Submitted by International Review on

At the same time when European and US capitalism started to penetrate into Japan and China, these capitalist countries also tried to open up Korea.

There were many parallels in the development of Korea with China and Japan. In Korea, much as Japan, all contact with Westerners was fraught with peril. Only relations with China were permitted in the mid 19th century. Until the mid 1850s the only foreigners present in Korea were missionaries. As the capitalist nations started to show their presence in the region, any Korean activity against foreign citizens was taken as a welcome pretext to impose their presence by force. Thus when in 1866 French missionaries were killed in Korea, France sent a few military ships to Korea, but the French troops were beaten. In 1871 the USA sent several ships up the Taedong River to Pyongyang, but the US ships were also defeated.

However, during that phase there was yet no determination amongst the European countries or the USA to occupy Korea.

The USA was still under the impact of the civil war (1861-1865), and the westward expansion of capitalism was still in full swing in North America; England was engaged in putting down revolts in India and focussing its forces (with France) on penetrating into China. Russia was still colonising Siberia. So while the European countries were focussing their forces on China and other areas of the world, Japan seized its chance and quickly started to push for the opening of Korea for its commodities.

Through a show of force Japan managed to secure a treaty opening three Korean ports for Japanese traders. Moreover Japan, in order to thwart off Chinese influence, "recognised" Korea as an independent country. The declining Chinese empire could do nothing but encourage Korea to look for protection from a third state in order to resist pressure from Japan. The USA was amongst the first countries to recognise Korea as an independent state in 1882. In 1887 Korean forces for the first time turned to the USA asking for “support against foreign forces”, i.e. against Japan, Russia and Britain.

As Japan increased its exports, Korea became more and more dependent on trade with Japan. 90% of Korea’s exports went to Japan in the mid 1890s, more than 50% of its imports came from Japan.

The flood of foreign commodities which poured into the mainly peasant dominated country contributed sharply to the ruin of many peasants. The pauperisation in the countryside was one of the factors which provoked a strong anti-foreigner resentment.

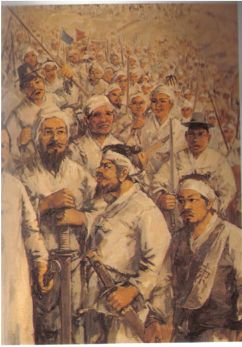

Similar to the Taiping movement in China during the 1850-60s, a popular revolt – the Tonghak (“Eastern Learning”) unfolded in Korea in the 1890s (though it had seen precursors already in the 1860s), marked by a strong weight of peasant revolt directed against the penetration of foreign goods. There was as yet no working class presence in the movement, due to the very limited number of factories in the country.

Similar to the Taiping movement in China during the 1850-60s, a popular revolt – the Tonghak (“Eastern Learning”) unfolded in Korea in the 1890s (though it had seen precursors already in the 1860s), marked by a strong weight of peasant revolt directed against the penetration of foreign goods. There was as yet no working class presence in the movement, due to the very limited number of factories in the country.

Anti-feudal forces and peasants dominated the movement, which put forward a mixture of nationalist, religious and social demands.

Tens of thousands of peasants fought with primitive weapons against local rulers. The tottering ruling feudal class, feeling threatened by the Tonghak-movement and unable to suppress the movement alone, appealed to Chinese and Japanese forces to help them in repressing the movement.

The mobilisation for repressing the Tonghak movement by Chinese and Japanese forces was staged as a springboard for fighting over the control of the Korean peninsula. China and Japan clashed for the first time in modern history – not over the control of their respective territories, but over the control of Korea.

In July 1894 Japan started war with China, which lasted half a year. Most of the fighting took place in Korea, although Japan’s main strategic objective was not just control over Korea but also over the strategically important Chinese Liaotung Peninsula at the Chinese Sea.

The Japanese troops drove the Chinese army out of Korea, occupied Port Arthur(a Chinese port city on the Liatong peninsula in the Chinese Sea) , then the Liaotung peninsula, Manchuria – and started heading for Beijing. In the face of the strong Japanese superiority, the Chinese government asked the USA to broker a truce. As a result of the war, China had to concede Japan the Liaotung peninsula, Port Arthur, Dairen, Taiwan and the Pescadore Islands, accept a compensation payment of 200 million Tael (360 million yen) and open Chinese ports to Japan. The Chinese “compensation” payment was going to fuel the Japanese arms budget, because the war had been very expensive for Japan, costing about 200 million Yen, or three times the annual government budget. At the same time this “compensation” payment was draining the resources of China even more.

But already then, following the first sweeping Japanese victory, the European imperialist sharks opposed a too crushing Japanese victory. They did not want to concede Japan too many strategic advantages. In a “triple-intervention” Russia, France and Germany opposed the Japanese occupation of Port Arthur and Liaotung. In 1895 Japan renounced from Liaotung. Still without any ally at the time, Japan had to withdraw (the British-Japanese treaty was only signed in 1901). Initially Germany, France and Britain wanted to grant loans to China, but Russia did not want China to become too dependent on European rivals and offered its own loans. Until 1894 Britain had been the dominant foreign force in the region, in particular in China. Britain did not want any Japanese expansion into China and Korea, but until then Britain considered Russia the biggest danger in the region.

While the Japanese war triumph over China meant that Japan now was considered by the other imperialist rivals as an important rival in the far East, it was striking that the main battlefield of the first war between China and Japan was Korea.

The reasons are obvious: surrounded by Russia, China and Japan, Korea’s geographic position makes it a springboard for an expansion from one country towards another. Korea is inextricably lodged in a nutcracker between the Japanese island empire and the two land empires of Russia and China. Control over Korea allows control over three seas – the Japanese sea, the Yellow sea and East China Sea. If under the control of one country, Korea could serve as a knife in the back of other countries. Since the 1890s, Korea has been the target of the imperialist ambitions of the major sharks in the area initially only three: Russia, Japan and China - with the respective support and resistance of European and US sharks acting in the background. Even if, in particular, the northern part of Korea has some important raw materials, it is above all its strategic position which makes the country such a vital cornerstone for imperialism in the region.

As long ago as the 19th century, for Japan as the leading imperialist power in the far East, Korea became the vital bridge towards China.

The China-Japanese war over Korea was going to deal a big blow to the Chinese ruling class, at the same time it was an important spark to Russian imperialist appetites.

However, it is impossible to limit the conflict to the two rivals alone, because in reality, this war illustrated the qualitative general sharpening of imperialist tensions.

Japan’s main gains on Chinese territory – for example the Liaotung Peninsula – were immediately countered by a group of European powers. By 1899 Britain had strengthened its position in China (Hong Kong, Weihaiwei, the island guarding the sea lanes to Beijing), it held a monopoly in the Yangtze valley, Russia had seized Port Arthur (see below) and Tailenwan (Dairen, Dalny), was encroaching upon Manchuria and Mongolia, Germany had seized the Kaochow Bay and Shantung, France was given special privileges in the Hunan Province. “The Chinese war is the first even in the world political era in which all the cultural states are involved and this advance of the international reaction, of the Holy Alliance, should have been responded to by a protest by the united workers parties of Europe”.1

The 1894 China-Japanese war in fact brought all the main imperialist rivals of Europe and the far East into conflict with each other – a process which was to gain more momentum, as soon as another European imperialist shark appeared in the far East.

1 (Rosa Luxemburg in a speech at the party conference in Mainz in Sept. 1900, in Rosa Luxemburg, Collected Works/Gesammelte Werke, vol 1/1, p. 801)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace