1982 - 28 to 31

- 4579 reads

International Review no. 28 - 1st Quarter 1982

- 2391 reads

Class struggle in Eastern Europe (1970-80) - part 1

- 3457 reads

The importance of the revolutionary wave of 1917-23, and even of the wave of class struggle which swept Eastern Europe in 1953-56, was not least to have shown the potential which exists for the internationalization of the proletarian struggle, for the real constitution of the working class as a single, unified, world-wide revolutionary force. But, as we saw in part 1 of this article, this potential could not be realized at that time. These class movements of millions of workers were shattered by their isolation at a world scale. As we saw, the history of the great upheavals of the eastern and central European workers from the 20's to the 50's is, above all, the history of their isolation from the rest of the proletariat. This came about because, in addition to all the permanent barriers which capitalism imposes on the working class (into factories, industries, nations etc.), a global shift in the balance of class forces took place at the beginning of this century, in favor of the bourgeoisie, which would determine the whole development of the class struggle for six decades. The decisive moment in this process was the inability of the proletariat to prevent the outbreak of World War I. The result of this unprecedented defeat which was August 1914, was to give free reign to the barbarism of decadent capitalism, to imperialist war, which split the world proletariat right down the middle. The tendency of capitalism in its period of imperialist decline is not only to reinforce the unity of each national capital around the state, but also to divide the world into two great warring imperialist camps. The result for the proletariat which was not strong enough to confront and destroy this system before it collapsed into barbarism, was to have its organizations, its political lessons, its traditions of struggle wiped out in an ocean of blood and misery.

As we saw in part 1, the revolutionary wave was confined mainly to the countries defeated in World War I, whereas the struggles of the 50's remained within a Russian Bloc emerging out of the 1939-45 carve-up, which had to brutally concentrate its forces and frontally attack the proletariat in order to try and keep pace with the American Bloc, and therefore hardly benefited from the post-war reconstruction boom. The consequences of this international isolation of militant parts of the proletariat, imposed by the divisions of imperialism itself, are extremely grave:

-- It becomes impossible for the proletariat as a whole even to begin to attack the roots of the system of exploitation they are fighting against, since this can only be done on a world scale.

-- The power of the world bourgeoisie remains intact, and is directed against the proletariat in a unified, co-ordinated manner.

-- The working class is prevented from fully understanding the tasks of the period, since a revolutionary consciousness is based precisely on the understanding of the everyday experiences of the struggle (the defeats organized by the unions, the brutal reality behind the mask of democracy etc), as being part of the conditions of workers everywhere, indissolubly bound up with and pointing towards the need to smash the system worldwide. This profound insight can only be the product of the world wide struggles of the workers, meeting the same conditions, the same tasks, and the same enemy everywhere. It is in the heat of worldwide generalization of struggles that the international unity of the proletariat will be forged.

In the present, second part of this article we are examining the development of the proletarian struggle in the 1970's and into the 80's. It is the end of the counter-revolution, the beginning of the international resurgence of the proletarian fight. It is the end of the isolation of the workers of the east. It is the period of the redressing of the global balance of class forces, which for over half a century stood in favor of capitalism. For the first time ever, the period opening up is one of simultaneous generalization of the economic crisis and of the proletarian resistance across the globe. This international response of the proletariat has forced the world bourgeoisie to unite its forces, to prepare to confront and defeat the workers in order to open up the path to its own 'solution' to the crisis ‑ global war. In this way, by blocking off the road to imperialist war, by raising the specter of the proletarian revolution, the working class has progressively closed off the split torn within its ranks by two imperialist world wars. The last decade has shown that the conditions of struggle of the workers, and the response of the bourgeoisie, are becoming more and more unified. It is a world moving, not towards war but towards worldwide class war.

The conditions of the working class in the ‘socialist paradise'

Since the end of World War 2, daily life for workers in Eastern Europe has come to resemble the ‘home front' of a world in a permanent state of war. The naive belief of the post-war Eastern European working class in the possibility of a better life under capitalism is a good example of the fact that, in the epoch of world capitalism, the conditions prevailing at the global level are more important in determining the state of consciousness of the class in any one region of the globe than are the specific conditions prevailing in that region. There was nothing in the everyday life of the workers of the east to nourish illusions in the progressive nature of their ‘own' regimes! They had to go hungry, in order that tanks could be built. They had to queue for hours for the most basic foodstuffs. Every protest, every class resistance, was considered mutiny and treated as such. In a world still dominated by the antagonism between rival imperialist blocs, and not yet by the battle between classes, the illusions of the workers -- especially in the east -- concentrated above all on conditions in the other bloc. The western illusions in the progressive nature of the ‘socialist' east, and the Eastern illusions in the permanent and paradisical nature of the western post war reconstruction, which they hoped ‘their' bourgeoisie would sooner or later be drawn into, were two sides of a single coin. It was a period when the conditions of struggle in the 2 blocs were radically different, which itself lent credence to the myth that contending social systems were in operation in east and west. In the west the class struggle was declared to be a thing of the past. In the east, where it wasn't supposed to exist anymore either, it was even harder to hide. The struggles there were explosive but isolated, and could be presented to the workers in the west as national liberation movements or as reactions to the flaws of an otherwise genuine socialism. In the East and in the West, the crisis in the Russian Bloc became so oppressive and so permanent that it was possible for the world bourgeoisie to declare: "That's not crisis, that's Socialism"!

Autarky and the war economy

Only through the severest autarchy can the countries of the Russian Bloc prevent themselves from falling under the control of American imperialism. The direct and unlimited control of the economy and of foreign trade exercised by the state in these countries, the restrictions on direct investment of capital from the west, on East-West trade, on the movement of labor etc, are not at all proofs of the non-capitalist nature of COMECON, as the Trotskyists pretend. They serve exclusively the preservation of the Russian bloc against western domination.

In having to isolate themselves from the main centers of world capitalism, the already uncompetitive national capitals of the east fall even further behind the technological level of the west. Their progressive loss of competitiveness means that they are only able to realize a fraction of their invested capital on the ‘world market'. The lions' shares of commodities produced by COMECON are sold within its borders. Like any individual capitalist who has to buy his own produce because he can find nobody else to take them, the laws of capitalism dictate that the Russian bloc go out of business sooner or later. Only, at the level of national capitals and imperialist blocs, the verdict of bankruptcy only finally falls with the outcome of imperialist world war.

In order to evade the verdict of history, the Eastern European bourgeoisie has to try and keep up with the west at the military level. To even attempt this, it must invest a much higher proportion of its wealth in the military sector than the west. Building up for years behind the autarchy lines drawn up at Yalta and Potsdam, the "Socialist Countries" were able to achieve spectacular growth rates during the 50's and 60's. But apart from the war sector there was little real growth, just a spewing up of often unusable industrial goods, which in the west would find a market only at scrap yards.

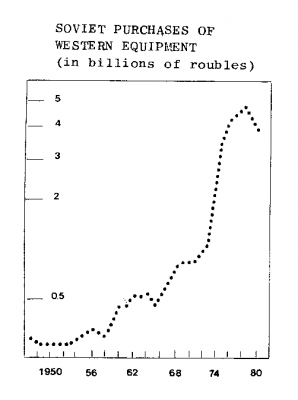

In the 1970's COMECON began to open itself up somewhat more to the west. This did not take place, as the Trotskyists reported, in order to raise the living standards of the workers. Nor did it signify, as many western politicians believed at the time, a capitulation of the Kremlin before the western money-bags. The opening took place in order to modernize a hopelessly outdated war machine. This opening could pretend to banish the danger of world war, and to open up a new era of economic expansion. For the workers of the east, this modernization meant a temporary increase in the supply of certain consumer goods, and increased possibilities of visiting, or even of working in the west. Poland, possessing as it does large reserves of coal, an ice free coastline, and large reserves of cheap labor power slumbering in the agricultural sector, was specially selected by the Kremlin to become the motor force of the modernization. This is why Poland became the focal point of the contradiction between the false illusions nourished by the modernization on the one hand, and the real stepping up of the war economy on the other. As such it became the most important centre of the development of the class struggle for over a decade.

The ‘70's saw the first dents appearing in the illusions concerning the west, caused by the sharpening of the crisis and the class struggle there. Nevertheless, this decade was characterized above all by the slump in the living conditions of the workers accompanied by heightened illusions in a future of peace and prosperity. This explosive contradiction between illusion and reality broke to the surface after the downturn in the world economy at the end of the 70's. Its first fruits in the 1980's, the years of truth, have been the mass strikes in Poland, and the world wide echo which these struggles have found.

The ‘Acquisitions of October'

Whether in the east or in the west, there are no lack of defenders of the ‘gains of the October Revolution' which the workers of the Russian bloc are supposed to enjoy. We will examine some of these gains. For example, the alleged rise in real wages and shortened working hours. Based on official figures, and on sources such as Nikita Kruschev's own memoirs, Schwendtke and Tsikarlieff, coming from Russian dissident circles, calculate the following:

"In a word, whether according to the soviet or to foreign information, the fixing of the average income of industrial workers in Russia before the First World War at 60 to 70 roubles a month can be taken as accurate. This means that the present earnings, corresponding to the nominal value of the rouble, are twice as high as before the revolution, and that in the face of prices, which are 5 to 6 times higher, today's worker in the USSR lives 2-1/2 to 3 times worse than before the revolution. The number of working days in the year in the soviet era, despite the introduction of the 5 day week, is higher than before the revolution, as a result of the many church holidays, which were observed in the old period. Whereas today there are 8 free days a year and the general number of days worked total 252, the working year before the revolution consisted of only 237 days, which by the way amounts to an average working week of 4-1/2 days...If we divide the monthly income -- 150 soviet against 70 Czarist roubles -- by the number of' work days in the month (21 days in the USSR, 19.75 in Russia) we get a daily earnings of 7.14 roubles in the USSR and 3.54 in Russia. We now give the prices of the most important foodstuffs.

|

|

Russia 1913 |

USSR 1976 |

|

Bread 1kg |

6.7 Kop. |

18 Kop. |

|

Sugar 1 kg |

30 Kop. |

90 Kop. |

|

Butter 1 kg |

1 Rouble |

3.6 Roubles |

|

Meat 1 kg |

40 Kop. |

2.5 Roubles" |

|

See Arbeiteropposition in der Sowjetunion; Schwendtke Hg. |

"A 1967 handbook of Soviet labor statistics showed that over 20% of workers employed in the highest paid sector, the construction industry, were below the poverty line, and over 60% of those in the low paid textile and food industries were under the poverty line." (‘The Soviet Working Class, Discontent and Opposition'; M. Holubenko in Critique.)

In the Russian bloc women are almost totally employed. East Germany for example has the highest rate of women employed in industry in the world. They play a similar role to the immigrant workers in the west, receiving on average half the male salary. They are employed not only in factories, but also on building sites, in the construction of roads and railways, for example in Siberia, etc.

"Recently the road from Rewda to Swerdlowsk has been widened through the addition of a second lane. This extremely severe physical work was carried out by 90% women. They worked with picks, shovels and crowbars. In fact women of national minorities are predominant here (Mordva, Tachunaschi, Marejer). If in the west it is sometimes possible to mistake a young man for a girl, because of clothing and hair style, in Russia it's the opposite, as a result of their dirty work clothes, hands, way of walking, cursing and drinking" (Schwendtke, page 62).

In our opinion, these reports of the misery of the conditions of the workers in the ‘socialist countries' tend if anything to underestimate the situation. For instance, the figures on the working day given above ignore the constant rise in compulsory -- often unpaid -- overtime. In 1970, workers in the Warski Docks in Sczcecin said they had to do over 80 hours of overtime a month (see ‘Rote Fahne uber Polen'). And even if standards of living are much lower in the USSR, especially its Asiatic parts, than in eastern Europe, the benefits of permanent austerity have not bypassed the workers of the satellite countries either:

"A study of the revolution and its causes published clandestinely in Hungary at the beginning of 1957 under the pseudonym Hungaricus, draws an official Hungarian statistics to argue that the level of real wages had fallen some 20% during the years of socialist construction from 1949 to 1953. The average monthly workers' wage was less than the price of a new suit, while the daily pay of a worker on a state farm was insufficient to buy one kilo of meat. Indeed, the Hungaricus pamphlet contends only 15% of Hungarian families lived above the regime's own declared ‘minimum standard of living', with 30% attaining it and 55% living below it. This meant that in15% of working class families, not every member had a blanket to sleep under, and 20% of workers didn't even have a winter coat. It was these sans-manteaux, Hungaricus suggests, who were to provide the front-line troops to be found attacking the Soviet tanks in October 1956" (Lomax, ‘The Working Class in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956'). You don't have to look any further for the principal cause of the 1953-56 wave of class struggle!

With regard to the famous ‘abolition of unemployment' in the Russian Bloc, we quote from the oppositional Osteuropa No. 4, ‘Unterboschaftigung and Arbeitslosigkeit in der Sowjetunion':

"With the beginning of the Stalinist 5 Year Plans, the Labor Exchanges were closed. Those who wanted work were sent to the socialist construction sites in the most far flung regions... Through declaring the abolition of unemployment, and ceasing the payment of unemployment benefits, the government condemned millions to misery and hunger. Stalin also made use of concentration camps in his ‘conquest of unemployment', which siphoned off the surplus labor power in the most populous regions. According to the calculations of the expert of the BBC, Pospelowski, 2% to 3% of the working population was unemployed in the 1960's, that means 3 to 4 million people. Not included in these figures are school leavers, people who for technological reasons are idle waiting for work, the only partially employed seasonal Kolkhotz chosen-peasants and workers on the Sowchosen. Taken as a percentage of the population, that amounts to more unemployed then in West Germany during the 1967-69 recession, and in absolute figures more unemployed than in the post war years in the USA. Pospelowski adds that this is the total figure for the long term unemployed according to figures for 1957. He considers that, when we include the temporary unemployed... a total of 5% of the working population would be unemployed... since then, the number of long-term unemployed has increased considerably".

It is a true reflection of the anarchy of the capitalist mode of production that unemployment should be a major problem in countries where the bourgeoisie has to compensate for a lower organic composition of capital and a lower technological level through increased use of labor power, so that unemployment grows alongside an increase in the shortage of labor. Since 1967 employment offices have been reopened in all the big Russian cities. They send the unemployed to the extreme north and the Far East. As a result of ‘rationalizations' in the Russian economy during the 5 Year Plan 1971-75, 20 million workers were fired from their jobs. In addition there are over 10 million seasonal workers. Since the beginning of the 70's, the work camps and ‘Pioneer colonies' of Siberia have become once more an important outlet for the unemployment explosion and for the flight from the land.

Despite the discreet silence of the pro-Russian Left in the west, the existence of unemployment in the east has been an open secret there for years. We will mention as an example a reader's letter to the Russian teachers' newspaper Utschitelskaja Gazeta, published on the 18.1.1965:

"How can one reconcile oneself to such disgraceful circumstances, when in a middle-sized city there are still young people who have neither worked nor gone to school for years now. Left to themselves, they lounge around on the streets for years on end, pick pocketing, selling things, and getting drunk at the railway stations." (Schwendtke, 75). In addition to direct unemployment -- the Polish government is threatening to lay off over 2 million workers presently -- industry is plagued by stoppages due to lack of fuel supplies, spare parts, raw materials or repair services. In 1979 the KOR claimed that up to a third of Polish industry was lying idle at any given time for such reasons. The figure would certainly be higher today. For workers on piece rates this means a further drastic drop in take-home pay. Industry is also racked by astronomically high turnover rates, as starving workers search desperately for a better deal. Today, the Russian bourgeoisie is forced to allow workers to change jobs twice a year, in order to avoid social explosions.

"The turnover of labor is the main plague of the soviet economic system. The loss of work hours due to turnover in the Soviet Union is much greater than in the USA as a result of strikes. For example, in the factory where I was working, with a staff of 560 people, more than 500 employees left during the year 1973" (Nikolai Dragosch, founder of the ‘Democratic Unification of the USSR', ‘Wir Mussen die Angst Uberwinden').

In the face of the immediate need to survive, workers live through pillaging the factories they work in. These actions are an expression of the extreme atomization of the class outside periods of struggle, but they also reveal the absence of any identification with the profits of ‘their' company or with the fulfilling of the 5 Year Plans.

"The automobile plant in Gorki maintains at its own cost a criminality-department of the militia, consisting of about 40 persons, who in daily controls confiscate about 20,000 roubles worth of tools and spare parts from workers. The desperation of' workers goes so far, that they cut up the bodies of Volga cars into several pieces with a torch, fling them over the fence, weld them together again, and sell them." (Schwendtke, 69)

And these are the words of a foreman at the Obuda shipyards in Budapest: "They say copper is needed for the ships destined for the Soviet Union? Plated sheets will be good enough for them! The copper will be sold to the small foundries." (Quoted in Lomax, 32)

In the face of the naked realities of permanent economic crisis, police control and open repression have long been the main means of keeping the proletariat in check. In the following pages we will see how little state terror has succeeded in paralyzing a proletariat driven to revolt by a deteriorating social situation, a growing scarcity of consumer goods, soaring prices, especially on the black markets, speed-ups in the factories, the collapse of social services, the most severe housing shortage since 1945, constant humiliation at the hands of the cops and the administration. The workers have begun to question every aspect of capitalist control, from the unions and the police to the vodka bottle.

The upsurge of the class struggle in the USSR

"The editors estimate that until the middle of the ‘70's, of the spontaneous actions of the workers, not more than 10% have become known publically, or to people in the west." (Schwendtke, 148). Holubenko comments in the same vein "... samizdat has yielded little on the question of working class opposition. Samizdat, which now reaches the west in well over 1,000 items a year, is written mostly by ‘liberal' or right wing intelligentsia, and reflects the concerns of that intelligentsia." (Holubenko, 4)

But the problem goes much further than that. The western espionage services are extremely well informed of what the working class in the Russian bloc is doing, as are of course the broadcasting services transmitting toward the east (Radio Liberty, BBC, Deutsche Welle etc) who collaborate closely with the former. What we are dealing with here is a massive black-out on news of the class struggle on the part of the ‘free world'. This censorship concerns first of all the information given to the workers in the east, in order to lessen the danger of generalization. One of the best known examples of this is the decision of Radio Free Europe in Munich to refuse to broadcast a series of letters sent by the striking Rumanian miners in 1977, who wanted to use the radio station in order to inform other Rumanian and eastern European workers of their actions. Secondly it concerns the information allowed to pass through to the workers in the west. For example the Russian strikes in Kaliningrad, Lwow and several cities in Byelorrussia which broke out in solidarity with the Polish upsurge of 1970, are well known in Poland itself, but were reported in the west only in 1974, and even then via the Hsinhua Press Service, Peking (9.1.74).

The western bourgeoisie has good reason to collaborate with its Russian counterpart in shrouding the activities of the workers, especially in the USSR, in silence. The workers in the west would hardly continue to believe that ‘the Russians' are about to invade ‘us' over here if they knew that the Russian proletariat is engaged in almost permanent struggle with its ‘own' bourgeoisie. On the other hand it would give the world proletariat a greater feeling of force and unity to know that one of its strongest detachments had returned to the path of the class war. In part 1 of this article we dealt with the revival of the class struggle in the USSR in the ‘50's and into the ‘60's. In part 1, written in November 1980, and dealing with the strike wave of the early ‘60's -- with its culmination point in Novocherkassk 1962 -- we commented -- erroneously, it appears -- on the absence of strike committees or other means of organizing and coordinating the struggle beyond the first spontaneous outbursts. One account tells how: "The insurgents in the Donbas region reportedly considered the demonstrations in Novocherkassk unsuccessful because they rebelled there without the consent of the strike organization offices in Rostov, Lugansk, Tagonrog and other cities. This would confirm rumors and reports concerning a headquarters for organized opposition in the Donbas." (Cornelia Gerstenmaier , ‘Voices of the Silent').

The strike wave of 1962 was provoked by the announcement of price increases on meat and dairy products. "Sit down strikes, mass protest demonstrations on factory premises, street demonstrations, and in several instances in many parts of the Soviet Union, large scale rioting occurred. Evidence at hand speaks of such occurrences at Grosny, Krasnodar, Donetsk, Yaroslav, Zhdanov, Gorki and even Moscow itself, inhere reportedly a mass meeting took place at the Moskvich Automobile Factory." (Holubenko, 12) Holubenko, basing himself on the reports of a Canadian Stalinist called Kolasky, who spent two years in the USSR, also mentions a strike of port workers in Odessa against food shortages, and a strike at the motorcycle factory in Kiev. Chauviers' text (‘The Working Class and the Unions in Soviet Companies') talks of a strike in Vladivostok against food shortages, which led to a bloody rising.

Until 1969 relative quiet returned to the strike front. The new Brezhnev-Kosygin leadership began by being more compromising over wages. Since 1969, however, wages have been steadily below the level even of the Khrushchev era. Already warned by the big strikes in the Donez Basin and in Charkov in 1967, the government decided to phase in the necessary price increases. Also, the forces of repression were strengthened in advance.

"Since 1965, and especially since 1967, many new organizations have been established to reinforce the police and special agent departments. The power of the police has widened, the number of policemen greatly increased and professional security officers, night shift police stations and motorized police units set up. Furthermore, a series of new laws have been put into effect to ‘strengthen the social order in all fields of law'. Ordinances, decrees and laws such as the one passed in July 1969, which emphasized the suppression of dangerous political offenders, mass riots, and the murder of policemen, reflects a new emphasis on ‘law and order'. There is also the unprecedented promotion of' KGB security chiefs to positions in the central and republican politburos." (Holubenko, 18)

The strike wave of 1969-73 in the USSR was one of the most important if less well known elements in the international resurgence of the world proletariat in response to the re-entry of the capitalist system into open international crisis -- all over the ‘Soviet Union' workers began to come out in protest against food shortages, rising prices, and bad housing conditions. Some of the strikes of ‘69 known to us:

-- In mid-May 1969, workers at the Kiev Hydroelectric Station in the village of Beryozka met to discuss the housing problem. Many of them were still in prefabricated huts and in railway coaches despite the authorities' promise to provide housing. The workers declared that they no longer believed the local authorities, and decided to write to the central committee of the Communist Party. After their meeting the workers marched off with banners such as "All power to the Soviets" (Reddaway, ‘Uncensored Russia'). The report stems from the clandestine oppositional journal Chronicle of Recent Events.

-- A strike movement broke out in Sverdlovsk against a 25% drop in wages with the introduction of the 5-day week and of new wage norms. Centered on the big rubber plant, the strike, according to Schwendtke, took on semi-insurrectional forms. The civil war militia (‘BON' and ‘MWD') had to be called off and all the demands of the workers conceded.

-- In Krasnodar, Kuban, the workers refused to go to the factories until adequate food supplies arrived in the shops.

-- In Gorki, women working at the big armaments factory "walked off the job stating that they were going to buy meat and would not return to work until they had bought enough of it" (Holubenko, 16).

-- In 1970 a strike movement broke out involving several factories in Vladimir.

-- In 1971, in the largest equipment factory of the USSR, the Kirov plant in Kopeyske, the strike ended with the arrest of strike militants by the KGB.

"The most important disturbances in this period took place in Dnipropetrovsk and Dniprodzerzhinsk in the heavy industrial region of Southern Ukraine. In September 1972, in Dnipropetrovsk, thousands of workers went on strike, demanding higher wages and a general improvement in the standard of living. The strikes involved more than one factory and were repressed at the cost of many dead and wounded. However, a month later in October 1972, riots broke out again in the same city. The demands: better provisioning, improvement in living conditions, and the right to choose a job instead of having it imposed... Fortunately, because of the existence of a recent samizdat document, a good deal more information is available on the riots which occurred in Dniprodzerzhinsk, a city of 270, 000, several kilometers from Dnipropetrovsk. Specifically, the militia arrested a few drunken members of a wedding party, loaded them into a police wagon, and drove off. Minutes later, the police wagon crashed, and the militia (who themselves had been drinking) concentrated on saving themselves, leaving the arrested to burn to death in the wagon, which exploded. The assembled crowd marched in fury to the city's central militia building and ransacked it, burning police files and causing other damage. The crowd then marched to the party headquarters where the person ‘on duty' ordered the crowd with threats to disperse immediately. The crowd surged forward and attacked the party headquarters, whereupon two militia battalions opened fire. There were ten dead, including militia killed by the crowd. The riot is an example of the strained social relations in the Soviet Union -- an example of how an apparently small incident can spark off a major event which far surpasses the importance of the incident itself." (Holubenko, the Samizdat source is Ukrain'ske Slovo. The Ukranian Donbas has long been a centre of proletarian resistance, and already participated in the 1956 wave of struggles which shook Eastern Europe. The ‘56 wave in the Donbas is mentioned by Holubenko, as well as by the ‘Czechoslovakian Socialist Opposition' in its publication in West Germany, Listy Blatter, September 1976. Listy also mentions "mass demonstrations of the proletariat in Krasnodar, Naltschyk, KrivyjRik" and the popular rising in Tashkent in 1968).

For the year 1973, the end-point of the second postwar strike wave in the USSR, we can mention the following important actions:

-- A strike in the largest factory in Vytebsk against a 20% drop in wages. The KGB tried unsuccessfully to track down the ‘Ringleaders'

"In May 1973, thousands of workers at the machine building factory on the busy Brest Litovsk Chausee in Kiev went on strike at 11.00 demanding higher pay. The factory director immediately telephoned the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Ukraine. By 15.00 the workers were informed that their salaries were to be increased, and most of the top administrators of the factory were dismissed. It is important that the local population, according to this report, attributed the success of this strike to the fact that it had an organized character and that the regime was afraid that this strike might develop into a ‘Ukrainian Szczecin'." (Holubenko, source: Sucharnist, Munich.)

-- The popular rising in Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1973, which led to street fighting and the erection of barricades, and which was bloodily suppressed (mentioned by Listy). This explosion, of popular rage, provoked by the worsening economic situation and by increased police repression, had heavy nationalist undertones. A similar revolt took place in Tiflis, Georgia, on May 1st 1974, developing out of the official May Day Demonstration.

-- Finally, in the winter of 1973, the strike wave reached the western metropoles of Moscow and Leningrad, with scores of stoppages on construction sites being reported.

Polish interlude 1970-76

The reappearance of the proletarian fight in the 1970's was international in its dimensions. But it was not yet generalized. In the USSR, the struggles were numerous and violent, but they remained isolated and often unorganized. They took place mostly outside the industrial centers of the Russian USSR. This is not to say that great masses of workers were not involved. There are tremendous concentrations of the proletariat especially in parts of the Ukraine and western Siberia. But these workers are more isolated from each other and from the main concentrations of the world proletariat. Even more important, these struggles can be limited through the use of national, regional, and linguistic mystifications (the ‘Soviet' proletariat speaks over 100 languages), which present the fight as being against ‘the Russians'. Through assuring more favorable supplies of foodstuffs and consumer goods on the one hand, and through a formidable array of the forces of repression on the other, the state has been able to maintain its social control in Moscow and in Leningrad, where the proletariat has been more decimated by the defeat of the revolutionary wave of the twenties, and by the resulting war and state terror, than anywhere else in the world. This control over the Russian USSR is decisive.

In the 1970's, Poland became the main centre within the Russian bloc of the worldwide resurgence of the class struggle. The proletariat in Hungary and East Germany was still reeling under the double defeats of the ‘20's and ‘50's. The Czechoslovakian workers had, in addition, to recover from the heavy blow of the ‘68-69 defeat as well. These are precisely the most important countries of the bloc for the perspective of the unfolding of the world revolution, being highly industrialized, with significant concentrations of workers rich in the traditions of struggle, and bordering as they do onto the industrial heartlands of Western Europe, most significantly West Germany.

As for Poland, which once belonged to the ‘agricultural belt' along with Rumania and Bulgaria, but which underwent an important industrialization after the war, its historical role consists in becoming a revolutionary transmission belt between the front line industrialized countries of the bloc to its west, and the USSR to its east. Because the workers of eastern and central Europe had to bear the main brunt of the counter-revolution from the ‘20's to the ‘50's, the response of the proletariat there to the reappearance of open world-wide capitalist crisis has been more hesitant and uneven than in the west. As a result, the Polish transmission belt appeared long before the unfolding of mass struggles to the east or to the west which it could link to one another. This is the real basis of all the illusions about Polish exceptionalism -- or the notion that Poland is the centre of the world -- which, however much they hate capitalism and its state, will continue to tie the workers there to national ‘solutions', to the Polish national capital, until mass struggles erupt elsewhere.

Nevertheless, the Polish workers were not alone in this period, either world-wide or in the east. We have already mentioned the Russian solidarity strike with the Polish revolt of 1970. This explosion in turn was preceded by an important strike of the Rumanian miners, and the big strike wave in the USSR, which began 18 months earlier. The bourgeoisie of the whole bloc was shocked by the upsurge.

"Everywhere, the Five Year Plans were altered in favor of the supply of consumer goods and foodstuffs. In Bulgaria, price rises previously planned for 1.1. 71 were withdrawn, in the USSR in March great fuss was made over the sinking of certain prices. In the GDR the events in Poland accelerated the outbreak of a latent political crisis which left its mark in the replacement of Walter Ulbricht by Honecker. The SED lowered the prices for textiles and other industrial goods, after there had been unrest over hidden price rises, and raised pensions." (Koenen and Kuhn, Freiheit, Unabhangigkeit und Brot.)

In November 1972, with the two year price freeze in Poland forced on Gierek by the workers from Lodz in February 1971 about to run out, the dockers of Gdansk and Szczecin struck, just as the trade union congress was assembling in Warsaw to argue against the prolongation of the price freeze. Gierek flew to Gdansk to pacify the workers. In his absence the textile workers in Lodz and the miners in Katowice came out. President Jaroszewicz had to appear on TV to announce the continuation of the price freeze (See Green in Die Internationale 13, p26). The workers were defending their living standards without hesitation. In the Baltic shipyards in 1974 for example, a new productivity deal provoked a massive protest strike. Reports of similar incidents came in from many parts of the country. By March 1975 there was no meat left in the shops. In order to forestall a proletarian explosion, the meat reserves of the army were rushed to the Baltic ports and to the Silesian mine-fields. Instead, the textile workers in Lodz went on strike. There were hunger riots in Warsaw. In Radom, the munitions workers forced the release of 150 women who had been arrested after going on strike. (Reported in Der Spiegel, 13/3/75).

In June 1976 an attempt was made to raise food prices by up to 60%. The reaction was immediate. In Radom, a demonstration of the munitions workers called out the workers of the whole city. The party headquarters were burnt out, and 7 workers were killed in barricade fighting. There followed a wave of repression: 2000 workers were arrested. At the same time, in the massive tractor factory at Ursus near Warsaw, 15,000 downed tools and blocked off the Moscow to Paris railway line, taking the international express hostage. The police arrested 600 workers, and 1000 more were sacked immediately. In Plock the workers marched to the party headquarters, singing the Internationale, and to the army barracks to fraternize with the soldiers there. Here again, over 100 workers were arrested, This use of massive repression in secondary industrial centers couldn't halt the movement, because the dockers on the Baltic, the automobile workers of Warsaw, workers in Lodz, Poznan etc were coming out. It seemed like it would only be a matter of hours before they would be joined by the Silesian miners. Gierek was forced to withdraw the price rises immediately. But this concession was followed by a wave of mass arrests, torturings, and police atrocities. The price rises were enforced more slowly, less obviously, but just as surely. In the face of this vicious bourgeois counter-attack, and in view of the fact that their living standards were deteriorating despite even the most resolute struggles, the proletariat in Poland entered a period of retreat and reflection.

The period ‘76-80 was one of relative quiet on the Polish strike front. For those who only look at the surface of events it could have seemed like a period of defeat. But the deepening of the class struggle internationally, the slow but sure maturation of the second world-wide wave of proletarian resistance since 1968, which already in the period ‘76-81 has reached a qualitatively higher level, would soon reveal the ripening of the conditions for a future revolutionary wave going on below the surface.

Krespel

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Critique of Pannekoek’s Lenin as Philosopher by Internationalisme, 1948 (part 3)

- 3431 reads

III

"....The Russian Revolution reserves a chair in ancient history for Kautsky...." and in Philosophy for Harper.

Following the various criticisms we made of Harper's philosophy, we now want to show that the political standpoint that he derives from his philosophy in actual practice takes him away from revolutionary positions (our initial aim was not to make a profound philosophical study, but simply to show that while all of Harper's criticisms of so-called mechanistic materialism are based on a correct, if somewhat schematic, exposition of the problem of human knowledge and praxis, their practical political application leads him into vulgar mechanistic standpoint as well) ,

For Harper

1) The Russian revolution, in its philosophical manifestations (the critique of idealism) was entirely an expression of bourgeois materialist thought ... thoroughly conditioned by the necessities of the Russian milieu.

2) Russia, from an economic point of view colonized by foreign capital, needed to ally itself with the revolution of the proletariat. Therefore, Harper adds,

"Lenin...had to rely on the working class, and because his fight had to be implacable and radical, he espoused the most radical ideology of the Western proletariat fighting world-capitalism, viz Marxism. Since, however, the Russian revolution showed a mixture of two characters, middle-class revolution in its immediate aims, proletarian revolution in its active forces, the appropriate bolshevist theory too had to present two characters, middle-class materialism in its basic philosophy, proletarian evolutionism in its doctrine of class fight." (Lenin as Philosopher, Merlin Press, p.96)

And from there Harper goes on to characterize the conceptions of Lenin and his friends as a typically Russian form of Marxism except, perhaps, for Plekhanov, whom Harper sees as the most western kind of Marxist, though by no means completely free of bourgeois materialism.

If it is really possible for a bourgeois movement to rely on "a revolutionary movement of the proletariat fighting world capitalism" (Harper), and if the result of this fight has been the establishment of a bureaucracy as a ruling class that has stolen the fruits of the international proletarian revolution, then the door is open to the conclusion reached by James Burnham.

According to Burnham, the techno-bureaucracy has established its power in a struggle against the old capitalist form of society, and it has done this by relying on a working class movement. From this point of view, socialism is just a utopia.

It's no accident that Harper's conclusions are the same as Burnham's. The only difference is that Harper ‘believes' in socialism whereas Burnham ‘believes' that socialism is a utopia[1]. But they both share the same critical method, one which is quite foreign to the revolutionary method.

Harper -- who joined the Communist International, who formed the Dutch Communist Party, who participated in the CI in the crucial years of the revolution, who helped mobilize the proletariat of Europe in the defense of this "counter-revolutionary Russian state" -- explains himself thus:

"if it had been known at the time..." (ie. Lenin's Materialism and Empiriocriticism), "one could have predicted..." (the degeneration of the Russian revolution and of Bolshevism into a state capitalism supporting itself on the working class).

We can reply to Harper that a number of ‘enlightened' Marxists did predict this, and arrived at the same conclusions as Harper about the Russian revolution well before he did. We can, for example, cite the case of Karl Kautsky.

Karl Kautsky's position on the Russian revolution was given a broad public through the extensive debate that took place between him, Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg (1915-1918, Lenin: Against the Stream; Socialism and War; Imperialism the Highest Stage of Capitalism; State and Revolution; The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky. Kautsky: The Dictatorship of the Proletariat. 1921, Luxemburg: The Russian Revolution. 1922, Kautsky: Rosa Luxemburg and Bolshevism).

From the series of articles by Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg and Bolshevism, published in Belgium, in French in 1922, one can see how similar Kautsky's conclusions are to those of Harper.

"...And this book (Luxemburg's Russian Revolution) puts us (Kautsky) in the paradoxical position of being compelled to defend the Bolsheviks against more than one of Rosa Luxemburg's accusations". (Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg and Bolshevism).

What Kautsky does is to defend the ‘errors' of the Bolsheviks (which Luxemburg criticizes in her pamphlet) by portraying them as logical consequences of the bourgeois revolution in Russia; by showing that the Bolsheviks could only carry out what the Russian milieu destined them to, namely, the bourgeois revolution.

To give a few examples: Rosa criticized the Bolshevik slogans and policies concerning the dividing up of the land by the small peasants. She felt that this would lead to all sorts of difficulties and advocated the immediate collectivization of land. Lenin had already responded to such arguments when Kautsky made them from a different starting point (cf. the chapter ‘Subserviency to the Bourgeoisie in the Guise of "Economic" Analysis', in The Proletarian Revolution and. the Renegade Kautsky).

Kautsky:

"...There is no doubt that this (the dividing up of the land) constitutes a powerful obstacle to the progress of socialism in Russia. But this was something that was impossible to prevent: one can only say that it could have been carried out in a more rational manner than the Bolsheviks did it. This is precisely the proof that Russia is essentially at the stage of the bourgeois revolution. This is why the Bolsheviks' bourgeois agrarian reforms will outlive the Bolsheviks, whereas they themselves have had to recognize that the socialist measures they took are incapable of lasting and have in fact been prejudicial..."

Of course, Kautsky's mighty arguments were totally invalidated by that other ‘socialist' Stalin, who collectivized the land and ‘socialized' industry when the revolution had already been strangled to death.

And here is along sample of Kautsky's views on the development of Marxism in Russia. It is strangely reminiscent of Harper's dialectic (see ‘The Russian Revolution' chapter in Lenin As Philosopher).

"...As with the French, the Russian revolutionaries inherited from the reactionaries this belief in the exemplary importance of their nation over the other nations...

"...When Marxism reached Russia from the decaying west, it had to fight very energetically against this illusion, and demonstrate that the social revolution could only come out of a highly developed capitalism. The revolution that Russia was heading towards would necessarily be, first of all, a bourgeois revolution on the model of the ones that had taken place in the west, But as time went by, this conception seemed restrictive and paralyzing to the more impatient Marxist elements, especially after 1905, when the Russian proletariat fought so triumphantly and stirred the enthusiasm of the whole European proletariat. From then on, the most radical Russian Marxists developed a particular nuance of Marxism. That part of Marxism which made socialism depend on economic conditions, on the advanced development of industrial capitalism, more and more faded away from their eyes. Now Marxism as a theory of the class struggle was increasingly emphasized, Moreover, it was seen simply in terms of the struggle for political power by any means, divorced from its material base. With this way of approaching the question, the Russian proletariat ended up being seen as an extraordinary being, the model for the proletariat of the entire world. And the proletarians of other countries began to believe it -- to praise the Russian proletariat as the guide for the whole international proletariat in the struggle for socialism. It's not difficult to explain this. The west had the bourgeois revolutions behind it and the proletarian revolutions in front of it. But the latter required a strength which hadn't yet been achieved anywhere. Thus, in the west, we find ourselves in an intermediate stage between two revolutionary epochs, and this puts the patience of the advanced elements to a hard test.

"Russia, on the other hand, was so backward that it still had the bourgeois revolution and the overthrow of absolutism in front of it.

"This task didn't require the proletariat to be as strong as it would have to be to carry out the exclusive conquest of working class power in the west. Thus the Russian revolution took place sooner that the revolution in the west. It was essentially a bourgeois revolution, but this didn't become clear for some time, because the bourgeois classes in Russia today were much weaker that they were in France at the end of the 18th century. If one neglected the economic base, if one looked only at the class struggle and the relative strength of the proletariat, it could for a time really seem as though the Russian proletariat was superior to the proletariat of western Europe and was determined to be its guide..." (Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg and Bolshevism).

In a more philosophical way, Harper reiterates Kautsky's arguments one by one.

Kautsky puts forward two opposing conceptions of socialism:

1) In the first, socialism can only be realized on the basis of advanced capitalism (Kautsky's position, and that of the Mensheviks. This position was also used by the German social democrats, including Noske, in order to criticize the Russian revolution. It's a conception which in fact led to the adoption of state capitalist measures, supported by a ‘part of the masses', against the revolutionary proletariat).

2) In the second, "the struggle for political power, by any means, divorced from its economic base", would allow socialism to be built even in Russia (this is Kautsky's version of the Bolsheviks' position).

In fact, Lenin and Trotsky said: the bourgeois revolution in Russia can only be made through the insurrection of the proletariat. Since the insurrection of the proletariat has an objective tendency to develop on an international scale, we can, given the level of the development of the productive forces on a world scale, hope that this Russian insurrection will provoke a world-wide movement.

From the point of view of the development of the productive forces in Russia alone, the Russian revolution would be a bourgeois one; but the realization of socialism was possible if the revolution broke out on a world scale. Lenin and Trotsky, as well as Rosa Luxemburg, thought that the level of development of the productive forces on a world scale not only made socialism possible -- they made it a necessity. They all agreed that capitalism had reached its epoch of "(world) wars and revolutions". They only disagreed about the economic causes of this situation. For socialism to be possible, the Russian revolution could not remain isolated.

Alongside the Mensheviks, Kautsky replied that Lenin and Trotsky saw the revolution as a ‘voluntarist' affair, the mere seizure of power through a Bolshevik putsch. They even compared Bolshevism with Blanquism.

All these ‘enlightened' Marxists and socialists are precisely the ones Harper seems to cite as an example, as those who ‘issued Marxist warnings', who were against ‘the international workers' movement being led by the Russians' -- people like Kautsky:

"...that Lenin did not understand Marxism as the theory of proletarian revolution, that he did not understand capitalism, bourgeoisie, proletariat in their highest modern development was shown strikingly when from Russia, by means of the Third International, the world revolution was to be started, and the advice and warnings of Western Marxists were entirely disregarded" (Lenin As Philosopher, p.98).

All of them with Kautsky to the fore reproach Bolsheviks for not taking into account the backward state of the economy. In reality, from1905 onwards, Trotsky had a masterful response to all these "honest family heads" as Lenin called them. He showed how, on the one hand, the advanced level of industrial concentration in Russia, and, on the other hand, its backward social situation (the delay in the bourgeois revolution), ensured that Russia would be in a constantly revolutionary state; and this revolution would be proletarian, or it would be nothing.

Harper, building his theory and his philosophical critique on Kautsky's theory and historico-economic critique, says that owing to the backward state of the Russian economy, to the inevitability of the bourgeois revolution in Russia on the economic level, the philosophy of the Russian revolution had to carry on the first phase of Marx's thought, ie, the Feuerbachian, revolutionary bourgeois democratic phase: "religion is the opium of the people" (the critique of religion). It was thus natural that Lenin and his friends didn't attain the second phase of Marxist philosophy, the revolutionary proletarian dialectical phase: "social existence determines consciousness". (Harper forgets to point out -- even though it's impossible for him not to have known this -- that the main struggle of the Bolsheviks before 1918 was directed against all the social democratic currents to their right, both the governmental and the centrist factions; and that this battle was waged on a very broad scale, through the whole European press and pamphlets in many languages, whereas Materialism and Empiriocriticism was only known to a wider Russian public much later, was translated into German quite a bit later, into French even later still, and was very little read outside Russia. One feels justified in asking whether the spirit of Materialism and Empiriocriticism was contained in these articles and pamphlets. Harper doesn't attempt to prove this, and with good reason). Anyway, Harper, like Kautsky, concludes from all this that despite the voluntarist conception of class struggle held by Lenin and Trotsky, who wanted to "make the Russian proletariat the orchestral conductor of the world revolution..." the revolution was doomed to be philosophically bourgeois, since Lenin and his friends had adopted a Feuerbachian bourgeois materialist philosophy (Marx phase one).

These ideas bring Harper and Kautsky together in their critique of the Russian revolution -- both in their approach to the fundamentals of the problem, and in the way they both accuse the Bolsheviks of wanting to direct the world revolution from the Kremlin.

But there is more. In his philosophical expose Harper argues that Engels wasn't a dialectical materialist, that his conceptions of knowledge were still profoundly marked by the natural sciences and bourgeois materialism. To verify this theory you would have to examine the writings of Engels in detail, which. Harper doesn't do. Mondolfo, on the other hand, in an important work on dialectical materialism seems to want to demonstrate the opposite, which proves that this isn't a new quarrel. Whatever the case, I think that new generations can often observe in those who preceded them what have noted in Lenin or Engels, who - made a critique of the philosophies of their time on the basis of the same level of scientific knowledge, and were often far too schematic in their approaches. But the real point is to study their general attitude, not simply their philosophical position -- to see whether, in their general activity, they situated themselves on the terrain of praxis, of Marx's Theses on Feuerbach.

In this what Sydney Hook says about the work of Lenin in his Understanding Marx is much closer to reality:

"What is strange is that Lenin seems not to notice the incompatibility between, on the one hand, his political activism and the reciprocal dynamic philosophy of action of What Is To Be Done, and, on the other hand, the absolutely mechanistic theory of knowledge which he defends so violently in Materialism and Empirio-criticism. Here he follows Engels word for word in his statement that "sensations are the copies, the photographs, the reflection, the mirror image of things", and that mind is not an active factor in knowledge. He seems to believe that if one argues for the participation of mind as an active factor in knowledge, conditioned by the nervous system and the entire history of the past, it must follow that the mind creates everything that exists, including its own brain. That would be idealism in its most characteristic form, and idealism means religion and belief in God.

"But the passage from the first to the second proposition is the most obvious non sequitur one could imagine. In reality, in the interest of his conception of Marxism as the theory and practice of the social revolution, Lenin had to admit that consciousness is an active business, a process in which matter, culture and mind react reciprocally on each other, and that the sensations don't constitute knowledge but are a part of the material worked upon by knowledge.

"This is the position Marx takes in his Theses on Feuerbach and in The German Ideology. Whoever sees the sensations as exact copies of the external world, themselves leading to knowledge, cannot avoid fatalism and mechanism. In Lenin's political writings, rather than his technical writings, one finds no trace of this Lockean dualist epistemology. His What Is To Be Done, as we have seen, contains a frank acceptance of the active role of class knowledge in the social process. It's in his practical writings dealing with the concrete problems of agitation, revolution and reconstruction that you find the real philosophy of Lenin...." (Understanding Marx, Sydney Hook, p.57-8)[2].

The clearest testimony to what Sydney Hook says, putting Harper alongside Plekhanov and Kautsky, is something Trotsky wrote in My Life. Speaking about Plekhanov, he says, "His strength was being undermined by the very thing that was giving strength to Lenin -- the approach of the revolution ... He was Marxian propagandist and polemist-in-chief, but not a revolutionary politician of the proletariat. The nearer the shadow of the revolution crept the more evident it became that Plekhanov was losing ground..."

We can see now that what's original in Harper isn't his philosophical thesis (which is, on the contrary, a statement of position following on from many others), but above all the conclusion he draws from it.

This is a fatalistic conclusion, lust like Kautsky's. In his pamphlet Rosa Luxemburg and Bolshevism Kautsky cites a phrase written to him by Engels in a personal letter:

"...the real, and not the illusory ends of a revolution are always realized by this revolution later on".

This is what Kautsky tries to demonstrate in his pamphlet, and this is what Harper argues for (to those who want to follow him in his conclusions) in Lenin As Philosopher. Having fought against the bourgeois materialism of Lenin and Engels, he comes to the most vulgarly mechanistic conclusion about the Russian revolution, portraying it as a ‘fatal product', a ‘real and not illusory end'. The Russian revolution produced what it had to produce -- it was all inscribed in Materialism and Empiriocriticism and in the economic conditions of Russia; the world proletariat was simply used as an ideological cover for all this. What's more, Pannekoek goes on to argue that the new class in power in Russia quite naturally took up Leninism's mode of thinking, its bourgeois materialism, in their struggle against the established bourgeois strata, who on the philosophical level had fallen back into religious cretinism, mysticism and idealism, and had become conservative and reactionary. This new, fresh philosophy, this new state capitalist class of intellectuals and technicians, find their raison d'être in Materialism and Empiriocriticism and Stalinism, and are rising in all countries...Thus we have the equation: Marx phase one = Lenin's Materialism = Stalin!

Without knowing Harper's work, Burnham has understood this equation very well -- just as the anarchists have been repeating it for ages without understanding it. It''s obvious that Harper doesn't say this quite so brutally, but the fact that he opens the door to all Burnham's bourgeois and anarchist conclusions is enough to show the underlying flaw in Lenin As Philosopher.

Finally, when he comes to draw the ‘pure' proletarian lessons of the Russian revolution (I would point out that the language of Harper and Kautsky always talks about the ‘Russian revolution' and not the ‘October revolution', which is quite a significant distinction), Harper separates the action of the Russian working class from the ‘bourgeois' influence of the Bolsheviks, and ends up saying that it is the generalized strikes and soviets (or councils) ‘in themselves' which produced the Russian revolution and which bring us the following positive lessons:

1) the proletariat must detach itself ideologically from bourgeois influence ‘man by man'

2) it must gradually learn, on its own, how to manage the factories and organize production

3) generalized strikes and the councils are the exclusive weapons of the proletariat.

This conclusion is a refined type of reformism, and what's more, is totally anti-dialectical.

Even if it were realizable, this ‘man by man' detachment from bourgeois ideology would postpone socialism for centuries. It turns the Marxist doctrine into a beautiful fairytale for the childish workers, to give them the courage to face up to life. If every man had to be detached from the ruling ideology of bourgeois society on an individual basis, then Marxism becomes no more than an idea -- an eternally valid idea, but no more. In reality, it's the working class as a whole which detaches itself in certain historic conditions, when it's thrown with particular violence against the old system. Socialism can't be realized ‘man by man', as the old reformists used to believe, arguing that you had first to reform men before you could reform society. In fact the two can't be separated: society changes when humanity enters into movement not ‘man by man', but ‘as one man', when it finds itself in particular historic conditions.

The fact that Harper repeats the old reformist refrains in a seemingly new form, allows him, under a philosophical-dialectical verbiage to gloss over the real problems of the Russian revolution, to dismiss its fundamental contributions as no more than reasons of the Russian state. We refer to Lenin's position against the war and Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution.

Oh yes, Messrs. Kautsky and Harper, you may sometimes hit the mark in a purely negative critique of the philosophical or economic theories of Lenin and Trotsky, but that in no way means that you have reached a revolutionary position. In their political positions during the crucial, insurrectionary phase of the Russian revolution, it was Lenin and Trotsky who were the true Marxist revolutionaries.

It's not enough, twenty years after the battle, and having yourself participated in the front line, to philosophically conclude that all this had to end up in the Stalinist state. You also have to ask how and why Lenin and Trotsky could base themselves on the international workers' movement, and prove to us that Stalinism was the inevitable product of this movement.

Harper, just like Kautsky, is incapable of answering these questions, because in their political positions, in the face of the bourgeoisie, in an imperialist war, or a phase of revolution, they lack the concepts that would allow them to approach these problems. They may know Lenin ‘as philosopher' or as a ‘head of state', but they don't know Lenin as a revolutionary Marxist, the real face of Lenin, when he fought against the imperialist war, or the real face of Trotsky, when he fought against the mechanistic concept of an ‘inevitable' capitalist development for Russia. They don't know the real face of October, which aren't just the mass strikes or the soviets. Lenin wasn't attached to the soviets in an absolute way, as Harper is, because he believed that the forms of proletarian power emerged spontaneously out of the struggle. In that I think that Lenin was also more Marxist, because he wasn't attached to soviets, unions, or parliamentarian ism (even if he was mistaken) in a definitive manner, but according to whether they were appropriate to the class struggle at a given time.

On the other hand, Harper's quasi-theological attachment to the councils now leads him to a position of advocating a form of workers' co-management under capitalism, as a kind of apprenticeship in socialism. But it's not the role of revolutionaries to advocate this kind of apprenticeship. Together with the ‘man by man' theory of socialism, this kind of apprenticeship would condemn humanity to eternal slavery and alienation, with or without councils, with or without ‘council communists' and their schemes for apprentice ship under the capitalist regime -- a vulgar reformist-conception which is simply the other side of Kautskyian coin.

As for the ‘struggle of the workers themselves', with its ‘appropriate' means -- strikes, etc -- we have seen the results. It comes close to the ‘strike-cultivating' theories of the Trotskyists and anarchists, with their latter-day versions of the old ‘trade unionist' and ‘economist' traditions which Lenin attacked so violently in What Is To Be Done. This means that the anti-union position of the council communists, correct in a purely negative sense, is no less false ‘in itself', because the unions are replaced by their younger brothers, the soviets, and play the same role, as though the content could be changed by changing the name. One no longer calls the party the party or unions, unions, but one replaces them by the same organizations that have the same functions but a different name. If one were to call cats ‘Raminagrobis' they would still have the same anatomy and the same place in the world. But for some they would have become a myth, and it's a curious thing that there are ‘dialectical' philosophers and materialists whose point of view is so narrow that they try to convince us that their world of mythological constructions, a world in which ‘raminagrobis' have replaced cats, really is a new world.

Thus: in the old world, Kautsky was a vulgar reformist, whereas, in the new world, Trotskyists, anarchists and council communists are ‘authentic revolutionaries'. In fact they are even more grossly reformist than the great theoretician of reformism, Kautsky.

The fact that Harper takes up the classical arguments of bourgeois reformism, both Menshevik and Kautskyist (and, more recently ‘Burnhamite'), against the Russian revolution, should not surprise us too much. Instead of trying to draw the real lessons of the revolutionary epoch as a Marxist would (and as Marx and Engels did, for example, with regard to the Paris Commune), Harper tries to condemn the Russian revolution ‘en bloc', as well as the Bolshevism that was linked to it (just as Blanquism and Proudhonism were linked to the Paris Commune).

If, instead of trying to condemn the Bolsheviks as being ‘appropriate to the Russian milieu', Harper had asked himself about the level of thought reached by the left of social democracy which all of us come out of, he would have reached very different conclusions in his book. He would have seen that this level of thought (even amongst those who were the most developed in dialectics) was insufficient for solving certain of the problems posed by the Russian revolution, especially the problem of party and state. On the eve of the Russian revolution, no Marxist had a very precise understanding of these problems, and for good reasons.

We insist that at all levels of knowledge -‑ philosophical, economic, and political - the Bolsheviks in 1917 were amongst the most advanced revolutionaries in the whole world, and this was to a large extent thanks to the presence of Lenin and Trotsky.

If subsequent events seem, to contradict this, it's not because their intellectual development was appropriate to the ‘Russian milieu', but because of the general level of the international workers' movement; and this poses philosophical problems which Harper hasn't even tried to raise.

Philipe

[1] ICC note: In a future issue of International Review, we will see how one of Harper's best disciples, Canne-Meyer, ended up, albeit with regret and sadness, at the same conclusion as Burnham about socialism being a utopia. Fundamentally, with a great deal more blather, this was the conclusion also reached by the Socialisme ou Barbarie group and its mentor, Chalieu-Castoriadis-Cardan.

[2] Note from the original text: Against the Harper/Kautsky thesis on a ‘specifically Russian milieu', we can cite Marx's Theses on Feuerbach: "The materialist doctrine that men are products of circumstances and upbringing, and that, therefore, changed are products of other circumstances and that the educator needs educating. Hence, this doctrine necessarily arrives at dividing society into two parts, of which one is superior to society....The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice".

Deepen:

Development of proletarian consciousness and organisation:

General and theoretical questions:

- Philosophy [6]

People:

- Lenin [7]

- Anton Pannekoek [8]

International Situation (1981)

- 2807 reads

In our press, we have often characterized the 1980s as ‘the years of truth’ (see, in particular, the International Review numbers 20 and 26). The first two years of the decade have confirmed this analysis. The years 1980‑81 have witnessed events of the greatest importance, events that are particularly significant for the stakes that will, in large part, be played out during the 1980s --imperialist war or worldwide proletarian revolution.

The illusions about the economic situation -- which determines the whole of social life -- have come brutally to an end; 1980 and 1981 appear as the years of a new recession in the world economy, with a massive growth of inflation and an unprecedented rise in unemployment.

The bourgeoisie’s response to this crisis -- worsening inter-imperialist tensions and the preparations for war -- has fully lived up to the causes that prompted it. 1980 began with the invasion of Afghanistan, while at the close of 1981 comes an intense growth in armaments throughout the world, and the opening in Geneva of new negotiations between Russia and the US over ‘disarmament’. We have already seen their role as a smoke-screen designed to conceal the headlong arms-race towards a new holocaust.

The workers’ response has also lived up to the raising of the stakes; during the summer of 1980 there took shape in Poland the mightiest movement of the world proletariat for more than half a century. A movement that every bourgeoisie spared no efforts to stifle, and which it has not yet managed to deal with. A movement which showed, at the same time, the capacity of the capitalist class for solidarity in the face of the proletarian struggle, and the necessity for this struggle to spread to the world level.

This article aims to take stock of these three fundamental elements of humanity’s destiny: the capitalist crisis, and the response of bourgeoisie and proletariat respectively.

A continuously deteriorating economic crisis

In 1969, the leader of the world’s greatest power triumphantly declared: “We have finally learned to manage a modern economy in such a way as to assure its continuous expansion”[1]. A year later, the United States entered its worst recession since the war: -0.1% growth of the Gross Domestic Product (nowhere near as bad as it was to become later) .

In 1975, Chirac, Prime Minister of the world’s fifth largest power, was taking his turn to play Nostradamus: “We can see the light at the end of the tunnel.” A year later, he was obliged to make way for ‘France’s best economist’, Professor Barre, who, on his departure in May 1981, left the situation even worse than he had found it (unemployment doubled, inflation at 14% instead of 11%).

A year ago, the American bourgeoisie chose Reagan to put an end to the crisis (at least this is what he said). But the remedies concocted by Milton Friedman, Nobel Prize for Economics, and a few other adepts of ‘supply-side economics’ have achieved nothing. The American economy is plunging into a new recession, unemployment is approaching the 10 million mark (a post-war record) , and even David Stockman, director of the budget, admits that he didn’t really believe in the success of the economic policy for which he himself was largely responsible.

As regularly as autumn follows summer and winter follows autumn, the world’s leaders have deceived both themselves and their audience in announcing “the end of the tunnel” as if in a surrealist film, the tunnel’s end has seemed to retreat more and more as the train advanced to the point where it is no more than a little speck of light, soon to disappear altogether.

But the western leaders don’t hold a monopoly on hazardous predictions.

In September 1980, Gierek was replaced by Kania at the head of the PUWP for having led the Polish economy to disaster. With Kania, things would be different! And different they were -- to the point where the economic situation of the summer of 1980 takes on an air of prosperity compared with the situation today; a fall in production of 4% has been followed by a collapse of 15%. Kania, after being triumphantly re-elected to the leadership of the party in July, disappeared into oblivion in October.

As for Brezhnev, his regularly disappointed predictions are at least as numerous as the plenary sessions of the Central Committee of the CPSU. In an outburst of lucidity, and with a certain humor that was probably unintended, Brezhnev recently finished by observing that after three consecutive years of bad harvests caused by the weather, the analysis of the Russian climate would have to be revised.

In recent years, the whole of Comecon has been marked by a chronic inability to meet the objectives of the 1976-1980 plan. While the most ‘serious’ member, East Germany, managed to raise the national income by 80% of the plan’s forecast, for Hungary this figure falls to 50%. As for Poland, its growth in relation to 1976 has been zero, which comes down to saying that it produces only 70% of what was forecast by the planners. So much for the ‘great workers’ victory’ that the planned economy is supposed to represent, according to the Trotskyists!

As for the state monopoly of foreign trade -- the other ‘great workers’ victory’ according to the Trotskyists -- it too has demonstrated its remarkable effectiveness: the countries that make up Comecon are among the most indebted in the world.

As for the myth of the absence of inflation in these countries, it has been killed off ever since the massive and repeated official price increases -- going as high as 200% (eg 170% on the price of bread in Poland) .

In 1936, Trotsky saw the economic progress of the USSR as proof of socialism’s superiority over capitalism; “There is no longer any need to argue with the bourgeois economists; socialism has shown its right to victory, not in the pages of Capital, but in an economic arena that covers a sixth of the planet; not in the language of dialectics, but in that of iron, cement and electricity”[2].

With the same logic, we would today be obliged to come to the opposite conclusion -- that capitalism is superior to socialism, so obvious is the economic weakness and fragility of the so-called ‘socialist’ countries. Moreover, this is the battle-cry of the western economists to justify their defense of the capitalist mode of production. In fact, the crisis hitting the eastern bloc is a new illustration of what revolutionaries have always said -- that there is nothing socialist about the USSR and its satellites. These are capitalist economies, and relatively under-developed ones at that.

But the cries of satisfaction coming from the defenders of private capitalism, as they point the finger of scorn at the countries of the eastern bloc are unable, though this is their purpose, to conceal the gravity of the crisis in the very heart of the citadels of world capital.

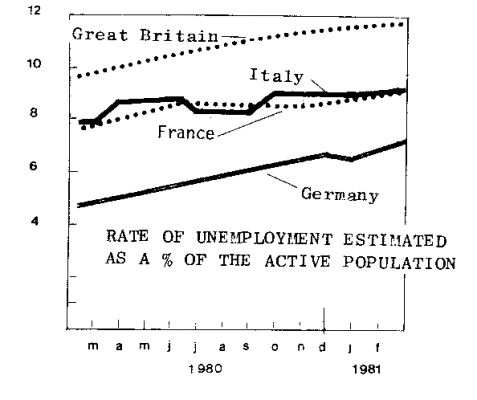

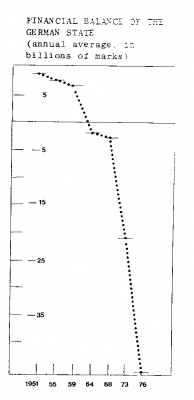

The following graphs give an idea of the development of the three main economic indicators for the whole of the OECD (ie the most developed western countries): these are inflation, the annual variation in the Gross Domestic Product and the rate of unemployment.

The yearly figures are already significant in themselves, but it is more interesting to examine the mean for a period of several years (1961-64, 1965-69, 1970-74, 1975-79, 1980-81). For the three indicators that we are considering, the figures show a constant deterioration in the situation of western capitalism.

|

AVERAGE VALUE OF THREE ECONOMIC INDICATORS (in %) |

||||

|

Period |

65-69 |

70-74 |

75-79 |

80-81 |

|

Annual variation in GNP (OECD total) |

5.1 |

3.9 |

3.1 |

1.25 |

|

Rate of unemployment (15 principal OECD countries) |

2.66 |

3.36 |

5.16 |

6.35 |

|

Annual variation in consumer prices (OECD total) |

3.7 |

7.4 |

9.3 |

11.7 |

For some people, of course, this is not yet the ‘real’ crisis, since we have not seen a massive decline in production over a long period, as was the case during the 30s: for the moment, the average rates of growth are still positive. There are two things to be said in reply to this argument: