2013 - 151-152

- 2389 reads

Prehistory: a contribution to the discussion

- 2713 reads

The two texts of Jens published on the ICC website have to be welcomed as an expression of and stimulant to a debate that has a long and noble history in the tradition of the workers' movement, the tradition of being "radical" and going to the root of our very existence, our very beginnings. This is not, or shouldn't be, an academic exercise but one that reinforces proletarian political and historical views against those of the bourgeoisie, and strengthens our perspective of communism. There are no "class lines" in this debate but the way we see "revolutions" in the past obviously weighs on whatever analysis we might have for the revolution of the future.

My contribution is a long text, not too boring I hope, and I want to look at several distinct areas, all of which I think tend to underline my opinion in this discussion in favour of the "long view" of prehistory, the antiquity of the beginnings of culture and solidarity before the existence of homo sapiens, indeed developing in embryonic form from the ape/homo transition. In order of sequence these areas are the book Blood Relations by Chris Knight; second, some scientific observations and discoveries; third, structuralism, shamanism and prehistoric art, and fourthly Lewis Henry Morgan and his contribution to the workers' movement. I apologise if I repeat myself from previous scribblings and the first issue I want to comment on is the analysis expressed in the book Blood Relations.

Historic events:

- Human revolution [2]

- cultural explosion [3]

- palaeolithic [4]

Deepen:

People:

- Chris Knight [6]

- Friedrich Engels [7]

- Max Raphael [8]

Rubric:

Blood Relations

- 2179 reads

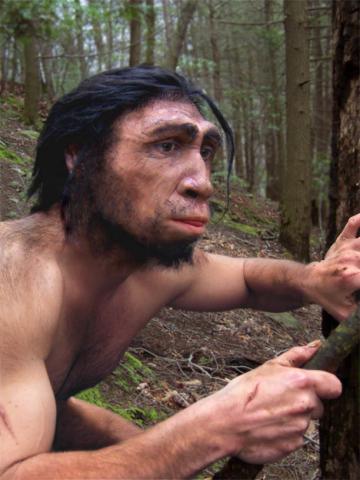

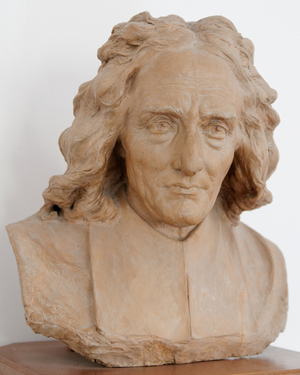

In his text Jens says that "There's a tendency to think of culture solely in material terms (stone tools, etc.)". Jens then goes on to say that culture is much more than this and I agree with his inclusion of other elements in that definition and possibly more besides. Engels called his pamphlet The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man, and in it he said "labour begins with the making of tools". Even with the very limited contemporary knowledge of timescales, Engels surmised that this transitional period took place over many thousands of years. "... the development of labour necessarily helped to bring the members of society closer together by increasing cases of mutual support and joint activity, and by making clear the advantage of joint activity to each individual". Engels here, and Pannekoek who followed this line of thought through the development of tools and the brain in his 1953 work, Anthropogenesis, is not talking about sixtythousand years ago, nor the descent of anatomically modern humans (AMH), nor ancient Homo Sapiens - because there was a transition within the Sapiens species here - but the earliest homo, the earliest of our species, and both relate the development of tools and production to the development of society from very early on. As the Harvard anthropologist Terrence Deacon put it more recently: "The introduction of stone tools and the ecological adaptation they indicate also mark the presence of a socio-ecological predicament that demands a symbolic solution; stone tools and symbols must both, then, be the architects of the Australopithecus-Homo transition and not its consequences. The large brain, stone tools, reduction in dentition, better opposability of thumbs and fingers and more complex bipedality found in post-australopithecine hominids are the physical echoes of a threshold already crossed" (T. Deacon, 1997, 348). And Pannekoek in Anthropogenesis: the "skill of handling tools is not congenital (but) acquired from older to younger generations... (the) development of the use of tools is only possible in a community".

Chris Knight doesn't like talking about tools deep in prehistory. Or rather, he doesn't like talking about them in any positive sense. When I raised this question with him in a meeting he acted as though his analysis was being sullied by such basic and ignorant questions. In relation to the earliest tools, one of the questions posed by Knight in his book is that "every male simply 'had' to be the owner of a hand-axe or other weapon, as much for reasons of personal and sexual security as to facilitate hunting or foraging?". The general gist of his argument here is that in early man there is no great advance from apes or chimpanzees regarding the earliest tools - which is a fair point regarding the very first percussion-like instruments lost in the mists of time. He does see the Acheulean hand-axe - the oldest now dated to 1.65 million (possibly 1.8) years ago in West Turkana, northern Kenya - as an advance and he does point to the survival of hominids over the period of this technology as "no small achievement". But, as well as seeing these tools as the coveted property of individuals, he calls them "monotonous" and "unimaginative" and strongly suggests that they were individual weapons (amongst other things); "fighting axes" for "settling scores". My position is that they were much more than this. I draw no conclusions from the persistence and widespread existence of these particular tools in relation to language and "home bases" - that's for another discussion. But these tools were not only very effective methods of production, they changed and practically developed, and also developed into things of beauty. Some razor sharp, too big for practical use, cubist designed, delicate with a central "feature", so-called "hand-axes" suggest that these did develop into fully symbolic pieces that, in my opinion, could well have been used in rituals. This would of course contradict Knight's view that "rituals and myths (of human symbolic behaviour were) signals for thwarting exploitation by males". Rather than being tools or weapons carried and coveted by individual males, the fact is that heaps of them, hundreds at a time, have been found in different parts of Africa (Melka Kunture in Ethiopia, Olorgesailie in Kenya, Isimila in Tanzania and Kalambo Falls in Zambia) and Swanscombe in England, crowded close together with no obvious sign of use. There's certainly no danger here, if there are hundreds of these tools lying around in great heaps on the top of the ground, in the open air, that anyone is worrying that these "valuable tools will be appropriated by some competitor or rival" as Blood Relations suggests with its social Darwinist theme of rivalry and competition in early man, "settling scores" and the like, from the males of the species. Against Knight's idea of the "monotony" of these implements there is a development of these tools. Early and late Acheulean tools do differ in very important respects (R.J. Mason, 1962). Later tools (up to around 600,000 years ago) are thinner and the flaking more shallow and while early tools are struck with hard (stone) hammers, later ones are struck with "soft" hammers of wood, bone, or antler (Chris Scarre, 2005), showing a major advance in technology. Also these more refined expressions of the Acheulean, where the core is prepared (in different ways by different individuals) in order to produce a predetermined size and shaped flake (especially the case with "soft" hammers), foreshadow the technological developments of the Middle Stone Age and eventually the Levallois technique (Thomas Volman, 1984), which takes us up to 250-500,000 years ago. It may be "slow" but there's a definite development and continuity here from the first Acheulean "hand-axes", and not the discontinuity implied in the book. And just as the "Levallois" technique grew out of the Acheulean, so did the latter grow out of the early Oldowan period, where, even at this early stage, percussion tools weren't just tools in themselves but were used to produce flakes and included hammerstones, unifacial choppers, bifacial choppers, polyhedrons, heavy-duty and light-duty scrapers, awls, discoids and flakes (Scarre, 2005). Though relatively crude, they were made out of various materials, quartz, chert, lava, quartzite, etc., (Isaac G. and Isaac B., 1997) across Africa, and some had been retouched, i.e., re-adapted. These developed from earlier, more fundamental forms that have been dated to between 2.5 to 1.5 million years ago where there were possibly around 8 species of hominin in Africa at the same time.

Blood Relations approvingly uses the archaeologist Lewis Binfords' views about the animal-like behaviour of early man - scavenger, beastly and so on. Chris Scarre (2005), editor of the Cambridge Archaeological Review, calls Binfords' views "impoverished". And this idea of early man as a "bonehead" is contested by many archaeologists: H.T. Bunn and E.M. Kroll, 1986, M. Dominguez-Rodrigo, 2002, Dominguez-Rodrigo, 2003, who all suggest from looking at hunting in this period or early access to animal carcasses and the ability to fight off or hold off other predators, that is an organised society not relying on the "hit and run" grabbing of meat.. As new sites are located this will become clearer. Binford (1984) takes an equally negative and restrictive view of hunting in the later Middle Stone Age. In his book he concludes that meat produced from the Klasies River Mouth, in South Africa in the Middle Stone Age (about 130,000 years ago), came from scavenging rather than hunting: But "his analysis ignored however, many remains that were probably removed from the site by carnivores, and many scholars would now see the remains as reflecting hunted meat that, like the shellfish at the site, was shared. There are other indications from Klasies River that suggest that hunting was probably practiced" (Scarre, 2005). Other criticisms of Binford's work is that carnivore gnaw marks are rare on the remains at Klasies and patterns of human-induced damage is very suggestive of hunting. At any rate, Binford's views of early (and later) man seem to chime with those of Blood Relations in that early man was little better than a beast (or worse in some cases)1. Another point to insist on against the book (which Jens seems to support in his text) is the large difference in male and female size, i.e., sexual dimorphism. But the evidence I've seen is that from 1.9 to 1.4 million years ago to now, sexual dimorphism, the size of early male against early female in the time scale specified, the Acheulean, has hardly changed. As Jens says, this "is generally indicative of a greater equality between the sexes". Stanford. edu puts the respective male and female height of Erectus at 1.8 and 1.55 - not much different from today. According to Christopher Ruff, 2002, 211-232, making the comparison in body mass in fossil hominins, reveals that general levels of dimorphism have likely remained more or less the same for most of the evolution of Homo over the last 2 million years to the present. Homo Erectus, who emerged 1.8 to 1.7 million years ago, achieved essentially - with significant anatomical differences - modern form and proportions; and evidence suggests the species also achieved "a social organisation that featured economic co-operation between male and female and perhaps between semi-permanent male and female units" (Scarre, 2005). This would be fully in line with the position of Engels and marxism on the general development of production going along with the general development of society. L. Hager (1989) suggests the reduction in sexual dimorphism in Homo Erectus came from the growth of females as an adaption for childbirth. As Jens says, reduced sexual dimorphism generally indicates "a greater equality between the sexes". But I think that he's wrong when he says that it's a "good deal less" in Sapiens than Erectus. The evidence seems to at least point to an equalisation that began with erectus and is virtually unchanged today. More finds as always will reveal more evidence.

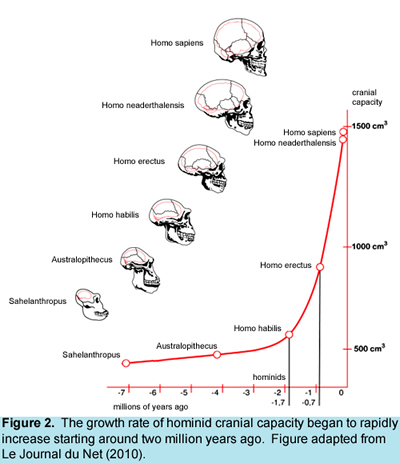

The book creates puzzles where there are none and reinforces my view that it is a source of confusion rather than clarification. For example, the "monotonous uniformity" that it puts forward in relation to the Acheulean hand-axe just doesn't exist (see above) and to say that this tool is "replicated unimaginatively all over the world - from southern Africa to northern England, from Spain to India" is not entirely true either. Knight says that it might be expected that localised conditions would have given rise to specialised tool kits for foraging whereas, in Knight's view, the Acheulean axe was also used as a digging tool (both he and Binford can't accept that there would have been hunting in this period because that would imply society). Firstly I think that tools made for the digging aspect of foraging would have generally been made of wood, bone or antler (possibly shaped by stone tools). Digging hard ground with a stone tool would only result in torn and cut hands, and antler picks, plus a stout, sharpened stick, must have been the tools of choice for digging (the male megalocerus, the giant prehistoric deer, also known as the Irish Elk, had antlers that could measure 3.5 metres from tip to tip). Discarded, shed antlers would have been plentiful and they are a very sensuous and effective tool - much better than cutting your hands to pieces trying to dig up tubers with a lump of stone! And secondly, the Acheulean hand-axe wasn't an "axe" at all and can't be reduced to a digging instrument or weapon, but was rather the prehistoric equivalent of the Swiss Army Penknife, with all-purpose, different-sized adaptable blades struck from the core. And surely the widespread use of this tool is evidence of it being fit for purpose within a community of interests over a large part of the world. The Acheulean "hand-axe" is a very effective tool-kit in itself. It's certainly a lot more than an individually-owned and closely-guarded weapon related to 'male behaviour' as Knight suggests. Even in its very beginnings the Acheulean hand-axe wasn't a single expression but variable, and has been classified into "axe", cleaver, and bifacial, i.e., several types of tools. The other point to make is that, contrary to the book, there were regional variations away from the Acheulean as long ago as 1.7 million years ago. This regional delineation goes along the "Movious Line” (H. L. Movious, 1948) which has stood up to the test of new finds since. There's a strong non-Acheulean tradition in eastern and south-eastern Asia (and some parts of Europe around modern day Germany and Romania, Greece and Turkey and parts of the now ex-Russian republics). There are no perishable artefacts, scarce by definition, but bamboo makes edges that rival or exceed those of stone for sharpness and durability. There is also evidence in east China for entirely different types of stone tools from the Acheulean tradition, "choppers", flakes and various others going back possibly 1.3 million years ago (Jianfeng Zhu et al, 2004), some two-hundred-thousand or more years after an out of Africa move. The "Zhoukoudian" (east Asia) tool kit is quite distinct from the Acheulean and includes a whole variety of tools made from sandstone, quartz and other materials. So this idea of the "boring uniformity" of Acheulean stone tools is a red herring that was contradicted well before Blood Relations was written. What we see, and what is confirmed clearly on the basis of a plethora of evidence, in variable respects throughout the global Lower Palaeolithic (the African Early Stone Age), is the development of tools and a diversity of tools that are excellent for butchery on small and large beasts and the extraction of the most nutritious parts. That's the least we can say for sure. The animal protein extraction accomplished through the use of adapted tools must provide for the evolutionary expansion of the brain. Chemical evidence supports the idea that a significant amount of animal protein in hominin diets, accomplished through the use of tools, may have provided a critical impulse to the rapid evolutionary expansion of brain size in the hominin lineage (Scarre, 2005). I think that there was hunting here (see below) but also scavenging (a tradition which continues today even in the countryside of the UK), but amounts of food were processed way in excess of the ratio of sizes to prey in relation to chimps and baboons for example. Homo erectus, 1.8/1.7 million years ago, before moving out of Africa to Asia over 1.5 million years ago, had a small braincase compared to today but it was large enough to motivate and subsequently increase it and this fed into the variation and development of new tools. From this period we move to the evidence from Boxgrove in the UK, around 400,000 years ago, showing apparently modern attributes in sophisticated hunting and butchery techniques for large mammals as well as the organisation of society that presupposes such attributes. These are confirmed with the skilful butchery at Schoningen in Germany where wooden spears have also been found and the site dated to 350,000 to 400,000 years ago (in fact recent evidence has put back the use of hafted, stone spears back to half-a-million years ago - see below). Similar spears dated to around the same time have been found elsewhere in Germany and Clacton in the UK. Apart from these two areas, wooden tools have been found in two others; Kalambo Falls (Zambia) and Gesher Benot Ya'aqov (Israel) all of them dated between 300,000 and 790,000 years ago.

The book creates puzzles where there are none and reinforces my view that it is a source of confusion rather than clarification. For example, the "monotonous uniformity" that it puts forward in relation to the Acheulean hand-axe just doesn't exist (see above) and to say that this tool is "replicated unimaginatively all over the world - from southern Africa to northern England, from Spain to India" is not entirely true either. Knight says that it might be expected that localised conditions would have given rise to specialised tool kits for foraging whereas, in Knight's view, the Acheulean axe was also used as a digging tool (both he and Binford can't accept that there would have been hunting in this period because that would imply society). Firstly I think that tools made for the digging aspect of foraging would have generally been made of wood, bone or antler (possibly shaped by stone tools). Digging hard ground with a stone tool would only result in torn and cut hands, and antler picks, plus a stout, sharpened stick, must have been the tools of choice for digging (the male megalocerus, the giant prehistoric deer, also known as the Irish Elk, had antlers that could measure 3.5 metres from tip to tip). Discarded, shed antlers would have been plentiful and they are a very sensuous and effective tool - much better than cutting your hands to pieces trying to dig up tubers with a lump of stone! And secondly, the Acheulean hand-axe wasn't an "axe" at all and can't be reduced to a digging instrument or weapon, but was rather the prehistoric equivalent of the Swiss Army Penknife, with all-purpose, different-sized adaptable blades struck from the core. And surely the widespread use of this tool is evidence of it being fit for purpose within a community of interests over a large part of the world. The Acheulean "hand-axe" is a very effective tool-kit in itself. It's certainly a lot more than an individually-owned and closely-guarded weapon related to 'male behaviour' as Knight suggests. Even in its very beginnings the Acheulean hand-axe wasn't a single expression but variable, and has been classified into "axe", cleaver, and bifacial, i.e., several types of tools. The other point to make is that, contrary to the book, there were regional variations away from the Acheulean as long ago as 1.7 million years ago. This regional delineation goes along the "Movious Line” (H. L. Movious, 1948) which has stood up to the test of new finds since. There's a strong non-Acheulean tradition in eastern and south-eastern Asia (and some parts of Europe around modern day Germany and Romania, Greece and Turkey and parts of the now ex-Russian republics). There are no perishable artefacts, scarce by definition, but bamboo makes edges that rival or exceed those of stone for sharpness and durability. There is also evidence in east China for entirely different types of stone tools from the Acheulean tradition, "choppers", flakes and various others going back possibly 1.3 million years ago (Jianfeng Zhu et al, 2004), some two-hundred-thousand or more years after an out of Africa move. The "Zhoukoudian" (east Asia) tool kit is quite distinct from the Acheulean and includes a whole variety of tools made from sandstone, quartz and other materials. So this idea of the "boring uniformity" of Acheulean stone tools is a red herring that was contradicted well before Blood Relations was written. What we see, and what is confirmed clearly on the basis of a plethora of evidence, in variable respects throughout the global Lower Palaeolithic (the African Early Stone Age), is the development of tools and a diversity of tools that are excellent for butchery on small and large beasts and the extraction of the most nutritious parts. That's the least we can say for sure. The animal protein extraction accomplished through the use of adapted tools must provide for the evolutionary expansion of the brain. Chemical evidence supports the idea that a significant amount of animal protein in hominin diets, accomplished through the use of tools, may have provided a critical impulse to the rapid evolutionary expansion of brain size in the hominin lineage (Scarre, 2005). I think that there was hunting here (see below) but also scavenging (a tradition which continues today even in the countryside of the UK), but amounts of food were processed way in excess of the ratio of sizes to prey in relation to chimps and baboons for example. Homo erectus, 1.8/1.7 million years ago, before moving out of Africa to Asia over 1.5 million years ago, had a small braincase compared to today but it was large enough to motivate and subsequently increase it and this fed into the variation and development of new tools. From this period we move to the evidence from Boxgrove in the UK, around 400,000 years ago, showing apparently modern attributes in sophisticated hunting and butchery techniques for large mammals as well as the organisation of society that presupposes such attributes. These are confirmed with the skilful butchery at Schoningen in Germany where wooden spears have also been found and the site dated to 350,000 to 400,000 years ago (in fact recent evidence has put back the use of hafted, stone spears back to half-a-million years ago - see below). Similar spears dated to around the same time have been found elsewhere in Germany and Clacton in the UK. Apart from these two areas, wooden tools have been found in two others; Kalambo Falls (Zambia) and Gesher Benot Ya'aqov (Israel) all of them dated between 300,000 and 790,000 years ago.

I don't think that I'm courting controversy when I say that Jens is something of an admirer of Chris Knight's work. But Jens has to point out the obvious. If the first signs of symbolic culture according to Blood Relations are expressed 60,000 years ago, what about the previous 140,000 years ago of Homo Sapiens history? And, if we're going to be radical in looking at the development of humanity's history, if we are going to the root of things, what about the previous nearly two-million years of clear hominin development?

But just sticking with sapiens for the moment, who themselves went through a transition from archaic to modern forms, archaeologists Sally McBrearty and Alison Brooks are firmly against the various ideas around the 50/60,000 year-old "cultural revolutions". Even if these models are transferred back to Africa, there's a certain danger of them being "Eurocentric", i.e., that this "revolution" enabled the exit from Africa leaving the latter a backwater. I'm not saying that anyone is suggesting this idea here, but it's a danger. Much more important than this is their analysis that in such models of this or that "revolution", and there are a variety of them, there's an underestimation of the depth and breadth of the advances of the African Middle Stone Age, about a 100,000 to 200,000 years before these supposed "revolutions" occurred McBrearty and Brooks see "modern" advanced technologies already present during the period in Africa 200,000 years ago: advances in lithics, increased geographical range, specialised hunting and developing hunting strategies, fishing and shell-fishing, long-distance trade and the symbolic use of pigments (Chris Stringer, 2011, 124/5). And I think that from the bits of evidence above, these technological and cultural advances were themselves linked to previous species of homo, though obviously developed from them. I'm not proposing a simple linear, "upward" development of humanity; clearly species have come to a dead-end, died out, gone backwards or moved forward at a snail's pace only. Just in homo sapien's own development there have bright sparks of sudden, dramatic technological advances that have disappeared just as quickly: Omo Kibish and Herto in Ethiopia for example 160,000 years ago; Pinnacle Point in South Africa around the same time . But that lines of human - and that for me includes homo - progress are discernible from early on is evidential. In relation to ideas around the "60,000 year-old revolution" McBrearty has said that this "quest for the 'eureka' moment... obscures rather than illuminates events in the past".

I don't find the idea of a cultural revolution from a 60,000 year old sex-strike at all credible and the only scientific validation that Jens can give to it is the earlier expression at Blombus, around 80,000 years ago, of the use of red ochre. This evidence seems to me to contradict Knight's idea especially given the much earlier antiquity of the use of pigments and this even earlier use of them also contradicts Blood Relations. At Terra Amata in the south of France, pigments were being prepared and rounded for what could likely be body decoration for a whole range of colours, including purple (purple!) 300,000 years ago. Similar finds of the use of prepared ochre among Neanderthals around a similar time scale have been found in Becov in the Czech Republic and Ambrona in Spain. Ochre can be used for many things such as an adhesive, a tanning agent, insect repellent and it even has a medical use. But the preparations of it above suggest a symbolic value a good while prior to the appearance of Sapiens. This is the case in Terra Amata particularly where it was found in a shelter that had been cut, shaped and fitted, along with a hearth. Apart from no scientific evidence for it, the tale of Blood Relation is as good or as bad a story as any other that's made up. But for me it's a source of confusion. There's obviously a lot of interesting things in the book and Jens brings many of these out. But, along with its social Darwinist leanings, I also think that the conclusion that a "cultural revolution", a real leap forward for humanity, can come about on the basis of lies, deceit, division and the woman staying at home plotting and scheming against the absent males is a repugnant one. As Joan M. Gero says, quoted by Jens: "... exploitative women are assumed always to have wanted to trap men by one means or another, and indeed their conspiring to do so serves as the very basis for our species' development" and that for men "... only good sex, coyly metered out by calculating women, can keep them at home and interested in their offspring". Jens says in his first text that Knight's work "is precisely this effort to bring together genetic, archaeological and anthropological data in a 'theory of everything' for human evolution...". My opinion of his work is different from that.

1 I'm sure that Binford wrote a lot of good stuff, but his "impoverished" and negative views of early hominins extends to Neanderthals who he said were just scavengers. Chris Stringer's own work in Gibraltar (2011), shows that this species was perfectly aware of the nutritional value of shellfish, marine mammals, rabbits, nuts and seeds. The old and tired "that wasn't known at the time" defence can't be applied here. Binford takes clear, dogmatic positions many times on the basis of what appears to be very restricted research. Binford’s (and Kent Flannery's) idea of a human "broad spectrum revolution" was similarly based upon the restricted idea that a "revolution" began around 20,000 years ago in the Middle East due to climate change and increasing population density. and he backs this up with research into an increase in diet. But C.J. Stiner and Steven L. Kuhn studies, covering a much wider space and time, have compared site data and concluded that all the main elements of a varied diet existed back to earlier sapiens and Neanderthals. See below on Neanderthal diet.

A few new old developments

- 3126 reads

I want to look at a number of recent archaeological and anthropological developments over the last dozen, 15 years or so in relation to the pre-Sapiens period and its cultural tendencies. And bear in mind, from an archaeological point of view, that the finest quality steel produced today, exposed to the atmosphere, will be dust in around twenty thousand years time.

- in Acheulean sites, as well as the functionally evolving, decidedly unmonotonous, artistically impressive "hand-axes", there have been the first finds of human introduced mineral pigment associated with Acheulean artefacts and animal bones at Kapthurin (Kenya) (Tryon and McBreaty, 2002) and at Duinefontein (South Africa) (Kathryn Cruze-Uribe et al. 2003). These are respectively dated by argon-argon dating and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) as before 285,000 and 270,000 years ago. In the German lakeside site at Bilzingsleben, where there's no Acheulean tradition, a number of artefacts have been found. The site has been dated by electron spin resonance and uranium dating as sometime between 350,000 and 420,000 years ago. An elephant's tibia has been found at this site with deliberate carvings on it. Where these markings are and the form that they take do not suggest butchery and there's a "fan-like" design here. The lines are evenly spaced and replicate each other in length and it looks like they were made at a single sitting by a single tool (Scarre, 2005). There's no suggestion from the researchers, but to me this "design" of carved lines looks very similar to the carvings on the famous Blombos piece of 80,000 years ago. Just a speculative observation. But in its turn the carvings on the Blombus piece are, I think, repeated in abbreviated form in some of the ubiquitous "signs" of Upper Palaeolithic cave art (more on this below in relation to "Structualism"). At the Acheulean site of Berekhat Ram (Golan Heights) is what looks like a female figurine which has been incised with a sharp tool to produce grooves and lines. There's a deep incision which encircles the narrower, more rounded end, making out the head and neck. And two curved incisions that could delineate arms and these are readily distinguishable from natural lines (Francesco d'Errico and April Nowell, 2000). With the site dated to around 250,000 years ago, this, if it's been deliberately modified, would be the oldest known expression of representational art.

- Following on from the above regarding Neanderthals: research work led by Dolores Piperno at the archaeobiology laboratory at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington has shown traces of cooked food on the fossilised teeth of the samples of this extinct species that they studied. There were the remains of date palms, seeds and legumes, including peas and beans in teeth from three different sites from Iraq and Belgium. These are all foods associated with modern human diet and Neanderthals must have cooked these grains in order to increase their digestibility and nutritional value. The evidence is strong as the starch grains have been gelatinised and that only comes from being cooked in water. Similar tests revealed similar results with traces of cooked starch, some traced to water lilies that store carbohydrates and others from sorghum, a kind of grass. The full research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science journal. These samples were from about forty thousand years ago but separate research two years ago in South Africa by scientists at the University of Toronto and Hebrew University (2.4.12) have dated evidence of controlled fire for the use of cooking to one million years ago. There's a "live" discussion over the dating but the University of Boston has supported these views as well as other academic research.

Sticking with Homo Neanderthalis, Dr. Penny Spikins, an archaeologist at the University of York has published a book along with others (Spikins, Rutherford and Needham, 2010) that shows this species caring for the old, infirm and vulnerable. There's the example of the Shanidar Cave (Iraq) where a man with a withered arm, deformities on both legs and a crushed skull, probably blind in one eye, which all happened at an early age, living for 20 to 35 years old with his injuries. He must have been looked after by a group of people (and remains of medicinal plants are close by). Similarly, at Simos de los Huesos (Spain) a child of the species of Homo Heidelbergensis (an ancestor of both Sapiens. and Neanderthalis.n.) was found who suffered from lamboid single suture craniosynostosis, where parts of the skull fuse together, This child would have had a strange appearance, would have been weak and a probable reduced mental capacity. This child was looked after for at least five years of its life and possibly eight. It's very difficult to find evidence like this, but these cases show the pre-Sapiens existence of the desire to care for the sick and the weak.

- Research undertaken, in part by Jayne Wilkins of the University of Toronto with her "The Function of 500,000 Stone Points", pushes back the use of stone-tipped spears two-hundred-thousand years to half-a-million years ago (Science, 16/11/12). These spears were used by Homo Heidelbergenesis. The stone points were hafted to the wooden shafts and this is a composite technology that is a multi-step process requiring different raw materials and the skill of course to put them together. The stones were found at the Kathu Pan 1 site in the Northern Cape of South Africa towards the tail-end of the Acheulean. This suggests advanced hunting strategies and a cohesive society that has been in place for a long time. A "blogger", Robert H. Garrett, has criticised these finds and their dating in a bit of a rant. But there's no doubt that stone-tipped spears existed 300,000 years ago and I'm inclined to believe the evidence of Wilkins and the separate dating teams. Garrett the blogger also thinks that modern humans "exploded out of Africa 40 to 50 thousand years ago". There is clear evidence of wooden spears being used in hunting by Homo Heidelbergensis at Boxgrove in England and sites in Germany around 400,000 years ago and these peoples were certainly experts in stone.

- Work done by a team of archaeologists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig recently discovered bones butchered by stone tools from riverbed sediments in Dikika in the Afar region of Ethiopia. This butchery was undertaken by the ancestors of early humans and puts the date of the use of stone tools right back into the Australopithicus-human transition of 3.4 million years ago, one million earlier than previously known. The marks on the bones show the tools were used to slice and scrape meat from the carcasses and where the bones were crushed to extract the nutritional marrow inside. This find is contemporary in time and place with the pre-human ancestor known as "Lucy". Until this, the oldest evidence of stone tools was a haul of more than 2,600 stone flakes estimated to be 2.5 million years old discovered in another part of Ethiopia. These latter were shaped, probably by the first human species Homo Habilis, into sharp cutting edges whereas the Dikika stones were probably used as they were found, and then discarded. Detailed analyses of the Dikada cut marks show substantial differences with tooth or claw marks made by predators with one of them embedded with a small piece of stone (Nature, 12.8.10).

- Perhaps the most remarkable and potentially most profound analysis has been that of anthropologist Professor Henry Bunn of Wisconsin University based upon fieldwork in Tanzania. Addressing the European Society for the Study of Human Evolution (ESHE), late last year, Bunn argued that our puny ancestors, Homo Habilis, two million years ago, were capable of ambushing herds of large animals after selecting individuals for the slaughter. We know that humans were omnivores and ate meat around 1.8 million years ago. Examining the animals that had been taken to the butchery site in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and "by studying the teeth in the skulls that were left, we could get a very precise indication of what type of meat these early humans were consuming. Were they bringing back creatures that were in their prime or were old or young? Then we compared our results with the kind of animals killed by lions and leopards". Bunn's analysis showed that humans preferred only adult animals in their prime, for example. Lions and leopards killed old, young and adults indiscriminately: "For the animals we looked at, we found a completely different pattern of meat preference between ancient humans and other carnivores, indicating that we were not just scavenging from lions and leopards and taking their leftovers. We were picking what we wanted and were killing it ourselves" (Bunn in The Guardian, 23.12.12). These energy-rich resources were used, along with other foodstuffs, to fuel our growing brains. Against ideas of "scavengers" and numbskull males, this research has major ramifications for the existence of society, specialised tools and the role of the male and female of the species at earlier and earlier dates.

All these finds and research are obviously open to questions, debates and criticisms but the general indication, the general tendency of the lines of research, is of much more complex and advanced archaic behaviours.

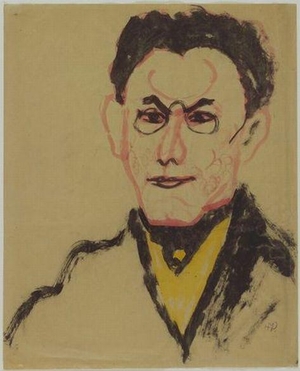

Max Raphael, structuralism, shamanism and Upper Palaeolithic art

- 3539 reads

Hopping about through millennia in this rather schematic text, I want to take a brief look at the question of "structuralism" raised by Jens in his text and particularly in relation to the Upper Palaeolithic art of Europe. Jens makes a brief mention of structuralism and a couple of mentions of Claude Levi-Strauss, his work on myths in the Americas and how the name "structuralism" is given to his work. I can't comment on anything written by Christophe Darmangeat because I haven't read any of his stuff. But I do want to comment on structuralism, its basis, the much-ignored Max Raphael and prehistoric art.

I've read some stuff by Levi-Strauss and didn't find it easy to understand what he was saying. That could be due to my limitations but the anthropologist, David Lewis-Williams writes of him (2002) as being similar to Verlaine's dictum "pas de couleur, rien que la nuance" ("no colour, nothing but nuance"), and describes his America's opus on myths as "intimidating". Edmund Leach, the social anthropologist, wrote that Levi-Strauss was "difficult to understand... combin(ing) baffling complexity with overwhelming erudition" and suggested that his work was something of a confidence trick. Levi-Strauss is called a marxist in a way that a lot of people are called "marxist", that is, they are not marxist at all. After the war he was appointed the French cultural attaché to the US and returned to France in 1948. I don't think that there's any doubt that he made a contribution to the history of structuralism and while we owe a debt to his great works, it does seem that one can conclude whatever one wants from them.

Structuralism looks to be based on the works of the Italian scholar Giambattista Vico (1668-1744) who put forward the radical idea that the world is shaped by and in the shape of the mind and therefore there must be a universal language of the mind. During the period of rapid European expansion, Vico challenged the idea that the peoples met were "primitive" or had different minds from Europeans and insisted that their myths and stories of the past were "poetic" and metaphorical. He was roundly ignored of course and the idea of "primitive" minds, "primitive" art, etc., continues to this day (I briefly used the term myself during my "primitive period" - but I'm alright now). The notion of structure (with a small "s") was further developed by the Swiss Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) who, amazingly, didn't write a book but whose ideas are known from the notes amassed and kept by his students! Saussure dealt with language and its construction and, in line with the ideas of Vico, we can see how these eventually affected "explanations" around prehistoric art. Structualism thus examines phenomena, language, art, etc., at a given time. Levi-Strauss's structuralism is played out mainly on myths and is based on binary oppositions and mediation that make up a unifying thread, a hidden logic that runs through all human thought: up/down; male/female; culture/nature; life/death, etc., and the relations between them. For Levi-Strauss "the purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction (impossible if the contradiction is real)" and because myth ultimately fails "Thus the myth grows spiral-wise until the intellectual impulse that produced it is exhausted" (Levi-Strauss, 1963). I think that this is quite profound and the Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Eugene d'Aquili, put a twist on his work and argued that myths are structured in major binary oppositions, one polarity being humankind, the other some supernatural force (David Lewis-Williams, 2002). But Vico, and in line with him, Levi-Strauss, defended the attempts of the global consciousness of the human mind against ideas of "primitivism" and the "savage mind". And Max Raphael also did so and took it further still.

Structuralism looks to be based on the works of the Italian scholar Giambattista Vico (1668-1744) who put forward the radical idea that the world is shaped by and in the shape of the mind and therefore there must be a universal language of the mind. During the period of rapid European expansion, Vico challenged the idea that the peoples met were "primitive" or had different minds from Europeans and insisted that their myths and stories of the past were "poetic" and metaphorical. He was roundly ignored of course and the idea of "primitive" minds, "primitive" art, etc., continues to this day (I briefly used the term myself during my "primitive period" - but I'm alright now). The notion of structure (with a small "s") was further developed by the Swiss Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) who, amazingly, didn't write a book but whose ideas are known from the notes amassed and kept by his students! Saussure dealt with language and its construction and, in line with the ideas of Vico, we can see how these eventually affected "explanations" around prehistoric art. Structualism thus examines phenomena, language, art, etc., at a given time. Levi-Strauss's structuralism is played out mainly on myths and is based on binary oppositions and mediation that make up a unifying thread, a hidden logic that runs through all human thought: up/down; male/female; culture/nature; life/death, etc., and the relations between them. For Levi-Strauss "the purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction (impossible if the contradiction is real)" and because myth ultimately fails "Thus the myth grows spiral-wise until the intellectual impulse that produced it is exhausted" (Levi-Strauss, 1963). I think that this is quite profound and the Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Eugene d'Aquili, put a twist on his work and argued that myths are structured in major binary oppositions, one polarity being humankind, the other some supernatural force (David Lewis-Williams, 2002). But Vico, and in line with him, Levi-Strauss, defended the attempts of the global consciousness of the human mind against ideas of "primitivism" and the "savage mind". And Max Raphael also did so and took it further still.

Max Raphael is a long-forgotten and largely ignored structuralist who predates Levi-Strauss. Raphael was also called a "marxist". I don't know what his marxism was but he was a World War One deserter and before World War Two he was incarcerated by the French security forces and on release had to keep one step ahead of the Nazis, finally fleeing to America where he died soon after. Prior to his imprisonment in France he met with Rodin, Matisse and Picasso in Paris. Just like in the west, Raphael's work was ignored in the "socialist countries". I think that Raphael was greatly affected by the conflict of World War Two and this was a weight that bore on his analysis of prehistoric art a bit too much, in that he saw all the elements of capitalism and class struggle in Upper Palaeolithic society. However, I think that his analyses were going in the right direction and I agree with his description of the Upper Palaeolithic peoples, which he called "history-making people par excellence" (David Lewis-Williams, 2002). For Raphael, their art tells us nothing about the methods of production, tools, hunting techniques, etc., but it does tell of a social struggle through a structured code. He wrote one book, Prehistoric Cave Paintings, (1945), in which he insisted on the unity and structure of the various compositions from the caves that he had visited and studied in the Dordogne region of France. This was a revolutionary analysis against previous "specialists" who insisted that this art could only be addressed each in isolation from the other and which progressed from a crude to a higher form. It was, the experts said, the first primitive attempts to paint, it was "art for art's sake", "totemism", "hunting magic" - all of which it was not (in the main). Raphael made binary oppositions between whole "compositions" that underlay the construction of this art: bison/horses for example and saw order when others only remarked on the disorder of the art. These could be male/female contradictions, conflicts or oppositions, life against death, universal human meanings. Others took his work up and did some good stuff; Annette Laming-Emperaire (who didn't mention him) and Andre Leroi-Gourhan (who, despite good work, eventually applied his analyses schematically, applying it to one painting at a time for example, which failed miserably). But Laming-Emperaire particularly followed him in important areas, with the following taken from Lewis-Williams above:

Max Raphael is a long-forgotten and largely ignored structuralist who predates Levi-Strauss. Raphael was also called a "marxist". I don't know what his marxism was but he was a World War One deserter and before World War Two he was incarcerated by the French security forces and on release had to keep one step ahead of the Nazis, finally fleeing to America where he died soon after. Prior to his imprisonment in France he met with Rodin, Matisse and Picasso in Paris. Just like in the west, Raphael's work was ignored in the "socialist countries". I think that Raphael was greatly affected by the conflict of World War Two and this was a weight that bore on his analysis of prehistoric art a bit too much, in that he saw all the elements of capitalism and class struggle in Upper Palaeolithic society. However, I think that his analyses were going in the right direction and I agree with his description of the Upper Palaeolithic peoples, which he called "history-making people par excellence" (David Lewis-Williams, 2002). For Raphael, their art tells us nothing about the methods of production, tools, hunting techniques, etc., but it does tell of a social struggle through a structured code. He wrote one book, Prehistoric Cave Paintings, (1945), in which he insisted on the unity and structure of the various compositions from the caves that he had visited and studied in the Dordogne region of France. This was a revolutionary analysis against previous "specialists" who insisted that this art could only be addressed each in isolation from the other and which progressed from a crude to a higher form. It was, the experts said, the first primitive attempts to paint, it was "art for art's sake", "totemism", "hunting magic" - all of which it was not (in the main). Raphael made binary oppositions between whole "compositions" that underlay the construction of this art: bison/horses for example and saw order when others only remarked on the disorder of the art. These could be male/female contradictions, conflicts or oppositions, life against death, universal human meanings. Others took his work up and did some good stuff; Annette Laming-Emperaire (who didn't mention him) and Andre Leroi-Gourhan (who, despite good work, eventually applied his analyses schematically, applying it to one painting at a time for example, which failed miserably). But Laming-Emperaire particularly followed him in important areas, with the following taken from Lewis-Williams above:

- "questions the value of ethnographic parallels;

- argues that the difficulty of access to many subterranean images pointed to 'sacred' intentions;

- rejects any form of totemism;

- proposes that the mentality of Palaeolithic man was far more complex than is generally supposed; and

- argues that the images should be studied as planned compositions not as scatters of individual pictures painted 'one at a time according to the needs of the hunt'.

She took up his shift into symbolic meanings and argued his position that juxtapositions and superimpositions were part of deliberately planned compositions. The recurrence of themes, the predomination of certain species (they're not generally the diet, and "hunting magic" is not the issue here), the position in the caves all have to be taken into account. Raphael rejected ethnographic analogies and puts forward the idea that these paintings and engravings of beasts were not seen as animals but images with a pre-existing shared value and suggested that the images of parietal (cave wall) and portable art (carved objects) were representative of an already existing experience and vocabulary. One that McBreaty and Brooks above say was put together in Africa some time before; this was a "gradual assemblage of the modern human adaption". Expressed in this cave art there is a repertoire of certain animals and figures, an inherent meaning to these structures before the images were made; felines are an important part, as are animal "spirit-helpers" who accomplished different and difficult tasks and also "composite", altered beasts. This is not a sudden "creative explosion" but a flowering of part of a process of clarification. Portable objects and fragments of the animals, teeth, ivory, bone as well as quartz for example, possessed these supernatural powers; and these fragments, which later were pushed into cracks in and around the pictures and engravings on the cave wall, brought these spirits back to life. The entry into the "other world" of the cave and being "pulled" along by the panels of compositions is nowhere better illustrated than Lascaux where one is gradually sucked into an intense vortex of swirling beasts and designs. This is more than religious belief and ritual but a universal envelopment into the tiered cosmos and a consciousness that is fundamental to developing human society. I think that it's important to see these paintings as expressions of pre-existing ideas and this is strengthened by the fact that, in general, portable art, small carvings of animals and anthropomorphic figures, appear at least contemporary with or some time before the cave wall art - one would think that it would be the other way around. These small carved animal figures embodied the ideas of "spirituality" that existed within the peoples and was exemplified within the shamanisms. But I'm moving away from Raphael.

For him, there's no one single imposed structure to this art but an area of struggle is strongly suggested. One can only be stunned by the obvious beauty of these carvings, engravings and paintings. But these are not the expressions of idyllic contentment and the caves are the living theatres par excellence for the unfolding dramas that they depict. There are chains being rattled here, there is some sort of an unsatisfactory situation being expressed that has to be clarified to some extent by society. The comforting chains of primitive communism were a hindrance that, as Marx said, had to be broken. This cave art is quite possibly the visual expression that had developed over time of the breaking of these chains. I think that primitive communism was a struggle and not an ideal.

Raphael also studied the much underestimated geometric motifs, the "signs" or designs that, while being culturally specific in different areas of the world, contain many similarities. These geometric signs have also been interpreted mechanically in the "primitive mind" framework, which shows, as Vico also suggests, how ethnology can do as much harm as good. In the 1920's, psychologist and neurologist Heinrich Kluver, studied these precepts on subjects under laboratory conditions (Kluver, 1942). Incidentally, in studying the minds of subjects under conditions of altered states of consciousness, Kluver preceded the work of the US military and probably contributed to it. His work determined that these subjects described "motifs" or "signs", similar to those expressed in the Upper Palaeolithic caves and his findings were validated in later works: Horowitz, 1964; Richards, 1971 and Siegal, 1977 (see chapter 9 of Shamanism and the Ancient Mind , by James L. Pearson, 2002). These concepts, or "precepts", studied by Kluver et al, are common in dreams, hypnosis, from the effects of various drugs, some mental conditions, sensory deprivation, "near-death" experiences, and so on. In an effort to tie these signs to "hunting magic" the lined and pointed "signs" have been called "spears" and the occasional red ochre painted expulsions coming from the beast's heads or snouts are supposed to show a wounded or killed animal. But the majority of these animals look very alert, in the best of health in fact, strikingly vibrant or emotive, and the blood-like expulsions from around their snouts is completely reminiscent of the bleeding noses that occur in the shamanistic "trance-dance" first noted in the 1830's by French missionaries on their visit to South Africa (Daumas and Arbosset, 1846, 246/7). Similar nasal haemorrhages have also been noted in shamans dancing themselves into altered states of consciousness (with no drugs involved) among the San groups in Africa. The shaman use their blood as a spirit of potency but everyone, men, women and children, are involved in the dance around the fire and into altered states. American anthropologist Megan Biesele, who spent a lifetime with the Ju'hoansi San and speaks their language fluently, says in Lewis Williams above: "Though dreams may happen at any time, the central religious experience of the Ju'hoan life are consciously, and as a matter of course, approached through the avenue of trance. This trance dance involves everyone in society, those who enter trance and experience the power of the other world directly, and those to whom the benefits of the other world - healing and insight - are brought by the trancers". There are expressions in Upper Palaeolithic cave art of creatures being obviously speared - I've seen them myself in the caves of Cougnac and Peche-Merle in southern France. But these are strange, human-like creatures, once again suggesting expressions of shamanism and altered states of consciousness. Piercing is an element of shaman initiation as well as its expression of being "speared" to die and be re-born. This element was also taken up by Christianity.

Humans hunted. Humans also painted - so it's quite possible that "hunting magic" was something of a factor here or there, particularly with the ties that humanity has forged with animals. Even very recently the Mundari hunters of the White Nile region of Africa drew their intended prey on the ground before going on the hunt. On their return they poured the blood and hair of the kill on the image of the animal (J. L. Pearson, 2002). But this is not the diet being shown on the cave art of the Upper Palaeolithic where "The types of animal depicted respond to a logic quite different from a culinary one" (Clottes and Lewis-Williams, 1998, 78/79). Nor does it appear to be the case in North American rock art where the diet only appears in a minority of the depictions. In the shaman "trance-dance" the animal spirit is conjured up through an altered state of consciousness, where the dancers become the animal. On the cave walls of France and Spain the animals appear as living spirits of the tiered cosmos. The danger of seeing only "hunting magic" is that it could tie in with the idea that these peoples were merely adaptive, mechanical and primitive creatures1.

Back to the signs, which are much more than primitive expressions of everyday hunter-gatherer life, and which are sometimes superimposed on various beasts: they appear to connect compositions one to the other or form "panels" on their own account, as with dots, spirals and hand-prints. Raphael assigned male/female associations to them: males, lines, phallus, killing, death and feminine, sex, woman, life-giving, which he called "a tragic dualism". These signs are not just confined to the cave walls but to portable art as well where lines, dots, chevrons, etc., are carved on these figures and, again they are mechanically interpreted as being "primitive" expressions of fur or hair. This element of signs also applies to the parietal and portable therio-anthropic creatures. Raphael demonstrated, or tried to demonstrate, the relationship of one to the other of these expressions. My opinion is that these "signs" are the first development of a written language that was generally understood and it would be interesting if it was gender-based. We don't know what was being said here and maybe will never know but the whole complexity of Upper Palaeolithic art in the caves around France and Spain shows an important expression of a social movement and points to some of the contradictions that existed therein.

We talk of "validation", of "scientific validation" and it seems to me that this means different things to different people. But in the field of structuralism and related anthropology and, one must add here the question of belief systems and shamanism (which is not quite the same thing), validation doesn't come much better than the discoveries of Chauvet Cave2, made forty years after Raphael's book, with its compositions, signs, panels, etc., which though found decades after Lascaux (which Raphael studied in depth), pre-dated it by over sixteen thousand years. Chauvet confirmed and validated in spades much of his analysis. Max Raphael deserves more of our attention and Jens must be thanked for raising the issue of structuralism. Along with Lewis Binford's "impoverished" views, there's a certain amount of snobbish mockery from some quarters of palaeontology regarding the length of the Acheulean period and its slow development- over a million years. But the conflict expressed by Upper Palaeolithic cave art itself lasted around 25 millennia, from around 35 to around ten thousand years ago and into the complexities of the Neolithic. In fact this cave art, with, in part, its universal but independently expressed symbolism, persisted long after that as a global phenomenon, particularly with the rock art of the peoples of north America, Australia, the Middle East and elsewhere. Society survived, consolidated and advanced over this period and then moved forward at an accelerated pace. From a million years, hundreds of thousands of years, tens of millennia to an even faster development.

Looking back, for a section on structuralism I haven't structured this very well. There are many differences within shamanist and structuralist expressions, but I also think that there's a profound overlap.

1 This mechanical, adaptive "idea" is supported by Lewis Binford (see above). Binford's once again restrictive approach essentially rules out a human agency of intervention and innovation but sees rather human victims of passive forces beyond their control. He has no time for the early expression of religious activity, beliefs, ritual, aesthetics, etc. As much as Raphael's were validated by them, Binford's views were soundly contradicted by the discoveries of Chauvet and Cosquer in the 1990's, but also, effectively, by the cave art in Altamira in (Spain) 1897, Le Mas D'Azil, La Madelaine, and others in the Dordogne in the 1880's. These all show, in objects and depictions, in discoveries made 50 years before Binford was born, so much more than simple, mindless adaption.

2Recent discoveries at the Abri Castanet site, close to Chauvet in the Ardeche, show zoomorphic figures, but a preponderance of painted and engraved geometric signs. especially female sexual organs. This art is thought to be older than Chauvet, with the US Proceedings of the National Academy for Sciences suggesting they are 37,000 years old. Older paintings, it is suggested, have been found in the Nerja cave of Spain, with further suggestions that these may be painted by Neanderthals. I'm not at all sure about that and much more research is needed into this but the economic crisis means that there's no more cash available for this particular project - among many others.

Lewis Henry Morgan, the punaluan family, the gentes and the defence of materialism

- 4716 reads

My approach here is a bit cack-handed (again) given the first question is a couple of stages removed, but bear with me because there are important questions here of a defence of materialism as well as the mechanics of the transition from barbarian society to class society and the state. But first a slight diversion: Jens agrees with Christophe Darmangeat when he says that no text in the workers' movement has the "status of untouchable religious texts". I also agree with that but that doesn't at all preclude the defence of positions in the workers' movement. Jens goes on: "it is absolutely obvious that we cannot take 19th century texts as the last word and ignore the immense accumulation of ethnographic knowledge since then". Well, I would back Morgan's 19th century work as a whole, and in specifics in this case, against any ethnographic knowledge since then. Ethnographic observations can be very important but like the examination of sub-atomic particles, they affect the position of what's being looked at. By its very enquiry one alters the other - as it must do. Ethnographic evidence of the 19th century will tell you what the peoples observed were saying, thinking and doing in the 19th century, and ethnographic evidence of the 21st century will tell you what the peoples observed were doing, thinking and saying in the 21st century - and, in both cases, it will also tell you what the observers were thinking, doing and saying in the relative timescales. Later ethnographic "evidence" applied further back is not necessarily more accurate - in fact it's just as likely that it will be less so. Ethnographic evidence can bring important clarifications, but it has to be approached with extreme caution. Morgan turned ethnographic quantity into the greatest quality. And as Engels said, he made conclusions from his studies using terms that Marx himself might have used.

My approach here is a bit cack-handed (again) given the first question is a couple of stages removed, but bear with me because there are important questions here of a defence of materialism as well as the mechanics of the transition from barbarian society to class society and the state. But first a slight diversion: Jens agrees with Christophe Darmangeat when he says that no text in the workers' movement has the "status of untouchable religious texts". I also agree with that but that doesn't at all preclude the defence of positions in the workers' movement. Jens goes on: "it is absolutely obvious that we cannot take 19th century texts as the last word and ignore the immense accumulation of ethnographic knowledge since then". Well, I would back Morgan's 19th century work as a whole, and in specifics in this case, against any ethnographic knowledge since then. Ethnographic observations can be very important but like the examination of sub-atomic particles, they affect the position of what's being looked at. By its very enquiry one alters the other - as it must do. Ethnographic evidence of the 19th century will tell you what the peoples observed were saying, thinking and doing in the 19th century, and ethnographic evidence of the 21st century will tell you what the peoples observed were doing, thinking and saying in the 21st century - and, in both cases, it will also tell you what the observers were thinking, doing and saying in the relative timescales. Later ethnographic "evidence" applied further back is not necessarily more accurate - in fact it's just as likely that it will be less so. Ethnographic evidence can bring important clarifications, but it has to be approached with extreme caution. Morgan turned ethnographic quantity into the greatest quality. And as Engels said, he made conclusions from his studies using terms that Marx himself might have used.

I've seen this specific criticism of Morgan's work that Jens relays from Darmangeat, a year or so ago, from an SWP member of the Radical Anthropology Group. I rather lazily moved on to something else when he describes Morgan in terms of a "capitalist speculator" (from memory, something like that). This is the specific "contradiction" of Morgan described by Darmangeat and, not having read him myself, I'll let Jens describe it: "according to Morgan the ‘punaluan’ system is supposed to represent one of the most primitive and social stages, and yet it is to be found in Hawaii, in as society which contains wealth, social inequality, an aristocratic social stratum, and which is on the point of evolving into a full-blown state and class society". My first reaction to this "contradiction" was so what? Where do you expect a ruling class to come from if not from the society that it grew up in? Of course the development towards the state came from existing society. There's nowhere else for it to come from. Let's look at the question in more detail from the point of view of the materialist Morgan.

The punaluan family (punalua, "intimate companion") is indeed extremely ancient and, with Morgan, I wouldn't like to attempt to put a date on it. It was world-wide, existing in Europe, Australia, Hawaii, Polynesia, South America and, possibly, Mongolia and China. Morgan could only hint at its beginnings: "It may be impossible to recover the event that led to its deliverance"... "it remained an experiment through an immense amount of time" until it became universal and the origins of which "belong to a remote antiquity... a very ancient condition of society" (Ancient Society OR Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilisation, Lewis Henry Morgan). It's not an invariable, monolithic system but has adaptations, variations and so on. Morgan details, over pages, the relationships of the punaluan, where peoples would address each other by their family relations rather than by name. Its greatest achievement, in laying the ground for the development of the gentes, was to be instrumental in helping to eliminate incestuous family relations, particularly between own brother and sister but also parents and their children and even first or second cousins: "the evils of which could not forever escape human observation" (LHM). As Marx put it in his Ethnographic Notes: "The larger the group recognising the marriage relations, the less the evil of close interbreeding ...". And Morgan again, "the gradual exclusion of own brothers and sisters... spreading slowly and then universal in the advancing tribes still in savagery... illustrates the principle of natural selection." There's no state here in the essence of this system, no ruling class to enforce it, its laws are organic. The change towards and into the punaluan is conflictual but radical, part of an "upward movement" as Morgan says. In punaluan relations there's a sisterhood of wives, marriage between groups of brothers and groups of sisters, which are not always taken up, while eliminating sexual relations between own brothers and sisters. Partners were held in common in the plural marriage and mother-right was strengthened. But most importantly, the punaluan laid the basis for what, in my opinion, is one of the most remarkable achievements, if not the most remarkable achievement of mankind up until then: the barbarian gentes. Morgan again: "Advancing to the civilised nations, there seems to have been an equal necessity for the ancient existence of the punaluan group among the remote ancestors of all such as possessed the gentile organisation - Greeks, Romans, German, Celts, Hebrew..." And "Such a remarkable institution of the gens would not be expected to spring into existence complete or to grow out of nothing". Just as the punaluan grew out of an even earlier form of relations, so the gentes grew out of the punaluan. And both of these forms of social organisation show an organic, collective memory and the further development of kinship ties.

The materialism of Morgan above, whatever ethnological observations have been made since, has to be defended here. And Morgan is absolutely specific on the question of the Hawaiian punaluan where he talks about the Hawaiian system containing the same elements for the germ of the gentes confined to the female branch of the custom, but: "The Hawaiians, although this group existed among them, did not rise to the conception of a gens" (my emphasis, Chapter III). So let's be clear here: the criticism of Morgan, made by Darmangeat, an SWP member of the Radical Anthropology Group and tacitly approved by Jens, is that, with Morgan's analysis, elements of the ruling class in Hawaii came from the punaluan system and this is a contradiction. But, as we see elsewhere, the superior form of the gentes, which was in turn a higher form of barbarian organisation than the punaluan, was transformed - not everywhere - into ruling elites, castes and classes. The Hawaiian punaluan did not transform into gentes, so where did the ruling class in Hawaii come from? There are only two possible explanations: either it came from the punaluan system, or it came from outer space.

The materialism of Morgan above, whatever ethnological observations have been made since, has to be defended here. And Morgan is absolutely specific on the question of the Hawaiian punaluan where he talks about the Hawaiian system containing the same elements for the germ of the gentes confined to the female branch of the custom, but: "The Hawaiians, although this group existed among them, did not rise to the conception of a gens" (my emphasis, Chapter III). So let's be clear here: the criticism of Morgan, made by Darmangeat, an SWP member of the Radical Anthropology Group and tacitly approved by Jens, is that, with Morgan's analysis, elements of the ruling class in Hawaii came from the punaluan system and this is a contradiction. But, as we see elsewhere, the superior form of the gentes, which was in turn a higher form of barbarian organisation than the punaluan, was transformed - not everywhere - into ruling elites, castes and classes. The Hawaiian punaluan did not transform into gentes, so where did the ruling class in Hawaii come from? There are only two possible explanations: either it came from the punaluan system, or it came from outer space.

In some cases elements of the punaluan persisted in the gentes that, themselves, weren't all incorporated into class society. As you would expect from an ancient and world-wide phenomenon, punaluan customs remained long into parts of civilisation in Europe, South America, Australia and Asia. Caesar notes their expression amongst some tribes of Britons, and Herodotus mentions them in the Massagetae, an Iranian nomadic confederation. Morgan is rightly wary of both witnesses here.

I don't believe that we should treat the "Old Masters" of the workers' movement with religious awe or, on the other hand, see them as "primitive" stumbling attempts to look at the development of humanity. But we should incorporate them, be very careful about the "what they didn't know at the time" type arguments and defend their materialism. I can't see any contradiction in ancient systems persisting into class society. Marx noted it in the system of the gentes persisting through the mighty Persian Empire. In civilisations all over the world ancient pre-civilised customs and forms of organisation persisted, attesting to their original scope and strength. The development into civilisation, class society and the state didn't happen through complete breaks and compartmentalised incremental steps signposted all the way. It's much more complex than that - as we can see with the gentes.

The punaluan groups contained the germs of and laid the basis for the development of the gentes, the two basic rules of which in the archaic form were:

- Prohibition of intermarriage between brothers and sisters;

- Descent in the female line (and descent from the same common ancestor).

The gentes "improved mental and moral qualities" (Morgan above) of humanity. Under the firmer establishment of mother-right, I would guess sometime in the period of the epipalaeolithic (sedentism), this organisation laid the basis for cultivation (agriculture proper), the development of the means of production (tools, ceramics, metallurgy, architecture, etc.), and contributed to the development of written language (barbarian art, in all its various forms from Europe to China, unsurpassed in beauty in my opinion, carried some of the "motifs" and "signs" of the Upper Palaeolithic parietal and portable art). It also laid the basis for private property, patriarchy, class society and the state and for Morgan's marxist conclusion that for society to survive, it must recreate the egalitarianism, the common households, the communistic tendencies and the democracy of the old gentes at a higher level: "It (a higher plane of society) will be the revival, in a higher form, of the liberty, equality and fraternity of the ancient gentes".

In relation to the transformation of the gentes into class society, Marx summed up in three simple words the profound change in the Athenian gentes: "gentilis became civis". And Shakespeare, in Titus Andronicus, his disturbing tale around the decomposition of imperial Rome, specifically pointed to the corruption of the mores of the old Roman gentes. Just like the "comforting chains" of primitive communism, the chains of the egalitarian gentes, had to be broken and from this came class society, written laws, government, human slavery, the "war of the rich against the poor", capitalism and the modern proletariat.

There was no one "civilisation" but many civilisations that, again, were universal but independent in time and space and culturally specific. And here there's no linear development either. Some forms of the barbarian gentes persisted a long way into civilisation, ironically even helping to save the Roman metropolis from the collapse of Roman imperialism. Different, changing forms of the gentes, with the absence of a state, were expressed throughout Europe and the Americas. I agree with Jens that one can't automatically tie in Morgan's social developments with those of production and I think that it's missing the point to try to do so. Morgan's 3 stages of Savagery, 3 stages of Barbarism and one of civilisation are all over the place, wildly inaccurate, out by over a three-quarters-of-million years in some places. That's not what is important about Morgan's book and Engels summary and additions to it in The Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State. Both of which, whatever punctual errors they contain (and there's no error over the Hawaiian punaluan and the class of appropriators that arose from it), should be defended as materialist explanations of our past, of where we are today and the road to take.