International Review no.31 - 4th quarter 1982

- 2773 reads

Conditions for the revolution

- 2402 reads

Crisis of overproduction, state capitalism, and the war economy

(Extracts from the report on the international situation, 5th Congress of Revolution Internationale.)

An

understanding of the critique of the ‘theory of the weakest link’

must

not make us forget what the Polish workers actually did. This

struggle showed the international proletariat what a mass movement

looks like, and it posed the problem of internationalization even if

it couldn’t resotlve it -- thus also posing the question of the

revolutionary content of the workers’ struggle in our epoch, which

can’t be separated from the question of internationalization. The

ICC has dealt at length with the question of internationalization and

with the class struggle in Poland1.

On the other hand we haven’t spent enough time talking about the

revolutionary content of the struggle -- a problem the Polish

workers came up against but didn’t understand. However, this

question was still

posed,

particularly with regard to the ‘economic’ question -- as, for

example, when the workers first began to criticize Solidarnosc in an

open, direct way; when, in the name of the ‘national economy’ and

‘self-management’ Solidarnosc directly opposed the strikes

which broke out in the summer of ‘81. During these strikes, to use

their own terms, the workers were prepared

to

put even the most popular Solidarnosc leaders (Walesa and Co.) “in

the cupboard”, and to carry on their strikes “till

Christmas

and longer if necessary”. The only

thing

that stopped them doing so was their lack of a perspective.

In the situation of generalized scarcity which dominates the eastern

bloc countries, the Polish workers left to themselves weren’t able

to go forward. This situation will

inevitably

arise again, but in the developed countries the simultaneous

existence of generalized overproduction and of an

ultra-developed technical apparatus will

make

it possible for the workers to put forward their own revolutionary,

internationalist perspective.

The development of the class struggle and of the objective conditions which determine it -- the crisis of capitalism -- confirms the bankruptcy of all the idealist conceptions which deny the existence of the ‘catastrophic crisis’ of capitalism as an objective basis for the world communist revolution.

The crisis signals the failure of the whole notion of ‘ideology’ being the motor-force of revolution. This notion is, in fact, a rejection of the marxist theory which holds that the relations of production determine all social relations. It’s the failure of the theories of the Situationists, who said of Revolution Internationale's analysis of the crisis in 1969 that “the economic crisis was the eucharistic presence which sustains our religion”. It also means the bankruptcy of the pathetic notion of the Fomento Obrero Revolucionario for whom “will-power” is the motor of revolution. It is the end of the line for all the theories which came out of Socialisme ou Barbarie asserting that state capitalism and militarism represent a third alternative, a historical solution to the contradictions of capitalism.

But affirming that the historic catastrophe of capitalism is the necessary and objective basis for the communist revolution is not enough. Today it is absolutely vital to show why and how it is. This is the aim of the present study.

It is not surprising that all the groups mentioned above defend a ‘self-management’ conception of the revolutionary transformation of society. The present historical situation not only marks end of the line for idealist notions but also for all the populist, third-worldist conceptions supported by the theories of the ‘weakest link’ and the ‘labor aristocracy’ defended particularly by the Bordigist currents.

We not only have to show that the crisis is necessary because it impoverishes the working class in an absolute sense and therefore pushes it to revolt, but also and above all how the crisis leads to revolution because it is the crisis of a mode of production, the crisis of social relations where the nature of the crisis itself, overproduction, poses both the necessity and the possibility of revolution. The very nature of the crisis reveals both the subject and the object of the revolution, the exploited class and the end of all exploiting societies and of scarcity.

The first step in accomplishing this task is to show as clearly as possible the nature of today’s qualitative leap in the economic crisis which has thrown the industrialized metropoles into recession and generalized overproduction.

The period of decadence is not a moment fixed in time, an endless repetition -- it has a history and an evolution. To understand the objective basis of class struggle today, we have to situate the evolution of overproduction and of state capitalism and of their reciprocal relations. In this way we can identify more clearly what we mean by the “qualitative step in the economic crisis” and its consequences for class struggle.

By dealing with all its various aspects -- over-production, state capitalism, militarism -- it will become clear that this qualitative step in the crisis is not just a qualitative leap in terms of the 1970s but in relation to the entire period of capitalist decadence. The crisis today is the crisis of the palliatives which the bourgeoisie has used to deal with the historical crisis of its system up to now. The historical importance of this situation cannot be overestimated.

“The anatomy of man is the key to the anatomy of the ape”, wrote Marx; that is, the higher form of development of a species reveals in finished form the tendencies and developmental lines of embryonic forms in lower species. The same is true for today’s historical situation which reveals, in the highest expression of decadence, the truth and reality of the epoch which goes from the First World War to today.

Overproduction and State Capitalism

State capitalism was never an expression of the health or vigor in capitalism; it was never an expression of a new organic development of capitalism but only:

-- the expression of its decadence;

-- the expression of its ability to react to this decadence.

That’s why in the present situation we have to analyze the relation between the crisis of capitalism in all its different aspects: social, economic and military. We’ll begin with the latter.

Overproduction and Armaments

The overproduction crisis is not only the production of a surplus which finds no market, but also the destruction of this surplus.

“In these crises not only is there destruction of a large amount of goods already produced but also of existing productive forces. A social epidemic breaks out which in any other era would be absurd: the epidemic of overproduction.” (Communist Manifesto)

Thus the overproduction crisis implies a process of self-devaluation of capital, a process of self-destruction. The value of non-accumulatable surplus is not stockpiled but has to be destroyed.

The nature of the crisis of overproduction is clear and unambiguous in the relation between the crisis and the war economy today.

The whole period of decadence shows that the over-production crisis implies a displacement of production towards the war economy. To consider this an ‘economic solution’, even a momentary one, would be a serious mistake. The roots of this mistake lie in an inability to understand that the overproduction crisis is a process of self-destruction. Militarism is the expression of this process of self-destruction which is the result of the revolt of the productive process against production relations.

This displacement of the ‘economic’ towards the ‘military’ could hide the general overproduction only for a certain time. In the 30s and after the war, militarism could still create an illusion. But today the situation of the war economy in the general crisis of capitalism reveals the whole truth.

Today there is an enormous development of armaments, for example in the US where: “The Senate broke a record on December 4th by voting $208 billion for the 1982 defense budget. No American appropriations bill has ever been so huge. The final amount was $8 billion more than President Reagan asked for.” (Le Monde, 9.12.81)

But in the overall situation of world capitalism today, and with the financial situation of the different nations of the world, we have to be aware of the fact that such a policy of armaments spending is a very serious factor deepening the economic crisis, accelerating both recession and inflation.

In the present situation such arms budgets not only in the US but everywhere in the bloc (especially in Germany and Japan) cannot maintain the level of industrial production even in the short run as they did in the 30s or after the war. On the contrary, they are rapidly accelerating the decline of production.

Unlike the 30s, today’s armaments policies do not create jobs or only replace a handful of jobs they eliminate. This situation is heightened by the fact that arms development is not accompanied by social spending and public works projects like in the 30s but is carried out in direct opposition to these policies. Moreover, the jobs created by armaments development today concern only a small proportion of very qualified workers, or of technicians with a scientific background because of the highly developed technology of modern weapons.

Thus weapons development today cannot hide the general crisis of overproduction. In fact, with the deepening of the recession and the acceleration of inflation which arms investment provokes, the crisis of capitalism is also the crisis of the war economy.

“The Reagan government cannot sustain this military spending except by imposing an even more restrictive monetary policy, with a restrictive fiscal policy and a limitation on non-military public spending. All these efforts will lead to an increase in unemployment. Beyond this military Keynesianism, the first military depression of the 20th Century is coming.” (‘Un Nouvel Ordre Militaire’, Le Monde Diplomatique, April 1982)

In this situation, the weight of already-existing weapons and their present increase are seen by the population and particularly by the working class as the direct cause of poverty and unemployment as well as the source of a menacing apocalyptic war. That is why the revolt against war is part of the general revolt of the proletariat even if war isn’t an immediate threat.

It would be simplistic to think that the planning of ultra-modern arms production is the characteristic of the Reagan administration alone. Such industrial preparation cannot be carried out overnight or even in several months. The truth is that the weapons seeing the light of day today were carefully prepared in the 70s under Democratic administrations; but the Democrats couldn’t take direct political responsibility for them without leaving the social front uncovered.

It is not an accident that in today’s historical situation and for the first time in the whole history of decadence, it is the right-wing, the Republicans in the US, who have propelled the armaments policy.

“The military expansion policies in the US are not at all characteristic of the Republicans. The military booms of the last 50 years -- the 1938 expansion, the Second World War, the rearmament of the Korean War and of the Cold War 1950-52, the space and missile boom of 1961-64 and the Vietnam War -- were all inspired by Democratic governments.” (idem)

It is not an accident either that pacifism is today one of the themes preferred by the opposition. We would be wrong to consider pacifism or campaigns over E1 Salvador as only long-term preparations. In the short-term and immediate sense, they contribute to isolating the struggles of the workers in Poland and to getting the so-called ‘austerity’ budgets passed -- budgets which work to the benefit of armaments.

“We must make a distinction between pacifist campaigns today and those which preceded the Second World War. The pacifist campaigns before WWII directly prepared the mobilization of a working class already subjugated by antifascist ideology.

“Today the pacifist campaigns still try to prepare a mobilization for war but it is not their direct, immediate task. Their immediate aim is to counteract class struggle and avoid mass movements in the developed countries. Pacifism today plays the same role as anti-fascism yesterday.

“For the bourgeoisie, it is vital that no link be made between the struggle against war and the struggle against the crisis. That the alternative ‘war or revolution’ isn’t posed.

“For this, pacifism is a particularly efficient weapon because it responds to a real anxiety in the population while separating the questions of war and crisis, posing a false alternative of ‘war or peace’. At the same time it tries to reawaken nationalist sentiments through a pseudo-‘'neutralism’.

“The false alternative ‘war or peace’ in relation to war complements the other false alternative in relation to the crisis, ‘prosperity or austerity’. Thus with the struggle ‘against austerity’ on the one hand and the struggle ‘for peace’ on the other, the bourgeoisie covers all angles of the social revolt. It is the best illustration of what we mean by the ‘left in opposition’.” (from a text of Revolution Internationale of November 1981)

Overproduction and Keynesianism

Just as militarism has never been a field for capital accumulation, so state capitalism in its economic aspects has never been an expression of an organic and superior development of capitalism, of its centralization and concentration. On the contrary it is the expression of the difficulties encountered in the accumulation process. State capitalism, especially in its Keynesian forms, could, like militarism, look convincing from before the war right up to the 70s. Today, the reality is sweeping away the myth.

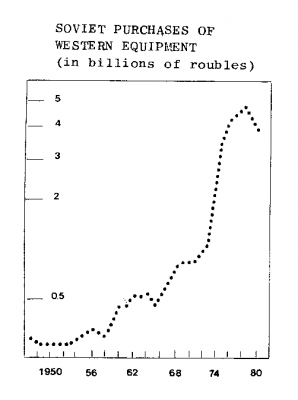

We have often pointed out that, despite the gigantic debts they contract, the under-developed countries are unable to make a real economic ‘take-off’. On the contrary, it has now reached the point where three-quarters of the credits won from the western bloc only serve to repay previous debts. But this indebtedness is not a privilege of the under-developed countries. What is remarkable is that indebtedness is characteristic of the whole of capitalism, from east to west2, and this is not altered by the many different forms that it takes in the west. As for state capitalism as an economic ‘rudder’, this policy of indebtedness and deficit has finally got the upper hand, far more than the policy of ‘orienting’ the economy. It is the economy that has imposed its laws on the bourgeoisie, and not the bourgeoisie that has ‘oriented’ the economy.

“The US became the ‘locomotive’ for the world economy by creating an artificial market for the rest of its bloc by means of huge commercial deficits. Between 1976 and 1980, the US bought $100 billion worth of foreign goods, more than they sold abroad. Because the dollar is the worldwide reserve currency, only the US could put such a policy into practice without being forced to carry out a massive currency devaluation. Afterwards, the US flooded the world with dollars by means of an unprecedented expansion of credit in the form of loans to under-developed countries and to the Russian bloc. This mass of paper money temporarily created an effective demand which allowed world commerce to continue.” (Report on the economic crisis to the 4th ICC Congress, International Review 26)

Here we can take the example of the world’s second economic power to illustrate another aspect of reflation through indebtedness and state deficits:

“Germany set itself to play the ‘locomotive’ yielding to the pressure, it must be said, of the other countries….. The increase in government spending has nearly doubled, growing 1.7 times, like the national product. To the point where half of the latter is centralized by the public sector .... Thus the growth in the public sector debt has been explosive. This indebtedness, stable at around 18% of GNP at the beginning of the 70s, passed abruptly to 25% in 1975, then to 35% this year; its share has thus doubled in ten years. It has reached a level unheard of since the bankruptcy of the inter-war years .... The Germans, who have long memories, are again haunted by the specter of wheelbarrows filled with banknotes of the Weimar Republic.”3 (L’Expansion, 5.11.81)

And rather as in the under-developed countries, the debt is so great that “the debt’s servicing absorbs more than 50% of new credits”.

Here is the hidden face of the late 70s ‘reflation’, the ‘secret revealed’ of the cures that have proved worse than the illness.

At the 4th ICC Congress, as well as in other reports and articles published since, we have shown at length that this policy of the late 70s had come to an end. The world’s states have used it to the point that, were they to pursue it, they would head rapidly for financial disaster and an immediate economic collapse. The 1979 dollar crash was the first sign of this disaster, was the clearest signal for the need to change economic policy, of the end of the ‘locomotives’, and of further indebtedness4.

In the light of the development of the economic situation, we can make a first appraisal of the ‘new economic policy’, of ‘austerity’. Here again the US provides a reference point. The most advanced in the policy of ‘indebtedness’, they have also been fist in the policy of ‘monetarism’. The result has not been brilliant; they have certainly avoided collapse, but at what a price.

Production has fallen incredibly in every sector except armaments, and 15% of the working class is now unemployed... We have seen a decline in inflation over these last few months in all the developed countries ... except in France. But here again, the fall in inflation is essentially due to the fantastic fall in production: “The White House has not neglected to celebrate this success. In reality, it is the recession that explains the fall in inflation, rather than this being a sign of a possible reflation.” (Le Monde de 1’Economie , 6.4.82 )

At all events, in the coming months, the problem of ‘financing the crisis’ will be posed still more acutely for the whole of world capital since:

1. the fall in production is necessarily accompanied by a proportional fall in state income, made worse by the tax reductions that the different states are obliged to make to maintain a minimum level of production;

2) the increase in military spending is a considerable weight for all their budgets;

3) the increase in unemployment is itself a cause of deficits in the benefits system.

In all these budgets, only the benefits systems can be put in question, along with the so-called ‘social’ budgets ... education, health, transport, etc. Thus a fall in the social budgets brings about, not an increase in production, but a new fall in the social budgets; falling production brings about ... falling production.

“Having presented himself as the champion of the balanced budget, Mr. Reagan is beating all the records: a deficit of $100 billion is forecast for 1982, and more for the year after.” (Le Monde, 3.4.82)

In fact, capitalism it ‘stuck’: to avoid financial collapse and disaster it provokes a collapse in production whose only advantage -- and even this is not certain -- is that of being controllable.

When economists interpret Reagan or Thatcher’s policies as being less ‘statified’, this is an absurdity. It is not a changed orientation that makes the state’s economic policy less ‘statist’. While the Keynesian aspect of state capitalism is dead, this does not mean that state capitalism is dead, nor that the economic system has been left to its fate. Although no longer able to stave off collapse by a forward flight, the state has not given up. It is resolved to follow the only economic policy open to it: to slow down, and unify throughout the planet, the collapse of capitalism.

Thus the world’s states are organizing the decline into generalized recession, on a worldwide scale. Such a historical situation holds a number of and implications:

and of further indebtedness (5). 1) With the end of the Keynesianism that maintained an artificial level of capitalist activity, the possibility of polarizing ‘wealth’ in some nations and ‘poverty’ in others is wearing out. The situation in Belgium is, on a small scale perhaps, but in caricature, a striking illustration of this process:

“Belgium has become the sick man of' Europe. Its prosperity after the war, which its neighbors considered ‘insolent’, has progressively declined to the point where today its situation has become literally catastrophic. A budget deficit five times that of France, a more and more unstable balance of' payments, an incredibly high level of debt (both internal and external), unemployment reaching 12% of the active population and, above all, a growing deindustrialization: all risk making this nation, once one of Europe’s lynch-pins, an under-developed country. One thing is sure, and a worry for all Europeans: for Belgium, but also for the Ten, the hour of truth has struck.” (Le Monde, 23.2.82 )

2) During the 70s, state deficits and indebtedness were the most effective weapons for holding off class struggle, and spreading illusions among the workers of the eastern bloc. The end of this situation, and the setting up in the developed countries of a ‘fortress state’, policed and militarized to the utmost, which accompanies the collapse of capitalism, and makes the workers pay directly for the crisis because it can do nothing else, poses new objective conditions.

of deficits in the benefits system. Today, the objective conditions are changing qualitatively in relation to the 70s. But this is true not only in relation to the 70s, but also to the whole period of decadence. In relation to the 30s, the bourgeoisie no longer possesses the economic means to contain the working class. The 30s were years of a ‘great take-off’ of state capitalism, especially in its Keynesian aspects. If we take the example of the US in the 30s, we can see that:

“The gap between production and consumption was attacked on three fronts at once:

1) contracting a constantly growing mass of debts, the state carried out a series of vast public works …

2) the state increased the purchasing power of the working masses,

a) by introducing the principle of labor contracts guaranteeing minimum wages, and limiting the working day, while at the same time strengthening the overall position of workers’ organizations, and especially of unionism;

b) by creating a system of unemployment insurance, and through other social measures designed to prevent a new reduction in the living standards of the masses.

3) moreover, the state tried, through measures such as the limiting of agricultural production and subsidies for agricultural products, to increase the income of the rural population, and to bring the majority of farmers up to the level of the urban middle classes.” (Sternberg, The Conflict of the Century)

During the 30s, the measures of the ‘New Deal’ were taken after the worst of the economic crisis. Today, not only is the ‘New Deal’ of the 70s behind us and the worst of the crisis ahead without any possibility of war offering a way out; we also have not seen in the developed countries such a wave of unionization and ideological enrolment as characterized the 30s. On the contrary, since the mid-70s, we have seen a generalized de-unionization, whereas during the 30s, as Sternberg reports:

“Due to the decisive modifications to the American social structure carried out under the aegis of the New Deal, the situation of the unions was totally changed. The New Deal in fact encouraged the unions by every means possible ... In the brief period between 1933 and 1939, the number of union members more than tripled. On the eve of World War II, there were twice as many paid-up members as in the best years before the crisis, many more than at any other moment of American union history.” (idem)

3) The present historical situation is a complete refutation of the theory of state capitalism as a ‘solution’ to the contradictions of capitalism. Keynesianism has been the main smokescreen hiding the reality of decadent capitalism. With its bankruptcy, and the fact that states can now do no more than accompany capital in its collapse, state capitalism appears clearly for what it has always been: an expression of capitalism’s decadence.

This observation does not have a merely theoretical and polemical interest as against those who presented state capitalism as a ‘third road’. It is extremely important from the standpoint of the objective conditions and their links with the subjective conditions of the class struggle in relation to the question of the state.

It is not enough to consider state capitalism as an expression of capital’s decadence. Capitalism has only been able to ‘settle’ into decades of decadence after having broken the back of the revolutionary proletariat, and in this task state capitalism has been at the same time one of the greatest results of, and one of the most important methods of, the counter-revolution. Not only from a military, but above all from an ideological point of view.

In the revolutionary wave at the beginning of the century, in the 30s and in the reconstruction period, the question of the state has always been at the centre of the proletariat’s political illusions and of the bourgeoisie’s ideological mystifications. Whether it be the illusion that the state, even the transitional one, is the tool of social transformation and of the proletarian collectivity, as in the Russian revolution; whether it be the myth of the defense of the ‘democratic’ state against the ‘fascist’ state during the war and the 1930s; or whether it be the ‘social’ state of the reconstruction period, or again the ‘savior’ state of the left in the 70s -- throughout, the proletariat is led to think that everything depends on the ‘form’ of state, that it can only express itself through a particular form of state; always, the bourgeoisie maintains in the proletariat a spirit of delegation of power to a representative or to an organ of the state, as well as an attitude of ‘dependency’. It is these myths, widely diffused by the dominant mode of thought; these illusions constantly maintained within the working class, that Marx was already fighting against when he declared: “Because, (the proletariat) thinks in political forms, it sees will as the reason for all abuses, and sees violence and the overthrow of a determined form of state as the means to set them right.” (Marx’s emphasis: Critical Notes on the Artical, The King of Prussia and Social Reform, by a Prussian).

During the last few decades, the working class has lived through all the possible and imaginable forms of the last form of the bourgeois state, state capitalism -- Stalinist, fascist, ‘democratic’ and Keynesian. Not much mystification is left as to the fascist or Stalinist states: the few illusions left as to the Stalinist state have been swept away by the struggle of the Polish workers. By contrast, the democratic Keynesian state has maintained the strongest illusions among the workers.

The end of the Keynesian state in the developed, and therefore key countries, does not mean that the question of the state has been dealt with. On the contrary, it is beginning to be posed in reality with the setting up of the state of open conflict, which throws the left into opposition, and prepares to confront the working class. But in these conflicts, the proletariat will have already experienced the various forms of state that decadent capitalism can take on, and the various ways it has been done down by these various forms.

The question of the destruction of the state is posed by the unity between the objective conditions where state capitalism appears not as a superior but as a decadent form, and the subjective conditions made up of the proletarian experience.

In this conflict, our task is: first, to remind the proletariat of its previous experience, and secondly, to put it on guard against the supposed ease of the struggle by showing, precisely through its experience, that if state capitalism is a decadent expression it is also an expression of the bourgeoisie’s ability to adapt itself, to react, and not to give up without a fight.

The fortress state

If we were to advance a first conclusion from analyzing the relation between the economic crisis, militarism, and state capitalism, with all the implications, objective as much as subjective that we have tried to draw from each of these points, we can say that:

1) The bourgeois state is not giving up the game; it is being transformed into a fortress-state, policed and militarized to the hilt.

2) No longer able to play on the economic and social aspects of state capitalism to put off the crisis and the class struggle, the fortress-state is not waiting hands in pockets for the proletariat to mount the attack, nor is it simply retreating into the ‘fortress’. On the contrary, it is taking the initiative in the battle outside the fortress, on the terrain where everything is decided: the social terrain. This is the fundamental meaning of what we call the ‘left in opposition’, a movement which is clearly to be seen today in the major industrialized metropoles.

3) With the groundwork being prepared by the left in opposition, the state is developing two essential aspects of its policy:

-- repression and police control;

-- vast and ever more spectacular ideological campaigns (a real ideological terrorism) on all the questions posed by the world situation: war, the crisis, and class struggle.

This is the fundamental meaning of the campaigns for ‘peace’, for ‘solidarity’ with Poland, over El Salvador or the Falklands, and the incessant anti-terrorist campaigns.

4) The question of the state, of its relation to the class struggle, can only really be posed in the developed countries, where the state is strongest materially and ideologically.

Even if the anachronism of state structures in the under-developed countries, or even in the eastern bloc, forms born of the counter-revolution, makes them ill-adapted to face up to the class struggle, experience has shown how in Poland the bourgeoisie was able to turn this anachronism, weakness, into weapons of mystification against the struggle as long as the workers in the developed countries did not themselves enter the fight. The struggle for ‘democracy’ in Poland is the best example of this.

In any case, the weakness or inadequacy of states in less-developed countries is largely compensated by the unity of the world bourgeoisie and its different states when confronted with the working class.

Similarly, it would be dangerous and wrong to say that the states in developed countries have been weakened in the face of class struggle because of the profound unity that the bourgeoisie has shown in these countries -- unlike the underdeveloped countries where the bourgeoisie can play on its divisions to mislead the workers.

Faced with the stakes of the world situation and the class struggle, it is not so much ‘regional’ divisions, for example, that will be the axis of the bourgeoisie’s work against the proletariat.

The essential axis of the bourgeoisie’s work of undermining can only be a false division between right and left, and the ability to set up this false division depends precisely on the bourgeoisie’s strength, on the strength of its unity.

We must therefore warn against the illusion that the fight against the bourgeois state will be easier in the advanced countries.

Overproduction and technical development

In the first part of this report, we tried to show how over-production is also destruction, waste, and implies for the proletariat an intensified exploitation and declining living conditions. This aspect of our critique of the economy is extremely important: firstly, of course, for understanding the evolution of the crisis, and secondly, for our propaganda. The bourgeoisie has not and will not miss an opportunity to explain (as it already has in Poland) that the workers’ struggle worsens the crisis, and is therefore “to everyone’s disadvantage”. To this, we must reply: so much the better if the proletariat accelerates the economic crisis and the collapse of capitalism without leaving the bourgeoisie and the crisis time to destroy a large part of the means of production and consumption, because the crisis of over-production is also destruction.

But in showing how the crisis of over-production is also destruction, we have only shown one aspect of capitalism’s historic and catastrophic crisis. In fact, the crisis of over-production produces not only destruction, but also an extensive technical development (we shall see later that this is not at all contradictory). The development of the crisis of over-production shows us that overproduction is accompanied not only by the destruction or ‘freeze’ of commodities and productive forces, but also by a tendency to the development of the productivity of capital, to compensate for the general over-production and the falling rate of profit in a context of bitter competition. This is why, in recent years, alongside the de-industrialization of old sectors like steel, textiles and shipbuilding, we have seen the development of other high-technology sectors mentioned above, the whole being accompanied by a concentration of capital.

So, just as all the measures taken to confront the crisis of over-production, and Keynesianism in particular, have only provoked a still more gigantic crisis of over-production, so technical advance has only pushed the contradiction between the relations of production and the development of the forces of production to its utmost.

During the last decade in particular, we have seen a fantastic development of technology on all fronts:

1) - development and application to production of automation, robotics and biology;

- development and application of computers to management and organization;

- development of the means of communication: transportation (especially aeronautics); audio-visual communications, telecommunications and distributed computer processing.

2) And, to support all this, ‘appropriate’ energy supplies, in particular nuclear energy.

For the bourgeoisie, ideologically, we are on the verge of a third ‘industrial revolution’. But for the bourgeoisie, this third ‘industrial revolution’ cannot avoid provoking great social upheavals, and moreover cannot take place without a world war, without a gigantic ‘clean-up’ and redivision of the world. The present economic and military policies of the capitalist world are being put into practice within this perspective, and not simply to confront the immediate situation of the economic crisis.

In an immediate sense, the bourgeoisie worldwide is trying to maintain production as far as it can, and to avoid a brutal economic collapse. But whether it be in the social, military, or economic domain, we must understand that the bourgeoisie is not acting from one day to another, but that it has a definite perspective, which we would be wrong not to take account of. It would be wrong, and we would pay for it dearly, to cry victory simply because the unemployment rates have soared, and to content ourselves with saying ‘how stupid the economists are’. We would be wrong not to take account of the present phenomena and ideologies, and to give them all the importance they deserve. Not only in order to criticize the bourgeoisie on the question of what they call ‘restructuring’ and unemployment, but still more to overthrow their arguments as to the future of this ‘third industrial revolution’ and to give our own vision of what is at stake in the present epoch of human history.

The development of certain techniques of the productivity of labor is in no way contradictory with the development of the economic crisis. This technical development is essentially invested in non-productive sectors:

a) Firstly, armaments: the ‘Falklands war’ and the ultra-modern techniques used there (electronics, satellites, etc) give us an idea of what this famous ‘third industrial revolution’ really means.

b) Secondly, in ‘service’ sectors: offices, banks, etc.

In this way, the growth in productivity (which in fact is mainly only potential) is accompanied by an overall deindustrialization, and is far from compensating for the vertiginous fall in production. This is the case for the world’s major power which alone accounts for 45% of world production -- the United States:

“Dividing the labor force into two categories -- those who produce means of consumption or production and those who produce services -- the weekly Business Week shows that the number of jobs is falling in the first category (43.4% in 1945, 33.3% in 1970, 28.4% in 1980, with 26.2% projected for 1990) and rising in inverse proportion in the second sector (56%, 66.7%, 71.6%, 73.8% respectively) .... American big business has for several years gone on a sort of productive investment strike.” (Le Monde Diplomatique, March 1982)

Moreover, when productivity does develop in production, it provokes gigantic unemployment, and subjects those who remain in work to a ‘deskilling’ of their labor, and to very difficult and highly policed working conditions. The ‘benefits’ are restricted to a tiny minority of highly qualified technicians.

As for the question of the ‘industrial revolution’ itself, the bourgeoisie is aware, because it is directly confronted with the problem, that the world market as it is today, already saturated by the old methods of production cannot provide a springboard for its development.

In its ideology, only a world war could ‘prepare the ground’ for a large-scale development and application of modern production techniques. Anyway the bourgeoisie has no choice.

This is why most of the preparation for this famous ‘industrial revolution’ takes place in the field of armaments, which is where all the best of humanity’s scientific technique is developed and applied.

The same is true for the development of productivity and over-production: both lie within the framework of the bourgeois system of destruction. This is what we have to say to the working class. And that, through the development of present-day technical methods and over-production, capitalism has pushed the antagonism between the productive forces and the relations of production to its extreme limits.

“In the epoch when man needed a year to produce a stone axe, several months to make a bow, or made a fire by hours of rubbing two sticks together, the most cunning and unscrupulous businessman could not have extorted the least surplus labor. A certain level of labolr productivity is necessary for a man to be able to provide surplus labor.” (R. Luxemburg, Introduction to Political Economy)

For a relationship of exploitation to be installed and to divide society into classes, a certain level of productivity was necessary. Alongside the labor necessary to ensure the subsistence of the producers, there had to develop a surplus labor allowing the subsistence of the exploiters, and the accumulation of the productive forces.

The whole history of humanity from the dissolution of the primitive community to the present day is the history of the evolution of the relation between necessary and surplus labor -- this relationship being itself determined by the level of labor productivity -- which determines particular class societies, particular relations of exploitation between producers and exploiters.

Our historical epoch, which starts at the beginning of this century, has totally reversed the relation between necessary and surplus labor. Through technical development, the share of necessary labor has become minute in relation to surplus labor.

Thus, if the appearance of surplus labor allowed, in certain conditions, the appearance of class society, its historical development in relation to necessary labor has completely reversed the problematic of societies of exploitation and poses the necessity and possibility of the communist revolution, the possibility of a society of abundance, without classes and without exploitation.

The historical crisis of capitalism, the crisis of over-production determined by the lack of solvent markets has pushed this situation to its extreme. To face up to over-production, the bourgeoisie has developed the productivity of labor, which has in its turn worsened the crisis of overproduction, all the more so since world war has not been possible.

Today, this revolt of the productive forces against bourgeois relations of production, expressed in over-production, the productivity of labor and their reciprocal relations, has reached a culmination, and has burst out into the open.

The conditions of the class struggle in the developed countries

“While the proletariat is not yet developed enough to constitute itself as a class, while, as a result, the proletariat’s struggle with the bourgeoisie has not yet a political character, and while the productive forces are not yet developed enough within the bourgeoisie itself to allow an appreciation of the material conditions necessary to the liberation of the proletariat and the formation of a new society, its theoreticians are only utopians .... and they see in misery nothing but misery, without seeing its subversive side, which will overthrow the old society.” (Marx, The poverty of Philosophy)

With the situation that we have just described as a starting-point, we can understand, that the economic crisis is not only necessary for the revolution because it exacerbates the misery of the working class, but also and above all because it reveals the necessity and the possibility of the revolution. For all these reasons, the economic crisis of capitalism is not a mere ‘economic crisis’ in the strict sense, but the crisis of a social relation of exploitation which contains the necessity and possibility of the abolition of all exploitation; in this sense, it is the crisis of the economy, full stop.

From this viewpoint, the objective and subjective conditions for the revolutionary initiative, for an international generalization of the class struggle, are posed only in the developed countries, and it is in these countries that the whole revolutionary dynamic essentially depends.

This is no different from what revolutionaries have always thought:

“When Marx and the socialists who followed him imagined the coming revolution, they always saw it as springing up in the industrial heart of the capitalist world, whence it would spread to the periphery. This is how F. Engels expressed it in a letter to Kautsky of 12 November 1882, where he deals with the different stages of transition, as well as the problem posed for socialist thought by the colonies of the imperialist powers: ‘Once Europe, along with North America, is reorganized, these regions will possess such colossal power, and will give such an example to the semi-civilized countries, that these will have to let themselves be drawn along, if only under the pressure of their economic needs.’”(Sternberg, The Conflict of the Century)

The process of the communist revolution being nothing other than the process of unification of the proletarian struggle on a world scale, we are not here rejecting from this process the struggle of workers in less developed counties, and in particular the struggle of the workers in the eastern bloc; we are simply affirming that from the standpoint of its objective and subjective conditions, the revolutionary dynamic can only receive its impulse from the developed countries. This understanding is vital for the unity of the world working class, and does not undermine this unity. On the contrary. The working class’ being has always been revolutionary, even when the objective conditions were not. It is this situation that has determined the great tragedies of the workers' movement. But the great revolutionary struggles have never been in vain, without historic consequences. The workers’ struggles of 1848 showed the necessity of workers’ autonomy; the struggle of the Commune in 1871, the necessity of the total destruction of the bourgeois state. As for the Russian revolution and the revolutionary wave of 1917-23, which took place in historic conditions that were ripe, but unfavorable (the war), these have been an inexhaustible source of lessons for the proletariat. The resurgence of the class struggle in the heart of capitalism, the ending of the period of counterrevolution, has already begun to show, in the context of a generalized economic crisis, what the revolutionary dynamic of our epoch will be like.

Annex I:

Overproduction and the agricultural crisis

The agricultural crisis is a question we have seldom dealt with, and yet the development today of the general crisis of capitalism also implies a development of the agricultural crisis which cannot help having important consequences for the condition of the working class. Moreover, we can see in the agricultural crisis a striking illustration of two aspects of capitalism’s historic crisis, firstly its generalized nature, and secondly over-production.

On the generalized aspect of the crisis, Sternberg writes in The Conflict of the Century:

“The 1929 crisis was characterized ... both its industrial and its agrarian nature ... This is another phenomenon specific to the crisis of 1929, and which had never appeared during the crises of the 19th Century. The disaster of 1929 struck the USA as violently as Europe and the colonial countries. Furthermore, it was not just a crisis of cereal production, but covered the whole range of agricultural production ... In such conditions, this latter could only aggravate the industrial crisis.”

And as for the agricultural crisis as an illustration of the overall nature of the crisis, we cannot be clearer than Sternberg:

“Nowhere, tin fact, did the particular character of the capitalist crisis appear as clearly as in the agricultural crisis. Under the forms of social organization preceding capitalism, crises were marked by a lack of production, and given the dominant role of agricultural production, by a lack of food production.

... But during the crisis of 1929, too much foodstuff was produced, and hundreds of thousands of farmers threatened with eviction ... while in the cities, people were often unable to buy the most essential supplies.”

We would be wrong to underestimate the question of the agricultural crisis of over-production, whether in our analyses, our interventions, or our propaganda.

In our analyses of the crisis, because its development will become more and more important for the condition of the working class. Up till now, ie during the 70s, agricultural over-production was masked and soaked up by state subsidies which maintained agricultural prices, and therefore production. At present, this policy of subsidies, just as for industrial production, is drawing to an end or being seriously reduced. It’s enough to look at the agricultural over-production in Europe and the stir it has provoked in recent months to be convinced. This is true for Europe, but still more so for the US which is one of the world’s foremost agricultural producers: “American farmers are tearing their hair out. 1982 will, they say, be their worst year since the great depression ... The crisis is essentially due to over-production, as if the technical progress which has been so profitable for the Middle West was beginning to turn against it…. In 1980 they accounted for 24.3% of world rice sales, 44.9% of wheat, 70.1% of corn and 77.8% of peanuts. At present, one hectare out of every three cultivated ‘works’ for export. The Americans are thus very sensitive to the contraction of external markets provoked by the difficulties of the world economy.” (Le Monde)

From the standpoint of our propaganda, such a situation of over-production in agriculture couldn’t illustrate better the total anachronism of the continued existence of capital, and what humanity will be capable of achieving once rid of the commodity system, the armaments sector and other unproductive sectors. Humanity is in a position never known before now:

“Present cereal production alone could provide in the every man, woman and child with 3000 calories and 65 grams of' protein per day, which is largely superior to what is necessary, even when generously calculated. To eliminate malnutrition, it would be enough to redirect 2% of world cereal production to those who need it.” (World Bank: Report on World Development)

Annex II:

Unemployment and indebtedness

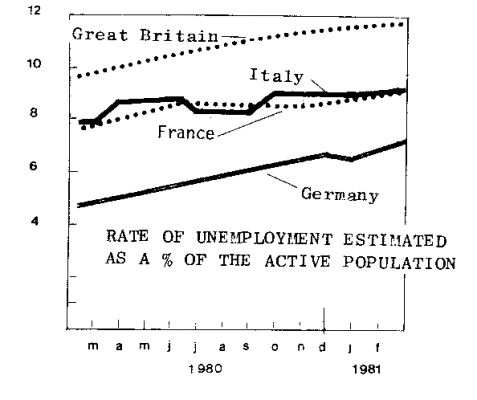

In the USA, unemployment has reached over 10 million. The rate of unemployment is the highest since the Second World War. It is 14% among workers in general and 18% among blacks.

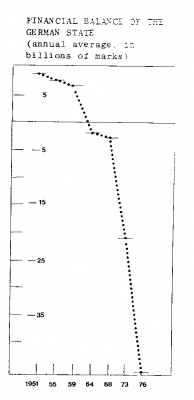

These two graphs illustrate how indebtedness isn't just a characteristic of the under-developed countries, but of the whole of world capitalism.

The indebtedness of the Federal Republic of Germany has nearly doubled since 1973, in proportion to the GDP, of which it now represents nearly 35%. It is approaching the levels reached after the monetary collapse of the Weimar Republic.

1 See International Review no 23 and no 27.

2 It is interesting to note here the parallel Keynes himself drew between militarism and the state capitalist measures he advocated: “It appears to be politically impossible for capitalist democracy to organize expenditure on the scale necessary to realize the grandiose experiences which would confirm my argument – except in conditions of war.” (General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money)

3 See Annex II

4 See Annex II (graphs on indebtedness)

Life of the ICC:

- Congress Reports [1]

- Life in the ICC [2]

Machiavellianism, and the consciousness and unity of the bourgeoisie

- 4114 reads

The two articles that follow are the product of discussion that has been animating the ICC: their main aim is to investigate the bourgeoisie's level of consciousness and capacity for maneuvering in the period of decadence. This is part of the debate on the Machiavellianism of the bourgeoisie, which was one of the issues which gave rise to the ‘tendency' which left the ICC about a year ago[1]. This somewhat informal tendency split into several groups on leaving the ICC: L'Ouvrier Internationaliste (France) and ‘News of War and Revolution' (Britain), which have since disappeared, who together with ‘The Bulletin' (Britain) all made the same critique of the ICC: we have a Machiavellian view of the bourgeoisie and a conspiratorial views of history. Other groups like ‘Volunte Communiste' or ‘Guerre de Classe' in France also accuse the ICC of overestimating the consciousness of the bourgeoisie[2].

But this discussion isn't simply about the concrete question of how the bourgeoisie maneuver in its decadent period: it is also poses the more general question of what the bourgeoisie is, and what this implies for the proletariat.

Why the bourgeoisie is Machiavellian

First let's recall who Machiavelli was: this will help us to understand what we mean when we talk about machiavellianism.

We don't intend here to make an exhaustive analysis of Machiavelli's work and the time he lived in. Our aim is to understand his contribution to the building of bourgeois ideology.

Machiavelli was a statesman in Florence at the time of the Renaissance. He is best known for his book The Prince. Obviously Machiavelli, like every man, was bound to the limits of his own period, and his understanding was conditioned by the relations of production of that time, the decadent period of feudalism. But his time was also one in which a new class was rising towards power: the bourgeoisie, which was beginning to dominate the economy. The bourgeoisie was the revolutionary class of the period, and was soon aspiring towards political domination over society. Machiavelli's The Prince was not only a faithful portrait of the time in which it was written, a reflection of the perversity and duplicity of governments in the 16th and 17th centuries, Machiavelli first of all understood the ‘effective truth' of the policies of states in his day: the means matter little, the essential thing is the end -- conquering and maintaining power. His concern was above all to teach the princes of that time how to hold on to what they'd acquired how to avoid being dispossessed by somebody. Machiavelli was the first to separate morality from politics, ie, religion from politics. He took up an entirely ‘technical' standpoint. Of course, princes had never governed their subjects for their own good. But under feudalism, princes didn't understand reasons of state very well, and Machiavelli set out to teach them about it. Machiavelli said nothing new when he said that princes must lie if they are to win, or when he pointed out that they rarely kept their word: all this had been known since the days of Socrates. The life of princes -- their cynicism, their lack of faith -- was conditioned by the overwhelming power they already possessed. Having assimilated their cynicism, all that remained for Machiavelli to do was to put faith in question. This is what he did when he questioned morality and its underlying support: religion. In matters of state, means aren't important. Thus, by rejecting all moral prejudices in the exercise of power, Machiavelli justified the use of coercion and opted for the rejection of religion in order for a minority to rule over the majority.

This is why he was the first political ideologue of the bourgeoisie: he freed politics from religion. For him, as for the newly rising class, the mode of domination could be atheistic even while making use of religion. While the previous history of the Middle Ages hadn't known any ideological form other than religion, the bourgeoisie was gradually developing its own ideology which would rid itself of religion while still using it as an accessory. By destroying the link between politics and morality, between politics and religion, Machiavelli destroyed the feudal concept of the divine right to power: he made a bed for the bourgeoisie to lie on.

Actually, the princes Machiavelli was teaching were ‘the princes of the bourgeoisie', the future ruling class, because the feudal princes couldn't listen to his message without at the same time undermining the bases of feudal power. Machiavelli expressed the revolutionary standpoint of the time: that of the bourgeoisie.

Even in its limitations, Machiavelli's thought didn't just express the limitations of the time, but of his class. When he presented ‘effective truth' as eternal truth, he wasn't so much expressing the illusion of the epoch but the illusion of the bourgeoisie, which like all previous ruling classes in history, was also an exploiting class. Machiavelli posed explicitly what had been implicit for all ruling, exploiting classes in history. Lies, terror, coercion, double-dealing, corruption, plots and political assassination weren't new methods of government: the whole history of the ancient world, as well as of feudalism, showed that quite clearly. Like the patricians of ancient Rome, like the feudal aristocracy, the bourgeoisie was no exception to the rule. The difference was that patricians and aristocrats ‘practiced machiavellianism without knowing it', whereas the bourgeoisie is machiavellian and knows it. It turns machiavellianism into an ‘eternal truth', because that's how it lives: it takes exploitation to be eternal.

Like all exploiting classes, the bourgeoisie is also an alienated class. Because its own historic path leads it towards nothingness, it cannot consciously admit its historic limits.

Contrary to the proletariat, which as an exploited class and a revolutionary class is pushed towards revolutionary objectivity, the bourgeoisie is a prisoner to its subjectivity as an exploiting class. The difference between the revolutionary class consciousness of the proletariat and the exploiters' class ‘consciousness' of the bourgeoisie is thus not a question of degree, of quantity: it is a difference in quality.

The bourgeoisie's view of the world inevitably bears with it the stigma of its situation as an exploiting, ruling class, which today is no longer revolutionary in any way -- which, since capitalism entered into its decadent phase, has no progressive role to play for humanity. At the level of its ideology, it necessarily expresses the reality of the capitalist mode of production which is based on the frenetic search for profit, on the most vicious competition and the most savage exploitation.

Like every exploiting class, the bourgeoisie cannot, despite all its pretensions, help displaying in practice its absolute contempt for human life. The bourgeoisie was first of all a class of merchants for whom ‘business is business' and ‘money has no smell'. In his separation between ‘politics' and ‘morality', Machiavelli was simply translating the bourgeoisie's usual separation between ‘business' and morality. For the bourgeoisie human life has no value except as a commodity.

The bourgeoisie doesn't only express this reality in its general relationships with the exploited class, above all the most important one, the working class: it also expresses it within itself, in the very fibers of its being. As the expression of a mode of production based on competition, its whole vision can only be a competitive one, a vision of perpetual rivalry among all individuals, including within the bourgeoisie itself. Because it's an exploiting class, it can only have a hierarchical vision. In its own divisions, the bourgeoisie simply expresses the reality of a world divided into classes, a world of exploitation.

Since it has been the ruling class, the bourgeoisie has always buttressed its power with the lies of ideology. The watchword of the triumphant French republic in 1789 - ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity' -- is the best illustration of this. The first democratic states, arising out of the struggle against feudalism in England, France or America, didn't hesitate to use the most repulsive, ruthless methods to extend their territorial and colonial conquests. And when it came to augmenting their profits they were prepared to impose the most brutal repression and exploitation on the working class.

Up to the 20th century the power of the bourgeoisie was based essentially on the strength of its all-conquering economy, on the tumultuous expansion of the productive forces, on the fact that the working class could, through its struggle, win real improvements in its living conditions. But since capitalism entered into its decadent phase, into a period marked by the tendency towards economic collapse, the bourgeoisie has seen the material basis of its rule undermined by the crisis of the economy. In these conditions, the ideological and repressive aspects of its class rule have become essential. Lies and terror have become the method of government for the bourgeoisie.

The machiavellianism of the bourgeoisie isn't the expression of an anachronism or a perversion of its ideals about ‘democracy'. It is in conformity with its being, its true nature. This isn't a ‘novelty' of history -- merely one of its more sinister banalities. Although all exploiting classes have expressed this at different levels, the bourgeoisie has taken it onto a qualitatively new stage. By shattering the ideological framework of feudal domination -- religion -- the bourgeoisie emancipated politics from religion, as well as law, science, and art. Now it could use all these things as conscious instruments of its rule. Here we can see both the tremendous advance made by the bourgeoisie, as well as its limits.

It's not the ICC which has a machiavellian view of the bourgeoisie, it's the bourgeoisie which, by definition, is machiavellian. It's not the ICC which has a conspiratorial, policeman's view of history, it's the bourgeoisie. This view is ceaselessly propounded in the pages of its history books, which spend their time exalting individuals, concentrating on plots, on rivalries between cliques and other superficial aspects without ever seeing the real moving forces, compared to which these epiphenomena are merely froth on a wave.

In the end, for revolutionaries to point out that the bourgeoisie is machiavellian is relatively secondary and banal. The most important thing is to draw out the implications of this for the proletariat.

The whole history of the bourgeoisie demonstrates its intelligence, its capacity for maneuvering -- particularly in the period of decadence which has seen two world wars and in which the bourgeoisie has shown that no lies, no acts of barbarism are too great for it[3].

To believe that the bourgeoisie today is no longer capable of the same maneuverability the same lack of scruple which it shows in its internal rivalries, faced as it is by its historic class enemy, would lead to a profound under-estimation of the enemy that the proletariat is going to have to deal with.

The historic examples of the Paris Commune and the Russian revolution have already shown that, in the face of the proletariat, the bourgeoisie can set aside its most powerful antagonisms -‑ those which lead it towards war -- and unite against the class which threatens to destroy it.

The working class, the first exploited revolutionary class in history, cannot rely on any economic strength to carry out its political revolution. Its real strength is its consciousness, and this the bourgeoisie has well understood. "Governing means putting your subjects in a state where they can't bother you or even think of bothering you", as Machiavelli put it. This is truer than ever today.

Because terror alone isn't enough, all the bourgeoisie's propaganda is used to keep the proletariat tied to the chains of exploitation, to mobilize it for interests which aren't its own, to hold back the development of a consciousness of the necessity and possibility of the communist revolution.

If the bourgeoisie spends so much money on maintaining a political apparatus for containing and mystifying the proletariat (parliament, parties, unions,) and keeps an absolute control over all the media (press, radio, TV) it's because propaganda -- the lie -- is an essential weapon of the bourgeoisie. And the bourgeoisie is quite capable of provoking events to feed this propaganda, if need be.

Not to see all this means joining the camp of the ideologues that Marx attacked when he wrote:

"Although in daily life every shopkeeper knows how to distinguish between what an individual claims to be and what he really is, our historiography hasn't yet attained this banal knowledge. It believes word for word what each epoch affirms and imagines about itself."

It actually means failing to see the bourgeoisie, being blind to all its maneuvers because you don't believe the bourgeoisie is capable of them.

Just to take two particularly illustrative examples:

- the international anti-terrorist campaigns to create a climate of insecurity in order to polarize the proletariat's attention and subject it to an ever-increasing police control. The bourgeoisie hasn't only used the desperate acts of the petty bourgeoisie to this end: it hasn't hesitated to foment and organize terrorist attacks in order to feed its propaganda campaigns.

- for a long time, the bourgeoisie has understood the essential role of the left for controlling the workers. One of the essential tasks of bourgeois propaganda is to uphold the idea that the Socialist Parties, the Communist Parties, the leftists and the unions really do defend the interests of the working class. It's this lie which weighs most heavily on the consciousness of the proletariat.

This is the machiavellianism of the bourgeoisie in the face of the proletariat. It's simply the bourgeoisie's way of being and acting: nothing new in that. To denounce the bourgeoisie means above all to denounce its maneuvers, its lies; this is one of the most essential tasks for revolutionaries.

The question of effectiveness of the bourgeoisie's maneuvers and propaganda towards the proletariat is another problem. In the secrecy of its inner cabinets, the bourgeoisie can prepare the most subtle plots and maneuvers, but their success depends on other factors, above all the consciousness of the proletariat. The best way to strengthen this consciousness is for the working class to break with any illusions it might have about its class enemy and its maneuvers.

The proletariat is faced with a class of gangsters without scruples which will stop at nothing of sustain its system of exploitation. This is something the proletariat has to understand.

JJ

Notes on the consciousness of the decadent bourgeoisie

1. The proletariat is the first revolutionary class in history with no economic power in the old society. Unlike all previous revolutionary classes, the proletariat is not an exploiting class. Its consciousness, its self- awareness is therefore crucially important to the success of its revolution, whereas for previous revolutionary classes class consciousness was secondary or even inconsequential compared to their build-up of economic power prior to the wielding of political power.

For the bourgeoisie, the last exploiting class in history, the tendency towards the development of a class consciousness was taken far further than for its predecessors since it required a theoretical and ideological victory to cement its triumph over the old social orders.

The consciousness of the bourgeoisie has been molded significantly by two key factors:

* by constantly revolutionizing the forces of production the capitalist system constantly extended itself and, by creating the world market, brought the world to an unprecedented state of interconnection;

* from the early days of the capitalist system the bourgeoisie has had to deal with the threat posed by the class destined to be its gravedigger -- the proletariat.

The first factor propelled the bourgeoisie and its theoreticians to develop a general world view while its socio-economic system was in its phase of ascendance, ie, while it was still based on a progressive mode of production. The second factor provided a constant reminder to the bourgeoisie that, whatever the conflict of interest among its members, as a class it had to unite in the defense of its social order against the struggle of the proletariat.

Whatever advance in consciousness was made by the bourgeoisie over that of previous ruling classes, its world view was irreparably crippled by the very fact that its exploitative position in society masks from it the historical transiency of its system.

2. The basic unit of social organization within capitalism was the nation-state.

And within the confines of the nation-state the bourgeoisie organized its political life in a manner consistent with its economic life. Classically, political life was organized through parties which confronted each other in a parliamentary forum.

These political parties, in the first instance, reflected the conflict of interests between different branches of capital within the nation-state. From the confrontation of the parties within this forum a means of government was created to control and steer the state apparatus which then orientated society towards the goals decided by the bourgeoisie. In this mode of functioning can be seen the capacity of the bourgeoisie to delegate political power to a minority of its number.

(It should be noted that this ‘classical' organization of bourgeois political life into a parliamentary framework was not a universal blueprint, but a tendency within capitalism's ascendant epoch. The actual forms varied in different countries depending on such factors as: the speed of capital's development; the working-out of conflicts with the old ruling order; the adaptability of the new bourgeoisie; the actual organization of the state apparatus; the pressures imposed by the struggle of the proletariat, etc,)

3. The transition of the capitalist system into its epoch of decadence was swift, as the accelerating development of capitalist production came hard against the ability of the world market to absorb it. In other words, the relations of production abruptly imposed their fetters on the forces of production. The consequences were seen very quickly in the world events of the second decade of this century: in 1914 when the bourgeoisie demonstrated what its epoch of imperialism meant; in 1917 when the proletariat showed that it could pose its historic solution for humanity.

The lesson of 1917 has not been lost by the bourgeoisie. On a world scale the ruling class has come to appreciate that its first priority in this epoch is to defend its social system against the onslaught of the proletariat. It therefore tends to unite in the face of this threat.

4. Decadence is the epoch of historic crisis of the capitalist system. In a permanent way the bourgeoisie has to face up to the main characteristics of the epoch; to the cycle of crisis, war and reconstruction, and to the threat to the social order posed by the proletariat. In response to these, three developments have taken place inside the organization of the capitalist system:

* state capitalism

* totalitarianism

* the constitution of imperialist blocs

5. The development of state capitalism is the mechanism by which the bourgeoisie has organized its economy within each national framework to meet an ever-deepening crisis in decadence.

Whether by fusion with individual capitals, or by a more straightforward expropriation, the state has developed an overwhelming authority compared to any one unit of capital. This provides a coherence in economic organization through the subordination of the interests of each element to those of the national unit. And in the conditions imposed in the epoch of imperialism the basis of the economy has become a permanent war economy, a solid base on which state capitalism develops.

But if state capitalism was a response in the first instance to crisis at the level of production, the process of statification did not stop there. More and more, institutions have been absorbed by a voracious state machine only to become its instruments, and where instruments were lacking they were created. Thus the apparatus of the state has reached into all aspects of social life. In this context, the integration of the trade unions into the state has been of the greatest necessity and significance. Not only do they exist in this period to keep the wheels of production running but, as the policemen for the proletariat, they become important agents for the militarization of society.

Differences and antagonisms among the bourgeoisie in any one national capital do not disappear in decadence, but undergo a considerable mutation because of the power of the state. In the main, the antagonisms inside the bourgeoisie on a national level are attenuated only to appear in a more intensified competition between nation states at the international level.

6. One of the consequences of state capitalism is that power in bourgeois society tends to shift from the hands of the legislature to the executive apparatus of the state. This has a profound effect on the political life of the bourgeoisie since it takes place within the framework of the state. Consequently, within decadence the dominant tendency in bourgeois political life is towards totalitarianism, as in economic life it is towards statification.

Political parties of the bourgeoisie no longer remain as emanations of different interest groups as they were in the 19th century. They become expressions of state capital towards specific sections of society.

In a sense, one can say that the political parties of the bourgeoisie in any one country are merely factions of a state totalitarian party. In some countries the existence of the one-party state is always clear to see -- as in Russia. However, the effective existence of the one-party state in the ‘democracies' is shown starkly only at certain times. For example:

* the power of Roosevelt and the Democratic Party in the US in the late 1930s and during the Second World War;

* the ‘suspension of democracy' in Britain during the Second World War and the creation of the War Cabinet.

7. In the context of state capitalism, the differences between the bourgeois parties are nothing compared to what they have in common. All start from an over-riding premise that the interests of the national capital as a whole are paramount. This premise enables different factions to work together in a very close way -- especially behind the closed doors of parliamentary committees and in the higher echelons of the state apparatus. Indeed, only a very small fraction of the bourgeoisie's debate takes place in the parliamentary arena. Members of bourgeois parliaments have in fact become state functionaries.

8. Nonetheless, the bourgeoisie in any nation-state always has disagreements. However, it is important to distinguish among them:

- Real differences of orientation. Different factions can see the national interest at a given moment lying in quite different directions as, for example, in the dispute between the Labor and Conservative Parties in the 1940s and 1950s over what was to be done with the British Empire. (It is also possible, as can be seen time and again in the third world for differences between parties, especially over the issue of which bloc to join, to lead to war. In such instances, pronounced schisms can develop in the state and even major breakdowns in its functioning).

- Differences which arise because of the pressures which are imposed on various factions of the bourgeoisie because of their functions in the bourgeois state. Consequently, there can be agreement about general orientations, yet disagreements over the manner of their implementation - as was seen, for example, in Britain over the efforts to strengthen the grip of the trade unions over the working class in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

- Differences which are false and diversionary charades for the mystification of the population. For example, the whole ‘debate' over the SALT 2 ratification in the US Congress in the summer of 1979 was an ideological operation which covered over the fact that the bourgeoisie had taken several important decisions concerning preparations for the Third World War and the strategy by which they wanted that war pursued.

Often, however, there are strands of several of these present in the bourgeoisie's disagreements, especially during elections.

9. As the antagonisms between nation-states have intensified through the epoch, so world capital has attempted to take the development of state capitalism onto the international level through the formation of imperialist blocs. If the organization of the blocs has permitted a certain attenuation of the antagonisms among the member states of each bloc this has only led to a heightening of the rivalry between the blocs -- the final cleavage of the world capitalist system where all its economic contradictions find a focus.

In the formation of the blocs, previous alliances among groups of (more or less) equal capitalist states have been replaced by two groupings in each of which the lesser capitals are subordinate to one dominant capital. And just as in the development of state capital the apparatus of the state reaches into all aspects of economic and social life, so the organization of the bloc reaches into every nation-state in its membership. Two examples of this are;

- the creation of means to regulate the entire world economy since the Second World War (the Bretton Woods agreement, the World Bank, the IMF, etc.) and a theory to go with it (Keynesianism);

- the creation of a unified military command structure in each bloc (NATO, Warsaw Pact) .

10. Marx said that it was really only in times of crisis that the bourgeoisie became intelligent. This is true but, like many of Marx's insights, has to be considered in the light of the change in historical period. The overall vision of the bourgeoisie has narrowed considerably with its transformation from a revolutionary to a reactionary class in society. Today the bourgeoisie no longer has the world view it had last century and in this sense is far less intelligent. But, at the level of organizing to survive, to defend itself -- here, the bourgeoisie has shown an immense capacity to develop techniques for economic and social control way beyond the dreams of the rulers of the nineteenth century. In this sense, the bourgeoisie has become ‘intelligent' confronted with the historic crisis of its socio-economic system.

Despite the points just made about the three significant developments in decadence, it is possible to reaffirm the basic constraints on the consciousness of the bourgeoisie -- its incapacity to have a united consciousness or to fully understand the nature of its system.

But if the development of state capitalism and bloc-wide organizations has not given them the impossible it has provided them with highly-developed mechanisms for acting in concert. The bourgeoisie's ability to organize the functioning of the whole world economy since the Second World War in a way in which extended the period of reconstruction for decades and phased-in the reappearance of open crisis so that 1929-type crashes did not recur is testimony to this. And these actions were all based on the development of a theory about the mechanisms and ‘shortcomings' (as the bourgeoisie might call them) of the mode of production. In other words, these actions were performed consciously.

The capacity of the bourgeoisie to act in concert on diplomatic/military levels also has been shown time and again -- not least in the actions of both blocs in the Middle East over the past three decades.

However, the bourgeoisie has a relatively free hand in its activity on the purely economic or military levels -- that is to say, it is only dealing with itself. The functioning of the state is more complex where it has to deal with social questions -- for these involve the movements of other classes, particularly the proletariat.