Capitalism in the ascendant: prior to World War I

- 1920 reads

Rubric:

Japan: a newly emerging capitalist force

- 1911 reads

Between the middle of the 17th and the middle of the 19th century, Japan cut itself off from the rest of the world. No foreigner was allowed into the country, no Japanese was allowed to leave the country without permission, trade with other countries was limited to very few ports. Even if there was a very limited and weak dynamic of trade developing within the country, the real historical breakthrough occurred when the country after almost two centuries of self-imposed seclusion was forcefully opened up by capitalism. As Marx and Engels analysed in the Communist Manifesto in 1848: “In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations.... It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production..”(first chapter of the Communist Manifesto, Bourgeois and Proletarians).

In 1853, shortly after the first opium war had ravaged China, US navy vessels first appeared in Japanese waters and enforced mainly free trade. Following continuous Japanese resistance against the penetration of foreign traders, in June 1863 US, Dutch, French and British ships bombarded the Japanese coast. After this united military aggression, which showed that at that time the foreign capitalist nations could still work together in the opening up of Japan, the Japanese ruling class renounced from any resistance against the foreign capitalists and quickly started to introduce profound political and economic changes.

In Japan the worm eaten feudal-absolutist order of the Tokugawa-Shogunate (the ruling feudal family) was replaced by a strongly united state under the government of the Meiji emperor in 1868. “Capitalism did not come because a rising bourgeoisie vanquished the feudal class in a revolutionary struggle, but because a feudal class transformed itself into a bourgeoisie.”. Although there have been “forces for change from feudal absolutism in the direction of capitalism, they were too weak for a revolution”. (Anton Pannekoek, Workers Councils, "Japanese imperialism"). They had to rely on the opening up of capitalism from “outside”. The midwives helping to give birth to capitalism in Japan were the foreign capitalists, who gave a big boost to the rising Japanese bourgeoisie.

The transition from feudal to bourgeois society was not accompanied by a political revolution.

Unlike most Europeans countries, where private capital acted as the driving force in the economy and where liberalism propagated a laissez-faire policy, in Japan it was the Japanese State which was going to play a dominant role in the advancement of capitalism. In 1868 the emperor nominated the first planning commission. The Japanese ruling class started to study systematically the conditions of capitalist functioning in other countries with the aim of copying and applying them as efficiently as possible.1

Only a few ships were sufficient for the foreign capitalist nations to enforce their penetration in Japan. Unlike other countries of the far East, Japan was not occupied, no foreign armies settled on the islands.

At the same time, since Japan was a group of islands with almost no raw materials, it had to rely on the supply of raw materials from other countries. The country closest to Japan is Korea – behind which lie the Manchuria region of China and Russia. In the south there is another island Taiwan. While most of the European states quickly had to direct their zeal of conquest towards far distant areas (often in other continents as in Africa, Asia, South America) Japan found its zone of expansion in the immediate proximity. Only 10 years after being opened up by foreign capitalists, Japan fell upon Taiwan. In 1874 Japan occupied the southern tip of Formosa. But this first major attempt to expand alarmed Britain and China, which sent 11,000 troops to the southern part of Taiwan. At that time Japan did not yet have enough military power to engage in a larger combat and consequently withdrew from Taiwan.

Soon after that Japan started to turn its ambitions towards Korea. In 1885 Japan and China signed a treaty, according to which neither of the countries would send troops to Korea without the permission of the other country. Following this temporary 'stalemate', Japan decided to build a fleet which could control the Chinese Sea.

As we shall see, Japan embarked upon a first war with China in 1894 and 10 years later with Russia in 1904. Thus barely 3-4 decades after capitalism had started to establish in Japan, the country went to war with two of its rivals in the area.

Unhampered by any colonial power, Japan quickly became one itself, and even if it arrived late on the world market it quickly became the dominant force in the region, which had to expand forcefully and become the main challenger in the area.

As a consequence its military expenditure was constantly on the rise. At the end of the 19th century, Japan began to finance its army by credits which were fuelled by British and American funds. 50% of its foreign loans went into war and armaments. Government spending tripled between 1893–1903, and it doubled again during the course of the Russian-Japanese 1905 war. Its modern fleet was composed of battleships made in Great Britain, its canons were German Krupp-made guns. When Japan defeated China in the 1894 war, it allowed Japan to impose a tremendous financial burden on its neighbour, forcing it to pay 360 million yen, large parts of which only served to finance a war program of armament expansion. The national debt rose from 235 million yen in 1893 to 539 million in 1903, it then soared to 2,592 million yen in 1913 as a result of large war bond issues. 2

Thus Japan had become the biggest imperialist shark in the region already in the ascendant phase of capitalism. The country could not have gained this dominant position without the early central role of the State and its militarist orientation.

1 There was almost no private industry during the early phase of Japanese capitalism. The first Ministry of Industry was founded in 1870. At the beginning of the 1870s paper money was introduced. In 1872 the first railway way line was opened between Tokyo and Yokohama (i.e. 40 years after the first railways were operated in GB). The country roads, which were barricaded by the provincial potentates, had to open for general traffic. Road taxes were abolished. In 1869 the four classes, Samurai, peasants, traders and craftsmen were all declared equal, the difference of clothes amongst the classes were abolished, peasants were entitled to grow the crop they chose. For more information see: Anton Pannekoek: The Workers' Councils.

2 “Mainly as a result of the Sino-Japanese war, and of growing armament and colonial enterprise which followed in its wake, the expenditures of the national government tripled from 1893-1903. Again, they more than doubled in the course of the Russo-Japanese war (...) To finance this burden taxes were progressively boosted... The indemnity of 360 million yen secured from China in 1895 was also largely used to finance an interwar program of armament expansion. These resources proved inadequate, however, and resort was had to extensive borrowing. The national debt rose from 235 million yen in 1893 to 539 million in 1903. It then soared to 2592 million yen in 1913... Nearly 50% of the government‘s entire budget in 1913 was devoted to the Army and Navy, military pension and war debt service... In fact, the “extraordinary” military expenditures charged to the war with Russia were largely balanced by borrowings in London and Paris. Before the war (i.e. in 1903) the outstanding total of Japan’s national loans issued abroad amounted to only 98 million yen. By the end of 1913 it had climbed to 1525 million (...) foreign loans had an inflationary effect within the country.”

(William Lockwood, The Economic Development of Japan, p. 35, Princeton, 1954), see also: W.W. Lockwood, The State and Economic Entreprise in Japan, Princeton, 1969)

Historic events:

Geographical:

- Japan [2]

China: a decomposing society prised open by opium and war

- 3590 reads

When being opened up by capitalism, both Japan and China were ruled by declining dynasties. As in Japan, the local mode of production in China was also unable to compete with capitalism. Neither on a commercial, nor above all on a military level was the ruling Manchu dynasty able to resist foreign capitalist penetration. As in Japan, the triumphant march of capitalism did not come through the imposition of a trading capitalist class from within the country, but capitalism was mainly imposed from outside.

Within the framework of this article we have no space to go at greater length into the reasons for this profound stagnation of Chinese society. In the 1850s, Marx and Engels started to analyse the deeper roots of this phenomena. “China, one of those faltering Asian empires, which one after the other fell prey to the entrepreneurial spirit of the European race, was so weak, so much collapsed, that it did not even have the strength to go through the crisis of a people’s revolution, so that an acute indignation has turned into a chronic and probably incurable disease, an empire, so much decomposed, that it was almost unable to rule its own people or to offer resistance to the foreign aggressors".1

Within the framework of this article we have no space to go at greater length into the reasons for this profound stagnation of Chinese society. In the 1850s, Marx and Engels started to analyse the deeper roots of this phenomena. “China, one of those faltering Asian empires, which one after the other fell prey to the entrepreneurial spirit of the European race, was so weak, so much collapsed, that it did not even have the strength to go through the crisis of a people’s revolution, so that an acute indignation has turned into a chronic and probably incurable disease, an empire, so much decomposed, that it was almost unable to rule its own people or to offer resistance to the foreign aggressors".1

In his works, Marx, in order to understand the reasons why major non-European civilisations did not evolve towards capitalism, put forward the concept of an Asiatic mode of production.2

Two opium wars played a vital role in the opening of China for capitalism.

After opium was massively imported by the British East Indian company in the early 19th century, the Chinese ruling class for fear of losing competitiveness in relation to its rivals, tried to curb the consumption of opium in the late 1830s. No less than twenty million people were addicted to the vice at the time. Many state officials were addicted to opium. The high level of consumption in itself was already an expression of a decomposing society.

The most advanced European capitalist country, Britain, (later with French participation) used the resistance of the Chinese ruling class against the massive ‘invasion’ of opium as a pretext for sending its troops. Britain, the ‘most civilised’ nation of the west became the biggest opium dealer and used the prohibition of drugs through the Chinese authorities as a means for unleashing two wars.

In two opium wars (1839-42, 1856-60) Britain, (with France at its side in the second war) imposed a crushing military defeat accompanied by a series of massacres against the Chinese troops.

As a result of the overwhelming British military victory in the first opium war, Britain was granted concessions over Hong Kong and five trade zones along the coast. But the second opium war brought already a qualitative change. By then above all the European countries aimed at finding new markets for goods manufactured in Europe. Thus as a result of the second war the Europeans opened up China not only for opium, but above all for European trade products.

“Complete isolation was the prime condition of the preservation of Old China. That isolation having come to a violent end by the medium of England, dissolution must follow as surely as that of any mummy carefully preserved in a hermetically sealed coffin, whenever it is brought into contact with the open air.” (Marx “Revolution in China and Europe) 14.6.1853, New York Daily Tribune) And Marx pointed out: “We hear nothing of the illicit opium trade, which yearly feeds the British treasury at the expense of human life and morality.”3

And as elsewhere the imposition of capitalism was accompanied by violence. “Of the more than 40 Chinese treaty ports each one of them has been bought with rivers of blood, massacres and ruin” (Rosa Luxemburg, Accumulation of Capital, p. 342). The foreign capitalists (under the slogan of free trade and accompanied by opium and war) tore down the restrictions of Manchu ruled China to enable capitalist development. Unlike Japan, which was also opened up violently through foreign capitalist countries, but which was never occupied or pulled into a series of wars, China was to be split up into spheres of influence.

During the period of the 1860/70s, all the outlying parts of the Chinese empire were grabbed by foreign powers. And towards the end of the 19th century China had lost entire Indo-China to France, Burma to GB, Korea to Japan, all territories north of the Amur river to Russia, Turkistan and Mongolia had been practically annexed by Russia, Tibet by Britain, Manchuria was disputed by Russia and Japan, even China proper was as good as annexed.

At the end of the 19th century Britain laid a heavy hand on the entire Yangtze Valley, the centre of economic life of China, France appropriated Hunan, Germany seized Shantung and Tsingtao. The USA did not require any concession; they acted as a supporter of an "open door policy" towards China.

Inside China had grown a sort of small "imperium in imperio" in the shape of foreign settlements. Small areas of Chinese territory had assumed the character of so many outposts of imperialism.

Whereas India was under British rule alone (once the British had defeated the French in 1757) China quickly became some sort of colony of international imperialism, with different countries trying to grab pieces. But due to the presence of so many aspirants, the possibility of annexation of China by any one single power being out of the question, colonisation of China took the form of creating „spheres of influence“. The resistance to the out and out annexation of China could no longer come from China itself, formal annexation was prevented by the rivalry amongst the imperialist powers.

Still, until the early 1890s the division of Chinese territory into zones of influence could proceed without major clashes amongst the European rivals.

However, once the level of imperialist rivalries especially amongst the European countries reached new proportions and they shifted their focus from Africa to Europe and Asia, the level of rivalries in the far East took on a new qualitative form.

The consequences of the penetration of foreign capitalist countries meant that while the foreign capitalist nations had imposed capitalism, at the same time a powerful development of Chinese capital was obstructed because the foreign national capitals were mainly interested in plundering and selling their goods at the expense of Chinese competitors. They hampered the development of an autonomous Chinese industry, barring the road to a real industrialisation. Thus while no Chinese faction of the ruling class was able to spark off a capitalist development, at the end of the 19th century foreign companies controlled almost the entire Chinese economy.

1 "The success of Russian policy in the far East", 1858, Marx-Engels-Werke 12, p. 622 (our translation from the German).

2 The analysis of pre-capitalist societies was taken up in several texts by Marx and Engels. As their investigations evolved, their concept also gradually changed. For a more detailed analysis see - Perry Anderson in his “Lineages of the Absolutist State”, London 1974. See see International Review n°135 for a discussion of this question.

3 "English cruelties in China", written 22.03.1857, published 10.04.1857

Historic events:

- Opium wars [3]

Geographical:

- China [4]

The Taiping rising – the bourgeoisie unable to make its own revolution

- 2479 reads

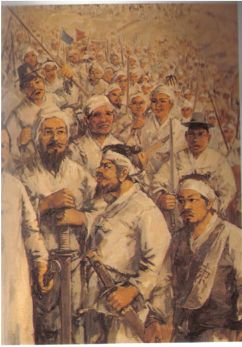

With a background of the demoralising results of the opium war, a collapsing social order, peasant revolts against famine and an unbearable tax burden, an irreversible collapse of the State machinery, and the penetration of foreign capitalist companies, both the peasantry as well as important factions of the property owning classes, who had no allegiance to the ruling Manchu dynasty, embarked upon a revolt in 1850 – which became known as the Taiping revolt.

Driven by a strong hatred against the exploitation by the Manchu dynasty, peasants threw themselves into revolts. Their movement merged with the aspirations of a young trading class, eager to promote trade and industry, which also wanted to get rid of the fetters of the Manchu dynasty.

Driven by a strong hatred against the exploitation by the Manchu dynasty, peasants threw themselves into revolts. Their movement merged with the aspirations of a young trading class, eager to promote trade and industry, which also wanted to get rid of the fetters of the Manchu dynasty.

Often instigated by secret societies, the revolts started off in the south of the country, spreading further north. The movement quickly received support from hundreds of thousands of peasants and opponents of the Manchu dynasty. Even a separate state was founded in 1851 - Taiping Tienkuo (“Heavenly empire of peace”), and a “heavenly Emperor” was proclaimed (Hung). The movement set up a monarchy with a strong theocratic tinge, directed against the power and privileges of the landed aristocracy. Expressing the aspirations of the peasantry to fight against its exploitation, private property was declared to be abolished, only collective financial management and grain storages were allowed, common ownership of land was proclaimed, farm land was collectivised and no longer considered as private property, taxes were lowered, equality of men and women was proclaimed, foot binding forbidden, free choice of husband/wife, the consumption of opium, tobacco and alcohol forbidden. Artisans produced articles which were distributed under the supervision of the State.

In 1852/53 the Taiping regime advanced its troops swiftly through Hunan and conquered Nanking, proclaiming the city as the capital of their state, which they maintained from 1853-1864. The Taiping rebels set up an army of more than 50,000 soldiers who controlled large areas of south and south eastern China. However, in 1864 the Taiping edifice collapsed. In a series of bloody wars, more than 20 million people got killed. British and French troops played a decisive role in the crushing of the movement by the Manchu dynasty. The Indian communist M.N.Roy rightly mentions some of the reasons for the defeat, when he wrote, “The weakness of the capitalist mode of production, the immaturity amounting to practical absence of the proletariat, which also resulted from the inadequate development of the capitalist mode of production, and lastly foreign intervention – all these contributed to the defeat of the first great movement which objectively tended towards the creation of a modern China”.1 Roy however saw too much revolutionary potential in this movement. In an earlier article2 we dealt with the limits of the Taiping movement. For reasons of space we cannot dwell on these in more detail.

Marx made the following assessment of the movement and its limits: “What is original about this Chinese revolution is its subject. They are not aware of any task, apart from the change of dynasty. They have no slogans. They are a still greater abomination for the popular masses than for the old rulers. Their destiny appears to be no more than to oppose conservative stagnation with a reign of destruction grotesque and loathsome in form, a destruction without any new or constructive kernel whatever (...) The Taiping rising is the offspring of a fossile social life”.3

Unable to throw off the weight of the decaying social order, unable to turn the penetration of capitalism which was being imposed by foreign countries into a powerful stimulation for a broader capitalist development, the ruling class in China could not make a bourgeois revolution, which would have paved the way for the unhampered development of capitalism. Thus China was made into a cripple in the 19th century – leaving the country with fetters that it was to carry over into the 20th century.

1 Roy, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in China, New Delhi, 1946, p. 113

2 International Review no 81 & 84

3 Marx: 7.7.1862 in Die Presse, “On China”

Historic events:

- Taiping revolt [5]

Geographical:

- China [4]

People:

- MN Roy [6]

The 1900 Boxer rising: an excuse for foreign intervention

- 2498 reads

The crushing of the Taiping revolt led to a drastic worsening of the situation of the peasants. In the context of an increased burden of taxation, the destruction of the livelihood for millions of peasants and artisans, who went down under the weight of the import of foreign goods, forcing them to come to the cities where there was only a very weak industrial development – these economic fetters contributed to the outbreak of what was later to become known as the Boxer uprising.

In May 1900 looting masses of dispossessed and frustrated peasants, led by a secret organisation of the Boxers blocked railway lines, ransacked factories and Western diplomatic missions. In an atmosphere of pogroms against foreigners, and in the absence of social and political demands, the Manchu dynasty took sides with the rioters, because their movement was not directed against any capitalist rule, but only against Christians and foreigners, offering no perspective whatsoever to the exploited classes.

In May 1900 looting masses of dispossessed and frustrated peasants, led by a secret organisation of the Boxers blocked railway lines, ransacked factories and Western diplomatic missions. In an atmosphere of pogroms against foreigners, and in the absence of social and political demands, the Manchu dynasty took sides with the rioters, because their movement was not directed against any capitalist rule, but only against Christians and foreigners, offering no perspective whatsoever to the exploited classes.

At the moment when all the foreign missions were threatened by looters, the foreign imperialists united their forces to quell the movement. At the same time, this common intervention posed the question of a pecking order amongst the imperialists, because it was clear whoever took the lead in repressing the rising could become the dominant force in Beijing. The scramble for the leadership in the repression of the movement revealed a new qualitative level of inter-imperialist rivalries.

As Rosa Luxemburg in Reform or Revolution had already stated in 1899: “If presently China is becoming the stage for threatening conflicts, the struggle is not only about the conquest of China for European capitalism but fully fledged antagonisms between European countries have been “transferred” to China and they now erupt on Chinese soil...”.1

Britain wanted Japan to take the lead because it hoped that Japan would act as a counter-weight to Russia. Russia strongly opposed Japanese intervention. In the end, Russia accepted the German proposal for a German led intervention, as neither Great Britain nor Japan would have agreed to Russian leadership.

But before the German troops reached Beijing, Russian troops had already started (and almost completed) the massacre. Thus Russia used the Boxer rising as a lever for increasing its influence in China. In October 1900 Russia occupied the whole of Manchuria, in order to counter the extended influence of Western European powers in China. But Russia was unable to block the penetration of European powers and Japan. In view of the danger of China being torn into pieces by the European powers, in particular vis a vis Russian attempts to grab large parts of the northern part of China, Germany and Britain in August 1900 negotiated with the goal of maintaining the territorial integrity of China and maintaining the principle of an “open door”. Britain was hoping to use the Germans against Russia in Manchuria, Germany in turn aimed at pushing Britain and Japan into hostilities against Russia. Following increased Russian presence, Japan and Britain signed an alliance in January 1902, with the aim of containing a Russian threat. While all European states agreed to a US proposal of an 'open door' towards China, Russia, which had most to lose from this proposal, voted against this. Soon afterwards the USA joined the British-Japanese alliance against Russia. Hence one of the permanent characteristics since the early 20th century has been the USA opposing a strengthened position for Russia and Japan. They have always posed as a 'defender' of the weaker country (in this case China) to prevent Russia and Japan from becoming too powerful.

As for China, following the crushed Boxer rising, the foreign capitalists forced the Chinese State to pay 450 million Tael "compensation payment" to the foreign countries, after having been forced to pay already a sum of 200 million Tael to Japan following the Chinese defeat in the war against Japan in 1894.

In 1911 the Chinese emperor was deposed and the first Chinese republic proclaimed. Formally the bourgeoisie had taken over the government to run the country. But while a bourgeois republic was now proclaimed, this did not mean that the country had gone through a bourgeois revolution, leading to the formation of a nation, able to compete on the world market. In reality, no ignition for a powerful industrial development occurred. Far from being a “united” nation, centrifugal tendencies gained the upper hand, as we shall see in the second part of this article.

Although formally in power the bourgeoisie was no longer a revolutionary class. Unable to push the country towards a big industrialisation, the ruling class could only push the whole nation into war and destruction.

1 (Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or revolution, chapter on customs politics and militarism, Gesammelte Werke, first volume, p. 397).

Historic events:

- Boxer rising [7]

Geographical:

- China [4]

Conflict over Korea

- 2225 reads

At the same time when European and US capitalism started to penetrate into Japan and China, these capitalist countries also tried to open up Korea.

There were many parallels in the development of Korea with China and Japan. In Korea, much as Japan, all contact with Westerners was fraught with peril. Only relations with China were permitted in the mid 19th century. Until the mid 1850s the only foreigners present in Korea were missionaries. As the capitalist nations started to show their presence in the region, any Korean activity against foreign citizens was taken as a welcome pretext to impose their presence by force. Thus when in 1866 French missionaries were killed in Korea, France sent a few military ships to Korea, but the French troops were beaten. In 1871 the USA sent several ships up the Taedong River to Pyongyang, but the US ships were also defeated.

However, during that phase there was yet no determination amongst the European countries or the USA to occupy Korea.

The USA was still under the impact of the civil war (1861-1865), and the westward expansion of capitalism was still in full swing in North America; England was engaged in putting down revolts in India and focussing its forces (with France) on penetrating into China. Russia was still colonising Siberia. So while the European countries were focussing their forces on China and other areas of the world, Japan seized its chance and quickly started to push for the opening of Korea for its commodities.

Through a show of force Japan managed to secure a treaty opening three Korean ports for Japanese traders. Moreover Japan, in order to thwart off Chinese influence, "recognised" Korea as an independent country. The declining Chinese empire could do nothing but encourage Korea to look for protection from a third state in order to resist pressure from Japan. The USA was amongst the first countries to recognise Korea as an independent state in 1882. In 1887 Korean forces for the first time turned to the USA asking for “support against foreign forces”, i.e. against Japan, Russia and Britain.

As Japan increased its exports, Korea became more and more dependent on trade with Japan. 90% of Korea’s exports went to Japan in the mid 1890s, more than 50% of its imports came from Japan.

The flood of foreign commodities which poured into the mainly peasant dominated country contributed sharply to the ruin of many peasants. The pauperisation in the countryside was one of the factors which provoked a strong anti-foreigner resentment.

Similar to the Taiping movement in China during the 1850-60s, a popular revolt – the Tonghak (“Eastern Learning”) unfolded in Korea in the 1890s (though it had seen precursors already in the 1860s), marked by a strong weight of peasant revolt directed against the penetration of foreign goods. There was as yet no working class presence in the movement, due to the very limited number of factories in the country.

Similar to the Taiping movement in China during the 1850-60s, a popular revolt – the Tonghak (“Eastern Learning”) unfolded in Korea in the 1890s (though it had seen precursors already in the 1860s), marked by a strong weight of peasant revolt directed against the penetration of foreign goods. There was as yet no working class presence in the movement, due to the very limited number of factories in the country.

Anti-feudal forces and peasants dominated the movement, which put forward a mixture of nationalist, religious and social demands.

Tens of thousands of peasants fought with primitive weapons against local rulers. The tottering ruling feudal class, feeling threatened by the Tonghak-movement and unable to suppress the movement alone, appealed to Chinese and Japanese forces to help them in repressing the movement.

The mobilisation for repressing the Tonghak movement by Chinese and Japanese forces was staged as a springboard for fighting over the control of the Korean peninsula. China and Japan clashed for the first time in modern history – not over the control of their respective territories, but over the control of Korea.

In July 1894 Japan started war with China, which lasted half a year. Most of the fighting took place in Korea, although Japan’s main strategic objective was not just control over Korea but also over the strategically important Chinese Liaotung Peninsula at the Chinese Sea.

The Japanese troops drove the Chinese army out of Korea, occupied Port Arthur(a Chinese port city on the Liatong peninsula in the Chinese Sea) , then the Liaotung peninsula, Manchuria – and started heading for Beijing. In the face of the strong Japanese superiority, the Chinese government asked the USA to broker a truce. As a result of the war, China had to concede Japan the Liaotung peninsula, Port Arthur, Dairen, Taiwan and the Pescadore Islands, accept a compensation payment of 200 million Tael (360 million yen) and open Chinese ports to Japan. The Chinese “compensation” payment was going to fuel the Japanese arms budget, because the war had been very expensive for Japan, costing about 200 million Yen, or three times the annual government budget. At the same time this “compensation” payment was draining the resources of China even more.

But already then, following the first sweeping Japanese victory, the European imperialist sharks opposed a too crushing Japanese victory. They did not want to concede Japan too many strategic advantages. In a “triple-intervention” Russia, France and Germany opposed the Japanese occupation of Port Arthur and Liaotung. In 1895 Japan renounced from Liaotung. Still without any ally at the time, Japan had to withdraw (the British-Japanese treaty was only signed in 1901). Initially Germany, France and Britain wanted to grant loans to China, but Russia did not want China to become too dependent on European rivals and offered its own loans. Until 1894 Britain had been the dominant foreign force in the region, in particular in China. Britain did not want any Japanese expansion into China and Korea, but until then Britain considered Russia the biggest danger in the region.

While the Japanese war triumph over China meant that Japan now was considered by the other imperialist rivals as an important rival in the far East, it was striking that the main battlefield of the first war between China and Japan was Korea.

The reasons are obvious: surrounded by Russia, China and Japan, Korea’s geographic position makes it a springboard for an expansion from one country towards another. Korea is inextricably lodged in a nutcracker between the Japanese island empire and the two land empires of Russia and China. Control over Korea allows control over three seas – the Japanese sea, the Yellow sea and East China Sea. If under the control of one country, Korea could serve as a knife in the back of other countries. Since the 1890s, Korea has been the target of the imperialist ambitions of the major sharks in the area initially only three: Russia, Japan and China - with the respective support and resistance of European and US sharks acting in the background. Even if, in particular, the northern part of Korea has some important raw materials, it is above all its strategic position which makes the country such a vital cornerstone for imperialism in the region.

As long ago as the 19th century, for Japan as the leading imperialist power in the far East, Korea became the vital bridge towards China.

The China-Japanese war over Korea was going to deal a big blow to the Chinese ruling class, at the same time it was an important spark to Russian imperialist appetites.

However, it is impossible to limit the conflict to the two rivals alone, because in reality, this war illustrated the qualitative general sharpening of imperialist tensions.

Japan’s main gains on Chinese territory – for example the Liaotung Peninsula – were immediately countered by a group of European powers. By 1899 Britain had strengthened its position in China (Hong Kong, Weihaiwei, the island guarding the sea lanes to Beijing), it held a monopoly in the Yangtze valley, Russia had seized Port Arthur (see below) and Tailenwan (Dairen, Dalny), was encroaching upon Manchuria and Mongolia, Germany had seized the Kaochow Bay and Shantung, France was given special privileges in the Hunan Province. “The Chinese war is the first even in the world political era in which all the cultural states are involved and this advance of the international reaction, of the Holy Alliance, should have been responded to by a protest by the united workers parties of Europe”.1

The 1894 China-Japanese war in fact brought all the main imperialist rivals of Europe and the far East into conflict with each other – a process which was to gain more momentum, as soon as another European imperialist shark appeared in the far East.

1 (Rosa Luxemburg in a speech at the party conference in Mainz in Sept. 1900, in Rosa Luxemburg, Collected Works/Gesammelte Werke, vol 1/1, p. 801)

Historic events:

- Tonghak [8]

- Port Arthur [9]

Geographical:

The advance of Russian imperialism and the world wide sharpening of imperialist tensions

- 8861 reads

Russia’s drive for expansion pushed it towards central Asia and the far East. In the West its rivalries with Germany, France and GB were prevailing, around the Black Sea it clashed with the Ottoman Empire (in the Crimean war 1854-56 it had already confronted Britain and France), in central Asia it clashed with Britain, (Britain waged two wars over Afghanistan (1839-42, 1878-1880, in order to fend off Russian influence in Afghanistan). In the far East it had to come into conflict mainly with Japan and especially Britain – which was the dominant European imperialist force in the far East.

But the Russian expansion in the last quarter of the 19th century crystallised only a general drive of all capitalist nations for the conquest of new territories and markets on the whole globe.

In 1884 France occupied Annam (Vietnam) and blockaded Taiwan, Britain annexed Burma in 1885, the Berlin Conference settled the carve up of Africa in 1885.

As for the far East, with the appearance of Russia in this zone of conflicts, a new qualitative level was reached. With Russia as a European country directly challenging the increasing domination of Japan, this meant that any Russian move would automatically trigger off a whole chain of realignments amongst the European rivals, according to their rivalry or possible alliance with Russia.1

Following the opening of the Suez canal in 1869, and with the growing importance of the far East for the European imperialist rivals, Russia pushed ahead the construction of the Trans-Siberian railways in 1891. Unable to finance this gigantic project on its own, it had to borrow French capital. Japan, which aimed at expanding towards China and Korea, feared that any Russian advance towards the East might endanger its position.

Russia was advancing its pawns in the far East. Benefiting from Chinese weakening in its war with Japan in 1894, Russia signed a secret deal with China in 1896 claiming to act as a protecting force against Japan. In 1898 Russia conquered Port Arthur.

In order to counter the Russian advance and manoeuvres in the far East and central Asia, Britain proposed to Russia the division of China and the Ottoman Empire amongst themselves - Russia rejected this.

Since the rivalry between GB and Russia could not be settled, Russia had to try and "appease" Japan as long as it could. Following the failed arrangement between Russia and Britain, Russia tried to settle with Japan for respective zones of influence.

In 1902 negotiations started between Japan and Russia over their respective zones of influence in the far East. In essence Russia proposed to give Japan a free hand over Korea provided Japan would not use the peninsula as a staging base for military operations, Russia even proposed that territory north of the 39th parallel in Korea be declared a neutral zone which neither country would be permitted to station troops in, while Russia wanted control over Manchuria and other border zones to China (half a century later the country was divided at the same 38th parallel in the Korean war in 1953). Japan proposed to Russia that it take control over Korea and it would allow Russia to be in charge of the protection of railway lines (only!) in Manchuria, but not be given any territorial control.

But the negotiations showed that it had become impossible for Russia and Japan to try and divide their zones of interests without war.

Japan looked for allies. On January 30th 1902 Japan and Britain signed a treaty. They recognised the right of Japan and Britain to intervene in Chinese and Korean affairs, promised neutrality if one of the parties was at war over its zone of interest, and support in case of war against other countries. The treaty between Britain and Japan led Japan to believe that it could launch a war against Russia with the hope that no other country would support Russia since GB was threatening in the background. And the German government assured the Japanese government in case of a war between Russia and Japan, Germany would remain neutral. Germany was hoping if Russia started a war in the East, this would give Germany more room for manoeuvre against France – a Russian ally – and Britain.

By dealing at greater length with the complicated strategic details of these conflicts we wanted to show the development of extremely complex and strongly intertwined military rivalries, where it became clear that if one of the main antagonists moved, a whole chain reaction by other rivals was unleashed. All the countries were not only positioning themselves, but would also be involved in the unleashing of a lurking war.

1 During the first phase of Russian expansion towards the East, i.e. during the first half of the 19th century and even until the 1870’s the division of new territories could still sometimes be settled by the sale and purchase of new territories. For example, Russia sold Alaska to the USA at the price of 7.2 million US dollars in 1867. And even after Russia earlier on had occupied Xinjiang, the most western Chinese province, Russia sold this large area in 1881 to China.

Geographical:

The Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05: prelude to World War I

- 17664 reads

Following the Russian refusal to accept Japanese demands for control over Korea, on February 8th 1904 Japan attacked the Russian fleet in Port Arthur and Tchemulpo.

The Russian-Japanese war heralded some of the characteristics of the wars in decadence.1

The first war in the 20th century between two major powers led to an unheard of mobilisation of the two countries – involving new levels of human, economic and military resources:

The war exhausted the finances of the victorious country, creating a pile of debts for Japan. Government expenditure more than doubled during the war, its budget had run into a gigantic deficit.

In the defeated country, Russia, the war sparked off a proletarian rising in 1905, showing that only the proletariat can act as a spanner to the war. Rosa Luxemburg concluded at the 1907 Stuttgart congress of the 2nd International: “But the Russian revolution [of 1905] did not only emerge from the war, but it also served to interrupt the war. Otherwise czarism would surely have continued the war” (speech in the commission on “Militarism and international conflicts”: (Collected Works, volume 2, p. 236).

Although Japan was able to wrist off big territorial gains from Russia the new situation reached at the turn of the century showed that no country could enrich itself at the expense of the loser without interfering in the imperialist interests of the other rivals.

10 years before World War I the Japanese triumph over Russia, which had confirmed its leading position in the far East, caused a strong counter-reaction by its imperialist rivals.

This first major war in the 20th century – unfolding in the far East between Russia and Japan – confirmed what Rosa Luxemburg predicted at the turn of the 19th century. In 1899 she wrote in the Leipziger Volkszeitung: “With the division and the integration of Asia, European capitalism no longer has any new areas for its conquest at its disposal, after this the world will be divided and every part of the world will be claimed by one ruler. Sooner or later the new orient question will enter the same phase in which the old one ‚fossilised‘: Step by step, the European opponents will start moving closer towards each other so that in the end they will finally stop after having reached the point where they face each other head on. And the economic and political forces which have been set free, the highly developed big industry, the gigantic militarism, will then start to be a terrible burden on the whole of society, because they will no longer find any outlet.”.2 Only 9 years later World War I confirmed this new level of imperialist relations.

This first major war in the 20th century – unfolding in the far East between Russia and Japan – confirmed what Rosa Luxemburg predicted at the turn of the 19th century. In 1899 she wrote in the Leipziger Volkszeitung: “With the division and the integration of Asia, European capitalism no longer has any new areas for its conquest at its disposal, after this the world will be divided and every part of the world will be claimed by one ruler. Sooner or later the new orient question will enter the same phase in which the old one ‚fossilised‘: Step by step, the European opponents will start moving closer towards each other so that in the end they will finally stop after having reached the point where they face each other head on. And the economic and political forces which have been set free, the highly developed big industry, the gigantic militarism, will then start to be a terrible burden on the whole of society, because they will no longer find any outlet.”.2 Only 9 years later World War I confirmed this new level of imperialist relations.

The consequences of the Russian-Japanese war went far beyond the two warring countries.

The USA, which just half a century earlier (in the mid 1850s) had spearheaded the opening of Japan for capitalism, started to confront a Japan which was colliding with the USA over the dominant position in the Pacific and the far East.

While after the 1894-95 war between China and Japan, the “triple intervention” by France, Germany and Russia prevented 'excessive' conquests by Japan, this time round it was the USA and GB which opposed a too crushing victory and too big a strengthening of the Japanese position.

While the USA and Britain supported Japan at the beginning of the war, they withdrew financial support towards the end of the war to put pressure on Japan, since the USA considered Japan more and more as their main rival in the far East. And when the USA supported the Russian-Japanese “peace deal”, which admitted Japanese hegemony in Korea, Japan had to concede to the USA their right of intervention in the Philippines. At the same time the USA considered that Japanese control over Korea was a means of preventing further Russian expansion towards the East. Still, the USA which was “trailing” behind the European countries during their 19th century imperialist conquests, because it was still busy with fostering the expansion of capitalism in its own Western part, had arrived “late” in the division of shares in the far East. The first US “gain” were the Philippines, which they grabbed from Spain in 1898 in the first war during that period waged for the re-division of existing conquests (it was the first war that the USA waged outside of their own territories). During that period the USA annexed Hawaii and gained control over Wake, Guam in the Pacific.

While the European countries and Japan appeared as the "aggressors" towards China, the USA could pretend to act as China's "defender".

1 The war lasted 18 months. The main battle zones were Port Arthur, the railway line and the road leading to Mukden and Liaoyang. In the siege of Port Arthur more than 60,000 Japanese soldiers died. The biggest battle was that for Mukden, from 23rd February until the 16th March 1905 – more than 750,000 soldiers participated in the battle. More than 40,000 Japanese soldiers died. It was both a naval war and a war between territorial armies. Russia sent a large part of its fleet (40 ships) from the Baltic Sea in October 1904 along the African coast to the Chinese waters. But the Russian navy arrived only in May 1905 in far Eastern waters. In a big sea battle, the well prepared Japanese navy inflicted Russia a crushing defeat, in which most of the Russian ships were drowned by Japanese forces.

Russia had to concede southern Sakhalin, southern Manchuria and Korea to Japan, Japan received Port Arthur and Dairen. As a result, five years later, Japan could declare Korea its colony.

2 Rosa Luxemburg, Collected Works, Vol. 1/1, p. 364, 13.3.1899.

Historic events:

- Port Arthur [9]

- Tchemulpo [12]

- Russo-Japanese war [13]