International Review no. 36 - 1st Quarter 1984

- 2360 reads

Address to Proletarian Political Groups: In answer to the replies

- 2836 reads

At its Fifth Congress, the ICC made an appeal to the proletarian political milieu (International Review no. 35) to face up to its responsibilities in the context of today's serious world situation. The destructive contradictions of the capitalist system, exacerbated by the world crisis, reveal all the more starkly the alternative facing the working class: war or revolution. "But instead of serving as a reference point, a beacon in the emerging social storms, the political vanguard of the proletariat frequently finds itself buffeted and shaken by events ... incapable of overcoming its dispersion and divisions which are an inheritance of the counter-revolution."

The ICC Address does not pretend to offer any miracle solutions to this problem. We essentially wanted to insist on our conviction that intervention in struggles and above all, the preparation for future decisive encounters "cannot be carried out by the mere efforts of each group taken individually. It is a question of establishing a conscious cooperation between all organizations, not in order to carry out hasty and artificial regroupments but to develop a will, an approach, which centers attention on a systematic work of fraternal debate and confrontation between proletarian political forces."

We clearly stated in the Address: "The time has not yet come for calling for new conferences of communist groups". The lessons of the breakdown of the previous cycle of International Conferences (1977-80) must first be drawn and the debate seriously taken up again on questions still left unclarified. This is particularly true of the question which provoked the dislocation of the Conferences: the role, the function, of the future party of the proletariat.

------------------------------------------------

In this article we intend to answer the different letters and proposals we received from the groups which responded to our Address. The very fact that various organizations felt the need to answer and explain their positions is, in itself, a positive sign. At least it can be said that the political organizations of the proletariat are not deaf and dumb.

But although revolutionaries are by nature optimistic, we could not help getting the distinct impression that the answers to the Address were often less the result of a profound conviction than a knee-jerk reflex: how to save face by answering while in fact washing one's hands of the real problems of the milieu by not going to the heart of the issues. Reading between the lines, one sees that groups continue to think: if other organizations are in difficulty, all the better! It gets rid of the competition! Each group builds ‘its' party and defends ‘its' territory. Is the confrontation of political positions a necessity? ‘Sure', each group writes. But in fact this answer is no more than a half-hearted ‘why not?'. The basic needs of the class are not understood and thus, this activity is not seen as a vital necessity.

The desire to think, much less act, collectively only appears when some particular event rouses the milieu from its sectarian torpor, but it is far from being a constant concern, a systematic process. ‘Intervention in the class' and ‘intervention in the political milieu of the class' are still being played off against each other. The latter is still seen as an afterthought if not an outright sterile exercise. But if political groups were really convinced:

-- that class consciousness cannot come from outside the working class itself and that it is not injected into the class as the Leninist position in What is to be Done? Claimed;

-- that the political milieu of the proletariat exists for a purpose: so that the goals and means of the class can be expressed and clarified;

all groups would understand in practice and not just in words that the debates in the milieu are the reflection of the needs of the class. They would see that discussions are not superfluous and that the themes of debate are not just fortuitous choices. They would see that the vital process of clarification within the international working class as a whole must be expressed by a movement towards clarification in its political milieu. It is futile to just keep a scorecard of groups disappearing or splitting as though the milieu were a boxing ring. Without a thorough clarification in the milieu, any errors will simply be perpetuated and this would inevitably be detrimental to the possibility of a victorious revolution.

Today, most groups recognize that a major decantation is taking place in the political milieu; they can hardly do otherwise. But they are still basically passive in this situation. There is no understanding of the urgency involved in the need for active, conscious clarification without which this dislocation will merely be a dead loss. They do not recognize that sectarianism and fear of debate doomed the International Conferences and hindered the political milieu from consciously assuming its tasks. Only a confrontation of positions can help us all to evolve towards political coherence and assure an intervention appropriate to the needs of our historical situation.

We have so far received letters from the Communist Bulletin Group (Britain), the Groupe Communiste Internationaliste (Belgium), the Communist Workers Organisation (Britain) and the ICP/Battaglia Comunista (Italy). The Fomento Obrero Revolucionario promises an answer in December 1983. Elements of the Groupe Volonte Communiste (ex-Pour Une Intervention Communiste) (France) are working on a balance sheet of their political trajectory. To begin with the basics ...

Communist Bulletin Group

How can one tell the difference between hot air and sincere conviction? By seeing whether words get translated into actions. Talk is cheap. The CBG writes:

"We want to express our solidarity with the approach and concerns expressed in the Address ... open, fraternal and continuing debate is a material necessity for the revolutionary milieu ... We have to fight for the recognition of the existence of a proletarian political milieu ..."

Fine! There is only one problem -- but a big one. The founders of this group are the same ex-members of the ICC section in Aberdeen (and ex-CWO section in Aberdeen) who covered up, participated in and justified the taking of material and money from the ICC when they played around in the troubled waters of the Chenier affair (see IR no 28). These ‘comrades' knew about Chenier's maneuvers for months beforehand and said nothing to their own comrades. They later justified stealing from us by saying this "was normal in the case of splits". Our indignation was to them the proof of our "petty bourgeois ownership attitude". The CBG as a whole still politically justifies these acts and positions. They still refuse to give back what they took. In the first issues of the Bulletin they covered all this up with baseless personal attacks against the ICC of the vilest and most stupid sort. Today, (probably because this attitude did not bring the results they counted on) they have changed their tune and hypocritically discovered "the need for healthy polemic". Whether the tone is hysterical or sickly sweet the result is the same: nowhere in the CBG press is there any disavowal of the actions or position of stealing as the origin for a group.

How can they talk about ‘solidarity' and the ‘recognition of a political milieu of the proletariat' when the very basis for this doesn't exist for them? The CBG actually put pen to paper to write: "The existence of the milieu engenders a community of obligations and responsibilities". But who is to say that these words do not actually mean: watch out the day after we disagree with you, because stealing, or whatever else comes into our head, will then automatically become ‘anti-petty bourgeois' activity. Or perhaps their view can be formulated as follows: when one splits, one can take whatever is at hand but when, at last, one is one's own master, with one's ‘own' little group, the ex-highwayman joins the circle of property owners. Or maybe because they have some new members, the old ones hope to hide behind their new name. New name, new game?

The CBG's letter cannot be taken seriously. If there are any sincere comrades in this group, the least they can do is to make an effort to understand this problem and act accordingly. It is impossible to talk about the existence of a milieu in words and do the opposite in deeds.

When El Oumami split from the ICP/Programma stealing material in France, we showed our solidarity on this elemental level. We will have the same attitude in the future: defending the proletarian political milieu against destructive attacks whatever the group concerned. At least it can be said that El Oumami's actions went along with their leftist platform. But what about the CBG?

What are its positions? The same (more or less) as the ICC! Another group whose existence is politically parasitical. What does it represent in the proletariat? A provincial version of the ICC platform minus the coherence and plus the stealing. But there is probably an evolution in the air. Most little circles which split before first clarifying their positions follow the path of least resistance at first and adopt the same platform as the group they left. But quite soon, to justify their separate existence once the drama has died down, all kinds of secondary differences are discovered and before you know it, principles are changed. This was the case for the PIC, and to a certain extent, the GCI (which both left the ICC), and the CBG is already following the same route by rejecting any coherence on the organization question.

However, this has never prevented us from polemicising with these other groups, nor from considering them as a part of the proletarian milieu in general or even inviting them to International Conferences. But this is not true for the CBG. A political group which does not respect the ‘community of obligations and responsibilities' to a point where they participate in acts aiming to injure, or destroy other organizations of the proletariat, puts itself outside the political milieu and deserves the ostracism it gets. Until the fundamental question of the defense of the political organizations of the proletariat is understood, we are obliged to consider the CBG's letter as null and void. They got the wrong Address.

Groupe Communiste Internationaliste (Belgium)

The GCI has written us:

"We agree with the principle of the need for regroupment and the world centralization of communist forces on the basis of a program. But for us this means not the primacy of consciousness over existence (discussion and exchange of ideas as a precondition) but the need for a real practical-theoretical convergence as a basis, a cement for the development of debate and polemic. That is why we are formulating real proposals for work and not the endless talk in a vacuum which characterizes, for the moment, your public meetings.

1. We think it vital that the few workers' groups that do exist develop elementary measures and practices of security and solidarity together so as to oppose a compact front against the increasingly virulent attacks of state or para-state repression. What do you think?

2. Concerning the recent important wave of struggles and the fact that unions have once again acted as strike-breakers, we feel that it is fundamental and necessary to develop a campaign of propaganda, agitation and actions centered around the question: unions equal strike-breakers; autonomous organization outside and against them; solidarity with the victims of repression, etc. We think that it is on this terrain and only on this terrain that groups can show their will to struggle." (GCI letter to ICC, 29.9.83)

We are not against joint actions if the situation requires them. We share the GCI's concern for the defense of proletarian organizations; this has always been our practice (the position taken by the ICC section in Belgium against Amada/Maoist calumnies on the GCI; the position on Chenier; against the attacks of El Oumami in France). Other occasions can arise. But for us the effectiveness of this ‘type of action' does not flow from a preparation against repression ‘in itself' (defense groups? military training?) nor from unprincipled fronts for the defense of victims in general, but from solid, principled agreement on the existence of the proletarian milieu and the need to defend it. This cannot be accomplished ‘only on the terrain of actions' but must necessarily involve what the GCI sees as ‘endless talk' -- discussions, debate, public statements at our meetings, in the press, etc. The same thing is true for the denunciation of the unions: this cannot be reduced to painting up slogans or launching ‘propaganda campaigns'. We know these kinds of campaigns only too well; the PIC was very fond of them for years. They only hide confusion and an inability to carry out real revolutionary work. The denunciation of unions is a long-term work requiring a whole framework so that intervention is not just a one-off agitation but part of a constant activity in the press, leaflets, strikes, demonstrations, etc, on an international level. Putting forward ‘projects for joint actions' as a basis is turning revolutionary activity on its head and leading it to disaster.

The GCI seems to be falling into the trap of seeing agitation as the ‘only terrain' for confrontation. This approach creates a separation between ‘theory' and ‘action' which can only make theory into sterile academicism and action into a no less sterile activism. In the end, this logic leads to depriving the class struggle of its consciousness, it's crucial element.

The GCI accuses us of idealism and Hegelianism, of giving ‘primacy to consciousness rather than existence'. In the answer to the GCI letter written by the section in Belgium (see Internationalisme, Dec. 1983), the ICC wrote:

"Just as a man breathes in order to live and not just to exercise his lungs, the ICC exists and discusses not for tea room chats but to develop a clear intervention in the class struggle. The alternative is not theory or practice; the question is what intervention, on what basis, with what positions?

It was in the name of the primacy of existence over consciousness that the Communist International imposed the policy of the united front. It was in the name of the same argument that the PCI (Programma) forbade any discussion and political intervention in the immigrants' struggle; that the GCI made a mountain out of a molehill with their phantom workers' committees (France) which evaporated as fast as they arose, and it was with the same reasoning that the GCI expelled the ICC from an unemployed committee in Brussels because according to the GCI the choice was between pasting up posters or discussing decadence.

We have seen the result of this sort of approach in the degeneration of the CI, the break-up of the PCI (Programma), the disappearance of all the GCI committees, a split in the GCI ... This logic which seeks at all costs to make agitation the only terrain of confrontation leads only to apoliticism and activism."

We do not reject joint actions; we can even add that the strike movement in Belgium in September 1983 would have required such actions. But they cannot be improvised. They call for a certain common analysis and political agreement which must be worked out through what the GCI calls ‘endless talk'!

We have gone into the implications of the GCI's approach because this kind of reasoning is not limited to them. Far from it. How many times have we heard groups say: "each group has its positions; no one is going to change -- so why bother talking". And to the extent that political groups do not try to defend their positions through rational arguments within a principled framework but try to ignore each other and avoid debate, discussion in the political milieu indeed stagnates. Some, like the GCI then conclude that rapprochement can only come from ‘one-off actions' (the GVC/ex-PIC text promised for the future will be interesting on this point) while others are glad to polemicise as long as it leads to nothing, as long as no common statement results. This was the case with the ‘dumb' International Conferences (see IR no.17). Either way the result is a dead-end.

ICP/BATTAGLIA COMUNISTA (Italy)

With its roots in the Italian Left and with its platform, this revolutionary group represents a serious current in the political milieu. It's will to polemicise, to confront political positions in the press and in public meetings is an indisputable reality. Battaglia participated in a public meeting of the ICC in Naples on the theme ‘Crisis in the Revolutionary Milieu: What is to be Done?' and later answered our address with a letter sent to all the groups which participated in the International Conferences.

Battaglia begins its response by criticizing the ICC: "We reject the ICC conception of the revolutionary camp itself. The ICC is unclear because it does not distinguish between the revolutionary camp and the camp of proletarian political forces."

If ‘revolutionary organizations' mean those groups with a coherent political platform, an organizational structure and a systematic and regular intervention in class struggle, and if ‘proletarian political camp' includes revolutionary groups but also groups without a platform or coherence or historical roots and which, on an unstable basis, claim to want to be part of the proletariat, then we can agree with this definition. Despite some occasional errors in vocabulary, we have always defended the need for this distinction. This is why in 1977 we insisted so much that Battaglia agree to define the International Conferences with clear political criteria.

Unfortunately, Battaglia uses this distinction for its own purposes:

"Who is in crisis? Certainly the ICC is. Certainly the PCI (Programma) is. Certainly not the (numerically small) forces which knew how to evaluate the situation and the problems of the Polish experience, which did not fall victim to mechanistic or idealistic positions and which benefit from solid doctrinal positions[1]. There is no crisis in the revolutionary milieu; it is a purging of the proletarian camp."

So which are the organizations of the true revolutionary camp? The CWO? If we judge from its over-estimation of the class struggle in Poland (when they called the workers to insurrection ‘now'), the CWO is not of the chosen either. But Battaglia keeps a discrete silence on this issue. The only group left is ... Battaglia! This sort of reasoning only makes us think that the sad result of Programma's megalomania has taught Battaglia nothing.

But wait. The rehabilitation of the CWO is coming. The object of the exercise is to justify the elimination of the ICC from the International Conferences. Polemics in the press are for the "vast and agitated" milieu but the Conferences are "for work towards the formation of the party". According to Battaglia and the CWO, as the three Conferences wore on they realized that the ICC did not have the same position as they did on the party. Appalled by this sudden revelation, BC "assumed the responsibility that is expected of a serious, leadership force" (BC letter) by introducing on this question an additional selective criterion unacceptable to the ICC. This is a pretty story. The ICC never ever had a Leninist position on the party, from way before the Conference in 1977. If that is what prevented the Conferences from continuing in 1980, it should have stopped them right from the beginning. So far as ‘taking up its responsibilities', we can quote an extract from our letter to BC in June 1980:

"Are we to think that your decision wasn't taken until during the conference itself? If that was the case, we can only be flabbergasted by your irresponsible underestimation of the importance of such a decision, by your improvised and precipitous behavior, which completely turned its back on the demands of the patient and systematic work which is so indispensable to revolutionaries.

But at the Conference, you said that this was in no way an improvised decision, but that you had previously talked about the necessity for a ‘selection'. Do we have to remind you, comrades, that during the meeting of the technical committee of November 1979 we clearly asked you about your intentions towards the future of the Conferences and about your apparent desire to exclude the ICC, and that you responded equally clearly that you were in favor of continuing them with their participants, including the ICC?

If, in fact, you felt that it was time to introduce a new, much more selective criterion for the calling of the future conferences, the only serious, responsible attitude, the only one compatible with the clarity and fraternal discussion that must animate revolutionary groups, would have been to have explicitly asked for this question to have been put on the agenda of the Conference and for texts to have been written on this question. But at no point in the preparation for the third Conference did you explicitly raise such a question. It was only after negotiations in the corridor with the CWO than you dropped your little bomb at the end of the Conference." (Proceedings of the Third Conference of Groups of the Communist Left)

And having rid themselves of the ICC, BC and the CWO held a fourth Conference, the culminating point in the decantation of the ‘proletarian camp' towards the ‘revolutionary camp' and the formation of the party -- with the SUCM, Supporters of the Unity of Communist Militants, a group which was just about to form ‘the Party' in Iran along with Komala, which is engaged in armed struggle for the liberation of Kurdistan in alliance with the Kurdish Democratic Party.

What is this group with whom BC "assumed its responsibilities"? According to the letters which BC sent to the SUCM in July and September 1983, the UCM "underestimates revolutionary defeatism", and its position of "defending the gains of the (Islamic) revolution does not exclude participating in the Iran/Iraq war". The UCM defends "just" wars and BC spends three pages of its letter giving lessons to its supporters on how to understand the falling rate of profit. To be sure, BC protests against the UCM's ‘social chauvinism' -- but ever so politely and it whispers to the SUCM that it really shouldn't go so far as to defend the state.

To the ICC, BC writes about our "congenital incapacity", our "theoretical inconsistency", saying that "only incompetent and incurable militants" could have our ideas. To the SUCM, it writes in the following style "allow us to say, dear comrades, that the organization of which you are the supporters can be said to have, dare we say it, a clear Stalinist leaning". What sweetness for our brothers ‘in evolution' from the third world! But for the ICC, any old insult will do. The only time BC loses its cool is when it learns that the UCM held a meeting of the ‘Internationalist Committee for Iran' to celebrate the constitution of a committee for the construction of the Communist Party of Iran, a meeting that took place in Italy with the Nuclei Leninisti Internazionalista, the Lega Leninista and others, but without BC!

In reality, the problem with BC and the CWO (which follows BC faithfully) is not that they have established a distinction between the proletarian camp and the revolutionary camp, but that they don't see the difference between the proletarian camp and the bourgeois camp. The SUCM, at least, seems more clear; it writes to BC: "either you are with the ICC, or you're with us". Now BC seems to want to distance itself somewhat from the SUCM and it has sent to different organizations the recent correspondence it's had with this group. But in the letter replying to the ICC's Address, it obstinately defends what it has done on this issue. One step forward, two steps back.

How is it that a political organization like BC, with all its experience, could have allowed itself to be drawn into a flirtation with the SUCM, a support group for bourgeois, Stalinist-type organizations?

It's true that political organizations are not infallible. But this isn't an error of enthusiasm about an unknown group. For over a year we've been warning BC and the CWO about the bourgeois content of the SUCM's political positions. Today, the fusion between the UCM and Komala, the military communiqués that we get from the SUCM on the armed struggle in Iran (how many tanks destroyed, how many people killed for the liberation of Kurdistan), as well as the Stalinist language of their documents and leaflets, can leave no doubt about what these groups are, at least for militants who aren't ‘incompetent and incurable'. The only doubt about the SUCM is knowing exactly who's behind them. BC has never posed the question about the origins of the enormous funds at the disposal of this group of Iranian dissidents, which in a year and a half has been able to cover all the main countries of Europe with its propaganda. Why does it have such an interest in penetrating the small groups of the present proletarian milieu, who can't offer anything material to the objectives of Komala? The SUCM is a very skilful group which knows how to talk the language of everyone in the milieu, which knows how to flatter the flatterers.

It's not as BC still claims, a ‘group in evolution'. How can a group coming from Stalinism, in alliance with the bourgeoisie, ‘evolve' towards the proletariat? A political organization can't cross this class frontier. If they keep slopping about in this muck, it's BC and the CWO who will evolve towards the bourgeoisie. "To know how to draw a clear line of demarcation vis-a-vis groups infested with social patriotism is the least we can demand of organizations as serious and as important as BC and the CWO." Rivoluzione Internazionale, no.33)

BC has allowed itself to be led by the nose because the SUCM, UCM and Komala talk about the party, and BC and the CWO have their vision clouded by the word ‘party'. They have turned away from the ICC under the pretext that we're ‘against the party'. It seems quite secondary whether we're talking about the bourgeois party of Kurdish nationalism.

BC has made this mistake because it has a penchant (one might say a ‘congenital' one) towards opportunist operations. According to their response to the Address, BC and the CWO are "the only ones to carry out this work towards the proletariat of the third world". If BC had really done its work towards the proletariat of the third world, it would have been quite intransigent in its denunciation of nationalism, as was the ICC in its interventions on the ‘guerilleros' in Latin America and elsewhere. This whole condescending attitude towards the militants of the third world (who are, it seems, so backward that you have to judge their positions with the indulgence of a Battaglia) is nothing less than an insult to the anti-nationalist communists of the third world, and a pure and simple alibi for Battaglia. Battaglia is no more clear on the program to be followed in Europe itself. This isn't a question of geography and it doesn't begin in 1983. In IR no.32, we published the documents of the ICP of Italy in 1945 when Battaglia and Programma were both in the ICP. Their ambiguities about the partisans, those ‘forces in evolution' during the ‘liberation' of Italy speak for themselves. Battaglia replied to us that one has to know how to get one's hands dirty. Well then, the flirtation with the SUCM is not surprising.

But the main reason behind Battaglia's wavering and contradictory policies towards the proletarian political milieu, towards the definition of this milieu and of Battaglia's own responsibility within it, is the inadequacy of their platform, full of ‘tactical' loopholes on unionism, electoralism and national liberation.

Battaglia boasts about having ‘solid doctrinal positions'. But where are they? Certainly not in the new edition of their platform. The ICC must haunt BC's dreams because they keep attributing their own weaknesses to us. According to BC, the ICC suffers from a surfeit of ‘open questions'. What exactly this refers to, we do not know. What we do know is that BC has, not ‘open questions', but gaping holes, so much so that it prevents them from seeing class lines. On all the main issues, including the question of the party, BC merely repeats the errors of the Communist International, but makes them worse with vague and contradictory formulations.

Examine the positions of the ICP/Battaglia; there is never an honest, clear rejection of the errors of the CI on the union question, electoralism or national liberation. There is not even a clear rejection of the errors of their own party, the ICP, since 1943. Just a little attenuation here and there, a fudge of formulations when the situation requires it. If Battaglia occasionally asserts the opposite of the IIIrd International's positions, it is only paying lip-service, enveloping; it in so many ‘diplomatic' and ‘tactical' ambiguities that everything is fundamentally back to square one. BC continues to twist around, equivocating; all the way.

Marx wrote that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.

At the beginning of the twenties, the centrist majority of the Communist International, led by the Bolsheviks chose to eliminate the Left to join with the Right (the Independents in Germany, etc). This was a fatal move, a tragedy for the communist movement.

In 1945, the newly created ICP of Italy, chose to eliminate the Gauche Communiste de France (see the article on the Second Congress of the ICP (1948) in this issue of the Review), in order to join with the survivors of a voluntary participation in the imperialist war in Spain in 1936, with the remnants of those who participated in the Anti-Fascist Committee of Brussels and with those who flirted with the Resistance and national liberation. This again was a tragedy for the communist milieu but it already had something of a farce played out by megalomaniacs.

In our period, the International Conferences were sabotaged to eliminate the most intransigent communist current in order to run after alliances with the UCM and other defenders of national liberation in Iran and Kurdistan. The remnants of sixty years of Stalinism were taken for ‘embryos of the future communist party' in the Third World.

This time it was a complete farce! All the more so because at least Lenin's concern was the mass unity of the proletariat, and not, as in BC's more prosaic case, the defense of a little group.

The ‘juniors' of today are no different from their ‘seniors' of 1945. The same approach, the same positions. Perhaps a bit watered down but with a good dose of hypocrisy added on. Although history repeats itself as farce, opportunism always remains the same.

Communist Workers Organization (Britain)

In its open letter of September 1983, the CWO writes:

"We agree that the working class and its minorities are in an extremely difficult and dangerous situation at the moment, though when you speak of ‘the crisis in the revolutionary milieu' it is not the one we have in mind ... More significant of the real crisis is our continued isolation as communists from the working class." (‘Reply to the "Address" of the International Communist Current')

But isolation as such isn't what provoked the crisis. For the CWO, the loss of revolutionary energies today can be put at the same level as in the past. Are we then still in the middle of the counter-revolution?

The CWO considers that the Address is "an expression of the crisis in the ICC". Does it therefore reject discussion? In the end, no: "though it is not possible to carry on relations between our tendencies at the level of the international conferences, this does not exclude debate." Thus, the CWO proposes a public meeting between the ICC and the CWO "on the topic of the present situation of the class struggle and the responsibility of revolutionaries". We have accepted this perfectly valid proposal.

But in its letter, the CWO makes a number of reproaches against the ICC and we want to deal with some of them here (to deal with all of them would be too much even for a Hercules).

* According to the CWO's letter, the ICC is not ‘serious' because "the CWO offered the ICC the opportunity to solidarise with our international intervention on the Iran/Iraq war, the ICC refused on the most ridiculous grounds." (For our response to this proposal, see World Revolution no.59.)

In the framework of the International Conferences, the CWO refused to take up a common position against imperialist war and the inter-imperialist tensions because, as it says in the same letter, these were "vague and meaningless joint positions on self-evident banalities".

But did the CWO want the ICC to rubber-stamp its dangerous ambiguities about the UCM? The CWO doesn't bring out a leaflet for every local war in the world, only for the Iran-Iraq war. And although the leaflet did take a position on those ‘self-evident banalities' it must be seen as part of the rapprochement between the UCM and the CWO.

* Also, in their response to the Address, the CWO reproaches us for not inviting them to ICC Congresses whereas they invite us to theirs.

For some years, we invited BC and the CWO to our different Congresses and they came along, together with delegations from other political groups. But after the breakdown in the International Conferences, after being pushed out by the maneuvers of BC and the CWO, we consider that it would be nonsense to invite these groups to our internal meetings. The CWO does not want the ICC to participate in conferences between groups, but it wants to come to our Congresses? It kicks us out of the conferences, but invites us to its Congresses? Is that a logical approach? Does the CWO understand the significance of its own actions?

In the article ‘On the so-called Bordigism of the CWO' (Revolutionary Perspectives, no.20, second series), the CWO doesn't want to talk about that exactly. It prefers to defend its elder brother Battaglia against a sinister plot: the ICC has called BC ‘Bordigist'. If the word bothers you, comrades, let's drop it. It does not change the basic issue. The truth is that, in this article and in the letter, the CWO is furious with the ICC because we have published documents about the ICP's opportunism towards the partisans. In fact, these articles were aimed mainly at Programma, but the hat burns on the heads of Battaglia and the CWO. And with good reason. Between 1945 and 1952, BC was at the helm of the ‘united' ICP. But what is the CWO's reply: it wails ‘mummy' and stamps its foot. ‘Lies!' it says. But it explains nothing and justifies everything.

* According to the CWO, "before 1975, the ICC never mentioned the PC Int (Battaglia)" as though we'd ‘hidden' the existence of BC from the CWO, for fear that these two titans might meet up. We did talk about Battaglia, but the CWO had its ears closed at the time. In the early seventies, the group was emerging out of the libertarian milieu and considered the Russian Revolution to be a bourgeois revolution, the Bolshevik party a bourgeois party. But when it finally recognized the October revolution and the Communist International, it was only paying lip-service. For the CWO, the counter-revolution was definitive by 1921 (it didn't say whether this was in January or December) and this fateful date was a sufficient basis to denounce the ICC as a ‘counter-revolutionary group'. At the time, we were Leninists because we talked about Bilan, but today we are called councilists because the CWO has discovered Battaglia. The CWO has gone through so many zig-zags in its life that you never know how long the latest zig will last. The CWO is reduced to polemics of the kind that appear in RP no.20 because it was born in ignorance of the history of the workers' movement, and because it has never sought for a real coherence in its attitude towards proletarian political groups.

* We can't reply to everything here, but we do want to deal with one final important point. In RP no.20 the CWO accuses us of condemning its rapprochement with BC. This is wrong. We are always for the regroupment of organizations as soon as they find themselves on the same basic political positions. We would never have condemned a BC/CWO regroupment within the International Conferences. We followed the same path ourselves with the formation of our section in Sweden in the same period. We are against the perpetuation of little sects. If groups agree, they should unite. This helps to clarify things for the proletariat.

We would go further. We have known the CWO for a long time, and comparing its present rapprochement with BC to the strange alliances its anti-ICC reactions have produced in the past (with the PIC, the Revolutionary Workers' Group of Chicago, etc) we say: much better!

The question we must ask the CWO is this: why do you maintain a separate existence? Either one thing or the other: either you agree with the platform of BC, and that means that its ambiguities on the electoral, union and national questions are shared by you; or you don't agree -- in which case, where are the discussion texts between your groups?

The CWO wants to wait and see whether the ICC is ‘really serious', whether its Address is ‘sincere'. Our Address expresses the position we have always had on the necessity for a dialogue in the political milieu of the proletariat. For more than fifteen years, we haven't shifted one iota on this point. We aren't chameleons like the CWO which changes color every two or three years. If the CWO has a short memory, we're happy to refresh it for them.

Perspectives

The groups write to us: your suggestions are vague. What do you want exactly with this Address?

We want to call for a change of heart in the political milieu of our class: the end of pretensions and of arrogance in a state of magnificent isolation; the end of evasions, of dangerous activism, of poetic licence on questions of principle.

First, to the basics. It's time to stop making the question of the party an alibi. It's time to discuss it seriously without anathemas, without going around in circles about empty formulae. It's time to respond clearly on some elementary questions before the debate can really go deeper:

-- does class consciousness come from outside the class as Lenin wrote in What is to be Done?

-- either in the past or tomorrow, is the class party the sole crucible or depository of class consciousness?

-- is it the party that takes power?

-- can the party impose itself on the class through the use of force, as in Kronstadt in 1921?

-- what criticisms, modifications, and elaborations on the question of the party can we draw from the Russian Revolution, the experience of the first revolutionary wave, and the degeneration in Russia, and in the Communist International?

These are the fundamental question which have to be answered by pushing forward the criticism of the errors and insufficiencies of the past, and by benefitting from the contribution of the entire international communist left, without any ‘Italian', ‘German' or other exclusiveness.

Even Programma, after thirty years of being closed and self-sufficient, is today being compelled by events to open a debate inside itself on the party, its function and mode of organization. But why only an internal debate? Can you catch some shameful disease by taking part in the political discussion going on in the proletarian milieu? Is the confrontation of political positions a luxury, an annexed to ‘normal' activities, something you do if there's time, or is it a necessity, the only way to verify the premises of our political contribution to the decisive struggles of our class?

It's undeniable that the absence of the International Conferences is a real problem today, that it makes it even more difficult to respond to the acceleration of history, to ensure that militant energies aren't lost in the convulsions of the political milieu, to present a principled framework for the newly-emerging elements of the class, to assist clarification in all countries, especially those which haven't had the time to develop marxist traditions. And it is also undeniable that the International Conferences were dislocated because of the sectarianism in the milieu: the PIC which rejected a ‘dialogue of the deaf'; the FOR which didn't want to discuss the economic crisis and which loudly withdrew from the Second Conference; the actions of Battaglia and the CWO which we have criticized; Programma which saw in the conferences only the ‘fuckers' and the ‘fucked'.

To create a new spirit is the only way to make it possible to hold new conferences in the future, the only way to ensure a conscious decantation in the milieu, to work towards new and absolutely necessary efforts of regroupment.

For who dares to look at the political milieu of the proletariat and say that it will never be anything else but what it is today?

JA

[1] In Battaglia, crisis is never expressed clearly and openly through opposition and confrontation of political divergences for the simple reason that there is not much of a political life of discussion within the organization. There is no real confrontation; one votes with one's feet by discretely, in silence, leaving the organization, one by one. This is not so immediately visible to the eye but just as important.

As to its ‘solid doctrinal positions', we refer the reader to the article in this IR on the Second Congress of the PCI/Italy in 1948. A reading of this report can help give the reader a more exact idea of Battaglia's ‘solid positions'.

Life of the ICC:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Debate with Battaglia Comunista on the theses of its 5th Congress

- 2474 reads

The course of history: The 80s are not the 30s

In which direction is history moving; where is our society going to? Are we heading for a new world war? Or, on the contrary, are we heading for class confrontations that will pose the question of proletarian revolution?

This is a basic, fundamental question for anyone claiming to play an active and conscious part in the class struggle.

This is why the congresses of a proletarian political organization always devote a large part of their effort to the analysis of the international situation, with the aim of grasping as firmly as possible the general dynamic of the balance of class forces.

The Partito Communista Internazionalista (Battaglia Communista) held its Fifth Congress in November 1982 and has just published the fruits of its labors in Prometeo no.7 of June 1983. The question is touched on ... even if this is partly to insist that this kind of question cannot be answered.

In a recent text (distributed at the ICC's July 1983 public forum in Naples, Italy) BC states that they consider this Congress' Theses as a contribution to the debate in the revolutionary milieu, and "is still waiting for them to be discussed in their political substance." Rather than deal superficially with all the questions touched on at BC's Congress ("crisis and imperialism", "tactics for intervention and the revolutionary party", "the transitional phase from capitalism to communism") we have limited ourselves in this article to the question of the present historic course, and what the Theses of BC's Congress have to say about it.

Is it possible to move towards world war and world revolution at the same time?

According to Battaglia, we cannot answer the question of the present perspective for class struggle more precisely than to say: it may be war, it may be revolution, it may be both. For Battaglia, there is nothing that allows us to assert that one outcome is more probable than the others. Here is an example of how this idea is formulated:

"The generalized collapse of the economy immediately gives rise to the alternative: war or revolution. But by marking a catastrophic turning point in the capitalist crisis and an abrupt upheaval in the system's superstructure, the war itself opens up the possibilities of the latter's collapse and of a revolutionary destruction, and the possibility for the communist party to assert itself . The factors determining the social break-up within which the party will find the conditions for its rapid growth and self-affirmation -- whether this be in the period preceding the conflict, during or immediately after it -- cannot be quantified. We cannot therefore determine ‘a priori' when such a break-up will take place (eg Poland)." (‘Tactics for the Intervention of the Revolutionary Party', Prometeo, June 1983)

BC starts from a basic idea which is both correct and important: there is no ‘third way out'. The alternative is war or revolution, and there is no possibility of capitalism starting on a renewed peace-time economic development. Apart from anything else, this is important in the face of the flood of ‘pacifist' illusions that the bourgeoisie is pouring over the proletariat in the industrialized countries. But it is inadequate, to say the least, in determining a perspective.

Battaglia says "the factors determining the social break-up ... cannot be quantified. We cannot therefore determine ‘a priori' when such a break-up will take place."

However, the question is not to determine the date and time of an eventual proletarian revolution but, more simply and more seriously, one of knowing whether the world bourgeoisie has the means to lead the proletariat of the industrialized countries into a third world war or whether on the contrary, pushed by the crisis and not enrolled under the capitalist banner, the proletariat is preparing for the confrontations that will pose the question of the world communist revolution.

When it says that the revolutionary situation may arise before, during or after a coming war, Battaglia admits its inability to take position on the present historical perspective.

BC justifies this inability by saying that the economic crisis can lead simultaneously to one or the other historical outcome.

There are supposedly two parallel tendencies, each with as much chance of being realized as the other.

It is true that from an objective standpoint, the economic crisis simultaneously exacerbates the antagonisms between social classes, and between rival capitalist powers. But whether one or the other of those antagonisms comes to a head depends in the last instance on one and the same factor: proletarian practice and consciousness.

It is the same, exploited, class which either affirms itself as protagonist of the revolution or serves as cannon-fodder and producer of the material means for imperialist war.

The state of mind, the consciousness of a class ready to overthrow the capitalist social order and build a new society is radically different from that of workers atomized, broken, ‘identified with' their ruling class to the point where they accept slaughtering each other on the battlefield in the name of ‘their' respective fatherlands. Marching under the red flag towards the unification of humanity is not the same thing as marching in ranks of four under the national banner to massacre the proletarians of the opposing imperialist camp. The working class cannot be in these two mutually exclusive states of mind simultaneously.

This is an obvious fact that Battaglia would accept without hesitation. However, it seems to be unaware that the processes leading to one or other of these situations are also mutually exclusive.

The process that leads to a revolutionary outcome is characterized by the proletariat's increasing disengagement from the grip of the dominant ideology and the development of its consciousness and combativity; in contrast, the process that leads towards war is expressed in the workers' growing adherence to capitalist values (and to their political and trade union representatives) and in a combativity which either tends to disappear, or appears within a political perspective totally controlled by the bourgeoisie.

These are two thoroughly different, antagonistic, mutually exclusive processes.

Anyone who analyses history in the light of the proletariat's role of central protagonist knows that the march towards war cannot be the same as the march towards revolutionary confrontations.

To affirm that these two processes can unfold simultaneously, without it being possible to determine which has the upper hand, is quite simply to reason by reducing the working class' consciousness and combativity to a mere abstraction.

How do we recognize the course towards war?

Today, Battaglia claims to be the only authentic heir to the inter-war Fraction of the Italian Left. But for this current, which remained on a class terrain throughout the dark days of triumphant counter-revolution, one of its greatest merits was its lucid recognition of the revolution's retreat after the 1920s and the opening of the course towards war in the 1930s. If it was able to recognize the Spanish Civil War and the 1936 strikes in France not as "the beginning of the revolution in Europe", as Trotsky thought, but as moments of the march towards world war that had already started, this was thanks to its ability to reason in terms of a historical course and to situate particular events within the overall dynamic of the balance of class forces on a world historical level. We only have to consider the periods leading up to the two world wars to see that they did not come as bolts from the blue, but were the result of a preparatory process during which the bourgeoisie systematically destroyed proletarian consciousness to the point where it could enlist the workers under the national banner.

In 1945, applying the method of the Italian Left, the Communist Left in France produced a remarkable summary of this process of war preparation:

"Through the intermediary of its agents within the proletariat, the bourgeoisie managed to put an end to the class struggle (or, more exactly, to destroy the proletariat's class power and its consciousness) and to derail its struggles by emptying these struggles of their revolutionary content, by setting them on the rails of reformism and nationalism -- which is the ultimate and decisive condition for the outbreak of imperialist war.

This must be understood not from the narrow and limited standpoint of one national sector taken in isolation, but internationally.

Thus, the partial resurgence of struggles and the 1913 strike wave in Russia in no way detracts from our affirmation. If we look more closely, we can see that the international proletariat's power on the eve of 1914, the electoral victories, the great social-democratic parties and the mass union organizations (the pride and glory of the Second International), were only an appearance, a facade hiding a profound ideological decay. The workers' movement, undermined and rotten with rampant opportunism, was to collapse, like a house of cards before the first blast of war.

Reality does not appear in the chronological photography of events. To understand it, we must grasp the underlying internal movement, the profound changes which have already occurred before they appear at the surface and are recorded as dates.

It would be a serious mistake to respect history's chronological order to the letter and present the 1914 war as the cause of the Second International's collapse when, in reality, the outbreak of war was conditioned by the previous opportunist degeneration of the international workers' movement. The greater the internal triumph and domination of the nationalist tendency, the louder sounded the public fanfares of the internationalist phrase. The 1914 war simply brought into the light of day the passage of the Second International's parties into the bourgeois camp, the substitution of the class enemy's ideology for their initial revolutionary program, their attachment to the interests of the national bourgeoisie.

The open completion of this internal process of destruction of class consciousness appeared in the outbreak of the 1914 war which it conditioned.

The outbreak of the Second World War was subject to the same conditions.

We can distinguish three necessary and successive stages between the two imperialist wars.

The first came to an end with the exhaustion of the great post-1917 revolutionary wave and consisted of a series of defeats for the revolution in several countries: in the defeat of the left, excluded from the Communist International by the triumph of centrism, and the beginning of Russia's evolution towards capitalism, through the theory and practice of' "socialism in one country".

The second stage is the general offensive of international capitalism, which succeeded in liquidating the social convulsions in the decisive centre where the historical alternative of capitalism or socialism was played out -- Germany -- through the physical crushing of the proletariat and the installation of the Hitler regime playing the role of Europe's policeman. This stage corresponds to the definitive death of the CI and the bankruptcy of Trotsky's left opposition which, unable to regroup revolutionary energies, engaged itself in coalitions and mergers with the opportunist currents and groups of the socialist left, and took the road of bluff and adventurism by proclaiming the Fourth International.

The third stage saw the total derailment of the workers' movement in the ‘democratic' countries. Under cover of defending workers' ‘liberties' and ‘conquests' from the threat of fascism, the bourgeoisie's real aim was to win the proletariat's adherence to the defense of democracy -- ie of national bourgeoisie and the capitalist fatherland. Anti-fascism was the platform, the modern capitalist ideology, that the proletariat's traitor parties used to wrap up the rotten produce of defense of the nation.

During this third stage occurred the definitive passage of the so-called communist parties into the service of their respective capitalisms, the destruction of class consciousness through the poisoning of the masses with anti-fascist ideology, the masses' adherence to the future imperialist war through their mobilization in the ‘Popular Fronts', the perverted and derailed strikes of 1936. The definitive victory of state capitalism in Russia was expressed, amongst other things, by the ferocious repression and physical massacre of all attempts at revolutionary reaction, by Russia's entry into the League of Nations, its integration into an imperialist bloc and the installation of the war economy with a view to the oncoming imperialist war. This period also witnessed the liquidation of many revolutionary and Left Communist groups with their origins in the crisis of the CI, which (through their adherence to anti-fascist ideology and the defense of the ‘Russian workers' state') were caught in the cogs of capitalism and definitively lost as expressions of the life of the class. Never has history recorded such a divorce between the class and the groups that express its interests and its mission. The vanguard is in a state of absolute isolation and reduced in numbers to a few negligible little groups.

The immense revolutionary wave that sprang from the end of the first imperialist war has put such fear into international capitalism that this long period of disintegration of the proletariat's foundations was necessary to create the conditions for unleashing a new worldwide imperialist war." (Report to the July 1945 Conference of the Communist Left in France)

As we can see, the historic course towards war has its specific manifestations which are sufficiently prolonged and recognizable -- even if they cannot be "quantified" as Battaglia would like -- for us to risk taking up a position.

It might perhaps be said that it is not always easy to recognize such a process -- but it would mean shunning the responsibilities of revolutionaries, and resigning ourselves to impotence and uselessness, to pretend that it is impossible, in a general way, to determine the historic course.

How do we recognize the course towards decisive class confrontations?

The process leading towards the creation of revolutionary situations is very different from that leading towards war. The march towards war does not break with the logic of the dominant system.

For the proletarians, going to war means complete submission to capital at every level ... to the point of sacrificing life itself. There is no fundamental change in the relationship between exploiting and exploited classes. The ‘normal' relationship is simply pushed to one of its most extreme forms.

"In reality, what could be called the ‘normal' course of capitalist society is towards war. The resistance of the working class, which can put this course into question, appears as a sort of ‘anomaly', as something running ‘against the stream', of the organic processes of the capitalist world. This is why, when we look at the eight decades of this century, we can find hardly more than two during which the balance of forces was sufficiently in the proletariat's favor for it to have been able to bar the way to imperialist war (1905-12, 1917-23,1968-80)." (International Review, no.21, second quarter 1980, ‘Revolution or War'.)

In this sense, the course towards rising class struggle is far more fragile, unstable and uneven than the course towards war. Because of this, it can be interrupted and reversed by a decisive defeat in a confrontation with the bourgeoisie, while the course towards war can only be broken by the war itself.

"Whereas the proletariat has only one road to victory -- armed, generalized confrontation with the bourgeoisie -- the latter has at its disposal numerous and varying means with which to defeat its enemy. It can derail its combativity into dead-ends (this is the present tactic of the left); it can crush it sector by sector (as it did in Germany between 1918 and 1923); or it can crush it physically during a frontal confrontation (even so, this remains the kind of confrontation most favorable to the proletariat)." (ibid)

The course towards war and the course towards decisive class confrontations

To take account of this ‘reversibility' of the course towards revolution we prefer to talk of a ‘course towards class confrontations' in trying to understand the present situation.

"The existence of a course towards class confrontations means that the bourgeoisie does not have a free hand to unleash a new world butchery: first, it must confront and beat the working class. But this does not prejudge the outcome of this confrontation, in one way or the other. This is why it is preferable to talk about a ‘course towards class confrontations' rather than a ‘course towards revolution'." (International Review no.35, ‘Resolution on the International Situation', Fifth Congress of the ICC.)

This is why we make less use of the term ‘course towards revolution' ... not because we have overturned our analysis of the question of the present course, as Battaglia claims, trying to raise an unreal polemic which avoids the real questions (as in their public reply to the ‘Address to Proletarian Political Groups' of the ICC's Fifth Congress).

This term, ‘course towards revolution' is justified essentially by the need to insist that there is no third way out of the dilemma: war or revolution. But if it were left at that, such a formulation could imply an outcome which we cannot affirm with certainty, at least not at the present stage of development of the historic course: we know that we are heading towards large-scale confrontations between bourgeoisie and proletariat which will once again pose the question of the revolution, and not towards war. But we cannot predict in advance the outcome of this confrontation.

Revolution during the war?

History gives us far more examples of situations where the balance of forces is totally in favor of the ruling class, than of periods where the proletariat has shaken or really limited bourgeois power. As a result, we have fewer historical references to define the characteristics of what a course towards revolutionary confrontations might be than is the case with a course towards war. All the more so since the experience of the proletariat's previous great revolutionary movements has generally occurred during or immediately after a war (the 1871 Paris Commune, 1905 and 1917 in Russia, 1918-19 in Germany). And the conditions created by war are such that, though they may provoke the development of a wave of revolutionary struggles as in 1914-18, they prevent these struggles from becoming truly international.

War can provoke revolutionary movements -- and may even do so extremely quickly: the first significant strikes in Russia and Germany took place in 1915 and 1916; the revolution broke out ‘only' 2-3 years later. But these 2-3 years were a period of world war, of history speeded up so that, on the level of the balance of class forces, these years were worth decades of exploitation and ‘peaceful' crisis.

However, "... the imperialist war (1914-18) also brought with it a whole series of obstacles to the generalization of revolutionary struggles on a world scale:

-- the division between ‘victorious' and ‘beaten' countries; in the former, the proletariat was more easily prey to the chauvinist poison poured out in huge doses by the bourgeoisie; in the second, while national demoralization created the best conditions for the development of internationalism, it by no means closed the door to revanchist feelings (cf ‘national Bolshevism' in Germany).

-- the division between belligerent and ‘neutral' countries: in the latter countries the proletariat didn't suffer a massive deterioration of its living standards.

-- faced with a revolutionary movement born out of the imperialist war, the bourgeoisie could resort to bringing a halt to hostilities (cf Germany in November 1918).

-- once the imperialist war was over, capitalism had the possibility of reconstructing itself and thus, to some extent, of improving its economic situation. This broke the élan of the proletarian movement by depriving it of its basic nourishment: the economic struggle, and the obvious bankruptcy of the system.

By contrast, the gradual development of a general crisis of the capitalist economy -‑ although it doesn't allow for the development of such a rapid awareness about the real stakes of the struggle and the necessity for internationalism - does eliminate the above obstacles in the following way:

-- it puts the proletariat of all countries on the same level: the world crisis doesn't spare any national economy.

-- it offers the bourgeoisie no way out except a new imperialist war, which it can't unleash until the proletariat has been defeated." (International Review no.26, third quarter 1981, ‘Resolution on the Class Struggle', Fourth Congress of the ICC.)

History does not, therefore, provide us with all the possible characteristics of a period of rising class struggle like today, marked not by war but by society's slow decline into economic crisis.

We can nonetheless identify this course:

-- firstly, because it does not have the essential characteristics of a course towards war;

-- secondly, because it is marked both by the proletariat's progressive disengagement from the grip of the dominant ideology, and by the development of the workers' own class consciousness and combativity.

The present course of history

Battaglia's Fifth Congress does not really take a position on the perspectives for the class struggle. It remains vague ... just as the ICP's Second Congress in 1948 did on the same question (see the article in this issue). But the Congress' Theses do say, as regards the present situation:

"If the proletariat today, faced with the gravity of the crisis and undergoing the blows of repeated bourgeois attacks, has not yet shown itself able to respond, this simply means that the long work of the world counter-revolution is still active in the workers' consciousness." (Synthesis of the General Political Report)

Battaglia has never understood the importance of the historic break with the counter-revolution constituted by the strike wave opened up by May 1968 in France. In reality, BC considers that today, just as in the 1930s, "the long work of the world counter-revolution is still active in the workers' consciousness."

To a large extent, BC still doesn't see the qualitative difference between the 1930s and the 1980s. They do not see that qualitatively different historical conditions are created for the proletarian struggle by the economic crisis' systematic destruction of the ideological mystifications which weigh the proletariat down and which have enlisted it in war in the past.

According to Battaglia's Fifth Congress Theses:

"The fact of having, for decades, yielded first to opportunism, then to the counter-revolution of the centrist parties; the fact of having undergone the weight of the collapse of political myths like Russia or China; the frustration of emotional/political campaigns created artificially around the Vietnam War: these have engendered, in the shock of the vast and destructive economic crisis, a proletariat, that is tired and disappointed, though not definitively beaten." (idem)

It is only normal that BC should observe, at the least, that since the Second World War the proletariat has not been massively crushed and is not "definitively beaten". But, once this is said, BC continues to see no more in the proletariat and its struggles than "the long work of the counter-revolution", tiredness and disappointment.

Let us examine the real situation.

As we have seen above, the existence of working class combativity (strikes, etc) is not enough to determine a course towards revolutionary confrontations. The struggles on the eve of the First World War, steeped in the spirit of reformism, in illusions about democracy and an endless capitalist prosperity; those of the late ‘30s diverted and annihilated in the dead-end of ‘anti-fascism' and so in the defense of ‘democratic' capitalism: these demonstrate that without the development of proletarian consciousness, class combativity is not enough to block the course towards war.

Since the end of the ‘60s, throughout the four corners of the earth, the workers' combativity has undergone, with ups and downs, a renewal that breaks unequivocally with the previous period. From May ‘68 in France to Poland 1980, the working class has shown that it is far from being "tired and disappointed", that its combative potential remains intact and that it has been able to put this potential into action.

What point has class consciousness reached?

Here we can distinguish two processes which, though tightly linked, are nonetheless not identical. Proletarian consciousness develops, on the one hand by its disengagement from the grip of the dominant ideology and, on the other, ‘positively' through the affirmation of the class autonomy, unity and solidarity.

As regards the first aspect, the devastating effects of the economic crisis, which no government -- right or left, East or West -- has been able to check, have dealt some heavy blows to the bourgeois mystifications of the possibility of a prosperous, peaceful capitalism, of the Welfare State, of the working class nature of the Eastern bloc and other so-called ‘socialist' regimes, of bourgeois democracy and the vote as a means of ‘changing things', of chauvinism and nationalism in the most industrialized countries, of the working class nature of the ‘left' parties and their trade union organizations. (For a more extensive treatment of this question, we refer the reader to our previous texts, in particular the Report on the Historic Course adopted at the ICC's Third Congress in IR no.18, third quarter 1979.)

As to the second aspect -- the ‘positive' development of class consciousness -- this can only be evaluated in relation to the proletariat's open struggles considered not in a static or local manner but in their worldwide dynamic. And indeed, the struggles of the last 15 years, from May ‘68 in France to September ‘83 in Belgium. (the strikes in the public sector), while they have not reached a revolutionary degree of consciousness -- which it would be childish to expect at their present stage of development -- are nonetheless marked by a clear evolution towards autonomy from the bourgeoisie's control apparatus (unions, left parties) and towards forms of extension and self-organization of the struggle. The mere fact that the bourgeoisie is more and more systematically obliged to have recourse to ‘rank and file unionism', especially in the ‘democratic' countries, to contain and divert the workers' combativity because the workers are deserting the unions in ever greater numbers, and because the union leaderships are less and less able to make themselves obeyed, is in itself enough to demonstrate the direction of the dynamic of workers' consciousness. Unlike the 1930s, when the workers' struggles were accompanied by increased unionization and the grip of bourgeois forces on the movement, the struggles in our epoch are tending to affirm their autonomy and their ability to go beyond the barriers that these forces erect against them.

Certainly, the proletariat still has a long way to go before it affirms its fully-formed revolutionary consciousness. But if we have to wait for this before taking a position on the present movement's direction -- as Battaglia seems to -- then we might as well give up any hope of a serious analysis of the present course of history.

Battaglia's Fifth Congress seems to have devoted a lot of effort to the analysis of the present economic crisis. This is an important aspect of our understanding of today's historical evolution -- as long as this analysis is correct, which is not always the case. But the best of economic analyses is no use to a revolutionary organization, unless it is accompanied by a correct appreciation of the historic dynamic of the class struggle. And in this sense, Battaglia's Congress is 40 years behind the times.

To judge from the work of its Fifth Congress, all the signs are that, as far as the analysis of the class struggle goes, Battaglia has still not arrived at the years of truth -- the 1980s.

RV

Life of the ICC:

Political currents and reference:

General and theoretical questions:

- Historic course [6]

Inter-imperialist conflicts, class struggle: The acceleration of history

- 2734 reads

"' ... never, since the 1930s, has it been so clear that the capitalist economy is in a total impasse; never since the last world war has the bourgeoisie set in motion such huge military arsenals, so much effort towards the production of the means of destruction; never since the 1920s has the proletariat fought battles on the scale of those which shook Poland and the whole ruling class in 1980-81. However, all this is just the beginning. In particular, although the bourgeoisie is apparently consoling itself by talking about the ‘economic recovery', they have a hard time masking the fact that the worst of the crisis is still ahead of us. Similarly, the worldwide retreat in the workers' struggle following the tremendous fight in Poland is only a pause before enormous class confrontations that will involve the decisive detachments of the world proletariat, those of the industrial metropoles and of Western Europe in particular." (‘Resolution on the International Situation', International Review, no.35)

-----------------------------------------------------

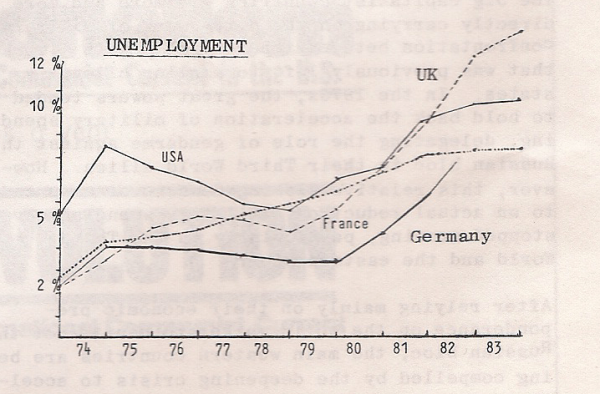

After the 1970s, dominated by the illusion of an economic recovery, the 1980s are indeed Years of Truth. While the development, after the invasion of Afghanistan by Russian troops, of the mass strike by the workers in Poland demonstrated, at the beginning of the 1980s, the concretization of the historical alternative of war or revolution, the years that followed the partial defeat of the world proletariat have been marked by a step forward in imperialist tensions, without the working class showing itself in a significant manner.

Confused by the activity of the left in opposition, and by intensive ideological campaigns around the danger of war, and partly demoralized by the defeat in Poland, the working class struggle has marked time, which has still further facilitated the rapid acceleration in the bourgeoisie's war preparations.

However, capitalism's ever more rapid plunge into the crisis, combined with the fact that the world proletariat remains undefeated, means that this pause in the struggle can only be temporary. Today, the renewal of working class combativity in the central countries is there to show that the reflux is coming to an end.

History is accelerating under the pressure of the deepening crisis. Understanding this acceleration, at the level of inter-imperialist tensions as well as of the class struggle, is an essential task for revolutionary organizations today if they intend to be able to carry out their function in the class tomorrow.

Exacerbation of imperialist tensions

Ever since the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, the proletariat has been subjected to intensive propaganda on the danger of war. Just in these last few months: a Boeing 747 with hundreds of passengers aboard shot down by the Russians over Sakhalin; hundreds of French and American soldiers killed in murderous bomb attacks in Beirut; American marines landing in the miniscule Caribbean island of Grenada; French and Israeli aircraft bombarding the Lebanon -- and all this against a back-drop of long-standing conflicts that not only show no signs of ending, but on the contrary are getting worse: the Iran/Iraq war which has already left hundreds of thousands dead and wounded, the wars in Chad, Angola, Mozambique, the Western Sahara, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Cambodia, etc. There is a long list of wars to illustrate the exacerbation of military tension. And every one a pretext for the intensification of the Western bloc's obsessive bludgeoning designed to paralyze the proletariat with fear or a feeling of its own impotence, and to denounce the Russian bloc's aggression, even when the latter's influence is insignificant.

"Today ... the bourgeoisie has discovered in a muffled but painful way that there is no solution to the crisis. Recognizing the impasse, there is nothing left but a leap in the dark. And for the bourgeoisie a leap in the dark is war." (‘The 80s: Years of Truth', International Review, no.20)

It is in this context that we are witnessing a qualitative change in the evolution of imperialist conflicts. Contrary to the propaganda spewed out daily by all the media of the Western bloc, this evolution's major characteristic is an offensive of the American against the Russian bloc. The Western bloc's aim in this offensive is to completely surround the USSR, and strip it of all its positions outside its immediate influence. The West aims to expel Russia definitively from the Middle East by reintegrating Syria into its bloc. This will include bringing Iran to heel, and resituating it in the US bloc as a major component in the bloc's military apparatus. The ambition is to follow up with the recuperation of Indo-China. In the end, the West aims to strangle Russia completely, and strip it of its super-power status.

One of this offensive's main characteristics is the US bloc's ever more massive use of its military might, in particular through the dispatch of expeditionary forces, either American or drawn from the bloc's other major powers (France, Britain, Italy), onto the terrain of confrontations. This corresponds to the fact that the economic card -- played so frequently in the past to lay hold of the enemy's positions - is no longer adequate:

-- because of the US bloc's present ambitions,

-- and above all because of the aggravation of the world crisis itself, which has created a situation of internal instability in the secondary countries that the US bloc once relied on.

The events in Iran are in this respect revealing. The collapse of the Shah's regime, and the paralysis of the US military apparatus that this provoked throughout the region, allowed the USSR to score points in Afghanistan. This persuaded the American bourgeoisie to set up the rapid deployment force (and allowed it the more easily to force this down the throat of a population traumatized by the affair of the US embassy hostages in Tehran 1979), and reorientate its imperialist strategy.

In the same way today, the difficult economic and social situation of Israel, the Western bloc's most stable military bastion in the Middle East, demands the bloc's direct and growing military presence in the Lebanon.

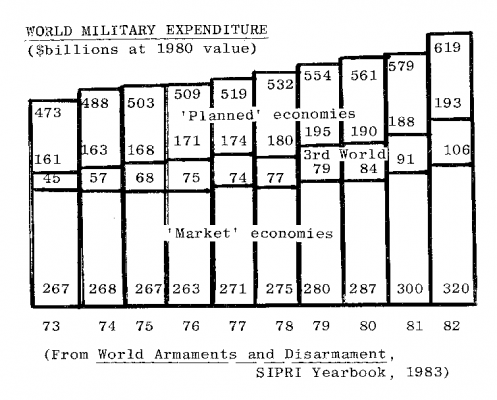

The US bloc's increasing difficulty in maintaining its advance against the Russian bloc through its economic might, as the crisis strikes ever harder, pushes it to subordinate its economy more and more completely to its military requirements. For a long time, the USSR, given its congenital economic weakness, has been obliged to maintain its domination over its bloc by sacrificing economic competivity to the demands of its military strength through the hypertrophy of its war economy. The primacy of the military over the economic is a general tendency of decadent capitalism, which is accelerating today, and which is laid bare by the years of truth.

This tendency is not a sign of capital's strength, but, on the contrary, of its growing weakness. The flight forward into the war economy, and toward war itself, is the product of the collapse of the super-saturated world market. The particularity of armaments production lies in that it is destined to produce neither labor-power, nor means of production, but means of destruction; it is itself a sterilization and a destruction of capital.

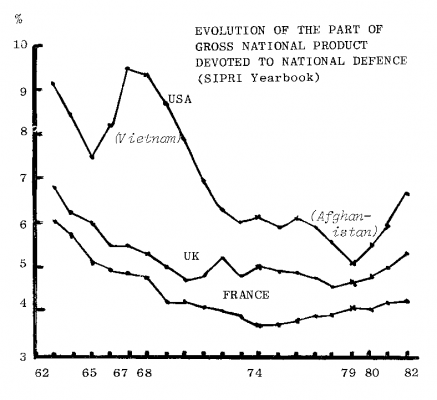

Since the end of the seventies armaments programs have been developing throughout the world. The US state's arms procurements are one of the determining factors in the present economic "recovery". But, in the end, this gigantic destruction of capital only accentuates the effects of the crisis and accelerates the bankruptcy of world capital (see the article in this issue).

The proletariat: a brake on the generalization of conflicts