ICConline - 2016

- 1709 reads

January 2016

- 1258 reads

British bombs will increase the chaos in the Middle East

- 1556 reads

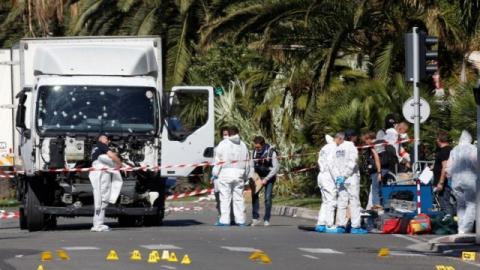

The brutal slaying of 130 people in Paris on 13 November 2015 was used to justify the stepping up of British imperialism’s involvement in the living hell that is Syria. Even as the massacre was taking place the faction of the ruling class in Britain that for some years has wanted to escalate military action against Islamic State was calling for the overturning of the 2013 parliamentary vote against the extension of British involvement in this campaign from Iraq to Syria. This cold-blooded manipulation of the revulsion at the Paris slaughter was whipped up into an almost hysterical campaign which culminated in Labour’s Hilary Benn’s speech comparing the fight against the “fascists” of IS to the Second World War. The subsequent vote to bomb IS in Syria was presented as Britain once again taking up its rightful place in the world as a moral force.

In reality, British imperialism’s increased military role in Syria will only pour more oil onto the barbaric fire of militarism, sectarianism and banditry that is consuming Syria and Iraq and threatening the whole region.

This decision also does not however resolve the deep divisions within the British bourgeoisie over the best policy to pursue in order to defend the national interest. Only weeks before the vote was taken the House of Commons’ Foreign Affairs Committee issued a report that contained the following warning: “we believe that there should be no extension of British military action into Syria unless there is a coherent international strategy that has a realistic chance of defeating ISIL and of ending the civil war in Syria. In the absence of such a strategy, taking action to meet the desire to do something is still incoherent....We consider that the focus on the extension of airstrikes against ISIL in Syria is a distraction from the much bigger and more important task of finding a resolution to the conflict in Syria and thereby removing one of the main facilitators of ISIL’s rise.”(‘The extension of offensive British operations in Syria’, 29 October 2015)

There may have been some pretence of pursuing such a strategy at meetings of world and regional leaders following the Paris killings, but the reality is that the war in Syria is a cauldron of tensions between the different imperialist powers: “The fact that there are few reliable counterparts on the ground is a reflection of the extraordinary complexity of the situation on the ground in Syria. Our witnesses described a chaotic and complicated political and military scene. After over four years of civil war, there are thousands of fighting forces in various coalitions and umbrella organisations, with unclear aspirations and shifting alliances. The complex nature of the situation makes it hard to guess the consequences of tackling just ISIL, or to predict what group would take their territory if they were defeated....The situation in Syria is complicated still further by the multiple international actors involved on the ground, to the extent that many observers now consider the civil war a proxy war as much as an internal conflict. These include Russia and Iran (on the Assad side), Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, and the US (on the sides of various different parts of the opposition), creating what one witness called a ‘multi-layered conflict’. The much more substantial Russian intervention on the side of the Assad regime that started at the end of September 2015 has complicated even further any proposed action in Syria by the UK”(op cit). Clearly the committee was not going to include Britain itself as part of this multi-layered conflict, but it was already deeply involved, whether through direct military action against IS across the non-existent border with Iraq, or through less direct support (money, weapons, military advice, etc) to rebel forces inside Syria itself. The faction that opposed direct military involvement in Syria presented itself as a force for humanitarian concern, but their actual concern was that such involvement would not serve the national interest, and would undermine the British bourgeoisie’s ability to act as a mediator and to use its diplomatic power. This was summed up by the Foreign Affairs committee’s report: “Several of our witnesses suggested that by participating in military action against ISIL in Syria, the UK would actually compromise its diplomatic capability and its capacity to put pressure on its national and international partners to create a route to a solution to the inter-related problems of ISIL and the Syrian civil war”.

Britain’s dilemma

This division within the British ruling class over such a fundamental question as the national interest is an expression of the dilemma that it has been confronted with since the end of the Cold War: how to best pursue the national interest in the absence of clearly defined blocs? There is a general agreement on the need to maintain its independence through playing its special relationship with the US against its relations with European states. The problem has been how to do this. Just how problematic is clearly expressed by the present situation in Syria.

Syria’s descent into chaos cannot be separated from the hardly less messy situation in Iraq, which has been a poisonous thorn in the side of British imperialism ever since the invasion of 2003. Britain’s involvement in the Iraq debacle was a profound blow for the British ruling class. The loyal following of US policy towards Iraq and Afghanistan failed to secure British imperialism’s international position either though its military power or its diplomatic ability to play the US and the EU at the same time. Its pretense to moral authority in bringing about a ‘democratic transformation’ of these countries was exposed as a fraud. Finally, it was reduced to scurrying away, with its tail between its legs, from the chaos it had helped to create. The Cameron government has tried to overcome the trauma of the Blair years, but as the 2013 vote showed, an important part of the ruling class was not willing to risk another ‘foreign adventure’, particularly one in the chaos of Syria. This has, as we said at the time, left British imperialism looking weak, unable to overcome its own divisions[1]. The recent vote does take steps toward overcoming this division, at least publicly, but the ruling class is still faced with the question of how its involvement will play out.

There is already cynicism about the role of the British military, which has only, to date, carried out 11 bombing raids since the vote, as well as a real fear of mission creep as British special forces are deployed to support and train rebel forces. The so-called ‘moderate’ forces supported by Britain are in reality fundamentalist warlords and gangsters, as the above report admits.

As for boasting about precision bombing and how concern for civilians is so important to Britain ... 6 of the missions flown have been against oil plants that are manned by workers. Oil workers, and oil truck drivers (over 100 oil trucks were destroyed by the US in two days) are clearly not considered civilians by the British ruling class. But in any case as General Tommy Franks of the US army said early in the Iraq war, “we don’t do body counts”; and any reports of civilian deaths from within IS held areas will be brushed aside as accidents or IS propaganda.

British involvement in other wars

The problems faced by British imperialism in Syria are only part of the growing imperialist chaos in the Middle East and North Africa.

There is the continuing sore of the collapse of Libya into a series of warring regions, cities and even neighbourhoods, including areas controlled by IS, following the ‘liberation’ of Libya by the British and French in 2011. The sight of the British ambassador fleeing Tripoli before advancing rebel factions was hardly a good advertisement for British imperialism as potential backing for any army or clan trying to seize state control.

The involvement of British imperialism in the war waged by a coalition of Saudi Arabia, Gulf States and Pakistan in Yemen against the Iran-backed Houthi rebels is another difficulty. This proxy war between two regional powers, a war also taking place in Syria, threatens to spiral out of control as their struggle to control Yemen becomes increasingly intractable. Saudi imperialism is particularly concerned about the agreement between Iran and the US over nuclear weapons, and also the role of Iran in Syria (where Saudi Arabia was initially one of the main backers of IS and other Islamist warlords). Britain is supplying weapons and military advisors[2] to the anti-Houthi coalition and has direct links with the military of all these countries, many of whose officer corps received training in Britain. The Saudis’ recent public execution of 47 Shia Muslims has further sharpened regional tensions. It highlighted the hollow nature of British imperialism’s claim to be fighting extremism whilst at the same time arming and making very nice profits from the Saudi state which is the main promoter of Wahabism, the ideological foundations of IS and jihadism.

The implication of British imperialism in the growing fragmentation of the Middle East has deep historical roots. It was the dividing up of the old Ottoman Empire between British and French imperialism, following World War I, that set up the artificial system of states that make up the Middle East (see the other article on the Middle East in this issue). Britain also has a history of promoting fundamentalism in order to maintain its rule and role in the region. The emergence of the Saudis as the rulers of present day Saudi Arabia, along with their fundamentalist ideology, was promoted by the British as well as the Americans. Western support for fundamentalist regimes and groups in the period of the Cold War included, to cite only two examples, the Islamic Brotherhood in Egypt against Nasser, and the promotion and arming of jihadist groups in Afghanistan and beyond to fight the Russians in Afghanistan. Thus today British imperialism is faced by the challenge of trying to assert itself in the growing chaos of the Middle East, a chaos it has done much to cause.

Phil 16/1/16

Geographical:

Rubric:

Capitalism is bankrupt, communism is a necessity

- 2259 reads

“The City of London’s most vocal ‘bear’ has warned that the world is heading for a financial crisis as severe as the crash of 2008-09 that could prompt the collapse of the eurozone.

Albert Edwards, strategist at the bank Société Générale, said the west was about to be hit by a wave of deflation from emerging market economies and that central banks were unaware of the disaster about to hit them. His comments came as analysts at Royal Bank of Scotland urged investors to “sell everything” ahead of an imminent stock market crash”[1].

Of course we should take such predictions with a pinch of salt. Even though the financial crisis of 2008 was very serious indeed, there was also an element of exaggeration in the propaganda of the ruling class at the time. The collapse of Lehman Brothers, which acted as a kind of trigger for the crisis, was to some extent allowed to happen by the US government as an example to others, and the message of “we’re on the brink” certainly helped to ram home austerity measures as the “only alternative”. We shouldn’t underestimate the capacity of the bourgeoisie, with the whole apparatus of the state and the financial system at its disposal, to use all kinds of tricks and manipulations to prevent the economic crisis running out of control – that’s an unforgettable lesson it learned from the great crash of 1929.

But none of this means that the economic crisis is something superficial, just part of the regular business cycle with its ups and its downs. The current economic difficulties have very deep roots indeed – going back at least a hundred years, and ultimately reaching the very basis of capitalist production, the wage labour system and the contradictions that are inherent in capitalist accumulation. We may not be in a “final” economic crisis right now, but in a more long term sense we are at the final stage of capitalism’s obsolescence as a social system.

The real problems facing the system can be gauged by the fact that the current stock market jitters were to a considerable extent provoked by the slowdown of the Chinese economy, which has played such a key role as a market and a target for investment for “developed” and “developing” countries alike. For years now, western economies have been displacing production and capital to fuel the Chinese “miracle”, which could then send out a stream of cheap commodities back to the west. The result? China’s economy has been “overheating”, or to use marxist terms, it is facing the same crisis of overproduction, the same falling profit rates that have plagued the central countries throughout this century, and in particular since the end of the post-war boom in the 1960s.

All units of capital, whether individual companies or major national economies, are driven to accumulate, to expand, or risk annihilation by rival companies and national economies. But the more they produce, the more they tend to outstrip the available market, which is ultimately limited by the restricted buying power of the masses; the more they invest in new technologies to boost production, the less living labour – the only source of surplus value – is incorporated into what they produce.

The penetration into new areas of the globe, the integration of previous forms of production into the orbit of capitalism, has long provided a lifeline to capitalism, a means of postponing its in-built tendency towards breakdown. The Chinese economy, for example, though already capitalist under Mao, had at its disposal a vast mass of peasant labour available to be transformed into wage labour, considerably reducing the costs of labour power on a global scale. This process now is reaching its limits and China’s slowdown - along with that of other BRICS like Brazil and Russia – is indeed a sign that the temporary solutions found by capitalism over the past few decades are also reaching their limits. Seen from a historical standpoint, the world capitalist economy has indeed reached an impasse.

The ecological cost of growth

The mounting panic in the stock markets at the prospect that China and other BRICS – not to mention the economy in the US and Europe – are heading for another recession, highlights another irresolvable contradiction of capitalist production. A few weeks ago, at the environmental summit in Paris, much play was made of the fact that an agreement had been reached to place a limit on carbon emissions over the next few decades. The threat of global warming running amok was thus, we were told, averted by the wise counsels that have prevailed among the world leaders. And indeed, in the extremities of the crisis, the bourgeoisie does become intelligent. In the wake of 1929 it was able to push aside the objections to state intervention coming from its more backward-looking factions, and to hold back the unfolding economic disaster through the application of state capitalist remedies. Today, in the face of mounting evidence that man-made global warming is not only real but is already becoming a major “cost of production” (as in the case of the floods in the UK, the droughts in the US and Australia, etc), the ruling class now has much less time for those die-hards (many of them financed by the big energy concerns who have most to lose through pollution controls) who insist that global warming is a hoax or has purely natural causes. The wise leaders have understood that something needs to be done.

But the bourgeoisie is caught in a cleft stick. It is seeing the ecological impact of its need to accumulate, to grow without limit. And at the same time it panics when economic growth stutters or goes into reverse. In this sense the die-hards are right: if you restrict “our” national production for the sake of the environment, other national economies will profit. So the measures it adopted at the Paris summit to reduce the impact of accumulation are extremely feeble – no more than a vague promise to curb pollution and cut emissions, without any legal sanctions. If the planet is a forest reserve, it has been entrusted to unscrupulous loggers, for whom the trees are not a source of oxygen, a “sink” for carbon dioxide, or a barrier to floodwaters in the hills, and certainly not a factor of human well-being or an inspiration for artists. They are a valuable commodity, most valuable when they are converted into timber.

Capitalism and war

On these counts alone – the management of the production of life’s necessities, and the protection of the natural environment on which all this depends – the ruling bourgeoisie has proved that it is no longer fit to rule. But the final proof of its incapacity to provide humanity with a future lies in the omnipresence of war.

War has always been part of capitalism. In the days of its ascent, wars, however brutal, were part of its expansion across the world and its replacement of outmoded forms of society. But once the world had, to all intents and purposes, been conquered by capitalism, war increasingly became an end in itself, and even when it brought temporary triumph for the victors, the overall balance sheet for humanity has been negative: the destruction of decades of human labour, the exacerbation of hatred and division, the prospect of new and even more destructive wars. The great rash of wars now spreading from Africa to central Asia, with their focal point in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, which has engendered the desperate flight of millions of human beings to the “haven” of western Europe, is a sign – like the two world wars and the nuclear arms race which marked the 20th century – that capitalism’s drive to accumulate, when it comes up against insuperable barriers, turns into a drive towards self-destruction.

The necessity of communism

The longer capitalism continues, the more it undermines the possibility of replacing it with a human society – a society based on solidarity and cooperation. But at the same time, every aspect of its descent into barbarism adds further proof that such a society is both necessary and possible. If the capitalist economy is in crisis because it can’t sell all the commodities it produces, if it can’t generate enough profit from its production, then we need a society where people produce not for the market and not for profit, but for need. If national economies are driven to plunder nature in order to outdo their rivals, or if the same nation states can only advance their interests through war and destruction, we need to replace competing national states with a unified world community. In short, we need communism.

For us, communism and socialism are the same thing, and they are international or they are nothing. But if the word “communism” has fallen into disrepute because it has been so horribly besmirched by the nightmare of Stalinism, there are any number of politicians selling a new brand of “socialism” and claiming that they are carrying on the great traditions of the workers’ movement of the past. In Britain there’s Corbyn and the Labour left, in Greece Syriza, in Spain Podemos. But none of these “socialisms” ever put into question the need to defend the national economy, not one of them advocates the abolition of the capitalist wage relation and production for the market. All of them offer an updated version of the same state capitalism which has for decades now been the last rampart of the bourgeois mode of production.

These politicians and parties claim that the new society can come about through the existing institutions – through parliament and elections, through strengthening the trade unions and other official bodies. And what they call socialism can indeed be introduced from above, through organs which are an integral part of the present-day state. But genuine communism is, as Marx put it, “the real movement that abolishes the present state of affairs”. It can only come from below, from the unification of the exploited and the oppressed in defence of their own needs, from the bursting asunder all the state bodies which have been maintained to keep them passive and disunited. In short, if we are to have communism, we must have a revolution, the deepest, most far-reaching revolution in the history of humanity.

Amos, 16.1.16

Floods in Britain: the social effect of capitalist production

- 1717 reads

“Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human victories over nature. For each such victory nature takes its revenge on us” (Engels, The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man).

Floods, caused by a series of severe storms that battered the Northern British Isles this December, have brought the misery of repeated flooding to thousands, not just in the North of England but also in Scotland, and Ireland. They are one of a number of phenomena to hit the world this winter, including unseasonably mild weather on the East coast of North America, Western Europe and the North Pole; El Nino and flooding in South America, with the latter inundating 130,000 homes in Paraguay alone. Equally striking is the fact that the media are not passing it off as an ‘Act of God’ or a purely natural disaster, but apportioning blame to government policy on flood defences and considering the contribution of climate change. They do not, however, recognise the role of capitalism itself.

What sort of protection for areas at risk of flooding?

About 16,000 homes in England flooded; Cumbria faced in the third winter in a decade with the sort of flooding that is only supposed to happen once in 100 years; power cuts affecting a similar number of homes and businesses. There have been plenty of people willing to help each other out, including Syrian asylum seekers who volunteered to help the temporarily homeless. Help from the local or national state has been lamentable. The volunteer asylum seekers were set filling sandbags when they were no longer any use as the floods had already ruined homes. When they could have been useful many councils were unable to provide them. In Leeds and York their response was largely restricted to evacuation. Environment Agency spending on flood defences was cut by one fifth after 2010-11, although the fall in the North West of England was much steeper, to about 25% of the previous year’s total. Although the spending has risen since 2011-12 it has not yet reached the previous level. How fortunate for the ruling class that the Environment Agency chairman Sir Philip Dilley should have been on holiday in Barbados during the worst of the flooding and therefore able to become a scapegoat and resign – whatever he personally did or neglected to do, the cuts to the budgets of the very institutions responsible for flood defences and relief show that it is not a priority for the British state.

Insurance firms do not even pretend it is a priority: after all, as private businesses their responsibility is to make a profit. Many households in flood prone areas cannot get insurance against floods, and those that are insured often have to wait weeks for a claims assessor to visit, causing delay in cleaning up their homes.

It is not just a question of how much is spent on flood defences but also of what sort of defences and what sort of land use. First of all the Environment Agency is only responsible for protection against sea and river flooding, while 60% of damage to houses comes from surface or ground water (The Economist, 2.1.16). Secondly, the type of flood defence tends to treat nature as an enemy to be subdued and regulated. Walls are built, although clearly not high enough for this winter’s floods. These can be important, but are not the only approach, as was demonstrated in Pickering in North Yorkshire. There, unable to afford £20 million for a wall high enough to protect against flooding, and aware that the wall would be an eyesore and bad for tourism, they chose to work with nature building 167 leaky dams above the town, plus smaller obstructions, planted woodland and built a bund to store up to 120,000 cubic metres of floodwater. As a result they remained dry while neighbouring towns were flooded.[1] This is not a panacea to be applied everywhere, nor a guarantee against floods, but shows the possibility of a different approach based on understanding the local geography.

There is also the question of land use, and measures taken to support it that make the problems in the towns on lower ground worse. Farmers are permitted by internal drainage boards to dredge the rivers on the hills, straighten them and build up their banks, protecting their fields at the expense of those living downstream. Similarly grouse moors require land drained and heather burned, meaning that it can no longer soak up floodwater. This attracts an agricultural subsidy, as does clearing land of scrub, woodland and ponds even if no actual agriculture takes place on it (Guardian 30.12.15). All these measures increase the likelihood and severity of floods lower down.

These decisions are not down to ignorance since the dangers were already well known in the 19th Century: “When the Italians of the Alps used up the pine forests on the southern slopes … they had no inkling … that they were thereby depriving their mountain springs of water for the greater part of the year, and making it possible for them to pour still more furious torrents on the plains during the rainy season” (Engels, op cit). So why does the ruling class take such decisions? Why for that matter are they building 10,000 homes a year on flood plains, i.e. on land liable to flooding? Why are they not able to take account of the danger to the homes, and potentially the lives, of thousands of people? Engels went on to say “individual capitalists are engaged in production and exchange for the sake of the immediate profit, only the nearest, most immediate results must be taken into account. … In relation to nature, as to society, the present mode of production is predominantly concerned only about the immediate, most tangible result; and then surprise is expressed that the more remote effects of actions directed to this end turn out to be quite different…”

Storms as part of climate change

A far more remote effect of capitalist production than flooding downstream is global warming due to greenhouse gas emissions. Nevertheless this is now so widely accepted that there have been articles discussing whether it is behind this winter’s storms and heavy rain. Science cannot prove climate change based on this or that meteorological event and is therefore not able to state that this or that storm is, in itself, due to such changes. But it would be equally wrong to try and dissociate any particular event from it. Thus, it has been estimated that storms such as Desmond are 40% more likely now than in the past using climate models at global, regional and local levels (see New Scientist 9.1.16); and from another report we learn that “Atmospheric thermodynamics explain that the moisture-holding capacity of the atmosphere is largely influenced by temperature and pressure, and that warmer atmospheres have larger saturation vapour content. The median intensity of extreme precipitation increases with near-surface temperature at a rate of 5.9%–7.7% per degree”[2]. In very technical language this is telling us that warmer air will carry more water vapour and so cause heavier rain. However the relationship between global warming and storms does not end there, since they are actively redistributing heat and moisture across the globe. Storm Frank, before it crossed the Atlantic and received its name, started in North America where it caused flooding that drowned 13 people, and after it hit the British Isles it turned north to carry yet more heat to the Arctic (The Economist 2.1.16). So the weather systems causing these floods were also contributing to the frighteningly high temperatures at the North Pole at the end of December, more than 30oC above the usual, and above freezing point.

For capital this Arctic warming is first and foremost an opportunity bringing not just the hope of ice-free shipping lanes but also the opportunity to extract yet more oil from the area. Meanwhile the bourgeoisie’s political representatives have been at the COP21 climate change conference in Paris, wringing their hands about the danger of global warming. While we will deal with this conference in a future article, we can just note the views of James Hansen, a NASA scientist who was silenced by the US government from 1988 when he started to warn against greenhouse gasses until he retired: “It’s a fraud really, a fake… It’s just worthless words…. As long as fossil fuels appear to be the cheapest fuels out there, they will be continued to be burned.”[3] We also note the actions of the British state in cutting the subsidy for solar power and in its enthusiasm for shale gas, which speak much louder than any words on the COP21 agreement.

Capitalism’s congenital inability to tackle pollution and climate change

So far we have looked at several examples of short term decisions taken regardless of consequences such as flooding on lower ground, and the hypocrisy of governments in the climate change talks. Many think the answer is to campaign against such decisions and demand that states put in place measures such as a carbon tax to create an incentive to use alternatives to fossil fuels, in other words to demand that the capitalist state effectively reform itself. We think this is impossible. It is not just a question of this or that measure, but of the nature of capitalism. Hansen is quite right to point to the fact that the cheapest fuels, fossil fuels, will continue to be burned – no business competing with others, no-one on a wage or other limited income, will be able to afford to do otherwise. He says they only “appear” to be cheapest, but for capitalism the products of nature, and the pollution of it, have no cost. If polar bears go extinct, if small islands are submerged, if pollution in Delhi and Beijing is injurious to health, this does not appear on the bottom line. Those who, like Hansen, recommend a carbon tax to give a financial incentive to reduce emissions, point to British Columbia which has had one since 2008 although the evidence is equivocal at best. Sales of petrol have fallen, although there is evidence of those who can crossing into the USA for cheaper petrol[4]. Total emissions have fallen no faster than those in the rest of Canada[5], and as a tax on goods, compensated for by cuts in other taxes it has a tendency to be regressive, hitting the poor hardest despite a tax credit system designed to compensate for this.

In capitalism the ruling class only acts on the pollution it creates when its effects are direct or at least not too remote, and that usually means something to do with the economy. The UK Clean Air Act of 1956 was not due to the fact that dirty air causes deaths, known about since the previous century, but to the fact that the great smog of 1952 not only caused 12,000 deaths but also brought London to a standstill. The populations of Beijing and Delhi can only hope for a similar incentive to clean up their cities. Right now the bourgeoisie has something much more direct and immediate on their minds, the danger of a new financial crisis caused by phenomena such as “the collapse in demand for credit in China”[6] – in other words the slowing down of its (extremely polluting) growth is a real problem for the economy, and this will carry much more weight in capitalist decision-making than the danger of greenhouse gas emissions.

Engels again: “… by long and often cruel experience and by collecting and analysing historical material, we are gradually learning to get a clear view of the indirect, more remote social effects of our production activity, and so are afforded an opportunity to control and regulate these effects as well. This regulation, however, requires something more than mere knowledge. It requires a complete revolution in our hitherto existing mode of production, and simultaneously a revolution in our whole contemporary social order.” (op cit). Since he wrote this, science has become much more aware of the “remote effects” of our production on the natural world and the danger this poses to many populations as well as to the world’s ecosystems, while at the same time science and technology have become much more powerful, and the most polluting industries have spread to new geographical regions. The management of economy and ecology remains in the hands of a ruling class whose vision is generally limited to a fast buck, whose states apply all the arts of deception recommended by Machiavelli, in an atmosphere that dumbs down history and theory. We simply cannot afford to leave such productive power in the hands of this ruling class.

Alex 14.1.16

[2]. Asian Development Bank report, https://www.adb.org/publications/global-increase-climate-related-disasters [8]. The bank is particularly concerned by “Climate-related disaster risk is defined as the expected value of losses” since its zone of investment is at particular risk from the effects of climate change, and the conclusion of its report states “the danger of climate change presents a greater threat than the current global economic malaise. … we need to build disaster resilience into national growth strategies”.

Rubric:

Middle East: The historical obsolescence of the nation state

- 1901 reads

Militarism and war, central manifestations of capitalism for around a century now, have become synonymous with the decay of the economic system of capitalism and the necessity to overthrow it. War in this period, and into the future, is a central question for the working class.

In the ascendant period of capitalism, wars could still be a factor in historical progress, leading to the creation of viable national units and serving to extend capitalist relations of production on a global scale: “From the formation of the citizen’s army in the French Revolution to the Italian Risorgimento, from the American War of Independence to the Civil War, the bourgeois revolution took the form of national liberation struggles against the reactionary kingdoms and classes left over from feudalism..... These struggles had the essential aim of destroying the decaying political superstructures of feudalism and sweeping away the petty parochialism and self-sufficiency, which were holding back the unifying march of capitalism: (ICC pamphlet Nation or Class). As Marx said in his pamphlet on the Paris Commune, The Civil War in France: “The highest heroic effort of which old society is still capable is national war”.

By contrast, war today and for the last one hundred years, can only play a reactionary and destructive role and is now threatening the very existence of mankind. War becomes a permanent way of life for all nation states, no matter how big or how small; and while not every state possesses the same means to pursue war, they are all subjected to the same imperialist drives. The impasse of the economic system means that a policy of state capitalism is forced on nations new or old, adopted by all on pain of death; and this dynamic can be implemented by bourgeois parties from the far right or extreme left. State capitalism is the refined defence of the nation state and a permanent attack on the working class.

In the ascendant period of capitalism, war tended to pay for itself both economically and politically by breaking down barriers to capitalist development. In the phase of its decay war is a dangerous absurdity, becoming more and more divorced from all and any economic rationale. Just looking at the last 25 years of the so-called “wars for oil” in the Middle East shows that it would take centuries for any profitable return, and that’s assuming that they stop tomorrow.

The nation is a symbol of capitalist decay

Devoting a vast percentage of national resources to war and militarism is now normal for all states, and while this has been the situation since the early 1900’s, it has only intensified today. This phenomenon is directly linked to the historic evolution of capitalism: “Imperialism is not the creation of any one or any group of states. It is the product of a particular stage of ripeness in the world development of capital, an increasingly international condition, an indivisible whole, that is recognisable only in all its relations, and from which no nation can hold aloof at will”[1]. The position you adopt on imperialist war determines which side of the class divide you are on; either support for the rule of capital through the defence of the nation and nationalism (compatible with both Trotskyism and the leftist wing of anarchism), or the defence of the working class and internationalism against all forms of nationalism. National “solutions”, national identities, national liberation, national “struggles”, national defence; all these serve only imperialist and thus capitalist interests. These are diametrically opposed to the interests of the working class whose class war will have to do away with imperialism, its frontiers and its nation states.

In 1900, there were 40 independent nations; in the early 1980’s, there were just fewer than 170. Today there are 195, the latest of which, South Sudan, recognised and supported by the “international community”, has immediately collapsed into war, famine, disease, corruption, warlordism and gangsterism: another concrete expression of the decomposition of capitalism and the obsolescence of the nation state. The new nation states of the 20th and 21st centuries are not expressions of youthful growth but have been born senile and sterile, immediately enmeshed in the webs of imperialism, with their own inward means of repression - interior ministries, secret services and national armies - and outward militarism, with pacts, protocols, agreements for mutual defence, the implantation of military advisors and military bases by the bigger powers.

“Today the nation state is but a cloak that covers imperialistic desires, a battle cry for imperialist rivalries, the last ideological measure with which the masses can be persuaded to play the role of cannon-fodder in imperialist wars”[2]. Since Rosa Luxemburg wrote these words there have been no bourgeois revolutions in underdeveloped countries, but only reactionary contests between bourgeois gangs and their local and global imperialist supporters. The military state and war become the mode of survival for the whole system as every nation, every proto-state, every nationalist expression, and every ethnic or religious identity become direct expressions of imperialism.

We can look a bit closer at the reactionary role of the nation state through a necessarily short overview of the important region of the Middle East over the last century.

War in the Middle East from World War One to the Gulf War

The capitalist nation has been preserved, quadrupled even, over the last 100 years. But its bourgeois democratic programme, its unifying tendencies are dead and buried; and henceforth its “peoples” can only be subjected to its repression or mobilised to defend its imperialist interests as cannon-fodder. Also “... it should be said that the new nations are born with an original sin: their territories are incoherent, made up of a chaotic mixture of ethnic, religious, economic and cultural remnants, their frontiers are usually artificial and incorporate minorities from neighbouring countries. All of this can only lead to disintegration and permanent conflict”[3]. An example of this is the anarchy of nationalisms, ethnicities, and religions that exist in the Middle East. The three major religions are here further sub-divided into a myriad of sects, many in conflict with themselves and others: Shia, Sunni, Maronite, Orthodox and Coptic Christians, Alawite and so on. There are large linguistic minorities and many millions of stateless peoples: Kurds, Armenians, Palestinians and now Syrians.

In World War One it was the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and its treasures, as well as the strategic position of the Middle East (between east and west, between Europe and Africa, the Suez Canal, the Dardanelles strait) that attracted the major powers. Even before oil was discovered in the region, and well before the extent of its oil reserves were realised, Britain mobilised 1.5 million troops in the region. Having resisted the threat from Germany and Russia, and despite rivalries between themselves, most of the region was carved up by Britain and France: Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Transjordan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, a Palestine “Protectorate”, all with borders drawn up by the victorious imperialist powers with a wary eye on each other and on their former antagonists. These absurd “nations” became permanent breeding grounds for further instability and war, not only through the rivalries of the bigger powers but also through regional conflicts between themselves. This often resulted in massive displacements of populations, justified by the need to form distinct national entities: in short they provided the soil for pogromism, exclusion, violence between religions and sects that not only live with us today but have become much more widespread and dangerous: Sunni/Shia; Jews/Muslims; Christians/Muslims and much older sects that were previously left alone but who are now pulled into the imperialist maelstrom. The region has become a violent fusion of totalitarian regimes, religion, terrorism and warlordism - a decay indicative of the fact that there is no solution to capitalist barbarity except the communist revolution. With the Balfour Declaration in 1917, Britain supported the setting-up of a Jewish homeland in Palestine which they planned to use as an ally both locally and against major rivals. It was in this militaristic framework of bloody struggles with the Arab rulers that the Zionist state was born[4]. The USA, the main beneficiary of World War One, was now beginning to supplant Great Britain as the world’s major power and this would be evidenced in the Middle East.

The Stalinist counter-revolution of the 1920s and 30s, aided and abetted by the western powers, only increased the imperialist machinations over the Middle East, up to and including World War Two. In this period the Turks, Arab factions and the Zionists wavered between the camp of Britain or Germany, with the majority eventually choosing the camp of the former. The region was important for both sides[5] but it was relatively spared from the destruction, with the major battlefields of the war being mainly in Europe and the Far East. Overall, and the war’s end was to confirm it, both Britain and Germany were fighting a losing battle here (and elsewhere) as the whole imperialist pecking order was overturned by the emergence of the American superpower. This is further emphasised by the creation of the Zionist state, which was heavily supported by the US (and also initially by Russia) to the detriment of British national interests. The establishment of the nation state of Israel signalled a new zone of conflict whose very birth saw the creation of a huge and intractable refugee problem, and which has grown up in a state of permanent military siege. The existence of Israel is probably one of the most glaring examples of how a country formed in capitalist decadence is framed by war, survives by war and lives in constant fear of war.

Another chapter of imperialism was opened when the Middle East inevitably became a factor in the Cold War between the American and Russian blocs which solidified somewhat after World War Two and led to a number of proxy “engagements” in the region between the two major powers. Thus the Israeli-Arab wars of 1967 and 1973 were at one level proxy wars between the two blocs, and Israel’s crushing victories greatly reduced the USSR’s ability to maintain the footholds it had established in the region, especially in Egypt. At the same time, already in the 70s and early 80s, we could see the germs of the chaotic, multipolar conflicts that have characterised the period since the fall of the USSR and its bloc. Thus the overthrow of the Shah of Iran in 1979 resulted in the formation of a regime which tended to escape from the control of both blocs. Russia’s attempt to capitalise on the new balance of power in the region – its attempted occupation of Afghanistan in 1980 – embroiled it in a long war of attrition which contributed greatly to the collapse of the USSR. At the same time, by encouraging the development of the Islamist Mujahadeen, including the kernel of what became al-Qaida, to lead the opposition to the Russian occupation, the US, Britain and Pakistan were themselves constructing a monster that would soon bite the hand of its creators. Meanwhile US imperialism also had to retreat from its own defeats in Lebanon, largely at the hands of forces acting as proxies for Iran and Syria.

It is during this period that we see the beginnings of the loss of power of the US that is both an expression of and contribution to the ambient decomposition of today. After the breakdown of the Russian bloc came the disintegration of the US directed “alliance” and the centrifugal tendencies towards every nation for itself. The US responded forcefully to this situation, attempting to cohere its allies around it by launching the Gulf War of 1990/91, which resulted in an estimated half-a-million Iraqis being killed (while Saddam Hussein was left in place). But the counter-tendencies were too great and US leadership was irrevocably undermined. Post-9/11, the Evangelical Neo-Cons then acting for US imperialism started further wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that gave the appearance of a crusade against Islam and have further fanned the flames of Islamic fundamentalism.

Today, the further slide into capitalist barbarism

In the 1979 film directed by Francis Ford Coppola, Apocalypse Now, the renegade US Colonel asks his CIA-appointed killer what he thought of his methods. The assassin replies: “I don’t see any method at all”. There is no method in today’s wars in the Middle East except a great free-for-all. There is no economic rationale - trillions of dollars have gone up in smoke from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan alone - just a further descent into barbarism. Fictional character though he is, Colonel Kurtz is symbolic of the export of war from “the heart of darkness”, which is actually in the main centres of capital rather than the deserts of the Middle East or the jungles of Vietnam and the Congo.

In Syria today there are around 100 groups fighting the regime and each other, all of them to a greater or lesser extent supported or directed by local and major powers. The new “nation”, the Caliphate of Isis, with its own imperialism, its cannon-fodder, its brutality and irrationality, is both an independent expression of capitalist decay and a reflection of all the major powers which, one way and another brought it into existence. Isis is currently expanding to all points of the compass, gaining new affiliates in Africa, including Boko Haram in Nigeria, and is also competing with the Taliban in Afghanistan, who are themselves threatening the Helmand region which was for so long the mini-protectorate of the British army. But if it was eliminated tomorrow it would immediately be replaced by other jihadists, such as the al-Qaida affiliated Jahbat al-Nusra. The “War on Terror” Part Two, like Part One, will only increase the terrorism that exists in the Middle East and its export back to the heartlands of capital.

One of the features of the growing number of wars in the Middle East today is the re-emergence of Russia which has taken place on the military, state capitalist level with the ideological cover of the “values” of the old Russian nation. During the Cold War, Russia was kicked out of Egypt, and the Middle East generally, as its power waned. Now, Russia has re-emerged, not in the form of a bloc leader as before – it has only a few weak ex-republics allied to it – but as a decomposition-shaped force that must assert the imperialism of its national “identity”. The weakness of Russia is clear in its desperation to hang onto its bases in Syria – its most important outside of Russia itself. Another factor that will affect much, including Russia, is the present rapprochement between the USA and Iran linked to the 2015 nuclear deal. This deal also expresses a fundamental weakness of US imperialism and is the source of considerable tension between the US and its other main regional allies, Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Wherever you look, the imperialist mess in the Middle East gets increasingly impossible to untangle. There is the position of Turkey, which has not hesitated to pour oil on the fires of war; there is no end to its war with the Kurds and its actions have consequences for the US, Russia and Europe whose interests it plays one against another. Its relations with Russia in particular have hit a low point following the shooting down of a Russian fighter jet, while it has transparently used the pretext of striking back at Isis to hit Kurdish bases. There is the involvement of Saudi Arabia, which although supposedly an ally of the US and Britain has been a major backer for various Islamist gangs in the region, not only through the export of its Wahabi ideology but also with arms and money.

As far as the nation states of decadence go then Saudi Arabia must be one of the worst historical jokes you could find[6]. Undermined by falling oil prices, which Iran has done everything to facilitate (showing oil not as a factor of economic rationale but as a weapon of imperialism), and fearful at the prospect of the rival Iranian theocracy becoming the region’s policeman once again after its recent agreement with the US, the Saudi regime struck a blow against Iran with the execution of the well-known Shia cleric, Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, and further beheadings and crucifixions which have hardly been mentioned in the western media. This planned provocation towards Iran shows a certain desperation and weakness of the Saudi regime as well as more dangers of things sliding out of control. The actions of the Saudi regime here again reveal the centrifugal tendencies of each nation for themselves and the weakness of the major powers, particularly the USA, in controlling them. One thing certain from the current episode of Iranian/Saudi rivalry will be the aggravation of war, pogroms and militarism throughout the region with multiple tensions and uncertain alliances gaining ground. There were already related strains further afield in Egypt – which Saudi Arabia has bankrolled in its anti-Muslim Brotherhood fight – that will now only worsen.

The nation state of Lebanon was already being pulled apart in the 1980s; tensions will become greater now and the consequences of the breakup of this fragile state would be disastrous not least for Israel, whose low level war with the Palestinian factions and Hezbollah rumbles on.

Finally, we should mention the increasing role of China, even if its main points of imperialist rivalry – with the US, Japan and others – are located in the Far East. Having arisen as the subordinate ally of the USSR in the late 40s and 50s, China began to follow a more independent course in the 60s (the ‘Sino-Soviet split’), which led in the short term to a new understanding with the USA. But since the 90s China has become the world’s second biggest economic power and this has vastly increased its imperialist ambitions at a more global level, most notably through its efforts to penetrate Africa. For the moment, it has tended to operate alongside Russian imperialism in the Middle East, blocking US attempts to discipline Syria and Iran, but its potential for disrupting the world balance of power - and thus accelerating the plunge into chaos - remains to a large extent untapped. This offers us further proof that the economic take-off of a former colony like China is no longer a factor of human progress, but brings with it new threats of destruction, both military and ecological.

We began by looking at the reactionary nature of the capitalist nation state, a once progressive expression that has now become not only a fetter to the advance of humanity but a threat to its very existence. The virtual breakup of the nations of Syria and Iraq, forcing millions to flee the war and avoid fighting for any side, the birth of the Caliphate of Isis, the national project of Jahbat al-Nusra, the defence of the ethnic Kurdish homeland – these are all expressions of imperialist decay that offer the populations of these areas nothing but misery and death. There is no solution to the decomposition of the Middle East within capitalism. Faced with this it is vital that the proletariat maintains and develops its own interests against those of the nation state. The situation of the working class in the main centres of capitalism is key here, given the extreme weakness of the proletariat in the war zones themselves. And although the bourgeoisie is subjecting the working class in the heartlands of capital to constant ideological attacks around the themes of the refugees and terrorism, it does not yet dare to mobilise it directly for war. Potentially, the working class remains the greatest threat of all to capitalist order, but it must begin to transform this potential into a reality if it is to avert the disaster that this system is heading towards. Understanding that its interests are international, that the nation state is finished as a viable framework for human life, will be an essential part of this transformation.

Boxer, 13.1.16

This article was contributed by a sympathiser of the ICC.

[1]. The Junius Pamphlet, The crisis in Social Democracy, 1915, Rosa Luxemburg

[2]. Ibid.

[3].‘Balance sheet of 70 years of ‘national liberation’ struggles, part 3: the still-born nations’, International Review 69, https://en.internationalism.org/ir/069_natlib_03.html [12]

[4]. See ‘Notes on Imperialist Conflict in the Middle East’, part one, International Review no. 115, Winter 2003.

[5]. See part 3 of the above in International Review, 118, Summer, 2004, https://en.internationalism.org/ir/118_mideast_iii.html [13]

[6]. We will return to this area in a future article.

Geographical:

Rubric:

Migrants and refugees: victims of capitalist decline, Part 2: The depth of the counter-revolution

- 2134 reads

At the beginning of the 1930s the proletariat had been defeated physically and the world revolution completely crushed. The successive bloodbaths in Russia and Germany after the defeat of the proletariat in Berlin in 1919, the search for scapegoats, the humiliation caused by the Versailles Treaty and the need for revenge, would all give rise to an increase in the spiral of capitalist horror during the twentieth century.

The emergence of a concentration camp world

By proclaiming “socialism in one country”, the new Stalinist regime in Russia was preparing a race to industrialise with a view to catching up with the more advanced economies. Planning for heavy industry and the manufacture of weapons would increase the extreme exploitation of the working class. Up until the terrible depression of the 1930s, the conquering Western countries had also sought a low cost workforce to ‘divide and rule’ over. But with the economic crisis and mass unemployment, migrants and the refugees became more openly unwelcome. The flow of migrants would be quite brutally slowed down from 1929, including to the United States [1]

The latter adopted quotas to filter out the migrants, dividing and separating them from other proletarians. In this context, with whole populations displaced, the deportees and refugees were forcibly moved on and experienced terrible conditions (during and after the war): they often ended up in concentration camps that began to appear pretty much everywhere.

With the crises and the imperialist tensions escalating, a defeated working class was not able to pose any resistance. This would find expression in Spain, in 1936, with the proletariat beginning to be recruited into the war in the name of “anti-fascism”. This new total war mobilised civilians (women, the young, the old) much more brutally and massively than the first Great War. It would prove to be much more destructive and barbaric. The state, by intervening more directly on the whole of social life, opened up a kind of concentration camp era. It would spawn deportations, ethnic cleansing, famines and mass exterminations.

Deportations, massacres and forced labour

The violence of Stalinism, as brutal as it was unpredictable, was a prime example. At the time of the purges the state did not hesitate to arrest genuine communists, to execute 95% of the leaders from one region, to deport entire populations so it could control and manage its territory effectively. In the years 1931-1932, Stalin would chillingly use hunger as a weapon in attempting to break the resistance of the Ukrainians to the forced collectivisations. This terrible, deliberately caused famine led to 6 million deaths in total. In Siberia and elsewhere, millions of men and women were sentenced to hard labour. During 1935, for example, 200,000 prisoners were digging the Moscow-Volga-Don Canal and 150,000 the second Trans-Siberian route. The brutal collectivisation campaign, in which many millions of kulaks were deported to inhospitable re-settlement areas, the plans for heavy industry and the exploitation by forced-march where workers were killed at work (literally), served Stalin’s obsession of wanting “to catch up with the capitalist countries”[2]. Before its entry into the war, in 1941, the Stalinist state was carrying out a real “ethnic cleansing” on its borders, with the aim of strengthening its security. Different populations were suspected of collaboration with the German enemy and so were subjected to large collective displacements. In 1937, the deportation to Central Asia of 170,000 Koreans on simple ethnic grounds, leading to heavy human losses, was a foretaste of what was ahead. Amongst all the displaced that would follow, 60,000 Poles were dispatched to Kazakhstan in 1941. Several waves of deportations then took place after the breakdown of the German-Soviet pact, especially for people of Germanic origin, notably in the Baltic republics who openly became “the enemies of the people”: 1.2 million of them found themselves exiled overnight to Siberia and Central Asia. Between 1943 and 1944, it was the turn of the people of the North Caucasus (Chechens, Ingush ...) and the Crimea (the Tatars) to be brutally displaced. Many of these victims, hungry, criminalised and banished by the “socialist” state, would die during transportation in cattle wagons (through lack of water, food, or from diseases such as typhus). If local people generally showed great solidarity towards those unfortunate exiles, the official propaganda against these new slaves continued its climate of hatred. During transportation, they were often faced with stone-throwing along with the worst possible insults. Upon arrival, according to a report from Beria dated July 1944, “some presidents of the collective farms organised beatings, designed to justify their refusal to hire physically damaged deportees”[3].

In these extreme conditions, there were eventually “ten to fifteen million Soviet citizens” sent into “re-education camps to work”, camps that were officially created by the regime in the 1930s[4].

In Germany, when the Nazis came to power, well before the extermination of its enemies was on the agenda, the concentration camps that would multiply across the land and especially in Poland were initially labour camps. This tendency for the development of camps for prisoners or refugees, that would blossom almost everywhere, even in the democratic countries like France and the United States, had the purpose, besides controlling the population, of exploiting an almost “free” labour power. Traditionally, in selling his labour power, the proletarian allows the capitalist to extract surplus value, that is to say, profit. The terms of the contract ensure that exploitation can achieve the maximum productivity whilst guaranteeing, through the low level of pay, the simple reproduction of labour power. In the concentration camps, labour power was exploited almost absolutely. In Germany, the deportees worked more than 12 hours a day, in any weather, on the orders of “kapos”. Secret arms factories or subsidiaries of large German companies were found in the concentration camps or nearby. These war industries enjoyed almost free, abundant and easily replaceable labour. The reproduction of labour power was reduced to mere survival of the worker / prisoner, the very low productivity of this workforce being partially offset by the very low maintenance costs. The food was limited to a subsistence minimum, and the transport likewise, often reduced to the single trip to a remote and isolated place, that of the camp. In the democratic states, the camps would also be used as part of the strengthening the state’s social control of the prisoner populations and / or the exploitation of their labour power. Thus, faced with the influx of Spanish refugees (120,000 between June and October 1937, 440,000 in 1939), the French Government was responding to these “undesirables” liable to engage in “revolutionary actions”[5]. In North Africa, 30,000 of them were used as forced labour. The Spanish refugees living on French soil were herded into internment camps (the authorities themselves spoke of “concentration camps”) erected in a hurry in the south of the country (especially on the Roussillon beaches). There were, for example, as many as 87,000 refugees in Argelès, exploited as slave labour in appalling conditions, sleeping on the sand, supervised by the “kapos” of the Republican Guard or Senegalese riflemen. Between February and July 1939, about 15,000 Spanish refugees died in these camps, most of them from exhaustion or victims of dysentery.

Later, during the war, among many other examples, we could refer to the United States which also interned more than 120,000 people from March 1942 to March 1946. This was theJapanese-American population, penned in concentration camps in the north and east of California. These victims of state xenophobia were treated terribly, just like the worst criminals.[6]

The genocide of the Jews, one of the pinnacles of capitalist barbarism

We have pointed out that concentration camps in Germany began as labour camps. The largest forced population movements took place in the direction of Germany, through measures such as STO (Service de Travail Obligatoire) in France. Jews were plundered, rounded-up and subjected to mass deportations nearly everywhere in Europe. In factories, agriculture and mining, one quarter of the workforce was forced labour, notably under the Generalplan Ost. Between 15 and 20 million people in total were deported by Nazi Germany to run its war machine! Such a policy increased the number of refugees fleeing the regime and its manhunt. In the 1930s, there were about 350,000 refugees coming from Nazi Germany, 150,000 from Austria (after the Anschluss) and Sudetenland (after its annexation to Nazi Germany).

From 1942 and the plan for the “Final Solution”, the concentration camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chelmno, Treblinka, Belzec, Sobibor, Maidaneck ... would be transformed into death camps. In atrocious conditions, many victims among the six million Jews were transported in convoys and massacred, most gassed and incinerated in large ovens. The worst loss and largest quota of victims was provided by Poland (3,000,000) and the USSR (1,000,000). The extermination camps like Auschwitz (1.2 million) and Treblinka (800,000) were running at full capacity. This barbarism is well known because it was extensively publicised and exploited ideologically ad nauseam after the war by the Allies, thus serving as an alibi to justify or hide their own crimes.

The infernal Nazi propaganda machine was indeed a terrible extension of the pogrom mentality that had been introduced in the 1920s, a mentality which sanctioned the bloody defeat of the proletariat and its great revolutionary figures who were equated with “Jewry”: “even though many Jewish revolutionaries such as Rosa Luxemburg or Trotsky considered themselves to be non-Jews (...) the Israelite appears as the harbinger of subversion, as a destructive agent vis-à-vis basic values: homeland, family, property, religion. The enthusiasm of many Jews for all forms of modern art or for the new means of expression such as cinema, still justifies their reputation for a corrosive spirit”[7]. In fact, the defeat of the revolution allowed the great democracies to see Hitler as nothing more, nothing less, than an effective bulwark against “Bolshevism”. For all states at the time, the amalgam between Jews and communism was very common. Churchill himself accused the Jews of being the leaders of the Russian Revolution: “There is no need to exaggerate the part played in the creation of Bolshevism and the emergence of the Russian Revolution by these internationalist and mainly atheist Jews”[8]. The idea of a “Judeo-Marxist” plot was first spread by the “white troops” and cultivated on the basis of a widespread anti-Semitism: “is it necessary to point out that Hitler was not the source of this anti-Semitism (...) after the First World War, this anti-Semitism was found in most European countries”[9]. So the Jews would be systematically stigmatised, marginalised and become scapegoats without this being too much of an embarrassment to the democratic leaders, some of whom, like Roosevelt, already had openly xenophobic and anti-Semitic tendencies. Many of the Jews who were in Poland, the USSR and in ghettos, had already often been forced to flee the democratic countries because of this anti-Semitism (contrary to what one would have us believe, the anti-Semitism of the Vichy regime, for example, was not a spontaneous phenomenon, nor was it limited to his particular regime). Consequently, the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws of 1935 were, not surprisingly, introduced almost unnoticed. By isolating and marginalising Jewish citizens, their property would be plundered with impunity, in good conscience, since they were seen as very degenerate beings. It is in fact this whole dynamic, this nauseating breeding ground, that lay behind the hygienicist and eugenicist propaganda of the Nazis. From January 1940, the programme “Action T4” (forced euthanasia) in Germany already foreshadowed the Holocaust, methodically programming the elimination of the physically and mentally handicapped. Faced with the tragedy that was to follow, the Allies refused help to the Jews “in order to not destabilize the war effort” (Churchill). It is well established that the Allies were co-sponsors and accomplices in a genocide that was primarily a product of the capitalist system. Very early on, the democratic countries were firm in refusing to provide assistance to the Jews who were seen as outcasts and were unwelcome[10]. Faced with the Nazi repression and persecution, the Popular Front government in France, for example, would show itself intractable. Thus, behind a democratic veneer, a circular from the hand of Roger Salengro, dated August 14, 1936, noted: “we shouldn’t let (…) any German émigré into France and should start removing all foreigners; German subjects, or those arriving from Germany after the August 5 1936, will not be provided with the necessary documents ... “[11]

The barbarism comes from both imperialist camps

During the Second World War, all the actions and administrative measures to deport, expel and exterminate the populations were far more imposing and notably had more dramatic consequences than in 1914 to 1918. The number of refugees / migrants was on a much larger scale. The violence used – from the concentration camps and the gas chambers, the carpet bombing, the phosphorous gas, nuclear bombs, the use of chemical and biological weapons - had claimed millions of lives and caused lasting suffering and trauma after the war. The balance sheet is terrifying! The destruction killed in total nearly 66 million people (20 million soldiers and 46 million civilians) compared with 10 million in 1914-1918! At the end of the Second World War, 60 million people had to be relocated, ten times more than in the First World War! At the heart of Europe itself, 40 million died. In East Asia, in China, more than 12 million people died in direct military confrontations and there were nearly 95 million refugees in China. During the war, a number of sieges and military battles were among the bloodiest in history. To give some examples: at Stalingrad, almost a million men died on both sides in a hellish inferno. In a siege that lasted nearly three years, at least 1.8 million died. The battle to capture Berlin killed 300,000 German and Russian soldiers and more than 100,000 civilians.

The famous Battle of Okinawa killed 120,000 soldiers but also 160,000 civilians. Japanese troops slaughtered 300,000 Chinese in Nanking. The atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, according to historian Howard Zinn, reportedly left up to 250,000 dead. The terrible American bombing of Tokyo in March 1945 caused 85,000 deaths. In the USSR, there were 27 million victims. Ukraine would lose 20% of its population, Poland 15% (mostly Jews). Hundreds of cities in Europe were partly ruined or virtually destroyed. In Russia, 1,700 towns were affected, in Ukraine, 714, and nearly 70,000 villages were destroyed. In Germany, incendiary phosphorous carpet bombs dropped by the Allies and Bomber Command claimed a huge number of victims, razing the cities of Dresden and Hamburg (nearly 50,000 dead). A city like Cologne was 70% destroyed. It was subsequently estimated that there were between 18 and 20 million homeless at the end of the war in Germany, 10 million in Ukraine. The number of war orphans was equally significant: two million in Germany, more than one million in Poland. Some 180,000 children were reduced to the status of vagabonds in the streets of Rome, Naples and Milan.

The appalling suffering caused by this destruction was very often accompanied by terrible vengeance and acts of barbarity against terrorised civilians and refugees. This was true of the Allies, although they were portrayed as the “great liberators”: “hubris, lightning revenge befalls the survivors; the discovery of the atrocities committed by the vanquished only fuels the good conscience of the conqueror”[12].

The accumulation of violence generated by decadent capitalism, once released, produced the most atrocious scenes, those of “ethnic purification” and acts of unimaginable cruelty. During and after the war in Croatia, nearly 600,000 Serbs, Muslims and Jews were killed by the Ustasha regime wishing to “clean up” the entire country. Greek communities were massacred by the Bulgarian army; Hungarians did the same to the Serbs in Vojvodina. During the war, defeats were always accompanied by tragic migrations. Thus, for example, five million Germans would flee before the Red Army. Many would die, often lynched by the roadside. This was one of those heroic episodes for the “liberators”, for these “knights of freedom”, who would cynically assume the role of prosecutor after the war despite their own unpunished crimes: “the terrible plight of populations in eastern Germany during the advance of the Red Army is still unforgettable (...) The Soviet soldier became the instrument of a cold will, of deliberate extermination (...) Columns of refugees were crushed under the treads of the tanks or systematically strafed from the air. The population of whole cities was massacred with refined cruelty. Naked women were crucified on the doors of barns. Children were decapitated or had their heads crushed with rifle butts or were thrown alive into pig troughs (...) The German population of Prague was massacred with a rare sadism. After being raped, women would have their Achilles tendons cut and were condemned to die bleeding in agony on the ground. Children were machine-gunned at the school gate, thrown onto pavements from the floors of the buildings or drowned in fountains; in total, more than 30,000 victims (...) the violence did not spare the young auxiliary signalmen of the Luftwaffe, thrown alive onto burning haystacks. For weeks, the river Vltava (Moldau) carried thousands of bodies; some whole families were nailed onto rafts”.[13]

It is difficult to say how many women were raped by German soldiers during the war. What is certain is that with the forces of the Allies advancing and occupying the “liberated” territory, another test awaited them. There were a million women raped in Germany by Allied troops; Berlin alone had around 100,000 cases. The estimates for Budapest lie in a range from 50,000 to 100,000 raped.

What we especially want to emphasise is that far from intervening in “defence of freedom”, the involvement in the war of the Allies and the great democracies was aimed at defending purely imperialist interests. The fate of populations and refugees did not concern them until they were in charge and they could be used as exploited labour. They never made mention of the fate of Jews in their propaganda during the war, even denying them help and abandoning them into the hands of the Nazis. The Allies’ motive for entering into the war had nothing to do with a desire for “liberation”. For France and Britain, it was actually about defending the “European balance of power”. For the United States, it was about countering its Japanese rival in the east and blocking the threat of the USSR, and for the latter, it was to extend its influence within Western Europe; in short, for purely strategic, imperialist and military reasons. What else can we expect? It was absolutely not to “free Germany” from the “brown plague” that they acted. This fable is nothing but a diabolic fabrication invented at the time of the liberation of the camps. It was all prepared by the Allied staff and politicians, anxious to hide their own crimes (let’s not be so naïve to think that the military and politicians in the democracies never make propaganda!). If the “liberation” was able to end the practices of the Nazi occupiers, this was primarily an indirect consequence of achieving a purely military objective and not for “humanitarian” reasons. The best proof of this is that the major democratic powers continued to defend their imperialist interests, creating new victims, colonial massacres and new divisions after the war that also produced new waves of refugees and destitute people.

WH 18 July 2015

In the next article [16], we will continue dealing with the same question, from the Cold War until the fall of the Berlin wall and into the current period.

[1]. ‘Immigration and the workers’ movement’, International Review no.140, 1st quarter 2010.

[2]. Note that Stalinist Russia itself was actually a capitalist country, a caricatured expression of the tendency towards state capitalism in the decadence of this system.

[3]. Isabelle Ohayon, La déportation des peuples vers l’Asie centrale. Le XXe siècle des guerres, Editions de l’Atelier, 2004.

[4]. Marie Jégo, Le Monde, March 3rd, 2003.

[5]. P. J Deschodt, F. Huguenin, La République xénophobe, JC Lattes, 2001

[6]. According to one veteran from Guadalcanal: “The Japanese cannot be regarded as an intellectual (...), he is more an animal” and a Marine General also said: “To kill a Japanese, it was really like killing a snake”. See Ph Masson, Une guerre totale, coll. Plural.

[7]. Ph Masson, op. cit.

[8]. Illustrated Sunday Herald, February 8, 1920, quoted by Wikipedia.

[9]. Ph Masson, op. cit.

[10]. Read our pamphlet Fascisme et démocratie, deux expressions de la dictature du capital.

[11]. P. J Deschodt, F. Huguenin, op cit,

[12]. See Ph. Masson, op. cit.

[13]. See Ph. Masson, op. cit.

Rubric:

Stop the War Coalition: an ‘alternative’ policy for British imperialism

- 1541 reads

When Jeremy Corbyn became leader of the Labour Party in Britain he stepped down from being chair of the Stop the War Coalition (StWC), while continuing to support its activities. Opponents of Corbyn have used this continuing connection to attack Labour and its leader. The ensuing arguments have pursued familiar lines with Corbyn and friends accused of being ‘anti-West’ and ‘pro-jihadi’ and his detractors portrayed as ‘bombers’ and Blairites.

In reality the strand of thinking represented by the Stop the War Coalition is just one set of options on offer for British imperialism. For example, opposition to British membership of NATO is among the military options open to the British bourgeoisie. The dominant strand in the British ruling class is for continuing participation in NATO, but a minority (including StWC) favour British military independence (presumably with the possibility of temporary alliances with other powers if such are deemed to be in the interests of British capitalism).

Opposition to NATO goes along with a determination for Britain to leave the EU, which is the policy of the Socialist Workers Party and the Communist Party of Britain (two significant parts of the StWC – Andrew Wilson of the CPB was/is chair before and after Corbyn). They might complain that they should not be lumped in with the usual right wing anti-EU little Englanders, but there’s no logical reason why not. In the Libyan war of 2011, for example, leftists were divided over whether to support the Gaddafi regime or the opposition backed by a variety of powers, in particular France and Britain. The StWC backed Gaddafi’s status quo and they were joined by the likes of Nigel Farage of the UK Independence Party, who did so in the name of political stability in the region.