2005 - 120 to 123

- 7175 reads

International Review no.120 - 1st quarter 2005

- 4508 reads

3 - The theory of decadence at the heart of historical materialism, part iii

- 5595 reads

Battaglia Comunista abandons the marxist concept of decadence, part ii

In the first part of this article (Intenational Review n°119) we recalled that for marxism, and contrary to the view developed by Battaglia,[1] [1] the decadence of capitalism is not the eternal repetition of its contradictions on a growing scale, but poses the question of its survival as a mode of production, according to the terms used by Marx and Engels. By rejecting the concept of decadence as defined by the founders of marxism and subsequently taken up by the organisations of the workers’ movement, some of whom deepened it further, Battaglia is turning its back on a historical materialist understanding, which teaches us that for a mode of production to be transcended, it has to enter a phase of senility (Marx) where their relations of production become obsolete and become an obstacle to the development of the productive forces (Marx again). And when the latter tells us in the Principles of a Critique of Political Economy (the Grundrisse) that “the universality towards which it is perpetually striving finds limitations in its own nature, which at a certain stage of its development will make it appear as itself the greatest barrier to this tendency, leading thus to its own self-destruction”(translated from notebook IV of the chapter on capital, by David McLellan in Marx’s Grundrisse, 1971, p 112), there is no “fatalism” in this idea of “self-destruction” as Battaglia claims. This is because while the decadence of a mode of production is the indispensable condition for a “revolutionary reconstitution of society at large” (Marx, Communist Manifesto), it’s the class struggle which, in the last instance, cuts through the socio-economic contradictions. And if it is unable to do this, society then sinks into a phase of decomposition, into the “mutual ruin of the contending classes”, as Marx puts it right at the beginning of the Communist Manifesto. There is nothing automatic or inevitable in the succession of modes of production, nothing that leads to the conclusion that, faced with increasingly insurmountable contradictions, capitalism will simply retire from the scene of history.

Battaglia's zig-zags in recognising the concept of decadence

During the discussion around the adoption of its platform at the first National Conference in 1945, the Central Committee of the reconstituted Partito Comunista Internazionalista (PCInt) gave one of its militants - Stefanini, a former leading member of the Italian Fraction of the International Communist Left (1928-45) - the task of presenting a political report on the union question. In this report he “reaffirmed this conception that the trade union, in the phase of the decadence of capitalism, is necessarily linked to the bourgeois state” (proceedings of the first National Conference of the PCInt). This report, presented on the third day of the conference, was in contradiction with the platform that had been discussed and voted on the previous day.[2] [2] Furthermore, a number of militants supported the position developed by Stefanini in the name of the Central Committee, although the latter, at the end of the discussion, still called upon the conference to adopt the position taken in the Platform,[3] [3] and felt it necessary to present a motion at the end of the conference calling for “the reconstruction of the CGIL”[4] [4] and “the conquest of the leading organs of the trade union” (ibid, motion of the Central Committee on the union question).

Furthermore, despite its explicit affirmation that it is in political and organisational continuity with the Italian Fraction,[5] [5] and despite the presence of members of the Fraction in the leadership of the new party, the Platform voted at this conference (in fact a founding congress) made no reference at all to what had been the cement, the political coherence of the positions of the Fraction: the analysis of the decadence of capitalism. At the same time the party nominated an International Bureau to coordinate its organisational extensions abroad; and these – with due respect for theoretical cacophony – continued to defend the analysis of the decadence of capitalism in their publications![6] [6] Which goes to show that with such a method of regroupment as its basis, there was a real programmatic heterogeneity on virtually all the political positions it adopted. When we read the proceedings of this conference, it is obvious that a profound political confusion reigned throughout![7] [7]

With such a confused political basis, it is not surprising that, like the Loch Ness monster, the notion of decadence keeps reappearing at one time or another. This was notably the case at the trade union conference of the PCInt in 1947, where, in contradiction with the 1945 Platform, it was stated that “In the current phase of the decadence of capitalist society the trade union is destined to serve as an essential instrument of the policy of conservation and thus to assume the precise functions of a state organism”.[8] [8] This explosive cocktail mixed at the very foundations of the PCInt did not stand the test of time for long; the party split into two parties in 1952, one around Bordiga (Programma Comunista), which marked a return to the political positions of the 1920s; the other around Damen (Battaglia Comunista), which referred more explicitly to the political contribution of the Italian Fraction.[9] [9] It was at the moment of this split that Bordiga was to develop certain critical considerations about the concept of decadence.[10] [10] However, despite the re-appropriation of certain positions of the Fraction, the analysis of decadence was still left out of the new political platform adopted by Battaglia after the 1952 split.

Some time afterwards, in its efforts towards the regroupment of revolutionary forces and in discussion with our organisation, Battaglia finally adopted the analysis of the decadence of capitalism in the context of the dynamic opened up by the International Conferences of the Groups of the Communist Left between 1976 and 1980.[11] [11] Battaglia published two long studies on decadence in its review Prometeo at the beginning of 1978 and in March 1979,[12] [12] as well as texts for the first two conferences.[13] [13] We thus saw Battaglia, on the back of its publications, adopting a new programmatic point which marked its acceptance of the framework of decadence: “the growth of inter-imperialist conflicts, trade wars, speculation, generalised local wars, are signs of the process of the decadence of capitalism. The structural crisis of the system is pushing capital beyond its ‘normal’ limits, towards a solution at the level of imperialist war”. After the death of Damen senior – the founder of the PCInt and the initiator of the cycle of conferences - in October 1979, this point on decadence disappeared from its basic positions starting with Prometeo n°3 in December 1979, i.e. just before Battaglia excluded us at the end of the third conference in May 1980. It was also significant that the analysis of decadence, which was at the centre of Battaglia’s contributions for the first two conferences, totally vanished from its contributions for the third conference, where we saw an analysis which prefigured the current position… all this in very discreet manner and without any explanation, either to its readers or the other groups of the proletarian political milieu! To conclude, we should also note that Battaglia now proposes to abandon something that it still affirmed in the 1997 platform of the IBRP: the existence of a qualitative break, marked by the First World War, between two fundamental and distinct historical periods in the evolution of the capitalist mode of production, even if this was no longer explained by using the marxist concepts of the ascendance and decadence of a mode of production.[14] [14]

After these multiple political zigzags, Battaglia has the cheek to complain about being “tired of discussing about nothing when we have work to do trying to understand what is happening in the world”:[15] [15] how can you not be tired when you are forever changing your spectacles and can never know which one is the best for “understanding what is happening in the world”! Today anyone can see that Battaglia has deliberately chosen long-sighted glasses even though it’s suffering from myopia.

At this point, the reader will have seen that far from being the expert in marxism it claims to be, Battaglia is adept at surfing the opportunity of the moment and looks more like a quick-change champion. And it’s not over yet. The latest zigzags take the biscuit. For those who read Battaglia’s prose, it is now evident that this organisation wants to rid itself once and for all of a notion which it considers, according to its own terms in a statement dated February 2002 and published in Internationalist Communist Review n°21,[16] [16] “as universal as it is confusing (…) alien to the critique of political economy (…) foreign to the method and the arsenal of the critique of political economy”. We are also asked “What role then does the concept of decadence play in terms of the militant critique of political economy, i.e. for a deeper analysis of the characteristics and dynamic of capitalism in the period in which we live? None. To the extent that the word itself never appears in the three volumes constituting Capital”.[17] [17] But then why on earth did Battaglia, two years later (in Prometeo n°8, December 2003) feel the need to launch a grand debate in the IBRP on this “confusing” concept which “can’t explain the mechanisms of the crisis”, which is “foreign to the critique of political economy”, which only appears incidentally in Marx and which is supposedly absent from his masterpiece? Yet another change of clothes. Did Battaglia suddenly remember that the first pamphlet published by its sister organisation (the Communist Workers Organisation) was entitled precisely The Economic Foundations of Decadence? The CWO quite rightly considers that “the notion of decadence is a part of Marx’s analysis of modes of production” and was at the heart of the creation of the Third International: “At the time of the formation of the Comintern in 1919 it appeared that the epoch of revolution had been reached and its founding conference declared this” (Revolutionary Perspectives n°32). Has Battaglia realised that it is not that easy to dispose of such a central acquisition of the workers’ movement as the marxist notion of the decadence of a mode of production?

Bearing this in mind, it is hardly surprising that in its contribution opening the debate, Battaglia has nothing to say about the definition and analysis of the decadence of modes of production developed by Marx and Engels, nor about their efforts to chart the circumstance and moment in which this happens to capitalism. Similarly, Battaglia imperiously ignores the position adopted at the foundation of the CI, analysing the First World War as the unequivocal sign of the beginning of the period of decadence for capitalism. Equally, Battaglia, which claims to be the political heir of the Italian Fraction, is silent about the fact that the latter made decadence the framework of its political platform. Thus, instead of taking position on the heritage left us by the founders of marxism and deepened by generations of revolutionaries, Battaglia prefers to hurl anathemas (the idea of fatalism) and spread confusion on the definition of decadence… and at the same time announce a debate within the IBRP and a major programme of research: “the aim of our research will be to verify whether capitalism has exhausted its push to develop the productive forces, and if this is true, when, to what extent, and above all why”. When you want to abandon a historic concept of marxism, it is easier to write on a blank page than to pronounce on the programmatic gains of the workers’ movement. This was exactly what the reformists did at the end of the 19th century. As for us, we await the results of this “research” with considerable impatience; and we will be happy to confront them with marxist theory and the reality of the present historical evolution of capitalism. But it should be said that the arguments that are already being used by Battaglia don’t augur very well. From this rapid historical survey of the different positions Battaglia has taken up on decadence we can already say that while the Juniors have replaced the Seniors, the opportunist method remains the same.

A return to the idealism of the utopian socialists

For Battaglia, as for the utopian socialists, the revolution is not the product of any historic necessity whose roots lie in the impasse of capitalist decadence, as Marx, Engels and Luxemburg taught us: “the universality towards which it is perpetually striving finds limitations in its own nature, which at a certain stage of its development will make it appear as itself the greatest barrier to this tendency, leading thus to its own self-destruction”(Marx, op cit) “The task of economic science is rather to show that the social abuses which have recently been developing are necessary consequences of the existing mode of production, but at the same time also indications of its approaching dissolution, and to reveal within the already dissolving economic form of motion, the elements of the future new organisation of production and exchange which will put an end to those abuses” (Engels, Anti-Dühring part II, ‘Political Economy: Subject Matter and Method’); “From the standpoint of scientific socialism, the historical necessity of the socialist revolution manifests itself above all in the growing anarchy of capitalism which drives the system into an impasse” (Luxemburg, Social Reform or Revolution, ‘The opportunist method’). For marxism, the “self-destruction” (Marx), “dissolution” (Engels) and “impasse” (Luxemburg) that come with the decadence of capitalism are an indispensable condition for going beyond this mode of production; but they do not at all imply its automatic disappearance, since “only the hammer blow of revolution, that is, the conquest of political power by the proletariat, can break down this wall” (Luxemburg, op cit, ‘Tariff policy and militarism’). The “Self-destruction” (Marx), “dissolution” (Engels), and “impasse” (Luxemburg) that come with the decadence of capitalism create the conditions for revolution, they are the granite base without which “socialism ceases to be an historical necessity. It then becomes anything you want to call it, except the result of the material development of society” (Social Reform or Revolution, ‘The opportunist method’). Just as the centuries of Roman and feudal decadence were necessary for the emergence of the objective and subjective conditions required for the dawn of a new mode of production, the impasse of the decadence of capitalism is what proves to the proletariat that this mode of production is historically reactionary. Contrary to what Battaglia thinks, “It is not true that socialism will arise automatically and under all circumstances from the daily struggles of the workers. Socialism will be the consequence only of the ever growing contradictions of capitalist economy and the comprehension by the working class of the suppression of these contradictions can only come about through a social transformation” (ibid, ‘Practical consequences and general characteristics of revisionism’).

Marxism does not say that the revolution is inevitable. It does not deny will as a factor in history: it demonstrates that will is not enough; that it is realised in a material framework which is the product of an evolution, a historical dynamic, which it has to take into account in order to be effective. The importance which marxism gives to understanding the “real conditions”, the “objective conditions” is not a denial of consciousness and will. On the contrary it is the only firm basis for affirming them. If capitalism “reproduces itself, posing, once more and at a higher level, all of its contradictions”, (Battaglia), where can we find the objective foundations for socialism? As Rosa Luxemburg reminds us, “According to Marx, the rebellion of the workers, the class struggle, is only the ideological reflection of the objective historical necessity of socialism, resulting from the objective impossibility of capitalism at a certain economic stage. Of course, this does not mean (it still seems necessary to point out to the ‘experts’) that the historical process has to be, or even could be, exhausted to the very limit of this economic impossibility. Long before this, the objective tendency of capitalist development in this direction is sufficient to produce such a social and political sharpening of contradictions in society that they must terminate. But these social and political contradictions are essentially only a product of the economic indefensibility of capitalism. The situation continues to sharpen as this becomes increasingly obvious. If we assume, with the ‘experts’ [like Battaglia], the economic infinity of capitalist accumulation, then the vital foundations on which socialism rests will disappear. We then take refuge in the mist of the pre-marxist systems and schools which attempted to deduce socialism solely on the basis of the injustice and evils of today’s world and the revolutionary determination of the working classes (…) The absolute and undivided rule of capital aggravates class struggle throughout the world and the international economic and political anarchy to such an extent that, long before the last consequences of economic development, it must lead to the rebellion of the international proletariat against the existence of the rule of capital” (The Accumulation of Capital, An Anti-critique, ‘The critics’ 1972 US edition).

It is not because the immense majority of human beings are exploited that socialism is today a historical necessity. Exploitation reigned under slavery, feudalism and under capitalism in the 19th century without socialism having the least chance of being realised. For socialism to become a reality, it is not only necessary for the means of installing it (working class and means of production) to be sufficiently developed. It is also necessary that the system which it has to replace – capitalism – has ceased being a system indispensable to the development of the productive forces and has become a growing obstacle to it, i.e. that it has entered its phase of decadence: “The greatest conquest in the development of the proletarian class struggle was the discovery that the point of departure for the realisation of socialism lies in the economic relations of capitalist society. As a result, socialism was changed from an ‘ideal’ dreamed by humanity for thousands of years to an historical necessity” (Social Reform or Revolution, ‘Economic development and socialism’). The inevitable error of the utopians resided in their view of the march of history. For them, its outcome could be decided by the good will of certain groups of individuals: Babeuf or Blanqui put their hopes on small groups of determined workers; Saint-Simon, Fourier or Owen even addressed themselves to the benevolence of the bourgeoisie for carrying out their projects. The appearance of the proletariat as an autonomous class during the revolution of 1848 was to show that socialism could only be accomplished by a class. It confirmed the thesis that Marx had already set out in the Communist Manifesto: since the division of society into classes, the history of humanity has been the history of the class struggle. From then on the evolution of society could only be understood within the framework which determined these struggles, i.e. in the evolution of the social relations which link men together and divide them into classes for the production of their means of existence: the social relations of production. To know whether socialism is possible you therefore have to decide whether or not these social relations of production have become a barrier to the development of the productive forces and thus demand the replacement of capitalism by socialism. For Battaglia, on the other hand, whatever the global historic context in which capitalism is evolving, “The contradictory aspect of capitalist production, the crises which are derived from this, the repetition of the process of accumulation which is momentarily interrupted but which receives new blood through the destruction of excess capital and means of production, do not automatically lead to its destruction. Either the subjective factor intervenes, which has in the class struggle its material fulcrum and in the crises its economically determinant premises, or the economic system reproduces itself, posing, once more and at a higher level, all of its contradictions, without creating in this way the conditions for its own self-destruction” (Revolutionary Perspectives n°32).Thus the class struggle, combined with an episode of economic crisis, is enough to open up the possibility of a revolutionary outcome: “Despite capitalism's undoubted success at containing the class struggle its contradictions persist. As Marxists we know they cannot be contained for eternity. The explosion of these contradictions will not necessarily result in victorious revolution. In the imperialist era global war is capital's way of 'controlling', of temporarily resolving, its contradictions. However, before this happens the possibility remains that the bourgeoisie's political and ideological grip on the working class may be broken. In other words, sudden waves of mass class struggle may occur and revolutionaries have to be prepared for these. When the class once again takes the initiative and begins to use its collective strength against capital's attacks, revolutionary political organisations need to be in a position to lead the necessary political and organisational battles against the forces of the left bourgeoisie”.

For Battaglia there is no need to decide whether the social relations of production have become historically obsolete, no need for the opening up of a period of decadence, because the system “receives new blood through the destruction of excess capital and means of production”, and, after each crisis “ the economic system reproduces itself, posing, once more and at a higher level, all of its contradictions”.

The conditions needed for revolution

The fact that Marx was able to say that “all this shit of political economy ends up in the class struggle”, even though he spent a good part of his life on the critique of political economy, shows that while it is the class struggle that provides the decisive factor, the motor of history, he still accorded a great deal of attention to its objective foundations, to the economic, social and political context in which it unfolds. To repeat this after him, like Battaglia does, is just to kick an open door because no one, from Marx himself to the ICC, claims that only one of these factors (economic crisis or the class struggle) is enough to overthrow capitalism. On the other hand, what Battaglia does not understand is that, even together, these two factors remain insufficient! The point here is that periods of economic crisis linked to class conflicts have existed since the first days of capitalism, without in any way opening up the possibility of overthrowing capitalism. What Marx showed through historical materialism is that at least three conditions are indispensable: an episode of crisis, class conflicts, but also the decadence of a mode of production (in this case capitalism). This is what the founders of marxism understood very well: after thinking on a number of occasions that capitalism had had its day, they were able to revise their diagnosis each time (for a brief history of the analysis Marx and Engels made of the conditions and moment of the arrival of decadence we refer the reader to n°118 of the International Review). Engels was to conclude this inquiry in his 1895 introduction to Marx’s The Class Struggles in France, when he writes that “History has proved us, and all who thought like us, wrong. It has made it clear that the state of economic development on the Continent at that time was not, by a long way, ripe for the removal of capitalist production; it has proved this by the economic revolution which, since 1848, has seized the whole of the Continent (...) this only proves, once and for all, how impossible it was in 1848 to win social reconstruction by a simple surprise attack”.

But that’s not all, because what Battaglia has never understood is that a fourth condition is required for the outbreak of a period favourable to victorious insurrectional movements: the opening of a historic course towards class confrontations. In the 1930s, the first three minimal conditions (economic crisis, social conflicts and the period of decadence) were present, but they were present in a historic course leading towards imperialist war. Understanding this was the major contribution of the Italian Fraction. In coherence with the analysis of the Communist International which defined the period opened up by the First World War as “the era of wars and revolutions”, it was the Fraction which developed the analysis of the historic course towards class confrontations or towards war. The Gauche Communiste de France (1942-1952) – and after that the ICC – took up and developed this analysis but they were not its progenitors as Battaglia untruthfully claims: “The schematic conception of historic periods – itself historically belonging to the French Communist Left to which the ICC owes its existence – characterises historic periods as revolutionary or counter-revolutionary on the basis of abstract deliberations about the condition of the working class” (Internationalist Communist n°21). This falsification of birth certificates allows Battaglia to dishonestly throw discredit on our political ancestors while at the same time claiming the inheritance of the Italian Fraction without really having to pronounce on its essential theoretical contributions.

The necessity for a historical framework for elaborating class positions

“Has capitalism outlived itself? Or to put it differently: Is capitalism still capable of developing the productive forces on a world scale and of heading mankind forward? This is a fundamental question. It is of decisive significance for the proletariat…” (Trotsky, Europe and America, 1926). This question is indeed fundamental, decisive for the proletariat as Trotsky says, because working out whether a mode of production is ascendant or decadent means knowing whether it is still progressive for the development of humanity or whether historically speaking it has had its day. Knowing whether capitalism still has something to offer the world or whether it has become obsolete implies consequences that are radically different as regards the strategy and political positions of the proletariat. Trotsky was well aware of this when he continued his reflections about the nature of the Russian revolution: “If it turned out that capitalism is still capable of fulfilling a progressive historical mission, of increasing the wealth of the peoples, of making their labour more productive, that would signify that we, the Communist Party of the USSR, were premature in singing its de profundis; in other words, it would signify that we took power too soon to try to build socialism. Because, as Marx explained, no social system disappears before exhausting all the possibilities latent in it”. Those who are abandoning the theory of decadence should meditate on these words of Trotsky because they will end up concluding that the Mensheviks were right, that it was indeed the bourgeois revolution that was on the agenda in Russia and not the proletarian revolution, that the foundation of the Communist International was based on an illusion, that the methods of struggle which were applicable in the 19th century are still valid today and so on. Trotsky, as a consistent marxist, replied without hesitation: “But the war itself was not an accidental phenomenon. It was the blind revolt of the productive forces against capitalist forms, including those of the national state. The productive forces created by capitalism could no longer be contained within the framework of the social forms of capitalism” (ibid). This diagnosis – the end of the historically progressive role of capitalism and the significance of the First World War as marking the passage from its ascendant to its decadent phase – was shared by all the revolutionaries of that time, including Lenin: “From the liberator of nations which it was in the struggle against feudalism, capitalism in its imperialist stage has turned into the greatest oppressor of nations. Formerly progressive, capitalism has become reactionary; it has developed the forces of production to such a degree that mankind is faced with the alternative of adopting socialism or of experiencing years and even decades of armed struggle between the 'Great' powers for the artificial preservation of capitalism by means of colonies, monopolies, privileges and national oppression of every kind” (Socialism and War, ‘The present war is an imperialist war’. Collected Works, Vol 21, p.301-2).

If, in Battaglia’s terms, you argue that capitalism “reproduces itself, posing, once more and at a higher level, all of its contradictions”, not only are you turning your back on the materialist, marxist foundations of the possibility of revolution as we have just seen, but you also prevent yourself from understanding why hundreds of millions of human beings will decide one day to risk their lives in a civil war to replace this system with another, because, as Engels says: “So long as a mode of production still describes an ascending curve of development, it is enthusiastically welcomed even by those who come off worst from its corresponding mode of distribution. This was the case with the English workers in the beginnings of modern industry. And even while this mode of production remains normal for society, there is, in general, contentment with the distribution, and if objections to it begin to be raised, these come from within the ruling class itself (Saint-Simon, Fourier, Owen) and find no response whatever among the exploited masses” Anti-Dühring Part II, ‘Political Economy: Subject matter and method’). Whereas when capitalism enters its phase of decadence, we have the material and (at certain moments) the subjective bases for the proletariat to find the conditions and the reasons to make the insurrection. Thus Engels continues as follows: “Only when the mode of production in question has already described a good part of its descending curve, when it has half outlived its day, when the conditions of its existence have to a large extent disappeared, and its successor is already knocking at the door — it is only at this stage that the constantly increasing inequality of distribution appears as unjust, it is only then that appeal is made from the facts which have had their day to so-called eternal justice. From a scientific standpoint, this appeal to morality and justice does not help us an inch further; moral indignation, however justifiable, cannot serve economic science as an argument, but only as a symptom. The task of economic science is rather to show that the social abuses which have recently been developing are necessary consequences of the existing mode of production, but at the same time also indications of its approaching dissolution - and to reveal within the already dissolving economic form of motion, the elements of the future new organisation of production and exchange which will put an end to those abuses” (ibid).

This is what Battaglia, by abandoning the concept of decadence, is now starting to forget: its “economic science” no longer serves to show “the social anomalies”, “the indications of the approaching dissolution” of capitalism, which is what the founders of marxism exhorted us to do; it serves instead to repackage leftist and alternative worldist prose about the survival of capitalism through the use of finance capital, the recomposition of the proletariat, the “new industrial revolution” based on the microchip etc “The long resistance of western capital to the crisis of the accumulation cycle (or to the concretisation of the tendency to the rate of profit to fall) has up until now avoided the vertical collapse which has hit the state capitalism of the Soviet empire. Such a resistance has been made possible by four fundamental factors: (1) the sophistication of financial controls at an international level; (2) a profound restructuring of the productive apparatus which has brought about a dizzying rise in productivity…(3) the consequent demolition of the previous class composition, with the disappearance of the tasks and roles that have become out of date and the appearance of new tasks, new roles and new proletarian forces (…) The restructuring of the productive apparatus has arrived at the same time as what we can call the third industrial revolution experienced by capitalism…the third industrial revolution is marked by the microprocessor” (Prometeo n°8, ‘Draft theses of the IBRP on the working class in the current period and its perspectives’).

When Battaglia did defend the concept of decadence, it affirmed very clearly that “Two world wars and the present crisis are the historical proof of what the continued existence of an economic system as decadent as capitalism means at the level of the class struggle”,[18] [18] whereas having abandoned it, it now thinks that “the solution of war appears as the principal means of resolving capital’s problems of valorisation” and that wars have the function of “regulating relations between different sectors of international capital”, or, as it says in the IBRP platform of 1997 “global war can represent for capital a momentary way of resolving its contradictions”

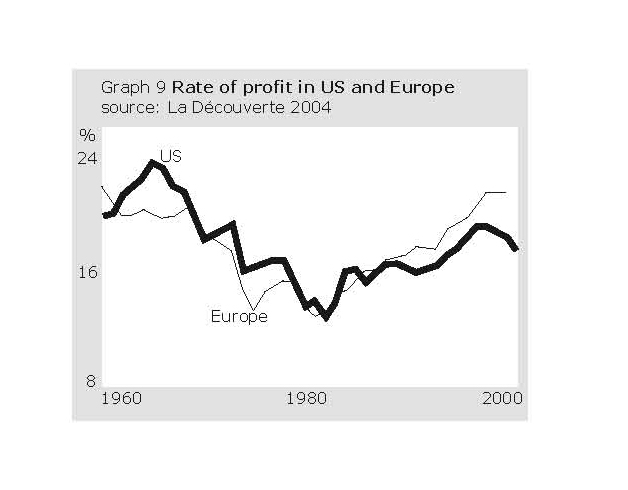

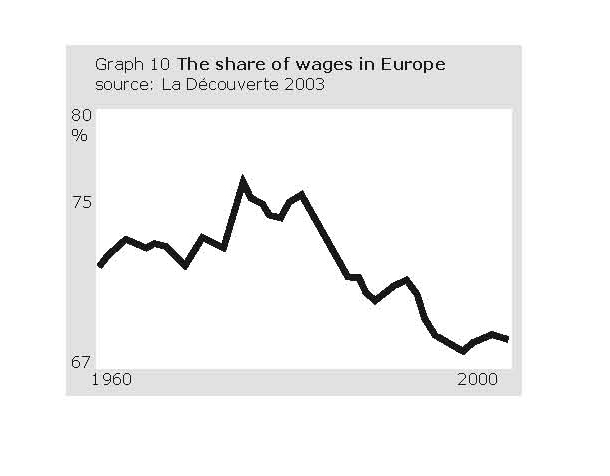

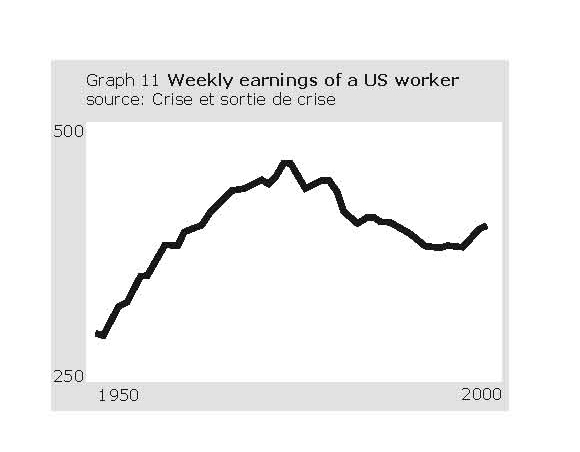

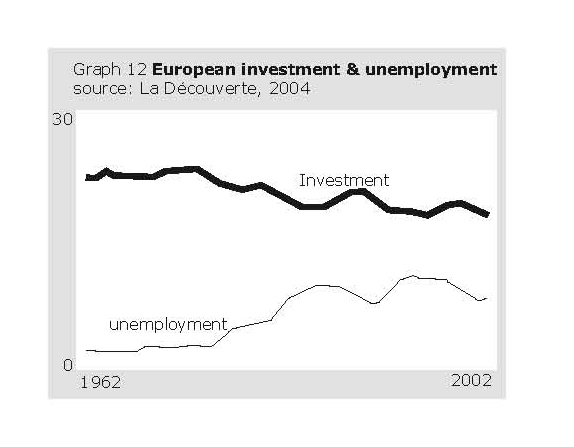

Whereas at its IVth Congress, in the 'Theses on the Trade Unions Today and Communist Action',[19] [19] Battaglia was still capable of referring to the following passage from its trade union conference of 1947: “In the current phase of the decadence of capitalist society the trade union is destined to serve as an essential instrument of the policy of conservation and thus to assume the precise functions of a state organism”, we are now told that today the trade union is still able to defend the immediate interests of the working class when the decennial curve of the rate of profit is on the rise: “Everything that union struggles won on the reformist terrain, i.e. on the terrain of union and institutional mediation, in the domain of health, insurance, schooling, in the ascendant phase of the cycle (in the 50s and partly in the 70s) ” and a counter-revolutionary role when the curve is descending: “The trade union – always an instrument of mediation between capital and labour as regards the price and conditions of the sale of labour power – has modified not the substance, but the sense of mediation: it’s no longer workers’ interests which are represented and defended against capital, but the interests of capital which are defended and masked within the working class. This is because – especially in the period of crisis in the accumulation cycle – the mere defence of the immediate interests of the workers against the attacks of capital directly puts into question the stability and survival of capitalist relations” (Prometeo n°8, ‘Draft theses…’). The unions therefore have a dual function according to whether the rate of profit is up or down. A real triumph for vulgar materialism, this one.

Even the nature of the Stalinist and social democratic parties is up for reconsideration! They are now presented as parties which did defend the immediate interests of the workers, since they had once “played the role of mediating the immediate interests of the proletariat within the western democracies, in coherence with the classic role of social democracy”, whereas after the fall of the Berlin Wall “the failure of ‘real socialism’ led them to maintain their role as national parties but also to abandon the class as the object of democratic mediation (…) the fact remains that the working class thus finds itself completely abandoned to the increasingly violent attacks of capital” (ibid). Are we dreaming? Are we really seeing Battaglia shedding tears over the fact that bourgeois institutions like the Stalinists and social democrats have supposedly lost their former ability to defend the immediate interests of the workers?

Similarly, instead of understanding the system of social security at the end of the second world war as a particularly pernicious policy of state capitalism aimed at transforming solidarity within the working class into economic dependence on the state, Battaglia sees it as working class conquest, a real social reform: “During the 1950s, the capitalist economies got back on course… This was undeniably manifested in an improvement in workers’ living conditions (social security, collective bargaining, wage increases…). These concessions were made by the bourgeoisie under pressure from the workers…” (IBRP, in Bilan et Perspectives no. 4, p 5-7). Even more serious is the fact that Battaglia even sees “collective bargaining”, the agreements which allow the unions to act as police in the factories, as an example of “social gains wrested through powerful struggles”.

We don’t have the space here to go into detail about all the political regressions that have followed Battaglia’s definitive abandonment of the framework of decadence for elaborating class positions. We will come back to these regressions in other articles. We simply want to show a few examples that will enable the reader to understand that between abandoning decadence and adopting typically leftist positions, the road is very short, terribly short! And when Battaglia spends page after page telling us that it is necessary to understand the new changes going on in the world and that we are incapable of doing this,[20] [20] it doesn’t see that by abandoning the framework of decadence, it is following the same path as the one taken by the reformists at the end of the 19th century: it was also in the name of “understanding the new realities at the end of the 19th century” that Bernstein and Co. justified their revision of marxism. By definitively abandoning the theory of decadence, Battaglia believes it has made a great step forward towards understanding “the new realities of the world”. In fact it is on the verge of returning to the 19th century. If “understanding the new realities of the world” means swapping the marxist lens of decadence theory for the lenses of leftism, then no thanks! We can see very clearly how the recurring absence of the notion of decadence from its successive platforms (with the exception of its integration into its basic positions at the time of the International Conferences of Groups of the Communist Left) is at the origin of all Battaglia’s opportunist deviations since its inception.

Conclusion

Behind its very theoretical pretensions, Battaglia’s critiques of the concept of decadence are in the end no more than a re-edition of the ones put forward by Bordiga 50 years ago. In this sense, Battaglia is going back to its original Bordigist roots. The criticism of the alleged “fatalism” of the theory of decadence was already made by Bordiga at the Rome meeting of 1951: “the current affirmation that capitalism is in its descending branch and cannot climb up again contains two errors: one fatalist, the other gradualist”. As for Battaglia’s other criticism of the theory of decadence, according to which capitalism “gains new strength through the destruction of capital and excess means of production” and that thus “the economic system reproduces itself, re-living all its contradictions at a higher level”, this was also put forward by Bordiga at the same Rome meeting: “The marxist vision can be represented by as so many ascending branches reaching their zenith…”; and in his Dialogue with the Dead: “capitalism grows without stopping and beyond all limits…” However, we have seen that this is not the vision of marxism, either of Marx: “the universality towards which it is perpetually striving finds limitations in its own nature, which at a certain stage of its development will make it appear as itself the greatest barrier to this tendency, leading thus to its own self-destruction"[21] [21] or Engels: [22] [22]

What marxism affirms is not that the communist revolution is the inevitable result of the mortal contradictions which take capitalism to the point where it renders itself impossible (Engels) and pushes towards its self-destruction (Marx), but that, if the proletariat is not able to carry out its historical mission, the future will not be that of a capitalism which “ reproduces itself, posing, once more and at a higher level, all of its contradictions” and which “grows without stopping beyond all limits” as Battaglia and Bordiga claim, but that the future of capitalism is barbarism, the real thing, the barbarism that has not ceased developing since 1914, from the butchery of Verdun to the Cambodian or Rwandan genocides by way of the Holocaust, the Gulag and Hiroshima. To understand what is meant by the alternative socialism or barbarism is to understand the decadence of capitalism.

When flattery takes the place of a political line

In the above article, as well as in the first part (International Review n°119), we examined in detail how Battaglia Comunista, under the cover of “redefining the concept” is actually abandoning the marxist notion of decadence which is at the heart of the historical materialist analysis of the various modes of production in history. We also demonstrated the typically parasitic method of the “Internal Fraction of the ICC”, which uses flattery to gain favour with the IBRP. In n°26 of its Bulletin, in an article entitled ‘Comments on an article by the IBRP, Automatic collapse or proletarian revolution’, the IFICC persists in this method. Thus Battaglia’s article is warmly saluted: “We want to salute and underline the importance of the publication of this article…” and is not seen for what it is: a grave opportunist deviation which distances itself from historical materialism in understanding the political, social and economic conditions of the succession of modes of production. The IFICC even dares to assert, with the superb dishonesty which is its hallmark, that Battaglia in its article “explicitly recognises the existence of an ascendant phase and another, decadent phase in capitalism”. For our part, we don’t take our readers for brainless imbeciles like the IFICC does. We will let them judge the validity of this affirmation by reading our two critical articles.[23] [23]

Evidently, in due deference to the parasitic method, the praise heaped on Battaglia must be accompanied by a swift kick in the direction of the ICC: we are now accused of developing “a new theory of the automatic collapse of capitalism” (Bulletin n°26), thus relaying Battaglia’s charge of fatalism against the marxist concept of decadence and, by ricochet, its rejection of the marxist concept of decomposition: “We cannot finish this rapid survey of theories of the ‘collapse’ without evoking the theory of social decomposition defended by the ICC today (…) We want to draw attention to the way this theory…has more and more become a theory whose characteristics are analogous with past theories of collapse (…) It is certain, as the IBRP points out, that both the theory of ‘collapse’ and the theory of ‘decomposition’ end up having ‘negative repercussions on the political level, generating the hypothesis that to see the death of capitalism, it’s enough to sit on the sidelines’” (ibid). And the IFICC repeats ad nauseam that the ICC “refuses to answer the fundamental question we are posing: the ‘official’ introduction by the 15th Congress of the ICC of a third way substituting for the historic alternative between war and revolution, is it or is it not a revision of marxism?” (Bulletin n°26, ‘Truth can sometimes be found in the details’). Let us make it clear that at its 15th Congress the ICC did no more than reaffirm what marxism has always defended since the Communist Manifesto, i.e. that “a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large” (Marx) is not at all inevitable since, as he said, if the classes in struggle are unable to find the strength needed to cut through the socio-economic contradictions, society will sink into a phase of “the mutual ruin of the contending classes”. Marx did not defend a phantasmagoric “third way”: he was simply consistent with historical materialism which refutes the fatalist vision according to which social contradictions will be resolved automatically by the victory of one of the two classes in struggle. According to the IFICC, we refuse to recognise that “the historic impasse can only be momentary” (Bulletin n°26, ‘Comments…’). Indeed, with Marx, we refuse to recognise a merely “momentary” historical impasse; along with him, we think that a blockage in the relations of force between the classes can indeed lead “to the mutual ruin of the contending classes”. To paraphrase the IFICC, we throw the question back at them: the IFICC’s introduction of the idea that “the historic impasse can only be momentary”, is this or is it not a revision of marxism?

In reality, in its parasitic and destructive approach to the proletarian political milieu, the IFICC is not seeking to ‘debate’ as it claims; it simply uses everything it can to add support to its delirious thesis about the ‘degeneration’ of the ICC. In doing so it reveals its ignorance of the elementary foundations of historical materialism, seeing only its own characteristics when it looks at others, in this case automatism and fatalism in the resolution of historic contradictions between the classes.

In our article in International Review n°118 we showed, with the support of numerous citations from their entire work, including the Manifesto and Capital, that the concept of the decadence of a mode of production has its real origins in Marx and Engels. In its crusade against our organisation, the IFICC doesn’t hesitate to borrow from the arguments of those academicist or parasitic groups who claim that the concept of decadence has its origins elsewhere than in the founders of marxism. Thus for the IFICC (Bulletin n°24, April 2004), the theory of decadence was born at the end of the 19th century: “We have presented the origin of the notion of decadence around the debates on imperialism and the historic alternative between war and revolution which took place at the end of the 19th century faced with the profound changes that capitalism was going through”. This lends support to a similar idea defended by Battaglia (Internationalist Communist no. 21), for whom the concept of decadence is “as universal as it is confusing… alien to the critique of political economy”, and which, in addition, “never appears in the three volumes constituting Capital”; or again that Marx only evoked the notion of decadence once in his entire work: “Marx limited himself to giving a definition of capitalism as progressive only in the historic phase in which it eliminated the economic world of feudalism, proposing itself as a powerful means of the development of the productive forces inhibited by the preceding economic form, but he never went beyond this in the definition of decadence except for the famous Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy”. Between flattery and prostitution the line is quickly crossed. The IFICC, which has the cheek to present itself as the great defender of the theory of decadence, has already crossed it.

C. Mcl

[1] [24]In particular in the following two articles: Prometeo n°8, series VI (December 2003), ‘For a definition of the concept of decadence’, written by Damen Junior (it is available in French on the IBRP website – www.ibrp.org [25] – and in English in Revolutionary Perspectives n°32, Series 3, summer 2004) and Internationalist Communist n°21 ‘Comments on the latest crisis in the ICC’, written by Stefanini Junior.

[2] [26] “Work within the workers’ economic trade union organisations, with a view to develop and strengthen them is one of the first political tasks of the Party…The Party aspires to the reconstruction of a unitary union Confederation…Communists proclaim in the most open way that the function of the union can only be completed and can only expand when it is led by the political class party of the proletariat” (Point 12 of the Political Platform of the PCInt, 1946)

[3] [27] “The Conference, after a broad discussion of the union problem, submits for general approval point 12 of the Political Platform of the Party and thus mandates the Central Committee to elaborate a trade union programme in conformity with this orientation” (proceedings of the First national Conference of the PCInt).

[4] [28] Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro: Italian trade union federation.

[5] [29] “In conclusion, if the political emigration, which took on the entire task of the Left Fraction, did not take the initiative of constituting the PCInt in 1943, this was done on the basis of the work carried out by the Fraction between 1927 and the war”(Introduction to the Political Platform of the PCInt , publication of the International Communist Left, 1946)

[6] [30] Read for example the interesting study on ‘Decadent accumulation’ in L’Internationaliste (1946), the monthly bulletin of the Belgian Fraction of the International Communist Left, or its first pamphlet entitled Entre deux mondes published in December 1946: “the battle is between two worlds: the decadent capitalist world and the rising proletarian world…Since the crisis of 1913 capitalism has entered its phase of decadence”

[7] [31] Why such political heterogeneity and cacophony? In reality, the foundation of the PCInt took place at its first conference in Turin in 1943, then at the first National Conference in 1945 with the adoption of its Political Platform. It was a mixed grouping of comrades and nuclei with diverse political horizons and positions, from the groups in northern Italy influenced by the Fraction in exile and old militants coming from the premature dissolution of the Fraction in 1945, to the groups in southern Italy around Bordiga who thought that it was still possible to redress the Communist Parties and who remained confused about the nature of the USSR, to elements of the minority excluded from the Fraction in 1936 for participating in the Republican militias during the Spanish war and the Vercesi tendency which had participated in the Anti-Fascist Committee of Brussels. On such a heterogeneous organisational and political basis, the lowest common denominator was chosen. You could not expect much clarity to come out of all this, especially on the question of decadence.

[8] [32] Available in French on Battaglia’s website: ‘Theses on the Trade Union Today and Communist Action’. Such contradictions with point 12 of its 1945 platform on the union question can also be found in the report presented by the Executive Commission of the Party on ‘The Evolution of the Trade Unions and the Task of the Internationalist Communist Union Fraction’, published in Battaglia Comunista n°6, 1948, and available in French in Bilan et Perspectives n°5, November 2003).

[9] [33] For more details on the history of the foundation of the PCInt and of the 1952 split, read our book The Italian Communist Left as well as a number of articles in our International Review: no.8, ‘The ambiguities of the PCInt on the ‘Partisans’; n°14 ‘A caricature of the party: the Bordigist party’; n°32 ‘Current problems of the revolutionary milieu’; n°33 ‘Against the concept of the ‘brilliant leader’’; n°34 ‘Response to Battaglia’ and ‘Against the PCInt’s concept of discipline’; n°36 ‘On the 2nd Congress of the PCInt’; n°90 ‘The origins of the ICC and the IBRP’; n°91 ‘The formation of the PCInt’; n°95 ‘Among the shadows of Bordigism and its epigones’; n°103 ‘Marxist and opportunist visions of the construction of the party (I) and part II in n°105.

[10] [34] La doctrine du diable au corps, 1951, republished in Le Proletaire n°464 (the paper of the PCI in French) ; Le renversement de la praxis dans la theorie marxiste in Programme Communiste n°56 (theoretical review of the PCI in France); proceedings of the 1951 Rome meeting published in Invariance n°4

[11] [35] Three conferences were held, the first in April-May 1977, the second in November 1978 and the third in May 1980. During the course of the last one Battaglia put forward a supplementary criterion for participation, with the aim, as they said themselves, of eliminating our organisation. Only two organisations (Battaglia and the CWO) out of the five participants (BC, CWO, ICC, NCI, L’Eveil Internationaliste and the GCI as an observing group) accepted this extra criterion which was therefore not formally accepted by the conference. Apart from this formal question, this avoidance of confrontation marked the end of this cycle of clarification. The fourth conference, called only by Battaglia and the CWO, was attended only by these two groups and an organisation of Iranian Maoist students, the SUCM, which disappeared soon afterwards. The reader can refer to the proceedings of these conferences as well as our comments in International Review n°10 (first conference), 16 and 17 (second conference) 22 (third conference) and 40 and 41 (fourth conference).

[12] [36] “Now that the crisis of capitalism has reached a dimension and depth which confirms its structural character, the necessity is posed for a correct understanding of the historic phase we are living through as the decadent phase of the capitalist system…” (‘Notes on decadence, I’ in Prometeo n°1, series IV, first quarter of 1978, p1); “the affirmation of the dominance of monopoly capital marked the beginning of the decadence of bourgeois society. Capitalism, once it had reached the monopoly phase, no longer had any progressive role; this didn’t mean that there could be no further development of the productive forces but that the condition for the development of the productive forces within bourgeois relations of production was a continual degradation of the lives of the majority of humanity, heading towards barbarism” (‘Notes on decadence, II’), Prometeo n°2, series IV, March 1979, p24).

[13] [37] We quote from the texts presented by Battaglia to the first and second conference, ‘Crisis and decadence’: “When this happens, capitalism has ceased to be a progressive system – that is necessary for the development of the productive forces - and enters its decadent phase, characterised by attempts to resolve its own contradictions by creating new forms of productive organisation …the growing intervention of the state in the economy must be considered as a sign of the impossibility of resolving contradictions gathering within the present relations of production…These are the most obvious signs of the decadent phase” (first conference), ‘On the crisis and decadence’; “It is precisely in this historic phase that capitalism entered its phase of decadence…Two world wars and the present crisis are the historic proof of what t the continued existence of an economic system as decadent as capitalism means at the level of the class struggle, signifying at the level of the class struggle the permanence of a decadent economic system” (second conference).

[14] [38] “The First World War, the product of competition between the capitalist states, marked a definitive turning point in capitalism's development. It confirmed that capitalism had entered a new historical era, the era of imperialism where every state is part of a global capitalist economy and cannot escape the laws which govern that economy (…) The era of history when national liberation was progressive for the capitalist world ended with the first imperialist war in 1914….today we can see there is a marked difference between proletarian political organisations of the period before October and those in the period following it. During capitalism's rise and consolidation as the dominant mode of production bourgeois nationalist or anti-despotic movements provided the framework for the mobilisation of masses of European proletarians which in turn facilitated the formation of vast trade union and party organisations. Within these organs the working class was able to express its separate class identity by putting forward its own demands, albeit within the framework of existing bourgeois social and political relations (…) The foundation of the Third International, proclaiming the opening of the era of world proletarian revolution, signalled the victory of the original principles of Marxism. Communist activity was now aimed solely at the overthrow of the capitalist state in order to create the conditions for the construction of a new society”.

[15] [39] In ‘Response to the stupid accusations of an organisation on the road to disintegration’ available on the IBRP website

[16] [40] Available in French at the following address: https://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/3303/francia/crises_du_cci_htm [41]

[17] [42] We saw in International Review n°118 that Battaglia has not read Capital very well, since the notion of decadence appears there very clearly in several places. But perhaps this is just an attempt by Battaglia to give itself an air of authority in front of the new elements looking for class positions. In the first article in our series we used over 20 quotes from the work of Marx and Engels, from The German Ideology to Capital via the Manifesto, Anti-Dühring etc, and published long extracts from a specific study by Engels entitled ‘The decadence of feudalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie’.

[18] [43] Texts presented by Battaglia to the Second Conference of Groups of the Communist Left

[19] [44] Available in French at https://www.geocities [45] .com/CapitolHill/3303/francia/syndicat_aujourd.htm

[20] [46] “the ICC…an organisation whose methodological and political base are is situated outside historical materialism and which is powerless to explain the succession of events in the ‘external world’” (Internationalist Communist n°21)

[21] [47] Principles for a critique of political economy, better known as the Grundrisse.

[22] [48] For our part, since we have begun this series of articles in defence of historical materialism in the analysis of the evolution of modes of production, re-reading the works of Marx and Engels have helped us discover and rediscover with great pleasure many passages which fully confirm what we are putting forward. This is why we repeat our invitation to all the critics of the theory of decadence to point us towards quotations from the founding fathers which they think confirm what they are saying about historical materialism.

[23] [49] In reality the IFICC knows perfectly well that Battaglia, under the cover of redefining the notion, is about toi abandon the Marxist concept of decadence. Its support for and flattery towards the IBRP is aimed simply at obtaining political legitimacy among the groups of the communist left who don’t defend or no longer defend the theory of decadence and thus to hide their real practice as thugs, thieves and sneaks.

Deepen:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Political currents and reference:

Anarcho-syndicalism faces a change in epoch: the CGT up to 1914

- 6091 reads

"In Western Europe revolutionary syndicalism in many countries was a direct and inevitable result of opportunism, reformism, and parliamentary cretinism. In our country, too, the first steps of "Duma activity" increased opportunism to a tremendous extent and reduced the Mensheviks to servility before the Cadets (...) Syndicalism cannot help developing on Russian soil as a reaction against this shameful conduct of 'distinguished' Social-Democrats".[1] [53] These words of Lenin's, which we quoted in the previous article in this series, are wholly applicable to the situation in France at the beginning of the 20th century. For many militants, disgusted by "opportunism, reformism, and parliamentary cretinism", the French Confédération générale du Travail (General Confederation of Labour - CGT) served as a beacon for the new "self-sufficient" (to use the words of Pierre Monatte[2] [54]) and "revolutionary" syndicalism. But whereas the development of "revolutionary syndicalism" was an international phenomenon within the proletariat of the time, the specific social and political situation in France made it possible for anarchism to play a particularly important role in the development of the CGT. This conjunction between a real proletarian reaction against the opportunism of the 2nd International and the old unions on the one hand, and the influence of anarchist ideas typical of the artisan petty bourgeoisie on the other, formed the basis of what has since become known as anarcho-syndicalism.

The role played by the CGT as a concrete example of anarcho-syndicalist ideas has since been eclipsed by that played during the so-called "Spanish revolution" by the Confederación Nacional de Trabajadores (CNT), which can be considered as the veritablem prototype of an anarcho-syndicalist organisation.[3] [55] Nonetheless, the CGT, founded fifteen years before the Spanish CNT, was heavily influenced, if not dominated, by the anarcho-syndicalist current. In this sense, the experience of the struggles led by the CGT during this period, and above all of the attitude adopted by the CGT at the outbreak of the first great imperialist slaughter in 1914, thus constitutes the first great theoretical and practical test for anarcho-syndicalism.

This article (the second in the series begun in the last issue of this Review) will thus examine the period from the foundation of the CGT at the 1895 Limoges congress, up to the catastrophic betrayal of 1914 which saw the vast majority of trades unions in the belligerent countries give their unswerving support to the war effort of the bourgeois state.

What do we mean by the "anarcho-syndicalism" of the CGT? Let us recall that the previous article in this series (see International Review n°118) made several important distinctions between revolutionary syndicalism properly so called, and anarcho-syndicalism:

– On the question of internationalism: the two major organisations to be dominated by anarcho-syndicalism (the French CGT and the Spanish CNT) both sank with the defence of the "Union sacree"[4] [56] in 1914 and 1936 respectively, whereas the revolutionary syndicalists (notably the Industrial Workers of the World, violently suppressed precisely because of their internationalist opposition to the war in 1914) remained - despite their weaknesses - on a class terrain. As we shall see, the CGT's opposition to militarism and war prior to 1914 was more akin to pacifism than to proletarian internationalism for which "the workers have no country": the anarcho-syndicalists of the CGT were to "discover" in 1914 that French workers did in fact have a duty to defend the fatherland of the French revolution of 1789 against the yoke of Prussian militarism.

– On the level of political action, revolutionary syndicalism remained open to the activity of political organisations (Socialist Party of America and Socialist Labor Party in the US, the SLP and - after the war - the Communist International in Britain).

– On the level of centralisation, anarcho-syndicalism is by principle federalist: each union remains independent of the others, whereas revolutionary syndicalism favours the growing political and organisational unity of the class.

This distinction was not at all clear to the protagonists of the time: up to a point, they shared a common language and common ideas. However, the same words did not always have the same meaning, nor imply the same practice, depending on who used them. Moreover, unlike the socialist movement, there was no syndicalist international where disagreements could be confronted and clarified. To be schematic, we can say that revolutionary syndicalism represented a real effort within the proletariat to find an answer to the opportunism of the socialist parties and unions, while anarcho-syndicalism represented the influence of anarchism within this movement. It is no accident that anarcho-syndicalism developed in two countries relatively less developed industrially, and more deeply marked by the weight of the small artisans and peasantry: France and Spain. It is obviously impossible, in the space of one article, to give a detailed account of such a complex and turbulent moment in history, and one should always beware of the danger of schematism. That said, the distinction remains valid in its main outline, and our intention here is therefore to see whether or not the principles of anarcho-syndicalism, as they were expressed in the CGT before 1914, proved adequate in the face of events.[5] [57]

The Commune and the IWA

The workers' movement during this period was profoundly marked by an event, and a historical tradition: le Paris Commune, and the International Workingmen's Association (IWA, also known as the First International). The experience of the Commune, the first attempt by the working class to seize power, drowned in blood by the Versailles government in 1871, left French workers with a deep distrust of the bourgeois state. As for IWA, the CGT explicitly claimed a direct descent from the International, as for example in this text by Emile Pouget:[6] [58] "The Party of Labour finds its organic expression in the CGT (...) the Party of Labour descends in direct line from the International Workingmen's Association, of which it is the historical prolongation".[7] [59] More specifically, for Pouget, one of the CGT's main propagandists, the Confederation found its inspiration in the federalist wing of the IWA (ie, the supporters of Bakunin), and in the slogan "the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves", against the "authoritarian" supporters of Marx. The irony inherent in this affiliation completely escaped Pouget, as indeed it has escaped the anarchists ever since. The famous expression that we have just cited comes, not from the anarchist Bakunin, but from the opening paragraph of the IWA's statutes, drawn up by none other than that dreadful authoritarian Karl Marx, several years before Bakunin joined the International. Bakunin, by contrast, whom the anarchists of the CGT took as their reference, preferred the secret dictatorship of the revolutionary organisation, supposed to be the "revolutionary general staff":[8] [60] "Rejecting any power, by what power or rather by what force shall we direct the people's revolution? An invisible force--recognised by no one, imposed by no one--through which the collective dictatorship of our organization will be all the mightier, the more it remains invisible and unacknowledged?".[9] [61] We should insist here on the difference between the marxist view of class organisation, and that of the anarchist Bakunin: it is the difference between the open organisation of proletarian power by the mass of workers themselves, and the vision the "people" as an amorphous mass, which needs the guidance of the invisible hand of the "secret dictatorship" of revolutionaries.

The historical context

Anarcho-syndicalism developed in France against a very specific historical background. The 20th century before 1914 is a watershed, where capitalism reached its apogee, only to plunge into the appalling massacre of the First World War which marked capitalism's definitive decadence as a social system. From the Fashoda incident of 1898 (where British and French troops faced off in the Sudan, in a competition for the domination of Africa), to the Agadir incident 1911 (when Germany sent the gunboat Panther to Agadir in an attempt to profit from France's difficulties in Morocco), and to the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, generalised European war became an ever more present and more alarming danger. When war finally broke out in 1914, it came as a surprise to nobody: neither for the ruling class, which had for years been engaged in a frantic arms race, nor for the workers' movement (resolutions against the danger of war had been voted by the Second International's congresses of Basel and Stuttgart, as well as by the congresses of the CGT).

Generalised imperialist war raises capitalist competition to a higher level, and it demands nothing less than the organisation of the entire strength of the nation for victory. The bourgeoisie was obliged to undertake a fundamental modification of its social organisation: state capitalism, where the state directs all the nation's economic and social resources in a fight to the death against the opposing imperialism (nationalisation of key industries, industrial regulation, militarisation of labour, etc.). Labour power must be organised to run war industries, and the workers must be ready to accept the resulting sacrifices. Above all, it is necessary to attach the working class to the defence of the nation and to national unity.[10] [62] The result is an enormous swelling in the apparatus of social control, and the integration of the trades unions into this apparatus. This development of state capitalism represents a qualitative mutation of capitalist society which is one of the fundamental characteristics of its decadence. Needless to say, the bourgeoisie did not understand that the change in epoch that appeared in broad daylight in 1914 represented a critical moment for its social system. However, it understood very well - especially the French bourgeoisie with the experience of the Paris Commune behind it - that before it could launch a military adventure, it was necessary first to tame the workers' organisations. The years preceding 1914 thus saw the preparation for the integration of the unions into the state.

The period before the war was thus an ambiguous one: on the one hand, an apparent increase in the power and the success of the proletarian movement, crowned by reforms voted in parliament supposedly to improve the workers' condition; on the other, these reforms had the aim of attaching the working class to the state, in particular by incorporating the trades unions into the management of these reforms.

For their part, the defeat of the Commune left the workers with a deep distrust towards any attempt by the state to involve itself in their affairs. The first union congress held after 1871 (the Paris congress of 1876) refused to accept the offer of a 100,000 franc government subsidy; the delegate Calvinhac declared: "Oh! Let us learn to do without this support, typical of the bourgeoisie for whom governmentalism is an ideal. It is our enemy. Its purpose in our affairs can only be to regulate; and you can be sure that the regulation will always be to the benefit of the rulers. Let us demand only complete freedom, and our dreams will be realised when we decide to look after our affairs ourselves" (quoted in Pelloutier's L'histoire des Bourses..., p86).

In principle, this position should have met with the steadfast support of the anarcho-syndicalists, violently opposed as they were to anything resembling "political" (ie., in their view, parliamentary or municipal) action. Reality, however, was more nuanced. The first of the Labour Exchanges,[11] [63] in whose development Fernand Pelloutier[12] [64] and the anarcho-syndicalists were to play such an important part, and whose Federation was to become a component of the CGT, was founded in Paris in 1886 following a report, not by the workers' organisations but by the city council (Mesureur report of 5th November 1886). Throughout their existence, until they merged completely with the CGT, the Exchanges maintained a turbulent relationship with local municipal councils: they might be supported, even financed, by the state at one moment, only to be suppressed at another (the Paris Labour Exchange was closed by the army in 1893, for example). Georges Yvetot[13] [65] (who succeeded Pelloutier after the latter's death) even admitted that part of his salary as secretary of the Fédération nationale des Bourses was partly subsidised by the state.

This ambiguity in the anarcho-syndicalists' attitude towards the state appeared even more sharply during the debate within the CGT on the attitude to adopt towards the new law, voted by Parliament in 1910, on workers' and peasants' pensions (the law on the "Retraite ouvrière et paysanne", known as the ROP). Two tendencies appeared: one rejected the ROP because it objected in principle to any state interference in the affairs of the working class, including retirement and pensions, while the other was in favour of winning an immediate reform by making a compromise with the state. The CGT's difficulties in taking position on this law prefigured the rout of 1914. For many militants of the CGT, the real symbol of betrayal was not so much the call to defend France and its revolutionary tradition, but the participation of the "revolutionary" Jouhaux,[14] [66] and even, despite his doubts, of the internationalist Merrheim,[15] [67] in the "Standing committee for the study and prevention of unemployment" set up by the government to deal with the economic disorganisation caused by the mobilisation of French industry for war production.

Given that anarcho-syndicalist principles were so strong within it, how did the CGT switch from its fierce defence of its own independence from the bourgeois state, to participation in the same bourgeois state in order to drag the workers into the imperialist war?

The role of the anarchists in the CGT

Although the CGT was considered a "beacon" by other revolutionary syndicalists, it should be said that the organisation was not "anarcho-syndicalist" as such. Whereas in Spain, the CNT was closely linked to the FAI (Federación Anarquista Ibérica), and competed with the Socialist Party and its union the UGT (Unión General de Trabajadores), in France the CGT was the only national organisation to bring together several hundred union federations. Amongst the latter, some were frankly reformist (in particular the book-workers' union led by Auguste Keufer, who was to be the CGT's first treasurer), or strongly influenced by the Guesdist[16] [68] revolutionary militants of the POF (or of the SFIO[17] [69] after the unification of French socialist parties in 1905). There were also some major unions (such as the reformist "old miners' union" led by Emile Basly) which remained outside the Confederation.

One can even say that the anarchists played only a minor role in the reawakening of the workers' movement in France after the defeat of the Commune. To begin with, the working class was suspicious of anything resembling a supposedly "utopian" vision, as we can see in these words of the founding committee of the 1876 workers' congress: "We wanted the congress to be exclusively working class (...) We should not forget that all the systems, all the utopias, that workers have ever been accused of never came from them; they all came from doubtless well-intentioned bourgeois, who sought remedies for our misfortunes in ideas and fine phrases, rather than seeking advice from our needs and from reality" (quoted in Pelloutier, op.cit., p77). It was doubtless this lack of radicalism in the working class which pushed the anarchists (with some exceptions such as Pelloutier himself) to abandon the workers' organisations in favour of the propaganda of the "exemplary act": bombings, bank raids, and assassinations (the anarchist Ravachol[18] [70] is a classic example).

During the twenty years that followed the 1876 congress, it was not the anarchists but the socialists, in particular the militants of Jules Guesde's POF, who played the most important political role within the French workers movement. The workers' congresses of Marseilles and Lyon saw the victory of the POF's revolutionary theses against the "pro-government" tendency of Barberet, and in 1886 it was again the POF which proposed the creation of the Fédération nationale des Syndicats (FNS). Our intention here is certainly not to sing the praises of Guesde and the POF. Guesde's rigidity - allied to a poor understanding of what the workers' movement really is, and a strong dose of opportunism - meant that the POF tried to limit the role of the FNS to support for the Party's parliamentary campaigns. Moreover, it was against the will of the party leaders that its militants supported - despite their reservations as to the class' level of organisation and so ability to carry it out - the resolutions, at the congresses of Bouscat, Calais, and Marseilles (1888/89/90), declaring that "the general strike, in other words the complete cessation of all work, can lead the workers towards their emancipation". It is thus clear that the resurgence of the workers' movement after the Commune owes a good deal more to the marxists, with all their faults, than to the anarchists. Another example in the same vein (though without in the least belittling Pelloutier's tremendous efforts) is the creation of the FNB, which also owed much to the socialists: the first two secretaries of the FNB were members of Edouard Vaillant's[19] [71] Central Revolutionary Committee.

Until 1894, and the assassination of the French president Sadi-Carnot by the anarchist Caserio, most anarchist militants paid little attention to the trades unions, being much more preoccupied with their "propaganda by the deed" approved by the 1881 international anarchist congress in London. Pelloutier himself recognised this in his famous "letter to the anarchists"[20] [72] of 1899: "Up to now, we anarchists have carried out what I would call our practical propaganda (...) without the slightest unity of viewpoint. Most of us have fluttered from one method to another, without much forethought and without following anything up, at the whim of circumstances. Someone who talked about art yesterday, will be giving a conference on economic action today and thinking about an anti-militarist campaign for tomorrow. Very few have been able to determine a systematic line of action and to hold to it, to obtain a maximum of clear and evident results in a given direction through a continuity of effort. Thus although our written propaganda is marvellous and has no equal in any collectivity - unless it be the Christian collectivity at the dawn of our epoch - our practical propaganda is extremely mediocre (...)