1983 - 32 to 35

- 4865 reads

International Review no. 32 - 1st Quarter 1983

- 2728 reads

The task of the hour: formation of the party or formation of cadres

- 2866 reads

(From Internationalisme - August 1946)

This article first appeared in Internationalisme no 12 in August 1946. Although it is a product of the immediate post-Second World War period, it is still remarkably relevant today, 36 years later. It deals with the question of when the formation of the party is both necessary and possible.

For those who refuse to recognize the need for a political party of the proletariat, the problem of the role of such a party, its function and the moment for its formation is obviously of no interest.

But for those who have understood and accepted the idea of the party as an expression of the working class in its struggle against capitalism, the question is crucial. For those militants who understand the need for the party, putting the issue of when to form it in a historical perspective is of the utmost importance because the question of when you form a party is linked to your whole conception of what the party should do. Is the party a pure product of the ‘willpower' of a group of militants or is it the result of the evolution of the working class in struggle?

If it is a mere product of will, the party can exist or be formed at any time at all. If, on the other hand, it is an expression of the class in struggle, its formation and continued existence are linked to periods of upsurge and decline in the proletarian struggle. In the former case, we are talking about a voluntaristic, idealist vision of history; in the latter, a materialist conception of history and its concrete reality.

Make no mistake about it -- this is not a question of abstract speculation. It is not a scholastic discussion on the proper words or labels to use: either ‘party' or ‘fraction' (‘group'). The two conceptions lead to diametrically opposite approaches. An incorrect approach based on not understanding the historical moment for the proclamation of the party necessarily leads a revolutionary organization to try to be what it cannot yet be and to miss being what it can be. Such an organization, looking for an immediate audience at any price, transforming principles into dogmas instead of maintaining clear political positions based on a critical examination of history, will not only find itself blurring reality in the present but compromising its future by neglecting its real tasks in the long term. This approach leaves the way open for all sorts of political compromise and opportunism.

This is the very paint Internationalisme criticized in the Bordigist party in 1946, and 36 years of the ICP's activity amply confirms the validity of these criticisms.

However, some formulations of Internationalisme lend themselves to possible misinterpretation. For example, the phrase: "the party is the political organism the proletariat creates to unify its struggles" (p2). Put this way, the statement implies that the party is the only motor force towards this unification of struggles. This is not true and it is not the position Internationalisme defended, as any reader of its press can verify. The formulation should be taken to mean that one of the main tasks of the party is to be a factor, an active factor, in the unification of the class struggle by orienting it "towards a frontal attack on the state and capitalist society, towards the building of a communist society." (ibid)

Regarding the question of the Third World War, the war did not happen in the way Internationalisme predicted. There was no generalized war, but a series of local, peripheral wars called ‘national liberation' struggles or ‘anti-colonial' struggles; in reality they were subservient to the needs and interests of the major powers in their struggle for world hegemony.

It is nonetheless true, as Internationalisme predicted, that the Second World War Zed to a long period of reaction and profound decline in class struggle, which lasted until the end of the period of reconstruction.

Some readers may be shocked by the use of the term "formation of cadres" which Internationalisme announced as the "task of the hour" in that period. Today the word "cadres" is only used by leftists preparing future bureaucrats for capital against the proletariat. But in the past, and as used by Internationalisme, the idea of forming cadres meant that the situation did not permit revolutionaries to have a large-scale influence in the working class and that therefore the work of theoretical development and formation of militants inevitably took precedence over any possibility of agitation.

Today we are living in a completely different period, a time of open crisis for capitalism, and of the renewal of class struggle. Such a period makes the regroupment of revolutionary forces both necessary and possible. This perspective can be carried out by the existing, scattered revolutionary groups only if they reject any rationalization of their own isolation, if they pave the way for a real debate on the political positions inherited from the past which are not necessarily valid today, if they consciously commit themselves to a process of international clarification leading to the possibility of a regroupment of forces. This is the real way towards the formation of the party.

When to form the Party

There are two conceptions of the formation of the party which have clashed ever since the first historical appearance of the proletariat, that is, its appearance as an independent class with a role to fulfill in history rather than its mere existence as an economic category.

These conceptions can be summarized as follows:

* The first conception holds that the formation of the party depends essentially, if not exclusively, on the desires of individuals, of militants, of their level of consciousness. In a word, this conception considers the formation of the party as a subjective, voluntaristic act.

* The second conception sees the formation of the party as a moment in the development of class consciousness directly linked to class struggle, to the relation of forces between the classes at a given moment due to the economic, political and social situation at the time; to the legacy of past struggles and the short and long-term perspectives of future struggles.

The first conception, basically subjective and voluntaristic, is more or less consciously tied to an idealist view of history. The party is not determined by class struggle; it becomes an independent factor determined only by itself and is elevated to being the very motor force of class struggle.

We can find ardent defenders of this conception right from the beginning of the workers' movement and throughout its history up to the present time. In the early days of the movement Weitling and Blanqui were the most well-known representatives of this tendency.

However great their errors and however much they deserved the severe criticism Marx meted out to them, we should consider them and their mistakes in a historic perspective. Their errors should not blind us to the great contribution they made to the workers' movement. Marx himself recognized their worth as revolutionaries, their devotion to the proletarian cause, their merit as pioneers inspiring the working class with their unflagging will to end capitalist society.

But what was an error for Weitling and Blanqui, a lack of understanding of the objective laws governing the development of class struggle became for their later followers the very focal point of their existence. Voluntarism turned into complete adventurism.

Undoubtedly the most typical representatives of this today are Trotskyism and everything linked to it. Their agitation has no limits other than their own whims and fantasies. ‘Parties' and ‘Internationals' are switched on and off at will. Campaigns are launched, slogans, agitation like a sick man in convulsions.

Closer to us we have the RKD[1] and the CR[2], who spent a long time in Trotskyism and left it very late in the day. They have unfortunately kept this taste for agitation for its own sake, agitation in a vacuum, and have made this the very basis of their existence as a group.

The second conception can be defined as determinist and objective. It not only considers that the party is historically determined but that its formation and existence are also determined by immediate, contingent circumstances.

It holds that the party is determined both by history and by the immediate, contingent situation. For the party to really exist, it is not enough to demonstrate its general historical necessity. A party must be based on immediate, current conditions which make its existence possible and necessary.

The party is the political organism that the proletariat creates to unify its struggles and to orient them towards a frontal attack on the state and capitalist society, towards the building of a communist society.

Without a real development of the perspective of class struggle rooted in the objective situation and not simply in the subjective desires of militants, without a high degree of class struggle and of social crisis, the party cannot exist -- its existence is simply inconceivable.[3]

The party cannot be created in a period of stagnation in the class struggle. In the entire history of the workers' movement there are no examples of effective revolutionary parties created in periods of stagnation. Any parties begun in these conditions never influenced or effectively led any mass movements. There are some formations that are parties in name only but their artificial nature only hinders the formation of a real party when the time comes. Such formations are condemned to be being sects in all senses of the word. They can escape from their sect life only by falling into quixotic adventurism or the crassest opportunism. Most of them end up with both together, like Trotskyism.

The possibility of maintaining the Party in a period of reflux

What we have said about the formation of the party is also true for the question of keeping it alive after decisive defeats of the proletariat in a prolonged period of revolutionary reflux.

People often use the example of the Bolshevik party to counter our argument but this is a purely formalistic view of history. The Bolshevik party after 1905 cannot be seen as a party; it was a fraction of the Russian Social-Democratic party, itself dislocated into several factions and tendencies.

This was the only way the Bolshevik fraction could survive to later serve as a central core for the formation of the communist party in 1917. This is the real meaning of the history of the Bolsheviks.

The dissolution of the First International shows us that Marx and Engels were also aware of the impossibility of maintaining an international revolutionary organization of the working class in a prolonged period of reflux. Naturally, small-minded formalists reduce the whole thing to a maneuver of Marx against Bakunin. It is not our intention to go into all the fine points of procedure or to justify the way Marx went about it.

It is perfectly true that Marx saw in the Bakuninists a danger for the International and that he launched a struggle to get them out. In fact, we think that fundamentally he was right in terms of content. Anarchism has many times since then proven itself a profoundly petty-bourgeois ideology. But it was not this danger than convinced Marx of the need to dissolve the International.

Marx went over his reasons many times during the dissolution of the International and afterwards. Seeing this historic event as the simple consequence of a maneuver, of a personal intrigue is not only a gratuitous insult to Marx; it attributes him with demonic powers. One has to be as small-minded as James Guillaume to ascribe events of historic dimensions to the mere will of individuals. Over and above all these legends of anarchism, the real significance of this dissolution must be recognized.

We can understand it better by putting these events in the context of other dissolutions of political organizations in the history of the workers movement.

For example, the profound change in the social and political situation in England in the middle of the 19th century led to the dislocation and disappearance of the Chartist movement.

Another example is the dissolution of the Communist League after the stormy years of the 1848-50 revolutions. As long as Marx believed that the revolutionary period had not yet ended, despite heavy defeats and losses, he continued to keep the Communist League going, to regroup forces, to strengthen the organization. But as soon as he was convinced that the revolutionary period had ended and that a long period of reaction had begun, he proclaimed the impossibility of maintaining the party. He declared himself in favor of an organizational retreat towards more modest, less spectacular and more really fruitful tasks considering the situation: theoretical elaboration and the formation of cadres.

It was not Bakunin or any urgent need for ‘maneuverings' that convinced Marx twenty years before the First International that it was impossible to maintain a revolutionary organization or an International in a period of reaction.

Twenty-five years later, Marx wrote about the situation in 1850-51 and the tendencies within the League in these terms:

"The violent repression of a revolution leaves its mark on the minds of the people involved, particularly those who have been forced into exile. It produces such a tumult in their minds that even the best become unhinged and in a way irresponsible for a greater or lesser period of time. They cannot manage to adapt themselves to the course history has taken and they do not want to understand that the form of the movement has changed ..." (Epilogue to the Revelations of the Trial of Communists in Cologne, 8 January 1875.)

In this passage we can see a fundamental aspect of Marx's thought speaking out against those who do not want to take into account that the form of the movement, the political organizations of the working class, the tasks of this organization, do not always stay the same. They follow the evolution of the objective situation. To answer those who think they see in this passage a simple a posteriori justification by Marx, it is interesting to look at Marx's arguments at the time of the League as he formulated them in the debate with the Willich-Schapper tendency. When he explained to the General Council of the League why he proposed a split in September 1850, Marx wrote, among other points:

"Instead of a critical conception, the minority has adopted a dogmatic one. It has substituted an idealist conception for a materialist one. Instead of seeing the real situation as the motor force of the revolution, it sees only mere will ...

... You tell ( the workers) : ‘We must take power right away or else we should all go home to bed.

Just like the democrats who have made a fetish of the word ‘people' you make a fetish of the word ‘proletariat'. Just like the democrats, you substitute revolutionary phrase-mongering for the process of revolution."

We dedicate these lines especially to the comrades of the RKD or the CR who have often reproached us with not wanting to ‘construct' the new party.

In our struggle since 1932 against Trotskyist adventurism on the question of the formation of the new party and the Fourth International, the RKD only saw who knows what kind of subjective ‘hesitations'. The RKD has never understood the concept of a ‘fraction', that is, a specific organization with specific tasks corresponding to a specific situation when a party cannot exist or be formed. Rather than making the effort to understand this idea, they prefer the simple dictionary-style translation of the word ‘fraction', in order to support their claim that ‘Bordigism' only wanted to ‘redress' the old CP . They apply to Left Communism the measure they learned in Trotskyism: ‘either you are for redressing the old party or else you have to create a new one'.

The objective situation and the tasks of revolutionaries corresponding to this situation, all that is much too prosaic, too complicated for those who prefer the easy way out through revolutionary phrase-mongering. The pathetic experience of organizing the CR was apparently not enough for these comrades. They see the failure of the CR simply as the result of a certain precipitousness while in fact the whole operation was artificial and heterogeneous from the start, grouping militants together around a vague and inconsistent program of action. They attribute their failure to the poor quality of the people involved, and refuse to see any connection with the objective situation.

The situation today

It might at first sight seem strange that groups who claim to belong to the International Communist Left, and who for years have fought alongside us against the Trotskyist adventurism of artificially creating new parties, are now riding the same hobbyhorse, and have become the champions of a still faster ‘construction'.

We know that in Italy, there already exists the Internationalist Communist Party which, although very weak numerically, is nonetheless trying to fulfill the role of the party. The recent elections to the Constituent Assembly, in which the Italian ICP participated, have revealed the extreme weakness of its real influence over the masses, which demonstrates that this party has hardly gone beyond the limitations of a fraction. The Belgian Fraction is calling for the formation of the new party. The French Fraction of the Communist Left (FFGC) , formed recently, and without any well-defined basic principles, is following in its footsteps, and has assigned itself the practical task of building the new party in France.

How are we to explain this fact, this new orientation? There can be no doubt that a certain number of individuals[4] who have recently joined this group are simply expressing their lack of understanding and their non-assimilation of the concept of the ‘fraction', and that they continue to express within the various groups of the ICL (International Communist Left) the Trotskyist conceptions of the party that they held yesterday and continue to hold today.

It is equally correct, moreover, to see the contradiction that exists between abstract theory and practical politics in the question of building the party as yet another addition to the mass of contradictions that have become a habit for all these groups. However, all this still doesn't explain the conversions of all these groups. This explanation must be sought in their analysis of today's situation and its perspectives.

We know the theory of the ‘war economy' set forward before and during the war by the Vercesi tendency in the ICL. According to this theory, the war economy and the war itself are periods of the greatest development of production, and of economic expansion. As a result, a ‘social crisis' could not appear during this period of ‘prosperity'. Only with the ‘economic crisis of the war economy', ie the moment when war production would no longer be able to supply the needs of war consumption, when the continuation of the war would be hindered by a scarcity of raw materials, would this new-style crisis open up a social crisis, and a revolutionary perspective.

According to this theory, it was logical to deny that the social convulsions which broke out during the war could come to anything. Hence also, the absolute and obstinate denial of any social significance in the events of July 1943 in Italy[5]. Hence also, the complete misunderstanding of the significance of the occupation of Europe by the allied and Russian armies, and in particular of the importance of the systematic destruction of Germany, the dispersal of the German proletariat taken prisoner of war, exiled, dislocated, and temporarily rendered inoffensive and incapable of any independent movement.

For these comrades, the renewal of the class struggle and, more precisely, the opening of a mounting revolutionary course, could only occur after the end of the war, not because the proletariat was steeped in patriotic nationalist ideology, but because the objective conditions for such a struggle could not exist during the war period. This mistake, already disproved historically (the Paris Commune and the October Revolution), and even partially in the last war (look at the social convulsions in Italy 1943, and certain signs of a defeatist spirit in the German army at the beginning of 1945) was to be fatally accompanied by a no less great error, which holds that the period following the war automatically opens a course towards the renewal of class struggles and social convulsions.

This error's most complete theoretical formulation is to be found in Lucain's article, published by the Belgian Fraction's L'Internationaliste. According to his schema, whose invention he tries to palm off on Lenin, the transformation of imperialist into civil war remains valid if we enlarge this position to include the post-war period. In other words, it is in the post-war period that the transformation of imperialist war into civil war is realized.

Once this theory has been postulated and systematized, everything becomes simple and we have only to examine the evolution of the situation and events through it and starting from it.

The present situation is thus analyzed as one of ‘transformation into civil war'. With this central analysis as a starting-point, the situation in Italy is declared to be particularly advanced, and thus justifying the immediate constitution of the party, while the disturbances in India, Indonesia and other colonies, whose reins are firmly held by the various competing imperialisms and by the local bourgeoisies, are seen as signs of the beginning of the anti-capitalist civil war. The imperialist massacre in Greece is also supposed to be part of the advancing revolution. Needless to say, not for a moment do they dream of putting in doubt the revolutionary nature of the strikes in Britain and America, or even in France. Recently, L'Internationaliste welcomed the formation of that little sect, the CNT, as an indication "amongst others" of the revolutionary evolution of the situation in France. The FFGC goes to the point of claiming that the three-party coalition government has been renewed due to the proletarian class threat, and insists on the extreme objective importance of the entry into their group of some five comrades from the group ‘Contre le Courant'[6]

This analysis of the situation, with the perspective of decisive class battles in the near future, naturally leads these groups to the idea of the urgent necessity of building the party as rapidly as possible. This becomes the immediate task, the task of the day, if not of the hour.

The fact that international capitalism seems not the least worried by this menace of proletarian struggle supposedly hanging over it, and goes calmly about its business, with its diplomatic intrigues, its internal rivalries and its peace conferences where it publicly displays its preparations for the next war -- none of this carries much weight in these groups' analysis.

The possibility of a new war is not completely excluded, first because it is useful as propaganda, and because they prefer to be more prudent than in the 1937-39 adventure where they denied the perspective of world war. It's best to keep a way out just in case! From time to time, following the Italian ICP, it will be said that the situation in Italy is reactionary, but this is never followed up and remains an isolated episode, without any relation to the fundamental analysis of the situation as one that is ripening ‘slowly but surely' towards decisive revolutionary explosions.

This analysis is shared by other groups like the CR, which counters the objective perspective of a third imperialist war with the perspective of an inevitable revolution; or like the RKD which, more cautiously, takes refuge in the theory of a double course, ie of a simultaneous and parallel development of a course towards revolution and a course towards imperialist war. The RKD has obviously not yet understood that the development of a course towards war is primarily conditioned by the weakening of the proletariat and of the danger of revolution, unless they have taken up the Vercesi tendancy's pre-1939 theory according to which the imperialist war is not a conflict of interests between different imperialisms, but an act of the greatest imperialist solidarity with the aim of massacring the proletariat, a direct capitalist class war against the proletarian revolutionary menace. The Trotskyists, with the same analysis, are infinitely more consistent , since they have no need to deny the tendency towards a third war; for them, the next war will simply be the generalized armed struggle between capitalism on the one hand, and the proletariat regrouped around the Russian ‘workers' state' on the other.

In the final analysis, either the next imperialist war is confused, one way or another, with the class war or its danger is minimized by making it the necessary precursor of a period of great social and revolutionary struggles. In the second case, the aggravation of inter-imperialist antagonisms and the war preparations going on today are explained by the short-sightedness and unawareness of world capitalism and its heads of state.

We may remain thoroughly skeptical about an analysis based on nothing more than wishful thinking, flattering itself with its clairvoyance, and generously assuming a complete blindness on the part of the enemy. On the contrary, world capitalism has shown itself far more acutely aware of the real situation than the proletariat. Its behavior in Italy in 1943 and in Germany in 1945 proves that it has assimilated the lessons of the revolutionary period of 1917 damned well -- far better than the proletariat or its vanguard. Capitalism has learned to defeat the proletariat, not only through violence, but by using the workers' discontent and leading it in a capitalist direction. It has been able to transform the one-time weapons of the proletariat into its chains. We have only to see that capitalism today willingly uses the trade unions, marxism, the October Revolution, socialism, communism, anarchism, the red flag and the 1st May as the most effective means of duping the proletariat. The 1939-45 war was fought in the name of the same ‘anti-fascism' that had already been tried out in the Spanish war. Tomorrow, the workers will once again be hurled into battle in the name of the October Revolution, or of the struggle against Russian fascism.

The right of peoples to self-determination, national liberation, reconstruction, ‘economic' demands, workers' participation in management and other such slogans, have become capitalism's most effective tools for the destruction of proletarian class consciousness. In every country, these are the slogans used to mobilize the workers. The strikes and disturbances that break out here and there remain in this framework, and their only result is to tie the workers still more strongly to the capitalist state.

In the colonies, the masses are being massacred in a struggle, not for the state's destruction but for its consolidation, its independence from the domination of one imperialism to the profit of another. There can be no possible doubt as to the meaning of the massacre in Greece, when we look at Russia's protective attitude, when we see Jouhaux becoming the advocate of the Greek CGT in its conflict with the government. In Italy, the workers' ‘struggle' against the monarchy in the name of the republic, or get massacred over the Trieste question. In France, we have the disgusting spectacle of workers marching in overalls in the 14th July military parade. This is the prosaic reality of today's situation.

It is untrue that the conditions for a renewal of class struggle are present in the post-war period. When capitalism ‘finishes' an imperialist world war which lasted six years without any revolutionary flare-ups, this means the defeat of the proletariat, and that we are living, not on the eve of great revolutionary struggles, but in the aftermath of a defeat. This defeat took place in 1945, with the physical destruction of the revolutionary centre that was the German proletariat, and it was all the more decisive in that the world proletariat remained unaware of the defeat it had just undergone.

The course is open towards the third imperialist war. It is time to stop playing the ostrich, seeking consolation in a refusal to see the danger. Under present conditions, we can see no force capable of stopping or modifying this course. The worst thing that the weak forces of today's revolutionary groups can do is to try to go up a down staircase. They will inevitably end up breaking their necks.

The Belgian Fraction think they can get away with saying that if war breaks out, this will prove that the formation of the party was premature. How naive! Such a mistake will be dearly paid for.

To throw oneself into the adventurism of artificial and premature party-building not only implies an incorrect analysis of the situation, but means turning away from the real work of revolutionaries today, neglecting the critical elaboration of the revolutionary program and giving up the positive work of forming its cadres.

But there is worse to come, and the first experiences of the party in Italy are there to confirm it. Wanting at all costs to play at being the party in a reactionary period, wanting at all costs to work among the masses means falling to the level of the masses, following in their footsteps; it means working in the trade unions, taking part in parliamentary elections -- in a word, opportunism.

At present, orienting activity towards building the party can only be an orientation towards opportunism.

We have no time for those who reproach us for abandoning the daily struggle of the workers, and for separating ourselves from the class. Being with the class is not a matter of being there physically, still less of keeping, at all costs, a link with the masses which in a reactionary period can only be done at the price of opportunistic politics. We have no time for those who, having accused us of activism from 1943-45, now reproach us for wanting to isolate ourselves in an ivory tower, for tending to become a doctrinaire sect that has given up all activity.

Sectarianism is not the intransigent defense of principles, nor the will to critical study; nor even the temporary renunciation of large-scale external work. The real nature of sectarianism is its transformation of the living program into a dead system, the principles that guide action into dogmas, whether they be yelled or whispered.

What we consider necessary in the present reactionary period is to make an objective study, to grasp the movement of events and their causes, and to make them understood to a circle of workers that will necessarily be limited in such a period.

Contact between revolutionary groups in various countries, the confrontation of their ideas, organized international discussion with the aim of seeking a reply to the burning problems raised by historical evolution -- such work is far more fertile, far more ‘attached to the masses' than hollow agitation, carried out in a vacuum.

The task for revolutionary groups today is the formation of cadres; a task that is less enticing, less concerned with easy, immediate and ephemeral successes; a task that is infinitely more serious; for the formation of cadres today is the precondition that guarantees the future party of the revolution.

Marco

[1] The RKD (Revolutionary Communists of Germany). They were an Austrian Trotskyist group opposed to the foundation of Fourth International in 1938 because they felt it was premature. In exile, this group moved farther and farther away from this ‘International'. They were particularly opposed to participation in the Second World War in the name of the defense of Russia, and in the end came out against the whole theory of ‘degenerated workers' state' so dear to Trotskyism. In exile this group had the enormous political merit of maintaining an intransigent position against the imperialist war and any participation in it for any reason whatsoever. In this regard it contacted the Fraction of Italian and French Left during the war and participated in the printing of a leaflet in 1945 with the French Fraction addressed to the workers and soldiers of all countries, in several languages, denouncing the chauvinistic campaign during the ‘liberation' of France, calling for revolutionary defeatism and fraternization. After the war, this group rapidly evolved towards anarchism where it finally dissolved.

[2] The CR (Revolutionary Communists) were a group of French Trotskyists that the RKD managed to detached from Trotskyism towards the end of the war. From then on, it followed the same evolution as the RKD. These two groups participated in the International Conference in 1947-48 in Belgium, called by the Dutch Left which brought together all the groups which remained internationalist and had opposed all participation in the war.

[3] We must be careful to distinguish the forming of a party from the general activity of revolutionaries which is always necessary and possible. The blurring of these two distinctions is a very common error which can lead to a despairing and impotent fatalism. The Vercesi tendency in the Italian Left fell into this trap during the war. This tendency rightly considered that the conditions of the moment did not allow for the existence of a party nor for the possibility of large-scale agitation among the workers. But it concluded from this that all revolutionary work had to be scrapped and condemned. It even denied the possibility for revolutionary groups to exist under these conditions. This tendency forgot that mankind is not just the product of history: "Man makes his own history" (Marx). The action of revolutionaries is necessarily limited by objective conditions. But this has nothing to do with the desperate cry of fatalism: ‘whatever you do will lead to nothing'. On the contrary, revolutionary Marxist has said: "By becoming conscious of existing conditions and by acting within their limits, our participation becomes an additional force influencing events and even modifying their courses." (Trotsky, The New Course)

[4] This refers to the ex-members of Union Communiste, the group that printed L'Internationale in the 30s and disappeared at the outbreak of war in 1939.

[5] The fall of the Mussolini regime and the refusal of the masses to continue the war.

[6] A little group constituted after the war, which had an ephemeral existence. Its members, after a brief passage in the ICP (Bordigists), left politics.

Deepen:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Development of proletarian consciousness and organisation:

General and theoretical questions:

Convulsions in the revolutionary milieu

- 3052 reads

The International Communist Party (Communist Program) at a turning point in its history

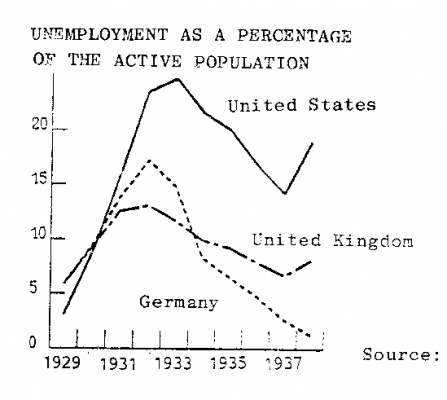

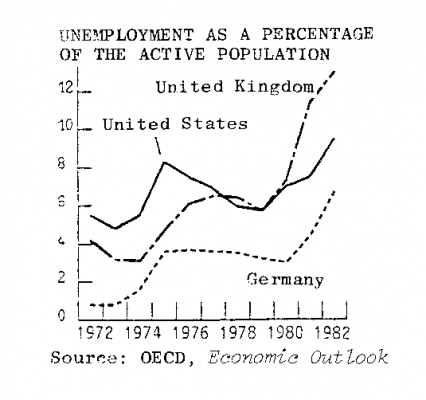

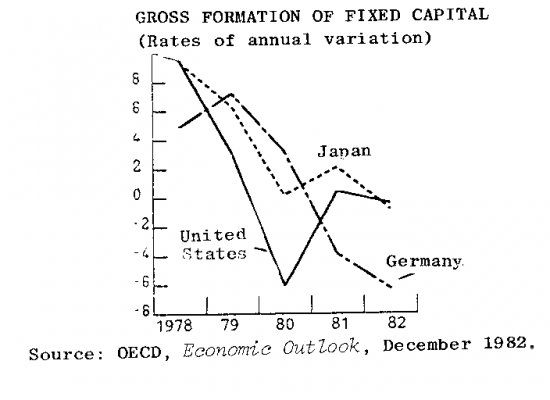

At the end of the sixties, the working class put an end to fifty years of counter-revolution by engaging in struggle internationally (1968 in France, 1969 in Italy, 1970 in Poland, 1975-6 in Spain, etc). At the present time the mass strike in Poland has marked the highest point in a new period of struggle which will lead to class confrontations that will decide the fate of humanity: either revolution or war.

On an international scale, the bourgeoisie recognizes what a mortal danger the combativity of the workers means for its system. In order to confront the danger of the mass strike the capitalist class collaborates across national frontiers and even across the imperialist blocs. The proletariat will not face a surprised and disconcerted bourgeoisie as it did in the first wave of struggle in 1968; it will confront a bourgeoisie which is forewarned and prepared to use its capacities of mystification, derailment and repression up to the hilt. The process of the international unification of the working class in its struggle for the destruction of capitalism promises to be a long and difficult one.

This is the reality confronting the revolutionary minorities who are participating in the process of the unification of the working class and in the development of its consciousness. Far from being up to the demands of the present period, revolutionary organizations are in an extreme minority. They exist in a situation of political confusion and profound organizational dispersion.

For more than a year, the weaknesses have been accentuated by splits and the disappearance of groups. This phenomenon is culminating today with the crisis shaking the International Communist Party (ICP) (Communist Program). After a wave of exclusions and numerous departures, the majority of the organization has taken up the most chauvinist and nationalist positions of the bourgeoisie, by taking sides in the imperialist war in the Middle East. This organization is paying the price of its political and organizational sclerosis.

The ICP has been unable to draw a critical balance sheet of the revolutionary wave between 1917-23 and the counter-revolution which followed it, of the positions of the Communist International and the left fractions which broke from it -- particularly on the union and national questions and on the question of the organization of revolutionaries and of the party. These, together with its incapacity to understand the stakes of the present period, have led it straight to opportunism and activism and to the dislocation of the organization.

It is the responsibility of all revolutionary organizations to draw the lessons of this crisis which expresses the general weaknesses of the revolutionary movement today, and to actively ensure that the necessary and inevitable decantation does not lead to a dispersion of revolutionary energies. History does not pardon, and if revolutionary organizations today are not capable of living up to the demands of the situation, they will be swept away without recourse, weakening the working class in its task of defending the perspectives of communism in the course of its battles.

-----------------------------------

"A crisis which is very serious for us and whose repercussions will probably be decisive throughout the organization, has just exploded in the Party". (‘Better fewer, but better', Le Proletaire no.367, Il Programma Comunista, no. 20). The articles in the press tell us of cascading departures:

In France:

-- the split of those who were regrouped around El Oumami, which used to be the organ of the ICP for Algeria, and now has become "the organ of Algerian Leninist Communists", defending bourgeois nationalist positions in a pure third ordlist style;

-- the departure of the majority of members in Paris and a few others scattered around France "amongst which were those with leadership responsibilities", apparently on positions close to E1 Oumami, with a plan by some to bring out a magazine, Octobre.

In Italy:

-- "In Italy, the crisis has shaken all the sections because of its suddenness, but only some comrades in Turin and some comrades in Florence (we don't know how many) have been involved in the liquidation" (I1 Programma Comunista, 29.10.82).

In Germany:

-- the disappearance of the section and of the publication Proletarier.

In giving this news, the press of the ICP doesn't speak of:

-- the expulsion last year of sections in the south of France, including Marseilles, by the same leadership who have now left in France, and of sections in Italy, including Ivrea.

It appears that those who were expelled put in question the whole policy of setting up a panoply of ‘committees' (‘committee against redundancies', ‘committee against repression', committees in the army, of squatters, feminists, etc) , whose objective was to better ‘implant' the Party inside ‘social struggles';

-- the departure of other elements who protested against these expulsions, and individual resignations for unclear reasons.

-- the disappearance of the ‘Latin American sector'.

The whole of the ICP has been thrown into disarray in a few months without any real clarity. Why is there a crisis? And why now?

The events taking place in today's period of mounting class struggle are starting to dissipate the mist of bourgeois ideology in the heads of workers. Further, they put the political positions of revolutionary minorities to the test by sweeping aside the debris of groups made gangrenous by bourgeois ideology and by shaking or dislocating ambiguous and useless groups.

In this sense, the crisis in the ICP is the most spectacular manifestation of the convulsions of the revolutionary milieu today. A year ago, when we spoke of convulsions, splits and regression in the revolutionary milieu (International Review, no.28) in face of the ‘years of truth', the whole political milieu turned a deaf ear. Perhaps today these people are going to wake up! The revolutionary milieu (including the ICP) didn't want to create a framework of international conferences allowing the decantation of political positions in a clear way; today they submit to a process of decantation by the ‘force of events', with all the attendant risks of a loss of militant energies. Even today reality is exposing the programmatic weaknesses of the ICP, it is still up to revolutionaries to draw up a balance sheet in order to avoid repeating the same errors ad infinitum.

It cannot be denied that for a long time the ICP has been a pole of reference, in some countries, for elements searching for class positions. But by basing itself on an inadequate and erroneous political program and on the internal structure of a sect, the ICP has been over the years, growing more and more sclerotic. Its political regression was revealed in the test of events: faced with the massacre in Lebanon, the ICP called on the proletarians in the Middle East to fight "to the last drop of blood" in defense of the Palestinian cause in Beirut. Some months later, the organization burst apart.

The crisis can't be explained by mistakes ‘made by the leadership' or by ‘tactical errors', as both the splitters and the remaining ICP seems to believe. The mistakes are programmatic and lie at the very root of the constitution of the ICP (see the articles on p.15 and p.20 in this issue). Today they are paying for these errors. The ‘return to Lenin' in order to support the ‘glorious struggle for national liberation', which the splitters advocate, in order quite simply to cover up their Maoist leanings, is very close to the position of the ICP. If the ICP is today only hanging by a thread, this way of explaining the crisis in terms of ‘tactical errors' or ‘mistakes of the leadership' is going to definitively finish it off.

A crisis which illustrates the weakness of a conception of organization

The bluff of the ICP

The crisis today leaves us with a somber balance sheet for "tomorrow's compact and powerful party". It has led, according to the ICP's press, "to the organizational collapse of the international centre and the disappearance of the former editions of Proletaire, and to the departure of all the responsible centers in France". (Le Proletaire, no.387). The militants who remain in the ICP were not aware of what was going on. They were reduced to making appeals in the press for members who wanted to remain in the party to express themselves in writing to the box address. It's unbelievable that they have had to resort to methods of communication that give the state such an easy means of identification.

The famous and arrogant ‘responsible centers' left taking with them material, and money which included the dues which had been paid that very day by local sections (according to an ICP militant in Paris). We see here the habits of bourgeois political gangsterism totally foreign to the proletariat which we unambiguously branded as such at the time of the ‘Chenier affair' during the crisis of the ICC (International Review, no.28). The grand, high-sounding words on the ‘centralized' pure and hard party were only a bluff. The ICP is collapsing like a house of cards: "the crisis was expressed by a decentralized and localist activity, covered up by a facade of centralization" (Il Programma Comunista, 29.10.82).

The grand speeches on ‘organic centralism' hid a federalism of the worst kind where each part of the organization ended up only doing what it decided to do, a flabby structure open to all the influences of bourgeois ideology, a true nursery of irresponsible people, of apprentice bureaucrats and future recruiting sergeants for imperialist massacres, as has already happened for the Middle East.

After having prattled on for forty years about the party which ‘organizes' the working class, you can't fall any lower than this.

Perhaps this crisis will serve as a lesson to all the groups in the present movement who reduce any debate to the question of the party, who bestow upon themselves titles of glory which they have done nothing to merit, who shackle any real progress towards a true party of the working class by their absurd pretensions today. To explain all the difficulties of the class struggle internationally as being due to the absence of the party, to put forward the idea that this eucharistic presence is the only perspective for solving everything, as the ICP has done for years, is not only false and ridiculous it also has a cost. As we said in International Review no.14:

"The drama of Bordigism is that it wants to be what it isn't -- the Party -- and doesn't want to be what it is: a political group. Thus it doesn't accomplish, except in words, the tasks of the party, because it can't accomplish them; and it doesn't take on the tasks of a real political group, which to its eyes are just petty. (‘A Caricature of the Party: the Bordigist Party').

Where then is this famous ‘monolithic bloc' of a party? This party without faults? This ‘monolithism' asserted by the ICP has only ever been a Stalinist invention. There never were ‘monolithic' organizations in the history of the workers' movement. Constant discussion and organized political confrontation within a collective and unitary framework is the condition for the true solidarity, homogeneity and centralization of a proletarian political organization. By stifling any debate, by hiding divergences behind the word ‘discipline', the ICP has only compressed the contradictions until an explosion was reached. Worse, by preventing clarification both outside and inside the organization, it has numbed the vigilance of its militants. The Bordigist sanctification of hierarchical truth and the power of leaders have left the militants bereft of theoretical and organizational weapons in the face of the splits and resignations. The ICP seems to recognize this when it writes:

"We intend to deal (with these questions) in a more developed way in our press, by placing the problems which are being posed to the activity our party before our readers". (1l Programma, idem)

For the moment these words seem more like a wink to the militants who have left in a state of complete political confusion, some of whom must be aware of the mire into which they have sunk, than a real recognition of the bankruptcy of the ICP, ‘alone in the world', as it describes itself. The recognition of the necessity to open up the debate on the "problems being posed to the activity" and the actual opening up of discussions both internally and externally, is one of the conditions for keeping the ICP within the proletariat, for fighting against the political decay which is gnawing at the organization. The ICP has experienced other splits in its forty years of existence, but today's one is not only shaking its organizational framework, but also the fundamentals of its political trajectory, placing before it the alternative: third worldism or marxism.

Internationalism against any form of nationalism

The open nationalism of El Oumami

El Oumami broke with the ICP because their defense of the PLO in Beirut had met with resistance. But judging by the positions of the ICP on the question, this resistance must have been rather weak. The only point at issue seems to have been how far one should go in defending the PLO. El Oumami entitled the document in which it declared itself ‘From the program-party to the party of revolutionary action'. A whole program!

El Oumami defends the progressive character of the Palestinian national movement against "that cancer grafted onto the Arab body, the Zionist, colonialist entity, the mercenary, racist and expansionist state of Israel". For El Oumami it is out of the question to put on an equal footing the "colonialist-Settlers' state" (Etats-pied-noir) and the "legitimate states" of the "Arab world".

This type of distinction has always been the argument used by the bourgeoisie to enlist the working class into war. Yes, all capitalist states are enemies of the revolution, so we are told, but there is enemy no.1 and enemy no.2. For the first world war German Social Democracy said in essence ‘let us fight against Russian despotism'; for the other side, it was ‘let's fight against Prussian militarism'. In the second world war, it was with the same language that all the ‘anti-fascists' with the Stalinists at their head, enlisted the proletarians, by calling on them to participate in fighting enemy no.1, the ‘fascist state', in order to defend the ‘democratic' state.

For E1 Oumami, the ‘Jewish union sacree' has made class antagonisms disappear in Israel. It is useless to make appeals to the proletariat in Israel. This is precisely what the Stalinists said during the Second World War when they talked about the ‘accursed German ‘people'. And when, after a ‘Solidarity with the PLO' demonstration, El Oumami, to the cries of "Revenge for Sabra and Chatila", bragged of having "captured a Zionist and giving him a good duffing up", it was the same as the French Communist Party's "to each a boche" at the end of the second world war.

E1 Oumami has joined the ranks of the bourgeoisie with this abject chauvinism. At this level, it is a Maoist, virulently third-worldist group, which doesn't merit much time being spent on it. But what is striking, in reading the texts, is that these nationalist chauvinists are full of the words of the Italian Left, that fraction of the International Communist Left which was one of those rare examples and the most important, that was able to resist the counter-revolution and maintain a proletarian internationalism in the whirlpool of the second imperialist war.

How could the ICP, ‘continuator' of the Italian Left, develop such a nationalist poison within it? How could it affect the Paris leadership, the editors of Proletaire, the editors of E1 Oumami, the section in Germany?

In the third part of this article we shall recall how the ICP conceived this child by forgetting a whole period of the history of the Italian Left between 1926 and 1943; how the ‘Party' was formed in 1943-45 with elements from the Partisans in Italy and the ‘antifascist committee of Brussels', how political confusions on the role of ‘anti-fascism' and the nature of the blocs set up at the end of the second world war were never clarified. Today all this has broken through to the surface.

Because the ICP nourished this child and even today still recognizes it, it is now the legitimate product of its own incoherence and degeneration.

The shameful nationalism of the ICP

"Naturally for the true revolutionary, there isn't a ‘Palestinian question', but only the struggle of the exploited of the Middle East, both Arabs and Jews, which is part of the general struggle of the exploited of the whole world". (Bilan, no. 2)

E1 Oumami deserts this position: schooled in the ICP's tactics, it poses the question not in terms of classes but in terms of nations. The future ‘party of revolutionary action' therefore puts its begetter, the ICP, against the wall, knowing full well its congenital incoherence, and hurls a defiance to it:

"Let's imagine for an instance the invasion of Syria by the Zionist army. Must we remain indifferent or worse (sic), call for revolutionary defeatism under the pretext that the Syrian state is a bourgeois state that needs to be overthrown? If the comrades of Proletaire are to be consistent, they must say so publicly. As for us, we openly take a position against Israel".

And further:

"Le Proletaire pronounces itself for the destruction of the Colonialist-Settler state of Israel. So be it. But at the same time, it supported the submission of the Palestinians to a national oppression in the Arab countries, when Israel entered Lebanon in order to continue Syria's work. So then, where does the specificity of Israel lie? Do we have to believe that the destruction of the Colonialist-Settler state has the same significance as the destruction of the Arab states, however reactionary they are?".

For E1 Oumami, it's clear: class criteria don't apply to an Arab proletarian. His state is an Arab state, and that's that. First the war, then the bright tomorrow.

But how does the ICP reply? What does the historic party, the intransigent defenders and heirs of the Italian Left have to say? Just a small "yes, but...".

The article ‘The national struggle of the Palestinian masses within the framework of the social movement in the Middle East', published in Le Proletaire and Il Programma, begins by preaching to us about pan-Arab feelings, Arab capital, the Arab unitary tendency and the Arab nation. It's like the dream of a university student who missed the mark at the end of a course on pan-Slavism, black studies and other Guevarist preoccupations from the sixties.

"Arab capital" doesn't owe allegiance to American capital - ...that would be a "superficial" vision. On the other hand, the "colonialist Jewish state" is "constitutionally" in this position. The ICP doesn't say that Israel is totally a classless bloc, but that the proletarians there seem to it to be "more anti-Arab than the bourgeoisie". Xenophobic sentiments of course never touch Palestinian or French or Italian proletarians. And to finish up, we are left with the lowest level of Maoism that could be cooked up -- a reheated version of the kind pioneered by the American ‘Students for a Democratic Society', who talked about the working class having "white skin privilege", through which they exploited the black workers of America.

As for the PLO, it remains a defender of widows and orphans in "the most advanced part of the gigantic social struggles in the Middle East".

The ICP affirms:

"It is precisely on the terrain of the common struggle (ie. common to the bourgeoisie and the proletariat) that Arab and Palestinian proletarians can acquire the strength to stand up against those who are their apparent allies, but who in reality are already their enemies".

Who? What? Ah, but it is only

"the appearance which is inter-classist",

Bordigist science tells us . .. In reality the class struggle

"lives inside physical subjects themselves... beyond, outside and even against the consciousness of individuals themselves".

The ICP replaces politics by individual psychology.

"It is necessary to strengthen the national struggle by taking out, the content which the bourgeoisie takes care to give it".

This is called defending the ‘double revolution' by doing so and not doing so....

The article of clarification (?) ends up quite simply, in delirium. It is necessary to "build an army under proletarian leadership thanks to the organizational work of communists", in order to create a "co-belligerent" with the PLO army.

The ICP dishes out the same lamentations as the splitters:

"The proletariat in the metropoles isn't really going into action".

So --

"in its place, one could look to the movements of the young, of woman, to anti-nuclear and pacifist movements". (Le Proletaire, no. 367).

This is the sad refrain of all thirdworldists, students, the blase and the modernists: the proletariat is ‘letting us down'.

As the ICP claims to be the party already, its children can only want the movement ‘immediately', hence its description of those who resigned or split as ‘mouvementists'. But El Oumami was only taking the leftist tendencies in the ICP to their logical conclusion. It will not be easy for the ICP to get out of this leftist pit. It is not taking that path. For now, it means its ‘mea culpa' on exactly the same ground as E1 Oumami. The party doesn't know how to make "the tactical link" with the masses; it is still too ‘abstract' too ‘theoretical'. All this is false. The ICP uses the words ‘communist program' in order to cover up a ‘theoretical void' and a practice of supporting nationalism, of unprincipled activism. We are now going to examine in more detail this theoretical void and its practical ramifications.

The sources of errors: the theoretical void

"Men make their own history, but not of their own free will; not under circumstances they themselves have chosen but under the given and inherited circumstances with which they are directly confronted. The traditions of the dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the minds of the living". (Marx, The 18th Brumaire).

The CI and the Lefts

In order to explain the crisis of the ICP you have to go back to the roots of its political regression, to the lack of understanding of the errors of the Communist International and to the necessary critical re-examination of the past which the present milieu has neither wanted nor been able to do.

The Communist Left of the 20's didn't seek to explain the degeneration of the CI by a ‘crisis of leadership' nor simply by ‘tactical errors', as the ICP today wants to explain its own crisis. That would have been to reduce the crisis of the CI to the Trotskyist line that "the crisis of the revolutionary movement can be reduced to the crisis of the leadership", (Trotsky's Transitional Program). The Communist Left took into account that the CI was founded during an international revolutionary wave that arose suddenly from war and that it hadn't succeeded in grasping all the demands of the "new period of war and revolution". Each Congress of the CI testifies to the increasing difficulties felt in grasping the implications of the historic crisis of capitalism, in throwing off the old social democratic tactics, in understanding the role of the party and workers' councils. To draw all the programmatic implications of such a situation was impossible during their tumultuous times. To try today to elevate into dogmas everything that the CI produced means turning your back on the Communist Left.

The Lefts within the CI, the German, Italian, Dutch, British, Russian and American Lefts, were the expression of the avant-garde of the proletariat in the major industrial centers. With its hesitant and often confused formulations, the Left tries to pose the real problems of the new epoch: are the unions still working class organs or have they been caught up in the machinery of the bourgeois state? Should you finish with the tactics of ‘parliamentarism'? How should one understand the national struggle in the global period of imperialism? What is the perspective for the new Russian state?

The Communist Left never managed to act as a fraction within the 111rd International, to confront it with its positions. In 1921 (when the ‘provisional' banning of fractions in the Bolshevik Party in Russia took place), the German Left (KAPD) was excluded from the Communist International. The successive elimination of all the Lefts followed until the death of the CI with its acceptance of ‘socialism in one country'.

If the Lefts were already dislocated within the CI, they would be even more so outside it. At the time of the death of the CI, the German Left was already dispersed into several bits, fell into activism and adventurism, and was eliminated under the blows of a bloody repression; the Russian Left inside Stalin's prisons; the weak British and American Lefts had long since disappeared. Outside Trotskyism, it was essentially the Italian Left and what remained of the Dutch Left which, from 1928 on, would maintain a proletarian political activity -- without Bordiga and without Pannekoek -- by each making a different assessment of the experience they had had.

The revolutionary movement today still has a tendency to see only the partial and dislocated form of the Communist Left, as it was left by the counter-revolution. It speaks of this or that positive or negative contribution of this or that Left outside the global context of the period. The ICP has accentuated and aggravated this tendency by always reducing the Communist Left to the Italian Left, and then only the Left between 1920 and 1926. For the ICP, the German Left became a bunch of ‘anarcho-syndicalists', identical to the Gramsci tendency. This is not to say that one must not severely criticize the mistakes of the German Left, but within the ICP these become a total caricature. The idea of restoring the heritage of the Communist Left which was buried by the counterrevolution becomes in the ICP an endless process of republishing Bordiga's texts. The heritage of the Left is above all a critical work: the ICP has reduced it to the liturgy of a jealous sect. Thus, a whole generation of ICP militants only has a deformed idea of the reality of the International Communist Left and the political questions they posed.

The period of the ‘fraction' and Bilan (1926-1945)

The Bordigists never speak of this period of the Italian Left: it's not acknowledged by the ICP. What becomes then of the ‘organic continuity' which the ICP lays claim to in order to announce itself as the one and only heir of the Communist Left?

A whole twenty years of militant work. But ...Bordiga wasn't there during those years. The only explanation one can find is that ‘organic continuity' means the presence of a ‘genial leader'.

The Italian Left in exile around the magazine Bilan continued the work of the Communist Left with the watchword of the times: "Don't betray". The reader will find the details of this period in the ICC pamphlet called La Gauche Communiste d'Italie (available in French) .

In order to continue its activity during a period much more difficult than the present one, it rejected the method which consisted of turning Lenin into a bible. It gave itself the task of drawing the lessons of the defeat by sifting the experience ‘without censorship or ostracism' (Bilan, no.1). In exile, the Fraction enriched its contributions with the Luxemburgist heritage through, amongst other things, the support of militants in Belgium who rallied to the Italian Left. As the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left, it took up the whole work of the Left: by rejecting the defense of national liberation struggles; by putting into question the ‘proletarian' nature of the unions (without ending up with a definitive position); by analyzing the degeneration of the Russian revolution, the role of the state and the party. It outlined the historic perspective of the period as a course towards world imperialist war and this was done with such a degree of clarity that it was one of the only organizations to remain faithful to proletarian principles, by denouncing anti-fascism, popular fronts and participation in the defense of ‘Republican' Spain.

The war numerically weakened the Fraction but the ICP completely hides the fact that it did maintain its political activity during the war, as witnessed by the bulletins, leaflets, Conferences and constitution (in 1942) of the French circle of the Communist Left which published Internationalisme. Towards the end of the war, the Fraction excluded one of its leaders, Vercessi, condemning his participation in the Brussels ‘Anti-Fascist Committee', (just as it had excluded the minority which let itself be dragged into the anti-fascist enrolment for the war in Spain). In contrast, the ICP, being formed in Italy in 1943, flirted with the ‘Partisans' and made Appeals for a united class front with the Stalinist CP and the Socialist Party of Italy (see the article ‘The ICP: What it claims to be and what it is', in this issue of the IR).

The formation of the ICP

The International Communist Party of Italy was formed on the basis of a heterogeneous regroupment: it demanded the dissolution of the Fraction, pure and simple, while groups of the ‘Mezziogiorno', who had ambiguous relations with anti fascism, the Trotskyists and even the Stalinist CP, were integrated, albeit with Bordiga's caution, as constitutive groups. Vercessi, and the minority excluded on the question of Spain, were likewise integrated without discussion.

"The new party isn't a political unity but a conglomerate, an addition of currents and tendencies which cannot help but clash. The elimination of one or other current is inevitable. Sooner or later a political and organizational delimitation will impose itself". (Internationalisme, no. 7, February 1946).

Indeed, the Damen tendency split from the Party in 1952, taking the majority of the members and the newspaper Battaglia Comunista and the publication Prometeo.[1]

All the political and theoretical work of the Fraction disappeared so that the ICP could be formed in an immediatist and unprincipled regroupment. The ICP turned its back on the whole heritage of Bilan: on anti-fascism, the decadence of capitalism, the unions, national liberation, the meaning of the degeneration of the Russian Revolution, the state in the period of transition. All this heritage the ICP considers ‘deviations' from the ‘invariant' program. For the new ICP the Stalinist parties are ‘reformist'; Russia is a less dangerous imperialism than enemy no.1, US imperialism; the historic decadence of capitalism becomes ‘cyclical and structural crisis'; the theoretical acquisitions of Bilan on the program, are replaced by a return to ‘Leninist tactics'. Thus the ICP helped to take debates in the revolutionary movement back twenty years, to the time of the CI, as though nothing had happened between 1926 and 1945.

While Bilan insisted that a party can only be formed in a period of mounting class struggle, the ICP proclaimed itself the ‘Party', in a period of utter reaction. Thus, they created a ‘tradition' in which anybody can call themselves a ‘party', at any time.

The re-examination of the lessons of the past which Bilan carried out became, in the ICP, the ‘invariant' program, ‘fixed for all time', ‘undiscussed and undiscussable'. Instead of a critical examination of the past, a ‘restored' marxism was created, with an ‘immutable' nature, transformed into a liturgy inside a monolithic structure where only the voice of the master, Bordiga, was permitted to be heard. On the basis of a theoretical regression and an absolute isolation, with the germs of activism and an ambiguity on principles from its birth, with the internal structure of a sect, the ICP could only become sclerotic and paralyzed. What Internationalisme wrote in 1947 has become prophetic:

"More than its political errors, it is its organizational conceptions and its relations with the rest of the class, which make us doubt the possibility of the ICP of Italy correcting itself. The ideas which came to the fore at the end of the revolutionary life of the Bolshevik party and which marked the beginning of its decay: the forbidding of Fractions, the suppression of free expression in the party and in the class, the cult of discipline, the exaltation of the infallible leader, today serve as the very foundations of the ICP in Italy. If it persists on this path, the ICP will not be able to serve the cause of socialism. It is with a full consciousness of the whole gravity of the situation that we cry: ‘Stop there. You must turn back, for the slope here is fatal'." (Internationalisme, ‘Present-Day Problems of the Workers' Movement', August 1947).

Today, the ‘tactical' plan which the ICP searches for like a Holy Grail is only a subterfuge to avoid the real, necessary theoretical and political work.

The reawakening of the class struggle

When the period of reconstruction came to an end with the resurfacing of the crisis of capitalist decadence, when the first wave of class struggle, from the end of the sixties to the mid-seventies took place, marking the end of the period of counter-revolution, the ICP, faithful to the diktat of Bordiga that the crisis would break out in... -- 1975, didn't make the connection. Fixed in its ‘invariant' immobility, it wasn't to be found during the 1968 strikes in France or in Italy in 1969, but it was waiting for "the masses to line up behind its banners". The overflowing of the unions, the rejection of parliamentarism, and the growing disillusion with the results of ‘national liberation struggles', which these battles produced, found no response within the ICP. It didn't speak to the new generation with the voice of Bilan, and Internationalisme, but with that of the mistakes of the CI, elevated into dogmas. The total incomprehension of this period is today summed up by the fact that discontented militants reproach the ICP for not having supported the "glorious struggle for national liberation in Vietnam".

This first wave of struggle against the crisis didn't leave sufficiently solid acquisitions to ensure a political stability to the new groups and elements who emerged. The situation had to mature, and revolutionary minorities had to retie the historic thread by working towards political clarification.

In order to ensure the necessary critical reexamination of the past, in order to avoid the dispersion of revolutionary energies, an International Conference of discussion was called for in 1976 with political criteria defining the framework of the Communist Left. The ICC participated in this work with all its strength. The Conferences (see the minutes in the Bulletins of the International Conferences, see the IR nos.16, 17, and 22), like that at Zimmerwald at the time of World War 1, attempted to provide a framework for the decantation which would inevitably be produced within the movement in a period of crisis and upheaval.

In a period of mounting struggles, the possibility and necessity of working towards the regroupment of revolutionary forces is the expression and the spur for a process of unification of the international working class. But for the ICP, the very word ‘regroupment' is blasphemous, for it is already the Party.

For the ICP, we were only the "debris of the revival of the class". The party rejected any idea of a conference of international discussion, considering that between revolutionary groups, it is possible to have relations of force: the "fottenti e fottuti" (crudely speaking, the fuckers and the flicked). Indeed, why discuss when the ICP has already so infused the truth that the militants of the organization mustn't buy the press of other ‘rival' organizations, because that would only give them money!?

"The Party can only grow on its own basis, not through a ‘confrontation' of points of view, but through a clash against others, even those who seem close". (‘On the Road Towards the Compact and Powerful Party of Tomorrow', Programme Comuniste, no.76)

Today we can see how the ICP has grown on its own basis:

This sectarian attitude isn't the prerogative of the ICP. The ex-Pour Une Intervention Communiste (PIC), the Fomento Obrero Revolucionario (FOR). the Groupe Communiste Internationaliste (GCI), all considered these Conferences as a ‘dialogue of the deaf'. You only discuss when you agree! It's more peaceful! Even the PCInt-Battaglia Comunista who put out the first appeal for the Conferences hasn't truly understood why they were necessary. For the PCInt, since it is also imbued with Bordigist self-satisfaction, they had to serve as a spring-board towards a "common practical work" in order to respond to the "social democratizations of the CP's" (see the letter of appeal for the 1976 Conference). In order to convince the PCInt to invite other Bordigist parties, this organization had to be pushed, quite hard, and it was only too happy when they turned the invitation down.

But even a beginning of political clarification was too much for the PCInt and the Communist Workers' Organization. They ‘excluded' the ICC at the 3rd Conference because of its disagreements on the question of the party, not after a profound discussion, but a priori, after a maneuver worthy of the most sinister intrigues of a Zinoviev in the degenerating CI. What a fine school Bordigism is! Especially if you touch their fetish, the party -- which they alone know how to build, with the results that are now well known. At a recent meeting, called the ‘4th International Conference of the Communist Left', which Battaglia sees as "an indisputable step forward from the preceding conferences" (Battaglia Comunista, 10.11.82), Battaglia and the CWO "began to deal with the real problems of the future party" ... with a group of Iranian students who have hardly broken from thirdworldism. After all, everyone has a people to liberate: Programma its Palestinians, Battaglia its Iranians.

But during this period, 1976-1980, the ICP did, despite it all, begin to feel that it was time to ‘move'. Having turned its back on international political clarification, and without a coherent analysis of the new period, the ICP simply swapped its immobility for frenzied activism: two sides of the same coin. Today, seeing the organization in tatters, what does the ICP emphasise? ‘Tactics' once again -- and not only for the national question, but for everything.

The ICP transformed the anti-parliamentarism of the Abstentionist Fraction into a ‘tactic' and then called for participation in elections and referendums. It calls for the defense of ‘democratic rights' for immigrant workers, including the right to vote. Why? So that it can afterwards tell them not to vote? Now we see what happens ‘afterwards'. ‘Anti-narliamentarism' has become purely verbal, separated from any coherence about the historic period of capitalism.

Union ‘tactics', frontist committees, critical support for terrorist groups, like Action Directe in France - it's OK as long as it helps to ‘organize' the masses.

And in Poland, the ICP saw the saboteurs of class autonomy, Solidarnosc and its advisors in the KOR, as the ‘organizers' of the class movement -- the ones who did everything they could to drag the movement onto the terrain of defending the national economy. And the ICP calls for the ‘legalization' of Solidarnosc, alongside the democratic bourgeoisie!

Not wanting to discuss with the "debris of the class revival", the ICP preferred to recruit from the residues of the decomposition of Maoism. When the ICP played the policeman, the ‘steward' against the ‘fascist danger' at demonstrations of immigrant rent strikers in France -- which in fact meant forbidding the distribution of the revolutionary press -- this was a symbol of its descent down the slippery slope of leftism.

Perspectives

The ICP should have rejected the position of E1 Oumami a long time ago, before this gangrene penetrated the organization. E1 Oumami sings the siren song that lures the ICP towards the coherence of the bourgeoisie. The ICP can no longer take refuge in incoherence and jargon. Patch-up jobs don't last long in the present period. In the first place, the ICP and the whole revolutionary milieu have to recognize clearly that in this epoch internationalism can only mean a total break with all forms of nationalism, an intransigent struggle against any national movement, which today can only be a moment in the struggle between imperialist powers large or small. Any wavering on this question immediately opens a breach to the pressure of bourgeois ideology which will quickly and ineluctably lead a group towards the counter-revolution.

It's not too late for the ICP to draw back, on condition that it has the strength and the resolve to look reality in the face, to re-examine the lessons of the past, to review its own origins in a critical manner.

There have been other departures from the ICP over the past year, but we don't know exactly what has become of these militants. In Marseille there survives a circle which says ‘the formal party is dead, only the historic party lives on.' This Bordigist vocabulary isn't very clear to common mortals: does the ‘historic party' mean the Bordigist program? Marxism? What balance-sheet has to be drawn and why are these elements silent today?

Others left the ICP because of the stifling organizational atmosphere and out of instinctive reaction against degeneration. But you have to go further than a mere observation. You have to go to the roots of the disease.

You can't stop half-way, in the belief that you are ‘restoring' a ‘true' Bordigism which doesn't exist, the pure Bordigism ‘of Bordiga', which never existed. This path leads to the land of small sects, to tinier and tinier ‘Partiti', each one claiming the legitimate title, each one ignoring the others. We've seen this with numerous Bordigist splits over the years. Each one claims to be the true ‘leadership' that will guide the working class to paradise.

Political clarification can't come out of patch-up jobs, or out of isolation. It can only be done with and in the revolutionary milieu. The spell of silence has to be broken, by opening up a public debate, in the press, in meetings, to finish with the errors of the past, to ensure that this decantation takes place in a conscious way, to avoid the dispersion and loss of revolutionary energies. This is the only way to clear the ground for the regroupment of revolutionaries, which will contribute to the unification of the international working class. This is the task of the hour; this is the real lesson of the crisis of the ICP.

JA

[1] After the split Bordiga's party became the Partito Communista Internationale. Many ex-members of the Fraction left with Damen and the program of Battaglia Communista (PCInt) in 1952 contained certain important positions of Bilan on the national question, the union question, on Russia. Unfortunately, the thirty years that separate us from the beginnings of Battaglia saw this group get caught up in a process of sclerosis. This can be easily seen by reading its press today and comparing it to the platform of 1952.

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Political currents and reference:

- Communist Left [5]

Critique of the Groupe Communiste Internationaliste

- 2352 reads