Submitted by World Revolution on

The dramatic worsening of the world economic crisis over the summer gives us a clear indication that the capitalist system really is on its last legs. The ‘debt crisis’ has demonstrated the literal bankruptcy not only of the banks, but of entire states; and not only the states of weak economies like Greece or Portugal but key countries of the Eurozone and on top of it all, the most powerful economy in the world: the USA.

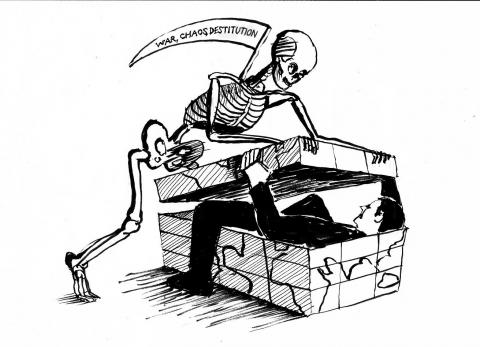

And if the crisis is global, it is also historic. The mountain of debt that has become so visible over the last few years is only the consequence of capitalism trying to postpone or hide the economic crisis which surfaced as far back as the late 1960s and early 70s. And as today’s ‘recession’ reveals its real face as a genuine depression, we should recognise that this is really the same underlying crisis as the one which paralysed production in the 1930s and tipped the world towards imperialist war. A crisis expressing the historical obsolescence of the capitalist system.

The difference between today’s depression and that of the 1930s is that capitalism today has run out of choices. In the 1930s, the ruling class was able to offer its own barbaric solution to the crisis: mobilising society for imperialist war and re-dividing the world market. This re-organisation created the conditions for launching the ‘boom’ of the 50s and 60s. This was an option at that time, partly because world war did not yet automatically imply the destruction of capitalism itself, and there was still room for new imperialist masters to emerge in the aftermath of the war. But it was an option above all because the working class in those days had tried and failed to make its revolution (after the First World War) and had been plunged into the worst defeat in its history, at the hands of Stalinism, fascism, and democracy.

Today world war is only an option in the most abstract theoretical sense. In reality, the road to a global imperialist war is obstructed by the fact that, in the wake of the collapse of the old two-bloc arrangement, capitalism today is unable to forge any stable imperialist alliances. It’s also obstructed by the absence of any unifying ideology capable of persuading the majority of the exploited in the central capitalist countries that this system is worth fighting and dying for. Both these elements are linked to something deeper: the fact that the working class today has not been defeated and is still capable of fighting for its own interests against the interests of capital.

Dangers facing the working class

Does this mean that we heading by some automatic process towards revolution? Not at all. The revolution of the working class can never be ‘automatic’ because it requires a higher level of consciousness than any past revolution in history. It is nothing less than the moment where human beings first assume control of their own production and distribution, in a society with relations of solidarity at its heart. It can therefore only be prepared by increasingly massive struggles which generate a wider and deeper class consciousness.

Since the latest phase of the crisis first raised its head in the late 60s, there have been many important struggles of the working class, from the international wave sparked off by the events of May 1968 in France to the mass strikes in Poland in 1980 and the miners’ strike in Britain in the mid-80s. And even though there was a long retreat in the class struggle during the 1990s, the last few years have shown that there is now a new generation which is becoming actively ‘indignant’ (to use the Spanish term) about the failure of the present social order to offer it any future. In the struggles in Tunisia, Egypt, Greece, Spain, Israel and elsewhere, the idea of ‘revolution’ has become a serious topic for discussion, just as it did in the streets of Paris in 1968 or Milan in 1969.

But for the moment this idea remains very confused: ‘revolution’ can easily be mistaken for the mere transfer of power from one part of the ruling class to another, as we saw most clearly in Tunisia and Egypt, and as we are now seeing in Libya. And within the recent movements, it is only a minority which sees that the struggle against the current system has to declare itself openly as a class struggle, a struggle of the proletariat against the entire ruling class.

After four decades of crisis, the working class, especially in the central countries of capitalism, no longer even has the same shape that it had in the late 60s. Many of the most important concentrations of industry and of class militancy have been dispersed to the four winds. Whole generations have been affected by permanent insecurity and the atomisation of unemployment. The most desperate layers of the working class are in danger of falling into criminality, nihilism, or religious fundamentalism.

In short, the long, cumulative decay of capitalist society can have the most profoundly negative effects on the ability of the proletariat to regain its class identity and to develop the confidence that it is capable of taking society in a new direction. And without the example of a working class struggle against capitalist exploitation, there can be many angry reactions against the unjust, oppressive, corrupt nature of the system, but they will not be able to offer a way forward. Some may take the form of rioting and looting with no direction, as we have seen in Britain over the summer. In some parts of the world legitimate rage against the rulers can even be dragged into serving the needs of one bourgeois faction or one imperialist power against another, as we are seeing in Libya.

In the most pessimistic scenario, the struggle of the exploited will be dissipated in futile and self-defeating actions and the working class as a whole will be too atomised, too divided to constitute itself into a real social force. If this happens, there will be nothing to stop capitalism from dragging us all towards the abyss, which it is perfectly capable of doing without organising a world war. But we have not yet reached that point. On the contrary, there is plenty of evidence that a new generation of proletarians is not going to let itself be pulled passively into a capitalist future of economic collapse, imperialist conflict and ecological breakdown, and that it is capable of rallying to its banners the previous generations of the working class and all those whose lives are being blighted by capital.

WR 1/9/11

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace