World Revolution 2011

- 5768 reads

World Revolution no.341, February 2011

- 3030 reads

Uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt: The best solidarity is class struggle

- 3482 reads

The thunder in Tunisia and Egypt is being echoed in Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Gaza, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen. Whatever flags the demonstrators carry, all these protests have their root in the world wide crisis of capitalism and its direct consequences: unemployment, rising prices, austerity, and the repression and corruption of the governments who preside over these brutal attacks on living standards. In short, they have the same origins as the revolt of Greek youth against police repression in 2008, the struggle against pension ‘reforms’ in France, the student rebellions in Italy and Britain, and workers’ strikes from Bangladesh to China and from Spain to the USA.

The thunder in Tunisia and Egypt is being echoed in Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Gaza, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen. Whatever flags the demonstrators carry, all these protests have their root in the world wide crisis of capitalism and its direct consequences: unemployment, rising prices, austerity, and the repression and corruption of the governments who preside over these brutal attacks on living standards. In short, they have the same origins as the revolt of Greek youth against police repression in 2008, the struggle against pension ‘reforms’ in France, the student rebellions in Italy and Britain, and workers’ strikes from Bangladesh to China and from Spain to the USA.

The determination, courage and sense of solidarity being displayed in the streets of Tunis, Cairo, Alexandria and many other cities are a true inspiration. The masses occupying Tahrir Square in Cairo or similar public places have fed themselves, fought off attacks by pro-regime thugs and the police, called the soldiers to fraternise with them, nursed their wounded, openly rejected sectarian divisions between Muslim and Christian, between the religious and the secular. In the neighbourhoods they have formed committees to protect their homes from looters manipulated by the police. Tens of thousands have effectively been on strike for days and even weeks in order to swell the ranks of the demonstrations.

Faced with this spectre of massive revolt, with the nightmare prospect of its extension across the ‘Arab world’ and even beyond, the ruling class all over the world has been responding with its two trustiest weapons: repression and mystification. In Tunisia, scores were gunned down in the streets, but now the ruling class proclaims the beginning of a transition to democracy; in Egypt, the Mubarak regime alternates between beating, shooting, gassing and running down protestors and issuing similar vague promises. In Gaza, Hamas arrests demonstrators trying to show solidarity with the revolts in Tunisia and Egypt; on the West Bank the PLO has banned “unlicensed gatherings” called to support the uprisings; and in Iraq protests against unemployment and shortages are fired on by the regime installed by the US and British ‘liberators’. In Algeria, after stifling the first signs of revolt, concessions are made legalising timid forms of protest; in Jordan the King sacks his government.

Internationally, the capitalist class also alternates its language: some – especially those on the right, and of course the rulers of Israel – openly support Mubarak’s regime as the only bulwark against an Islamist takeover. But the key note is given by Obama: after some initial hesitations, the message is that Mubarak must go and go quickly. The ‘transition to democracy’ is put forward as the only way forward for the downtrodden masses of North Africa and the Middle East.

The dangers facing the movement

The mass movement centred in Egypt thus faces two dangers. One is that the spirit of revolt will be drowned in blood. It seems that the initial attempts by the Mubarak regime to save itself with the iron fist have been stymied: first the police had to withdraw from the streets in the face of the massive demonstrations, and the unleashing of the pro-Mubarak thugs last week has also failed to sap the demonstrators’ will to continue. In both rounds of confrontation, the army has presented itself as a ‘neutral’ force, even as being on the side of the anti-Mubarak gatherings and protecting them from assaults by the regime’s defenders. There is no doubt that many of the soldiers sympathise with the protests and would not be willing to fire on the masses in the streets; some have already deserted. Higher up in the army, there are certainly factions that want Mubarak to go now. But the army of the capitalist state is not a neutral force. Its ‘protection’ of Tahrir Square is a also a form of containment, a huge kettle; and when push comes to shove, the army will indeed be used against the exploited population, unless the latter succeeds in winning over the rank and file soldiers and effectively dissolving the army as an organised part of the state power.

But here we come to the second great danger facing the movement: the danger that resides in its widespread illusions in democracy. The belief that the state can, perhaps after a few reforms, be made to serve the people; the belief that ‘all Egyptians’, perhaps with the exception of a few corrupt individuals, have the same basic interests. The belief in the neutrality of the army. The belief that the terrible poverty facing the majority of the population can be overcome if there is a functioning parliament and an end to the arbitrary rule of a Ben Ali or a Mubarak.

These illusions, expressed everyday by the demonstrators’ own words and banners, disarm the real movement for emancipation, which can only advance as a movement of the working class fighting for its own interests, which are distinct from those of other social strata, and which are above all diametrically opposed to the interest of the bourgeoisie and all its parties and factions. The innumerable expressions of solidarity and self-organisation that we have seen so far already reflect the genuinely proletarian element in the current social revolts; and, as many of the protestors have already said, they presage a new and more human society. But this new and better society cannot be brought about through parliamentary elections, through putting el Baradei or the Muslim Brotherhood or any other bourgeois faction at the head of the state. These factions, who may be carried to power by the strength of the masses’ illusions, will not hesitate to use repression against these same masses later on.

There is much talk about ‘revolution’ in Tunisia and Egypt, both from the mainstream media and the extreme left. But the only revolution that makes sense today is the proletarian revolution, because we are living in an era in which capitalism, democratic or dictatorial, quite plainly can offer nothing to humanity. Such a revolution can only succeed on an international scale, breaking through all national borders and overthrowing all nation states. Today’s class struggles and mass revolts are certainly stepping stones on the way to such a revolution, but they face all kinds of obstacles on the road; and to reach the goal of revolution, profound changes in the political organisation and consciousness of millions of people have yet to take place.

In a way, the situation in Egypt today is a summation of the historic situation facing humanity as a whole. Capitalism is in terminal decline. The ruling class can offer no perspective for the future of the planet; but the exploited class is not yet aware of its own power, its own perspectives, its own programme for the transformation of society. The ultimate danger is that this temporary stalemate will end in “the mutual ruin of the contending classes”, as the Communist Manifesto put it – in a plunge into chaos and destruction. But the working class, the proletariat, will only discover its real power through engaging in real struggles, and this is why what is now taking place in North Africa and the Middle East is, for all the weaknesses and illusions that hamper it, a real beacon for workers everywhere.

And above all it is a call to the proletarians of the more developed countries, who are also beginning to return to the road of resistance, to take the next step, to express their practical solidarity with the masses of the ‘third world’ by escalating their own combat against austerity and impoverishment, and in doing so exposing all the lies about capitalist freedom and democracy, of which they have a long and bitter experience.

Recent and ongoing:

Rubric:

The attacks are not ideological: capitalism really is bankrupt

- 2626 reads

This is the leaflet we distributed on the demonstrations against education cuts on 29 January.

But the crisis isn’t confined to Britain. The sovereign debt crisis (i.e. investors beginning to lose faith in government bonds) continues to rumble on in Europe. Ireland has already been forced to adopt yet another austerity budget and growing political instability. Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain, and Belgium are also facing serious difficulties that continue to undermine the Euro-area. As for China, some investment banks (e.g. Goldman Sachs) and hedge funds are already starting to reduce their exposure, amid worries that the Chinese miracle may turn out to be the biggest bubble of them all.

The crisis is thus clearly embedded in the capitalist system on a global scale. It is not the product of this or that government’s policy but the result of the economic mechanisms of capitalism itself, over which even the most competent government has limited control. Contrary to capitalist ideology (and that includes the so-called ‘left’), the recession was not caused by ‘greedy bankers’ or ‘neo-liberal’ economic policies. These elements are no more than consequences of far deeper structural issues at the heart of the economy.

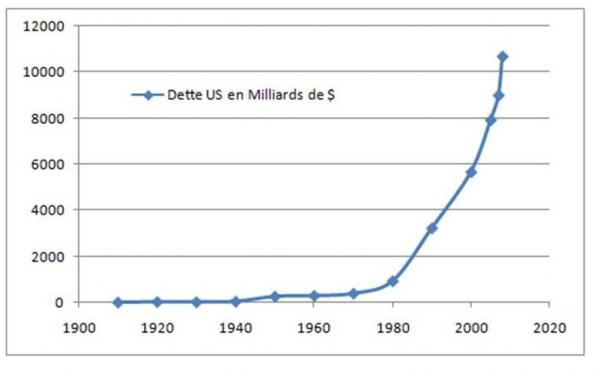

The financial crisis and accompanying recession is not a new problem that has suddenly appeared over the last few years. Their roots can be traced at least as far back as the Great Depression of the 1930s. In the 70s, mainly left-wing governments employed the Keynesian policies that successfully held off recession during the post-war boom. However, these were finally shipwrecked on the cliffs of enormous budget deficits, inflation and recession.

In the 80s, the era of ‘Reaganomics’ and ‘Thatcherism’ there were the brutal recessions of 1981 and 1990. The ‘third way’ popularised especially by Blair and Clinton in the 90s was punctuated by the Mexican ‘Tequila’ Crisis of 94, the Asian Crisis of 97, the Russian Crisis of 98, and the complete breakdown in Argentina in 2000.

All governments are our enemy, not just this one!

What does this potted history of the crisis tell us? For one, it demonstrates that the crisis is historic in scale, a product of an entire social system in decline. The media usually blame the government in power for the crisis but it has been a constant companion of right and left-wing governments in every country, and so have the resulting attacks on our living standards. Whether it’s the wage freeze imposed by Labour’s ‘social contract’ in the 70s or the mass unemployment under Conservative governments in the 80s, the common denominator under all governments is that the working class has to pay for the crisis.

For all their fine words, once in power, every would-be government is confronted with the same economic reality which demands workers sacrifice their interests for the sake of ‘their’ country. From this perspective, all governments are the same and participation in elections or signing petitions begging the capitalist state to have mercy are all a waste of time. The only restraint on capital’s assault on the working class is its estimation of how far it can push us before we start pushing back.

But how can we fight effectively? Firstly, we must challenge the idea of each sector fighting its own corner: instead, we must try to struggle together wherever possible. In colleges and workplaces we can hold general meetings open to everyone, regardless of faculty, job or union, where real decisions can be made about the demands to raise and how to win them. We can send mass delegations to other colleges and workplaces inviting them to join in.

Demonstrations should become a vehicle for workers and students to discuss together, for reaching out to other workplaces under attack (local councils, postal sorting offices, etc.) and asking those workers to join them.

But ultimately, the severity of capitalism’s decline is such that even the most vigorous struggle can only bring about a temporary relief.Capitalism has no choice but to come back for more. Eventually, the struggle against austerity must go beyond immediate self-defence and begin to pose the question of replacing a decrepit capitalism with a new social system that will provide for the needs of all members of society.

This is not a utopia; the weapons of self-organisation and class consciousness forged in the defensive struggle will be the same ones that will one day be used to overthrow our exploiters and build a new world of human solidarity.

International Communist Current 27/1/11

Geographical:

- Britain [3]

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [4]

- Economic Crisis [5]

- Education cuts [6]

The economic crisis didn’t start in 2007

- 3260 reads

The shock contraction of 0.5% in the last quarter of 2010 has been somewhat unnerving for British capitalism. Labour immediately seized on the figures as evidence that the Coalition cuts agenda was ill-advised and risked tipping the economy back into recession. Chancellor Osborne responded by saying that backing down on cuts would create worse turmoil in the markets and weaken the economy further.

While from the capitalist point of view there is a real debate on how to manage the economic situation, another aim of carrying out these debates is to obfuscate the true depths of the crisis now confronting the capitalist system. The ruling class present the recent economic disasters as the result of ‘greedy bankers’ and mistakes by government. In reality, however, the crisis is the product of the underlying mechanisms of capitalism. While government policy can influence or moderate the action of these mechanisms, it can never overcome them. The contradictions they seek to resolve are simply displaced – they change their form of expression but eventually return to haunt the ruling class.

Today’s economic situation did not simply fall from the sky. It is the result of decades of deterioration in capitalism’s underlying economic health and the successive failure of all the economic policies mobilised by the ruling class to try and prevent it.

The last phase of sustained growth experienced by capitalism was the post-war boom. While there had been recessions during the boom period, these were usually tackled successfully with ‘Keynesian’ state intervention. Recessions were short-lived and followed by vigorous growth.

While it was especially powerful in the West, the Eastern Bloc was also affected. The Soviet Union was at the height of its power, its economic and military power symbolised by the launch of Sputnik and then Yuri Gagarin into space.

This ‘economic miracle’ – as it was called in a number of countries – began to fizzle out by the late 60s. The first signs of stress were located in the Bretton Woods monetary system, based on dollar-gold convertibility. The US balance of payments had gone negative as early as 1950. Initially, this favoured the boom as the flood of dollars maintained liquidity but over time it began to erode confidence, a situation known as “Triffin’s Dilemma” after the economist who identified it. By 1967, the global monetary system was suffering serious stress and a run on Sterling was the first in a series of destabilising affairs. By 1971, Bretton-Woods was finished.

Monetary difficulties were accompanied by broader economic problems. The devaluation of the dollar badly hurt the oil producing countries and this (combined with the Yom Kippur war) produced the oil crisis of 1973, when the price of oil rose considerably. The overproduction incurred as a result of the crisis was symbolised by the steel crisis – the saturation of global steel markets. Two years of recession followed accompanied by the new phenomenon of ‘stagflation’ - a situation where inflation remains high despite low growth, unemployment and even recession.

The Keynesian consensus of the day appeared powerless to overcome the crisis and this opened the door to monetarism or neo-liberalism. This new policy, christened ‘Reaganomics’ or ‘Thatcherism’ after its most belligerent advocates, promised to overcome the chronic crisis (especially inflation) and return capitalism to the path of growth. Economically, this meant curtailing monetary growth; reducing taxation and state spending; deregulation (particularly of finance capital); and (in many countries) the withdrawal of the state from direct ownership of areas of the capitalist economy (privatisation).

Contrary to the ideology of both left and right, which presented this as a retreat of the state, it was nothing of the kind. The state retained regulatory control over the privatised industries and continued to control the metabolic rate of the economy through interest rates and monetary policy.

The state could no longer afford to resist the inexorable pressures of the market. For capitalism to function, it must be able to establish a sufficient rate of exploitation to allow it to grow. The working class had vigorously resisted the policy of wage cuts via inflation that the Left governments of the 70s had attempted to impose. In response, capitalism simply unleashed the competition that was a consequence of the international overcapacity engendered by a decade of stagnating growth. The market was allowed to do ‘economically’ what the state was unable to do politically. Entire swathes of manufacturing industry in the West were wiped out, with millions of workers laid off. Those that remained were forced to submit to a brutal haemorrhaging of wages and working conditions, and the amputation of the ‘social state’ – that is, reducing the provision of services such as health and education provided through the state while forcing the workers that provide them to do so more ‘efficiently’.

The decimation of manufacturing in the ‘mature’ capitalist economies had its natural counterpoint in the outsourcing to certain sectors of the ‘Third World’. Based on massive rates of exploitation, countries such as China were able to pick up the baton and became the workshops of the world. In the meantime, Western economies, through their financial dominance, could leech massive amounts of value from the new manufacturing centres. This capital naturally required reinvestment but despite the partial recovery from the disaster of the 70s, investment outlets were still inadequate. The deregulation of capital flows allowed enormous amounts of capital to flow quickly around the world in the search of profit and creating a vast pool of speculative finance.

This experimentation with the economic crack cocaine of speculation quickly developed into a full blown addiction. While bubbles and manias have always been a natural product of the capitalist cycle, they more and more came to dominate completely. This certainly provided a level of stimulus for the economy – although actual growth still lagged behind that achieved in the post-war boom – but at the price of increasing financial and monetary instability. 1987 saw the Stock Market Crash, swiftly followed by the Savings & Loan Crisis in the US, while 1990 saw the beginning of a new recession in the West. 1990 also saw crisis in Japan, until then a seemingly unstoppable growth engine, as it suffered the collapse of one of the biggest asset price bubbles in history. Consequently, Japan suffered a decade of stagnation and built up a staggering national debt, a situation that still haunts it today.

From the 90s onwards, currency meltdowns and financial crises became common-place. 1990 saw the collapse of Swedish and Finnish banking systems. In 1992, the European Exchange Rate Mechanism lurched into a crisis. Sterling was rapidly ejected and other currencies also came under serious speculative attack. Hard on the heels of the ERM crisis was the ‘Tequila Crisis’ of 94, another speculative attack on the Mexican Peso. The most serious financial panic, however, was undoubtedly the ‘Asian Crisis’ of 1997, a series of speculative attacks on various South East Asian currencies. This culminated in a storm that swept through the region and brought the vaunted economic ‘Tigers’ and ‘Dragons’ to their knees. This was swiftly followed by almost total economic collapse in Russia in 1998 – millions of people lost their life savings as the banking system toppled over and production ground to a halt. Argentina suffered a similar fate in 2000 while the US in 2001 saw the explosion of the dot.com bubble.

With each episode, the fiscal authorities responded with ever more powerful monetary stimulus, albeit with diminishing results. This has the effect of temporarily relieving the immediate crisis at the price of immediately stimulating another massive bubble. The rampant and malignant growth of ‘sub-prime’ finance that ultimately led to the credit crunch was thus the product of the loose monetary policy that followed the dot.com crash. This perfectly illustrates the chronic dilemma that has more and more confronted capitalism in the past few decades – pour monetary fuel onto the fire and risk the fire consuming everything or watch the fire be extinguished entirely.

There is no longer the possibility of capitalism resolving its economic stagnation in any progressive manner. Instead, all it can offer humanity is an ever more barbarous parade of economic breakdown, intractable and brutal wars, environmental catastrophe and social collapse. Only the class struggle of the proletariat offers an alternative.

Ishamael 1/2/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [5]

Methods of infiltration by the democratic state

- 2990 reads

That the police have infiltrated the environmental and anti-globalisation protest movements over the past decade should come as no surprise to those living in ‘perfidious Albion’. In the 1840s the ‘Peelers’ had informers inside the Chartist movement (Thomas Powell) and the Cold War machinations of MI6 are legendary. The state infiltration of the Irish Republican movement has given us the ‘Stakeknife’ affair, where one of the IRA’s chief spy-catchers was himself a British agent for 25 years, with the British government allowing at least 40 people to be tortured and killed to protect his identity. (See WR 274, ‘British state organises terrorism in Ireland’).

The revelations in The Guardian during January that exposed four undercover agents of the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU), and the outraged response to them from the ‘democratic’ media and politicians, are nevertheless worthy of attention. Concerns about the first agent – PC Mark Stone (aka Mark Kennedy) – were first made public in October 2010 on Indymedia[1], but it was the collapse of the trial in early January of 6 activists accused of conspiring to break into Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station that grabbed the headlines. Apparently Stone, wracked with remorse, had threatened to ‘go native’ and give evidence for the defence.

He obviously has plenty of evidence at hand. According to The Guardian, from the day his undercover operation began, “Kennedy would live a remarkable double life lasting more than seven years... Kennedy was feeding back detailed reports to his police commanders as he participated in, and sometimes even organised, some of the most high-profile demonstrations of the past decade. He took part in almost every major environmental protest in the UK from 2003, and also managed to infiltrate groups of anti-racists, anarchists and animal rights protesters. Using a fake passport, Kennedy visited more than 22 countries, taking part in protests against the building of a dam in Iceland, touring Spain with eco-activists, and penetrating anarchist networks in Germany and Italy.” (‘Mark Kennedy: A journey from undercover cop to ‘bona fide’ activist’, 10/01/11.) His success was down to having transport and money. Socially, he seemed to get on well with his targets, even having relationships with women, who rightly feel disgusted and betrayed by his duplicity.

The same cannot be said for PC Mark ‘Marco’ Jacobs who infiltrated the Cardiff Anarchist Network between 2005 and 2009. According to CAN, Jacobs’ key objectives were “to gather intelligence and disrupt the activities of CAN; to use the reputation and trust CAN had built up to infiltrate other groups, including a European network of activists; and to stop CAN functioning as a coherent group.” (‘They come at us because we are strong’, fitwatch.org). While Jacobs shared the first two objectives with Kennedy, it is the third that stands out, and was probably used by the police because the CAN was more politicised. The tactics used to achieve this aim are reminiscent of the Stalinist GPU within the Trotskyist movement during the 1930s: “He changed the culture of the organisation, encouraging a lot of drinking, gossip and back-stabbing, and trivialised and ran down any attempt made by anyone in the group to achieve objectives. He clearly aimed to separate and isolate certain people from the group and from each other, and subtly exaggerated political and personal differences, telling lies to both ‘sides’ to create distrust and ill-feeling. In the four years he was in Cardiff a strong, cohesive and active group had all but disintegrated. Marco left after anarchist meetings in the city stopped being held.” (ibid).

Activists from CAN approached The Guardian with their concerns, who took them to the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) which confirmed that Jacobs was an officer with the NPOIU. Environmentalist activists in Leeds also had concerns about one Lynne Watson (and subsequently her partner) who had been involved in protest groups from 2004 to 2008. After Mark Kennedy was exposed in the autumn he apparently confirmed Watson was, like him, an NPOIU officer. The Leeds activists approached The Guardian, and the ACPO confirmed their suspicions, asking that she not be named until she was ‘extracted’ from her current operation. (See the ActivistSecurity.org statement on Lynn Watson[2]).

The subsequent inquiries into the Mark Stone case have shed light on the accountability of the various police agencies. The connection between the NPOIU and the ACPO is revealing. The ACPO is actually a private limited company. Before the Stone story broke, the NPOIU reported directly to the ACPO, not the government’s Home Office, meaning that it was not bound by the Freedom of Information Act. While we can have no illusions in a free and fair ‘democratic’ police force, the growing ‘privatisation’ of policing is interesting. The US government’s contracting out of security to private firms in Iraq and Afghanistan seems to have inspired the Labour Party’s approach to policing during the Blair administration. The NPOIU was formed in 1990, and is now part of the National Domestic Extremism Unit, responsibility for which has been handed to the Metropolitan Police.

Another element in the Kennedy affair has been the degree to which different European states – in this case Ireland, Iceland and Germany - cooperated in both using and covering up for Kennedy in his work of penetrating European activist and anarchist networks (wsws.org, 3/2/11, ‘Police agent Kennedy was active throughout Europe’).

The technology of police surveillance has, of course, become much more sophisticated since Victor Serge wrote ‘What every revolutionary should know about state repression’ in 1926, basing himself on the activities of the Tsarist Okhrana. But the basic methods for infiltrating and sabotaging the work of ‘subversive’ elements remain substantially the same: get your agents inside as many of these dissident networks and organisations as possible; once inside, stir up personal animosities and rivalries; encourage all kinds of ‘extreme’ actions that give the state an excuse to smash the organisation. The work of Kennedy and his colleagues was directed mainly at a very amorphous activist milieu which presents numerous opportunities for infiltration and acts of provocation. But revolutionary communists should be under no illusion that the state, democratic or otherwise, will not use the same tricks against them.

Colin, 27/01/11

Geographical:

- Britain [3]

Recent and ongoing:

The real role of the TUC: policing the class struggle

- 2474 reads

For its 26 March demonstration against government cuts the TUC are setting up a call in centre at their Congress House HQ in conjunction with the Metropolitan Police. Any information sent in by TUC stewards will go straight to the cops. Not only do the unions act with the police, they act as the police in workers’ struggles. They have also undermined any initiatives towards solidarity with the militant actions of students.

In Britain the student demonstrations and occupations at the end of 2010 were some of the most inspiring actions in twenty years. Not looking to a lead from the left or the unions, and not limiting their concerns to the education sector, the students’ initiatives often bypassed the ‘usual channels’ that lead to dead ends.

In 2011 we have seen a resumption in demonstrations and discussions on the way forward, partly re-energised by events in Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East. It would be misleading to overestimate the current strength of the movement, but it is significant that the forces of the left and the unions are struggling to play much of a role ... so far.

Unions stumble to catch up

Before Christmas RMT leader Bob Crow spoke about the need for “Industrial action, civil disobedience and millions on the streets” in response to government cuts. Since then he has conceded that the RMT and Aslef have not been able to co-ordinate any action on the railways. The energies of the unions have been put into building up a demonstration on 26 March where they hope a million will march three days after the next budget.

This demonstration, more than 3 months after the actions at the end of last year, is not aimed at the extension and self-organisation of the movement but at providing a safe, controlled outlet for all the anger at each new wave of austerity measures.

Leftist groups like the Socialist Workers Party cry out that the “TUC must call a general strike.” That is to say that the unions must take over a movement that has so far shown little interest in or respect for the unions. At a local level, for example, if you’d been at a meeting on 20 January at Goldsmiths College in South London that involved students and others, the few mentions of the unions were just ignored. Members of a local leftist anti-cuts committee spoke about their campaign employing the usual clichés and set phrases, while the rest wrestled with real questions about where the movement was now and what were the next steps to take. A member of the SWP said it was necessary to call for an emergency general union meeting – not realising that he was actually in the presence of militant students who were already discussing and looking for a perspective for the development of the struggle without the straitjacket of the union.

There have been demonstrations since the start of the year but, for all the unions’ claims of supporting student initiatives, the unions have been unable to relate to the movement. At a demonstration in London on 29 January when at the beginning of the march a union speech started it acted as a cue for the march to move off. At the end of the march it seemed as though all the planned speeches were shelved.

Deliver us not unto Labour

In describing events in Egypt for Socialist Worker (31/1/11) its editor remarks that “There is no plan. There is no one organisation responsible.” This is true, and also applicable to Britain. But while revolutionary organisations encourage all tendencies toward self-organisation and towards the unification of the struggles of those already expressing their anger, the left and the unions have structures in place ready to sabotage the movement.

Not only are there calls for the TUC to call a General Strike but also to “Kick out Clegg and Cameron”. The implications of this are simple. Mark Serwotka, the general secretary of the Public and Commercial Services (PCS) union says that “While strike action is always a last resort, it would be the result of the government’s refusal to change course and its political choice to press ahead with unnecessary and hugely damaging cuts.” This claim that government cuts (following on from Labour’s) are an unnecessary political choice is false. The reason that the Lib-Con Coalition have undertaken cuts is for the same reasons Labour did: Britain is bankrupt. This has not of course stopped Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls from saying that the US economy, which hasn’t yet adopted the same policies as Clegg/Cameron, grew towards the end of last year. Yes, the resort to even greater debt is still being touted as a policy by the left – regardless of what it leads to in terms of the economy and in terms of the widespread poverty across the US. The ‘political choice’ that’s an ‘alternative’ to the Coalition is a Labour government. This is where the logic of the left leads.

A headline in Socialist World quotes an activist in Tunisia: “We need a clean trade union, which really represents the working class.” Clean or dirty, in Europe or North Africa, unions no longer represent the interests of the working class. In last year’s struggles in Britain, Greece, France and Italy we began to see what workers and students are capable of. Suspicion towards the unions and attempts to create new forms of organisation that are responsive to the needs of the struggle are entirely healthy. The routes marked out by unions and leftists can only serve to derail struggles.

Car 31/1/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Socialist Workers Party [11]

- unions against the working class [12]

- TUC [13]

Ireland: all the politicians agree on the need for austerity

- 2706 reads

Political pundits are predicting meltdown for Fianna Fail at the Irish general election on 25 February, maybe losing more than half their seats. Considered the ‘natural party of government’ since coming to power in 1932, Fianna Fail has always had the most seats and the biggest share of the vote since 1933, and been in power for 61 of the last 79 years.

Whatever the result, all four of the main political parties in Ireland voted through the austerity measures required to get the €85 billion bail-out from the IMF and the EU. Whatever party or parties forms the next government, it will have little room for manoeuvre.

There will be €15 billion worth of cuts over the next 3 years, cutting, among many other things, the minimum wage, benefits and public sector jobs, following on from the billions already gouged from state expenditure. The economy has shrunk by over 20% in the past two years: even the most optimistic forecasts show only a marginal recovery for the foreseeable future. The 14% unemployment rate is the highest ever in absolute numbers and, of the 34 OECD states, only Spain and Slovakia have higher rates. Employment in the construction industry more than halved between 2008 and 2010. While thousands more are forecast to lose their jobs this year, a record 50,000 people are predicted to emigrate from Ireland in 2011, more than in any of the years of the 1980s’ recession.

Because the outgoing Fianna Fail/Green Party government is being widely blamed for the effects of the capitalist economic crisis in Ireland, other combinations of bourgeois parties are being backed to take over the running of the Irish state. The most popular prediction is for another Fine Gael/Labour Party coalition. This would be the seventh time this combination had been in charge. For all the supposed differences between the right wing Fine Gael and social democratic Labour, they have not found any difficulty in the past in enforcing austerity.

Some are predicting that, with a backlash against the ‘excesses’ of ‘free market’ capitalism, Labour and Sinn Fein will benefit, and be capable of forming a government in alliance with others. Should this unlikely first ever left wing Irish government transpire, the programmes of each party indicate that they will be perfectly capable of managing the state in the interests of Irish capitalism – for all that Gerry Adams continues to insist that he is a “subversive”.

The response of the working class in Ireland to the attacks on their conditions of life has been limited. In recent years there have been a number of massive, but union-dominated marches in response to different waves of austerity measures. The influence of the unions is still significant. Last year a number of major unions agreed a 4-year strike ban. While this is still holding there is still the potential for workers to see beyond the parliamentary games, beyond ‘responsible’ trade unionism, beyond the lies of Irish nationalism, and launch struggles in defence of their own class interests.

Car 4/2/11 <?xml:namespace prefix = o />

Geographical:

- Ireland [14]

Recent and ongoing:

- Attacks on workers [15]

- Elections [16]

The Palestinian Authority: a fig leaf for naked imperialism

- 2804 reads

Last month, when the proletariat and masses of large swathes of the Maghreb and the Middle East began rising up against their capitalist bosses, a Palestinian demonstration was mobilised in the West Bank to march behind the banners of Fatah to protest that their Palestinian Authority had been somehow wronged by the revelations that it was the “Third Israeli security arm” (US security coordinator for Israel and Palestine, General Keith Dayton). Or as World Revolution put it some time earlier, in December 2004 in fact, “Whereas the PLO was once an agent of the Russian bloc, (the) ‘Palestinian Authority’ was essentially created to act as an auxiliary force of repression for the Israeli army”.

The role of the PA, supported by the US, Britain and the EU as defenders of their imperialist needs and thus against the Palestinian masses, has been laid bare in 1600 documents leaked to al-Jazeera and published by The Guardian towards the end of January. The documents, some redacted in order to protect sources, have been authenticated by the newspaper and have been confirmed by recent Wikileaks’ cables coming from the US Consulate in Jerusalem and its embassy in Tel Aviv. They tell a story of the totally corrupt gangsters of the Authority, set up and funded by their American, British and Egyptian godfathers, begging their Israeli masters for a “fig-leaf” in order to give them some sort of credibility.

The documents detail the complete lies and sham of any ‘peace process’, a charade that been acted out for two decades now while the Palestinian masses have been going through humiliating misery, repression and war. Such is the nature of capitalist ‘peace’. The peace process in the Middle East has been nothing else except an expression of imperialism involving all the major powers and the local gangsters of the region. Amongst other things, the anti-working class nature of national liberation, in this case the chimera of a Palestinian state, is shown not only to be a pipe-dream for Palestinians but an ideological attack on the working class world-wide.

In any event, the documents show that only a very minimal number of refugees would be allowed to return to the homes from which they were ‘cleansed’, and are still being cleansed, in the interests of Greater Israel and the wider needs of American and British imperialism. They show a not so bizarre suggestion from US Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, a couple of years ago, echoing views from the west after World War II where Jews were asked to re-settle in disease-infested swamplands of South America, that Palestinians could be re-settled in “Chile, Argentina, etc.”. The lawyer, ex-Mossad agent and then Israeli Foreign Minister, Tzipi Livni, “negotiating” with the PA, says: “... I am against law – international law in particular”. That there’s no peace process, that imperialism knows no law, international or otherwise, is also reflected in the lawyer Tony Blair being appointed as the “Quartet’s Middle East Peace Envoy”! There is a law at work though, the law of the jungle, and Chief PA negotiator, Saeb Erekat, sums it up well: “We have had to kill Palestinians... we have even killed our own people to maintain order and the rule of law”. Added to this, in an indication of the gangster nature of the “peace process”, is the stunning revelation that in a meeting in 2005 between the Palestinian Authorities’ Interior Minister, Nasser Youssef and Israeli Defence Minister, Shaul Mofaz, Mofaz put this question to Yousef regarding an al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade commander suspected of facilitating a bombing in Israel: “You know his address... Why don’t you kill him?” Documents show Britain’s role in setting up the security force of ‘trusted’ PA contacts in clandestine operations with direct lines to Israeli intelligence. The current head of MI6, appointed by the Labour government, was himself the British ambassador to Egypt in early 2000.

Killing and torture is capitalist order, capitalist law. Further documents show that in response to the PA’s proposal to recognise all but one Israeli settlement on Palestinian land – an offer that was rejected out of hand by the Israelis – the Israelis’ proposed that Palestinians living in Israel could be “swapped”, ie cleansed, into the PA’s grip. Livni is clear that it’s been a long-time policy of Israel to take “... more and more land, day after day...” in order to create “facts on the ground”.

The Palestinian Authority, itself riven by corruption and rivalries which in turn are manipulated by the CIA, MI6 and the security services of Israel and Egypt, was also warned in advance of the Israeli invasion of Gaza, 2008/9.

Further, as The Guardian notes: “The papers highlight the far-reaching official British involvement in building up the Palestinian Authority’s security apparatus in the West Bank”. They also show that MI6 concocted its Security Plan for Palestine working with Egyptian intelligence in the British embassy in Cairo. It used EU funds and British development ‘aid’ to help bankroll these forces. There can be little doubt that Britain provided arms and training as well. These forces are praised by the Israelis and the Americans, but “they are causing some problems ... because they are torturing people” (General K. Dayton).

None of this leads us to give the least credibility to Hamas – itself a co-negotiator with Israeli intelligence when needs must and a repressive and torturing force in its own enclave. Its imperialist role is clear from its support by Iran and Syria.

The whole “Partners for Peace” process has not only been a cruel joke on the Palestinian masses and a defence of imperialism but an ongoing ideological attack against the working class world-wide. But events are stirring and the pro-Palestinian, pro-Fatah demonstration mentioned above wasn’t the only one to take place in January. Human Rights Watch, 1.2.11, reports: “On January 20, a group of young people in Ramallah who wanted to demonstrate their support for the Tunisians were thwarted by Palestinian Authority police”. A week or so later, it reports: “Hamas authorities prevented demonstrations in the Gaza Strip aimed at showing solidarity with anti-government protestors in Egypt”. Hamas police arrested three women and, in a show of overwhelming force, threatened other would be protesters[1]. We see the clear unity of interest of all these bourgeois gangs: the PA, Hamas, the Israeli and Egyptian states in stifling protest, repressing dissent and defending ‘their’ territories. It’s a lesson that the workers’ history knows well from the Paris Commune, the Russian Revolution, Italy and France after WWII and Poland in 1980 – all examples of where imperialist forces dropped their mutual antagonisms in order to confront the threat of class struggle. In late January, this was also evidenced in the US facilitating, with Israeli agreement, Egyptian special forces being sent across the demilitarised Sinai in order to repress the uprising around the Rafah crossing and strengthen the border with Gaza; in this case, the US, Hamas, Fatah, Israel and Egypt all in perfect harmony in coordinating the forces of repression for the maintenance of the border and capitalist order. This ‘truce’ will only last as long as they are all worried about protest generalising; when it dies down they will be back to their usual tricks and rivalries.

Baboon. 3/2/2011

[1]. There were also reports of a small demonstration in support of both the Tunisian and Egyptian masses in north Tel Aviv.

Geographical:

- Palestine [17]

Recent and ongoing:

In memory of Martyn Richards

- 2793 reads

Our comrade Martyn has lost a very painful struggle with cancer. His death in his early fifties is a heavy blow. Martyn was a close sympathiser of the ICC for nearly 30 years. He first made contact with us in the early 80s after experiencing at first hand the reactionary and dishonest character of the Trotskyist organisations (in this case the ‘Militant’ variety). After a brief phase of defining himself as a council communist he moved towards the politics of the ICC and remained convinced of our positions for the rest of his life. Even when he was very close to death he wanted to make it clear that he maintained his confidence in the ICC and has left to us his collection of political books.

For one reason of another – perhaps because Martyn had a tendency to underestimate the degree to which he really grasped our political positions, especially on the organisation question – he never became a member but he took a full part in many of our interventions, defended the organisation when it was under fire, and kept up a regular activity in his own home town of Leicester, selling the press, participating in political meetings and making contacts around him. During the 90s this activity bore fruit in the formation of a discussion circle in Leicester, which subsequently expanded to Birmingham and survives today as the Midlands Discussion Forum. Some of the ICC’s present membership in the UK initially passed through this circle but it always retained its character as an open forum where different tendencies within the working class could meet and debate; and this openness, along with the longevity of the circle, owes a lot to the role that Martyn played within the circle, above all the seriousness with which he approached political debate and clarification.

Martyn’s interest in discussion was not limited to politics in the narrower sense but took in many wider areas such as anthropology, ancient history, art and music. He spent much of his working life as a printer, although more recently he went to university to study the history of art.He also became a father and was immensely proud of his son, who along with Martyn’s wife will be feeling this loss more than we can convey here. But Martyn will also be mourned by all who knew him as a comrade and a fighter for the communist revolution.

WR 7/2/11

People:

- Martyn Richards [19]

Recent and ongoing:

- Obituary [20]

- Midlands Discussion Forum [21]

Mass strikes in Britain: the ‘Great Labour Unrest’, 1910-1914

- 22976 reads

100 years ago this August the British ruling class was forced to dispatch troops and warships to Liverpool to crush a near-insurrectionary general strike. The Lord Mayor of the city warned the government that “a revolution was in progress.”[1]

These extraordinary events were one of the high points of a whole series of struggles in Britain and Ireland before the First World War popularly known as ‘the Great Labour Unrest’. As the following article shows, these struggles were in fact a spectacular expression of the mass strike, and formed an integral part of an international wave that eventually culminated in the 1917 Russian revolution. Even today they are not widely known but remain rich in lessons for the struggles of today and tomorrow.

International context

Between 1910 and 1914, the working class in Britain and Ireland launched successive waves of mass strikes of unprecedented breadth and ferocity against all the key sectors of capital, strikes that blew apart all the carefully cultivated myths about the passivity of the British working class that had blossomed in the previous epoch of capitalist prosperity.

Words used to describe these struggles in official histories include ‘unique’, ‘unprecedented’, ‘explosion’, ‘earthquake’…. In contrast to the largely peaceful, union-organised strikes of the latter half of the nineteenth century, the pre-war mass strikes extended rapidly and unofficially across different sectors – mines, railways, docks and transport, engineering, building – and threatened to go beyond the whole trade union machinery and directly confront the capitalist state.

This was the mass strike so brilliantly analysed by Rosa Luxemburg, its development signalling the end of capitalism’s progressive phase and the emergence of a new, revolutionary period. Although the fullest expression of the mass strike was in Russia in 1905, Rosa Luxemburg showed that it was not a specifically Russian product but “the universal form of the proletarian class struggle resulting from the present stage of capitalist development and class relations” (The Mass Strike). Her description of the general characteristics of this new phenomenon serves as a vivid description of the ‘Great Labour Unrest’:

“The mass strike...flows now like a broad billow over the whole kingdom, and now divides into a gigantic network of narrow streams; now it bubbles forth from under the ground like a freshspring and now is completely lost under the earth. Political and economic strikes, mass strikes and partial strikes, demonstrative strikes and fighting strikes, general strikes of individual branches of industry and general strikes in individual towns, peaceful wage struggles and street massacres, barricade fighting - all these run through one another, run side by side, cross one another, flow in and over one another - it is a ceaselessly moving, changing sea of phenomena...” (The Mass Strike).

Far from being the product of peculiarly British conditions, the mass strikes in Britain and Ireland formed an integral part of an international wave of struggles that developed throughout Western Europe and America after 1900: the 1902 general strike in Barcelona; 1903 mass strikes by railway workers in Holland; 1905 mass strike by miners in the Ruhr....

Revolutionaries have yet to draw out all the lessons of the British mass strikes – partly due to the sheer scale and complexity of the events themselves but also because the bourgeoisie has tried to quietly bury them as a forgotten episode.[2] It is no coincidence that to this day it the General Strike of 1926 and not the pre-war strike wave which has pride of place in the official history of the British ‘labour movement’: 1926 marked a decisive defeat, whereas 1910-1914 saw the British working class take the offensive against capital.

The revival of struggles

The mass strike in Britain and Ireland can be traced to the depression of 1908-09. In the previous year the working class in Belfast had united across the sectarian divide to launch a general strike that had to be put down by extra police and troops.[3] In the north-east of England there were strikes by cotton workers, and engineering and shipbuilding workers. A railway strike was narrowly averted. When the depression lifted the explosion came.

The first phase of the mass strike had its centre of activity in the previously non-militant South Wales coalfield. Unofficial strike action hit a number of pits between September 1910 and August 1911, at its highest point involving around 30,000 miners. Initial grievances focused on wages and conditions of employment. Miners spread the strikes through mass picketing. There were also unofficial strikes in the normally conservative Durham coalfield in early 1910, and spontaneous strikes in the north-east shipyards.

In the second phase the focus shifted to the transport sector. Between June and September 1911 there was a wave of militant, unofficial action in the main ports and on the railways, which experienced their first national strike. In the ports, local union officials were taken by surprise as mass picketing spread the struggle from Southampton to Hull, Goole, Manchester and Liverpool and brought out workers in other dockside industries who raised their own demands. No sooner had the unions negotiated an end to these strikes than another wave of struggle hit the sector – this time centred on London, which had previously been unaffected. Unofficial action spread throughout the docks system against a union-negotiated wage deal, compelling officials to call a general strike of the port. Unofficial strikes continued during August, despite further wage agreements.

As the London dock strike subsided, mass action switched to the railways with unofficial action beginning on Merseyside where 8,000 dockers and carters came out in solidarity after five days. By 15 August 70,000 workers were on strike on Merseyside. The strike committee set up during the seamen’s strike reconvened. After employers imposed a lock-out the committee launched a general strike which was only finally settled after two weeks of violent clashes with the police and troops.

Meanwhile, unofficial action on the railways extended rapidly from Liverpool to Manchester, Hull, Bristol and Swansea, forcing rail union leaders to call a general strike – the first ever national rail strike. There was active support from miners and other workers (including strikes by schoolchildren in the main railway towns). When the strike was suddenly called off by union leaders after government mediation thousands of workers erupted with anger and militancy persisted.

During the winter of 1911-12 the main centre of the mass strike shifted back to the mining industry, where unofficial direct action led to a four-week national strike involving a million workers – the largest strike Britain had ever seen. Unrest among the rank and file grew after union leaders called for a return to work and strikes broke out again in the transport sector, with a London transport workers’ strike in June-July. This collapsed, partly due to lack of support from outside London, but during the summer of 1912 there were other strikes by dockers, for example on Merseyside.

Unlike the previous, relatively peaceful wave of struggles in 1887-93, workers showed themselves more than ready to use force to extend their struggle, and the pre-war mass strikes saw widespread acts of sabotage, attacks on collieries, docks and railway installations, and violent clashes with employers, strike-breakers, police and the military, in which at least five workers were killed and many injured.

Acknowledging the significance of the struggles, the bourgeoisie took unprecedented steps to suppress them. In the most famous case, 5,000 troops and hundreds of police were rushed to Liverpool in August 1911, while two warships trained their guns on the town. This culminated in ‘Bloody Sunday’: the violent dispersal of a peaceful mass workers’ demonstration by police and troops. In response, the workers overcame traditional sectarian divisions to defend their communities during several days of ‘guerrilla warfare’ which made use of barricades and barbed wire entanglements.

By 1912, the state was forced to take even more elaborate precautions, deploying troops against the threat of generalised unrest and putting whole areas of the country under martial law. Alarmingly for the bourgeoisie there were small but significant efforts by militants to carry out anti-militarist propaganda among the troops, including the famous 1912 Don’t Shoot leaflet, which prompted swift repression.

The working class now faced a concerted counter-attack by the capitalist class, which was determined to inflict a defeat as a lesson to the whole proletariat. In 1913 over 11 million strike days were lost, and there were more individual strikes than in any other year of the ‘Unrest’, in hitherto unaffected sectors like semi- and unskilled engineering workers, building workers, agricultural labourers and municipal employees; but this year saw a definite downturn, marked among other things by the defeat of the Irish workers in the Dublin Lock-out.

The trade union bureaucracy also began to regain control over the workers’ struggles. The formation of the ‘Triple Alliance’ in 1914, supposedly intended to co-ordinate action by the miners, railwaymen and transport workers, was in reality a bureaucratic measure to recuperate the spontaneous and unofficial action of the mass strikes, and prevent future outbreaks of uncontrollable rank and file militancy. Similarly, the formation of the National Union of Railwaymen as a single sector-wide ‘industrial union’ was not so much a victory for syndicalist propaganda or a response to changes in capitalist production as a manoeuvre by the union bureaucracy against unofficial militancy.

Nevertheless, discontent continued without any decisive defeats, and on the eve of the First World War the Liberal government minister Lloyd George shrewdly observed that with trouble threatening in the railway, mining, engineering and building industries,“the autumn would witness a series of industrial disturbances without precedent”.[4] Certainly the outbreak of war in 1914 came just at the right moment for the British bourgeoisie, effectively braking the development of the mass strikes and throwing the working class into deep - albeit temporary - confusion. But this defeat proved temporary, and as early as February 1915 workers’ struggles in Britain revived under the impact of wartime austerity, developing as an integral part of an international wave that eventually culminated in the 1917 Russian revolution.

The importance of the mass strikes

Fundamentally the pre-war mass strikes were a response by the working class to the onset of capitalist decadence, revealing all of the most important features of the class struggle in the new period:

- a spontaneous, explosive character

- a tendency towards self-organisation

- rapid extension across different sectors

- a tendency to go beyond the whole trade union machinery and directly confront the capitalist state.

More specifically, the mass strikes were a response to the growth of state capitalism and to the integration of the Labour Party and the trade unions into the state machine in order to more effectively control the class struggle. Among militant workers there was widespread disillusionment in parliamentary socialism as a result of the Labour Party’s loyal support for the Liberals’ repressive social welfare programmes, and the active role of the trade unions in administering them.

Most significantly, for the first time in its history the British working class launched massive struggles which went beyond and in some cases directly against the existing union organisations. National and local union leaders lost control of the movement at many points, particularly during the transport and dockers’ strikes (according to police reports, in Hull the unions lost control of the dockers’ strike altogether).

Union membership had been declining, partly due to growing rank and file dissatisfaction with the trade union leadership. The mass strikes resulted in a 50 per cent increase in union membership between 1910 and 1914, but, in contrast to the struggles of 1887-93, union recognition was not a major theme of these struggles, which instead saw unofficial strikes and direct action against those union leaderships who backed government ‘conciliation’ and were openly hostile to strike action: for example, railway union leader Jimmy Thomas was shouted down for defending the conciliation system, and at a mass meeting in Trafalgar Square in July 1914, militant building workers took over the platform and refused to let officials speak.

Enormous rank and file pressure was exerted even on the more militant leaders of the new general unions: on Merseyside, for example, even the syndicalist leader Tom Mann was heckled and shouted down by unofficial leaders and strikers, and it took a week of mass meetings to overcome resistance to a return to work.

The mass strikes also saw the growth of unofficial strike committees, some remaining after the defeat of strikes as political groupings demanding reform of the existing unions: for example, the Unofficial Reform Committee in South Wales which called for reform of the local miners’ union on ‘fighting lines’. A similar group emerged in the engineering union in 1910 which engaged in a violent battle with the existing leadership. Unofficial groups of militants also emerged among dockers in Liverpool, close to Jim Larkin and defending syndicalist ideas, while in London a syndicalist ‘Provisional Committee for the formation of a National Transport Workers Union’ was formed on the basis of discontent with the union leadership.

We can see in these developments a real deepening of class consciousness and the spread of important lessons about the new period among the masses of workers thrown into struggle, for example:

- the perception of a change in the economic and political conditions for the class struggle

- the need for direct action in defence of working class conditions

- the inability of the trade unions, as presently organised, to effectively defend those interests and the need to struggle for control of the unions

- the need for new forms of organisation more suited to the new conditions.

Above all, the struggles in Britain and Ireland formed a part of the international mass strike, and therefore had an importance for the whole working class. Characteristically, the British workers were not the first to enter into struggle, but their arrival on the scene as the oldest and most experienced fraction of the world proletariat added a huge weight to the movement, providing an invaluable example of struggle against a highly sophisticated bourgeoisie and its democratic mystifications. Inevitably the strikes also showed all the difficulties facing the working class in developing its immediate struggles into a revolutionary movement, especially as the change in period and the impossibility of a struggle for reforms within capitalism had not yet been definitively announced. But they showed the way forward.

MH 31/1/11

see

Revolutionaries and the mass strikes, 1910-1914: the strengths and limits of syndicalism [23]

[2]. A very good account of the pre-war mass strikes is to be found Bob Holton’s British Syndicalism 1900-1914 (Pluto Press, 1976), which forms the basis of this article.

[4]. Quoted in Walter Kendall, The Revolutionary Movement in Britain 1900-1921, 1969, p.28.

Historic events:

Geographical:

- Britain [3]

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [4]

Rubric:

Capitalism breeds disaster

- 3763 reads

This year was ushered in by a series of devastating floods: in Queensland, Australia, covering an area greater than France and Germany combined, in Sri Lanka and in the Philippines. There has been further flooding in the Australian state of Victoria, with Cyclone Yasi battering Queensland, and a murderous mudslide in Brazil.

These follow on from the huge number of disasters in 2010:

- starting with the earthquake in Haiti on 12 January, killing 230,000, injuring 300,000, making over a million homeless and leading directly to the cholera outbreak ravaging the country;

- storm Xynthia battered the Atlantic coast of France, killing 52 in France, Spain and Portugal;

- earthquake in Chile killing 521, making half a million homeless;

- the heatwave in Moscow, killing 15,000, destroying crops and putting up wheat prices up 47%;

- enormous floods in Pakistan;

- the Mexican Gulf oil spill following the explosion of Deepwater Horizon, killing 11 workers on the oil platform and devastating the ecology of the area and the livelihoods of fishermen;

- the Hungarian aluminium spill causing 4 deaths and considerable ecological destruction.

So used to disaster are we becoming that if you look at the media since the New Year you could blink and miss the floods in the Philippines despite a death toll of 75 and £27bn of destruction to crops and infrastructure, and those in Sri Lanka with at least 40 dead and 300,000 displaced. You did not even need to blink to miss the Chinese drought, part of a general process of desertification: you have to look for it.

Capitalism’s responsibility for death and misery

There can be no doubt that the ruthless search for profit, heightened by fiercer competition as the economic crisis develops, is directly responsible for the deaths and ecological disasters caused by the BP oil spill and the Hungarian aluminium spill. But the same is true for the death and misery caused by seismic or climatic events. For example if we look at the earthquakes that took place in 2010 and compare the death toll and level of destruction, we can see the effects of a totally irresponsible policy of building cheaply without thought of what the buildings have to withstand. In New Zealand the earthquake of 7.1 on the Richter scale killed no-one, despite taking place close to the city of Christchurch, due to properly enforced seismic building regulations. In Haiti, a quake of similar magnitude, 7.3, caused hundreds of thousands of deaths in Port-au-Prince where buildings have just been put up as quickly, cheaply and profitably as possible regardless of even basic safety, let alone the well known risk of earthquakes. Once built, even prestigious buildings were not maintained.

When we come to the floods and mudslides a pattern of ruling class responsibility also emerges. In Brazil there were over 800 deaths in the state of Rio de Janeiro as a result of heavy rains and mudslides, with another 30 in neighbouring states. These can be directly linked to the policy of building in unsafe areas, despite the fact that January rains are getting heavier. The ministry to monitor urban planning was only set up in 2003 and £4.4bn set aside for disaster containment 2 years ago. “… ‘These are emergency works purely to reduce the repetition of tragedies,’ says Celso Carvalho, the national secretary of urban programmes. ‘Our cities are very insecure because of the failure to apply urban planning’. Short-term, eye-caching public works are the focus. Winning elections is the aim. Dominated by this logic, the main driver of cities’ growth is profit, above everything else. That’s the reason why so many people live in high-risk areas, such as the slopes of mountains. Land in the city centres is too valuable for social housing; often governments don’t force the private sector to use land in this way.” (www.guardian.co.uk [27]).

But surely in Australia, a developed democratic country, things will be different… Let’s see the response to both the fires and floods that have hit the continent in recent years: “It’s noteworthy that the Baillieu government in Victoria has accepted a recommendation from the Black Saturday royal commission to buy back properties not only in areas directly affected by the fire, but also those considered to be in high-risk fire zones across the state. But many residents plan to rebuild or remain in these areas, assessing the risk of another devastating fire as lower than the amenity of life in a rural idyll. In Queensland, those in low-lying areas will be forced to make similar assessments in the wake of this flood. But for many, living in such areas is not a matter of choice, it is because the houses are affordable. And with the population of southeast Queensland burgeoning during the past two decades as families flee the high costs of Sydney, many new houses have been built in areas inundated in the 1974 flood.

Research fellow in geotechnical and hydrological issues at Monash University Boyd Dent says that planners can forget the lessons of history. ‘It’s absolutely essential that we take matters such as environmental geology and flood history into account in urban planning…The historical nature of these things means they aren’t in the front of mind for planners, but then events like this come along to remind us all’..” (www.theaustralian.com [28], 12/1/11)

In Brazil and Australia, as in the USA at the time of Hurricane Katrina, the poor have to take the risks while capital makes the profits. Lives of workers go into the ‘cost-benefit’ analysis along with any other capital investment.

The aftermath – lies, hypocrisy, neglect

“A ‘humanitarian crisis of epic proportions’ is unfolding in flood-hit areas of southern Pakistan where malnutrition rates rival those of African countries affected by famine, according to the United Nations. In Sindh province, where some villages are still under water six months after the floods, almost one quarter of children under five are malnourished while 6% are severely underfed, a Floods Assessment Needs survey has found. ‘I haven’t seen malnutrition this bad since the worst of the famine in Ethiopia, Darfur and Chad. It’s shockingly bad,’ said Karen Allen, deputy head of Unicef in Pakistan. The survey reflects the continuing impact of the massive August floods, which affected 20 million people across an area the size of England, sweeping away 2.2m hectares of farmland.” (Guardian 27/01/11)

Throughout the period of the floods, the Pakistani ruling class appeared completely impotent, unable to competently organise relief and aid for the millions of people affected. Pakistan consistently ranks as one of the poorest countries in the world and the vast scale of corruption in daily life has been well-documented elsewhere. However, the cynicism and hypocrisy are clear when it was reported that “The Pakistan military has kept up pressure on militants in the northwest despite the devastating floods that have required major relief efforts, a top US officer said on Wednesday. Vice Admiral Michael LeFever, who oversees US military assistance in Pakistan, said Islamabad has not pulled troops out of the fight against insurgents but has had to divert some aircraft needed for rescue efforts due to the massive flooding.” (thenews.com, 06/12/10). So the priorities are clear. In fact, these comments hide the fact that in the north western provinces of Pakistan there has already been an ongoing crisis due to the effects of the earthquake which struck the region in 2005, from which the region never fully recovered, and the ongoing (and increasing) military actions there against the Pakistani Taliban. These latter have also caused significant displacements of people: estimates range from 100,000 - 200,000 people.

A similar picture emerges in Haiti a year after the quake: only 5% of the rubble has been cleared, less than 30% of promised aid has been paid. The population living in frayed tents and under tarpaulins in appalling conditions have fallen prey to a cholera epidemic, adding hundreds to the death toll. However, when the bourgeoisie want to build, even in poverty stricken Haiti where more than half the population survive on less than $1 a day, they can. The iron market in Port-au-Prince was rebuilt with earthquake protection within a year, funded by Irish billionaire Dennis O’Brien at a cost of $12 million. Whatever subjective charitable feelings he may profess, the hard truth is that capital will only build when it is profitable and as the New York Times noted “He is also keenly aware of the financial upside to getting Haiti up and running again. ‘As a company, we’re more aligned to the masses than to the elites,” Mr. O’Brien said of his interest in the market’.” (www.nytimes.com [29], 11/1/11). In fact as a BBC programme ‘From Haiti’s Ashes’ showed, the planned housing project that was supposed to go ahead alongside the rebuilding has been shelved in favour of political self-interest, replaying on a smaller scale the scramble for influence between the USA and France in the immediate aftermath of the disaster – a time when food and water seemed only able to get through to their own military personnel and NGOs. In fact aid given to disasters of the last 20 years has resulted not so much in relief of the population as in a 25% increase in the debt that will be serviced at the expense of that population (see https://en.internationalism.org/wr/2010/%252F331/Haiti [30]).

And in Sri Lanka “Victims of flooding in Sri Lanka have besieged a government office in the east of the country, accusing officials of holding back relief supplies. Windows were smashed as more than 1,000 people surrounded the office in a village in eastern Batticaloa district. Flood victims have told the BBC that some local politicians have been giving food and other aid to their supporters rather than the most needy.” (17/1/11, BBC online).

And this is without taking account of the effect of these disasters on rising food price rises and economic disruption, spreading the resulting misery far more widely.

The contribution of climate change

Monsoons, floods, heatwaves and droughts – all the extreme climate events call to mind the effects of climate change, of global warming. Climate change scientists have to be cautious about linking specific events to the overall picture. Nevertheless the British Met Office says the floods in Australia and the Philippines are linked to La Nina, and it is possible those in Brazil are also but the evidence is not clear (The Guardian 14/1/11). Similarly, the extreme events last summer, both the Moscow droughts and the Pakistan floods, were caused by the jet stream becoming fixed, making areas to the south much warmer (www.wired.co.uk [31]). In other words, there is considerable evidence that capitalism has even more responsibility for the natural disasters of the past 13 months through its impact of the world’s climate.

The bourgeoisie has made one positive contribution, not through its useless climate conferences which either cannot make a real deal (Copenhagen) or make a deal that remains a dead letter (Kyoto), not through the fraud of aid, but in creating its own gravedigger, the working class.

Alex 5/2/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Ecological Crisis [32]

- Queensland floods [33]

Rubric:

World Revolution no.342, March 2011

- 3088 reads

Our alternative:resist the capitalist regime!

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 554.35 KB |

- 3152 reads

As the government rains attack after attack on our living standards – whether through cuts in health, education, benefits and local services, through redundancies in both the private and public sector, through tuition fee increases or the abolition of EMA, or through the steadily rising price of basic necessities – the TUC has for months now been telling us to fix our gaze on the Big Demo on the 26th March. The bosses of the trade unions have argued that a very large turn-out on the day will send a clear message to the Lib-Con government, which will start carrying out its spending review at the beginning of April, involving even more savage cuts than the ones we have seen already. It will show that more and more working and unemployed people, students and pensioners, in short, a growing part of the working class, are opposed to the government’s programme of cuts and are looking for an “alternative”.

And there’s no doubt that people are increasingly fed up with the argument that we have no choice but to submit to the blind laws of a crisis-torn economic system. No choice but to accept the tough medicine that the politicians assure us will, at some point in the future, make everything all right again. There’s also no doubt that a growing number of people are not content to sit at home and moan about it, but want to go out on the street, encounter others who feel the same way, and form themselves into a force that can make the powerful of the world take notice. This is what was so inspiring about the unruly student demonstrations and occupations in the UK at the end of last year; this is why the enormous revolts that are spreading throughout North Africa and the Middle East are such a hopeful sign.

But if these movements tell us anything, it’s that effective action, action that can actually force the ruling powers to back down and make concessions, doesn’t come about when people tamely follow the orders of professional ‘opposition’ leaders, whether people like El Baradei and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt or the TUC and the Labour Party in the UK. It comes about when people begin to act and think for themselves, on a massive scale – like the huge crowds who began to organise themselves in Tahrir Square, like the tens of thousands of Egyptian workers who spontaneously came out on strike to raise their own demands, like the students here who found new and inventive ways of countering police repression, like the school kids who joined the student movement without waiting for an endless round of union ballots…..

The TUC and the Labour Party, as well as the numerous ‘left wing’ groups who act as their scouts, are there to keep protest and rebellion inside limits that are acceptable to the status quo. The TUC didn’t say very much in the period from 1997 to 2010 while its Labour friends launched a vast array attacks on workers’ living standards, attacks that the present government is just continuing and accelerating. That’s because the social situation was different – there was less danger that people would resist. Now that this danger is growing, the ‘official’ opposition is stepping in with its expertise in controlling mass movements and keeping them respectable. The trade unions do this on a daily basis by handcuffing workers to the legal rigmarole of balloting and the avoidance of ‘secondary’ action. And now, with March 26, they are doing it on a national scale: one big march from A to B, and we can all go home. And during the march itself the TUC will be working directly with Scotland Yard to ensure that the day goes entirely to their jointly agreed plans.