International Review no.151 - 2013

- 2018 reads

Editorial: Scientific advances and the decomposition of capitalism

- 2269 reads

Scientific advances and the decomposition of capitalism

The system's contradictions threaten the future of humanity

What does the present hold for the future of humanity? And is it still possible to talk of progress? What future is being prepared for our children and future generations? To answer these questions that everyone is asking today in such an anguished way, we must contrast two legacies of capitalism on which future society depends: on the one hand, the development of the productive forces which are in themselves promises for the future, notably the scientific discoveries and technological advances that the system is still capable of making; and on the other, the decomposition of the system, which threatens to destroy any progress and compromises the future of humanity itself, and which results inevitably from the contradictions of capitalism. The first decade of the 21st century shows that the phenomena resulting from the decomposition of the system, the putrefaction of a sick society[1] are growing in magnitude, opening the doors to the most irrational actions, to disasters of all kinds, generating a kind of “doomsday” atmosphere that is cynically exploited by states to create a reign of terror and thus maintain their grip on the increasingly discontented exploited.

There is a complete contrast, a permanent contradiction, between these two realities of today’s world which fully justifies the alternative posed a century ago by the revolutionary movement, notably by Rosa Luxemburg repeating the formula of Engels: either transition to socialism or a plunge into barbarism.

As for the positive potentialities that capitalism carries, this is classically, from the point of view of the labour movement, the development of productive forces, which constitutes the foundation for the building of a future human community. These forces principally consist of three elements, which are closely related and combined in the efficient transformation of nature by human labour: discoveries and scientific progress; the production of tools and increasingly sophisticated technological knowledge; and the workforce provided by the proletarians. All the knowledge accumulated in these productive forces will be usable in the construction of a new society; similarly, the workforce would be increased tenfold if the whole world population was integrated into production on the basis of human activity and creativity, instead of being increasingly rejected by capitalism. Under capitalism, the transformation, the mastery as the understanding of nature is not a goal in the service of humanity, the majority of which is excluded from the benefits of the development of these productive forces, but a blind dynamic in the service of profit. In this way, in capitalism, the majority of humanity is excluded from the benefits of the development of the productive forces.[2]

The scientific discoveries within capitalism have been numerous – not least just in the year 2012. The same real technological prowess has been paralleled in all areas, demonstrating the extent of human genius and knowledge.

Scientific advances: a hope for the future of humanity

We will illustrate our discussion with a just a few examples[3] and voluntarily leave aside many recent technological discoveries or achievements. In fact, our objective is not to be exhaustive but to illustrate how man has a growing set of opportunities concerning theoretical knowledge and technological advances, which would allow him to control nature of which he is a part, as much as his own body. The three examples of scientific discoveries that we will give touch on what is most fundamental in knowledge and which have been at the heart of the concerns of humanity since its origins:

- what is the matter that composes the universe and what is its origin;

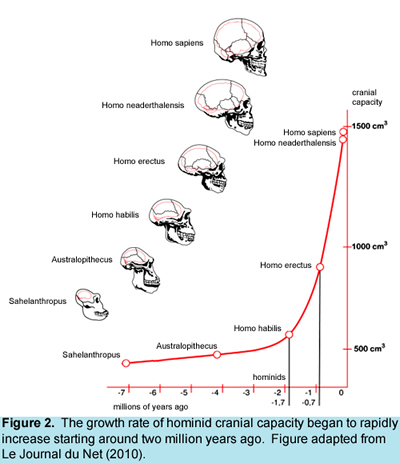

- where does our species, the human species come from;

- how to cure disease.

A better understanding of elementary particles and the origins of the universe

Basic research, while not generally contributing to discoveries with an immediate application, is nevertheless an essential component of man’s knowledge of nature and, therefore, of his ability to penetrate its laws and properties. It is from this perspective that we must appreciate the recent demonstration of the existence of a new particle, very similar in many respects to what is called the Higgs Boson, after a relentless hunt via the experiments made at CERN (European Organisation for Nuclear Research) in Geneva, which mobilised 10,000 people to work on the LHC particle accelerator. The new particle has this unique property of giving elementary particles their mass, through their interaction with them. In fact, without it, all elements in the universe would weigh nothing. It also allows a more refined approach to understanding the birth and development of the universe. The existence of this new particle had been theoretically predicted in 1964 by Peter Higgs (along with two Belgian physicists, Englert and Brout). Since then, the Higgs theory has been the subject of debates and developments in the scientific community that have led to the identification of the actual existence, not just theoretical, of the particle in question.

A potential ancestor of vertebrates that lived 500 million years ago

Illustrating the Darwinian and materialistic theory of evolution, two British and Canadian researchers have found evidence that, a hundred years after its discovery, one of the oldest animals that populated the planet, Pikaia gracilens was an ancestor of vertebrates. They examined fossils of the animal produced by different imaging techniques that allowed them to accurately describe its external and internal anatomy. With the help of a particular type of scanning microscope, they have carried out an elementary mapping of the chemical composition of fossils in carbon, sulphur, iron and phosphate. Referring to the chemical composition of present animals, they have then deduced the whereabouts of the various organs in Pikaia. Where is Pikaia on the tree of evolution? Taking into account other comparative factors with other related species found in other regions of the world, they conclude: “somewhere at the base of the chordate tree”, chordates being animals that possess a structure that prefigures the spine. Thus, this discovery allows the reconstruction one of the “missing links” in the chain of living species that have inhabited our planet for billions of years and which are our ancestors.

Towards a total cure for AIDS

Since the early 1980s, AIDS has become the leading epidemic scourge of the planet. Nearly 30 million people have already died, and despite the enormous resources deployed to fight it and the use of therapies, it still kills 1.8 million people a year,[4] far more than other particularly deadly infectious diseases such as malaria or measles. One of the most sinister aspects of this disease lies in the fact that a person who is the victim, even if they are not now condemned to a certain death as was the case at the beginning of the epidemic, remains infected throughout their life, which submits them, in addition to ostracism by part of the population, to extremely restrictive medications. And indeed, a major step in healing people infected with the AIDS virus (HIV) was taken this year by a team from the University of North Carolina. The drug which it tested on eight HIV positives has nothing to do with current antiretroviral treatments. By blocking HIV replication, these reduce the concentration of HIV in the body, to make it almost undetectable. But they do not eradicate it or heal the sick. Indeed, early in the infection, copies of the virus are hidden in some long-living white blood cells, thus escaping the action of the antiretrovirals. Hence, the idea of destroying once and for all these “reservoirs” of HIV through the action of a drug which would make the white blood cells in question recognisable by the immune system, which can then destroy them. The tested drug promisingly permits the detection of these “reservoirs”. It remains to ensure their destruction by the immune system, and even stimulate it for this purpose.

It should be immediately noted that current scientific discoveries and technological developments would occur in another type of society, especially in a communist society, where they would have already been surpassed. The capitalist mode of production based on profit, profitability, competition but also marked by chaos, irrationality, deterioration and alienation, and often the destruction of social relations, constitutes a serious obstacle to the development of the productive forces. Nevertheless, it remains a positive aspect of today's society that is still capable of producing such things, even if it significantly impedes their realisation. By contrast, decomposition as it stands today is specific to capitalism. The longer this continues, the more this decomposition will be an increasingly onerous burden on the future, the more it will obliterate it.

The morbid projection of capitalism threatens to engulf humanity

The reality of the everyday world is that the crisis of capitalism, which has reappeared and has been getting worse for decades, is the cause of the increasing difficulty of living; and it is because neither the bourgeoisie nor the working class have been able to open up a vision for society that social structures, social and political institutions, the ideological framework that allowed the bourgeoisie to maintain the cohesion of society, can only disintegrate further. Decomposition, in all its dimensions and current symptoms, shows all the morbid potential of this system that threatens to engulf humanity. Time does not favour the proletariat. In its fight against the bourgeoisie the proletariat is engaged in a “race against time”. The future of the human species depends on the outcome of the struggle between the two decisive classes in today’s society; on the proletariat's capacity to strike the decisive blows against its enemy before it is too late.

Behind the senseless killings lies the irrationality of capitalism that condemns us to live in a world that no longer makes sense

One of the most striking and dramatic signs of this decomposition recently has been the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown (Connecticut), in the United States on December 14, 2012. As in previous tragedies, the horror of this massacre of 27 children and adults by a single person has something that chills the blood. However, this is the thirteenth event of its kind in this country just in the year 2012.

The massacre of innocent lives at school is a horrible reminder of the need for a complete revolutionary transformation of society. The spread and depth of the decomposition of capitalism can only lead to further acts as barbaric, senseless and violent. There is absolutely nothing in the capitalist system that can provide a rational explanation for such an act and still less reassure us about the future of such a society.

In the aftermath of the massacre at the Connecticut school, and as was also the case for other violent acts, all parts of the ruling class have raised questions: how is it possible that in Newtown, known as the “safest town in America,” a deranged individual found a way to unleash such horror and terror? Whatever the answers suggested, the first concern of the media is to protect the ruling class and to conceal its own murderous lifestyle. Bourgeois justice reduces the massacre to a strictly individual problem, suggesting indeed that the act of Adam Lanza, the killer, is explained by his choices, his personal desire to do evil, an inclination which is inherent in human nature. Denying all the progress made for many decades by scientific studies on human behaviour which allow us to better understand the complex interaction between the individual and society, Justice claims there is no explanation for the shooter’s action and advances as a solution the renewal of religious faith and collective prayer!

This is also how it justifies its proposal to imprison all those who display deviant behaviour, reducing their crimes to immoral acts. The nature of the violence cannot be understood if one dissociates the social and historical context in which it expresses itself precisely because it is based on relations of exploitation and oppression by the ruling class on the whole of society. Mental illnesses have long existed, but it appears that their expression has peaked in a society in a state of siege, dominated by “every man for himself,” by the disappearance of social solidarity and empathy. People think they need to protect themselves against ... what exactly? Everyone is considered a potential enemy and this is an image, a belief reinforced by the nationalism, militarism and imperialism of capitalist society.

Yet the ruling class presents itself as the guarantor of “rationality” and carefully avoids the question of its own responsibility in the propagation of antisocial behaviour. This is even more flagrant in the judgments by an American army court martial of soldiers who committed atrocious acts, as in the case of Robert Bales who slaughtered 16 Afghan civilians, including 9 children. Not a word, of course, about his consumption of alcohol, steroids and sleeping pills to calm his physical and emotional pain, or the fact that he had been sent to the one of the deadliest battlefields of Afghanistan for the fourth time!

And the United States is not the only country with such abominations: in China, for example, on the day of the massacre at Newtown, a man with a knife wounded 22 children in a school. Over the last 30 years, many similar acts have been committed. Among other countries, Germany for example, another country at the heart of capitalism, has also experienced such tragedies, like the massacre in Erfurt in 2007 and especially the shooting, which took place on March 11 2009 at the Albertville-Realschule college in Winnenden, Baden-Württemberg, which caused sixteen deaths including the perpetrator. This event shows many similarities with the drama of Newtown.

The international scope of the phenomenon shows that attributing the killings to the right to the possession of weapons is primarily media propaganda. In fact, there are more individuals who feel so overwhelmed, isolated, misunderstood, rejected, that the killings perpetrated by isolated individuals or attempted suicides among young people are growing more and more numerous; and the same fact of the development of this trend shows that faced with the difficulty they have to live, they see no perspective of change that would allow them to hope for a positive evolution in their conditions of life. Many paths can lead to such extremes: in children, the insufficient presence of parents because they are overworked and morally weakened or corroded by anxiety brought about by unemployment and insufficient income or, in adults, a feeling of hatred and accumulated frustrations faced with the feeling of the “failure” of their existence.

This causes such suffering and such disorders in some people that they hold the whole of society responsible and in particular the school, one of the key institutions through which the integration of youth in society is supposed to be accomplished, which previously normally opened up the possibility of finding a job but which now often only leads to unemployment. This institution, which has in fact become the place where many frustrations are created and as many open wounds, has also become a prime target, as a symbol of the blocked future, of personality and dreams destroyed. Blind murder in the school environment – followed by the suicide of the killers – appears as the only means to show their suffering and to affirm their existence.

Behind the campaign on posting police at school doors, the idea instilled is that of distrusting everyone, which aims to prevent or destroy any sense of solidarity within the working class. All this is the origin of Adam Lanza’s mother’s obsession with firearms and her habit of taking her children, including her son, to the shooting range. Nancy Lanza is a “survivalist”. The ideology of “survivalism” is based on “every man for himself” in a pre-and post-apocalyptic world. It promotes individual survival, making arms a means of protection in order to get hold of the few remaining resources. In anticipation of the collapse of the US economy, which for the survivalists is on the brink of happening, they store weapons, ammunition, food, and teach ways to survive in the wild. Is it so strange that Adam Lanza was invaded by a feeling of “no future”? On the other hand, this means that we can only have confidence in the state and in the repression it metes out as the guardian of the capitalist system, which is the cause of the violence and horrors that we live through. It is natural to feel horror and great emotion faced with the massacre of innocent victims. It is natural to seek explanations for completely irrational behaviour. This reflects a deep need to be reassured, to have control of one’s own destiny and to lead humanity out of an endless spiral of extreme violence. But the ruling class takes advantage of the population’s emotions and uses its need for confidence to get it to accept an ideology that only the state is capable of solving the problems of society.

In the United States, this is not only on the fundamentalist margins of the Republican camp, but in a whole series of religious ideologies, creationists and others who all exert their weight on the functioning of the bourgeoisie and on the consciences of the rest of the population.

It should be clear that it is the maintenance of a society divided into classes and the exploitation of capitalism, which are solely responsible for the development of irrational behaviour, which they are incapable of eliminating or even controlling.

Wherever you look, capitalism is automatically directed towards the pursuit of profit. The left may think that contemporary capitalism remains on a rational basis, but the present experience of contemporary society reveals a worsening decomposition, one part of this society expressed in a growing irrationality where material interests are no longer the only guide to its behaviour. The experiences of Columbine, Virginia Tech and all the other massacres perpetrated by isolated individuals show that it does not need a political motive to start randomly killing any of our fellow human beings.

The generalisation of violence: delinquency, organised crime, drug trafficking and the gangster morals of the bourgeoisie

A wave of delinquency and crime shook certain cities in Brazil during the months of October and November 2012. Greater São Paulo was particularly affected, with 260 people killed during this period, but other cities, where crime is generally much lower, were also the scene of violence.

The extent of the violence is hard to doubt, as well as its impact on the population: “The police kill as well as the criminals. It is a war that we saw every day on TV”, said the director of the NGO Conectas Direitos Humanos. This new calamity only adds to the general poverty of a large part of the population.

Among the explanations for this situation, some point to the prison system, which creates criminals instead of helping their rehabilitation. But the prison system is itself a product of society and in its image. In fact, no reform of the system, the prison system or any other, can stop the phenomenon of organised crime and police repression, and therefore of terror in all its forms. And the major problem is that it will only get worse with the global crisis of this system. This is readily observable in Brazil itself. Thirty years ago, São Paulo, which today appears as the capital of crime, was a quiet town.

In the case of Mexico, we see mafia groups and the government itself enrol elements belonging to the most impoverished sectors of the population for the war they are engaged in. Clashes between these groups, which hit the population indiscriminately, leave hundreds of victims on the list of what the government and mafias call “collateral damage.” The mafias profit from the misery caused by their activities related to the production and trade of drugs, in particular by converting the poor peasants, as was the case in Colombia in the 1990s, to drug production. In Mexico since 2006, almost 60,000 people have been killed, either by the bullets of the cartels or the official army; a majority of those killed were victims of the war between the drug cartels, but this does not diminish the responsibility of the state, whatever the government says. In fact, each mafia group emerged under the protection of a fraction of the bourgeoisie. The collusion of the mafias with the state structures allows them to “protect their investment” and their activities in general.[5]

The human disasters that cause the war of the drug traffickers are present throughout Latin America, but the violence exemplified in Brazil and Mexico is a global phenomenon that is far from alien to North America or Europe.

Large-scale industrial disasters

No region of the world is spared by these and their first victims are usually the workers. Their cause is not industrial development per se, but industrial development in the hands of capitalism in crisis, where everything must be sacrificed to the objectives of profitability faced with the global trade war.

The most typical case is the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, whose gravity is only surpassed by Chernobyl (one million “recognised” deaths between 1986 and 2004). On March 11, 2011, a massive tsunami flooded the east coast of Japan. More than 20,000 people were killed, thousands are today still missing. Countless people have lost their homes. The bourgeoisie is, in fact, directly responsible for the deadly magnitude of Fukushima. For the purposes of production, capitalism has concentrated populations and industries in an insane way. Faced with this nuclear disaster, the ruling class has once again shown its negligence. The evacuation of the population started too late and the safety zone was insufficient. The government mostly avoided a large-scale evacuation because it wanted to absolutely minimise the perception of the real risks involved.

In and around the nuclear plant, recorded radiation levels reached a fatal intensity. Shortly after the disaster, the Prime Minister launched a suicide-commando of workers, many of whom were unemployed or homeless people who had to undertake the task of reducing the level of radioactivity in the plant. More than 25 years earlier, at the time of Chernobyl, the Stalinist regime in the USSR, on the verge of collapse, found nothing else to do than to send a huge army force of recruits to fight the disaster. According to WHO, about 600,000 to 800,000 “liquidators” were sent in, and hundreds of thousands have died or fallen ill due to radiation. The government has never published reliable official figures.

In a country of high technology and overcrowding like Japan, the effects are even more dramatic for the population. The irreversible contamination of the air, land and oceans, clustering and storage of radioactive waste, the permanent sacrifice of protection and security on the altar of profitability cast a harsh light on the irrational dynamic of the system at the global level.

“Natural” disasters and their consequences

Certainly, we cannot blame capitalism for being the origin of an earthquake, cyclone or drought. On the other hand, we can blame it for the fact that all these cataclysms related to natural phenomena are transformed into huge social disasters, into massive human tragedies. Thus, capitalism has the technological means to make it capable of sending men to the moon, producing monstrous weapons capable of destroying the planet dozens of times over, but at the same time it can’t afford to protect people in countries exposed to natural disasters, which it could do by building dams, diverting rivers, building houses that can withstand earthquakes or hurricanes. This does not fit into the capitalist logic of profit, profitability and cost savings.

But the most dramatic threat hanging over humanity, which we cannot develop here, is ecological catastrophe.[6]

Ideological decomposition of capitalism

This decomposition is not limited solely to the fact that capitalism, despite all the development of science and technology, finds itself increasingly subject to the laws of nature, and unable to control the means it has put in place for its own development. It also reaches the economic foundations of the system but is reflected in all aspects of social life through an ideological decomposition of the values of the ruling class, which brings with it a collapse of all values making social life possible, particularly through a number of phenomena:

- the development of nihilistic ideologies, expressions of a society that is more and more being sucked into the void;

- the profusion of sects, the revival of religious obscurantism, even in some advanced countries, the rejection of coherent, constructed, rational thought, including in some parts of the “scientific” milieu, and which through the media takes a prominent place in stultifying advertisements, mindless shows;

- the development of racism and xenophobia, of fear and therefore of hate for the other, the neighbour;

- “every man for himself”, marginalisation, the atomisation of individuals, destruction of family relationships, exclusion of the elderly.

The decomposition of capitalism reflects the image of a world without a future, a world on the brink, which it tends to impose on society as a whole. It is the reign of violence, of the “resourceful individual,” of “every man for himself”, the exclusion that plagues the whole of society, especially its most disadvantaged, with their daily lot of despair and destruction: the unemployed who commit suicide to escape their misery, children being raped and killed, the elderly tortured and murdered for a few dollars ...

Only the proletariat can get society out of this impasse

Regarding the Copenhagen summit in late 2009,[7] it was said that it was dead, that the future had been sacrificed for the present. This system has as its only horizon profit (not always in the short term), but this is more and more restricted (as illustrated by speculation). It is going straight into the wall but it cannot do otherwise! Was the former Democratic candidate for United States president, Al Gore, sincere when, in 2005, he presented his documentary An Inconvenient Truth showing the dramatic effects of global warming on the planet? In any case, he was able to do so because he was no longer “in business” after eight years’ vice-presidency of the US. This means that these people who run the world can sometimes understand the dangers involved, but whatever their moral conscience, they continue in the same direction because they are prisoners of a system that goes towards catastrophe. There is a mechanism that exceeds human will and whose logic is stronger than the will of the most powerful politics. Today the bourgeoisie themselves have children who are concerned about the future ... The looming disasters will hit the poorest first, but the bourgeoisie will also be increasingly affected. The working class not only bears the future for itself, but for all of humanity, including the descendants of the current bourgeoisie.

After a period of prosperity when it was able to achieve a quantum leap in the productive forces and wealth of society, creating and unifying the global market, this system has since the beginning of the last century reached its own historical limits, marking its entry into its period of decadence. Balance sheet: two world wars, the crisis of 1929 and the new open crisis in the late 1960s, which does not cease to plunge the world into poverty.

Decadent capitalism is the permanent, insoluble, crisis of the system itself, which is a huge disaster for all humanity, as revealed in particular in the phenomenon of increasing impoverishment of millions of human beings reduced to indigence, to abject poverty.

By prolonging itself, the agony of capitalism gives a new quality to the extreme manifestations of decadence, giving rise to the phenomenon of the decomposition of the latter, a phenomenon visible in the last three decades.

Whereas in pre-capitalist societies the relations of production of a new society in the making could hatch within the old society in the process of collapsing (as was the case for capitalism which could develop within declining feudal society), this is no longer the case today.

The only possible alternative can be the building, on the ruins of the capitalist system, of another society – communist society – which, by ridding humanity of the blind laws of capitalism, can bring full satisfaction of human needs through a development and control of the productive forces that the laws of capitalism make impossible.

Just as it is the evolution of capitalism which is responsible for the current collapse into barbarism, this means that within it, the class that produces most of the wealth, which not only has no material interest in the perpetuation of this system but, on the contrary, is the main exploited class, alone is capable by its revolutionary struggle of drawing behind it the whole non-exploiting population, of reversing the present social order to pave the way for a truly human society: communism.

So far, the class struggles which, for forty years, have developed on all continents, have been able to prevent decadent capitalism from making its own response to the impasse of its economy: unleashing the ultimate form of its barbarism, a new world war. However, the working class is not yet able to affirm, through revolutionary struggles, its own perspective or to present to the rest of society the future it carries. It is precisely this momentary impasse, where, at present, neither the bourgeois nor the proletarian alternative can affirm themselves openly, which is the origin of this phenomenon of capitalist society rotting on its feet, which explains the particular degree now reached by the extreme barbarism of the decadence of this system. And this decomposition is set to grow further with the inexorable worsening of the economic crisis.

Against the distrust of all spread by the bourgeoisie, must be explicitly opposed the need for solidarity, which means trust between workers; against the lie of the state as “protector” must be opposed the denunciation of this organ which is the custodian of the system that causes social disintegration. Faced with the seriousness of the issues posed by this situation, the proletariat must be aware of the risk of annihilation that threatens it today The working class must take from all this decay that it suffers daily, in addition to the economic attacks against all its living conditions, an additional reason, a greater determination to develop its struggles and forge its class unity.

The current struggles of the world proletariat for its unity and class solidarity constitute the only glimmer of hope in the midst of this world in total putrefaction. They alone are able to prefigure an embryonic human community. It is the international generalisation of these struggles that will finally hatch the seeds of a new world, from which will emerge new social values.

Wim / Sílvio (February 2013)

[1]. “Decomposition, final phase of the decadence of capitalism” [2], International Review n°62, 3rd quarter 1990.

[2]. It may be noted that in the early development of computers, the most powerful computers were used exclusively in the service of the military. This is much less true today for all leading areas, although military research continues to absorb and direct most advances in technology.

[3]. Information relating to these examples is mostly extracted from articles in the review Research on discoveries made in 2012.

[4]. UNAIDS figures for 2011.

[5]. See “Mexico between the crisis and narcotrafic [3]” in International Review n° 150, 4th Quarter 2012.

[6]. Read about it Chris Harman, A People's History of humanity From the Stone Age to the New Millennium (2002), especially pp.653-654 of the French edition, La Découverte, 2011

[7]. See our article “Save the planet? No they can’t! [4]” in International Review n°140, 1st Quarter 2010

General and theoretical questions:

- Science [5]

Rubric:

The Russian revolution echoes in Brazil, 1918-21

- 4702 reads

This article is a continuation of the series on the international revolutionary wave of 1917-23 that we began in International Review no.139.1

Our aim, “in continuity with the many contributions we have already made, is an attempt to reconstruct this period using the testimonies and the stories of the protagonists themselves. We have devoted many pages to the revolutions in Russia and in Germany. Therefore, we are publishing this work on lesser-known experiences in various countries with the aim of giving a global perspective. Studying this period a little, one is astonished by the number of struggles that took place, by the magnitude of the echo from the revolution of 1917.”

Between 1914 and 1923, the world experienced the first demonstration that the capitalist system was decadent - a world war that involved the whole of Europe, had repercussions all over the world and caused about 20 million deaths. This blind slaughter was brought to end, not because the various governments willed it so but because of a revolutionary wave of the international proletariat which was joined by a huge number of exploited and repressed people throughout the world and whose spearhead was the Russian revolution of 1917.

Today we are experiencing another demonstration of capitalist decadence. This time it is taking the form of a cataclysmic worsening of the economic crisis (aggravated by an enormous environmental crisis, the multiplication of local imperialist wars and an alarming moral decline). In quite a few countries,2 we see early and still very limited attempts on the part of the proletariat and the oppressed to oppose its effects. Learning the lessons of the first revolutionary wave (1917-23), understanding the similarities with and the differences from the present situation, is indispensable. The future struggles will be much more powerful if they assimilate the lessons of this experience.

The revolutionary uprising that shook Brazil between 1917 and 1919, together with the movement in Argentina in 1919, is the most important expression in South America of the international revolutionary wave.

This uprising was the fruit of the situation in Brazil, as well as of the international situation, the war and especially of the solidarity with the Russian workers and the attempt to follow their example. It did not come out of nowhere; the objective and subjective conditions had matured in Brazil too during the previous twenty years. The aim of this article is to analyse this maturation and the unfolding of events between 1917 and 1919 in the Brazilian sub-continent. We do not pretend to be able to draw definitive conclusions and are open to debate that can elucidate questions, facts and analyses, aware as we are that there are really very few documents concerning the period. In the notes we will give references for those that we have been able to use.

1905-1917: episodic explosions of struggle in Brazil

The development of the international situation during the first ten years of the 20th century is marked by three factors:

-

the long period of capitalism’s zenith draws to a close. In the words of Rosa Luxemburg, we are already “over the summit, which is on the other side of the culminating point of capitalist society”;3

-

the appearance of imperialism as an expression of the growing confrontation between the various capitalist powers, whose ambitions come up against a world market completely and unequally divided up between them. The only possible outcome of this, according to capitalist logic, is generalised war;

-

the explosion of workers’ struggles with new forms and tendencies, which express the need to respond to this new situation; this is the period in which the mass strike appears, its most important expression being the Russian revolution of 1905.

What was Brazil’s position within this context? We cannot here develop an analysis of the formation of capitalism in this country. From the 16th century, under Portuguese domination, extensive export agriculture developed, based in the first place on the Brazilian “palo”,4 and then on sugar cane from the beginning of the 17th century. It was based on slave production and as the exploitation of the Indians soon failed, from the 17th century onwards, millions of Africans were brought in. Following Independence (1821), during the last third of the 19th century, sugar was replaced by coffee and rubber, which accelerated the development of capitalism and gave rise to the mass immigration of workers coming from Italy, Spain, Germany, etc. These provided the workforce that industry needed as it began to take off and they were also sent off to colonise this vast and largely unexplored territory.

One of the first demonstrations of the urban proletariat took place in 1798, with the famous “Conjura Bahiana”;5 it was led by the cutters in particular and the rebellion demanded the abolition of slavery and Brazilian independence, as well as making its corporate demands. Throughout the 19th century, small proletarian nuclei animated the struggle for a Republic6 and for the abolition of slavery. Of course, these demands were within the capitalist framework, tending to encourage its development and also prepare the conditions for the future proletarian revolution.

The wave of immigration at the end of the century made considerable changes to the composition of the Brazilian proletariat.7 Reacting against unbearable working conditions – 12 to 14 hour days, starvation wages, inhuman living conditions,8 disciplinary measures that included corporal punishment – strikes began to take place from 1903 onwards, the most important of which were those in Rio (1903) and de Santos (the port in São Paulo) in 1905, which spread spontaneously and turned into a general strike.

The Russian revolution of 1905 made a great impression: the First of May 1906 devoted a large number of meetings to it. In São Paulo a huge meeting was held in a theatre, in Rio there was a demonstration in a public square, in Santos there was a meeting in solidarity with the Russian revolutionaries.

At the same time revolutionary minorities, mainly immigrants, began to meet together. In 1908 these meetings gave birth to the Confederação Operaria Brasileira (COB - Brazilian Workers’ Federation), which regrouped the organisations of Rio and São Paulo and was strongly influenced by anarcho-syndicalism, taking its inspiration from the French CGT.9 The COB called for the First of May celebration, carried out an important work promoting popular culture (mainly on art, education and literature) and organised an energetic campaign against alcoholism, which was a devastating problem amongst the workers.

In 1907, the COB mobilised workers for the eight hour day. From May onwards the strikes grew in number in the São Paulo region. The mobilisation was a success: the stone cutters and joiners won a reduction in the working day. But this wave of struggles quickly receded because of the defeat of the dockers in Santos (who were demanding a 10 hour day), because the economy went into recession at the end of 1907 and due to an ever-present police repression, which literally filled the prisons with striking workers and expelled militant immigrants.

The retreat of the workers’ struggles did not bring about a retreat on the part of the most conscious minorities, who devoted themselves to debating the most important questions being discussed in Europe: the general strike, revolutionary syndicalism, the reasons behind reformism... The COB organised them and gave an internationalist orientation. It campaigned against the war between Brazil and Argentina and mobilised its members against the death sentence handed out to Ferrer Guardia by the Spanish government.10

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 actively mobilised the COB, with the anarchists to the fore. In March 1915 the Workers’ Federation of Rio de Janeiro created a People’s Agitation Commission against the war, and at the same time in São Paulo an International Commission against the war was formed. On First May 1915 anti-war demonstrations were organised in the two cities, in the midst of which the workers’ International was declared.

Brazilian anarchists tried to send delegates to a Congress against the war, to be held in Spain11 and, when the attempt failed, they organised an International Congress for Peace in Rio de Janeiro in October 1915.

Anarchists, socialists, syndicalists and militants from Argentina, Uruguay and Chile attended the Congress. A manifesto addressed to the proletariat of Europe and America was drawn up, calling for them to “bring down the bands of potentates and assassins who keep the people enslaved and suffering.” Only the proletariat could realise this appeal, because it alone “is able to act decisively against the war, because it provides the elements necessary for any conflict by forging the instruments of death and destruction and by providing the human element which serves as cannon fodder.” 12 The Congress decided to carry out systematic propaganda against nationalism, militarism and capitalism.

These efforts were stifled by the patriotic agitation that broke out in favour of Brazil’s engagement in the war. Many young people from every social class joined the army voluntarily in a general climate of national defence, which made international – or simply critical – positions very difficult as they came up against the energetic repression of voluntary groups of patriots who did not hesitate to use violence. The year 1916 was very hard for the proletariat and for internationalists, who were isolated and persecuted.

July 1917, the São Paulo Commune

This situation was not to last long however. Industry was developing particularly in the São Paulo region, thanks to the lucrative trade supplying all kinds of goods to the belligerents. But this prosperity had hardly any repercussions for the working masses. It was very clear that there were two São Paulos; that of the minority, full of luxury houses and streets boasting all kinds of ‘Belle Epoch’ inventions imported from Europe and that of the majority, consisting of insalubrious districts oozing misery.

As it was necessary to act quickly in order to get the maximum profit from the situation, the bosses brutally increased the pressure on the workers: “In Brazil, discontent grew due to the atrocious working conditions in the factories, comparable to those in Great Britain at the beginning of the industrial revolution: 14 hour days with no paid rest day, workers ate next to the machines; wages were inadequate and were not paid regularly; there was no social assistance or health care; workers’ meetings and organisations were prohibited; workers had no rights and there was no indemnity for work accidents’”.13 On top of this, a high level of inflation made itself felt, especially on basic necessities. All this was conducive to the development of indignation and discontent and was further encouraged by news of the February revolution in Russia that began to arrive from Europe. In May several strikes occurred in Rio, in particular one in the textile factory of Corcovado. On 11th May, 2,500 people managed to gather in the street, intending to march towards the factory and show their solidarity in spite of the fact that a few days earlier the chief of police had expressly banned workers’ meetings. The police tried to stop the demonstration and violent confrontations ensued.

At the beginning of July a mass strike broke out in the São Paulo region, which became known as “the São Paulo Commune”. It was a reaction against the intolerable cost of living and especially against the war. In several factories the bosses had imposed a “patriotic contribution”, a tax on wages to support Italy. This tax was rejected by the workers of the Cotonificio Crespi textile factory who demanded a 25% wage increase. The strike spread like wildfire in the industrial districts of São Paulo: Mooca, Bras, Ipiranga, Cambuci... More than 20,000 workers were on strike. A group of women produced a leaflet that they distributed among the soldiers, which said: “You should not persecute your brothers in misery. You too are part of the mass of the people. Hunger reigns in our homes and our children cry for bread. The bosses rely on the weapons they’ve given you to stifle our demands”.

At the beginning of July, a breach in the workers’ ranks seemed to have opened up: the workers of Nami Jaffet agreed to return to work with a 20% rise. But there were incidents in the following days that favoured the continuation of the strike: on 8th July a crowd of workers gathered in front of the gates of Cotonificio Crespi to help two miners who were about to be arrested by an army patrol. The police went to the aid of the latter and a fixed battle ensued. On the following day there were more confrontations, this time at the gates of the Antartica beer factory. After they had got the better of the police, the workers marched towards the Mariangela textile factory and succeeded in getting its employees to stop work. More incidents occurred over the following days as well as stoppages that swelled the strikers’ ranks.

On 11th July the news circulated that a worker had been beaten to death by the police. It was the straw that broke the camel’s back: “... news of the death of a worker killed near a textile factory in Bras was felt as a challenge to the dignity of the proletariat. It acted as a violent emotional discharge which stirred up energy. The burial of the victim gave rise to one of the most impressive popular demonstrations in São Paulo.”14 A huge mourning procession took place that gathered more than fifty thousand people. After the burial the crowd divided into two, one procession moving towards the house of the murdered worker in Bras, where a meeting was held. At the end of it the crowd looted a bakery. The news spread like wildfire and many food shops were plundered in several districts.

The other procession marched towards Praca da Se, where several speakers called for the struggle to continue. Those present decided to organise themselves into several processions marching towards the industrial districts, where they approached numerous workplaces and managed to convince the workers of Nami Jaffet to come out on strike again.

The workers’ determination and unity grew spectacularly: on the night from the 11th to 12th and throughout the following day, assemblies were held in the workers’ districts with the very determined participation of the anarchists; they decided to create workers’ leagues. On the 12th the gas plant went on strike and the trams stopped running. In spite of the military occupation, the city was in the hands of the strikers.

The strikers were in control in “the other São Paulo”; the police and army were unable to get in due to being harassed by the crowd that manned the barricades at all strategic points, where violent confrontations occurred. Transport and supplies were paralysed, the strikers organised food distribution giving priority to hospitals and workers’ families. Workers’ patrols were organised to prevent theft and looting and to warn the inhabitants of police or army incursions.

The workers’ leagues of the districts, whose delegates were elected by numerous factories in struggle and by members of the COB sections, held meetings to unify the demands. This resulted, on the 14th, in the formation of a committee for proletarian defence which put forward eleven demands, of which the main ones were the freeing of all those who had been jailed and an increase of 35% for the low waged and 25% for the rest. An influential section of the bosses understood that repression was not enough and that some concessions had to be made. A group of journalists offered to act as mediators for the government. The same day a general assembly was held with more than 50,000 participants who entered the old hippodrome of Mooca in massive processions. It decided for a return to work if the demands were accepted. On 15th and 16th numerous meetings took place between the journalists and the government, as well as with a committee made up of the main employers. The latter accepted a general increase of 20% and the governor ordered the immediate release of all prisoners. On the 16th several assemblies voted for a return to work. An enormous demonstration of 80,000 people celebrated what was felt to be a great victory. Some isolated strikes broke out here and there in July-August to force recalcitrant bosses to enforce the agreement.

The São Paulo strike immediately gave rise to solidarity in the state industry of Rio Grande do Sul and in the town of Curitiba, where there were massive demonstrations. The shock wave of solidarity was late arriving in Rio. But a furniture factory was paralysed by a strike on 18th July – when the struggle in São Paulo had already finished – and it gradually spread to other companies, so that on 23rd July there were 70,000 strikers from various sectors. In panic the bourgeoisie unleashed a violent repression; police charges against the demonstrators, arrests, closure of workers’ centres. However they were forced to make some concessions, which ended the strike on 2nd August.

Although it did not manage to spread, the São Paulo Commune had an important echo throughout Brazil. The first thing to note is that it took on all of the characteristics that Rosa Luxemburg identified in the 1905 Russian revolution as defining the new form taken by the workers’ struggle in capitalist decadence. It had not been previously prepared by any organisation but was the product of a maturation of consciousness, solidarity, indignation, combativity within the workers’ ranks. The development of the movement had created its own direct mass organisations and, without losing its economic aspect, it had quickly developed a political character, affirming that the proletariat is a class that openly confronts the state. “There is nothing to show that the July 1917 general strike was prepared, organised according to the classic schemas of union and workers’ federation delegates. It was directly produced by the despair into which the São Paulo proletariat had fallen, with starvation wages and exhausting labour. There was a permanent state of siege, workers’ associations were banned by the police, their meeting places closed and the surveillance of elements considered to be ‘agitators dangerous to the public peace’ was strict and permanent.”15

As we will see later, the Brazilian proletariat, encouraged by the triumph of the October revolution, threw itself into new struggles; however the São Paulo Commune was the high point of its participation in the international revolutionary wave of 1917-23. It did not so much rise up under the direct impulse of the October revolution, as contribute to creating the international conditions that prepared it. Between July and September 1917, not only was there the São Paulo Commune but also the August general strike in Spain, mass strikes and soldiers’ mutinies in Germany in September; all of which led Lenin to insist on the need for the proletariat to take power in Russia because “The end of September undoubtedly marked a great turning-point in the history of the Russian revolution and, to all appearances, of the world revolution as well.”16

The “appeal” of the Russian revolution

To return to the situation in Brazil, the bourgeoisie seems to have been determined to participate in the world war in spite of the social turbulence, not because it had direct economic or strategic interests but rather to count for something on the world imperialist stage, to give the impression that it was powerful and to win the respect of the other national players. It took the part of what it thought would be the winning side - that of the Entente (France and Great Britain), that had managed to get the decisive support of the United States – and took advantage of the bombing of a Brazilian ship by a German vessel to declare war on Germany.

War requires the brutalisation of the population, its transformation into a people acting irrationally. With this aim in view, patriotic committees were created in every district. The President of the Republic, Venceslau Bras, intervened personally to end a strike in a textile factory in Rio. Some unions collaborated by organising “patriotic battalions” that mobilised for the war. The church declared the war to be a “Holy Crusade” and its bishops made fiery sermons full of patriotic fervour. All workers’ organisations were declared illegal, their centres closed; they were subjected to ferocious and constant press campaigns that accused them of being “heartless foreigners”, “fanatics of German internationalism” and other niceties.

The impact of this violent nationalist campaign was limited because it quickly came up against the outbreak of the Russian revolution, which electrified numerous Brazilian workers, especially the anarchist groups which defended the Russian revolution and the Bolsheviks with great enthusiasm. One of them, Astrogildo Reeira, published a collection of his writings in pamphlet form in February 1918 – A Revolucao Russa e a Imprensa – in which he defended the idea that “the Russian maximalists17 have not taken over in Russia. They are the immense majority of the Russian people, the only real and natural master of Russia. It is Kerenski and his gang who have really taken over the country abusively”. This author also defended the idea that the Russian revolution “is a libertarian revolution which opens the way to anarchism.”18

The 1917 Russian revolution had an enormous impact as an “appeal”, more at the level of the maturation of consciousness than an explosion of new struggles. The inevitable retreat after the São Paulo Commune, the realisation that gains won had been meagre even though the energy expended was great and, added to this, the pressure of patriotic ideology, which went hand in hand with the mobilisation for the war, had produced a degree of disorientation and reflection that was stimulated and accelerated by news of the Russian revolution.

The process of “subterranean maturation” – the workers appear to be passive while they are really assailed by a sea of doubts, questions and answers – gave rise to a movement of struggle. In August 1918 the strike at Cantareira (the company managing navigation between Rio and Niteroi) broke out. In July the company had given a wage increase only to those working on dry land. Feeling discriminated against, the sea-going personnel went on strike. Solidarity demonstrations took place immediately, mainly in Niteroi. On the night of 6th August, mounted police dispersed the crowd. On the 7th, soldiers of the 58th battalion of the army infantry, who had been sent to Niteroi, fraternised with the demonstrators and joined forces with them to confront the police and other army divisions. There were serious confrontations which ended in two deaths: a soldier of the 58th battalion and one civilian. Niteroi was flooded with other troops who managed to establish order. The dead were buried on the 8th, a huge crowd processed peacefully. The strike ended on the 9th.

Was the enthusiasm aroused by the Russian revolution, the development of demand struggles, the mutiny of an army battalion, a sufficient basis for initiating an insurrectionary revolutionary struggle? A group of revolutionaries in Rio answered this question affirmatively and began preparing the insurrection. Let’s examine the facts.

In November 1918, an almost total general strike took place in Rio de Janeiro, demanding an 8 hour day. The government dramatised the situation by claiming that this movement was an “attempt at insurrection”. Certainly the dynamic provided by the Russian revolution, and the joy and relief at the ending of the world war, gave an impulsion to the movement. Without doubt, in the last analysis any proletarian movement tends to unite the fight for immediate demands and for a revolutionary aspect. However the struggle in Rio did not spread to the whole country, it did not organise itself or show evidence of a revolutionary consciousness. But some groups in Rio believed that the moment had come for a revolutionary assault. Another factor raised spirits: one of the most serious sequels to the world war was a terrible epidemic of Spanish flu,19 which eventually reached Brazil. Rodriguez Aloes, the president of the Republic, succumbed to it before his investiture and had to be replaced by the vice-president.

A council claiming to organise the insurrection was formed in Rio de Janeiro, without even co-ordinating with the other large industrialised centres. The anarchists participated in it, as well as workers’ leaders from the textile industry, journalists, lawyers and a few military men. One of these, Jorge Elias Ajus, was no more than a spy who informed the authorities about the Council’s activities.

The Council held several meetings, which distributed tasks among the workers of the factories and the districts: to take over the presidential palace, to occupy the arms and ammunitions depots of the Commissariat of War, an assault on the ammunitions factory of Raelengo, an attack on the police station, occupation of the electricity plant and the telephone exchange. Twenty thousand workers were expected to carry out these actions, which were planned for the 18th.

On 17th November, Ajus made a dramatic gesture: “He stated that, as he was not on duty on the 18th, he could not participate in the movement and asked that the date of the insurrection be postponed to the 20th.”20 The organisers were shaken but, after a great deal of hesitation, they decided to stick to what they had decided. But during the last meeting, that was held on the 18th in the early afternoon, the police raided the premises and arrested most of the leaders.

On the 18th a strike broke out in the textile and metal industries but did not extend to other sectors and the leaflets circulating in the barracks calling for the soldiers to mutiny had little effect. The call to form “workers’ and soldiers’ committees” was a failure in the factories as well as in the barracks.

A large assembly was planned at Campo de San Cristobal, from where columns were to leave to occupy governmental and strategic buildings. There were no more than a thousand participants and they were rapidly surrounded by army and police troops. The other actions planned were not even engaged and the attempt to dynamite two electricity towers failed on the 19th.

The government imprisoned hundreds of workers, closed union offices and banned all demonstrations and meetings. The strike began to retreat on the 19th and the police and army went systematically to all striking factories to force the workers to return to work at bayonet point. The few attempts at resistance resulted in the death of three workers. On 25th November order reigned in the region.

1919-21 – Decline of the social unrest

In spite of this fiasco, the flame of workers’ combativity and consciousness burned still. The proletarian revolution in Hungary and the triumph of the revolutionary commune in Bavaria inspired great enthusiasm. Enormous demonstrations took place in lots of cities on 1st May. In Rio, São Paulo and Salvador da Bahia, resolutions were voted in support of the revolutionary struggle in Hungary, Bavaria and Russia.

In April 1919, the constant price increases gave rise to enormous discontent among the workers of many factories in and around São Paulo, in San Bernardo do Campo, Campinas and Santos. Some partial strikes took place here and there which formulated lists of demands but the most important occurrence was that general assemblies were held and that they decided to elect delegates to set up a co-ordination. This resulted in the constitution of a general workers’ council that organised the 1st May demonstration and drew up a series of demands; eight hour day, wage increases linked to inflation, abolition of the employment of children under 14 and of night work for women, reduction in the price of basic necessities and in rents. On 4th May the strike generalised.

The government and capitalists acted on two levels; on the one hand savage repression to prevent demonstrations or any possibility of workers getting together. They persecuted those thought to be the leaders, who were imprisoned without trial and deported to the distant reaches of Brazil. On the other hand the bosses and government showed that they were prepared to make concessions and, little by little, sowed all possible divisions; by increasing wages here, reducing the working day there, etc.

This tactic was successful. At the Santa Catalina pottery works the strike ended on 6th May on the promise of an eight hour day, the abolition of child labour and a wage increase. The Santos port workers went back to work on the 7th. On the 17th it was the turn of the national textile factory. The need to act in unison was never considered (to return to work only if the demands were granted to all), nor was the possibility of spreading the movement to Rio, although numerous strikes had broken out in the city since mid-May and they had adopted the same platform of demands. Once calm had been restored in the region of São Paulo, the strikes in the states of Rio, Bahia and the town of Recife, although massive, were eventually suffocated by the same tactic combining limited concessions and selective repression. A mass strike at Porto Allegre in September 1919 which began at the Light and Power Electricity Company with the demand for a salary increase and a reduction in working hours, won the solidarity of the bakers, the conductors, the telephone workers, etc. The bourgeoisie had recourse to provocation – bombs were placed to blow up some installations of the electricity company and the house of a strike-breaker – in order to prevent demonstrations and assemblies. On 7th September, a mass demonstration in Montevideo Square was attacked by the police and army, resulting in the death of a demonstrator. The next day numerous strikers were arrested by the police and union offices were closed down. The strike ended on 11th without any of its demands having been met.

Exhaustion, the absence of a clear revolutionary perspective and concessions granted in many sectors, brought about a general retreat. The government then intensified the repression; they unleashed a new wave of arrests and deportations, closed down the workers’ centres and facilitated disciplinary sackings. Parliament passed new repressive laws; any provocation sufficed – a bomb set off in the vicinity of known militants or in a place that they frequented – for these repressive laws to be applied. An attempt at a general strike in São Paulo in November 1919 failed miserably and the government took advantage of it to further ensnare the workers; it imprisoned all those who could be considered the leaders; they were then brutally tortured in Santos and São Paulo before being deported.

However the workers’ combativity and the general discontent had its swan song in March 1920; the strike at the Leopoldina Railways in Rio and that of Mogiana in the region of São Paulo.

The first took place on 7th March with a platform of demands to which the company responded by using public sector employees as “scabs”. The workers appealed for solidarity by going out onto the streets every day. On the 24th the first wave of strikes in support of them began: metal workers, taxi drivers, bakers, tailors, building workers... A general assembly was held which called for “all the working class to present its complaints and demands”. On the 25th the workers in the textile industry joined it. There was also a solidarity strike in the transport sector in Salvador and in towns of the Minas Gerais state.

The government responded with brutal repression and on 26th March threw more than 3,000 strikers in gaol. The latter were so full that they had to use the port warehouses to imprison the workers.

The movement began to retreat on 28th with the return to work of the workers in the textile industry. The reformist unionists acted as “mediators’’ for businesses to rehire “good workers” who had “at least five years’ experience”. The workers’ ranks were routed and on the 30th the struggle ended without having won any of its demands at all.

The second, which began on the railway line north of São Paulo, lasted from 20th March to 5th April and received the solidarity of the Workers’ Federation of São Paulo, which called for a general strike that was followed in part in the textile industry. The strikers occupied the stations and tried to explain their struggle to those travelling but the regional government was intractable. The occupied stations were attacked by troops which resulted in a number of violent confrontations, especially in Casa Branca where four workers were killed. A savage press campaign was orchestrated against the strikers together with a brutal repression which made numerous arrests and deportations not only of the workers but also of their wives and children. Men, women and children were imprisoned in barracks, where vicious corporal punishment was inflicted on them.

Some elements towards an assessment

The movements in Brazil between 1917 and 1920 were undeniably part of the revolutionary wave of 1917-23 and can only be understood in the light of its lessons. The reader can consult two articles in which we have tried to make an assessment.21 Here we will restrict ourselves to putting forward a few lessons which come directly out of the experience in Brazil.

The fragmentation of the proletariat

The working class in Brazil was very fragmented. Most of the workers had immigrated recently and had very few ties with the native proletariat, who were very much bound to artisan production or were day labourers in the huge and totally isolated agricultural plantations.22 The immigrant workers were themselves divided into “language ghettos”, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, German, etc: “In São Paulo more Italian, with its various picturesque dialects, was spoken than Portuguese. The influence of the language and culture of the peninsula influenced all aspects of life in São Paulo.”23

The enormous dispersion of the industrial centres must also be considered. Rio and São Paulo never managed to synchronise their struggles. The São Paulo Commune spread to Rio only when the struggle was over. The attempt at insurrection in November 1918 remained limited to Rio without the possibility of common action being raised either with São Paulo or Santos.

To the dispersion of the proletariat must be added the weak echo that the workers’ agitation had within the peasant masses – who constituted the majority of the population – not only in far flung regions (Mato Grosso, Amazon, etc.) but also in those which endured conditions close to slavery in the coffee and cocoa plantations.24

The fragmentation of the proletariat and its isolation from the rest of the non-exploiting population gave an enormous margin of manoeuvre to the bourgeoisie which, after making some concessions, was able to unleash a brutal repression.

Illusions about capitalist development

The world war revealed the fact that capitalism, by creating the world market and so imposing its laws on every country in the world, had reached its historic limits. The Russian revolution showed that the destruction of capitalism was not only necessary but also possible.

However there were illusions about capitalism’s ability to go on developing.25 In Brazil there was an enormous area to colonise. As in other countries on the American continent, including the United States, the workers were very vulnerable to the “pioneer” mentality, to the illusion of “trying to make their fortune” and of making their way through agricultural colonisation or by discovering mineral deposits. Many immigrants saw their status as workers as a “transitory period” which would enable them to realise their dreams and turn them into wealthy colonialists. The defeat of the revolution in Germany and other countries, the growing isolation of Russia, the serious mistakes made by the Communist International on the possibility of capitalist development in the colonial or semi-colonial countries, encouraged this illusion.

The difficulty in developing an internationalist momentum

The Commune of São Paulo was a contribution of the Brazilian proletariat to the international maturation of the conditions that made the October revolution possible, at the same time as it was inspired by the latter. As in other countries, there existed the seeds of an internationalist attitude, which is the indispensable departure point for the working class revolution.

It is by placing itself on an internationalist terrain that the proletariat creates the basis for overthrowing the state in every country, but to do so it must fulfil three conditions: the unification of revolutionary minorities into a world party; the formation of workers’ councils, and their growing co-ordination on a world scale. Not all of these three conditions were present in Brazil:

1) contact with the Communist International was made very late, in 1921, when the revolutionary wave was receding and the CI was already in the process of degeneration;

2) the workers’ councils were never formed, except for some embryonic attempts by the São Paulo Commune in 1917 and during the mass strike of 1919;

3) links with the proletariat in other countries were practically non-existent.

The lack of theoretical reflection and the activism of the revolutionary minorities

The majority of the proletarian vanguard in Brazil was formed by militants of the internationalist anarchist tendency.26 To their credit they defended anti-war positions and they supported the Russian revolution and Bolshevism. They were the ones who, in 1919, on their own initiative and without having any contact with Moscow, created a Communist Party in Rio de Janeiro, which encouraged the COB to join the CI.

But they did not have an historic, theoretical and international stance: they based everything on “action” that was to bring the workers into struggle. Consequently, all their efforts were focused on the creation of unions and on calling for demonstrations and protest actions. Theoretical work to identify the aims of the struggle, the means to achieve them, the obstacles in its way and the conditions necessary for its development was completely neglected. In other words, they neglected all the elements that are indispensable for the movement to develop a clear consciousness, for it to see the direction it should take, to avoid the traps so as not to become the plaything of events and of the manoeuvres of an enemy – the bourgeoisie – that is politically the most intelligent exploiting class in history. This activism proved fatal. An important indication of this, as we have seen, was the failure of the insurrection in Rio in 1918, from which no lesson was drawn, as far as we know.

C.Mir, 24 November 2012.

1. International Review nº 139, 1914-23: Ten years that shook the world [7]

2. See the contribution to an evaluation of these experiences “2011, from indignation to hope [8]”.

3. Rosa Luxemburg, The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions, chapter VII [9],

4.This is a large tree (Caesalpinia echinata) whose trunk contains a highly valued red dye; the intense exploitation of it has led to its almost complete disappearance.

5. See the article on Wikipedia in Spanish [10].

6. Up until the coup d’etat in 1889, Brazil was an empire with an Emperor descended from the Portuguese dynasty.

7. Between 1871 and 1920, 3,900,000 immigrants from southern Europe are estimated to have arrived.

8. The introduction to the article “Trabalho e vida do aperairiado brasileiro nos seculos XIX e XX”, by Rodrigo Janoni Carvalho, published in the review Arma da Critica, An.2, nº.2, March 2010, contains a horrific description of the São Paulo proletariat’s lodgings at the beginning of the 20th century. There could be up to twenty people sharing a lavatory.

9. At the time, the French CGT was a reference point for workers disgusted by the growing opportunism of the Social Democratic parties and the increasingly conciliatory attitude of the unions. See International Review nº 120, Anarcho-syndicalism faces a change in epoch: the CGT up to 1914 [11]

10. “Francisco Ferrer Guardia (Alella, 1859-Barcelona, 1909) was a famous Spanish libertarian teacher. In June 1909 he was arrested in Barcelona, accused of having instigated the revolt known as ‘the week of tragedy’. Ferrar was found guilty by a military tribunal and, on 13th October 1909 at 9 o’clock in the morning, he was shot by firing squad in the Montjuic prison. It is generally acknowledged that Ferrer had nothing to do with the events and that the tribunal condemned him without having any proof against him” (wikipedia in Spanish [12], translated by us).

11. See International Review nº 129, History of the CNT (1914-19): The CNT faced with war and revolution [13]

12. Pereira, “Formacao do PCB”, quoted by John Foster Dulles, Anarquistas e comunistas no Brasil, p.37.

13. Cecilia Prada, “The 1917 barricades; the death of an anarchist cobbler provokes the first general strike in the country”.

14. Quoted in the article “Tracos biograficos de um homem extraordinario”, Dealbar, São Paulo, 1968, an 2, nº 17, about the anarchist militant, Edgard Leuenroth, who was an active participant in the São Paulo strike.

15. Everardo Dias, Historia das lutas sociais no Brasil, p.224.

16. Lenin, “The crisis has matured [14]”.

17. This is what the Bolsheviks were called in the press.

18. John Foster Dulles, Anarquistas e comunistas no Brasil p.63.

19. “The Spanish flu [15] (also known as The Great Flu Epidemic, the Flu Epidemic of 1918 or The Great Flu) was a flu epidemic of a dimension previously unknown (…). It is considered the worst epidemic in the history of humanity, causing between fifty and a hundred million deaths throughout the world between 1918 and 1920. (…). The Allies in the First World War called it the ‘Spanish flu’ because the epidemic drew the attention of the press in Spain whereas it was kept secret in the countries engaged in war as they censored information concerning the weakening of the troops affected by the illness.”

20. Anarquistas e comunistas no Brasil p.68.

21. See International Review nº 75, “The Russian Revolution, Part III [16]”, , and International Review nº 80, “The First Revolutionary Wave of the World Proletariat [17]”.

22. Ever since the 1903 strikes, in which native day labourers and peasants had been used as “scabs”, there had been mistrust and rancour between immigrant workers and native workers. See the essay, in English, by Colin Everett, Organised Labour in Brazil, 1900-1937 [18].

23. Barricadas de 1917, Cecilia Prada, doctoral thesis.

24. According to our information, the most important peasant movement took place in 1913 and gathered more than 15,000 strikers, settlers and day workers.

25. These illusions also affected the Communist International, which envisaged the possibility of national liberation in the colonial and semi-colonial countries. See the "Theses on Fundamental Tasks" from Second Congress of the Communist International [19].

26. To our knowledge, there were very few marxist groups. It was only in about 1916 (after an abortive attempt in 1906) that a Socialist Party was formed, which rapidly divided into two equally bourgeois tendencies, one for Brazil’s participation in the world war and the other defending its neutrality.

Historic events:

Geographical:

- Brazil [23]

Deepen:

People:

- Ferrer Guardia [25]

- Venceslau Bras [26]

Rubric:

The choice is imperialist war or class war

- 2552 reads

The North African and Middle Eastern countries, hard-hit by the effects of the world economic crisis, were also shaken throughout 2011 by social unrest. The social events that followed the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi have still not been fully extinguished even today. Following these events, the governments and even the regimes of many Southern Mediterranean countries were compelled to change or step down.

These movements which went into history as the ‘Arab Spring’ are changing the entire political structure of North Africa and the Middle East. The global or regional bourgeoisies are trying to reestablish the political balance.

Evaluating the situation in Egypt and Syria, two countries where the social unrest and clashes aren't at an end yet, is important because there is a need for a correct analysis, especially given the recent exacerbation of the Egyptian streets following the football provocation in the town of Port Said and the protests against the Muslim Brotherhood regime, and the increasing importance of the war in Syria with the escalating regional imperialist conflict in the background. This will necessarily mean we will have to also deal with other conflicts in this region of ever-heated imperialist tensions, which rivals the economic crisis in the US and the EU for the spotlight of the world's attention. Thus in order to explain the meaning of what is going on in the Middle East, we will try to explain the aggressive foreign policy of Iran in the region, as well as Turkey's efforts to become a regional actor and the side it took in the Syrian war by supporting the opposition, as well as the attitudes of other countries.