September

- 1539 reads

Against Morsi, against the military: for class struggle!

- 1670 reads

Against Morsi, against the military: for class struggle!

In our previous article analysing the situation in Egypt, we wrote in our conclusion:

“capitalism has accumulated the means to destroy all human life on the planet. The collapse of social life and the rule of murderous armed gangs – that’s the road of barbarism indicated by what’s happening right now in Syria. The revolt of the exploited and the oppressed, their massive struggle in defence of human dignity, of a real future – that’s the promise of the revolts in Turkey and Brazil. Egypt stands at the crossroads of these two diametrically opposed choices, and in this sense it is a symbol of the dilemma facing the whole human species”[1].

The tragic events which have taken place and accelerated during the month of August in Egypt following the reactions to the army coup against former president Morsi, in particular the bloody repression of the Muslim Brotherhood which peaked on the 14th August, bear witness to the whole gravity of this historic situation and confirm this idea of a “crossroads” for the whole of humanity.

Getting caught up in the logic of civil war

The quagmire of decomposition, of economic and social crisis, the corruption and disastrous policies of the Morsi government (elected in June 2012) led the population back to the streets to express their discontent with growing poverty and insecurity. It was this deteriorating situation, aggravated by the political irrationality and endless provocations of the Muslim Brotherhood, which pushed the Egyptian army to carry out the coup of 3 July, deposing president Morsi from office. Parallel to this, the social agitation continued, stoking up very dangerous tensions and some bloody confrontations. This was nothing less than a juggernaut heading towards civil war. The only force capable of holding society together, the army, was compelled to step in and prevent it from breaking apart. The strongman of the hour is therefore the head of the army, Abdel Fattah al-Sissi. The latter was obliged to impose a policy of brutal repression, mainly using the civil police against the Muslim Brothers and the pro-Morsi forces. Throughout the summer, there was a growing number of clashes between the pro and anti- Morsi elements, resulting in a number of deaths, particularly among the Muslim Brotherhood. The pro-Morsi demonstrations and sit-ins, which gathered together men, women and children, were dispersed in a violent manner. The army assaults left over a thousand dead. Martial law, in the shape of a state of emergency and a curfew, was imposed in Cairo and 13 provinces. A number of Muslim Brotherhood leaders and activists (over 2000) were arrested, including the ‘supreme leader’ Mohammed Badie and many others, some of whom died in prison after an escape attempt.

Since then, the demonstrations, targets for the bullets of the police and the army, have become less numerous. In maintaining order in this manner, the army and the police have won the support of the majority of the population who see the Muslim Brotherhood as terrorists. This support for the army and the state, mixed up with a growing anti-Islamist feeling, but tainted with nationalism, can only weaken the proletariat, which risks being caught up in the negative logic of the situation. This is all the more true in that the rejection of religious fundamentalism is fed by the democratic mystification which still retains a great deal of strength.

Unlike the great demonstrations in Tahrir Square which led to the downfall of Mubarak and where the political presence of women was tolerated and where they were relatively protected, the terror reigning today has led to a spectacular moral regression, such as the collective rape of women in the middle of demonstrations, and the pogrom atmosphere against the Copts (hundreds of churches have been burned and a number of Copts have been killed).

As we wrote in our previous article:

“The working class in Egypt is a much more formidable force than it is in Libya or Syria. It has a long tradition of militant struggle against the state and its official trade union tentacles, going back at least as far as the 1970s. In 2006 and 2007 massive strikes radiated out from the highly concentrated textile sector, and this experience of open defiance of the regime subsequently fed into the movement of 2011, which was marked by a strong working class imprint, both in the tendencies towards self-organisation which appeared in Tahrir Square and the neighbourhoods, and in the wave of strikes which eventually convinced the ruling class to dump Mubarak. The Egyptian working class is by no means immune from the illusions in democracy which pervade the entire social movement, but neither will it be an easy task for the different cliques of the ruling class to persuade it to abandon its own interests and drag it into the cesspit of imperialist war”.

It’s also true that there have been some new expressions of the class struggle, notably in Mahalla where 24,000 workers came out on strike after half their wages were not paid[2]. There have also been strikes in Suez. And while some demonstrators have held up banners proclaiming ‘Neither Morsi nor the military’. But these rare voices have been stifled more and more, just as the courageous struggles of the workers have been increasingly isolated and thus weakened. While the situation has not reached the tragic level it has in Syria, it is becoming more and more difficult to break out of the deadly logic leading towards such barbaric outcomes.

The threat of violent chaos and instability in the region

The internal instability that has been aggravated by recent events is not taking shape in a secondary country of the region. Egypt is a turning point between North Africa and the Middle East, between Africa and Asia. It is the most populous country of the Muslim world and Africa and its capital, Cairo, the biggest metropolis of the continent. The country is part of a Sunni arc opposed to the Shiite countries, notably Syria-Lebanon and Iran, the sworn enemy of the US and Israel in the region. From the geographical point of view Egypt therefore occupies a major strategic position, in particular with regard to the interests of the USA, the world’s leading, but declining, imperialist power. During the Cold War, Egypt was an essential pawn guaranteeing the stability of the region to the benefit of the US. This advantage was consolidated with the Camp David Accords of 1979, sealing the rapprochement between Egypt and Israel and the US. The relative stability linked to the balance between the rival military blocs of east and west made it possible contain and tolerate the Muslim Brotherhood even though they were kept under constant state surveillance – in the epoch of Nasser they had been banned outright. Today the disappearance of the bloc discipline and the development of every man for himself, of social decomposition, is accentuating centrifugal tendencies and especially the rise of radicalised factions like the Salafists and the Muslim Brotherhood, which Mubarak had already seen as a ‘state with the state’[3].

The international context, above all the free for all between the big global powers, is now serving to exacerbate all these inherent tensions. In the Middle East itself, the growing cleavage between Qatar and Saudi Arabia on the one hand, which are close to the US despite their extreme Wahabite ideology, and Egypt on the other, is pouring oil on the fire. This is why the US can’t draw back from financing the Egyptian army (to the tune of at least 80%), even though it can see that the situation is getting more and more out of its control.

Capitalism has nothing to offer but poverty and chaos. Whatever bourgeois gang is in power, the situation of the mass of the population can only get worse. But contrary to what the bourgeoisie and its media would have us believe – that the failure in Egypt is indubitable proof that any uprising can only end up in religious obscurantism or in dictatorship - the historic perspective of the proletarian revolution, even if it’s not an immediate one, is the one and only alternative to barbarism. It is the responsibility of the proletariat to become aware of this and to express its class solidarity in order to offer a real perspective for all the struggles going on in the world. Only the decisive intervention of the world proletariat, above all its most experienced fractions in the old European industrial centres, can open the road to the future – world revolution

WH 28/8/13

[1] https://en.internationalism.org/worldrevolution/201307/8946/egypt-highlights-alternative-socialism-or-barbarism [1]

[2] https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/79967/Business/Economy/Egypts-Mahalla-textile-workers-onstrike-again.aspx [2]

[3] The Muslim Brotherhood, constituted by Hasan al Banna in Egypt in 1928, quickly implanted itself in a number of Arab countries. It had a retrograde, traditionalist ideology, based on the project of a grand Sunni Caliphate, the logic of which came up against all the countries which had already been formed as national entities. See https://en.internationalism.org/ir/109_islam.html [3]

Geographical:

- Egypt [4]

Recent and ongoing:

- Egypt [5]

Rubric:

Book Review - The Alternative to Capitalism

- 2364 reads

The alternative to capitalism is published by Theory and Practice [6] whose website contains a broad range of texts from political currents such as the SPGB, left communism and situationism. The book contains essays by Adam Buick and John Crump which were first published in 1986 and 1987. It’s not presented as an official publication of the SPGB, although the book was sent to us for review by comrades who are members of the organisation. In any case, while Adam Buick is a longstanding member, John Crump left the SPGB in the 1970s, criticising the party’s parliamentary conception of revolution and arguing – as we shall see – that the SPGB was by no means the only authentically socialist organisation in the world, in opposition to the ‘hostility clause’ contained in its 1904 statement of principles[1]. Despite these criticisms, relations between Crump and the SPGB seem to have remained fraternal until his death in 2005, and it would also seem that one of the reasons why the Socialist Studies group split from the party (or as it sees it ‘reconstituted the SPGB’) in 1991[2] was the influence of Crump’s efforts to push the SPGB in certain untraditional directions.

The first part of the book is a straightforward account of what capitalism actually is, a task that it is as necessary as ever given the immense sea of confusion which surrounds the term. The idea that capitalism can be defined as individual enterprise or ownership, a conception shared both by the openly capitalist right and the allegedly anti-capitalist left, still has to be confronted and rejected: it was central to the ideology pervading the ‘Occupy’ movements of 2011, where notions of making the rich pay their taxes, abolishing bankers’ bonuses, defending public ownership etc were extremely tenacious despite the waning influence of the established organisations of the left within these movements. The essay was originally published as ‘State capitalism: the wages system under new management’ and the central aim of this return to basics is to show that state capitalism, whether in its Stalinist, social democratic or other political forms, remains capitalism because capitalism is not at root a form of property but a social relation, where the mass of producers are compelled to sell their labour power, and a capitalist minority (private or state) accumulate the value extracted from this inherently exploitative relationship. It then goes on to do what the SPGB has been doing for over a hundred years now: defend the fundamental principle that socialism (or communism, it rightly sees the terms as interchangeable) can only be based on the abolition of the wage relationship, and is a stateless, moneyless world community.

We have few criticisms of this section of the book, except to say that it has a somewhat timeless approach which doesn’t really explain why state capitalism has become the most important form of capitalist ‘management’ for the entire period of the SPGB’s history. For us, this can only be understood with reference to the passage of the capitalist mode of production from its ascendant to its decadent phase: in a system faced with near permanent war and economic crisis, and dangerous outbreaks of revolutionary class struggle, state capitalism - the state’s totalitarian grip on social and economic life - becomes a condition for ensuring the survival of the system. Although the SPGB has always rejected our conception of decadence, it holds some conceptions which are not far from it in practice, such as the idea that from the beginning of the 20th century capitalism had created the material conditions for abundance and thus for the socialist transformation, rendering capitalism ‘obsolete’. But the full implications of the system becoming a barrier to human progress have never been drawn by the SPGB, even if in conversations with individual members there is obviously a serious interest in this question.[3]

It also seems evident to us that there are many comrades in the SPGB who feel somewhat embarrassed by the idea that ‘electing a socialist majority’ to parliament could be at least part of the revolutionary process. We will come back to this, but for now we want to turn to two of the ideas contained in the essay by John Crump, who was, as we have already noted, a critic of the parliamentary road: the idea of the ’thin red line’, and the idea that socialism could be achieved without an intervening period of transition.

The essay ‘The thin red line and non-market socialism in the 20th century’[4] complements the essay by Adam Buick in the sense that it shows that most of the officially accepted varieties of ‘socialism’ are actually proponents of state capitalism and can thus be seen as a left wing of capitalism. Crump terms them ‘social democratic’ and ‘Leninist’, the latter referring mainly to the Stalinist regimes of the eastern bloc which were still in existence at the time of writing. We reject the term Leninist to describe these regimes, since this equates the Stalinist parties which managed them with the revolutionary Bolshevik party of 1917, but we don’t intend to enter into that debate right now.

Overall, we find this essay to be based on a positive and constructive premise: that throughout the 20th century, a genuine vision of socialism has been maintained by a number of political currents which have shared five key points in opposition to the false conception of socialism propagated by the left wing of capital: production for use; distribution according to need; voluntary labour; a human community; opposition to capitalism as it manifests itself in all existing countries. He categorises these currents as follows: anarcho-communism; impossibilism (groups like the SPGB) ; council communism; Bordigism; situationism. These groups make up the real socialist tradition of the 20th century.

We could object to the categories or see the need to update them: there are plenty of anarcho-syndicalists today who fulfil the criteria; there’s no space for left communist groups like the ICC and ICT which are neither council communist nor Bordigist; situationism is hardly a political movement these days while on the other hand there are a number of groups which belong to the ‘communisation’ current which certainly fit the overall category. And we could add various other political animals to the ark.

We could also say that the criteria for marking off a genuine socialist/communist movement from the left wing of capital should lay much more emphasis on the last point, which seems to be added as an afterthought. This is essentially the question of internationalism, and it’s the only one which actually refers to present day political issues rather than the programme for the future. And we have seen in the past how this criterion, above all when concretised by the question of imperialist war, has been a true dividing line between loyalty to and betrayal of the socialist cause.

However, as we said, the basic approach is a fruitful one. In opposition to the sectarianism of the ‘hostility’ clause, Crump is arguing that there something like a ‘proletarian political camp’ which shares certain common principles despite their many differences (such as the parliamentary question, the role of the vanguard party, etc). Crump even defends the Bordigists against the charge that their position on the party makes them indistinguishable from leftist groups like the Trotskyists. We don’t know where the SPGB officially stands on this idea of the ‘thin red line’. We do know that the Socialist Studies group specifically cited Crump’s views on this issue as a revision of the SPGB’s principles. The SPGB has always been prepared to debate with anyone, irrespective of their class nature. But this recognition of a wider milieu than the party itself demands something a bit more: it demands a recognition that we are comrades who should have an attitude of mutual solidarity towards each other, an attitude that is sadly missing in today’s proletarian political movement.

At the end of the essay Crump speculates that it might in future be necessary to add a sixth criterion: opposition to any notion of a transitional society. In his view socialism must be introduced straight away or not at all:

“One feature which capitalism and socialism have in common is their all-or-nothing quality, their inability to coexist in today's highly integrated world, which can provide an environment for only one or other of these rival global systems. In the circumstances of the twentieth century, the means of production must either function as capital throughout the world (in which case wage labour and capitalism persist internationally) or they must be commonly owned and democratically controlled at a global level (in which case they would be used to produce wealth for free, worldwide distribution). No halfway house between these two starkly opposed alternatives exists, and it is the impossibility of discovering any viable 'transitional' structures which ensures that the changeover from world capitalism to world socialism will have to take the form of a short, sharp rupture (a revolution), rather than an extended process of cumulative transformation....”

Here Crump is very much on the same lines as the SPGB (and others such as the communisation tendency).

We agree with Crump and the SPGB that state capitalism is not a transitional stage towards socialism, and that the economic programme of a victorious working class does not consist of ‘accumulating’ value to the point where here is a sufficient level of productive capacity to make abundance possible. Capitalism has already developed a huge overcapacity and what is required is the transformation of the productive apparatus rather than its ‘development’ in any capitalist sense.

But what strikes one is how superficially optimistic Crump’s vision is. He admits that capitalism has bequeathed us a bit of a mess which will have to be cleared up, and that some temporary measures may be needed to deal with shortages, but at the same time we will almost overnight (a few months, or at most a few years) have eliminated markets, nations, and all the rest of it, and be living in a world of free access communism.

It seems like a vast underestimation:

- Of the dire material consequences of capitalism surviving a hundred years into its epoch of senility, at the level of ecological damage, the waste and irrationality of a productive apparatus geared to competition and war;

- Of the inevitable brutal reaction of the ruling class which will not recognise any legal niceties in attempting to suppress a revolutionary movement;

- Of the near impossibility of the revolution being simultaneous in all countries at once, and thus the necessity to subordinate any economic measures taken in the area controlled by the working class to the number one priority of spreading the revolution internationally;

- Of the ideological poison distilled not only by a hundred years of barbarism but also of thousands of years of class society, of alienated social relations which will constantly hold back humanity’s efforts to become self-aware and self-organised[5];

- Of the inability of capitalism to create a world limited to bourgeoisie and proletarians, which means that the proletarian revolution will be faced with the task of integrating millions of individuals who belong to other non-exploiting strata and who will not have the same material interest in communism. Exchange will still exist with small property owners for example, hence the law of value will not vanish until all these social layers have been incorporated into the working class.

It’s of course true that to make the revolution in the first place the working class will have to confront and overcome many of the ideological obstacles which hold it down, as well as the physical barriers erected by the bourgeois state. But class consciousness is not something that is downloaded for good - it evolves through advances and retreats and there is no guarantee that even after the first victories of the revolution, initial difficulties in taking the communist programme forward will not result in regressions and even counter-revolutionary moods. The struggle for communist ideas will be every bit as intense after the revolution as before it. For all these reasons, a phase of transition between capitalism and communism will be inevitable.

This is a major discussion and we can’t hope to take it very far here[6]. But one thing does need to be said. Crump considers that the rejection of a transition period could be a sixth key point demarcating real socialists from apologists for capital, but we would suggest that some of the other differences among the ‘non-market socialists’ could become much more crucial well before the working class had assumed political power: in particular, we would expect that communists would be involved in a real political struggle against organisations and tendencies who argued that the councils should submit to this or that party ‘by right’ – or against those who argued that instead of being diametrically opposed to each other , councils and parliament can co-exist, a fatal error that helped bury the German revolution (and thus the Russian revolution as well) in 1918-19.

Amos

[1] https://revolutionarytotalitarians.wordpress.com/2012/04/01/john-crumps-critique-of-the-spgb/ [7]

[3] See also this recent contribution by Binay Sarkar of the Indian affiliate of the World Socialist Movement. www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/forum/general-discussion/ascendancedecadence... [9]

[4] theoryandpractice.org.uk/library/thin-red-line-non-market-socialism-twentieth-century-john-crump-1987

[5] There is a debate on the question of transition on the SPGB internet forum here. One of the SPGB’s posters – ALB – expressed surprise at the emphasis the ICC comrade (Alf) placed on the subjective elements of the revolutionary process and the necessary but difficult struggle against alienation: www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/forum/general-discussion/icc-way-and-our-way [10]

[6] For a more global view about why periods of transition between one mode of production and another are necessary, see: 'Problems of the Period of Transition (April 1975) [11]'

Life of the ICC:

Political currents and reference:

- SPGB [13]

People:

- Adam Buick [14]

- John Crump [15]

Rubric:

Frankenstein and the Luddites

- 6930 reads

In this article, one of our sympathisers (who posts as "Fred" on the ICC forum), makes an analysis of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein [17] and relates the symbolism of this classic novel to the struggles of the working class of the time and their impact on bourgeois ideology.

Everyone has heard of Frankenstein. He is an ugly and destructive monster, concocted by his mad -scientist creator from bits of dead bodies, and beloved by Hollywood film-makers and audiences alike. Anything nasty and unpleasant, like nuclear bombs, can be referred to as "frankensteinian" ; AIDS could appropriately have been called as such. But there's a flaw in all of this. Frankenstein, in Mary Shelley's novel published in 1818, is not the name of the monster, or "the creature" as she preferred to name it, but of the rich bourgeois medical student who manufactured it, after bouts of grave robbing, and whose name was Victor Frankenstein.

A recent viewing of the film Mary Shelley's Frankenstein gave this viewer a shock. The "creature" is played by an unrecognisable ......... so ugly is his face with its stitches. In one scene, in the depths of a very hard winter, he secretly assists a poor peasant family in whose barn he is hiding, by pulling turnips out of the frozen ground, which they can no longer manage themselves so hard is the frost. The creature himself has a massive strength and great reserves of energy. He leaves the turnips by their door. They in turn place food for "the spirit of the forest". And then it struck me. The "creature", the product of the bourgeois Victor Frankenstein's efforts, is none other than the working class. And the whole story can be read as a myth about the creation by the bourgeoisie of the labouring class, on whom it depends, and of which it is so fearful and sees as something necessary, yes, but unpleasant, ugly, frightening and uncivilized. Have things changed since then? (NB. A little research on the web confirms that this "Marxist" interpretation of the story has been around for some time.)

But, if this is the case, and i think it must be, the question arises as to whether Mary Shelley knew what she was doing, or whether the imagery of the story emerged from a subconscious response. Well we don't know of course. The story is set significantly in a revolutionary age at the time of the French Revolution, which was before Mary's birth. But there were certain dramatic events nearer home during the years leading up to her story (1812-1817) that might well have put an awareness of the emergence and growing strength of the working class into her mind. These events involved the Luddites, who doubtless struck fear into the hearts of the bourgeoisie with their machine breaking, potential for rioting, burning down buildings, and even dressing up as women in the streets. What monstrous horror it all was! What was happening to respectable society? Did the lower classes no longer know their place?

The bourgeoisie’s fear of the lower orders

The historian Eric Hobsbawm has pointed out that Britain had more troops fighting against the Luddites than it had fighting Napoleon in the Iberian peninsula. Parliament in Britain had a law imposing death on machine breakers, so seriously were the Luddites taken. Byron, the poet and friend of both Mary and Percy Shelley, in whose house they had been staying when the question of writing a horror story had first come up (Byron producing a draft of a story about Vampires - to be developed later by others into the Dracula and Vampire film industry) was moved to sympathize with the Luddites, saying they deserved pity not punishment, so miserable was their plight as their jobs were taken over by cheaper unskilled labour using the new machine technology.

Communists today may regret that the Luddites resorted to rioting and destruction, as not being best the way forward for the growth of proletarian solidarity and consciousness. But as Hobsbawm has also noted: there was no question of hostility to machines as such. "Wrecking was simply a technique of trade unionism in the period before and during the early phases of the industrial revolution." Yet such a technique may not have augured well for the development of the movement. And then there is the question of revenge. To lose your job is no fun, and to lose it to machinery and cheap labour an insult needing a vengeful act. Or so it can seem. The Luddites took revenge. The "creature", Frankenstein's monster, also takes savage revenge,on his creator and his creator's relatives. It is truly a horror story. But then everything involving the bourgeoisie is a horror story is it not, and even more so today?

In The Luddites 1811-1816 Marjie Bloy writes:

“Stocking knitting was predominantly a domestic industry, the stockinger renting his frame from the master and working in his own 'shop' using thread given to him by the master; the finished items were handed back to the master to sell. The frames were therefore scattered round the villages; it was easy for the Luddites to smash a frame and then disappear. Between March 1811 and February 1812 they smashed about a thousand machines at the cost of between £6,000 and £10,000. In April 1812 the Luddites burned the West Houghton mill in Lancashire. Samuel Whitbread, an MP, said of the event ‘As to the persons who had blackened their faces, and disfigured themselves for the purposes of concealment, and had attended the meeting on Deanmoor, near Manchester, it turned out that ten of them were spies sent out by the magistrates... These spies were the very ringleaders of the mischief, and incited the people to acts which they would not otherwise have thought of’. [Parliamentary Debates, lst Series, Vol. 23, Col.1000, (l8l2)] The authorities were incapable of stopping the attacks so the government felt obliged to put in place special legislation. Machine-breaking had been made a capital offence in 1721; in 1811 a special Act was passed to secure the peace of Nottingham. At the Nottingham Assizes in March 1812, seven Luddites were sentenced to transportation for life; two others were acquitted”.

It's worth noting here that "the blackened faces" contained government spies, an historic confirmation of the great duplicity of the ruling class and their penchant for Machiavellian strategies, even at the beginnings of the workers' movement. Did they dress as women too?

So, to return to Mary Shelley and her frankensteinian creature. Given the public activities of the Luddites, she may well have seen in her "scientifically" produced creature at least a reflection of the emerging and if-it-did-but-know-it all powerful working class. As the author of the novel, or perhaps as a woman, she does not find her "creature" as obnoxious as do most of the other characters in the story. As one commentator has said: the monster is the nicest person in the book. But then if he is "the working class" and most everyone else in it is bourgeois, and pursuing somewhat selfish interests as they do, then this is no surprise. In the middle of the novel Shelley undertakes to educate her creature, allowing him to learn to speak and then undergo a ferocious course of reading, centered largely on Milton's Paradise Lost which introduces the idea of the creature being an Adam who really requires an Eve. Perhaps what he really required was an Edward had he but known it. But this is a complication I will not be taking up here. The story ends in the frozen Arctic wastes, where both master and slave are cremated on the same funeral pyre. The creature by choice burned alive.

Working class, or capital itself?

You might of course interpret this story in a different manner, and see the creature not as the embodiment of the working class but as the materialized form of capitalism itself: ugly, frightening and immensely powerful. Yet even in this latter understanding the creature remains the product, the creation of the bourgeois Frankenstein; as is capitalism itself the uncontrollable and unwitting creation of the bourgeoisie as a class. Is such ambiguity the sign of good story?

But why is the tale so full of fear? The creature himself is fearsome to behold; strong and inclined to violence if frustrated. What he seeks is love and understanding; a very human requirement, and not one we would associate with unfeeling and relentless capitalism the system. Then there is science and the scientific endeavour. It is Frankenstein's ill-considered attitude to science which allows him to invent something he comes very much to regret. Rather like later scientific inventions such as the nuclear bomb and chemical and biological weaponry. Is science, in the hands of the bourgeoisie, another matter to be feared? Is the bourgeoisie always an irresponsible and immature class only capable of acting responsibly in the realm of profit pursuit where of course anything goes?

And then there are the Luddites. Not mentioned as such in the novel, but then neither are the bourgeoisie or working class. Is it from the Luddites that the initial fear underpinning the story originated? I speculate of course. But the Luddites were not typically working class as we understand that class now. They were an early manifestation of working class protest. You might even see them as having aspects of terrorism in their behaviour. They blackened their faces, cross dressed, smashed machinery and burned down factories. They doubtless instilled fear in the bourgeoisie. Who exactly were they? What did they want? Why did they behave in such a frightening and theatrical manner? We might compare them in some ways in their activity, to the Mau Mau in Kenya, using fear, secrecy and terrorism in pursuit of their aims, and installing an inexpressible anxiety in their bourgeois suppressors. But the example doesn't properly hold - the Mau Mau being an aspect of the bourgeoisie themselves, looking for national liberation, which the Luddites were certainly not - only the form of protest may be compared.

That the creature represents Napoleon, as seen by the English bourgeoisie, is not I think one we can go along with. Pulling turnips, living with peasants, learning to read surreptitiously, these are not things easily associated with Bony, though he was of course, through and through, a manufactured creature of the bourgeoisie himself!

Fred

People:

Rubric:

Hunger in the 'rich world'

- 1513 reads

The rise in the use of food banks has reached huge proportions. The food banks, originally intended for the most destitute within society, are starting to be used across all sectors of the working class, often including those parts who might have previously seen themselves as belonging to the ‘middle class’. The figures produced by the Trussel Trust (a charitable organisation) are revealing: in Britain in every town and city we have seen the opening up of food banks, and the number of people needing the banks to feed themselves and their families has gone up as follows:

| 2008/9 | 26,000 |

| 2011/12 | 128,697 |

| 2013 | 200,000 (estimated for this year so far) |

It’s not just in Britain where we’ve seen populations resorting to food banks. Over this past year in Greece and Spain we have seen the same situation: workers being forced into queuing for food hand-outs in order to live. However, these are economies which are openly bankrupt and these are emergency measures, are they not? But even in a much more prosperous country and economy such as Canada we are seeing the same thing:

“Last year Mr. De Schutter (a UN official) completed an 11 day mission to Canada, his first to a developed country. He reported ‘very desperate conditions’ in a country where 850,000 rely on food banks and condemned the Canadian government’s ‘self-righteous’ failure to acknowledge the scale of the problem on its doorstep” (‘UN Official alarmed by Food Banks in UK’, Independent 17.02.13)

Chronic and society-wide hunger used to be associated with the countries of the ‘Third World’, but it’s now spreading in the bastions of the ‘Rich World’ as well. It’s the same the whole world over under austerity.

Melmoth 1/9/2013

Geographical:

- Britain [19]

Recent and ongoing:

- Poverty [20]

Rubric:

Solidarity appeal for the renovation of Gondolkodó Autonóm Antikvárium (Gondolkodó Autonomous Bookshop), Budapest

- 1805 reads

We publish below an appeal by the Hungarian bookshop Gondolkodó Autonóm Antikvárium that we received with the request to support them and to spread the appeal. The ICC has known and appreciated this bookshop for more than 15 years. Our press is available at this address, as well as a lot of other internationalist publications in different languages. We have also been able to take part in different discussions organised in Budapest by the bookshop.[1] In fact it is one of the rare bookshops with this proletarian (and not left bourgeois) focus in the East Central European region, even though we don’t know if it is the only one which has been functioning continuously for many years as the comrades write in their appeal.

A bookshop can be a place for distributing revolutionary positions and – even more important – for discussions about them in search for political clarification and theoretical coherence. The comrades of Gondolkodó Autonomous Bookshop and the ICC agree on the necessity to overcome the capitalist mode of production and national states, even if we have divergences about other issues, namely about the role of the revolutionaries and how to organize as such. However this is not an impediment to spreading this solidarity appeal but a stimulus for further debate – in Budapest or elsewhere, on the internet or in personal meetings.

ICC, 26/07/13

Solidarity appeal for the renovation of Gondolkodó Autonóm Antikvárium (Gondolkodó Autonomous Bookshop) 2013 Summer.

The Gondolkodó Autonomous Bookshop is the only workers’ movement distribution place, library and meeting-place in the East Central European region (namely in Hungary) which has been functioning continuously for many years (now for 20 years). Now this place must be renovated because the walls are wet and mouldy, the mortar has been falling, the sets of shelves are rickety, the drainpipe is often clogged up etc. The condition of the library has been worsening gradually and also the distribution of publications is harder under these circumstances.

Since we can not pay for all the costs of the general renovation we ask for your financial help in order that we could do the renovation during the summer. Please support this aim according to your possibilities (if you can send 10 Euros then do it, but if you have more money you can send a bigger amount).

Comrades, activists and sympathisers, please spread our solidarity appeal and support us!

Thanks for your help in the name of internationalist proletarian solidarity!

GONDOLKODÓ AUTONOMOUS BOOKSHOP

Hungary- Bp-1012 . Logodi Utca 51

website : gondolkodo.mypressonline.com [21]

e-mail: [email protected] [22]

https://www.facebook.com/gondolkodo.antikvarium [23]

Raiffeisen BANK

Name : Tütö László

Iban : HU 3912 0101 5401 3152 1900 2000 06

Swift code : UBRTHUHB

[1] See for instance our article on a public meeting held in 2010 at Budapest about the world economic situation and the perspectives for the class struggle, https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/2010/12/hungary-public-meeting [24]

Life of the ICC:

Geographical:

- Hungary [26]

Rubric:

Syria vote: impasse of British imperialism

- 1545 reads

The closeness of the vote expressed just how deeply conflicted the British ruling class is, and not only over Syria but its whole imperialist strategy.

Once British imperialism had its empire. Following the loss of Empire as the result of two world wars, it became the USA's loyal lieutenant during the Cold War. This meant that despite being a second rate military power it could have a place at the top table, or as parts of the ruling class like to say: punch above its weight.

With the disappearance of the old bloc system British imperialism has been faced with the increasingly complex problem of how best to defend its own interests. Should it simply remain loyal to the USA? Move more towards Europe, or somehow try to maintain an independent course adapting itself to challenges as they arrived? This strategic choice has become increasingly problematic as the world has sunk deeper and deeper into evermore chaotic international relations. In 1991 it was a pretty easy decision for the British ruling class to go along with the USA in attacking Iraq. There were parts of the ruling class that warned about the dangers of the new world order. British imperialism however did not come out of this war too badly. Only 12 years later however the decision to back the US in the 2nd Gulf war was more problematic because parts of the ruling class feared the chaos that would follow and the danger of linking the national interest so closely to that of the US. Blair and the pro-US fraction that he represented drove through the decision however, using every devious trick in the book to get support. However, far from furthering the national interest it suffered a bitter humiliation as Iraq, and Afghanistan, sunk into chaos and British armed forces were exposed as being dependent upon the US. Blair, and thus the British ruling class, became linked with George W Bush and a visibly declining US imperialism. Supporting the US has become extremely costly.

On the other hand, not supporting US military action means accepting not being able to punch above one’s weight, and being a secondary power. Also where do you turn for alliances? There are those who say closer relations with Europe are the way forwards, but this increasingly means a complex game of alliances against the rising power of German imperialism. The Cameron team with the backing of much of the ruling class had been pursuing a policy of seeking to build relations with the growing powers such as India, Brazil, Turkey, as well as commercial relations with China.

However, all the relations that the British bourgeoisie build in Europe and beyond are increasingly unstable because of its increasing inability to use its close relations with the US to counter-weigh the actions of its rivals.

It is in this context that we have to understand the events around the vote on Syria. The divisions went across party lines and reflected the deeper division in the whole ruling class.

To go along meant being pulled further into the consequences of the US declining status ie desperate military action in Syria in order to try and display US military superiority but at the possible cost of being sucked into another war. Former military leaders openly stated their opposition to becoming involved: “A former head of the navy, Lord West, and a former head of the army, Lord Dannatt, reflected widespread criticism within the military and defence circles by pouring scorn on claims by ministers that military strikes did not mean the UK or the US were taking sides in the civil war. ‘As regards a limited strike, this was always an impossible notion,’ said Dannatt. ‘Any use of explosive ordnance by the west, for whatever purpose, would have committed us to participation in the Syrian civil war irrevocably’.” (The Guardian, 31.8.2013). The historical significance of not supporting the US was clearly stated by a former adviser to the Foreign and Defence secretaries, Crispin Blunt, who said “he hoped the vote would relieve Britain of its ‘imperial pretension’ and stop it trying to punch above its weight on the world stage” (ibid).

It was the loss of this role on the world stage that concerned those in favour of supporting the US’s action. This was made clear by Michael Clarke, the director general of the Royal United Services Institute (one of the British imperialism’s main think tanks): “...there is a danger it could become a tipping point where the UK falls into strategic irrelevance in US eyes. We can all be friendly, well respected, kith and kin, etc -like the Dutch- but just not be taken seriously as a strategically significant player in security matters” (ibid).

The events around the US’s announcement that it was going to strike Syria have thus placed the British ruling class on the rack.

The US however, also suffered through these events. Its international authority was further undermined by its inability to get the support of its partner in the ‘special relationship’. French imperialism may now be the US’s “oldest ally” but it is clear to everyone that John Kerry only said that to insult the British ruling class. For US imperialism having to rely on a country which only a few years ago it was pouring scorn on for not supporting the 2nd Gulf War, is not a sign of strength but historical weakness.

The US will not forgive British imperialism easily. Obama’s refusal to hold a meeting with Cameron at the G20 meeting in Russia was a very public snub, which very visibly demonstrated the price of not supporting them. The other major imperialist powers will also take note of this.

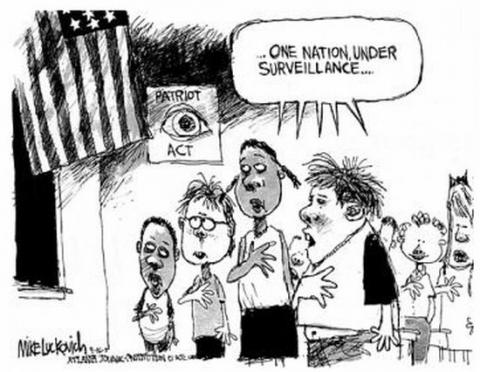

This decision not to back the US whilst being fundamentally a matter of how best to defend the national interest, also reflected a self-inflicted wound. The blatant manipulation of public opinion over the 2nd Gulf war, Blair’s talk about Weapons of Mass Destruction etc, and the trouble and tragedy that unfolded in Iraq afterwards, badly dented confidence in politicians. This meant that the public was highly sceptical of any claims made by the government. The vote against military action has certainly boosted the idea that parliament has some power, and thus strengthened democratic illusions. If the most powerful parts of the ruling class had wanted to support the US, they would have done so but it would have been at the cost of a further weakening of any confidence in the ruling class.

Cameron et al may have wanted to use the US insistence on action as a means to push the rest of the ruling class to support such action and thus the special relationship, but it is clear that important parts of the ruling class refused to go along with this. This is an event of historical importance because it expresses a further step in the decline of British imperialism. A decline that will exacerbate the divisions in the ruling class, and push it to take up more military actions where it can in order to make a display of its power, no matter how limited. There may be a resurgence of the pro-US fractions as this historical weakness becomes clearer, but the US will be extremely wary of the British ruling class. British imperialism is being pushed further onto the side lines.

Phil, 6.9.13

Geographical:

- Britain [19]

General and theoretical questions:

- Imperialism [27]

Rubric:

Syria: behind the diplomatic game, the impasse of a murderous system

- 1937 reads

The hideous spectacle of the children’s bodies exhibited after the chemical attacks of 21 August on the outskirts of Damascus didn’t truly move the world leaders, whose hypocritical reactions were dictated solely by their imperialist interests. The use of gas by both sides during the First World War, the unleashing of chemical agents in Vietnam and of the atomic bomb against Japan are all proof that our wonderful democracies have never hesitated to resort to the most murderous weapons. The declarations coming from the government offices are all the more hypocritical because the bombing and massacre of the Syrian population, the over 100,000 deaths since the war began, the flight of millions of refugees fleeing the carnage have, up till now, not been a ‘red line’ as far as the bourgeoisie is concerned.

An aggravation of imperialist tensions

It’s possible that the use of chemical weapons was a Syrian/Russian provocation (Assad had been warned several times by Obama in 2012 that he must not cross this ‘red line’) in the direction of rival powers, principally the USA and France. But in any case the ‘red line’ was never more than more than a highly mediatised pretext to prepare ‘public opinion’ for an eventual military intervention. In the face of the growing tragedy, all the comings and goings between the various states are no more than a jockeying for imperialist interests in which the populations on the ground are of no importance . And it’s precisely the relations between the rival powers which explain the length of the conflict and the atrocious suffering of the populations: by comparison, other regimes swept away by the ‘Arab spring’, like Libya, didn’t last anything as long because it was less crucial as a focus for inter-imperialist rivalries.

Russia scored a diplomatic coup when it proposed placing Syria’s chemical weapons under “international control”; this produced a flurry of further diplomatic initiatives by its rivals, which have not hidden the impotence of the latter, and of the USA in particular. But whatever the outcome of this latest crisis and the decisions taken in government ministries, and whether or not there is a direct military intervention in Syria, we are seeing a spectacular rise in warlike tensions against a background of mounting chaos, of an increasingly uncontrollable situation which has made the clash of arms more and more widespread. The use of chemical weapons on several occasions already, the extension of the conflict to Lebanon, the presence of all kinds of vultures in the region, from Qatar and Saudi Arabia to Turkey and Iran, whose involvement in the conflict is a particular source of anxiety for Israel, are all evidence that the conflict reaches well beyond the borders of Syria. Even more significant is the presence of the bigger imperialist powers, which illustrates the level reached by imperialist rivalries since the end of the Cold War. Thus, for the first time since 1989, we are seeing a major political confrontation between the old bloc leaders, the USA and Russia. Although very much weakened by the disintegration of the eastern bloc and of the USSR, Russia has been going through a revival, after carrying out a scorched earth policy in Chechnya, Georgia and the Caucasus during the 1990s. For Russia, Syria is vital for ensuring its presence in the region, holding on to its strategic links with Iran, restricting the influence of the Sunni Muslim republics on Russia’s southern borders, and maintaining a port to the Mediterranean.

This sharpening of tensions can also be measured by the fact that China is much more openly opposing the US than in the past. Although during the period of the blocs China moved very far from Russian influence, having been neutralised by the American camp following the bargain struck with Nixon over the war in Vietnam, it is now becoming a major opponent which is worrying the USA more and more. With its meteoric rise on the economic level, China has also been advancing its imperialist interests in Africa, the Far East, and Iran, a primary aim being to ensure its access to energy. As a late arrival on the scene it is a major factor in the further destabilisation of imperialist relations.

The strengthening of these two powers has been possible, above all, because of the increasingly evident weakening and isolation of the USA, whose attempts to play the role of world cop have met with utter failure in Afghanistan and Iraq. We can get some idea of how difficult things have become for the US by comparing its ‘intervention’ in Syria with the role it played in the first war against Iraq, back in 1991. Using Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait as a pretext for a huge display of its military superiority, it succeeded in building a military ‘Coalition’ involving not only a number of Arab countries, but also the principal members of the western bloc which were already tempted to break free of the USA’s grip following the disintegration of the eastern bloc. Germany and Japan, though not involved militarily, bankrolled the adventure while Britain and France were directly ‘called up’ for the fighting. Gorbachev’s ailing USSR did nothing to stand in America’s path. Just over a decade later, with the second invasion of Iraq, America had to deal with active diplomatic opposition from Germany, France and Russia. And while in both in the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and of Iraq in 2003, America could count on the loyal support, diplomatic and military, of Britain, the latter’s defection from the planned military intervention in Syria was key to the Obama administration’s decision to call off the intervention and to listen to the diplomatic option put forward by Moscow. The vote in the Commons against Cameron’s proposal to support military intervention is testimony to deep divisions in the British bourgeoisie resulting from the country’s involvement in the quagmires in Afghanistan and Iraq[1], but above all it is a measure of the weakening of US influence. The sudden discovery that France, which continued to support the push to intervene, is America’s “oldest ally” should not give rise to any illusion that France is going to take on the role of loyal lieutenant which Britain has (notwithstanding its own ambitions to seek a more independent role) played in most of the USA’s imperialist enterprises since the end of the Cold War. The alliance between the US and France is much more circumstantial and thus unreliable as far as the US is concerned. To this we can add the discretely discordant notes coming from Germany, whose quiet rapprochement with Russia is another concern for Washington.

At the time of the first Gulf war in 1991, President George Bush Senior promised a New World Order, with the US Marshall keeping things nice and peaceful. What we have actually seen is a growing imperialist free for all, dragging the world towards barbarism and chaos.

The strategic importance of Syria

In the context of this new battleground, Syria is a very important strategic prize. Modern Syria emerged early in the 20th century with the downfall of the Ottoman Empire. During the First World War, Britain mobilised Syrian troops with the promise that the country would be granted independence after the war was won. Britain’s aim was of course to maintain its control of the region. But already in 1916, following the secret Sykes/Picot accords, Britain ceded control of Syria to France. The main aim of this agreement was to block the ambitions of Germany, which had already envisaged the construction of the Baghdad railway in order to “bring Constantinople and the military strongholds of the Turkish Empire in Asia Minor into direct connection with Syria and the provinces on the Euphrates and on the Tigris”[2] Today, because of the instability of the traditional maritime routes through the Persian Gulf, Syria has become one of the terrestrial routes for the transport of hydrocarbons. Opening onto the Mediterranean through a corridor on the Levant (which is also used for the transfer of weapons from Russia) and to the east towards the oil-producing countries, this will be an increasingly important factor in the politics of the region.

The tensions developing today are this to a large extent linked to Syria’s historic importance in the region. They are also fuelled by the role played by Israel, whose threats against Syria and Iran[3] are a further source of disquiet for the large imperialist powers. Regional powers like Saudi Arabia and Qatar are deeply involved, being the main purveyors of arms to the ‘rebels’, while Turkey is also seeking to defend its interests by playing on the presence of a Kurdish minority in northern Syria.

And there is also a major polarisation around the Shia regime in Iran, which controls the strategic oil route through the Straits of Hormuz. This is intimately linked to the naval build up in the area, particularly of the US fleet. It also explains Iran’s commitment to its nuclear programme, which Putin provocatively supports, calling for “aid for the construction of a nuclear power station”.

Towards unprecedented chaos

Up till now, the blood-soaked Assad regime has been seen by all the imperialist powers as one that ensures a certain stability and predictability, as something less worse than what might take its place. Today, if the Syrian opposition ended up on top, there’s no doubt that there would be a chain reaction leading to incredible chaos and all kinds of unpredictable scenarios. The Free Syrian Army is a real patchwork and there is no truly united opposition. This weak political conglomeration, despite the discrete support of pro-American and pro-European forces, who have been ensuring the flow of arms without any ability to control their circulation, has been infiltrated, or at perhaps flanked by jihadi terrorist groups, many of whom have come from outside Syria and are acting for their own interests like the warlords who flourish in Africa today. There is more or less zero possibility of the western powers being able to rely on a real opposition that can offer an alternative to the regime.

This is a wider phenomenon which we can see in all the other Arab countries that were faced with similar events during the Arab Spring: no real bourgeois opposition able to offer a ‘democratic alternative’ and a minimum of stability. All these regimes have only been able to survive thanks to the strength of the army, which has tried to hold together the numerous clans of the ruling class and prevent society from falling apart. We saw it in Libya and more recently in Egypt following the army coup d’État against Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. All this is the expression of a real impasse, typical of capitalist decadence and especially of its final phase of decomposition, where all that can be offered during an economic crisis is poverty, the brute force of the army, repression and bloodletting.

And this situation is all the more disquieting because it is feeding religious divisions which in this part of the world are among the sharpest: divisions between Christians and Muslims, Shia and Sunni Muslims, between Muslims and Jews, between Muslims and Druze, etc. Without being directly at the root of the conflicts in the region, these fractures are deepening the hatreds and hostilities of a society which has no future. This is also a region which in past has been marked by numerous genocides, as in Armenia, by the expulsion of populations, by colonial massacres which have left a legacy of hatred that in turn serves as the source of new massacres. Syria in particular is a focus for these divisions (Alawite/Sunni, Muslim/Christian, etc) and under the cover of war there have been innumerable cases of pogroms against this or that community, with the influx of fanatical jihadis, some backed by Saudi Arabia, making the situation worse than ever.

The catastrophe is all the more serious in that the US, a military super-power in decline, has been spearheading the descent into chaos. It has gone from world cop to pyromaniac fireman. In 2008, when Obama triumphed over Bush, it was in no small measure due to his image as an alternative to the unpopular warmonger Bush. But now the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Obama has shown himself to be no less of a warmonger, despite his talents as a politician, something his predecessor didn’t possess. Obama is more and more losing credibility. He has to deal with public opinion which is increasingly opposed to war, increasingly affected by the Vietnam syndrome, while at the same time facing an unbearable economic crisis which makes it more and more difficult to lavish money on military crusades. For the moment, the USA’s retreat from punishing the Assad regime with military strikes can be explained by invoking very real geo-strategic difficulties, but this has also led Washington into resorting to new contortions, such as the hypocritical and ridiculous distinction between “chemical weapons” and “weapons which only use chemical components”. Some nuance!

With the increasing number of quagmires, the mystifications which served their purpose in justifying the military crusades of the 90s – “clean war”, “humanitarian intervention” etc - have lost their impact. The USA is facing a real dilemma which is undermining its credibility with its allies, especially Israel, which has become more and critical of the Americans. The dilemma is this: either the US does nothing, and this can only embolden its rivals and encourage new provocations on their part; or they strike out and his only increases hostility and resentment towards them. What is certain is that like all the other imperialist powers, they can’t escape the logic of militarism. Sooner or later, they can’t keep out of new military campaigns.

The only alternative: socialism or barbarism

The infernal spiral of these military conflicts once again highlights the responsibility of the international proletariat: even if it is not in a position to have an immediate effect on the growing military barbarism, it is still the only historic force that can put an end to his barbarism through its revolutionary struggle. Since the beginning of the events, and above all from the moment when the open armed conflict began to overwhelm it, the weakness of the proletariat in Syria has meant that it is not able to respond to the war on its own class terrain. As we have already pointed out, “the fact that the manifestation of the ‘Arab Spring’ in Syria has resulted not in the least gain for the exploited and oppressed masses but in a war which has left over 100,000 dead is a sinister illustration of the weakness of the working class in this country – the only force which can form a barrier to military barbarism. And this situation also applies, even if in less tragic forms, to the other Arab countries where the fall of the old dictators has resulted in the seizure of power by the most retrograde sectors of the bourgeoisie, represented by the Islamists in Egypt or Turkey, or in utter chaos, as in Libya”[4].

Today, the course of events fully confirms the perspective which Rosa Luxemburg put forward in The Junius Pamphlet:

“Friedrich Engels once said: ‘Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.’ What does “regression into barbarism” mean to our lofty European civilization? Until now, we have all probably read and repeated these words thoughtlessly, without suspecting their fearsome seriousness. A look around us at this moment shows what the regression of bourgeois society into barbarism means. This world war is a regression into barbarism. The triumph of imperialism leads to the annihilation of civilization. At first, this happens sporadically for the duration of a modern war, but then when the period of unlimited wars begins it progresses toward its inevitable consequences. Today, we face the choice exactly as Friedrich Engels foresaw it a generation ago: either the triumph of imperialism and the collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration – a great cemetery. Or the victory of socialism, that means the conscious active struggle of the international proletariat against imperialism and its method of war. This is a dilemma of world history, an either/or; the scales are wavering before the decision of the class-conscious proletariat. The future of civilization and humanity depends on whether or not the proletariat resolves manfully to throw its revolutionary broadsword into the scales”.

WH, September 2013

.

[1] For further analysis of the Commons vote against intervention, see https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201309/9114/syria-vote-impasse-british-imperialism [28]

[2] Rohrbach, The War and German Policy, quoted by Rosa Luxemburg in The Junius Pamphlet, chapter 4.

[3] Israel has issued virtual ultimatums to Iran over its nuclear policy, while it still has a dispute with Syria over the Golan Heights.

[4] Resolution on the international situation, 20th ICC Congress

Geographical:

Recent and ongoing:

- Syria [30]

Rubric:

Syria: imperialist war or class solidarity!

- 2780 reads

Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Egypt, Syria, the massacres keep spreading. The horror of capitalism accelerates, deaths pile up. A continuous carnage that no one seems able to stop. Capitalism in utter decomposition is dragging the world into generalised barbarism. The use of chemical weapons as in Syria today is unfortunately only one of the instruments of death among many others. But there is nothing inevitable about this perspective, which left to itself will result in the destruction of humanity. The world proletariat cannot remain indifferent in the face of all these wars and massacres. Only the proletariat, the revolutionary class of our epoch, can put an end to this nightmare. More than ever humanity is faced with one choice: communism or barbarism.

The Syrian population is being sacrificed on the altar of imperialism

On Monday 21 August an attack with chemical weapons left hundreds dead in an area close to Damascus. On the internet, on TV screens and the newspapers there were unbearable images of men, women and children in agony. The bourgeoisie, without any scruple, has seized on this human tragedy to advance its sordid interests. The regime of Bashar al Assad, a butcher among butchers, has, we are told, crossed a red line: you can use any weapons to slaughter people, but not chemical ones. These are ‘dirty’ weapons, as opposed to the ‘clean’ ones like conventional bombs and mortars or even the atomic bombs the Americans dropped on Hiroshima or Nagasaki in 1945. But the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie has no limits. Since the First World War of 1914-18 where poison gas was used massively for the first time, killing several hundred thousand people, chemical weapons have been continuously perfected and used. The superficial agreements about their non-utilisation, especially after the two world wars and in the 1980s, were just empty declarations, which were not meant to be applied[1]. And many theatres of war since this time have seen these kinds of weapons being used. In North Yemen between 1962 and 1967, Egypt used mustard gas without restraint. In the Iran-Iraq war in 1988, towns like Hallabja were bombarded with chemical weapons, leaving over 5000 dead, under the benevolent gaze of the ‘international community’ of the US, France and all the members of the UN! But they are not just the speciality of small imperialist countries or dictators like Assad or Saddam Hussein, as the bourgeoisie would like us to believe. The most massive use of chemical weapons, alongside napalm, was carried out by the USA during the Vietnam war. Vast amounts of herbicide contaminated with dioxin were used to destroy rice plantations and forests in order to reduce the population and the Vietcong to famine. This scorched earth policy, this deliberate desertification, was the work of American capital in Vietnam, the same which today, alongside supporters like France, is getting ready to intervene in Syria, allegedly to defend the population. Since the start of this war in Syria, there have been over 100,000 deaths and at least a million refugees fleeing to surrounding countries. Looking past the discourse being poured out by the bourgeois media, the working class has to know the real causes behind this imperialist war in Syria.

Syria: it’s decadent capitalism which is responsible

Syria is currently at the heart of the imperialist tensions and conflicts which are extending from North Africa to Pakistan. If the Syrian bourgeoisie is tearing itself apart inside a country which is now in ruins, it has been able to rely on the insatiable appetites of a whole number of imperialist powers. In this region, Iran, Hezbollah from Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey are all more or less directly involved in this bloody conflict. The most powerful imperialisms in the world are also defending their squalid interests. Russia, China, France, Britain and the USA are playing their part in the continuation of this war and its extension across the region. Faced with their growing incapacity to control the situation, they are more and more just sowing death and destruction, according to the old scorched earth policy (‘if I can’t dominate this region, I will set it on fire’).

During the Cold War, the period which went officially from 1947 to 1991 and the fall of the USSR, two blocs confronted each other, led by Russia and the USA respectively. These two superpowers directed their ‘allies’ or ‘satellites’ with an iron hand, forcing them to fall in line in the face of the enemy ogre. This ‘world order’ was based on the discipline of the bloc. It was a historical period that was full of danger for humanity, because if the working class had not been able to resist, even passively, the ideological march towards war, a third world conflagration would have been possible. Since the collapse of the USSR, there are no longer two blocs, no more threat of a third world war. The discipline of the blocs is in pieces. Each nation is playing its own card; imperialist alliances are increasingly ephemeral and circumstantial. As a result conflicts are multiplying and in the end no bourgeoisie can control it. This is chaos, the growing decomposition of society.

Thus the accelerating weakness of the world’s leading imperialist power, the US, is an active factor in the whole Middle East plunging into barbarism. Immediately afterthe chemical attack on the suburbs of Damascus, the British and French bourgeoisie, followed much more timidly by the American bourgeoisie, declared loudly that such a crime could not go unpunished. A military response was imminent and it would be proportionate to the crime. The problem is that the American bourgeoisie and other western bourgeoisies have been through a serious reverse in Afghanistan and Iraq, countries which are also in a total mess. How could they intervene in Syria without finding themselves in the same situation? This has resulted in some very significant foreign policy differences within the ruling class, and the recent rejection of Cameron’s call for military action in the UK parliament was a graphic expression of these divisions. On top of this, these bourgeoisies also had to deal with what they call public opinion. The population of the west doesn’t want this intervention. The majority no longer believe the lies of their own bourgeoisies. The unpopularity of this proposed intervention, even in the form of limited bombings, has posed a problem for the ruling class in the west.

The British bourgeoisie has thus had to renounce its initial bellicose declarations and move away from the path of military intervention. This expressesthe fact that all the bourgeoisie’s solutions are bad ones: either it doesn’t intervene (as Britain has just decided to do) and this is then a big statement of weakness; or it does intervene (as the US and France are still planning to do) and they risk stirring up more chaos, more instability and incontrollable imperialist tensions.

Only the proletariat can put an end to this barbarism

The proletariat cannot remain indifferent to all this barbarism. It is the exploited who are the main victims of the imperialist cliques. Whether it’s Shia, Sunni, secular, or Christian being massacred, it makes no difference. There is a natural and healthy human reaction to want to do something about this right away, to stop these abominable crimes. It is this sentiment which the grand democracies are trying to exploit, justifying their warlike adventures in the name of ‘humanitarian’ causes. And each time the world situationgets worse. This is clearly a trap.

The only way that we can express real solidarity towards all the victims of decaying capitalism is to overthrow the system which produces all these horrors. Such a change can’t happen overnight. But if the road towards it is long and difficult, it’s the only one that can lead to a world without wars and countries, without poverty and exploitation.

The working class has no national flag to defend. The country where it lives is the place of its exploitation, and in some parts of the world, the place of its death at the hands of imperialism. The working class has a responsibility to oppose bourgeois nationalism with its own internationalism. This is not an impossibility. We have to remember that the First World War was brought to an end not by the good will of the belligerents, or by the defeat of Germany. It was ended by the proletarian revolution.

Tino 31/8/2013

[1] The ‘Greatest Briton’ of all, Winston Churchill, certainly never stopped arguing for and even sanctioning their use, whether against ‘primitive tribesmen’ in rebellion against the Empire, the revolutionary workers of Russia, or the German proletariat during the Second World War: see, for example:

https://en.internationalism.org/wr/265_terror1920.htm [31]

https://ihr.org/journal/v06p501b_Weber.html [33]

Geographical:

Recent and ongoing:

- Syria [30]

Rubric:

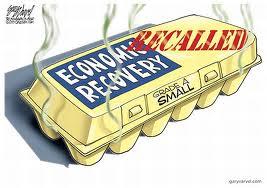

Talk of recovery masks the underlying disease

- 1417 reads

For several weeks there has been such a torrent of unexpected good news about the British economy that our rulers have become quite excited. It has given a shot in the arm to the markets, because of an expectation of an earlier than predicted rise in interest rates. And it has helped push the IMF to a humbling re-appraisal of the criticisms it has previously made of the British government’s economic policy. In fact the IMF is now praising the British government’s approach to economic management as the light of the world, replacing the old fashioned idea that China and the other emerging countries offered hope to us all.

The bourgeois media’s commentary on this alleged recovery has been quite informative, and we can largely let them tell the story in their own words. Unfortunately for the bourgeoisie, it’s a recovery that turns out not to have lasted very long.

When Cameron and Osborne came to power, they gave the impression that a short but severe bout of austerity measures would be sufficient to rein in the deficit and pave the way to recovery in fairly short order. Therefore, although austerity is not enjoyable in itself, the rewards would soon be available and effectively cancel out the necessary reductions in living standards. As the bourgeoisie themselves admit, the reality has been that they have not managed to steer the economy even back to the level of economic output that prevailed prior to the financial crisis of 2007. An important consideration that partially accounts for the governing team in particular now talking confidently about ‘recovery’ is that they could foresee getting back to that level of output prior to the next election. That would have given them enough to suggest that the original promises of the government were not completely hollow.

Except during the admittedly extended periods when it was actually in recession, there has not been an absolute lack of good news about the British economy since the outbreak of the financial crisis. The difficulty for the bourgeoisie in creating a convincing story of good news about the economy is that each piece of good news has been followed almost straight away by bad news. If industrial output was up, services were down, and vice versa. If exports were up, consumer demand was down. If employment was up, unemployment (surprisingly) was not down. And so on, along those lines, the evidence has gone for years.

The difference over recent weeks was a series of reports on different aspects of the economic situation that all tended to exceed the rather cautious expectations of forecasters who were used to getting their fingers burnt by over-optimistic predictions. As the Financial Times said on September 5th:

“Expert economic opinion regularly bends with the wind. Rarely has it been blown so far so quickly. Talk of a ‘flatlining’ economy was universal until the spring, when fears of a ‘triple-dip’ (recession) disappeared. But after a string of good economic figures and the release of an extraordinarily strong services sector business survey yesterday, economists rushed to judge that growth was running at boom-time rates. …

If the economy is growing at 1 per cent this quarter ... that rate of growth is roughly the pace of former rapid recoveries from recession. If sustained, output would finally climb back above the level of its previous peak (before the financial crash) in spring 2014, a year before the general election.…

Civil servants and central bankers know that the speed of recovery says little about its breadth or durability and are still struggling to explain the turnaround. Before they swap caution for confidence, they will want to take stock of the wider picture which remains mixed.”

Without going through the FT’s retailing of the mixed evidence, we can skip to the following day, September 6th when the run of good headline news fell apart:

“A damper was put on rapid recovery hopes today with disappointing industrial production figures and a widening of Britain’s stubbornly high trade deficit in July.

Industrial output was flat over the month after a healthy 1.1% expansion in June. Economists had expected production to edge up slightly. The trade in goods deficit rose to £9.8 billion, considerably larger than City traders’ forecasts of 8.15 billion.

The monthly gap was higher than the £7.3 billion deficit recorded in July 2012. There were also signs of problems in emerging markets beginning to affect British firms, with export to non-European countries plunging by almost 16%.” (from The Evening Standard)

The fact that “problems in emerging markets” are affecting the hopes of the bourgeoisie for a broadly based recovery in the British economy should give the International Monetary Fund pause for thought. Again we can refer to an article in the FT of September 5th:

“Turmoil in emerging markets this summer has forced the IMF into a humbling series of U-turns over its global assessments.

In a confidential note seen by The Financial Times, the IMF has dropped its view of emerging economies as the dynamic engine of the world economy, instead noting that ‘momentum is projected to come mainly from advanced economies where output is expected to accelerate’.”

This is very sound, except for the last point. Presumably we are due to hear much less, at least from the IMF, about China, the Brics and ‘globalisation’ being the light of the world in economic terms. That’s a relief! As the ICC has always pointed out, the basic foundations of globalisation, of a world economy, had already been achieved by the end of the ascendant period of capitalism, i.e. by the beginning of the twentieth century, and it was precisely at this point that the system entered into its historic crisis.