International Review no.114 - 3rd quarter 2003

- 3747 reads

15th Congress of the ICC, Today the Stakes Are High--Strengthen the Organization to Confront Them

- 4648 reads

Today the Stakes Are High—Strengthen the Organization to Confront Them

At the end of March, the ICC held its 15th Congress. The life of a revolutionary organisation is an integral part of the proletariat’s struggle. It is therefore their responsibility to set before their class, and notably before their sympathisers and the other groups of the proletarian camp, the results of the work at their Congresses, these being moments of the utmost importance in the organisation’s existence. This is the purpose of the article that follows.

The 15th Congress held a particular importance for our organisation, for two main reasons.

First, since the last Congress held in spring 2001, we have witnessed a major aggravation of the international situation, at the level of the economic crisis and above all at the level of imperialist tensions. More precisely, the Congress took place while war was raging in Iraq, and our organisation had the responsibility to make its analyses more precise in order to make the most appropriate intervention, given the situation and the stakes involved for the working class in this new plunge by capitalism into military barbarism..

Secondly, this Congress took place after the ICC had been through the most dangerous crisis in its history. Even if this crisis has been overcome, it is vital for our organisation to draw the maximum number of lessons from the difficulties it has been through, to understand their origins and the way to confront them.

All the work and discussions at the Congress were animated by an awareness of the importance of these two questions, which are part of the two main responsibilities of any congress: to analyse the historic situation and to examine the activities which the organisation has to carry out within it. This work was undertaken on the basis of reports previously discussed throughout the ICC, and led to resolutions being adopted that give a frame of reference for the continuation of our work internationally.

In the previous issue of the International Review, we published a resolution on the international situation adopted by the Congress. As any reader can see, we analyse the present historical period as the final phase in capitalism’s decadence, the phase of the decomposition of bourgeois society as it rots where it stands. As we have already said on many occasions, this decomposition is the result of the inability of either of society’s two antagonistic classes – the bourgeoisie and the proletariat – to impose their own response to the irrevocable decadence of the capitalist economy: world war for the former, and world communist revolution for the latter. As we shall see, these historic conditions determine the main characteristics of the life of the bourgeoisie today, but they also weigh heavily on the proletariat and on its revolutionary organisations.

It was therefore within this framework that the Congress examined not only the aggravation of imperialist tensions that we are witnessing today, but also the obstacles that the proletariat encounters on its path towards its decisive confrontation with capitalism as well as the difficulties that our own organisation has encountered.

The analysis of the international situation

For certain organisations of the proletarian camp, notably the International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party, the organisational difficulties encountered by the ICC recently, like those in 1981 and in the early ‘90s, derive from its inability to develop an appropriate analysis of the current historical period. In particular, our concept of decomposition is seen as an expression of our "idealism".

We think that the IBRP’s evaluation of the origins of our organisational difficulties reveals in fact an under-estimation of the organisation question and of the lessons drawn by the workers’ movement on this subject. However, it is true that theoretical and political clarity is an essential arm of any organisation that claims to be revolutionary. In particular, if it is not able to understand what is really at stake in the historic period in which it carries out its struggle, it risks being cast adrift by events, falling into disarray and in the end being swept away by history. It is also true that clarity is not something that can be decreed. It is the fruit of a will, of a combat to forge the weapons of theory. It demands that the new questions posed by the evolution of historical conditions be approached with a method, the marxist method.

This is a permanent task and responsibility for the organisations of the workers’ movement. The task has had more acute importance in certain periods, for example at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The development of imperialism heralded capitalism’s coming entry into its decadence. Engels, projecting marxist analysis into the future in the 1880s, was able to announce the historic perspective looming on the horizon: socialism or barbarism. At the 1900 Paris Congress of the Socialist International, Rosa Luxemburg foresaw capitalism’s entry into its decadence and envisaged the possibility that the new period might begin with war: "It is possible that the first great expression of the bankruptcy of capitalism which lies before us may be, not the crisis, but a war". In 1899 Franz Mehring, one of the spokesmen of the left of the Social-Democracy, measured the full weight of responsibility which was going to lie on the shoulders of the working class: “The epoch of imperialism is the epoch of the bankruptcy of capitalism. If the working class is not up to the task [of overthrowing it] then the whole of humanity is under threat”. But this determination to analyse and understand the period in order to forge the weapons for the coming struggle was not universal in the Social-Democracy. Without going into Bernstein’s revisionism, nor into the speechifying of the worshippers of the “tried and trusted tactic”, Kautsky – the theoretical reference for the whole Socialist International – defended orthodox marxist positions but refused to use them to analyse the new period that was opening. The renegade Kautsky (as Lenin was later to call him) was already present in the Kautsky who refused to look the new period in the face and to recognise the inevitability of the war between the great imperialist powers.

In the midst of the counter-revolution, during the 1930s and 1940s, the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left, and the French Communist Left, continued the effort to analyse, “without any ostracism” (as the Italian Fraction wrote in their review Bilan), both past experience and the new conditions. This attitude is part of the struggle which the marxist wing has always conducted in the workers’ movement in facing up to historical evolution. It is a million miles removed from the religious vision of “"invariance” dear to the Bordigists, which sees the programme not as the product of a constant theoretical struggle to analyse reality and draw out its lessons, but as a dogma revealed in 1848, of which “not a comma need be changed”. On the contrary, the task of updating and enriching the programme and our analyses is a vital responsibility in the struggle.

This was the concern which inspired the reports prepared for the Congress and the debates of the Congress itself. The Congress approached this challenge within the framework of the marxist vision of the decadence of capitalism and of its present phase of decomposition. The Congress recalled that this vision of decadence was not only that of the Third International, but is indeed at the very heart of the marxist vision. It was this framework and historical clarity that enabled the ICC to measure the gravity of the present situation, in which war is becoming an increasingly permanent factor.

More precisely the Congress had to examine the degree to which the ICC’s analytical framework has been capable of accounting for the current situation. Following this discussion, the Congress decided that there was no question of putting this framework into question. The evolution of the current situation is in fact a full confirmation of the analyses the ICC adopted at the end of 1989, at the time of the collapse of the eastern bloc. The present events, such as the growing antagonism between the USA and its former allies that has manifested itself so openly in the recent crisis, the multiplication of military conflicts and the direct involvement within them of the world’s leading power - which has made increasingly massive displays of its military power – all this was already foreseen in the theses which the ICC produced in 1989-90.[1] The ICC, at its Congress, reaffirmed that the present war in Iraq cannot be reduced, as certain sectors of the bourgeoisie would like us to believe (in order to minimise their real gravity), to a “war for oil”. In this war, the control of oil is primarily a strategic rather than an economic objective for the American bourgeoisie. It is a means of blackmailing and pressuring the USA’s principal rivals, the great powers of Europe and Japan, and thus of countering their efforts to play their own game on the global imperialist chessboard. In fact, behind the idea that the current wars have a certain “economic rationality” is a refusal to take into account the extreme gravity of the situation facing the capitalist system today. By underlining this gravity, the ICC has placed itself within the marxist approach, which doesn’t give revolutionaries the task of consoling the working class. On the contrary it calls on revolutionaries to assist the proletariat to grasp the dangers which threaten humanity, and thus to understand the scale of its own responsibility.

And in the ICC’s view, the necessity for revolutionaries to explain to the working class the profound seriousness of what’s at stake today is all the more important when you take into account the difficulties the class is experiencing in finding the path of massive and conscious struggles against capitalism. This was thus another essential point in the discussion on the international situation: what is the basis today for affirming the confidence that marxism has always had in the capacity of the working class to overthrow capitalism and liberate humanity from the calamities into which it is now leading it?

What confidence can we have in the working class’ ability to face up to its historic responsibilities?

The ICC has on numerous occasions argued that the decomposition of capitalist society exerts a negative weight on the consciousness of the proletariat.[2] Similarly, since the autumn of 1989, it has stressed that the collapse of the Stalinist regimes would provoke “new difficulties for the proletariat” (title of an article from International Review n°60). Since then the evolution of the class struggle has only confirmed this prediction.

Faced with this situation, the Congress reaffirmed that the working class still retains all the potential to assume its historic responsibilities. It is true that it is still experiencing a major retreat in its consciousness, following the bourgeois campaigns that equate marxism and communism with Stalinism, and that establish a direct link between Lenin and Stalin. Similarly, the present situation is characterised by a marked loss of confidence by the workers in their strength and in their ability to wage even defensive struggles against the attacks of their exploiters, a situation which can lead to a serious loss of class identity. And it should be noted that this tendency to lose confidence in the class is also expressed among revolutionary organisations, particularly in the form of sudden outbursts of euphoria in response to movements like the one in Argentina at the end of 2001 (which has been presented as a formidable proletarian uprising when it was actually stuck in inter-classism). But a long term, materialist, historical vision teaches us, in Marx’s words, that “it’s not a question of considering what this or that proletarian, or even the proletariat as a whole, takes to be true today, but of considering what the proletariat is and what it will be led to do historically, in conformity with its being” (The Holy Family). Such an approach shows us that, faced with the blows of the capitalist crisis, which will give rise to more and more ferocious attacks on the working class, the latter will be forced to react and to develop its struggle.

This struggle, in the beginning, will be a series of skirmishes, which will announce an effort to move towards increasingly massive struggles. It is in this process that the class will once again recognise itself as a distinct class with its own interests, and rediscover its identity; and this in turn will act as a stimulus to its struggle. The same goes for war, which will tend to become a permanent phenomenon, each time uncovering a little more the serious tensions between the major powers, and above all revealing the fact that capitalism is incapable of eradicating this scourge, that it is a growing menace for humanity. This will give rise to a profound reflection within the class. All these potentialities are contained in the present situation. It is vital for revolutionary organisations to be conscious of this and to develop an intervention which can bring this reflection to fruition. This intervention is particularly important with regard to the minority who are looking for political clarification internationally.

But if they are to be up to their responsibilities, revolutionary organisations have to be able to cope not only with direct attacks from the ruling class, but also to resist the penetration into their own ranks of the ideological poison that the ruling class disseminates throughout society. In particular, they have to be able to fight the most damaging effects of decomposition, which not only affects the consciousness of the proletariat in general but also of revolutionary militants themselves, undermining their conviction and their will to carry on with revolutionary work. This is precisely what the ICC has had to face up to in the recent period and this is why the key discussion at this Congress was the necessity for the organisation to defend itself from the attacks facilitated by the decomposition of bourgeois ideology.

The life and activities of the ICC

The Congress drew a positive balance-sheet of the activities of our organisation since the last Congress, in 2001. Over the past two years, the ICC has shown that it is capable of defending itself against the most dangerous effects of decomposition, in particular the nihilistic tendencies which have seized hold of a certain number of militants who formed the “Internal Fraction”. The ICC has been able to combat the attacks by these elements whose aim was clearly to destroy the organisation. Right from the start of its proceedings, the Congress, following on from the Extraordinary Conference of April 2002,[3] was once again totally unanimous in ratifying the whole struggle against this camarilla, and in denouncing its provocative behaviour. It was fully convinced about the anti-proletarian nature of this regroupment. And it was no less unanimous in pronouncing the exclusion of the elements of the “Fraction”, which has crowned its anti-ICC activity by publishing on its website information which can only play directly into the hands of the police – and by justifying these actions.[4] These elements, although they refused first of all to come to the Congress (as they were invited to do) and then to present their defence in front of a commission specially nominated by the latter, have found nothing better to do in their bulletin n°18 than to continue their campaigns of slander against the organisation. This has provided further proof that their concern is not at all to convince the militants of the organisation of the dangers posed it by what they describe as a "leadership" dominated by a “liquidationist faction”, but to discredit the ICC as much as possible, now that they have failed to destroy it.[5]

How could these elements have developed, within the organisation, an activity which threatened to destroy it?

In approaching this question, the Congress highlighted a certain number of weaknesses, linked to the revival of the circle spirit and facilitated by the negative weight of social decomposition. An aspect of this negative weight is doubt in, and loss of confidence in, the working class: a tendency to see only its immediate weaknesses. Far from facilitating the party spirit, this attitude can only allow friendship links or confidence in particular individuals to substitute themselves for confidence in our principles of functioning. The elements who were to form the “Internal Fraction” were a caricature of these deviations and this loss of confidence in the class. Their dynamic towards degeneration made use of these weaknesses, which weigh on all proletarian organisations today, and weigh all the more heavily in that the majority of these organisations have no awareness of them at all. These elements carried out their destructive activities with a level of violence never before seen in the ICC. The loss of confidence in the class, the weakening of their militant conviction, were accompanied by a loss of confidence in the organisation, in its principles, and by a total disdain for its statutes. This gangrene could have contaminated the whole organisation and sapped all confidence and solidarity in its ranks – and this undermined its very foundations.

Without any fear, the Congress examined the opportunist weaknesses which enabled the clan that called itself the “Internal Fraction” to become such a danger to the very life of the organisation. It was able to do so because the ICC will be strengthened by the combat that it has just waged.

Furthermore, it is because the ICC does struggle against any penetration of opportunism that it seems to have such a troubled life, that it has gone through so many crises. It is because it defended its statutes and the proletarian spirit that animates them without any concessions, that it was met with such anger by a minority which had fallen deep into opportunism on the organisation question. At this level, the ICC was carrying on the combat of the workers’ movement which was waged by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in particular, whose many detractors castigated their frequent organisational struggles and crises. In the same period, the German Social-Democratic Party was much less agitated but the opportunist calm which reigned within it (challenged only by “trouble-makers” on the left like Rosa Luxemburg) actually prefigure its treason in 1914. By contrast, the crises of the Bolshevik party helped it to develop the strength to lead the revolution in 1917.

But the discussion on activities did not limit itself to dealing with the direct defence of the organisation against the attacks it has been subjected to. It insisted strongly on the necessity to develop its theoretical capacities, while recognising that the combat against these attacks had already stimulated its efforts in this direction. The balance-sheet of the last two years shows that there has been a process of theoretical enrichment, on such questions as the historical dimension of solidarity and confidence in the proletariat; on the danger of opportunism which menaces organisations who are unable to analyse a change of period; on the danger of democratism. And this concern for the struggle on the theoretical terrain, as Marx, Luxemburg, Lenin, or the militants of the Italian left and many other revolutionaries have taught us, is an integral part of the struggle against opportunism, which remains a deadly danger to communist organisations.

Finally, the Congress made an initial balance sheet of our intervention in the working class regarding the war in Iraq. It noted that the ICC had mobilised itself very well on this occasion: before the start of military operations, our sections sold a lot of publications at a number of demonstrations (when necessary producing supplements to the regular press) and engaging in political discussions with many elements who had not known our organisation previously. As soon as the war broke out, the ICC published an international leaflet translated into 13 languages[6] which was distributed in 14 countries and more than 50 towns, particularly at factories and workplaces, and also posted on our Internet site.

Thus this Congress was a moment that expressed the strengthening of our organisation. The ICC affirms with conviction the combat it has been waging and which it will continue to wage – the combat for its own defence, for the construction of the basis of the future party, and for the development of its capacity to intervene in the historical movement of the class. It has no doubt that it is a link in the chain of organisations that connect the workers’ movement of the past to that of the future.

ICC, April 2003

1. See in particular “Theses on the economic and political crisis in the USSR and the countries of the East” (International Review 60), written two months before the fall of the Berlin Wall, and “Militarism and Decomposition”, dated 4 October 1990 and published in IR 64

2. See in particular “Decomposition, final phase of capitalist decadence”, points 13 and 14, IR 62

3. See our article on the ICC’s extraordinary conference in the International Review n°110.

4. See on this point “The police-like methods of the IFICC” in World Revolution n°262

5One of the “IFICC’s” most persistent slanders is that the ICC is led by a “liquidationist faction” which uses “Stalinist” methods against its minorities in order to enforce a reign of terror and to prevent any possibility of disagreement being expressed within the organisation. In particular, the “IFICC” has constantly asserted that there are numerous members of the ICC who in fact disapprove of the policy adopted against the activities of the members of this so-called “fraction”. The resolution that the Congress adopted with regard to their behaviour thus mandated a special commission to hear the defence of the elements concerned:

“The constitution and the functioning of this commission are to be as follows:

-

it is made up of 5 members of the ICC from 5 different sections, 3 from the European and 2 from the American continent;

-

the majority of its members do not belong to the central organs of the ICC;

-

it must examine with the greatest attention the explanations and arguments put forward by each of the elements concerned.

Moreover, the latter will have every to facility to present themselves before the commission either individually or together, or to be represented by one or more of them. Each will also be able to demand that up to three members of the commission designated by the Congress be replaced by ICC militants of their choice, although obviously the commission’s membership cannot have a variable geometry. It will be made up of 5 members, of whom at least two must have been chosen by the Congress, while up to three may be chosen by the elements concerned according to the wishes expressed by a majority amongst them.

The decision to make the exclusion effective can only be taken by a 4/5 majority of the commission”.

With these arrangements, the IFICC only had to find two militants in the whole ICC opposed to their exclusion for the decision to be rendered null and void. They have preferred to wax ironic about the appeal procedure that we proposed to them, and to blather on about our “iniquitous”, “Stalinist” methods. They knew perfectly well that they will find nobody in the ICC to take their defence, so great is the disgust and indignation that their behaviour has aroused in EVERY militant of the organisation.

6 The languages of our regular territorial publications, plus Portuguese, Russian, Hindi, Bengali, Farsi, and Korean

Development of proletarian consciousness and organisation:

Recent and ongoing:

- War in Iraq [2]

160 years on: Marx and the Jewish question

- 6156 reads

In the last issue of this Review we published an article on Polanski’s film The Pianist [3], whose subject was the uprising of the Warsaw ghetto in 1943 and the Nazi genocide against Europe’s Jews. Sixty years after the unspeakable horrors of this campaign of extermination, one might have expected to find that anti-Semitism was a thing of the past – the consequences of anti-Jewish racism being so clear that it would have been discredited once and for all. And yet this is not at all the case. In fact, all the old anti-Semitic ideologies are as noxious and as widespread as ever, even if their main focus has shifted from Europe to the “Muslim” world, and in particular, to the “Islamic radicalism” personified by Osama Bin Laden, who in all his pronouncements never fails to attack the “crusaders and Jews” as the enemies of Islam and as suitable targets for terrorist attack. A typical example of this “Islamic” version of anti-Semitism is provided by the “Radio Islam” website, which has as its motto “Race? Only One Human Race”. The site claims to be opposed to all forms of racism, but on closer inspection it becomes clear that its main concern is with “Jewish racism towards non-Jews”; in fact, this is an archive of classical anti-Semitic tracts, from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a Czarist forgery from the late 19th century which purports to be the minutes of a meeting of the world Jewish conspiracy and was one of the bibles of the Nazi party, to Hitler’s Mein Kampf and the more recent rantings of the Nation of Islam leader in the USA, Louis Farrakhan.

Such publishing ventures – and they are assuming massive proportions today – demonstrate that religion today has become one of the main vehicles for racism and xenophobia, for stirring up pogromist attitudes, for dividing the working class and the oppressed in general. And we are not talking merely about ideas, but about ideological justifications for real massacres, whether they involve Orthodox Serbs, Catholic Croats or Bosnian Muslims in ex-Yugoslavia, Protestants and Catholics in Ulster, Muslims and Christians in Africa and Indonesia, Hindus and Muslims in India, or Jews and Muslims in Israel/Palestine.

In two previous articles in this Review – “Resurgent Islam, a symptom of the decomposition of capitalist social relations [4]” (International Review n°109) and “Marxism’s fight against religion: economic slavery is the source of the religious mystification [5]” (International Review n°110), we showed that this phenomenon was a real expression of the advanced decomposition of capitalist society. In this article we want to focus on the Jews in particular. Not simply because Karl Marx’s famous essay On the Jewish Question [6] was published 160 years ago, in 1843, but also because Marx, whose entire life was dedicated to the cause of proletarian internationalism, is today being cited as a theoretician of anti-Semitism - usually disapprovingly, but not always. The Radio Islam site is again instructive here: on it, Marx’s essay appears on the very same web page as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, even if the site also publishes Der Sturmer type cartoons insulting Marx for being a Jew himself.

This accusation against Marx is not new. In 1960 Dagobert Runes published Marx’ essay under his own title A World Without Jews, which implied that Marx was an early exponent of the “final solution” to the Jewish problem. In a more recent history of the Jews, the right wing English intellectual Paul Johnson raised similar charges, and did not hesitate to find an anti-Semitic component in the very idea of wanting to abolish buying and selling as a basis for social life. At the very least, Marx is a “self-hating” Jew (today, as often as not, a sobriquet pinned by the Zionist establishment on anyone of Jewish descent who expresses critical attitudes towards the State of Israel).

Against all these grotesque distortions, our aim in this article is not only to defend Marx from those who are seeking to use him against his own principles, but also to show that Marx’s work provides the only starting point for understanding and overcoming the problem of anti-Semitism.

The historical context of Marx’s essay On the Jewish question

It is useless to present or quote from Marx’s article out of its historical context. On the Jewish question was written as part of the general struggle for political change in semi-feudal Germany. The debate about whether Jews should be granted the same civil rights as the rest of Germany’s inhabitants was one aspect of this struggle. As editor of the Rheinische Zeitung Marx had originally intended to write a response to the openly reactionary and anti-Semitic writings of one Hermes who wanted to keep the Jews in the ghetto and preserve the Christian basis of the state. But after the Left Hegelian Bruno Bauer entered into the fray with two essays ‘The Jewish Question” and “The capacity of present day Jews and Christians to become free”, Marx felt it was more important to polemicise with what he saw as the false radicalism of Bauer’s views.

We should also recall that in this phase of his life, Marx was in a political transition from radical democracy to communism. He was in exile in Paris and had come under the influence of French communist artisans (cf. “How the proletariat won Marx to communism” in International Review 69); in the latter part of 1843, in his Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, he identified the proletariat as the bearer of a new society In 1844 he met Engels, who helped him to see the importance of understanding the economic basis of social life; the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts written in the same year, are his first attempt to understand all these developments in their real depth. In 1845 he wrote the Theses on Feuerbach which express his definitive break with the one-sided materialism of the latter.

The polemic with Bauer on the question of civil rights and democracy, published in the Franco-German Yearbooks, was without question a moment in this transition.

At that time Bauer was a spokesman for the “left” in Germany, although the seeds of his later evolution towards the right can already be noted in his attitude to the Jewish question, where he adopts a seemingly radical position which actually ended up as an apology for doing nothing to change the status quo. According to Bauer, it was useless to call for the political emancipation of the Jews in a Christian state. It was necessary, first of all, for both Jews and Christians to give up their religious beliefs and identity in order to achieve real emancipation; in a truly democratic state, there would be no need for religious ideology. Indeed, if anything, the Jews had further to go than the Christians: in the view of the Left Hegelians, Christianity was the last religious envelope in which the struggle for human emancipation had expressed itself historically. Having rejected the universalist message of Christianity, the Jews had two steps to make while the Christians had only one.

The transition from this view to Bauer’s later overt anti-Semitism is not hard to see. Marx may well have sensed this, but his polemic begins by defending the position that the granting of “normal” civil rights for Jews, which he terms “political emancipation”, would be “a big step forward”; indeed it had already been a feature of earlier bourgeois revolutions (Cromwell had allowed the Jews to return to England and the Napoleonic code granted civil rights to Jews). It would be part of the more general struggle to do away with feudal barriers and create a modern democratic state, which was now long overdue in Germany in particular.

But Marx was already aware that the struggle for political democracy was not the final aim. On the Jewish question seems to express a significant advance over a text written shortly before, the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of the State, In this text Marx pushes his thought to the extreme of radical democracy, arguing that real democracy – universal suffrage – would mean the dissolution of the state and of civil society. By contrast, in On The Jewish Question, Marx affirms that a purely political emancipation – he even uses the term a “perfected democracy” - falls far short of real human emancipation.

It is this text in which Marx clearly recognises that civil society is bourgeois society – the society of isolated egos competing on the market. It is a society of estrangement or alienation (this was the first text in which Marx used these terms) in which the powers set in motion by man’s own hands – not only the power of money, but also the state power itself – inevitably become alien forces ruling man’s life. This problem is not solved by the achievement of political democracy and the rights of man. This is still based on the notion of the atomised citizen rather than on a real community. “None of the so-called rights of man goes beyond the egoistic man, the man withdrawn into himself, his private interest and his private choice, and separated from the community as a member of civil society. Far from viewing man here in his species-being, his species life itself – society – rather appears to be an external framework for the individual, limiting his original independence. The only bond between men is natural necessity, need and private interest, the maintenance of their property and egoistic interest”.

Further proof that alienation does not disappear as a result of political democracy was, Marx pointed out, provided by the example of North America, where religion was formally separated from the state and yet America was par excellence the country of religious observation and religious sects.

Thus: while Bauer argues that it is waste of time fighting for the political emancipation of the Jews as such, Marx defends and supports this demand: “We thus do not say with Bauer to the Jews: You cannot be politically emancipated without radically emancipating yourselves from Judaism. Rather we tell them: because you can be emancipated politically without completely and fully renouncing Judaism, political emancipation is by itself not human emancipation. If you Jews want to be politically emancipated without emancipating yourselves humanly, the incompleteness and contradiction lies not only in you but in the essence and category of political emancipation”. Concretely, for Marx this meant that he accepted the request of the local Jewish community to write a petition in favour of civil liberties for Jews. This approach towards political reforms was to be the characteristic attitude of the workers’ movement during the ascendant period of capitalism. But Marx is already looking further down the road of history - towards the future communist society –even if this is not yet named as such in On The Jewish Question. This is the conclusion to the first part of his reply to Bauer “Only when the actual individual man has taken back into himself the abstract citizen and in his everyday life, his individual work, and in his individual relationships has become a species being, only when he has recognised and organised his own powers as social powers so that social force is no longer separated from him as a political power, only then is human emancipation complete”.

Marx’s alleged anti-Semitism

It is the second part of the text, replying to Bauer’s second article, which has drawn most fire onto Marx from numerous quarters, and which the new wave of Islamic anti-Semitism is misusing in support of its obscurantist world view. “What is the worldly cult of the Jew? Bargaining. What is his worldly god? Money… Money is the jealous god of Israel before whom no other god may exist. Money degrades all the gods of mankind – and converts them into commodities. Money is the general, self-sufficient value of everything. Hence it has robbed the whole world, the human world as well as nature, of its proper worth. Money is the alienated essence of man’s labour and life, and this alien essence dominates him as he worships it. The god of the Jews has been secularised and has become the god of the world. The bill of exchange is the Jew’s actual god…”. This and other passages in On the Jewish questionhave been seized upon to prove that Marx is one of the founding fathers of modern anti-Semitism, whose essay has given respectability to the racist myth of the blood-sucking Jewish parasite.

It is true that many of the formulations Marx uses in this section could not be used in the same way today. It is also true that neither Marx nor Engels were entirely free from bourgeois prejudices and that some of their pronouncements about particular nationalities reflect this. But to conclude from this that Marx and marxism itself are indelibly stained with racism is a travesty of his thought.

All these phrases must be put in their proper historical context. As Hal Draper explains in an appendix to his book Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, Vol. I (Monthly Review Press, 1977), the identification between Judaism and “hucksterism”, or with capitalism, was part of the language of the time and was taken up by any number of radical thinkers and socialists, including Jewish radicals like Moses Hess who was an influence on Marx at the time (and indeed on the essay itself).

A historian of religion like Trevor Ling criticises Marx’s essay from another angle: “Marx had a mordant, journalistic style and decorated his pages with many a clever and satirical turn of phrase. The kind of writing of which examples have just been given is good vigorous pamphleteering, intended no doubt to stir the blood, but it has little to offer by way of useful sociological analysis. Such grand superficialities as ‘Judaism’ and ‘Christianity’, when used in this sort of context, have no correspondence with historical realities; they are labels attached to Marx’s own artificial, ill-perceived constructs” Ling, Karl Marx and Religion, Macmillan Press, 1980). But a few mordant phrases by Marx usually provide far sharper tools for examining a question in depth than all the learned treatises of the academics. In any case Marx is not trying here to write a history of the Jewish religion, which cannot be reduced to a mere justification for commercialism, not least because its ancient origins lie in a social order where money relations had a very subordinate role, and whose substance also reflects the existence of class divisions among the Jews themselves (for example, in the diatribes of the prophets against the corruptions of the ruling class in ancient Israel). As we have seen, having defended the need for the Jewish population to have the same “civil rights” as all other citizens, Marx merely uses the verbal analogy between Judaism and commodity relations to call for a society free of commodity relations, which is the real meaning of his concluding phrase, “The social emancipation of the Jew is the emancipation of society from Judaism”. This has nothing to do with any scheme for the physical elimination of the Jews, despite Dagobert Rune’s disgusting insinuations; it means that as long as society is dominated by commodity relations, human beings cannot control their own social powers and all will remain estranged from each other.

At the same time, Marx does provide the bases for a materialist analysis of the Jewish question - a work carried on by later Marxists, such as Kautsky and in particular Abram Leon.1 Marx points out, contrary to the idealist explanation which sought to explain the stubborn survival of the Jews as a result of their religious conviction, that the survival of their separate identity and of their religious convictions had to be explained on the basis of their real role in history: “Judaism has survived not in spite of but by means of history”. And this is indeed deeply connected to the Jews’ connection to commerce: “let us look for the secret of the Jew not in his religion but rather for the secret of the religion in the actual Jew”. And it is here that Marx uses the word play between Judaism as a religion and Judaism as a synonym for bargaining and financial power, which was based on a kernel of reality: the particular social-economic role played by the Jews within the old feudal system.

Leon, in his book The Jewish Question, a Marxist Interpretation, bases his entire study on these few limpid sentences in On The Jewish Question, and on another one in Capital which talks about “the Jews (living) in the pores of Polish society”(Vol. III, p 447) in a manner comparable to other “merchant-peoples” of history. From these few nuggets he developed the notion that the Jews, in ancient society and in feudalism, functioned as a “people-class” who were largely bound up with trade and money relations in societies which were predominantly founded on natural economy. In feudalism in particular this was codified in the religious laws, which forbade Christians to engage in usury. But Leon also shows that the Jewish connection to money relations was not always limited to usury. In both ancient and feudal society the Jews were very much a merchant people, personifying commodity relations which did not yet rule over the economy but simply linked dispersed communities where production was largely geared to use, and the bulk of the social surplus was appropriated and consumed directly by the ruling class. It was this peculiar social-economic function (which was of course a general tendency rather than an absolute law for all Jews) which provided the material basis for the survival of the Jewish “corporation” within feudal society; a contrario, where Jews engaged in other activities, such as farming, they tended to assimilate very quickly.

But this did not imply that the Jews were the first capitalists (a point which is not yet entirely clear in Marx’s text, because he has not yet fully grasped the nature of capital); on the contrary, it was the rise of capitalism that coincided with some of the worst phases of anti-Jewish persecution. Contrary to the Zionist myth that the persecution of the Jews has been a constant throughout history – and that they can never be free from it until they are gathered together in their own country2 - Leon shows that as long as they were playing a “useful” role in these pre-capitalist societies, the Jews were more usually tolerated, and often specifically protected by the monarchs who needed their financial skills and services. It was the emergence of a “native” merchant class, which began to use its profits to invest in production (for example, the English wool trade, key to the origins of an English bourgeoisie) which spelt disaster for the Jews, who now embodied an outmoded form of commodity economy and were seen as an obstacle to the development of its new forms. This tended to force more and more Jewish traders into the only form of commerce open to them – usury. But this practise brought the Jews into direct conflict with the principal debtors in society – the nobles on the one hand, and the small artisans and peasants on the other. It is significant, for example, that the worst pogroms against the Jews in western Europe took place in this period when feudalism had begun to decay and capitalism was on the rise. In England in 1189-90 the Jews of York and other English towns were slaughtered and the entire Jewish population expelled. Pogroms were often provoked by nobles who owed large amounts to the Jews and who found ready followers among the smaller producers who were also often in debt to Jewish money-lenders; both could hope to benefit from the cancellation of debt thanks to the murder or expulsion of the usurers, and the seizure of their property. The Jewish emigration from western Europe to Eastern Europe at the dawn of capitalist development was a move back to more traditionally feudal areas where the Jews could return to their own more traditional role; by contrast, those Jews who were left behind tended to become assimilated into the surrounding bourgeois society. In particular, a Jewish fraction of the capitalist class (typified by the Rothschild family) was the product of this period; parallel to this, came the development of a Jewish proletariat, although both eastern and western Jewish workers tended to be concentrated in the artisanal areas, away from heavy industry, and the majority of Jews continued to be disproportionately concentrated in the petty bourgeoisie, often in the form of petty tradesmen.

These layers - small tradesmen, artisans, proletarians - are thrown into the most abject misery by the decay of feudalism in the east, and the emergence of a capitalist infrastructure which already displays many features of its decline. In the late 19th century we now see new waves of anti-Semitic persecution in the Russian empire, provoking a new Jewish exodus to the west, which again “exports” the Jewish problem to the rest of the world, not least Germany and Austria. This period sees the development of the Zionist movement, which from right to left argues that the Jewish people could never be normalised until they had their own homeland – an argument whose futility was, for Leon, confirmed by the Holocaust itself, since none of this could have been prevented by the appearance of a small “Jewish homeland” in Palestine.3

Leon, writing in the midst of the Nazi holocaust, shows how the paroxysm of anti-Semitism reached in Nazi Europe is the expression of the decadence of capitalism. Fleeing the Czarist persecution in eastern Europe and Russia, the immigrant Jewish masses found in western Europe not a haven of peace and tranquillity, but a capitalist society that was soon to be wracked by insoluble contradictions, ravaged by world war and world economic crisis. The defeat of the proletarian revolution after the first world war opened the door not only to a second imperialist butchery, but also to a form of counter-revolution which exploited age-old anti-Semitic prejudices to the hilt, using anti-Jewish racism both practically and ideologically as a basis for completing the liquidation of the proletarian menace and for gearing society for a new war. Like the International Communist Party (ICP) in Auschwitz, the Grand Alibi, Leon focuses in particular on the use that Nazism made of the convulsion of the petty bourgeoisie, ruined by the capitalist crisis and easy meat for an ideology which promised them that they would be not only free of their Jewish competitors but also be officially permitted to lay their hands on their property (even if the Nazi state did not really allow the German petty bourgeoisie to benefit from this but appropriated the lion’s share to develop and maintain a vast war economy).

At the same time, as Leon points out, the use of anti-Semitism once again as a socialism of fools, a false criticism of capitalism, enabled the ruling class to drag in certain sectors of the working class, particularly its more marginal layers or those crushed by unemployment. Indeed, the notion of “national” socialism was one of the direct responses of the ruling class to the close link that had been established between the authentic revolutionary movement and a layer of Jewish workers and intellectuals who, as Lenin had pointed out, naturally gravitated towards international socialism as the only solution to their situation as a homeless and persecuted element of bourgeois society. International socialism was branded as a trick of the world Jewish conspiracy and proletarians were enjoined to combine their socialism with patriotism. It should also be pointed out that this ideology was mirrored in the Stalinist USSR, where the campaign of insinuation against “rootless cosmopolitans” was a cover for anti-Semitic slurs against the internationalist opposition to the ideology and practise of “socialism in one country”.

This emphasises that the persecution of the Jews also functions at an ideological level and requires a justifying ideology; in the Middle Ages, it was the Christian myth of Christ killers, well-poisoners, ritual murderers of Christian children: Shylock and his pound of flesh.4 In the decadence of capitalism, it is the myth of the Jewish world conspiracy that has conjured up both capitalism and communism to impose its rule over the Aryan peoples.

In the 1930s, Trotsky noted that the decline of capitalism was spawning a terrible regression on the ideological level:

“Fascism has opened up the depth of society for politics. Today, not only in peasant homes but also in city skyscrapers, there lives alongside of the twentieth century the tenth or the thirteenth. A hundred million people use electricity and still believe in the magic power of signs and exorcisms. The Pope of Rome broadcasts over the radio about the miraculous transformation of water into wine. Movie stars go to mediums. Aviators who pilot miraculous mechanisms created by man’s genius wear amulets on their sweaters. What inexhaustible reserves they possess of darkness, ignorance and savagery! Despair has raised them to their feet, fascism has given them a banner. Everything that should have been eliminated from the national organism in the form of cultural excrement in the course of the normal development of society has now come gushing up from the throat; capitalist society is puking up the undigested barbarism. Such is the psychology of National Socialism” (“What is National socialism”, 1933).

These elements all come together in the Nazis’ fantasies about the Jews. Nazism made no secret of its ideological regression – it openly harked back to the pre-Christian gods. Nazism, in fact, was an occultist movement that had seized direct control of the means of government; and like other occultisms, it saw itself doing battle with another hidden and satanic power – in this case, the Jews. And these mythologies, which can certainly be examined in their own right, in all their psychological aspects, take on a logic of their own and fuel the juggernaut that led to the death camps.

However, this ideological irrationality is never divorced from the material contradictions of the capitalist system – it is not, as numerous bourgeois thinkers have tried to argue, the expression of some metaphysical principle of evil, some unfathomable mystery. In the article on Polanski’s film The Pianist in IR 113 we cited the ICP on the cold calculating “rationale” behind the Holocaust – the industrialisation of murder, where the maximum of profit was squeezed from every corpse. But there is another dimension, which the ICP does not go into: the irrationality of capitalist war itself. Thus the “final solution”, in the image of the world war which provided its background, is provoked by economic contradictions and does not renounce the hunt for profit, but at the same time becomes an added factor in the exacerbation of economic ruin. And if use of forced labour was demanded by the war economy, the whole machinery of the concentration camps also became an immense burden on the German war effort.

The solution to the Jewish problem

160 years on, the essence of what Marx put forward as the solution to the Jewish problem remains valid: in the abolition of capitalist relations and the creation of real human community. Of course this also is the only possible solution to all surviving national problems: capitalism has proved incapable of resolving them. The current manifestation of the Jewish problem, which is specifically linked to the imperialist conflict in the Middle East, is the best proof of this.

The “solution” put forward by the “Jewish national liberation movement”, Zionism, has become the kernel of the problem. The greatest source of the current anti-Semitic revival is no longer linked directly to the particular economic function of the Jews in the advanced capitalist states, nor to a problem of Jewish immigration into these regions. Here, since world war two, the focus of racism has shifted to the waves of immigration from the former colonial regions; most recently, with the furore over “asylum seekers”, it is aimed first and foremost at the victims of economic, ecological and military devastation that decomposing capitalism is inflicting on the planet. “Modern” anti-Semitism is first and foremost connected to the conflict in the Middle East. Israel’s nakedly imperialist policies in the region and the support unwaveringly given to these policies by the USA has been a shot in the arm for all the old myths of a world Jewish conspiracy. Millions of Muslims are convinced by the urban myth that “40,000 Jews stayed away from the Twin Towers on September 11 because they had been warned in advance that the attack was coming” – that “the Jews did it”. And this notwithstanding that this claim is happily put forward by people who also defend Bin Laden and applaud the terrorist attack!5 The fact that several leading members of the clique around Bush, the “neo-conservatives” who are today the most vigorous and explicit advocates of the “new American century”, are Jews, (Wolfowitz, Perle, etc) has added grist to this mill, sometimes providing it with a left wing twist. In Britain recently there was a controversy around the fact that Tam Dalyell, an “anti-war” figure on the Labour left, spoke openly about the influence of the “Jewish lobby” on US foreign policy and even on Blair; and he was defended from charges of anti-Semitism by Paul Foot of the Socialist Workers Party who only regretted that he had talked of Jews and not Zionists. In actual practise, the distinction between the two has become increasingly blurred in the discourse of the nationalists and jihadists who lead the armed struggle against Israel. In the 60s and 70s the PLO and its leftist supporters claimed that they wanted to live in peace with the Jews in a democratic secular Palestine; but today the ideology of the intifada is overwhelmingly that of Islamic radicalism, which makes little secret of its wish to expel the Jews from the region or exterminate them outright. As for Trotskyism, it has long joined the ranks of the nationalist pogrom. We have already mentioned Abram Leon’s warning that Zionism could do nothing to save the Jews of war-torn Europe; today we can add that the Jews most threatened with physical destruction are located precisely in the promised land of Zionism. Zionism has not only built a huge prison-house for the Palestinian Arabs who live under its humiliating regime of military occupation and brutal violence; it has also imprisoned the Israeli Jews themselves in the gruesome spiral of terrorism and counter-terror which no imperialist “peace process” seems able to overcome.

Capitalism in its decadence has conjured up all the demons of hatred and destruction that have ever haunted humanity, and armed them with the most devastating weapons ever seen. It has given rise to genocide on a scale unprecedented in history, and shows no sign of abating; despite the Holocaust of the Jews, despite the cries of Never Again, we have seen not only a virulent revival of anti-Semitism but also ethnic massacres on a scale which bear comparison with the Holocaust, such as the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Tutsis in Rwanda in the space of a few weeks, or the continuous rounds of ethnic cleansing that ravaged the Balkans throughout the 90s. This revival of genocide is characteristic of decadent capitalism in its final phase – that of decomposition. These terrible events give us a glimpse of the future that the final playing out of decomposition holds in store: the self-destruction of humanity. And as with Nazism in the 30s, we see alongside these massacres the return of the most reactionary and apocalyptic ideologies all over the planet - Islamic fundamentalism, founded on racial hatred and the mysticism of suicide, is the most obvious expression of this, but not the only one: we can equally point to the Christian fundamentalism that has begun to influence the highest echelons of power in the most powerful nation of earth; to the growing grip of Jewish orthodoxy on the Israeli state, to Hindu fundamentalism in India which, like its Muslim mirror image in Pakistan, is armed with nuclear weapons; to the “fascist” revival in Europe. Neither should we leave the religion of democracy out of this list; just as it did during the period of the Holocaust, democracy today, the banner flown by US and British tanks in Afghanistan and Iraq, has shown itself to be the other side of the coin to the more overtly irrational faiths; a fig-leaf for totalitarian repression and imperialist war. All these ideologies are expressions of a social system which has reached an absolute dead-end and offers humanity nothing but destruction.

Capitalism in its decline has created a myriad of national antagonisms, which it has proved unable to resolve; it has merely used them to pursue its drive towards imperialist war. Zionism, which has only been able to establish its goals in Palestine by subordinating itself to the needs first of British, then of American imperialism, is a clear example of this rule. But contrary to the anti-Zionist ideology, it is by no means a special case. All nationalist movements have operated in exactly the same way, including Palestinian nationalism which has functioned as the agent of various imperialist powers large and small, from Nazi Germany to the USSR and Saddam’s Iraq, not forgetting some of the contemporary powers of Europe. Racism and national oppression are realities in capitalist society, but the answer to them does not lie in any schemes for national self-determination, or in the fragmentation of the oppressed into a host of “partial” movements (blacks, gays, women, Jews, Muslims, etc). All such movements have proven to be an added means for capitalism to divide the working class and prevent it from seeing its real identity. It is only by developing this identity, through its practical and theoretical struggles, that the working class can overcome all the divisions within its ranks and forge itself into a power capable of taking on the power of capital.

This does not mean that all national, religious and cultural issues will automatically disappear once the class struggle reaches a certain height. The working class will make the revolution long before it has cast off all the baggage of the ages, or rather in the very process of casting it off; and in the period of transition to communism it will have to confront a host of problems relating to religious belief and cultural or ethnic identity as it seeks to unify the whole of humanity into a global community. It is axiomatic that the victorious proletariat will never forcibly suppress particular cultural expressions any more than it will outlaw religion; the experience of the Russian revolution has demonstrated that such attempts only serve to reinforce the grip of outmoded ideologies. The mission of the proletarian revolution, as Trotsky forcefully argued, is to lay the material foundations for the synthesis of all that is best in the many different cultural traditions in man’s history – for the first truly human culture. And thus we return to the Marx of 1843: the solution to the Jewish question is real human emancipation, which will finally allow man to abandon religion by extirpating the social roots of religious alienation.

Amos

General and theoretical questions:

- Religion [7]

Class struggles in France, spring 2003: the massive attacks of capital demand a mass response from the working class

- 3235 reads

The Massive Attacks of Capital Demand a Mass Response From the Working Class

Faced with the head-on attack on pensions in France and Austria, all sectors of the working class have joined the struggle with a determination unknown since the end of the 1980s. In France, weeks of repeated demonstrations brought together hundreds of thousands of workers from both public and private sector: 1½ million workers were in streets of the main cities in France on the 13th May, almost one million took part in a single demonstration in Paris on the 25th May, and on the third of June 750,000 more people mobilised. Workers in the education sector were at the forefront of the social movement, especially because they were the hardest hit. Austria witnessed the most massive demonstrations since the end of World War II against similar attacks on pensions: more than 100,000 people on the 13th May, and almost one million on the third of June (this in a country of less than 10 million inhabitants). In Brasilia, the administrative capital of Brazil, 30,000 public sector employees demonstrated on the 11th June against a reform in taxation and Social Security, but also against a reform of pensions imposed by the new "left-wing government" of Lula. In Sweden, 9,000 municipal and public sector workers have gone on strike against cuts in social budgets.

The bourgeoisie makes the working-class pay for capitalism's crisis

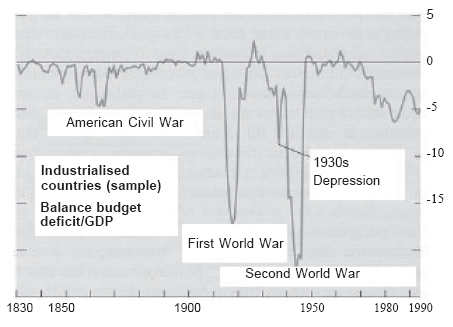

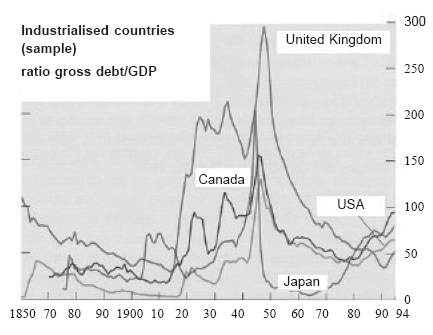

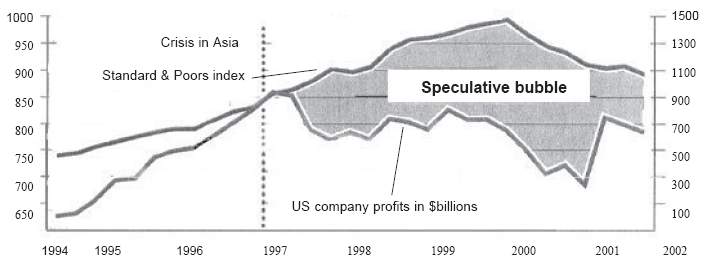

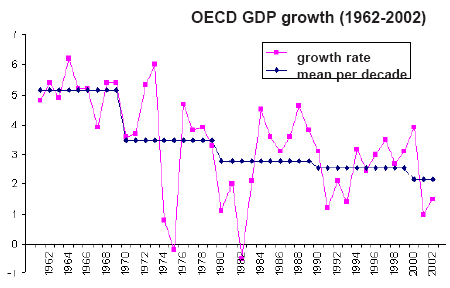

Up to now, the bourgeoisie has more or less succeeded in spreading out its anti working-class attacks over time, and in separating them by sector, by region, or by country. The major characteristic of the evolution of the present situation is that, since the end of the 1990s, these attacks have been undertaken more brutally, more violently, and more massively. This is an indication of the acceleration of the world crisis which is expressed in two major and concomitant phenomena on an international level: the return of the open recession, and the new surge in debt.

The countries at the heart of capitalism are now deeply affected by the new plunge into recession: this has been true for Japan for several years and is now the case in Germany. Officially, Germany has already entered a new period of recession (for the second time in two years). Other European states, in particular Holland, are in the same situation. The United States has been seriously threatened by recession for two years: unemployment, the trade deficit, and the federal budget deficit are all on the rise once again. The French newspaper Le Monde (16th May) sounds the alarm over the danger of deflation and the return of the spectre of the 1930s: “not only is the hope of a recovery following the war in Iraq fading by the day, its place is being taken by growing fear that the American economy is going to plunge into a spiral of falling prices (...) A scenario for disaster in which the price of services and consumer goods is in constant decline, profits collapse, companies reduce their workforce and announce redundancies, bringing in their wake the new decline in consumption and in prices. Households and companies are too indebted to meet their commitments, while exhausted banks are forced to restrict credit under the impotent gaze of the Federal Reserve. These are not merely the hypotheses of experts in search of strong sensations. This has been the situation in Japan for more than 10 years, punctuated by brief periods of remission”. What the bourgeoisie calls deflation is nothing other than a lasting plunge into recession, where the scenario described above becomes a reality, and where the bourgeoisie is no longer able to use credit to launch a recovery. This completely refutes the arguments of all those who thought that the war in Iraq would make possible the recovery of the world economy. In reality, the war and the drawn-out occupation which has followed it, are first and foremost a heavy burden for the American and British economies ($1 billion a week for the American occupying forces alone). Moreover, workers all over the world are paying for the accelerating arms race (amongst others, through various new European military programmes).

The second characteristic of the economic situation is a further increase in an already enormous level of debt, which represents a veritable time-bomb for the period to come, and which affects every level of the economy from households, to companies, to national governments, whose level of debt has never been so high (see the article on the crisis in this issue of the Review).

As always, capitalism is trying to overcome the crisis and its contradictions using the two only methods which it has at its disposal:

- on one hand, intensifying the productivity of labour by increasing the pressure on the workers who produce surplus value;

- on the other hand, directly attacking the cost of variable capital, in other words by reducing the rate of pay of the workforce. There are several methods for this: proliferating redundancy plans; reducing wages, most commonly via “delocalisation” and the use of immigrant workers to reduce the cost of labour as much as possible; and the reduction in the cost of the social wage by cutting all the social budgets (pensions, health, unemployment benefit).

Capitalism is forced to act more and more simultaneously on all these levels, in other words the state everywhere is pushed to attack at the same time every aspect of working-class living conditions. In the logic of bourgeois profit there is no other solution than to undertake these massive and head-on attacks. Obviously, the ruling class is careful to plan and to co-ordinate the rhythm of these attacks according to the country, in order to avoid simultaneous social conflicts on the same question.

Since the 1970s, with a generalisation of massive unemployment and the sacrifice of thousands of companies and of the less profitable sectors of the economy, millions of jobs had disappeared and the bourgeoisie has revealed its inability to integrate new generations of workers into the productive process. But today, we are at a new watershed: not only is the ruling class continuing to make large numbers of workers redundant, it now has the social wage in its sights. In some central countries, like United States, “social protection” has always been virtually non-existent. But in these cases, and in the USA in particular, pensions were generally financed by the employer. At the root of the “financial scandals” of recent years, of which the most spectacular example is that of Enron, is the fact that companies used their pension funds to invest on the stock exchange and this money has been lost in doubtful speculation, leaving the companies unable to pay out a decent pension or to compensate their despoiled workforce, who are now reduced to dire poverty. In countries like Great Britain, social protection has already been to a large extent dismantled. The British case is a particularly edifying example of what the working class can expect: since the “Thatcher years”, 20 years ago, pensions have been based on private pension funds. But the situation has become much worse since then. By transforming pensions into private funds, the idea was that shares in these funds would bring in a lot of money as the stock exchange rose. The opposite has happened. With a collapse in share prices, hundreds of thousands of workers are reduced to poverty (the basic state pension is only about €120 a week). Some 20% of pensioners live below the poverty line, condemning many of them to continue working beyond the age of 70, generally in poorly paid and precarious jobs. Many workers find themselves in the agonising situation of being unable to pay for their lodging or for their medical expenses. Elderly people dependent on expensive treatment can no longer rely on hospital care. British clinics and hospitals thus refuse dialysis to elderly patients who are unable to pay for it, directly condemning them to death. More generally, the seizure of houses or flats whose owners can no longer pay their mortgage has quadrupled in two years, while 5 million people are living below the poverty line (this figure has doubled since the 1970s) and unemployment is rising faster than at any time since 1992. The first capitalist country to have set up the welfare state after World War II, has become the first test bed for its dismantling.

The turning point in the violence of the attack

Today, these attacks are becoming general, “globalised”, shattering the myth of “social gains”. The nature of these new attacks is significant. They are targeting pensions, unemployment benefit, and healthcare. More and more clearly, they reveal everywhere the bourgeoisie’s growing inability to finance the social budget. The scourge of unemployment and the end of the Welfare State are two major expressions of the global bankruptcy of capitalism. This is illustrated by the recent attacks in several countries:

In France, the government intends to go further than merely aligning state sector pensions with the private sector by raising the number of years worked from 37.5 to 40 in order to gain access to a “full” pension. It has also announced that the number of years worked will be further increased to 42, and then increased beyond that depending on the level of employment. Contributions will be raised for all wage earners in order to refill the pension funds' coffers, not to mention the requirement to make contributions to new “top-up” pension funds. According to official propaganda, the reasons are purely demographic: the ageing of the population is supposedly responsible for the deficit in the pension funds and is destined to become an intolerable burden of the economy. Apparently there will not be enough young workers to pay the pensions for a growing number of old people. The reality is that young people enter working life increasingly late, not only because the technical progress of production requires longer training but also because they have an ever greater difficulty in finding a job (raising the school leaving age is moreover another means of hiding unemployment amongst young workers). In reality the main reason for the fall in contributions and the deficit in the pension funds is the inexorable rise in unemployment (which represents at least 10% of the working population) and in precarious employment. In reality, many employers have no interest in keeping older workers on the payroll, since they are usually better paid than young workers, while being less resilient and less “adaptable”. Behind all the talk on the need to work longer there lies in fact a huge drop in the level of pensions. As soon as they are put into place the planned measures will immediately reduce pensioners’ purchasing power by between 15 and 50%, including for the worst paid workers. Another “reform” is that of the social security system, to be announced this coming autumn, which has already begun with the withdrawal of 600 medicines from the approved list, with a further 650 to follow by ministerial decree in July.

In Austria, an attack comparable to that in France is aimed mainly at pensions. Whereas the length of working life was already set at 40 years, it is now to rise to a minimum of 42 years and 45 years for most workers, with a decrease in pensions of up to 40% for some categories. The conservative Chancellor Schlüssel has made the most of early elections in February to form a new homogeneous government of the right, following the “crisis” of September 2002 which put an end to the cumbersome coalition with Haider's populist party, leaving the bourgeoisie with its hands free to undertake these new attacks.

In Germany, the red-green government has begun an austerity programme baptised "agenda 2010" attacking several aspects of the social wage simultaneously. In the first place, there is a drastic reduction in unemployment benefits. The duration of benefits will be reduced to 18 months from 36 months for workers over 55 and to 12 months for the rest. After that, and redundant workers will have no other resource than “social pay” (which represents about €600 per month). This is the equivalent of halving retirement pensions for 1½ million unemployed workers, just as the number of unemployed in Germany is rising above 5 million. As for the health service, the plan is to reduce the level of health benefits (reduction in the repayment of medicines and doctor’s visits, restriction in the number of sick days). For example benefits will be stopped after the sixth week of sickness per year, and people will be obliged to top up with private insurance. These restrictions in healthcare go together with an increase in contributions for all wage earners since the beginning of 2003. At the same time pensions are also under attack in Germany: the retirement age, which is already 65 years on average, will be raised as will wage earners' contributions, while the automatic annual revaluation of pensions is to be suppressed. Since the beginning of the year taxes have been raised (paid at source on wages), measures adopted to encourage temporary work, while the precarity of work continues to increase with the number of part-time or limited duration contracts.

In Holland, the new coalition government (Christian-Democrats, liberals, reformists) has followed Austria in getting rid of its populist wing and announced an austerity plan based on budget restrictions in the social domain (with a view to saving €15 billion), notably for a radical reform of unemployment benefit and the criteria for disability pensions as well as the general revision of wages policy.

In Poland, healthcare is also under attack. While the most serious illnesses continue to be taken in charge, most healthcare will only be reimbursed at 60 or at 30 percent. “Benign” sicknesses like flu or tonsillitis will not be reimbursed at all. State employees are no longer protected from redundancy.

As we have already seen above, in Brazil Lula's Workers' Party is at the forefront of the cuts in social budgets Latin America.

Within the framework of the enlargement of the European Union the International Labour Office directive of 9th June stipulates that for 5 out of the ten countries concerned (Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Estonia), pension funds should be financed solely by wage earners' contributions, whereas previously they were financed jointly by the employer, the state, and the wage earner.

We can thus see that whatever the government, whether it be right or left, the same attacks are under way.

They are accompanied by a wave of massive redundancies: 30,000 job cuts at Deutsche Telekom, 13,000 at France Telecom, 40,000 in the Deutsche Bahn (German railways), 2,000 job cuts at the SNCF (French Railways). Fiat has just announced 10,000 job cuts on the European continent after laying-off 8,100 workers at the end of 2002 in Italy itself. Alstom has announced 5,000 job cuts. Swissair plans to eliminate a further 3,000 jobs in a sector which has been particularly hard hit by the crisis during the last two years. The American merchant bank Merrill Lynch has laid off 8,000 employees since last year. In Britain, 42,000 jobs have been lost during the first quarter of 2003. Not a country, not a sector is spared. It is forecast for example that between now and 2006, 400 companies per week will close in Britain. Everywhere job insecurity is becoming the rule.

The mobilisation of the working class in the recent struggles was thus a response to this qualitative aggravation of the crisis and the attacks against its living conditions which are the result.

The balance of class forces

The first thing to be said about the struggles is that they are a stinging refutation of all those ideological campaigns that followed the collapse of the Eastern bloc and the Stalinist regimes. No, the working class has not disappeared! No, its struggles do not belong to the distant past! These struggles show that the perspective is still towards class confrontations, despite the confusion and the enormous ebbing of class-consciousness provoked by the upheavals of the period since 1989. An ebb which has been still further deepened by the ravages of advanced social decomposition, that has tended to deprive the workers of their reference points and their class identity, as well as by the bourgeoisie's antifascist and pacifist campaigns, and “citizens’ mobilisations”. Confronted with this situation the attacks of the bourgeoisie and the state are pushing the workers once again to assert themselves on a class terrain and eventually to rediscover their past experience and vital needs of the struggle. The workers are thus called to renew their experience of the sabotage of the struggle by the trade unions and the leftists - the organs which the bourgeoisie uses to control the class. Still more importantly, despite the bitterness of their defeat in the immediate, deeper questions are beginning to emerge within the working class about the way society functions, and these in turn tend to call into question all the illusions sown by the bourgeoisie.