2012 - 148 to 150

- 2626 reads

International Review no.148 - 1st Quarter 2012

- 2332 reads

The economic crisis is not a never-ending story

- 2382 reads

Since 2008, not a week has gone by without a new draconian austerity plan. Reductions in pensions, tax increases, wage freezes... nothing and nobody can escape. The whole of the world working class is sinking into poverty and insecurity. Capitalism is being hit by the most acute economic crisis in its entire history. The current process, left to its own logic, can only lead to the collapse of capitalist society. This is shown by the complete impasse facing the bourgeoisie. All the measures it takes are revealed as vain and fruitless. Worse! They are actually aggravating the problem. This class of exploiters no longer has any answers, even in the medium term. The crisis did not level out in 2008; it is getting worse and worse. And the impotence of the bourgeoisie is leading to tensions and conflicts in its ranks. The economic crisis is turning into a political crisis.

In the last few months, in Greece, Italy, Spain, the US... governments are becoming more and more unstable, increasingly unable to impose their policies as divisions between different factions within the national bourgeoisie grow in strength. The different national bourgeoisies are also often divided amongst themselves on a global scale when it comes to deciding what measures to take against the crisis. The result of all this is that measures are frequently only taken after months of delay, as we saw with the eurozone’s plan for bailing out Greece. As for the current anti-crisis measures, like the ones that came before them, they can only reflect the growing irrationality of the capitalist system. Economic crisis and political crisis are banging simultaneously on the door of history.

However, this major political crisis of the bourgeoisie is not in itself something that can be celebrated by the exploited. In the face of the danger of class struggle, the bourgeoisie maintains a sacred union, an iron discipline against the proletariat. However difficult the task facing the working class, it holds in its hands the power to destroy this dying world order and to build a new society. This goal can only be attained collectively, through the generalisation of the proletariat’s own struggles.

Why can’t the bourgeoisie find a solution to the crisis?

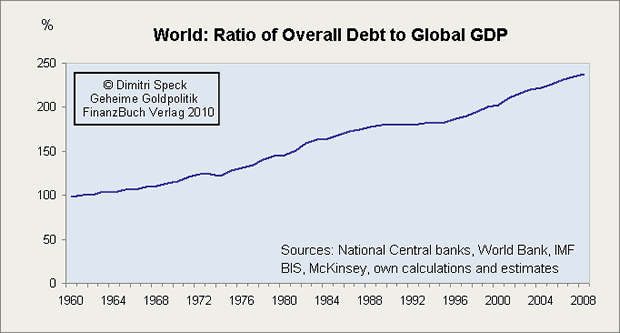

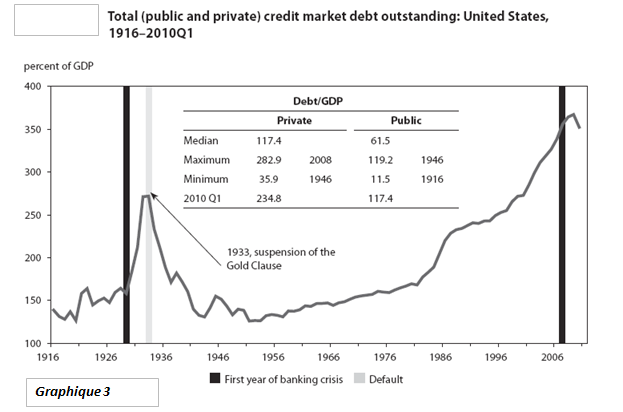

In 2008 and 2009, despite the gravity of the world economic situation, the bourgeoisie breathed a sigh of relief as soon as the situation seemed to stop getting worse. To believe them, the crisis was just a passing event. The ruling class and its servile specialists claimed in all languages that they had the situation in hand, that everything was under control. The world was merely seeing an adjustment of the economy, a small purge needed to eliminate the excesses of previous years. But reality has mocked the lying discourse of the bourgeoisie. The last quarter of 2011 has seen a whole series of international summits, every one of them described as “last chance meetings” aimed at saving the eurozone from falling apart. The media, conscious of this danger, talk of little else but the “debt crisis”. Every day the papers and the TV are filled with their analyses, each one in contradiction with the next. There is a real note of panic in their voices. And even then they often forget that the crisis is continuing to develop outside the eurozone: the USA, Britain, China, etc. World capitalism is faced with a problem which it cannot solve. This can be represented by the image of a wall that cannot be scaled: the “wall of debt”.

For capitalism, its overall debt has become fatal. It’s true that a debt in one part of the world is equal to a loan somewhere else, so that some people claim that world debt actually stands at zero. But this is a pure illusion, a clever accountant’s trick, a game written on paper. In the real world, all the banks for example are in a more or less permanent situation of bankruptcy. And yet their accounts are “balanced”, as they like to put it. But what is the real value of their shares in the Greek or Italian debts, or the ones in Spanish or US housing loans? The answer is clear: virtually nothing. The tills are empty and all that remains is debt and more debt.

But why, at the beginning of 2012, is capitalism facing such a problem? What is the origin of this ocean of money loans which has for so long been totally disconnected from the real wealth of society? Debt has its source in credit. These are the loans agreed by central or private banks to all the economic agencies in society. These loans become a barrier for capital when they can no longer be paid back, when it becomes necessary to create new debts to pay the interest on previous debts or to reimburse a small fraction of the actual debts.

Whichever organism gives out the money, whether central banks or private ones, it is vital, from the standpoint of global capital, that enough commodities are sold for a profit on the world market. This is a condition for the survival of capital. But this hasn’t been the case for the last 40 years. In order for all the commodities produced to be sold, it has become necessary for money to be loaned to pay for the goods, to reimburse previously contracted debts, and to pay back the interest accumulated on them. And this has meant contracting new debts. The time comes when the overall debt of particular banks or states can no longer be honoured, and in more and more cases this goes for the servicing of the debts. This marks the general crisis of debt. This is the moment when debt and the creation of growing amounts of fictitious money have become a poison contaminating capitalism’s entire body.

What is the real gravity of the world economic situation?

The beginning of 2012 has seen the world economy fall back into recession. The same causes always produce the same effects, but at a more serious and dramatic level. At the beginning of 2008, the financial system was on the verge of collapse. The new credits injected into the economy were soon eaten up and the economy went into recession. Since then, the American, British and Japanese central banks, among others, have injected further billions of dollars. Capitalism bought itself some time and was able to revive the economy in a very minimal way while preventing the banks and assurance companies from going under. How did all this turn out? The answer is now known. States are massively in debt to the central banks and the markets are taking over a very small part of the debt of the banks. Nothing has really changed.

At the beginning of 2012, the impasse facing global capital can be illustrated, among other things, by the €485bn earmarked by the European Central bank to save the banks in the zone from immediate bankruptcy. The ECB has lent money to the central banks of the zone in exchange for toxic shares. Shares which are part of the state debts of this zone. The banks in turn then have to buy up new state debts for those which are not collapsing. Each is holding up the next, each one is buying the next one’s debt with what is in effect money printed for the purpose. If one goes down, they all go down.

As in 2008, but in a much more drastic way, credit is no longer going into the real economy. Each player protects his own money in order to avoid collapse. At the beginning of this year, at the level of the private economy, investments in enterprises are becoming very rare. The impoverished populations are pulling in their belts. The depression is with us again. The eurozone, like the USA, has a near-zero growth rate. The fact that the USA saw a slightly better economic activity in comparison to the rest of the year does not mean any lasting change in the general tendency. In the short term, according to the IMF, growth in 2012 will be between 1.8% and 2.4% depending on the country. And then again, that’s if “everything goes well”, ie. if there is no major economic event, something noone would care to bet on right now!

The “emerging” countries, like India and Brazil, are seeing a rapid reduction in activity. Even China, which since 2008 has been presented as the new locomotive of the world economy, is officially going from bad to worse. An article on the website of the China Daily on 26th December said that two provinces (one being Guandong which is one of the richest in the country since it hosts a large part of the manufacturing sector for mass consumer products) have told Beijing that they are going to delay the payments on the interests for their debt. In other words, China is also faced with bankruptcy.

2012 is going to see a contraction of world economic activity on a scale which no one can yet predict. At best, world growth is calculated to be around 3.5%. In December, the IMF, OECD and all the economic think tanks revised their predicted growth figures downwards. It seems clear that the colossal injection of new credit in 2008 created the present wall of debt. Further debts contracted since then have only made the wall higher, and have been less and less effective in getting the economy moving. Capitalism is thus on the edge of a precipice: in 2011, the financing of debt, ie. the money needed to pay debts that had reached their deadline, and the interest on the overall debt, reached $10,000bn. In 2012, it is predicted to reach $10,500bn, while the world’s reserves are estimated at $5,000bn. Where is capitalism going to find the money to pay for this?

At the end of 2011 we saw not only the debt crisis of the banks and assurances, but also the growing implication of the sovereign debts of states. It is legitimate to ask who is going to go down first? A big private bank and thus the whole world banking system? A new state like Italy or France? The eurozone? The dollar?

From economic crisis to political crisis

In the previous International Review we pointed to the very wide disagreements between the main countries of the eurozone in facing the financial problem of the cessation of payment by certain countries, whether this was already happening (as in the case of Greece) or threatening to happen (as in the case of Italy), and the differences between Europe and the USA in dealing with the problem of world debt.1

Since 2008, all policies have led to a dead-end, while disagreements within the different national bourgeoisies about the debt and the problem of growth have led to tensions, disputes and open confrontations. With the inevitable development of the crisis, this “debate” is only just beginning.

There are those who want to reduce the debt through violent austerity budgets. For them, there is one slogan: drastic cuts in all state expenditure. Here Greece is a model showing the way for everyone. The real economy there has been through a 5% recession. Businesses are closing; the country and the population are sinking into ruin and poverty. And still this disastrous policy is being taken up all over the place: Portugal, Spain, Italy, Ireland, Britain, etc. The bourgeoisie has the same illusion as the doctors of the Middle Ages who believed in the virtues of a good bleeding. But the economy will do no better from such a remedy than their patients did.

Another part of the bourgeoisie wants to monetise the debt, ie. transform it into issues of money. This is what the American and Japanese bourgeoisies have been doing on an unprecedented scale, for example. It’s what the ECB has been doing on a smaller scale. This policy has the merit of making it possible to play for time. It makes it possible to deal with debt deadlines on a short-term basis. It makes it possible to slow down the recession. But it has a catastrophic side effect: eventually it will result in a general fall in the value of money. Capitalism can no more live without money than a man can live without breathing. Adding debt to a debt, which is already, as in the US, Britain or Japan, preventing a real revival of the economy can only lead, in the end, to a more profound collapse.

Finally, there are those who think you can combine the two previous approaches. They are for austerity and growth based on the creation of money. This orientation is probably the clearest expression of the impasse facing the bourgeoisie. And yet it’s what they’ve been doing for the last two years in Britain and what Monti, the new chief of the Italian government, is calling for there. This part of the ruling class reasons as follows: “if we make an effort to drastically reduce expenditure, the markets will regain confidence in the capacity of states to repay their debts. They will then lend to us as tolerable rates and we can again go into debt”. The circle is complete. This part of the bourgeoisie really thinks it can go back in time, to the situation before 2007-8.

None of these alternatives are viable, even in the medium term. They all lead capital into an impasse. While the creation of money by the central banks seems to lead to a bit of respite, the journey will still end up at the same destination: the historic downfall of capitalism.

Governments are more and more unstable

Capitalism’s economic dead-end inevitably engenders a historic tendency towards political crisis within the bourgeoisie. Last spring, in the space of a few months, we saw spectacular political crises in Portugal, the USA, Greece and Italy. In a more discreet manner, the same crisis is advancing in other central countries like Germany, Britain and France.

For all its illusions, a growing part of the world bourgeoisie is beginning to grasp the catastrophic state of its economy. We are hearing increasingly alarmist statements. As this anxiety, disquiet and even panic spreads amongst the bourgeoisie, they are beginning to go back to some of the old, rigid certainties. Each part of the bourgeoisie is fixating on the best way to defend the national interest, according to the economic or political sector it belongs to. The ruling class is coming to blows over the various hopeless solutions we looked at above. Each political orientation proposed by the government team provokes violent opposition from other sectors of the bourgeoisie.

In Italy, the total loss of credibility in Berlusconi’s ability to impose the austerity plans that are supposed to reduce public debt led the former president of the Italian Council to quit, following pressure from the “markets” and the main representatives of the eurozone. In Portugal, Spain and Greece, over and above the national specificities, the same reasons led to the hurried departure of the governments in place.

The example of the USA is historically the most significant. This is the world’s leading power. This summer, the American bourgeoisie was torn apart around the question of raising the ceiling on debt. This has been done many times since the 1960s without posing any major problems. So why this time did it provoke such a crisis that the American economy was a hair’s breadth from total paralysis? It’s true that a faction of the bourgeoisie which has acquired a growing weight in the political life of the US ruling class, the Tea Party, is totally irresponsible even from the standpoint of defending the interests of the national capital. However, contrary to those who would like us to believe it, it’s not the Tea Party which is the main cause of the paralysis of the American central administration but the open confrontation between the Democrats and the Republicans in the Senate and the House of Representatives, with each one thinking that the solution put forward by the other is catastrophic, suicidal for the country. This led to a dubious, fragile compromise, which will probably, only last a short time. It will be put to the test during the forthcoming elections. The continuation of the economic weakening of the USA can only fuel the political crisis there.

But the growing impasse of the present policies can also be seen in the contradictory demands that the financial markets are making on governments. These famous markets are demanding at one and the same time draconian plans of “rigour” and at the same time a revival of economic activity. When they start losing confidence in the ability of a state to repay significant parts of its debt, they quickly raise the interest rates on their loans. The end result is guaranteed: these states can no longer borrow on the markets. They become totally dependent on the central banks. After Greece, the same thing is beginning to happen for Spain and Italy. The economic noose is tightening on these countries, adding more fuel to the political crisis.

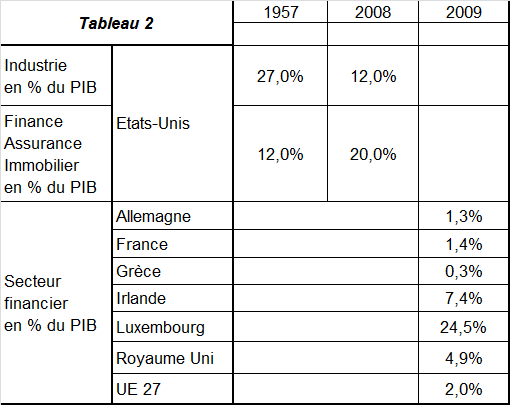

The attitude of Cameron at the last EU summit, rejecting the same budgetary and financial discipline for everyone, spells the eventual end of the line for the Union. The British economy only survives thanks to its financial sector. Even thinking about controls over this sector is out of the question for the majority of British Conservatives. Cameron’s position has led to conflicts between the Tories and the Liberal Democrats, making the governing coalition weaker than before. It has also sharpened dissensions in Wales and Scotland over the issue of belonging to the EU.

Finally, a new factor favouring the development of the political crisis of the bourgeoisie has raised its head in recent debates. An old demon, held in check for a long time, is now straining at the leash: protectionism. In the USA and the eurozone, many conservatives and populists of right and left are calling for new customs barriers. For this part of the bourgeoisie, which is now being joined by a number of “socialists”, the way forward is to reindustrialise your country, to “produce nationally”. China is already protesting against the measures that the USA has taken towards its imports. In Washington itself there is still much tension over this question. The Tea Party but also a significant part of the Republican party are pushing these demands to the limit, forcing Obama and the Democrats (as with the question of the debt ceiling) to dub these sectors as locked in the past and as irresponsible. This phenomenon is only just beginning. For the moment, no one can foresee how far it’s going to go. But what’s certain is that it will have an important impact on the coherence of the bourgeoisie as a whole, its ability to maintain stable parties and government teams.

However we look at this crisis within the bourgeoisie, it can only go in one direction, towards the growing instability of governing teams, including those in the leading powers of the planet.

The bourgeoisie divided by the crisis but united against the class struggle

The proletariat cannot celebrate the political crisis of the bourgeoisie in itself. Divisions and conflicts within the ruling class are no guarantee of success for its struggle. All proletarians and above all the young generations of the exploited need to understand that, however deep the crisis within the bourgeoisie, however acute its internal faction fights, it will always unite against the class struggle. This is known as the Sacred Union. This was the case during the Paris Commune of 1871. Let’s remember how the Prussian and French bourgeoisies managed to unite in time to crush the first great proletarian uprising in history. All the big movements of the proletarian struggle have come up against this Sacred Union. There is no exception to the rule.

The proletariat cannot count on the weaknesses of the bourgeoisie. Political divisions within the enemy class don’t guarantee its victory. It can only count on its own forces. And we have been seeing these forces emerging in a number of countries recently.

In China, a country where an important part of the world working class is now concentrated, struggles are taking place almost daily. There are explosions of anger involving not only the wage workers but the more general impoverished population, such as the peasantry. Miserable wages, unbearable working conditions, ferocious repression... Social conflicts have been developing, notably in the factories where production is being hit by the slow-down in European and American demand. Here in a shoe factory, there in a factory in Sichuan, there at HIP, a subsidiary of apple, at Honda, Tesco etc. “There is a strike almost every day, said labour rights activist Liu Kalming.”2 Even if these struggles remain, for the moment, isolated and without much perspective, they show that the workers in Asia, like their class brothers and sisters in the West, are not ready to just knuckle down and accept the consequences of the economic crisis of capital. In Egypt, after the big mobilisations of January and February 2011, the feeling of revolt is still very much alive in the population. Generalised corruption, total impoverishment, the political and economic impasse, have pushed thousands of people onto the streets and the town squares. The government, currently led by the military, responds with slander and bullets, a repression made all the easier by the fact that, unlike last year, the working class has not been able to mobilise itself en masse. For the bourgeoisie this is where the danger lies: “you can understand the army’s anxiety about the insecurity and social turbulence that has developed in the last few months. There is a fear of the contagion of strikes in the enterprises where the employees are deprived of any social and union rights while any protest is seen as a form of treason” (Ibrahim al Sahari, a representative of the Centre of Socialist Studies in Cairo3).

Here it’s said clearly: what the bourgeoisie fears is a workers’ movement developing on its own class terrain. In this country, democratic illusions are strong after so many years of dictatorship, but the economic crisis can limit their impact. The Egyptian bourgeoisie, whatever faction is in government after the recent elections, cannot prevent the situation from worsening and the unpopularity of the government from growing. All these workers’ struggles and social movements, despite their limitations and weaknesses, express the beginnings of a refusal, by the working class and a growing part of the oppressed population, to passively accept the fate reserved for them by capitalism.

The workers in the central countries of capitalism have also not been inert in the last few months. On 30th November in Britain, two million people came onto the streets to protest against the permanent deterioration of their living conditions. This strike was the biggest for several decades in a country where the working class, which in the 1970s was the most militant in Europe, was crushed under the heel of Thatcherism in the 1980s. This is why seeing two million people demonstrating on the streets in Britain, even though it was a sterile, union controlled “day of action”, is a very significant sign of the revival of working class militancy on a world scale. The movement of the “Indignados”, especially in Spain, has shown in an embryonic way what the working class is capable of. The premises of its own strength appeared very clearly: general assemblies open to everyone, free and fraternal debates, the attempt to take charge of the struggle by the movement itself, solidarity and self-confidence (see the numerous articles about these movements that we have published on our website4). The ability of the working class to organise itself as an autonomous force, as a unified collective body, will be a vital element in the development of massive proletarian struggles in the future. The workers of the central countries, who are best placed to unmask the democratic and trade union mystifications which they have faced for decades, will also show the proletariat of the world that this is possible and necessary.

World capitalism is in the process of collapsing economically, and the bourgeois class is being more and more shaken by political crises. Every day, it becomes a little clearer that this system is totally unviable.

Counting on our forces also means knowing what we lack. Everywhere a movement of resistance against the attacks of capitalism is being born. In Spain, in Greece, in the USA, the criticisms coming from the proletarian wing of this movement are directed against this rotten economic system. We are seeing the beginnings of a rejection of capitalism. But then the key question is posed to the working class. We can see the necessity to destroy this system, but what are we gong to put in its place? What we need is a society without exploitation, without poverty and war. A society where humanity is at last united on a world scale and no longer divided into nations or classes, no longer separated by colour or religion. A society where everyone will have what they need to fully realise themselves. This other world, which has to be the goal of the class struggle when it launches its assault on capitalism, is possible. It is the task of the working class (those at work, the unemployed, future proletarians still in education, those who work behind a machine or at a computer, manual labourers, technicians, scientists etc) to undertake this revolutionary transformation and it has a name: communism, which obviously has nothing in common with the hideous monstrosity of Stalinism which has usurped the name! This is not a dream or a utopia. Capitalism, in order to develop itself, has also developed the technical, scientific and productive means which will make a world human society possible. For the first time in its history, society can leave behind the realm of scarcity and reach the realm of abundance and of respect for life. The struggles which are developing now all over the world, even if they are still very embryonic, have begun to re-appropriate this goal under the lash of a failing social order. The working class carries within itself the historic capacity to reach this goal.

Tino 10.1.12

2. In the journal Cette Semaine.

3. World Revolution 350 [3]

4. See for example: ICC Online, September 2011 [4] ; International Review 147 [5]

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [6]

Rubric:

Debate: The state in the period of transition from capitalism to communism, Part 1

- 2953 reads

We publish below a contribution from a political group in the proletarian camp, OPOP,1 about the state in the transition period and its relationship with the organisation of the working class during this period.

Although this question is not of "immediate topicality", it is a fundamental responsibility of revolutionary organisations to develop theory that will enable the proletariat to carry out its revolution. In this sense, we welcome the effort of the OPOP to clarify an issue that will be of primary importance in the future revolution, if it is successful, in order to implement the global transformation of the society bequeathed by capitalism into a classless society without exploitation.

The experience of the working class has already contributed to the practical clarification and theoretical elaboration of this issue. The brief experience of the Paris Commune, where the proletariat took power for two months, has clarified the need to destroy the bourgeois state (and not to conquer it as revolutionaries previously thought) and for the permanent revocability of delegates elected by the workers. The Russian Revolution of 1905 gave rise to specific organs, the workers' councils, organs of working class power. After the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Lenin in his book The State and Revolution condensed the gains of the proletarian movement on this issue at that time. It is the conception summarised by Lenin of a proletarian state, the Council-State, that is addressed in the OPOP’s text below.

For OPOP, the failure of the Russian Revolution (because of its international isolation) does not permit us to draw new lessons with regard to Lenin’s point of view. On this basis, it rejects the ICC’s conception that challenges the notion of the "proletarian state". While developing its critique, OPOP’s contribution takes care to define the scope of disagreement between our organisations, which we welcome, pointing out that we have in common the idea that "workers' councils must have unlimited power and [...] must constitute the core of the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat".

The view of the ICC on the question of the state only continues the theoretical effort led by the left fractions (Italian in particular) that arose in response to the degeneration of the parties of the Communist International. While it is perfectly fair to find the root cause of the degeneration of the Russian revolution in its international isolation, this does not mean that this experience cannot provide lessons about the role of the state, thus enriching the theoretical basis that is Lenin’s State and Revolution. Unlike the Paris Commune, which was clearly and openly crushed by the savage repression of the bourgeoisie, in Russia it was somehow from "inside", from the degeneration of the state itself, that the counter-revolution came (in the absence of the extension of the revolution). How to understand this phenomenon? How and why could the counter-revolution take this form? It is precisely by basing ourselves on the theoretical gains made on the basis of this experience that we criticise the position of the "proletarian state" advocated in Lenin’s work, as well as some formulations of Marx and Engels made in the same sense.

Of course, unlike the “positive” gains of the Commune, the lessons we learn about the role of the state are "negative", and in this sense they are an object of open questioning, not having been decided by history. But as we said above, it is the responsibility of revolutionaries to prepare for the future. In a future issue of the International Review we will publish a response to the theses developed by OPOP. We can mention here, in a very summarised way, the main ideas on which this will focus:2:

-

it is inappropriate to speak of the state as being the product of a particular class. As Engels showed, the state is the product of the entire society divided into antagonistic classes. Identifying with the dominant production relations (and therefore with the class that embodies them), its function is to preserve the established economic order;

-

after the victorious revolution, different social classes still exist, even after the defeat of the bourgeoisie at the international level;

-

if the proletarian revolution is the act by which the working class constitutes itself as the politically dominant class, this class does not become the economically dominant class. It remains, until the integration of all members of society into associated labour, the exploited class of society and the only revolutionary class, that is to say bearing the communist project. As such, it must permanently maintain its class autonomy to defend its immediate interests as the exploited class and its historic project of communist society.

ICC

Workers' councils, proletarian state, dictatorship of the proletariat in the socialist phase of transition to a classless society

1. Introduction

The lefts are behind in the very urgent discussion on questions of strategy, tactics, organisation and also on the transition [to communism]. Among the many subjects that need answers, one that stands out particularly is that of the state, which deserves a systematic debate.

On this question, some left forces have a different view from ours, mainly regarding the councils, the real structures of the working class, which arise as organs of a pre-Commune-State, and by extension, of the Commune-State itself. For these organisations, the state is one thing and the councils another, totally different. For us, the councils are the form through which the working class constitutes itself at the organisational level in the state, as the dictatorship of the proletariat, seeing that the state means the power of one class over another.

The marxist conception of the proletarian state contains, for the short term, the idea of the need for an instrument of class rule, but for the medium term it indicates the need for the end of the state itself. What it proposes and what must prevail in communism is a classless society and the absence of the need for the oppression of man or woman, since there has never been more antagonism between different social groups than there is today because of private ownership of the means of production and the separation of direct producers from the means – and the conditions – of work and thus of production.

Society, which will then be highly developed, will enter a stage of self-government and the administration of things, where there will be no need for the transitory social organisations experienced since homo sapiens has existed, with the exception of the council form which is the most evolved form of the state (its simplified character, its dynamic of deliberate and conscious self-extinction and its social force are nothing but manifestations of its superiority over all other past forms of the state). The working class will use this form to pass from the first phase of communism (socialism) to a higher phase of society, a classless society. But to reach this stage, the working class must build, well in advance, the means of the transition, which are the councils on a global scale.

The task will then fall to marxist organisations, not to control the state, either from the outside or the inside, but to constantly struggle within the Commune-State built by the working class and all of the proletariat through the councils, so that it rises to the most revolutionary heights of its combat. The councils, in turn, will actually assume the struggle for the new state, with the understanding that it is they themselves who are the state, which was not without reason called by Lenin the Commune-State.

The Council-State is revolutionary as much in form as in content. It differs, in essence, from the bourgeois state of capitalist society as much as the other societies which precede it. The Council-State results from the constitution of the working class as the ruling class, as posed in the Communist Manifesto of 1848 written by Marx and Engels. In this sense, the functions it takes on differ radically from those of the bourgeois capitalist state, to the extent that a change takes place, a quantitative and qualitative transformation at the same moment as the rupture between the old power and the new form of social organisation: the Council-State.

The Council-State is at the same time and dialectically the political and social negation of the earlier order; this is why it is, equally dialectically, the affirmation and negation of the form of the state: negation in that it undertakes its own extinction and at the same time of all forms of the state; affirmation as an extreme expression of its own strength, the condition of its own negation, in that a weak post-revolutionary state would be unable to resolve its own ambiguous existence: to carry out the task of repression of the bourgeoisie as the first premise of its decisive step, the act of its disappearance. In the bourgeois state, the relation of dictatorship-democracy is achieved through a combined relationship of (dialectical) contradictory unity in which the great majority is subdued through the political and military domination of the bourgeoisie. In the Council-State, on the contrary, these poles are reversed. The proletariat, which previously had no political participation because of the process of manipulation and exclusion from decisions through which it was subdued, will play the dominant role in the process of class struggle. It will establish the greatest political democracy known to history, which will be associated, as it should, with the dictatorship of the exploited majority over a stripped and expropriated minority, who will do anything to organise the counter-revolution.

It is the Council-State, the ultimate expression of the proletarian dictatorship, that uses this power not only to ensure greater democracy for workers in general and the working class in particular, but before and above all, to suppress in an extremely organised manner the forces of the counter-revolution.

The Council-State condenses in itself, as has already been said, the unity between content and form. It is during the revolutionary situation, when the Bolsheviks organised the insurrection in Russia in October 1917, that this issue became clearer. At that time, it was impossible to distinguish between the project proposed by the working class, socialism, the content and form of organisation, and the new type of state it wanted to build on the basis of the soviets. Socialism, the power of the workers and the soviets; it was all the same, so that we could not talk about one without understanding that they were talking automatically about the other. Thus, it is not because in Russia a state organisation was built that moved further and further away from the working class that we must abandon the revolutionary attempt to establish the Soviet State.

The soviets (councils), through all the mechanisms and elements inherited from the bureaucracy in the USSR, were deprived of their revolutionary content to become, in the mould of a bourgeois state, an institutionalised body. But that does not mean we should give up the attempt to build a new type of state, functioning along basic principles which would necessarily be in line with the most important thing the working class has created through the historical process of its struggle, namely a form of organisation that needs only to be improved in certain aspects in order to complete the transition, but which, basically since the Paris Commune of 1871, has been through a number of rehearsals, a series of trials and errors, which will enable us to achieve the Council-State.

Today, the task of establishing the councils as a form of organisation of the state is situated not only in the perspective of a single country but at the international level, and that is the main challenge facing the working class. Therefore, we propose through this short essay, to make an attempt to understand what the Council-State is, or in other words, to make a theoretical elaboration on a question that the working class has already experienced practically, through its historical experience and in its confrontation with the forces of capital. Let’s turn to the analysis.

2. Preamble

To avoid duplication and redundancy, we consider it to be established that, in this text, we accept the letter of all the principal theoretical and political definitions that define the body of doctrine of Lenin’s State and Revolution. Further, we warn the reader that we will only recall the Leninist premises to the extent they are indispensable to theoretically establish some of the assumptions necessary for the really urgent need to update this subject. In addition, we will only do that if the premises in question are needed to clarify and establish the theoretical-political objective that concerns us, namely the relationship between the council system and the proletarian state (= dictatorship of the proletariat) with its prior form, the pre-state.

From another point of view, Lenin's above mentioned work proves equally necessary and indispensable, as it includes the most comprehensive overview of the passages by Marx and Engels relating to the state in the phase of transition, thereby putting within easy reach a more than sufficient quantity of existing and authorised positions produced on The State and Revolution in the whole political literature.

3. Some premises of workers' power

Commenting on Engels, in two passages of his text Lenin makes the following statements: “The state is the product of the irreconcilability of class antagonisms [...] According to Marx, the state could neither have arisen nor maintained itself had it been possible to reconcile classes” and “...the state is an organ of class rule, an organ for the oppression of one class by another”.3 Conciliation and domination are two very precise concepts in Marx, Engels and Lenin’s doctrine of the state. Conciliation means the negation of any contradiction whatsoever between the terms of a given relationship. In the social sphere, in the absence of contradictions in the ontological constitution of the fundamental social classes of a social formation, to speak of the state does not make sense. It is historically proven that in primitive societies there is no state, simply because there are no social classes, exploitation, oppression or domination by one class over another. On the other hand, when it comes to the ontological constitution of social classes, domination is a concept that excludes hegemony, as hegemony supposes the sharing – very unevenly – of positions within the same structural context. The result is that in the field of bourgeois sociality, which extends to that of the revolution, in which the bourgeoisie and the proletariat are situated and are fighting from diametrically antagonistic positions, to speak about hegemony of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat does not make sense, whereas one can talk of hegemony between the fractions of the bourgeoisie who share the same state power, and it also makes sense to speak of the hegemony of the proletariat over the classes with which it shares the common goal of taking power by overthrowing the common strategic enemy.4

Moreover, quoting Engels, Lenin speaks of public force, this characteristic pillar of the bourgeois state – the other being the bureaucracy – consisting of an entire specialised military and repressive apparatus, which is separated from society and above it, “...which no longer directly coincides with the population organising itself as an armed force.”5 The identification of this core component of the bourgeois order here has a clear objective: to show how, in return, it is equally essential to establish an armed force, even stronger and more coherent, by which the armed proletariat can suppress, with an even more resolute determination, the beaten but not dead class enemy, the bourgeoisie. In which body of the proletarian dictatorship must this repressive force be found?. This is a question to be addressed in a specific chapter of this text.

The other pillar on which bourgeois power rests is the bureaucracy, comprising state functionaries, who enjoy a pile of privileges, including honorary payments, positions assigned for an easy life, who accumulate all the benefits of practices inherent in a major and recurring corruption. As with the popular militias which are all the stronger to the extent that they are structurally simplified, so it is for the executive, legislative and judicial tasks, which are all the more efficient when they are also simplified, and for exactly the same reason. The executive tasks of the courts and legislative functions are strengthened to the extent that they are taken in hand directly by the workers in conditions where revocability is established in order to curb, from the start, the tendency for the resurgence of castes that has badly affected all societies born from "socialist" revolutions throughout the twentieth century.

The bureaucracy and professional law enforcement, the two main planks on which the political power of the bourgeoisie is based, the two pillars whose functions must be replaced by the workers with structures which are simplified (in the course of their extinction) but also much stronger and more efficient; simplification and strength thus oppose and attract each other in the movement that accompanies the whole transition process until there is no trace of the previous class society. The problem we are now posed is: what is the body which, for Marx, Engels and Lenin, must assume the dictatorship of the proletariat?

4. The dictatorship of the proletariat for Marx, Engels and Lenin

Our trio leaves no doubt about it:

“The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the state, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible."6

Or again, the proletarian state (sic) = "the proletariat organised as the ruling class." "The state, i.e. of the proletariat organised as the ruling class." (sic). So far, the sense of the reasoning of Lenin, Marx and Engels is: the proletariat overthrows the bourgeoisie by the revolution; by overthrowing the bourgeois state machine, it will destroy the state machine in question to immediately erect its own state, simplified and heading for extinction, which is stronger because it is run by the revolutionary class and assumes two types of tasks: to suppress the bourgeoisie and to construct socialism (the phase of transition to communism).

But where does Marx get this belief that the dictatorship of the proletariat is the proletarian state? From the Paris Commune ... simple! Indeed, “The Commune was formed of the municipal councillors, chosen by universal suffrage in the various wards of the town, responsible and revocable at any time. The majority of its members were naturally working men, or acknowledged representatives of the working class".7 The question goes much further: members of the proletarian state (sic), the Commune-State, are elected in district councils, which does not mean that there are no councils of workers which put themselves at the head of such councils, as in Russia, in the soviets. The question of the hegemony of the workers’ leadership is guaranteed by the existence of a majority of workers in these councils and, of course, by the leadership which the party must exercise in such instances.

Only one ingredient is missing to articulate the position of proletarian state, Council-State, Commune-State, socialist state or dictatorship of the proletariat: the method of decision-making, and here it is here that we must refer to the universal principle that many marxists fail to understand: democratic centralism, “But Engels did not at all mean democratic centralism in the bureaucratic sense in which the term is used by bourgeois and petty-bourgeois ideologists, the anarchists among the latter. His idea of centralism did not in the least preclude such broad local self-government as would combine the voluntary defence of the unity of the state by the ‘communes’ and districts, and the complete elimination of all bureaucratic practices and all ‘ordering’ from above.”8. It is clear that the term and concept of democratic centralism is not the creation of Stalinism, as some like to argue, thus distorting this essentially proletarian method – but of Engels himself. Therefore, it cannot be given the pejorative connotation that comes from the bureaucratic centralism used by the new state bourgeoisie in the USSR.

5. Council system and dictatorship of the proletariat

The antithetical separation between the council system and post-revolutionary state is an error for several reasons. One of them is that it is a position which distances itself from the conception of Marx, Engels and Lenin in reflecting a certain influence of the anarchist conception of the state. To separate the proletarian state from the council system comes back to breaking the unity that should exist and persist in the dictatorship of the proletariat. Such a separation defines, on one side, the state as a complex administrative structure, to be managed by a body of officials – an aberration in the simplified conception of the state of Marx, Engels and Lenin – and on the another, a political structure, in the framework of the councils, to put pressure on the first (the state as such). This conception results in an accommodation to a vision influenced by anarchism that identifies the Commune-State with the (bourgeois) bureaucratic state. It is the product of the ambiguities of the Russian Revolution and places the proletariat outside of the post-revolutionary state, creating a dichotomy, which itself is the germ of a new caste breeding in an administrative body organically separate from the councils.

Another cause of this error, which is related to the preceding one, is in the establishing of a strange connection that identifies in an uncritical way the state that emerged in the post-revolutionary Soviet Union – a necessarily bureaucratic state – with the conception of the State-Commune of Marx, Engels and Lenin himself. It is an error that arises from a misunderstanding of the ambiguities that resulted from the specific historical and social circumstances that blocked not only the transition but also the beginning of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the USSR. Here, one ceases to understand that the dynamic taken by the Russian Revolution– unless you opt for the easy but very inconsistent interpretation in which deviations in the revolutionary process were the result of the policies of Stalin and his entourage – did not obey the conception of the revolution, the state and of socialism that Lenin had, but resulted from the restrictions of the social and political terrain from which the power of the USSR emerged, characterised among others, to recall, by the impossibility of the revolution in Europe, by civil war and the counter-revolution within the USSR. The resulting dynamic was foreign to the will of Lenin. He himself thought about this problem, but repeatedly came up with the ambiguous formulations present in his later thinking and just before his death. Such ambiguities were situated more in the advances and setbacks of the revolution than in the basic political theoretical conceptions of Lenin and the Bolshevik leaders who continued to agree with him.

A third cause of this error is to not take into account that the organisational and administrative tasks put on the agenda by the revolution are essentially political tasks, whose implementation must be carried out directly by the victorious proletariat. Thus, burning issues such as central planning – given a bureaucratic form in Gosplan (Central Planning Commission) has long been confused with "socialist centralisation" – are not purely "technical" questions but highly political and, as such, cannot be delegated, even if they are "checked" from the outside, by the councils, by means of a body of employees located outside the council system, where the most conscious workers are found. Today, we know that ultra-centralised "socialist" planning was only one aspect of the bureaucratic centralisation of "Soviet" state capitalism which kept the proletariat remote and outside of the whole system of defining objectives, decisions about what should be produced and how it should be distributed, the allocation of resources, etc.. Had it been a real socialist planning, all of this should have been the subject of wide discussion in the councils, or the Commune-State. Seeing that the proletarian state merges with the council system, the socialist state is “a very simple ‘machine’, almost without a ‘machine’, without a special apparatus, by the simple organisation of the armed people (such as the Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, we would remark, running ahead).”"9

Another misunderstanding is in the non-perception that the real simplification of the Commune-State, as described by Lenin in the words reported earlier, implies a minimum of administrative structure and that this structure is so small and in the process of simplification/extinction, that it can be assumed directly by the council system. Therefore, it makes no sense to take as a reference the "soviet" state of the USSR to put in question the socialist state that Marx and Engels saw born in the Paris Commune. In fact, to establish a link between the Council-State and the bureaucratic state that emerged from the Russian Revolution, amounts to giving the proletarian state a bureaucratic structure that a true post-revolutionary state, simplified and in the process of simplification / extinction, not only does not possess but specifically rejects.

In fact, the nature and extent of the Council-State (proletarian state = socialist state = dictatorship of the proletariat= Commune-State = transition state) are beautifully summarised in this passage written by Lenin himself: “the ‘state’ is still necessary, but this is now a transitional state. It is no longer a state in the proper sense of the word.”10 But, you say, if that were the true conception of the socialist state of Lenin, why was it not "applied" in the USSR after the October Revolution, seeing that what appeared then was the exact opposite of all that, from the distortions of the extreme bureaucratic centralisation (from the army to the state bureaucracy to the production units) to the most brutal repression of the Kronstadt sailors? Well, it only reveals that revolutionaries of the stature of Lenin can potentially be overcome by contradictions and ambiguities of this magnitude – and this was in the specific national and international context of the October Revolution – that can lead, in practice, to actions and decisions often diametrically opposed to their deepest convictions. In the case of Lenin and the Bolshevik Party, one of the impossibilities [of the revolution. Ed. Note] - and they were many - was sufficient to steer the revolution in an undesired direction. One of these impossibilities was more than sufficient: the situation of isolation of a revolution that could not retreat, but found itself isolated and had no choice but to try to pave the way for building socialism in one country, in Soviet Russia – a contradictory attempt which was initiated already at the time of Lenin and Trotsky. What were War Communism, NEP, and other initiatives, if not this?

And then what do we do? Do we stand firm on the conceptions of Lenin, Marx and Engels on the state, programme, revolution and the party so that, in the future, when practical problems such as the internationalisation of the class struggle, among others, show the real possibilities for the revolution and building socialism in several countries – do we put them forward and give substance to the ideas of Marx, Engels and Lenin? Or, conversely, should we, faced with the first difficulties, give up the positions of principle, trading them for cheap political imitations that can only lead to the abandonment of the perspective of the revolution and socialist construction?

6. For a conclusion: council, (socialist) state and (socialist) pre-state

a) The Council-State

After analysing the economic premises of the abolition of social classes, that is to say, the premise “that ‘all’ can take part in the administration of the state,” Lenin, always referring to the formulations of Marx and Engels, said that “it is quite possible, after the overthrow of the capitalists and the bureaucrats, to proceed immediately, overnight, to replace them in the control over production and distribution, in the work of keeping account of labour and products, by the armed workers, by the whole of the armed population.” “Accounting and control-that is mainly what is needed for the ‘smooth working’, for the proper functioning, of the first phase of communist society. All citizens are transformed into hired employees of the state, which consists of the armed workers. All citizens become employees and workers of a single countrywide state ‘syndicate’.”11. In addition, “Under socialism all will govern in turn and will soon become accustomed to no one governing. The ‘socialist stage’ “will create such conditions for the majority of the population as will enable everybody, without exception, to perform ‘state functions’.”12

All citizens, remember, organised in the council system, or in other words, in the workers’ state, seeing that for Marx, Engels and Lenin, simplifying tasks will reach a point where the basic "administrative" tasks, reduced to the extreme, not only can be taken over by the proletariat and people in general, but can be taken in charge by the council system, which, after all, is the state itself.

Thus, the proletarian state, the socialist state, the dictatorship of the proletariat is nothing other than the council system, which will ensure the hegemony of the working class as a whole, will take over directly, without the need for any specific administrative body, both the defence of socialism and the management functions of the state and units of production. Finally, this unity of the proletarian dictatorship will be guaranteed by the simplified administrative/ political unit, in a single whole called the Council-State.

b) The pre-Council-State

The council system which, in the post insurrectionary situation, will be responsible for the structural transition (establishment of new relations of production, elimination of all hierarchy in production, rejection of all mercantile forms, etc.) and in the superstructure (elimination of all hierarchy inherited from the bourgeois state, of all bureaucracy, rejection of all ideology inherited from the previous social formation, etc.), is the same council system as the one that, before the revolution, was the revolutionary organisation that overthrew the bourgeoisie and its state. So this is the same body whose tasks have changed over the two stages of the same process of social revolution: having completed the task of the insurrection, it must start to implement a new task that will complete the real social revolution – the break with the social formation that has expired and the inauguration of a new one, socialism, which itself is soon to turn into the communist transition, the second classless society in history (the first was, of course, primitive society).

Well, that's the council system that we call the (proletarian) pre-state. We see that the name is, by its content, nothing original, as it was, is and always will be a proof of the revolutionary process opened up by the Paris Commune. There, the Communards who seized power from the districts were the same as those who had assumed state power – the dictatorship of the proletariat – and who had begun, although with obvious errors of youth, the construction of a socialist order. A similar process occurred again in October 1917. The first experiment could not, in the circumstances where it occurred, reach its completion and was struck by the counter-revolutionary force of the bourgeoisie, after barely two months of memorable life. The second, as we know, could not reach completion due to the lack of conditions, external and internal, including the impossibility of completing the construction of socialism in one country.

In both cases, there was a pre-state, but in both cases, a pre-state which, if on the one hand it could conduct the insurrection, on the other it could not be prepared in time for the task of building socialism. In the case of 1917, it was not until the eve of October that the only party (the Bolshevik party) equipped with the theoretical prerequisites to prepare the vanguard of the class organised in soviets, especially in St. Petersburg, could teach the class only the most urgent tasks of the insurrection. For us it seems that, despite the consciousness, especially by Lenin, of the fundamental importance of the soviets since 1905, it was only after February 1917, in the case of Lenin, that this consciousness became conviction. That is why the party of Lenin (whose return to Russia was easily predictable, as he had previously returned in 1905) did not worry about fully mobilising the militancy of its worker activists in the soviets (the Mensheviks had arrived earlier), or including them in the prior preparations of the workers for a resurgence of the soviets, sooner and by more effective training. Such training, including the most determined vanguard of the class organised in the soviets, was to include, under the fire of an incessant debate between these workers, the questions of the insurrectional seizure of power and notions of marxist theory concerning the establishment of their state and the construction of socialism. This debate was flawed, by the inability to perceive earlier the importance of the soviets, and by lack of time to take the debate among the workers of the soviets only two months before the insurrection. Nevertheless, the unpreparedness of the vanguard to seize power and to exercise it, through its intervention and its leading role, for the construction of socialism, was one of the unfavourable factors for a real dictatorship of the proletariat (on the basis represented by the councils) in the USSR. Such a gap, caused largely by the lack of a suitable pre-state, that is to say a pre-state that constitutes a school of revolution, was an additional difficulty in the shipwreck of the 1917 Russian Revolution.

As Lenin himself always pointed out, communist revolutionaries are men and women who must have a very solid marxist background. A solid marxist background requires relative knowledge of the dialectic, political economy, historical and dialectical materialism, that allows the militants of a party of cadres, not only to analyse and understand past and present circumstances, but also to capture the essentials of predictable processes, at least in terms of the broad lines (such levels of prediction can be identified in many of the analyses in Lenin's Philosophical Notebooks). Hence the fact that a real marxist training can provide militant cadres of a genuine communist party with the ability to anticipate the possible scenarios for the development of a crisis like the current crisis. Similarly, to anticipate a broad process of revolutionary situations does not constitute a "beast with seven heads."13

In addition, it is perfectly feasible to predict the most obvious thing in this world, the emergence of embryonic forms of councils – because, here and there, they are beginning to emerge in an embryonic way. They must be analysed, in all frankness, without prejudice, so that, once interpreted theoretically, workers can correct the mistakes and shortcomings of such experiences, so that they can multiply and reinforce their content, until they become, in a near future – this guarantee is provided by the advanced stage of the structural crisis of capitalism – in the context of concrete revolutionary situations, the system of councils, from the dialectical interaction of small circles (in the workplace, education and housing), factory committees, and councils (of districts, regions, industrial zones, national, etc.) that will form, at the same time, the backbone of the insurrection and, in the future, the organ of the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.

7. In conclusion: the ICC and the question of the post-revolutionary state

For us, the workers’ councils must have unlimited power, and as such must be the basic organs of workers' power, besides the fact that they must constitute the core of the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat. But it is from here that we differentiate ourselves from some interpreters of marxism who make a separation between the councils and the Commune-State, as if this Commune-State and the councils were two qualitatively distinct things. This is the position, for example, of the ICC (International Communist Current). After making this separation, such interpreters establish a link whereby the councils must exert pressure and their control over the "semi-state of the transition period", without which this state (= Commune) – that in the ICC's vision, "is neither the bearer nor the active agent of communism" – will not fulfil its immanent role as conserver of the status quo (sic) and "obstacle" to the transition.

For the ICC, “The state always tends to grow disproportionately. It is the ideal target of careerists and other parasites and easily recruits the residual elements of the old decomposing ruling class.”14 And it finishes its vision of the socialist state by stating that Lenin at least foresaw (this function of the state) when he “talked about the state as the reconstitution of the old Tsarist apparatus”.and when he says that the state born from the October Revolution tended “to escape our control and go in the opposite direction from the one we want it to go.” For the ICC, “The proletarian state is a myth. Lenin rejected it, recalling that it was “a workers’ and peasants’ government with bureaucratic deformations.”” Moreover, for the ICC:

“The great experience of the Russian Revolution is there to prove it. Every sign of fatigue, failure or error on the part of the proletariat has the immediate consequence of strengthening the state; conversely each victory, each reinforcement of the state weakens the proletariat a little bit more. The state feeds on the weakening of the proletariat and its class dictatorship. Victory for one is defeat for the other.”"15

It also says, in other passages,16 that “The proletariat retains and maintains complete freedom in relation to the state. On no pretext will the proletariat subordinate the decision-making power of its own organs, the workers’ councils, to that of the state; it must see that the opposite is the case”; that the proletariat “won’t tolerate the interference of the state in the life and activity of the organised class; it will deprive the state of any right or possibility of repressing the working class” and that “The proletariat retains its arms outside of any control by the state”. “The precondition for this is that the class does not identify with the state.”

What is the situation with this vision of the ICC comrades on the Commune-State? First, that neither Marx nor Engels nor Lenin, as we have seen in the observations made above and taken from The State and Revolution, defend the conception of the state developed by the ICC. As we have seen, the Commune-State was, for them, the Council-State, the expression of the power of the proletariat and its class dictatorship. For Lenin, the post-revolutionary state was not only not a myth, as the ICC think, but the proletarian state itself. How can this state be so described by the ICC when at the same time it conceives it as a Commune-State?

Second, as we have already analysed above, the paradoxical separation between the councils and post-revolutionary state, posed by the ICC, distances itself from the conception of Marx, Engels and Lenin and reflects a certain influence of the anarchist conception of the state. We need to reiterate what we have said before, that to separate the proletarian state from the council system amounts to breaking the unity that should exist and exists under the dictatorship of the proletariat, and that such a separation places, on the one hand, the state as a complex administrative structure and managed by a body of officials – a nonsense in the simplified design of the state according to Marx, Engels and Lenin – and, on the other, a political structure in which the councils exert pressure on the state as such.

Third, we repeat: this conception, which results from an accommodation to a vision influenced by anarchism that identifies the Commune-State with the bureaucratic (bourgeois) state, comes from the ambiguities of the Russian Revolution, putting the proletariat outside of the post-revolutionary state while actually creating a dichotomy that, itself, is the germ of a new caste reproducing itself in the administrative body separated organically from the workers' councils. The ICC confuses the concept of the state of Lenin with the state produced by the ambiguities of the Revolution of October 1917. When Lenin complained about the atrocities of the state as it developed in the USSR, this does not mean that he rejected his conception of the Commune-State, but the deviations from the Russian Commune-State after October.

Fourth, the comrades of the ICC do not seem to realise, as we also discussed above, the fact that the organisational and administrative tasks that the revolution puts on the agenda from the beginning, are essentially political tasks, whose implementation must be carried out directly by the victorious proletariat.

Fifth, the comrades of the ICC do not seem to realise that, as we also indicated above, the real simplification of the Commune-State, in the sense that Lenin expressed, makes the administrative structure so minimal that it can be managed directly by the council system.

Sixth and final point. Only by assuming directly and from within, simplified tasks under the guidance of the Council-State, of defence and socialist transition/construction, will the working class will be in a condition to prevent a schism occurring between a foreign state and the Council-State, so that it can exercise its control, not only over what happens within the state, but also within society as a whole.

For this, it is worthwhile to recall that the proletarian state, the Commune-State, the socialist state, the dictatorship of the proletariat are nothing other than the council system that has taken charge of the basic organisational tasks of the militias, the length of the working day, work brigades and other equally revolutionary types of tasks (revocability of positions, equal pay, etc.)... tasks, also simplified, concerning the struggle and organisation of a society in transition. For this, it will not be necessary to create an administrative monster, and still less a bureaucratic one, nor any kind of form inherited from the beaten bourgeois state or even something resembling the bureaucratic state capitalism of the ex-USSR.

It would be great if the ICC examines the passages we have highlighted in this text from Lenin’s State and Revolution, where this justifies, on the basis of Marx and Engels, the need for the Commune-State, the Council-State, the proletarian state, the dictatorship of the proletariat.

OPOP

(September 2008, revised December 2010)

1. OPOP, OPosição OPerária (Workers' Opposition), which exists in Brazil. See its publication on revistagerminal.com. For some years the ICC has had a fraternal relationship and cooperated with OPOP, which has already resulted in systematic discussions between our two organisations, jointly signed leaflets and statements ("Brésil : des réactions ouvrières au sabotage syndical [7]"), and joint public interventions ("Deux réunions publiques communes au Brésil, OPOP-CCI: à propos des luttes des futures générations de prolétaires [8]"), and the reciprocal participation of delegations to the congresses of our organisations.

2. These are developed in the following articles: “Draft resolution on the state in the period of transition” in International Review no. 11, and “The state in the period of transition [9]” in International Review no. 15.

3. ICC note. The State and Revolution [10], Chapter I, “The state – a product of the irreconcilability of class antagonisms”.

4. This is an example of the confusions and ambiguities of the accumulation of theoretical and political categories, one next to the other, introduced into marxist doctrine by Antonio Gramsci, carried to their logical and political limits by his epigones, the logical difficulties of which (paradoxes) have been brilliantly investigated by Perry Anderson in his classic, The antinomies of Antonio Gramsci.

5. ICC note. The State and Revolution, Chapter I, “Special bodies of armed men, prisons, etc.”

6. ICC note. Extract from The Civil War in France, cited by Lenin in The State and Revolution, Chapter II, “The eve of the revolution”.

7. ICC note Extract from The Civil War in France, cited by Lenin in The State and Revolution, Chapter III, “What is to replace the smashed state machine?”

8. ICC note. The State and Revolution, Chapter IV, “Criticism of the draft of the Erfurt Programme”.

9. ICC note. The State and Revolution, Chapter V, “The transition from capitalism to communism”.

10. ICC note. The State and Revolution, ibid.

11. ICC note. The State and Revolution, Chapter V, “The higher phase of communist society”.

12. ICC note. The State and Revolution, Chapter VI, “Kautsky’s controversy with Pannekoek”.

13. ICC note: The name of a Brazilian film about psychiatric hospitals in Brazil.

14. ICC note. “The state in the period of transition”, International Review no. 15.

15. ICC note. Ibid.

16. ICC note: the same article.

Deepen:

General and theoretical questions:

- Period of Transition [12]

Rubric:

Critique of the book 'Dynamics, contradictions and crises of capitalism', Part 1

- 2751 reads

Is capitalism a decadent mode of production and why? (I)

At the time of a major acceleration of the world economic crisis we have decided to return to the fundamental questions of the dynamic of capitalist society. Only by understanding them can we fight a system that is condemned to perish either by its own contradictions or by its overthrow and replacement by a new society. These questions have already been looked at in numerous publications of the ICC, so if we judge it necessary to raise them again it is to critique the vision developed in the book Dynamics, contradictions and crises of capitalism.1 This book explicitly defends, with quotations, the analyses of Marx concerning the characterisation of the contradictions and the dynamic of capitalism, notably the fact that the system, like other class societies that have preceded it, necessarily goes through an ascendant phase and a phase of decline. But the manner in which this framework of theoretical analysis is sometimes interpreted and applied to reality opens the door to the idea that reforms would be possible within capitalism which would permit the attenuation of the crisis. In opposition to this approach, the article that follows attempts an argued defence of the insurmountable character of the contradictions of capitalism.

In the first part of this article we examine whether capitalism has ceased to be a progressive system since the First World War, and if it has become, according to Marx's own words, “a barrier for the development of the productive powers of labour”.2 In other words, do the production relations of this system, after having been a formidable factor in the development of the productive forces, constitute, since 1914, a brake on the development of these same productive forces? In a second part we will analyse the origin of capitalism's insurmountable crises of overproduction, and unmask the reformist mystification of a possible attenuation of the crisis by 'social policies'.

Has capitalism been a brake on the growth of the productive forces since the First World War?

The blind forces of capitalism, unleashed by the First World War, destroyed far more productive forces than in all the economic crises of capitalism since its birth. They plunged the world, particularly Europe, into a barbarism threatening to engulf civilisation. This situation would provoke, in reaction, a world revolutionary wave aiming to finish with a system whose contradictions was now a threat to humanity. The position defended at the time by the vanguard of the world proletariat followed the vision of Marx for whom “The growing incompatibility between the productive development of society and its hitherto existing relations of production expresses itself in bitter contradictions, crises, spasms.”3 The Letter of Invitation (end of January 1919) to the Founding Congress of the Communist International declared: “the present period is that of the decomposition and collapse of the whole world capitalist system, it will be the collapse of European civilisation in general, if capitalism, with its insurmountable contradictions, is not defeated.”4 Its Platform underlined that: “A new epoch is born: the epoch of the dissolution of capitalism, of its inner collapse. The epoch of the communist revolution of the proletariat”.5

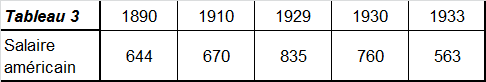

The author of the book, Marcel Roelandts, (MR) accepts this characteristic of the First World War and the international revolutionary wave that followed it, often in the same terms. His analysis partly restates the following elements in relation to the evolution of capitalism since 1914 and which, for us, has confirmed the diagnosis of the decadence of capitalism:

-

the First World War (20 million dead) lowered the production of the European powers involved in the conflict by more than a third, an unprecedented phenomenon in the whole history of capitalism;

-

it was followed by a phase of feeble economic growth leading to the crisis of 1929 and the depression of the 1930s. The latter caused a greater fall in production than that caused by the First World War;

-

the Second World War, even more destructive and barbaric than the first (more than 50 million dead) provoked a disaster to which the crisis of 1929 provides no possible comparison. The alternative posed by revolutionaries at the time of the First World War had been tragically confirmed: socialism or barbarism.

-

since the Second World War there hasn't been a single instant of peace in the world and instead hundreds of wars and tens of millions killed, without counting the resulting humanitarian catastrophes (famines). War, omnipresent in numerous regions of the world, had nevertheless spared Europe, the principle theatre of the two world wars, for a half century. But it made a bloody return there with the conflict in Yugoslavia that began in 1991;

-

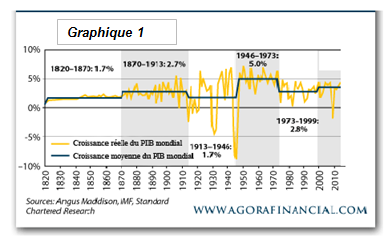

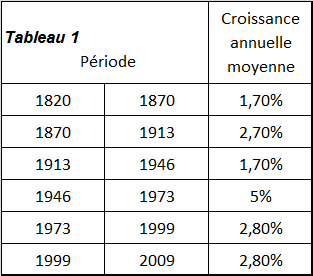

during this period, except for the period of prosperity in the 50s and 60s, capitalism has not been able to avoid recessions that require the injection of more and more massive doses of credit. Growth has only been maintained by the fiction that these debts will be finally repaid;

-

after 2007-2008 the accumulation of colossal debt has become an insurmountable obstacle to the maintenance of even the weakest growth. Not only businesses and banks but also states have been fundamentally weakened or threatened with bankruptcy. A recession without end is now on the historical agenda.

We have limited ourselves here in this summary to the most salient elements of the crises and wars which have made the 20th century the most barbaric that humanity has even known. The dynamic of the economy is not necessarily the direct cause but it cannot be dissociated from the nature of this period.

With what method can we evaluate capitalist production and its growth?

For MR this picture of the life of society since the First World War is not sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of decadence.