World Revolution no.350, December 2011-January 2012

- 1781 reads

Capitalism is bankrupt: We need to overthrow it

- 2482 reads

There was a time, not so long ago, when revolutionaries were greeted with scepticism or mockery when they argued that the capitalism system was heading towards catastrophe. Today, it’s the fiercest partisans of capitalism who are saying the same thing. “Chaos is there, right in front of us” (Jacques Attali, previously a very close associate of President Mitterand and former director of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; now an adviser to President Sarkozy, quoted in the Journal du Dimanche, 27/11/11). “I think that you are not aware that in a couple of days, or a week, our world could disappear...we are very close to a great social revolution”(Jean-Pierre Mustier, bank director, formerly at the Société Générale. www.challenges.fr/finance-et-marche [3]). It’s not with any joy in their hearts that these defenders of capitalism are admitting that their idol is on the way out. They are obviously shattered by this, all the more so because they can see that the solutions being put forward to save the system are unrealistic. As the journalist reporting Jean-Pierre Mustier’s words put it: “as for solutions, the cupboard is bare”. And with good reason!

Whatever their lucidity about what’s in store for capitalism, those who think that no other society is possible are not going to be able to put forward any solutions to the disaster now threatening humanity. Because there are no solutions to the contradictions of capitalism inside this system. The contradictions it is confronting are insurmountable because they are not the result of ‘bad management’ by this or that government or by ‘international finance’ but quite simply of the very laws on which the system is founded. It is only by breaking out of these laws, by replacing capitalism with another society, that humanity can overcome the catastrophe that is staring us in the face. It is only by putting forward this perspective that we can really understand the nature of the crisis that capitalism is going through.

The only solution: free humanity from the yoke of capitalism

Just like the societies which came before it, such as slavery and feudalism, capitalism is not an eternal system. Slavery predominated in ancient society because it corresponded to the level of agricultural techniques which had been achieved. When the latter evolved, demanding far greater attention on the part of the producers, society entered into a deep crisis – the decadence of Rome. It was replaced by feudalism where the serf was attached to his piece of land while working for part of his time on the lord’s land or giving up part of his harvest to the lord. At the end of the Middle Ages this system also became obsolete, again plunging society into a historic crisis. It was then replaced by capitalism which was no longer based on small agricultural production but on commerce, associated labour and large industry, which were themselves made possible by progress in technology (the steam engine for example). Today, as a result of its own laws, capitalism has in turn become obsolete and must give way to a higher system.

But give way to what? Here is the key question being posed by more and more people who are becoming aware that the present system has no future, that it is dragging humanity into an abyss of poverty and barbarism. We are not prophets who claim to describe the future society in all its details, but one thing is clear: in the first place, we have to abolish production for the market and replace it with production whose only aim is the satisfaction of human need. Today, we are confronted by a real absurdity: in all countries, extreme poverty is growing, the majority of the population is forced to go without more and more, not because the system doesn’t produce enough but because it is producing too much. They pay farmers to reduce their production, enterprises are closed down, wage earners are sacked en masse, vast numbers of young people are condemned to unemployment, including those who have spent years studying, while at the same time the exploited are more and more forced to pull in their belts. Misery and poverty are not the result of the lack of a work force capable of producing, or of the lack of means of production. They are the consequences of a mode of production which has become a calamity for humanity. It is only by radically rejecting production for the market that the system that succeeds capitalism can put on its banner “From each according to their means, to each according to their needs”.

The question then posed is this: “how do we get to such a society?? What force in the world is capable of taking in charge such a huge transformation in the life of humanity?” It is clear that such a transformation cannot come from the capitalists themselves or the existing governments who all, whatever their colouring, defend the present system and the privileges it gives them. Only the exploited class under capitalism, the class of wage labourers, the proletariat, can carry out such a total change. This class is not the only one that suffers from poverty, exploitation and oppression.

For example, throughout the world there are multitudes of poor peasants who are also exploited and often live in worse conditions than the workers in their countries. But their position in society does not enable them to take charge of constructing a new society, even if they also have a real interest in such a change. More and more ruined by the capitalist system, these small producers aspire to turning back the wheel of history, to go back to the blessed days when they could live from their own labour, when the big agro-industrial companies didn’t take the bread from their mouths. It is different for the waged producers of modern capitalism. What’s at the basis of their exploitation and their poverty is wage labour - the fact that the means of production are in the hands of the capitalist class (whether in the form of private owners or state capital), and the only way they can earn their daily bread and a roof over their heads is to sell their labour power. In other words, the profound aspiration of the class of producers, even if the majority of its members are not yet conscious of this, is to abolish the separation between producers and means of production which characterises capitalism, to abolish the commodity relations through which they are exploited, and which are the permanent justification for the attacks on their income since, as all bosses and governments say: “you’ve got to be competitive”.

Therefore the proletariat has to expropriate the capitalists, collectively take over the whole of world production in order to make it a means of truly satisfying the needs of the human species. This revolution, because that’s what we are talking about, will inevitably come up against all the organs capitalism uses to preserve its rule over society, in the first place its states, its forces of repression, but also the whole ideological apparatus which serves to convince the exploited, day after day, that capitalism is the only possible system. The ruling class will be determined to stop by all possible means the ‘great social revolution’ which haunts the banker mentioned above and many of his class companions.

The task will therefore be immense. The struggles which have already begun today against the aggravation of poverty in countries like Greece and Spain are just the first necessary step in the proletariat’s preparations for the overthrow of capitalism. It’s in these struggles, in the solidarity and unity that they give rise to, in the consciousness they engender about the possibility and necessity to get rid of a system whose bankruptcy is daily becoming more obvious, that the exploited will forge the weapons they need to abolish capitalism and install a society finally free of exploitation, of poverty, of famine and war.

The road is long and difficult but there isn’t another. The economic catastrophe on the horizon, which is creating such disquiet in the ranks of the bourgeoisie, will bring with it a dire worsening of living conditions for all the exploited. But it will also enable them to set out on the path of revolution and the liberation of humanity

Fabienne 7/12/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [4]

- Economic Crisis [5]

Rubric:

Occupy London, a space for discussion

- 1763 reads

In recent weeks, comrades of the ICC have attended, and on two occasions given, talks at the Occupy site in St Paul’s. As has been the case in the last few years with movements in North Africa, Greece and, most notably, Spain there is a multiplicity of ideas being discussed. The Occupy movement is no different. As we wrote in the last edition of WR, there is a need to wage a struggle within such movements for a workers’ perspective “Occupy London is not only smaller than the movements in Spain and the USA that inspired it, but the voices raised in support of a working class perspective have been relatively weaker, and those defending parliamentary democracy relatively stronger. For instance the efforts to send ‘delegations’ to the electricians’ protests only a short walk away were seen as an entirely individual decision and initiative of those who participated, whereas in Oakland the Occupy Movement called for a general strike as well as evening meetings so that those who had to work could also participate.”

The movement as a whole is heavily impregnated with reformism – the idea that if some aspect(s) of capitalism were changed this would change the overall functioning of capitalism, and its current dynamic. There is a widespread idea that capitalism can be made a ‘fairer’ more ‘humane’ system and that it’s possible to tackle the biggest economic crisis in its history.

Among some of our experiences:

One comrade attended one of the Tent City University meetings, entitled ‘Here’s the risk: Occupy ends up doing the bidding of the global elite’. Presented by Patrick Hennigsen, an American investigative journalist, who made some very pertinent points about attempts by bourgeois foundations like the one funded by George Soros to recuperate Occupy movements from Tunisia to New York. Hennigsen insisted that ‘right versus left’ was a dead-end. His alternatives however weren’t that illuminating – taking money out of banks and putting it in credit unions, etc. He also argued that if there’s no free market, it’s not capitalism. We spoke to say we agreed with the danger of recuperation but we had to have some basic clarity about what capitalism is otherwise the movement will indeed be trapped in false alternatives.

Another comrade attended a meeting presented by Lord Robert Sidelsky entitled “The crises of capitalism” which asked questions such as: Why does the system collapse? How do we recover from the present recession? How do we build a better system? Again, there were some interesting observations made. For example that capitalism is not just about economics, but that it’s also a system of power and hierarchy, that the crisis in the eurozone is not the cause of the UK crisis, that figures for GDP in themselves don’t say everything about ‘growth’ – all valid questions for discussion. However, again, the answers that were put forward were entirely within the framework of changes already proposed by one or other faction of the ruling class, such as for a Tobin Tax on all financial transactions, more work sharing, a government investment bank etc.

Despite all the illusions in the possibilities of reform, the occupation has provided a space for a discussion of ideas, even ideas that are rarely heard. As another comrade said “… a couple of people in the tents near our stall put out a piece of cardboard saying ‘Discussion point’ and an impromptu discussion about whether a new society was possible began with around a dozen people taking part. The best contribution was from a woman who felt that it was the process of discussion itself, people breaking from isolation to come together and talk, which was the most positive thing about the Occupy movement.”

Some comrades of the ICC gave a talk about the ideas of Rosa Luxemburg on the rise and decline of capitalism. There were barely more than a dozen there but nonetheless the discussion was lively and interesting and posed things in a deeper way. It is the capacity to have a political confrontation of ideas that is the basis for a development in consciousness and political maturity in the face of the questions capitalism is posing to the whole world today.

Graham 10/12/11

Life of the ICC:

- Intervention [7]

Recent and ongoing:

- Occupy movement [8]

- Occupy London [9]

Rubric:

Best years of your life?

- 5335 reads

It’s not much fun being young at the moment. If you manage to stay in education you end up accruing large debts only to be told standards are slipping and the only reason you’ve passed is because the exams are so easy now. On the street you’re either patronised as a ‘chav’ or feared as a ‘hoodie’. Everything from the summer riots to cultural decline is down to you and your self obsessed, greedy individualism: you just can’t win.

The cherries on the top of this rancid cake are the recent announcements on youth ‘employment’. Figures published by the Department for Education (DfE) in November showed that the number of Neets has risen to a record high of 1.16 million with almost one in five 16 - 24 year olds in England ‘not in education, employment or training’ between July and September this year. “The figure was up 137,000 [a rise of 13%] on the same period last year. Just over 21% of 18 - 24 year olds are not in education, work or training” (Guardian 25/11/11). Records, demonstrated by a confusing array of statistics, may have been broken across the board - “official figures published last week show there were 1.02 million unemployed 16 to 24 year olds in the UK between July and September this year, also a record” (ibid) - but the results for young people are the same.

In response the Government has wheezed into action. Even though they “know many young people move between school, college, university and work during the summer, which explains why Neet figures are higher during this quarter” (ibid) they promise not to be complacent. This doesn’t mean that they’ll review scrapping the Education Maintenance Allowance, rethink increasing university tuition fees or reopen closed career services. No, it’s a retro response, we’re going back to the 1980s. Nick Clegg has announced a billion pounds of new funding, with the money possibly coming from a freeze in tax credits paid to working families, “to be spent over three years, [that] will provide opportunities including job subsidies, apprenticeships and work experience placements to 500,000 unemployed” (ibid). All of which sounds like the Youth Training Scheme (YTS) that were so ‘popular’ and so ‘successful’ in the 80s. If they’re lucky enough to be signed up to this ‘youth contract’ - and that may not be easy, recently there has been a 900% increase in the number of apprenticeships begun by those aged 60 and over (Guardian 14/11/11) - participants will lose their benefit and be expected to “stick with it”, whatever that may mean. And sometimes they’ll have to work to get their ‘benefits’.

While there was never a golden age for young people in capitalist society it’s impossible not to respond to these recent developments without utter contempt for those who rule us. Despite what the bourgeois press claims young workers a generation ago didn’t have it easy but there was at least the illusion that if you followed the ‘rules’, ‘played the game’ and worked or studied hard capitalism would ‘reward’ you - i.e. you would, usually, be ‘better off’ than your parent’s generation; with a little sacrifice you could own your own home and save for your retirement. With the acceleration of the crisis the same can not be said today. Young people are now faced with huge obstacles, both economically and socially, having to run merely to stand still, so it’s hardly surprising that some give up trying to ‘build’ Michael Gove’s laughable ‘aspirational nation’. Faced with, at best, an uncertain future and criticised at every turn, who’d blame them.

‘He who has youth has the future’: this phrase attributed to both Lenin and Trotsky is on one level banal, a truism, but on another it suggests something much more - the idea that young people have the ability to shape, to change their future. This idea is currently being put into practice by young people around the world in the student and Occupy movements, which despite their illusions in democracy, are a direct response to all those who want to dismiss and marginalise the young. If these movements are able to reach out to the working class they will be able to begin pose a real alternative to capitalism: communism. If that happens these just could be the best years of your life… .

Kino 9/12/11

General and theoretical questions:

- Economic crisis [10]

Recent and ongoing:

- Unemployment [11]

- youth [12]

Rubric:

The unions are part of the attack on workers’ pensions

- 3280 reads

After the trade union marches and strikes against the Coalition’s pension cuts the unions went straight back into the serious business of working with government officials in order to implement the latest austerity measures. November 30 was deliberately chosen by the unions for a strike in order to cause the minimum disruption – the airlines for example privately welcomed the date. “Now, after the strike” says Dave Prentis, General Secretary of Unison, “we want to reach a negotiated settlement”. So individually, behind the scenes, relying on their usual tactics of division and secret talks, the unions are again working with the government against the interests of the working class.

Mark Serwotka’s Public and Commercial Services union (PCS) gives us a good idea of what to expect. Serwotka presents his union as a militant defender of working class interests but the opposite is the truth. In 2006, the PCS “negotiated” with the then Labour Government, the raising of the retirement age of its members from 60 to 65 and greatly reduced payments by agreeing to go from a final salary scheme to a career average. This was put in place in 2007.

Further, the PCS has proposed to increase its own workers’ pension payments by 10% in 3 consecutive yearly hikes of three-and-a-third per cent. The PCS workers belong to a branch of the GMB union and seeing that the proposals have been in the hands of the president of “GMB@PCS” branch since last July, a stitch up of the workers by both unions is on the cards. More than this, while the PCS has gone to the High Court (where the union’s lawyers get even richer) to challenge the government’s move to change pension entitlements based on the higher Retail Price Index (RPI) to the lower Consumer Price Index (CPI), the union has imposed exactly this change on its own workers’ pension scheme, thus further cutting the value of their pension payments (employees benefits.co.uk)

This hypocrisy is one more indication of the double language of the unions who not only do not defend our interests but are part of the attack upon them.

Baboon 8/12/11

Geographical:

- Britain [13]

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [4]

- Pensions [14]

- Trade Unions [15]

Rubric:

Unions and police are two arms of the same state

- 3417 reads

On November 9, 10,000 students marched in central London, spurred on by the mounting cost of education and a will to fight the government’s programme of austerity. Recalling last year’s student demonstrations, which often posed severe problems for the police, and aware that the students are a somewhat volatile force, who are not really ‘disciplined’ by legal minded union officials, the state took no chances. The demonstration was therefore treated not to the kettle, but to the ‘sock’, a kind of mobile kettle, where marchers were herded down a prescribed route with seriously equipped police contingents on either side, blocking the possibility of demonstrators breaking off to right or left, or others joining the march along the way.

Meanwhile, several hundred electricians had been holding the second of two demonstrations against pay cuts at nearby building sites. Although the unions had organised a lobby of parliament, a large group of electricians and supporters took the position of ‘sod that, we want to join the students’, and started to move towards the student march. They were very quickly met by a police line, and those who didn’t manage to evade it were kettled. Attempts by those who had escaped to get help from the students were blocked as another police line delayed the student march for some time.

In short: a massive police presence, very well organised, overseen by helicopters, and capable of acting swiftly to prevent anyone from stepping out of line.

On November 30, in central London, 50,000 public sector workers marched in protest against attacks on their pensions, part of one of the biggest national strikes for many decades. This time, the police operation was of the softly softly kind, very low key, no sign of socks or kettles: you could leave the march or join it when and where you wanted. It gathered in good order, marched along in cheerful humour, and dispersed when the speeches at the rallying point were over, if not well before.

Why was this? Could it have anything to do with the fact that, unlike the students and the electricians, the public sector strike had been controlled from start to finish by the unions, who are much more effective than a confrontational police force in containing workers with their march stewards, their well-rehearsed rallies and their widely accepted role as the official representatives of the working class?

Not that the police didn’t show their other side that day. In Dalston, when a group of young people who had been roaming around showing solidarity with pickets staged a short road block outside the CLR James library, they were immediately set upon by dog-wielding heavies and caught up in a kettle, followed by numerous arrests, terrifying a number of small children in the process. At the end of the march, a group of activists who had carried out a banner drop in Piccadilly were given similar treatment.

So let that be a lesson to you: if you start acting unofficially, if you question the trade unions’ History-given right to lead, you will face the full force of the Law. Put another way: unions and police are two arms of the same state.

Amos 10/12/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Student struggles [16]

- November 30 Strike [17]

- Electricians strikes [18]

Rubric:

Sparks: don’t let the unions block the struggle

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 1.37 MB |

- 1775 reads

Electricians have been protesting against the proposed 35% pay cut for 4 months. Vociferous early morning protests in London, Manchester, the North East, Glasgow and elsewhere, blockading or occupying building sites run by the 7 firms trying to impose a change in pay and conditions, a demonstration in London on 9th November coinciding with the students and wildcats and blockades of sites on 7th December.

In spite of this militancy, in spite of the fact that sparks were being asked to sign their new contracts by early December or lose their jobs (now put back to January), the Unite union did not ballot for strike action until November, and then only for its members working for Balfour Beatty, seen as the employers’ ringleader, and only for a limited strike. Even with an 81% majority that vote was challenged and Unite are repeating the ballot, preventing an official strike on 7th December – but not the unofficial strikes and blockades at Grangemouth, Immingham, Cardiff, Manchester, London and many other places. In places workers refused to cross the pickets lines and despite heavy police presence many building sites were shut down.

The struggle so far

The strikes and protests which have gone on since 8 employers announced they wanted to leave the Joint Industry Board and impose lower pay and worse conditions through BESNA have been characterised by:

- repeated wildcat strikes;

- meetings outside building sites to ensure all sparks are aware of the threatened pay cut and to try and involve them in the struggle, and sometimes brief occupations or blockades. These meetings have become a focus for sparks to show their determination to struggle, and for others to show their solidarity. An open mic has allowed a real discussion;

- a determined search for solidarity within the construction industry and beyond it. There has been a recognition that they need to get the solidarity of workers in other trades, and that they would be next if the pay cut is imposed on the electricians. Workers inside and outside the union would need to be involved, although this is seen in terms of getting them to join the union. And there has been a significant effort to seek solidarity of workers in other industries expressed in the strikes and demonstrations on 9th November to coincide with the student protest and the proposal to do the same on 30th alongside the public sector workers. At Farringdon on 16th November, although the numbers outside were smaller, some workers – including a group of Polish workers – refused to go in;

- supporters from Occupy London have been welcomed, and several hundred electricians marched to St Paul’s to show solidarity with their protest.

The action on the 9th November showed all these tendencies, starting with a rank and file protest outside the Pinnacle near Liverpool Street after blocking the road it moved off to visit several other construction sites run by BESNA companies and held open mic sessions before joining the main Unite demonstration at the Shard. Several hundred sparks decided not to go to the union lobby of parliament but to join the students. They were immediately kettled and despite their best efforts most were contained and searched – apart from a few who escaped through a coffee shop. The ruling class really do want to keep us apart!

On December 7, as well as calling on sparks to come out the picket at Balfour Beatty at St Cath’s Birkenhead sought out NHS Estates workers to explain why they were picketing – and got a sympathetic hearing.

There is a media blackout of all this. Nothing on the pay cut. Nothing on the protests, blockades and occupations. Virtually nothing on the demonstration on 9th November, despite the notion that lobbying parliament would attract the media. It is typical of the media to keep quiet about a struggle that the ruling class think is a bad example to other workers. And what the sparks have done so far is certainly an inspiration.

No information passed through union channels either, despite platonic assurances of support from other unions – I tried asking pickets outside Great Ormond Street Hospital on 30 November and they knew nothing of the attack on the sparks, nothing of their struggle. We shouldn’t be surprised.

Difficulties developing the struggle

Jobs are scarce, living standards are falling as inflation eats away at real wages, and all these attacks are presented as painful but necessary by politicians and media. This is true for the whole working class, but the difficulties faced in construction are much more acute. Thousands of militant workers have been blacklisted, and many of them remain unemployed, and this is a real intimidation against the whole workforce. Then there is the difficulty getting regular work, many are forced to subcontract (subbies) or work through an agency with appalling effects on their pay and conditions, and the potential for divisions among workers along these lines. Hardly surprising that many workers hesitate: “Most of the lads are still not up for the unofficial action, a few boys are going down to London though … The lads are coming round to the idea of the official strike. They are looking out for their jobs which is understandable” (post on ElectriciansForum.co.uk).

This situation shows that the electricians’ need to fight far more than the 7 or 8 BESNA firms that want to impose a 35% pay cut next year. The agencies already pay less, as do a large number of firms which are not part of the JIB, and those that are only fulfil its rules when it suits them: “The JIB/SJIB set up is NOT working as it should, pure and simple!!!” (post on the same forum).

Unite – are we really the union?

With the original deadline for workers to sign the new agreement looming and no official strike called sparks are getting extremely frustrated with the union. “1 day out wont in my opinion cause much harm, these firms will have plenty of notice of when & how many… IT MAY ALREADY BE TOO LATE”, “people are reluctant to join a union that is run by ‘nodders’ that will sell its members down the river for personal gain”, “I do not trust Unite one single bit to negotiate a deal that satisfies us. I have seen too many of their sweetheart deals in various industries. It is imperative that Rank and File members are party to any negotiations that take place”. The union has been described as “contemptible” for its inaction and absence from the protests. On the other hand “the union is far from perfect but it is all we have”, there can be no Rank and File without the union and no union without the Rank and File.

So why do the unions keep behaving like this? One of Unite’s greatest defenders on the forum tells us “ffs stop the union bashing, they will be the ones around the table negotiating the deals..we all play our own part in one way or another but its Unite who will do the main stuff” and “Unite are there to make deals with union lads whose companies have a relationship with Unite, they are there for their members, Unite is not there to represent a whole industry or an agency”. This is precisely the problem. Unions are there to negotiate with the bosses – workers have a walk on part, in the ballot or on militant demonstrations, but the main union business takes place behind their backs. And they are limited to making deals with unionised companies. The unions limit our struggle, divide it by job, by membership of this or that union, by this or that employer. But sparks are facing a 35% pay cut across the whole industry, on workers in or out of a union. And it is only one part of the attacks on the whole working class which needs to unite across all the divisions of trade or profession, of employer, regardless of membership of any particular union or none.

Rank and File Group

The struggle so far has been organised by the Unite Construction Rank And File Group, headed by a committee elected at a meeting in Conway Hall, London, in August and which has held meetings up and down the country. They took the view that “It is now widely accepted that we can’t and won’t wait for the ballot, though we will all be glad when it comes. But until then we must step up the campaign to one of even more unofficial action, walkouts on sites with solidarity action from others” (https://siteworker.wordpress.com [21]). In September 1500 electricians walked out of Lindsey oil refinery to join a demonstration of electricians. Like the national shop stewards committee the Rank and File Group takes a very militant stance – at times at arm’s length from the union and at times arm in arm. “We are working for the same goals both the Rank & File Committee and the official unions. We are working for the same objective. Don’t allow people to divide us” said Len McCluskey outside the Shard on 9 November, despite the fact that Unite leaders have been conspicuous by their absence from most of the protests, apart from a few token showings, such as at Blackfriars in October.

The efforts of the Rank and File Group show the sparks’ militancy, the determination of a minority to resist this attack. It also shows their attachment to the union and its methods of struggle, including the view that the aim of the struggle is negotiation between BESNA and Unite, and that convincing workers to struggle means recruiting them into the union. The dynamic of the struggle, as we have seen, goes far beyond trade union methods and even in a completely different direction with the attempts to link up with workers in other trades whether in a union or not and with other struggles, rather than confining the struggle to Unite members and their employers. The sparks’ total rejection of the cut in pay and apprenticeships contrasts with Unite’s assurance that they will discuss modernisation.

General assemblies to run the struggle, mass meetings open to all workers regardless of union membership, are the way for workers to take the struggle into their own hands, and to spread it to other workers.

Alex 9/12/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Electricians strikes [18]

Rubric:

Why is capitalism drowning in debt?

- 3555 reads

The global economy seems to be on the brink of the abyss. The threat of a major depression, worse than that of 1929, looms ever larger. Banks, businesses, municipalities, regions and even states are staring bankruptcy in the face. And one thing the media don’t talk about any more is what they call the “debt crisis”.

When capitalism comes up against the wall of debt

The chart below shows the change in global debt from 1960 to present day. (This refers to total world debt, namely the debts of households, businesses and the States of all countries). This debt is expressed as a percentage of world GDP.

Graph 1

According to this chart, in 1960 the debt was equal to the world GDP (i.e. 100%). In 2008, it was 2.5 times greater (250%). In other words, a full repayment of the debts built up today would swallow up all the wealth produced in two and a half years by the global economy.

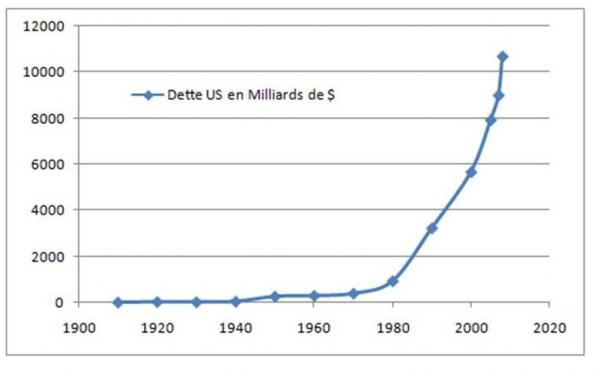

This change is dramatic in the so-called “developed countries” as shown in the following graph which represents the public debt of the United States.

Graph 2

In recent years, the accumulation of public debt is such that the curve on the previous graph, showing its change, is now vertical! This is what economists call the “wall of debt.” And it is this wall that capitalism has just crashed into.

Debt, a product of capitalism’s decline

It was easy to see that the world economy was going to hit this wall eventually; it was inevitable. So why have all the governments of the world, whether left or right, extreme left or extreme right, supposedly “liberal” or “statist”, only extended credit facilities, run bigger deficits, actively favoured increasing the debts of states, firms and households for over half a century? The answer is simple: they had no choice. If they had not done so, the terrible recession we are entering now would have begun in the 1960s. In truth, capitalism has been living, or rather surviving, on credit for decades. To understand the origin of this phenomenon we must penetrate what Marx called “the great secret of modern society: the production of surplus value”. For this we must make a small theoretical detour.

Capitalism has always carried within it a kind of congenital disease: it produces a toxin in abundance that its organism cannot eliminate: overproduction. It produces more commodities than the market can absorb. Why? Let’s take a simple example: a worker working on an assembly line or behind a computer and is paid £800 at the end of the month. In fact, he did not produce the equivalent of the £800, which he receives, but the value of £1600. He carried out unpaid work or, in other words, produced surplus value. What does the capitalist do with the £800 he has stolen from the worker (assuming he has managed to sell all the commodities)? He has allocated a part to personal consumption, say £150. The remaining £650, he reinvests in the capital of the company, most often in buying more modern machines, etc.. But why does the capitalist behave in this way? Because he is economically forced to do so. Capitalism is a competitive system and he must sell his products more cheaply than his neighbour who makes the same type of products. As a result, the employer must not only reduce his production costs, that is to say wages, but also increase the worker’s unpaid labour to re-invest primarily in more efficient machinery to increase productivity. If he does not, he cannot modernise, and, sooner or later his competitor, who in turn will do it, and will sell more cheaply, will conquer the market. The capitalist system is affected by a contradictory phenomenon: it does not pay workers the equivalent of what they have actually produced as work, and by forcing employers to give up consuming a large share of the profit thus extorted, the system produces more value than it can deliver. Neither the workers, nor the capitalists and workers combined can therefore absorb all the commodities produced. Therefore capitalism must sell the surplus commodities outside the sphere of its production to markets not yet conquered by capitalist relations of production, the so-called extra-capitalist markets. If this doesn’t succeed, there is a crisis of overproduction.

This is a summary in a few lines of some of the conclusions arrived at in the work of Karl Marx in Capital and Rosa Luxemburg in The Accumulation of Capital. To be even more succinct, here is a short summary of the theory of overproduction:

- Capital exploits its workers (i.e. their wages are less significant than the real value they create through their work).

- Capital can thus sell its commodities at a profit, at a price which, greater than the wage of the worker and the surplus value, will also include the depreciation of means of production. But the question is: to whom?

- Obviously, the workers buy commodities ... using their entire wages. That still leaves a lot for sale. Its value is equivalent to that of the unpaid labour. It alone has the magic power to generate a profit for capital.

- The capitalists also consume ... and they are also generally not too unhappy about doing so. But they cannot alone buy all the commodities bearing surplus value. Neither would it make any sense. Capital cannot buy its own commodities for profit from itself; it would be like taking money from its left pocket and putting it in its right pocket. No one is any better off that way, as the poor will testify.

* To accumulate and develop, capital must find buyers other than workers and capitalists. In other words, it is imperative to find markets outside its system, otherwise it is left with unsalable commodities on its hands that clog up the capitalist market; this is then the “crisis of overproduction”!

This “internal contradiction” (the natural tendency to overproduce and the necessity to constantly seek out external markets) is one of the roots of the incredible driving force of the system in the early stages of its existence. Since its birth in the 16th century, capitalism had to establish commercial links with all economic spheres that surrounded it: the old ruling classes, the farmers and artisans throughout the world. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the major capitalist powers were engaged in a race to conquer the world. They gradually divided the planet into colonies and created real empires. Occasionally, they found themselves coveting the same territory. The less powerful had to retreat and go and find another territory where they could force people to buy their commodities. Thus the outmoded economies were gradually transformed and integrated into capitalism. Not only the economies of the colonies become less and less capable of providing markets for commodities from Europe and the United States but they, in turn, generate the same overproduction.

This dynamic of capital in the 18th and 19th centuries, this alternation of crises of overproduction and long periods of prosperity and expansion and the inexorable progression of capitalism towards its decline, was described masterfully by Marx and Engels in The Communist Manifesto:

“In these crises, there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity, the epidemic of overproduction. Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed; and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce.”

At this time, because capitalism was still expanding and could still conquer new territories, each crisis led subsequently to a new period of prosperity. “The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establishes connections everywhere ... The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensively obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what is calls civilisation into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image ...”(ibid)

But already at that time, Marx and Engels saw in these periodic crises something more than an endless cycle that always gave way to prosperity. They saw the expression of profound contradictions that were undermining capitalism. By “the conquest of new markets”, the bourgeoisie is “paving the way for more extensive and more destructive crises, and by diminishing the means by which crises are prevented.”(ibid) Or: “as the mass of products and consequently the need for extended markets, grows, the world market becomes more and more contracted; fewer and fewer new markets remain available for exploitation, since every preceding crisis has subjected to world trade a market hitherto unconquered or only superficially exploited” (Wage Labour and Capital)

But our planet is a small round ball. By the early 20th century, all lands were conquered and the great historic nations of capitalism had divided up the globe. From now on, there is no question of making new discoveries but only seizing the areas dominated by competing nations by armed force. There is no longer a race in Africa, Asia or America, but only a ruthless war to defend their areas of influence and capturing, by military force, those of their imperialist rivals. It is a genuine issue of survival for capitalist nations. So it’s not by chance that Germany, having only very few colonies and being dependent on the goodwill of the British Empire to trade in its lands (a dependency unacceptable for a national bourgeoisie with global ambitions), started the First World War in 1914. Germany appeared to be the most aggressive because of the necessity, made explicit later on by Hitler in the march towards World War II, to “Export or die”. From this point, capitalism, after four centuries of expansion, became a decadent system. The horror of two world wars and the Great Depression of the 1930s would be dramatic and irrefutable proof of this. Yet even after exhausting the extra-capitalist markets that still existed in the 1950s, capitalism had still not fallen into a mortal crisis of overproduction. After more than one hundred years of a slow death, this system is still standing: staggering, ailing, but still standing. How does it survive? Why is this organism not yet totally paralysed by the toxin of overproduction? This is where the resort to debt comes into play. The world economy has managed to avoid a shattering collapse by using more and more massive amounts of debt. It has thus created an artificial market. The last forty years can be summed up as a series of recessions and recoveries financed by doses of credit. And it’s not only there to support the consumption of households through state spending ... No, nation states are also indebted to artificially maintain the competitiveness of their economies with other nations (by directly funding infra-structural investment, by lending to banks at rates as low as possible so they in turn can lend to businesses and households...). The gates of credit having been opened wide, money flowed freely and, little by little, all sectors of the economy ended up in a classic situation of over-indebtedness: every day more and more new debt had to be issued... to repay yesterday’s debts. This dynamic led inevitably to an impasse. Global capitalism is rooted in this impasse, face to face with the “wall of debt.”

The ‘debt crisis’ is to capitalism what an overdose of morphine is to the dying

By analogy, debt is to capitalism what morphine is to a fatal illness. By resorting to it, the crisis is temporarily overcome, the sufferer is calmed and soothed. But bit by bit, dependency on daily doses increases. The product, initially a saviour, starts to becomes harmful ... up until the overdose!

World debt is a symptom of the historical decline of capitalism. The world economy has survived on life supporting credit since the 1960s, but now the debts are all over the body, they saturate the least organ, the least cell of the system. More and more banks, businesses, municipalities, and states are and will become insolvent, unable to make repayments on their loans.

Summer of 2007 opened a new chapter in the history of the capitalist decadence that began in 1914 with the First World War. The ability of the bourgeoisie to slow the development of the crisis by resorting to more and more massive credit has ended. Now, the tremors are going to follow one after the other without any respite in between and no real recovery. The bourgeoisie will not find a real and lasting solution to this crisis, not because it will suddenly become incompetent but because it is a problem that has no solution. The crisis of capitalism cannot be solved by capitalism. For, as we have just tried to show, the problem is capitalism, the capitalist system as a whole. And today this system is bankrupt.

Pawel 26/11/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [5]

- Debt Crisis [22]

Rubric:

The bourgeoisie is divided by the crisis but united against the working class

- 3909 reads

In the last few months, the world economy has been going through a disaster which the ruling class has found it harder and harder to conceal. The various international summits aimed at ‘saving the world’, from G20s to endless Franco-German meetings, have only revealed that the bourgeoisie is powerless to revive its system. Capitalism has reached a dead-end. And this total lack of any solution or prospects is beginning to stir up tensions between nations, as we can see in the current threats to the unity of the Eurozone and even to the European Union itself, and within each country, between the various bourgeois cliques who make up the national political panel. Serious political crises have already broken out:

- in Portugal: on 23 March, the Portuguese prime minister, José Socrates, resigned following the refusal of the opposition to vote for a fourth austerity plan aimed at avoiding a new plea for financial aid from the EU and the IMF;

- in Spain: in April, prime minister José Luis Zapatero had to announce in advance that he would not be standing in 2012, in order to get his austerity plan adopted; but his plan with its very sharp attacks on pensions was paid for by a heavy defeat for his party, the PSOE, at the legislative elections of 20 November, resulting in a new right wing government led by Mariano Rajoy;

- in Slovakia, the prime minister Iveta Radicova was forced at the beginning October to scuttle her government in order to get the green light from parliament to a salvage plan for Greece;

- in Greece: after the surprise announcement on 1 November, just after the European summit of 26 October, of a planned referendum, which caused a huge storm among the other European powers, Georges Papandreou had to quickly give up the idea under intense international pressure and, pushed into a minority in his own PASOK party, he resigned on 9 November and handed over to the Papadopoulos team;

- in Italy: because he was seen as incapable of pushing through the drastic measures that were needed, the highly controversial president Silvio Berlusconi had to give up office on November 13, when neither mass protest in the street nor endless scandals had managed to make him go before that;

- In the USA: the American bourgeoisie has been torn over the question of raising the debt ceiling. This summer, a very short-term deal was made at the last minute. And the same question is threatening to cause trouble in a few weeks or months. Similarly, Obama’s inability to take real decisions, divisions within the Democratic Party, the vehemence of the Republican Party, the rise of the obscurantist Tea Party… show to what extent the economic crisis is undermining the cohesion of the world’s most powerful bourgeoisie.

What are the causes of these divisions?

These difficulties have three interlinked roots:

1. The economic crisis is sharpening the appetites of each national bourgeoisie and each clique. To use an image, the cake to be shared is getting smaller and smaller and the battle to grab a slice is getting more and more savage. For example, in France, the settling of scores between different parties and sometimes within the same party, through moral and financial scandals, revelations about corruption and sensational trials, are clear expressions of this ruthless competition for power and the advantages that go with it. In the same way, ‘differences of opinion’ (in other words, once the diplomatic language is decoded, ‘full-on clashes between irreconcilable positions’) which come out at the big summits are the fruit of the deadly struggle over a world market in crisis.

2. The bourgeoisie has no real solution to the catastrophe facing the world economy. Each faction, whether of the right or the left, can only put forward vain and unrealistic proposals. Each faction clearly sees the uselessness of what their rivals are proposing, but can’t see the ineffectiveness of their own. Each faction knows that the policy of the other leads to a dead-end. This is what explains the blockage over the decision to raise the debt ceiling in the USA: the Democrats know that the Republicans’ policies will lead the country to ruin… and vice versa.

This is why the appeals launched all over the world, from Greece to Italy, from Hungary to the USA, for ‘national unity’ and a sense of responsibility from all parties are all desperate and delusional. In reality, in a ship that’s threatening to go under, ‘save what you can’ predominates in the ruling class. Each one is trying to save his own skin at the expense of the rest.

3. The anger of the exploited with all these austerity plans is growing all the time and the parties in power are more and more discredited. The oppositions, whether of right or left, have no other policy to put forward and often alternate with each other after each election. And when the scheduled elections are too far away, they are being artificially precipitated by the resignation of presidents or prime ministers. This is exactly what happened several times in Europe recently. In Greece, if a referendum was proposed, it was because Papandreou and his acolytes were ejected from the national parade of 28 October by an angry crowd!

In Greece, or in Italy with the Mario Monti government, the discrediting of politicians has reached the point where the new teams in power have had to be presented as ‘technocrats’, even if these new representatives of power are just as much politicians as their predecessors (they had already occupied important posts in the previous government). This gives an indication of the level of discredit towards the ‘political class’ as a whole. For the mass of the population, for the exploited, nowhere has there been any real support for the new governments but simply a rejection of the old ones. This is confirmed by the record rate of abstention in Spain, which went from 26% to 53% of the voting population. In France, 47% of electors don’t intend to choose between the two favourites at the second round of the presidential election in May 2012, arguing that they are neither for Sarkozy nor Hollande.

Against right and left – the class struggle!

It is flagrantly clear that changing governments doesn’t change anything about the attacks on our living conditions, that all the divisions within the camp of the bourgeoisie don’t alter its unanimity when it comes to pushing through drastic austerity plans against the exploited. The proof if this that, not long ago, the period before, during and after elections used to be marked by a relative social calm. Today, there is no such truce. In Greece, there was already a new general strike and massive demonstrations on 1st December. In Portugal on 24th November we saw the biggest country-wide mobilisation since 1975, with numerous sectors (schools, post offices, banks and hospital services) closed, while in Lisbon the metro was paralysed and the main airports widely disrupted, as was the highways department. In Britain on 30 November there was the most widely followed strike in the public sector since January 1979 (around two million people). In Belgium, on 2 December, the unions called a 24 hour strike, which was again broadly followed, against the austerity measures announced by the future Di Rupo government, formed with great difficulty after 540 days in which the country was officially ‘without a government’. And the political crisis is not about to end because none of the sources of tension between the various bourgeois parties have gone away. In Italy, on 5 December, as soon as the draconian austerity plan was announced, the moderate UIL and CISL unions were obliged to call a symbolic two-hour strike on 12 December.

Only this path – the path of struggle in the street, of class against class – can lead to an effective resistance against the attacks on our living standards. What’s more, even though in France we see an arrogant right wing, symbolised by the fatuous Sarkozy, holding the reins of government, the national bourgeoisie is to some extent paralysed by the danger of class struggle. Faced with a downgrading of its AAA economic status, which could make it lose its leadership position in Europe alongside Germany, this government has only been able to introduce an austerity plan which is on a far lower level than those of other states. A significant example of this is the attack on sick pay, which is its nastiest component: the government had to manoeuvre to ensure it didn’t appear to be making too frontal an attack. Having announced that in case of absence through sickness all workers would no longer receive wages for the first day off sick, Sarkozy then had to look as though he was being less hard on the private sector (where the rule was already no pay for the first three days off work) and only maintained the measure for the public sector (who previously would not be penalised for the first day off). This shows that the French bourgeoisie, more than any other, does not dare to hit out too brutally, because of its fear of major proletarian mobilisations in a country which has historically been the detonator of social explosions in Europe, in 1789, 1848, 1871 and 1968. And the movement of ‘precarious’ youth in 2006 against the CPE, when the French government had to back down, was also a very sharp reminder of this.

The whole of this situation is inaugurating an era of growing instability in which governments can only become more and more discredited because of the attacks they will be forced to carry out. And in these political crises, behind the flimsy and short-lived agreements they may come to, the principle of ‘every man for himself’, tensions and rivalries between different factions and between competing countries can only accentuate.

We on the other hand, proletarians at work or unemployed, in retirement or in education, have to defend the same interests against the same attacks. Unlike our class enemy which is torn apart by the crisis, this situation is pushing us to respond in a more and more massive and united manner!

WP 8/12/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [5]

- Attacks on workers [23]

Rubric:

National interests are not our interests

- 1581 reads

Cameron’s veto of changes to the European Union treaty to enforce fiscal stringency and shore up the Euro has left Britain isolated, alone among the 27 member states without a seat at the table discussing the financial future of the Eurozone. For media commentators, all representing the ruling class, it has posed the question whether this has “helped protect Britain’s economic interests” against “Eurozone integration spilling over” into other areas; whether it is to the benefit of the UK financial sector, especially the City of London, and manufacturing industry, as chancellor George Osborne thinks . Or has it undermined those interests: “As for protecting the interests of the City of London … that will scarcely be achieved with Britain locked out of negotiations on the future shape of European financial regulation” (Philip Stephens commenting on https://www.ft.com [24])? Others think it a cynical ploy to sacrifice the national interest to preserve the coalition with the LibDems, which would be undermined by signing up to a treaty change requiring a referendum, and to suck up to the Eurosceptics.

Whatever the truth of the situation, the national interest is not our interest. Whether the City of London has been protected or not the bourgeoisie will demand that the working class pay for the crisis by imposing austerity measures, cutting and delaying pensions, though hundreds of thousands of job losses in both the public and private sectors, through pay cuts as faced by the electricians… Nevertheless we do need to follow what is going on, not so that we can take sides but so that we can understand the decline in the capitalist economy, so that we can be prepared for the next round of attacks, so that we do not fall for all their lies.

In relation to the Eurozone it is clear that Britain finds itself in an impossible situation. On the one hand, it relies on the health of the Eurozone for much of its trade, and on the other hand it wants to safeguard its huge financial sector from interference, and benefit from the freedom of having its own currency, to be in the EU at the same times as maintaining its fiscal sovereignty. And as a declining power it is limited in its ability to defend its interests, even when ‘punching above its weight’. As these events have only just happened we will return to this question in a future online article.

Alex 10/12/11

Recent and ongoing:

- Internationalism [25]

- Britain in the EU [26]

Rubric:

What is the future for the struggles in Egypt?

- 1652 reads

Growing poverty, the brutal blows of the economic crisis, the yearning for freedom from a regime of terror, indignation about corruption, are continuing to fuel revolt among the populations of the Middle East, especially in Egypt[1].

After the huge mobilisations last January and February, since 18 November we have again seen the occupation of Tahrir Square and big new demonstrations. This time, the target of the anger has mainly been the army and its leaders. These events prove, contrary to what we are told by the bourgeoisie and its media, that there was no ‘revolution’ at the beginning of 2011 but a massive movement of protest. In the face of this movement, the bourgeoisie was able to change the country’s masters: the army has been acting exactly like Mubarak and nothing has changed in the conditions of exploitation and repression for the vast majority of the population.

The bourgeoisie uses lies and repression against thedemonstrations

All the main Egyptian cities have again seen this general discontent with living conditions and with the omnipresence of the army in the maintenance of order. The climate of protest has been as hot in Alexandria and Port-Said in the north as in Cairo; there have been important confrontations in the centre of the county, in Suez and Qena, and in the south, in Assiut and Aswan, and in the west in Marsa Matrouh. The repression has been ruthless: 42 deaths and around 200 wounded, even according to the official figures. The army does not hesitate to hurl its anti-riot squads against the crowds, using highly toxic forms of tear gas. Some people have died from breathing it in. Some of the dirty work of repression has been sub-contracted. Specialist snipers have been using live rounds with impunity. A large number of young demonstrators have been cut down by these mercenaries. The police, to make up for the fact that they only have rubber bullets at their disposal, have been systematically firing at people’s faces. There is a shocking video going the rounds and which has provoked a great deal of anger among demonstrators; in it you can hear a cop shouting “take out their eyes!”, congratulating a colleague “You got him in the eye, well done my friend!” (L’espress.fr). And many demonstrators have indeed lost an eye. On top of this we have to add arrests and torture. Often the troops are accompanied by “militia”, the “baltaguis”, who are used in an underhand way by the regime to sow disorder. Armed with iron bars and wooden clubs their tactic is usually to isolate demonstrators and beat them up savagely. Last winter they were the ones who burned tents in Tahrir Square and played a hand in numerous arrests (LeMonde.fr).

Again, contrary to what the media would have us believe, women, who are today playing a big part in the demonstrations, are often sexually assaulted by the security forces and are for example frequently subjected to horrible humiliations like ‘virginity tests’. In general they are treated with respect by the demonstrators, although assaults on some western journalists (like the one against Caroline Sinz, a journalist from France 3 in which young ‘civilians’ were implicated) have been widely publicised. However, “the clashes in Tahrir should not make us forget that, on the Square, a new relationship between men and women is being established. The simple fact that the two sexes can sleep in close proximity in the open air is a real novelty. And the women have seized hold of this new freedom. They have become an integral part of the struggle” (Lepoint.fr).

We are being led insidiously to think that the occupants of Tahrir are hooligans because they “don’t care about the elections” and so are endangering the “transition to democracy”. This from the same media which, having supported Mubarak and his clique for so long, then welcomed the “liberating” military regime, taking full advantage of the population’s illusions in the army.

The key role of the army for the Egyptian bourgeoisie

Even if the army is being strongly discredited today, the main target of popular anger is the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and its leader Hussein Tantawi. The latter, minister of defence for ten years under Mubarak, and seen as a clone of the dictator, has been told by huge crowds: “leave”. But the army, Mubarak’s historic base, is a solid bulwark and continues to hold onto the reins of the state. It never stops manoeuvering to ensure its position with the backing of all the big powers, especially the USA, since Egypt is a vital piece in the latter’s strategy for controlling the Middle East, a factor of essential stability in its imperialist policies in the region, above all with regard to the Israel-Palestine conflict. By claiming that the “the army has gone back to the barracks”, the bourgeoisie has for the moment managed to hide the most essential thing. Not without reason, the daily Al Akhbar warned that “the most dangerous thing that could happen is the deterioration of the relationship between the army and the people”. In effect, the army has not only had a major political role since the arrival in power of Nasser in 1954, forming an indispensable pillar to the regime; it also has a key economic role, directly running a number of big enterprises. Since the defeat in the Six Day War against Israel in 1967, and above all since the Camp David Accords in 1979, when tens of thousands of soldiers were demobilised, the bourgeoisie has been encouraging large parts of the army to turn themselves into entrepreneurs, out of fear that the demobilisation would mean a heavy extra burden on the labour market, which already suffered from massive endemic unemployment: “It began with the production of material for its own needs: arms, accessories and clothing, then, in time, it launched itself into different civil industries and invested in agricultural enterprises, which were exempt from taxes” (Libération, 28.11.2011), investing 30% of production and oiling all the wheels of Egyptian capital. Thus, “the SCAF can be seen as the administrative council of an industrial group composed of firms held by the (military) institution and managed by retired generals. The latter are also ultra-present in the upper echelons of the administration: 21 of the 29 governorships of the country are led by former army and security forces officers”, according to Ibrahim al-Sahari, a representative of the Cairo Centre for Socialist Studies, who adds: “we can understand the anxiety of the army faced with the social troubles and insecurity which have developed in recent months. There is a fear of the contagion of strikes in its enterprises, where its employees are deprived of all social and trade union rights, and where any protest is seen as form of treason” (cited by Libération, 28.11). There is good reason for the iron fist with which it rules the country.

Courage and determination, but the limits cannot be breached in Egypt

The continuation of the repression and the protests of the “committees of families of the wounded” were the focus of the anger against the army, but the motivation was not simply to call for the military to give up power, for more democracy and elections. The worsening economic situation and the black hole of poverty are also pushing the demonstrators onto the streets. In conditions of mass unemployment it is becoming increasingly difficult for people just to feed their families. And it is precisely this social dimension which the media are trying to hide. We can only salute the courage and determination of the demonstrators, who have been standing barehanded against state violence. Their only ammunition is paving stones and rubble, against cops armed to the teeth. The demonstrators have shown a great will to organise themselves for the needs of the struggle. They are obliged to organise and they have shown considerable ingenuity in the face of the repression. Makeshift hospitals have been set up all over the squares, with human chains serving as ambulances. Scooters are used to take the wounded to safety. But the situation is not the same at the time of the fall of Mubarak, when the proletariat played a decisive role, when the rapid extension of massive strikes and the rejection of the official trade unions were largely responsible for the military chiefs, under the pressure of the US, deciding to dump Mubarak. The situation for the working class is very different now. Since April, one of the first measures taken by the army was to toughen laws “against strike movements liable to disturb production in any group or sector, so undermining the national economy” , and to call for the unions to get a stronger grip. This law included punishments of a year in prison and fines of up to 80,000 dollars (in a country where the minimum wage is 50 euros!) for strikers or anyone inciting strikes.

While the movement today has been rejecting the power of the army, it is still weakened by many illusions. First and foremost, because it has been calling for a “civil democratic” government. It’s true that the Muslim Brotherhood and the salafists, who see themselves on the verge of forming such a “civil government” (which will just be a facade because real power will remain in the hands of the army) have distanced themselves from the protest movement and have refrained from calling for demonstrations, preferring to negotiate their political future with the military. Nevertheless, the mirage of “free elections”, the first for 60 years, seems to be momentarily sapping the anger. However, even if they are real, these democratic illusions are not as strong as the bourgeoisie would like us to think: in Tunisia, where we were told that 86% voted in the elections, this was only out of the 50% who are entered on the electoral lists. It’s the same in Morocco where the rate of participation in the elections was 45% and in Egypt, where the figures are still very vague (62% are entered but there were only 17 million voters out of 40 million).

Today, leftists everywhere are shouting “Tahrir shows us the way!” as if it was just a question of copying this model of struggle everywhere, in Europe as well as America. In fact this is a trap for the workers. Not everything can be taken from these struggles. Their courage and determination, the now famous slogan “we are not afraid”, the will to gather en masse in the squares to live and struggle together... all this really is an invaluable source of inspiration and hope. But also, and perhaps above all, we have to be aware of the limits of this movement: the democratic, nationalist and religious illusions, the relative weakness of the workers... These obstacles are linked to the limited historical and revolutionary experience of the working class in this region of the world. The social movements in Egypt and Tunisia have given to the international struggle of the exploited the maximum of what they are capable of achieving for now. They are reaching their objective limits. It is now up to the most experienced sections of the proletariat, living in the countries at the heart of capitalism, and especially Europe, to take up the torch of struggle against this inhuman system. The mobilisation of the indignados in Spain is part of this indispensable international dynamic. It began to open up new perspectives with its open and autonomous general assemblies, with its debates where there were often interventions that were clearly internationalist and which denounced the charade of bourgeois democracy. Only such a development of the struggle against poverty and the draconian austerity plans at the countries at the centre of capitalism can open up new perspectives for the exploited not only in Egypt but in the rest of the world. This is the precondition for offering humanity a future.

WH 1/12/11

[1]. This is also obviously the case in Syria where the regime has killed over 4000 people (including over 300 children), bloodily repressing demonstrations since March. See our article in this issue.

Recent and ongoing:

- Egypt [27]

- social revolts [28]

Rubric:

Imperialist manoeuvres go up a gear

- 2370 reads

The following article, by a supporter of the ICC, was written before the recent attack on the British Embassy in Iran. On 29 November student protesters broke into the embassy building causing damage to offices and vehicles. Dominick Chilcott, the British ambassador, in an interview with the BBC, accused the Iranian regime of being behind the ‘spontaneous’ attacks. In retaliation the UK expelled the Iranian embassy in London.

These events are another moment in the growing tensions in the Middle East between the west and Iran. Firstly around the issue of nuclear weapons and secondly over Syria.

The recent IAEA report into Iran’s nuclear programme said Iran is developing a nuclear military capability. In response the UK, Canada & the USA have introduced new sanctions. In recent days Iran claims that it has shot down a US drone attempting to gather military intelligence.

In Syria the article mentions the collaboration between the Assad regime and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps in the massacre of the Syrian populace. They also had a hand in the sacking of the British embassy in the guise of their youth division, the Basij.

As well as inter-imperialist rivalries we should not forget internal rivalries within the national bourgeoisies themselves. This summer it became clear that there was a growing rift between Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Despite Ahmadinejad’s anti-Semitic rants and sabre rattling rhetoric he represents a faction of the Iranian bourgeoisie that wants to maintain some sort of relationship with the west. Khamenei has had some of Ahmadinejad’s close allies arrested and supporters within the government sacked. In response Ahmadinejad went on strike for 11 days refusing to carry out his duties. The recent events around the sacking of the British embassy are being seen by some media analysts as part of this feud. Khamenei and his conservative supporters are considered to be behind the attacks as a way of undermining Ahmadinejad’s more conciliatory policy. This in turn will undermine him in the eyes of the Iranian voters with the next elections coming in 2012. (see: uk.reuters.com/article/2011/12/02/uk-iran-britain-policy-idUKLNE7B101120111202)

With tensions between Iran and the west growing there is speculation about war. Are the workers in the Middle East and in the west ready to be mobilised to support another major war? Workers the world over are being forced to take the burden of the financial crisis on their shoulders and are beginning to fight back. War means more austerity, more violence against workers, more despair. Workers have no stake in these bloody imperialist massacres. The only way forward is the destruction of capitalism itself.

After eight months of protest, originally part of a regional and international movement against oppression, unemployment and misery, here involving Druze, Sunnis, Christians, Kurds, men, women and children, events in Syria have continued to take a darker turn with new, dangerous developments.

If, in defending their own interests and strategies, the USA, Britain and France are wary of a direct attack against Iran, then contributing to an assault on its closest ally, the Assad regime in Syria, is, in the rationale of inter-imperialist rivalries, the next best thing in pursuing their squeeze on the region and the Khamenei regime. The brutal security forces of Assad, backed with logistical support of “3-400 Revolutionary Guard Corps” from Iran (Guardian, 17.11.11), has massacred thousands of the populace and given rise to the lying, hypocritical ‘concern for civilians’ from the three main powers of the anti-Iranian front above. As in Libya, the US is ‘leading from behind’, this time having pushed the Arab League (splitting off Assad’s Algerian, Iraqi and Lebanese allies), of which Syria was a leading force, to suspend its membership and issue it with subsequent humiliating deadlines.

At the forefront of this phoney concern for life and limb is the murderous regime of Saudi Arabia, which a while ago sent a couple of thousand of its crack troops, in British-made APCs, to crush protest in Bahrain as well as to protect American and British interests and bases there. Underlying the hypocrisy, the confirmation of Syria’s suspension for its ‘bloodshed’ was made by the Arab League meeting in the Moroccan capital Rabat on November 16th, as that country’s security forces were attacking and repressing thousands of its own protesters. There are wider imperialist ramifications to the Arab League action in that its decisions have been condemned by Russia but supported by China.

It’s not only the Arab League that the USA and Britain are pushing forward from the corridors but the regional power of Turkey which was also involved in meetings in Rabat. After seemingly dissuading Turkey from setting up some sort of buffer zone or ‘no-fly zone’ on the Turkish/Syrian border, the US administration has now moved on with Ben Rhodes, Obama’s deputy national security adviser, saying last week “We very much welcome the strong stance that Turkey has taken...” The exiled leader of Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood also told reporters last week that Turkish military action (to protect civilians of course) would be acceptable (Guardian, 18/11/11). The possibility of a buffer zone along the now heavily militarised Turkish/Syrian border would see the shadowy ‘Free Syrian Army’, largely based in Turkey (as well as Lebanon) and, at the moment, greatly outnumbered by the Syrian army, able to muster and move around with much heavier weaponry. Within this convergence of imperialist interests, this nest of snakes – containing inherent and further problems down the road – is the USA, Britain, France, the majority of the Arab League, Leftists, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi jihadists of Syria who have also taken a greater role in the anti-Assad opposition. Further regional destabilisation and potentially greater problems are evidenced in Turkish President Gul warning Syria that it would pay for stirring up trouble in Turkey’s Kurdish south-east and “Washington’s renewed willingness to turn a blind eye to Turkish military incursions against Kurdish guerrilla bases in northern Iraq” (Guardian, 18/11/11). All this instability, fed by all these powers and interests, make a military intervention by Turkey into Syrian territory all the more likely.