World Revolution 2012

- 2791 reads

World Revolution no.351, February 2012

- 2249 reads

Austerity won’t save capitalism from declining

- 2297 reads

After a miserable 2011, characterised by rising unemployment, inflation and increased hardship for workers everywhere, most people were probably hoping that 2012 would offer some hope for improvement or at least some relief from the relentless assaults on living standards.

Unfortunately, such hopes are increasingly utopian as capitalism continues to grapple with the consequences of the worst economic crisis in its history. The remorseless unfolding of the crisis is pushing every aspect of the capitalist social structure towards breaking point at all levels of society.

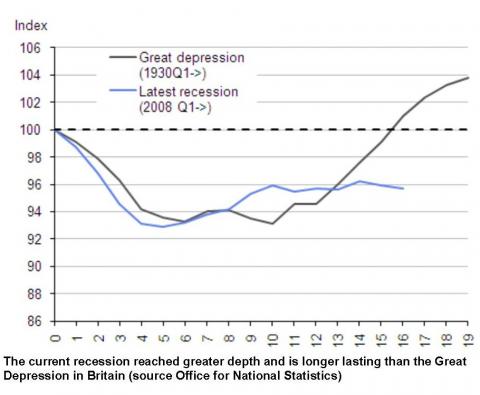

In the Eurozone, the impossibility of resolving the debt crisis becomes more obvious every day. The head of the IMF has warned that “the world faces an economic spiral reminiscent of the 1930s unless action is taken on the eurozone crisis”. Several countries in Europe were victim of the recent round of credit rating downgrades, most significantly France. France’s situation is important because their rating has a knock-on effect of the perceived stability of the European bail-out mechanisms, which in turn affect market confidence in the ability of Europe to control the crisis.

The reasons given by S&P, the rating agency concerned, is revealing: “we believe that a reform process based on a pillar of fiscal austerity alone risks becoming self-defeating, as domestic demand falls in line with consumers’ rising concerns about job security and disposable incomes, eroding national tax revenues” (www.standardandpoors.com [2]). Without growth, debt reduction becomes impossible - and yet the only way capitalism has to stimulate growth is by government intervention, thus increasing debt! Capitalism is caught in a vicious pincer movement from which it cannot escape.

Closer to home in Britain, the latest GDP figures indicate a contraction of 0.2% in the last quarter of 2011, threatening a new recession. Industrial production is in decline once again, down 2.9% in the year to November, indicating that manufacturing’s brief renaissance on which the ruling class had pinned their hopes has now run out of steam.

Headlines were also made as government net debt passed the £1 trillion mark. The net debt of the state is now 61% of GDP with gross debt at 81%. In fact, Britain’s state debt is lower than that of France and Germany, but its deficit (i.e. the rate at which that debt grows) is much higher. But although it’s state debt that continues to grab the headlines, this focus serves to mask a far deeper problem at the root of the capitalist economy.

Overall debt in Britain (public and private sector) is a staggering 507% of GDP. This means that the entire country would have to work for nothing for 5 years to repay it! The liabilities of the finance sector alone are well over 200% of GDP.

Debt is a form of capital and, like all capital, has to be worked in order to maintain its value and to grow. In practice, this means that it must employ workers who must then produce surplus value (i.e. the value above and beyond what workers have to consume in order to live) which is then paid to the boss in the form of profit. Out of this profit, the capitalist pays back the original capital plus interest. Obviously workers can take out credit too, in which case they pay the interest directly to the capitalist out of their own wages. When governments borrow, they pay back their loans from taxes which are taken from company profits (produced by workers) or wages (again, from workers).

If the borrower cannot squeeze enough surplus value out of the working class to pay off the debt (with interest) then the capital becomes worthless, capitalists go out of business and defaults on the loan while workers are laid off. If many borrowers encounter this problem, a whole wave of such defaults can wipe out the banking system. This is precisely what nearly happened in 2008.

The enormous scale of the debt problem shows quite clearly the underlying structural crisis facing capital, one that can only be answered by extracting more and more value from the working class.

All the left and liberal campaigns about making the rich pay their taxes are thus based on a fantasy. Forcing the rich to pay their taxes so that the state can pay back money to ... the rich! And even were they actually carried out, they wouldn’t begin to scratch the surface of the wider problem as the gigantic level of debt indicates.

What about the argument that austerity measures are self-defeating and should be stopped? The left often points this out and, as we saw earlier, elements within the economic apparatus of the ruling class sometimes also support this view. The problem with this approach is that this inevitably means contracting more debt to fund government spending. It doesn’t help capitalism extract more value from workers (unless, as is often the case, the increased deficit spending creates inflation) and thus doesn’t solve the underlying problem. Growth may appear to take off but actual profits remain depressed, debt increases until it becomes obvious it cannot be repaid, markets panic and the economy falls into recession. In other words, a replay of the same scenario that brought capitalism to the current precipice.1

The so-called “debt crisis” is not really about debt, but a crisis at the level of the capital-labour relationship. Essentially, capitalism cannot exploit us enough to keep itself going and must increase that exploitation as much as it can. Whatever form it takes (government spending cuts, unemployment, pay freezes, etc.), the current austerity is absolutely essential from the point of view of capital and there is no choice about it as long as the system remains in place. The only question is how far they feel they can go in implementing that austerity before the working class feels compelled to respond.

Selling austerity to the workers

So far in Britain, the ruling class has been quite successful in its efforts to impress this reality upon the majority of the population. In spite of some high profile strikes and protests, like the big public sector strike on November 30th, a recent poll (mobile.bloomberg.com) suggests 74% of the population support the current programme of cuts. Whatever the merits or otherwise of such polls, it is clear that the response to the avalanche of crisis and austerity has had a mixed reaction within the mass of the working class.

Nonetheless, the ruling class is keeping a close eye on the social front. The determination and violence of the student struggles, while not posing any immediate or direct threat to class rule, reminded the ruling class that the proletariat is not completely under the thumb. The naked application of state force against the students had the potential to strip away illusions about democracy from a whole generation. The explosion of long-term unemployment amongst both the young and the old also has the potential to radicalise the population. The present capitalism has to offer young people is highly indicative of the future it has to offer the whole of society, while unemployment amongst older workers makes the programme of attacks on pensioners harder to sustain ideologically - it is difficult to convince workers that they’ll have to work longer when work itself is so hard to come by.

The bourgeoisie have thus maintained a whole series of campaigns with the aim of keeping the myth of democratic debate alive. To start with, the Labour party maintained the position that the cuts were going “too far, too fast”. As public support has shifted behind the cuts agenda, this element is no longer needed and Labour is even more blatantly pro-cuts. This has manifested in the recent questioning of Miliband’s leadership and Ed Balls’ proclamations in favour of a pay-freeze for public sector workers.

One strand of Labour’s ideology that has been taken up more widely, however, is the issue of “fairer capitalism”. Labour has run a sustained campaign on this question and now Cameron has recently jumped on the bandwagon with his recent critique of the “out of control” bonus culture in the banks and talk about making “everyone share in the success of the market”.

The flipside of the “fairer capitalism” campaign is the open season on bankers’ bonuses. The entire media have joined in the circus with politicians and media pundits from across the political spectrum lining up to criticise the £963,000 share option given as a bonus to the boss of RBS, on top of his £1.2 million annual salary. The monolithic nature of this theme across left and right is an indicator that this is no accident but a co-ordinated effort to provide a public target for the growing anger of the masses and allows the ruling class to hide the true depth of the underlying systemic crisis.

What the ruling class fears above all is that the necessary acceleration of the attacks could still trigger a radical response within the working class. With no alternative but to push ahead regardless, the incessant ideological assaults are aimed at ensuring that workers’ questions about the future of society stay locked within the stultifying framework of capitalism.

Ishamael 28/1/12

1. It will be noted that the explanation for the origins of the present crisis in this article expresses a minority view within the ICC, since it emphasises the problem of extracting sufficient surplus value rather than the problem of realising it on the market. Both approaches, however, are consistent with our overall marxist framework which insists that the crisis does not derive from surface phenomena like the tricks of the bankers but from the fundamental social relation in this society: “the capital-labour relationship”.

Recent and ongoing:

Lives lost in the pursuit of profit

- 1784 reads

At the time of writing 17 bodies have been found and as many as 20 passengers are still unaccounted for following the shipwreck of the Costa Concordia off the Italian island of Giglo on 14th January.

The captain of the ship became the immediate target of blame after denying that he had rushed to get off before the passengers and was only in a lifeboat because he ‘fallen’ into it and was simply unable to get back on board as he wanted to. He also claimed the rocks he steered the ship onto and which ripped its hull open were not on his map. Reports followed that he might have been drinking or was showing off, possibly to a mystery woman, and that he had delayed getting the passengers off for an hour.

Costa Cruises, which operates a large number of similar ships and whose parent company, Carnival Corporation, owns 10 cruise providers, was quick to join in. The day after the incident, after noting that “the investigation is ongoing”, the company was nonetheless able to conclude “preliminary indications are that there may have been significant human error on the part of the ship’s Master, Captain Francesco Schettino, which resulted in these grave consequences. The route of the vessel appears to have been too close to the shore, and the Captain’s judgement in handling the emergency appears to have not followed standard Costa procedures.”

Whatever blame the Captain may or may not deserve, it is clear that there are wider issues. Concerns had already been raised about the design of the current generation of cruise ships[1] by Nautilus International, a maritime trade union, with safety being compromised for commercial reasons. For example, shallow draughts allow passengers to board easily, but can cause stability problems in certain circumstances. The Costa floated 13 storeys with only 8 metres of hull underwater. The ship was little more than a floating tower block, albeit one with gaudy glamour (such as copy of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the dining room) whose sole purpose is make profits.[2]

This practice seems widespread in the cruise industry as more and more people are crammed on to more and more decks with the addition of swimming pools, shopping malls and other ‘amenities’ to ease the money from their pockets. The next generation of ships may carry 6,000 people with crews of 1,800; the latter no doubt recruited from poor countries where workers are willing to accept low wages and poor conditions just to have a job. Fear of unemployment prevents workers from raising fears about safety or complaining about poor training. On the Costa Concordia a full evacuation drill had not been carried out; the crew seemed unclear what to do (apparently telling passengers to return to their rooms where they may have been unable to escape) and there may have been unregistered passengers on board. The company itself seems to have encouraged the practice of ‘salutes’ with ships sailing very close to the shore.

A ship with a massive superstructure that gives the impression of wealth and power above a shallow, unstable hull, sailing close to ‘uncharted’ rocks, with the captain distracted and looking after number one; the owners focussed on their own interests and ready to throw the captain overboard; the whole ship rolling over and sinking when it hits trouble and gradually slipping under while rescue attempts are made; you could be forgiven for thinking that the disaster was a metaphor for the crisis of capitalism. It might even be funny if the cost wasn’t paid by innocent people.

North 27/01/12

[2]. In 2010 Carnival Corporation and PLC reported total revenues of $14,469m, total costs of $12,122m and a net income of $1,978m. In 2009 the net income was $1,790m and in 2008 $2,324m. See: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/815097/000119312511018320/dex13.htm [7]

Recent and ongoing:

Rubric:

Reflections on the riots of August 2011 (part 2)

- 2118 reads

This article is a contribution to the discussion within the revolutionary movement about the nature of the riots that took place in Britain last August. In the first part of this article, published online[1], we put the question of ‘riots’ within the context of the historical struggle of the working class and argued that the response of revolutionaries to any particular event is not determined by the language and analysis of the ruling class but by the extent to which it advances or holds back the interests of the working class and that this can essentially be determined by the impact it has on the organisation and consciousness of the working class. We looked briefly at how this has been elaborated in theory and practice in the history of the working class. In this second part we turn to the events of last summer and attempt to apply the framework developed in the first part.

This echoes the analysis made by Engels in the 1840s of the response of the newly emerged working class to its situation: “The failings of the workers in general may be traced to an unbridled thirst for pleasures, to want of providence, and of flexibility in fitting into the social order, to the general inability to sacrifice the pleasure of the moment to a remoter advantage. But is that to be wondered at? When a class can purchase few and only the most sensual pleasures by its wearying toil, must it not give itself over blindly and madly to those pleasures? A class about whose education no one troubles himself, which is a playball to a thousand chances, knows no security in life – what incentives has such a class to providence, to ‘respectability’, to sacrifice the pleasure of the moment for a remoter enjoyment, most uncertain precisely by reason of the perpetually varying, shifting conditions under which the proletariat lives? A class which bears all the disadvantages of the social order without enjoying its advantages, one to which the social system appears in purely hostile aspects – who can demand that such a class respect this social order? Verily that is asking much! But the working-man cannot escape the present arrangement of society so long as it exists, and when the individual worker resists it, the greatest injury falls upon himself.”[2] Today, that part of the working class that the bourgeoisie variously describes as the “underclass”, “the criminal elements” or in their more apoplectic moments as scroungers and vermin and “feral youth”, lives in a way that echoes the first decades of the working class. Thus bourgeois society in its senility returns to the weaknesses of its infancy.

The limited nature of the riots

The riots themselves were actually of fairly short duration, scattered across a number of major cities in England,[3] and, with some notable exceptions, causing relatively little lasting damage.[4] In all, it has been reported that about 15,000 took part, but few of the individual incidents seem to have involved very large numbers. The figures collated of those arrested gives a picture of those involved as being mainly young males, from the most deprived areas of the cities involved and often with histories of previous convictions.[5] However, as Aufheben point out in their useful empirical examination of the riots this partly reflects the fact that it was easier to arrest those already known to the police who allowed their faces to be seen.[6]

The primary target seems to have been the acquisition of commodities, usually through breaking into shops, principally large retail chains but also smaller ‘local’ shops. The destruction of people’s homes seems to have been a result of thoughtlessness and indifference rather than deliberate targeting. The police and other symbols of the state were also targets, with the rioters interviewed particularly emphasising this aspect. To a lesser extent ‘the rich’ were also targeted, although it is unclear how intentional this actually was or whether this was a consequence of going after the more expensive commodities in such areas.[7]

Interviews with young people either involved in the riots or living in the areas where they occurred give a mix of explanations, but there is a stress on the lack of hope in the future and the anger this provokes: “People are angry, some people wanted to get the government to listen, some are angry but don’t know why yet ... the younger ones anyway, they’ve got the same shit to come as us, nowhere to go and it will be worse by the time they’re 17 and 18.”;[8] “I’m not saying I know why people kicked off, but I do think most people ... and kids are angry, angry about jobs, no housing, no training... just that theres no help, no way to do better”;[9] “[the looting] was an opportunity to stick two fingers up at the police… People have no respect [for the police] because the police have no respect ... they abuse the badge.”[10] This chimes with research undertaken for the government: “The document said they [the participants in the riots] were motivated by ‘the thrill of getting free stuff – things they wouldn’t otherwise be able to have’, and antipathy towards the police. The death of Mark Duggan, whose shooting by police initially prompted protests in Tottenham on 6 August, which were followed by rioting, motivated some in London to ‘get back’ at the police, the report said. It added: ‘Outside London, the rioting was not generally attributed to the Mark Duggan case. However, the attitude and behaviour of the police locally was consistently cited as a trigger outside as well as within London.’”[11]

This is not to belittle the physical harm suffered by those innocently caught up in the events or targeted by those involved, nor the distress of those who lost their homes and livelihoods. For some of those individuals the impact has been devastating and will remain with them for the rest of their lives. However, every day now workers are losing their livelihoods and their homes as a result of the attacks of the ruling class and many will never recover. Of this the bourgeoisie says nothing, or merely that it is the price “we” have to pay for the extravagance of yesterday and the promise of tomorrow.

The riots damaged the working class not capitalism

How do this summer’s riots relate to the framework we have set out?

Firstly, the riots reflected the domination of the commodity culture rather than being any challenge to it. In the looting that took place it seems to have been the exchange value of commodities that predominated. The looting of commodities was an end in itself, repeating in a distorted form the message of the bourgeoisie that the accumulation of commodities is how one is defined. To steal a TV without the means to use it – to take the example given by the Situationists in 1965 and echoed in one of the commentaries on the riots[12] – is not to question the commodity spectacle of capitalism but to succumb to it (although the real explanation is probably far more prosaic, with the TV being sold to get the means to buy commodities that the “appropriator” can use – understandable but hardly a threat to the commodity of the spectacle). The notion of “proletarian shopping” put forward as a concept by some, may appear to be opposed to bourgeois laws and morality but outside the proletarian framework of collective action to defend common interests, the individual acquisition of commodities actually never escapes the most basic premise of capitalism: property. At best, such individual appropriation may allow the individual and those around them to survive a little better than before. Again, understandable, but again no threat to the commodity culture.[13]

Secondly, and most damagingly, the riots divided the working class and handed the bourgeoisie an opportunity to undermine the tentative signs of militancy and unity in the working class that have been expressed in some scattered struggles in recent years and which are part of the international development of class struggle and consciousness that is a possibility today. The response of fairly large numbers of people, including members of the working class, of seeking to defend themselves, their families and homes against the riots, while also understandable, did not take place on working class terrain, as some anarchist groups seem to suggest,[14] but on that of the bourgeoisie and the petty-bourgeoisie. This could be seen most clearly in the participation in the clean up campaign that saw the likes of Boris Johnson ostentatiously waving a broom around in the air for the cameras.

The riots threw the ideology of the bourgeoisie back into its face. Those involved are no less moral than the ‘responsible’ bourgeoisie whose morality keeps this society of exploitation and despair ticking over. However, the main victim was the working class, partly physically but above all ideologically. The bourgeoisie was not only unscathed but emerged stronger and has pursued a constant ideological campaign since then. The working class did not gain through the experience of self-organisation, quite the opposite, and its consciousness was attacked by the reinforcing of the ideology of look after number one that resulted and of reliance on the state for security. The way the riots have been used by the bourgeoisie to reinforce its material and ideological weapons of control is far more significant than the riots themselves.

Thus, we have to ask to what extent did the bourgeoisie allow the riots to happen? The response of the police to the Duggan family’s protest was provocative, but possibly not more than is often experienced by those on the receiving end of police violence. Much is made of the failures of the police in the first hours, of the lack of numbers, their retreat from the streets and their failure to protect homes and shops. Were the police simply caught off-guard? Possibly. But it is also possible that once the spark had ignited they stood back. In this scenario, the ‘outrage’ of the press and politicians at the police abandoning the streets and the reports of families and ‘communities’ being left to fend for themselves all worked towards the same end of setting one part of the working class against another and of drowning any recognition of its common class interests in a morass of fear and anger.

The working class’ struggle has to go beyond the confines imposed by the bourgeoisie whether it be passivity or riots. Both express the domination of bourgeois ideology that the class struggle has to challenge through its solidarity and collective action and by opposing its perspective of the liberation of humanity from the domination of the commodity and the whole class society that it encompasses to that of the bourgeoisie. In the 19th century this was achieved through the unions as the mass organs of struggle and through the working class’ political organisations. In the present period, faced with the changed historical situation where capitalism is unable to decisively escape from its crisis and faced with betrayals of the unions and many of the original workers’ organisations in dragging workers in war and selling them out in deals with the bosses, the form but not the content of these struggles has changed. Today the mass organisations of the working class tend to form and disappear in the rhythm of the struggle, expressed in open mass assemblies while its political organisations are restricted to small minorities, largely isolated from the working class and frequently hostile to eachother. Nonetheless, they express the historical dynamic of the working class and in future, large scale and more decisive confrontations with the ruling class, the potential exists for the working class to go from mass assemblies to workers councils uniting and organising the collective power of the working class internationally,[15] within which the political organisations that defend the class interests of the working class have the obligation to work together to push forward the class dynamic by offering an analysis based on the historical experiences of the working class and by developing an intervention built on that analysis that enables the working class to navigate its course against the bourgeoisie to victory.

North 25/01/12

[1]. https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201112/4622/uk-riots-and-class-struggle-reflections-riots-august-2011 [10]

[2]. The Condition of the Working Class in England, “Results”, Collected Works, Vol.4, p 424.

[3]. A table compiled by the Guardian lists all of the locations identified. Including individual London boroughs this totals 42 locations and 245 separate incidents. Some of these, such as waste bins being set alight in Oxford hardly qualify as ‘rioting’. Most of the rioting occurred in London, Birmingham, Bristol, Coventry, Liverpool and Manchester.

[4]. It has been estimated that the total cost of the riots to the state will be £133m. Guardian 06/09/11 “Riots cost taxpayer at least £133m, MPs told”. Losses to individuals and businesses are not included in this total.

[5]. Figures issued by the Ministry of Justice in October show that of the 1,400 people arrested and awaiting a final outcome, over half were aged between 18 and 24 with just 64 being over 40. See also Guardian 18/08/11 “England rioters: young, poor and unemployed”.

[6]. Intakes: Communities, commodities and class in the August 2011 riots.

[7]. The broad categorisation of the targets of the riots draws on the evidence gathered by the research sponsored by the Guardian and on the analysis made by Aufheben.

[8]. Guardian 5/9/11 “Behind the Salford riots: ‘the kids are angry’”.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. Guardian, “Behind the Wood Green riots: ‘a chance to stick two fingers up at the police’”

[11]. Guardian 3/11/11 “Opportunism and dissatisfaction with police drove rioters, study finds”.

[12]. “An open letter to those who condemn looting” by Socialism and/or Barbarism.

[13]. Nor is this a new idea. In a letter to August Bebel (15th February 1886, Collected Works, Vol.47, p.407-8) Engels comments on the smashing of shop windows and the looting of wineshops “the better to set up an impromptu consumers club in the street”. However, Engels, perhaps, did not see this as a threat to bourgeois order.

[14]. See “ALARM on the riots” 13/08/11

[15]. Here the intelligence and energy displayed by some of the rioters in their use of social media to organise and respond to events and to outwit the forces of law and order will find a creative outlet.

Rubric:

Illusions in the unions will lead to defeat

- 1950 reads

For 5 months electricians have been demonstrating and picketing in order to build resistance to the new Building Engineering Services National Agreement (BESNA) conditions, involving a deskilling and reduction of pay by 35%. Protest meetings and pickets several hundred strong have been held outside construction sites run by the 7 BESNA firms every week around the country, seeking support from sparks whoever they work for, from other building workers, whatever their trade, whether they are unionised or not, from students when they were also demonstrating in London on 9th November, from Occupy London at St Pauls. Where they have sought solidarity they have found it, at least from a minority. On 7th December they expected to be on official strike after 81% voted in favour, only to have the result challenged by the employers and the strike called off. Many of them took part in a militant wildcat strike, complete with pickets several hundred strong going from site to site.

Yet in spite of this effort sparks are more and more frustrated that the struggle isn’t developing, knowing that the present level of action is no-where near enough to defend their current pay and conditions – which are in any case not always honoured, especially by agencies. In particular, strike action continues to be delayed. To make matters worse, after months of the Rank and File calling on workers not to sign the new agreement, not to give in to the employers’ blackmail and threats to terminate their jobs if they don’t, Unite has now advised them to sign the agreements in order to keep their jobs. “Received my letter from unite and telling us to sign the besna … sold down the river by the union and we aint had the ballot yet”, “I can see their thinking from a legal view point but the timing could not be worse” (posts on https://www.electriciansforums.co.uk [11]).

Why is it so hard to struggle today?

This is obviously a tough period, the whole working class is losing out as even those not facing a nominal pay cut are worse off due to inflation. Unemployment is high, jobs are scarce. And in the building industry, with the need to move from site to site and the blacklisting of militant workers, struggle takes real courage.

But there is more to it. Militant sparks have spent all these months pressuring Unite to organise a ballot and strike action, and are now expecting this will lead to a strike in February – after many have been forced to sign the new agreement or lose their jobs. Once the strike starts in Balfour Beatty they hope it will spread to other sites. Rank and File speakers at the pickets in London were very pleased that Len McCluskey had promised them full support at the beginning of the year including an unlimited budget for the struggle, and that there will be an elected Rank and File representative at all meetings with a view to preventing a sell-out.

Frustration with Unite’s delaying tactics has been huge with all sorts of ideas put forward on the electricians’ forum:

* There have been sell-outs and sweetheart deals between union and bosses before. Obviously true, but it doesn’t explain why.

* Self-serving union bureaucrats, “The lazy FTO’s use it for a wage and fat pension”. Many former militant workers become union Full Time Officials, so what is it about the union that corrupts them? Salary and pension or the way the union operates as a negotiating body?

* Unite is too big, “If only we had our own union and not lumped in with half the country”, “All they are interested in is the ‘hard done to’ public sector workers”. In fact the unions treat public sector workers just as badly as any others, for instance when Unison strike teachers’ unions tell their members to cross the picket line and vice versa. The one day protest strike and demonstration organised for public sector workers may have got publicity, but it really hasn’t taken the struggle forward at all.

* “But most of all lads have themselves to blame” for not being willing to struggle. Strangely enough, what makes it hard to enter struggle and to take the struggle forward – for the militant workers on the early morning pickets as well as those who are waiting for Unite to call them out and those who don’t have much confidence that they can do anything – is the view that even though “Unite is not an attractive proposition and has very little credibility with the average working spark”, “many sparks would never join it again”, they also feel “the sad fact is it is all we have and we must use it the best we can”.

The union is not all we have

What the sparks have already done shows that there is an alternative to the union methods of struggle. As was said at one of the protests at Blackfriars in January, it was symbolic that on 9th November Unite wanted to lead them to Parliament to lobby MPs, while workers wanted to go and joint the student protest. Union and rank and file wanted to go in totally different directions.

For the workers “we can only succeed with other trades and occupations reinforcing our ranks and standing alongside us in working class industrial solidarity, in a union or not, in common cause and purpose” (Siteworker), the complete opposite of a union ‘struggle’ limited to their members, and then only those employed by the particular employer they are negotiating with. Workers need to struggle with all their solidarity, with strong pickets, to prevent attacks on their pay, conditions and skills. For the unions the struggle is only an adjunct to negotiation, and time and again they agree to redundancies and austerity just so long as they can get round the table with employers and often government.

Sparks have been demonstrating, picketing, going on wildcats, trying to build a struggle – the only thing that can give confidence to others who may be hesitant to struggle. The union have been delaying with all sorts of excuses about needing to recruit, ballot, to do everything legally. It’s no wonder the full time organisers have been largely absent – what have workers’ protests got to do with that?

If we look further afield we can see that struggle, and sometimes very successful struggle, takes place without unions: textile workers in Bangladesh a couple of years ago; Honda workers in China (who were physically attacked by the state sponsored union). And of course the Indignant and Occupy movements across Europe and the US also show that people can get together and organise a struggle even without unions.

The unions are not all we have; in fact they no longer belong to us at all. All we have is ourselves, the working class.

The struggle is on a knife edge

Despite some upbeat speeches at protests in January, there is a general feeling that the dynamic is ebbing away from the sparks’ resistance to the BESNA attack. Unite’s ballot of Balfour Beatty employees will be announced in early February – the previous one was 81% in favour of action – with the expectation of a strike a week later. But it comes at a dangerous time – after Unite has ordered its members to sign the agreement, when the BESNA employers think they have won and many sparks fear they are right. Time and again unions have called a strike or a big demonstration just at the time when the will to struggle has been frustrated and exhausted, when it is set up for a defeat, leaving workers feeling powerless and demoralised. If this is allowed to happen, the negative lesson will not just hit electricians but all construction workers, giving the building employers an (undeserved) air of invincibility. The defeat of a militant section of the working class will also have consequences for the wider struggle.

Militant sparks are determined to take the resistance to BESNA forward by organising “buses to ferry pickets” and escalating the strike “no doubt other sites will support the BBES strike” (https://siteworker.wordpress.com/ [12]). But this will not be enough if the workers cannot take full control of the fight into their own hands and spread the struggle. Taking control doesn’t mean electing someone from the rank and file to oversee Unite, however militant they may be; it means organising mass meetings to discuss the struggle, take decisions and carry out those decisions collectively. Spreading the fight doesn’t mean just pulling in sparks from other firms; it means drawing in the other building trades and workers in other industries whether public or private sector. This is the only way to win.

Alex 27/1/12

Geographical:

- Britain [13]

Recent and ongoing:

Rubric:

Scottish nationalism shows growing divisions in the ruling class

- 1934 reads

The preparations for the referendum on Scottish independence, leaving aside Westminster’s legal wrangles over the wording, seem to be going ahead, prompting the question: is this for real, or is it just another form of the democratic diversion?

There’s no doubt that the ‘devolution of power’ to Wales and Scotland was part of the Labour government’s package of ‘reforms’ aimed at convincing the population that it really does have a stake in the governance of the realm. And Scottish National Party leader Alex Salmond has given a further pinch of salt to the democratic credentials of Scottish independence. In the recent Hugo Young lecture in London he contrasted Scotland’s retention of social democratic policies like free university education and no prescription charges with the nasty ConDem coalition’s flagrant attacks on education and the NHS.

But the situation has not remained static since the 2000s. What has changed above all is the overt deepening of the world economic crisis and the accompanying signs of serious political divisions within and between the national bourgeoisies of the advanced capitalist countries. The tensions between the Republicans and Democrats over raising the debt ceiling in the USA led, for a while at least, to a near paralysis of the central administration, while differences over the same basic problem – the enormous debts crushing economies like Greece, Italy and Spain – have not only caused governments to fall but more significantly have put a major question over the future of the Eurozone and the European Union itself. The economic impasse facing capitalism is accelerating the tendency for each faction of the ruling class, each national or sub-national unit, to save what it can from the wreckage.

In this situation, the arguments of the SNP seem more in tune with reality than they did in the past. They claim that Scotland, with its potential oil wealth and other assets like the tourist industry, could become a prosperous little Norway if it could just get its hands on the whole Scottish economy without interference (and taxation) from Westminster. And with Cameron clearly marking his distance with the EU over the issue of control over the financial sector, the SNP’s pro-EU position can be used to sell the prospect of an independent Scotland waxing rich under the protection of the European Central Bank.

Of course, given the insoluble nature of the global economic crisis, there will be no real possibility for small countries, or any countries for that matter, to preserve themselves as islands of economic well-being. And in any case, there are some basic realities of the imperialist system which make it extremely unlikely that Westminster will let Scotland detach itself from the UK anytime soon: not only the need to keep the lion’s share of the oil wealth but also the delicate question of the Trident missiles currently housed in Scotland.

Add to this the fact that, despite considerable electoral gains in recent years (above all, of course, its control of the devolved Scottish executive), the SNP can by no means assume that there is a majority in Scotland in favour of outright independence. This is why Salmond has been very careful to preserve the option of ‘devo max’ – a kind of Home Rule for Scotland within a maintained UK – as part of the agenda to be discussed in the lead-up to the referendum. In all probability this is what the SNP is really hoping for.

Leftist speculations

So while there are material forces pushing towards the fragmentation of even the most well-established nation states, full Scottish independence is probably not on the cards for the foreseeable future. But this doesn’t prevent the mouthpieces of pseudo-‘revolutionary socialism’ from indulging in all kinds of ridiculous speculation coupled with a typically reformist daily practice. The Socialist Workers Party for example:

“Socialist Worker backs independence for Scotland. This might seem like a contradiction as we are internationalists.

But we don’t back independence in order to line up behind the nationalists of the Scottish National Party.

The UK is an imperialist power that pillages the world’s resources.

A yes vote in the referendum would weaken the British state.

That’s why Cameron and friends are so desperate to preserve unity”. (Socialist Worker 14 January 2012)

So, while an independent Scotland would not be socialist, it would ‘weaken imperialism’. As a matter of fact, recent experience of the break-up of states into their constituent parts, such as the events in ex-Yugoslavia, shows that such developments merely provide other imperialist powers with added opportunities to intervene and to stir up national hatreds. The gains for the working class and for internationalism are nil.

A more sophisticated approach to the question is provided by the Weekly Worker (19 Jan), who pour scorn on the SWP’s ‘it would weaken imperialism’ claim.

“The SWP - in this instance, comrade Kier McKechnie - has picked up on a frankly idiotic line beloved of Scottish left nationalists, that a Scottish breakaway would be a blow to British imperialism: ‘Britain is a major imperialist power that still wants to be able to invade and rob other countries across the globe,’ he writes. ‘A clear ‘yes’ vote for independence would weaken the British state and undermine its ability to engage in future wars.’

As a factual statement, this is questionable (as a rule, no evidence is ever offered for it). Let us be blunt: it is not the pluckiness and military prowess, however impressive, of the Scots that allows Britain to do these things, but the technological and logistical largesse of the United States”.

But the Weekly Worker soon ends up on essentially the same ground: the discredited slogan of ‘national self-determination’.

“The only appropriate response to such a referendum is a spoilt ballot - combined with serious propaganda for a democratic federal republic in Britain, in which Scotland and Wales have full national rights, up to and including the right to secession. Our job is not to provide left cover for the break-up of existing states - no matter how far up the imperial food chain they are - but to build the unity of the workers’ movement across all borders, and fight to place the workers’ movement at the vanguard of the struggle for extreme, republican democracy”.

As Rosa Luxemburg pointed out in the early years of the 20th century, the idea of an abstract ‘right’ to national self-determination has nothing to do with marxism, because it obscures the reality that every nation is divided up into antagonistic social classes. And if the formation of certain independent nation states could be supported by the workers’ movement in a period when capitalism still had a progressive role to play, that period – as Luxemburg also showed – came to a definitive end with the First World War. The working class today no longer has any ‘democratic’ or ‘national’ tasks. Its sole future lies in the international class struggle not only across nation states but for their revolutionary destruction.

Amos 28/1/12

Recent and ongoing:

Rubric:

Class struggle the only alternative to austerity and massacres

- 1695 reads

In January a six day general strike in Nigeria was one of the most extensive social movements ever to hit the country. Only 7 million are in unions but up to 10 million took part in the strike, right across Nigeria, with demonstrations in every major city involving tens of thousands overall. The strike was part of a protest against the abolition of fuel subsidies which overnight doubled the cost of not only petrol but also had a similarly massive impact on food, heating and transportation costs. In a country with high unemployment (40% of under forties) and high poverty levels (70% existing on less than $2 a day) the outburst of anger was to be expected.

The major news outlets’ coverage of Nigeria recently has concentrated on the continuing terrorist campaign of Boko Haram, an Islamic fundamentalist group. Over the last two years they have killed more than a thousand people, and have stated their intention to continue the campaign, letting off bombs in crowded public places as well as attacking police stations. There has been a certain amount of sympathy with the latter actions as the Nigerian state rules with a very heavy hand. During the course of the strike, for example, the brutal intervention of the police and armed forces, often firing live ammunition at demonstrators, resulted in the deaths of more than 20, with more than 600 injured. Strictly enforced curfews are still in place in many parts of the country. In Kano, in the North, police helicopter gunships patrol during the day partly to monitor and partly to intimidate the population. Meanwhile in the last week of January nearly 200 people have died in a wave of bombings carried out by Boko Haram. It says that schools could be the next targets.

Despite its brutal nature – a spokesman recently announced that all those who do not follow its sharia law would be killed - Boko Haram has a certain amount of support in the Islamic and poorer North of Nigeria. In the North average annual income is about $718 whereas in the South the figure is $2010. However the violence of Boko Haram has to be seen in context. The general strike involved huge numbers of people from different religious and ethnic backgrounds. In a country with hundreds of languages/ethnic groups, breaking through the divisions to unite in a struggle is important. The fact that the unions called off demonstrations and then the strike so rapidly does not diminish the significance of what happened.

The general strike had been preceded by large scale protests in most of the country and showed the strength of solidarity that exists amongst workers. Nevertheless by focusing the struggle within the framework set out and led by the unions the workers were falling into a familiar trap. While the general strike was running the oil workers union did not participate, allowing Nigeria’s biggest industry to continue. The union leadership negotiated a deal with the government which they presented as a ‘victory’ for the workers when in reality the dampening of the movement was a victory for the bourgeoisie. The response to the deal was one of suspicion amongst large numbers of Nigerians. Many comments in the following days talked about the corruption of the trade union leaders and their collusion with the government.

The problem though lies at a deeper level than the corruption of the leadership. The fundamental requirement for the working class is to control its own struggles and develop its own political programme. This means that it has to organise outside the structures of the trade unions. It needs assemblies and elected committees to co-ordinate its struggle. Then there exists the possibility to extend struggles beyond sector, race and nationality.

The weight of democratic illusions

We come then to another problem: the democratic fantasy that dominates many of the movements that have appeared in the last few years, such as the Occupy Nigeria movement that sprang up after the fuel subsidy was cut.

The democratic capitalist state exists to make sure that capitalism is working in the national interest. This means in reality the general interest of the national bourgeoisie. Despite the ideal of free market capitalism the economy is incapable of functioning without this state as can be seen by the intervention following the crisis in 2008, and previously in the many laws, agreements and structures put in place nationally and internationally. The job of the state is also to defend the nation against its rivals and also to defend itself against the working class. To defend itself against the working class it absorbs all the traditional organisations of the working class, the unions and the traditional leftist parties that absorb the discontent of the working class and direct it into harmless activity.

The fantasy that exists is one where this state can be taken and moulded to the needs of all, rich and poor. One of the illusions is that because everyone can vote in the democratic system then, in theory, we all have an equal power in society. This is impossible because capitalism is based on an unequal social relationship. While we can vote for whichever candidate we like we cannot vote away capitalism. If capitalism is threatened the bourgeoisie is able to break with the niceties of elections and freedom of speech and use the full force of the state to violently repress the working class. History offers many examples

The unions are an integral part of the democratic apparatus used to keep the working class under control. In Nigeria it was clear what role the unions had played against the development of workers’ struggles. When radical ideas were increasingly being aired union leaders issued a statement which made a point of saying that the “objective is the reversal of the petrol prices to their pre-January 1, 2012 level. We are therefore not campaigning for ‘Regime Change’.” The Financial Times (16/1/12) spotted that the situation had changed in the aftermath of the strike as“the protests have emboldened ordinary Nigerians and raised new awareness of wasteful expenditure. In addition, many feel let down by the unions for agreeing to call off the strike without the subsidy being fully restored.” Disappointment in the unions, alongside an experience of repression from the state and a keen understanding of how little capitalism has to offer, are all factors that could contribute to the development of future workers’ struggles.

Gina 28/1/12

Geographical:

- Nigeria [19]

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [14]

- Fuel price protests [20]

Rubric:

Imperialist bloodletting worsens in Middle East

- 2087 reads

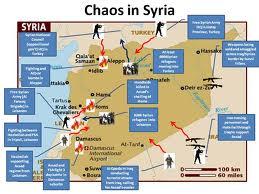

After a car bomb exploded in Damascus on 6 January the Syrian government rushed to blame it on al-Qaida. From the arrival of the Arab League mission on 26 December 2011 until an announcement from the UN on 10 January 2012, the number of deaths was running at forty a day. From the so-called ‘al-Qaida’ bomb alone 26 died and dozens were injured. As far as the Assad regime is concerned this is all acceptable in the attempt to hold onto office.

After counting more than 5400 deaths in the Syrian state repression that dates back to March 2011, the UN has given up trying to give figures as it can’t reliably monitor the extent of the crack-down. US President Obama has denounced the “unacceptable levels of violence”. Mind you, he was already saying that the “outrageous use of violence to quell protests must come to an end” last April. This is typical hypocrisy from the man who was authorising the bombing of targets in Pakistan within four days of being sworn in as President.

This is how the bourgeoisie operates. It uses brutal military force, as well as propaganda and diplomacy. Army deserters are massacred while Assad blames ‘foreign terrorists’, as he has throughout the last ten months. At the same time he has had no problem in accepting the backing of the Iranian government. Because of the Tehran-Damascus connection, Syrian oppositionists see Iranians as valid targets. Most recently eleven pilgrims were kidnapped on the road to Damascus; in December it was seven workers involved in building a power plant in central Syria.

The mission of the Arab League has achieved nothing. Its intention was to put pressure on Assad, but with little expected beyond some nominal reforms. Their plan for power to go to an interim government run by one of his deputies before eventually holding elections for a government of national unity was a compromise between very different approaches. Qatar has been very loyal to the US, proposing to send in Arab troops and accept US military aid. Egypt and Algeria have been resistant to any proposal that might affect the status quo.

As January drew to a close there was an escalation in government attacks, especially in the areas of Homs, Idlib, and Hama. Elsewhere, including in the suburbs of Damascus, there are increasing clashes between army deserters and the regime’s troops. The only foreseeable prospect for Syria is the continuation of violence, which any intervention from the United Nations can only exacerbate.

Undeclared war against Iran

If there were suspicions over the ‘al-Qaida’ bomb in Damascus there was little doubt about who was responsible for the bomb that killed an Iranian nuclear scientist in Tehran on 11 January. While the Iranian state inevitably blamed the CIA, experienced observers and those with sources in the Israeli state identified Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, as being behind the attack. It is the fourth murder of an Iranian nuclear scientist in the last two years.

The assassinations of scientists are part of a campaign to stop, or at least delay, Iran acquiring a nuclear weapons capability. In an undeclared war, using the many means at their proposals, nuclear powers such as the US, Britain and France are trying to prevent Iran joining their club, and undermine its position as a regional power.

The EU boycott of Iranian banking was a significant, but not a devastating attack on the Iranian economy. However, the EU embargo on Iranian oil sales - no new contracts, and the end of existing contracts by 1 July – is to be taken seriously. A measure of the seriousness of the measure was that, the day before the announcement, six warships from the US, France and Britain entered the Strait of Hormuz. A small fleet including a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, a frigate, a guided missile carrier and two destroyers, following on from a ten day US Navy exercise in the Strait either side of New Year, was there to back up the oil embargo. The Diplomatic Editor of the Guardian (23/1/12) said that this “sets a potential time bomb ticking”. This is because “Unlike previous sanctions on Iran, the oil embargo would hit almost all citizens and represent a threat to the regime. Tehran has long said such actions would represent a declaration of war, and there are legal experts in the west who agree”.

If Iran tries to close the Strait of Hormuz its opponents are prepared. A fifth of the world’s oil in transit passes through the Strait. There is a serious question as to whether the US would use force to keep it open. The US Fifth Fleet is in the Gulf. 15,000 of the US troops that were in Iraq are now based in Kuwait.

“The Iranian military looks puny by comparison, but it is powerful enough to do serious damage to commercial shipping. It has three Kilo-class Russian diesel submarines which run virtually silently and are thought to have the capacity to lay mines. And it has a large fleet of mini-submarines and thousands of small boats armed with anti-ship missiles which can pass undetected by ship-borne radar until very close. It also has a ‘martyrdom’ tradition that could provide willing suicide attackers.

The Fifth Fleet’s greatest concern is that such asymmetric warfare could be used to overpower the sophisticated defences of its ships, particularly in the narrow confines of the Hormuz strait, which is scattered with craggy cove-filled Iranian islands ideal for launching stealth attacks.

In 2002, the US military ran a $250m (£160m) exercise called Millennium Challenge, pitting the US against an unnamed rogue state with lots of small boats and willing martyr brigades. The rogue state won, or at least was winning when the Pentagon brass decided to shut the exercise down. At the time, it was presumed that the adversary was Iraq as war with Saddam Hussein was in the air. But the fighting style mirrored that of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

In the years since, much US naval planning has focused on how to counter ‘swarm tactics’ – attacks on US ships by scores of boats, hundreds of missiles, suicide bombers and mines, all at once” (op cit).

While “swarming” has been identified as a problem, “ultimately, the US response to swarming will be to use American dominance in the air and multitudes of precision-guided missiles to escalate rapidly and dramatically, wiping out every Iranian missile site, radar, military harbour and jetty on the coast. Almost certainly, the air strikes would also go after command posts and possibly nuclear sites too. There is little doubt of the effectiveness of such a strategy as a deterrent, but it also risks turning a naval skirmish into all-out war at short notice” (op cit).

These are the considerations of the military specialists of the ruling class. They consider every possibility because not every imperialism can draw on the same resources, but will do anything that it can to defend the national capital, regardless of human cost.

Not just sabre rattling

There are those who minimise the effects of war in the Middle East. For example, in a recent article in the New York Times (26/1/12) you can read that “Israeli intelligence estimates, backed by academic studies, have cast doubt on the widespread assumption that a military strike on Iranian nuclear facilities would set off a catastrophic set of events like a regional conflagration, widespread acts of terrorism and sky-high oil prices.

The estimates, which have been largely adopted by the country’s most senior officials, conclude that the threat of Iranian retaliation is partly bluff. They are playing an important role in Israel’s calculation of whether ultimately to strike Iran, or to try to persuade the United States to do so.”

These ‘calculations’ all sound very rational. The article continues “‘A war is no picnic,’ Defense Minister Ehud Barak told Israel Radio in November. But if Israel feels itself forced into action, the retaliation would be bearable, he said. ‘There will not be 100,000 dead or 10,000 dead or 1,000 dead. The state of Israel will not be destroyed.’”

In Iran they have also done their sums. They say they can cope with an oil embargo, as ‘only’ 18% of Iranian oil exports go to the EU, and what doesn’t go to Europe will go to China. In an act of defiance a new law is to be debated in the Iranian parliament that could halt oil exports almost immediately. This would have an immediate impact in Greece, Italy and Spain where they are still looking for alternative suppliers. Although, while it’s claimed that Iran could easily shut the Strait, the economic effects of a blockade would be likely to hurt Iran more than anyone else as, according to some sources, 87% of its imports and 99% of its exports are by sea.

In reality, not only is capitalism not rational, it has also shown its capacity to escalate conflicts from minor skirmishes into all-out war on numerous occasions. The Iranian military might be ‘puny’ but its forces have shown a capacity to intervene in a number of conflicts. Whether supporting the government in Syria, or oppositional forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, Iran seems never far away from the scenes of war. In the Guardian article cited above an Iranian journalist specialising in military and strategic issues is quoted: “I recall a famous Iranian idiom that was quite popular among the military officials: ‘If we drown, we’ll drown everyone with us’.” That applies to the capitalist ruling class in every country across the globe. This is not just at the level of the official military apparatus but in the desperate actions of terrorists. In Iraq, for example, following the US exodus, conflict continues, with suicide car bombs killing dozens in crowded locations on a regular basis. Whoever is behind them is not part of the resistance to capitalism but just adding to the precariousness of life in Baghdad and elsewhere. None of this behaviour is rational, but the bourgeoisie is not going without a fight, whether against other imperialisms or against its mortal enemy, the working class.

Car 28/1/12

Geographical:

Recent and ongoing:

Rubric:

Democratise capitalism or destroy it?

- 2614 reads

The slogan ‘democratise capitalism’ appeared on the side of the Tent City University at the St Paul’s occupation, provoking sharp debates which eventually led to the banner being taken down.

This outcome shows that the occupations at St Paul’s, UBS and elsewhere have provided a very fruitful space for discussion among all those who are dissatisfied with the present social system and are looking for an alternative. ‘Democratising capitalism’ is not a real option, but it does reflect the views of many people participating in the occupations and the meetings they have generated. Again and again, the idea is put forward that capitalism could be made more human if the rich were made to pay more taxes, if the bankers lost their bonuses, if the financial markets were better controlled, or if the state took a more direct hand in running the economy.

Even the top politicians are jumping on this bandwagon. Cameron wants to make capitalism more moral, Clegg wants the whole world to be like John Lewis, with workers owning more shares, Miliband is against ‘predatory’ capitalism and wants more state regulation.

But all this, coming from the politicians of capital, is empty chatter, a smokescreen to prevent us seeing what capitalism is not, and what it is.

Capitalism can’t be reduced to the ownership of wealth by private individuals. It is not simply about bankers or other wealthy elites getting too much reward for too little effort.

Capitalism is a whole stage in the history of human civilisation. It is the last in a series of societies based on the exploitation of the majority by a minority. It is the first human society in which all production is motivated by the need to realise a profit on the market. It is therefore the first class-divided society where all the exploited have to sell their capacity to work, their ‘labour power’, to the exploiters. So while in feudalism, the serfs were compelled by force to directly surrender their labour or their produce to the lords, under capitalism, our labour time is taken from us more subtly, through the wage system.

It therefore makes no difference if the exploiters are organised as private bosses or as ‘Communist Party’ officials like in China or North Korea. As long as you have wage labour, you have capitalism. As Marx put it: “capital presupposes wage labour. Wage labour presupposes capital” (Wage Labour and Capital).

Capital is, at its heart, the social relation between the class of wage labourers (which includes the unemployed, since unemployment is part of the condition of that class) and the exploiting class. Capital is the alienated wealth produced by the workers – a force created by them but which stands against them as an implacable enemy.

Capitalism is crisis

But while the capitalists benefit from this arrangement, they can’t really control it. Capital is an impersonal force which ultimately escapes and dominates them as well. This is why the history of capitalism is the history of economic crises. And since capitalism became a global system round the beginning of the 20th century, this crisis has been more or less permanent, whether it takes the forms of world wars or world depressions.

And no matter what economic policies the ruling class and its state tries out, whether Keynesianism, Stalinism, or state-backed ‘neo-liberalism’, this crisis has only got deeper and more insoluble. Driven to desperation by the impasse in the economy, the different factions of the ruling class, and the various national states through which they are organised, are caught in a spiral of ruthless competition, military conflict, and ecological devastation, forcing them to become less and less ‘moral’ and more and more ‘predatory’ in their hunt for profits and strategic advantages.

The capitalist class is the captain of a sinking ship. Never has the need to relieve it of its command of the planet been so pressing.

But this system, the most extreme point in man’s alienation, has also built up the possibility of a new and truly human society. It has set in motion sciences and technologies which could be transformed and used for the benefit of all. It has therefore made it possible for production to be geared directly for consumption, without the mediation of money or the market. It has unified the globe, or at least created the premises for its real unification. It has therefore made it feasible to abolish the whole system of nation states with their incessant wars. In sum, it has made the old dream of a world human community both necessary and possible. We call this society communism.

The exploited class, the class of wage labour, has no interest in falling for illusions about the system it is up against. It is potentially the gravedigger of this society and the builder of a new one. But to realise that potential, it has to be totally lucid about what it is fighting against and what it is fighting for. Ideas about reforming or ‘democratising’ capital are so many obstacles to this clarity.

Capitalism and democracy

Like making capitalism more human, everyone nowadays claims to be for democracy and wants society to be more democratic. And that is why we can’t take the idea of democracy at its face value, as some abstract ideal that we all can agree to. Like capitalism, democracy has a history. As a political system, democracy in ancient Athens could co-exist with slavery and the exclusion of women. Under capitalism, parliamentary democracy can coexist with the monopoly of power by a small minority which hogs not only the economic wealth but also the ideological tools to influence people’s thinking (and voting).

Capitalist democracy mirrors capitalist society, which turns all of us into isolated economic units competing on the market. In theory we all compete on equal terms, but the reality is that wealth gets concentrated into fewer and fewer hands. We are just as isolated when we enter the polling booths as individual citizens, and just as remote from exercising any real power.

In the debates that have animated the various occupation and public assembly movements from Tunisia and Egypt to Spain, Greece and the USA, there has been a more or less continuous confrontation between two wings: on the one hand, we have those who want to go no further than making the existing regime more democratic, to stop at the goal of getting rid of tyrants like Mubarak and bringing in a parliamentary system, or of putting pressure on the established political parties so that they pay more heed to the demands of the street. And, on the other hand, even if they are only a minority right now, we have those who are beginning to say: why do we need parliament if we can organise ourselves directly in assemblies? Can parliamentary elections change anything? Could we not use forms like assemblies to take control of our own lives – not just the public squares, but the fields, factories and workshops?

These debates are not new. They echo the ones which took place around the time of the Russian and German revolutions, at the end of the First World War. Millions were on the move against a capitalist system which had, by slaughtering millions of the battlefronts, already shown that it had ceased to play a useful role for the human race. But while some said that the revolutions should go no further than instituting a ‘bourgeois democratic’ regime, there were those – a very sizeable number at that time – who said: parliament belongs to the ruling class. We have formed our own assemblies, factory committees, soviets (organisations based on general assemblies with elected and revocable delegates). These organisations should take the power and then it can remain in our own hands – the first step towards reorganising society from top to bottom. And for a brief moment, before their revolution was destroyed by isolation, civil war and internal degeneration, the soviets, the organs of the working class, did take power in Russia.

That was a moment of unprecedented hope for humanity. The fact that it was defeated should not deter us: we have to learn from our defeats and from the mistakes of the past. We can’t democratise capitalism because more than ever it is a monstrous and destructive force which will drag the world to ruin unless we destroy it. And we can’t get rid of this monster using the institutions of capitalism itself. We need new organisations, organisations which we can control and direct towards the revolutionary change which remains our only real hope.

Amos 25/1/12

Recent and ongoing:

- Illusions in Democracy [24]

- discussion [25]

- Occupy London [26]

Rubric:

World Revolution no.352, March 2012

- 2011 reads

The deteriorating material situation of the working class

- 2086 reads

This is an extract from a text prepared for a recent internal meeting of the ICC’s section in Britain.

A range of official data allows us to see that the working class’ working and living conditions are under sustained attack.

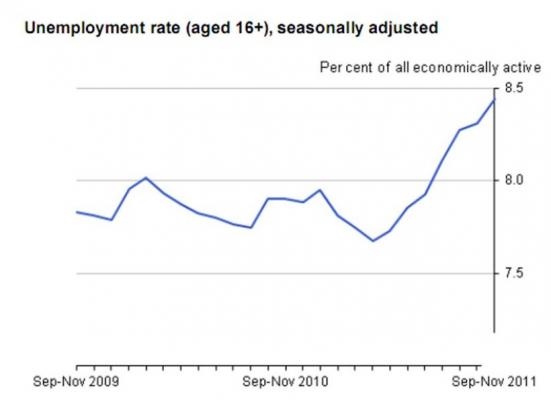

• Unemployment has continued to increase, reaching 8.4%, in the three months to November 2011, an increase of 0.3% over the preceding three months and of 0.5% compared to the same time a year ago. This amounts to 2.68 million people in total and to an increase of 118,000 compared to the previous quarter and of 189,000 compared to a year earlier. Of this total, 857,000 had been unemployed for over 12 months (a drop of 10,000 compared to the previous quarter but a rise of 25,000 compared to a year earlier) and 424,000 for over 24 months (up 1,000 on the previous quarter). Amongst 16 to 24 year olds the unemployment rate is 22.3%. Excluding young people in education (who are counted if they have been looking for work in the preceding 4 weeks), the total was 729,000, an increase of 8,000 over the previous quarter, making the rate of unemployment amongst young people not in education 20.7%.[1] Public sector employment fell by 67,000 in the third quarter of 2011.[2]

• The rate of redundancies has picked up over the last few months after falling back between November 2009 and November 2010. In the three months to November 2011 164,000 had become redundant (either voluntarily or enforced), an increase of 14,000 over the preceding quarter and of 5,000 compared to a year ago. The overall rate was 6.6 workers per thousand.[3]

• Growth in pay has slowed over the last few months falling to 1.9% in the three months to November 2011 from 2.8% in the previous quarter. The ONS offers an explanation: “This marked drop in earnings growth may reflect a number of pressures in the labour market: the desire by firms to reduce their costs in the face of weak demand; weak wage bargaining power of employees as a result of high unemployment and low employment levels; falling inflation that ease the decline in real wage growth and so reduce the pressure on employers to maintain wage growth; and falling demand and output.”[4] The same report goes on to note that the rate of increase in the public sector in the three months to November was 1.4% compared to 2.0% in the private sector, “This demonstrates the impact of the sustained public sector pay freeze. Both public sector and private sector wage growth are well below CPI inflation and so the sustained decline of real wages has continued.”[5] However, it is worth noting that overall cuts in pay were made much more rapidly in the private sector than the public sector – research by the IFS concluded that “it will take the whole of the two-year public pay freeze and two years of 1% pay increases to return public pay to where it was relative to private sector pay in 2008. This is because private sector pay reacted quickly to the recession. Pay in the public sector did not.”[6] This merely reflects the fact that the economic laws of capitalism take effect more rapidly in the private than the state sector.

• The average number of hours worked per week stood at 31.5 in the three months to November 2011, which is unchanged from the previous quarter. However, the total number of hours worked per week fell by 0.2 million to 916.3 million.[7]

• Labour productivity increased by 1.2% over the quarter to November 2011 while unit labour costs rose by 0.5%. However, this should be put in the context of falls in productivity compared to most major competitors during 2010.[8]

• The total amount of personal debt declined between December 2010 and 2011, falling from £1.454 trillion to £1.451 trillion. The majority of this borrowing is for mortgages, which increased from £1.238 trillion to £1.245 trillion. In contrast consumer credit fell from £216bn to £207bn. This suggests that workers are reducing spending or have less access to credit. Nonetheless, the average amount by owed adults in the UK stood at £29,547 in December 2011. This is about 122% of average earnings. The total owed is still more than the annual production of the country.[9]

• The impact of debt continues with 101 properties being repossessed every day in the last three months of 2011 and 331 people becoming insolvent. However, both figures have fallen since the previous quarter but in contrast it seems there has been a significant growth in the numbers using informal insolvency solutions while nearly a million “are struggling but have not sought help.”[10]

• Older people have seen the value of their pensions eroded by effective rates of inflation that are above the official figures with a third reporting they can only afford the basics, a quarter saying they buy less food, 14% reporting going to bed early to keep warm and 13% saying they only live in one room to cut down on costs.[11]

These figures show the efforts that workers are going to in order to get by: cutting down on spending in order the keep their homes; accepting reductions in pay in order to keep jobs, albeit with limited success. The lower than anticipated rate of repossessions and insolvencies and the apparent willingness of financial bodies to agree informal arrangements to manage debt suggest that the bourgeoisie is also trying to mitigate the impact of the crisis. This makes sense both economically (managing debt means it is more likely to be repaid) and politically. How long this can be maintained is uncertain given that the cuts are only in their first stage:

• “By the end of 2011–12, 73% of the planned tax increases will have been implemented. The spending cuts, however, are largely still to come – only 12% of the planned total cuts to public service spending, and just 6% of the cuts in current public service spending, will have been implemented by the end of this financial year. The impact of the remaining cuts to the services provided is difficult to predict; they are of a scale that has not been delivered in the UK since at least the Second World War. On the other hand, these cuts come after the largest sustained period of increases in public service spending since the Second World War. If implemented, the planned cuts would, by 2016/17, take public service spending back to its 2004/05 real-terms level and to its 2000/01 level as a proportion of national income.”[12]

• “The planned cuts to spending on public services are large by historical standards… If the current plans are delivered, spending on public services will (in real terms) be cut for seven years in a row. The UK has never previously cut this measure of spending for more than two years in a row… if delivered, the government’s plans would be the tightest seven-year period for spending on public services since the Second World War: over the seven years from April 2010 to March 2017, there would be a cumulative real-terms cut of 16.2%, which is considerably greater than the previous largest cut (8.7%), which was achieved over the period from April 1975 to March 1982.”[13] The report by the IFS goes on to note that no country has ever cut spending at the level proposed for the number of years proposed.[14] It should be noted that all of these predictions are based on the assumption that the economy will pick up in the years ahead.

• People retiring in the year ahead expect to have an annual income of £15,500, which is 6% less than those who retired in 2011, and 16% less than those who retired in 2008. One fifth expect an annual income of £10,000 while 18% of those retiring expect to do so with debts averaging £38,200. The ending of final salary pension schemes in the private and public sectors (this is likely to be the reality of any deal stitched by the unions and bosses to resolve the current confrontation) will see far more workers living in poverty in their old age.[15]

• Levels of child poverty are predicted to return almost to the level seen in the late 1990s when the Labour government began efforts to reduce it. By 2020/21 4.2m children are forecast to be living in poverty, compared to 4.4m in 1998/9.[16]

• “The Office for Budget Responsibility’s November 2011 forecast for general Government Employment estimates a total reduction of around 710,000 staff between Q1 2011 and Q1 2017.”[17] North 08/02/12

[1]. ONS “Labour Market Statistics” January 2012

[2]. Credit Action, “Debt statistics”, February 2012.

[3]. ONS “Labour Market Statistics” January 2012

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. Ibid

[6]. Institute for Fiscal Studies, Press Release 31/01/12: “Latest public pensions reforms unlikely to save money over longer term; four year pay squeeze returns public/private differential to pre-recession level”.

[7]. ONS “Labour Market Statistics” January 2012

[8]. ONS “International comparisons of productivity – First estimates for 2010”. Interestingly, this report states that between 1991 and 2004 the UK experienced the fastest growth rates of all G7 countries.

[9]. Credit Action, “Debt statistics”, February 2012.

[10]. Ibid.

[11]. Ibid, citing research by Age UK.

[12]. Institute for Fiscal Studies, “Green Budget 2012”