International Review no. 47 - 4th Quarter 1986

- 2513 reads

1936: the left leads the proletariat into imperialist slaughter

- 2822 reads

Fifty years ago, in the spring of 1936, a wave of spontaneous strikes exploded in France against the aggravation of exploitation provoked by the economic crisis and the development of the war economy, In July, in Spain, in response to Franco's military rebellion, the whole working class came out on strike against this attack. Trotsky believed he was seeing the beginning of a new international revolutionary wave.

However, in a few months, the political apparatus of the left of capital, by putting itself at the head of these movements, was able to sabotage them from within, to participate in their repression and shut the workers up in the false alternative between fascism and anti-fascism, thus playing the role of ideological recruiting sergeant for what would be the second worldwide inter-imperialist butchery.

On the anniversary of these events we are publishing two articles about them, because today it is indispensable:

-- to denounce the lie put about by the left of capital that during these events it embodied the interests of the working class, showing on the contrary that the left was the proletariat's executioner,

-- to recall the tragic lessons of these experiences, in particular the fatal trap of the working class abandoning the intransigent defense of its specific interests in order to submit to the requirements of one bourgeois camp against another;

-- to point out what distinguishes the 1930s - a period marked by the defeat of the 1917-23 revolutionary wave and by the triumph of the counter-revolution - from the present period in which new generations of proletarians are seeking to detach themselves from counter-revolutionary ideologies through a permanent and growing confrontation with capital and this same left; a confrontation which the proletariat won't be able to take to its conclusion - the communist revolution - unless it reappropriates the lessons of its past experience, which it has paid for so dearly.

The Spanish Civil War,

a rehearsal for the 2nd World War

1986 marks the 50th anniversary of the events in Spain 1936. The bourgeoisie has been commemorating this date with campaigns of falsification, launching the pernicious message that while the events of 1936 were a ‘proletarian revolution', today, by contrast, we're in a situation of ‘retreats and defeats', of a ‘crisis of the working class', of an ever-increasing submission to the laws of capital.

It's obvious that the lessons the bourgeoisie wants us to draw from past events are part of its whole tactic against workers' struggles, aimed at keeping them dispersed, isolated and divided. The object is to prevent them from extending and unifying by drowning them in a climate of so-called apathy and demobilization.

Against these maneuvers, our militant position is to defend the immense potentiality of the present struggles of the proletariat with the same force as we reject the lie of a ‘social revolution' in 1936. We link ourselves to the courage and lucidity of Bilan , who, against the stream, denounced the imperialist massacre in Spain, and provided us with the method which enables us to affirm the potentialities of the class struggle in the ‘80s and carry out a determined intervention within it.

Imperialist war or proletarian revolution?

How can we characterize the events which took the place in Spain after 1931 and which accelerated from 1936 on?

Our method isn't just based on the violent and radical nature of the class battles which shook Spain in this period, but on an analysis of the balance of forces between the classes on an international scale and over a whole historical period.

This analysis of the historic course allows us to determine whether the various conflict and situations were part of a process of defeat for the proletariat, were contained in a perspective of generalized imperialist war, or, by contrast, part of a process of rising class struggle, opening the way to revolutionary class confrontations.

In order to see what course the 1936 events were part of, we have to answer a series of questions:

-- what was the world-wide balance of forces between the classes? Was it evolving in favor of the bourgeoisie or the proletariat?

-- what was the orientation of the political organizations of the proletariat? Towards opportunist degeneration, disintegration or integration into the capitalist camp, or, on the other hand, towards clarity and the development of their influence? More concretely: did the proletariat have at its disposal a party capable of orienting its struggles towards the seizure of power?

-- did workers' councils develop and affirm themselves as an alternative power?

-- did the proletariat's struggles attack all the forms and institutions of the capitalist state?

Faced with these questions our method is that of Bilan and other left communists (for example the minority of the International Communist League of Belgium, headed by Mitchell); they began from a world-historic analysis of the balance of forces within which the events in Spain were taking place; they registered not only the non-existence of a class party, but the disarray and passage into bourgeois camp of the great majority of workers' organizations; they denounced the rapid recuperation by the capitalist state of the embryonic workers' organs of July 19, and, above all, they raised their voices against the criminal trap of a so-called, ‘destruction' of the Republican capitalist state which ‘disappeared' behind the mask of a ‘workers' government' whose function was to destroy the workers' class terrain and lead them into the imperialist butchery of the war against Franco.

What was the balance of forces after the terrible defeat of the 1920s? In what way did the death of the Communist International and the accelerated degeneration of the Communist Parties condition the situation of the Spanish workers? What was the definitive result of all this in the 1930s? A course towards confrontations between imperialist bandits or a course towards confrontations between the classes?

The reply to these questions was vital for determining whether or not there was a revolution in Spain and, above all, for pronouncing on the nature of the violent military conflict between the Francoist and Republican forces, for seeing how they fitted in with the aggravation of imperialist conflicts on a world level.

Abandoning the class terrain

On 19 July 1936, the workers came out on strike against Franco's uprising and went en masse to the barracks to disarm this attempt, without asking permission from the Popular Front or the Republican government who put as many stumbling blocks in their way as possible. By uniting the struggle for demands with the political struggle, the workers thus held back Franco's murderous hands. But other murderous hands paralyzed them by appearing to offer a hand of friendship: the Popular Front, the Republican government of Companys who, with the aid of the CNT and the POUM, managed to get the workers to abandon the class terrain of a social, economic, and political battle against Franco and the Republic, diverting them onto the capitalist terrain of an exclusively military battle in the trenches, a war of positions exclusively against Franco. Faced with the workers' response of July 19, the Republican state ‘disappeared', the bourgeoisie ‘ceased to exist', hiding itself behind the Popular Front and the more ‘left wing' organs like the Central Committee of Anti-Fascist Militias or the Central Council of the Economy. In the name of this easily-conquered ‘revolutionary change', the bourgeoisie demanded, and obtained from the workers a Sacred Union devoted to the single objective of beating Franco. The bloody massacres which then followed in Aragon, Oviedo, Madrid, were the criminal result of the ideological maneuver of the Republican bourgeoisie who had aborted the class embryo of 19 July1936.

Having left its class terrain, the proletariat was not only plunged into the war but, as a consequence, more and more sacrifices were imposed on it in the name of the ‘war of liberation'; wage cuts, inflation, rationing, exhausting working days ... Disarmed politically and physically, the proletariat of Barcelona launched a despairing uprising in May 1937 and was vilely massacred by those who had so basely deceived it:

"July 19th 1936 - the workers of Barcelona, barehanded, crushed the attack of Franco's battalions which were armed to the teeth. May 4th 1937 - the same workers, now equipped with arms, left many more dead on the streets than in July when they had to fight back against Franco. This time it is the anti-fascist government - including the anarchists and receiving the indirect solidarity of the POUM - which unleashes the scum of the forces of repression against the workers....Are the military fronts a necessity imposed by the current situation? No! They are a necessity for capitalism if it is to contain and crush the workers: May 4 1937 is stark proof of the fact that after July 19 1936, the proletariat had to fight Companys and Giral just as much as Franco. The military fronts can only dig a grave for the workers because they represent the fronts of capitalism's war against the proletariat. The only answer the Spanish workers can give to this war is the one given by their Russian brothers in 1917: revolutionary defeatism in both camps of the bourgeoisie, the Republican as well as the ‘fascist'; the transformation of the capitalist war into a civil war for the total destruction of the bourgeois state." (Bilan, ‘Bullets, Machine Guns, Prisons: this is the reply of the Popular Front to the workers of Barcelona who dared to resist the capitalist offensive').

The ‘argument' that Spain 1936 was a ‘revolution' has no foundation and implies a total ignorance of the conditions for a real proletarian revolution.

The international context was one of defeat and disarray for the working class:

"If the internationalist criterion means anything, it must affirm that under the sign of a growing counter-revolution on a world scale, the political orientation of Spain-between 1931 and 1936 could only go in a parallel direction and not in the opposite direction, towards a revolutionary development. The revolution can only reach its full development as the product of a revolutionary situation on an international scale. It's only on this basis that we can explain the defeats of the Paris Commune and the Russian Commune of 1905, as well as the victory of the Russian proletariat in October 1917." (Mitchell, ‘The War in Spain', Jan ‘37).

The immense majority of proletarian political organizations were going through a terrible rout: the Communist Parties were being definitively integrated into their respective national capitals; Trotskyism was dramatically losing itself in opportunism; the rare organizations who remained loyal to the proletariat (Bilan, etc) were suffering a dreadful isolation:

"Our isolation is not fortuitous: it is the result of a profound victory by world capitalism, which has succeeded in contaminating with its gangrene even the groups of the communist left, of whom up to now the Trotskyists have been the main spokesmen." (Bilan, ‘The Isolation of Our Fraction in Front of the Events in Spain').

"If there was any doubt about the fundamental role of the party in the revolution, the Spanish experience since July 1936 is enough to eliminate it definitively. Even if you assimilate Franco's attack to that of Kornilov in August 1917 (which is false historically and politically), the contrast between how the two situations evolved is striking. The one in Spain led to a growing class collaboration culminating in the Sacred Union of all political forces; the other, in Russia, led to the heightening of the class struggle culminating in a victorious insurrection, under the vigilant control of the Bolshevik party which had been tempered by fifteen years of criticism and of armed struggle." (Mitchell, ‘The War In Spain').

There can't be an opportunist rout of all the revolutionary forces towards the bourgeois camp at the same time as the working masses are going from victory to victory. It's quite the opposite: the rising class struggle is both the result of, and the impulse behind, a movement towards clarification and regroupment among revolutionaries; but when the revolutionary forces are reduced to their lowest ebb, this expresses and reinforces a course of defeat for the working class.

Submission to the bourgeois state

Despite all the propaganda about the ‘revolutionary value' of the factory committees, the collectives, etc, neither did any workers' councils exist in 1936:

"Immediately smothered, the factory committees, the committees of control in enterprises that had not been expropriated (in consideration of foreign capital or for other considerations) were transformed into organs which had to activate production and thus their class meaning was also deformed. They were no longer organs created during an insurrectional strike to overthrow the state, but organs oriented towards the organization of the war, essential to the survival and strengthening of this state" (Bilan, ‘The Lessons of the Events in Spain').

In order to dragoon the workers into the imperialist slaughter, everyone, from Companys to the POUM, from Azana to the CNT, ‘ceded power' to the workers organs:

"Confronted with class conflagration, capitalism cannot even dream of resorting to the classical methods of legality. What threatens capitalism is the independence of the proletarian struggle, since that provides the condition for the class to go on to the revolutionary stage of posing the question of destroying bourgeois power. Capitalism must therefore renew the bonds of its control over the exploited masses. These bonds, previously represented by the magistrates, the police and prisons, have in the extreme conditions which reign in Barcelona taken the form of the Committee of Militias, the socialized industries, the workers' unions managing the key sectors of the economy, the vigilante patrols, etc." (Bilan, ‘Bullets, Machine Guns, Prisons...').

In the final analysis, the worst lie of all was the criminal mirage of the so-called ‘destruction' or ‘disappearance' of the Republican state. Let's leave the marxists of Bilan and the minority of the ICL to denounce this lie:

1) "Concerning Spain, there has been much talk of a proletarian revolution on the march, of dual power, the ‘effective' power of the workers, ‘socialist' management, the ‘collectivization' of the factories and the land, but at no point has the problem of the state or of the party been posed on a marxist basis." (Mitchell, ‘The War in Spain').

2) "This fundamental problem (he refers to the question of the state) was replaced by that of destroying the ‘fascist bands' and the bourgeois state remained standing while adopting a ‘proletarian' appearance. What has been allowed to predominate is a criminal equivocation about the ‘partial' destruction `of the state, with much talk of a ‘real workers' power', and the ‘facade of power' of the bourgeoisie; this has been concretized in Catalonia in two ‘proletarian' organs: the Central Committee of Antifascist Militias and the Council of the Economy." (Mitchell, ibid).

3) "The Central Committee of the Militias was the weapon inspired by capitalism to drag the proletarians away from their towns and localities towards the territorial fronts where they were pitilessly massacred. It was the organ which re-established order in Catalonia, not with the workers, but against the workers who were dispersed to the fronts. Certainly the regular army was practically dissolved, but it was gradually reconstructed with militia columns whose general staff remained openly bourgeois - Sandino, Villalba, and their consorts. The columns were based on volunteers and could remain so until the illusion of revolution gave way to capitalist reality. Then there was a rapid march towards the official reestablishment of a regular army and towards obligatory service." (Bilan, ‘Lessons of the Events in Spain').

4) "The essential components of the bourgeois state remained intact:

-- the army took on other forms - the militias - but it retained its bourgeois content by defending the capitalist interests of the anti-fascist war;

-- the police force, formed by the assault guards and the civil guards, wasn't dissolved but hid behind the barracks for a while to return at an opportune moment;

-- the bureaucracy of the central power continued to function and extended its grip into the militias and the Council of the Economy. It wasn't at all a mere executive agent of these organs - on the contrary it inspired them with directives in accord with capitalist interests." (Mitchell, ibid).

5) "The tribunals were rapidly re-established with the aid of the old magistrates, with the added participation of the ‘antifascist' organizations. The popular tribunals of Catalonia were always based on collaboration between the professional magistrates and the representatives of all the parties ... The banks and the Bank of Spain remained intact and everywhere precautionary measures were taken to prevent them (even by force of arms) from falling into the hands of the masses." (Bilan, ibid).

From the ‘30s to the ‘80s

We've already seen that, as Marx said, bourgeois ideology turns reality on its head: it presents the 1930s as ‘revolutionary' years whereas today we are in a ‘counterrevolutionary' period.

If the bourgeoisie insists so much on this upside-down reality its precisely because of its profound fear of the potentiality of the workers' struggle today and because, at the same time, it mourns the passing of the ‘30s when it was able to enroll the proletariat into the imperialist butchery and present each of its defeats as ‘great victories'.

A that time, in 1936, the mystifications about anti-fascism, ‘defending democracy', taking sides between contending capitalist factions (fascism/anti-fascism, right/left, Franco/Republic) were increasingly polarizing the world proletariat, augmenting its demoralization and its enthusiastic adherence to the war-plans of the bourgeoisie, culminating in the terrible butchery of 1939-45.

Today, the mystifications about anti-fascism, national defense, supporting the ‘socialist fatherland' in Russia, convince less and less workers who are increasingly distrustful and hostile towards such lies. It's true that, for the moment, this hasn't been translated into a massive understanding of the necessity to put forward a revolutionary alternative to the bankruptcy of capitalism; there is still a skeptical, wait-and-see attitude prevailing. But this attitude can and must be transformed through the development of workers' struggles against the increasingly brutal and massive attacks of capital, and through the intervention of revolutionaries within these struggles.

At that time, the left governments, the Popular Fronts, had wide support amongst the working class, to the point that in many countries (France, Sweden, Spain), it was they who convinced the workers to accept every imaginable sacrifice ‘for the good of the country'.

Today, the working class is defending its class interests against all governments, whether right or left, applying in practice the watchwords that Bilan put forward without success in the ‘30s: "Not to play the game of the left when struggling against the right and not giving any benefit to the right when struggling against the left." A conclusive demonstration of this is that the ‘socialist' governments in France, Greece, Spain, Sweden, etc, have been faced by massive and determined responses by the workers, who haven't been taken in by the line that they have thereby been fighting ‘their own' government.

At the time, the proletarian parties which had been created round the time of the formation of the Third International, the Communist Parties, were reaching the end of a tragic process of opportunist degeneration and were integrating themselves into the capitalist camp, using their undeniable working class past to excuse a policy of defending the bourgeois state. As for the communist fractions which broke from them and continued the intransigent defense of class positions, they were increasingly isolated and came up against the growing incomprehension of the workers.

Today, the organizations which have remained loyal to the historic continuity of communist positions are enlarging their echo in the class; at the same time, we are seeing the emergence in a whole number of places of nuclei, groups and elements who are clearly posing the question of breaking with the left of capital and seeking a communist coherence. All this, though still at its beginnings and accompanied by all sorts of doubts, hesitations and confusions, constitutes the basis for a process of political decantation which will lead to the formation of the world communist party, the new proletarian International.

In other words, while the workers' struggles in 1936, in particular in Spain, took place within the course opened up by the defeat of the revolutionary wave of 1917-23 and the triumph of the counter-revolution in Germany, Italy, central Europe and Russia, today's workers' struggles are p art of a process of the reconstitution of the unity of the world proletariat, which is breaking out of the grip of the ideology of the ruling class and entering upon decisive battles against capital.

The maneuvers of the Left: an experience never to be forgotten

The comparison between the two periods leads us to another fundamental lesson: the continuity in the anti-working class activity of the left parties and the unions, both then and now. Their tactics aren't the same because, as we have just seen, there are obvious differences in the balance of forces between the classes and in the state of consciousness of the working class, but what hasn't changed is their anti-working class function as a fundamental bastion of the capitalist state against workers' struggles.

Despite the different historical conditions, an examination of the maneuvers of the left parties and the unions - especially the CNT - in Spain ‘36 can provide us with a perspective for fighting against their maneuvers and traps in the present struggles.

In 1931, the PSOE, which had already demonstrated its integration into Spanish capital through its open collaboration with the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (Largo Caballero was the dictator's state adviser and the UGT played the role of stool pigeon in the factories), made an alliance with the Republicans and, up until 1933, participated in the ferocious repression of the workers' and peasants' struggles, the high point of which was the cruel massacre of Casasviejas. Today the PSOE has been at the head of the government since 1982 and, as in the ‘30s, has left no doubts about its capitalist nature and its fierce hatred for the workers, assassinating a worker during the shipyard strike in Bilbao.

But, as we have indicated:

"The left doesn't accomplish this (capitalist) function only or even generally when it's in power. Most of the time it accomplishes it when it's in the opposition because it's generally easier to do it when in opposition than when in power ... In the ‘normal' situation of capitalism, their presence in government makes them more vulnerable; being in power wears out their credibility more quickly. In a situation of instability this tendency is even more accelerated. Then, their loss of credibility makes them less able to carry out their task of immobilizing the working class..." (International Review 18, ‘In Government or in Opposition, the ‘Left' Against the Working Class').

For these reasons, the PSOE, which in January 1933 had wet its hands with workers' blood at Casasviejas, left the government in March and, followed by the UGT, ‘radicalized' its language to the point where Largo Cabellero, the former state adviser to Primo de Rivera and Minister of Labor between 1931 and 1933, became the ‘Spanish Lenin'.

In opposition, the PSOE promised the workers ‘revolution' and talked about ‘huge arms depots ready for the right moment to carry out the insurrection.' With this celestial music, it opposed the workers' struggle for immediate demands, since they supposedly ‘prejudiced the plans for insurrection.' In fact, like its compatriots in Austria, it was deliberately leading the workers towards a suicidal clash with the bourgeois state.

In October 1934 the workers of the Asturias fell into this trap. Their heroic uprising in the mining areas and in the industrial belt of Oviedo and Gijon was completely isolated by the PSOE which used all the means at its disposal to prevent the workers in the rest of Spain, particularly in Madrid, from coming to the support of the movement. It played the trick of tolerating ‘peaceful' strikes which couldn't extend the front opened up by the Asturias miners.

This criminal maneuver of the PSOE and the UGT allowed the Republican government to crush the workers' revolt with the most savage repression, At the head of the troops sent to carry out the massacre was Franco, qualified by the parties of the time as a ‘professional general, loyal to the Republic'.

But the maneuver in the Asturias opened up a phase of ferocious repression throughout the country; any known working class militant was put in prison without the ‘Spanish Lenin', Largo Caballero, raising a finger.

The finger that the PSOE did raise, in accordance with a general tactic put into practice in other countries, was the famous ‘Popular Front'. This leagued together the PSOE and the UGT, the Republican parties (Azana and co.), the PCE (in this way definitively integrating itself into the capitalist state) and the CNT and the POUM, two organisms which had been working class up till then, and which supported it in a ‘critical' way.

The Popular Front openly advocated replacing the workers' struggle with the electoral farce, the struggle of the class as a class against all factions of capital, with a struggle on capital's terrain, against the bourgeoisie's ‘fascist' faction and in favor of its ‘anti‑fascist' faction. In opposition to the struggles of the workers and poor peasants for their own demands, it put forward an illusory and ridiculous ‘reform program' which would never be applied; in opposition to the only perspective possible for the proletariat (the communist revolution), it put forward the phantasmagorical specter of a ‘democratic revolution'...

This was a criminal demobilization of the workers, a way of derailing their combat onto the terrain of the bourgeoisie, of disarming them, of breaking their unity and consciousness and delivering them, bound hand and foot, to the military, who since the very day of the triumph of the Popular Front (February 1936) had been calmly preparing a bloodbath for the workers with the tacit approval of the ‘peoples' government.

When Franco finally staged his uprising on 18 July, the Popular Front, showing its true colors, not only tried to calm the workers, telling them to go home, but categorically refused to hand out arms. In a famous declaration, the Popular Front appealed for calm and coined the slogan: ‘The Government Commands, The Popular Front Obeys', which concretely meant calling on the workers to remain passive and obedient so that they could be massacred by the military.

This is what happened in Seville, where the workers followed the advice of the very ‘antifascist' PCE to remain calm and await government orders; this allowed general Queipo del Llano to take control very easily and organize a terrible bloodbath.

As we've seen, it was only the uprising of the workers of Barcelona and other industrial centers, on their own class terrain, uniting the struggle for demands with the political struggle, which paralyzed the executioner Franco.

But the forces of the left of capital, PSOE, PCE and co were able to react in time and set in motion a maneuver which proved decisive. Rapidly, within 24 hours, they put themselves at the head of the workers' uprising and succeeded in derailing it into a struggle exclusively against Franco - thus giving a free hand to the Republic and the Popular Front - and exclusively on the military terrain, outside of the social and political terrain of the working class, away from the major industrial and urban concentrations.

In 24 hours, the government of Martinez Barrio - formed to negotiate with the military rebels and jointly organize the massacre of the workers - was replaced by the Giral government, more ‘intransigent' and ‘antifascist'.

But the essential thing was to gain the unconditional support of the CNT, which regrouped the major part of the Spanish workers and which had quickly called off the strike and oriented the workers' organs created spontaneously in the factories and working class neighborhoods - the committees, militias, patrols - towards ‘antifascist' collaboration with the Republican authorities (Companys, Azana, Popular Front, etc) and towards transforming them into agencies for recruiting the workers to be butchered at the front.

With this step, the degeneration of the CNT was complete and it integrated itself definitively into the capitalist state. The presence of CNT ministers first in the Catalan government, then in the central government, presided over by the inevitable Largo Caballero, merely sealed this trajectory. All the leading organs of the CNT declared a ferocious war against the rare currents who, despite terrible confusions, struggled to defend a revolutionary position, such as for example the groups around the publication ‘The Friends of the People'. These elements found themselves being isolated, expelled, sent to the most dangerous positions at the front, denounced indirectly to the Republican police, by the whole band of Garcia Oliver, Montseny, Abad de Santillan, etc.

The Popular Front's maneuver, the ‘antifascist war', was definitive. It led the Spanish workers to a slaughter of monstrous proportions: more than a million dead. But the killing was also accompanied by incredible sufferings behind the lines, not only in the Francoist zones but the Republican ones as well. In the name of the ‘antifascist war', the few workers' gains conceded to pacify the workers' uprising of 19 July ‘36 were immediately annulled, with the CNT being the first to demand it. Starvation wages, exhausting hours of work, rationing, the militarization of labor, in short the savage and total exploitation of the workers.

The PCE was then the main party of exploitation, of sacrifice for the war, of anti-working class repression.

The slogan of the Stalinist party was ‘No To Strikes in Democratic Spain.' This was in fact more than a slogan. It was the banner under which, by means of the police, the majority of which were under its control, it aimed to put a stop to all strikes and class demands in the factories. It was the PCE's Catalonian front organization, the PSUC, which in January 1937 organized a ‘popular' demonstration against the factory committees which were too reticent about accepting the imperatives of militarization.

In Republican Spain the PCE was the party of order. This is why so many military men, agricultural and industrial property owners, police functionaries and numerous ‘senoritos' of the extreme right joined it or supported it. Through such elements it rapidly gained control of the repressive apparatus of the Republican state, emptying the prisons of fascists and bosses and filling them with militant workers.

The culminating point of these outstanding services to capitalism was the killings of May 1937. The workers of Barcelona, having had enough of suffering and exploitation, rose up against a police provocation against the telephone workers. The PCE immediately organized a ferocious repression, dispatching troops from Valencia and the Aragon front. The CNT and the POUM, appealing for ‘calm' and ‘reconciliation between brothers', etc, collaborated in all this by immobilizing the workers. Franco momentarily stopped hostilities in order to facilitate the crushing of the workers by the Stalinist executioners.

The war in Spain went on until 1939. It ended in the victory of Franco and the establishment of the political regime that we all know about.

The dreadful repression which then descended on the workers who had participated in the war on the Republican side completed the bloodletting that the bourgeoisie had imposed on one of the most combative sectors of the proletariat at that time.

The horrors of the obscurantist dictatorship to some extent effaced the memory of those of the ‘democratic dictatorship' of the Republic at the beginning of the ‘30s, and the whole work of sabotaging and repressing workers' struggles carried out by the ‘left' forces of capital (PCE, PSOE, CNT) during the civil war years.

Fifty years later, the Spanish workers are again subjected to the power and exploitation of capital in the form of bourgeois democracy. The Francoists and Republicans are reconciled behind the same police and the same army in order to preserve and manage the existing social order.

Fifty years later, when the workers are again resisting the effects of the world capitalist crisis and are constituting anew, in the four corners of the planet the world proletarian army, the warnings of Bilan in 1936, the lessons of the Spanish tragedy, must be clearly assimilated: the workers can only defend themselves by counting on their own forces, by building their own class autonomy. Any abandonment of the class terrain, of the intransigent defense of their class interests, in favor of an alliance with any faction of the ruling class, will be at the workers' expense and will end in the worst defeats.

Adalen

The "Popular Front" in France,

from sabotaging to "national unity" (extracts from Bilan)

"The Popular Front shows itself to be the real process of the dissolution of the class consciousness of the proletarians, the aim of which is to keep the workers on the terrain of the maintenance of bourgeois society in each and every aspect of their social and political life." (Bilan No 31, May-June 1936).

At the beginning of the 1930s, the anarchy of capitalist production is complete. The world crisis throws millions of proletarians onto the streets. Only the war economy - not just the massive production of armaments but also the whole infrastructure required by this production - develops strongly. Industry organizes itself around it, imposing new methods of toil of which ‘Taylorism' will be one of the finest emanations.

On the social front, despite the powerful counter-revolution ‘from within' in Russia, despite the routing of the world's most powerful proletariat, the working class in Germany, the world vacillates, still seems to hesitate at the crossroads between a new world war or a new revolutionary upsurge which alone would be able to overcome this terrible perspective and open up a new future. The defeat of the workers' movement in Italy, the popular fronts[1] in France and Spain, the ideologies of national unity, nourished by the most colossal dupery and ideological swindle of the century -"anti-fascism" - finally put an end to these last hesitations. In 1939 the world will be plunged into butchery, the darkest hour of the century. The future no longer has a future; it is entirely absorbed and destroyed in a present of hate, murder and massive destruction.

The credit for this great service rendered to capital, of having wiped out the last pockets of workers' resistance in imprisoning the proletariat in a nationalist, democratic ideology, making it abandon its terrain of struggle against the consequences of the historic crisis of capitalism, must go to those who today celebrate this sinister anniversary: the capitalist left and its union guard dogs.

To celebrate the anniversary of the Popular Front is to celebrate the anniversary of war, of the final victory over the international proletariat of nationalist ideology and of the class collaboration which three years later led the workers of all nations into the colossal fratricide of the second world-war.

************

The history of the Popular Front has been raised to the status of a myth and the truth, whether about its deeds, its real content, or above all its real consequences, is far from the picture painted by those who lay claim to this glorious past and who evoke it nostalgically today.

To reveal the truth about these dark years in which the consciousness of the working class was pierced by those who, claiming to be on its side, sunk to the lowest servitude, that of nationalism, we have chosen contemporaries of that sad epoch who avoided and opposed the large-scale and hysterical ideologies, who held high the banner of workers' emancipation and of its cornerstone, internationalism. We therefore let the review Bilan speak of the content, the unfolding and of the attitude of the official left to the workers' struggles, as well as on the ‘workers' acquisitions' of the Popular Front.

Of all the myths about the history of the Popular Front, that of the workers' acquisitions, above all of ‘paid holidays', is the most widespread.

The acquisitions of the Popular Front: one big smokescreen

The reader of the long quotations from Bilan will note, if he didn't already know it, that there was nothing idyllic about the conditions of the workers during the period of the Popular Front, as the long and hard strikes which punctuated its entire history prove best of all. As far as paid holidays are concerned, to take but one example, we should say straight away that the struggles which obtained these were always conducted spontaneously by the workers in refusing the militarization of labor:

"It's not a coincidence that these big strikes have broken out in the metal industry, beginning with the aircraft factories. These are the sectors which today are working full steam as a result of the policy of rearmament pursued in all countries. This fact, sensed by the workers, leads to them launching their movements in order to reduce the brutal rhythm of the assembly lines; for the improvement of their wages; in order to obtain a collective work contract, and for the recognition of the unions by the employers; for paid holidays, on the basis of an intensification of work in the metal sector linked to the war. It is therefore a painful paradox, for which the workers are not responsible, but which has to be put down to the forces of capital which have put the workers in this situation." (Bilan No 31, May-June 1936, p. 10-15).

In the face of the tension of the work force in the framework of the reinforcement of the war economy and of the new organization of work flowing from this, the workers took up the struggle, among others, in order to obtain an annual break. But in the hands of the unions this victory, to which they themselves have not contributed, becomes a final goal, an institution to allow for the integration of the working class into the framework of the militarization of labor.

On the eve of the Popular Front: the nationalist poison

The articles of Bilan throw a different light on the period from July 1934 to the spring of 1937 than the traditional fairy tales told by the left. On what basis was the Popular Front constituted?

"Under the star of July 14"

"Under the imposing star of mass demonstrations the French proletariat is being dissolved into the capitalist regime. Despite the thousands and thousands of workers marching in the streets of Paris, it can be said that in France just as much as in Germany, there is not a proletarian class fighting for its own historical objectives. On this subject, July 14 marks a decisive moment in the process of disintegration of the proletariat and in the reconstitution of the holy unity of the capitalist nation. It's been a true national festival, an official reconciliation of class antagonisms, of exploiters and exploited. In this complete triumph of republicanism the bourgeoisie, far from imposing limits through a heavy-handed stewardship, allowed it to unfold in all its glory. The workers thus tolerated the tricolor flag of their imperialism, sung the ‘Marseillaise' and even applauded Daladier, Cot and other capitalist ministers who, along with Blum, Cachin, solemnly swore ‘to give bread to the workers, work to youth and peace to the world' or, in other words, lead, barracks and imperialist war for everyone.

"It can't be denied that events are moving fast. Since the declaration of Stalin, the situation has rapidly been clarified. From now on the workers have a fatherland to defend, they have reconquered their place in the nation, and, from now on they admit that all the revolutionary proclamations concerning the incompatibility between the Internationale and the ‘Marseillaise', the communist revolution and the capitalist nation, are nothing but fine phrases which the October revolution launched in vain, since Stalin has shown their insufficiency ...

"July 14 is therefore the final summit of the devouring of the proletariat by the democratic republic. It's the example of militant communists and socialists which convinces the workers - quite rightly hesitating - to sing the ‘Marseillaise'. What an unforgettable spectacle, writes Populaire. What a triumph, adds L'Humanite. And both refer to the ‘typical' old worker who, "with tears in his eyes", expresses the joy of hearing the hymn of his exploiters, the hangmen of June, the murderers of the communards, the civilizers of Morocco and the war of 1914, become proletarian. Duclos, in his speech, said that in saluting the tricolor flag, the workers salute the ‘revolutionary past' of France, but that his red flag represents the future. But this past continues in the present, in other words, in the fierce exploitation of the workers, in the robber wars of capitalism massacring entire generations of proletarians, In 1848 too, the bourgeoisie tried to revive the past, the traditions of ‘93, the principles of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, in order to shroud the present class antagonisms: the killings of June were the consequence of proletarian illusions ...

"And after this imposing demonstration, the defeat of the class called upon to overthrow bourgeois society, to install a communist society, we have to ask ourselves if a fascist menace is really posed in France. Until now, it seems that the Croix de Feu has been more a means of blackmail, a scarecrow to accelerate the wearing down of the proletarian masses through the united front, than a real danger. But the raising of anti-fascism to a supreme law has justified the vilest capitulations, the lowest compromises, in order to end up diverting the workers far away from their organization of resistance towards an antifascist front including even Herriot. It's not by coincidence that the decree-laws came immediately after July 14 and that they found the proletariat clearly incapacitated, whereas thousands of workers had marched a few days beforehand shouting for ‘the workers' councils'." (Bilan, July-August 1935).

In face of the defensive struggles

The preparation of the Popular Front thus already announced its future evolution, in particular in face of the defensive struggles of the workers. How did the famous year 1936 unfold on the social front?

"The reconciliation of the French and union unity"

"A breath of fresh air has crossed France on December 6th: parliament achieved an "historic day" since Blum, Thorez, Ybarnegaray have sealed the ‘reconciliation of the French'. From now on, no more murderous struggles will stain republican and democratic France. Fascism has been vanquished. The Popular Front has saved the republican institutions. If these events hadn't drawn millions of French workers behind them, if they weren't so repugnant, one could almost laugh at all this buffoonery. Nobody is menacing the bourgeois republic and everybody is menacing it. The right accuses the left and vice versa. The Popular Front proclaims its republican civil spirit, whereupon La Roque and his Croix de Feu repeat the same litany. The formations of the Croix de Feu - certainly more powerful and infinitely better armed than the workers - no more menace the Republic than do the combat and self-defense formations of the Popular Front, since both put themselves at its service to reinforce the capitalist domination which is all the more republican the better it pays to be so ...

"From the point of view of the immediate situation, the dupes of the historic day December 6 are incontestably the workers. Already, after their resistance at Brest and Toulon, they are called ‘provocateurs' by the chained dogs of the Popular Front. After the ‘reconciliation', the proletarian who tries to violently resist capitalist violence will be beaten up, injured and delivered by the agents of the Popular Front into the hands of the police. Rosa Luxemburg said that against the Spartakists, the social patriots mobilized heaven and earth, unleashed sword and fire. Spartakus had to be massacred! In France, the Popular Front, loyal to the tradition of treason, doesn't hesitate to provoke murder against those who don't yield to the ‘disarmament of the French' and who, like at Brest and Toulon, launch defensive struggles, class battles against capitalism and beyond the pillars of influence of the Popular Front." (Bilan No 26, December-January 1936).

This attitude and this beginning to the year 1936 are but the prelude to a fantastic work of attrition by the left and the unions during the movement of the spring.

"The conditions which accompany the triumph of the Popular front are thus those leading to the annihilation of the consciousness of the working class. The triumph of the government of the Popular Front signals the disappearance of any proletarian resistance to the bourgeois regime, at least of all resistance organized by the proletariat. From the centrists[2] to the socialists, all are forced to admit that the Blum government will not be a revolutionary government, that it will not touch bourgeois property, that we shouldn't take too seriously the centrist formula: make the rich pay. The program of the Popular Front has the amnesty as its first point, and not the revolution; the cleansing of the administration, the dissolution of the Leagues, and then economic measures, public works to be carried out, like those of de Plan in Belgium, to reabsorb the unemployed. The centrists will be satisfied by the last decisions of the radical party, declaring its participation in the Blum government and demanding a united vote for its election to government. Two good decisions according to L'Humanite which is impressed enough to dectare that the Popular Front finally represents the revenge of the Communards over Versailles.

"The whole bourgeois press praises the moderation of the socialists and centrists and doesn't take too seriously the claim by the extreme right that the CP is preparing a seizure of power by the soviets in the form of its Popular Front committees. But there is one discordant note in this idyllic atmosphere: the menace of wage conflicts by proletarians fed up of promises of ‘humanization' by the decree laws. The CGT has gone to great lengths to liquidate the threat of a general strike in the mines of Pas-de-Calais, a threat which could have created dangerous ripples in the period between the two electoral rounds. After the victory of the Popular Front, strike movements developed progressively, going so far as to embrace the whole Paris region recently. A Belgian journalist remarked quite rightly that the movements in France have broken out just like the May ‘36 strikes in Belgium: outside of and against the unions, and are thus ‘wildcat' movements ...

"From May 14 on, the movement reached the Paris region. At Courbevoie, the workers went on strike in the factory and won a 0.25ff increase and a collective contract for six months. At Villacoublay, the workers obtained paid holidays, then at Issy-les-Moulineaux, Neuilly, Gennevilliers. Everywhere the movements broke out without any union prompting, spontaneously, and took on the same character: strikes inside the factory.

"On Thursday May 28, at lasts the strike at Renault where 32,000 workers moved into action. On Friday and Saturday, the metal plants of the Seine entered the movement ...

"In L'Humanite and in Populaire a particular effort is made to prove that the Popular Front isn't in these movements for nothing, and above all can affect their focus. It's necessary at all costs to reassure the bourgeoisie, which, as the article of Gallus in L'Intransigeant proves, got quite a scare. Capitalism understands perfectly well that it's not a question of a real occupation of factories, but of a workers' struggle using the inside of the factory as a field of battle, and one where the intrusion of the parties of the Popular Front, of the CGT, is less to be feared. In Belgium too the miners' strike of May 1935 took on this character and clearly expressed it in refusing to receive the official delegates of the socialist unions of the POB or the CP in the mines.

"Such movements are symptomatic and full of dangers for capitalism and its agents. The workers sense that their class organizations are dissolved in the Popular Front and that their workplace becomes their specific terrain of action where they are united by their chains of exploitation. In such circumstances, one false maneuver of capitalism can lead to clashes and shocks which could open the eyes of the workers and distance them from the Popular Front. But Sarraut once again understands the situation. He leaves things as they are. No mobile guards, no brutal expulsion of workers from the factories. Negotiate, and leave the socialists and centrists a free hand.

"May 30, Cachin tries to link these class movements in opposition to the Popular Front to the latter. He writes: "The tricolor fraternizes over the factory with the red flag. The workers are unanimous in supporting the general demands: Croix de Feu, white Russians, foreigners, socialists, communists are all fraternally united for the defense of bread and respect for the law." But Populaire of the same day isn't completely in agreement with this appreciation, since after having called the return to work at Renault a victory, it writes: "This is the end. It's victory. Only at the Seguin some fanatics - there are sincere ones among them, but also provocateurs of the Croix de Feu - seem to doubt it." It's probable that the "victory at Renault hasn't been approved by numerous workers who don't want to partake of the ‘spirit of conciliation of which Frachon speaks in L'Humanite and who very often returned to work ‘with only part of what they fought for'". These will be the ‘provocateurs', the ‘Croix de Feu'.

"These gentlemen of the Popular Front have demonstrated not only to the bourgeoisie but also to the workers themselves, that no revolutionary events are taking place. Here, ‘a revolutionary occupation', writes Populaire, ‘goes on. Everywhere: joy, order, discipline.' And they show photos of workers dancing in the factory yards; talk about pleasure parties: ‘the workers go swimming, play games, or flirt'" (Bilan No 37, May-June 1936).

From sabotage to direct pitiless repression

Thus, before and during its reign, the Popular Front never made a workers' front against capitalism, but the front of the bourgeoisie against the working class. It's as such that it signs its counter-revolutionary work with the blood of the Parisian workers. That's what the repression of spring 1937 shows us.

"The ‘free, strong and happy' France assassinates the proletarians"

"The whistle of bullets has torn the mask of the Popular Front. The workers' bodies explain the ‘pause' of the Blum government. In the streets of Clichy the program of the Popular Front has been expressed through the salvoes of the mobile guards, and nothing could have better illustrated it.

"Ah! the defenders of republican order, the hangmen of bourgeois democracy can cry in jubilation. The mutiny has been broken and the old traditional cry "order reigns in Warsaw" echoes once again with the Cossacks of Max Dormoy.

"But workers' blood hasn't stained the streets of Paris for nothing, this Paris ready to commemorate the Communards of 1871. From now on, the Union Sacree has acquired a bloody significance and the workers can draw from this tragic experience a precious class lesson. Notably that there cannot be a ‘reconciliation of the French' through the voluntary capitulation of the workers' movement. The mobile guard will beat hand to impose it with bullets. That bourgeois democracy, the ‘free, strong and happy France' and the famous slogans of the ‘Popular Front', ‘bread, peace and liberty' really signify: the jurisdiction over the workers' demands, the falsehood of national defense, and bullets of the mobile guard for proletarian demonstrations which go beyond the framework traced by the social-centrists ...

"That's what the workers have learnt with the Popular Front, and the song begins to get worn out. Why didn't Blum put a stop to this fascist danger he says is imminent? Why does he take back from the workers all they have gained with their strike movements? Why does he treat them as ‘provocateurs', going over to the attack despite arbitration? Blum makes his ‘pause' solely so the workers can be compelled to continue to make sacrifices.

"All of this has created a state of irritation among the workers which expresses itself particularly in the Paris region where the reformist-centrist top brass are cornered in the union assemblies. Already, in the face of this state of tension, it was decided to organize two demonstrations in the Paris area: one for the unemployed and the other for the workers. Finally, in the metal sector, they were confronted with workers' demands for a general strike to protest against the decisions of the deciding umpire.

"It's in this tense situation that the social-centrists gave the last touch of anti-fascism in order to keep the workers on the path of the Union Sacree, ‘voluntarily' agreed to by the workers. The counter-demonstration at Clichy was to be imposing: La Roque could be shown that ‘the French nation' lives and fights for the bourgeois democracy of which Messers Daladier-Herriot are authentic representatives. The bourgeoisie too prepared itself, since, knowing the situation among the workers, it suspected somehow that the social-centrist bosses might be swamped by their troops. The mobile guards were seriously armed, as if to go to war. Among the leaders of the repressive forces there was a conviction that Blum's ‘pause' was also the pause of the workers' movement. The directive was therefore to ferociously repress the latter and the necessary ambiance was certainly stirred up among the mobile guards. There was not and couldn't have been any contradiction between the ‘fascist' police chiefs and the Popular Front government. The latter talked of the ‘pause' in explaining this necessity to the workers, whereas the former did no more than apply it with their stupid cop mentality, brutally carrying out instructions without caring about the consequences ...

"Two forces collided at Clichy: the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. The workers concentrated in masses for anti-fascist goals discovered in their numbers the exalting force to impose their anger and express the tension implanted in their flesh as eternally duped proletarians: the bourgeoisie went over to repression where the Popular Front could no longer maintain the workers on the front of the interests of capital ...

"Nothing can change the battle of Clichy. Like nothing can change the massacres in Tunisia and those carried out in recent times in Algeria, in Indochina. It's the Popular Front, which in wanting to stay in power during the ‘pause' went over to massacre the proletarians of the metropole and the colonies, where the accumulation of set-backs imposed upon the workers by Blum pushed towards more and more violent battles. The demagogic program of the Popular Front arrived at the end of the line, and the new program passes away via the massacre of the workers. And where else would one search for ‘provocateurs' than in a situation created by workers?

"The truth comes out with a clarity above and beyond any commentary: the workers going on strike come up against the capitalist state, and with it the Popular Front which opens fire. The social-centrists, conscious of this situation (which could prompt the bourgeoisie to employ material other than Blum to maintain its domination) tried to organize a vulgar anti-fascist demonstration. That's why it was to be strictly limited time-wise (until midday); it should be noted that the point was not to take up the calls for a general strike to defend the workers' demands (communiqué of the CGT and the Parisian union syndicate).

"And finally, the point was not to fight against the Popular Front government but to consolidate it" (Bilan No 40, April-May 1937). PRENAT

Glossary

Popular Front: electoral, then governmental coalition-(1936-37) regrouping the Socialist Party (SFIO) the Radical Party (or ‘Radicals') and the French Communist Party.

Croix de Feu: war veteran organization of the extreme right. Founded in 1927, it was dissolved in 1936.

Some political figures

Duclos, Cachin: French CP leaders.

Thorez: Secretary-general of the CP.

Daladier: leader of the Radical Party.

Blum: leader of the socialist party, SFIO, heading the coalition government of the Popular Front.

Herriot: President of the chamber of deputies from 1936-1940, leader of the Radical Socialist Party.

La Roque: leader of the Croix de Feu.

Newspapers

L'Intransigeant: the standard right-wing paper.

L'HumaAite: daily organ of the CP.

Le Populaire: journal of the Popular Front.

[1] A brief glossary giving the principal parties and movements, politicians, papers, etc, is to be found at the end of this article.

[2] The communist left and Bilan considered the Stalinists and the communist parties affiliated to the International to be ‘centrist'. On ‘centrism and opportunism', see the International Review No 44.

Geographical:

- France [1]

History of the workers' movement:

- 1936 - Spain [2]

General and theoretical questions:

- Imperialism [3]

Recent and ongoing:

A short clarification concerning the ‘external fraction of the ICC’

- 2373 reads

Since its formation, this organization, made up of former members of the ICC, has engaged in a campaign of calumnies against our Current. In our International Review 45 we refuted some of these lies (to have refuted them all would have taken far too much time and would have meant filling up the entire issue to the detriment of much more important questions). Among these lies, there was one which really went beyond all limits: that the ICC excluded these comrades, when it was they who voluntarily left the organization despite our insistence on the irresponsibility of such a course. In no. 3 of Internationalist Perspective, the organ of the EFICC, there is an article which proposes to explain the reasons "why we (the comrades of the minority) had to leave the organization". Although the article is a tissue of ridiculous little lies and stupid corridor gossip, at no point does it talks about an exclusion (which would after all have been a good explanation for their departure). Furthermore, the next article, ‘Why Do We Call Ourselves a Fraction' attempts to explain with so-called ‘theoretical' and ‘historical' arguments why the minority had to leave the ICC. It would be a waste of time going once again over these calumnies and the specious arguments that accompany them.

Nevertheless, we take note of the EFICC's rectification of its previous assertions about being excluded. We encourage them to go further in this direction and in their ensuing issues withdraw all the other lies which up to now they've been circulating about the ICC.

Political currents and reference:

Head-on attacks herald the unification of the workers’ struggles

- 2493 reads

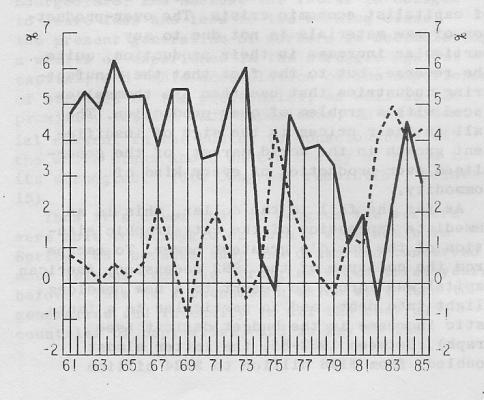

The formidable class combats that shook Belgium last April/May - the most important since Poland 1980, and since the end of the ‘60s in western Europe - have revealed the poverty of the bourgeois speeches about the "working class' realism in the face of the crisis", its "understanding of the need to make sacrifices" and other such nonsense aimed at demoralizing the workers, at preventing them from seeing the force that they represent when they struggle and unite against capitalism. These combats have highlighted the fact that the bourgeoisie's hands are not free to deal out the brutal blows against the working class that the increasing collapse of its economy demands. And this is true not only in Belgium, but throughout the countries of Western Europe, which are already, or soon will be, in the same situation. But there is more to this movement. Just as the struggles in the state sector in September 1983 - in Belgium once again - gave the signal for a powerful renewal of the workers' struggle in the major capitalist metropoles after the retreat that had followed the proletariat's defeat in Poland 1981, so the combats of spring ‘86 are the proof that the struggle of the world proletariat has entered a new phase in its development. Whereas in 1985, the bourgeoisie in the central countries succeeded .in splitting up the signs combativity, and succeeded in dispersing the workers' fight-back by keeping its attacks separate in both time and space, the workers' struggles in Belgium have highlighted the limits of this kind of policy. The imminence of a new recession, far deeper than that of 1982-83 (see the article ‘The Dead End' in this issue), is increasingly forcing the bourgeoisie to give up its dispersed attacks in favor of massive, head-on ones. As in Belgium in April/May 1986, the workers' struggles against these attacks will more and more tend to be massive and unified across branch and regional divisions.

This is the crux of the article ‘From Dispersal, Towards Unification' in the previous issue of the Review, and of the resolution adopted by our organization in June 1986, which we are publishing in this issue. Since the resolution was adopted, events have clearly confirmed its analysis. Whereas the holiday break discouraged the development of widespread movements on the part of the working class, the bourgeoisie on the contrary seized the opportunity to unleash anti-working class attacks of unprecedented brutality. As we shall see ...

Unprecedented attacks

During the summer, the most spectacular blows have been dealt in Holland - a country famed for its high living standards and social ‘protection'. A few months after its Belgian neighbor, the Dutch bourgeoisie announced attacks comparable in every way to those that, in Belgium, had provoked the massive movements in the spring. No sooner had it come into office on July 14th, than the centre-right government that emerged from the May elections announced the need to reduce drastically the budget for 1987: 12 billion florins were to be saved (the equivalent of $360 per person!). The government declared that 1987 would be "tough", but that things would improve afterwards, and that in 1990, wages would return to the level of 1986. We know what this kind of promise is worth. In the mean time, the planned measures need no comment:

-- disappearance of 40,000 out of a total of170,000 jobs in the state sector, and of more than 100,000 jobs among regional and council employees;

-- setting up a ‘self-contribution' scheme for health care (eg: payment for the first day of a stay in hospital);

-- a 5%Q increase in social security contributions which corresponds to a 2% fall in wages;

-- reduction by 25% of the sum made available for council housing (which hits above all the unemployed and the poorest workers);

-- reduction of the number of state-built houses from 41,000 to 30,000 a year (in a country which suffers from a permanent housing crisis): these last two measures will lead to the loss of 30,000 jobs in the building industry;

-- massive reduction in unemployment benefit to 60% of wages (whereas previously it stood at 85%, during the first six months, 70% for the next 18, then 60%);

-- in the private sector, limitation of wage in creases to 1.3%, with inflation at 2.3% for 1985, and rising;

-- again in the private sector, reduction of the working week to 37,5 hours, without compensation.

All in all, these measures mean a 10% fall in wages for the working class, and a 15% increase in the number of unemployed. As in Belgium, every sector of the working class (the private and state sectors, as well as the unemployed), and every element of working class income (whether it be direct or ‘social' wages) is coming under heavy attack.

Although to a less spectacular degree, the same kind of measures has hit workers in many other countries over the last few months:

-- job cuts amongst state employees in Spain and France (30,000 for 1987 in the latter country);

-- massive job cuts or redundancies in state- owned companies (50,000 in Spain's INI, 20,000 at Renault and 9,000 on the railways in France);

-- continued and intensified lay-offs and factory closures in the ‘lame duck' sectors like steel (job cuts Of 10,000 in west Germany, 5,000 in Spain, 3,000 in France, the shutdown of USX steelworks in 7 states of the US), shipbuilding (again, 10,000 job losses in Germany, 5,000 in Spain, and the closure of 3 Normed shipyards in France with 6,000 lay-offs as a result), or coal mining (example, 8,000 lay-offs in the German Ruhr.);

-- wage freezes or cuts (state employees' wages and old age pensions frozen in France, widespread wage cuts in the US, etc, );

-- rising social security contributions (0.7% tax surcharge for pension contributions, plus a 0.4% ‘exceptional' tax on all wages in France, similar measures in Spain, etc);

-- dismantling of ‘social insurance' (new reduction in the list of medicines paid for by the health service and suppression of the 100% repayment of health expenses by cooperative health schemes in France, similar but far more brutal measures in most US companies);

-- reductions in unemployment benefit (eg: elimination of special food, clothing and housing benefits in Britain).

This list could be lengthened much further without fully accounting for the terrible attack the working class is undergoing today in every country in the world. And although such attacks may make it possible for each national ruling class to escape suffocation at the hands of its competitors in the trade war that all are engaged in, in no way can they prevent the overall collapse of the world economy; they will inevitably be followed by further, still more brutal, massive and head-on attacks. The worst is yet to come.

The class struggle

Announced, for the most part, during the summer holiday period, these anti-working class measures have not yet provoked any significant response in the large industrial concentrations of Western Europe. This impression, however, is deceptive: everywhere, workers discontent is explosive, all the more so because these blows have been dealt in such an underhand way, behind the workers' backs, at a time when they could not defend themselves. The bourgeoisie moreover, is well aware of the situation: everywhere, it has entrusted its unions and left parties to prepare the ground. The same phenomenon can be seen in every country: the unions are adopting a more and more ‘radical', or even ‘extremist' language. The Swedish union L0, for example, despite being controlled by the social democratic party at present in power, has adopted an unprecedented tone of ‘combativity' and ‘intransigence'. The French CGT, controlled by the CP, has adopted a language and behavior that it would have denounced as ‘leftist' and ‘irresponsible' only a short time ago. It declares loudly that "struggle pays"; it calls for a "massive and unified counter-attack everywhere" against the government's "heavy blows"; it denounces vigorously the policies of the previous government (which it had nonetheless supported for 3 years); it is not afraid of organizing actions that are illegal (eg: blocking railway lines or motorways, or violent confrontations with the police) . If the trade unions are everywhere adopting a ‘tougher' line, it is for one very simple reason: they must keep one step ahead of the movements that are brewing, to be able to sabotage and divide them.

But whereas in Western Europe it is essentially through the maneuvers of the bourgeoisie that we can gauge the class' potential for struggle, in the US - the world's major power - the workers themselves have proven their combativity and their developing consciousness of the need for unity. In a country subjected to a deafening propaganda on the economic ‘success' of liberal ‘Reagonomics' and the ‘recovery', there have been no holidays for the class struggle:

-- in the telephone industry, 155,000 AT&T workers were out on strike for 26 days during June; 66,000 workers from other companies came out during August;

-- in the steel industry, LTV (the USA's second largest producer) was strike-bound in July; 22,000 USX workers were on strike on July 1st for the first time since 1959;

-- several other movements broke out or continued, in the airlines, the paper industry (7,500 workers), the food industry (the Hormel meat packing plant in Minnesota and the Watsonville canning factories in California); .

-- in the state sectors, 32,000 municipal workers struck in Detroit and Philadelphia (two of the biggest industrial metropoles in the East) during July/August, in particular the transport and health workers, and the dustmen.

In these last two strikes, acts of solidarity were frequent among the workers, and to some extent defused the maneuvers of division conducted together by management and unions (separate agreements being signed for each category of workers). And whereas in Philadelphia the workers' combativity and solidarity was finally defeated by lay-off threats from the law-courts after a three week strike, in Detroit they were strong enough to prevent the ruling class from resorting to such measures, and to force it to abandon one of its main objectives: making wage rises dependent on the municipality's ‘financial health' for three years to come.

In a country where the bourgeoisie has always been renowned for the cynicism and brutality of its attitude towards the working class (eg: the sacking of 12,000 air traffic controllers in August ‘81), this retreat before the Detroit strikers is a new illustration of the resolution published below:

"(The struggle) ‘pays', and ... it ‘pays' all the more when it is widespread, united, and fought with solidarity ... the stronger the working class that the bourgeoisie confronts, the more it will be obliged to dampen and put off the attacks that it intends to carry out."[1]

These workers' struggles in the US, and the extreme tension prevailing in western Europe, demonstrate that this is no time for the whining about ‘the passivity of the working class', or it being ‘under the control of the trade unions' that so many revolutionary groups still like to indulge in. In the near future, the working class is going to engage in combats of great importance, where revolutionaries will be confronted with their responsibilities: either they will take part in these combats in order to push them forward, which presupposes that they are aware of what is at stake and of the role that they must play, or else they will be mercilessly swept aside by history.

FM September 7, I986

[1] This is not contradicted by the fact that, after a brief retreat in the face of the spring strikes, the Belgian government has finally decided to apply all the proposed budget cuts. This only shows: the skill of the bourgeoisie, whose government announced the measures just before the holidays, so as to confirm them once the workers had demobilized; the continued ability of the unions to sabotage the workers' struggles, and therefore the necessity for the workers not merely to insult them as they did in Belgium, but to confront them, not to leave them the initiative, constantly pushing forward the search for unity, and in so doing to take their struggle in their own hands and to organize it themselves.

Heritage of the Communist Left:

General and theoretical questions:

- Economic crisis [9]

International Situation (resolution)

- 2372 reads

1) The resolution on the international situation from the 6th Congress of the ICC in November ‘85 was placed under the heading of the denunciation of a whole series of lies put forward by the bourgeoisie in order to mask what's really at stake in the present period:

-- "the myth of an amelioration in the situation of world capitalism, incarnated in the ‘success' of the American recovery in ‘83 and ‘84";

-- "making people believe that there is an attenuation of imperialist tensions: Reagan's speeches in ‘84 were presented as being more moderate, ‘holding out a hand' to negotiations with the USSR, and this had its equivalent in the line of diplomatic seduction being pushed by the newcomer Gorbachev";

-- campaigns to spread the idea "that the proletariat isn't struggling, that it has given up defending its class interests, that it is no longer an actor on the international political stage" (International Review 44).

If at the time these lies were based on a semblance of reality, eight months later this same reality has openly refuted all the previous campaigns, confirming once again that the ‘80s are indeed years in which the historic bankruptcy of capitalism, its barbaric and decadent nature, are being revealed in all their nakedness, and in which the real stakes of the period we're living through are being made more and more clear.

Moreover, the speeds with which events have shattered the lies of ‘85 illustrate another fundamental characteristic of these years of truth: the growing acceleration of history.

Thus the present resolution does not seek to repeat the work of the previous one in demolishing the whole inanity of what the bourgeoisie is saying. It seeks to use the November resolution as a point of support, to complement it by showing that the last 8 months have confirmed its orientations, by underlining this acceleration of history, and also to draw out the main lessons of the experience of the working class in the recent period.

The acceleration of economic collapse

2) The resolution of the 6th ICC Congress pointed to the limits of the US ‘recovery' and of America's capacity to act as a ‘locomotive' for the economies of the other countries in its bloc:

" ... it was mainly the phenomenal indebtedness of the third world in the second half of the ‘70s which allowed the industrial powers to temporarily boost their sales and relaunch production:

-- after 1982, it was the even more major debts of the USA, both external...and internal...which allowed that country to reach record growth rates in ‘84, just as it was, its enormous commercial deficits which momentarily benefitted the exports of a few other countries (such as West Germany) and thus the production levels...

In the final analysis, just as the astronomical indebtedness of the third world countries could only result In a catastrophic rebound shock, in the form of unprecedented austerity and recession, the even more considerable indebtedness of the American economy can only lead, under the threat of an explosion of its financial system....to a new recession both of this economy and the other economies whose external markets will be subject to a severe shrinkage." (ibid)

The evolution of the situation in recent months constitutes a concrete illustration of these limits:

-- the US federal budget deficit, which made it possible to create an artificial demand for US enterprises ($380 billion in ‘83 and ‘84) will simply have to be reduced (Congress has even adopted legislation in order to underline the urgency of and for this measure);

-- even more important, the 30% fall in the dollar over a few months (a fall deliberately organized by the authorities) means that the US is determined to reduce drastically its now astronomic trade deficit (which has put it at the head of the most indebted countries in the world) and thus to reconquer both its internal and external markets.

This latter fact thus signifies an intensification of the trade war against the competitors of the US (which are also its allies) - Japan and Western Europe. The latter will see their own markets collapsing, without this bringing new health to the US economy because it will mean a general restriction of the world market. Similarly, this fair in the dollar means that these countries will get their debts repaid at a rate 30% less than their initial value.

3) Similarly, the fall in the dollar in no way implies a respite for the countries of the third world. If on the one hand their 1000 billion dollar debt (most often to be paid in dollars) will be partially reduced, the revenue from their exports which is used to reimburse this debt will be amputated even more, since it's also expressed in dollars. Furthermore, their situation can only be aggravated by the often considerable fall in the price of raw materials which, under the pressure of generalized overproduction, characterizes the present period, since raw materials are generally their main if not their exclusive export. This situation is particularly spectacular and dramatic with regard to the most crucial of all raw materials, oil (the collapsing price of which shows that the price rises of ‘73 and ‘79 were based solely on speculation and not on any kind of ‘shortage'). Countries like Mexico and Venezuela, already incapable of coping with their phenomenal debts when they were selling oil at $30 a barrel, will be plunged into total bankruptcy by the $15 barrel. Thus there will be an intensification of the hellish and permanent barbarism which reigns in the third world, which the November ‘85 resolution presented as one of the most eloquent indices of the downfall of the world economy.