International Review no.54 - 3rd quarter 1988

- 3449 reads

20 years since 1968: The evolution of the proletarian political milieu, II

- 2486 reads

In the mid 1970s, the proletarian milieu was polarized between two currents who, in a caricatural manner, were the product of the theorization not of the strengths of the Italian[1] and German-Dutch[2] lefts, but for their weaknesses - particularly with regard to a question that was crucial toa milieu re-emerging after decades of obliteration from the historical scene: the question of organization. On the one hand, there was the councilist current which rends to deny the necessity for revolutionary organization, and on the other hand the Bordigist current, represented in particular by the Parti Communiste Internationale (Programme Communiste), which makes the party the mechanical remedy for all the difficulties facing the working class. The first current was to have its hour of glory in the turmoil of the events of ‘68 and the years that followed but it encountered all kinds of problems with the reflux in the class struggle in the mid-70s; the second, having been ever so discreet during the period of the development of the struggle, was to gain a new echo during the reflux, in particular with elements who had come out of leftism. In the second half of the seventies the councilist pole collapsed whereas the PCI (Programme) thrust itself arrogantly forward: it was the Party and nothing existed outside of it.

The proletarian political milieu was extremely dispersed and divided. The question posed to it increasing urgency - and one intimately linked to the question of organization - was that of the need to develop contacts between the existing groups on the basis of a revolutionary coherence, in order to accelerate the process of clarification indispensable for the regroupment of revolutionary forces. The ICC, in continuity with the work of Revolution Internationale, showed the way forward in 1974-75 and the Manifesto it published in 1976 was an appeal to the whole proletarian movement to work in this spirit:

"With its still modest means, The International Communist Current has committed itself to the long and difficult task of regrouping revolutionaries internationally around a clear and coherent program. Turning its back on the monolithism of the sects, it calls upon the communists of all countries to become aware of the immense responsibilities which they have, to abandon the false quarrels which separate them, to surmount deceptive divisions which the old world has imposed on them. The ICC calls on them to join in this effort to constitute (before the class engages in its decisive struggles) the international and unified organization of its vanguard.

The communists, as the most conscious fraction of the class, must show it the way forward by taking as their slogan: ‘Revolutionaries of all countries, unite'." (Manifesto, published with the ICC Platform)

It was on this shifting context of a political milieu in a state of decantation, profoundly marked by dispersal and the weight of sectarianism that Battaglia Comunista was to call in 1977 for an international conference of groups of the communist left[3].

In 1972, Battaglia Comunista had refused to associate itself to the appeal by Internationalism (USA), proposing the development of international coreespondence with the perspective of an international conference, an appeal which had initiated the dynamic which had led to the formation of ICC. At the time, in the aftermath of 1968, BC had replied

" - that we can't consider that there was a real development of class consciousness

-- that even the flowering of groups expresses only the malaise and revolt of the petty bourgeoisie

-- that we have to admit the world is still under the heel of imperialism."

What led to the subsequent change of attitude? A fundamental question for BC: the ‘social democratization' of the Stalinist CPs. BC took the ‘Eurocommunist' tura of the CPs, a purely conjunctural tura of the mid-‘70s, as we can now see clearly with hindsight, as the reason for their new attitudes towards the political milieu. It was in order to discuss this fundamental question that Battaglia proposed the holding of a conference. Furthermore, there were no political criteria for defining the proletarian milieu in BC's letter of appeal, and Battaglia excluded from its invitation the other groups of proletarian milieu in Italy such as PCI (Program) or Il Partito Comunista.

Despite the orientation towards the holding of the conferences, Battaglia wanted to remain ‘master of its own house.'

However, despite the lack, of clarity in the appeal, the ICC, in conformity with the orientations already embodied in its own history and reaffirmed in the Manifesto published in January 1976, responded positively to this call was to act jointly with BC in promoting this conference by proposing political criteria demarcating the organizations of the proletarian milieu from those of the bourgeoisie; by calling for the appeal to be opened out to the organizations ‘forgotten' by Battaglia; by trying to situate this conference within a dynamic towards political clarification within the communist milieu, the necessary step towards the regroupment of revolutionaries.

The dynamic of the international conferences of the groups of the communist left

The First Conference[4]

Several groups agreed in principle to BC's appeal: the FOR in France and Spain (Formento Obrero Revolucionario); Arbetarmakt in Sweden; the CWO (Communist Workers' Organization) in Britain[5] the PIC (Pour Une Intervention Communiste) in France. But this agreement remain platonic and only the ICC participated actively alongside BC at the first conference, whereas under various more or less valid pretexts, but which all expressed an underestimation of the importance of the conference, the other groups shone by their absences.

As for the apostles of councilism and Bordigism - Spartakusbond (Holland) and the PC (Program)[6] - they were uninterested in such conferences, taking refuge in a splendid, sectarian isolation.

However, although only two of the organizations (BC and the ICC) actually took part in this first conference (which clearly expressed the reality of the prevailing sectarianism); although the criteria for participation were still vague and needed to be made much more precise; although there was a lack of preparation, despite all this, this was still a great step forward for the whole proletarian milieu. Far from being a closed debate between two organizations, this first conference demonstrated to the whole proletarian milieu that it was possible to create a framework for the confrontation and clarification of divergent positions. The importance of the questions raised proved this amply:

-- analysis of the development of the economic crisis and the evolution of the class struggle;

-- the counter-revolutionary function of the so-called ‘workers' parties' -- SPs, CPs, and their leftist acolytes

-- the role of the trade unions;

-- the problem of the party;

-- present tasks of revolutionaries;

-- conclusions on the significance of this meeting.

However, an important weakness of this conference and of the one which followed, was its inability to take a conscious position on the debates which had animinated it; thus the draft joint declaration proposed by the ICC, synthesizing the agreement and disagreements which had emerged, notably on the union question, was rejected by BC witihout an alternative proposal.

The publication in two languages ( Italian and French) of the texts contributed to the conference and the proceedings, aroused considerable interest in the proletarian milieu and made it possible to broaden the dynamic opened up by the first conference.

This was to be concretized a year and a half later, at the end of ‘78, when the second conference was held.

The Second Conference[7]

This conference was better prepared and organized than the first, both from the political and organizational points of view. The invitation was made on the basis of more precise political criteria:

"- recognition of the October Revolution as a proletarian revolution;

- recognition of the break with social democracy made by the first and second congresses of the Communist International;

- rejection without reservation of state capitalism and of self-management;

- rejection of all the Communist and Socialist parties as bourgeois parties;

- orientation towards and organization of revolutionaries which refer to the marxist doctrine and methodology as the science of the proletariat."

These criteria - which were of course insufficient for establishing a political platform for regroupment, and the last point of which certainly needed to be made more precise, were by contrast amply sufficient for demarcating the proletarian milieu and giving a framework for fruitful discussion.

At the second conference held in November 1978, five proletarian organizations were to participate in the debates: the PcInt (Battaglia) from Italy, the CWO from Britain, the Nucleo Comunista Internazionalista from Italy, Fur Kommunismen from Sweden , and the ICC which at time had sections in nine countries. The group Il Leninista sent texts as a contribution to the debates without, being able to participate physically at the conference , while Arbetarmakt of Sweden and OCRIA in France gave a purely platonic support to the conference.

As for the FOR, this has something of a particular case, because having given its full support to the first conference, having sent texts for the preparation of the second , and having come to take part, it performed a piece of theatre at the beginning: under the pretext of not being in agreenent with the agenda because it contained a point on the economic crisis, whose existence the FOR denies in a surrealist manner , it made a spectacular exit.

As for the epigones of councilism and Bordigism, they preserved their rejection of the conferences: Spartakusbond of Holland, imitated by the PIC in France, because they rejected the necessity for the party, and the PCI's (Program and Il Partito Comunista in Italy) because they considered themselves to be the only parties in existence, and thus that outside them no proletariat organizations could exist.

The agenda of the conference bore witness to the militant spirit that animated it:

-- the evolution of the crisis and the perspectives it opens up for the struggles of the working class;

-- the position of communists on so-called 'national liberation' movements;

-- the tasks of revolutionaries in the present period.

The second international conference of the groups of the communist left was a success; not only a larger number of groups took part, but also because it made it possible to more clearly deliniate the political agreements and disagreements between the different participating groups. By enabling the various organizations present to get to know each other better, the conference offered a framework of discussion which made it possible to avoid false debates and to push for the clarification of real divergences. In this sense the conferences were a step forward within the perspective of the regroupment of revolutionaries, which while not an immediate short-term prospect is certainly on the historical agenda given the dispersed situation of the proletarian milieu after decades of counter-revolution.

However , the political weaknesses which the proletarian milieu suffers from also weighed heavily on the conferences themeselves. This expressed itself in particular in the inability of the conferences to avoid remaining dumb -- ie in the capacity of the participating groups to take a collective position on the questions under discussion, in order to make clear what point they had reached. The ICC put forward resolutions with this aim, but aside from the NCI met with the refusal of the other organizations present, and notably of Battaglia and the CWO. 'I'his attitude expressed the climate of distrust which infests the communist milieu, even those parts of it most open to confrontation, and holds back the much-needed process of political clarification.

In these conditions it wasn't surprising that the ICC's proposal to vote a resolution denouncing the sectarianism of the groups who refused to participate in the conferences was rejected by the other groups both at the first and second conferences. Obviously this touched a raw nerve.

Those weaknesses were unfortunately to be concretized after the second conference in the polemics launched by Battaglia and the CWO who labelled the ICC as 'opportunist' and denied the the existence of a problem of sectarianism. For them, the denunciation of sectarianism was just a way of denying the real political divergences. This positition of Battaglia and of the CWO fails to see that sectarianism is a political question in its own right since it expresses a tendency to lose sight of an essential issue: the role of the organization in one of its most decisive aspects, that is its work towards the regroupment of revolutionaries. In denying the danger of sectarianism in those organizations are poorly equipped to deal with it in their own ranks, and unfortunately this was to be manifested clearly at the third conference.

The Third Conference[8]

The third conference was held in spring 1980 at a time when the workers' struggles of the preceding year had shown that the reflux of the mid-70s was over; at a time, as well, when the intervention of Russian troops in Afghanistan had shown the reality of the threat of world war, which highlighted the responsibility of revolutionaries in a very sharp manner.

New groups had associated themselves to the dynamic of the conferences: the Nuclei Leninista Internazionalisti which was the product of the fusion of the NCI and Il Leninista in Italy, who had already associated themselves to the second conference; the Groupe Communiste Internationaliste was the product of a Bordigist-type split from the ICC in 1979, L'Eveil Internationaliste in France, which came from a break with Maoism, now in an advanced state of decomposition; the Marxist Workers Group from the USA which associated itself to the ccnference without being able to take part physically. However despite the grouing echo the conferences were having within the revolutionary miliue, the third international conference of groups of the communist left ended in failure.

The ICC's call for the conference to adopt a joint resolution on the danger of imperialist war in the light of events in Afghanistan wa s rejected by BC, the CWO, and by l'Eveil, because even if the different groups had a common position on this question, for them it would have been 'opportunist' to adopt such a resolution, 'because we have disagreements on the role of the revolutionary party of tomorrow.' The content of this brilliant 'non-opporcunist' reasoning was a follows: because revolutionary organizations haven't managed to agree on all the questions, they musn't speak about those they have been agreed on for a long time. The specificities of each group take precedence, as a matter of principle, over what is common to all. And this is precisely what we mean by sectarianism. The silence, the absence of any collective position taken by the groups during these three conferences, was the clearest demonstration of how sectarianism leads to impotence.

Two debates were on the agenda of the third conference:

-- the point reached by the crisis of capitalism and the perspectives flowing from this;

-- the perspectives for the development of the class struggle and the resulting tasks of revolutionaries,

The debate on the second point of the agenda permitted the opening up of a discussion on the role of the party, which had been one of the points discussed at the second conference. 'I'his question on the role of the party is one of the most serious and important facing today's revolutionary groups, particularly with regard to the appreciation one has of the conceptions of the Bolshevik party in the light of the historic experience accumulated since and through the Russian Revolution.

And yet Battaglia and the CWO, out of impatience, or fear, or (and this is unfortunately most probable ) out of miserable opportunist tactics -- and even though at the previous conference they had declared that this question would "need a long discussion" - were to refuse to carry on this debate on the problem of the party. Using as a pretext, the so-called , 'spontaneist' conceptions of the ICC, they declared the question closed and made their own position a criterion for adhesion to the conferences, thus provoking the exclusion of the ICC and the dislocation of the conferences. In breaking the dynamic which has made it possible to restore the links between the different parts of the proletarian milieu and to push the whole milieu towards the clarification needed for the regroupment of revolutionary forces, the CWO and BC bear a heavy responsibility for reinforcing the difficulties faced by the milieu that inevitably resulted from all this.

The CWO and BC thus showed the same irresponsibility as the GCI who only came to thed third conference to denounce the very principle of it and to fish for recruits in the most shameful manner.

The outbreak of the mass strike in Poland three months afte the failure of the conference simply highlighted the irresponsibility of these groups who seem to believe that they exist only in relation on to their own egos and who forget that it is the working class which has produced them for its needs. These 'instrasigent' defenders of the party forget that the first task of the party is not to turn in on itself in sectarian manner, but is on the contrary to show a will for political confrontaton in order to accelerate the process of clarification within the proletarian milieu and thus to reinforce its capacity for intervention within the class.

The pseudo-fourth conference which took place later on had nothing to do with the dynamic that had informed the first three. The CWO and BC found a third person to act as a candlestick for the candle that illumenated their tryst: the UCM, a group that has to becone the 'Communist Party of Iran.' This nationalist group, hardly emerging from Stalinism, was certainly a more valid interlocutor for Battaglia and the CWO than the ICC -- perhaps because it defended a 'correct' position on the party, unlike the ICC? Sectarianis has its vicissitudes: it leads to the most downright opportunism and in the end to the abandonment of principles.

Balance Sheet of the Conferences

The first acquisition of the conferences is that they took place at all.

The international conferences of groups of the communist left were a particularly important moment in the evolution of the international proletarian milieu which re-emerged after 1968. They made it possible to create a framework of discussion among various groups who directly participated in their dynamic, and so led to a positive clarification of the debates which animated the milieu as a whole, offering a political reference point f'or all the organizations and elements looking for a revolutionary political coherence. The bulletin published in three languages after each conference, containing the various written contributions and the proceedings of all the discussions have remained an indispensable reference for all the groups or elements who have since come to revolutionary positions.

In this sense, despite the ultimate failure of the conferences, they represented an eminently fruitful moment in the evolution of the proletarian political milieu, allowing the groups to get to know each other better, creating a framework which permitted a positive process of political decantation and clarification, which was concretized in the development of a dynamic towards regroupment. Thus within the conferences themselves this dynamic took shape through the fusion of the NCI and Il Leninista into the NLI; through the decantation of elements from Arbetarmakt and the majority of the group Fur Kommunismen in Sweden who moved towards the ICC and later on formed its section in this country; through the rapprochement between Battaglia and the CWO who later regrouped to form the International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party.

The positive role of the conferences and the growing echo they received weren't only manifested in the increasing numbers of groups who participated in them. They also showed all the groups in the milieu the value of such meetings and offered an example of how to proceed. Proof of this was the Oslo conference of September 1977 which regrouped a number of Scandinavian groups, and in which the ICC participated; even if it was held on a much looser basis, it expressed a need felt within the international proletarian milieu.

But with the next reflux in workers' struggles, the positive role of the conferences has to be demonstrated, paradoxically, by the crisis in the milieu which followed the failure of the third conference.

The crisis of the proletarian political milieu

At the same time the conferences were taking place, the political milieu at the end of the 70s was marked by a dual phenonenon: on the one hand the collapse of the councilist movement, which had been the dominant pole at the beginning of the decade, and on the other by the development of the PCI (Programme) which became the most developed organization of the proletarian milieu.

The Political Degeneration of the Bordigist PCl

If the PCI (Programme) became the most developed organisation of the political milieu, this wasn't just through its international existence in a number of countries: Italy, France, Switzerland, Spain, etc, publishing in Fr ench, Italian, Engish, Spanish, Arabic, German ... but also through its political positions which in a period of reflux in the class struggle met with a certain success, not only with elements produced by the decomposition of leftism but also within the existing proletarian mileu.

The incapacity of ‘councilism' to resist the reflux in the struggle was a concrete demonstration of the bankruptcy into which one is led by rejecting the need for a political party of the working class, by the profound underestimation of the question of organization which this position implies. The PCI's insistence of the necessity for the party was perfectly correct. But it held a ‘substitutionist' conception of the party, one pushed to the limits of absurdity, .in which the party is everything and the class nothing. The conception was developed during the depths of the counter-revolution after World War Two when the working class was more mystified than ever before; it was in effect the theorization of the weakness of the proletariat. The party was presented as the panacea for all the difficulties of the class struggle. At a time when the struggle was in reflux, the increasing echo of the PCI's position on the party was the reflection of doubts about the working class.

This doubt about the revolutionary capacities of the working class was to be strikingly expressed in the PCI's accelerating slide oportunism during these years. Whereas the workers in the advance countries were supposed to be benefitting from the dividends of imperialism, bribed into passivity, the PCI saw the development of revolutionary potential of the peripheries of capitalism, in so-called ‘national liberation' struggles. This nationalist inclination was to lead the PCI to support the KhmerRouge terror in Cambodia, the nationalist struggle in Angola, and the ‘Palestine revolution' (along with the PLO), while in France, for example, the priority the PCI gave to intervention in the struggles of ‘immigrant' workers tended to reinforce the weight of nationalist illusions. Bordigism's false conceptions on the question of the party, on the national question, but also on the union question were so many doors opened to penetration of the dominant ideology. The development of Bordigism as the main political pole within the working class was an expression of the reflux in the class struggle and of its theorization. In these conditions, it wasn't surprising that the PCI (Programme), which preferred to open its doors to bourgeois leftism rather than discuss within the revolutionary communist milieu, paid for this attiude through an accelerating political degeneration, through an abandonment of the very principles that had presided over the PCI's birth.

The Debates Within the Proletarian Milieu at the Beginning of the ‘80s

If t.he PCI (Programme) pushed its positions to the point of caricature, the erroneous views which lay beneath them and which were descended from the points at issue in the Third International were present in the general conceptions of other groups, even if they didn't reach the same level of aberration. This was particularly true of those who, like Bordiga's PCI, had their origin to various degrees in the Partito Comunista Internazionalista f'ormed mainly in Italy at the end of the Second Imperialist World War; for exanple, the PcInt (Battaglia), which is the continuator with the clearest revolutionary principles; the PCI (Il Partito) which split from Programme in 1973, or the NCI.

In these conditions , it's not surprising that the debates which took place within the conferences tended to be polarized around the same f'undauental questions: the party, the unions, the national question, because these were the questions of the hour, determined by the world situation and the proletarian milieu's own history. In the conferences, the NLI (NCI and Il Leninista) was the group closest to Bordigist positions; Battaglia made concessions to these conceptions on the national and union questions, while on the party question, we've seen that is was used as a pretext for sabotaging the dynamic of the conferences, with the CWO during the course of the meetings undergoing which led it from a platform very similar to the ICC's towards the conceptions of Battaglia.

The Acceleration of History at the Beginning of the ‘80s and the Decantation within the Political Milieu

With the failure of the conf'erences, we thus see a profoundly divided proletarian milieu facing a very powerful acceleration of history at the beginning of the ‘80s. This was marked by:

-- the international development of the wave of workers' struggles which put an end to the reflux which had succeeded the wave begun in1968, and which culminated with the mass strikein Poland, its brutal repression, and so with another reflux in the international struggle;

-- the exacerbation of inter-imperialist tensions between the two big powers, with the Russian intervention in Afghanistan, the intense war propaganda unleashed in response, and the acceleration of the arms race;

-- the deepening crisis of the world economy; the American recession of 1982, the strongest since the ‘30s, led the whole world economy into the recession.

While the lessons of history may escape some people, there's no escape from history itself. Inevitable, a political decantation took place within the proletarian milieu; historical experience passed its judgment.

The wave of struggles which broke out at the end of the ‘70s was to pose very concretely the necessity for the intervention of revolutionaries.

The struggle of the steel workers of Lorraine and the north of France in ‘79, the steelworkers strike in Britain in 1980, and finally the mass strike of the workers in Poland in 1980 were to come up against the radicalization of the union apparatus, against base unionism. The struggles were to be derailed and defeated and the victory of Solidarnosc signified the weakening of the working class, which made the repression possible. The abortion of the international wave and the brutal reflux which followed were to be a test of truth for the proletarian political milieu.

In these conditions, where the failure of the conference no longer allowed the proletarian milieu to have a place where the confrontation of political positions could be carried on, the inevitable process of decantation didn't express itself in a dynamic towards regroupment. On the contrary, as history speeded up, political selection took place in a vacuum, through a hemmorhage of militant energies caught up in the debacle of organization incapable of responding to the needs of the working class. The proletarian political milieu entered into a phase of crisis[9].

The question of Intervention: the Undersestimation of the Role of Revolutionaries and the Underestimation of the Class Struggle

Faced with the necessity to intervene, the proletarian milieu was to act in a dispersed manner, showing the profound underestimation of the role of revolutionaries which infects it. The intervention of t.he ICC within the workers' struggles, and notably with the events of Longwy and Denain in France, was to be the focus of the criticism of the whole proletarian milieu[10], but it had at least the merit of having taken place. Outside the ICC, the political milieu shone by its absence from the terrain of workers' struggles: the PCI (Programme), for example, the main organization which have been characterized by its activism in the previous period, didn't see the class struggle in front of its faces; hypnotized by its thordworldist dreams, it also continued with its slide into trade unionism.

The weakness of the intervention of the political milieu expressed its profound underestimation of the class struggles, its inexperience, it's lack of understanding of its tasks. This was crystallised in particular around the union question, not only throug the political concessions towards trade unionism expressed to varying degrees by the groups which came out of the Pcint of 1945, but also through a tendency to reject the importance and positive nature of the struggles going on simply because they hadn't broken away from the union prison, or the ‘economic' terrain. Thus, paradoxically, the councilist tendencies and those descended from the Pcint of 1945 came together in rejecting the importance of the workers' struggles because of the continuing hold of the unions. Programme Communiste, Battaglia, and many others such as the FOR, continued to deny the reality of the development of the class struggle since ‘68 and to affirm that the counter-revolution still ruled. In this context, the CWO was to stand out with its call for insurrection in Poland, but this serious one-off over-estimation simply expressed the same incomprehensions which unfortunately dominated the political milieu outside the ICC.

The Explosion of the PCI (Programme)

The defeat in Poland, the international reflux in the class struggle, which along with the downward plunge of the economy were so many sharp reminders of reality, were to ravage a milieu which hadn't seen how to take up its historic tasks. Those most affected by the crisis of the political milieu were first of all to be the ones who had from the beginning rejected the dynamic of the conferences. Spartacusbond in Holland and the PIC in France (as well as its successor, the inaptly name Groupe Volonte Communiste) were to be blown away like straws in the wind by this acceleration of history, but this made little impact. On the other hand, the explosion of PCI (Programme) was to be transformed the landscape of the political milieu. The monolithic Bordigist party, the most ‘important' organization in the milieu, paid the price for long years of political sclerosis and degeneration, and for the sectarian isolation which had accelerated this process. It broke apart under the impulsion of the leftist elements of El Oumani; there was a brutal hemorrhage of its militant forces, the majority of whom were lost in disorientation and denmoralization. From this crisis the PCI emerged almost drained of blood; the centre had collapsed, the international links had been lost; what remained of the sections in the periphery were left in isolation: the PCI was only a pale reflection of the pole-organization it had been within the proletarian milieu.

The Effects of the Crisis on the other Groups of the Proletarian Milieu

If the break-up of the PCI (Programme) was the clearest proof the crisis in the milieu, this was very much broader and also affected the groups who to varying degrees had participated in the dynamic of the conferences.

The weakest groups, those who were the product of immediate circumstance, without a a real political tradition or identity, were to disappear with the end of the conferences:

Arbetarmakt in Sweden, L'Eveil Internationaliste in Franc, the Marxist Workers' group in the USA, etc ... Other groups, more solid in that they were better rooted in a political tradition, but which had displayed their weaknesses during the conferences, not only through their political positions but, like the FOR and the GCI, through, their sectarian iiresponsibility, were to undergo a growing political degeneration in the face of acceleration of history:

-- the NLI in Italy were to follow a path identical to that of Programme Communiste through the repeated abandonment of principles on the national and union questions, and through an increasingly open flirtation with bourgeois leftism;

-- as for the GCI, its confused positions on the question of class violence, inspired by Bordigism, were to lead it -- less paradoxically than at first sight -- towards anarchism;

-- the FOR with its crazy denial of the reality of the crisis was led to take up increasingly surrealistic positions where the radical phrase replaced any cohercnce.

The ICC itself was not immune from the effects of this crisis of the prolerarian milieu. The ICC's involvement in intervention led to rich and important debates within it, but at the same time, the lack of organizational experience which still weights heavily on the present generation of revolutionaries was to allow a dubious adventurist element, Chenier, to crystallise tensions through secret maneuvers, finally fomenting the theft of the organization's materials. The few elements who followed Chenier in this adventure published ‘Ouvrier Internationaliste' which didn't survive much past its first issue. At the same time the Communist Bulletin Group, which was formed in the same dubious dynamic by elements who had left the ICC's section in Britain, put itself outside the proletarian milieu through supporting the gangster behavior of an element like Chenier.

The Opportunist Formation of the IBRP

The formation in 1983 of the International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party[11], which regrouped the CWO and Battaglia in this context of a crisis in the proletarian milieu, seemed to be a positive reaction. However, while this regroupment clarified the political landscape on the organisatioanl level, it didn't do the same thing on the political level. This regroupment was situated in the dynamic of the failure of the conferences, and it took place between two groups most responsible for the failure. It was in direct continuity with the opportunism and the sectarian spirit these two organizations had exhibited at the third conference and after.

In order to make a real political contribution, it is indispensable that the dynamic towards regroupment takes place in politically clear way. But this certainly wasn't the case with the ‘regroupment' that resulted in the IBRP. The CWO had moved away from its original platform which had been very close to that of the ICC (which didn't prevent the CWO from refusing, in 1974, any regroupment with World Revolution, future section of the ICCin Britain, on the grounds that after 1921, after Krondstadt, there was no proletarian life left in the Bolshevik party and the CPs, a sectarian pretext soon forgotten afterwards) but the debates which led to this change remained a mystery to the whole political milieu. It wasn't until two years after the famous fourth conference that the discussions were published, but this didn't bring much clarification about the political evolution of the two groups. The platform of the IBRP contained the same confusions and ambiguities that BC had exhibited at the conferences on the union question, the national question, and possibility of revolutionary parliamentarism, and, obviously, the question of the party and of the historic course.

But above all the formation of the IBRP expressed a false conception of the regroupment of revolutionaries. The lBRP is a cartel of existing organisations, rather than a new organisation, produced by a regroupment in which the forces fuse around a clear common platform. In it, each adherent organisation keeps its own specificity. As well as the platform of the IBRP each group keeps its own platform without explaining the important differences that can exist. This enables one to measure the false homnogeneity of the IBRP, the opportunism that provided over its formation.

The formation of the IBRP was not therefore the harbinger of the end of the crisis of the milieu, whose ravages continued to make themselves felt, or of new dynamic towards clarification within revolutionary forces. It was the expression of a rearrangenent of the forces of the political milieu carried out in opportunist confusion and sectarian isolation.

*****

In 1983, with the crisis that was shaking it, the face of the proletarian milieu had been transforned. The Bordigist PCI had more or less disappeared and the ICC had become the most important organization in the communist milieu, its dominant political pole and, to the extent that history had made its judgnent, a pole of clarity in the debates, which animated the milieu. The ICC is a centralized organization on an international scale with sections in 10 countries and publishing in seven languages. However, if the ICC had become the main pole of regroupment, that doesn't mean it was alone in the world. Despite the confusions built into its origins, the IBRP, in comparison to the political delinquency of the other groups who formed the proletarian milieu, formed the other pole of reference and of relative political clarity within the communist movement and its debates.

As we can see the groups most able to resist the crisis of the proletarian milieu were those who participated most seriously in the international conferences; . this fact alone enables us to measure the positive contribution they made, and in retrospect to appreciate the scale of the political error in dislocating them - an error for which Battaglia and the CWO bear a heavy responsibility.

In mid-'83, after the short but deep phase of reflux in the struggle that followed the defeat in Poland, the first signs of a revival of struggles began to appear. We've seen how, at the end of the ‘70s and the beginning of the ‘80s, the question of intervention was a real test for the proletarian milieu - the essential question that history is again posing to revolutionaries. In the third part of this article we will see whether the organizations of the proletarian milieu were able, after 1983, to live up to their responsibilities.

JJ

[1] See our pamphlet La Gauche Communiste d'Italie

[2] See the articles in IR 11, 16, 17, 21, 25, 28, 36, 37, 38, 45 and following.

[3] See the article ‘International Meeting Called by the PCInt (Battaglia Comunista) May '77 in IR 10, and the bulletin of the first conferences.

[4] On the CWO, see IRs 12, 17, 39.

[5] On Battaglia Comunista see IRs 13, 33, 34, 36.

[6] On the PCI (Program) see IRs 14, 23, 32, 33.

[7] See the articles on the second conference in IR 16 and 17; on the historic course see IR 18.

[8] See the articles on the second conference in IR 22 and the bulletin (3 volumes) of the third conference.

[9] On the crisis of the revolutionary milieu, see IRs 28-32.

[10] On the debates on intervention see IRs 20-24.

[11] On the formation of the IBRP see IR 40 and 47.

History of the workers' movement:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Political currents and reference:

- Communist Left [3]

Editorial: Reagan-Gorbachev, Afghanistan

- 2370 reads

"Disarmament" and "peace" are lies

‘Reduction of armaments' and the march towards war

A daily propaganda has been made this year on the ‘reduction of armaments' and the ‘peace-talks' between USA and the USSR with the Reagan-Gorbachev meetings, the whole thing based on the ‘rights of man', and ‘perestroika'. ‘Disarmament' is once again in fashion, but in reality, as always ‘the reduction of armaments' is an enormous lie. It's a facade of propaganda which covers the forced march of capitalism towards a permanent search to perfect its military equipment. The part consecrated to armaments in the national budgets of all countries has never been so high, and it is not in any way going to diminish. As we have developed in preceding numbers of this Review[1], capitalism in its period of decline since the first world war survives in a permanent war economy and "even in a period of ‘peace' the system is ravaged by the cancer of militarism". The increase in armaments is more and more inordinate, and its only possible denouement is in generalized war that could only mean, given the military technology of our epoch, the destruction of the planet and humanity.

The modernization of weapons

Today's propaganda should fool no-one. The withdrawal of certain missiles in Europe has the advantage for the USA that it makes its allies take more direct charge of military expenses; what's more, the withdrawal is completely negligible in relation to the overall firepower of the western bloc. For the USSR, it allows for the suppression of materiel outmatched by the sophistication of the present western armaments. The ‘START' accords for the ‘limitation' of armaments, like all these types of conferences between the representatives of the great powers, are really about the renewal of materiel and don't constitute a real reduction of the latter. Like the SALT 2 accords of the summer of ‘79, which led to the installation of the famous medium range missiles, justified at the time by the ‘disarmaments' of inter-continental warheads which had become obsolete, the present accords, presented as a ‘reduction of armaments', are in reality about dumping outdated material, and taking steps towards the development of new military systems.

It is true that for each national state armament expenses only aggravate the crisis and don't in any way permit it to be resolved. But it's not economic reasons which explain the campaign on the ‘reduction of armaments'. Capitalism isn't able to reduce armaments. When the USA, which wants to lessen its gigantic budget deficit, envisages the lessening of military expenses, it is not to reduce them globally in the western bloc, but to increase the part paid by its European and Japanese allies to ‘defend the free world'. It's the same for the USSR, which is being more and more strangled by the economic crisis, when it's forced to ‘rationalize' its military expenses. The increase in armaments is inherent in imperialism in the period of decadence, in the imperialism of all nations, from the smallest to the lamest and "from which no state can hold aloof" as Rosa Luxemburg said some time ago.

If today the talks speak of ‘the end of the cold war' and similar formulae, that must be understood not in the sense ‘peace' will now be on the agenda, but rather as a warning that capitalism is more and more being pushed towards a ‘hot war'. Furthermore, despite the attempts to justify war preparations the language of pacifism, the Reagan administration, which like the rest of the right wing of the political apparatus of the bourgeoisie is more at ease with open warmongering, hasn't muzzled the declarations of the actor/gangster of the White House about ‘being vigilant', ‘remaining strong'. In particular it has saluted Thatcher because without sacrificing her ‘anti-communist' credentials, she was also the first to suggest discussing ‘business' with Gorbachev; the ‘business' in question being nothing other than the diplomatic side of military pressure.

Intensification of East-West conflict

The pacifist talks today are part of the same reality as the war mongering at the beginning of the 1980s, when Reagan was denouncing the ‘Evil Empire' - the USSR. Today, when American diplomacy meets Russian diplomacy in Moscow, the discussion is on the ‘rules' of the growing confrontation on a world scale under the leadership of Moscow and Washington. In no way was it about putting an end to this confrontation.

Only the speeches have changed. The reality is always that of world capitalism's march to war, today characterized by a western offensive against the strategic positions of the USSR, and by the search for the means to resist and respond to this offensive on the part of the Russian imperialist bloc.

A great discretion reins today about the incessant battles in the Middle East and above all about the massive presence of the fleet of the great powers in the region. It seems clear that the media has orders to make the least noise possible about what takes place in the Persian Gulf - about the highly sophisticated armada, which has been on a war footing since the summer of ‘87. In the past 20 years, the direct military presence of countries like the United States, France, Britain, Belgium, and even the so-called ‘unarmed' West Germany, has never been as strong outside of their frontiers, on what the strategists call the ‘theatre of operations'. Are we really to think that all this armada is there only to ‘ensure the peaceful circulation of shipping'? Obviously not. This presence is part of the western military strategy and the latter is not dictated by a few second-rate Iranian gunships and the tugboats which refuel them, but by the historic rivalry between East and West.

The western offensive is aimed at the USSR and it has just scored another point with the retreat of Soviet troops from Afghanistan.

The USSR has been obliged to yield under the direct military pressure of the Afghan ‘resistance' equipped with American Stinger missiles, which have allowed the latter to considerably reinforce its firepower; and under the ‘indirect' pressure of the western fleet in the Gulf. It is now being obliged to abandon in part the occupation of the sole countries outside of its east European ‘sphere of influence'. And, unlike the USA which won the alliance with China at the time of their retreat from Vietnam in 1975, the USSR cannot count on any such deal. The USA has ceded nothing; this is also the real content of the Reagan-Gorbachev meetings. The western bloc is determined to maintain its pressure. This is also confirmed by the projected retreat of the Vietnamese army from Cambodia.

But the USSR's retreat doesn't mean the return to peace, on the contrary. Just as the Israeli-Arab accord at Camp David between Egypt and Israel more than 10 years ago, under the benediction of Carter and Brezhnev, resulted in an enlargement of conflicts, in the massacres of populations and the social decomposition of the situation in the Middle East, the present retreat of Russian troops doesn't open up a perspective of ‘peace' and ‘stability' but rather of a reinforcement of tensions, and in particular a probable ‘Lebanonisation' of Afghanistan, which is a tendency common to all countries in this region.

The ‘perestroika' of Gorbachev, just as it is a ‘democratic' veneer for home consumption, a cover for pushing through redoubled anti-working class measures, is also in foreign policy a pacifist veneer over a more and more unpopular military occupation - a policy which will in fact be continued and reinforced, even if it is under the more ‘discrete' form of political and military support to factions, clans and cliques of national bourgeoisies which don't find their place in the camp of the ‘Pax Americana', notably the local Communist Parties and their leftist appendages.

The conflict between the great powers will be pursued by permanently playing on the different governmental or opposition factions in all the extremely bloody ‘local' conflicts, with a growing military participation by the principal antagonists, to the point where they are directly face to face - if the bourgeoisie has its hands free to keep social peace and guarantee loyalty to its imperialist designs. But this is far from being the case today.

Pacifism: a lie directed against the working class

It is fundamentally because the bourgeoisie is at grips with a proletariat which doesn't bend docilely to the attacks of austerity, a proletariat which doesn't show any profound adhesion to the diplomatic/military maneuvers which lead to an acceleration of inter-imperialist tensions, that today's propaganda on the one hand keeps silent about workers' strikes and demonstrations, and on the other hand has been converted from yesterday's warlike language into a ‘pacifist', ‘disarmament' campaign.

At the beginning of the 1980s the proletariat was suffering from the reflux of several important struggles which had developed internationally, from 1978 to the defeat of the workers in Poland in 1981. The propaganda of the bourgeoisie could at the beginning of the ‘80s be based on the feelings of disorientation that had been engendered by such a situation. It tried to instill feelings of fatality, impotence, demoralization and intimidation, in particular through a barrage of war propaganda and war-like actions: Falklands war, invasion of Grenada by the US, Reagan's diatribes against the Evil Empire, Star Wars, etc, the whole thing being accompanied by military actions that more and more involved the great powers on the field of operations, up to the installation of western troops in the Lebanon in 1983.

Since 1983-84 workers' strikes and demonstrations have multiplied against the different austerity plans in the industrialized countries and equally in the less developed countries, marking the end of the short preceding period of reflux and passivity. And if many proletarian political groups are unfortunately incapable of seeing, behind the daily images peddled by the propaganda of the bourgeoisie and of its media, the reality of the present development of the class struggle[2], the bourgeoisie itself senses the danger. Through the different political and union forces at its disposal it is evident that the bourgeoisie knows that the essential problem is the ‘social situation', everywhere, and particularly in Western Europe where all the stakes of the world situation are concentrated. And there are more and more ‘enlightened' bourgeois sounding the alarm about the danger of de-unionization in the working class and the risk of ‘unforeseen' and ‘uncontrolled' movements. It's as a result of this danger that the bourgeoisie puts forward the false alternative of ‘war or peace', the idea that the future depends on the ‘wisdom' of the leaders of this world, when it really depends on the international working class taking control of and unifying its struggles for emancipation. Because of this danger everything is done to hide and minimize the mobilizations of the workers and the unemployed, to spread ideas about the weakness, impotence or ‘dislocation' of the working class.

If the bourgeoisie is a class divided into nations regrouped around imperialist blocs, ready to sharpen their rivalries, up to using all the means it has in a generalized imperialist war, it is by contrast a unified class when it's a question of attacking the working class, imprisoning its struggles, of maintaining it as an exploited class submitting to the dictates of each national capital. It's only faced with the working class that the bourgeoisie finds a unity, and the present unanimous choir about ‘peace' and ‘disarmament' is only a masquerade aimed essentially at anaesthetizing the growing proletarian menace.

Because, despite their limits and numerous setbacks, the struggles which have developed for several years in all countries, touching all sectors, from Spain to Britain, from France to Italy, including a country like West Germany which until now has been the least touched by the devastating effects of the crisis[3], are not only the sign that the working class is not ready to accept passively the attacks on the economic terrain, but also that preceding attempts at intimidation through the 'warlike' campaigns, or the noise about the 'economic recovery' have not had the desired effect. Equally symptomatic of the maturation of the consciousness in the working class is the fact that, as in Italy and Spain last year, we've seen during the electoral campaign in France - traditionally a time of social truce - the eruption of a number of particularly combative strikes. It's this development of the class struggle which lies behind the bourgeoisie's ‘peace' campaigns both in the eastern bloc and the countries of the west.

MG 7 June 1988

[1] See IR 52 and 53

[2] See the polemic in this issue on the underestimation of struggles by today's communist groups.

[3] See the editorial in IR 53.

Recent and ongoing:

- Afghanistan [4]

- Reagan [5]

- Gorbachev [6]

Part 4: Understanding the Decadence of Capitalism

- 4270 reads

Understanding the Decadence of Capitalism, Part 4

We are continuing here the series of articles begun in International Review Nos. 48 [7], 49 [8], 50 [9], which aimed to defend the analysis of the decadence of capitalism against the criticisms levelled at it by groups of the revolutionary milieu, and by the GCI [1] in particular.

In this article, we aim to develop different aspects of the decadence of the capitalist mode of production, and to answer the arguments that reject it.

In the late 60s-early 70s, the ICC had to fight to convince the political milieu that the “Golden Sixties” had come to an end, and that capitalism had entered a new period of crisis. The tremors that shook the international monetary system in October ‘87, and the effective stagnation of the real economy over the last 10 years (see graph below) leave no room for doubt, and have clearly demonstrated the inanity of a position like the FOR’s [2], which still denies the reality of the economic crisis. But there is worse: with the world on the threshold of the choice between War and Revolution, there are still to be found revolutionary groups which, while recognising the crisis, nonetheless proclaim capitalism’s vitality.

On the economic level, today’s crisis can only end in war, unless the proletariat stops the mailed fist of the bourgeoisie. However, since the end of the 60’s the working class has struggled more and more openly against the constant degradation in its living conditions, thus preventing capitalism from giving free rein to its inherent tendency towards generalised war. On the one hand, the proletariat has not been beaten physically as it was after the defeat of the international revolutionary wave during the 1920’s, or after the massacres of World War II, nor on the other does it adhere to bourgeois ideology as it did before the First and Second World Wars (anti-fascism and nationalism). With humanity’s future hanging in the balance (between either the development of the present course towards class confrontations, or the defeat of the working class and the opening of a course towards war), when revolutionaries have the task of demonstrating the capitalist mode of production’s historical bankruptcy and socialism’s necessity and immediacy, there are political groups picking over the “fantastic growth rates of the reconstruction period”, abandoning the marxist conception of succeeding modes of production by rejecting the notion of decadence, and straining themselves to prove that “...capitalism grows endlessly, beyond all limits”. It is hardly surprising that with this kind of foundation, and without any coherent analysis of the period, these groups defend a perspective that is unfavourable for the working class, and essentially academic as far as the activity of revolutionary minorities is concerned.

According to the EFICC [3], today’s priority is theoretical reflection and discussion (see Internationalist Perspective no. 9). Much preoccupied by the urgent problem of “the length and extent of the reconstruction that followed World War II”, they propose that the milieu should discuss the “serious problems” that it poses (IP nos. 5, 7). For CoC [4], we are still living in the period of counter-revolution that has lasted since the 1920’s (no. 22): “with the end of World War II, the capitalist mode of production entered as almost unprecedented period of accumulation”, and “...in the absence of a quantitative and qualitative break...” in the class struggle, this group proposes to produce, in ...six-monthly... episodes a grand encyclopaedic fresco on the theory of crises and the history of the workers’ movement. For the GCI, since the 1968-74 wave of struggles, “the peace of the Versailles reigns” (editorial, no. 25/26). This group’s essential preoccupation is the liquidation of the gains of socialism; in its publication (Le Communiste no. 23), it identifies the marxist conception of the decadence of a mode of production with religious world-views like those of the Moon sect or the Jehovah’s Witnesses etc... The new split from the GCI, “A Contre Courant” [5] remains on the same terrain, both on the historical level – “We reject both the sclerotic schemes of the vulgar decadentist variety (plastered over a reality which is constantly disproving them)...” – and on the level of today’s balance of forces between the classes: “for us, the present stock-market crisis materialises essentially the proletariat’s absence as a revolutionary force...” (ACC no. 1).

THE DECADENCE OF CAPITALISM

To hide its movement towards anarchism and its abandon of all reference to a marxist framework of social analysis, the GCI takes cover behind the authority of an incorrect conception culled from the “thoroughly marxist” Bordiga [6]: “The marxist conception of the fall of capitalism does not at all consist in affirming that after a historic phase of accumulation it becomes anaemic and empties itself of life. These are pacifist revisionist theses. For Marx, capitalism grows endlessly, and without limits” (LC no. 23).

Whereas the decadence of previous modes of production was clearly identifiable (we will develop this point later), either because there was an absolute decline in the productive forces – Asiatic and antique modes of production – or because they stagnated with occasional fluctuations – feudal mode of production – the same is not true of capitalism. Capitalism is a wholly dynamic mode of production; the bases of its enlarged reproduction leave it no respite; its law is grow, or die. However, like previous modes of production, capitalism also has its period of decadence which began in this century’s second decade, and which is characterised by the brake imposed on the development of the productive forces by its now outdated fundamental social law of production – wage labour – which is eventually expressed in a lack of solvent markets relative to the needs of accumulation.

This is violently contradicted by our censors. However, peremptory affirmations aside, what are their arguments?

1) On a general theoretical level, we are told that Luxemburg’s analysis of the crisis, on which we base ourselves, is incapable of grounding a coherent explanation of the “so-called” decadence of capitalism: “If we follow Luxemburg’s logic, on which the ICC’s reasoning and the theory of decadence is based, then we are led to conclude that decadence must mean the immediate collapse of capitalist production, since none of the surplus value destined for accumulation can be realised, and so accumulated” (CoC no. 22).

2) On a general quantitative level, the period of capitalist decadence is said to have undergone much more rapid growth than the period of ascendancy: “For the capitalist world as a whole, growth during the last 20 years [1952-72, ed.] has been at least twice as rapid as it was between 1870 and 1914, that is to say during the period that is generally considered to be that of ascendant capitalism. The affirmation that the capitalist system has been in decline since World War I has quite simply become ridiculous...” (P. Souyri quoted in LC no. 23). “More than 70 years after the watershed date of 1914, the capitalist mode of production is still accumulating surplus value, while the rate and the mass of this surplus value have grown faster than during the 19th century, which was supposedly the capitalist mode of production’s ascendant phase...”

3) On a circumstantial level, in chorus with all the refuters of marxism, the growth rates that followed World War II (the highest in the whole history of capitalism) are brandished as the decisive proofs of the inanity of the idea that the capitalist mode of production could be decadent: “For, with the end of World War II, the capitalist mode of production entered a period of accumulation almost without precedent since the passage to the phase of labour’s real submission to capital” (CoC no. 22). “The frantic accumulation which followed World War II has swept away all Luxemburg-based sophisms...”

1 – ON THE THEORETICAL LEVEL

We will not here go back over a subject that has already been dealt with at length in our press (International Review no. 13, 16, 19, 21, 22, 29, 30). We will limit ourselves to pointing out the thoroughly dishonest practice of our contradictors, who deform our positions knowingly, in order to make an absurdity appear where none exists. The procedure consists of pretending that for the ICC, decadence = total inexistence of extra-capitalist markets: “If, as the ICC claims, the extra-capitalist markets have disappeared – at least qualitatively – then we cannot see what the better exploitation of old markets means. Either these are capitalist markets and their role is zero as far as accumulation is concerned, or they are extra-capitalist markets, in which case we cannot see how something which no longer exists can play any role at all”.

On this kind of basis it is not difficult for CoC to demonstrate the impossibility of any enlarged accumulation since 1914. But, for us as for Rosa Luxemburg, the decadence of capitalism is characterised not by the disappearance of extra-capitalist markets, but the inadequacy of extra-capitalist markets in relation to capital’s need for enlarged accumulation. That is to say, that the mass of surplus value realised in extra-capitalist markets is too small for it to be possible to realise the total mass of surplus value that capitalism produces. A fraction of total capital can no longer be sold on the world market, and this over production, from being an episodic obstacle in ascendant capitalism, becomes a permanent one in decadence. Enlarged accumulation has therefore been slowed down, but this does not mean that it has disappeared. Capitalism’s economic history since 1914 is the history of the palliatives aimed at cutting this Gordian knot, and their ineffectiveness – demonstrated, amongst other things, by the two World Wars (see below).

2 - ON THE GENERAL QUANTITATIVE LEVEL

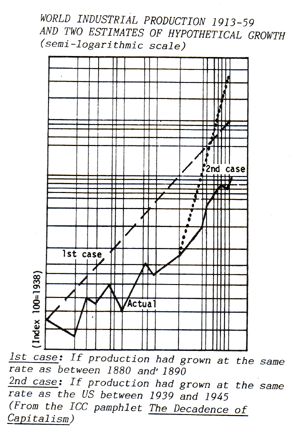

To illustrate concretely how capitalist social relations of production hold back the productive forces (i.e., the decadence of capitalism), we have calculated what industrial production would have been without the braking effect, since 1913, of the social relations of production. We then compare this hypothetical index of industrial production (2401) to the real index (1440) over the same period (1913-83).

To do so, we have applied the rate of growth during the last phase of capitalist ascendancy (Kondratieff’s “phase A” (1895-1913) [7]) to the whole phase of decadence (1913-1983): we then compare real growth in 1983 (=1440) to potential growth (=2401 – application of a 4.65% growth rate to the same period), ie what it would have been without the obstacle of the inadequacy of the market. We can see that industrial production in decadence reaches 60% of what it could have been, in short that the braking power of capitalist social relations on the forces of production is in the order of 40%. Again, this is underestimated for three reasons:

a) We should extrapolate the rate of 4.65%, not linearly but exponentially, which is the tendency during the various prosperous phases of ascendant capitalism (Kondratieff’s “phase A”), given capital’s increasing technical perfection (1786-1820: 2.4%; 1840-70: 3.28%; 1894-1913: 4.65%).

b) Real growth in decadent capitalism, to the extent that it is doped by a whole series of tricks (a point which we will expand on in a forthcoming article), which must be discounted. For example, arms production – the non-productive sector – grows strongly in decadence as a proportion of the World Domestic Product, from 1.77% in 1908 to 2.5% in 1913, and to 8.3% in 1981 [8]. It therefore grows still more strongly as a part of the World Industrial Product index, since the latter’s share of the WDP decreases during decadence.

c) Since the present crisis has continued, the stagnation of growth rates since 1983 would only increase the difference.

If we add up all these elements, we easily reach a braking effect on the productive forces of about 50%.

Why do we choose the growth rates for the period 1895-1913, and not those for the whole of the ascendant period?

a) Because we have to compare what is comparable. In its early days, capitalism was held back by other braking effects: the survival of relations of production inherited from feudalism. Production was not yet wholly capitalist (widespread survival of cottage industry, etc.), whereas this was the case by 1895-1913.

b) Because the period 1895-1913 follows the main phase of imperialist expansion (colonial conquests), which took place during the previous phase (1873-95) [9]. This is therefore a period which the best reflects capitalism’s productive potential when it has an “unlimited” market at its disposal. This wholly suits our objective, which is to compare capitalism with and without a braking effect.

c) Because we therefore negate the exponential tendency of growth rates to increase over time.

These elements put definitively in their place all the myths of “a capitalism growing twice as fast in decadence as in ascendancy”. Souyri’s “demonstration” which the GCI relies on is nothing more than a gross mystification, since it compares two incomparable periods:

a) For the GCI and for Souyri, the period 1952-72 is supposed to represent decadence, when in fact it excludes the two world wars (14-18 and 39-45) and the two crises (29-39 and 71-..)!

b) It compares a homogeneous period of 22 years of doped growth, with a heterogeneous phase of 44 years of normal capitalist life (this last includes a phase of relative slowdown in 1870-94 (3.27%) leading on to massive colonialism, which then opens up a phase of strong growth in 1894-1913 (4.65%).

c) It compares two periods where growth’s foundations are qualitatively different (see below).

Decadence is far from being a “vulgar sclerotic schema plastered over a reality that disproves it constantly”. On the contrary, it is an objective reality that has been confirmed with every passing day since the beginning of the century.

3 – ON THE QUALITATIVE LEVEL

The decadence of a mode of production cannot be measured simply in the light of statistics. The phenomenon can only be grasped through a whole series of quantitative, but also qualitative and superstructural aspects: our critics pretend not to know this, so as to avoid having to say anything about it, being happy enough to brandish the figures whose value we have just demonstrated.

a) The cycle of life in ascendancy and decadence

In ascendant capitalism’s overall dynamic, growth is a continuous progression, with slight fluctuations. It follows a rhythm of cycles of crisis – prosperity – lesser crisis – increased prosperity – etc. In decadence, apart from the overall braking effect that we have been above, growth undergoes intense and previously unheard-of fluctuations: two world wars, a marked slowdown during the last 15 years, and even stagnation during the last ten. World trade has never undergone such violent contractions (stagnation between 1913 and 1940, a marked slowdown in recent years), illustrating the permanent problem, in decadence, of inadequate markets.

TABLE 1

|

1ST SPIRAL |

|

|

|

CRISIS |

WAR |

DRUGGED RECONSTRUCTION |

|

1913: 1.5 Years of crisis |

1914-18: 4 years and 20 million deaths |

1918-29: 10 years |

|

2ND SPIRAL |

|

|

|

CRISIS |

WAR |

DRUGGED RECONSTRUCTION |

|

1929-39: 10 Years of crisis |

1939-45: 6 years, 50 million deaths and massive destruction |

1945-67: 22 years |

|

3RD SPIRAL |

|

|

|

CRISIS |

WAR |

SOCIALISM OR BARBARISM |

|

1967 - … already 20 years of crisis |

A war that would be irreparable for humanity, or revolution |

|

Table no. 1 illustrates the cyclical rhythm of capitalism in decadence: a rising spiral of crisis – war – reconstruction – ten-fold crisis – ten-fold war – doped reconstruction... But decadence has a history, and does not eternally repeat the same cycle. We are living at the beginning of the 3rd spiral, and what is at stake today is Engels’ old battle-cry: “Socialism or barbarism”. “The triumph of imperialism leads to the destruction of civilisation, sporadically during a modern war and forever, if the period of world wars that has just begun [1914, ed.] is allowed to take its damnable course to its ultimate conclusion. Thus we stand today, as Friedrich Engels prophesied more than a generation ago.... [before] the dilemma of world history, its inevitable choice, whose scales are trembling in the balance awaiting the decision of the proletariat. Upon it depends the future of civilisation and humanity.” (Rosa Luxemburg, The Crisis of Social Democracy ( [10]The Junius Pamphlet [10]) [10])

b) War in capitalist ascendancy and decadence

“IV – WHAT IS HISTORICALLY AT STAKE IN DECADENT CAPITALISM. Since the opening of capitalism’s imperialist phase at the beginning of this century, evolution has oscillated between imperialist war and proletarian revolution. In the epoch of capitalist growth, wars cleared the way for the expansion of the productive forces by the destruction of outmoded relations of production. In the phase of capitalist decadence, wars have no other function than the destruction of excess wealth...” (“Resolution on the Constitution of the International Bureau of the Fractions of the Communist Left”, in OCTOBRE NO. 1, Feb. 1938).

During ascendancy, wars appeared essentially in phases of capitalist expansion (Kondratieff’s “A phase”), as products of the dynamic of an expanding system :

|

1790-1815 |

revolutionary and empire-building wars (Napoleonic). |

|

1850-1873 |

Crimean and Mexican Wars, American Civil War, wars of national unification (Germany and Italy), Franco-Prussian War (1870). |

|

1895-1913 |

Hispano-US, Russo-Japanese, Balkan wars. |

Generally speaking, the function of war in the 19th century was to ensure the unity of each capitalist nation (wars of national unification) and/or the territorial extension (colonial wars) necessary for its development. In this sense, and despite its attending disasters, war was a moment of capital’s progressive nature: as long as it allowed capital to develop, then it was the necessary cost of enlarging the market, and therefore production. This is why Marx spoke of some wars being progressive. Wars were then, a) limited to 2 or 3 adjacent countries, b) of short duration, c) did little damage, d) were conducted by specialised armies and required little mobilisation of the population, and e) were declared with a rational goal of economic gain. They determined, for both victors and vanquished, a new expansion. The Franco-Prussian war is a typical example: it was a decisive step in the formation of the German nation, in other words in laying the foundations for a fantastic development of the productive forces and the constitution of the most important sector of Western Europe’s industrial proletariat; at the same time, the war lasted less than a year, casualties were relatively low, and it did not greatly handicap the defeated country.

In decadence, by contrast, wars appear as a result of crises (see Table 1), as a product of the dynamic of a shrinking system. In a period where there is no longer any question of forming new national units, or of any real independence, all wars take on an inter-imperialist character. Wars are a) generalised worldwide because their roots lie in the permanent contraction of the world market relative to the demands of accumulation, b) they are of long duration, c) they cause massive destruction, d) they mobilise the whole world economy and the entire population of the belligerent countries, e) they lose all economic function, and become completely irrational. They are no longer an aspect of the development of the productive forces, but of their destruction. They are no longer moments in the expansion of the capitalist mode of production, but moments of convulsion in a decadent system. Whereas in the past, a clear winner emerged, and the war’s outcome did not jeopardise the development of either protagonist, in the two World Wars both victors and vanquished emerged weakened, to the benefit of a third scoundrel: the United States. The victors were unable to extract the cost of the war from the vanquished (contrary to the heavy ransom in gold paid to Germany by France at the end of the Franco-Prussian war). This illustrates the fact that in decadence, the development of one is built on the ruin of others. Previously, military power upheld and guaranteed economic positions won or to be won; today, the economy is increasingly an auxiliary of military strategy.

ACC and CoC refuse to recognise this qualitative difference between wars pre- and post-1914: “At this level, we want to relativise even the affirmation of World War (...) All capitalist wars have therefore an essentially international content (...) What changes is therefore not the invariant worldwide content (whether the decadentists like it or not), but its extent and depth, each time more truly worldwide and catastrophic” (ACC no. 1). With a touch of irony, CoC tries to oppose us to Rosa Luxemburg, for whom “...militarism is not characteristic of a particular phase of the capitalist mode of production” (CoC no. 22). This groups forgets that, while it is indeed true that for Luxemburg “...war accompanies all the historic phases of accumulation”, it is also true that for her, the function of both war and militarism change with the capitalist system’s entry into decadence: “Capitalist desire for imperialist expansion, as the expression of its highest maturity in the last period of its life, has the economic tendency to change the whole world into capitalistically producing nations (...) World war is a turning point in the history of capitalism (...) Today war no longer functions as a dynamic method capable of winning for new-born capitalism the conditions of its national expansion (...) this war creates a phenomenon unknown in previous modern wars: the economic ruin of all the countries taking part in it” (Rosa Luxemburg, Ibid).

If the image of decadence is of a body growing in clothes that have become too tight for it, then war marks this body’s need to cannibalise itself, to devour its own substance to stop the clothes splitting; this is the meaning of such massive destruction of the productive forces. Life as part of rival blocs, war, have become permanent aspects of capitalism, its very life even.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF STATE CAPITALISM

The state’s development in every domain, its increasing grip on the whole of social life, is an unequivocal characteristic of periods of decadence. All previous modes of production, whether Asiatic, antique, or feudal, underwent such a hypertrophy of the state apparatus (we will come back to this later). The same is true of capitalism. A mode of production which:

-- on the economic level has become a hindrance to the development of the productive forces, expressed in increasingly serious crisis and malfunctions;

-- on the social level, is contested by the new revolutionary class bearing the new social relations of production and by the exploited class through an increasingly bitter class struggle;

-- on the political level is constantly torn by the internal antagonisms of the ruling class leading to increasingly murderous and destructive internecine wars:

-- on the ideological level undergoes the increasing decomposition of its own values; reacts by armour-plating its own structures by means of one appropriate instrument: the state.

In decadence, state capitalism:

-- replaces private initiative, which has more and more difficulty in surviving in a super-saturated market;

-- controls a developed proletariat which has become a permanent threat to the bourgeoisie, through the old working class organisations (“Socialist” and “Communist” Parties, trades unions) as well as a whole series of social mechanisms aimed at tying the working class to the state (social security, etc);

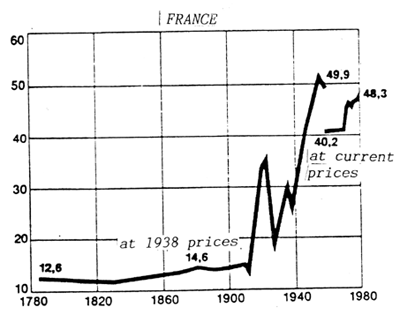

-- disciplines the particular fractions of capital in the general interests of the system as a whole. We can, in part, measure this process in the state’s share of GNP. We show below graphs that illustrate this indicator for three countries.

The change that takes place in 1914 is quite clear. The state’s share in the economy remains constant throughout capitalism’s long ascendant period; it then grows during decadence, to each an average of around 50% of GNP (47% in 1982 for the 22 most industrialised countries in the OECD).

The EFICC does not yet openly criticise the theory of capitalist decadence, but is abandoning it little by little, insidiously, in one “contribution to discussion” after another, that are so many milestones in its regression. Its “contribution” on state capitalism in Internationalist Perspective no. 7 is a flagrant illustration.