July 2013

- 1541 reads

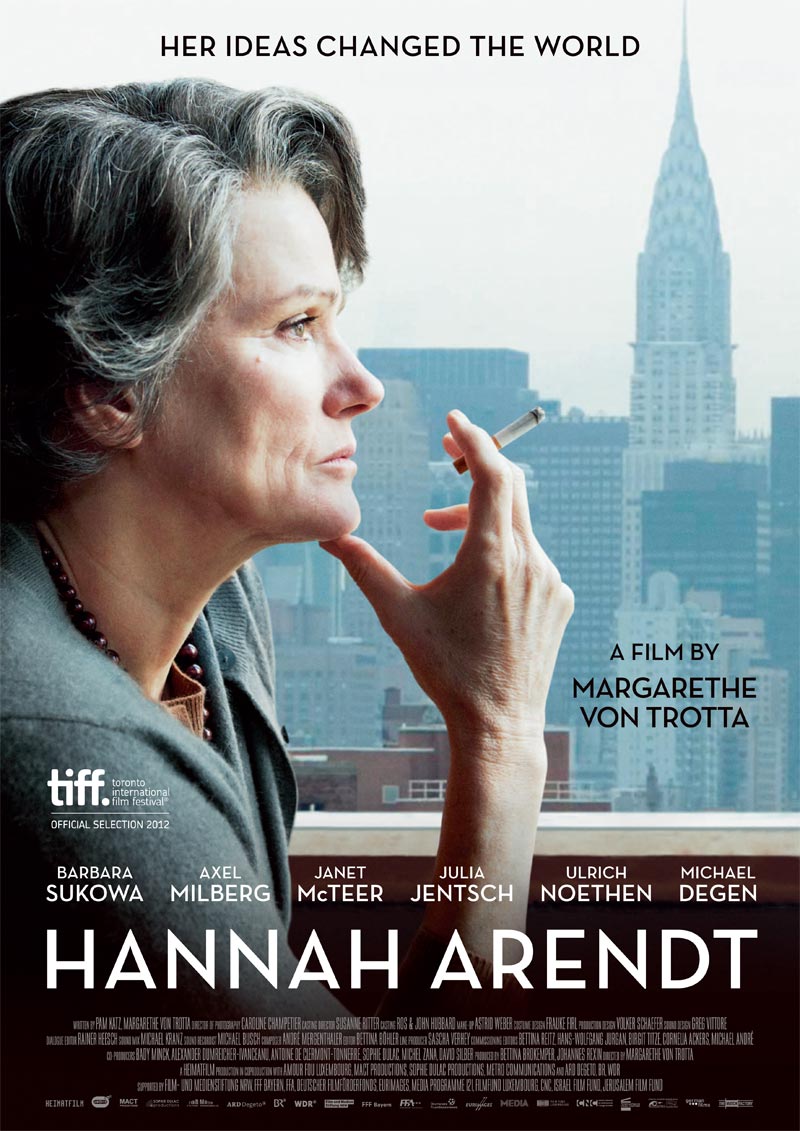

Hannah Arendt: in praise of thought

- 2861 reads

Germany's tormented 20th century history is rich in dramatic and terrible themes, as a number of successful films that have hit the screens over the last few years demonstrate: The pianist, for example1 (on the Warsaw ghetto), or Goodbye Lenin and The lives of others (on East Germany and the fall of the Berlin Wall). The producer Margerete von Trotta has already drawn inspiration several times from these deep waters, and has not hesitated to deal with some difficult subjects: witness Two German sisters (Die Bleieme Zeit, 1981), a dramatised version of the life and death (in Stammheim prison, in circumstances which were never completely clarified) of the Red Army Fraction terrorist Gudrun Ensslin; a biopic of Rosa Luxemburg (1986); Rosenstrasse (2003), on a demonstration against the Gestapo in 1943 of German women protesting at the arrests of their Jewish husbands. In her new film, Hannah Arendt (2012 in Germany, 2013 in the USA and Britain), von Trotta returns to the subject of the war, the Shoah, and nazism, through an episode in the life of the eponymous German philosopher, remarkably played by Barbara Sukowa, who also played the role of the young Rosa Luxemburg twenty years ago.

Germany's tormented 20th century history is rich in dramatic and terrible themes, as a number of successful films that have hit the screens over the last few years demonstrate: The pianist, for example1 (on the Warsaw ghetto), or Goodbye Lenin and The lives of others (on East Germany and the fall of the Berlin Wall). The producer Margerete von Trotta has already drawn inspiration several times from these deep waters, and has not hesitated to deal with some difficult subjects: witness Two German sisters (Die Bleieme Zeit, 1981), a dramatised version of the life and death (in Stammheim prison, in circumstances which were never completely clarified) of the Red Army Fraction terrorist Gudrun Ensslin; a biopic of Rosa Luxemburg (1986); Rosenstrasse (2003), on a demonstration against the Gestapo in 1943 of German women protesting at the arrests of their Jewish husbands. In her new film, Hannah Arendt (2012 in Germany, 2013 in the USA and Britain), von Trotta returns to the subject of the war, the Shoah, and nazism, through an episode in the life of the eponymous German philosopher, remarkably played by Barbara Sukowa, who also played the role of the young Rosa Luxemburg twenty years ago.

Hannah Arendt was born into a Jewish family in 1906. As a young student, she attended the classes of the philosopher Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a brief but intense love affair. The fact that she never disowned either the relationship or Heidegger himself, despite the latter's joining the NSDAP2 in 1933 was to be harshly criticised later; her ties with Heidegger and his philosophy were undoubtedly complex, and would almost merit a book in themselves, and the flashbacks to her encounters with Heidegger are perhaps the least successful in the film, the only scenes where von Trotta seems less sure of her film's theme: the "banality of evil".

Arendt fled Germany in 1933 with Hitler's coming to power, and moved to Paris where she worked in the Zionist movement despite her critical attitude towards it. It was in Paris that she married, in 1940, her second husband Heinrich Blücher. Following Germany's invasion of France she was interned by the French state in the camp of Gurs, but managed to flee and – not without difficulty – reached the United States in 1941. Penniless on her arrival, she managed to earn her living and finally succeeded in winning an appointment to the prestigious Princeton University (she was the first woman to be accepted as a professor by Princeton). By 1960, when the film opens, Arendt was a respected intellectual and had already published two of her most famous works: The origins of totalitarianism (1951) and The human condition (1958). Although she was certainly not a marxist, she was interested by Marx's work, and by that of Rosa Luxemburg.3 Her husband Heinrich had been a Spartakist, then a member of the opposition to the Stalinisation of the KPD during the 1920s, joining Brandler and Thalheimer in the KPD-Opposition (aka KPO) when they were excluded from the party.4 The film makes a passing reference to Heinrich's party membership: we learn from one of the couple's American friends that "Heinrich was with Rosa Luxemburg to the end". And Arendt's philosophical work, especially her analysis of the mechanisms of totalitarianism remains relevant to this day. Her rigorous thought and her integrity allowed Arendt to pierce the clichés and commonplaces of her epoch's ruling ideology: she disturbed by her honesty.

The film's first moments evoke Adolf Eichmann's kidnapping in Argentina by the Mossad. Under the Nazi regime, Eichmann had occupied several important positions, organising first the Jews' expulsion from Austria, then the logistics of the "Final Solution", in particular the transport of European Jews to the death camps of Auschwitz, Treblinka, and others. The intention of David Ben-Gurion, Prime Minister of Israel and so responsible for the Mossad operation, was clearly to mount a show trial which would cement the foundations of the young state, and where the Jews themselves would judge one of the authors of their genocide.

On learning of the coming Eichmann trial, Arendt volunteered to report on the trial for the literary review The New Yorker. Her detailed and meticulous report on the trial appeared first as a series of articles, then in book form under the title Eichmann in Jerusalem: a report on the banality of evil. The publication caused a huge scandal in Israel and even more in the United States: Arendt was subjected to a violently hostile media campaign – "self-hating Jew" and "Rosa Luxemburg of nothingness" were only two of the more sober epithets aimed at her. She was asked to resign her university position, but refused. This period, the evolution of Arendt's thinking and her reaction to the media campaign, provide the material for the film. And when you think about it, it's a tall order to make a film of the contradictory and sometimes painful evolution of a philosopher's thinking, without trivialising it – and von Trotta and Sukowa rise to the challenge with brio.

Why then did Arendt's report create such a scandal?5 Up to a point, such a reaction was understandable and even inevitable: although Arendt wields criticism like scalpel, with all the skill of a surgeon, but for many the war and the abominable suffering of the Shoah were still too close, the trauma too recent, to be able to distance themselves from events. But the loudest voices were also the most interested: interested above all in drawing a veil of silence over the uncomfortable truths that Arendt's critique revealed.

Arendt cut to the quick when she took apart Ben-Gurion's attempt to make a show of Eichmann's trial, to justify Israel's existence by the Jews' suffering during the Shoah. For this to work, Eichmann had to be a monster, a worthy representative of the Nazis' monstrous crimes. Arendt herself expected to see a monster in the dock, but the more she observed him, the less she was convinced, not of his guilt but of his monstrosity. In the trial scenes, von Trotta places Arendt not in the tribunal itself, but in a press room where the journalists watch the trial over CCTV. This device allows von Trotta to show us, not an actor playing Eichmann, but Eichmann himself; like Arendt, we can see this mediocre man (Arendt uses the term "banality" in its sense of "mediocrity"), who has nothing in common with the murderous madness of a Hitler, or the no less mad coldheartedness of a Goebbels (as they have been brilliantly interpreted by Bruno Ganz and Ulriche Mathes in Downfall). On the contrary, we are confronted with a petty bureaucrat whose intellectual horizon barely extends beyond the walls of his office and its good order, and whose perspectives are limited to his hopes for promotion and bureaucratic rivalries. Eichmann is not a monster, is Arendt's conclusion: "it would have been very comforting indeed to believe that Eichmann was a monster (…) The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal" (p274).6 In short, Eichmann's crime was not to have been responsible for the Jews' extermination in the same way as Hitler, but to have abdicated his capacity for thinking, and to have acted legally and with a quiet conscience as a mere cog in a the totalitarian machine of a criminal state. The undoubted "good sense" of "prominent personalities" served as his "moral guide". The Wannsee conference (which set in place the operational mechanisms of the "Final Solution") was thus "a very important occasion for Eichmann, who had never before mingled socially with so many 'high personages' (…) Now he could see with his own eyes and hear with his own ears that not only Hitler, not only Heydrich or the 'sphinx' Müller, not just the SS or the Party, but the elite of the good old Civil Service were vying and fighting with each other for the honor of taking the lead in these 'bloody' matters" (p111-2).

Arendt explicitly rejects the idea that "all Germans are potentially guilty", or "guilty by association": Eichmann deserved to be executed for what he had done himself (though his execution would hardly bring the millions of victims back to life). That said, her analysis is a courageous slap in the face for the anti-fascist ideology which has become official state ideology, notably in Israel. In our view, the "banality" that Arendt describes is that of a world – the capitalist world – where human beings, reified and alienated, are reduced to the status of objects, commodities, cogs in the machine of capital. This machine is not a characteristic of the Nazi state alone. Arendt reminds us that the policy of "Judenrein" (making a territory "Jewless") had already been explored by the Polish state in 1937, before the war, and that the thoroughly democratic French government, in the person of its foreign minister Georges Bonnet, had envisaged the expulsion to Madagascar of 200,000 "non-French" Jews (Bonnet had even consulted his German opposite number Ribbentrop for advice on the subject). Arendt also points out that the Nuremberg tribunal is nothing less than a "victors' tribunal", where the judges represent countries which were also responsible for war crimes: the Russians guilty of the deaths in the gulags, the Americans guilty of the nuclear bombardment of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nor is Arendt tender with the state of Israel. Unlike other reporters, she highlights in her book the irony of Eichmann's trial for race-based crimes by an Israeli state which itself incorporates racial distinctions into its own laws: "rabbinical law rules the personal status of Jewish citizens, with the result that no Jew can marry a non-Jew; marriages concluded abroad are recognized, but children of mixed marriages are legally bastards (…) and if one happens to have a non-Jewish mother he can neither be married nor buried". It is indeed a bitter irony that those who escaped from the Nazi policy of "racial purity" should have tried to create their own "racial purity" in the Promised Land. Arendt detested nationalism in general and Israeli nationalism in particular. Already in the 1930s, she had opposed Zionist policy and its refusal to look for a mode of life in common with the Palestinians. And she did not hesitate to expose the hypocrisy of the Ben-Gurion government, which publicised the ties between the Nazis and certain Arab states, but remained silent about the fact that West Germany continued to shelter a remarkable number of high-ranking Nazis in positions of responsibility.

Another object of scandal was the question of the "Judenrat" – the Jewish councils created by the Nazis precisely with the aim of facilitating the "Final Solution". It occupies only a few pages of the book, but it cuts to the quick. Here is what Arendt has to say about it: "Wherever Jews lives, there were recognized Jewish leaders, and this leadership, almost without exception, cooperated in one way or another, for one reason or another, with the Nazis. The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and a half and six million people (…) I have dwelt on this chapter of the story, which the Jerusalem trial failed to put before the eyes of the world in its true dimensions, because it offers the most striking insight into the totality of the moral collapse the Nazis caused in respectable European society" (p123). She even revealed an element of class distinction between the Jewish leaders and the anonymous mass: in the midst of the general disaster, those who escaped were either sufficiently rich to buy their escape, or sufficiently visible in the "international community" to be kept alive in Theresienstadt, a kind of privileged ghetto. The relationships between the Jewish population and the Nazi regime, and with other European populations, were much more complicated than the war victors' official manichean ideology was prepared to admit.

Nazism and the Shoah occupy a central place in modern European history, even more today than in the 1960s. Despite the best efforts of the authors of The black book of communism, for example, Nazism remains today the "ultimate evil". In France, the Shoah is an important part of the school history programme, along with the French Resistance, to the exclusion of almost any other consideration of the Second World War. And yet on the level of simple arithmetic, Stalinism was far worse, with the 20 million dead in Stalin's gulag and at least 20 million dead in Mao's "Great leap forward". Obviously, this owes a good deal to opportunist calculation: the descendants of Mao and Stalin are still in power in China and Russia, they are still people with whom one can and must "do business". Arendt does not deal directly with this question, but in a discussion of the charges against Eichmann, she insists on the fact that the Nazis' crime was not a crime against the Jews, but a crime against all humanity in the person of the Jewish people, precisely because it denied to the Jews their membership of the human species, and transformed these human beings into an inhuman evil to be eradicated. This racist, xenophobic, obscurantist aspect of the Nazi regime was clearly proclaimed, which indeed is why a part of the European ruling class, and of the peasant and artisan classes ruined by the economic crisis, could get along with it so comfortably. Stalinism on the contrary always claimed to be progressive: it could still sing that "the Internationale shall be the human race", and indeed this is why right up to the destruction of the Berlin Wall, and even afterwards, ordinary people could continue to defend the Stalinist regimes in the name of a better future to come.7

Arendt's major point is that the "unthinkable" barbarity of the Shoah, the mediocrity of the Nazi bureaucrats, is the product of the destruction of an "ability to think". Eichmann "does not think", he executes the orders of the machine, and does his job diligently and conscientiously, without any qualms, and without making the connection with the horror of the camps – of which he was nonetheless aware. In this sense, von Trotta's film should be seen as an elegy to critical thought.

Hannah Arendt was not a marxist, nor a revolutionary. But by posing questions which undermine official anti-fascist ideology, she is the enemy of commonplace conformism and the abandonment of critical thought. Her analysis has the merit of opening a reflexion on the human conscience (rather in the same way as the work of the American psychologist Stanley Milgram on the mechanisms of the "submission to authority" amongst torturers, dramatised in Henri Verneuil's film I comme Icare).

The publicity given to Arendt's work by the democratic bourgeoisie and its intelligentsia – for whom she has become something of an icon – is not innocuous. The recuperation of her analysis of totalitarianism clearly aims at establishing a continuity between Bolshevism and the Russian revolution of 1917, and the totalitarian machine of the Stalinist state: Stalin was only Lenin's executor, the moral being that proletarian revolution can only lead to totalitarianism and new crimes against humanity. This is what some established bourgeois ideologues like Raymond Aron have not hesitated to exploit Arendt's analysis of the Stalinist state's totalitarianism to feed their campaigns for the Cold War and the "collapse of communism" following the break-up of the USSR.

Hannah Arendt was a philosopher, and as Marx said "The philosophers have so far only interpreted the world. The point however, is to change it". Marxism is not a "totalitarian" doctrine but the theoretical weapon of the exploited class for the revolutionary transformation of the world. And this is why only marxism is truly able to integrate the contributions of art and science, and of past philosophers like Epicurus, Aristotle, Spinoza, Hegel... as well as those of our own time like Hannah Arendt, with her profound and critical view of the contemporary world, and her elegy to thought.

Jens

1See our critique of the film in n°113 of the International Review (https://en.internationalism.org/ir/113_pianist.html [1])

2The Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (Nazi party)

3In 1966 Arendt reviewed JP Nettl's biography of Luxemburg in the New York Review of Books. In this article, she lashed both the Weimar and the contemporary Bonn governments with the scourge of her critique, declaring that the murders of Luxemburg and Liebknecht were carried out "under the eyes and probably with the connivance of the Socialist regime then in power (…) That the government at the time was practically in the hands of the Freikorps because it enjoyed 'the full support of Noske,' the Socialists’ expert on national defense, then in charge of military affairs, was confirmed only recently by Captain Pabst, the last surviving participant in the assassination. The Bonn government - in this as in other respects only too eager to revive the more sinister traits of the Weimar Republic - let it be known (through the Bulletin des Presse-und Informationsamtes der Bundesregierung) that the murder of Liebknecht and Luxemburg was entirely legal, 'an execution in accordance with martial law.' This was more than even the Weimar Republic had ever pretended...".

4The KPO was one of the oppositions to Stalinism which never fully broke with it because, like Trotsky, they were unable to accept the idea of a counter-revolution in Russia.

5For French speakers, there is an interesting documentary made up of radio interviews of the participants in the controversy podcast by France Culture: Hannah Arendt et le procès d'Eichmann [2]

6The quotes are taken from the the Penguin edition published in 2006 with an introduction by Amos Elon.

7See for example this fascinating documentary series (in German and English) on life in the ex-DDR [3].

Historic events:

Geographical:

- Israel [6]

General and theoretical questions:

- Fascism [7]

People:

- Hannah Arendt [8]

- Heinrich Blücher [9]

- Adolf Eichmann [10]

Rubric:

"Raped by State"

- 1519 reads

“I feel that I have been raped by the state”.

This powerful statement sums up the real nature of the recent revelations concerning the use of undercover police to penetrate and manipulate various protest movements. It was made by one of the women with whom various agents of the Special Demonstrations Squad (SDS) deliberately established relationships in order to gain wider acceptance in the protest movements they wanted to infiltrate. The motto of the SDS was “by all means necessary” and this sums up the general attitude of the capitalist state to maintaining its dictatorship. Human feelings and dignity mean absolutely nothing to the ruling class and their servants.

This was further underlined by the revelations concerning the efforts of SDS and Special Branch agents under the direction of the Metropolitan Police to discredit the family of murdered teenager Stephen Lawrence. Only weeks after the brutal racist murder of this teenager in 1993, an SDS agent was assigned to uncover anything that could discredit the Lawrence family. Special Branch used the police family liaison officer - who was supposed to befriend the family - to spy on all those who came to the family’s home.

The cold and calculating way in which various state agencies use and abuse people is shocking. However, this is the nature of the rule of capital. Nothing is too sacred to be ground under the iron heel of the state. The Lawrences’ grief and anger at the police’s racism showed the reality behind the image of the police in capitalist democracy. The women used by the SDS, had the audacity to “want to bring about social change” as one of them said. A questioning of the system, no matter how mild, is something that the state cannot tolerate.

There has been a whole frenzy from politicians, journalists, and even the police, about ‘rogue’ units, abuses of the democratic system, and the need for democratic control of the police. We heard exactly the same piteous laments two years ago following the exposure of the undercover activity of the agents of the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOI) who had infiltrated various anarchist, animal rights and environmental groups in the 2000s[1] Once the noise died down about these ‘abuses of police powers’, it was rapidly replaced by calls for more police powers to carry out systematic surveillance of all telecommunications. It is the same now: despite these revelations, we hear calls for more police powers to ‘fight domestic extremism’.

Hypocritical cant from the politicians

The politicians’ talk about abuses of democracy is as devious as the actions of the SDS, because it seeks to hide the true nature of the capitalist state and its democratic window dressing: “So-called democracy, i.e. bourgeois democracy, is nothing but the veiled dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. The much-vaunted ‘general win of the people’ is no more a reality than ‘the people’ or ‘the nation’. Classes exist and they have conflicting and incompatible aspirations. But as the bourgeoisie represents an insignificant minority it makes use of this illusion, this imaginary concept, in order to consolidate its rule over the working class. Behind this mask of eloquence it can impose its class will” (Platform of the Communist International, 1919).

The imposition of this "class will" is precisely the role of secret police units such as the SDS and the NPOI, along with Special Branch, MI5, etc. The Special Demonstrations Squad was formed in the late 60s in order to infiltrate the growing protest movements, and then expanded into infiltratinging animal rights and environmental groups, anarchist and Trotskyist groups in the 80s and 90s. The SDS was part of the Metropolitan Police. In 1999 the NPOI was set up to coordinate and organise nationwide networks of undercover operations and surveillance, The NPOI broadened its remit to include “campaigners against war, nuclear weapons, racism, genetically modified crops, globalization, tax evasion, airport expansion and asylum law, as well as those calling for reform of prisons and peace in the Middle East”, all of which are now defined as 'domestic extremists'[2]. Thus, anyone who opposes or questions what the state does is now an 'extremist' and implicitly linked to 'Muslim' extremists and thus terrorism. This expresses the state’s concern about growing social discontent, even when confined to relatively harmless forms of protest. However, involvement in such movements can and does lead to a wider questioning of the system and the state wants to be able to follow and counter such questioning. It also wants to manipulate such movements in order to generate fear of any form of dissent.

The extent that the state is willing to go to manipulate such groups has been demonstrated in the recent book Undercover: the true story of Britain’s secret police. It claims that the SDS infiltrated an agent into the anarcho-syndicalist Direct Action Movement between 1990-93; two others were sent into the anarchist group Class War, one of them working closely with MI5 who were investigating Class War at the time. The authors say that the NPOI is currently running between 100 and 150 agents. The book also argues that the NPOI has officers or links with polices forces in cities and towns across the country, and that they use infiltration in small local protest groups in order to get agents into national groups and movements. The NPOI itself was placed under the management of the National Domestic Extremism Team in 2005, which the Labour government set up to centralise the various domestic forces of repression.

This centralisation was put to full use in 2011 when hundreds of people who had been arrested, stopped or filmed on demonstrations received letters from the Metropolitan Police, warning them that if they attended the November student demonstration in London they would be arrested.

These claims are certainly informative but unless understood in the context of the dictatorship of capital it can lead to paranoia and mistrust.

One of the reasons for the success of these state agencies in penetrating various movements has been the naivety of those involved, a result of the weight of democratic illusions. The idea that ‘the state is not interested in us because we are too small’ is very widespread, not only amongst environmentalists but even amongst revolutionary groups and individuals. There are also illusions that the state would never infiltrate someone for years, even allowing them to live with a militant. There needs to be a conscious effort to understand and draw the lessons from the actions of these agents, not to become paranoid, but to be aware that the state is interested in any organisation or individual who is against this system, and will use any means necessary against them.

This can be seen in the example of a 69 year old GP place on the list of ‘domestic extremists’ because of his involvement in a campaign to stop ash from Didcot power station (Oxfordshire) being dumped in a nearby lake!

Confronted with the state’s complete disregard for the slightest aspect of human dignity, its willingness to violate even our bodies in order to defend itself, we can only express our solidarity with those women who were used by the state but who are now openly talking about what happened to them, even to the extent of meeting their abusers to challenge what they did. But above all we have to be conscious that the ruling class will go to any length to undermine the revolutionary alternative and reject any illusion that their state can be controlled, reformed or made more accountable. It is our main enemy in the class war and our goal is to destroy it once and for all.

Phil 2/7/13

[1]. ‘Methods of infiltration by the democratic state’, https://en.internationalism.org/worldrevolution/201102/4201/methods-infi... [11].

[2]. Rob Evans and Paul Lewis, Undercover: The true story of Britain’s secret police, Faber and Faber, 2013, p 203

Recent and ongoing:

- State repression [12]

Rubric:

Chancellor’s careful but relentless development of austerity

- 1383 reads

It is one of the ironies of the spending review that when so much of the pain is directed towards benefits, George Osborne should claim that the well-off will suffer most. Next year the chancellor will announce a 5 year benefit cap, excluding pensions. Welfare payments will be harder to claim - for instance anyone losing a job will have to wait 7 days before claiming jobseekers allowance. This will be particularly hard on those on the lowest pay scales or in precarious work. This 7 day wait will save £245m, a very modest amount compared to the £11.5 billion which will be spent on more frequent surveillance of the unemployed (meetings every week instead of less frequently, compulsory English lessons, etc). Ed Balls, by contrast, claims that he would like to spend the money on providing a job for every young unemployed person. While Osborne is reminding us that the point of laying workers off is to save capital the cost of maintaining them at all, it seems Balls wants us to forget that the whole point of capital employing anyone, young or old, is to extract surplus value, to make a profit.

Public sector workers are also going to suffer from the spending plans: pay will continue to be curbed, pay progression seniority payments ended, and 144,000 can expect to lose their jobs. While the NHS and schools will not have their cash budgets cut, this has to be seen in the context of growing need. Health needs (so-called ‘demand’) increases 4% a year due to demographic changes and innovation. £3bn of the health budget will be shared with local authority social care, and we know how squeezed the local authorities are. Hospital stays and admissions are being cut. Whole layers of health service workers are employed or incentivised to keep people out of hospital as much as possible – while, of course, remaining responsible for admitting them to hospital when necessary. Others have the job of cutting the prescription budgets. At the same time, previous levels of social care - put in place when the economy was short of labour and women and immigrants were being encouraged into the workforce (in the 50s and 60s particularly) - are being dismantled or charged to the recipients, with much more responsibility falling on the relatives whether or not they are capable of taking it on.

How long will these cuts go on?

The UK economy, regardless of quibbles about single, double or triple dip recession, remains to recover from the 2007/8 recession, with GDP still 3 or 4% below the previous peak. This creates a problem for an economy trying to reduce the proportion of direct state spending – from 46% to 40% as Osborne intends – and pay back debts that were greatly increased at the time of the banking crisis. Hence the IMF reminder earlier in the year that this will not be achieved without growth. This puts any state on the horns of a dilemma, with the need to both rein in spending and ease up the availability of money to encourage growth. It’s a bit like walking in two opposite directions at once. It was left to Danny Alexander to announce the bulk of the capital spending plans for road and rail, housing and schools, while day to day spending is restricted. How well this spending will encourage growth in the medium term we will wait and see. More roads suggest a promising growth in CO2 emissions at any rate.

Other spending beneficiaries give us more idea of what the state intends. Extra spending for spying suggests an interest in both internal and external security – fundamentally to further Britain’s imperialist interests abroad and to maintain social order at home. Ring-fencing overseas aid also suggests the importance of pursuing the national interest abroad – and in a way less likely to cause unpopularity at home than foreign military adventures such as Iraq.

The latest scapegoats

A few years ago it was the bankers that were blamed for the crisis, pilloried by press and politicians alike for their excessive pay and bonuses. Now it seems it is the unemployed and benefit claimants who are responsible for the national debt. The bankers provided a good scapegoat for the crises, particularly when it took the form of the credit crunch. They had the advantage of being rich, and right at the centre of the storm, as well as distracting us from asking questions about the nature and role of capitalism itself. But the demonisation of the unemployed, and the lowest paid and most precarious workers who also rely on benefits such as tax credit or housing benefit, has a longer term aim in persuading us to accept attacks on these benefits, with their horrendous effects on the quality of life of an important part of the working class.

The ruling class are playing up any kind of division they are able to impose on the working class, not only between the ‘hard working’ and the ‘skivers’ (i.e. employed and unemployed), but also between public and private sector employees. This divide is important when the state is involved in attacking the pay and conditions of those employed in the public sector, particularly those usually held in high esteem such as teachers and nurses. Hence the media attention to scandals in hospital care, undercover reporters sent to see what abuses they can detect and film. But not a word on the cuts and increasing demands that make humane care so difficult.

These campaigns tell us much of the direction of the austerity measures the ruling class is bringing in, centralised through its state. That they are cautious, that they prepare each attack with a campaign of vilification, shows just how much they are aware of the possibility of working class resistance to further austerity.

Alex 13/7/13

General and theoretical questions:

- Economic crisis [13]

Rubric:

Day of discussion: Impressions of a participant

- 2084 reads

We are publishing below impressions of our Day of Discussion held in London on 22 June, written for her own blog by a comrade who posts on our internet forum but who had not previously met the ICC ‘face to face’. The presentations given on the day can be found on this thread on our forum [14]. We intend to group together and publish all the presentations and write ups of the discussions in one file in the near future.

The original piece can be read on the contributor's blog here:

Well yesterday I went to the Day of Discussion put on by the International Communist Current. They are a left-communist [16]group. People reading this might not know what that is (and probably don’t tbf) so I will explain quickly what my understanding about the communist left is.

The communist left basically originated in the Russian revolution, supporting Lenin and the Bolshevik Party initially and rapidly getting disillusioned. They didn’t make Lenin particularly happy. They were the ones that Lenin was on about when he wrote his notorious “Left-wing communism – an infantile disorder [17]” pamphlet, because they were complaining that the revolution was degenerating (which it was) becoming more and more like capitalism again and becoming more and more authoritarian – basically coming to resemble, what we know now as state capitalism or “stalinism” betraying the russian workers they claimed to lead and distorting Marxism into an authoritarian doctrine. One of the founders of it was a guy called Herman Gorter who wrote an “open letter to Comrade Lenin [18]“.

They think that the Russian revolution degenerated back before Lenin’s death (and also that nationalisation etc is not necessarily a step on the way to socialism or even necessarily an improvement to “normal” capitalism) rather than the Trotskyist view which was that this only happened after Lenin’s death and that what happened in the Soviet union and other “communist” countries was that they were “deformed workers’ states” despite the fact that they were a nightmare for huge numbers of working class people. And therefore that despite the criticisms Trotskyists had of them somehow their governments were usually worth defending.

Lenin and Trotsky were mates and Trotsky had a high position in the Bolshevik hierarchy and he could never bring himself to see the full extent of the wrongness of the Soviet regime.

The communist left on the other hand were closer to the anarchist position in that they believed that the revolution started going very very wrong within a year or two of 1917. There’s loads of stuff, Kronstadt, the fact that they made it very difficult for workers to go on strike, they introduced one-man management (bringing back the old bosses that the workers had overthrown during the revolution)

“what? why do you want to go on strike eh, we have socialism now and “the working class” are now in power?”

I was really pleasantly surprised by the meeting. I had expected it to be a really small meeting full of party hacks but actually around 20 people were there and probably around half of them weren’t ICC members but from other organisations or not in an organisation at all. And most of them were pretty normal and had a good sense of humour (no offence but you’d have to have a good sense of humour to be part of the communist left!).

The topic of the meeting was “why is it so difficult to struggle against capitalism”. I’ve got my own ideas (some of which were sadly reflected in some of my observations that day, although i don’t think this was intentional) and in my next post I’ll do like a summary of that debate.

The good points were that I didn’t see any sectarianism on the level of what you would get in trot groups (there was one guy who made a dig about the SPGB which was out of order and he was swiftly shouted down), not many weirdo party hacks, most of the participants seemed to want to learn from other people rather than just promoting the views of their own organisation. And people with opposing views weren't shouted down or told they were wrong.

There was also free food.

The bad points could apply to most left-wing organisations. One of the problems is that they assume a certain level of knowledge about terms like “decomposition” and things like that but they are hardly the only offenders for that. It also wasn’t as well publicised as it could have been and most of the people there (although not all) seemed to have all been involved in the “mileu” for a long time rather than people who had never been involved in politics. There were a few young people there but not many and some of the contributions at times seemed to be a bit vanguardist talking about how “we” will do this and that and “we” will integrate people into productive communism etc. I dont think that’s exactly what was meant but that’s how it came across but at least they were willing to take criticisms when I and others pointed this out.

I was actually really pleasantly surprised. I have a lot of differences with the ICC, one of them is my opinion about anti-fascism, as they see it purely as a distraction from class struggle. I can see their point but I still think that it is part of the class struggle. that is the main one i guess.

The other criticism I have got is about their papers, as I said they do assume a level of knowledge, it seems a bit stupid but there should be more pictures in the papers and sometimes the print is too small and a bit hard to read because the articles are so long.

I did pick up a lot of their literature, their paper “World Revolution” their theoretical journal “International Review” and a book called “Communism is not a nice idea but a material necessity”, and a pamphlet called “Trade unions against the working class”. I have read some of the anti-trade union pamphlet online but i find it easier to read books on paper rather than online.

The other left communist organisation that was there. the ICT, printed some articles in their magazine that were about Bordiga and Damen and I think some basic introductions to these people could be useful rather than immediately assuming that everyone knows who they are already (because i know who bordiga is but not really familiar with his writings or that much apart from that really) but that is part of my point about language I suppose.

The other bad thing was the fact that it was in London and therefore cost a lot for me to get to (which i can afford at the moment, but I probably won’t always be able to). I’d love to be able to organise or get involved in something that’s more local but at the moment I don’t have the time and I think a lot of people probably feel the same way.

I am quite wary of getting involved in any organisations these days but I was glad I went to this because it’s very rare that I actually get to discuss anything with people these days apart from the internet. And afterwards we all had a drink together and went for a curry, I thought it was great that we got a chance to talk about stuff afterwards and get to know each other a bit as people!

Life of the ICC:

- Public meetings [19]

Recent and ongoing:

- Day of Discussion [20]

Rubric:

Egypt highlights the alternative: socialism or barbarism

- 1986 reads

Hundreds of thousands, even millions, have come out to protest against all manner of ills: in Turkey, the destruction of the environment by unrestrained ‘development’, authoritarian religious meddling in personal lives, the corruption of the politicians; in Brazil, transport fare increases and the diversion of wealth into prestige sporting events when health, education, housing and transport are left to fester – and the corruption of the politicians. In both cases, the initial demonstrations were met by brutal police repression which served only to widen and deepen the revolt. And in both cases, the revolts were spearheaded not by the ‘middle classes’ (for the media, that’s anyone who has a job), but by the new generation of the working class, who may be educated but have little prospect of finding stable employment, who may be living in ‘emerging’ economies but for whom a developing economy means mainly the development of social inequality and the repulsive affluence of a tiny elite of exploiters.

In June and July it was again the turn of Egypt to see millions on the street, returning to Tahrir Square which was the epicentre of the 2011 rebellion against the Mubarak regime. They too were driven by real material needs, in an economy which is not so much ‘emerging’ but stagnating or even regressing. In May, a former finance minister of the country and one of its leading economists warned in an interview with The Guardian that “Egypt is suffering its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, In terms of its devastating effect on Egypt’s poorest, the country’s current economic predicament is at its most dire since the 1930s”. The article goes on to say that:

“Since the fall of Hosni Mubarak in 2011, Egypt has experienced a drastic fall in both foreign investment and tourism revenues, followed by a 60% drop in foreign exchange reserves, a 3% drop in growth, and a rapid devaluation of the Egyptian pound. All this has led to mushrooming food prices, ballooning unemployment and a shortage of fuel and cooking gas… Currently, 25.2% of Egyptians are below the poverty line, with 23.7% hovering just above it, according to figures supplied by the Egyptian government”[1].

The ‘moderate’ Islamist government led by Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood (backed by the majority of the ‘radical’ Islamists) has rapidly proved itself to be no less corrupt and cronyist than the old regime, while its attempts to impose its stifling Islamic ‘morality’ has, as in Turkey, created huge resentment among the urban young.

But while the movements in Turkey and Brazil, which are in practice directed against the power in place, have created a real sense of solidarity and unity among all those taking part in the struggle, the situation in Egypt is faced with a much more sombre prospect – that of the division of the population behind rival factions of the ruling class, and even of a bloody descent into civil war. The barbarism which has engulfed Syria is a graphic reminder of what that can mean.

The democratic trap

The events of 2011 in Tunisia and Egypt were widely described as a ‘revolution’. But a revolution is more than the masses pouring onto the streets, even if that is its necessary point of departure. We are living in an epoch where the only real revolution can be worldwide, proletarian and communist: a revolution not for a change in regime, but for the dismantling of the existing state; not for a ‘fairer’ management of capitalism, but for the overthrow of the whole capitalist social relationship; not for the glory of the nation, but for the abolition of nations and the creation of a global human community.

The social movements we are witnessing today are still a long way from achieving the self-awareness and self-organisation needed to make such a revolution. They are certainly steps along the way, expressing a profound effort by the proletariat to find itself, to rediscover its past and its future. But they are faltering steps which can easily be derailed by the ruling class, whose ideas run very deep and form a huge obstacle in the minds of the exploited themselves. Religion is certainly one of these ideological obstacle, an ‘opiate’ which preaches submission to the dominant order. But even more dangerous is the ideology of democracy.

In Egypt in 2011, the masses in Tahrir Square demanded the resignation of Mubarak and the fall of the regime. And Mubarak was indeed forced to go – especially after a powerful wave of workers’ strikes spread across the country, bringing a new level of danger to the social revolt. But the capitalist regime is more than just the government of the day. On the social level it is the whole relationship based on wage labour and production for profit. On the political level it is the bureaucracy, the police and the army. And it is also the facade of parliamentary democracy, where the masses are given the choice every few years to choose which gang of thieves is going to fleece them for the next few years. In 2011, the army – which many protesters thought was ‘one’ with the people – stepped in to depose Mubarak and organise elections. The Muslim Brotherhood, which drew massive strength from the more backward rural areas but which was also the best organised political party in the urban centres, won the elections and has since worked very hard to prove that changing the government through elections changes nothing. And meanwhile, the real power remained what it had always been in Egypt, and in so many similar countries: the army, the only force really capable of ensuring capitalist order on a national level.

When the masses surged back to Tahrir Square in June they were full of indignation against the Morsi government and the daily reality of their lives faced with an economic crisis which is not merely ‘Egyptian’ but global and historic. But, even though many of them would have had the opportunity to experience the true repressive face of the army back in 2011, the idea that the ‘people and the army are one’ was still very widespread, and it was given new life when the army began to warn Morsi that he must listen to the demands of the protesters or else. When Morsi was overthrown in a relatively bloodless coup, there were big celebrations in Tahrir Square. Did this mean that the democratic myth no longer held the masses in its grip? No: the army claims to act in the name of ‘real democracy’ which has been betrayed by the Muslim Brotherhood, and immediately promises to organise fresh elections.

Thus the state’s guarantor, the army, again intervenes to ensure order, to prevent the discontent of the masses turning against the state itself. But this time it does it at the price of sowing deep divisions in the population. Whether in the name of Islam or the name of the democratic legitimacy of the Morsi government, a new protest movement is born, this time demanding the return of the regime or refusing to work with those who have deposed it. The response of the army has been swift: a ruthless slaughter of protesters outside the headquarters of the Republican Guard. There have also been clashes, some fatal, between rival groups of demonstrators.

The danger of civil war and the force that can prevent it

The wars in Libya and Syria began as popular protests against the regime. But in both cases, the weakness of the working class and the strength of tribal and sectarian divisions quickly led to the initial revolts being swallowed up by armed clashes between factions of the bourgeoisie. And in both cases, these local conflicts immediately took on an international, imperialist dimension: in Libya, Britain and France, quietly supported by the US, stepped in to arm and guide the rebel forces; in Syria, the Assad regime has survived thanks to the backing of Russia, China, Iran, Hezbollah and other vultures, while arms to the opposition forces have flowed in from Saudi Arabia, Qatar and elsewhere, with the US and Britain in more or less covert support. In both cases, the widening of the conflict has accelerated the plunge into chaos and horror.

The same danger exists in Egypt today. The army has shown its total unwillingness to loosen its effective hold on power. The Muslim Brotherhood has for the moment pledged that its reaction against the coup will be peaceful, but alongside Morsi’s ‘you can do business with me’ brand of Islamism are more extreme factions who already have a background in terrorism. The situation bears a sinister resemblance to what happened in Algeria after 1991 when the army toppled a ‘legally elected’ Islamist government, provoking a very bloody civil war between the army and armed Islamist groups like the FIS. The civilian population was, as always, the main victim in this inferno: estimates of the death toll vary between 50,000 and 200,000.

The imperialist dimension is also present in Egypt. The US has made some gestures of regret about the military coup but its links to the army are very long-standing and deeply implanted, and they are not in the least enamoured of the type of Islamism proclaimed by Morsi or Erdogan in Turkey. The conflicts spreading out from Syria towards Lebanon and Iraq could also reach a destabilised Egypt.

But the working class in Egypt is a much more formidable force than it is in Libya or Syria. It has a long tradition of militant struggle against the state and its official trade union tentacles, going back at least as far as the 1970s. In 2006 and 2007 massive strikes radiated out from the highly concentrated textile sector, and this experience of open defiance of the regime subsequently fed into the movement of 2011, which was marked by a strong working class imprint, both in the tendencies towards self-organisation which appeared in Tahrir Square and the neighbourhoods, and in the wave of strikes which eventually convinced the ruling class to dump Mubarak. The Egyptian working class is by no means immune from the illusions in democracy which pervade the entire social movement, but neither will it be an easy task for the different cliques of the ruling class to persuade it to abandon its own interests and drag it into the cesspit of imperialist war.

The potential of the working class to act as a barrier to barbarism is revealed not only in its history of autonomous strikes and assemblies, but also in the explicit expressions of class consciousness which have appeared within the demonstrations on the streets: in placards proclaiming ‘neither Morsi nor the military’ or ‘revolution not coup’ and in more directly political statements like the declaration of ‘Cairo comrades’ published recently on libcom:

“We seek a future governed neither by the petty authoritarianism and crony capitalism of the Brotherhood nor a military apparatus which maintains a stranglehold over political and economic life nor a return to the old structures of the Mubarak era. Though the ranks of protesters that will take to the streets on June 30th are not united around this call, it must be ours- it must be our stance because we will not accept a return to the bloody periods of the past”[2].

However, just as the ‘Arab spring’ took on its full significance with the uprising of proletarian youth in Spain, which has given rise to a much more sustained questioning of bourgeois society, so the potential of the Egyptian working class to stand in the way of a new bloodbath can only be realised through the active solidarity and massive mobilisation of the proletarians in the old centres of world capitalism.

One hundred years ago, in the face of the First World War, Rosa Luxemburg solemnly reminded the international working class that the choice offered it by a decaying capitalist order was socialism or barbarism. A century of real capitalist barbarism has been the consequence of the failure of the working class to carry through the revolutions which it began in response to the imperialist war of 1914-18. Today the stakes are even higher, because capitalism has accumulated the means to destroy all human life on the planet. The collapse of social life and the rule of murderous armed gangs – that’s the road of barbarism indicated by what’s happening right now in Syria. The revolt of the exploited and the oppressed, their massive struggle in defence of human dignity, of a real future – that’s the promise of the revolts in Turkey and Brazil. Egypt stands at the crossroads of these two diametrically opposed choices, and in this sense it is a symbol of the dilemma facing the whole human species.

Amos 10/7/13

Geographical:

- Egypt [23]

Recent and ongoing:

- Egypt [24]

Rubric:

However it’s funded the ‘labour movement’ serves capitalism

- 1388 reads

The Unite union was accused of cramming the Falkirk constituency with new members, a little bending of the rules to install one of its favoured candidates. Nine Unite-supported candidates have already been nominated as Labour candidates for the next election, with 19 more selections still to be decided. Labour leader Ed Miliband has said that he intends to end the automatic affiliation of union members to the Labour Party, making it a positive individual decision to join the party. While this might cut down the union funds available to the party, it is likely that the unions would just increase funding through other means. That’s certainly what the Tories say, and who’s to say that, in this instance, they’re not right?

Miliband’s proposals are supported by ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair. Other proposals, such as the holding of US-style primaries have been saluted as a sound democratic innovation for British politics. Meanwhile, Bob Crow, leader of the RMT transport union, along with various leftists, thinks that there should be a new Left party that represents working class interests. The Unite union claims that its activities are aimed at ensuring that there are fewer middle class and more working class Members of Parliament. Against this, out-going Falkirk MP Eric Joyce said “The people that Unite want to put into those seats are of course, guess what? Parliamentary researchers, middle class union officials and exactly the same type. The reality is this is an ideological fight. It’s not between the trade unions and Ed Miliband, it’s between Len McCluskey and a few of his anarcho-syndicalist advisers and the Labour party”.

All this is good knockabout stuff and guaranteed to fill the columns of the right-wing press, who insist that Labour hasn’t changed, that it’s a monster from the past. The one thing that it isn’t is a dispute over fundamental questions of principle. All the different Labour and union factions are agreed on essential policy questions. Some accept the argument for the cuts imposed by the Coalition, while others have different state capitalist measures that they think should be employed in the running of the British economy. But these differences are all a matter of degree, differences in emphasis on what the capitalist state should do in maintaining social order, ensuring the most effective exploitation of the working class, surviving in the cutthroat rivalry of capitalism internationally.

While the right-wing media tries to undermine the image of Labour and the unions, the left-wing tries to convince us that there is something to be defended in these capitalist institutions. Don’t be taken in. The differences are only superficial.

Car 13/7/13

Geographical:

- Britain [25]

Recent and ongoing:

- Labour Party [26]

Rubric:

Mandela: a human face for capitalism

- 3935 reads

This article was written several months ago in response to the annointing of Nelson Mandela in the world media earlier this year when his health took a turn for the worse. Now that news of his death has been announced, it seems appropriate once again to counter the suffocating propaganda of the capitalist class.

In the latter part of his life Nelson Mandela was widely considered to be a modern ‘saint’. He appeared to be a model of humility, integrity and honesty, and displaying a remarkable capacity to forgive.

A recent Oxfam report said that South Africa is “the most unequal country on earth and significantly more unequal than at the end of apartheid”. The ANC has presided for nearly twenty years over a society that threatens still further deprivations for the black majority, and yet, despite having been an integral part of the ANC since the 1940s, Mandela was always seen as being somehow different from other leaders, throughout Africa and the rest of the world.

A true Christian?

His 1994 autobiography Long Walk to Freedom (LWF) is an invaluable guide to Mandela’s life and views. Even though it is likely to portray its subject in a favourable light, it shows the concerns and priorities of the author.

For example, after 27 years of imprisonment, when Mandela was released in February 1990 he showed no sign of personal vindictiveness towards those who had kept him captive. “In prison, my anger towards whites decreased, but my hatred for the system grew. I wanted South Africa to see that I loved even my enemies while I hated the system that turned us against one another” (LWF p680). If this sounds like a Christian saying ‘Love the sinner, hate the sin’ it’s partly because it is. When two editors from the Washington Times visited him in prison “I told them that I was a Christian and had always been a Christian” (LWF p620).

You can also see how this trait in his personality proved useful to South African capitalism. After Mandela left prison one of the main tasks of the ANC was to reassure potential investors that a future ANC government would not threaten their interests. In ‘Mandela Message to USA Big Business’ (19/6/1990)[1] you can read something he said on a number of occasions “The private sector, both domestic and international, will have a vital contribution to make to the economic and social reconstruction of SA after apartheid… We are sensitive to the fact that as investors in a post-apartheid SA, you will need to be confident about the security of your investments, an adequate and equitable return on your capital and a general capital climate of peace and stability.” Mandela might have spoken as a Christian, but a Christian who understood the needs of business.

Consistent nationalist

Mandela was certainly consistent, able to look at the present in its continuity with the past. When, for example, the ANC sat down for the first official talks with the government in May 1990 Mandela had to give them “a history lesson. I explained to our counterparts that the ANC from its inception in 1912 had always sought negotiations with the government in power” (LWF p693).

Mandela often referred to the ANC’s Freedom Charter adopted in 1955. “In June 1956, in the monthly journal Liberation, I pointed out that the charter endorsed private enterprise and would allow capitalism to flourish among Africans for the first time” (LWF p205). In 1988, when he was in secret negotiations with the government he referred to the same article “in which I said that the Freedom Charter was not a blueprint for socialism but for African-style capitalism. I told them I had not changed my mind since then” (LWF p642).

When Mandela was visited in 1986 by an Eminent Persons Group “I told them I was a South African nationalist, not a communist, that nationalists come in very hue and colour” (LWF p629). This nationalism was unwavering. When the 1994 election was approaching and he met President FW de Klerk in a television debate “I felt I had been too harsh with the man who would be my partner in a government of national unity. In summation, I said, ‘The exchanges between Mr de Klerk and me should not obscure on important fact. I think we are a shining example to the entire world of people drawn from different racial groups who have a common loyalty, a common love, to their common country’” (LWF p740-1).

From the mid 1970s Mandela received visits from the prisons minister. “The government had sent ‘feelers’ to me over the years, beginning with Minister Kruger’s efforts to persuade me to move to the Transkei. These were not efforts to negotiate, but attempts to isolate me from my organisation. On several other occasions, Kruger said to me: ‘Mandela, we can work with you, but not your colleagues’” (LWF p619).

The South African government recognised that there was something in his personality that would ultimately make some sort of negotiations possible. And, in December 1989, when he first met de Klerk he was able to say “Mr de Klerk seemed to represent a true departure from the National Party politicians of the past. Mr de Klerk …was a man we could do business with” (LWF p665).

Ultimately this mutual respect led in 1993 to the Nobel Peace Prize being awarded jointly to Mandela and de Klerk, in the words of the citation “for their work for the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime, and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa”. This long term goal was not something personal to Mandela but corresponded to the needs of capitalism. After the Sharpeville massacre of 1960, “The Johannesburg stock exchange plunged, and capital started to flow out of the country” (LWF p281). The end of apartheid started a period of growth for foreign investment in South Africa. Democracy did not, however, benefit the majority of the population. In the fifties Mandela said that “the covert goal of the government was to create an African middle class to blunt the appeal of the ANC and the liberation struggle” (LWF p223). In practice ‘liberation’ and an ANC government has marginally increased the ranks of an African middle class. It has also meant repression, the remilitarisation of the police, the banning of protests, and attacks on workers, as in, for example, the Marikana miners’ strike in which 44 workers were killed and dozens seriously injured.

Mandela was able to say that “all men, even the most cold-blooded, have a core of decency, and that if their hearts are touched, they are capable of changing” (LWF p549). What might be true of individuals is not true of capitalism. It has no core of decency and cannot be changed. The faces of the ANC government are different to their white predecessors, but exploitation and repression remain.

Means to an end

The ANC in their ‘liberation’ struggle used both violence and non-violence in its campaigns. When non-violent tactics were proving unsuccessful the ANC created a military wing, in the creation of which Mandela played a central role. “We considered four types of violent activities: sabotage, guerrilla warfare, terrorism and open revolution”. They hoped that sabotage “would bring the government to the bargaining table” but strict instructions were given “that we would countenance no loss of life. But if sabotage did not produce the results we wanted, we were prepared to move on to the next stage: guerrilla warfare and terrorism” (LWF p336).

So, on 16 December 1961, when “homemade bombs were exploded at electric power stations and government offices in Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth and Durban” (LWF p338) it did not mean that the goals of the ANC had changed – democracy was still the aim. And after May 1983, when the ANC staged its first car bomb attack, in which nineteen people were killed and more than two hundred injured, Mandela said “The killing of civilians was a tragic accident, and I felt a profound horror at the death toll. But disturbed as I was by these casualties, I knew that such accidents were the inevitable consequences of the decision to embark on a military struggle” (LWR p618). These days such ‘accidents’ are often referred to by the more modern euphemism of ‘collateral damage’.

Man and myth

In the 1950s Mandela’s first wife became a Jehovah’s Witness. Although he “found some aspects of the Watch Tower’s system to be interesting and worthwhile, I could not and did not share her devotion. There was an obsessional element to it that put me off” (LWF p239). In the arguments they had “I patiently explained to her that politics was not a distraction but my lifework, that it was an essential and fundamental part of my being” (LWF p240).

These differences led to “a battle for the minds and hearts of the children. She wanted them to be religious, and I thought they should be political” (ibid). And what politics were they exposed to?

“Hanging on the walls of the house I had pictures of Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, Gandhi and the storming of the Winter Palace in St Petersburg in 1917. I explained to the boys who each of the men was, and what he stood for. They knew that the white leaders of South Africa stood for something very different” (ibid).

There is an interesting contrast here. On one hand, there are four leading members of the ruling capitalist class (and not so different from the South African bourgeoisie) and, on the other, one of the most important moments in the history of the working class.

Mandela said he had little time to study Marx, Engels or Lenin, but he “subscribed to Marx’s basic dictum, which has the simplicity and generosity of the Golden Rule: ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’” (LWF p137). He might have ‘subscribed to the dictum’, but the history of the ANC has shown it for a century in the service of South African capitalism. Whether in protests or guerrilla struggle, the goals were nationalist, or just for people to let off steam, because “people must have an outlet for their anger and frustration” (LWF p725). In government, the faces changed from Mandela to Mbeki to Motlanthe and now Zuma, but there were no changes in the lives of the majority. The only difference in the Presidents was that Mandela had the best image.

Mandela was very aware of the myth of Mandela. He made a point of saying that he was not a ‘saint’ nor a “prophet”, nor a “messiah” (LWF p676), in a world where most politicians seem to be devoted to self-promotion and enrichment. This modesty was one of the appealing characteristics of Mandela. It could be explained by his Wesleyan background. In his 27 years in captivity he only once missed a Sunday service, “Though I am a Methodist, I would attend each different religious service” (LWF p536).

Whatever the origins of Mandela’s modesty and seeming decency, he is clearly going to be the face of the ANC’s 2014 election campaign. And, beyond South Africa, the Mandela myth will continue to be one of the pillars of modern democratic ideology.

In his career as a lawyer Mandela “went from having an idealistic view of the law as a sword of justice to a perception of the law as a tool used by the ruling class to shape society in a way favourable to itself” (LWF p309). He did not make a similar critique of democracy. In his 1964 court statement he expressed himself as an “admirer” of democracy. “I have great respect for British political institutions, and for the country’s system of justice. I regard the British Parliament as the most democratic institution in the world, and the independence and impartiality of its judiciary never fail to arouse my admiration. The American Congress, the country’s doctrine of the separation of powers, as well as the independence of its judiciary, arouse in me similar sentiments.” (LWF p436) Whatever the character of the man, his life’s work was in the service of capitalist democracy. For its part, capital will certainly continue to make use of his better qualities for the worst possible end: the preservation of its decaying social order.

Car 13/7/13

Geographical:

- South Africa [28]

People:

- Nelson Mandela [29]

Rubric:

NSA Spying Scandal: The Democratic State Shows Its Teeth

- 2505 reads

A comrade in the US reflects on the way different factions of the American bourgeoisie have responded to the ‘spying scandal’

Over the last several weeks the bourgeois media has been engaged in intense coverage of the so-called NSA (National Security Administration) spying scandal. Reports issued by the Guardian and the Washington Post have revealed, through information delivered up by a 29 year old systems manager for NSA contractor Booz Allen, Hamilton, that the United States government has been keeping a phone log of all telephone calls made in the United States, tracking every number dialed, the location of the party called and the call duration. Subsequent reporting revealed that in addition to this log of phone records, the NSA, through its so-called Prism program, has been directly tapping into the servers of the very companies that form the backbone of the World Wide Web: Facebook, Google, MSN, Apple, to name just a few.

Over the last several weeks the bourgeois media has been engaged in intense coverage of the so-called NSA (National Security Administration) spying scandal. Reports issued by the Guardian and the Washington Post have revealed, through information delivered up by a 29 year old systems manager for NSA contractor Booz Allen, Hamilton, that the United States government has been keeping a phone log of all telephone calls made in the United States, tracking every number dialed, the location of the party called and the call duration. Subsequent reporting revealed that in addition to this log of phone records, the NSA, through its so-called Prism program, has been directly tapping into the servers of the very companies that form the backbone of the World Wide Web: Facebook, Google, MSN, Apple, to name just a few.

According to the so-called whistleblower, Edward Snowden, the technical abilities the NSA now has at its disposal are profound. He claims to have been able to tap directly into any email anywhere, including even President Obama’s. According to his description of the Prism program, the technology is so powerful that an NSA analyst can tap into whatever instant message conversations he/she wants to at any moment. As a part of the story, we also learned that these programs appear to have been given the cover of legality by a sweeping Foreign Intelligence Security Act (FISA) Court warrant allowing the government to “legally” collect this data.

It has been quite clear that the release of this information has been very uncomfortable for the US bourgeoisie. It hasn’t been a good period for the democratic illusion in the United States—the capitalist nation state that champions itself to its own citizens and the world beyond as the foremost guarantor of democracy and civil rights. The revelations about the NSA’s spying programs are only the latest in a series of embarrassing episodes that cast growing doubt on the ability of the US bourgeoisie to credibly proclaim America as a democracy guided by the rule of law. When these revelations hit the news, there was already a build-up of questioning about the Obama administration’s continued use of pilotless drones to kill suspected terrorists, including American citizens, as a matter of executive fiat without even the hint of due process.

Just weeks prior to Snowden’s confession, Obama had been forced to make a nationwide address defending his drone program and excusing the state murder by drone of an American citizen without trial (alleged terrorist Anwar Al-Awlaki). Although he has pledged to close the gulag at Guantanamo Bay, the continued hunger strike and force-feeding of the remaining detainees has been a major blemish on the image of American democracy abroad. While on this issue, Obama has tried to play himself as the good guy working to close the prison in opposition to a hostile Republican dominated Congress, his inability to close Guantanamo and thus fulfill a promise from his first campaign, is a major stick in the craw for his liberal base. While it would be an exaggeration to say that the US’s international image has sunk as low as it did during the Bush administration, it has certainly declined since the days of joyous celebrations following Obama’s initial election.

However, the revelations about the NSA spying programs strike much deeper at the heart of the illusion of American democracy and civil liberties than any of these other issues, as they affect the entire American population writ large. No longer are the excesses of the “surveillance state” directed only at shadowy dark-skinned foreigners or traitors who have gone over to the other side, but at every single American regardless of whether or not they are suspected of any wrongdoing. The worst Orwellian fears appear to have been realized. We are all being tracked, pretty much all the time and there appears to be nothing we can do to hold the state accountable for it. What kind of “democracy” is this?

The Confused Reaction of the Bourgeoisie

Just how uncomfortable Snowden’s revelations have been for the US ruling class was evident in the rather unusual and stumbling reaction of the various bourgeois factions. Many top congressional figures professed to know nothing about these programs and claimed to be deeply concerned by them, or—at the very least—slighted that they weren’t told about them. Judging by how uncoordinated the bourgeoisie’s initial response to the news appears to have been, there is reason to believe that they were not just making this up.

Still, the various heads of the Congressional intelligence committees were quick to react with anger to the release of this classified information. As they clumsily tried to assuage the public by telling us that this stuff had been going on for quite some time and it was nothing new under the sun, etc., their furor was palpable with many calling for the immediate arrest and prosecution of Snowden as a “traitor.” President Obama himself, forced by the growing media frenzy to make a statement, attempted to assure Americans that these programs were vital tools in the fight against terrorism that had stopped terrorist plots in their tracks and that in reality nobody was really listening to their phone calls, at least not without a warrant.

One of the most striking features of the bourgeois response was the unlikely coalitions that emerged. Supposed Liberal Senator from California Diane Feinstein was on the same page as militarist Republicans like John McCain and Lindsey Graham in defending the programs and calling for Snowden’s swift prosecution. Meanwhile right-wing crackpot radio host Glenn Beck and progressive documentarian Michael Moore each declared Snowden a hero. Similarly, while Ron Paul wondered out loud if Snowden would be taken out by a cruise missile, liberal/progressive radio host Ed Schultz—using language typically employed by right wing bullies—aggressively called the leaker a “punk.”

The bourgeoisie have been unable to find a coherent political narrative in which to situate these revelations. The familiar left/right division of ideological labor simply isn’t working out on this one. On the left, the progressive/liberal talking heads are put in a corner. Whatever their level of personal discomfort with these programs, they are obliged to defend a scandal-plagued Obama administration from yet one more embarrassment. On the right, there is a clear divide between the authoritarian hawks who proudly declare (as any good fascist would), “if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear”, and a libertarian element who see everything the state does as a plot to construct a tyrannical fascist/socialist Leviathan.

Clearly, the bourgeoisie is having difficulty getting its ducks in a row in order to present a coherent binary narrative to the public through which to explain this one in comfortable and familiar terms. It is likely for this reason that once the identity of the leaker became known, the media quickly attempted to change the story to make it all about the personality of Mr. Snowden. Just who was this guy? What was his story? Why did he do it? In a painful ode to the celebrity spectacle that today defines American pop culture, the media turned a story about the world’s most powerful “democratic” state spying on every single one of its citizens into a psycho-drama about Snowden’s supposed megalomania, naivety and youthful hubris.

The message was clear: the government may be spying on you, but at least now there is a new celebrity villain/hero personality to delve into and probably an exciting court room drama coming up in the future if/when the US state finally lays it hands on him! That is, if he isn’t extraordinarily rendered somewhere or mysteriously dies of a heart attack while holed up in the Ecuadorean ambassador’s residence. It’s international intrigue worthy of a Le Carré novel! It seemed, as in a modern day twist on the famous words attributed to Marie Antoinette, the bourgeoisie told the public, “If you can’t get openness in government, transparency and all the other mush that is supposed to go along with democracy, well, at least you can eat drama.”

Nevertheless, the bourgeois reaction to this story, as incoherent as it was, stands as a clear illustration of the rifts that have been tearing into the fabric of the US ruling class. Forced to keep the left of its political apparatus in executive power over concerns about the Republican Party’s ability to rationally steer the economy and the ship of the state, the Obama administration has had to govern in a way that puts its “left” credentials into severe question.[1] Already before these revelations, rumblings about Obama being just a kindler gentler version of Bush were rampant among many of the President’s erstwhile supporters.

Contrary to its traditional ideological role as the questioners of repressive power, key elements in the Democratic Party have had to come out in support of these massive spying programs. Meanwhile, law and order Republicans, who on any other day would probably prefer to see Obama join the millions of other African-Americans in prison, have come out as among the administration’s loudest cheerleaders in favor of keeping these programs in full force. The US political crisis continues. In sharp contrast to the image of overwhelming technical power wielded by its intelligence agencies, it’s the sad case that US bourgeoisie can’t even get its messaging straight on how to sell these programs to the public.

The “Democratic” State and Civil Liberties: Illusion Or Structure?