Pamphlet: The Decadence of Capitalism

- 22043 reads

This pamphlet is now available online here.

Heritage of the Communist Left:

The Decadence of Capitalism - Introduction

- 6340 reads

In order to know whether the communist revolution is necessary and possible today, we have to pose the question of the decadence of capitalism, to define the historic basis of the programme and strategy of the proletariat in the present epoch.

Questions such as the content of socialism, the nature of the unions, the politics of ‘frontism’, the nature of national liberation movements, are intimately linked to an analysis of the decadence of capitalism.

Decadence theory in the history of the workers’ movement

It is not because the immense majority of men are exploited and thus alienated that socialism is a historic necessity today. Exploitation and alienation already existed under slavery, feudalism, and nineteenth century capitalism, but socialism could not possibly have been realised in any of those epochs.

For socialism to become a reality not only must the means for its instigation (the working class and the means of production) be sufficiently developed, but also the system which it is to supersede - capitalism - must have ceased to be a system indispensable to the development of the productive forces, must have become a growing fetter on the productive forces, that is to say, that it must have entered its period of decline or decadence.

The socialists of the early nineteenth century regarded socialism as an ideal to be attained, and its realisation was to result from the sheer good will of men - in the case of the ‘utopian’ socialists, from the good will of the ruling class itself. The enduring contribution of Marx and Engels was their understanding and scientific elaboration of the material necessity for the disappearance of capitalism and the realisation of communism. It is no accident that when Marx attempted to encapsulate the essence of his work in a single passage, he concentrated on the mechanisms of the historic growth and decay of the various modes of production through which humanity has developed:

“In the social production of their life, men enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will, relations of production which correspond to a definite stage of development of their material productive forces. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of their development, the material productive forces of society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or - what is but a legal expression of the same thing - with the property relations within which they have been at work hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an epoch of social revolution. With the change of the economic foundation the entire immense superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed. In considering such transformations a distinction should always be made between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic - in short ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. Just as our opinion of an individual is not based on what he thinks of himself, so we cannot judge such a period of transformation by its own consciousness; on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained rather from the contradictions of material life, from the existing conflict between the social productive forces and the relations of production. No social order ever perishes before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have developed; and new, higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence hove matured in the womb of the old society itself. Therefore mankind always sets itself only such tasks as it can solve; since, looking at the matter more closely, it will always be found that the task itself only arises when the material conditions for its solution already exist or are at least in the process of formation. In broad outlines Asiatic, ancient, feudal and modern bourgeois modes of production can be designated as progressive epochs in the economic formation of society.” (Marx, Preface to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy)

The methodological approach adopted in this passage remains indispensable for understanding how different societies arise and decline. The appreciation that a mode of production cannot expire until the relations of production upon which that social system is based have become fetters on the further development of the productive forces is the basis for the definition of the proletariat’s political programme. Marx and Engels were quite clear that the perspective for the communist revolution was bound up with the global and historic evolution of capitalism itself.

What was less clear for Marx, especially in his earlier writings, was the actual delineation of the “epoch of social revolution” in capitalism’s development; and this lack of clarity was itself an objective product of the fact that the methodology of historical materialism emerged long before that epoch had dawned: Marx issued his first clarion calls to the proletarian revolution not in the period of capitalism’s decline, but of its most spectacular ascent. The imminent proletarian revolution proclaimed in the Communist Manifesto was thrust aside by the continued growth and expansion of capitalist social relations across the whole planet. Marx was definitely wrong to assert at that time that capitalist social relations had entered into a final conflict with the productive forces; although the collision between the two was always a feature of capitalism, the conflict was never irrevocable in the nineteenth century because capital still had vast areas of the globe available for its continued enlarged reproduction, for offsetting the fundamental contradictions which Marx had identified in its process of accumulation: the tendency towards generalised overproduction and the saturation of the market, and the tendency for the rate of profit to decline.

Despite these errors, however, Marx and Engels were still able to base their programme on the recognition that capitalism had yet to exhaust its progressive mission. This recognition was expressed for example in those passages in the Manifesto which talk about the tasks of the proletariat if it were to come to power at that time: the measures advocated are aimed at developing capitalism in the most progressive possible manner, rather than at destroying it root and branch (and thus what was a good example of Marx’s insight has unfortunately been turned into a reactionary state capitalist programme by those who advocate the same measures in the present epoch). More important, the practice of the marxists in the First International was correctly based on the understanding that since capitalism still had a progressive role to play, it was necessary for the working class to support those bourgeois movements which were helping to lay the historic groundwork for socialism (for example the struggles for national unification in Italy, Germany and the USA); similarly, that it was necessary for the workers to continue to fight for reforms since the growth of capitalism made reforms possible, and since the struggle for reforms enabled the workers to constitute themselves into a cohesive and social and political force. These materialist positions were defended against the anarchists’ a-historical demands for the immediate abolition of capitalism and their complete opposition to the struggle for reforms (these positions, though apparently ultra-revolutionary, actually concealed a petty bourgeois desire to ‘abolish’ capitalism and wage labour not by advancing towards their historical supercession but by regressing to the world of the independent small producer).

The Second International made the strategic adaptation to the epoch even more explicitly by elaborating a ‘minimum programme’ of immediately obtainable reforms (trade union recognition, shortening of the working day, etc) alongside a ‘maximum programme’ of socialism to be put into practice when the inevitable historic crisis of capitalism came about.

But for the majority of the chief tacticians and official leaders of the Second International the minimum programme was to become more and more the only real programme of the social democratic parties. Socialism, proletarian revolution, became mere sermonising platitudes to be trotted out on May Day parades, while the energy of the official movement was more and more focussed upon winning a place for social democracy within the capitalist system. Inevitably the ‘revisionist’ wing of the International (Bernstein etc) began to reject the very idea of the necessity for the collapse of capitalism and thus for a revolutionary transition to socialism, and to argue for the possibility of a gradual and peaceful transformation of capitalism into socialism.

These ideologies were nurtured by the extraordinary development of the world capitalist economy in the last part of the 19th century, but this was already the last stage in the ascendant march of the capitalist system: imperialist expansion was beginning to show itself as the precursor to a new and catastrophic phase in the life of bourgeois society, and class antagonisms were becoming increasingly sharp and widespread (mass strikes in America, Germany, and above all Russia). Against the opportunist theorising of Bernstein and co, and the temporising of the social democratic ‘centre’ (Kautsky etc), the left wing within the International - Luxemburg, the Bolsheviks, the Dutch Tribune group etc - defended the fundamental marxist dictum of the necessity for the eventual violent overthrow of capitalism. The clearest statement of this defence was Luxemburg’s Social Reform or Revolution (1898) which, while recognising that capitalism was still ascending by means of “brusque expansionist thrusts” (i.e. imperialism), insisted that the system would inevitably undergo a saturation of the world market, impelling its “crisis of senility” and producing an immediate need for the revolutionary conquest of power by the proletariat. In 1913 Luxemburg published her great theoretical work The Accumulation of Capital, which attempted to analyse the real economic roots of this historic crisis, whose actual arrival was shortly to be announced to humanity in the form of the first imperialist world war.

Basing herself on Marx’s own insistence that the very nature of the wage labour relationship made it impossible for capitalism to realise all the surplus value it extracted within its own social boundaries, Luxemburg concluded that capitalism’s historic decline must commence at the point where there is an exhaustion of the extra-capitalist markets in relation to the amount of surplus value generated by global capitalist production; for Luxemburg, capitalism was “...the first mode of economy which is unable to exist by itself, which needs other economic systems as a medium and a soil. Although it strives to become universal, and indeed on account of this tendency, it must break down – because it is immanently incapable of becoming a universal form of production.” (Accumulation of Capital). In sum, at the point which it dominated the globe, capitalism plunged into a permanent crisis of overproduction.

This conclusion remains to this day the clearest statement about the fundamental origins of the decadence of capitalism, subject of course to the various theoretical elaborations which the experience of another eighty years of decadence has enabled the revolutionary movement to put forward.

The outbreak of imperialist war in 1914 marked a historic turning point both in the history of capitalism and in the workers’ movement. No longer was the problem of the “crisis of senility” a theoretical debate between different wings of the workers’ movement. The understanding that the war marked a new period for capitalism as an historical system required and enabled the genuine marxist currents to draw a class frontier between themselves and those who, in one way or another, became apologists for the imperialist war. It was no accident that the frontier was essentially drown up between the old opportunist wing of social democracy - now openly acting as recruiting sergeants of the bourgeoisie - and the left fractions who had previously held on to the ground principles of the marxist theory of crisis. Luxemburg’s Internationale group, Lenin’s Bolshevik fraction, the left radicals of Bremen - these and others were the ones who held aloft the principles of proletarian internationalism, affirming that the war demonstrated the opening up of that period of “wars and revolutions” predicted by Marx, and calling for the proletariat to oppose the imperialist war with its own revolutionary combat.

Of the revolutionaries who gathered together at the conferences of the internationalist opposition at Zimmerwald and Kienthal, the clearest on the question of the war itself were the Bolsheviks, who together with the German radicals insisted on the slogan “turn the imperialist war into a civil war”, sharply delineating the revolutionary position on the war from that of various centrist and semi-pacifist currents. And as the revolutionary situation in Russia matured, the Bolsheviks’ (and above all Lenin’s) understanding of the tasks of the new period enabled them to attack the mechanistic and nationalistic sophistries of the Mensheviks; while the latter attempted to hold back the tide of revolution by arguing that Russia was ‘too backward’ for socialism, the Bolsheviks pointed out that the world-imperialist nature of the war indicated the ripeness of the world capitalist system for socialist revolution. They thus boldly argued for the seizure of power by the Russian working class as a prelude to the world proletarian revolution.

It was to further the interests of the world revolution that the Bolsheviks were instrumental in the foundation of the Communist International in 1919. The revolutionary parties which rallied round the banner of the Third International were fully aware of the crucial importance of defining the historic period for the elaboration of the communist programme:

“Aims and Tactics

1. The present epoch is the epoch of the disintegration and collapse of the entire capitalist wodd system, which will drag the whole of European civilisation down with it if capitalism with its insoluble contradictions is not destroyed.

2. The task of the proletariat is now to seize the State power immediately. The seizure of State power means the destruction of the State apparatus of the bourgeoisie and the organisation of a new proletarian apparatus of power.”

(From the ‘Invitation to the First Congress of the Communist International’, January 24, 1919)

The proclamations of the First Congress of the CI show a resounding clarity and confidence about the revolutionary tasks of the working class. Their whole emphasis was on the necessity for the immediate conquest of power by the workers, based on the dictatorship of the workers’ councils. There is consequently a clear understanding about the necessity for a break with the old aims and organisations of the pre-war workers’ movement: the social democratic parties which had supported the war effort and then done all they could to crush the post-war revolutionary movements were roundly denounced as agents of capitalism, and cooperation with these organs was rejected; parliamentarism was to a great extent seen as being incapable of serving the interests of the working class; the problem of colonial oppression could, it was stated, only be solved in the context of a world socialist society. These and other positions reflected the ascendant tide of revolution which was then sweeping through the whole world.

But the following congresses of the International, and especially the Third, in 1921, showed a marked deterioration in coherence and revolutionary principles, and this is turn reflected the reflux of the world revolution and the advancing degeneration of the Bolshevik party in the context of the isolation of the Russian Soviet State. As the latter more and more took on the task of managing Russian national capital, and as the Bolshevik party became more and more inextricably fused with the state, the International itself began to function more as an instrument of Russian foreign policy than as the world party of the revolution. The desperate attempts of the Bolsheviks to salvage something from this counter-revolutionary momentum led them to abandon the sharp revolutionary positions of the First Congress and to drift back towards the obsolete tactics of the previous period: parliamentarism, trade unionism, united fronts with the social democratic parties, support for the national liberation struggle in the colonies, and so on. That all these tactics were justified by a revolutionary verbiage could not alter the fact that the change in the historic period could only render such tactics directly counter-revolutionary, no matter what were the intentions of those who resorted to them.

Those who today act within the working class as the extreme left wing of capitalism - Stalinists, Trotskyists, etc - are indeed the true inheritors of these counter-revolutionary policies; what were once the mistakes of the workers’ movement have become the raison d’etre of these bourgeois gangs. Of course Stalinist and Trotskyists may pay lip service to various concepts of capitalist decadence, but this is robbed of any material basis as soon as one considers that throughout their history these currents have considered a large part of the world to be ‘socialist’ or at least ‘non-capitalist’, and therefore historically ascendant and deserving the support of ‘revolutionaries’; even those leftists who consider the Stalinist regimes to be state capitalist have never hesitated to support either them or various third world countries in the innumerable inter-imperialist wars that have ravaged the planet since World War Two. In any case the application of the theory of capitalist decay to the countries these leftists do consider to be capitalist is entirely subordinated to their immediate pragmatic needs as apologists for capital: no amount of talk about state capitalism by the British Socialist Workers Party, for example, has ever prevented it from seeing something progressive in nationalisation and something working class in the Labour or Communist Parties.

At the time of the first great revolutionary wave, the real consequences of a materialist analysis of the new epoch were defined essentially by the left communists who fought against the degeneration of the CI, in particular the German KAPD (Communist Workers Party). The interventions of the KAPC) at the Third Congress of the CI were all concerned with the tasks imposed on revolutionaries by the new period, and almost symbolically represent the fundamental split which was taking place in the workers’ movement of that time.

On the interpretation of the world economic crisis, the KAPD militant, Schwab, insisted on the fundamental difference between the period of capitalism’s ascendancy and its period of decline, and there was already an understanding that this historic decline did not signify a complete stagnation of the productive forces but a continuation of capitalism on a more and more destructive basis. “Capital rebuilds, preserves its profits, but at the expense of its productivity. Capital restores its power by destroying the economy”. Here already there are insights into the waste production, underutilisation of capital, and above all the cycle of crisis, war and reconstruction which are essential features of the decadent phase of capitalist society.

Of course, the left communists’ understanding of the historical moment in which they found themselves was necessarily limited by the fact that they had not long emerged from the old period; and it was further limited by the rapid onset of the counter-revolution which took a heavy toll of their organisations. In this sense, more lasting than the economic analysis put forward by the left communists of the early twenties was their intransigent insistence that the proletariat had to make a complete break with the habits of the old period - in effect, the habits of reformism - and adapt itself to the tasks imposed by the advent of the epoch of social revolution. It was on this materialist basis, and not because of their inherently ‘anarchist’ or ‘infantile’ nature, that the left communists rejected the opportunist tactics taken up by the International. Thus, at the Third Congress of the CI, while recognising that in the ascendant epoch it had indeed been necessary for the working class to organise parliamentary fractions, the KAPD now insisted that “to urge the proletariat to take part in elections in the period of capitalist decadence amounts to nourishing in it the illusion that the crisis can be overcome by parliamentary means.”

The same held true for the question of the unions: the KAPD pointed out that organisations which had been built to defend the working class in an epoch when genuine reforms were still possible were now not only unsuitable as instruments for making the revolution, but had actually become pillars of capitalist order which had to be smashed by the revolutionary working class. This was equally the case for the social democratic parties. The left communists therefore refused to engage in united fronts with what had become part of the state apparatus of the class enemy.

These analyses were not fully formed, of course, and still contained many inconsistencies - for example the KAPD’s illusion that you could replace trade unions with permanent ‘factory organisations’ of a revolutionary character, a position that expressed the influence of anarcho-syndicalism and thus of a form of trade unionism. Other weaknesses were also to play an important role - in particular the disastrous turn towards the theory that the October revolution had been a ‘dual’ or even a purely bourgeois revolution, a theory that completely negated the notion of the global decadence of capitalism. Ironically, but perhaps inevitably, a deeper understanding of the decadence of capitalism only emerged through the horrible experience of the counter-revolution, which reduced the authentic revolutionary currents to a few small groups trying to draw up the lessons of the defeat and to chart the main characteristics of the new period.

In the 1930s, which saw the definitive triumph of the counterrevolution and the emergence of the purest expressions of capitalist decay (Nazism, Stalinism, the war economy, etc), the fraction which developed the most coherent analysis of the epoch was the Italian left in exile around the review Bilan (i.e. ‘balance sheet’ - the balance sheet of the lessons of the revolutionary wave and of its defeat). Bilan’s application of the theory of decadence was central to the clarifications they made regarding many aspects of the communist programme, in particular their complete rejection of national movements anywhere in the world, since in the new period the bourgeoisie could only a reactionary role, both in the colonies and the metropoles.

The clarity attained by the Italian left can be measured by citing an article which appeared in 1934 (‘Crises and Cycles in the Economy of Capitalism in Agony’, Bilan 11, September 1934). The writer, Mitchell, traces many of the deepest trends of capital in its decadent epoch. Developing his argument on the basis of Rosa Luxemburg’s theory of capitalist collapse, Mitchell defined the decay of the capitalist mode of production as having commenced in 1912-14 and as a process in which “capitalist society, because of the acute nature of the contradictions inherent in its mode of production, can no longer fulfil its historic mission: to develop in a continuous and progressive manner the productive forces and the productivity of human labour. The revolt of the productive forces against their private appropriation, once sporadic, has become permanent. Capitalism has entered into its general crisis of decomposition”.

Mitchell points out the essential difference between the cyclical crises of ascendant capitalism and the periods of boom and slump in decadence. Whereas, in the former period, crises were necessary moments in the continued expansion of the world capitalist market, the saturation of the market which brought in the new era means that henceforward the crises of capitalism can only be ‘resolved’ through imperialist wars:

“In its decadent phase, capitalism can only guide the contradictions of its system in one direction: war. Humanity can only escape such an outcome through the proletarian revolution”.

With almost prophetic accuracy, the author goes on to discuss the probable developments of the period ahead:

“Whichever way it turns, whatever means it tries to use to get over the crisis, capitalism is pushed irresistible towards its destiny of war. Where and how it will arise it is impossible to say today. What is important to know and to affirm is that it will explode with a view towards the carving up of Asia and that it will be worldwide”.

Mitchell concludes with a warning against the capitalist alternative of ‘fascism versus democracy’, which was no more than a means to divert the proletariat from its class struggle and mobilise it for capitalist war. But the working class at that time had suffered too many defeats to heed the warnings of the communist fractions, and the fractions themselves had no illusions about the enormity of the defeat the class had been through.

Alongside the Italian left, the council communists (the remnants of the KAPD, the Dutch left and others) stood alone in their defence of internationalist principles in face of the imperialist butchery in Spain and World War Two. But while the council communists were the first to recognise that the ‘workers state’ in the USSR was in fact a form of state capitalism, they were theoretically hamstrung by their increasingly rigid adherence to the notion that October 1917 had been a bourgeois revolution; this prevented them from making the crucial realisation that state capitalism was a universal tendency of decadent capitalism. In America, Paul Mattick did begin to elaborate a theory of permanent crisis based on Grossman’s emphasis of the falling rate of profit as the basic determinant of the crisis, but his methodology led him into a number of aberrations, such as seeing state capitalism as a new mode of production with no imperialist dynamic, and thus, in a sense, progressive. Hence Mattick’s ambivalence on the nature of China, the war in Vietnam, etc.

The elaboration of communist theory after World War Two consequently found its best expression in those who attempted a synthesis of the contribution both of the Italian left and the German and Dutch lefts. The Gauche Communiste de France, with its publication Internationalisme, which split from those elements of the Italian left who were voluntaristically seeking to form a party in a period of reaction, was able to assimilate many of the German left’s insights about the relationship between the party and the workers’ councils, something Bilan had been less clear about. More important still, it formulated a profound analysis of the tendency of decadent capitalism towards statification, and was thus able to grasp the capitalist nature of Russia and its satellites without falling into the error or calling October 1917 a bourgeois revolution.

The GCF disappeared in 1 952 under the tremendous pressure of the counter-revolution that had only been reinforced by the second world war and the victory of ‘democracy’ over fascism. The group had not seen with sufficient clarity that the war had provided world capital with a temporary breathing space:

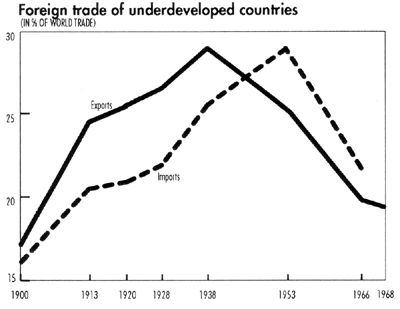

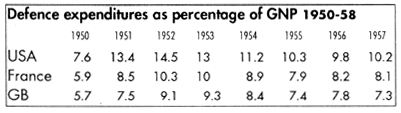

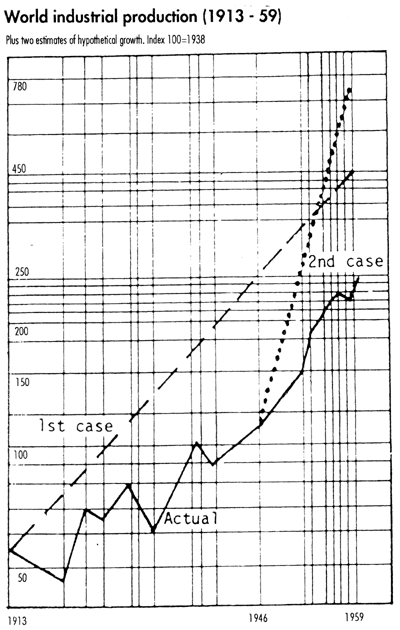

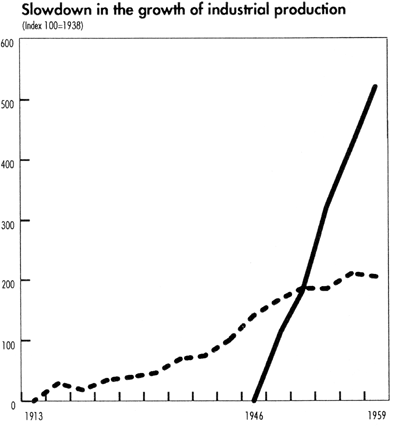

the enormous ‘boom’ of the 50s and 60s was based on the reconstruction of the war-shattered economies of Europe and Japan and a new global economic arrangement characterised by the overwhelming superiority of US imperialism. The startling growth-figures of this period led many sociologists, and even elements in the revolutionary movement, to theorise about a new ‘crisis-free’ capitalism and the ‘embourgeoisiement’ of the working class.

But in Venezuela in the mid-60s a small group was formed around one of the leading elements of the old GCF. This new group, Internacialismo, took the work of the latter a step further by describing the whole cycle of capitalism’s decadence: crisis, war, reconstruction, new crisis ... and, on the basis of this understanding, was able to predict the end of the boom, the opening of a new phase of open crisis, and an international resurgence of struggles by a generation of workers no longer paralysed by the terror and delusion of the counter-revolution.

This perspective was amply confirmed by the massive struggles of May-June 68 in France and the subsequent international wave of class movements, and by the visible deepening of the world economic crisis in the early 70s, which also brought about a sharpening of tensions between the US and Russian imperialist blocs: in sum, humanity was once again confronted with the historic dilemma between world war - which now meant the very destruction of the human race - and world revolution, the creation of a communist society.

The Internacialismo group was instrumental in the formation of Revolution Internationale in France, in the immediate aftermath of the May68 events. The main body of this pamphlet is a series of articles published in the early issues of Revolution Internationale (no.5, old series, and nos. 2, 4 and 5 new series), and itself constitutes a lasting contribution to the theory of decadence. But RI also played a key role in the formation of similar groups in other countries, and which came together in 1975 to found the International Communist Current.

Through the 70s and 80s, the ICC systematically charted the course of the crisis, uncovering the factors that have made it the longest, deepest crisis in capitalisms’ history, a true expression of the death agony of this system. It followed the development of imperialist antagonisms, in particular the offensive of the US bloc after the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, the growing encirclement of the USSR which had the ultimate aim of stripping the latter of its status as a world power. At the same time, the ICC described the uneven but real development of class consciousness through this period, in two further international waves of class struggle(1978-80, 1983-89).

By the end of the 80s, decadent capitalism had reached an important watershed. The continuation of the workers’ struggle was blocking the path to world war, but the proletariat was not yet mature enough to raise the question of revolution; as a result, the exacerbation of the economic crisis was opening up a general process of social decomposition: capitalist society was rotting on its feet, falling apart at the seams. This process produced, and was considerably accelerated by, the sudden collapse of the Russian bloc and the consequent dislocation of its western rival, historical events that definitively opened up the final phase of capitalist decay, the phase of generalised decomposition. In the absence of imperialist blocs, world war has been taken off any foreseeable agenda - but this has in no way mitigated decadent capitalisms’ penchant for militarism and imperialism. On the contrary. As the huge slaughter in the Gulf at the beginning of 1991 showed quite clearly, the very process of decomposition itself, with its train of local and regional conflicts, ‘police actions’ by the great powers, of famines and ecological catastrophes, constitutes no less a threat to the survival of humanity.

The ICC is not the only organisation in the proletarian movement today which holds to the theory of decadence. But it is the only one that has been able to identify and analyse this final

phase. The text ‘Decomposition, final phase of the decadence of capitalism’ was first published in our International Review 62 in the summer of 1990. (See Appendix 2)

As can be seen from this brief historical sketch, the theory of decadence is not an invention of the ICC, but an authentic inheritance from the entire marxist tradition, and it is the indispensable basis to any consistent revolutionary activity. Without an appreciation of the epoch in which it is operating, the programme of a proletarian political organisation can have no material foundation, no orientation for its analyses or its intervention within the class. Without a grasp of the decadence of capitalism, there can be no firm defence of the class frontiers which separate the proletarian from the bourgeois camp. This was demonstrated very painfully by the collapse of the ‘Bordigist’ International Communist Party (Communist Programme) in the early 80s. Although this current claims to be the genuine heir of the Italian left tradition, it rejected the notion of decadence which had been so crucial to the work of the Italian Fraction in the 30s. In particular, it rejected the idea that since the decadence of capitalism was a global phenomenon, there could no longer be any progressive role for ‘national liberation’ movements in the underdeveloped regions. Reiterating Bordiga’s sterile theory about the ‘invariance’ of marxism since 1848, the ICP saw a revolutionary significance in all kinds of national liberation wars - all of which were in fact proxy wars between the two imperialist blocs or between other local and regional imperialist sharks. By the beginning of the 80s the ICP’s support for Palestinian nationalism led a faction within if to pass over into the camp of leftism pure and simple, and this in turn resulted in the implosion of the whole international organisation.

On the other hand, groups which have attempted to defend class positions on such issues as the national or trade union questions while repudiating the notion of decadence have fared little better. The case of the Groupe Communiste Internationaliste is instructive here: having started life with the claim of being ultra-orthodox marxists, this group has, through its fervent rejection of nearly all the theoretical pillars of left communist politics for the last fifty years, drifted more and more into modernism and anarchism. A similar fate has befallen certain councilist groups who have been equally hostile to the notion of decadence. This should be a timely warning for all those who follow the recent fashion of denigrating the theory of decadence and of looking for alternative explanations and periodisations - for example those who misapply the concept of the ‘formal and real domination of capital’, developed by Marx to describe certain important changes that were already well underway within the ascendant period. The ICC has responded to this ‘fashion’ with a series of articles in its International Review this series represents, in fact, a further development of the theory of decadence [1] [2].

The work of understanding the decadence of capitalism continues. But the theory is above all a guide to action, to the intervention of revolutionaries in a historical situation where the very survival of humanity is at stake. This pamphlet begins with a long historical investigation of the decadence of previous class societies (a chapter which has never been published in full in English before),and it enters into number of complex theoretical issues about the characteristics of the capitalist economy in this epoch. But this work has no academic pretensions whatever; its only aim in investigating the reality of present day capitalism is to arm the militant struggle against it.

[A brief not on the Footnotes]

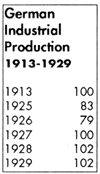

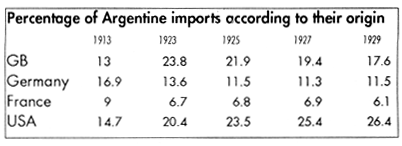

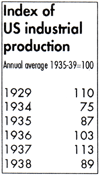

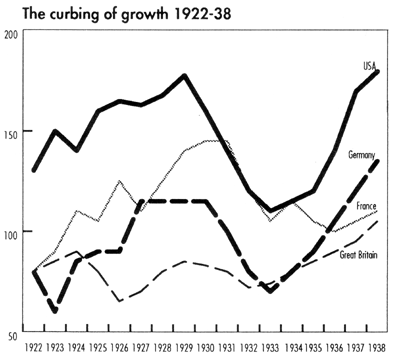

The statistical references contained in the main body of this pamphlet were compiled in the 1970s and are now obviously 'out of date', but only in the sense that the continuing decay of this society has confirmed the tendencies that they illustrate. The ICC's International Review has published regular updates on the 'progress' of the capitalist crisis, and we recommend the reader to refer to these articles.

[1] [3] See issues 48, 49, 50, 54, 55, 56, 58, 60.

1. The rise and fall of class societies

- 4085 reads

In order to define the decadence of capitalism, our approach will be as follows:

- by looking at the main social transformations of the historical process we will draw out the general concept of the decadence of a mode of production; we will then apply this general concept to the specific case of capitalism and try to deduce the political consequences that flow from it.

- and, in doing this, we will, like Marx, consider first “the material transformation of the economic conditions of production”, and secondly “the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophical - in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out”.

The material transformation of the economic conditions

- 3132 reads

The end of primitive communism

The form of social organisation at the beginning of humanity was what Marx

called ‘primitive communism’. Despite important local differences in climatic, historic,

or other elements, the essential traits of primitive societies were the

collective ownership of the means of production (essentially the land) and

collective labour in agriculture and the hunt, the products of which were

shared equally amongst the whole population. The idea that private property is

something inherent in human nature is just a myth popularised by bourgeois

economists since the 18th century; its aim is to present the capitalist system

as the most natural one, the one that best corresponds to human nature.

On the other hand, these

egalitarian relations were not the product of an ideology of brotherhood or the

work of a God anxious to ensure equality between his creatures. It was humanity’s

lack of power faced with a natural environment that could be as hostile as

man’s techniques were feeble, which imposed this need for social cohesion,

forcing men to live in communities that used their means of production in an

egalitarian way. The egalitarian ideology which did exist was a consequence of

these relations and not their cause:

“The mode of production of material life dominates in general the development of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men which determines their existence, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness (Marx, Preface to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy).

In the same way, the disappearance of primitive communism wasn’t the result of ideological changes but of the disappearance of the material conditions which had engendered such a society. If one examines the way in which these egalitarian societies were transformed into societies of exploitation, with the appearance of classes and of private property, it becomes evident that it was the result of progress in the techniques of production.

We will leave aside the cases where this ‘progress’ was the result of the civilising work of European colonial massacres from the end of the 15th century onwards.

In different regions of the globe, and in various local historic conditions, primitive communist societies disintegrated and ceded their place either to the asiatic mode of production or slavery.

Slavery When a community exhausted the fertility of its territory, or when its game had departed, or when its population grew too large in relation to its means of survival, it was obliged to extend or remove its domination to new territories. In regions where the density of population was relatively high - in the Mediterranean for example - such expansion could only be made at the expense of other communities.

In the beginning, wars provoked as a result of these movements could only take the form of gratuitous massacres or cannibalism. Their sole aim was to seize the land of conquered peoples. As long as the level of social productivity only permitted a man to produce just enough for his own individual subsistence, the conqueror had no interest in integrating new mouths into the hungry community. It only became feasible for a conquered people to work for their conquerors, for free and by force, while at the same time producing enough for their own subsistence, when the productivity of labour had reached a certain level [1] [4].

Primitive communist relations were thus abandoned in order to make use of a higher level of productivity in a context of wars and conquests.

The Asiatic mode of production

This badly understood economic system was in general the result of the need of certain communities to face up to the problems posed by nature in certain regions (aridity, floods, monsoons, etc). In such regions communities were very quickly forced to study the cycles of nature and to undertake irrigation works to assure their livelihood. The complexity of these works, the technical knowledge they required, the need for an authority to coordinate them, engendered layers of specialists (priests, versed in the study and observation of nature, were often at the origin of these castes). Charged with a specific task in the service of the community, these specialists - appearing to be the creators of new wealth - tended to constitute themselves into a ruling caste. They progressively appropriated the social surplus at the expense of the collectivity. The development of the productive forces transformed these servants of society into exploiters.

The ‘Asiatic’ mode of production left the communal relations of production unchanged, as basic cells of production. The ruling class only appropriated the surplus created by the work of these communities. But a first transition from primitive communism had been made. The need to apply new techniques of production resulted in the emergence of new relations of production and the abandonment of the old.

The introduction of new techniques of production later on did away with the remnants of egalitarianism in these societies. Thus, for example, the problem of fertilising the land, the necessity to create a more intimate link between the worker and the earth, often led to to an abandonment of the systematic redistribution of plots according to custom or the needs of families. The necessity to ensure a greater continuity in the maintainence of plots, or the weight of fiscal pressures, resulted in the passage from communal to private property. And with the latter, inequality slowly developed, until a part of society had to work on the richest plots for a fraction of the resulting production. Society became entirely stratified, taking the form of a society of serfdom or feudalism.

But whether they gave way to slavery or oriental despotism (and the latter in its turn to serfdom), communist relations caved in under the pressure of the progress of the productive forces, which could no longer adapt to the old framework.

“At a certain stage of their development the productive forces enter into collision with the existing relations of production or with the property relations within which they worked hitherto” (Marx, ibid).

The end of slavery

The result of a development of the productive forces in the particular regions where one people conquered another, slavery allowed the appropriation by one social group of the surplus labour realised by the rest of society. The owners of slaves, as a ruling class avid for profit and privileges, became the motors of the development of the productive forces. However, this development was strictly limited to wars of conquest, mainly taking the form of a growth in the number of slaves and of great works that facilitated the pillage of conquered countries. It was on this basis that ancient Greece and Rome developed their civilisations.

The Roman slave economy - the decadence of which opened the door to feudalism - was founded on the pillage and exploitation of conquered peoples. The latter furnished Rome with its essential means of subsistence (food, tribute and slaves). It often happened that the goods imported were produced under different modes of exploitation, such as the Asiatic mode of production. But the metropole itself subsisted on slavery, the latter being applied above all in wide-scale exploitation (olive groves and stock farming) and in the great works.

These works often served military needs, being used in the exploitation of colonies (roads, viaducts, etc). At the same time they reflected the concern to ensure the luxury of the ruling class.

Thus political power was most often connected with the triumphant military caste. Economic prosperity was therefore closely dependent on the warlike capacities of the metropole.

The great development of Roman civilisation corresponded to its period of victories and conquests. Its zenith was reached when Rome dominated the Mediterranean world and pocketed the profits. In the same way the onset of Roman decadence was marked in the second century AD by the end of this expansion, and in the third century by the Empire’s first defeats (in 251 the Emperor Decius was defeated and killed by the Goths; in 260 the Emperor Valerian was taken prisoner and humiliated by the king of Persia. In the course of the third century revolts in the colonies broke out simultaneously for the first time).

The difficulties of maintaining such a gigantic empire with the limited technical means available at that time explains in part the end of Rome’s expansion. But above all it was the gap between the economic productivity of Roman slavery and that of its colonies (which often developed a superior productivity under the Asiatic mode) which ensured that the revolts in the colonies would ultimately be successful.

Slave relations of production were characterised by low labour productivity. In the conditions of the epoch, a growth of productivity required the improvement of methods for working the earth - the utilisation of the plough, the development of fertilisation and the creation of an intimate link between the worker and the soil, providing the worker with a motive for using these techniques of production. But such progress demanded the abandonment of slavery, in which the worker is maintained by his master whatever his productivity, and in which only the fear of punishment forces the slave to produce, so that he works with the least care possible.

Slavery was only profitable as a means of exploiting conquered peoples. Once these conquests stopped or diminished, once the sources of booty, tributes and slaves dried up (in turn leading to a rise in the value of slaves), slavery transformed itself into an unprofitable system, a fetter on the development of production.

The need to pass on to new productive relations led, in the metropole, to the appearance of feudal types of exploitation, in which the great proprietors ceded much land to free families in exchange for a part of their produce. But the surpassing of slavery also involved an attack on the privileges of the ruling class. The ‘collision’ between the development of the productive forces of society, and the relations of production that had existed until then, precipitated Rome into its phase of decadence.

The development of production slowed down or stopped: “They (the wealthy Romans) ‘gleaned’ the products of the mines and undermine the soil, allowing pastures or forests to disappear in semi-arid regions. Manpower was exploited without a break, stimulating discontent and apathy in work. They even forbade the application of new methods, and neglected irrigation works and drainage in regions where they were essential....War, epidemics and starvation reduced the population of the Empire by a third. The death rate was perhaps even higher in Italy itself during the course of the third century" (Shepard B Clough, Grandeur and Decadence of Civilisations, Editions Payot p140)

Feudalism

Following slavery or the Asiatic mode of production, the feudal system allowed a new scope to the productive forces of society for centuries.

In autarkic feudal relations, work on the soil attained unequalled levels of improvement (amelioration of ploughing, shoeing of work animals, of harnessing - at the head or neck instead of the belly - development of irrigation and of fertilisation, etc). Furthermore, and above all, the perfecting of agricultural labour was accompanied by a considerable development of artisan work. The latter existed as a simple appendage of the agricultural economy: supplying instruments of labour and certain items of consumption, essentially for the ruling class (mainly clothing and weapons).

The craftsman benefited from the growth of resources available to the noble class thanks to the development of agricultural productivity. This last factor figured all the more as the noble class wasn’t engaged in accumulation - the particular character of the bourgeoisie - but used all its profit for personal consumption.

But from the twelfth century on feudalism had begun to reach the limits of the possibilities for extending cultivatable surfaces.

“We have enough indices of the lack of land at the end of the thirteenth century to suggest that the extension of cultivatable surfaces was inferior to the national growth of population; and with the exception of certain places, it was probably insufficient to compensate for the tendency for labour productivity to fall. The pressure from land shortages after 1200 in Holland, Saxony, Rhineland, Bavaria and the Tyrol was one of the factors which gave birth to the migrations towards the east, and we can say that at the end of the fourteenth century the limits of acquiring soil from forest land were already reached in the north east of Germany and Bohemia” (Maurice Dobb, Studies in the Development of Capitalism, p 59).

“The contemporaries of St Louis, and in certain regions those of Philippe de Bel, saw the development of the soil pushed to its limits. The most audacious reclamations were attempted because it was always necessary to feed more mouths and because, not knowing any other way of augmenting the yield, the space cultivated always had to grow. Permanent marshes and wasteland seemed to disappear. Woods shrank. The marshes and fens of the English coast were drained, cleaned, exploited to the limit of what was technically possible...” (J Favrier, De Marco Polo a Christopher Columbus, p 125)

From then society could only break out of its impasse through a new development in the productivity of labour. Now the latter had more or less attained its extreme limits in the context of family artisan production. Only the passage from individual labour to the labour of a number of associated workers, to a more complex division of labour and the utilisation of more complex means of production could in these conditions permit the necessary growth of productivity.

This was possible because the development of artisan work under feudalism also contributed to a revival of the towns, which were the basis needed for more collective forms of labour.

But, fundamentally, the feudal framework was the negation of the conditions which could allow for a real development of this economic form:

- feudalism was founded on the life-long attachment of men to their means of production as well as to their lord, whereas manufacturing demanded great mobility of labour power, and thus a separation of the worker from the means of production;

- feudalism was a system of local power, of autarky, of the closed fief, with innumerable tolls to pay on the passage of commodities through different feudal estates. The manufacturer, by contrast, needed a mobility of raw materials, of commodities in general, so that he could concentrate in one place of production the products from a thousand different places, and ensure the freest possible distribution of his own commodities;

- finally, manufacturing production must base itself on the accumulation and the concentration of profits in order to obtain, replace and then expand the machinery which allows for production based on the division of labour. It requires therefore a spirit of success through work and the right to accumulate the rewards of the latter. Feudal privileges, on the other hand, were based first on the capacity to make war, and after that solely on heredity.

At the level of the capacity to work, the lord was equal or inferior to the serf. Hence feudal society’s contempt for work, which was seen as a form of debasement.

The feudal lord made it a matter of honour to display his ability to consume his entire revenue. The feudal economy ignored and condemned accumulation aimed at the growth of production, an attitude which barred the way to the development of manufacture.

“We can consider that the beginning of the fourteenth century marked the end of the mediaeval economy’s period of expansion. Up till then, progress had been continual in all spheres ... But by the first years of the fourteenth century, all this came to an end. Although there wasn’t a regression, there was no advance either. Europe was, as it were, resting on its laurels: there was stability on the economic front...the proof that the previous economic thrust had been interrupted was the fact that foreign trade ceased to expand...In Flanders and Bravante, the drapery industry maintained itself without increasing its traditional prosperity until around the middle of the century, then it began to go rapidly downward. In Italy, most of the great banks which had dominated the money markets for so long fell into a series of reverberating bankruptcies ... the decline of the fairs of Champagne date from the first years of the century. This was also the time when the population stopped growing, and this constituted the most important symptom of the state of a stabilised society which had reached the final point of its evolution.”

(H. Pirenne, Histoire economique et sociale du Moyen Age, PUF, p 158).

Just as in slavery, the decadence of feudalism meant famines, since the growth of the productive forces was far inferior to the growth in population. Famines were then followed by epidemics, which spread rapidly because of the poor nutrition of the population. Thus from 1315 to 1317 a terrible famine desolated all of Europe, followed thirty years later by the Black Death, which between 1347 and 1350 wiped out one third of Europe’s population.

“It’s true that it was precisely then that countries which had been outside the main areas of economic development, like Poland and especially Bohemia, began to participate in it more fully. But their belated awakening didn’t result in any important consequences for the western world as a whole. It was thus clear that society was entering a period when more was being conserved than produced, and when social discontent testified to both the desire and the incapacity to improve a situation which no longer corresponded to men’s needs.” (Pirenne, op cit, p 158)

Feudal decadence began in the fourteenth century, continuing until the overthrow of its last juridical traces by the bourgeois revolutions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England and France. But from the fourteenth century new relations of production were beginning to dominate society: capitalism. Developing out of a struggle against the old feudal fetters, it was the main beneficiary from the morass of the fourteenth century, and was to allow a great revival of economic life.

[1] [5] The development of wars was an active factor in the abandonment of egalitarian social relations: conditions of semi-permanent warfare demanded the emergence of a layer of specialised warriors who tended to appear as the suppliers of wealth to the collectivity and who thus began to establish hierarchical relations within the community, with the rest of the community ensuring their upkeep. But in itself this factor only became important when the growth of productivity permitted the passage to slavery.

The general conception of decadence

- 2281 reads

The development of the productive forces has two aspects:

1. The growth of the number of workers incorporated into production at a given level of productivity;

2. The development of labour productivity amongst a given number of workers.

In a system in full expansion, one can see a combination of both. A system in crisis is a system which has reached it limits in both aspects at the same time.

We can speak of an ‘external limit’ to the expansion of a system (its incapacity to enlarge its field of action) and of an ‘internal limit’ (the incapacity to go beyond a certain level of productivity). Consider the case of the end of slavery, of the Roman Empire. The external limit was constituted by the material impossibility of enlarging the extent of the Empire. The internal limit was the impossibility of raising the productivity of the slaves without overthrowing the social system itself, without eliminating their status as slaves. For feudalism it was the end of land reclamation, the incapacity to find new arable lands, which acted as the external limit, while the internal limit was its inability to raise the productivity of the serfs, or of the individual artisan, without transforming them into proletarians, without introducing labour associated by capital: that is, without the overthrow of the feudal economic order.

The approach of these two types of limits are dialectically linked: Rome could not expand its empire indefinitely because of the limits of production; inversely, the more difficult it was to expand, the more it was obliged to develop its productivity, thus pushing it more rapidly towards its extreme limits. Likewise feudal reclamations were limited by the level of feudal techniques, while the scarcity of land encouraged more ingenuity in productive activities carried out in the towns and the countryside. This in turn pushed feudal productivity to the border of capitalism.

In the final analysis it is the limits on the level of productivity within the old society which lead it into the morass. It is this productivity which is the true measure of the level of development of the productive forces; it’s the quantitative expression of a certain combination of human labour and means of production, of living and dead labour [1] [6].

To each stage of development of the productive forces, that is, at each overall level of productivity, there corresponds a certain type of relations of production. When this productivity approaches its last possible limits within the system which corresponded to it, and if the system is not overthrown, society enters into a phase of economic decadence. Then there is a snowball effect: the first consequences of the crisis transform themselves into factors accelerating the crisis. For example, at the end of Rome as well as in the decline of feudalism, the drop in revenues of the ruling class pushed the latter to reinforce the exploitation of the workforce to the point of exhaustion. The result in both cases was the growing apathy and discontent of the labourers, which only accelerated the decline in revenues.

Likewise the impossibility of incorporating new labourers into production forced society to support inactive strata who constituted yet another drain on revenues.

A similar phenomenon was the galloping devaluation of money at the end of the Empire as well as at the end of the Middle Ages: “Rome had hoped to cover its governmental expenses by increasing taxation, but when the proceeds proved insufficient it was necessary to resort to inflation (at the end of the Second Empire). This first expedient had to be repeated from time to time in the course of the third century, certain monies being devalued to 2 percent of their face value. The monetary unity of the Empire was destroyed; each town and each province issuing its own money”( Shepard B Clough, op cit, p 141).

And at the end of the Middle Ages: “In a world where the mass of money became insufficient, the wage-bill (of soldiers used for protection against robbery or in wars - ICC note) increased the need for precious metals; thus the temptation to overvalue the cash in circulation. The rulers used their authority to diminish the weight of coins, so that a coin valued at 2 sous henceforth contained less pure silver and more lead, but was now worth 3 sous. This was inflation!”( J Favier, op cit, p 127).

Parallel to these economic consequences the crisis causes a series of social convulsions which in their turn impede an already enfeebled economic life. The development of productivity systematically conflicts with existing social structures, rendering impossible any new development of the productive forces. the need to go beyond the old society is put on the agenda.

“A society never expires before all the productive forces contained within it have been developed” (Marx, op cit).

In fact it should be noted that no system has developed ALL the productive forces - in the proper sense of the term - which it may contain in theory.

On the one hand, the economic consequences that we have seen and the series of social catastrophes which the first great economic difficulties cause are so many fetters preventing the system really attaining its absolute limits. We must bear in mind that an economic system is the ensemble of relations of production that men have been led to establish, independently of their will and in accord with the level of productive forces, to PROVIDE FOR THEIR ECONOMIC NEEDS. Before the last instrument of production has seen the light of day, if production has started to grow less quickly than the needs of the population, the system loses its historic reason for existence, and everything in society tends to push against its confines.

On the other hand, under the pressure of the productive forces, the economic foundations of the new society begin to develop within the old. This only applies to past societies where the class which overthrew them was never the exploited class. Feudalism grew up within the Roman empire. The first feudal plantations in Rome were often headed by old members of the municipal senate put to flight by a state which made them responsible for the collection of taxes.

Likewise, at the end of feudalism, members of the nobility became businessmen, and in the towns - often in struggle against local lords - developed the first manufactories, prefiguring capitalism.

These first ‘centres of the future system’ (great Roman plantations, bourgeois towns) were mostly born as the result of the decomposition of the old system. They attracted all kinds of elements trying to escape the system. But from being the results of decadence, these centres quickly transformed themselves into factors that hastened it along.

Material conditions permit the passage to a new type of society, whose premises already exist within the old society, and their pressure is sufficient to begin the foundation of a new system.

“New relations of production have never been put into place before the material conditions of their existence has been discovered within the old society” (Marx, op cit).

It is not enough that production approaches its final limits within the old society. It is also necessary that the means to go beyond the latter already exist or are in the process of formation. When these two conditions are historically realised, society’s adoption of new relations of production is on the agenda. But the resistance of the old society (of the old privileged class, the inertia of customs and habits, ideologies, religion etc), and the gap that may exist between the realisation of these two conditions, means that such transformations do not take place in a progressive, linear manner, but through a series of regressions, catastrophes, and qualitative leaps.

The phase of decadence of a system is that period in which such a historic leap has not been made; it is the expression of a growing contradiction between the productive forces and the relations of production; it is the sickness of a body whose clothes have become too tight.

[1] [7] It is this relation which under capitalism will be partially expressed by the organic composition of capital: c¼v constant capital over variable capital.

The overturning of the superstructures

- 2371 reads

When the economy trembles, the whole superstructure that relies on it enters into crisis and decomposition. The manifestations of this decomposition are the characteristic elements of the decadence of a system.

Beginning as consequences of a system, they then most often become accelerating factors in the process of decline. Many a bourgeois historian, having seen the latter phenomenon, deduces from it that the superstructural elements are actually the main causes for the ending of a civilisation.

In this examination of superstructural elements, we will look at four phenomena which can be found both in the decadence of slavery and the decadence of feudalism. We will see that these are no historical coincidences, but definite symptoms of the decadence of a system.

These phenomena are:

1) the decomposition of the ideological forms that reigned in the old society;

2) the development of wars between factions of the ruling class;

3) the intensification and development of class struggles;

4) the strengthening of the state apparatus.

1) The decomposition of ideological forms

In a society divided into classes, the dominant ideology is necessarily the ideology of the dominant class. The scope for the enrichment and development of its ideological forms depends on the real capacity of the ruling class to persuade the whole of society to accept its rule. A society is only prepared to accept a given ideology as long as the economic system it is based on corresponds to that society’s needs. The more an economic system ensures prosperity and security, the more the human beings who live by it will identify with the ideas that justify it. In conditions of expansion, the injustices inherent in the economic relations can appear as no more than ‘necessary evils’; the belief that everyone can benefit from the system permits the development of democratic ideologies, above all within that part of society which benefits from it the most - the ruling class (the regime of the Republic corresponded to the most flourishing period of the Roman economy; in expanding feudalism, the king was merely a suzerain, elected as the first among equals).

Law itself is relatively little developed because the system corresponds sufficiently to the objective needs of society for most problems to be resolved by allowing things to take their course.

The sciences tend to develop, philosophy leans towards rationalism, towards optimism and confidence in mankind. Since the ugly side that belongs to any exploitative society is relatively well hidden by the state of prosperity, ideologies are less encumbered by the need to hide reality and justify the unjustifiable. Art itself tends to reflect this optimism and usually has its best moments in the periods of economic development (what is referred to as the ‘golden age’ of Roman art corresponds to the main period of the growth of the Empire, for example; similarly in the prosperous days of the 11th and 12th centuries, feudalism went through an immense artistic and intellectual renewal.

But when the relations of production turn into a straitjacket for the life of society, all the ideological forms corresponding to the existing order lose their roots, are emptied of content, and are openly contradicted by reality. In the decadence of the Roman empire, the ideology of the political power took on an increasingly supernatural and dictatorial form. In the same way feudal decadence was accompanied by the reinforcement of the idea of the divine origins of the monarchy and the privileges of the nobility, which were being severely battered by the mercantile relations being introduced by the bourgeoisie.

Philosophies and religions express a growing pessimism; confidence in mankind gives way to a fatalism and obscurantism (eg the development of Stoicism then of Neoplatonism in the Lower Roman Empire: the first talked about the elevation of man through pain, the second denied the capacity of man to grasp the problems of the world through reason).

The end of the Middle Ages saw the same phenomenon:

“The period of stagnation saw the rise of mysticism in all its forms. The intellectual form with the ‘Treatise on the Art of Dying’, and above all, ‘The Imitation of Jesus Christ’. The emotional form with the great expressions of popular piety exacerbated by the influence of the uncontrolled elements of the mendicant clergy: the ‘flagellants’ wandered the countryside, lacerating their bodies with whips in village squares in order to strike at human sensibility and call Christians to repent. These manifestations gave rise to imagery of often dubious taste, as with the fountains of blood that symbolised the redeemer. Very rapidly the movement lurched towards hysteria and the ecclesiastical hierarchy had to intervene against the troublemakers, in order to prevent their preaching from increasing the number of vagabonds...Macabre art developed... the sacred text most favoured by the more thoughtful minds was the Apocalypse.” (Favier, op cit, p 152f).

All this reflected the growing gap between the relations reigning in society and the ideas about them which men had hitherto held to.

The only ideologies which could really develop in these periods was law, on the one hand, and, on the other, the ideologies which announced the new society.

In a society divided into classes law can only be the expression of the interests and will of the ruling class. It is the totality of rules that permit the proper functioning of the system of exploitation. Law goes through a period of growth at the beginning of the life of a social system, when the new ‘rules of the game’ are being established; but also at the end of a system, when reality rends the system ever more unpopular and inappropriate, and the ‘will’ of the ruling class becomes the most important thing keeping the old relations going. Law then represents the necessity to reinforce the oppressive framework necessary for the survival of a system that has now become obsolete. This is why law developed both in Roman decadence and during the decline of feudalism (Diocletian, the greatest Emperor of the Lower Empire, was also the one who produced the greatest number of edicts and decrees. Similarly from the 13th century onwards, the first collections of customary laws began to appear).

Parallel to this phenomenon there appear ideas advocating new types of social relations; they take on critical, rebellious and finally revolutionary forms. They are the justification for the new society. This phenomenon was particularly evident from the 15th century on in western Europe. Protestantism, particularly the form preached by Calvin, was a religion which, as opposed to Catholicism, allowed for the lending of money on interest (crucial for the development of capital); which taught spiritual elevation though work and glorified the successful man (thus opposing the ‘divine’ origins of the privileges of the nobility and justifying the new situation of the ‘parvenu’ bourgeois businessman); which put in question the supernatural character of the Catholic church (the main feudal landholder) and advocated the interpretation of the Bible by man without any intermediary. This new religion was an ideological element which announced and hastened the rise of capitalism.

Similarly, the development of bourgeois rationalism, whose ultimate expression was in the philosophers and economists of the 17th and 18th centuries, expressed the revolutionary element of the conflict into which society had entered.

Decomposition of the old ruling ideology, the development of the ideology of the new society, obscurantism against rationalism, pessimism against optimism, coercive law against constructive law, here, as Marx said, we find “the juridical, political, religious, artistic, philosophic, in short, the ideological forms through which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out”.

2) The development of wars between factions of the ruling class

The prosperity of a system of exploitation allows there to be relative harmony between the exploiters, and thus there can be ‘democratic’ relations between them. When the system ceases to be viable, when profits diminish, harmony gives way to wars between the profiteers. Thus, in parallel to the brigandry that characterised the end of the Roman Empire and the Middle Age, there was a proliferation of wars between factions of the ruling class.

In Rome from the second century onwards there was a series of wars fought by knights, bureaucrats and army chiefs and senators and patricians:

“Between the years 235 and 285, out of the 26 Emperors who succeeded each other to the throne, only two died a natural death, and at one moment there were up to 30 claimants to the throne” ( SB Clough, op cit, p 142).

At the end of the Middle Ages wars between nobles took on such proportions that the western kings were forced to forbid them, and Louis IX went as far as to forbid the bearing of arms. The Hundred Years War was a phenomenon of this type.

When the ruling class can no longer escape the contradictions of its system and sees its profits declining irreversibly, the most immediate solution is for each faction to grab hold of the wealth of their rivals; or at least to seize control of the conditions of production which allow this wealth to be produced (for example, the fiefs of the feudal epoch).

3) The intensification of class struggles

In the decadence of a system there are three phenomena which make the intensification of class struggles one of the main characteristics of these periods of decline:

- the development of poverty: we have already shown that the end of slavery and feudalism were regularly marked by famines, epidemics and the generalisation of poverty. We have seen what consequences this had within the privileged classes, but it was obviously the oppressed classes which suffered these scourges most intensely; this provoked them into more and more frequent riots and revolts;

- the strengthening of exploitation: we have also shown how in a system in decadence, productivity can less and less be increased by technical means, so that the ruling classes are increasingly tempted to palliate this through the super-exploitation of labour. The latter is used up to the point of exhaustion. There is a whole growth in punishments for those who fail to do enough work...

Added to the poverty and suffering they are already enduring, this last factor can only accentuate the tendency towards the generalisation of struggles between the exploited and the exploiters. The reactions of the toiling classes are so violent, and in the end so damaging to the goal of increasing productivity, that at both in the end of the Roman Empire and in the late Middle Ages, there is a tendency to replace punishments by measures aimed at giving the labourers an ‘interest’ in their work (the emancipation of the slaves and the serfs) [1] [8]

- the struggle of the class that bears within it the seeds of a new society: in parallel to the revolts of the exploited, there is a development of the struggle of a new class (the great ‘feudal’ landowners at the end of the Roman Empire, the bourgeoisie at the end of feudalism), which begins to establish the bases of its own system of exploitation, which sap the bases of the old system. These classes are thus led to wage a permanent combat against the old privileged class.

During the course of this struggle, the revolts of the labouring classes always provides the force that these new classes themselves lack in their effort to supplant the old structures, now become completely reactionary (it’s only in the proletarian revolution that the class that carries within itself the germs of the new society is at the same time the exploited class).

All these elements explain the fact that the decadence of a society necessarily leads to a decisive renewal of class struggles. Thus, in the Lower Roman Empire:

“the situation created by the deficiencies in production, an ever-increasing taxation, the devaluation of the currency and the growing independence of the large landowners had the consequence of further accentuating the political and social disorganisation and of leading to the disappearance of the principles that regulated relations between men...impoverished landowners, ruined merchants, labourers from the towns, colons, slaves, rioters and deserters from the army resorted to pillage in Gaul, Sicily, Italy, North Africa and Asia Minor. In 235 a wave of brigandry swept through the whole of northern Italy. In 238 civil war reigned in North Africa. In 268 the colons of Gaul attacked numerous towns, and in 269 a slave revolt broke out in Sicily” (Clough, op cit, p 142).

“The breadth of the social movements affecting the Latin west in the 5th century is impressive. They shook all regions and especially Brittany, western Gaul, the north of Spain and Africa...” (Lucien Musset, Les Invasions, p 226).

It was the same at the end of the Middle Ages: