ICConline - 2013

- 2963 reads

January 2013

- 1684 reads

20th Congress of Révolution Internationale: Building on the acquisitions of the ICC

- 1873 reads

The ICC Section in France held its 20th Congress recently. Like all RI congresses, this plenary gathering of our territorial section had, of course, an international dimension. This is why delegations were present from different sections of the ICC, composed of comrades from several countries and continents, who were able to actively participate in the discussions. Also present at this Congress were a number of contacts and supporters of the ICC, invited to the various discussions (except those dealing with our internal functioning).

As with the plenary gatherings of our other territorial sections, an important part of the work of the RI Congress was devoted to the discussion of the activities of the ICC. Moreover, in the way in which in recent years our organisation has devoted its congress debates to analysing the evolution of the economic crisis and the class struggle in particular, this Congress of RI gave itself the task of conducting a specific discussion on the dynamics of the imperialist conflicts by placing them in a historical and theoretical framework.

The balance sheet of our analysis on the unfolding imperialist conflicts

The report and discussion on the imperialist conflicts gave itself the objective of making a balance sheet of the events that have unfurled since the collapse of the Eastern bloc in 1989 to see if it confirms the validity of the ICC's analyses.

After the collapse of the USSR, the ICC had asked the following question: with the demise of the Eastern bloc, would we now see the hegemony of one imperialist bloc and a decline in military conflicts? The ICC replied: No! Indeed, we have always rejected the thesis of ‘super-imperialism’, developed by Kautsky before the First World War, which was opposed by revolutionaries in the past (including Lenin). This thesis has been disproved by the facts themselves. "It was just as false when it was taken up and adapted by the Stalinists and Trotskyists claiming that the bloc controlled by the USSR was not imperialist. Today, the collapse of this bloc is not going to revive this kind of analysis: as a consequence of its collapse, the Western bloc is tumbling too." (International Review n ° 61, January 1990).

The debates at the congress showed that events have fully confirmed the validity of marxism: the disappearance of the Russian imperialist bloc was not going to open up an ‘era of peace and prosperity’ for humanity as claimed by the western ‘democratic’ bourgeoisie. Since 1989, the militarist barbarism of capitalism continued to unfold in the Middle East, in Africa, Pakistan, and even in Europe with the war in the former Yugoslavia.

The congress also examined the other analysis that the ICC had developed in 1989: if the historical tendency for the formation of imperialist blocs (characteristic of the period of capitalist decadence) was still correct, only Germany could be a new bloc leader opposing the United States because of its economic power and its strategic geographical location. But, as we said at the time, this hypothetical perspective could not be realised in an immediate sense, particularly because Germany has little military strength; it does not have nuclear weapons, needed to become the leader of a new imperialist bloc. Twenty-three years after the collapse of the USSR, the RI Congress noted that Germany has not emerged as a rival to challenge American power on the world stage (therefore this ICC hypothesis has not been verified). By contrast, it is China that is emerging as the main rival of the first world power. The congress has clearly stated that this is a new element that the ICC had not expected (and could not have foreseen) when the USSR collapsed. Nevertheless, although China increasingly shows its commitment to be a world power, it does not have the military might to oppose the imperialist aims of the United States. Its aggression towards the United States is expressed mainly on the economic and strategic level (as confirmed by the global competitiveness of its goods, its extensive international relations and its presence on the African continent).

The debates at the congress recalled that, although the military conditions for a Third World War have disappeared with the collapse of the USSR (which led to the collapse of the former American bloc created after the Second World War), armed conflicts haven't at all gone away and the death tally continues to rise globally. The only difference lies in the fact that these conflicts are no longer contained by a bloc discipline, as was the case during the period of the Cold War. Our analysis of the decomposition of capitalism, the final phase in the decadence of this mode of production, has also enabled the ICC to say that the tendency towards 'every man for himself' and the instability of the military alliances would form an obstacle to the formation of new imperialist blocs. If the militarist barbarism of capitalism has continued over two decades in the form of 'every man for himself' (including the emergence of terrorism as a weapon of war between states), it is precisely because no world power has been able in this time to play the role of world policeman and impose a new 'world order' as claimed at the time by U.S. President George Bush. The congress demonstrated that the predictions of the ICC and of marxism are totally confirmed: peace is impossible under capitalism. This is what we have seen since 1989 with the two Gulf wars, the massacres in the Middle East and in Africa, the conflict between India and Pakistan and for the first time since 1945, the outbreak of a European war, in the former Yugoslavia.

If the 20th RI Congress has found it necessary to remind us of the framework of analysis of the ICC, it is also to convey to young militants the method of marxism. Only this historical method and the scientific verification of the facts can enable us to avoid the pitfalls of empiricism based on a purely photographic picture of events from day to day.

The analysis of the situation in France

The second discussion that animated the debates at the Congress was focused on the situation in France and led to the adoption of a resolution published in RI no.438. The 20th RI Congress was held shortly after the recent presidential elections in which François Hollande was the victor. The debates in the congress affirmed that this change of government would further increase the difficulty of the French bourgeoisie to manage the national capital. There is now a "socialist" government that will have to deal with the inevitable worsening of the global economic crisis. This "left-wing" government (that has moreover inherited the blunders of "Sarkozyism") can only continue to intensify the attacks against working class living conditions. The only "change" can come in the language and types of mystification used to implement the austerity policies of the new government, as the Resolution adopted by the congress clearly spelled out [1].

The debate on the report on the situation in France presented to the Congress also dealt with the dynamics of the class struggle. It showed that, despite the depth of the economic crisis and the significant deterioration of living conditions of the working class in France, as in all countries, the proletariat has not, as yet, launched itself into large scale struggles since the movement against pension reform in the autumn of 2011: "If, as in other countries, expressions of combativity are characterised by a dispersion of struggles, the brutal attacks on working class living standards that results from the economic crisis, will force workers into developing their struggles on a much broader scale. This is true for the working class of all countries but it is particularly true for France because the working class of this country has a long tradition of mobilising en masse. This tradition explains why, unlike what occurred in countries such as Spain and the United Kingdom, movements such as the Indignados or Occupy Wall Street have not taken place in France. The reason lies in the fact that, unlike the other countries, the militancy of the working class of this country had already produced massive mobilisations such as the struggle against the CPE in 2006 and more recently the one against pension reform. Thus, there was less of a feel for the need of such movements to express the discontent inside the working class, which tells us that the lack of movements similar to that of the Indignados in France, does not mean that the working class here is lagging behind, especially when compared to other developed countries. Despite the big handicaps that hinder the working class (loss of class identity and lack of perspective), the speed with which living conditions will continue falling in France, as in other countries, is going to push the exploited to try and develop their combativity in the manner we've seen recently with the massive protests that took place in Portugal, Spain and Greece. Even if the ideological garb which the bourgeoisie uses to push through its attacks will delay and make the explosion of struggles more difficult, it will not be enough to prevent them." (Resolution on the situation in France, Point 7).

Developing the "culture of theory" in preparing the future

The plenary assembly of our section in France is also the time when it must draw a balance sheet of its activities from the previous RI congress and draw up perspectives for the next two years. And, of course, in a centralised international organisation like the ICC, the activities of its territorial sections can only be examined in the general framework of the activities of the whole organisation. This is why the congress gave an important place in the discussion to the ICC activities (which we will report on eventually in our press after holding our next international congress).

On the basis of the report submitted by the central organ of the section in France, the Congress drew an undeniably positive balance sheet of all the RI activities (including its intervention in the class struggle, and among the politicised minorities). It was on the basis of this review that the Congress also had to examine with the utmost clarity the weaknesses and challenges that the ICC section in France had come up against in the last two years, and how it might overcome them:

- the ‘routinism’ which had given rise to an underestimation of the need for theoretical deepening (especially on organisational questions);

- a difficulty in conveying to new militants the lessons of all the accumulated experience of the ICC in building the organisation and the party spirit (the fight to defend the Statutes of the ICC, against centrism and opportunism, against the circle spirit which reduces organisational relations to links based on personal affinity).

The debates at the Congress, which took place mainly around the adoption of the Activities Resolution, gave an orientation for our section in France of improving its internal functioning to meet the challenges that lie ahead: the need to transmit to the new generation of militants the method of marxism and the acquisitions of the ICC at the political and theoretical level, as well as the organisational level. To ensure this transmission and the ‘organic’ link between generations, the Congress noted that the older generation is engaged in a permanent fight against the tendency to lose sight of its acquisitions (which we have already noted on several occasions previously). As the ICC has existed longer than any other international organisation in the history of the workers' movement, it is ‘normal’ that the acquisitions of its past experience can tend to be forgotten over time.

The Congress of the section in France adopted the perspective of having a better balance in its activity in order to allow all its militants to find time to read and reflect so that the entire organisation can collectively develop its theoretical debates (especially on new questions that can't be entrusted to ‘specialists’).

In the framework of rationalising our activity, the Congress also had a discussion on our territorial printed press and the Internet, and the role of these two media. Given that today our website is our main tool of intervention (our articles are put on line as soon as they are written), the Congress began a reflection about the reduction in the frequency/ regularity of the publication of the RI paper (whose sales only increase with interventions at demonstrations, while the numbers reading our articles on our website is not dependent on the vagaries of the class struggle).

Faced with the danger of immediatism, the Congress recalled that intervention in the ongoing struggles of the working class, as indispensable as it is, is not however our main activity. Like all revolutionary organisations of the past, the primary responsibility of the ICC is to prepare the conditions for the proletarian revolution, and in particular the conditions for the formation of the future world party. This is why our long-term work of building the organisation, must remain at the centre of our activity.

The Activities Resolution, adopted by Congress after a long debate (where all the militants were involved) said: "The activity of revolutionaries is not limited to the intervention in the immediate struggles of the working class and its minorities, but lies first of all in the ‘political and theoretical clarification of the goals and methods of the proletarian struggle, of its historic and its immediate conditions’. (see the point about our activity in our basic positions published on the back of our publications) (...) Our work of theoretical elaboration is by no means complete, far from it, and will never be completed. This theoretical clarification is still ahead of us and must remain our priority in the fight to build the organisation and in continuing to fulfill our responsibility as a vanguard of the proletariat. " (Point 14).

"...The struggle for communism doesn't just have an economic and political dimension, but also a theoretical dimension ("intellectual" and moral). It is by developing 'the culture of theory'; that is to say, the ability to permanently situate all aspects of the organisation's activities in a historical and /or theoretical framework, that we can develop and deepen the culture of debate internally, and better assimilate the dialectical method of marxism."

Clearly with this approach the ICC section in France has provided itself with the perspective of strengthening its organisational tissue and improving its functioning by developing a theoretical debate on the roots of its present and past difficulties.

"This work of theoretical reflection cannot ignore the contribution of science (and notably the social sciences, such as psychology and anthropology), on the history of the human species and the development of civilisation. In particular the discussion on 'marxism and science' was of utmost importance for us and we should continue with it and build on it in our reflections and in our organisational life." (Activities Resolution, Point 6).

The invitation of a scientist to the 20th Congress of RI

As our readers know, in the year of the celebration of the ‘Darwin anniversary’, the ICC revived a tradition of the past workers' movement: an interest in scientific research and the new scientific discoveries, including those that provide marxism with a better understand of human nature. For it to build communism in the future, the proletariat must go to the "root of things" and, as Marx said, "the root of things for man is man himself." This is why we have conducted a discussion on "marxism and science" and have invited scientists to the last two ICC congresses.

Our interest in the sciences continued in the 20th RI Congress. A small part of this work was devoted to a debate with a scientist around a topic chosen by us: "Confidence and solidarity in the evolution of humanity: what distinguishes our species from the great apes?".

Camilla Power, teacher of anthropology at the University of East London (and collaborator with Chris Knight), had agreed to come to the RI congress and lead a discussion on this topic. In her very interesting and well-illustrated presentation, she explained the development of solidarity and confidence in the human species by recalling the Darwinian theory of evolution.

Everyone at the congress, including our contacts and the invited sympathisers, appreciated the materialist approach and the scientific rigour of the presentation, as well as the quality of the debate. For her part, Camilla Power warmly thanked the congress with these words before her departure:

"I just want to say thank you; it was very exciting for me to come to your congress. I learned a lot from the questions and answers from the different contributors. I was very impressed with the reading you have done, and what you have learned. I have always felt very committed to marxism and to Darwinism. I'm an anthropologist. We must combine an understanding of the natural history and social history. And anthropology is central to this. Marx and Engels spent a lot of time towards the end of their lives doing research in anthropology. It happened very late in life, but it shows that they recognised how important it is. It's very exciting to meet people who want to think scientifically about what it means ‘to be human’. This is a very important issue for everyone, for the international working class. For us, it is about rediscovering the nature of our humanity. We must not be afraid of science, because it is science that will give us revolutionary answers. Thank you very much, comrades."

We can now make a very positive assessment of the invitation of a scientist to our congress. It is an experience that our organisation will try and repeat as much as possible in future congresses.

The road leading to the proletarian revolution is a long, difficult and fraught with pitfalls (as Marx underlined in The 18th Brumaire [2]).

The work of the ICC is just as long and difficult as the struggle of the proletariat for its emancipation. It is all the more difficult as our forces remain extremely limited today. But the difficulties facing the communist organisations in carrying out their work has never been a factor of discouragement, as we see in this quote from Marx cited at the end of the Activities Resolution adopted by the 20th Congress of RI: "I've always found it in all those truly steeled characters, that once they have engaged in revolutionary work, they will continually draw new strength from defeat and become even more committed as the tide of history sweeps them along"(Marx, Letter to Philip J. Becker).

RI 22/12/12

Life of the ICC:

- Congress Reports [3]

Rubric:

Attacks on Benefits - Once again, workers pay for the crisis!

- 1772 reads

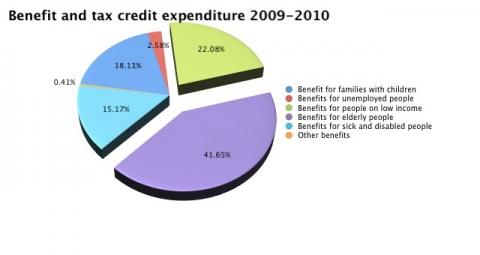

At the start of 2013 the UK’s Coalition government voted in the latest tranche of austerity measures aimed at reducing the budget deficit. The Spending Review put forward by George Osborne factored in the planned attacks on welfare benefits and pensions. These attacks have been phased in by the British bourgeoisie over a number of years and didn’t start with the Lib-Cons coming to power. The attacks are plainly focussed on the working class.

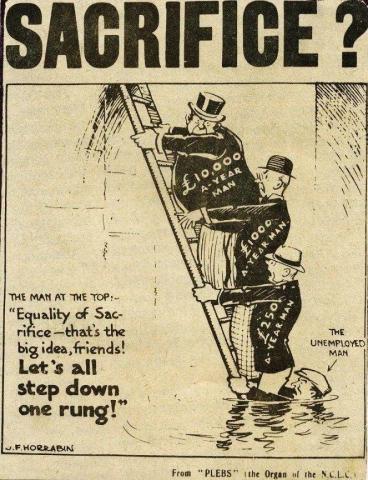

To start, the government has placed a cap of 1% increase per annum for a period of three years on all welfare benefits. This has jettisoned the link of benefits to inflation that had previously been in place. When we consider that the present level for JSA is £71 (if you are 25 or over, £56.25 if under), an already impoverished situation is bound to get worse. The Department of Works and Pensions has insisted that this is not a cut, but is committed to establishing a further £10 billion ‘saving’ in the welfare bill in the coming period.

Iain Duncan Smith, the Secretary of State for Works and Pensions, has promised to introduce a ‘Universal Benefit’ which will impose a £500 ceiling on all benefits for every household. This is currently being trialled in different boroughs in the country because the DWP does not have in place the infra-structure to implement it immediately. However, the cuts will still take place. These cuts will affect JSA, working tax credits, and pension credits. The Disability Living Allowance will be replaced by a ’Personal Independence Payment’.

The cuts to child credit payment will affect 2.5 million single women workers and a further million whose partners are in work. This in effect will be throwing millions of children into poverty. The Child Poverty Action Group has said that these changes will cut 4% from benefits over the next three years. The overall plan is to subsume all payments into the one ‘Universal Benefit’ payment. The government will thus cut its welfare bill. All the guff about lazy ‘shirkers’ versus hard-working ‘strivers’ is just so much camouflage to hide the attacks. According to another report, this time by the Children’s Society, “up to 40,000 soldiers, 300,000 nurses and 150,000 primary and nursery school teachers will lose cash, in some cases many hundreds of pounds” (Guardian 5/1/13) So much for targeting ‘shirkers’!

Housing benefits: cut

The government has placed a cap of £500 per household per week on the rent of a family home. In places like London this is impossible for many to find. According to the government’s own figures on risk assessment, this will affect some 2.8 million people. 400,000 of the poorest people will be included. 300,000 households stand to lose more than £300 per week.

The government in its ‘war on welfare dependency’ will hit the young hardest. The government intends to refuse housing benefit to the under 25’s. This is to effectively throw thousands of young people onto the streets.

Council tax benefits: cuts

The government is cutting its subsidies to local councils by 10% while leaving local authorities to implement the cuts in Council Tax payments. This will mean an average £10 per week that social tenants will have to find to supplement their rents. Those occupying dwellings which have a spare bedroom will have to find a minimum of £10 per week under the so-called ‘Bedroom Tax’ since they now fall into the “over occupancy” category. This will again hit young people the hardest. The homeless charity Shelter say that only 1 in 5 of rental homes are affordable to single people on benefits.

The Labour Party’s alternative workfare scheme

The Labour Party, far from being opposed to the cuts, have declared that they agree with the ‘basic principle’ that work for the jobless should be encouraged and should be part of a package for welfare benefits. In response to the government attacks Liam Byrne (shadow employment secretary) has come up with his own ‘workfare’ scheme. This scheme would see every claimant under the age of 25 who has been unemployed for more than two years forced into compulsory jobs. These workers would be paid the minimum wage only. Anyone who refused such Mickey Mouse ‘jobs’ would, under the Labour Party scheme, lose 13 weeks of benefit for the first time and 26 weeks of benefits for the second time. This would not only be a way of reducing the welfare benefit costs but would also force unemployed workers into the hands of unscrupulous bosses. It is reminiscent of the ‘Dole Schools’ of the 1930s where, to claim the dole, you had to attend ‘schools’ to perform menial work or lose what little benefit you could receive.

This Labour party scheme will only mean jobs for six months, after which workers will be back on the dole - and unemployment will still remain at the same massive levels, since most workers won’t qualify for the scheme anyway.

General attack, general response

The attacks are only just beginning. The benefit cuts are part of a wider push to make the working class pick up the bill for their crisis. Governments all around the world, particularly in the centres of the Eurozone like Greece and Spain, are doing the same.

If the working class is to mount any resistance to this offensive, it must reject out of hand all attempts to make it feel responsible for the crisis of capitalism, and all the nauseating campaigns about shirkers and strivers, which are aimed at dividing the working class. Unemployment and poverty are the product of capitalism in crisis and the working class can only defend itself by developing its unity in the struggle against this system.

Melmoth 12/1/13

Rubric:

Capitalism produces the housing crisis

- 3813 reads

In September 2012 legislation came into force that made squatting in the UK a criminal offence. At the end of the month the first person was convicted under the new legislation and sentenced to 12 weeks in prison. He had come from Plymouth to London looking for work and had occupied a flat owned by a housing association.

Prior to this a number of Tory MPs and newspapers made much of cases where homes that were lived in had been squatted and used this to justify the new law, despite knowing that there were a number of laws already in place aimed at preventing squatting. This suggests that the new law is actually aimed at keeping squatters out of unoccupied houses, offices and other buildings, which are those usually squatted. It is also part of the wider campaign to divide and control the working class. This was given a new boost at the start of 2013 with the spat over ‘scroungers’ versus ‘strivers’ that preceded the vote to limit increases in most benefits to 1% a year.

No official figures on the number of people squatting have been collected since the mid 1980s, but a recent article in the Guardian reported that there are between twenty and fifty thousand people squatting, mostly living in long-term abandoned properties.[1] This is part of the larger picture of increasing numbers struggling to keep a roof over their heads. For example, the figures gathered about homelessness show increases in the last few years: in England 110,000 families applied to their local authority as homeless in 2011/12, an increase of 22% over the preceding year. 46% of these were accepted by the local authority as homeless, an increase of 26% over the preceding year. The figures for Wales and Scotland also show increases in both the numbers applying and being accepted.

The charity Crisis, from whose website the figures above are taken, underlines that these official figures are likely to be very inaccurate since the majority of those who are homeless are hidden because they do not show up in places, such as official homeless shelters, that the government uses to gather its data. Another indicator that housing is becoming an increasing problem is provided by the data about the numbers sleeping rough. In 2011 official figures show that over two thousand people slept rough in England on any one night in 2011, an increase of 23% over 2010. However, once again, the real figure is probably far higher as non-government agencies report that over five and a half thousand people slept rough in 2011/12 just in London, an increase of 43% over the previous year.

Globally, it is estimated that at least 10% of the world’s population is squatting. Many of the slums that surround cities such as Mumbai, Nairobi, Istanbul and Rio de Janeiro are largely comprised of squatters.[2] The types of accommodation, the services, or lack of them, available to inhabitants, the type of work undertaken and the composition of the population all vary, but collectively they show that, for all the goods produced and all the money swirling around the world, capitalism remains unable to adequately meet one of the most basic of human needs. The purpose of this article is to try and examine the reasons for this.

The starting point is the recognition that the form the housing question takes under capitalism is determined by the economic, social and political parameters of bourgeois society. In this system, the interests of the working class, and of other exploited classes such as the peasantry, are always subordinated to those of bourgeoisie. At the economic level there are two main dynamics. On the one hand, housing for the working class is a cost of production and thus subject to the same drive to reduce the costs as all other elements linked to the reproduction of this class. On the other, housing can also be a source of profits for part of the bourgeoisie, whether provided for the working class or any other part of society. At the social and political level, housing raises issues about health and social stability that concern the ruling class, while it can also offer opportunities for both physical and ideological control of the working class and other exploited classes. This was true in the early days of capitalism and remains true today.

Housing and early capitalism

The situation in Britain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was a consequence of the full unfolding of the capitalist system that had been developing for several centuries previously. The industrial revolution that was a consequence of these early developments led to a transformation in all areas of life within the capitalist world, in the economy, in politics and in social life. The development of large factories led to the rapid growth of cities, such as London, Manchester and Liverpool, and drew in millions of dispossessed peasants, transforming them into proletarians. Advances in productivity and the cyclical crises that typified early capitalism periodically ejected hundreds of thousands of workers from employment while the expansion of production and its extension into new fields, driven on by the same crises, drew them back in. For the bourgeoisie this meant there was a readily available workforce: the reserve army of those ejected from work or newly driven from the land, that tended to help keep the cost of all labour down. For the working class the result was a life of exploitation, poverty and uncertainty.

The Condition of the Working Class in England [6] written by Engels after he moved to Manchester in 1842 and published in German in 1845, revealed the true face of the industrial revolution. A central theme of the work is an examination of the living conditions of the working class. Drawing on various official reports as well as his own observations he described the accommodation endured by workers in cities such as London, Liverpool, Birmingham, and Leeds: “These slums are pretty equally arranged in all the great towns of England, the worst houses in the worst quarters of the towns, usually one or two-storied cottages in long rows, perhaps with cellars used as dwellings, almost always irregularly built…The streets are generally unpaved, rough, dirty, filled with vegetable and animal refuse, without sewers or gutters, but supplied with foul, stagnant pools instead. Moreover, ventilation is impeded by the bad, confused method of building of the whole quarter, and since many human beings live here crowded into a small space, the atmosphere that prevails in these working-men’s quarters may readily be imagined.”[3]

He notes the gradations of misery within this overall picture. In St Giles in London, which was near Oxford Street, Regent Street and Trafalgar Square with their “broad, splendid avenues”, he distinguishes between the dwellings located in the streets and those in the courts and alleys that ran between them. While the appearance of the former “is such that no human could possibly wish to live in them” the “filth and tottering ruin” of the latter “surpass all description”: “Scarcely a whole window-pane can be found, the walls are crumbling, door-posts and window-frames loose and broken, doors of old boards nailed together, or altogether wanting in this thieves quarter…Heaps of garbage and ashes lie in all directions, and the foul liquids emptied before the doors gather in stinking pools. Here live the poorest of the poor, the worst paid workers with thieves and the victims of prostitution, indiscriminately huddled together, the majority Irish, or of Irish extraction, and those who have not sunk into the whirlpool of moral ruin which surrounds them, sinking daily deeper, losing daily more and more of their power to resist the demoralising influence of want, filth, and evil surroundings.”[4] In the new factory towns industrialists and speculators threw up houses that were poorly built, overcrowded and lacking in ventilation. Within a few years most had become slums, albeit profitable ones. From these and many other descriptions of the environment Engels goes on to consider the consequences on the physical and mental health of the inhabitants. He shows the link between mortality, ill health and poverty, examines the poor quality of the air breathed by the working class, the lack of education of their children, and the arbitrary brutality of the conditions and regulations of employment.

The pattern set by Britain was quickly followed by other countries such as France, Germany and America as they industrialised. Everywhere that capitalism developed the working class was housed in slums and in most of the great cities the working class areas were places of poverty, filth and disease from which the new bourgeoisie drew the wealth that allowed them to live comfortably and moralise according to their various tastes about the immorality and fecklessness of the working class.

Bourgeois solutions to the housing crisis

In The Housing Question [7], published 27 years after the Condition of the Working Class in England, Engels acknowledges that some of the worst slums he described had ceased to exist. The principal reason for this was the realisation by the bourgeoisie that the death and disease that reigned in these places not only weakened the working class, and thus the source of their profits, but also threatened their own health: “Cholera, typhus, typhoid fever, small-pox and other ravaging diseases spread their germs in the pestilential air and the poisoned water of these working class districts… Capitalist rule cannot allow itself the pleasure of generating epidemic diseases with impunity; the consequences fall back on it and the angel of death rages in the ranks of the capitalists as ruthlessly as in the ranks of the workers.”[5] In Britain this resulted in official inquiries, which Engels notes were distinguished by their accuracy, completeness and impartiality compared to Germany, and which paved the way for legislation that began to address the worst excesses.

This was the era that saw the building of sewerage and water systems in towns and cities in Britain. If the impulse for these reforms came specifically from the self-interest of the bourgeoisie and more indirectly from the pressure of the working class and the need to manage the growing complexity of society, the possibility of realising them was due to the immense wealth being produced by capitalism. Engels notes that the interests of the bourgeoisie in this matter are not only linked to issues of public health but also to the need to build new business premises in central locations, to improve transport by bringing the railways into the centre of cities and building new roads, and also by the need to make it easier to control the working class. This last had been a particular concern in France after the Paris Commune and resulted in the building of the broad avenues that still characterise much of this city.

However, Engels goes on to argue that such reforms do not eliminate the housing question: “In reality the bourgeoisie has only one method of settling the housing questions after its fashion – that is to say, of settling it in such a way that the solution poses the question anew.”[6] He gives the example of a part of Manchester called Little Ireland that he described in The Condition of the Working Class in England. This area, which was “the disgrace of Manchester”, “long ago disappeared and on its site there now stands a railway station”; but subsequently it was revealed that Little Ireland “had simply been shifted from the South side of Oxford Road to the north side.”[7] He concludes: “The same economic necessity which produced them in the first place produces them in the next place also. As long as the capitalist mode of production continues to exist it is folly to hope for an isolated settlement of the housing question or of any other social question affecting the lot of the workers.”[8]

Subsequent developments in Britain seem, ultimately, to refute this since the slums of the 19th and early 20th century are gone. The First World War left a shortage of 610,00 houses with many pre-war slums untouched. In its aftermath local authorities were given powers to clear slums and to build housing for rent. Between 1931 and 1939 over 700,000 homes were built, re-housing four fifths of those living in slums.[9] Many of the new houses were built in large estates on the outskirts of major cities including Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester and London. Some local authorities experimented by building blocks of flats. However, these efforts were dwarfed by the two and half million homes built privately and sold to the middle class and better off parts of the working class. Nonetheless, this did not mark the end of slums and severe overcrowding remained common in many working class areas. The Second World War saw a regression as house building all but stopped and inner city areas were exposed to bombing. The post war period witnessed the most concerted house building programme by the state in British history, which reached its peak under the Tory government of the late 1950s when over 300,000 council homes were built annually. The building of large tower blocks was a more prominent feature this time. Support was also given to private building and by 1975 52.8% of homes were privately owned, compared with 29.5% in 1951 (private rented properties fell from 44.6% to 16% during the same period).[10]

However, these developments were the product of their time and reflect the prevailing economic situation. In Britain and the other major capitalist powers, the post war period allowed some significant changes in housing. The post-war boom that was based on the very significant improvements in productivity that followed the destruction of the war gave the state the means to increase spending in a range of areas, including housing. As already noted, some important working class areas in cities that had been centres of production had been destroyed or damaged by bombing. The industries that developed after the war, such as car making, led to the building of new factories, often outside the old concentrations. This required the building of accommodation for workers. There was also a political motive in meeting social needs in order to reduce the risk of unrest following the war. In this the state drew on the failure of the policy of ‘Homes fit for heroes’ proclaimed after World War I, a failure that had helped to discredit the post-war government of Lloyd George.

However, the post war boom did not reach many parts of the world. These included some countries in the west, such as Ireland where severe poverty and slums remained until the economic boom that developed there in the 1980s. Above all, it encompassed what has been called the ‘Third World’, which essentially comprises those continents and countries that were subject to imperialist domination by the major capitalist countries. In short, most of the world. Looked at from this perspective it becomes evident that Engels’ argument is not just confirmed but confirmed on a scale he could not have imagined.

Housing in late capitalism

The present global situation is shaped by the structural crisis of capitalism that lies behind both the open recessions and the booms of the last 30 to 40 years, including the astonishing levels of growth seen in China, India and a number of other countries. This period has seen a reshaping of the whole world and its full analysis is far beyond the scope of this article. For many on the left this reshaping is a consequence of the triumph of neo-liberalism with its doctrines of reducing the state and supporting private enterprise. This is frequently presented as an ideologically based strategy and the crisis of 2007 as being of its making. While the critique of neo-liberalism and globalisation may describe aspects of the changes that have taken place in the global economy, it tends to miss the essential point that this transformation is the result of the response of capitalism to the economic crisis. It is the result of the unfolding of the immanent laws of capitalism rather than the outcome of ideology. It is this that links the situation in the old heartlands and the periphery, in the Third World and the first, in the countries experiencing economic growth and those not. The housing question everywhere has been posed anew by these developments.

Today, one billion people live in slums and the majority of the world’s population is now urban. Numbers continue to grow every day and the slums that surround cities of all sizes in these countries grow ever-larger. Most of these slums are in the third world and, to a lesser extent, parts of the old eastern bloc (what was once called the Second World). This is a new situation. In the book Planet of Slums, published in 2006, the author, Mike Davis, argues that “most of today’s megacities of the South share a common trajectory: a regime of relatively slow, even retarded growth, then abrupt acceleration to fast growth in the 1950s and 1960s, with rural immigrants increasingly sheltered in peripheral slums.” [11] The slow or retarded growth in many of these cities was a consequence of their status as colonies of the major powers. In India and Africa the British colonial rulers passed laws to prevent the native populations moving from the country to the city and to control the movements and living arrangements of those in the cities. French imperialism imposed similar restrictions in those parts of Africa under its control. It seems logical to see these restrictions as linked to the status of many of these countries as suppliers of raw materials to their colonial masters. However, even in Latin America, where the colonial hand was arguably less severe, the local bourgeoisie could be equally opposed to their rural countrymen and women intruding into the cities. Thus in the late 1940s there were crackdowns on the squatters drawn to urban centres such as Mexico City as a result of the policy of local industrialisation to replace imports.

This changed as colonialism ended and capitalism became ever more global. Cities began to grow in size and increase in number. In 1950 there were 86 cities in the world with populations of over one million. By 2006 this had reached 400 and by 2015 is projected to rise to 550. The urban centres have absorbed most of the global population growth of recent decades and the urban labour force stood at 3.2 billion in 2006.[12] This last point highlights the fact that in countries such as Japan, Taiwan and, more recently, India and China this growth is linked to the development of production. One consequence of global significance is that over 80% of the industrial proletariat is now outside Western Europe and the US. In China hundreds of millions of peasants have flooded from the countryside to the cities, principally those in coastal regions where most industrialisation has taken place; hundreds of millions more are likely to follow. By 2011 the majority of China’s population was urban.[13]

This can give the impression that the process seen in the 19th century is continuing; that the early chaotic development will be replaced by a more steady progression up the value chain of production with resulting increases in wages, prosperity and the domestic markets. This is used to support the argument that capitalism remains dynamic and progressive and that in time it will lift the poor out of poverty, feed the starving and house the slum dwellers.

However, this is not the full story of the current period. In many other countries there is no link between the development of cities and the slums that go with them and the development of production. This can be seen by comparing cities by size of population and GDP. Thus, while Tokyo was the largest by population and by GDP, Mexico City, which was the second largest by population, does not figure in the top ten by GDP. Similarly Seoul, which is fourth largest by population also does not appear amongst the top ten by GDP. In contrast, London, which was sixth by GDP, is 19th by population.[14] Population growth in these cities seems more a consequence of wider economic changes, such as the reorganisation of agriculture to meet the requirements of the international market and fluctuations of the price of raw materials on the one hand and the often linked impact of war, ‘natural’ disasters, famine and poverty on the other. In some cities, such as Mumbai, Johannesburg and Buenos Aires there has actually been de-industrialisation. Davis also highlights the neo-liberal policies of the IMF as having a particular role in this process and in the impoverishment of many of the recipients of its ‘aid’ and ‘advice’.

The consequences can be seen in the shanty towns that encircle many cities in the south. While it is the megacities that hit the headlines, the majority of the urban poor live in second tier cities where there are often few, if any, amenities and which attract little attention. The accounts of the living conditions of the inhabitants of these slums that run through Planet of Slums echo parts of Engels’ analysis. In the inner cities the poor not only crowd into old housing and into new properties put up for them by speculators but also into graveyards, over rivers and on the street itself. However, most slum-dwellers live on the periphery of the cities, often on land that is polluted or at risk from environmental disaster or otherwise uninhabitable. Their homes may be made of bits of wood and old plastic sheeting, often without services and subject to eviction by the bourgeoisie and exploitation and violence by the assorted speculators, absentee landlords and criminal gangs that control the area. In some areas squatters progress to legal ownership and succeed in getting the city authorities to provide basic services. Everywhere they are subject to exploitation.

As in England in the 19th century there is money to be made from misery. Speculators large and small build properties, sometimes legally, sometimes illegally, and receive rents, which for the space rented are comparable to the most expensive inner city apartments of the rich. The lack of services provides other opportunities, including the sale of water. The inhabitants within the slums are divided and sub-divided. Some who rent shacks may rent a room to someone even poorer. Some may have jobs that are more or less precarious, others scrape a living through petty trading or providing services to their fellow inhabitants. This mass of proletarians, semi-proletarians, ex-peasants and so on constitute a reserve army of labour that helps to lower the cost of labour regionally, nationally and, ultimately, globally. They also pose a threat to capitalist order and offend the sensibilities of the bourgeoisie just as the slum-dwellers of Britain did in the 19th century.

The bourgeoisie continues to try to ‘solve’ the housing crisis that its society creates. Today as in the past this is always circumscribed by what is compatible with the interests of the capitalist system and of the bourgeoisie within it. On the one hand, there have been attempts simply to bulldoze the problem away, evicting millions of the poor, whether workers, ex-peasants, petty-traders or the cast-offs of society, and dumping them in new slums, or in the open countryside, away from the eyes, ears and noses of the rich. On the other hand, a whole bureaucracy has grown up aimed at solving the housing problem, including the IMF, the World Bank, the UN as well as both international and local NGOs; but they always do so within the framework of capitalism. Thus, new housing often benefits the petty-bourgeoisie and better off workers who have the contacts or can pay the bribes or afford the rent, rather than those it was nominally intended for. A priority is usually to keep costs low, resulting in either barrack-like housing schemes or reforming the slums without ending them. The latter has seen a particularly unusual alliance between would be radicals who want to ‘empower’ the poor and international capitalist bodies such as the World Bank who want to find a market solution that encourages enterprise and ownership.

Finally, there is the unspoken but ever-present objective of dividing the exploited through the usual mix of co-option and repression. Thus bodies that begin with radical demands, such as squatters’ groups, often end up collaborating with the ruling class once they have been given a few concessions. Amongst some ideologues there are even echoes of the past, such as the idea that the solution lies in providing the poor with legal entitlement to the land on which they are living. This echoes the ideas that Engels combated in the first part of The Housing Question that deals with the claims by a follower of the anarchist Proudhon that providing workers with the legal title to the property they are living in will solve the housing question. Engels shows that this ‘solution’ will rapidly lead back to the original problem since it does not change the basic premise of capitalist society that “enables the capitalist to buy the labour power of the worker at its value but to extract from it much more than the its value…”[15]

In the old capitalist heartlands of Western Europe and the US, the return of the open economic crisis at the end of the 1960s led to two major changes that impacted on the provision of housing for the working class. The first was the need to reduce the expenditure of the state, and especially the social wage paid to workers; the second was the shift of capital from productive investment to speculation where the returns seemed higher. We will focus on Britain in examining this, as we did at the start of this article, mindful of the fact that the particular form taken varies from country to country.

The tightening of state spending led first to a slow down in the number of council houses built and then, under Thatcher, to the selling of the council housing stock and the restriction of further building by local authorities. This is frequently portrayed as an example of Thatcherite dogma and it is indeed true that it was partly an ideological campaign to promote home ownership. But none of this began with Thatcher. We have already noted the efforts to promote home ownership by both Tory and Labour governments both before and after the Second World War, principally through tax relief on mortgages. The selling of council houses not only reduced the capital costs of building homes but also the revenue costs of maintaining them, since the new owner assumed individual responsibility for this. The idea that owning property would help to curtail the threat from the working class goes back further still. In The Housing Question Engels quotes one Dr Emil Sax’s paean to the virtues of land ownership: “There is something peculiar about the longing inherent in man to own land…With it the individual obtains a secure hold; he is rooted firmly in the earth…The worker today helplessly exposed to all the vicissitudes of economic life and in constant dependence on his employer, would thereby be saved from this precarious situation; he would become a capitalist…He would thus be raised from the ranks of the propertyless into the propertied class.”[16]

Financial speculation became ever more feverish as the struggle to find a profitable return on capital became more intense over the last 40 years. The financial deregulation that was a feature in both Britain and the US in the 1980s allowed the bourgeoisie to develop ever more complex forms of speculation. In the 1990s money flowed into a range of new instruments based on the extension of credit to ever larger parts of the working class. The development of sub-prime mortgages in the US typified this approach. Speculators thought they were safe because of the complex nature of the financial instruments they were investing in and the high rating given to them by rating agencies such as Standard and Poor. The collapse of the sub-prime market in 2007 exposed this as the illusion it always was and laid the foundations for the wider collapse that followed, whose effects are still with us. In Britain ever-larger mortgages were offered with ever-smaller deposits and relaxed financial checks. The result was that mortgages made up the majority of the growth in personal credit that helped to underpin the ‘booms’ of the 1990s and early 2000s (the longest period of post-war growth as Gordon Brown used to claim).

The first housing bubble burst in the 1990s and plunged many into negative-equity, resulting in a high level of repossessions. This time round the bourgeoisie has managed to limit the impact so there are less repossessions. However, housing has now become less affordable due to a combination of the lasting increases during the bubbles and the tightening of credit following 2007, with the result that many young people can no longer afford to buy. At the same time, the rented sector has reduced. Council provision is limited and tightly controlled, with eligibility criteria that condemn younger people to small and poor accommodation if not to B&B. The new limits on Housing Benefit will also force families to move away from their home area or face being thrown on the street where one of the few options is to squat one of the thousands of empty properties. Thus we return to where we began.

The answer to the housing question

The housing question that confronts workers and other exploited classes around the world takes quite different forms in one country or another and often divides the victims of capitalism against each other. Between a young worker squatting on land prone to flooding or subject to industrial poisons on the margins of a city like Beijing or Mumbai and a young worker ineligible for a council flat in London or unable to get a mortgage on a house in Birmingham there can seem to be an unbridgeable gulf. Yet the question for all workers is how to live as a human being in a society subordinated to the extraction of profits from the many for the few. And for all the changes in the form and scale of the question the content remains the same. Engels’ conclusion remains as valid today as it was over a century ago: “In such a society the housing shortage is no accident; it is a necessary institution and can be abolished together with all its effects on health etc., only if the whole social order from which it springs is fundamentally refashioned”[17]

North 11/01/13

[1]. Guardian 03/12/12, “Squatters are not home stealers”. Part of the ideological campaign whipped up to justify the anti-squatting law involved loudly publicising cases where individual homeowners retuned from a period of absence to find their house being squatted

[2]. Ibid.

[3]. The Condition of the Working Class in England, “The Great Towns”. Collected Works Volume 4, Lawrence and Wishart p.331.

[4]. Ibid., p.332-3

[5]. The Housing Question, Part ii “How the bourgeoisie solves the housing question”. Collected Works, Volume 23, Lawrence and Wishart, p.337.

[6]. Ibid. p.365.

[7]. Ibid. p.366.

[8]. Ibid. p.368.

[9]. Stevenson British Society 1914-45, chapter 8 “Housing and town planning”. Penguin Books, 1984.

[10]. See Morgan, The People’s Peace. British History 1945-1990. Oxford University Press, 1992.

[11]. Davis, Planet of Slums, chapter 3 “The treason of the state”, Verso 2006. Much of the information that follows is taken from this work.

[12]. Ibid., chapter 1, “The urban climacteric”, p.1-2.

[13]. UN Habitat, The state of China’s cities 2012/13, Executive Summary, p.viii.

[14]. Davis op. cit. p.13.

[15]. Engels op cit., p.318

[16]. Engels, op.cit. p.343-4.

[17]. Ibid., p.341.

Recent and ongoing:

- Housing [8]

Rubric:

French intervention in Mali: another war in the name of peace

- 2739 reads

On 11 January 2013, the French president François Hollande launched Operation Serval to wage the ‘war against terrorism’ in Mali. Planes, tanks and men armed to the teeth are now being employed in the southern Sahel. As these lines are being written, bombs and machine guns are speaking and the first civilian victims have fallen. The British bourgeoisie has pledged planes and logistical support to the French effort, and Cameron has not ruled out the deployment of British troops. And the ‘blow back’ from this conflict has already appeared in the shape of the blood-soaked hostage crisis in Algeria.

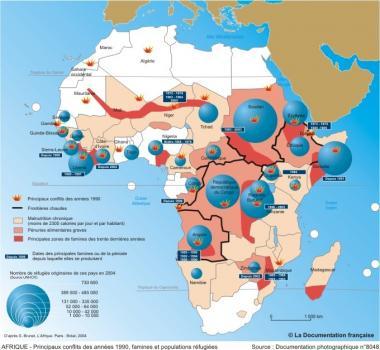

Once again the French bourgeoisie has thrown itself into an armed conflict in Africa. Once again, it is doing it in the name of peace. In Mali, it’s presented as a fight against terrorism and thus for the protection of the population. Quiet clearly, there’s no doubt about the cruelty of the armed Islamist gangs which reign in the north of Mali. These warlords sow war and terror wherever they go. But the motives behind the French intervention have nothing to do with the suffering of the local peoples. The French state is there only to defend its sordid imperialist interests. It’s true that the inhabitants of Mali’s capital, Bamako, have, for now, joyfully welcomed Hollande as their saviour. And these of course are the only images of this war which the media are disseminating right now: happy populations, relieved that the Islamist mafia’s advance towards the city has been halted. But this mood is not likely to last long. When a ‘great democracy’ passes through with its tanks, the grass is never green afterwards. On the contrary: desolation, chaos, and misery are the legacy of their intervention. The attached map shows the main conflicts which have ravaged Africa since the 90s and the famines which followed in their wake. The result is evident: each war – often carried out under the banner of humanitarian intervention, like in Somalia in 1992 or Rwanda in 1994 – has resulted in serious food shortages. It’s not going to be different in Mali. This new war is going destabilise the whole region and add considerably to the chaos.

An imperialist war

“With me as President, it’s the end of ‘Francafrique’”. François Hollande’s blatant lie would make us laugh if it didn’t mean a new pile of corpses. The left has never failed to talk about its humanism but for nearly a century the values it drapes itself with have served only to hide its real nature: a bourgeois faction like all the rest, ready to commit any crime to defend the national interest. Because that’s what we seeing in Mali: France defending its strategic interests. Like François Mitterand, who took the decision to intervene militarily in Chad, Iraq, ex-Yugoslavia, Somalia and Rwanda, Hollande has proved once again that the ‘socialists’ will never hesitate to protect their values – i.e. the bourgeois interests of the French nation – at the point of a bayonet.

Since the beginning of the occupation of the north of the country by the Islamist forces, the big powers, in particular France and the USA, have been egging on the countries of the region to get involved militarily, promising them money and logistical aid. But in this little game of alliances and manipulations, the American state seemed to be more adept and to be gradually gaining influence. Being outwitted in its own hunting ground was quite unacceptable for France. It had to react and react with some force: “At the decisive moment, France reacted by using its ‘rights and duties’ as a former colonial power. Mali was getting a bit too close to the USA, to the point of looking like the official seat of Africom, the unified military command for Africa, set up in 2007 by George Bush and consolidated since then by Barack Obama” (Courrier International, 17.1.13)

In reality, in this region of the world, imperialist alliances are an infinitely complex and very unstable web. Today’s friends can become tomorrow’s enemies when they are not both at the same time! Thus, everyone knows that Saudi Arabia and Qatar are the declared allies of France and the USA, but they are also the main suppliers of funds to the Islamist groups operating in the Sahel. It was thus no surprise to read in Le Monde on 18 January that the prime minister of Qatar had pronounced himself against the war France is waging in Mali and had questioned the pertinence of Operation Serval. And what can be said about superpowers like the USA and China who officially support France but have been whispering in the corridors and advancing their own pawns?

France will be bogged down for a long time in the Sahel

Like the USA in Afghanistan, there is every possibility that France is going to get stuck for an indefinite period in the quicksand of Mali and the Sahel in general (“for as long as necessary”, as Hollande put it). “While the military operation is justified because of the danger represented by the activities of the terrorist groups, who are well armed and increasingly fanatical, it is not exempt from risk in terms of getting bogged down and of instability throughout West Africa. Its difficult to avoid comparison with Somalia. Following the tragic events in Mogadishu at the beginning of the 90s, the violence in this country spread to the whole of the Horn of Africa and 20 years later stability has not returned there” (A Borgi, Le Monde, 15/1/13). This last point needs emphasis: the war in Somalia destabilised the whole of the Horn of Africa and “20 years later stability has not returned there”. This is what these ‘humanitarian’ and ‘anti-terrorist’ wars are really like. When the ‘great democracies’ brandish the flag of military intervention in defence of the ‘wellbeing’ of the population, of ‘morality’ and ‘peace’, they always leave ruin and the reek of death in their wake.

From Libya to the Ivory Coast and Algeria, the generalisation of chaos

“It’s impossible not to notice that the recent coup in Mali was a collateral effect of the rebellions in the north of the country, which were in turn the consequence of the destabilisation of Libya by a western coalition which strangely enough has shown no remorse or sentiment of responsibility. It’s also difficult not to recognise that this khaki harmattan[1], which has swept through Mali, has also passed through its Ivorian, Guinean, Nigerian and Mauritanian neighbours” (Currier International, 11.4.12). Many of the armed groups who fought alongside Gaddafi are now in Mali and elsewhere, having stripped bare the arms caches in Libya.

In Libya too the ‘western coalition’ claimed that it was intervening for justice and for the good of the Libyan people. Today the same barbarism is being experienced by the oppressed of the Sahel and chaos is spreading. Alongside the war in Mali, it’s Algeria’s turn to be destabilised. On 17 January a battalion organised by an offshoot of Al Qaida in the Maghreb kidnapped hundreds of employees of the gas plant at In Amenas. The Algerian army’s reaction was to rain fire on both kidnappers and hostages, leaving dozens dead. After this butchery, Hollande spoke like any other warmonger in defence of ‘his’ side “a country like Algeria has responses which, it seems to be, are the most suitable because there could not be any negotiation”. This spectacular entry of Algeria into the war in the Sahel, saluted by a head of state caught up in the logic of imperialism, is an expression of the infernal cycle into which capitalism is falling. “For Algiers, this unprecedented action on its own territory has plunged the country a little deeper into a war which it wanted to avoid at all costs, out of fear of the consequences inside its own frontiers” (Le Monde, 18.1.130).

Since the beginning of the crisis in Mali, the Algerian regime has been playing a double game, as can be shown by two significant facts: on the one hand it is openly ‘negotiating’ with certain Islamist groups, even supplying them with a large amount of fuel during their offensive towards the conquest of Konna on the road to Bamako; on the other hand, Algiers has authorised French planes to fly over its air space to bomb the jihadist groups in the north of Mali. This contradictory position, and the ease with which the jihadists gained access to the most securitised industrial site in the country, shows just how much the Algerian state is succumbing to a process of decomposition. Like the states in the Sahel, Algeria’s entry into the war can only accelerate this process.

All these wars show that capitalism is descending into a very dangerous spiral which is a threat to the very survival of humanity. More and more zones are sinking into barbarism. We are witnessing a nightmarish brew made up of the savagery of the local torturers (warlords, clan chiefs, terrorist gangs...), the cruelty of the second string imperialist powers (small and medium sized states) and the devastating firepower of the big nations – all of them ready to get involved in any intrigue, any manipulation, any crime, any atrocity to defend their pathetic, squalid interests. The incessant changing of alliances gives the whole thing the look of a danse macabre, a dance of death.

This moribund system is going to sink deeper, these wars are going to spread to more and more regions of the globe. To choose one camp against the other, in the name of the lesser evil, is to participate in this dynamic which has no other outcome than the destruction of humanity. There is only one realistic alternative, one way to escape this hellish forced march: the massive, international struggle of the exploited for a new world without classes or exploitation, without poverty and war

Amina 19.1.13

Recent and ongoing:

- Mali [12]

Rubric:

Greece: Curing the economy kills the sick

- 2200 reads

In December 2012, the German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reported on a visit to Greece.

“In October 2012 the trauma therapist Georg Pier made the following observations in Greece: ‘Very pregnant women hurried desperately from one hospital to the next. But since they had neither any medical insurance nor sufficient money nobody wanted to help them give birth to their children. People, who until recently were part of the middle classes, were collecting residues of fruit and vegetables from the dustbins. (…) An old man told a journalist, that he could no longer afford the drugs for his heart problems. His pension was cut by 50% as was the case with many other pensioners. He had worked for more than 40 years, thinking that he had done everything right; now he no longer understands the world. If you are admitted to a hospital, you must bring your own bed-sheets as well as your own food. Since the cleaning staff were sacked, doctors and nurses, who have not received any wages for months, have started to clean the toilets. There is a lack of disposable gloves and catheters. In the face of disastrous hygienic conditions in some places the European Union warns of the danger of the spreading of infectious diseases.” (FAZ, 15/12/12).

The same conclusions were drawn by Marc Sprenger, head of the European Centre for the Prevention and Control of Diseases (ECDC). On 6 December, he warned of the collapse of the health system and of the most basic hygiene measures in Greece, and said that this could lead to pandemics in the whole of Europe. There is a lack of disposable gloves, aprons and disinfectant sheets, cotton balls, catheters and paper sheets for covering hospital examination beds. Patients with highly infectious diseases such as tuberculosis are not receiving the necessary treatment, so the risk of spreading resistant viruses in Europe is increasing.

A striking contrast between what is technically possible and capitalist reality

In the 19th century many patients, sometimes up to a third, died due to lack of hygiene in hospitals, in particular women during childbirth. While in the 19th century these dangers could be explained to a large extent through ignorance, because many doctors did not clean their hands before a treatment or an operation and often went with dirty aprons from one patient to the next, the discoveries in hygiene for example by Semmelweis or Lister allowed for a real improvement. New hygiene measures and discoveries in the field of germ transmission allowed for a strong reduction in the danger of infection in hospitals. Today disposable gloves and disposable surgical instruments are current practice in modern medicine. But while in the 19th century ignorance was a plausible explanation for the high mortality in hospitals, the dangers which are becoming transparent in the hospitals in Greece today are not a manifestation of ignorance but an expression of the threat against the survival of humanity coming from a totally obsolete, bankrupt system of production.

If today the health of people in the former centre of antiquity is threatened by the lack of funds or insolvency of hospitals, which can no longer afford to buy disposable gloves, if pregnant women searching for assistance in hospitals are sent away because they have no money or no medical insurance, if people with heart disease can no longer pay for their drugs … this becomes a life-threatening attack. If, in a hospital, the cleaning staff who are crucial in the chain of hygiene are sacked and if doctors and nurses, who have not been receiving any wages for a long time, have to take over cleaning tasks, this casts a shocking light on the ‘regeneration’ of the economy, the term which the ruling class uses to justify its brutal attacks against us. ‘Regeneration’ of the economy turns out to be a threat to our life!

After 1989 in Russia life expectancy fell by five years because of the collapse of the health system, but also due to the rising alcohol and drug consumption. Today it’s not only in Greece that the health system is being dismantled step-by-step or is simply collapsing. In another bankrupt country, Spain, the health system is also being demolished. In the old industrial centre, Barcelona, as well as in other big cities, emergency wards are in some cases only kept open for a few hours in order to save costs. In Spain, Portugal and Greece many pharmacies no longer receive any vital drugs. The German pharmaceutical company Merck no longer delivers the anti-cancer drug Erbitux to Greek hospitals. Biotest, a company selling blood plasma for the treatment of haemophilia and tetanus, had already stopped delivering its product due to unpaid bills last June.

Until now such disastrous medical conditions were known mainly in African countries or in war-torn regions; but now the crisis in the old industrial countries has lead to a situation where vital areas such as health care are more and more sacrificed on the altar of profit. Thus medical treatment is no longer based on what is technically possible: you only get treatment if you are solvent![1]

This development shows that the gap between what is technically possible and the reality of this system is getting bigger and bigger. The more hygiene is under threat the bigger the danger of uncontrollable epidemics. We have to recall the epidemic of the Spanish flu, which spread across Europe after the end of WW1, when more than 20 million died. The war, with its attendant hunger and deprivation, had prepared all the conditions for this outbreak. In today’s Europe, the same role is being played by the economic crisis. In Greece, unemployment rose to 25% in the last quarter of 2012; youth unemployment of those aged under 25 reached 57%; 65% of young women are unemployed. The forecasts all point to a much bigger increase – up to 40% in 2015. The pauperisation which goes together with this has meant that “already entire residential areas and apartment blocs have been cut off from oil supplies because of lack of payment. To avoid people freezing in their homes during the winter, many have started to use small heaters, burning wood. People collect the wood illegally in nearby forests. In spring 2012 a 77 year old man shot himself in front of the parliament in Athens. Just before killing himself, he is reported to have shouted: ‘I do not want to leave any debts for my children’. The suicide rate in Greece has doubled during the past three years” (op cit)

Next to Spain with the Strait of Gibraltar, Italy with Lampedusa and Sicily, Greece is the main point of entrance for refugees from the war-torn and impoverished areas of Africa and the Middle East. The Greek government has installed a gigantic fence along the Turkish border and set up big refugee camps, in which more than 55,000 ‘illegals’ were interned in 2011. The right wing parties try to stir-up a pogrom atmosphere against these refugees, blaming them for importing ‘foreign diseases’ and for taking resources that rightfully belong to ‘native Greeks’. But the misery that drives millions to escape from their countries of origin and which can now be seen stalking the hospitals and streets of Europe stems from the same source: a social system which has become a barrier to all human progress.

Dionis 4/1/13

[1]. In ‘emerging’ countries like India more and more private hospitals are opening, which are only accessible to rich Indian patients and to more solvent patients from abroad. They offer treatment which are far too expensive for the majority of Indians. And many of the foreign patients who come as ‘medical tourists’ to the Indian private clinics cannot afford to pay for their treatment ‘at home’.

Recent and ongoing:

- Health Care [14]

- Crisis in Greece [15]

Rubric:

The History of Sport Under Capitalism (Part I) - Sport in the ascendant phase of capitalism (1750-1914)

- 3800 reads

For a long time sport has represented a phenomenon that cannot be ignored from the fact of its cultural breadth and its place in society. A mass phenomenon, it's imposed on us through the tentacles of many institutions and results in a permanent hammering from the media. What significance can we give it from the point of view of a historical understanding and from the point of view of the working class?

In this first part we are going to try to give some responses by looking at the origins and function of sport in ascendant capitalist society.

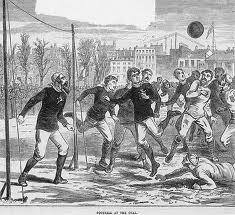

A pure product of the capitalist system

The word "sport" is a term of English origin. Inherited from popular games and aristocratic entertainments, it was born in England with the beginnings of large capitalist industry.

Modern sport clearly distinguishes itself from the games, entertainments or physical activities of the past. If it inherited practices from them, it's because it oriented itself exclusively towards competition: "It was necessary that the development of the productive forces of capitalism were important enough for the abstract idea to make itself apparent to the masses from concrete works (...) similarly it was necessary for the long development of physically competitive practices so that little by little the idea of physical competition became generalised"[1]. The horsemanship of the aristocracy ended up with racecourses. It's around this that the stopwatch was invented, in 1831. From 1750, the English Jockey Club promoted numerous racecourses whose appearances continued apace. It was the same with running and other sports. Football came from the matches of Cambridge, 1848, and the Football Association appeared in 1863; tennis was transformed much later providing the first tournament in 1876. In brief, the new disciplines were all geared towards competition: "Little by little, sport broke free from the confused chaos and complexities of the time in order to form a coherent and codified body of highly specialised and rationalised techniques adapted to the mode of capitalist/industrial production"[2]. In the same way that wage labour is linked to production in capitalist society, sport incarnated "abstract materialisation made flesh"[3]. Very quickly the search for performance and records, along with bookmakers and betting, fed a diversity of sporting activity which became a real, popular infatuation, allowing the factory to be forgotten for the moment. This was the case for example with cycling and the Tour de France (a sort of a "free party") from 1903, boxing, football, etc. In line with the development of the capitalist system, transports and communications, sport took off in Europe as in the rest of the world. The extension and institutionalisation of sport, the birth and multiplication of national federations, harmonised with the heights of the capitalist system from the 1860s, but above all in the last decades of the 19th century and the beginning of the twentieth. It's a time when sport really internationalised itself. Football for example, was introduced into South America by European workers who were employed in the railway workshops. The first international sporting grouping was the International Union of Yacht Racing in 1875. Then others appeared: International Horse Show Club in 1878, International Gymnastic Federation in 1881, bodies for rowing and skating in 1882, etc. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was founded in 1894, FIFA (International Federation of Associated football) in 1904. Most of the international bodies were set up before 1914.