International Review - 1st semester 2014

- 1495 reads

A history of class struggle in South Africa

- 8297 reads

After West Africa,1we begin a second series on the history of the African workers’movement with a contribution on the class struggles in South Africa. A country famous mainly for two reasons: on the one hand, its mineral wealth (gold, diamonds, etc.) due to which it is relatively well developed; and on the other, its monstrous apartheid system, the aftermath of which we still see today.At the same time, apartheid gave birth to a huge “icon”, namely Nelson Mandela, considered its principal victim but above all the product of this system of another age, who with his titles of “hero of the anti-apartheid struggle”and man of“peace and reconciliation of the peoples of South Africa”was revered throughout the capitalist world.Mandela’s media image veils everything else to the point where the history and struggles of the South African working class before and during apartheid are either completely ignored or distorted by being systematically categorised under the rubric of “anti-apartheid struggles” or “national liberation struggles”.Of course, for bourgeois propaganda, all struggles can be incarnated in Mandela, even though it is public knowledge that since coming to power, Mandela and his party, the African National Congress (ANC), have not exactly been kind to the strikes of the working class2.

After West Africa,1we begin a second series on the history of the African workers’movement with a contribution on the class struggles in South Africa. A country famous mainly for two reasons: on the one hand, its mineral wealth (gold, diamonds, etc.) due to which it is relatively well developed; and on the other, its monstrous apartheid system, the aftermath of which we still see today.At the same time, apartheid gave birth to a huge “icon”, namely Nelson Mandela, considered its principal victim but above all the product of this system of another age, who with his titles of “hero of the anti-apartheid struggle”and man of“peace and reconciliation of the peoples of South Africa”was revered throughout the capitalist world.Mandela’s media image veils everything else to the point where the history and struggles of the South African working class before and during apartheid are either completely ignored or distorted by being systematically categorised under the rubric of “anti-apartheid struggles” or “national liberation struggles”.Of course, for bourgeois propaganda, all struggles can be incarnated in Mandela, even though it is public knowledge that since coming to power, Mandela and his party, the African National Congress (ANC), have not exactly been kind to the strikes of the working class2.

The main purpose of this contribution is to restore the historical truth about the struggles between the two fundamental classes, namely the bourgeoisie (for whom apartheid was only one means of domination) and the proletariat of South Africa that, for most of the time, was left to struggle for its own demands as an exploited class, from the epoch of the Dutch-British colonial bourgeoisie and then under the Mandela/ANC regime.In other words, a South African proletariat whose struggle fits perfectly with that of the world proletariat.

A brief survey of the history of South Africa

According to some historical sources, this area was originally occupied by the Xhosa, Tswana and Sotho people who settled there between 500 and 1000AD. In this regard, the historian Henri Wesseling tells us the following:

“South Africa was not a virgin land when European ships landed for the first time in 1500 at the foot of Table Mountain. It was populated by different ethnic groups, mostly nomads. Dutch settlers divided them into Hottentots and Bushmen. They regarded them as two totally distinct peoples from a physical and cultural point of view. Bushmen were smaller than the Hottentots and they spoke a different language. Moreover, they were more ‘primitive’, practicing hunting and gathering, while the Hottentots had reached the level of pastoral peoples. This traditional dichotomy has long dominated the historiography. Today, we no longer use these terms, but those of Khoikhoi or Khoi for Hottentots and San for the Bushmen, the term Khoisan serving to designate the ethnic group they form together. In fact, currently, one emphasizes less the distinction between these people, mainly because they are both very different from neighboring ethnic groups speaking Bantu languages and formerly known as Kaffirs, from the Arabic kafir (infidel). This term has equally fallen into disuse.”3

It can be noted how the Dutch settlers considered themselves the first inhabitants of this region, as colonial ideology established rankings between “primitive” and “advanced”. Furthermore the author indicates that the term South Africa is a (recent) political concept and that many of its populations are historically from neighboring countries in southern Africa.

As far as European colonization is concerned, the Portuguese were the first to set foot in South Africa in 1488 followed by the Dutch who landed in the area in 1648.The latter decided to settle there permanently from 1652, markingthe beginning of the permanent “white”presence in South Africa.In 1795, Cape Town was occupied by the British, who 10 years later took possession of Natal, while the Boers (Dutch) led the Transvaal and Orange Free State in winning recognition of their independence from Britain in 1854. As for the various African states or groups, through prolonged warfare they resisted the presence of European settlers on their soil before finally being defeated by the dominant powers.At the end of the wars against the Afrikaners and the Zulus, the British proceeded in 1920 to unify South Africa under the name “Union of South Africa”, which it remained until 1961 when the Afrikaner regime decided to simultaneously leave the Commonwealth (the English-speaking community) and change the name of the country.

Apartheid was officially established in 1948 and abolished in 1990.We will return to this later in more detail.

Concerning imperialist rivalries, South Africa played the role of “delegated policeman”for the Western imperialist bloc in southern Africa, and it was in this role that Pretoria intervened militarily in 1975 in Angola which was supported by the Eastern imperialist bloc with Cuban troops.

South Africa is considered today as an “emerging”member of the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China), and is looking to make its entry into the arena of the great powers.

Since 1994, South Africa has been governed principally by the ANC, the party of Nelson Mandela, in company with the Communist Party and the COSATU trade union federation.

The South African working class emerged at the end of the 19th century and constitutes today the largest and most experienced industrial proletariat on the African continent.

Finally, we think it useful to explain two related but nevertheless distinct terms, that we will use often in this contribution, namely the terms “Boer” and “Afrikaner”, which have Dutch roots.

Those called Boers (or Boertrekkers) were originally Dutch farmers (predominantly small peasants) who in 1835-1837 undertook a vast migration in South Africa due to the abolition of slavery by the British in the Cape Colony in 1834.The term is still used today for descendants, direct or not,of these farmers (including factory workers).

Concerning the definition of the term Afrikaner, we refer to the explanation given by the historian Henri Wesseling: “The white population that settled in the Cape was of different origins.It consisted of Dutch, but also many Germans and French Huguenots.This community gradually adopted a different way of life.One could even say that a national identity was formed, that of the Afrikaners, who considered the British government as a foreign authority.”4

We can therefore say that the term refers to a kind of identity claimed by a number of European migrants of the time, a notion that is still used in recent publications.

Birth of South African capitalism

The birth of capitalism in each region of the world like South Africa has been marked by specific or local characteristics. Nevertheless it developed in general in three different phases, as by described by Rosa Luxemburg:

“(In its development) we must distinguish three phases: the struggle of capital against natural economy, the struggle against commodity economy, and the competitive struggle of capital on the international stage for theremaining conditions of accumulation.

The existence and development of capitalism requires an environment of non-capitalist forms of production, but not every one of these forms will serve its ends. Capitalism needs non-capitalist social strata asa market for its surplus value, as a source of supply for its meansof production and as a reservoir of labour power for its wage system.”

In South Africa, capitalism followed these three phases. In the 19th Century there was a natural economy, a market economy and a workforce sufficient to develop wage labour.

“In the Cape Colony and the Boer Republics, pure peasant economy prevailed until the sixties of the last century. For a long time the Boers had led the life of animal-tending nomads; they had killed off or driven out the Hottentots and Kaffirs with a will in order to deprive them of their most valuable pastures. In the eighteenth century they were given invaluable assistance by the plague, imported by ships of the East India Company, which frequently did away with entire Hottentot tribes whose lands then fell to the Dutch immigrants.

(…)Boer economy in general and on the whole remained patriarchal and based on natural economy until the sixties. But their patriarchal attitude did not deter the Boers from extreme brutality and harshness. It is well known that Livingstone complained much more about the Boers than about the Kaffirs.

(…)In fact, peasant economy and great capitalist colonial policy were here competing for the Hottentots and Kaffirs, that is to say for their land and their labour power. Both competitors had precisely the same aim: to subject, expel or destroy the coloured peoples, to appropriate their land and press them into service by the abolition of their social organisations. Only their methods of exploitation were fundamentally different. While the Boers stood for out-dated slavery on a petty scale, on whichtheir patriarchal peasant economy was founded, the British bourgeoisie represented modern large-scale capitalist exploitation of the land and the natives.”5

We should note the fierceness of the struggle engaged in by Boers and the British for conquest and the establishment of capitalism in this zone which emerged, as elsewhere,“mired in blood and filth”. In the end it was British imperialism that dominated the situation and concretized the advent of capitalism in South Africa, as related in her own way by the researcher Brigitte Lachartre:

“British imperialism, when it manifested itself in the south of the continent in 1875, had other aims: citizens of the leading economic power of the time, representatives of the most developed mercantile and capitalist society in Europe, the British imposed on their colony in southern Africa a much more liberal native policy than that of the Boers.Slavery was abolished in the areas they controlled, while the Dutch settlers fled into the interior of the country to escape the new social order and the administration of the British settlers.After defeating the Africans by arms (a dozen ‘Kaffir’wars in a century), the British devoted themselves to ‘liberating’ the labour force: the defeated tribes were regrouped in tribal reserves whose limits were more and more restricted; Africans were prevented from leaving without authorisation and their pass in order.But the true face of British colonization appeared with the discovery of diamonds and gold in 1870.A new era began which brought about a profound transformation of all social and economic structures of the country: mining led to industrialization, urbanization, disruption of traditional African societies, but also of the Boer communities, immigration of new waves of Europeans (...).”6

Clearly, this statement can be read as a concrete continuation of the process described by Rosa Luxemburg, by which capitalism emerged in South Africa. In its struggle against the “natural economy”, British economic power had to break the old tribal societies and violently get rid of the old forms of production such as slavery, incarnated by thethe Boers who were forced to flee to escape the modern capitalist order. This was at the root of the wars between the proponents of the old and the new economic order by which the country passed so rapidly to modern capitalism, thanks to the discovery of diamonds (1871) and gold (1886). The “gold rush” translated itself into a lightning acceleration of industrialization of the country as a result of the exploitation and commercialisation of precious materials, which hugely attracted capitalist investors from the developed countries. It was therefore necessary to recruit engineers and skilled workers,and in this way thousands of Europeans, Americans and Australians came to settle in South Africa. And the City of Johannesburg came to symbolize this emerging dynamism by its rapid development. On 17 July 1896, a census showed that the city had had 3,000 inhabitants in 1887 and 100,000 ten years later. A little over ten years later the white population had grown from 600,000 to over a million. In the same period the gross domestic product (GDP) rose from £150,000 to nearly £4 million. This is how South Africa became the first and only African country to be relatively developed on an industrial scale – something which was not slow to whet the appetites of rival economic powers:

“The economic and political center of South Africa was no longer in the Cape, but in Johannesburg and Pretoria.Germany, Europe’s biggest economic power, was established in South West Africa and had expressed an interest in South East Africa.If the Transvaal showed itself unwilling to submit to the authority of London, the future of England would be challenged in the whole of South Africa.”7

At this time you can see that behind the economic issues lurked imperialist issues between the major European powers vying for control of this region. Moreover, British power did everything to limit the presence of its German rival to the west of South Africa, which is today called Namibia (colonised in 1883), after neutralising Portugal, the other imperialist presence with far more limited means.The British Empire could therefore boast that it was the sole master in command of the booming South African economy.

But the economic development of SouthAfrica, powered by mineral discoveries, very quickly ran into a series of problems which in the first place were social and ideological:

“Economic development, stimulated by the discovery of minerals, will soon face the white settlers with a profound contradiction (...).On the one hand the introduction of the new economic order required the creation of a waged labour force; on the other, the release of the African workforce from the reserves and out of their traditional subsistence economy put in jeopardy the racial balance of the whole territory.At the end of the last century (the 19th), the African populations were therefore subject to a multitude of laws with often contradictory effects.Some aimed to make them migrate to areas of white economic activities to submit to wage labor.Others tended to keep them partly on the reserves.Among the laws intended to make manpower available, there were some which penalized vagrancy in order to ‘tear the natives away from this idleness and laziness, teach them the dignity of work, and to contribute to the prosperity of the state.’There were others to submit Africans to taxation.(…) Among other laws,those on passes were intended to filter the migrations, to steer them according to the needs of the economy or stop them in the event of a flood.”8

We see here that the British colonial authorities found themselves caught up in contradictions related to the development of the productive forces. But we can say that the strongest contradiction here was ideological, when British power decided to consider the black labour force on segregationist administrative criteria, in particular with the laws on passes and the penning of Africans. In fact, this policy was in flagrant contradiction with the liberal orientation that led to the abolition of slavery.

Difficulties also related to the colonial wars. After suffering defeats and winning the wars against its Zulu and Afrikaner opponents between 1870 and 1902, the British Empire had to digest the extremely high cost of its victories, especially that of 1899-1902, both in human and economic terms. Indeed, the “Boer War” was a real butchery:

“The Boer War was the greatest colonial war of the modern imperialist era.It lasted more than two and a half years (11 October 1899 to 31 May 1902).The British engaged around half a million soldiers, 22,000 of whom were killed in South Africa.Their total losses, that is to say killed, wounded, and missing, rose to more than 100,000 men.The Boers, meanwhile, mobilized nearly 100,000 men.They lost more than 7,000 soldiers and nearly 30,000 died in the camps.An unknown number of Africans fought alongside one or the other side.The losses they suffered are also undetermined.Tens of thousands of them probably lost their lives.The British War Office also calculated that 400,346 horses, donkeys and mules died during the conflict, as well as millions of cattle belonging to the Boers.This war cost the British taxpayer £200 million, or ten times the annual budget of the army or 14% of national income in 1902.If the subjugation of the future British subjects of Africa cost on average fifteen pennies per head,the submission of the Boers however cost £1000 per man.”9

In other words, an open pit of warfare inaugurated the entry of British capitalism into the 20th century. Furthermore, we can see in the details of this horrible butchery that the Nazi concentration camps found a source of inspiration. British capitalism developed a total of forty four camps destined for the Boers where about 120,000 women and children were imprisoned. At the end of the war in 1902 it was found that 28,000 white detainees had been killed, including 20,000 children under the age of 16.

Yet it was without remorse that the commander of the British Army, Lord Kitchener, justified the massacres in speaking of the Boers as “a species of savages born from generations leading a barbarous and solitary existence.”10

This is rich coming from a major war criminal. Certainly we must note that in this butchery, Afrikaner troops were not to be outdone in terms of mass killings and atrocities, and that the Afrikaner leaders were later allies of the German army during the Second World War,above all to settle accounts with British power.

“Defeated by British imperialism,submitted to the capitalist system, humiliated in their culture and traditions, the Afrikaner people (...)organized from 1925 to 1930 a strong movement to rehabilitate the Afrikaner nation.Its vengeful, anti-capitalist, anti-communist and profoundly racist ideology designated Africans, mestizos, Asians and Jews as a threat to the Western civilization they claimed to represent on the African continent.Organized at all levels, school, church, union and terrorist secret societies (the best known is the Broederbond), Afrikaners later proved fervent partisans of Hitler, Nazism and its ideology.”11

The fact that the Afrikaner workers were dragged into this same movement shows the immensity of the obstacle to be crossed by the working class of this country to join the struggles of workers of other ethnicities.

This conflict permanently shaped relationships between the British and Afrikaner colonialisms on South African soil until the fall of apartheid. To divisions and ethnic hatred between British and Afrikaner whites, can be added those between on the one hand these two categories and on the other blacks (and other people of colour) that the bourgeoisie systematically used to destroy all attempts at unity in the workers’ ranks.

Birth of the working class

The birth of capitalism led to the dislocation of many traditional African societies. From the 1870s, the British Empire began a liberal colonial policy by abolishing slavery in areas it controlled, in order to “liberate” the labour force then consisting of Boer and African farm workers. We have noted that the Boer settlers themselves continued to exploit black farmers under the old form of slavery before being defeated by the British. But ultimately it was the discovery of gold which accelerated sharply the birth of capitalism and the emergence of the working class:

“There was no shortage of capital. Exchanges in London and New York willingly supplied the necessary funds.The global economy, which was growing, demanded gold.Workers streamed in too.Mining attracted crowds in the Rand.People went there not in their thousands, but tens of thousands.No city in the world knew a development as rapid as Johannesburg.”12

In the space of 20 years the European population of Johannesburg grew from a few thousand to 250,000, the majority of whom were skilled workers, engineers and other technicians. These are the ones who gave birth to the South African working class in the marxist sense of the term, that is to say, those who, under capitalism, sell their labour in exchange for a wage. Capital had a strong and urgent need for a more or less skilled labour force which it could not find on the spot whithout recourse to migrants from Europe, including the British Empire. But gradually, as economic development progressed, the industrial apparatus was driven to recruit more and more unskilled African workers from the interior of the country or from outside, including Mozambique and Zimbabwe. From then the workforce of the South African economy truly “internationalized” itself.

As a result of the massive arrival in South Africa of British-born workers, the working class was immediately organized and supervized by the British trade unions and in the early 1880s there were numerous companies and corporations which were created on the “English model” (the trade union). This meant that workers of South African origin, as groups or individuals without organisational experience, could only with difficulty organize outside of the pre-established unions13. Certainly, there were dissensions within the unions as well as in parties claiming to defend the working class, with attempts to develop an autonomous union activity on the part of radical proletarian elements who could no longer put up with the “treachery of the leaders.” But these were in a tiny minority.

Everywhere in the world where there are conflicts between the classes under capitalism, the working class always secretes revolutionary minorities defending, more or less clearly, proletarian internationalism. This was also the case in South Africa. Some elements from the working class were at the origin of struggles but also initiated the formation of proletarian organizations. We propose to introduce three figures from this generation in the form of a short summary of their trajectories.

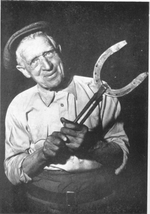

Andrew Dunbar (1879-1964). A Scottish immigrant, he was general secretary of the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) created in South Africa in 191014. He was a railway worker in Johannesburg and actively participated in the massive strike of 1909 after which he was dismissed. In 1914 he fought against the war and participated in the creation of the International Socialist League (ISL), which belonged to the revolutionary syndicalist tendency. He also fought against the repressive and discriminatory measures against Africans which earned him the sympathy of black workers. He was also responsible for creating the first “African Union”modeled on the IWW in 1917. But his sympathy for the Russian revolution became more and more enthusiastic, so he decided with other comrades to form the “Communist Party of Africa” in October 1920 on an essentially syndicalist platform and of which he was secretary. In 1921 his organization decided to merge with the official Communist Party which had been formed. But he was expelled a few years later and in the wake of this he abandoned his union activities.

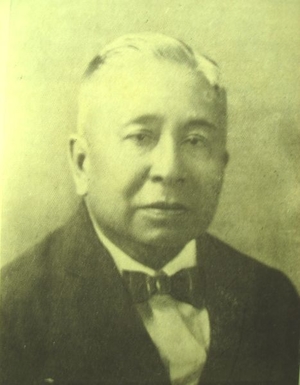

Andrew Dunbar (1879-1964). A Scottish immigrant, he was general secretary of the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) created in South Africa in 191014. He was a railway worker in Johannesburg and actively participated in the massive strike of 1909 after which he was dismissed. In 1914 he fought against the war and participated in the creation of the International Socialist League (ISL), which belonged to the revolutionary syndicalist tendency. He also fought against the repressive and discriminatory measures against Africans which earned him the sympathy of black workers. He was also responsible for creating the first “African Union”modeled on the IWW in 1917. But his sympathy for the Russian revolution became more and more enthusiastic, so he decided with other comrades to form the “Communist Party of Africa” in October 1920 on an essentially syndicalist platform and of which he was secretary. In 1921 his organization decided to merge with the official Communist Party which had been formed. But he was expelled a few years later and in the wake of this he abandoned his union activities. TW Thibedi (1888-1960). Considered a prominent trade union member of the IWW (he joined in 1916). He was originally from the South African town of Vereeniging and had a teaching job in a school attached to a church in Johannesburg. As part of his trade union activities he advocated class unity and mass action against capitalism. He was part of the left wing of the African nationalist party, the South African Native National Congress (SANNC). Thibedi was also a member of the ISL and, during a strike movement led by this group in 1918, along with is comrades, he suffered harsh police repression. A member of the South African CP from its formation, he was expelled in 1928 but due to the reaction of many of his comrades he was reinstated before finally being driven from the party. He then decided to sympathize briefly with the Trotskyist movement before entering into complete anonymity. The sources we have do not give a total strength of South African Trotskyist militants at that time.15

TW Thibedi (1888-1960). Considered a prominent trade union member of the IWW (he joined in 1916). He was originally from the South African town of Vereeniging and had a teaching job in a school attached to a church in Johannesburg. As part of his trade union activities he advocated class unity and mass action against capitalism. He was part of the left wing of the African nationalist party, the South African Native National Congress (SANNC). Thibedi was also a member of the ISL and, during a strike movement led by this group in 1918, along with is comrades, he suffered harsh police repression. A member of the South African CP from its formation, he was expelled in 1928 but due to the reaction of many of his comrades he was reinstated before finally being driven from the party. He then decided to sympathize briefly with the Trotskyist movement before entering into complete anonymity. The sources we have do not give a total strength of South African Trotskyist militants at that time.15- Bernard Le Sigamoney (1888-1963). Of Indian origin and from a farming family, he was an active member of the Indian IWW union and as with his above-mentioned comrades he was also a member of the ISL. He showed himself in favour of the unity of the industrial workers of South Africa, and along with his fellow ISL comrades he was at the head of important strike movements in 1920/1921. However, he did not join the Communist Party and decided to abandon his political and union activities, going to study in Britain in 1922. In 1927 he returned to South Africa (Johannesburg) as an Anglican missionary clergyman while resuming his trade union activities within an organization close to the IWW. He was then denounced as a “troublemaker” by the authorities and eventually became discouraged, simply working in the church and promoting civil rights for people of colour.

So here are three “portraits” of the trajectories of union and political militants which are quite similar despite being of different ethnic origin (European, African and Indian). Above all they share an essential common characteristic: proletarian class solidarity, an internationalist spirit and a great combativity against the capitalist enemy. It is they and their comrades in struggle who are the precursors of the current working class fighters in South Africa.

Other organizations, of different origins and nature, were active within the working class. These are the main parties and organizations16claiming more or less formally at their origins to be working class or to defend its “interests”, excluding the Labour Party which remained faithful to its bourgeoisie since its active participation in the first world slaughter. More precisely, we give here an overview17 of the nature and origin of the ANC and of the South African CP as part of the forces of the ideological containment of the working class since the 1920s.

– The ANC. This organization was created in 1912 by and for the indigenous petty bourgeoisie (doctors, lawyers, teachers and other functionaries, etc.), individuals who demanded democracy, racial equality and defended the British constitutional system, as illustrated in the words of Nelson Mandela:

“For 37 years, that is to say, until 1949, the African National Congress fought with scrupulous respect for the law (...) It believed that the grievances of the Africans would be considered after peaceful discussions and that we would move slowly towards full recognition of the rights of the African nation.”18

In this sense, since its birth up until the 1950s,19far from seeking to overthrow the capitalist system, the ANC led peaceful actions respectful of the established order, and was therefore very far from seeking to overthrow the capitalist system. This same Mandela boasted of his “anti-communist”struggle, as outlined in his autobiography A Long Walk to Freedom. But its Stalinist orientation, suggesting an alliance between the (“progressive”) bourgeoisie and the working class, allowed the ANC to rely on the CP to gain a foothold in the ranks of the workers, especially in the base of the unions that these two parties together control even today.

– The South African Communist Party. The CP was created by elements claiming to defend proletarian internationalism and as such a member of the Third International (1921). In its beginnings it advocated the unity of the working class and put forward the perspective of the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of communism. But by 1928 it became simply an executive arm of Stalinist policies in the South African colony. The Stalinist theory of “socialism in one country” was accompanied by the idea that the underdeveloped countries were required to go through “a bourgeois revolution” and that, in this vision, the proletariat could fight against colonial oppression but not establish any proletarian power in the colonies at this time.

The South African CP took this orientation to absurd lengths, becoming the faithful lapdog of the ANC in the 1950s, as this quote illustrates: “The CP made offers of service to the ANC. The Secretary General of CP explained to Mandela: “Nelson, what do you have against us? We are fighting the same enemy. We are not talking about dominating the ANC; we are working in the context of African nationalism.” And in 1950 Mandela accepted that the CP would put its militant apparatus in the service of the ANC, thus giving him control over a good part of the labour movement and a significant advantage allowing the ANC to take hegemony over the whole of the anti-apartheid movement. In exchange the ANC would provide a legal front for the prohibited CP apparatus.”20

Thus, both openly bourgeois parties have become inseparable and are now at the head of the South African government for the defence of the interests of national capital and against the working class which they oppress and massacre, as in the strike of the miners at Marikana in August 2012.

Apartheid against the class struggle

This barbaric word is hated today worldwide even by its former supporters as symbolizing and incarnating the most despicable form of capitalist exploitation of the layers and classes belonging to the South African proletariat. But before going further, we propose one definition among others of this term: in the “Afrikaans” language spoken by the Afrikaners, apartheid more precisely means “separation.” This includes all kinds of separation (racial, social, cultural, economic, etc.). But behind this formal definition of apartheid lies a doctrine promoted by the “primitive”capitalists and colonialistswhich combines economic and ideological objectives:

“Apartheid is derived from both the colonial system and the capitalist system; in this dual capacity, it stamps on South African society divisions of racial characteristics in the first place and inherent divisions of class in the second.As in many other parts of the globe, there is almost perfect coincidence between the black races and the exploited class. At the other extreme, however, the situation is less clear. Indeed, the white population cannot be regarded as a dominant class without further ado. It is, certainly, constituted by a handful of owners of the means of production, but also from the mass of those who are dispossessed: agricultural and industrial workers, miners, service workers, etc. So there is no identity between the white race and the dominant class. (…) But, nothing like this has ever happened [the white workforce rubbing shoulders with the black workforce on an equal footing] or will ever happen in South Africa as long as apartheid is in effect. Because this system is designed to avoid any possibility of the creation of a multiracial working class.This is where the anachronistic system of South African power, its mechanisms dating from another era,come to the aid of the capitalist system which generally tends to simplify relationships within society. Apartheid - in its most comprehensive form- came to consolidate the colonial edifice, at the moment when capitalism was at risk of bringing down the entire power of the Whites. The means was an ideology and legislation aiming to annihilate class antagonisms within the white population, to extirpate the germs, to erase the contours and replace them with racial antagonisms.

By replacing the contradictions of a terrain difficult to control (division of society into antagonistic classes) with ones more easily manageable, the non- antagonistic division of society between races, white power has almost achieved the desired result: to constitute a homogeneous and united block on the basis of white ethnicity- a bloc all the more solid because it feels historically menaced by black power and communism - and on the other side, to divide the black population within itself, by different tribes or by social groups with different interests.

Dissonances, class antagonisms that are minimized, ignored or erased on the white side are encouraged, emphasized and provoked on the black side. This enterprise of division - facilitated by the presence on South African soil of populations of diverse origins- has routinely been conducted since colonization: detribalization of one part of the African population, the retention in traditional structures of another; evangelization and training of some, denial of any possibility of education of others, establishing small elites of leaders and officials, pauperisation of the great masses; and finally, the putting in place, to great fanfares,of an African, Mestizo, Indian, petty bourgeoisie - a buffer ready to interpose itself between their racial brothers and their class allies.”21

We generally agree with this author’s framework for defining and analyzingthe system of apartheid. We are particularly in agreement when it states that apartheid is above all an ideological instrument in the service of capital against the unity (in struggle) of different members of the exploited class; in this case the workers of all colours. In other words, the apartheid system is primarily a weapon against the class struggle as the motor of history, the only one capable of overthrowing capitalism. Also, if apartheid was theorized and fully applied from 1948 by the most backward Afrikaner fraction of the South African colonial bourgeoisie, it was the British, bearers of the “most modern civilization”, who laid the foundations of this despicable system.

“Indeed, it is from the early nineteenth century that the British invaders took legislative and military measures to group part of the African population in ‘reserves’, allowing or forcing the other part to leave them to be employed across the country in diverse economic sectors. The area of these tribal reserves was fixed in 1913 and slightly enlarged in 1936 to offer the (black) population only 13% of the national territory. These tribal reserves,fabricated in every way by white power (...) were named Bantustans (...),’national homelands for the Bantus’, each theoretically to regroup members of the same ethnicity.”22

Thus, the idea of separate races and populations was initiated by the British colonialism which methodically applied its famous strategy of “divide and rule” by implementing ethnic separation, not only between blacks and whites but even more cynically between black ethnic groups.

However, the proponents of the system could never prevent the breakdown of their own contradictions, inevitably generating the confrontation between the two antagonistic classes. Clearly under this barbaric system, many workers’ struggles were conducted by white workers as well as black workers (or mestizo and Indian).

Certainly the South African bourgeoisie was remarkably successful in rendering workers’ struggles powerless by permanently poisoning the class consciousness of the South African proletariat. This was reflected in the fact that some groups of workers often fought at the same time against their exploiters but also against their comrades of a different ethnic group, and fell into the deadly trap set by the class enemy. In sum, rare were the struggles uniting workers of different ethnic origins. We also know that many so-called “workers’” organizations, namely unions and parties, facilitated the task of capital by endorsing this policy of the “racial division “of the South African working class. For example, the unions of European origin along with the South African Labour Party, defended first (or exclusively) the “interests” of white workers. Similarly, the various black movements (parties and unions) struggled first of all against the system of exclusion of the blacks by claiming equality and independence. This orientation was incarnated principally by the ANC. We should note the particular case of the South African CP which, at first (in the early 1920s), tried to unite the working class without distinction in the fight against capitalism but was soon to abandon the terrain of internationalism by deciding to focus on “the black cause.” This was the beginning of its definitive “Stalinization”.

Strike movements and other social struggles between 1884/2013

First workers’struggle in Kimberley

By coincidence the diamond that symbolically gave birth to South African capitalism was also the origin of the first movement of proletarian struggle. The first workers’ strike broke out in Kimberley, the “Diamond Capital”, in 1884, when British-born miners decided to fight against the decision of the mining companies to impose the so-called “compound” system (ie. forced labour camps) reserved up until then for black workers. In this struggle the miners organized strike pickets to impose a balance of power enabling them to win their demands, while to break the strike the employers on the one hand engaged “scabs” and on the other troops armed to the teeth who were not slow to fire on the workers.There were 4 deaths among the strikers,who nevertheless continued the struggle with a vigour which forced the employers to meet their demands. This was the first movement of the struggle between the two historical forces in South African capitalism that ended in blood but also victory for the proletariat. Therefore we can say that it was here that the real class struggle began in capitalist South Africa, laying the foundations for future confrontations.

Strike against wage cuts in 1907

Not content with the work rates which they imposed on the workers to improve performance, the Rand employers23 decided in 1907 to reduce salaries by 15%, in particular those of British-born miners who were considered to be “privileged.” As in the Kimberley strike, employers recruited strike breakers(very poor Afrikaners) who, without being in solidarity with the strikers, nevertheless refused to do the dirty work they were ordered to. Despite this the employers were eventually able to wear the strikers down. We should note that the sources we have to hand talk about the strike’s extent but do not give a total for the number of participants in the movement.

Strikes and demonstrations in 1913

Faced with massive wage cuts and deteriorating working conditions, miners entered massively into struggle. During 1913 a strike was launched by mine workers against the additional hours the company wanted to impose on them. And it did not take much to generalise the movement to all sectors, with mass demonstrations which nevertheless were violently broken up by the forces of order. In the end twenty dead and a hundred wounded were counted (officially).

Railway and coal miners’strike in 1914

At the beginning of the year a series of strikes broke out among both coal miners and railway workers against the degradation of working conditions. But this movement of struggle was in a particular context; that of the preparations for the first generalized imperialist slaughter. In this movement we can see the presence of the Afrikaner fraction, but set apart from the British fraction. Although both were well supervised by their respective unions, each defending its own “ethnic clients.”

Accordingly the government hastened to impose martial law to physically break the strike and its initiators, imprisoning or deporting a large number of strikers, the exact number of whom is still unknown. In addition, we want to emphasize here the particular role of unions in this strike movement. It was in this same context of the repression of the struggles that the union and Labour Party leaders voted for “war credits” by supporting the entry of the Union of South Africa into the war against Germany.

Labour unrest against the war in 1914 and attempts to organize

If the working class was generally muzzled during the 1914-1918 war, some proletarian elements did however try to oppose it by advocating internationalism against capitalism. Thus:

“(...)In 1917, a poster appears on the walls of Johannesburg, convening a meeting for July 19: ‘Come and discuss issues of common interest between white and indigenous workers.’ This text is published by the International Socialist League (ISL), a revolutionary syndicalist organization influenced by the American IWW (...) and formed in 1915 in opposition to the First World War and the racist and conservative policies of the South African Labour Party and craft unions. Comprising at the beginning mostly white activists, the ISL moves very quickly towards black workers, calling in its weekly newspaper International, to build ‘a new union that overcomes the limitations of trades, skin colors, races and of sex to destroy capitalism by a blockade of the capitalist class.’”24

By 1917, the ISL was organizing coloured workers. In March 1917, it founded an Indian workers’ union in Durban. In 1918, it founded a textile workers’ union (also later formed in Johannesburg) and a horse drivers’ union in Kimberley, the diamond mining town. In the Cape, a sister organization, the Industrial Socialist League, founded in the same year a sweets and confectionery workers’ union.

The July 19 meeting was a success and formed the basis of weekly meetings of study groups led by members of the ISL (including Andrew Dubar, founder of the IWW in South Africa in 1910). These meetings discussed capitalism, the class struggle and the need for African workers to unionize in order to obtain wage increases and to abolish the pass system. On 27 September, the study groups were transformed into a union, the Industrial Workers of Africa (IWA), modelled on the IWW. Its organizing committee was composed entirely of Africans. The demands of the new unions were simple and uncompromising in a slogan: SifunaZonke! (“We want everything!”).

Finally, here is the expression of the birth of proletarian internationalism. An internationalism taken up by a minority of workers but of great importance at the time, because it was the moment when many proletarians were bound and dragged into the first world imperialist slaughter by the traitor Labour Party in the company of the official unions. Another aspect that illustrates the strength and dynamic of these small internationalist groups is the fact that elements (including the International Socialist League and others) were able to emerge from them in order to form the South African Communist Party in 1920. It was these groups, seemingly dominated by supporters of revolutionary syndicalism, which could actively promote the emergence of radical unions especially among black and coloured workers.

A wave of strikes in 1918

Despite the harshness of the time with martial law suppressing any reaction or protest, strikes could occur:

“In 1918, an unprecedented wave of strikes against the cost of living and for salary increases, bringing together white and coloured workers, overwhelms the country. When the judge McFie imprisons 152 African municipal workers in June 1918, urging them to continue to “do the same job as before” but now from prison under the supervision of an armed escort, progressive whites and Africans are outraged. The TNT (Transvaal Native Congress, forerunner of the ANC) called for a mass rally of African workers in Johannesburg on June 10.”25

An important or symbolic fact should be noted here: this is the only (known) involvement of the ANC in a movement of the class struggle in the first sense of the term. This is certainly one of the reasons explaining the fact that this nationalist fraction as a result had an influence within the black working class.

Massive strikes in 1919/1920 drowned in blood

During 1919 a radical union (the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union), consisting of black and mixed race employees but without white workers, launched a massive strike especially among the dockworkers of Port Elizabeth. But once again this movement was crushed militarily by the police backed by armed white groups, causing over 20 deaths among the strikers. Here again the strikers were isolated which ensured the defeat of the working class in an unequal battle on a military terrain.

In 1920, this time it was African miners who sparked one of the biggest strikes in the country affecting some 70,000 workers. The movement lasted a week before being crushed by the forces of order who, armed with guns, liquidated a large number of strikers. Despite its massiveness, this movement of African workers could not count on any support from the white unions, which refused to call a strike or aid the victims of the bullets of the colonial bourgeoisie. Unfortunately this lack of solidarity promoted by the unions became systematic in each sturggle.

In 1922 an insurrectionary strike crushed by a well-equipped army

At the end of December 1921, the coal mine bosses announced massive wage cuts and layoffs aimed at replacing 5000 European miners with indigenous workers. In January 1922, 30,000 miners decided to fight against the attacks of the mining employers. Faced with the procrastination of the unions, a group of workers took the initiative by establishing a committee to fight and declaring a general strike. In this way the miners forced the union leaders to follow the movement, but this strike was not quite “general” because it concerned only the “whites”.

Faced with the pugnacity of the workers, the united state and employers then decided to use the utmost military means to defeat the movement. In order to deal with the strike the government declared martial law and mobilised some 60,000 thousand men with machine guns, cannons, tanks and even airplanes.

For their part, seeing the extent of their enemy’s forces, the strikers began to arm themselves by purchasing weapons (guns, etc.) and organizing themselves into commandos. We therefore witnessed a veritable military battle as in a conventional war. At the end of the fight on the workers’ side there were more than 200 dead, 500 injured, 4,750 arrests, 18 death sentences. Clearly, this was a real war, as if South African imperialism,which took active part in the first world butchery,wished to extend its activity by bombing the miners as if it was facing German troops. By this gesture the British colonial bourgeoisie was demonstrating its absolute hatred of the South African proletariat, but also its fear of it.

In terms of lessons learned from this movement, it must be said that despite its military character, the bloody confrontation was above all a real class war, of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, with, however, unequal means. This only underlines the fact that the main power of the working class is not military but resides above all in its greatest possible unity. But instead of seeking the support of all the exploited, the miners (whites) fell into the trap set by the bourgeoisie with its plan to replace the 5,000 European workers by indigenous workers. This was shown tragically by the fact that throughout the battle between the European miners and the armed forces of capital, other workers (black, coloured and Indian), some 200,000 of them, were working or idle. It is also clear that, from the outset, the bourgeoisie was clearly aware of the weakness of the workers who went into battle deeply divided. The abject recipe of “divide and rule”was applied here with success well before the formal establishment of apartheid (whose main purpose as we recall was to contain the class struggle). But above all the bourgeoisie took advantage of its military victory over the South African proletarians to reinforce its grip on the working class. It organized elections in 1924 from which emerged victorious the populist parties defending“white interests”, namely the National Party (Boer) and the Labour Party, which formed a coalition government. It was this coalition government that passed the laws establishing racial divisions, as far as considering a breach of work contract by a black worker as a crime; or again imposing a system of passes for blacks and establishing compulsory residence zones for natives. Similarly there was a “colour bar”aimed at reserving skilled jobs for whites, providing them with a much higher salary than blacks or Indians. To this were added other segregationist laws including one entitled “The Industrial Conciliation Act” to ban non-white organizations. It was on the basis of this ultra repressive apartheid system that the Afrikaner government legally established apartheid in 1948.

In this way the bourgeoisie succeeded in permanently paralyzing all expressions of proletarian class struggle and it was not until the eve of the Second World War that we see the working class get its head above water by taking the path of the class struggle. In fact, between late 1920 and 1937, the field of struggle was occupied by nationalism: on the one hand, by the South African CP, the ANC and their unions, and on the other, by the Afrikaner National Party and its satellites.

Lassou (To be continued)

1 See the series “Contribution to a history of the workers’ movement in Africa”, on Senegal in particular, in the International Review nos.145, 146, 147, 148 and 149.

2In August 2012, the police of the ANC government massacred 34 strikers at the Marikana mines.

3See Henri Wesseling, Le partage de l’Afrique, Editions Denoel, 1996, for the French translation.

4 Ibid.

5Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital, Section 3, Chapter 27, “The Struggle Against Natural Economy”,https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1913/accumulation-capital/ch2... [1]

6Brigitte Lachartre, Luttes ouvrières et libération en Afrique du Sud, Editions Syros, 1977.

7Henri Wesseling, ibid.

8BrigitteLachartre,ibid.

9Wesseling, ibid.

10Cited inWesseling, ibid.

11Lachartre, ibid.

12Wesseling, ibid.

13 The South African government certainly contributed to this with laws against all non-white organization.

14The IWW was at the time one of the few trade union movements to organize white and non-white workers, not only in the same union but in the same union branches, regardless of race. See our articles in International Review nos. 124, 125: https://en.internationalism.org/internationalreview/200601/1609/iww-fail... [2]

15 Lucien van der Walt (Bikisha collective media), https://www.zabalaza.net [3]

16 We will return later to the unions claiming to defend the working class.

17In the next article we will we will develop on the role of the parties/unions active within the working class.

18Quoted by Brigitte Lachartre, ibid.

19It is after the formal establishment of apartheid in 1948 that the CP and the ANC enter into armed struggle.

20Circle Leon Trotsky, Presentation 29/01/2010, website www.lutte-ouvri [4]ère.org

21Lachartre, ibid.Our emphasis.

22Lachartre, ibid.

23The Rand is the common name for the Witwatersrand (White Waters Ridge) region which saw the first discoveries of gold and the first industrialisation of the country.

24Une histoire du syndicalisme révolutionnaire en Afrique du Sud [5].(See also 1816-1939: Syndicalism in South Africa [6])

25https://www.pelloutier.net [7], cited above.

Historic events:

Geographical:

- Africa [12]

- South Africa [13]

Deepen:

People:

- Nelson Mandela [15]

- Andrew Dunbar [16]

- TW Thibedi [17]

- Bernard Le Sigamoney [18]

Rubric:

A history of trade unionism in the Philippines

- 18284 reads

Introduction and early history

The creation of the world market is capitalism’s great historical achievement. For the first time in history, the whole of humanity has been brought together in a single network of commerce and industry; for the first time in history also, the revolutionary class is a worldwide class. This means that the historical evolution of any country is no longer determined by local or even by regional conditions, but fundamentally by the overall development of world capitalism.

That said, the local and national forms that this development takes are always strongly influenced by the specific history that predates capitalism, and by geography. The case of the Philippines is no exception to this general rule, and to understand the development of Filipino unionism we must therefore understand something of Filipino history.

Geographically, the Philippines is a vast archipelago of over 7000 islands, of which some 2000 are inhabited.1 Prior to the beginning of colonization by Spain from 1521 onwards, the archipelago – unsurprisingly – was not united in a single political or even cultural entity. To this day, some 150 languages and dialects are spoken in the Philippines and at least 20% of the population does not speak the national language (Filipino, a derivative of Tagalog which is spoken by 29% of the population).

Situated on the eastern flank of the South China Sea, with China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Indonesia as its immediate maritime neighbors, the archipelago was integrated as much as 2000 years ago into a vast trading network which brought Indian, Chinese, and even Persian influences to the islands: Islam in particular made its appearance from 1200 CE onwards and remains dominant in the southern island of Mindanao.

Despite the emergence of various kingdoms (whose rulers often took the Indian title of "rajah") and sultanates, the majority of the archipelago was divided into fiefdoms of varying sizes known as barangays: the word continues to designate the Philippines' smallest administrative unit. The barangays' rulers – the datus – owed their position in part to their membership of an aristocratic caste, but also and largely to their own personal power. Rulers could lose power or prestige, or even be overthrown if they failed to live up to their promises.

Spanish colonialism profoundly modified this traditional social structure: the fluid system of barangays and power based on personal prestige and tribute was transformed into one based on land ownership and debt servitude. Power was divided between Spanish overlords placed in authority over encomiendas (settlements created for the purposes of tax collection), local chiefs whose authority was guaranteed by the Spanish in exchange for cooperation with the colonial power, and the Catholic Church, which became a major landowner in its own right: "dependency and indebtedness characterized this multifaceted relationship [between rulers and ruled]. At best it gave way to a paternalistic relationship, at worst it created an exploitative set up".2 It could be argued that this form of political domination based on a mixture of wealth, family connections, personal prestige and the ability to mobilize groups of supporters, has simply mutated with the arrival of capitalism and survives to this day in the form of domination of the Filipino bourgeoisie, strongly marked by clientelism.

Spanish colonization during the 16th century was by no means a mere extension to the Philippines of the feudal social structure which still largely dominated Spain itself. On the contrary, the driving force behind Spanish and Portuguese expansion to the Far East was the desire of the merchant classes, and of the crown which stood to profit from the undertaking, to break into the immensely lucrative spice trade with the East, and to shatter the monopoly exercised by Ottoman, Arab, and to an extent Venetian merchants. By tying the Philippines into a Spanish imperial economy that already existed on the other side of the Pacific, colonization extended the world market of an emerging capitalism from Europe all the way to China, where an embryonic monetary and capitalist economy was already developing under the Ming dynasty. By the beginning of the 17th century, Manila was thus – together with Macao under Portuguese rule – one of the main points of contact between Europe and Asia, and the lynch-pin of trade between Asia and the Americas. Silver was in huge demand by Chinese merchants, and "When the Manila galleon established the link across the Pacific with New Spain, Chinese junks rushed to meet it. Goods were traded in Manila solely for Mexican silver, to a volume of around a million pesos every year".3 From the outset, Filipino workers were involved in this worldwide commercial network: "European ships of the 'country trade' were worked, even in the early days of the Portuguese, by mixed crews with a majority of local sailors. Even ships from the Philippines employed 'few Spaniards, many Malays, Hindus, and Filipino mestizos'".4

Another important factor in Filipino history is the role of religion, and especially of the Catholic Church, introduced by the Spanish colonizers as a justification of their rule and a means of eliminating rival religions which could serve as a rallying point for opposition to the colonial power.

In Europe, ever since its establishment as an official state religion by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine in the 4th century CE, the Catholic Church in particular has had to accommodate a constant contradiction between the biblical ideal of poverty and service to the poor,5 and the material reality of the Church's enormous wealth and social position as temporal overlord. In general, the Catholic Church tried to incorporate the ideal of poverty into its own structures of power and wealth, for example through the creation of monastic orders like the Cistercians or the Franciscans. In the Philippines, this contradiction was given an added twist by the fact that "It was not even until the 19th century that select members of the Chinese mestizo ["mixed blood"] and Filipino illustrado [ie educated] class were for the first time admitted into the priesthood".6 As a result of these material and ideological contradictions, the Church in the Philippines included both corrupt and ruthless exploiters of Filipino labor (especially on the monastic estates, which by the end of the 19th century owned some 171,000 hectares of prime agricultural land7), and courageous and dedicated defenders of the rights of the labouring population (after the 1872 Cavite revolt, for example, three priests – Fathers Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora – were garrotted to death for their supposed part in the conspiracy).

Conflict within the Catholic Church between Filipino nationalism and attempts to defend the poor on the one hand, and the Church's role as landlord and defender of the colonial power on the other, led in 1902 to the creation of the Iglesia Filipina Independiente with the Catholic priest Gregorio Aglipay as its first "Obispo Maximo" (see below). Paradoxically, this came just as the Catholic Church's role as defender of the colonial power ended with Spain's eviction from the Philippines by the United States.

Our very brief consideration of some important features of the history of the Philippines prior to the 20th century would be incomplete without a look at its geography. The Philippines' position in the South China Sea has always been, and continues to be, crucial, both commercially and militarily. For the Spaniards, as we have seen, the Philippines were the commercial gateway to China, and this was even more true for the USA. In the first decades of the 20th century, the increasing importance of China as a region of competition and conflict between rival imperialist powers, and the rise of Japan as a formidable industrial power in its own right,8 increased the military significance of the Philippines: their defense played an important part in slowing the Japanese advance towards Australia in World War II, and their reconquest by the American army was a key moment in Japan's military defeat. Following World War II, the Philippines served as a rear base for the American military effort in Vietnam, and the US naval base at Subic Bay remained one of the US' key military installations throughout the Cold War,9 until its closure in 1992 by the Filipino government. The closure was of short duration: increasing fears of Chinese expansionism led to the signature in 1999 of a "Visiting Forces Agreement" which allowed US ships to use Subic Bay during the joint US-Filipino Balikatan military exercises, and to a reported 2012 agreement for a permanent US military presence in the base.

The 19th century: capitalism, nationalism, and the workers' movement

Despite the backwardness of the Spanish economy, and the weakness of the Spanish bourgeoisie, the 19th century saw an ever-tighter integration of the Filipino economy into the world capitalist market. The low-volume, high-value trade of the Manila galleon with the Americas was replaced by farming for cash crops, notably logging, tobacco and sugar. Simultaneously, and as a direct consequence, there emerged a new ruling stratum of wealthy landowners and merchants including in particular Chinese mestizos linked to the trading families of Fukien and Kwantung, and members of what became known as the principalia: leading Filipino or Spanish mestizo families who had successfully accumulated landed wealth, but who were also often linked to their share-cropping tenants by family or tribal ties. These wealthy families often sent their children to Spain for their education, thus encouraging the development of a Spanish language but specifically Filipino culture borne by Filipino intellectuals known as illustrados. The development of this intellectual class, linked to an emerging bourgeoisie and strongly imbued with radical democratic ideals, found expression in 1888 with the creation of the journal La Solidaridad and what became known as the Propaganda Movement. It is striking that La Solidaridad was founded only forty years after the national revolutions of 1848 in Europe, and that its nationalist democratic program is broadly similar to that of Hungarian, Polish, and even Irish nationalists of the same epoch: far from being hopelessly mired in feudal backwardness, the Filipino bourgeoisie followed the same path trodden by its European counterparts only a few decades earlier.

It is therefore unsurprising that the birth of the Filipino labor movement should have many features in common with the movement in Europe, although a lack of documentation makes its beginnings difficult to follow.

The earliest seeds of the labor movement were formed in the 1850s. These were secret organizations for mutual aid and benefits of workers, similar in aim to the Friendly Societies formed by workers in Britain. Among the earliest were the Gremio de Obrero de Sampaloc, the Gremio de Escultores del Barrio Sta.Cruz, the Gremio de Carpinteros and the Gremio de Impresores y Litograficos. The Filipino labor movement can even claim to be one of the oldest in Asia.

The working class in the Philippines appeared at a time of the zenith of world capitalism, the stage of expanding imperialism. Furthermore, it appeared at a time of the victorious bourgeois revolution in Spain itself. In other words, it appeared on the ruins of feudalism on a world scale and in Spain in particular. The feudal remnants are only remnants, nothing more.

The first recorded mass working class action was conducted by members of the Gremios de Impresores in 1872 when they walked out of a government printing press in San Fernando, Pampanga on account of abuse and maltreatment by Spanish foremen and to demand better terms and conditions of work and higher wages.

The emerging Filipino workers' movement suffered not only from the relatively less developed condition of Filipino industry, but perhaps still more from their geographical isolation from the proletariat's European core. Marx in the Manifesto describes the ease with which, thanks to the railways, European workers could organize, travel, and develop their political culture. But the enormous distances involved made this less an option for Filipino workers, and this inevitably meant that the 19th century workers' movement was strongly influenced by an illustrado leadership.

These first mass actions coincided with the proletarian struggles in Europe that culminated in the first attempt of the class to seize power in Paris, France in 1871, although there is no evidence that the Filipino movement was directly aware of the momentous events of the Commune.

Since at that time the Philippine proletariat was still regrouping and learning to struggle as a class, the early workers' struggles were closely connected to Filipino nationalism, to the struggle for independent nationhood, and against colonialism. And one of the prime movers of this sense of nationalism was the Filipino clergy who were discriminated against by the Spanish-controlled Catholic Church. This is why both religion and nationalism had great influence on the early proletarian movement – an influence which survives to this day. This is an expression of the way that the consciousness of the revolutionary class lags behind the changes of objective conditions.

The close ties between unionism, nationalism, and religion, which have severely handicapped the ability of the Filipino workers to develop a revolutionary class consciousness, are exemplified by Isabelo delos Reyes, often considered the founding father of Filipino unionism. Born in 1864, delos Reyes was an illustrado nationalist journalist (in 1889 he founded El Ilocano, said to be the first newspaper written solely in a Filipino language) who was exiled to Spain in 1897 for his nationalist activities. While in Spain – such are the strange contradictions to which capitalism could give rise in those days – he was employed as Consejero del Ministerio del Ultramar (Counsellor of the Ministry for the Colonies) while at the same time taking in the influence of the radical and revolutionary thinkers of the age: on his return to the Philippines he brought with him books by Marx, Engels, Proudhon, Bakunin and other European anarchists and socialists, as well as literary works. While in Spain he wrote articles attacking the United States and its war to strip Spain of its colonies (see below), which is doubtless one of the reasons that the Spanish government allowed him to return to the Philippines in 1901.10

The close ties between unionism, nationalism, and religion, which have severely handicapped the ability of the Filipino workers to develop a revolutionary class consciousness, are exemplified by Isabelo delos Reyes, often considered the founding father of Filipino unionism. Born in 1864, delos Reyes was an illustrado nationalist journalist (in 1889 he founded El Ilocano, said to be the first newspaper written solely in a Filipino language) who was exiled to Spain in 1897 for his nationalist activities. While in Spain – such are the strange contradictions to which capitalism could give rise in those days – he was employed as Consejero del Ministerio del Ultramar (Counsellor of the Ministry for the Colonies) while at the same time taking in the influence of the radical and revolutionary thinkers of the age: on his return to the Philippines he brought with him books by Marx, Engels, Proudhon, Bakunin and other European anarchists and socialists, as well as literary works. While in Spain he wrote articles attacking the United States and its war to strip Spain of its colonies (see below), which is doubtless one of the reasons that the Spanish government allowed him to return to the Philippines in 1901.10

In February 1902, delos Reyes, together with the print union leader Herminigildo Cruz, Dominador Gomez and Lope Santos brought together more than 85 unions to found the Union Obrera Democratica (UOD), the first labor federation in the country. Its members included unions of printers, lithographers, cigar makers, tailors, mechanics, and others in various trades and occupations. At least some of these unions were apparently organized along industrial lines similar to the International Workers of the World (IWW).

In the same year, delos Reyes played a key role in founding the Philippine Independent Church11 together with the Catholic priest Gregorio Aglipay, who became the church’s first “Obispo Maximo”.12

1896-1901: nationalist revolution and imperialist war

In 1892, the rise of Filipino nationalism led to the formation of the gradualist Liga Filipina by the novelist Jose Rizal, and of the Katipunan ("The worshipful association of the sons of the people") by Andres Bonifacio, an admirer of Rizal who hoped to draw the latter into an active involvement in agitation for independence. By 1896, the Katipunan had grown to be a substantial force with between 100,000 and 400,000 members, and was strong enough to launch a nationalist revolt against Spain under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo. This first attempt ended in a negotiated stalemate which left Spain in control, but Aguinaldo and his cadres free to continue organising from their exile in Hong Kong.

It was in this context that in 1898 the United States declared war on Spain following the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana harbor (Cuba belonging to Spain at the time).13 This war allowed the US to carry off a land grab on the Philippines, which had obviously been prepared in advance and which combined brutality and hypocrisy to a truly startling degree.14

At the beginning of the war, the US presented itself as the champion of Filipino independence. The American naval commander Commodore Dewey organised Aguinaldo's return to the Philippines: the war with Spain came to an end in 1898 with American troops in Manila, while the Filipino nationalists controlled most of the rest of the country and had already declared a Filipino Republic with its provisional capital in Malolos and Aguinaldo as President. The peace was of short duration: in February 1899, US troops in Manila provoked the outbreak of a new war, this time against the fledgling Filipino Republic, which was to end in 1902 after the defeat of the Filipino army by a vastly superior American force, and a protracted and brutal guerilla campaign that left 22,000 Filipino soldiers and more than 500,000 civilians dead. The Philippines was thus given a taste of the delights of "civilisation" and "democracy": in just three years, the USA killed more Filipinos that the Spaniards had done in 300.15

All the more remarkable, in this context, is the third recorded strike of March 1899 by the printers union led by Herminigildo Cruz, demanding increased wages and an end to the abuses of a press superintendent. The mass action was directed at the management of the nationalist government’s printing press in Malolos, Bulacan, where the La Independencia was printed. Editor and General Antonio Luna intervened and arranged for a 25% pay raise to workers.

We can appreciate the symbolism of this strike, at the turn of the century, being directed not against the old or new colonial power but against the rising national democratic bourgeoisie that was supposed to be a "reliable ally" of the workers' movement. Filipino labor was confronted from the outset by national government, nationalist movements, and brutal repression by the colonial power.

1898-1930s: Under US colonial power

Given its own anti-imperialist ideology (which for America meant the opposition to the fully colonial structures set up by the old European empires, especially the British), the USA could hardly transform the Philippines into a colony in the old style. Hence alongside US military occupation under the authority of an American Governor-General, the 1902 Philippine Bill adopted by the US Congress provided for the creation of an elected legislature: the first elections were held in 1907 and led to a resounding victory for the Nacionalista Party.16

The American ruling class was united in its desire to preserve its commercial, industrial, and military strategic interests in the Philippines, but was divided on how best to do so: by continual direct rule and military occupation, or through nominal independence, with client status ensured by treaties and the maintenance of US military bases in the country. By 1934, following the election of Roosevelt's Democrat "New Deal" administration in 1933, the second option was chosen and the Tidings-McDuffie Act of that year created the Philippine Commonwealth, which was to become fully independent after a ten-year transition period. Manuel Quezon was elected as the first President of the Philippines under the Act, in 1935.

Returning to August 1902 and the beginning of the American occupation, when Isabelo delos Reyes was arrested and imprisoned for charges of sedition and rebellion, Dominador Gomez took over and changed the name of UOD to Union Obrera Democratica de Filipinas (UODF). But Gomez was also arrested for sedition and illegal association in 1903 after thousands of workers marched on May 1, 1903 demanding national independence.

Gomez articulated the orientation of Philippine unionism in a speech delivered as leader of the Union Obrera Democratica:

“The banner of UOD is dynamic nationalism against any form of imperialism, against oppression.”

And on May 1, 1903, in a workers rally of Union Obrera Democratica de Filipinas Gomez declared:

“We are not against capitalists (…) What we are against is the practice of the capitalists robbing the workers of the product of their sweat by not giving what is due to them…”17

If the nationalist unions were not against capitalism, then neither was the American colonial regime against trades unions as such, provided that they were tightly controlled by the state, and inspired by the most conservative forces of the workers’ movement in the United States. This two-pronged strategy led to the entry of the American Federation of Labor led by Samuel Gompers into the Philippines, where it gave support to the Union del Trabajo de Filipinas (UTF), set up by Lope K. Santos.18

At the same time, the Bureau of Labor (BOL) was set up (June 10, 1908) to organize the legalization and regulation of trade unionism throughout the country. The Bureau, under the Department of Commerce and Police, was tasked to regulate and provide information on the labor force and market, and to settle disputes between labor and employers. The US also gave the go-ahead for the Philippine Assembly to recognize May 1st as a national holiday, to appease the class anger of the workers.

The US attempt to control the union movement was not completely successful, and some unions continued to have close ties to the nationalist cause. This was notably the case with the Union de Impresores de Filipinas (UIF) which participated in the UODF; when the UODF was dissolved in 1903 and reorganised as the Congreso Obrero de Filipinas (COF), the UIF's president Crisanto Evangelista went on to play a leading role in the new federation. As a leader of COF, he was included in the Independence Mission sent to the USA in 1919 along with the then rising leader of the Nacionalista Party, Manuel Quezon. While in the US, Evangelista was ignored by the AFL, but did attend a convention of the International Workers of the World.19