February 2010

- 2990 reads

Avatar: the only dream capitalism can sell, is a world without capitalism

- 5431 reads

James Cameron's Avatar is turning into something of a sensation. Everything about it is extravagant: filmed in 3D, computer generated images of unprecedented sophistication (the production platform data storage apparently reached one petabyte[1]) - everything about this film is extravagant, including the cost. And like any work of art, Avatar offers us a certain image of the society in which we live.

The film's story is blindingly simple. On the planet Pandora, a powerful Earth corporation has discovered deposits of a rare and precious mineral; it despatches on site machines and workers (who remain invisible throughout) to open a mine. The only problem, is that the planet, covered by a magnificent virgin forest, is already inhabited by a humanoid people, blue-skinned and three metres high, who have no intention of being kicked out without fighting back. The mining company is thus accompanied by an armed force which looks remarkably like the American army, along with bombers and helicopters and "mekkas" straight out of a Japanese manga. Any resemblance to the conquest of America, the rape of Vietnam, or the pillage of the environment being carried out today in the Amazon is of course anything but accidental. In the hope of convincing the natives - the "Na'avi" - to let themselves be moved on without bloodshed, and above all without bad publicity, the company has also sent a research team equipped with technology allowing them to create Na'avi bodies - "avatars" - which are "inhabited" by the minds of human "pilots" who remain in the shelter of their base camp. The avatars can thus move freely on the planet's surface (the atmosphere is poisonous for humans) in order to "win the confidence" of the natives. One of these "pilots", the ex-marine Jake Scully whose human body is stuck in a wheelchair, falls in love with a beauty from the local tribe (a sort of blue Pocahontas) and joins her people to lead the struggle against the invaders.

So much for the story - what about the film as a whole? Visually, you can't complain. Not only is the CGI perfectly convincing (the Na'avi look as "real" as the humans), the designers have really let their imaginations go to create a whole Pandorian exo-biology, with a vast fresco of plants, animals, and even insects, all with a coherence and an attention to detail which recalls some of Miyazaki's best anime films. It's impossible not to be captivated when the Na'avi take off on their great flying reptiles and when we - thanks to the depth of 3D projection - can realise one of humanity's oldest dreams and fly alongside them.

It's just as well that the film is visually impressive, because the plot is a wretched mish-mash of rip-offs from other films. The "noble savages" living in harmony with nature (Green), the decent whites who try to stop the massacre (a frequent theme in the Western genre), the stranger who falls in love and seeks the acceptance of the tribe (Dances with Wolves), the insensitive and brutal military commander (Apocalypse Now, but without the madness and the culture), the female scientist in a macho world (Sigourney Weaver reprises her role in Alien) - nothing's been left out. Even the ending, where the whole ecosystem is set in motion to repel the invader, is filched from Harry Harrison's Deathworld novels. What interest can there possibly be in such a film?

In fact, this film is interesting not for the story - banal - nor for the characters - cardboard cut-outs - but for its themes. Who are they aimed at? What ideology are they plugging?

Before being a work of art, Avatar is above all an enormous financial investment (between $250 and $300 million) which has to make a profit. This, moreover, is impossible merely by relying on the US market: according to an article in The Economist of 28th November, two thirds of the profits from a blockbuster come from outside the United States. To succeed, the film must therefore appeal to emotions which are widespread in the world population, or at least among the youth of the industrialised world. In this sense, the Situationists of the 1960s were right to say that the "society of the spectacle" (ie capitalism) stages our own dreams in order to sell them back to us.

In terms of sales, Avatar has undeniably been a success, having already earned more than $1 billion in ticket sales. It is striking that it has been a huge hit in France and Germany, the two European countries where opposition to the war in Iraq was especially strong. One reason is undoubtedly the unflattering image (to say the least!) that the film offers of the US Marines, and even more the fact that they take a pasting and are forced to leave with their tails between their legs.

That said, James Cameron manages to make it up to his American audience. At the beginning of the film we learn that the soldiers in question "used to be marines, fighters for freedom", but that they have become mercenaries since; the hero is himself an ex-Marine. One can therefore blame their brutal militarism, not on the state and its loyal servants, but on the private armies like those currently deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan by the "security firms" which provide logistics and "protection" to big companies like Halliburton, but also, and increasingly, directly to the US army.

As far as the "good guys" are concerned, the Na'avi obviously represent humanity's old dream of a life once more in accord with nature. They hunt, but they kill their prey with respect, they manage to live peacefully in the forest despite its dangers. Cameron doesn't bother with metaphysics - the ties between the Na'avi and the natural world depend on the fact that the planet is itself a living creature (an idea pinched from Stanislas Lem's novel Solaris, recently made into a film by George Clooney) and all the planet's inhabitants are equipped with a sort of bionic USB key that allows them to "plug in" to other animals and plants. The film is a long string of improbabilities. The male Na'avis are blue Apaches and "great warriors", though it's hard to see how since they had nobody to fight before the humans came. The females are the males' equals - they even go hunting - which doesn't stop them being stuck in "feminine" roles (there are no female warriors for example). And so on and so on.

But it works! The film ends with a burst of adrenalin and the audience is delighted to see the natives kick the mining company off the planet (probably the most unlikely part of the whole story!).

It's sheer fantasy of course. Nonetheless it is interesting to compare this fantasy, which has hit the screens in the midst of an economic catastrophe, with those created during the last crash. In the 1930s, a large part of Hollywood's output was devoted to films full of playboys, millionaires, and adventurers - the world of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. That dream no longer works. In Avatar, big business is definitely the bad guy. Today, the dream that pulls in the biggest profits for the capitalist fantasy machine, is the dream of a world from which capitalism has been definitively banished.

Jens, 21/01/2010

[1] 1 petabyte = 1,000 terabytes, 1 terabyte = 1,000 gigabytes

People:

- James Cameron [1]

Recent and ongoing:

- Film Review [2]

- Avatar [3]

A great loss to the ICC: death of our comrade Jerry Grevin

- 3369 reads

It is with the greatest sorrow that we have to inform our readers of the death of comrade Jerry Grevin (who also published under the initials JG) in the United States. He suffered from a sudden heart attack on the afternoon of Thursday February 11th and died immediately. For all the comrades, this comes as a terrible shock and especially for our American comrades who worked with him on a daily basis.

Many comrades have known comrade Jerry for more than 30 years and know his profound commitment and dedication to the cause of communism which began in his youth through his very active participation in the anti-Vietnam war movement, before he joined the ICC in the 1970s. In the ICC, the comrade has been at the heart of the life of the American section, including during the difficult period the ICC went through during the 1990's, and he has been a driving and enthusiastic force in the recent development of our contacts in the United States. All the comrades who knew Jerry also remember his zest for life and his sense of humour in the face of all the difficulties that life inevitably brings. The loss of comrade Jerry is not only a loss for the American section, it is a terrible loss for the whole ICC and for our class.

We will be publishing a longer tribute to the comrade in our press shortly. In the meantime we want to communicate our solidarity to all Jerry’s comrades, family and friends and our determination to carry on with the revolutionary work he believed in so passionately.

People:

- Jerry Grevin [4]

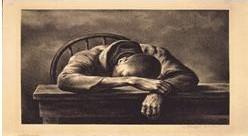

A soldiers tale

- 2549 reads

A soldiers tale

All the endless anticipation could not prepare you

All the training casually comes and goes

If you have been pulled and stretched in every way

Have been sent to the edge of the crevice

and been tempted to look down,

All the while feeling yourself on the crest of

grim madness and bloodthirsty insanity

If you've had to kill or be killed and so killed

in anger and hate and blind panic,

When friend and foe alike blur

with barely time to register or regret,

To try and duck something that could kill you

before you'd thought to duck

If you've had to carry someone in your hands

as their life dribbled away with every jerk and heave

Heard the last exhalations of two hundred

cursing and shouting the name of their most beloved

Maria or Mark or God

Have fought the protestations of your innards

ejecting themselves at the visceral scenes

(now safely locked away)

After all of this, and all of that -

what does a return to normality mean?

Graham

Recent and ongoing:

Anti-immigrant violence in Italy is a product of despair

- 2680 reads

At the beginning of January, in Rosarno, a town of 15,000 people in Calabria in the south of Italy, there were violent confrontations between local and immigrant workers. On 7 January, air gun pellets were shot at African immigrants in broad daylight. Two of them were seriously wounded. The pellets were fired by some ‘youths' but behind them was the hand of the ‘ndragheta', the Calabrian mafia. They are the region's bosses and pay the wages of local agricultural workers. For years, they have been making use of cheap African labour, which is in plentiful supply. These immigrant workers work for long hours and miserable wages[1], and at night are parked in an insalubrious former cheese factory. This year, however, this cheap labour force has become an encumbrance.

Firstly, the economic crisis is hitting Rosarno as it has hit the rest of the world. The oranges and mandarins are not selling; right now it's more profitable to leave them to rot on the trees than to harvest them. The majority of the African workers are therefore no longer useful and have lost their jobs. At the same time, new anti-immigrant legislation has been adopted in Italy: it reinforces the witch-hunt for illegal immigrants and penalises bosses for employing them. For the little work that's left, the mafia has therefore turned to ‘legal' immigrants from Eastern Europe (in particular from Ukraine and Romania). 1500 Africans and their families, who have come to Italy just to survive, are therefore caught between super-exploitation and unemployment. Anger and tension have risen bit by bit in their ranks: these semi-slaves, hitherto fairly docile, have begun to hold demonstrations. The ndragheta then decided to scare them into flight by firing on them. From beasts of burden, the immigrants are now prey.

However, instead of just lying down and taking all this, these workers went en masse onto the streets, burning bins and cars, smashing windows and wrecking buildings. In reaction, hundreds of local inhabitants, armed with iron bars and sticks, began a hunt for black skins, shouting "get back to Africa" and "we want to kill them". These confrontations left 67 wounded (31 immigrants, 19 policemen and 17 local inhabitants). It would seem that here again the mafia played a central role in stirring up the local population and putting themselves at the head of these improvised militias[2]. It was not difficult to instil such hatred in a population hit by poverty and unemployment, which officially affects 18% of the working class in this region.

But poverty alone is not enough to explain why a part of the population allowed itself to be pulled into a nauseating racist vendetta, or why the immigrants responded by smashing up stuff belonging to local people. In reality, the primary cause of these clashes "between poor people", as the international press put it - in other words, between workers - is despair, the total lack of any perspective: "It was a hell, we couldn't understand anything; it's true that we smashed everything we could, but it was because we are so angry. We are desperate, and if you add despair to anger, it's easy to go off the rails. When we got back to the cheese factory, we looked ourselves in the eyes and we were ashamed of what we had done. I cried the whole night thinking about the terrified people" (Godwin, a Ghanaian day-worker, 28 years old, quoted in La Repubblica, 9/1/10).

Only workers' struggles can restore confidence in the future, can allow people to see that a different world is possible, a world not of hatred but of solidarity. If we contrast these events with what happened recently in Britain, in the strikes in the oil construction industry, we can see how the struggle of the workers can begin to question nationalist divisions. In the unofficial strikes that broke out at Lindsey and elsewhere last year, despite all the slogans about "British jobs for British workers", which were promoted by the unions but which many workers took up themselves, we also saw the beginnings of a challenge to nationalist ideology, for example in the banners calling for Italian and Portuguese workers to join the strikes. Such developments in consciousness, even if they were only clearly expressed by a minority, were possible because the workers were fighting on their own class ground. The pogroms in Rosarno, the clashes between Italian and immigrant workers, were a pure expression of a society in decomposition; but when workers fight for their own demands, the way is open to overcoming all such divisions and offering real hope for the future.

Pawel/Amos 7/2/10

[1] The pay is one euro for a basket of mandarins and 6 cents for a kilo of oranges with a maximum wage of around 15 euro a day for 12 to 14 hours work

[2] Apart from the actual mafia, the cruelty and cynicism of the whole Italian bourgeoisie in these events should also be emphasised. The Berlusconi government has been profiting from them by launching a xenophobic campaign and justifying a whole series of anti-immigrant measures. The minister of the interior, Maroni, thus asserted "The situation in Rosarno is difficult, the result of a clandestine immigration that has been tolerated for all these years without anything effective being done ". In fact, the state, on the one hand, hunts down illegal immigrants and expels them in order to limit numbers, and, on the other hand, allows the bosses to exploit massively and shamefully (when it doesn't do it itself directly) a cheap labour force, thus improving ‘national competitiveness'. There are over 50,000 immigrant workers living in Italy in insalubrious housing similar to that in Rosarno. Getting back to the recent events and the ‘protection' offered by the state to immigrants who have been the victims of pogroms: when they intervened, the police injured a lot of the immigrants and afterwards, in order to ‘protect' them, found nothing better to do than push them into ‘retention centres' in order to ‘control their situation' and deport all those whose papers were not in order! This is the inhumanity that the bourgeoisie is capable of, whether it presents itself in the guise of the mafia or of very respectable high officials of the state!

Geographical:

- Italy [8]

Recent and ongoing:

- Lindsey oil refinery strike [9]

- Pogroms [10]

Homage to comrade José

- 2672 reads

We have recently heard of the death of José Ferran, an anarchist militant, a Spanish political refugee in the wake of the war in Spain between 1936 and 1939. We want to pay homage to this fighter of the working class, because, although he had deep disagreements with some of our political positions, he still maintained contact with the ICC for 30 years, taking part in our public forums and discussing with us at the Wazemmes market in Lille[1]. It's there that we saw him in public for the last time: at the age of 95, he came to buy our paper Révolution Internationale, which he did nearly every month, taking the opportunity to hold long discussion with us, especially about those of our positions that annoyed him the most, in particular the question of the state. The ICC militants who knew him will not forget these intense verbal jousts, these animated but always fraternal discussions with a sincere comrade who was so profoundly attached to his class.

[1] Later José had to go into a retirement home, and when we visited him there, he complained a lot about the residents' lack of political discussion and concerns!

People:

- José Perran [11]

Recent and ongoing:

- Obituary [12]