International Review no.150 - 4th Quarter 2012

- 2034 reads

June 2012 Euro summit: behind the illusions, another step towards disaster

- 1822 reads

On the morning of 29th June 2012, as if by magic, a gentle euphoria took hold of the politicians and leaders of the Eurozone. The bourgeois media and the economists soon joined them. Apparently, the Euro summit had taken some “historic decisions” - unlike the numerous decisions taken in the last few years, all of which have failed. But according to many commentators, this time it was different. The bourgeoisie of the Eurozone, for once united and solid, had taken the measures needed to get us through the tunnel of the crisis. For a moment you might have thought you had entered Alice’s Wonderland. But, once the morning mists had dissipated, and you looked a bit closer, the real questions came to light: what was the real content of this summit? What was its significance? Would it really bring a lasting solution to the crisis of the Eurozone and thus of the world economy?

The Euro summit: decisions that deceive the eye

If the June 2012 Euro summit was presented as “historic”, it is because it was supposed to be a turning point in the way that the authorities confront the euro crisis. To begin with, at the level of form, this summit, for the first time, did not, as far as the commentators were concerned, restrict itself to rubberstamping the decisions taken in advance by “Merkozy”, i.e. the Merkel-Sarkozy partnership (in reality the position of Merkel rubberstamped by Sarkozy).1 It now took into account the demands of two other important countries of the zone, Spain and Italy, demands supported by the new French president, François Hollande. Secondly, this summit is supposed to inaugurate a new given in economic and budgetary policy inside the zone: after years in which the only policy followed by the leading authorities of the Eurozone was one of increasingly ruthless austerity, now criticisms of this policy are being taken into account. These criticisms, raised above all by the politicians and economists of the left, argue that without reviving economic activity, hyper-indebted states will be unable to find the fiscal resources to pay off their debts.

This is why the “left” president Hollande, who had come to call for a “pact for employment and growth”, took centre stage in the whole show, proud of his demands and the results obtained. In this satisfaction he was accompanied by two men of the right: Monti the Italian head of government and Rajoy, his Spanish equivalent, who also argued that their calculations had paid off and the financial noose around their country’s necks should be loosened. The real situation was much too serious for these men to assume such a triumphant air, but at least they had a sense of humour: “we could hope to see the beginning of the end of leaving the tunnel of the crisis”. These were the convoluted words of the head of the Italian government.

Before lifting the veil from these optimistic declarations, we need to go back in time a bit. Let’s recall: over the last six months, the Eurozone has twice been in a situation where its banks were in a state of collapse. The first time this gave rise to what was called the LTRO (Long Term Refinancing Operation): the European Central Bank (ECB) accorded them loans of around 1000 billion euros. In reality 500 billion had already been supplied to them to keep them afloat. A few months later the same banks were again appealing for help! Let’s now tell a little story which shows us what is really happening in the world of European finance. At the beginning of 2012 sovereign debts (i.e. debts of states) exploded. The financial markets themselves raised the rates at which they were prepared to lend money to these states. Some of them, notably Spain, could no longer afford to look for loans on the market. It was all too expensive. At this point the Spanish banks gave up the ghost. What could be done? What could be done in Italy, Portugal and elsewhere? A brilliant idea began to germinate in the great minds of the ECB. We are going to make massive loans to the banks, who will themselves finance the sovereign debts of their national states and the “real” economy in the form of loans for investment or consumption. This is what happened last winter. The ECB declared “the bar is open and it’s drinks all round”. The result was that at the beginning of June everyone woke up with cirrhosis of the liver. The banks had not been lending out to the “real economy”. They had put the money in safe places, putting its equivalent away in the Central Bank for a small return of interest. What would they give to the Central Bank in exchange? State bonds which they had bought with the money they had got from the same Central Bank. A real conjuring trick which would soon be revealed as an absurd spectacle!

In June the “economic doctors” again cried loud and strong: the patients are slipping towards death. Radical measures were needed immediately for all the hospitals of the Eurozone. We now come to the June summit. After a whole night of negotiations, a “historic” agreement seemed to have been found. The decisions taken were:

the financial stabilisation funds(European Funds for Financial Stability and the European Stability Mechanism) would now be able to flow into the banks, after obtaining the ECB’s agreement, as well as being used to buy up public debts in order to reduce the rates at which states would have to borrow on the financial markets;

the Europeans would confer on the ECB the job of supervising the banking system of the Eurozone;

an extension of the rules for controlling the public deficits of states in the zone;

finally, to the great satisfaction of the economists and politicians of the “left”, a plan of 100 billion euros for reviving economic activity was drawn up.

For several days the same speeches rang out. The Eurozone had finally taken some good decisions. While Germany had succeeded in sticking to its “Golden Rule” in the matter of public expenditure (which demands that states adopt as a fundamental law the necessity to reduce their budget deficits), it at the same time accepted going towards the mutualisation and the monetisation of these debts, i.e. the possibility of reimbursing them by printing money.

As always in this kind of agreement, reality is hidden in the timetable and the way the decisions are put into practice. However, already on this particular morning, there was something very striking. An essential question seems to have been avoided: the financial means and their real sources. There was an unspoken agreement that Germany would end up paying for it all because it’s the only one that seems to have the means to do so. And then during the month of July, surprise surprise, everything was put into question. With the help of some legal manoeuvres, the application of the accords was put off until September at the earliest. There was a little problem. If you add up all of Germany’s commitments in terms of disguised guarantees and lines of credit, the total amount it’s being asked to hand out to its desperate European neighbours amounts to 1500 billion euros. Germany’s GDP is 2650 billion euros and this is without taking into account the contraction in its activity over the last few months. This is a dizzying sum equivalent to half its GDP. The last figures announced for the debt of the Eurozone went up to around 8000 billion, a large part of which is made up of “toxic” debts (i.e. debts where it has been recognised that they will never be repaid). It’s not hard to understand that Germany is incapable of assuring such a level of debt. Neither is it in a position, in the long term, to credibly shore up this wall of debt with its own signature alone on the financial markets. The proof of this can be seen in the paradox confronting an economy in disarray. In the short and middle term Germany is placing its debts at negative rates of interest. The buyers of this debt agree not to notice these ridiculous interests while losing capital through inflation. Germany’s sovereign debt appears to be a mountain refuge capable of withstanding all the storms, but at the same time, the price of insuring this debt is squeezing them at the same level as Greece! In the end this refuge will be shown to be rather vulnerable. The markets know very well that if Germany continues to finance the debt of the Eurozone, it will itself become insolvent and that is why all lenders are trying to get themselves insured as well as they can in case there is a brutal collapse.

There remains the temptation to use the ultimate weapon. That is, to say to the ECB that it should act like in the UK, Japan and the USA: “let’s print more and more bank notes without any regard for their value”. The central banks could indeed become “rotten” banks, that’s not the problem. The problem is to prevent everything coming to a halt. The problem is what happens tomorrow, next month, next year. This is the real advance made at the last European summit. But the ECB wasn’t listening with this ear. It’s true that this central bank doesn’t have the same autonomy as the other central banks of the world. It is linked to the different central banks of each nation in the zone, But is that the basic problem? If the ECB could operate like the central banks of Britain or the US, for example, would this do away with the insolvency of the banks and states of the Eurozone? What was going on at the same time in other countries, for example the USA?

Central banks more fragile than ever

While storm clouds gather over the American economy, why has the USA not yet come up with a third revival plan, a new phase of monetising its debt?

We should recall that the Director of the US central bank, Ben Bernanke, was nicknamed “Mr Helicopter”. In the last four years the USA has already had two plans of massive money creation, the famous “quantitative easing”. Mr Bernanke seemed to be able to fly all over the USA, doling out money wherever he went. A tidal wave of liquidities got everyone drunk. And yet it just didn’t seem to work. For the last few months a new phase of money-printing has become unavoidable. And yet it hasn’t happened. Quantitative Easing 3 is vital, indispensable, and at the same time impossible, as is the mutualisation and monetisation of the overall debt in the Eurozone. Capitalism has come to a dead-end. Even the world’s leading power can’t go on creating money out of nothing. Every debt needs to be paid for at some point or other. Like any other central bank, the US Federal Bank has two sources of finance which are at one moment or another linked and interdependent. The first consists of using up savings, the money which exists inside or outside the country, either through borrowing at tolerable rates, or through an increase in taxation. The second resides in the fabrication of money as a counterpart to the recognition of debts, notably by buying what is known as bonds representing public or state debt. The value of these bonds is in the last instance determined by the evaluation made by the financial markets. A used car is up for sale. Its price is displayed on the window-screen by the seller. Potential buyers verify the state of the vehicle. Offers are made and the seller chooses the least bad one for him. If the vehicle is too decrepit the price becomes derisory and the car is left to rot on the street. This little example shows the danger of a new money-creation in the US and elsewhere. For the last four years, hundreds of billions of dollars have been injected into the American economy without the slightest sign of recovery. Worse: the economic depression has been quietly advancing. Here we are at the heart of the problem. Assessing the real value of sovereign debt is connected to the solidity of the economy. Like the value of our car and its actual state. If a central bank (whether in the US, Japan, or the Eurozone) prints money to buy debts, or the recognition of debts, that can never be repaid (because the borrowers have become insolvent) it does nothing but inundate the market with bits of paper which don’t correspond to any real value because they have no counterpart or guarantees in terms of savings or new wealth. In other words, they are manufacturing fake money.

On the road to generalised recession

Such an assertion might still seem a bit exaggerated. And yet, this is what’s written in the Global Europe Anticipation Bulletin for January 2012: “To generate another dollar’s worth of growth, the USA will now have to borrow around 8 dollars. Or, if you prefer it the other way round: each dollar borrowed only generates 0.12. dollars of growth. This illustrates the absurdity of the medium term policies of the US FED and Treasury in the last few years. It’s like a war where you have to kill more and more soldiers to win less and less ground”. The proportion is no doubt not exactly the same for all the countries of the world. But the general tendency is the same. This is why the 100 billion euros set aside by the 29 June summit to finance growth is nothing but sticking plaster on a wooden leg. The profits obtained are increasingly pitiful compared to the growth in the wall of debt.

The well known comedy "Airplane" featured a passenger aircraft left without a pilot. As far as the world economy is concerned, we’d have to add “and the engine doesn’t work either”. That’s a plane and its passengers in a very bad situation.

In the face of this general debacle of the most developed countries, some, hoping to minimise the gravity of capitalism’s situation, point to the example of China and the “emerging” countries. Only a few months ago China was sold to us as the next locomotive of the world economy, with a little help from India and Brazil. What’s the reality here? These “motors” are also having some serious problems. On 13th July China officially announced a growth rate of 7.6%, which is the lowest figure for this country since the beginning of the current phase of the crisis. The times of double-digit growth are over. And even 7% doesn’t convince the specialists. They all know that it’s false. These experts prefer to look at other figures which they feel are more reliable. This is what was said that same day by a radio that specialises in economics (BFM): “by looking at the evolution of electricity consumption, you can deduce that China’s growth is actually around 2 or 3%. Or less than half the official figure”. At the beginning of this summer all the growth figures were at half-mast. Everywhere they are diminishing. The motor is more or less running on empty. The plane is about to sink to the earth, and the world economy with it.

Capitalism is entering period of major storms

Faced with the world recession and the financial state of the banks and states, there is open economic war between different sectors of the bourgeoisie. Boosting the economy with classic Keynesian policies (which require further state debt) can no longer be really effective. In the context of recession, the money collected by the states can only diminish and, despite the generalised austerity, their sovereign debts can only continue to explode, like in Greece or now Spain. The question that is tearing the bourgeoisie apart is this: “Do we risk once again raising the ceiling of debt?” More and more, money is not going towards production, investment or consumption. It’s no longer profitable. But the interest on debt and the need to repay it don’t go away. Capital will have to create more money to put off a generalised cessation of payment. Bernanke, head of the US central bank, and his counterpart Mario Draghi in the Eurozone, like all their cohorts across the planet, are hostages to the capitalist economy. Either they do nothing, in which case depression and bankruptcy will soon take the form of a cataclysm. Or they again inject massive amounts of money and that will very soon destroy the value of money. One thing is for sure: even if it can now see the danger, the bourgeoisie, hopelessly divided over these issues, will only react in situations of absolute emergency, at the last minute, and on an increasingly inadequate level. The crisis of capitalism which we have seen so openly since 2008 is only just beginning.

Tino (30.7.12)

1. We should note that since this article was written, the French government has gone back to cooperating more with the German chancellor. Perhaps it would be better to start talking about “Merkhollande”? In any case in September 2012, the new President Hollande and the leadership of the French Socialist Party waged a campaign to force parliament’s hand and get it to vote for the Stability Pact (the “Golden Rule”) which as a candidate Hollande has promised to renegotiate. As Charles Pasqua, an old Gaullist veteran known for his cynicism, put it: “electoral promises only commit those who believe them”.

People:

- Angela Merkel [3]

- Ben Bernanke [4]

- Mariano Rajoy [5]

- Mario Monti [6]

- François Hollande [7]

Recent and ongoing:

- Euro summit 2012 [8]

Rubric:

Mexico between crisis and narcotrafic

- 3684 reads

The press and television news around the world regularly send images of Mexico in which fighting, corruption and murder resulting from the “war against drug trafficking” are brought to the fore. But all this appears as a phenomenon alien to capitalism or abnormal, whereas in fact all the barbaric reality that goes with it is deeply rooted in the dynamics of the current system of exploitation. It is, in its full extent, the behaviour of the ruling class that is revealed, through competition and heightened political rivalries between its various fractions. Today, such a process of plunging into barbarism and the decomposition of capitalism is effectively dominant in certain regions of Mexico.

At the beginning of the 1990s, we said that “Amongst the major characteristics of capitalist society's decomposition, we should emphasise the bourgeoisie's growing difficulty in controlling the evolution of the political situation.”1 This phenomenon appeared more clearly in the last decade of the 20th century when it became a major trend.

It is not only the ruling class that is affected by decomposition; the proletariat and other exploited classes also suffer its most pernicious effects. In Mexico, mafia groups and the actual government enrol, for the war in which they are engaged, elements belonging to the most impoverished sectors of the population. The clashes between these groups, which indiscriminately hit the population, leaving hundreds of victims on the casualty list, the government and mafias call “collateral damage.” The result is a climate of fear that the ruling class has used to prevent and contain social reactions to the continuous attacks on the living conditions of the population.

Drug trafficking and the economy

In capitalism, drugs are nothing more than a commodity whose production and distribution necessarily requires labour, even if it is not always voluntary or waged. Slavery is common in this environment, which not only employs the voluntary and paid labour of a lumpen milieu for criminal activities, but also of labourers and others like carpenters (for example, for the construction of houses and shops) who are forced, in order to survive in the misery offered by capitalism, to serve the capitalist producers of illegal goods.

What is experienced today in Mexico has already existed (and still exists) in other parts of the world: the mafias profit from this misery, and their collusion with the state structures allows them to “protect their investment” and their activities in general. In Colombia, in the 1990s, the investigator H. Tovar-Pinzón gave a number of factors to explain why poor peasants became the first accomplices of the drug trafficking mafias: “A property produced, for example, ten cargoes of corn per year which permitted a gross receipt of 12,000 Colombian pesos. This same property could produce a hundred arrobas of coca, which represented for the owner a gross revenue of 350,000 pesos per year. Why not change the crop when one can gain thirty times more?”.2

What happened in Colombia has expanded across the whole of Latin America, drawing into drug trafficking, not only the peasant proprietors, but also the great mass of landless labourers who sell their labour power to them. This great mass of workers becomes easy prey to the mafia, because of the extremely low wages granted by the legal economy. In Mexico, for example, a labourer employed to cut sugar cane receives little more than two dollars per ton (27 pesos) and will see his wage increased when he produces an illegal commodity. In doing so, a large portion of workers employed in this activity loses its class condition. These workers are increasingly implicated in the world of organised crime and in direct contact with the gunmen and drug carriers with whom they share directly a daily life in a context of the trivialisation of murder and crime. Closely involved in this atmosphere, the contagion leads them progressively towards lumpenisation. This is one of the harmful effects of advanced decomposition directly affecting the working class.

There are estimates that the drug trafficking mafias in Mexico employ 25% more people than McDonald's worldwide.3 It should also be added that beyond the use of farmers, mafia activity involves racketeering and prostitution imposed on hundreds of young people. Today, drugs are an additional branch of the capitalist economy, that is to say that exploitation is present in it as in any other economic activity but, in addition, the conditions of illegality push competition and the war for markets to take much more violent forms.

The violence to gain markets and increase profits is all the fiercer with the importance of the gain. Ramón Martinez Escamilla, member of the Economic Research Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, believes that “the phenomenon of drug trafficking represents between 7 and 8 % of Mexico’s GDP”.4 These figures, compared to the 6% of Mexico’s GDP which represents the fortune of Carlos Slim, the biggest tycoon in the world, give an indication of the growing importance of the drug trade in the economy, permitting us to deduce the barbarity that it engenders. Like any capitalist, the drug trafficker has no other objective than profit. To explain this process, it is enough to recall the words of the trade unionist Thomas Dunning (1799-1873), quoted by Marx:

“With adequate profit, capital is very bold. A certain 10 per cent will ensure its employment anywhere; 20 per cent certain will produce eagerness; 50 per cent, positive audacity; 100 per cent will make it ready to trample on all human laws; 300 per cent, and there is not a crime at which it will scruple, nor a risk it will not run, even to the chance of its owner being hanged. If turbulence and strife will bring a profit, it will freely encourage both.”5

Based on contempt for human life and on exploitation, these vast fortunes certainly find refuge in tax havens but are also used directly by the legal capitalists who are responsible for the task of laundering them. Examples abound to illustrate this, such as the entrepreneur Zhenli Ye Gon, or more recently, the financial institution HSBC. In these two examples, it was revealed that the individual or institution was laundering the vast fortunes of the drug cartels, whether it was for the promotion of political projects (in Mexico and elsewhere) or for “honourable” investments.

Edgar Buscaglia6 states that companies of all kinds have been “designated as dubious by intelligence agencies in Europe and the United States, including the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the U.S. Treasury Department, but nobody has wanted to undermine Mexico, basically because many of them fund election campaigns.”7

There are other marginal processes (but no less significant) that enable the integration of the mafia in the economy, such as the violent depopulation of properties and of vast territories, to the extent that some areas of the country are now “ghost towns”. Some figures suggest the displacement, in recent years, of a million and a half people fleeing “the war between the army and the narcos.”8

It is essential to point out the impossibility, for the plans of the drug mafias, of existing outside the realm of the states. These are the structures that protect and help them move their money towards the financial giants, but are also the seat of the government teams of the bourgeoisie who mix their interests with those of drug cartels. It is obvious that the mafia could hardly have as much business if they did not receive the support of sectors of the bourgeoisie involved in the governments. As we have argued in the “Theses on Decomposition”, “it is more and more difficult to distinguish the government apparatus from gangland.”9

Mexico, an example of advanced capitalist decomposition

Since 2006, almost sixty thousand people have been killed, either by the bullets of the mafia units or those of the official army; a majority of those killed were victims of the war between drug cartels, but this does not diminish the responsibility of the state, whatever the government says. It is impossible to blame one or the other, because of the links between the mafia groups and the state itself. If difficulties have been growing at this level, it is precisely because the fractures and divisions within the bourgeoisie are amplified and, at any time, any place, can become a battleground between fractions of the bourgeoisie; of course, the state structure itself is also a place to where these conflicts are expressed. Each mafia group emerges under the leadership of a fraction of the bourgeoisie, and so the economic competition that these political quarrels create makes these conflicts grow and multiply day by day.

In the 19th century, during the ascendant period of capitalism, the drugs trade (opium for example) was already the cause of political difficulties leading to wars, revealing the barbaric essence of this system in the states’ direct involvement in the production and distribution of goods such as drugs. However, such a situation was still inseparable from the strict vigilance and the maintenance of a framework of firm discipline on this business by the state and the dominant class, allowing it to reach political agreements and avoiding anything that that would weaken the cohesion of the bourgeoisie.10 Thus, even if the “Opium War” - declared principally by the British state - illustrated a behavioural trait of capital, we can understand why the drug trade was not, however, a dominant phenomenon of the 19th century.

The importance of drugs and the formation of mafia groups become increasingly important during the decadent phase of capitalism. While the bourgeoisie tried to limit and adjust by laws and regulations the cultivation, preparation and trafficking of certain drugs during the first decades of the 20th century, this was only in order to properly control the trade of this commodity.

The historical evidence shows that “drug industry” is not an activity divorced from the bourgeoisie and its state. Rather, it is this same class that is responsible for expanding its use and profiting from the benefits it provides, and at the same time expanding its devastating effects in humans. States in the 20th century, have massively distributed drugs to armies. The United States gives the best example of such use to “stimulate” the soldiers during the war: Vietnam was a huge laboratory and it is not surprising that it was effectively Uncle Sam who encouraged the demand for drugs in the 1970s, and responded by boosting their production in the countries of the periphery.

At the beginning of the second half of the 20th century in Mexico, the importance of the production and distribution of drugs was still far from being significant and remained under the strict control of government authorities. The market was also tightly controlled by the army and the police. From the 1980s, the American government encouraged the development of the production and consumption of drugs in Mexico and throughout Latin America.

The “Iran-Contra” affair (1986) revealed that the government of Ronald Reagan, to overcome reductions in the budget to support armed bands opposed to the Nicaraguan government (the “contras”), used funds from the sale of arms to Iran and, especially, from drug trafficking via the CIA and the DEA. The government of the United States pushed the Colombian mafias to increase production, even deploying, to this end, military and logistical support to the governments of Panama, Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, Colombia and Guatemala, to facilitate the passage of this coveted commodity. To “expand the market”, the American bourgeoisie began to produce cocaine derivatives much more cheaply and therefore easier to sell massively, despite being more devastating.

These same practices, used by the American ‘godfather’ to raise funds to enable it to carry out its putchist adventures, have also been used in Latin America to fight against the guerrillas. In Mexico, the so-called “dirty war” waged by the state in the 1970s and 80s against the guerrillas was financed by the money coming from drugs. The army and paramilitary groups (such as the White Brigade or the Jaguar Group) then had carte blanche to murder, kidnap and torture. Some military projects like “Operation Condor” (which supposedly targeted drug production), were actually directed against the guerrillas and served at the same time to protect poppy and marijuana crops.

At that time, the discipline and cohesion of the Mexican bourgeoisie permitted it to keep the drug market under control. Recent journalistic enquiries say that there was absolutely no drug shipment that was beyond the control and supervision of the army and federal police.11 The state assured, under a cloak of steel, the unity of all sectors of the bourgeoisie, and when a group or individual capitalist showed disagreements, it was settled peacefully through privileges or power sharing. Thus was unity maintained in the so-called “revolutionary family.”12

With the collapse of the Eastern imperialist bloc the unity of the opposing bloc led by the United States also disappeared, which in turn provoked a growth of “every man for himself” among the different national fractions of certain countries. In Mexico, this breakdown showed itself in the dispute in broad daylight between fractions of the bourgeoisie at all levels: parties, clergy, regional governments, federal governments... Each fraction was trying to gain a greater share of power, without any of them taking the risk of putting into question the historic discipline behind the United States.

In the context of this general brawl, opposing bourgeois forces have fought over the distribution of power. These internal pressures have led to attempts to replace the ruling party and “decentralise” the responsibilities of law enforcement. Thus local authorities, represented by the state governments and the municipal presidents have declared their regional control. This, in turn, has added to the chaos: the federal government and each municipality or region, in order to reinforce its political and economic control, has associated itself with a particular mafia band. Each ruling fraction protects and strengthens this or that cartel according to its interests, thus ensuring impunity, which explains the violent arrogance of the mafias.

The magnitude of this conflict can be seen in the settling of accounts between political figures. It is estimated for example that in the last five years, twenty-three mayors and eight municipal presidents have been assassinated, and the threats made to secretaries of state and candidates are innumerable. The bourgeois press tries to pass off the people murdered as victims who, in the majority of cases, have been the subjects of a settling of scores between rival gangs or within these bands, for treachery.

By analysing these events we can understand that the drug problem cannot be resolved within capitalism. To limit the excesses of barbarism, the only solution for the bourgeoisie is to unify its interests and to regroup around a single mafia band, thus isolating the other bands to keep them in a marginal existence.

The peaceful resolution of this situation is very unlikely, especially because of the acute division between bourgeois factions in Mexico, making it difficult and unlikely to achieve even a temporary cohesion permitting a pacification. The dominant trend seems to be the advance of barbarism... In an interview dated June 2011, Buscaglia estimated the magnitude of drug trafficking in the life of the bourgeoisie: “Nearly 65% of electoral campaigns in Mexico are contaminated by money from organised crime, mainly drug trafficking”.13

Workers are the direct victims of the advance of capitalist decomposition expressed through phenomena such as “the war against drugs” and they are also the target of the economic attacks imposed by the bourgeoisie faced with the deepening of the crisis; this is undoubtedly a class that suffers from great poverty, but it is not a contemplative class, it is a body capable of reflecting, of becoming conscious of its historical condition and reacting collectively.

Decay and crisis ... capitalism is a system in putrefaction

Drugs and murder are major news items both inside and outside the country, and if the bourgeoisie gives them such importance it is also because this allows it to disguise the effects of the economic crisis.

The crisis of capitalism did not originate in the financial sector, as claimed by the bourgeois “experts”. It is a profound and general crisis of the system that spares no country. The active presence of mafias in Mexico, although it weighs heavily on the exploited, does not erase the effects on them of the crisis; quite the contrary, it makes them worse.

The main cause of the tendencies towards recession affecting global capitalism is widespread insolvency, but it would be a mistake to believe that the weight of sovereign debt is the only indicator to measure the advance of the crisis. In some countries, such as Mexico, the weight of indebtedness does not create major problems yet, though in the last decade, according to the Bank of Mexico, sovereign debt has increased by 60% to reach 36.4% of GDP at the end 2012 according to forecasts. This amount is obviously modest when compared to the level of debt of countries like Greece (where it has reached 170% of GDP), but does this imply that Mexico is not exposed to the deepening crisis? The answer of course is no.

Firstly, the fact that indebtedness is not as important in Mexico than in other countries does not mean that it will not become so.

The difficulties of the Mexican bourgeoisie in reviving capital accumulation are illustrated particularly in the stagnation of economic activity. GDP is not even able to reach its 2006 levels (see Figure 1) and, moreover, the recent fleeting embellishment has concerned the service sector, especially trade (as explained by the state institution in charge of statistics, the INEGI). Furthermore, it must also be taken into consideration that if this sector boosts domestic trade (and permits GDP to grow), this is because consumer credit has increased (at the end of 2011 the use of credit cards increased by 20 % compared to the previous year).

The mechanisms used by the ruling class to confront the crisis are neither new nor unique to Mexico: increasing levels of exploitation and boosting the economy through credit. The application of such measures helped the United States in the 1990s to give the illusion of growth. Anwar Shaikh, a specialist in the American economy, explains: “The main impetus for the boom came the dramatic fall in the rate of interest and the spectacular collapse of real wages in relation to productivity (growth of the rate of exploitation), which together raised significantly the rate of profit of the company. Both variables played different roles in different places...”14

The mechanisms used by the ruling class to confront the crisis are neither new nor unique to Mexico: increasing levels of exploitation and boosting the economy through credit. The application of such measures helped the United States in the 1990s to give the illusion of growth. Anwar Shaikh, a specialist in the American economy, explains: “The main impetus for the boom came the dramatic fall in the rate of interest and the spectacular collapse of real wages in relation to productivity (growth of the rate of exploitation), which together raised significantly the rate of profit of the company. Both variables played different roles in different places...”14

Such measures are repeated at the pace of the advance of the crisis, even though their effects are more and more limited, because there is no alternative but to continue to use them, further attacking the living conditions of the workers. Official figures, for what they’re worth, attest to the precariousness of these solutions. It is not surprising that the health of Mexican workers is based on the cheapest available calories in sugar (the country is the second largest consumer of soft drinks after the United States, every Mexican consuming some 150 litres on average per year) or cereals.

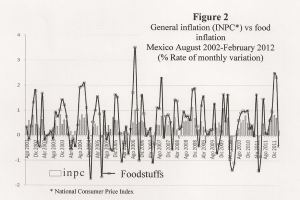

It is therefore not surprising that Mexico is a country whose adult population is more prone to problems of obesity which culminate in chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. Degradation of living conditions has reached such extremes that more children between 12 and 17 are forced to work (according to CEPALC, 25% in rural areas and 15% in the city). By compressing wages, the bourgeoisie has managed to claw back financial resources destined for consumption by the workers, seeking to increase the mass of surplus value appropriated by the capital. This situation is even more serious for the living conditions of the working class, as shown in Figure 2, because food prices are rising faster than the general price index used by the state to assert that the problem of inflation is under control.

Spokespersons for Latin American governments start from the principle that if economic conflicts affect the central countries (the United States and Europe), the rest of the world is untouched by this dynamic, especially as the IMF and the ECB are supplied with liquidity by the governments of these regions, including Mexico. But this does not mean at all that these economies are not threatened by the crisis. These same insolvency processes that spread throughout Europe today were the lot of Latin America during the 1980s and, with them, the severe measures arising from draconian austerity plans (which gave rise to what was called the Washington Consensus).

Spokespersons for Latin American governments start from the principle that if economic conflicts affect the central countries (the United States and Europe), the rest of the world is untouched by this dynamic, especially as the IMF and the ECB are supplied with liquidity by the governments of these regions, including Mexico. But this does not mean at all that these economies are not threatened by the crisis. These same insolvency processes that spread throughout Europe today were the lot of Latin America during the 1980s and, with them, the severe measures arising from draconian austerity plans (which gave rise to what was called the Washington Consensus).

The depth and breadth of the crisis can be manifested differently in different countries, but the bourgeoisie uses the same strategies in all countries, even those who are not strangled by increasing sovereign debt.

The plans to reduce costs that the bourgeoisie applies less and less discreetly, the layoffs and increased exploitation, cannot in any way promote any recovery.

The rates of unemployment and impoverishment achieved by Mexico help us to understand how the crisis extends and deepens elsewhere. Coparmex, the employers' organisation, recognises that in Mexico 48% of the economically active population is in “underemployment”,15 which in more straightforward language means in a precarious situation: low wages, temporary contracts, days getting longer and longer without any medical insurance. This mass of the unemployed and precarious is the product of “labour flexibility” imposed by the bourgeoisie to increase exploitation and to push the main effects of the crisis onto our shoulders.

Poverty and exploitation are the drivers of discontent

Many regions, mainly in rural areas, which are subject to curfew and constant supervision by armed patrols, whether military, police or mafia (if not both), and who murder under the slightest pretext, make life a nightmare for the exploited. To this are added the permanent attacks on the economic level. In early 2012, the Mexican bourgeoisie announced a “labour reform” which, as elsewhere in the world, will bring the cost of the labour force down to a more attractive level for capital, thus reducing production costs and further increasing the rate of exploitation.

The “labour reform” aims to increase the rates and hours of work, but also to lower wages (reduction of direct wages and elimination of substantial parts of the indirect wage), the project also providing for increases in the number of years of service required to qualify for retirement.

This threat began to materialise in the education sector. The state has chosen this area to make an initial attack that will be a warning to others elsewhere. It can afford to do this because although the workers are numerous and have a great tradition of militancy, they are very tightly controlled by the trade union structure, both formal (National Union of Education Workers – SNTE) and “democratic” (National Coordination of Education Workers – CNTE). Thus the government was able to deploy the following strategy: first causing discontent by announcing a “universal assessment”16, and then staging a series of manoeuvres (interminable demonstrations, negotiations separated by region...), relying on the unions to exhaust, isolate and thus defeat the strikers, convincing them of the futility of the “struggle “and so demoralising and intimidating all workers.

Although teachers have been the subject of special treatment, the “reforms” apply nevertheless gradually and unobtrusively to all workers. The miners, for example, are already experiencing these attacks which reduce the cost of the labour force and make their working conditions more precarious. The bourgeoisie considers it normal that, for a pittance (the maximum salary a miner can claim is $455 per month), workers spend in the pits and galleries long and intensive working days which often well exceed eight hours, in unspeakable safety conditions worthy of those that prevailed in the 19th century. It is this that explains, on the one hand, why the profit rate of mining companies in Mexico is among the highest, and on the other, the dramatic increase in “accidents” in the mines, with their growing tally of wounded and dead. Since 2000, in the one state of Coahuila, the most active mining area in the country, more than 207 workers have died as a result of collapsing galleries or firedamp explosions.

This misery, to which is added the criminal activities of the governments and the mafias, provokes a growing discontent among the exploited and oppressed which begins to express itself, even if it is still with great difficulties. In other countries such as Spain, Britain, Chile, Canada, the streets have been overrun with demonstrations expressing the courage to fight against the reality of capitalism, even though this was not yet clearly the force of a class in society, the working class.

In Mexico, the mass protests called by students of the “#yo soy 132” (“I am 132”) movement, although they have been framed from the outset by the electoral campaign of the bourgeoisie for the presidential elections, are nevertheless the product of a social unrest which is smouldering. It is not to console ourselves that we affirm this; we don’t delude ourselves with the illusion of a working class advancing unabated in a process of struggle and clarification, we are just trying to understand reality. We need to take into account that the development of mobilisations throughout the world is not homogeneous and that within them, the working class as such does not assume a dominant position. Because of its difficulty to recognise itself as a class in society with the capacity to constitute a force within it, the working class lacks confidence in itself, is afraid to launch itself in the struggle and to lead that struggle. Such a situation promotes, within these movements, the influence of bourgeois mystifications which put forward reformist “solutions” as possible alternatives to the crisis of the system. This general trend is also present in Mexico.

It is only by recognising the difficulties faced by the working class that we can understand that the movement animating the creation of the group “# yo soy 132” also expresses the disgust with governments and parties of the ruling class. The latter was able to react very quickly to the threat by linking the group to the false hopes raised by the elections and democracy, and converting it into a hollow organ, useless to the struggle of the exploited (who were coming closer to this group believing that it had found a way to fight), but very useful to the bourgeoisie which continues to use “#yo soy 132” to divert the combativity of young workers outraged by the reality of capitalism.

The ruling class knows perfectly well that increasing attacks will inevitably provoke a response from the exploited. José A Gurría, Secretary-General of the OECD, expressed this in these terms on February 24: “What can happen when you mix the decline in growth, high unemployment and growing inequality? The result can only be the Arab Spring, the Indignants of Puerta del Sol and those in Wall Street”. That is why, faced with this latent discontent, the Mexican bourgeoisie promotes the campaign protesting the election of Pena Nieto1718 to the presidency of the republic, a unifying slogan that sterilises any combativity, along with the more radical statements of Lopez Obrador181819 and of “# yo soy 132” ensuring that nothing will go further than the defence of democracy and its institutions.

Accentuated by the adverse effects of decomposition, the capitalist crisis has generalised the impoverishment of the proletariat and other oppressed but has thereby shown the naked reality, in all its cruelty: capitalism can offer us nothing but unemployment, poverty, violence and death.

The profound crisis of capitalism and the destructive advance of decomposition announces the dangers that represent the survival of capitalism, affirming the imperative necessity of its destruction by the only class capable of confronting it, the proletariat.

Rojo, March 2012

1 1. See International Review n 62, “Decomposition, final phase of the decadence of capitalism” point 9.

2 2. Nueva sociedad no. 130, Columbia, 1994, “The economy of coca in Latin America. The Colombian paradigm” (our translation).

3 3. Cf. See “Narco SA, una empresa global” [10] on www.cnnexpansion.com [11].

44. La Jornada , 25 June 2010 (our translation).

55. Karl Marx, Capital, Volume I, “The development of capitalist production”; Section VIII, “Primitive accumulation”, Chapter XXXI, “Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist”, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch31.htm [12]

66. International Programme Coordinator for Justice and Development at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico (ITAM).

77. La Jornada , 24 March, 2010 (our translation).

88. In the northern states of the country such as Durango, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas, some areas are considered “ghost towns” after being abandoned by the population. Villagers who were engaged in agriculture have been obliged to flee, liquidating their property at low prices in the best case or abandoning it altogether The plight of workers is even more serious because their mobility is limited due to lack of means, and when they manage to flee to other areas, they are forced to live in the worst conditions of insecurity, in addition to continuing to repay loans for housing they were forced to abandon.

99. �See International Review no. 62, op. cit., point 8.

1010. Even today, for some countries such as the United States, despite being the largest consumers of drugs, the armed clashes and the casualties they cause are mainly concentrated outside their borders.

1111.� See Anabel Hernández, Los del narco Señores (“Drug Lords”), Edition Grijalbo, Mexico 2010.

1212.� This is the so-called unity that the bourgeoisie had achieved with the creation of the National Revolutionary Party (PNR, 1929), which was consolidated by transforming it into the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that remained in power until 2000.

1313.� See “Edgardo Buscaglia [13]: el fracaso de la guerra contra el narco - Por el diario Alemán Die Tageszeitung” [13] on nuestraaparenterendicion.com

1414. In “The first great depression of the 21st century” [14] 2010.

15 The official institution (INEGI) for its part calculates that the rate of “informal” workers is 29.3%.

16 “The universal assessment” is part of the “Alliance for Education Quality” (ACE). This is not only to impose an evaluation system to make workers compete with each other and reduce the number of positions, but also to increase the workload, compress wages, facilitate rapid redundancy protocols and low-cost pensions...

17. Leader of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (social democrat).

18. Leader of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (left social democrat).

Geographical:

- Mexico [15]

Recent and ongoing:

- Mexican drug wars [16]

Rubric:

The state in the period of transition from capitalism to communism (ii)

- 3960 reads

Our response to the group Oposição Operária (Workers’ Opposition) - Brazil

We are publishing below our response to the article “Workers’ councils, proletarian state, dictatorship of the proletariat” by the group Oposição Operária (OPOP)1 in Brazil, which appeared in the International Review n° 148.2

The position developed in the article by OPOP essentially takes up the work of Lenin’s The State and Revolution, and it’s from this point of view that the group rejects a central idea of the ICC’s position. This position, while recognising the fundamental contribution of The State and Revolution to the understanding of the question of the state during the period of transition, uses the experience of the Russian revolution, reflections by Lenin himself during this period, and the fundamental writings of Marx and Engels, in order to draw lessons which lead us to call into question the identity between the state and the dictatorship of the proletariat classically accepted up to now by the marxist currents.

In its article, OPOP also develops another position of its own regarding what it calls the “pre-state”, that’s to say the organisation of the councils before the revolution called upon to overthrow the bourgeoisie and its state. We will return later to this question, because we think that the priority is first of all to make our divergences with the OPOP clear concerning the question of the state and the period of transition.

The main aspects of OPOP's thesis

So as to avoid the reader going backwards and forwards to OPOP’s article in International Review n° 148 we are going to reproduce the passages that we consider the most significant.

For the OPOP, the “paradoxical separation between the system of councils and the post-revolutionary state” “distances itself from the conception of Marx, Engels and Lenin and reflects a certain influence of the anarchist conception of the state” thus amounting to “breaking the unity that should exist and exists under the dictatorship of the proletariat”. In fact, “such a separation places, on the one hand, the state as a complex administrative structure and managed by a body of officials – a nonsense in the simplified design of the state according to Marx, Engels and Lenin – and, on the other, a political structure in which the councils exert pressure on the state as such”.

It is an error which, according to the OPOP, is explained by the following incomprehensions in relation to the Commune-State and its relations with the proletariat:

-

“an accommodation to a vision influenced by anarchism that identifies the Commune-State with the bureaucratic (bourgeois) state”. This puts “the proletariat outside of the post-revolutionary state while actually creating a dichotomy that, itself, is the germ of a new caste reproducing itself in the administrative body separated organically from the workers’ councils”;

-

“the identification between the state that emerged in post-revolutionary Soviet Union – a necessarily bureaucratic state – with the conception of the Commune-State of Marx, Engels and Lenin himself”;

-

“the non-perception that the real simplification of the Commune-State, as described by Lenin in the words reported earlier, implies a minimum of administrative structure and that this structure is so small and in the process of simplification /extinction, that it can be assumed directly by the council system”.

Finally, according to OPOP, another factor intervenes in order to explain the erroneous lessons drawn by the ICC from the Russian revolution as to the nature of the state in the period of transition: it’s a question of our organisation not taking into account the unfavourable conditions with which the revolution was confronted: “a misunderstanding of the ambiguities that resulted from the specific historical and social circumstances that blocked not only the transition but also the beginning of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the USSR. Here, one ceases to understand that the dynamic taken by the Russian Revolution – unless you opt for the easy but very inconsistent interpretation in which deviations in the revolutionary process were the result of the policies of Stalin and his entourage – did not obey the conception of the revolution, the state and of socialism that Lenin had, but resulted from the restrictions of the social and political terrain from which the power of the USSR emerged, characterised among others, to recall, by the impossibility of the revolution in Europe, by civil war and the counter-revolution within the USSR. The resulting dynamic was foreign to the will of Lenin. He himself thought about this problem, but repeatedly came up with the ambiguous formulations present in this later thinking and just before his death”.

The inevitability of a transitional period and a state's existence within it

The difference between marxists and anarchists doesn’t reside in the fact that the former conceive of communism with a state and the latter as it being a society without a state. On this point, there is total agreement: communism can only be a society without a state. It was thus rather with the pseudo-marxists of social democracy, the successors of Lassalle, that such a fundamental difference existed, given that for them the state was the motor force of the socialist transformation of society. Engels wrote against them in the following passage of Anti-Duhring: “As soon as there is no longer any social class to be held in subjection; as soon as class rule, and the individual struggle for existence based upon our present anarchy in production, with the collisions and excesses arising from these, are removed, nothing more remains to be repressed, and a special repressive force, a state, is no longer necessary. The first act by virtue of which the state really constitutes itself the representative of the whole of society — the taking possession of the means of production in the name of society — this is, at the same time, its last independent act as a state. State interference in social relations becomes, in one domain after another, superfluous, and then dies out of itself; the government of persons is replaced by the administration of things, and by the conduct of processes of production. The state is not ‘abolished’. It dies out. This gives the measure of the value of the phrase ‘a free people’s state’,3 both as to its justifiable use at times by agitators, and as to its ultimate scientific insufficiency and also of the demands of the so-called anarchists for the abolition of the state out of hand.”4 The real debate with the anarchists is about their total misunderstanding of an inevitable period of transition and on the fact that they see history as an immediate and direct two-footed jump from capitalism into a communist society.

On this question of the necessity of the state during the period of transition, we are thus perfectly in agreement with OPOP. That’s why we are astonished that this organisation reproaches us for “distancing ourselves from the conception of Marx, Engels and Lenin by reflecting a certain influence of the anarchist conception of the state”. In what way can our position appear to approach that of the anarchists, according to whom “it is possible to abolish the state out of hand”?

If we base ourselves on what Lenin wrote in The State and Revolution regarding the marxist critique of anarchism on the question of the state, it appears that this is far from confirming OPOP’s point of view: “To prevent the true meaning of his struggle against anarchism from being distorted, Marx expressly emphasised the ‘revolutionary and transient form’ of the state which the proletariat needs. The proletariat needs the state only temporarily. We do not after all differ with the anarchists on the question of the abolition of the state as the aim. We maintain that, to achieve this aim, we must temporarily make use of the instruments, resources, and methods of state power against the exploiters, just as the temporary dictatorship of the oppressed class is necessary for the abolition of classes.”5 In a word, the ICC accepts this formulation as its own. It’s a question of Lenin’s qualification of the “revolutionary” transitory nature of the state. Can this difference be connected to a variant of anarchist ideas, as OPOP thinks, or on the contrary does it refer to a much more profound question of the state?

What is the real debate?

On the question of the state, our position effectively differs from that of The State and Revolution and of the Critique of the Gotha Programme according to which, during the period of transition, “the state will be nothing other than the dictatorship of the proletariat.”6 This is the basis of the debate between us: why can’t there be an identity between the dictatorship of the proletariat and the state in the period of transition that arises after the revolution? This is the idea, which has struck many marxists, who have asked the question: “Where does the ICC get its position from on the state in the period of transition?” We can respond: “Not from its imagination but rather from history, from the lessons drawn by generations of revolutionaries, from the reflections and theoretical elaborations of the workers’ movement”. In particular:

-

successive improvements in the understanding of the question of the state coming from the workers’ movement up to the Russian revolution, of which Lenin’s The State and Revolution gives a masterly account;

-

taking into account all of the theoretical considerations of Marx and Engels on the question of the state which in fact contradict the idea that the state in the period of transition could constitute the bearer of the socialist transformation of society;

-

the degeneration of the Russian revolution which shows that the state constituted the main carrier of the development of the counter-revolution within the proletarian bastion;

-

within this process, certain critical positions of Lenin in 1920-21 which demonstrated that the proletariat had to be able to defend itself against the state and which, while remaining imprisoned by the limitations of the dynamic of degeneration which led to the counter-revolution, bring an essential illumination on the nature and role of the transitional state.

It’s with this approach that a work of weighing up the world revolutionary wave was made by the Communist Left in Italy.7 According to the latter, if the state subsists after the taking of power by the proletariat given that social classes still exist, the former is fundamentally an instrument of the conservation of the status quo but in no way the instrument of the transformation of relations of production towards communism. In this sense, the organisation of the proletariat as a class, through its workers’ councils, must impose its hegemony on the state but never identify with it. It must be able, if necessary, to oppose the state, as Lenin partially understood in 1920-21. It is exactly because, with the extinction of the life of the soviets (inevitable from the fact of the failure of the world revolution), the proletariat had lost this capacity for acting and imposing itself on the state that the latter was able to develop its own conservative tendencies to the point of becoming the gravedigger of the revolution in Russia at the same time as it absorbed the Bolshevik Party itself, turning it into an instrument of the counter-revolution.

The contribution of history to the understanding of the state in the period of transition

Lenin’s The State and Revolution constituted, in its time, the best synthesis of what the workers’ movement had elaborated concerning the question of the state and the exercise of power by the working class.8 In fact this work offers an excellent illustration of the way that light is thrown on the question of the state through historical experience. By basing ourselves on its content we take up here the successive clarifications of the workers’ movement on these questions:

-

The Communist Manifesto of 1848 shows the necessity for the proletariat to take political power, to constitute itself as the dominant class, and sees this power as being exercised by means of the bourgeois state which will have been conquered by the proletariat: “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.”9

-

In The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1851), the formulation was already becoming more “precise” and “concise” (according to Lenin’s own terms) than that in the Communist Manifesto. In fact, for the first time the question arises of the necessity to destroy the state: “All revolutions perfected this machine instead of breaking it. The parties, which alternately contended for domination, regarded the possession of this huge state structure as the chief spoils of the victor.”10

-

Through the experience of the Paris Commune (1871), Marx saw, as did Lenin, “a real step much more important than a hundred programmes and arguments”,11 which justified, in his eyes and those of Engels, that the programme of the Communist Manifesto, becoming“ antiquated in some details”,12 is modified through a new preface. The Commune has notably demonstrated, they continued, that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes.”13

The 1917 revolution did not leave time for Lenin to write in The State and Revolution chapters dedicated to the contributions of 1905 and February 1917. Lenin limited himself to identifying the soviets as the natural successors of the Paris Commune. One could add that even if these two revolutions did not allow the proletariat to take political power, they did however furnish supplementary lessons in relation to the experience of the Paris Commune concerning the power of the working class: the soviets of workers’ deputies based upon assemblies held in the place of work turned out to be the most apt expression of proletarian class autonomy rather than the territorial units of the Commune.

Beyond constituting a synthesis of the best of what the workers’ movement had written on these questions, State and Revolution contained Lenin’s own developments which, in their turn, constituted advances. In effect, whereas they drew essential lessons from the Paris Commune, Marx and Engels had left an ambiguity as to the possibility that the proletariat would come to power peacefully through the electoral process in certain countries, ie. those that provided the most developed parliamentary institutions and the least important military apparatuses. Lenin wasn’t afraid to correct Marx by using the marxist method and put the question into the new historic context: “Today, in 1917, at the time of the first great imperialist war, this restriction made by Marx is no longer valid. [...]. Today, in Britain and America, too, ‘the precondition for every real people’s revolution’ is the smashing, the destruction of the ‘ready-made state machinery.’”14

Only a dogmatic vision could accommodate itself to the idea that The State and Revolution constituted the last and supreme stage in the clarification of the notion of the state in the workers’ movement. If there’s a work that’s the antithesis of such a vision it’s that of Lenin. OPOP itself is not afraid to distance itself from what Lenin literally said in The State and Revolution by pushing to its conclusion the idea of the preceding quote: “Today, the task of establishing the councils as a form of state organisation is not only situated in the perspective of a single country but at the international level and it’s here that the principal challenge is posed to the working class.”15

Written in August/September 1917, at the outbreak of the October revolution, The State and Revolution very quickly served as a theoretical weapon for revolutionary action for the overthrow of the bourgeois state and the setting up of the Commune-State. The lessons drawn from the Paris Commune up to then were thus put to the test of history through events of a much more considerable weight – the Russian revolution and its degeneration.

Can lessons be learnt from the world revolutionary wave of 1917?

OPOP responds negatively to this question when it tells us that the conditions were so unfavourable that they didn’t allow the setting up of a workers’ state such as Lenin described in The State and Revolution. Thus they reproach us for identifying “the state that emerged in the post-revolutionary Soviet Union – a necessarily bureaucratic state – with the conception of the Commune-State of Marx, Engels and Lenin himself” and adds “Here, one ceases to understand that the dynamic taken by the Russian revolution […] did not obey the conception of the revolution, the state and of socialism that Lenin had, but resulted from the restrictions of the social and political terrain from which the power of the USSR emerged.”

We are in agreement with OPOP in saying that the first lesson to be drawn from the degeneration of the Russian revolution concerns the effects of the international isolation of the proletarian bastion following the defeat of other revolutionary attempts in Europe; Germany in particular. In fact, not only can there be no transformation of relations of production towards socialism in a single country, but furthermore it is not possible that a proletarian power can maintain itself indefinitely in a capitalist world. But are there other lessons of great importance that can be drawn from this experience?

Yes, of course! And OPOP recognises one of them amongst others, although this explicitly contradicts the following passage in The State and Revolution in relation to the first phase of communism: “the exploitation of man by man will have become impossible because it will be impossible to seize the means of production - the factories, machines, land, etc.- and make them private property”16. In fact what the Russian revolution and above all the Stalinist counter-revolution shows is that the simple transformation of the productive apparatus into state property doesn’t suppress the exploitation of man by man.

In fact, the Russian revolution and its degeneration constitute historic events of such significance that one cannot fail to draw lessons from them. For the first time in history the proletariat of a country took political power as the most advanced expression of a world revolutionary wave, with the appearance of a state that was called proletarian! And then something happened that was equally unknown in the workers’ movement; the defeat of a revolution, not clearly and openly beaten down by the savage repression of the bourgeoisie as was the case of the Paris Commune, but as the consequence of a process of internal degeneration which took on the hideous face of Stalinism.

In the weeks following the October insurrection, the Commune-State is already something other than the “armed workers” described in The State and Revolution.17 Above all, with the growing isolation of the revolution, the new state was more and more infested with the gangrene of the bureaucracy, responding less and less to the organs elected by the proletariat and the poor peasants. Far from beginning to wither away, the new state was about to invade the whole of society. Far from bending to the will of the revolutionary class, it became the central point of a process of degeneration and internal counter-revolution. At the same time, the soviets were emptied of their life. The workers’ soviets were transformed into appendages of the unions in the management of production. Thus the force that made the revolution, and needed to maintain its control over it, lost its political and organised autonomy. The carrier of the counter-revolution was nothing more or less than the state and, the more that the revolution encountered difficulties, the more the power of the working class became weakened and the more the Commune-State manifested its non-proletarian nature, its conservative – even reactionary – side. We will explain this characterisation.

From Marx and Engels to the Russian experience: convergence towards the same characterisation of the state in the period of transition

It would be an error to definitively stop at the formulation of Marx in The Critique of the Gotha Programme concerning the characterisation of the state in the period of transition, identified as the dictatorship of the proletariat. In fact other characterisations of the state were made by Marx and Engels themselves, later by Lenin and then by the Communist Left, which fundamentally contradict the formulae Commune-State=dictatorship of the proletariat, in order to converge towards an idea of a state conservative by nature, including here the Commune-State in the period of transition.

The transitional state is the emanation of society and not of the proletariat

How does one explain the appearance of the state? In this regard Engels left no ambiguity: “The state is therefore by no means a power imposed on society from without; just as little is it ‘the reality of the moral idea,’ ‘the image and the reality of reason,’ as Hegel maintains.18 Rather, it is a product of society at a particular stage of development; it is the admission that this society has involved itself in insoluble self-contradiction and is cleft into irreconcilable antagonisms which it is powerless to exorcise. But in order that these antagonisms, classes with conflicting economic interests, shall not consume themselves and society in fruitless struggle, a power, apparently standing above society, has become necessary to moderate the conflict and keep it within the bounds of ‘order’; and this power, arisen out of society, but placing itself above it and increasingly alienating itself from it, is the state”.19 Lenin took this passage of Engels into account, quoting it in The State and Revolution. Despite all the arrangements put in place by the proletariat for the transitional Commune-State, the latter had in common with the states of all previous past societies the fact of being a conservative organ at the service of the maintenance of the dominant order, that is to say, of the economically dominant classes. This has implications at both the theoretical and practical levels concerning the following questions: Who exercises power during the society of transition, the state or the proletariat organised in workers’ councils? Which is the economically dominant class of the society of transition? What is the motor force for the social transformation of society and of the dying out of the state?

The state cannot by nature express the sole interests of the proletariat

Where the political power of the bourgeoisie has been overturned, relations of production remain capitalist relations even if the bourgeoisie is no longer there to appropriate the surplus value produced by the working class. The point of departure of a communist transformation is based upon the military defeat of the bourgeoisie in a sufficient number of decisive countries to give a political advantage to the working class at a global level. This is the period during which the bases of a new mode of production slowly develop to the detriment of the old, up to the point where they supplant it and constitute the new mode of production.

After the revolution and as long as the world human community has not yet been realised, ie. as long as the immense majority of the world population has not been integrated into free and associated production, the proletariat remains an exploited class. Thus, contrary to revolutionary classes of the past, the proletariat is not destined to become the economically dominant class. For this reason, even if the established order after the revolution is no longer that of the economic and political dominance of the bourgeoisie, the state, which rises up during this period as the guarantor of the new economic order, cannot intrinsically be at the service of the proletariat. On the contrary, it is up to the latter to constrain it in the direction of its own class interests.

The role of the transitional state: the integration of the non-exploited population into the management of society and the struggle against the bourgeoisie

In The State and Revolution, Lenin himself said that the proletariat needed the state to suppress the resistance of the bourgeoisie, but also to lead the non-exploited population in the socialist direction: “The proletariat needs state power, a centralised organisation of force, an organisation of violence, both to crush the resistance of the exploiters and to lead the enormous mass of the population — the peasants, the petty bourgeoisie, and semi-proletarians — in the work of organising a socialist economy.”20

We support Lenin’s point of view here, according to which, in order to overthrow the bourgeoisie, the proletariat must be able to bring behind it the immense majority of the poor and the oppressed, among which it can itself be a minority. Any alternative to such a policy doesn’t exist. How was this concretised in the Russian revolution? Two types of soviets emerged: on the one hand, soviets based essentially on the centres of production and regrouping the working class, called workers’ councils; on the other, soviets based on territorial units (territorial soviets) in which all the layers of the non-exploited actively participated in the local management of that society. The workers’ councils organised the whole of the working class, that is to say, the revolutionary class. The territorial soviets,21 meanwhile, based on revocable delegates, were intended to be part of the Commune-State,22 the latter having the function of managing society as a whole. In the revolutionary period, all of the non-exploited layers, while being for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and against the restoration of its domination, have not necessarily accepted the idea of the socialist transformation of society. They could even be hostile to it. In fact, within these layers, the proletariat can be in a small minority. That’s the reason why, in Russia, measures were taken in the means of electing delegates so that the weight of the working class within the Commune-State could be strengthened: 1 delegate for 125,000 peasants, 1 delegate for 25,000 workers of the towns. But this did not take away the necessity to mobilise the largely peasant population against the bourgeoisie and to integrate it into the process of the running of society, giving birth, in Russia, to a state which was made up not only of delegates of workers’ soviets, but also delegates of soldiers and poor peasants.

Marxism warns of the danger from the state during the period of transition

In his 1891 introduction to The Civil War in France, and written on the twentieth anniversary of the Paris Commune, Engels wasn’t afraid to put forward common traits of all states, whether classical bourgeois states or the Commune-State of the period of transition: “In reality, however, the state is nothing but a machine for the oppression of one class by another, and indeed in the democratic republic no less than in the monarchy; and at best an evil inherited by the proletariat after its victorious struggle for class supremacy, whose worst sides the proletariat, just like the Commune, cannot avoid having to lop off at the earliest possible moment, until such time as a new generation, reared in new and free social conditions, will be able to throw the entire lumber of the state on the scrap-heap.”23 Considering the state as “an evil inherited by the proletariat after its victorious struggle for class supremacy”24 is an idea perfectly logical with the notion that the state is an emanation of society and not of the revolutionary proletariat. And this has heavy implications regarding the necessary relations between the state and the revolutionary class. Even if these were not able to be completely clarified before the Russian revolution, Lenin was inspired by it in his strong insistence, in The State and Revolution, on the need for the workers to submit all the members of the state to constant supervision and control, particularly the elements of the state which most evidently embodied a certain continuity with the old regime, such as technical and military “experts” that the soviets will be forced to use.