International Review 1990s : 60 - 99

- 7227 reads

Site structure:

1990 - 60 to 63

- 5573 reads

International Review no.60 - 1st quarter 1990

- 3931 reads

World economic crisis: After the East, the West

- 3675 reads

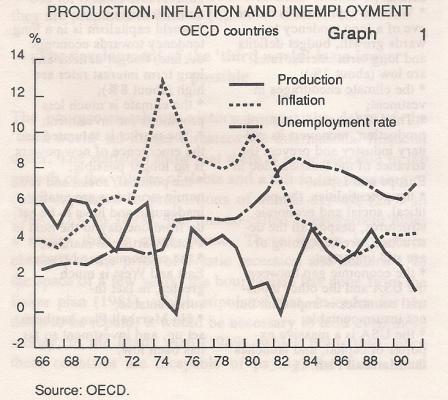

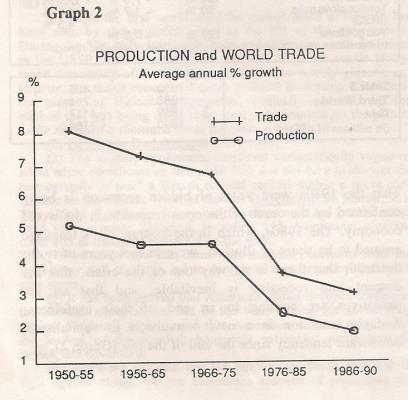

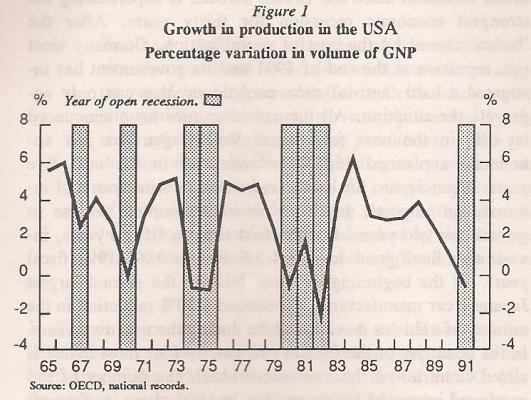

The 'equilibrium' upon which the planetary imperialisms have rested since the end of the Second World War, since Yalta, is being overturned because of the economic collapse of the USSR and the resulting implosion of its bloc. Next to the economic disaster that has befallen its rival, the western bloc seems to be the mighty victor: the exuberant abundance of the shop-windows in the big industrial countries is the best weapon of western propaganda in contrast to the dramatic shortages in the east. However, the illusion of economic victory in the west looks like being short-lived: the economic crisis of generalized overproduction, which has been going on for over 20 years, is a world-wide crisis. Following the under-developed countries' slide into bottomless misery at the end of the 70s, the economic collapse of the eastern bloc at the end of the 80s, far from demonstrating the vitality of the industrial countries of the west, is on the contrary a harbinger of the world-wide catastrophe that is to come. The next decisive step towards this will be the economic collapse of the most developed industrial countries. What we're seeing is less a victory of the west than the defeat of the east. The whole evolution of the western economies over a number of years points to a tomorrow that is anything but bright.

What happened on Friday 13 October 1989? In one session, Wall Street plunged by 7%, and this despite the massive intervention of the so-called 'institutional' investors, for whom the American state immediately opened up new lines of credit so they could buy shares and stop the slide.

After a weekend of intensive meetings in the great central banks of the main western economies, the effects knocked on; on Monday 15 October, Frankfurt went down 13%, Paris 6.9%, London 4.6%, although Tokyo stood firm. However, the joint measures adopted by the economic powers began to take effect: that same day Wall Street improved by 3.4%. In the week that followed, the indices stabilized.

But all this was a clear warning. 200 billion dollars went up in smoke. A new purge was imposed on stock market speculation. Despite the heavy bill, the central banks rejoiced over their 'technical mastery'. They had limited the damage. However, there was no euphoria. On the contrary. This new upset for stock exchange speculation only fuelled disquiet. 1987 was no accident. OK, the markets were stabilized, but for how long?

Capitalists aren't particularly suspicious people, but they will end up being just that. The month of October is decidedly prone to stock exchange collapses. 1929, and more recently in 1987. However, apart from these repetitive aspects, the conditions in which these collapses have taken place are very different. Obviously the situation of the world economy is very different in the 80s from what it was in 1929: we have already dealt with this amply in the International Review and we won't go over it again here1.

But while the same causes - the raising or interest rates by the big banks - have produced the same effects - the drying up of credit reviving fears of recession and provoking panic on the stock exchange - between October 1987 and October 1989 the international situation has changed a great deal. There has been a marked acceleration in the decline of the American economy and the instability of the world situation has been considerably accentuated.

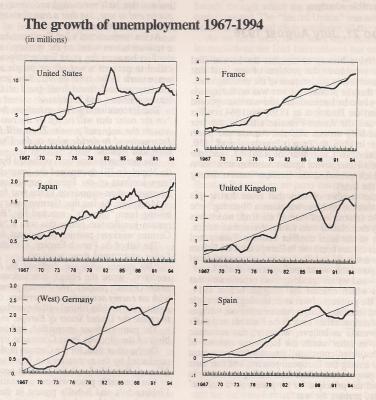

Faced with the recession, a headlong flight into the debt

During the 1970s, the huge credits doled out to the under-developed countries of the periphery made it possible, to a great extent, to absorb the overproduction of the industrialized countries. However, this policy reached its limits with the crisis of the dollar. The 900 billion dollars borrowed by the poor countries of Latin America, Africa and Asia will never be repaid. These fragile economies were ravaged by debt and inflation. They lost all solvencies and were definitively closed as outlets for the commodities produced on a massive scale in the industrial world. The world market contracted brutally and, following in the wake of the American economy, the economy of the whole planet plunged into recession at the beginning of the 80s.

Recession is the worst of all evils for capitalism. It means a fall in production, factory closures, the development of unemployment and a dizzying rise in unpaid debts. It expresses in a brutal way the impasse that capitalism has reached. Such a situation endangers the stability of the dollar, the world market's leading currency and symbol of American power and domination. Such a situation is untenable for American capitalism, because it not only threatens its economic power, but also its position as an imperialist giant.

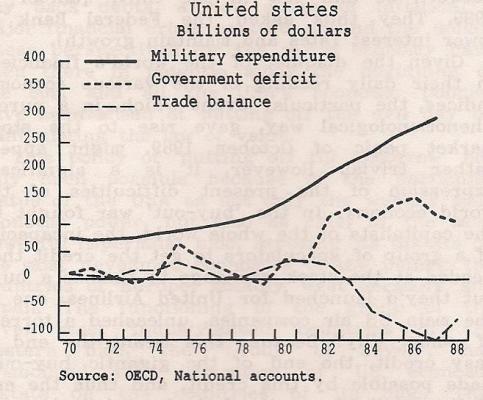

The USA isn't just the world's main economic power, it's also the dominant imperialist power within the dominant bloc. Maintaining economic activity and growth is a priority for America to safeguard its own economic and imperialist interests. After two years of economic purges imposed by the austerity policies of the first term of the Reagan presidency, the American state then had to get its economy on the move once again. This was done on the basis of what American imperialism required in order to face up to its Russian rival. The invasion of Afghanistan by the Red Army at the end of 1979 brought a vicious heating-up of inter-imperialist tensions, and led the USA to undertake a vast program of modernizing its armaments. The American 'revival' was a revival of arms production, a recovery based on the development of the war economy. The USA's military budgets swelled up beyond measure, and at the same time the budget deficit became more and more colossal, despite a drastic reduction in social spending.

However arms production has the particular feature of being a pure destruction of capital which acts as a fetter on economic development as a whole. Armaments are neither consumer goods permitting the reproduction of the labor force, nor a means of production permitting an accumulation of capital. The economic catastrophe of the eastern countries clearly expresses this reality: the absolute priority given to the war economy for decades has led to the asphyxiation of the whole economy.

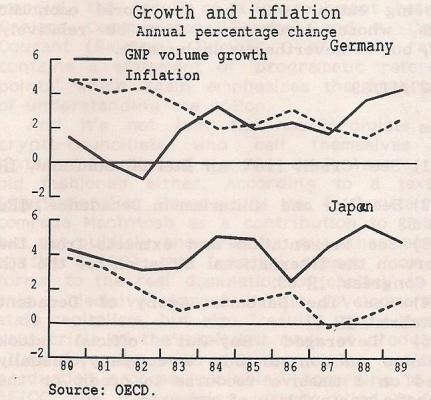

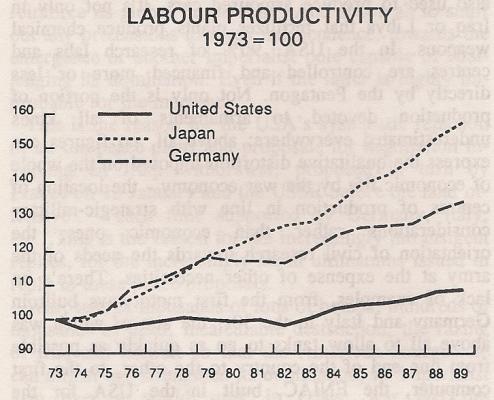

To a lesser extent, but just as clearly, this reality has also been imposed on the USA. Since the 1950s America's competivity on the world economic arena has been eroded more and more. It's certainly not one of the lesser paradoxes that we are now seeing the countries which were defeated in the Second World War, Japan and Germany, beating all records for competivity. This is due to the fact that these countries, after the war that they lost, rebuilt their destroyed economies on a more modern basis, using what were then the most advanced technologies, whereas the USA's productive apparatus at the end of the war hadn't been destroyed, but had been worn out by the demands of arms production and was to a large extent out of date and obsolete. This relative loss of competivity at the end of the war was further exacerbated in the years that followed, since the defeated countries were forbidden by treaty to engage in rearmament, and were thus able to invest in production without sacrificing this to the needs of the war economy; the USA, on the other hand, had to maintain an imposing military sector, corresponding to its role and needs as leader of an imperialist bloc. This severely limited its competivity on the economic level.

The Reagan presidency's policies of 'recovery' via the war economy thus had the principal result of further weakening the competivity of the American economy. The budget deficits run up to finance the military effort were thus supplemented by trade deficits which also broke all records throughout the 80s. In order to finance these colossal deficits, the USA had to go into debt, and this soon pulverized the records reached by the previously most indebted countries. Today, the debts owed by countries like Brazil or Mexico (a hundred billion dollars for each in 1980), which made financiers tremble at the beginning of the 80s, almost look ridiculous compared to the American debt at the end of the 80s: more than 500 billion dollars of external debt and an internal debt estimated at between 6000 and 8000 billion dollars. The annual American budget was pruned by 170 billion dollars for the payment of the debt. This situation can only get worse and the debts can only get bigger.

An extremely significant pointer to the weakness of the American economy is the fact that, during the 1980s, foreign investment in the USA went well beyond American investments in other parts of the world. Whole chunks of the American economy are today the property of Japanese and European enterprises.

American capitalism, in its search for fresh money, has used all the resources accruing to it because of its status as the world's first economic power and leader of the most powerful imperialist bloc. His Majesty the Dollar has imposed his supremacy in the following ways:

- the American federal bank, in the name of liberalism, has guided the world economy in a very statist manner, through its policy of interest rates;

- a policy of supporting the dollar has been imposed on the main industrialized countries, who have become the USA's money-lenders.

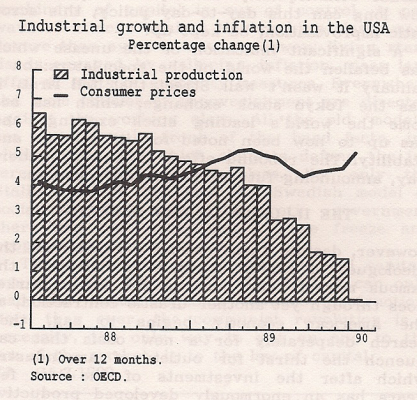

This policy has made it possible to put a temporary brake on the slide towards recession, and to keep the most industrialized countries afloat. It has been accompanied by an intense ideological campaign about the glories of the capitalist economy. In 1987, euphoria still reigned: official 'growth' was beating all the records and inflation was at its low point. The stock market slide was soon halted and speculation took wing again.

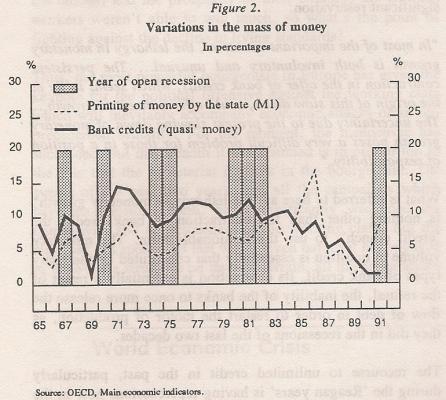

The crisis of credit: the limits of a policy

The official, pseudo-growth of the second Reagan Presidency was in fact a hidden recession of the world economy2. What really happened was a growth in the destruction of capital and an artificial growth of the unproductive sectors. Economic activity was maintained in an artificial manner: production wasn't really paid for, commodities were exchanged against debts. In these conditions production was not directly production of value. Capitalism can only keep up such a semblance of economic activity through cheating the laws of the market on a vast scale, but this only destabilizes the world economy more and more and builds up a gigantic pile of waste.

This situation has been masked by the increasing manipulation of economic indices and the deafening noise campaigns about the efficiency of the USA's 'liberal' economic policies: the famous Reaganomics.

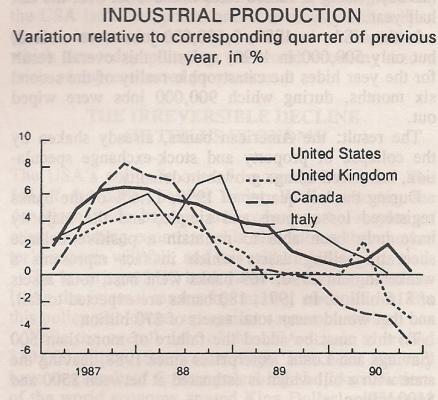

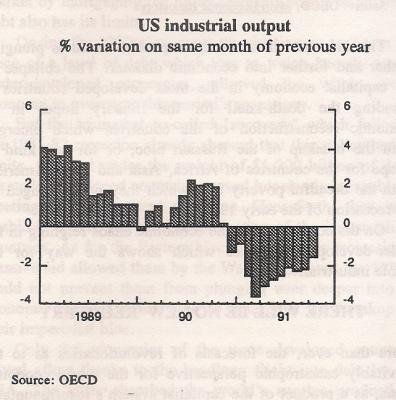

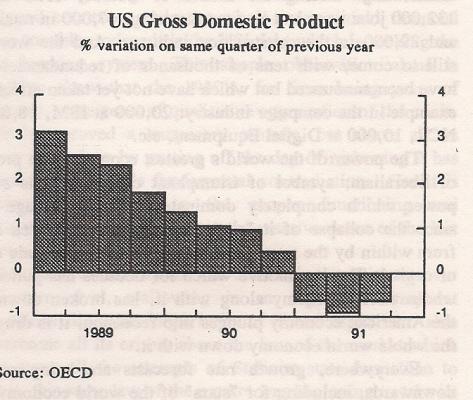

But since 1987, the situation has changed a lot. The euphoria has subsided, doubt has crept in. The official statistics, confronted with the reality of the crisis, have been obliged to bear some relation to reality, otherwise they would be of no use whatsoever. Official 'growth' has begun to go into decline while inflation has made a definite comeback. The example of Britain is particularly significant in this respect. Britain had a policy of Reaganomics before the USA did, but it is no longer able to hold back the rise of inflation, whereas lending rates have gone up and plunged the economy into recession.

Of course the American economy, the worlds no 1, is of a different caliber from Britain's, and the dollar isn't the pound Sterling. Moreover, the USA can profit from its position as head of the bloc and impose a discipline which suits its interests. However, the blind laws of the market are at work here; they have already hurled the under-developed countries of the periphery into an economic chaos from which there is no escape; today they're bringing down the British economy; and they are also eroding the economic power of America, which is at the centre of the economic contradictions of world capitalism.

For years now, through the recourse to credit, a mountain of dollars has been in circulation. As it stands, the debt of the peripheral countries has reached 1300 billion dollars. The external debt of the USA has gone up to 500 billion dollars, but this hides the internal debts, where the accumulated borrowings of the state, of enterprises and individuals, are estimated at between 6000 and 8000 billion dollars. The development of credit which can never be repaid, in fact of fictitious capital, is completely out of synch with the development of the real economy, of actual production3. Financial and stock exchange speculation hasn't solved anything. Stimulated by the policy of 'leveraged buy-outs'4, enterprises have seen their share values go up five or 10 times, but the development of production in no way justifies this rise.

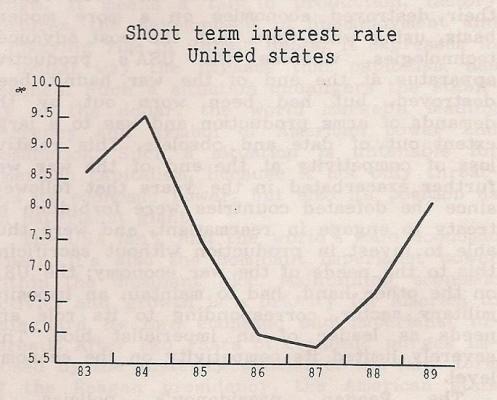

In these conditions, the laws of the capitalist market are pushing for a more real relationship between the value of the dollar and the actual production of wealth. Inflationary pressures are getting stronger and stronger. Faced with these pressures, the policy of the American Federal Bank has had to yield and lower the rates, to reopen the flood-gates of credit, in order to avoid a rapid decline in growth, which would have catastrophic consequences for the world's economic equilibrium.

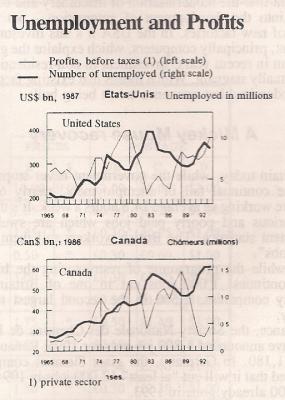

Before the mini-collapse of the stock exchange in October 1989, the managers of one hundred of the biggest American enterprises had sounded the alarm, disturbed as they were by the slow-down in activity concretized in a brutal fall in the profits of US enterprises (the flowers of American capitalism, like General Motors, Ford and IBM, saw their profits fall by between 30 and 40% in the third quarter of 1989. They thus asked the Federal Bank to lower interest rates and maintain growth).

Given the disquiet of the world's financiers in their daily reading of the various economic indices, the particular event which, in a purely phenomenological way, gave rise to the stock market panic of October 1989, might appear rather trivial. However, it is a significant expression of the present difficulties of the world economy. In the 'buy-out' war fought by the capitalists of the whole world, the incapacity of a group of speculators to get the credit they needed at the stock exchange to finance a buyout they'd launched for United Airlines, one of the main US air companies, unleashed a torrent of panic. Why? Because this meant the end of easy credit, the end of the gigantic buy-outs made possible by this credit, and thus the end of the artificial growth of stock market shares. Once again the USA recoiled in front of the economic implications of a policy of austerity, of rigor vis-a-vis the dollar. At the beginning of November 1989, the Federal Bank had to lower its rates and re-open the coffers of credit. While this policy might hold back the fall in production, it is incapable of stimulating growth. More and more, the new credits put into circulation will be used to pay for previous debts, or to fuel speculation, and less and less to feed production.

The more credit grows, the less effective it is in the real economy, and the rate of growth will decline in an irresistible manner. On the other hand, the policy of easy credit does have a direct effect today, and that is to encourage inflation. In fact, the Federal Bank has chosen inflation rather than face the immediate danger of a catastrophic fall in production.

For years, American economists and political leaders have been talking about a 'soft landing' for the American economy, and in fact the USA's economic policies have managed to avoid excessive damage: the American airplane has managed to make a gentle descent. But where will it land? Won't all the difficult maneuvers it's tried up to now lead to a break-down? Won't the fuel of credit fail it in the end?

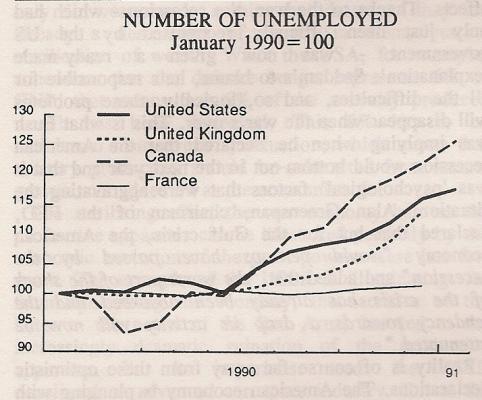

From the moment the American economy stops flying, it will mean a new and brutal dive into recession by the world economy. The American market will be closed to Japanese and European imports, there will be a growing incapacity to pay back debts, a new surge of inflation, a major financial crisis centered around the dollar. These perspectives for the world economy have been there in potentio since the beginning of the 80s, and all the USA's economic policies have been aimed at putting off the evil day by manipulating the law of value.

This policy of 'putting off till tomorrow' has only been possible because of the particular status of the USA as not only the world's main economic power, but also as chief of the most powerful imperialist bloc, imposing its diktats on the most developed economies of the planet: the countries of Europe, notably West Germany and Japan. The functioning of the group of the seven most industrialized countries of the western bloc, the 'Group of Seven', has symbolized this imposition of US economic diktats on the countries of its bloc. This discipline, especially as it affected Germany and Japan, has been the sine qua non of economic stability throughout the 80s. Despite the catastrophe of the 'third world', the overall descent of the world economy, the industrialized countries' slide into the morass of a hidden recession has taken place in a 'soft' manner from the economists' point of view, of course.

However, the conditions which allowed the USA to carry out these economic policies have now changed:

the dilapidated state of the American economy contrasts sharply with the relative health of its main economic rivals, Japan and Germany. Whereas the USA has run up huge trade deficits, Japan and Germany have broken all the export records. In contrast to the postwar reconstruction period, today European and Japanese capital is buying up whole chunks of the American economy. The locomotive is running out of steam, and at the same time as inflation is coming back in force, there is a recession on the American horizon. There is a threat of a dollar crisis and the USA's position of economic leadership is beginning to look shaky;

- the economic collapse of the Russian bloc, just as it has reasserted the unavoidable reality of the law of value within the capitalist system, is now overturning the global balance between the blocs which has 'organized ' the world since Yalta. The discipline which the USA has managed to impose on its main economic competitors, Europe and Japan, was held together only by the imperialist threat from the Russian bear. A bolt has been pulled back in the east, and this will overturn the relationships between the main economic powers of the western bloc.

The collapse of the Eastern Bloc and destabilization of the economy

The new decade is opening up under the auspices:

- of a dramatic dive into the economic crisis, which is based on generalized overproduction in relation to existing markets - markets which are going to get even more restricted;

- of a growing destabilization of the equilibrium which has dominated the world since the second world war.

The collapse of the Russian bloc will lead to the destabilization of the western bloc, and this will have particularly important implications on the economic level (among others). Faced with the threat of economic bankruptcy, America will be compelled to close its markets to European and Japanese imports, and the centrifugal tendencies within the bloc will get stronger and stronger. Since the Russian threat will no longer be credible, America's protective umbrella will also lose its justification. Such a situation will give rise to claims for independence by Japan and Germany, concretized in a growing trend towards 'every man for himself', each power trying to protect its own privileged markets in the face of the open recession which will impose itself with irresistible force.

The two planks which guaranteed the supremacy of the dollar, America's economic and imperialist strength, are being eroded. The solvency of the dollar was guaranteed more by the dominant imperialist role of the USA than by its economic strength. The value of the dollar is in fact largely fictitious, based on the 'confidence' inspired by the USA, and this 'confidence' will more and more be shaken by world events. Within the perspective of the development of the crisis, what's at stake is the dollar's hegemonic role on the international scene, and thus its future solvency. The international financial system, centered round the dollar, is like a house of cards. It threatens to collapse at the least breath of wind, and it's a veritable storm that's brewing.

As long as what's left of US 'growth' provides Europe and Japan with outlets for their production, all the industrialized countries have an interest in maintaining the present status quo, but this situation is provisional. The perspective of the American market's slide into recession means a new contraction of the world market and thus a fall in European and Japanese exports; consequently, recession for them as well. However, the economic situation in these countries isn't as bad as that of the US. They can still have some recourse to credit to preserve a relative stability in their privileged markets - Europe for Germany, and South East Asia for Japan. But this credit can only be based on the growing power of currencies that will challenge the all-powerful dollar: the deutschmark and the yen. And such a policy is no more a way out of the crisis than was Reagan's. It would only express the truly ruined state of the world economy and the bankruptcy of the USA. It would only briefly restrain the development of the crisis and keep illusions going a bit longer, but at a much more limited level than before.

Capitalism can't envisage a crisis without a capitalist solution. It can't accept that its contradictions are insurmountable. It's always looking for new illusions, new mirages to dream about. The convulsions in the east, which hold the prospect of opening up the economies of eastern Europe to the west, are creating the hope that there will be new markets for western commodities, a new shot of oxygen that will allow 'growth' to continue. This hope will be short-lived.

Ten years ago, China raised the same hopes, but the western capitalists were soon disenchanted. Even though China with its billion inhabitants has enormous economic needs, in the logic of capital this doesn't turn these needs into solvent markets. China is a population giant and an economic dwarf.

Economies of the Eastern Countries, 1985 | |||||

| GNP in Bil of $ | Population Millions Inhabitants | GNP per habitant | External debt Bil of $ | Service of debt |

Bulgaria | 36 | 9.0 | 4000 | 8.0 | 27 |

Hungary | 30 | 10.6 | 2800 | 19.4 | 35 |

Poland | 64 | 37.9 | 1700 | 40.6 | 45 |

E Germany | 93 | 16.6 | 5600 | 20.1 | 41 |

Romania | 35 | 23.2 | 1500 | 4.0 | 24 |

Czechoslovakia | 70 | 15.5 | 4500 | 6.8 | 15 |

If today the countries of the east European 'glacis' can hope to free themselves from Russian domination, it's because of the economic collapse of the Russian bloc. Consequently, their devastated economies are similar to those of all the under-developed countries, ie insolvent. When the Berlin Wall was opened, hundreds of thousands of East Germans had ecstasies in front of the packed shop windows in the west, but their own pockets were empty: if they were able to make a few meager purchases, it was essentially thanks to the 100 marks 'generously' handed out by the West German state. In any case, the countries of Eastern Europe (excluding the USSR) had a total GNP of 490 billion dollars in 1987, a bit more than half the GNP of France, which was 880 billion. Such a market, even if it was healthy, couldn't suffice as an outlet for world overproduction, and so make it possible to avoid the plunge into open recession a recession in which the east European countries have been stuck for a number of years.

The solution of credit, the western manna called for by the leaders of the east, in particular Walesa who's become the representative of the interests of the Polish economy, is no solution at all. Given that these economies are in ruin, ravaged by decades of aberrant Stalinist management, the credits needed for an economic 'reconstruction' of ·the eastern countries are beyond the means of the western economies. They'd be investing in a pure loss: we already have the example of Poland, with its 40 billion dollars debt and the persistent bankruptcy of its economy. In fact billions of billions of dollars would be required for the job. In a period when the whole world is drowning in debt; when, faced with the contraction of the market, as competition is becoming more and more acute, a new 'Marshall Plan' is no longer possible. The loans from the west, rather than permitting the industrial development of these countries, have the aim of stabilizing the situation on a day-to-day basis. In such conditions, these western credits are largely symbolic.

At the beginning of the 80s, the underdeveloped countries of the periphery of capitalism the 'third world' slid into irredeemable economic disaster. . At the end of the 80s, it's the turn of the eastern bloc - the 'second world' - to go into economic collapse. The 'first world', the big western industrialized countries, in comparison to the general bankruptcy, still looks like an island of health and wealth. This situation can only reinforce the illusions about 'liberal' and 'democratic' capitalism, and constitutes the basis for the intensive ideological campaigns of the western bloc. However, all the conditions are there for the economic failure of the whole capitalist world, especially its most developed poles, to be exposed to the light of day. Since the mid-80s, through economic 'cheating' and deceptive statistics, the bourgeoisie of the industrialized countries has kept up the illusion of growth. This official lie, which the ruling class itself needs to believe, is reaching its end. Despite all the manipulations they've been subjected to, the economic indices are already translating the deepening economic bankruptcy of capitalism. The illusions about growth, about economic development, are going to tumble sharply, along with the official indices themselves, which will be obliged to reflect the reality of an accentuated descent into recession and the accelerated development of inflation.

The whole basis for the domination of capital is being eaten away by the world economic crisis, whose development may be relatively slow, but is nevertheless ineluctable.

JJ

1 See ‘Credit Isn’t An Eternal Solution’, IR 56

2 See presentation and extracts from the Report on the International Situation for the 8th ICC Congress, IR 59.

3 See ‘The Barbaric Agony of Decadent Capitalism’, IR 57.

4 ‘Leverage Buy-out’: official stock exchange auction to buy a company, usually based on a massive recourse to credit or the acrobatic manipulation of accounts.

Collapse of Stalinism: New difficulties for the proletariat

- 3267 reads

Stalinism has been the spearhead of the most terrible counter-revolution that the proletariat has undergone throughout its history: a counter-revolution which made possible World War II, the greatest slaughter of all times, and which plunged the whole of society into a hitherto unparalleled barbarism. Today, as the economies of the so-called "socialist" countries collapse and with the de facto disappearance of the imperialist bloc dominated by the USSR, Stalinism as a political and economic form of capitalism and as an ideology is in its death-throes. One of the working class' greatest enemies is dying; this will not make life any the easier for it, quite the contrary. As it dies, Stalinism is doing capitalism one last good turn. This is what we propose to demonstrate in the following article.

Stalinism is undoubtedly the most tragic and repulsive episode in human history. Not only does it bear the direct responsibility for the massacre of tens of millions of human beings, not only has it imposed for decades a merciless terror on almost a third of humanity, above all it has shown itself the worst enemy of the communist revolution, in other words of the precondition for the human species' emancipation from the chains of exploitation and oppression, and this in the name of the communist revolution itself. In doing so, it has been responsible for the destruction of class consciousness within the world proletariat during the most terrible counter-revolution of its history.

Stalinism's role in the counter-revolution

Ever since the bourgeoisie first established its political domination over society, it has seen in the proletariat its own worst enemy. During the bourgeois revolution at the end of the 18th century, whose Bicentenary has just been celebrated with great pomp, the capitalist class understood how subversive Baboeuf's ideas were, for example. This was why they sent him to the scaffold, even though at the time his movement could not constitute a real threat to the capitalist state.[1]

The whole history of bourgeois domination is marked by the massacre of workers in order to protect it: the massacre of the Lyon "canuts" in 1831, of the Silesian weavers in 1844, of the Parisian workers in June 1848, of the Communards in 1871, of the 1905 uprising throughout the Russian empire. The bourgeoisie has always been able to find executioners from within its classical political formations to do this kind of job.

But when history inscribed the proletarian revolution on its agenda, then these political parties where not enough to preserve its power. It fell to the traitor parties, parties that the workers themselves had created previously, to shore up the traditional bourgeois parties, or even to take the lead amongst them. These new recruits to the bourgeoisie had a specific role to play; they were indispensable and irreplaceable because their origins and their name gave them the ability to keep the proletariat under their ideological control, in order to sap its consciousness and to draw it under the banners of the enemy class. The greatest feat of the Social-Democracy as a bourgeois party lies not so much in its direct responsibility for the massacre of the Berlin proletariat in January 1919 (when, as War Minister, the Social-Democrat Noske fulfilled his responsibility perfectly as the "bloodhound" of the bourgeoisie, to use his own expression), but in the part it had already played as recruiting sergeant during World War I, and the part it was to play afterwards as an agent of mystification, division and dispersal within the proletariat, against the revolutionary wave which put an end to and followed the War.

It was only possible to enroll the European proletariat under the banner of "national defense", and to unleash the carnage of World War I in the name of the "defense of civilisation", thanks to the betrayal of the opportunist wing which dominated most of the parties of the IInd International. In the same way these parties, which continued to call themselves "socialist" and so preserved a large degree of credit within the working class, played a vital part in maintaining reformist and democratic illusions amongst the workers, which disarmed them and prevented them from following the example given by the Russian workers in 1917.

During this period, the elements and fractions which, come wind come storm, had held high the banner of internationalism and proletarian revolution, regrouped within the communist parties, the sections of the IIIrd International. But in the period that followed, these parties were to play a similar role to that played by the socialist parties. Gangrened from within by opportunism, which spread with the defeat of the world revolution, faithful executors under the leadership of an "International", which having once pushed the revolution vigorously forward was being transformed more and more into a mere diplomatic instrument in the hands of the Russian state as it sought its integration into the bourgeois world, the communist parties went the same way as their predecessors. Like the socialist parties, they were finally completely integrated into the political apparatus of the national capital in their respective countries. As they went, however, they played their part in the defeat of the last outbursts of the post-war revolutionary wave, as in China 1927-28, and above all contributed decisively to the transformation of the defeat of the world revolution into a terrible counter-revolution.

After this defeat - in fact, counter-revolution - the defeat and demoralisation of the proletariat were inevitable. However, the form of this counter-revolution in the USSR itself - not the overthrow of the power that had emerged from the Revolution of October 1917, but the degeneration of the state and party that held power - meant that it was incomparably longer and deeper than it would have been had the revolution succumbed to the white armies. Following its integration into the post-revolutionary state, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was converted from the vanguard of the 1917 proletarian revolution and of the Communist International of 1919, to the main agent of counter-revolution in the USSR and the principal executioner of the working class.[2]

But the aura of prestige surrounding its past revolutionary action, continued to maintain the illusion amongst the majority of the communist parties and their militants, as among the great masses of the world proletariat. Thanks to this prestige, some of which was reflected on the Communist Parties in other countries, the militants and the masses were able to tolerate all Stalinism's betrayals during this period. The desertion of proletarian internationalism under the pretext of "building socialism in one country", the identification of "socialism" with the capitalism which was reconstituted in the USSR in its most barbaric forms, the struggles of the world proletariat's subjection to the demands of the defense of the "socialist fatherland", and in the end of the defense of "democracy" against fascism, were so many lies which deceived the working masses largely because the parties which lived by them, presented themselves as the "legitimate" heirs of the October revolution, which they themselves had assassinated.

This identification of Stalinism with communism, probably the greatest lie in history and certainly the most repulsive, which has been aided and abetted by every fraction of the world bourgeoisie,[3] was what made it possible for the counter-revolution to reach the depths it did, paralysing several generations of workers, delivering them bound hand and foot to the second imperialist slaughter, and either eliminating altogether or reducing to the state of utterly isolated little groups the communist fractions which had fought against the degeneration of the Communist International and its parties.

During the 1930's especially, it was left to the Stalinist parties to derail onto a bourgeois terrain the anger and combativity of workers brutally hit by the world economic crisis. By its depth and extent, this crisis was the indisputable sign that the capitalist mode of production was historically bankrupt, and so in other circumstances could have been the lever for a new revolutionary wave. But the majority of workers who wanted to head towards just such a perspective remained snared in the meshes of Stalinism, which claimed to represent the tradition of the world revolution. In the name of the defense of the "socialist fatherland" and of anti-fascism, the Stalinist parties systematically drained the period's proletarian struggles of any class content, and converted them into props for bourgeois democracy, when they did not simply become preparations for imperialist war. This was particularly the case with the "Popular Front" episodes in France and Spain, where an enormous workers' combativity was derailed and wiped out by an anti-fascism that claimed to be "working class", peddled essentially by the Stalinists. In Spain the Stalinists showed clearly that even outside the USSR, where they had played the part of executioners for years, they could equal and even surpass their social-democratic masters at the job of massacring the proletariat (see, in particular, their role in suppressing the Barcelona proletariat's uprising in May 1937, described in the article in the International Review n°7).

In terms of the number of victims for which it is directly responsible, Stalinism is every bit as bad as fascism. But its anti-working class role has been far greater, since its crimes have been committed in the name of the communist revolution and the proletariat and so have also provoked a historically unprecedented reversal of working class consciousness.

Whereas at the end of World War I and in the immediate post-war period, when the world-wide revolutionary wave was developing, the Communist parties' impact was directly related to the combativity and consciousness of the entire proletariat, from the 1930's onwards the evolution of their influence has been inversely proportional to class consciousness. At their foundation, the Communist parties' strength was a barometer of the strength of the revolution; once Stalinism had sold them to the bourgeoisie, the strength of these parties, which continued to call themselves "communist" was no more than a measure of the depth of the counter-revolution.

This is why Stalinism has never been more powerful than immediately following World War II. This was the culminating point in the counter-revolution. Thanks in particular to the Stalinists, who had made it possible for the bourgeoisie to unleash yet another imperialist carnage, and whose "resistance" movements were among the best recruiting-sergeants, the Second World War, unlike the First, was not followed by a revolutionary upsurge of the proletariat.

The "Red" Army's[4] occupation of a large part of Europe, and the Stalinists' participation in the "liberation" governments made it possible to silence, either by terror or by mystification, any attempts by the proletariat to struggle on its own class terrain; it was plunged into still deeper disarray than before the war. Far from clearing the ground for the working class (as the Trotskyists claimed to justify their support for the "Resistance"), the Allied victory to which the Stalinists had contributed only increased the proletariat's submission to bourgeois ideology. This supposed victory of "Democracy" and "Civilisation" over fascist barbarism allowed the ruling class to restore the democratic illusion, and belief in a "humane" and "civilised" capitalism. It thus prolonged the night of the counter-revolution by several decades.

Moreover, it is no accident that the end of this counter-revolution, the historic recovery of the class struggle in 1968, coincides with an important weakening of the Stalinist grip throughout the world proletariat, and of the illusions over the nature of the USSR and the anti-fascist mystification. This is particularly clear in the two Western countries with the most powerful "communist" parties, and where the most important struggles of this recovery took place: France and Italy.

How the ruling class uses Stalinism's collapse

This weakening of Stalinism's ideological grip over the working class is largely due to the workers' discovery of what the supposedly "socialist" regimes really are. In the "socialist" countries, the class obviously realised very quickly that Stalinism was one of its worst enemies. The workers' revolts in East Germany 1953, in Poland and Hungary 1956, were proof that workers in these countries no longer had any illusions about Stalinism. These events (along with the Warsaw Pact's military intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968) also helped open the eyes of numbers of workers in the West as to Stalinism's real nature,[5] but not to the same extent as the struggles in Poland during 1970, 1976, and 1980. Because they were much more directly placed on a class terrain, and because they took place at a time of general resurgence of working class combat, they revealed much more clearly to the eyes of workers in the West the real anti-working class nature of the Stalinist regimes. This moreover is why the Stalinist parties in the West took their distances from the repression of the workers' struggles by the "socialist" states.

The collapse of the "socialist" economy highlighted by these workers' struggles also helped to wear down the Stalinist lie. However, as this collapse became more and more obvious, and as the Stalinist lie has faded, the Western bourgeoisie put it to good use by developing campaigns around the theme of "capitalism's superiority to socialism". In the same way, the Polish workers' powerful illusions in democracy and the trade unions, especially following the formation of the "Solidarnosc" union after 1980, have been exploited to the hilt to improve the unions' image in the eyes of workers in the West. The strengthening of these illusions, especially after the repression of December 1981 and the outlawing of "Solidarnosc" goes a long way to explaining the disarray and retreat of the working class at the beginning of the 1980's.

In autumn 1983 the upsurge of a new wave of workers' struggles in the developed Western countries, notably in Western Europe, and their simultaneity on a world scale, demonstrated that the working class was beginning to emerge from the grip of the illusions and mystifications which had paralysed it in the previous period. The weakening of illusions in the trade unions was revealed in strikes such as the 1986 French rail strike, or the 1987 teachers' strike in Italy, where workers acted outside or even against the trade unions; it was also revealed in the way the leftists, in these and some other countries, started setting up the "coordinations": structures of control put forward as "nonunion". During the same period, the rising rate of abstentions, especially in working class constituencies, was a sign of the decline in the electoral mystification. Today however, thanks to the collapse of the Stalinist regimes and the frenzy of accompanying media campaigns, the bourgeoisie has succeeded in reversing this tendency of the mid-1980's.

If the events in Poland during 1980-81 - not the workers' struggles of course, but the union and democratic trap which closed in on them and made possible the repression that followed -allowed the bourgeoisie to create a considerable confusion among the proletariat of the most advanced countries, then today's general and historic collapse of Stalinism can only lead to a still greater disarray.

This is the case because today's events are at an altogether different level from those of Poland in 1980. They are not confined to one country. An entire imperialist bloc is involved, starting with its most important country, the USSR. Stalinist propaganda could present the difficulties of the Polish regime as being due to Gierek's "mistakes". Nobody today, not even these countries' new leaders, is trying to lay all the blame for today's difficulties on the fallen leaders of the past. According to many of these leaders, especially the Hungarians, what is in question today is the entire economic structure and the aberrant political practices which have marked the Stalinist regimes from their outset. The fact that their leaders recognise these regimes' total collapse is obviously all grist to the mill for the Western bourgeoisie's media campaigns.

The bourgeoisie also gets maximum mileage from the collapse of Stalinism and its bloc because this collapse is not due to the action of the class struggle, but to the complete bankruptcy of these countries' economies. In the colossal events taking place today in Eastern Europe, the proletariat as a class, with a policy antagonistic to capitalism, is painfully absent.

In particular, last summer's miners' strikes in the USSR were something of an exception; the weight of illusions they harboured reveal the proletariat's political weakness in these countries. Moreover, unlike the miners' strikes, most of the strikes which have occurred recently in the USSR were not aimed at defending workers' interests, but were situated on a nationalist and so completely bourgeois terrain (Baltic countries, Armenia, Azerbaijan...). Not a shadow of a working class demand is to be seen in the massive demonstrations taking place in Eastern Europe, in particular in East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria. These demonstrations are completely dominated by typically and wholly bourgeois democratic demands: "free elections", "liberty", "resignation of the ruling CP's", etc. By comparison, the impact of the democratic campaigns that followed Poland 1980-81 was somewhat limited by the fact that these events sprang from the class struggle. The absence of significant class struggle in the Eastern countries today cannot but strengthen the devastating effects of the bourgeoisie's present campaigns.

On the more general scale of the collapse of an entire imperialist bloc, which will have enormous repercussions, the fact that this historic event has taken place independently of the proletariat's own action cannot help but produce within the class a feeling of powerlessness, even if the event was only possible, as the Theses demonstrate, because up to now the bourgeoisie has been unable to enroll the proletariat on a world level for a third imperialist holocaust. After overthrowing first the Tsar and then the bourgeoisie in Russia, it was the class struggle which put an end to World War I by bringing about the collapse of Imperial Germany. This is the main reason that the first revolutionary wave could develop on a world scale.

By contrast, the fact that the class struggle was only of secondary importance in the collapse of the Axis countries after World War II played an important part in paralysing and disorientating the proletariat in its immediate aftermath. Today, it is not irrelevant that the Eastern bloc should be collapsing under the weight of the economic crisis, rather than under the blows of the class struggle. If the latter had happened, it could only have strengthened the proletariat's self-confidence, not weakened it as is the case today. Moreover, to the extent that the collapse of the Eastern bloc comes after the period of "cold war" with the West, which the latter seems to have "won" without striking a blow, it will create a feeling of euphoria amongst the populations in the West, including the workers, and a feeling of confidence in their governments similar (though to a lesser degree) to that which weighed on the proletariat in the "victorious" countries after the two world wars, and which was even one of the main causes of the defeat of the revolutionary wave following the First.

Clearly, this kind of euphoria, which is obviously catastrophic for the consciousness of the working class, will be much more limited today, since the world is not just emerging from an imperialist bloodbath. However, the damage will be made more severe by the euphoria infecting the population in some of the Eastern countries, and which will have its impact in the West. At the opening of the Berlin Wall, for example, the press and certain politicians compared the atmosphere in Berlin with that of the "Liberation" following World War II. It is no surprise that the population of East Germany should feel the same about the demolition of this symbol par excellence of Stalinist terror as did the populations subjected to years of occupation and terror by Nazi Germany. But history has shown us that this kind of emotion is one of the worst obstacles to the development of proletarian consciousness.

The East European population's satisfaction at the collapse of Stalinism, and above all the increase in democratic illusions that it will make possible, is already having a strong effect on the proletariat in the Western countries, especially in Germany whose weight within the world proletariat is especially important in the perspective of the proletarian revolution. Moreover, even if the reunification of Germany is not an immediate practical possibility, the proletariat in Germany will have to confront all the nationalist lies that this perspective cannot but reinforce.

These nationalist mystifications are already very strong amongst workers in most of the Eastern countries. They do not exist only within the different republics that make up the USSR. They also weigh heavily on the workers in the "people's democracies", due notably to the brutal manner whereby the "Big Brother" kept his imperialist grip on them. These mystifications have been reinforced by the Russian tanks' bloody interventions in East Germany 1953, in Hungary 1956, and in Czechoslovakia 1968, and by the decades of systematic pillage of the satellite countries' economies. Along with illusions in democracy and trade unions, these played an important part in disorientating the Polish workers in 1980-81, opening the door to the repression of December. They will gain new energy with the disintegration of the Eastern bloc which will make the development of the workers' consciousness still more difficult.

These nationalist mystifications will also weigh on the workers in the West; this will not (apart from in Germany) occur through a direct increase in nationalism amongst the working class, but rather through the discredit and distortion of the very idea of proletarian internationalism. This conception has already been completely disfigured by Stalinism, and in Stalinism's wake by the rest of the bourgeoisie, which identified it with the USSR's domination of its bloc. In 1968, the intervention of the Warsaw Pact's tanks in Czechoslovakia was carried out in the name of "proletarian internationalism". The Eastern bloc's collapse, and its population's rejection of Stalinist style "internationalism", will inevitably weigh heavily on the consciousness of workers in the West.

And the Western bourgeoisie will miss no opportunity to oppose real proletarian internationalism with its own "international solidarity', understood as support for the stricken Eastern economies (or simply appeals for charity), or for their populations' "democratic demands" when they come up against brutal repression (remember the campaigns over Poland in 81, or more recently over China).

In fact, the ultimate aim at the heart of the bourgeoisie's present campaigns to taint the very perspective of world communist revolution with the collapse of Stalinism. Internationalism is only one element of this perspective. The nauseating refrain of the media: "communism is bankrupt; communism is dead" sums up the fundamental message that the ruling class in every country wants to stuff into workers' heads. The lie of the identity between Stalinism and communism, which has already been peddled by all the forces of the bourgeoisie in the past during the worst moments of the counter-revolution, has once again been taken up with the same unanimity. In the 1930's, the bourgeoisie used it to enroll the working class behind Stalinism and to complete its defeat. Today, now that Stalinism has lost all its credit in workers' eyes, the same lie is being used to turn them away from the perspective of communism.

In the Eastern bloc, the workers have already suffered this disorientation for some time: when the term "dictatorship of the proletariat" means police terror, when "the power of the working class" means the cynical power of the bureaucrats, when "socialism" means brutal exploitation, shortages, poverty and waste, when school children are forced to learn by heart quotes from Marx and Lenin, inevitably they will turn away from such notions, in other words reject what is the very foundation of the proletariat's historical perspective, refuse categorically to study the basic texts of the workers' movement; the very terms "workers' movement" and "working class" become obscenities. In such a context, the very idea of a proletarian revolution is completely discredited. "What is the use of starting again as in October 1917, if it only ends up in Stalinist barbarity?"This is the dominant feeling today amongst virtually all the workers in the Eastern countries. The Western bourgeoisie aims to profit from the collapse of Stalinism to spread a similar confusion among the workers in the 'West. And so obvious and spectacular is the system's collapse that for the most part, this works.

All the events which are rocking Eastern Europe today, and whose repercussions are world-wide, will thus for a time weigh heavily, and negatively, on the development of consciousness in the working class. At first, the opening of the "iron curtain" which divided the world proletariat in two will not permit the workers in the West to help their class brothers in the East profit from the experience they have gained in their struggles against the traps and mystifications deployed by the world's strongest bourgeoisies. On the contrary, in the immediate and for some time to come, it will be the strong democratic illusions of the workers in the East that will spill over into the West, thus weakening the gains made already by the workers there. This is how the bourgeoisie is using against the working class the death agony of Stalinism, which was once the weapon par excellence of the counter-revolution.

The perspectives for the class struggle

In a world context of deepening capitalist crisis, the collapse of the Stalinist regimes, essentially as a result of their total economic bankruptcy, can only make their situation worse. For the working class in these countries, this means unprecedented attacks and poverty, even famine. This situation will inevitably provoke explosions of anger. But the political and ideological context is such in the East, that it will be some time before the workers' combativity can lead to a real development of consciousness (see the article in this issue of the International Review). Developing chaos and convulsions on the economic and political level, the barbarity and decomposition of capitalist society which appears almost in caricatural form in the East, will not lead to an understanding of the need to overthrow the system until such an understanding has developed among the decisive proletarian battalions in the great working class concentrations of the West, and especially in Western Europe.[6]

As we have seen, at present these sectors of the world proletariat are themselves being subjected to a flood of bourgeois propaganda, and are being affected by a retreat of consciousness. This does not mean that they will be incapable of fighting back against the economic attacks of capitalism's irreversible crisis. What this means above all is that for a while at least, these struggles will be much more the prisoners of the state's organs for controlling the working class, with the trade unions to the fore, than they have been recently; this is already visible in the most recent combats. In particular, the unions will benefit from the general reinforcement of democratic illusions. They will also find easier ground for their maneuvers with the development of reformist ideology, as a result of the strengthening illusions as to "capitalism's superiority" over any other form of society.

However, the proletariat today is not the same as in the 1930's. It is not emerging from a defeat like that of the revolutionary wave that followed World War I. The world capitalist crisis is insoluble. It can only go on getting worse (see the article on the crisis in this issue): after the collapse of the "Third World" countries during the 1970's, and the implosion of the so-called "socialist" economies today, the next on the list will be the more developed countries which up to now have been able to push the system's worst convulsions out to the periphery. The inevitable revelation of the utter bankruptcy, not of any one sector of capitalism but of the entire mode of production, cannot but undermine the very bases of the Western bourgeoisie's campaigns about "capitalism's superiority".

In the end, the development of the workers' combativity will open out into a new development of their consciousness, which today is being interrupted and counter-acted by Stalinism's collapse. It is down to the revolutionary organisations to contribute determinedly to this development, not by trying to console the workers, but by showing them clearly that however difficult it may be, the proletariat can take no other road than the one that leads to the communist revolution.

FM 25/11/89

[1] It is significant that the "revolutionary" and "democratic" French bourgeoisie had no hesitation in sweeping aside the "Declaration of the Rights of Man" which they had just adopted (and which they make so much fuss about today), by outlawing all workers' associations (the Le Chapelier law of 14 June 1791). This ban was only lifted almost a century later, in 1884.

[2] The degeneration and betrayal of the Bolshevik party did not go unresisted, both by the working class, and within the party itself. In particular, Stalinism wiped out all the leaders of October 1917, and most of the militants. See, on this question, the articles on "The degeneration of the Russian revolution" and on "The Communist Left in Russia", in International Review n°3, and n°8-9.

[3] In the late 20's and throughout the 30's, the "democratic" bourgeoisie in the West was far from showing the same revulsion for "barbaric" and "totalitarian" Stalinism as it did during the Cold War and still does today. It gave unfailing support to Stalin in his persecution of the "Left Opposition", and its principal leader Trotsky, for whom the world became a "planet without a visa" after his expulsion from the USSR in 1928. "Democrats" all over the world, starting with the Social-Democrats in power in Germany, Britain, Norway, Sweden Belgium and France demonstrated their disgusting hypocrisy by setting aside their "fine principles" such as the "right" of asylum, as far as Trotsky was concerned. All these fine people found very little to protest about during the Moscow trials when Stalin liquidated the Bolshevik Party's old guard, accusing them of "Hitlero-Trotskyism"; they were even abject enough to spread it about that "there is no smoke without fire".

[4] A further proof, if one were needed, that the regimes set up in Eastern Europe following World War II (as of course, the regime then existing in the USSR itself) have nothing to do with the power established in Russia in 1917, lies in the part played in their origins by the imperialist war. The working class nature of the October revolution is illustrated by the fact that it arose against the imperialist war. The anti-working class and capitalist nature of the "people's democracies" is demonstrated by the fact that they were set up thanks to the imperialist war.

[5] This is obviously not the only factor that allows us to explain Stalinism's waning impact within the working class, any more than that of bourgeois mystifications as a whole, between the end of the war and proletariat's historic resurgence at the end of the 1960's. In many countries, moreover (especially in Northern Europe), since World War II Stalinism has no longer played anything but a secondary role in controlling the workers, when compared with Social-Democracy. The weakening of the anti-fascist mystification, for lack of a "fascist" scarecrow in most countries, and the waning influence of the trade unions (whether Social-Democratic or Stalinist) after all their work in sabotaging the struggle during the 60's, also allows us to explain the diminishing impact of both Stalinism and Social-Democracy on the proletariat. This is why the latter was able to reappear on the scene of history as soon as the first attacks of the open crisis fell.

[6] See our analysis in "The proletariat of Western Europe at the centre of the generalisation of the class struggle" in International Review n°31.

Historic events:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Collapse of the Eastern Bloc: The definitive bankruptcy of Stalinism

- 9189 reads

Presentation to the Theses on the Economic and Political Crisis in the USSR and the Eastern Countries

The "Theses" published in this issue were adopted at the beginning of October 1989. Since then, events in the East have rushed ahead, telescoping into each other week after week, leading to situations which would have seemed inconceivable only 6 months ago. Hardly has August, which saw the trade union (!) Solidarnosc leaping from clandestinity to head the government, drawn to a close than Eastern Europe is shaken by other events of great historical importance.

Hungary, whose "communist" party has changed its name and declared its desire to become social-democratic, has thrown the, cloak of "people's democracy" and its membership of the "socialist" camp into the dustbin of history, to become a plain republic. This year in East Germany, supposedly the most stalwart member of the Eastern bloc, more than 100,000 people belonging to the most qualified sectors of the workforce, have abandoned "real socialism" for West Germany; nonetheless, increasingly massive demonstrations are developing in every city, demanding pell-mell free elections, the legalisation of the opposition, and the freedom to travel. Honecker has been forced to resign, to be definitively expelled only a few weeks later from a party which has been forced to renounce its role of exclusive leadership and to open the Berlin Wall, the symbol of the strengthening in 1961 of the division decided at Yalta in 1944. In Bulgaria, then in Czechoslovakia, the regimes inherited from Stalinism are also collapsing. This acceleration of the situation, these convulsions generalising throughout the Eastern countries, confirm the framework set out in the Theses as to Stalinism's historic crisis and its roots. Moreover, the speed with which events are moving means that what was then only a perspective is now a reality: the definitive collapse of Stalinism and the complete disintegration of the Eastern bloc, to the point of becoming a fiction fit only for the dustbin of history.

This situation, where the USSR and Eastern Europe no longer form an imperialist bloc, is the most important historical turning point since World War II and the historic resurgence of proletarian combat at the end of the 60's, both on the imperialist level (all the imperialist groupings that emerged from the Yalta agreements will be seriously destabilised), and on the level of what remains more than ever the only alternative to the decomposition, barbarity, and growing chaos provoked by the historic crisis of the capitalist system on a world level: the proletarian struggle.

The bankruptcy of Stalinism: a crisis of capitalism, not of communism

The Theses develop at some length what lies at the roots of this bankruptcy:

- the overall, worldwide crisis of the capitalist mode of production;

- the failure of the extreme, caricatural form of state capitalism represented by Stalinism, which was both a factor in, and a product of the counter-revolution in Russia.

This aberrant nature of Stalinism has only increased the difficulties of already weak and backward national capitals in confronting the crisis and the consequent exacerbation of competition on the already over-saturated world market. We will not here go any further into the roots of Stalinism and the Eastern bloc's definitive collapse; rather, we will aim to bring its evolution up to date.

Recent events have been the occasion for a barrage of lies, and in the lead the biggest and vilest of them: the claim that this crisis represents the failure of communism, and of marxism! Over and above their various antagonisms, democrats and Stalinists have always formed a holy alliance in saying to the workers that socialism (however deformed) reigns in the East. For Marx, Engels, Lenin, Luxemburg, for the entire marxist movement, communism has always meant the end of the exploitation of man by man, the end of classes, the end of frontiers, all made possible only on a world scale, in a society governed by the abundance of "from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs", where "the government of men gives way to the administration of things". The claim that there is anything "communist", or even approaching "communism", in the USSR and the countries of the Eastern bloc, ruled by exploitation, poverty, and generalised scarcity, is the greatest lie in the history of humanity.

In the East, the Stalinists have only been able to impose this lie by means of the most brutal terror. "Socialism in one country" was set up and defended at the price of an appalling and bloody counter-revolution, which first systematically liquidated everything that remained of October 1917 and above all of the Bolshevik Party in Stalin's jails, before subjecting tens of millions of human beings to deportation and death. This ferocious dictatorship, this hideous concentrate of the worst barbarity of decadent capitalism, owes its existence to two weapons only: terror, and the lie.

This lie is an important asset to all the fractions of the bourgeoisie faced with the nightmare "specter of communism", the threat posed to their domination by the proletarian revolution. The revolution of October 1917 in Russia, and the world revolutionary wave that followed it up until the 1920's has been up to now the only point in history where the proletariat has overthrown (in Russia 1917), or really threatened (Germany in 1919), bourgeois rule. Since then the ability to identify the proletarian revolution of October with its own executioner, the Stalinist counter-revolution has been a major advantage for all our fine "democrats" in defending bourgeois order. For several decades, the proletariat's positive identification, thanks to the immense prestige of October, of the revolution with Stalinism, communism with the Eastern bloc, was the most powerful ideological factor responsible for its continued powerlessness. This was how it was led to the slaughter in World War II, precisely in the name of the defense of the "socialist" camp, allied for the occasion to the "democratic" camp against fascism, after being allied to Hitler at the beginning of the war. The proletariat has never been as weak as when the Stalinists were strong, and still crowned with the halo of Red October. But as this belief in the supposedly socialist nature of the USSR crumbled under the blows of the recovery of class struggle in both East and West following 1968, to the point of a deep-seated rejection of Stalinism throughout the proletariat, it was still more vital for the "democracies" to keep alive the monstrous fiction of "socialism" in the East. As the spur of the renewed open capitalist crisis, on a world scale, pushed the workers to enlarge and strengthen their combat against the bourgeoisie and its system, as more and more the question was posed of what perspective the working class should give to its combat, the bourgeoisie had absolutely to avoid any encouragement of the revolutionary perspective within the proletariat by the exposure of history's greatest lie: the identification between Stalinism and communism.

This is why it is more than ever important for the ruling class to keep up this fiction. After being used "positively", this monstrous association between "revolution" and "Stalinism" is now being used negatively, to create disgust for any idea of a revolutionary perspective. At the very moment when, for the whole of humanity, the historic alternative between socialism and endless barbarism is being posed more and more sharply, it is vital for the bourgeoisie to discredit the communist perspective in the workers' eyes as much as it can.

This is why, as Stalinism collapses for good, the "democrats" are redoubling their efforts to keep this disgusting lie alive: "October 1917 = Stalinism", "marxism = Stalinism", "USSR = communism". There are no bounds to the cynicism of the ruling class, as it displays the pictures of tens of thousands of workers fleeing from "socialism" to get to the countries of "abundance and liberty" that the Western capitalist "democracies" are supposed to be. The aim is to discredit in the workers' eyes any perspective for a society other than that based on profit and the exploitation of man by man. "Democracy" is supposed to be, if not the best system, at least the "least bad" system. Finally, and this is a real danger, the ruling class is trying to draw the workers in the East into fighting for interests that are not their own, to join the struggle between the cliques of "reformers" and Stalinists - Gorbachev and Yeltsin against Ligachev in the USSR, "New Forum" against SED in East Germany, etc -- not to mention between the different "nationalities".

Every time that the working class has fallen into this kind of trap, it has ended up not only gaining nothing, but being massacred, as it was in the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War, for the mirage of the bourgeois "republic". In reality, Stalinists and "democrats", Stalinists and "anti-Stalinists" are nothing but two facets of a same face: the face of bourgeois dictatorship. We should remember that during World War II, the British and American "democracies" had no compunction in allying themselves with Stalin against Germany. Their opposition since then, which has led to the world's division into two antagonistic spheres of influence, does not spring from an ideological opposition, between a "socialist" and a capitalist bloc. It is the expression of two capitalist and imperialist blocs which have become rivals.

Only when the USSR took advantage of the collapse of German imperialism to transform its inherited European sphere of influence into an imperialist bloc did the "democracies" suddenly discover that they had a duty to oppose this "totalitarian", "communist" system. Before the war, the USSR was only an isolated second-rate power; then, it was possible to ally with this same "totalitarian and communist" system. This was no longer the case in the 50's, now that the USSR had become a first-order imperialist power, and therefore a serious imperialist rival!

This is why, while the proletariat must reject with disgust Stalinism and the Stalinists, it must also reject the camp of the "democrats" and "anti-Stalinists". There is nothing to choose between them; if the proletariat does so, then it can only abandon its class terrain and become the hostage and powerless victim, in a struggle which is nothing to do with it, of the two capitalist hangmen of the proletarian revolution: Stalinism, and "democracy".

Never forget, that it was the Social-Democracy which crushed the revolution in Germany in 1919 and 1923, condemning the Russian revolution to a terrible isolation, and so opening the way to Stalinism and fascism.

The end of the Russian imperialist bloc, the end of Yalta: towards worldwide chaos

Stalinism's collapse cannot but provoke profound and widespread convulsions, to the point where they create a situation of veritable chaos in what was up to now the world's second imperialist power.

Day by day, the bourgeoisie is losing control of events.

The trade union Solidarnosc joins the Polish government, with the declared aim of "liberalising the economy" and "drawing closer" to the West; unable to prevent it, Moscow pretends to encourage the move.

The Stalinist party in power in Hungary changes its name, proclaims itself social-democratic, and demands neutral status for the country, as well as membership of the Council of Europe, one of the West's most important organisms. This comes down to leaving the Warsaw Pact: Gorbachev sends a telegram of congratulations.

In Bulgaria, in Czechoslovakia, in East Germany, the old Stalinists are pushed aside. East Germany opens its frontiers, and hundreds of thousands of people rush to escape.

Everywhere (except in Romania at the time of writing), changes are happening daily, any one of which, only a few years ago, would have brought in the Russian tanks. This is not as it is generally presented, the result of a deliberate policy on Gorbachev's part, but the sign of a general crisis throughout the bloc, at the same time as Stalinism's historic bankruptcy. The rapidity of events, and the fact that they are now hitting East Germany, the central pillar of the Eastern bloc, is the surest sign that the world's second imperialist bloc has completely disintegrated.

This change is by now irreversible, and affects not just the bloc, but its leading power, the USSR itself. The clearest sign of Russia's collapse is the development of nationalism in the form of demands for "autonomy" and "independence" in the peripheral regions of central Asia, on the Baltic coast, and also in a region as vital for the Soviet national economy as the Ukraine.

Now when the leader of an imperialist bloc is no longer able to maintain the bloc's cohesion, or even to maintain order within its own frontiers, it loses its status as a world power. The USSR and its bloc are no longer at the centre of the inter-imperialist antagonisms between two capitalist camps, which is the ultimate level of polarisation that imperialism can reach on a world scale in the era of capitalist decadence.

The disintegration of the Eastern bloc, its disappearance as a major consideration in inter-imperialist conflict, implies a radical calling into question of the Yalta agreements, and the spread of instability to all the imperialist constellations formed on that basis, including the Western bloc which the USA has dominated for the last 40 years. This in its turn will find its foundations called into question. During the 1980's, the cohesion of the Western countries against the Russian bloc was an important factor in the latter's collapse; today, the cement for that cohesion no longer exists. Although it is impossible to foresee exactly the rhythm and forms that this will take, the perspective today is one of growing tension between the great powers of the Western bloc, the eventual reconstitution of two new imperialist blocs at an international level, and in the absence of any proletarian response a new worldwide massacre. The definitive collapse of Stalinism, and its corollary, the disintegration of the Eastern imperialist bloc, are thus already pregnant with the destabilisation of all the imperialist groupings that emerged from Yalta.

The calling into question of the imperialist' order inherited from World War II, and the fact that the formation of two new imperialist camps will inevitably take time, does not at all mean the disappearance of imperialist tensions. The generalised crisis of the capitalist mode of production can only push all countries, both great and small, and within them the different fractions of the ruling class, to try to settle their differences on the battlefield. The Lebanon, Afghanistan, Cambodia, El Salvador, etc are still torn by war today. Far from encouraging peace, the disintegration of the blocs which emerged from Yalta, and the decomposition of the capitalist system which underlies it, implies still more tension and conflicts. The appetites of the minor imperialisms, which up to now have been determined by the world's division into two major camps, will only increase, now that these camps are no longer dominated by their leaders as before.

Stalinism is not dying a peaceful death, giving way to other "democratic" forms of bourgeois dictatorship. There will be chaos, not a "soft" transition. As the Stalinist carcass rots, the whole Eastern bloc is threatened with "Lebanonisation". The confrontations between rival cliques of bourgeois nationalists in the USSR itself, the tensions between Hungary and Romania, East Germany and Czechoslovakia, Romania and the USSR, East Germany and Poland, etc, the beginnings of pogroms that we are witnessing today in Moldavia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, open a perspective of generalised decomposition, a concentrated form of all the barbarity of decadent capitalism.

Implications for the proletariat of the Eastern Bloc's general decomposition

Behind the reforms, the democratisation, the attempts to liberalise the economy, behind all the fine speeches about the "radiant future", the reality for the workers is already a serious decline in their already difficult living conditions. In Poland and the USSR, everything is in short supply; even in Moscow and Leningrad, which are traditionally better stocked, such staples as sugar and soap have become almost impossible to find. More and more articles are rationed, and the rations are diminishing. The winter will be extremely hard: the measures of liberalisation decided in Poland and Hungary, and begun in the USSR, mean that scarcity will continue and that the black market will become inaccessible for the workers, since the rate of inflation is moving towards three figures, as in Poland, and the ending of price controls affects staple products first of all. The liberalisation of the economy, and its corollary, autonomy for individual enterprises will mean the appearance and growth of mass unemployment. The extent of this unemployment can be measured if we consider that in Poland one third of all workers will be made redundant if non-profitable companies are forced to close (according to the Solidarnosc government's own economic experts).

In the USSR, where there are already in reality several million unemployed, between 11 and 12 million workers will have to be made redundant in the next five years. More than half the factories in Hungary should be closed because they are obsolete and uncompetitive! What the immediate future holds in store for the proletariat in the East is thus a terrible poverty, comparable to that in "Third World" countries.

Faced with these attacks, the proletariat will fight, and will try to resist, like for example the Siberian miners, who have gone back on strike to demand that the government respect the agreements negotiated after the strikes this summer. There are, and there will be, more strikes. But the question is: what will be the context in which these strikes occur? There can be no ambiguity as to the reply: one of extreme confusion due to the Eastern working class' political weakness and inexperience, which will make the workers especially vulnerable to the mystifications of democracy and trade unions, and to the poison of nationalism. We can see this already in Poland and Hungary, or in the USSR where Russian workers are striking against Baltic workers and vice versa, or in the struggles between Azeris and Armenians.