the use of chlorine or other agents. There is strong evidence that the US military reined in Trump and made sure that great care would be taken to hit only regime facilities and not Russian troops[2]. But this doesn’t mean that either the US or Russian governments can avoid more direct clashes between the two powers in the future – the forces working in favour of destabilisation and disorder are simply too deeply rooted, and they are revealing themselves with increasing virulence.

During both world wars, the Middle East was an important but still secondary theatre of conflict; its strategic importance has grown with the development of its immense oil reserves in the period after World War II. Between 1948 and 1973, the main arena for military confrontation was the succession of wars between Israel and the surrounding Arab states, but these wars tended to be short-lived and their outcomes largely benefited the US bloc. This was one expression of the “discipline” imposed on second and third rate powers by the bloc system. But even during this period there were signs of a more centrifugal tendency – most notably the long “civil war” in the Lebanon and the “Islamic revolution” which undermined the USA’s domination of Iran, precipitating the Iran-Iraq war (where the west mainly backed Saddam as a counter-weight to Iran).

The definitive end of the bloc system has profoundly accelerated these centrifugal forces, and the Syrian war has brought them to a head. Thus within or around Syria we can see a number of contradictory battles taking place:

- Between Iran and Saudi Arabia: often cloaked under the ideology of the Shia-Sunni split, Iranian backed Hezbollah militias from Lebanon have played a key role in shoring up the Assad regime, notably against jihadi militias supported by Saudi and Qatar (who have their own separate conflict). Iran has been the main beneficiary of the US invasion of Iraq, which has led to the virtual disintegration of the country and the imposition of a pro-Iranian government in Baghdad. Its imperialist ambitions have further been playing out in the war in Yemen, scene of a brutal proxy war between Iran and Saudi (the latter helped no end by British arms)[3];

- Between Israel and Iran. The recent Israeli air strikes against Iranian targets in Syria are in direct continuity with a series of raids aimed at degrading the forces of Hezbollah in that country. It seems that Israel continues to inform Russia in advance about these raids, and generally the latter turns a blind eye to them, although the Putin regime has now begun to criticise them more openly. But there is no guarantee that the conflict between Israel and Iran will not go beyond these controlled responses. Trump’s “diplomatic vandalism”[4] with regard to the Iranian nuclear deal is fuelling both the Netanyahu government’s aggressively anti-Iran posture and Iran’s hostility to the “Zionist regime”, which, it should not be forgotten, has long maintained its own nuclear weapons in defiance of international agreements.

- Between Turkey and the Kurds who have set up enclaves in northern Syria. Turkey covertly supported ISIS in the fight for Rojava, but has intervened directly against the Afrin enclave. The Kurdish forces, however, as the most reliable barrier to the spread of ISIS, have up to now been backed by the US, even if the latter might hesitate to use them to directly counter the military advances made Turkish imperialism. In addition Turkish ambitions to once again play a leading role in the region and beyond have not only driven it into conflict with NATO and EU countries, but have reinforced Russian efforts to drive a wedge between NATO and Turkey, and to pull Turkey closer to Russia, despite Turkey’s own long-standing rivalry with the Assad regime.

- This tableau of chaos is further enriched by the rise of numerous armed gangs which may form alliances with particular states but which are not necessarily subordinate to them. ISIS is the most obvious expression of this new tendency towards brigandage and warlordism, but by no means the only one.

The impact of political instability

We have seen how Trump’s impetuous declarations have added to the general unpredictability of the situation in the Middle East. They are symptomatic of deep divisions within the American bourgeoisie. The president is currently being investigated by the security apparatus for evidence of Russian involvement (via its well-developed cyber war techniques, financial irregularities, blackmail etc) in the Trump election campaign; and up till recently Trump made little secret of his admiration for Putin, possibly reflecting an option for allying with Russia as a counter-weight to the rise of China. But the antipathy towards Russia within the American bourgeoisie goes very deep and, whatever his personal motives (such as revenge or the desire to prove that he is no Russian stooge), Trump has also been obliged to talk tough and then walk the talk against the Russians. This instability at the very heart of the world’s leading power is not a simple product of the unstable individual Trump; rather, Trump’s accession to power is evidence of the rise of populism and the growing loss of control by the bourgeoisie over its own political apparatus - the directly political expressions of social decomposition. And such tendencies in the political machinery can only increase the development of instability on the imperialist level, where it is most dangerous.

In such a volatile context, it is impossible to rule out the danger of sudden acts of irrationality and self-destruction. The tendency towards a kind of suicidal insanity, which is certainly real, has not yet fully seized hold of the leading factions of the ruling class, who still understand that the unleashing of their nuclear arsenals runs the risk of destroying the capitalist system itself. And yet it would be foolish to rely on the good sense of the imperialist gangs that currently rule the planet – even now they are researching into ways in which nuclear weapons could be used to win a war.

As Luxemburg insisted in 1915, the only alternative to the destruction of culture by imperialism is “the victory of socialism, that is, the conscious struggle of the international proletariat against imperialism. Against its methods, against war. That is the dilemma of world history, its inevitable choice, whose scales are trembling in the balance awaiting the decision of the proletariat”.

The present phase of capitalist decomposition, of spiralling imperialist chaos, is the price paid by humanity for the inability of the working class to realise the promise of 1968 and the ensuing wave of international class struggle: a conscious struggle for the socialist transformation of the world. Today the working class finds itself faced with the onward march of barbarism, taking the form of a multitude of imperialist conflicts, of social disintegration, and ecological devastation; and - in contrast to 1917-18, when the workers’ revolt put an end to the war – these forms of barbarism are much harder to oppose. They are certainly at their strongest in areas where the working class has little social weight – Syria being the most obvious example; but even in countries like Turkey, where the question of war faces a working class with a long tradition of struggle, there are few signs of direct resistance to the war effort. As for the working class in the central countries of capital, its struggles against what is now a more or less permanent economic crisis are currently at a very low ebb, and have no direct impact on the wars that, although geographically peripheral to Europe, are having a growing - and mainly negative – impact on social life, through the rise of terrorism and the cynical manipulation of the refugee question[5].

But the class war is far from over. Here and there it shows signs of life: in the demonstrations and strikes in Iran, which showed a definite reaction against the state’s militarist adventures; in the struggles in the education sector in the UK and the USA; in the growing discontent with government’s austerity measures in France and Spain. This remains well below the level needed to respond to the decomposition of an entire social order, but the defensive struggle of the working class against the effects of the economic crisis remains the indispensable basis for a deeper questioning of the capitalist system.

Amos, 16.5.18

[1] See in particular our orientation text ‘Militarism and decomposition’ in International Review 64, 1991, https://en.internationalism.org/node/3336

[2] “US defence secretary James Mattis managed to restrain the president over the extent of airstrikes on Syria. (...)It was Jim Mattis who saved the day. The US defence secretary, Pentagon chief and retired Marine general has a reputation for toughness. His former nickname was ‘Mad Dog’. When push came to shove over Syria last week, it was Mattis – not the state department or Congress – who stood up to a Donald Trump baying for blood. Mattis told Trump, in effect, that the third world war was not going to start on his watch. Speaking as the airstrikes got under way early on Saturday, Mattis sounded more presidential than the president. The Assad regime, he said, had ‘again defied the norms of civilised people … by using chemical weapons to murder women, children and other innocents. We and our allies find these atrocities inexcusable.’ Unlike Trump, who used a televised address to castigate Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin, in highly personal and emotive terms, Mattis kept his eye on the ball. The US was attacking Syria’s chemical weapons capabilities, he said.that this, nothing more or less, was what the air strikes were about. Mattis also had a more reassuring message for Moscow. ‘I want to emphasise that these strikes are directed at the Syrian regime … We have gone to great lengths to avoid civilian and foreign casualties’ In other words, Russian troops and assets on the ground were not a target. Plus the strikes were a “one-off”, he added. No more would follow”. (Simon Tisdall, The Guardian 15 Apr 2018)

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/09/europe-trump-wreck-iran-nuclear-deal-cancel-visit-sanctions

[5] For an assessment of the general state of the class struggle, see ‘22nd ICC Congress, resolution on the international class struggle’, in IR 159, https://en.internationalism.org/international-review/201711/14435/22nd-i...

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace