International Review 2000s : 100 - 139

- 17300 reads

Site structure:

2000 - 100 to 103

- 6520 reads

International Review no.100 - 1st quarter 2000

- 3793 reads

100 issues of the International Review

- 3504 reads

In the final analysis, however, the most important thing about the International Review is not so much its regularity nor its internationally centralised character, but its capacity to act as an instrument of theoretical clarification. "The Review will be above all the expression of the theoretical endeavours of our Current, since only this theoretical endeavour, based on a coherence of political positions and orientation, can serve as the basis for the regroupment and real intervention of revolutionaries" (Preface to the first issue of the International Review, April 1975). Marxism, as the theoretical viewpoint of the revolutionary class, is the most advanced point of human thinking about social reality. But as Marx insisted in Theses on Feuerbach, the truth of a method of thought can only be tested in practice; marxism has demonstrated its superiority over all other social theories by being able to offer a global understanding of the movement of human history and to predict the broad lines of its future evolution. But it is not enough to claim to be marxist to really assimilate this method, to bring it alive and apply it correctly. If we feel that we have succeeded in doing so during the last three decades of accelerating history, it is not because we think such an ability has been granted to us by divine right, but because we feel that we have taken our inspiration throughout this period from the best traditions of the international Communist Left. At least, this has been one of our constant objectives. And in making this claim, we can offer no better supporting evidence than the body of work contained in the 600-odd articles of 100 issues of the International Review.

Continuity, enrichment, and debate

Marxism is a living historical tradition. On the one hand this means that it is deeply aware of the necessity to approach all the problems it confronts from a historical starting point; to see them not as entirely �new� but as products of a long historical process. Above all, it recognises the essential continuity of revolutionary thought, the need to build on the solid foundations of previous revolutionary minorities. For example, in the 1920s and 30s the Italian left fraction, which published the review Bilan during the 1930s, was faced with the absolute necessity to understand the nature of the counter-revolutionary regime that had arisen in Russia. But it rejected any precipitous conclusions, especially those which, while in hindsight developing quicker than the Italian left a correct characterisation of the Stalinist power (ie that it was a form of state capitalism), only did so at the price of casting aside the whole experience of Bolshevism and the October insurrection as being �bourgeois� from the beginning. There was absolutely no question of Bilan calling into question its own continuity with the revolutionary energy that the Bolshevik party, the soviet power, and the Communist International had once embodied.

This capacity to maintain or restore the links with the past revolutionary movement was especially important in the proletarian milieu which emerged out of the resurgence of class struggle at the end of the 1960s, a milieu largely made up of new groups which had lost organisational and even political links to the previous generation of revolutionaries. Many of these groups fell prey to the illusion that they had come from nowhere, remaining profoundly ignorant of the contributions of this past generation, which had been almost obliterated by the counter-revolution. In the case of those influenced by councilist and modernist ideas, the �old workers� movement� was indeed something that had to be left behind at all costs; in fact, this was a theoretical apology for a break that had actually been imposed by the class enemy. Lacking any anchor in the past, the great majority of these groups soon found that they had no future either, and disappeared. It is therefore not surprising that today�s revolutionary milieu is almost entirely made up of groups which have in one way or another descended from the left current which was clearest in its understanding of this question of historical continuity - the Italian fraction. We should add that the historical anchor is today more important than ever, faced as we are with the culture of capitalist decomposition, a culture which more than ever before seeks to erase the historical memory of the working class and which, itself lacking any sense of the future, can only attempt to imprison consciousness in a narrow immediacy in which novelty is the only virtue.

On the other hand, marxism is not merely the perpetuation of a tradition; it is geared towards the future, towards the final goal of communism, and therefore must always renew its capacities to grasp the direction of the real movement, of the ever-shifting present. Inment, of the ever-shifting present. In the 1950s the Bordigist offshoot of the Italian left tried to take refuge from the counter-revolution by inventing the notion of �invariance�, opposing all attempts to enrich the communist programme. But this approach was very far from the spirit of Bilan which, while never breaking the link with the revolutionary past, insisted on the necessity to examine new situations "without any taboos or ostracism", without fear of breaking new programmatic ground. In particular, the fraction was not afraid to question the theses even of the Second Congress of the Communist International, something which latter day �Bordigism� has been incapable of doing. In the 1930s Bilan was faced with the new situation created by the defeat of the world revolution; the ICC has been compelled to analyse the equally new conditions created first by the end of the counter-revolution in the late 60s, and more recently, by the period inaugurated by the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Faced with such changing circumstances, marxists cannot limit themselves to the repetition of tried and trusted formulae, but have to submit their hypotheses to constant practical verification. This means that marxism, as with any branch of the scientific project, is in fact constantly enriching itself.

At the same time marxism is not a form of academic knowledge, of learning for the sake of learning; it is forged in unrelenting combat against the dominant ideology. Communist theory is by definition a polemical and combative form of knowledge; its aim is to advance proletarian class consciousness through exposing and expelling the influences of bourgeois mystifications, whether these mystifications appear in their grossest form within the broad mass of the class, or in a more subtle guise in the ranks of the proletarian vanguard itself. It is therefore a central task of any serious communist organisation to carry out a constant critique of the confusions that can develop in other revolutionary groups and within its own ranks. Clarity can never be advanced by avoiding debate and confrontation, even if this is all too often the case in today�s proletarian political milieu, which has lost its grip on the traditions of the past - the tradition defended by Lenin, who never shirked from any polemic whether with the bourgeoisie, confused groupings within the worker�s movement, or his own revolutionary comrades; the tradition defended as well by Bilan which, in its quest to elaborate the communist programme in the wake of past defeats, engaged in debate with all the different currents within the international proletarian movement of the day (the groups coming from the International Left Opposition, from the Dutch and German lefts, n, from the Dutch and German lefts, etc etc).

In this article we cannot attempt a complete survey of all the texts that have appeared in the International Review, although we do intend to publish a complete list of contents on our web site. What we will try to show is how the International Review has been the main focus of our effort to carry out these three key aspects of marxism�s theoretical struggle.

Reconstructing the proletariat�s revolutionary past

Given the endless campaigns of defamation against the memory of the Russian revolution, and the efforts of bourgeois historians to conceal the international scope of the revolutionary wave launched by the October insurrection, a large amount of space in our Review has necessarily been given over to reconstructing the real story of these events, to affirming and defending the proletariat�s experience against the bourgeoisie�s outright lies and lies-by-omission, and to drawing their authentic lessons against both the distortions of the left wing of capital and the erroneous conclusions drawn within the revolutionary movement today.

To cite the major examples: International Review 3 contained an article elaborating the framework for understanding the degeneration of the Russian revolution, in response to confusions within the proletarian milieu of the time (in this case the Revolutionary Workers Group from the USA); it also contained a long study of the lessons of the Kronstadt uprising, that key moment in the revolution�s decline. International Review nos. 12 and 13 contained articles re-affirming the proletarian character of the Bolshevik party and the October insurrection against the semi-Menshevik ideas of councilism; these articles originated in a debate in the group that most directly prefigured the ICC - the Internacialismo group in Venezuela in the 1960s, and have been republished as a pamphlet 1917, start of the world revolution. Following the collapse of the Stalinist regimes, we published in International Review nos. 71, 72 and 75 a series of articles in response to the vast torrent of propaganda about the death of communism, focusing in particular on refuting the fable about October being no more than a coup d�Etat by the Bolsheviks, and showing in some detail how it was above all the isolation of the Russian bastion that led to its demise. We took these themes further in 1997 with another series which looked more closely at the most important moments between February and October 1917 (see International Review nos. 89, 90, 91). From the beginning the ICC�s position was one of militant defence of the Russian revolution, but there is no doubt that as the ICC matured it progressively threw off the councilist influences that had been strongly present at its birth, and lost any apologetic note in its approach to the question of the party or of seminal historical figures like Lenin and Trotsky.

The International Review also contained an examination of the lessons of the German revolution in one of its first issues (no. 2) and a further two articles on the 70th anniversary of this crucial event which has been so carefully obscured by bourgeois historiography (International Review nos. 55 and 56). But we returned to the German revolution in much more depth in our series published in International Review nos. 81-83, 85, 88-90, 93, 95, 97-99). Here again we can see a definite maturation in the ICC�s approach to its subject, one more critical of the political and organisational lacunae of the German communist movement and based on a more profound understanding of the question of building the revolutionary party. A number of articles have also dealt with the 1917-23 revolutionary wave in a more general sense, notably the articles on Zimmerwald in International Review 44, on the formation of the Communist International in no. 57, on the extent and signif in no. 57, on the extent and significance of the revolutionary wave in no. 80, on the ending of the war by the proletariat, in no. 96.

Other key events in the history of the workers� movement have also been allotted particular articles in the International Review: the Italian revolution (no. 2); Spain 1936, especially the role of anarchism and of the �collectives� (no.15, 22, 47, etc); the struggles in Italy in 1943 (no.75) and more generally, articles denouncing the crimes of the �democracies� during the Second World War (no. 66, 79, 83,); a series on class struggle in the Eastern Bloc which deals with the massive class movements in 1953, 1956, and 1970 (no. 27, 28, 29); a series on China which exposes the mythology of Maoism (81,84, 94, 96); reflections on the meaning of the events in France in May 1968 (14, 53, 74, 93, etc ), and so on.

Closely tied to these studies has been the constant effort to recover the almost lost history of the communist left within these gargantuan episodes, a reflection of our understanding that without this history we could not have come into being. This effort has taken the form both of republishing rare texts, often translated for the first time into other languages, and of developing our own research into the positions and evolution of the left currents. We can mention the following studies, although again the list is not complete: of the Russian communist left, whose history is evidently directly linked to the problem of the degeneration of the Russian revolution (International Review nos. 8 and 9); of the German left (series on the German revolution, already mentioned; republication of texts of the KAPD - Theses on the Party in International Review 41 and its programme in International Review 94); of the Dutch left, with a long series (nos. 45-50, 52) which was the basis for the book which has appeared in French, Spanish and Italian and will shortly come out in English; of the Italian left fraction, particularly through the republication of texts on the Spanish civil war (International Review nos. 4, 6 and 7), fascism (no. 71), and the Popular Front (no. 47); of the French communist left in the 1940s through the republication of its articles and manifestos against the Second World War (nos. 79 and 88), its numerous polemics with the Partito Comunista Internazionalista (nos. 33, 34, 36), its texts on state capitalism and the organisation of capitalism in its decadent phase (nos. 21, 61), and its critique of Pannekoek�s book Lenin as Philosopher (nos. 27, 28, 30); of the Mexican left (texts from the 1930s on Spain, China, nationalisations in IRs 19 and 20), the �Greek left� around Stinas (no. 72).

Also inseparable from this work of historical reconstruction has been the energy put into texts which seek to elaborate our position on the fundamental class positions which derive both from the raw experience of the class combat and from the theoretical interpretation of this experience of the communist organisations. In this context, we should cite issues such as:

- the period of transition, in particular the lessons to be drawn from the Russian experience about the relationship between the proletariat and the transitional state. This was a major debate in the proletarian milieu at the time of the foundation of the ICC, a fact reflected in the publication of a number of discussion texts from different groups in the very first issue of the International Review. This debate continued within the ICC and a number of texts for and against the position of the majority position within the ICC were published (eg nos. 6, 11, 15, 18);

- the national question: a suite of articles examining the way this question was posed in the workers� movement in the first two decades of the 20th century was published in International Review nos. 37 and 42. A second series appeared in nos. 66, 68 and 69, covering a broader sweep from the revolutionary wave to the fate of �national� struggles in the phase of capitalist decomposition;

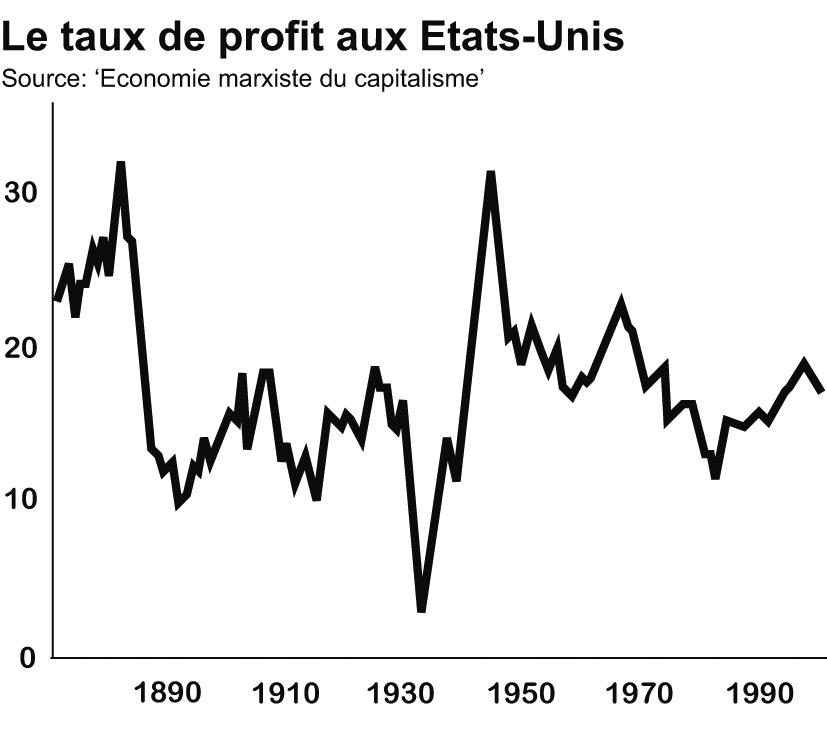

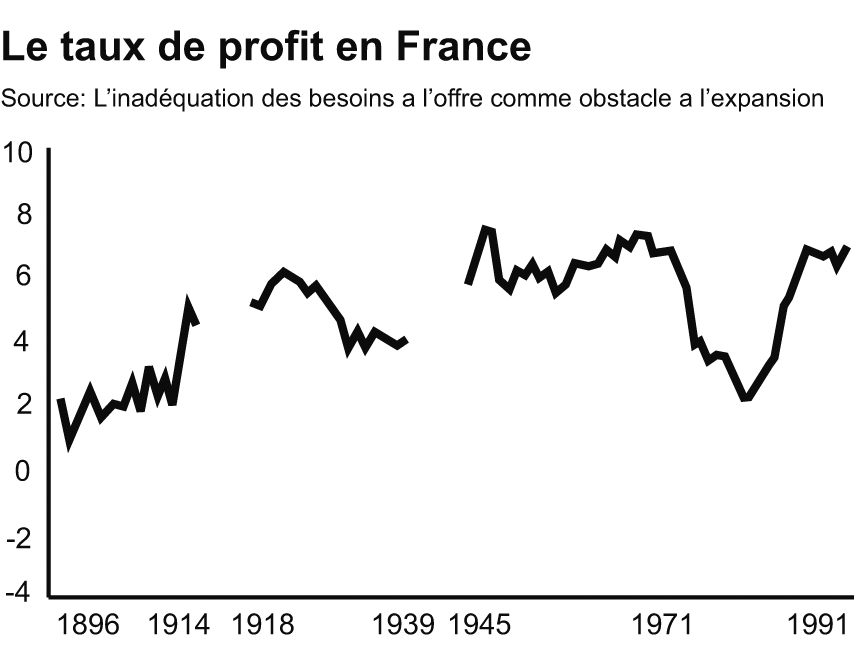

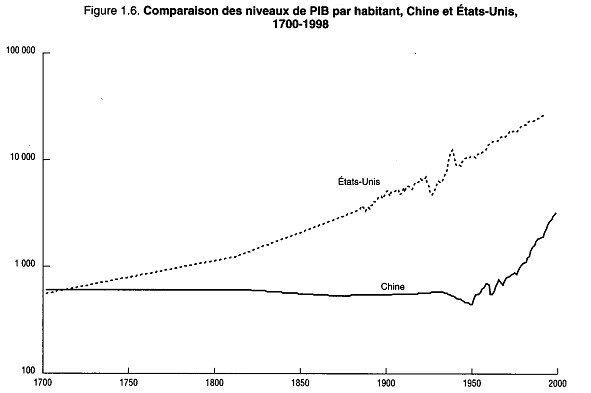

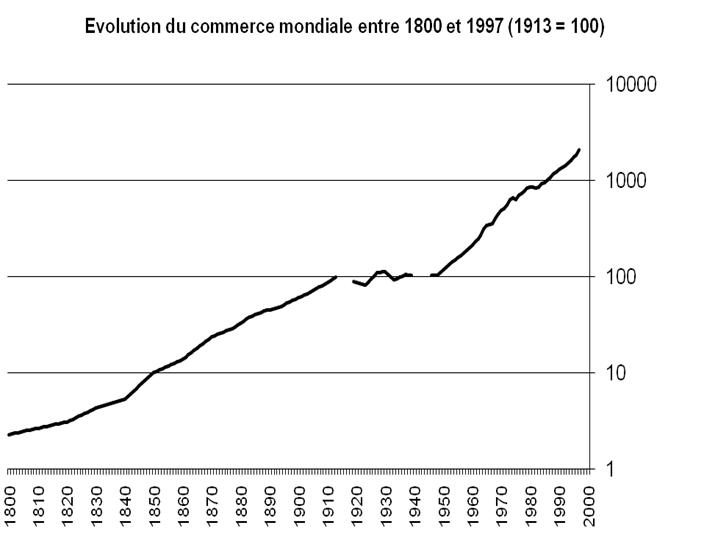

- the economic foundations of imperialism and of capitalist decadence. In a number of texts, in response to the criticism of other proletarian groups, we have argued for the essential continuity between Marx�s theory of crisis and the analyses developed by Rosa Luxemburg in her Accumulation of Capital and other texts (see for example nos. 13, 19, 16, 22, 29, 30). Parallel to this we have devoted a whole series to defending the basic concept of capitalist decadence against a number of its �radical� detractors in the parasitic camp and elsewhere (nos. 48, 49, 54, 55, 56, 58, 60);

- other such general issues we have covered include the union question in the Communist International (nos. 24 and 25); the peasant question (no. 24); the theory of the labour aristocracy (no.25 ); the capitalist threat to the natural environment, ie �ecology� (no 63); terror, terrorism and class violence, the latter also being the fruit of an important debate within the ICC, in particular over whether the petty bourgeoisie could have any political expressions in the period of decadence. The ICC in the period of decadence. The ICC�s distinction between state terror and petty bourgeois terrorism, and between both and proletarian class violence amply answered this question (nos. 14 and 15).

This is perhaps the most suitable place to refer to the series on communism which has been running regularly in the International Review since 1992 and still has quite along way to go. Originally this project was conceived as a series of four or five articles clarifying the real meaning of communism in response to the bourgeoisie�s lying equation between Stalinism and communism. But in seeking to apply the historical method as rigorously as possible, the series grew into a deeper re-examination of the evolving biography of the communist programme, its progressive enrichment through the key experiences of the class as a whole and the contributions and debates of the revolutionary minorities. Although the majority of articles in the series are necessarily concerned with fundamentally political questions, since the first step towards the creation of communism is the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, it is also a premise of the series that communism will take humanity beyond the realm of politics and release his true social nature. The series thus poses the problem of marxist anthropology. The interweaving of the �political� and �anthroaving of the �political� and �anthropological� dimensions of the series has in fact been one of its leitmotifs. The first volume of the series began (from International Review 68) with the precursors of marxism and with the young Marx�s grandiose vision of the ultimate goals of communism; it ended on the eve of the mass strikes of 1905 which signalled that capitalism was moving into a new epoch where the communist revolution had graduated from being a global perspective of the workers� movement to placing itself urgently on the agenda of history (International Review 88). The second volume has so far largely focussed on the debates and programmatic documents emanating from the great revolutionary wave of 1917-23; it still has to traverse the years of counter-revolution, the revival of debate about communism in the period after 1968, and to clarify the framework for a discussion about the conditions of tomorrow�s revolution. But in the end it will have to return to the question of what the species will be in the future realm of freedom.

Another very important component of the Review�s effort to give greater historical depth to the class positions defended by revolutionaries has been its constant commitment to clarifying the question of organisation. This has certainly been the most difficult question of all for the generation of revolutionaries that emerged in the late 60s, above all because of the trauma of the Stalinist counter-revolution and the powerful influence of individualist, anarchist and councilist attitudes on this generation. Later on we will mention some of the many polemics the ICC has had with other groups of the proletarian milieu on this question, but it is also the case that some of the most important texts in the Review on matters of organisation are the direct product of debates within the ICC itself, of the often very painful combat the ICC has had to wage within its own ranks to fully reappropriate the marxist conception of the revolutionary organisation. Since the beginning of the 80s the ICC has passed through three major internal crises, each one of which has resulted in splits or departures but through which the ICC has also emerged strengthened politically and organisationally. To support this conclusion we can point to the quality of the articles which emerged from these struggles and encapsulated the ICC�s improved grasp of the organisation question. Thus in response to the split with the Chenier tendency in the early 80s we published two major texts � one on the role of the revolutionary organisation within the class (no. 29), the other on its internal mode of functioning (no. 33). The latter in particular was and remains a key text, since the Chenier tendency had threatened to throw overboard all the basic conceptions contained in our statutes, our internal �rules� of functioning. The text in International Review 33 was a clear restatement and elaboration of those conceptions (here we should also point to a much earlier text on the statutes, in International Review 5). In the mid 80s, the ICC took a further step in settling scores with the remaining anti-organisational and councilist influences in its midst, through the debate with the tendency which went on to form the �External Fraction of the ICC�, now �Internationalist Perspective�, a typical element of the parasitic milieu. The main texts published in the International Review around this debate illustrate its key issues: the assessment of the danger posed by councilist ideas to the revolutionary camp today (nos. 40-43); the question of opportunism and centrism in the workers movement (nos. 43 and 44). Through this debate � and through working out its ramifications for our intervention in the class struggle � the ICC definitely adopted the notion of the revolutionary organisation as an organisation of combat, of militant political leadership within the class. The third debate, in the mid 90s, returned to the question of functioning on a higher level, and reflected the determination of the ICC to confront all the vestiges of the circle spirit which had presided over its birth � to aff had presided over its birth � to affirm the open, centralised, method of functioning, based on statutes accepted by all, against anarchist practices founded on friendship networks and clannish intrigues. Here again a number of texts of real quality express our efforts to re-establish and deepen the marxist position on internal functioning: in particular, the series of texts dealing with the struggle between marxism and Bakuninism in the First International (84, 85, 87, 88) and the two articles �Have we become Leninists?� in nos. 96 and 97.

Analysing the real movement

The second key task outlined at the beginning of this article � the constant evaluation of a constantly changing world situation � has also been a central element of the International Review.

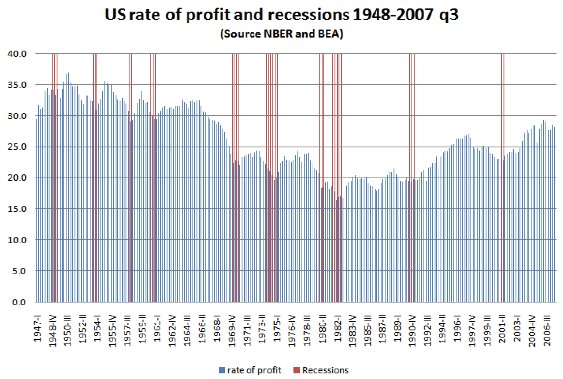

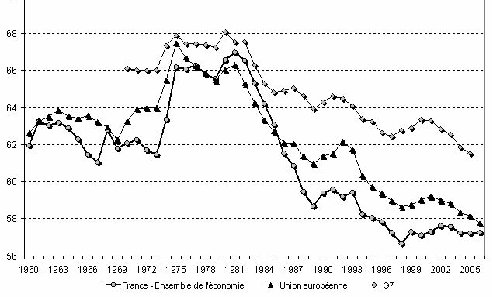

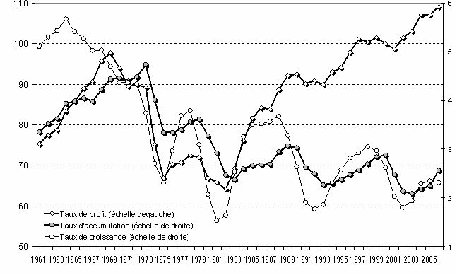

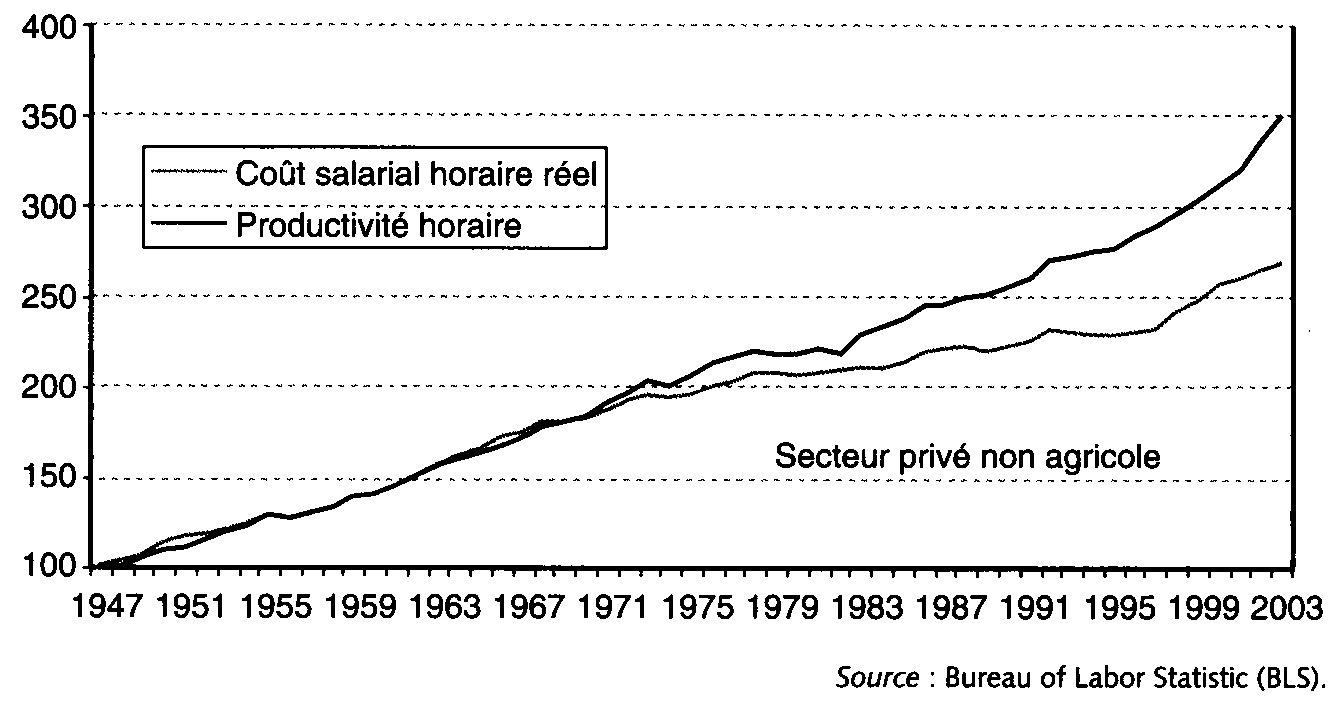

Almost without exception, every issue of the Review begins with an editorial on the major events of international situation. These articles represent the ICC�s overall orientation on these events, guiding and centralising the positions adopted in our territorial publications. By going back through these editorials, it is possible to acquire a succinct picture of the ICC�s response to all the most crucial events of the 70s, 80s and 90s: the second and third waves of international class struggle; the offensive of US imperialism in the 1980s, the wars in the Middle East, the Gulf, Africa, the Balkans; the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the onset of the period of capitalist decomposition; the difficulties of the class struggle faced with this new period, and so on. A parallel feature has been the regular slot given over to the question �what point has the crisis reached?�, which again makes it possible to review the most important trends and moments in capitalism�s long descent into the quagmire of its own contradictions. In addition to this quarterly assessment, we have also published texts which take a longer term view of the development of the crisis since it came out into the open at the end of the 60s, most notably our recent series �30 years of open crisis� (International Review nos. 96-98). More long term analyses of all the aspects of the international situation are also contained in the reports and resolutions of our bi-annual international congresses, which are always published as fully as possible in the International Review (see nos. 8, 11, 18, 26, 35, 44, 51, 59, 67, 74, 82, 90, 92, 97, 98).

In fact, it is not possible to make a rigid separation between texts analysing the current situation and historical-theoretical articles. The effort of analysis inevitably stimulates reflection and debate which in turn give rise to major orientation texts defining the overall dynamic of the period and clarifying certain fundamental concepts. These texts are also often the product of international congresses or meetings of the ICC�s central organ.

For example, the third congress of the ICC, in 1979, adopted such orientation texts on the course of history and on the shift of the left parties of capital into an oppositional stance, providing the basic framework for understanding the balance of class forces in the period opened up by the resurgence of class struggle in 1968, and the bourgeoisie�s primary political response to the class struggle in the 70s and 80s (see International Review 18). Further elucidation of how the ruling class manipulates the election process to suit its own needs was provided by the article on the �machiavellianism� of the bourgeoisie in International Review 31 and in international correspondence on the same question in no. 39. Likewise, the bourgeoisie�s more recent return to the strategy of placing the left parties in government has also been analysed in a text of the ICC�s 13th Congress and published in International Review 98.

The 4th congress � held in 1981, in the wake of the mass strike in Poland � adopted a text on the conditions for the generalisation of the class struggle, stressing in particular that the spread of mass strikes towards the centres of world capital would be a response to capitalist economic crisis rather than to capitalist world war; a further contribution attempted a historical overview of the development of the class struggle since 1968 (International Review 26). Debates about Poland, and indeed about the whole second international wave of struggles of which it was the culminating point, gave rise to a number of other important texts on the characteristics of the mass strike (no.27), on the critique of the theory of the weak link (nos. 31, 37), on the significance of the struggles of the French steelworkers in 1979 and of the ICC�s intervention within them (nos. 17, 20), on workers� struggle groups (no. 21), the struggles of the unemployed (no. 14) and so on. Particularly important was the text 'The proletarian struggle in decadent capitalism' (International Review 23), which aimed to demonstrate why the methods of struggle that had been appropriate in the ascendant period (trade union strikes in single sectors, financial solidarity, etc), had to be superseded in the decadent epoch by the methods of the mass strike. The continual effort to follow and provide a perspective for the international class movement continued in numerous articles written during the third wave of struggles between 1983 and 1988.

In 1989, another major historical shift took place in the international situation: the collapse of the Eastern imperialist bloc and the definitive opening of capitalism�s phase of decomposition, an exacerbation of all the features of a decadent system marked in particular by the growing war of each against all at the imperialist level. Although the ICC had not previously expected this �peaceful� collapse of the Russian bloc, it was quick to see which way the wind was blowing and was already armed with the theoretical framework to explain why Stalinism could not reform itself (see the articles on the economic crisis in the Russian bloc - International Review nos. 22, 23, 43 - and in particular the theses on �The international dimension of the workers� struggles in Poland� in International Review 24). This framework formed the basis of the orientation text �On the economic and political crisis in the eastern countries� in International Review 60, which predicted the final demise of the bloc well before it was consummated by the fall of the Berlin wall and the break up of the USSR. Equally important as guides to understanding the characteristics of the new period were the theses entitled �Decomposition, final phase of the decadence of capitalism� in International Review 62 and the article �Militarism and Decomposition� in International Review 64. This latter text took further and made more precise our articles �War, militarism and imperialist blocs� which we had published in International Review nos. 52 and 53, prior to the collapse of the Russian bloc, and which developed the notion of the irrationality of war in capitalist decadence. Through these contributions it became possible to advance the framework for understanding the sharpening of imperialist antagonisms in a world without the discipline of blocs. The very palpable sharpening of inter-imperialist conflicts, of the chaotic struggle of each against all during this decade, has fully confirmed the framework developed in these texts.

Defending the principle of open debate between revolutionaries

At a recent public forum organised by the Communist Workers� Organisation in London, referring to the ICC�s appeal for common action between revolutionary groups faced with the war in the Balkans, a comrade of the CWO posed the question "what is the ICC up to?". He suggested that "the ICC has made more turns than the Stalinist Comintern" and that its �friendly� approach to the milieu is just the latest one of many. The Bordigist group Le Prolétaire described the ICC�s appeal in similar terms, denouncing it as a "manoeuvre" (see RI�.).

Such accusations make one seriously doubt whether these comrades have followed the ICC press over the last 25 years. A brief flick through the 100 issues of the International Review would be enough to refute the idea that calling for unity between revolutionaries is a �new turn� by the ICC. As we have already said, for us the real spirit of the communist left, and of the Italian fraction in particular, is the spirit of serious political debate and confrontation between all the different forces within the communist camp, and indeed between the communists and those who are struggling to reach the proletarian political terrain. From its inception - and in opposition to the very widespread sectarianism that prevailed in the milieu as a direct result of the pressures of the counter-revolution - the ICC has insisted on:

- the existence of a proletarian political camp made up of different tendencies which in one way or another are expressions of the class consciousness of the proletariat;

- the central importance, within this camp, of those groups which derive from the historic currents of the communist left;

- the necessity for the unity and solidarity between revolutionary groups in the face of the class enemy - its anticommunist campaigns, its repression, its wars;

- the necessity for a serious and responsible debate about the real divergences between these revolutionary organisations;

- the ultimate necessity for the regroupment of revolutionary forces as part of the process leading to the formation of the world party.

In defending these principles, there have been times when it was more necessary to confront differences, other times when unity of action was paramount, but this has never called any of the basic principles into question. We also recognise that the weight of sectarianism affects the whole milieu and we do not claim to be entirely immune from it - even if we are better placed to fight it by the mere fact that we recognise its existence, in contrast to most other groups. In any case, there have been occasions when our own arguments have been weakened by sectarian exaggerations: for example, an article published in both World Revolution and Révolution Internationale carried the title �The CWO falls victim to political parasitism�, which could imply that the CWO has actually passed into the parasitic camp and thus outside the proletarian milieu, whereas in fact the article was fundamentally motivated by the need to warn a fellow communist group of the dangers of parasitism. In a similar way the title of the article we published on the formation of the IBRP in 1985 - �The constitution of the IBRP, an opportunist bluff� (International Review 40 and 41) - could imply that this organisation has entirely succumbed to the virus of opportunism, whereas in fact we have always considered its component groups to be an integral part of the communist camp, even if we have always strongly criticised what we frankly see as its opportunist errors.

From the earliest issues of the International Review, it is easy to see to what our real attitude has been:

- the first issue contained discussion articles on the period of transition, reflecting the discussion both between the groups that formed the ICC and others who remained outside it; the same International Review also points out that some of these groups had been invited to or took part in the founding conference of the ICC; moreover the practice of publishing in the International Review contributions from other groups and elements has continued ever since (cf texts of the CWO, of the Mexican group the GPI; of the Argentinian group Emancipacion Obrera; of individual elements in Hong Kong, Russia, etc);

- in International Review 11 we published a text voted by our second congress in 1977, defining the basic contours of the proletarian political milieu and the �swamp� and outlining our general policy towards other proletarian organisations and elements;

- in the late 70s we gave our wholehearted support to Battaglia Comunista�s proposal for an international conference between groups of the communist left, participated fully in all the conferences that followed, published their proceedings and articles about them in the International Review and, within the context of the conferences, defended the need for the groups involved to make common statements on the central issues of the day (such as the Russian invasion of Afghanistan). By the same token we severely criticised the decision of Battaglia to abort these conferences (See International Review nos. 10, 16. 17, 22) and also the two pamphlets �Texts and proceedings of the international conferences of the communist left�;

- in the early 80s we published a number of articles analysing the crisis which hit a number of groups within the proletarian milieu (International Review nos. 29, 31);

- International Review 35 contains the appeal to proletarian groups launched by our 5th international congress in 1983. This appeal does not propose the immediate re-convocation of international conferences but seeks to establish more �modest� practices such as attendance at the public meetings of other groups, more serious polemics in the press, etc;

- in International Review 46, towards the end of 1986, we express our support for the �international proposal� issued by the Argentine group Emancipacion Obrera in favour of greater co-operation and more organised discussion between revolutionary groups

- in International Review 67 we published a further appeal to the proletarian milieu, this time issued by our 9th congress in 1991.

Thus, the ICC�s policy since 1996 of1>Thus, the ICC�s policy since 1996 of calling for a common response to such events as the bourgeoisie�s campaigns against the communist left, or the war in the Balkans, by no means represents a new turn or some underhand manoeuvre but is fully consistent with our whole approach towards the proletarian milieu since before the ICC was formed.

The numerous polemics we have published in the International Review are equally part of this orientation. We cannot list them all here, but we can say that through the International Review we have carried on a continuous debate on virtually every aspect of the revolutionary programme with all the currents of the proletarian milieu and quite a few on its margins.

Debates with the IBRP (Battaglia and the CWO) have certainly been the most numerous, indicating the seriousness with which we have always taken this current. Some examples:

- on the party: the problem of substitutionism (International Review 17); the subterranean maturation of consciousness (International Review 43); the relationship between the fraction and the party (nos. 60, 61, 64, 65);

- on the history of the Italian left and the orin the history of the Italian left and the origins of the Partito Comunista Internazionalista (nos. 8, 34, 39, 90, 91);

- on the tasks of revolutionaries in the peripheries of capitalism (no. 46, and this issue);

- on the union question (no. 51);

- on the historic course (nos. 36, 50, 89);

- on crisis theory and imperialism (nos. 13, 19, 86 etc);

- on the nature of wars in decadence (nos. 79, 82);

- on the period of transition (no. 47)

- on idealism and the marxist method (no 99).

With the Bordigists, we have debated above all the question of the party (eg nos. 14, 23), but also the national question (no. 32), decaarty (eg nos. 14, 23), but also the national question (no. 32), decadence (no. 77 and 78), mysticism (no. 94), etc.

We should also mention polemics with the latter-day descendants of councilism (eg the Dutch groups Spartakusbond and Daad en Gedachte in International Review 2, the Danish group Council Communism in International Review 25;) and with the current animated by Munis (nos. 25, 29, 52). Parallel to these debates within the proletarian milieu we have written a number of critiques of the groups of the swamp (Autonomia in no. 16, modernism in no. 34, Situationism in no.80), as well as waging the combat against political parasitism which in our opinion is a serious danger to the proletarian camp, posed by elements who claim to be part of it but who play an entirely destructive role against it (see for example the Theses on Parasitism in International Review 94, articles on the EFICC (nos. 45, 60, 70, 92, etc), on the CBG (no. 83,etc).

Even when we have polemicised very sharply with other proletarian groups, we have always tried to argue in a serious manner, basing ourselves not on speculation or distortions but on the real positions of other groups. Today, given the huge responsibilities that weigh on a still tiny revolutionary camp, we have tried to make an even more stringent effort to argue in an accurate and fundamentally fraternal manner. Our readers can go through our polemical articles in the International Review and form their own judgement about how well we have succeeded in this regard. Unfortunately however, we can point to very few serious replies to most of these polemics, or to the many orientation texts which we have explicitly offered as contributions for debate within the whole proletarian milieu. Far too often our articles are either ignored or dismissed as the ICC�s latest hobby-horses, with no real attempt to engage the arguments we have put forward. In the spirit of our previous appeals to the proletarian milieu, we can only call on the other groups to recognise and thus begin to overcome the sectarian barriers that prevent real debate between revolutionaries - a weakness that can only benefit the bourgeoisie in the end.

Comrades! Help us distribute the International Review!

It seems to us that we can be proud of the International Review and are convinced that it is a publication that will stand the test of time. Although situations have shifted profoundly since the International Review began, although the ICC�s analyses have matured, we do not think that the I00 issues of the International Review we have published so far, or the many issues we will publish in future, will become obsolete. It is no accident, for example, that many of our new contacts, once they become seriously interested in our positions, begin to build up collections of back issues of the International Review. But we are also only too aware that our press, and the International Review in particular, still only reaches an extreme minority. We know that there are objective historical reasons for the numerical weakness of communist forces today, for their isolation from the class as a whole, but awareness of these reasons, while demanding realism on our part, is not an excuse for passivity. The sales of the revolutionary press and thus of the International Review can certainly be increased, even in only a modest way, by an effort of revolutionary will on the part of the ICC and its readers and sympathisers. This is why we want to conclude this article with an appeal to our readers to participate actively in an effort to increase the distribution and sale of the International Review - by ordering more back copies and complete collections (which we will be selling at an inclusive price of £50 sterling or its equivalent), by taking extra copies to sell, by helping to find and service bookshops and distribution agencies and so on. Theoretical agreement with the idea of the importance of the revolutionary press also implies a practical commitment to selling it, since we are not anarchists who disdain the grubby involvement with the process of selling and accounting, but communists who want to reach out to our class as widely as possible, but understand that this can only be done in an organised and collective way.

At the beginning of this article, we emphasised our organisation�s ability to publish a quarterly review for 25 years, without a break, when so many other groups have published irregularly or intermittently, or simply disappeared. One could of course point out that after a quarter-century�s existence, the ICC has still not increased the frequency of its theoretical publication. This is obviously the sign of a certain weakness, but not in our opinion a weakness in our political positions or analyses. It is a weakness common to the whole Communist Left within which, despite its meagre strength, the ICC is by far the biggest and most widespread organisation. It is a weakness of the whole working class, which although it has proved capable of emerging from the counter-revolution at the end of the 1960s, has encountered some formidable obstacles in its path, not the least being the collapse of the Stalinist regimes and the general decomposition of bourgeois society. A particular characterists society. A particular characteristic of decomposition, which we have pointed out in our press, is the development throughout society, including within the working class, of all kinds of superficial, irrational, or mystical viewpoints, to the detriment of a profound, coherent, and materialist approach, of which marxism is precisely the best expression. Today, books on esotericism encounter vastly more success than works of marxism. Even had we the capacity to publish the International Review more often, in three languages, its present level of distribution would not justify our making such an effort. This is why we call on our readers to help us in this effort of distribution. By taking part in this effort, they take part in the combat against all the miasma of bourgeois ideology and decomposition which the proletariat will have to overcome in order to open the way to the communist revolution.

Amos, December 1999

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Development of proletarian consciousness and organisation:

1921: the proletariat and the transitional state

- 1526 reads

In the previous article in this series, we examined the first major debates within the Communist Party of Russia about the direction being taken by the new proletarian power - in particular, the warnings about the rise of state capitalism and the danger of a bureaucratic degeneration. These debates were at their height in early 1918. But over the next two years Soviet Russia was engaged in a life or death struggle against imperialist intervention and internal counter-revolution. Faced with the immense demands of the civil war, the party closed ranks to fight the common enemy, just as the majority of workers and peasants, despite their growing hardships, rallied to the defence of the soviet power against the attempts by the old exploiting classes to restore their lost privileges.

As we have noted in a previous article (see International Review 95), the party programme drawn up at its 8th Congress in March 1919 expressed this mood of unity within the party, without abandoning the most radical hopes generated by the original impetus of the revolution. This was also a reflection of the fact that the left wing currents in the party - those who had been the main protagonists of the debates in 1918 - still had a considerable influence, and in any case were by no means radically separated from those who were more visibly at the helm of the party, such as Lenin and Trotsky. Indeed some former Left Communists, such as Radek and Bukharin, began to abandon their critical stance altogether, since they tended to identify the emergency "War Communism" measures adopted during the civil war with a real process of communist transformation (see the article on Bukharin in International Review 96).

Other former Lefts were not so easily satisfied with the wide-scale nationalisations and the virtual disappearance of monetary forms which characterised War Communism. They did not lose sight of the fact that the bureaucratic abuses which they had warned about in 1918 had not only survived but had become increasingly entrenched during the civil war, while their antidote - the organs of mass proletarian democracy - had been losing their life-blood at an alarming rate, due both to the demands of military expediency and to the dispersal of many of the most advanced workers to the war fronts. In 1919, The Democratic Centralism group was formed around Osinski, Sapranov, V. Smirnov and others; its main focus was the fight against bureaucratism and in the soviets and the party. It had close links with the Military Opposition which waged a similar combat within the army. It was to prove to be one of the most persistent currents of principled opposition within the Bolshevik party.

Nevertheless, as long as the priority was the defence of the soviet regime against its most open enemies, these debates remained within certain bounds; and in any case, since the party itself remained a living crucible of revolutionary thought, there was no fundamental difficulty in pursuing the discussion through the normal channels of the organisation.

The ending of the civil war in 1920 brought about a crucial change in this situation. The economy was essentially in ruins. Famine and disease on a horrifying scale stalked the land, especially in the cities, reducing these former nerve-centres of the revolution to a level of social disintegration in which the daily, desperate struggle for survival could easily outweigh all other considerations. Tensions that had been held in check by the need to unite against a common foe began pressing towards the surface, and in these circumstances, the rigid methods of War Communism not only failed to contain these tensions, but aggravated them further. The peasants were increasingly exasperated with the policy of grain requisitions that had been introduced to feed the starving cities; workers were less and less willing to accept military discipline in the factories; and on another, more impersonal level, the commodity relations which had been forcibly suspended by the state, but whose material roots had remained untouched, were more and more insistently demanding their due: the black market which had flourished like noxious algae under War Communism had only partially eased the mounting pressure, and with deleterious effects on the social structure.

Above all, the developments within the international situation had brought little relief to the Russian workers' fortress. 1919 had been the pinnacle of the world-wide revolutionary wave upon whose outcome soviet power in Russia was totally dependent. But the same year also saw the defeat of the most decisive proletarian uprisings, in Germany and Hungary, and the failure of mass strikes in other countries (such as Britain and the US) to go onto the level of a political offensive. 1920 saw the effective derailment of the revolution in Italy through the isolation of the workers in factory occupations, while in Germany, the most key country of all, the dynamic of the class struggle was already being posed in defensive terms, as in the response to the Kapp putsch (see International Review 90). In the same year, the attempt to break Russia's isolation through the bayonets of the Red Army in Poland had ended in total fiasco. By 1921 - particularly after the "March Action" in Germany had ended in another defeat (see International Review 93), the most lucid revolutionaries had already begun to realise that the revolutionary tide was ebbing, although it was not yet possible or even accurate to say that it had entered into a definitive retreat.

Russia was therefore an overheated pressure-cooker, and a social explosion could not long be delayed. By the end of 1920, a series of peasant uprisings swept through Tambov province, the middle Volga, the Ukraine, western Siberia and other regions. The rapid demobilisation of the Red Army added fuel to the fire as armed peasants in uniform streamed back to their villages. The central demand of these rebellions was for an end to the system of grain requisitioning and the right of the peasants to dispose of their own products. And as we shall see, in early 1921, the mood of revolt had spread to the wokers of those cities which had been the epicentre of the October insurrection: Petrograd, Moscow … and Kronstadt.

Faced with this burgeoning social crisis, it was inevitable that divergences within the Bolshevik party should also have reached a critical juncture. The disagreement was not about whether the proletarian regime in Russia was dependent of the world revolution: all the currents within the party, albeit with different nuances, still held to the fundamental conviction that without the extension of the revolution, the proletarian dictatorship in Russia could not survive. At the same time, since the Russian soviet power was seen as a crucial bastion conquered by the world proletarian army, there was also general agreement that a 'holding operation' must be attempted, and that this necessitated the reconstruction of Russia's ruined economic and social edifice. The differences emerged about the methods the soviet power could and should use if it was to stay on the right path and avoid succumbing to the weight of alien class forces inside and outside Russia. Reconstruction was a practical necessity: the question was how to carry this out in a way that would ensure the proletarian character of the regime. The focal point for these differences in 1920 and early 1921 was the "trade union debate".

Trotsky and the militarisation of labour

This debate had in fact arisen at the very end of 1919, with the unveiling by Trotsky of his proposals for restoring Russia's ravaged industrial and transportation system. Having achieved extraordinary success as the commander of the Red army during the civil war, Trotsky (despite one or two moments of hesitation when he considered a very different approach) came out in favour of applying the methods of War Communism to the problem of reconstruction: in other words, in order to re-gather a working class which was in danger of decomposing into a mass of isolated individuals living by petty trade, petty thieving, or melting back into the peasantry, Trotsky advocated the outright militarisation of labour. He first formulated his view in his 'theses on the transition from war to peace' (Pravda, 16 December 1919) and further defended them at the 9th party Congress in March-April 1920. "The working masses cannot be wandering all over Russia. They must be thrown her and there, appointed, commanded, just like soldiers." Those accuse of "deserting from labour" would be placed in punitive battalions or labour camps. In the factories, military discipline would prevail; like Lenin in 1918, Trotsky extolled the virtues of one-man management and the "progressive" aspects of the Taylor system. As for the trade unions, their task in this regime would be to subordinate themselves totally to the state: "The young socialist state requires trade unions not for a struggle for better conditions of labour - that is the task of the social and state organisations as a whole - but to organise the working class for the ends of production, to educate, discipline, distribute, group, retain certain categories and certain workers at their posts for fixed periods - in a word, hand in hand with the state to exercise their authority in order to lead the workers into the framework of a single economic plan." (Trotsky, Terrorism and Communism, 1920; New Park edition 1975, p.153).

Trotsky’s views – though initially, Lenin was largely in support of them – provoked vigorous criticism from many within the party, and not only those accustomed to being on its left. These criticisms only led Trotsky to harden and theorise his views. In Terrorism and Communism – which appears to be as much a response to Trotsky’s Bolshevik critics as to the likes of Kautsky, its main polemical target – Trotsky goes so far as to argue that because forced labour had played a progressive role in previous modes of production, such as Asiatic despotism and classical slavery, it was pure sentimentalism to argue that the workers’ state could not use such methods on a broad scale. Indeed, Trotsky did not even shrink from arguing that militarisation is the specific form of the organisation of labour in the transition to communism: “the foundations of the militarisation of labour are those forms of state compulsion without which the replacement of capitalist economy by the socialist will forever remain an empty sound” (ibid, p. 152). In the same work, Trotsky reveals the extent to which the notion that the dictatorship of the proletariat is only possible as the dictatorship of the party had become a matter of theory and almost of principle: “We have more than once been accused of having substituted for the dictatorship of the soviets the dictatorship of the party. Yet it can be said with complete justice that the dictatorship of the soviets became possible only by means of the dictatorship of the party. It is thanks to the clarity of its theoretical vision and its strong revolutionary organisation that the party has afforded to the soviets the possibility of being transformed from shapeless parliaments of labour into the apparatus of the supremacy of labour. In this ‘substitution’ of the power of the party for the power of the working class there is nothing accidental, and in reality there is no substitution at all. The communists express the fundamental interests of the working class. It is quite natural that, in the period in which history brings up those interests, in all their magnitude, on to the order of the day, the communist have become the recognised representatives of the working class as a whole.” (ibid p. 123). This is a far cry from Trotsky’s definition of the soviets in 1905 as organs of power which go beyond bourgeois parliamentary forms, as indeed it is from Lenin’s position in State and Revolution in 1917, and the Bolsheviks’ practical approach in October, when the idea of the party taking power had been more an unconscious concession to parliamentarism than a worked-out theory, and when in any case the Bolsheviks had shown themselves willing to form a partnership with other parties. Now, the party had “a historical birthright” to exercise the proletarian dictatorship, “even if that dictatorship temporarily clashed with the passing moods of the workers’ democracy" (Trotsky at the 10th party Congress, quoted in Deutscher, The Prophet Armed, pp 508-9).

The fact that this debate developed essentially around the question of the trade unions may seem strange given that the emergence of new forms of workers' self-organisation in Russia itself - the factory committees, the soviets etc - had effectively rendered these organisations obsolete, a conclusion that had already been drawn by many communists in the industrialised west, where the unions had already been through a long process of bureaucratic degeneration and integration into the capitalist order. The fact that the debate had this focus in Russia was thus partly a reflection of Russia' "backwardness", of a condition in which the bourgeoisie had not developed a sophisticated state apparatus capable of recognising the value of trade unions as instruments of class peace. For this reason it could not be said that all the unions which had been formed prior to and even during the 1917 revolution were organs of the enemy class. In particular there had been a strong tendency towards the formation of industrial unions which still expressed a certain proletarian content.

Be that as it may, the real issue in the debate provoked by Trotsky went much deeper. In essence it was a debate about the relationship between the proletariat and the state of the transition period. The question it raised was this: could the proletariat, having overthrown the old bourgeois state, identify itself totally with the new "proletarian" state, or were there compelling reasons why the working class should protect the autonomy of its own class organs - even, if necessary, against the demands of the state?

Trotsky's position had the merit of supplying a clear answer: yes, the proletariat should identify itself with and even subordinate itself to the "proletarian state" (and so, in fact, should the proletarian party which was to function as the executive arm of the state). Unfortunately, as can be seen in his theorisation of forced labour as the method for building communism, Trotsky has largely lost sight of what is specific to the proletarian revolution and to communism - the fact that this new society can only be brought about by the self-organised, conscious activity of the proletarian masses themselves. His response to the problem of economic reconstruction could only have further accelerated the bureaucratic degeneration which was already threatening to engulf all the concrete forms of proletarian self-activity, including the party itself. And so it passed to other currents within the party to give voice to a class reaction against this dangerous tendency in Trotsky's thinking, and against the principal dangers facing the revolution itself.

The Workers' Opposition

The fact that deep issues were at stake in this debate was reflected in the number of positions and groupings that arose around it. Lenin himself, who wrote of these differences "the Party is sick. The Party is down with a fever" ( 'The Party Crisis', Pravda, January 21, 1921) was only part of one grouping - the so-called 'Group of Ten'; The Democratic Centralists and Ignatov's group had their own positions; Bukharin, Preobrazhinsky and others tried to form a "buffer group", and so on. But alongside Trotsky's group, the most distinctive approaches were adopted by Lenin on the one hand, and by the Workers' Opposition, led by Kollantai and Shliapnikov, on the other.

The Workers' Opposition undoubtedly expressed a proletarian reaction against Trotsky's bureaucratic theorisations, and against the real bureaucratic distortions that were eating away at the proletarian power. Faced with Trotsky's apology for forced labour, it was by no means demagogy or phrasemongering for Kollontai to insist in her pamphlet The Workers' Opposition, written for the 10th party Congress in March 1921, that "this consideration, which should be very simple and clear to every practical man, is lost sight of by our party leaders: it is impossible to decree communism. It can be created only by the process of practical research, through mistakes, perhaps, but only by the creative powers of the working class itself" (London Solidarity pamphlet no 7, p33). In particular, the Opposition rejected the tendency of the regime to impose a managerial dictatorship in the factories, to the point where the immediate situation of the industrial worker was becoming more and more indistinguishable from what it had been before the revolution. It thus defended the principle of collective workers' management against the over-use of specialists and the practice of one-man management.

On a more global level, the Workers' Opposition offered a keen insight into the relationship between the working class and the soviet state. For Kollontai, this was in fact the key issue: "Who shall develop the creative powers in the sphere of economic reconstruction? Shall it be purely class organs, directly connected by vital ties with the industries - that is, shall industrial unions undertake the work of reconstruction - or shall it be left to the soviet machine which is separated from direct industrial activity and is mixed in its composition? This is the root of the break. The Workers' Opposition defends the first principle, while the leaders of the party, whatever their differences on secondary matters, are in complete accord on this cardinal point, and defend the second principle" (ibid p4).

In another passage of the text, Kollontai explains further this notion of the heterogeneous nature of the soviet state: "any party standing at the head of a heterogeneous soviet state is compelled to consider the aspirations of peasants with their petty bourgeois inclinations and resentments towards communism, as well as lend an ear to the numerous petty bourgeois elements, remnants of the former capitalists in Russia and to all kinds of traders, middlemen, petty officials etc. These have rapidly adapted themselves to the soviet institutions and occupy responsible positions in the centres, appearing in the capacity of agents of different commissariats, etc ... These are the elements - the petty bourgeois elements widely scattered through the soviet institutions, the elements of the middle class, with their hostility towards communism, and with their predilections towards the immutable customs of the past, with resentment and fears towards revolutionary acts. These are the elements that bring decay into our soviet institutions, breeding there an atmosphere altogether repugnant to the working class" (ibid pp6-7).

This recognition that the soviet state - both because of its need to reconcile the interests of the working class with those of other strata , and because of its vulnerability to the virus of bureaucracy - could not itself play a dynamic and creative role in the creation of the new society was an important sight, albeit undeveloped. But these passages also expose the principal weaknesses of the Workers' Opposition. Lenin in his polemics with the group, dismissed it as an essentially petty bourgeois, anarchist and syndicalist current. This was false: for all its confusions, it represented a genuine proletarian response to the dangers besetting the soviet power. But the accusation of syndicalism is not altogether wrong either. This is apparent in its identification of the industrial unions as the main organs for the communist transformation of society, and its proposal that the management of the economy should be placed in the hands of an "All-Russian Congress of Producers". As we have said already, the Russian revolution had already shown that the working class had gone beyond the union form of organisation, and that in the new epoch of capitalist decadence unions could only become organs of social conservation. The industrial unions in Russia were certainly no guarantee against bureaucratism and the organisational dispossession of the workers; the emasculation of the factory committees which had emerged in 1917 largely took the form of incorporating them into the unions, and consequently, the state. It is also worth pointing out that when the Russian workers did enter into action on their own terrain in the very year of the trade union debate - in the strikes in Moscow and Petrograd - they again confirmed the obsolescence of the trade unions, since to defend their most material interests they resorted to the classic methods of the proletarian struggle in the new epoch: spontaneous strikes, general assemblies, elected strike committees subject to immediate revocation, massive delegations to other factories, etc. Even more importantly, the Workers' Opposition's emphasis on the unions expressed a total disillusionment with the most important mass proletarian organs - the workers' soviets, which were capable of uniting all workers across sectional boundaries and of combining the economic with the political tasks of the revolution1. This blindness to the importance of the workers' councils logically extended to a total underestimation of the primacy of politics over economics in the proletarian revolution. The one great obsession of the Kollontai group was the management of the economy, to the point where it was almost proposing a divorce between the political state and the "producers congress". But in a proletarian dictatorship, the workers' management of the economic apparatus is not an end in itself, but only an aspect of its overall political domination over society. Lenin also made the criticism that this idea of a "congress of producers" was more applicable to the communist society of the future, where there are no more classes and all are producers. In other words, the Opposition's text contains a strong suggestion that communism could be achieved in Russia provided the problems of economic management were solved correctly. This suspicion is reinforced by the scant references in Kollontai's texts to the problem of the extension of the world revolution. Indeed, the group seems to have had little to say about the international policies of the Bolshevik party at the time. All these weaknesses are indeed expressions of the influence of syndicalist ideology, even if the Opposition cannot be reduced to nothing more than an anarchist deviation.

Lenin's views on the trade union debate

As we have seen, Lenin considered that the trade union debate expressed a profound malaise in the party; given the critical situation facing the country, he even felt that the party had been mistaken in authorising the debate at all. He was especially angry with Trotsky for the manner in which he had provoked the debate, and accused him of acting in an irresponsible and factional manner over a number of organisational issues linked to the debate. Lenin also seemed to be dissatisfied with the very focus of the debate, feeling that "a question came to the forefront which, because of the objective conditions, should not have been in the forefront" (report to the 10th party Congress, March 8, 1921). Perhaps his main fear was that the apparent disorder in the party would only exacerbate the growing social disorder within Russia; but perhaps he also felt that the real nub of the question was elsewhere.

Be that as it may, the most important insight Lenin offered in this debate was certainly on the problem of the class nature of the state. This is how he framed the question in a speech given to a meeting of communist delegates at the end of 1920: "While betraying this lack of thoughtfulness, Comrade Trotsky falls into error himself. He seems to say that in a workers' state it is not the business of the trade unions to stand up for the material and spiritual interests of the working class. That is a mistake. Comrade Trotsky speaks of a 'workers' state'. May I say that this is an abstraction. It was natural for us to write about a workers' state in 1917; but it is now a patent error to say: 'Since this is a workers' state without any bourgeoisie, against whom then is the working class to be protected, and for what purpose?' The whole point is that it is not quite a workers' state. That is where Comrade Trotsky makes one of his main mistakes ... For one thing, ours is not actually a workers' state but a workers' and peasants' state. And a lot depends on that (interjection from Bukharin: 'What kind of state? A workers' and peasants' state?'). Comrade Bukharin back there may well shout, 'What kind of state? A workers' and peasants' state?' I shall not stop to answer him. Anyone who has a mind to should recall the recent Congress of Soviets and that will be answer enough.

But that is not all. Our Party Programme - a document which the author of The ABC of Communism knows very well - shows that ours is a workers' state with a bureaucratic twist. We have had to mark it with this dismal, shall I say, tag. There you have the reality of the transition. Well, is it right to say that in a state that has taken this shape in practice the trade unions have nothing to protect, or that we can do without them in protecting the material and spiritual interests of the proletariat? No, this reasoning is theoretically quite wrong... We now have a state under which it is the business of the massively organised proletariat to protect itself, while we, for our part, must use these workers' organisations to protect the workers from their state, and to get them to protect our state" ('The Trade Unions, the Present Situation, and Trotsky's Mistakes', Collected Works vol 32, pp22-3).

In a later article Lenin retreated a bit on this formulation, admitting that Bukharin had been right to question his terms: "What I should have said is: 'A workers state is an abstraction. What we actually have is a workers' state with this peculiarity, firstly that it is not the working class but the peasant population that predominates in the country, and secondly, that it is a workers' state with a bureaucratic distortion'. Anyone who reads the whole of my speech will see that this correction makes no difference to my meaning or conclusions" ('The Party Crisis', Pravda, January 21 1921, CW vol 32 p48).

In fact Lenin showed a great deal of political wisdom in questioning the notion of the "workers state". Even in countries which don't have a large peasant majority, the transitional state will still have the task of encompassing and representing the needs of all the non-exploiting strata in society, and can thus not be seen as a purely proletarian organ; in addition to this, and partly as a result of it, its conservative weight will tend to express itself in the formation of a bureaucracy towards which the working class will have to be especially vigilant. Lenin had intuited all this even through the distorting mirror of the trade union debate.

It is also worth noting that on this point about the class nature of the transitional state there is a real convergence between Lenin and the Workers' Opposition. But Lenin's criticism of Trotsky did not lead him to sympathise with the latter. On the contrary, he saw the Workers' Opposition as the main danger; the Kronstadt events in particular convinced him that it expressed the same threat of petty bourgeois counter-revolution. Under Lenin's instigation. the 10th party Congress passed a resolution on "The syndicalist and anarchist deviation in our party" which explicitly stigmatises the Workers' Opposition: "Hence, the views of the Workers' Opposition and of like-minded elements are not only wrong in theory, but are an expression of petty bourgeois and anarchist wavering, and actually weaken the consistency of the leading line of the Communist party and help the class enemies of the proletarian revolution" (CW vol 32 p248).

As we have already said, these accusations of syndicalism are not entirely without foundation. But Lenin's principal argument on this point is deeply flawed: for him, the syndicalism of the Workers' Opposition resides not in the fact that it emphasised economic management by the trade unions rather than the political authority of the soviets, but in its alleged challenge to the rule of the Communist Party. "The Theses of the Workers' Opposition fly in the face of the decision of the Second Congress of the Comintern on the Communist Party's role in operating the dictatorship of the proletariat" (Summing up speech on the report of the CC of the RCP, March 9 1921, CW vol 32, p199). Like Trotsky, Lenin had definitely come to the view that "the dictatorship of the proletariat cannot be exercised through an organisation embracing the whole of that class, because in all capitalist countries (and not only over here, in one of the most backward) the proletariat is still so divided, so degraded, and so corrupted in parts (by imperialism in some countries) that an organisation taking in the whole proletariat cannot directly exercise proletarian dictatorship. It can be exercised only by a vanguard that has absorbed the revolutionary energy of the class" ('The Trade Unions, the Present Situation, and Trotsky's Mistakes', op cit). Faced with Trotsky, this was an argument for the unions to act as "transmission belts" between the party and the class as a whole. But faced with the Workers' Opposition, it was an argument for declaring their views to be outside of marxism altogether - along with anyone else who questioned the notion of the party exercising the dictatorship.

In fact the Workers' Opposition did not fundamentally challenge the notion of the party exercising the dictatorship: Kollontai's text proposes that "the Central Committee of our party must become the supreme directing centre of our class policy, the organ of class thought and control over the practical policy of the soviets, and the spiritual personification of our basic programme" (op cit pp41-2). It was for this very reason that the Workers' Opposition supported the crushing of the Kronstadt rebellion; and it was the latter which posed the most explicit challenge to the Bolsheviks' monopoly of power.

The Kronstadt tragedy

1. The official view and its reluctant supporters

In the wake of widespread strikes in Moscow and Petrograd, the Kronstadt rebellion broke out at the very time the Bolshevik party was holding its 10th Congress2. The strikes had arisen around largely economic issues, and had been met with a mixture of concessions and repression by the regional state authorities. But the workers and sailors of Kronstadt, initially acting in solidarity with the strikes, had gone on to raise, alongside demands for relaxing the harsh economic regime of War Communism, a series of key political demands: new elections to the soviets, freedom of the press and of agitation for all working class tendencies, the abolition of political departments in the armed forces and elsewhere, "because no party should be given privileges in the propagation of its ideas or receive the financial support of the state for such purposes" (from the resolution adopted on the battleship Petropavlovsk and at the mass assembly of 1st March). It amounted to a call to replace the power of the party-state with the power of the soviets. Lenin - rapidly echoed by the official mouthpieces of the state – denounced it as the result of a White Guard conspiracy, although he did say that the reactionaries were manipulating the real discontent of the petty bourgeoisie and even a section of the working class that was susceptible to its ideological influence. In any case, “This petty bourgeois counter-revolution is undoubtedly more dangerous than Denikin, Yudenich and Kolchak put together, because ours is a country where peasant property has gone to ruin and where, in addition, the demobilisation has set loose vast numbers of potentially mutinous elements" (speech to the 10th Congress, op cit, p184).

The initial argument, that the mutiny was from the outset led by White Guard generals on the spot, was soon proved to be without foundation. Isaac Deutscher, in his biography of Trotsky, notes the unease that set in among the Bolsheviks after the rebellion had been crushed: “Foreign communists who visited Moscow some months later and believed that Kronstadt had been one of the ordinary incidents of the civil war, were ‘astounded and troubled’ to find that the Bolsheviks spoke of the rebels without any of the anger and hatred which they felt for the White Guards and the interventionists. Their talk was full of ‘sympathetic reticences’ and sad, enigmatic allusions, which to the outside betrayed the party’s troubled conscience” (The Prophet Armed, p514, OUP edition, 1954). Certainly Lenin had seen very quickly that the rebellion proved the impossibility of maintaining the rigours of war communism, the NEP was in one sense a concession to the Kronstadters’ call for an end to the grain requisitions, although the central demands of the rebellion – the political ones, centring around the reanimation of the soviets – were totally rejected. They were seen as the vehicle through which the counter-revolution could unseat the Bolsheviks and destroy all remnants of the proletarian dictatorship. “The way the enemies of the proletariat take advantage of every deviation from a thoroughly consistent, communist line was perhaps most strikingly illustrated in the case of the Kronstadt mutiny, when the bourgeois counter-revolutionaries and White Guards in all countries of the world immediately expressed their willingness to accept the slogans of the soviet system, if only they might thereby secure the overthrow of the dictatorship of the proletariat in Russia, and when the Social-Revolutionaries and the bourgeois counter-revolutionaries in general resorted in Kronstadt to slogans calling for an insurrection against the soviet government of Russia ostensibly in the interests of the soviet power. These facts fully prove that the White Guards strive, and are able, to disguise themselves as communists, solely for the purpose of weakening or destroying the bulwark of the proletarian revolution in Russia” (draft resolution of the 10th Congress of the RCP on party unity, written by Lenin, CW, vol. 32, pp241-2).