International Review no.135 - 4th quarter 2008

- 3114 reads

There is only one alternative: workers' struggle to overthrow capitalism

- 3042 reads

This summer has witnessed yet another outburst of military barbarism. Just as the principal countries were counting their medals at the Olympic Games, terrorist attacks hit the Middle East, Afghanistan, Algeria, Lebanon, Turkey and India. In less than two months, 16 such attacks followed each other in a macabre dance that left scores of dead among the urban populations. In Iraq and Afghanistan, there is full-scale war.

But this militarist barbarism was at its height in Georgia.

Once again, the Caucasus was aflame. At the very moment that Bush and Putin were taking part in the opening of the Olympics, so-called symbol of peace and reconciliation between nations, the Georgian president Saakashvili, the protégé of the White House, and the Russian bourgeoisie, sent their troops off to slaughter the civilian population.

This war between Russia and Georgia resulted in a veritable ethnic cleansing on each side, with several thousands deaths, mostly civilians.

As ever, it was the local populations (whether Russian, Ossetian, Abkhazian or Georgian) who were taken hostage by all the national factions of the ruling class.

On both sides, the same scenes of killing and horror. Throughout Georgia, the number of refugees, stripped of everything they owned, reached 115,000 in one week.

And as in all wars, each camp accused the other of being responsible for the outbreak of hostilities.

But it is not just the direct protagonists who are responsible for this new war and these new massacres. The other states who are now shedding hypocritical tears about the fate of Georgia have their hands soaked with blood from the worst kinds of atrocities, whether we're talking about the US in Iraq, France in the Rwandan genocide in 1994, or Germany, which, by backing the secession of Slovenia and Croatia, helped unleash the terrible war in ex-Yugoslavia in 1992.

If today the US is sending warships to the Caucasus region, in the name of ‘humanitarian aid', this is certainly not out of any concern for human life, but simply to defend its imperialist interests.

Are we heading towards a third world war?

The most striking thing about the conflict in the Caucasus is the increasing military tension between the great powers. The two former bloc leaders, Russia and the US, once again find themselves in a dangerous head-to-head: the US Navy destroyers who have come with ‘food aid' for Georgia are only a short distance away from the Russian naval base of Gudauta in Abkhazia and the Georgian port of Poti which is occupied by Russian tanks.

This is all very nerve-wracking and one might legitimately ask not just what is the aim of this war But even whether it could unleash a third world war?

Since the collapse of the Eastern bloc, the Caucasus region has been an important geostrategic bone of contention between the great powers. The present conflict has been building up for some time. The Georgian president, an unconditional partisan of Washington, took over a state which from its creation in 1991 had been supported by the US as a bridgehead for Bush Senior's ‘New World Order'.

By laying a trap for Saakashvili, into which he duly fell, Putin has used the occasion to re-establish his authority in the Caucasus; but this was in response to the encirclement of Russia by NATO forces which has been under way since 1991.

Since the collapse of the Eastern bloc in 1989, Russia has been more and more isolated, especially since a number of former Eastern bloc countries (like Poland) joined NATO.

But the encirclement became intolerable for Moscow when Ukraine and Georgia also asked to join NATO.

Above all, Russia could not accept the plan to set up an anti-missile shield in Poland and the Czech Republic. Moscow knew perfectly well that behind this NATO programme, supposedly directed against Iran, Russia itself was the real target.

The Russian offensive against Georgia is in fact Moscow's first stab at breaking the encirclement.

Russia, having just re-established its authority in the Caucasus thanks to the costly and murderous war in Chechnya, has taken advantage of the fact that the US, with its troops bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, had its hands too full to launch a military counter-offensive.

However, despite the worsening military tension between Russia and the USA, the perspective of a third world war is not on the agenda today.

There are today no imperialist blocs, no stable military alliances as was the case before the two world wars of the 20th century or during the Cold War.

By the same token, the face-off between the US and Russia does not mean that we are entering a new Cold War. There's no going back and history does not repeat itself.

In contrast to the dynamic of imperialist tensions between the great powers during the Cold War, this new head-to-head between Russia and the US is marked by the tendency towards ‘every man for himself', towards the dislocation of alliances, characteristic of the phase of the decomposition of the capitalist system.

Thus the ‘ceasefire' in Georgia can only legitimate the victory of the masters of the Kremlin and Russia's superiority on the military level, involving a humiliating capitulation by Georgia to the conditions dictated by Moscow.

And Georgia's ‘patron', the US, has also suffered a major reverse here. While Georgia has already paid a heavy price for its allegiance to the US (a contingent of 2000 troops sent to Iraq and Afghanistan), in return Uncle Sam has been able to offer no more than moral support to its ally, issuing vain and purely verbal condemnations of Russia without being able to raise a finger to offer practical help.

But the most significant aspect of this weakening of US leadership resides in the fact that the White House had to swallow the ‘European' plan for a ceasefire - worse still, a plan dictated by Moscow.

While the USA's impotence was evident, Europe's role shows the level that ‘every man for himself' has reached. Faced with the paralysis of the US, European diplomacy swung into action, led by the French president Sarkozy who once again represented no one but himself in all his comings and goings, following a policy that was entirely short-term and devoid of any coherence.

Europe once again looked like a snake pit with everyone in it pursuing diametrically opposed interests. There was not an ounce of unity in its ranks: on one side were Poland and the Baltic states, fervent defenders of Georgia (because they suffered over half a century of Russian domination and have much to fear from a revival of the latter's imperialist ambitions) and on the other was Germany, which was one of the most fervent opponents of Georgia and Ukraine joining NATO, above all because it wants to block the development of American influence in this region.

But the most fundamental reason that the great powers cannot unleash a third world war lies in the balance of forces between the two main social classes: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Unlike the periods which preceded the two world wars, the working class of the most decisive capitalist countries, notably in Europe and America, is not ready to serve as cannon fodder and sacrifice itself on the altar of capital.

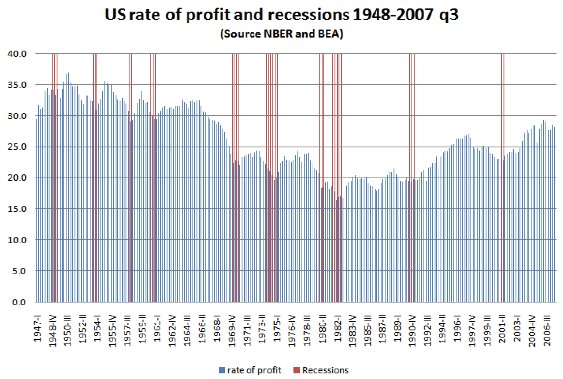

With the return of the permanent crisis of capitalism at the end of the 1960s and the historic resurgence of the proletariat, a new course towards class confrontations was opened up: in the most important capitalist countries the ruling class can no longer mobilise millions of workers behind the defence of the nation.

However, although the conditions for a third world war have not come together, this is no reason to underestimate the gravity of the present situation.

The war in Georgia has increased the risk of destabilisation, of things running out of control, not only on the regional level, but also on the world level, where it will have inevitable implications for the balance of imperialist forces in the future. The ‘peace plan' is just a bluff. It contains all the ingredients of a new and dangerous military escalation, threatening to create a series of flash-points from the Caucasus to the Middle East.

With the oil and gas of the Caspian Sea and the central Asian countries, some of which are Turkish-speaking, Iran and Turkey have interests in this region, but the whole world is involved in the conflict. Thus, one of the objectives of the USA and some Western European countries in supporting a Georgia independent from Moscow is to deprive Russia of the monopoly of Caspian Sea oil supplies towards the west thanks to the Baku-Tbilissi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline that runs from Azerbaijan, through Georgia to Turkey. There are thus major strategic interests at stake in this region. And the big imperialist brigands can all the more easily use people as cannon fodder in the Caucasus given that the region is a mosaic of different ethnicities. This makes it easy to fan the fire of nationalist war.

At the same time, Russia's past as a dominant power still exerts a very heavy weight and contains the threat of even more serious imperialist tensions. This is what lies behind the anxiety of the Baltic states, and above all of Ukraine which is a nuclear-armed military power of quite another stature to Georgia.

Thus although the perspective is not of a third world war, the dynamic of ‘every man for himself' is just as much the expression of the murderous folly of capitalism: this moribund system could, in its decomposition, lead to the destruction of humanity by plunging it into bloody chaos.

Faced with the bankruptcy of capitalism, what is the alternative?

In the face of all this chaos and military barbarism, the historical alternative is more than ever ‘socialism or barbarism', world communist revolution or the destruction of humanity. Peace is impossible in capitalism; capitalism carries war within itself. And the only future for humanity lies in the proletarian struggle for the overthrow of capitalism.

But this perspective can only become a reality if the workers refuse to serve as cannon-fodder for the interests of their exploiters, and firmly reject nationalism.

Everywhere the working class must put into practice the old slogan of the workers' movement: ‘The workers have no country. Workers of all countries unite!'

It is obvious that the proletariat cannot remain indifferent to the massacre of civilians and the unleashing of military barbarism,.It must show its solidarity with its class brothers in the countries at war, first of all by refusing to support one camp against the other, and secondly by developing its own struggles against its own exploiters in all countries. This is the only way it can really fight against capitalism, prepare the ground for its overthrow and for the construction of a new society without national frontiers and wars.

This perspective of the overthrow of capitalism is no utopia because everywhere capitalism is proving itself to be a bankrupt system.

When the Eastern bloc collapsed, Bush Senior and the whole of the ‘democratic' Western ruling class promised us a ‘New World Order' (to be set up under the aegis of the USA), a new era of peace and prosperity.

The entire world bourgeoisie engaged in gigantic campaigns about the so-called ‘failure of communism', trying to make the workers believe that the only possible future was Western-style capitalism with its ‘market economy'.

Today it is becoming more and more evident that it is capitalism that is failing, notably the world's leading power which has now become the locomotive dragging the whole capitalist economy towards the abyss (see our editorial in International Review n°133).

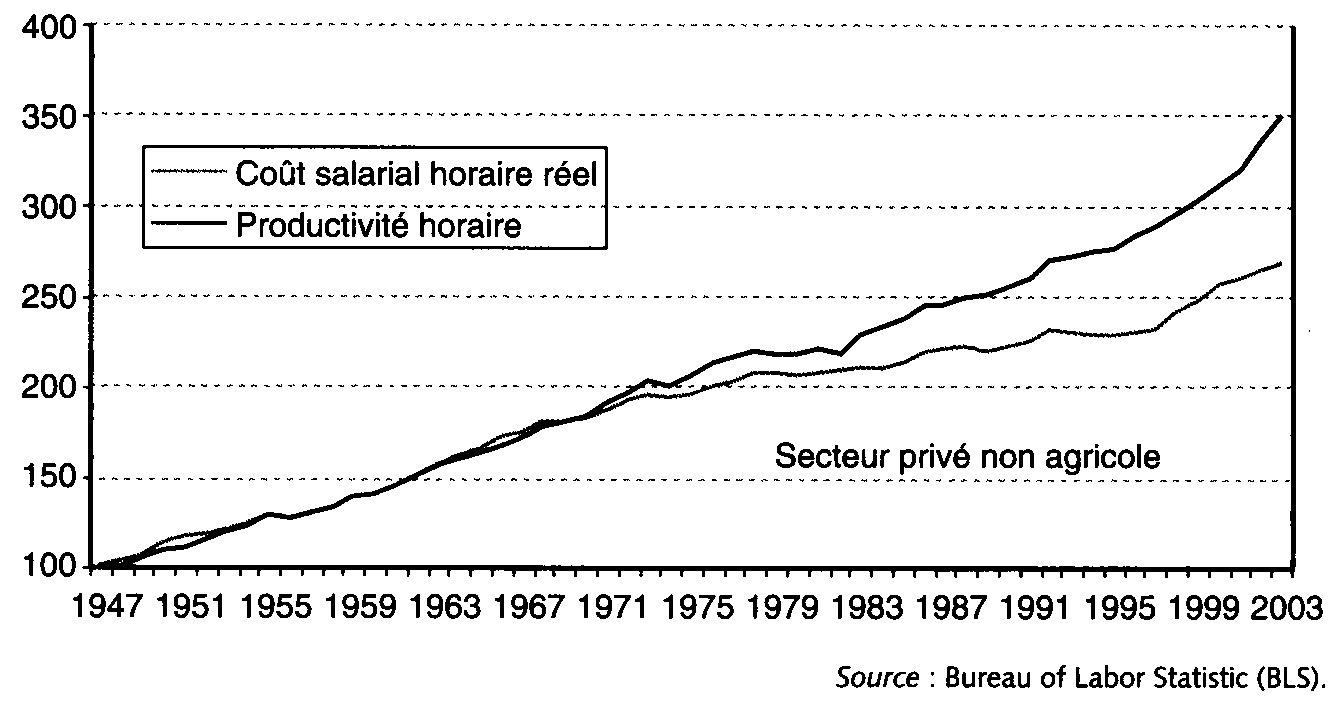

This failure is visible day after day in the increasing degradation of working class living standards, not only in the ‘poor' countries but also in the ‘rich' ones.

Just to take the USA as an example, unemployment there is rising rapidly and today 6% of the population is without work. Since the beginning of the ‘subprime' crisis, two million workers have been evicted from their houses because they can no longer keep up with their mortgage payments (and between today and the beginning of 2009, another million are facing the same threat).

And this is not even to mention the poor countries: with the increase in the price of basic foodstuffs, the most deprived strata are faced with the horror of famine. This is why hunger riots have broken out world wide this year - in Mexico, Bangladesh, Haiti, Egypt, the Philippines....

Today, with the facts staring them in the face, the spokesmen of the bourgeoisie can no longer conceal the truth. The shops are full of new books with alarmist titles. And above all, the declarations of the people in charge of the main economic institutions can no longer hide their anxiety:

"We are faced with one of the most difficult economic and fiscal environments we have ever seen" (the President of the US Federal Reserve, 22nd August).

"For the economy, the crisis is a tsunami on the horizon" (Jacques Attali, French economist and politician, Le Monde, 8th August).

"The present conjuncture is the most difficult for several decades" (according to HSBC, one of the world's biggest banks, cited in Libération 5th August).

The perspective for the development of the class struggle

In reality, the collapse of the Stalinist regimes did not show the failure of communism, but its necessity.The collapse of state capitalism in the USSR was in fact the most spectacular demonstration of the historic failure of world capitalism. It was a first great shockwave expressing the whole system's bankruptcy. Today a second shockwave is hitting the world's most powerful ‘democratic' power, the United States.

With the aggravation of the economic crisis and of military conflicts, we are witnessing an acceleration of history.

But this acceleration is also being expressed at the level of the workers' struggle, even if this does not appear in such a spectacular way.

If you took a still photograph of the situation, you might think that nothing was happening and that the workers were not moving. The workers' struggles don't seem to be adequate to the task at hand and the future looks grim.

But this is only the visible part of the iceberg.

In reality, as we have emphasised many times in our press, the struggles of the world proletariat have taken on a new dynamic since 2003[1].

The struggles that have been developing in the four corners of the world have been marked in particular by the search for active solidarity and the entry of the younger generation into the proletarian combat (as we saw in particular with the struggle of the French students against the CPE in the spring of 2006).

This dynamic shows that the working class has rediscovered the path of struggle, a path that was momentarily erased by the huge campaigns about the ‘death of communism' following the collapse of the Stalinist regimes.

Today the aggravation of the crisis and the deterioration of working class living standards can only push the workers to develop their struggles, to seek for solidarity, to unify across the world.

In particular, the spectre of inflation which is once again haunting capitalism, with the dizzying increase in prices accompanied by a fall in incomes (wages, pensions, etc) can only contribute to the unification of workers' struggles.

But two questions in particular will play a part in the proletariat becoming conscious of the bankruptcy of the system and the necessity for communism.

The first question is hunger and the generalisation of food shortages, which reveals beyond the shadow of a doubt that capitalism can no longer feed humanity and that we therefore have to move on to a new mode of production.

The second fundamental question is the absurdity of war, the murderous folly of capitalism which is destroying more and more human lives in endless slaughter.

It is true that, in an immediate sense, war creates fear and the bourgeoisie does all it can to paralyse the working class, to inject into it a feeling of powerlessness and to make it believe that war is just a fatality you can do nothing about. But at the same time the involvement of the great powers in military conflicts (especially in Iraq and Afghanistan) is provoking more and more discontent.

With American forces bogged down in Iraq, there is a growing anti-war feeling in the US population. We have seen this expressed in ‘public opinion' surveys, and it was the same in France after the French bourgeoisie paid homage to the 10 French troops killed in an ambush in Afghanistan on 18th August.

But alongside the discontent within the population at large, there is a deep process of reflection going on within the working class.

The clearest sign of this is the emergence of a new proletarian political milieu which has developed around the defence of internationalist positions against war (notably in Korea, the Philippines, Turkey, Russia and Latin America).[2]

War is not a fatality that leaves humanity powerless. Capitalism is not an eternal system. War is not all that capitalism bears within itself. It also bears the conditions for going beyond it, the germs of a new society without national frontiers and thus without wars.

By creating a world working class, capitalism has given birth to its own gravedigger. Because the exploited class, unlike the bourgeoisie, has no antagonistic interests to defend, it is the only force in society which can unify humanity by building a world based on solidarity and the satisfaction of human need.

There is still a long way to go before the world proletariat will be able to raise its struggles to the level demanded by the gravity of the present situation. But in the context of the acceleration of the world economic crisis, the dynamic of the class struggle today, as well as the entry of new generations into the movement, show that the proletariat is on the right road.

Today internationalist revolutionaries are still a small minority. But they have the duty to carry on a debate to overcome their differences and make their voices heard as clearly as possible wherever they can. It is precisely by being able to carry out a clear intervention against the barbarity of war that they will be able to regroup their forces and contribute to the proletariat becoming aware of the necessity to wage an offensive against the fortress of capital.

SW (12.9.08)

[1] See in particular the following articles ‘Against the world wide attacks of crisis-ridden capitalism: one working class, one class struggle' (International Review n°132) and ‘17th Congress of the ICC: resolution on the international situation' (International Review n°130)

[2] As well as the resolution on the international situation from the 17th ICC Congress, the reader can also consult, also in International Review n°130, ‘17th Congress of the ICC: the proletarian camp reinforced worldwide'

Geographical:

- Georgia [1]

People:

- Saakashvili [2]

- Putin [3]

Recent and ongoing:

- War in Georgia [4]

- South Ossetia [5]

Decadence of capitalism (iii): Ascent and decline in previous modes of production

- 5139 reads

"In broad outline, the Asiatic, ancient, feudal and modern bourgeois modes of production may be designated as epochs marking progress in the economic development of society".[1]

This brief passage, spanning virtually the whole of written history, could give rise to several books worth of interpretation. For our purposes, we will look at two aspects: the general question of historical progress, and the features of ascendancy and decadence in social formations prior to capitalism.

Is there any progress?

We have noted that one of the effects of the catastrophes of the 20th century has been a general scepticism about the idea of progress, a notion which had seemed much more self-evident in the 19th century. This has led some ‘radical' souls to conclude that the marxist vision of historical progress is itself just one of these 19th century ideologies which serve as an apology for capitalist exploitation. Although often presenting themselves as new, such criticisms often dredge up the rather worn arguments of Bakunin and the anarchists, who demanded that revolution be possible at any time, and accused the marxists of being vulgar reformists for arguing that the epoch of revolution had not yet dawned, requiring the working class to organise itself in the long term for the defence of its living conditions inside the existing social order. The anti-progressivists sometimes begin as ‘marxist' critics of the notion that capitalism is decadent today, insisting that very little has changed in the life of capital since the days Marx was writing about it, except perhaps on a purely quantitative level - bigger economy, bigger crises, bigger wars. But the more consistent ones quickly get rid of the whole burden of historical materialism altogether, insisting that communism could have come about in any previous epoch of history. Indeed the most consistent of all are the primitivists who argue that there has been no progress in history at all since the emergence of civilisation, and indeed since the discovery of agriculture which made it possible: all this is seen as a terrible wrong turn given that the happiest epoch of human life was the nomadic hunter-gatherer stage. Such currents can only logically anticipate with yearning the final collapse of civilisation and the culling of humanity so that a return to hunting and gathering could once again be practicable for the few survivors.

Marx was certainly ‘rigid' about the idea that it was capitalism alone which had paved the way for the overcoming of social antagonisms and the creation of a society which allowed humanity to develop to the full. As he goes on to say in the Preface: "The bourgeois mode of production is the last antagonistic form of the social process of production - antagonistic not in the sense of individual antagonism but of an antagonism that emanates from the individuals' social conditions of existence - but the productive forces developing within bourgeois society create also the material conditions for a solution of this antagonism".

Capitalism was for the first time creating the preconditions for a world communist society: by unifying the entire globe around its system of production; by revolutionising the instruments of production to the point where a society of abundance was finally possible; and by giving birth to a class whose own emancipation could only come through the emancipation of the whole of humanity - the proletariat, the first exploited class in history to contain the seeds of a new society within itself. For Marx it was inconceivable that mankind could have overleaped this stage in history and given rise to a durable, global communist society in the epochs of despotism, slavery or serfdom.

But capitalism did not appear out of nowhere: the succession of modes of production prior to capitalism had in turn paved the way for it, and in this sense the whole development of these antagonistic, i.e class-divided, social systems had represented a progressive movement in human history, resulting at last in the material possibility of a classless world community. There is thus no basis for reclaiming the heritage of Marx and simultaneously rejecting the notion of progress as bourgeois.

However, there is indeed a bourgeois version of progress, and, opposed to it, a marxist one.

To begin with, whereas the bourgeoisie tended to see all history leading inexorably towards the triumph of democratic capitalism, an upward, linear march in which all previous societies were in all respects inferior to the present order of things, marxism affirmed the dialectical character of the historical movement. In fact, the very notion of ascent and decline of modes of production means that there can be regressions as well as advances in the historical process. In Anti-Duhring, talking about Fourier and his anticipation of historical materialism, Engels draws attention to the link between the dialectical view of history and the notion of ascent and decline: "Fourier is at his greatest in his conception of the history of society (...) Fourier, as we see, uses the dialectic method in the same masterly way as his contemporary, Hegel. Using these same dialectics, he argues against the talk about illimitable human perfectibility, that every historical phase has its period of ascent and also its period of descent, and he applies this observation to the future of the whole human race" ("Socialism: utopian and scientific").

What Engels is saying here is that there is nothing automatic about the process of historical evolution. Like the process of natural evolution itself, "human perfectibility" is not programmed in advanced. As we will see, there can in fact be social dead-ends, analogous to the dinosaurs - societies which not only decline, but disappear utterly, giving rise to nothing new from within themselves.

Furthermore, even when progress does take place, it generally has a profoundly contradictory character. The destruction of artisan production, in which the producer is still capable of gaining satisfaction both from the process of production and the end product of it, and its replacement by the factory system with its mind-numbing routines, is a clear case in point. But Engels explains this most forcefully when describing the transition from primitive communism to class society. In Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State, having shown both the immense strengths and inherent limitations of tribal life, Engels comes to the following conclusions about how we should view the advent of civilisation:

"The power of this primitive community had to be broken, and it was broken. But it was broken by influences which from the very start appear as a degradation, a fall from the simple moral greatness of the old gentile society. The lowest interests - base greed, brutal appetites, sordid avarice, selfish robbery of the common wealth - inaugurate the new, civilized, class society. It is by the vilest means - theft, violence, fraud, treason - that the old classless gentile society is undermined and overthrown. And the new society itself, during all the two and a half thousand years of its existence, has never been anything else but the development of the small minority at the expense of the great exploited and oppressed majority; today it is so more than ever before".

This dialectical view is also directed towards the future communist society, which in Marx's beautiful passage in the 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, is described as "a return of man to himself, but a return become conscious and accomplished with all the wealth of previous development". In the same way, the communism of the future is seen as a rebirth, on a higher level, of the communism of the past. Engels thus concludes his book on the origins of the state with an eloquent phrase taken from the anthropologist Lewis Morgan, anticipating a communism that "will be a revival, in a higher form, of the liberty, equality and fraternity of the ancient gentes".

But with all these qualifications, it is evident from the Preface that the notion of progress, of "progressive epochs", is fundamental to marxist thought. In the grandiose vision of marxism, beginning (at least!) from the emergence of mankind, to the appearance of class society, to the development of capitalism, and to the great leap into the realm of freedom that awaits us in the future, "the world is not to be comprehended as a complex of readymade things, but as a complex of processes, in which the things apparently stable no less than their mind images in our heads, the concepts, go through an uninterrupted change of coming into being and passing away, in which, in spite of all seeming accidentally and of all temporary retrogression, a progressive development asserts itself in the end" (Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy). Seen from this distance, as it were, it becomes evident that there is a real process of development: at the level of man's capacity to transform nature through the development of more sophisticated tools; at the level of mankind's subjective understanding of himself and the world around him; and thus, at the level of man's capacity to release his slumbering powers and live a life in accord with his deepest needs.

The succession of modes of production

Primitive communism to class society

When Marx provides a "broad outline" of the principal modes of production which have succeeded each other in history, it is by no means meant to be exhaustive. To begin with it only mentions "antagonistic" social forms, i.e the main forms of class society, and does not mention the various forms of non-exploiting society which preceded them. Furthermore, the study of pre-capitalist social forms in Marx's day was in its infancy, so that it was simply not possible to provide an inclusive list of all hitherto existing societies. Indeed, even in the state of present-day historical knowledge, this task remains extremely difficult to complete. In the long period between the dissolution of the original primitive communist social relations, which had their clearest shape among the nomadic hunters of the palaeolithic, and the fully formed class societies which make up the historical civilisations, there were numerous intermediate and transitional forms, as well as forms that simply ended in a historical dead-end, but our knowledge of them remains very limited[2].

The non-inclusion of primitive communist and pre-class societies in the Preface does not at all mean that Marx did not consider it important to study them, on the contrary. From the very beginning, the founders of the historical materialist method recognised that human history begins not with private property, but with communal property: "The first form of ownership is tribal [Stammeigentum] ownership. It corresponds to the undeveloped stage of production, at which a people lives by hunting and fishing, by the rearing of beasts or, in the highest stage, agriculture. In the latter case it presupposes a great mass of uncultivated stretches of land. The division of labour is at this stage still very elementary and is confined to a further extension of the natural division of labour existing in the family (The German Ideology, written in 1847).

When these insights were confirmed by later research - notably the work of Lewis Henry Morgan on the tribes of North America - Marx was extremely enthusiastic, and indeed spent a large part of his later years delving into the problem of primitive social relations, specifically in relation to the questions posed to him by the revolutionary movement in Russia (see the chapter ‘Past and future communism' in our book Communism is not a nice idea but a material necessity). For Marx, Engels and also Rosa Luxemburg, who wrote extensively about this in her Introduction to Political Economy (1907), the discovery that the original forms of human relations were based not on egoism and competition but on solidarity and cooperation, and that centuries and even millennia after the advent of class society there was still a profound and persistent attachment to communal social forms, particularly among the oppressed and exploited classes, was for them a ringing confirmation of the communist outlook and a powerful weapon against the mystifications of the bourgeoisie, for whom the lust for power and property are inherent in human nature.

In Engels' Origins of the Family Private Property and the State, in Marx's Ethnographic Notebooks and Luxemburg's Introduction to Political Economy there is thus a profound respect for the courage, morality and artistic creativity of the "savage" and "barbarian" peoples. But there is no idealisation of these societies. The communism practised in the earliest forms of human society was not engendered by the idea of equality, but out of necessity. It was the only possible form of social organisation in conditions where man's productive capacities had not yet given rise to a sufficient social surplus to support a privileged elite, a ruling class.

Primitive communist relations in all probability emerged with the development of mankind, a species whose capacity to transform his environment to satisfy his material needs marked him off as distinct from all other inhabitants of the animal kingdom. They allowed human beings to become the dominant species on the planet. But if we can generalise from what we know of the most archaic form of primitive communism, found among the Aborigines of Australia, the forms of appropriation of the social product, being entirely collective[3], also held back the development of individual productivity, with the result that the productive forces remained virtually unchanged for millennia. In any case, changing material and environmental conditions, such as the increase in population, at some point made the extreme collectivism of the first forms of human society increasingly untenable, an obstacle to the development of techniques of production (such as pastoralism and agriculture) that could feed larger populations or populations now living in changed social and environmental conditions[4].

As Marx notes "the history of the decline of primitive communities has yet to be written. All we have so far are some rather meagre outlines...(but) the causes of their decline stem from economic facts which prevented them from passing a certain stage of development" (First draft of letter to Vera Zasulich, 1881). The passing of primitive communism and the rise of class divisions does not escape the general rules outlined in the Preface: the relations that human beings created to satisfy their needs become increasingly unable to fulfil their original function, and are therefore plunged into a fundamental crisis, with the result that the communities they sustain either disappear altogether or replace the old relations with new ones better able to develop the productivity of human labour. We have already seen that Engels insisted that, at a certain historical moment, "The power of this primitive community had to be broken, and it was broken". Why? Because "Man was bounded by his tribe, both in relation to strangers from outside the tribe and to himself; the tribe, the gens, and their institutions were sacred and inviolable, a higher power established by nature, to which the individual subjected himself unconditionally in feeling, thought, and action. However impressive the people of this epoch appear to us, they are completely undifferentiated from one another; as Marx says, they are still attached to the navel string of the primitive community".

In the light of anthropological evidence we may well contest Engels' affirmation that the people of tribal societies are so entirely lacking in individuality. But the insight behind this passage remains valid: that in number of key moments and key regions, the old communal methods and relations proved became a fetter on development, and, however contradictory it may seem, the gradual rise of individual property, class exploitation, and a new phase in man's self-alienation, all became "factors of development".

The ‘Asiatic' mode of production

The term ‘Asiatic mode of production' is controversial. Engels unfortunately omits to include the concept in his seminal work on the rise of class society, Origins of the Family, even though Marx's work already contained numerous references to it. Later on, Engels' error was compounded by the Stalinists who virtually outlawed the concept altogether, advancing a very mechanistic and linear view of history as everywhere moving through phases of primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, and capitalism. This schema had distinct advantages for the Stalinist bureaucracy: on the one hand, long after the bourgeois revolution had passed from the agenda of world history, it enabled them to discern the rise of a progressive bourgeoisie in countries like India and China once they had been baptised ‘feudal'; and on the other, it allowed them to avoid embarrassing criticisms of their own form of state despotism, since in the concept of Asiatic despotism, the state, and not a class of individual property owners, directly ensures the exploitation of labour power: the parallels with Stalinist state capitalism are evident.

However, more serious researchers, such as Perry Anderson in an appendix to his book Lineages of the Absolutist State argues that Marx's characterisation of Indian and other contemporary societies as forms of a definite ‘Asiatic mode' was based on faulty information and that the concept has in any case been made so general as to lack any precise meaning.

Certainly, the epithet ‘Asiatic' is confusing in itself. To a greater or lesser extent, all the first forms of class society took on the forms analysed by Marx under this heading, whether in Sumeria, Egypt, India, China, or in more remote regions such as Central and South America, Africa and the Pacific. It is founded on the village community inherited from the epoch prior to the emergence of the state. The state power, often personified by a priestly caste, is based on the surplus product drawn from the village communities in the form of tribute, or, in the case of major construction projects (irrigation, temples, etc) of obligatory labour dues (the ‘corvee'). Slavery may exist but it is not the dominant form of labour. We would argue that while these societies displayed many significant differences, they are united at the level which is most crucial in the classification of an "antagonistic" mode of production: the social relations through which surplus labour is extracted from the exploited class

When we turn to examining the phenomenon of decadence in these social forms, there are, as with ‘primitive' societies, a number of specific characteristics, in that these societies seem to display an extraordinary stability and rarely if ever ‘evolved' into a new mode of production without being battered from the outside. It would however be a mistake to see Asiatic society as lacking in history. There is a vast difference between the first despotic forms that emerged in Hawaii or South America, which are much closer to their original tribal roots, and the gigantic empires that developed in India or China, which gave rise to extremely sophisticated cultural forms.

Nevertheless the underlying characteristic - the centrality of the village community - remains, and provides the key to the ‘unchanging' nature of these societies.

"Those small and extremely ancient Indian communities, some of which have continued down to this day, are based on possession in common of the land, on the blending of agriculture and handicrafts, and on an unalterable division of labour, which serves, whenever a new community is started, as a plan and scheme ready cut and dried. Occupying areas of from 100 up to several thousand acres, each forms a compact whole producing all it requires. The chief part of the products is destined for direct use by the community itself, and does not take the form of a commodity. Hence, production here is independent of that division of labour brought about, in Indian society as a whole, by means of the exchange of commodities. It is the surplus alone that becomes a commodity; and a portion of even that, not until it has reached the hands of the State, into whose hands from time immemorial a certain quantity of these products has found its way in the shape of rent in kind.... The simplicity of the organisation for production in these self-sufficing communities that constantly reproduce themselves in the same form, and when accidentally destroyed, spring up again on the spot and with the same name-this simplicity supplies the key to the secret of the unchangeableness of Asiatic societies, an unchangeableness in such striking contrast with the constant dissolution and refounding of Asiatic States, and the never-ceasing changes of dynasty. The structure of the economical elements of society remains untouched by the storm-clouds of the political sky". [5]

In this mode of production, the barriers to the development of commodity production were far stronger than in ancient Rome or feudalism, and this is certainly the reason why in regions where it dominated, capitalism appears not as an outgrowth of the old system but as a foreign invader. It is equally noticeable that the only ‘eastern' society which to some extent developed its own independent capitalism was Japan, where a feudal system was already in place.

Thus in this social form, the conflict between the relations of production and the evolution of the productive forces often appears as stagnation rather than decline, since while dynasties rose and fell, consuming themselves in incessant internal conflicts, and crushing society under the weight of vast, unproductive, ‘Pharaonic' state projects, still the fundamental social structure remained; and if new relations of production did not emerge, then strictly speaking periods of decline in this mode of production do not actually constitute epochs of social revolution. This is quite consistent with Marx's overall method, which does not posit a unilinear or predetermined path of evolution for all forms of society, and certainly envisages the possibility of societies reaching a dead-end from which no further evolution is possible. We should also recall that some of the more isolated expressions of this mode of production collapsed completely, often because they reached the limits to growth in a particular ecological milieu. This seems to have been the case with the Mayan culture, which destroyed its own agricultural base through excessive deforestation. In this case, there was even a deliberate ‘regression' on the part of a large part of the population, who abandoned the cities and returned to hunting and gathering, even though a memory of the old Mayan calendars and traditions was still assiduously preserved. Other cultures, such as the one on Easter Island, seem to have disappeared entirely, in all probability through irresolvable class conflict, violence and starvation.

Slavery and feudalism

Marx and Engels never denied that their familiarity with the primitive and Asiatic social formations was extremely limited by the state of contemporary knowledge. They were much more confident in writing about ‘ancient' society (ie the slave societies of Greece and Rome) and European feudalism. Indeed, the study of these societies played a significant role in the elaboration of their theory of history, since they provided very clear examples of the dynamic process through which one mode of production succeeded another. This was evident in Marx's early writings (The German Ideology) where he locates the rise of feudalism precisely in the conditions brought about by the decline of Rome

"The third form of ownership is feudal or estate property. If antiquity started out from the town and its little territory, the Middle Ages started out from the country. This different starting-point was determined by the sparseness of the population at that time, which was scattered over a large area and which received no large increase from the conquerors. In contrast to Greece and Rome, feudal development at the outset, therefore, extends over a much wider territory, prepared by the Roman conquests and the spread of agriculture at first associated with it. The last centuries of the declining Roman Empire and its conquest by the barbarians destroyed a number of productive forces; agriculture had declined, industry had decayed for want of a market, trade had died out or been violently suspended, the rural and urban population had decreased. From these conditions and the mode of organisation of the conquest determined by them, feudal property developed under the influence of the Germanic military constitution. Like tribal and communal ownership, it is based again on a community; but the directly producing class standing over against it is not, as in the case of the ancient community, the slaves, but the enserfed small peasantry".

The very term decadence frequently evokes images of the later Roman empire - of orgies and emperors drunk with power, of gladiatorial combats witnessed by huge crowds baying for blood. Such pictures certainly tend to focus on the ‘superstructural' elements of Roman society but they do reflect a reality unfolding at the very foundations of the slave system; and thus revolutionaries like Engels and Rosa Luxemburg felt justified in pointing to the decline of Rome as a kind of portent of what lay in store for humanity if the proletariat did not succeed in overthrowing capitalism: "the collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration - a great cemetery" (Junius Pamphlet).

Ancient slave society was a far more dynamic social formation than the Asiatic mode, even if the latter did make its own contribution to the rise of ancient Greek culture and thus to the slave mode of production in general (Egypt in particular being looked up to as a venerable repository of wisdom). This dynamism flowed to a large extent from the fact that, as the contemporary saying had it, "everything is for sale in Rome": the commodity form had advanced to the point where the old agrarian communities were more and more a fond memory of a lost golden age, and a mass of human beings had themselves become commodities to be bought and sold in the slave markets. Production by large armies of slaves, even when there remained large areas of the economy where productive work was still carried out by small peasants or artisans, more and more assumed a key role in the central foci of the ancient economy - the great landed estates, public works, and the mines. This great ‘invention' of the ancient world was, for a considerable period of time, a formidable ‘form of development', allowing the free citizens to be organised into mighty armies which, by conquering new lands for the empire, added fresh supplies of slave labour. But by the same token there clearly came a point at which slavery was transformed into a definite fetter on further development. Its inherently unproductive nature lay in the fact that it gave the producer absolutely no incentive to give the best of his productive capacities, nor the slave-owner any incentive to invest in developing better techniques of production, since a supply of fresh slaves was always a cheaper option. Hence the extraordinary gap between the philosophical/scientific advances made by the class of thinkers whose leisure was founded on a platform held up by slaves, and the extremely limited practical application of the theoretical or technical advances that were made. This was the case, for example, with the water-mill, which played such a crucial role in the development of feudal agriculture. It was actually invented in Palestine at the turn of the first century AD, but its use was never generalised throughout the Empire. At a certain point, therefore, the incapacity of the slave mode of production to radically augment the productivity of labour made it increasingly impossible to maintain the vast armies required to fuel it. Rome overreached itself, caught into an insoluble contradiction that expressed itself in all the familiar features of its decline.

In Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, the historian Perry Anderson enumerates some of economic, political and military expressions of this clogging up of Roman society's productive force by the slave relation in the early 3rd century: "by mid century, there was a complete collapse of the silver coinage, while by the end of the century, corn prices had rocketed to levels 200 times over their rates in the early Principiate. Political stability degenerated apace with monetary stability. In the chaotic fifty years from 235 to 284, there were no less than 20 Emperors, eighteen of whom died violent deaths, one a captive abroad, the other a victim of the plague - all fates expressive of the times. Civil wars and usurpations were virtually uninterrupted, from Maximus Thrax to Diocletian. They were compounded by a devastating sequence of foreign invasions and attacks along the frontiers, stabbing deep into the interior (...) Domestic political turmoil and foreign invasions soon brought successive epidemics in their train, weakening and reducing the populations of the Empire, already diminished by the destruction of war. Lands were deserted, and supply shortages in agrarian output developed. The tax system disintegrated with the depreciation of the currency, and fiscal dues reverted to deliveries in kind. City construction came to an abrupt halt, archeologically attested throughout the Empire; in some regions, urban centres withered and contracted" (p 83-84).

Anderson goes on to show how, in response to this profound crisis, the Roman state power, based fundamentally upon a reorganised and expanded army, swelled to vast proportions and achieved a certain stabilisation that lasted up to a hundred years. But since "the swelling of the state was accompanied by a shrinkage of the economy...." (p 92), this revival merely paved the way to what he calls "the final crisis of Antiquity", imposing the necessity to progressively abandon the slave relation. An equally key factor in the demise of the slave mode of production was the generalisation of revolts by slaves and other exploited and oppressed classes throughout the Empire in the 5th century AD (such as the so-called ‘Bacuadae' uprisings), which took place on a far wider scale than the Spartacus rebellion of the first century - although the latter is justly remembered for its incredible audacity and the profound yearning for a better world which inspired it.

The decadence of Rome thus corresponded precisely to the formula of Marx, and took on a clearly catastrophic character. Despite recent efforts of bourgeois historians to present it as a gradual and imperceptible process, it manifested itself as a devastating crisis of under-production in which society was less and less able to produce the basic necessities of life - a veritable regression in the productive forces, in which numerous areas of knowledge and technique were effectively buried and lost for centuries. This was not a one-way slide - as we have noted the great crisis of the third century was followed by a relative revival that was not ended until the final wave of barbarian invasions - but it was inexorable.

The collapse of the Roman system was the precondition for the emergence of new relations of production as a major stratum of landowners took the revolutionary step of eliminating slave labour in favour of the colonus system - the forerunner of feudal serfdom, in which the producer, while being directly compelled to work for the landowning class, is also given his own plot of land to cultivate. The second ingredient of feudalism, mentioned by Marx in the passage from The German Ideology, was the barbarian, ‘Germanic' element, combining the emerging hierarchy of a warrior aristocracy with the remnants of communal ownership, which was stubbornly maintained by the peasantry. A long period of transition ensued, in which slave relations had not yet entirely disappeared and the feudal system gradually asserted itself, reaching its true ascent only in the first centuries of the new millennium. And while as we have noted in various areas (urbanisation, the relative independence of art and philosophical thought from religion, medicine, etc) the rise of feudal society represented a marked regression with regard to the achievements of Antiquity, the new social relations gave both lord and serf a direct interest in increasing the yield of their share of the land and permitted the generalisation of a number of important technical advances in agriculture: the iron plough and the iron harness that allowed it to be horse-drawn, the water mill, the three field system of crop rotation, etc. The new mode of production thus permitted a revival of the cities and a new flourishing of culture, expressed most graphically in the great cathedrals and universities that emerged in the 12th and 13th centuries.

But like the slave system before it, feudalism also began to reach its ‘external' limits:

"Within the next hundred years (of the 13th century), a massive general crisis struck the whole continent...The deepest determinant of this general crisis probably lay...in a ‘seizure' of the mechanisms of reproduction of the system at a barrier point of its ultimate capacities. In particular, it seems clear that the basic motor of rural reclamation, which had driven the whole feudal economy forwards for three centuries, eventually over-reached the objective limits of both terrain and social structure. Population continued to grow while yields fell on the marginal lands still available for conversion at the existing levels of technique, and soil deteriorated through haste or misuse. The last reserves of newly reclaimed land were usually of poor quality, wet or thin soil that was more difficult to farm, and on which inferior crops such as oats were sown. The oldest lands under plough were, on the other hand, liable to age and decline from the very antiquity of their cultivation...." (Anderson, p 197).

As the expansion of feudal agrarian economy came up against these barriers, disastrous consequences ensued in the life of society: crop failure, famines, collapse of grain prices combined with soaring prices of goods produced in the urban centres:

"This contradictory process affected the noble class drastically, for its mode of life had become ever more dependent on the luxury goods produced in the towns...while demesne cultivation and servile dues from its estates yielded progressively decreasing incomes. The result was a decline in seigneurial revenues, which in turn unleashed an unprecedented wave of warfare as knights everywhere tried to recoup their fortunes with plunder. In Germany and Italy, this quest for booty in a time of dearth produced the phenomenon of unorganised and anarchic banditry by individual lords...In France, above all, the Hundred years' War - a murderous combination of civil war between the Capetian and Burgundian houses and an international struggle between England and France, also involving Flanders and the Iberian powers - plunged the richest country in Europe into unparalleled disorder and misery. In England, the epilogue of final continental defeat in France was baronial gangsterism of the Wars of the Roses...To complete a panorama of desolation, this structural crisis was over-determined by a conjunctural catastrophe: the invasion of the Black Death from Asia in 1348".

The Black Death, wiping out up to a third of the European population, hastened the final demise of serfdom. It brought about a chronic shortage of labour in the countryside, forcing the noble class to shift from traditional feudal labour dues to the payment of wages; but at the same time the nobility tried to hold the clock back by imposing draconian restrictions on wages and the movement of labourers, a Europe-wide tendency classically codified in the Statute of Labourers decreed in England immediately after the Black Death. The further result of this noble reaction was to provoke widespread class struggle, again most famously given shape by the huge Peasants' Revolt in England in 1381. But there were comparable uprisings all over Europe during this period (the French ‘Jacquerie', labourers' revolts in Flanders, the rebellion of the Ciompi in Florence, and so on).

As in the decline of ancient Rome, the mounting contradictions of the feudal system at the economic level thus had their repercussions at the level of politics (wars, social revolts) and in the relationship between man and nature; and all of these elements in turn accelerated and deepened the general crisis. As in Rome, the general decline of feudalism was the result of a crisis of underproduction, the inability of the old social relations to allow the production of the basic necessities of daily existence. It is important to note that although the slow emergence of commodity relations in the towns acted as a dissolving factor on feudal bonds, and were further accelerated by the effects of the general crisis (wars, famines, the Black Death), the new social relations could not really take wing until the old system had entered into a state of self-contradiction which resulted in a grave decline in the forces of production:

"One of the most important conclusions yielded by an examination of the great crash of European feudalism is that - contrary to widely received beliefs among Marxists - the characteristic ‘figure' of a crisis in a mode of production is not one in which vigorous (economic) forces of production burst triumphantly through retrograde (social) relations of production, and promptly establish a higher productivity and society on their ruins. On the contrary, the forces of production typically tend to stall and recede within the existent relations of production; these must then first be radically changed and reordered before new forces of production can be created and combined for a globally new mode of production. In other words, the relations of production generally change prior to the forces of production in an epoch of transition, and not vice versa" (p 204). As with the decline of Rome, a period of regression in the old system was a precondition for the flourishing of a new mode of production.

Again, as in the period of Roman decadence, the ruling class sought to preserve its tottering system by increasingly artificial means. The passing of savage laws to control the mobility of labour and the tendency of rural labourers to escape to the towns, the attempt to rein in the centrifugal tendencies of the aristocracy through the centralisation of monarchical power, the use of the Inquisition to impose a rigid ideological control over all expressions of heretical and dissident thought, the debasing of the coinage to ‘solve' the problem of royal indebtedness... all these trends represented the attempt of a dying system to postpone its final demise, but they could not prevent it. Indeed, to a large extent, the very means used to preserve the old system were transformed into bridgeheads of the new system: this was the case, for example, with the centralising monarchies of Tudor England, who were in great part creating the necessary conditions for the emergence of the modern capitalist nation state

Much more clearly than in the decadence of Rome, the epoch of feudal decline was also an epoch of social revolution in the sense that that a genuinely new and revolutionary class came out of its entrails, a class with a world outlook that challenged the old ideologies and institutions, and a mode of economy that found the feudal relation an intolerable obstacle to its expansion. The bourgeois revolution made its triumphant entry onto the stage of history in England in the 1640s, even if had to wait over a century and a half before its subsequent and even more spectacular victories in France in the 1790s. This long time-frame was a possibility for the bourgeois revolution because it is the crowning political point of a long process of economic and social development inside the shell of the old system, and because it followed different rhythms in different nations.

The transformation of ideological forms

"In studying such transformations it is always necessary to distinguish between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophic - in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out".

All class societies are maintained by a combination of outright repression and the ideological control exerted by the ruling class through its numerous institutions: family, religion, education, and so on. Ideologies are never a purely passive reflection of the economic base, but contain their own dynamic which at certain moments can actively impact on the underlying social relations. In affirming the materialist conception of history, Marx was obliged to "distinguish" between the "material transformation of the economic conditions" and the "ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict" because hitherto the prevailing approach to history had been to emphasise the latter at the expense of the former.

When analysing the ideological transformations that take place in an epoch of social revolution, it is important to remember that while they are ultimately determined by the economic conditions of production, this does not happen in a rigid and mechanical way, not least because such a period is never one of pure descent or debasement, but is marked by an increasing clash between contradictory social forces. It is characteristic of such epochs that the old ruling ideology, corresponding less and less to a changing social reality, tends to decompose and give way to new world-outlooks which can serve to actively inspire and mobilise the social classes opposed to the old order. In the process of decomposing, the old ideologies - religious, philosophical, artistic - frequently succumb to pessimism, nihilism, and an obsession with death, while the ideologies of rising or rebellious classes are more often optimistic, life-affirming, looking forward to the dawn of a world radically transformed.

To take one example: in the dynamic period of the slave system, philosophy tended, within the limits of the day, to express mankind's efforts to "know thyself" in Socrates immortal phrase - to grasp the real dynamic of nature and society through rational thought, without the intermediary of the divine. In its period of descent, philosophy itself tended to retreat into the justification of despair or of irrationality, as in Neoplatonism and its links to the numerous mystery cults that flourished in the later Empire.

This tendency cannot be grasped in a one-sided manner however: in periods of decadence the old religions and philosophies were also confronted with the rise of new revolutionary classes or the rebellion of the exploited, and these generally also took on a religious form. Thus, in ancient Rome, the Christian religion, though certainly influenced by the eastern mystery cults, began as a protest movement of the dispossessed against the dominant order, and later, as an established power in its own right, provided a framework for the preservation of many of the cultural acquisitions of the ancient world. This dialectic between the old order and the new was a feature of ideological transformations during the decline of feudalism as well. On the one hand:

"The period of stagnation saw the rise of mysticism in all its forms. The intellectual form with the ‘Treatise on the Art of Dying', and above all, ‘The Imitation of Jesus Christ'. The emotional form with the great expressions of popular piety exacerbated by the influence of the uncontrolled elements of the mendicant clergy: the ‘flagellants' wandered the countryside, lacerating their bodies with whips in village squares in order to strike at human sensibility and call Christians to repent. These manifestations gave rise to imagery of often dubious taste, as with the fountains of blood that symbolised the redeemer. Very rapidly the movement lurched towards hysteria and the ecclesiastical hierarchy had to intervene against the troublemakers, in order to prevent their preaching from increasing the number of vagabonds (...) Macabre art developed... the sacred text most favored by the more thoughtful minds was the Apocalypse." (J. Favier, From Marco Polo to Christopher Columbus, p152f).

On the other hand, the demise of feudalism also saw the rise of the bourgeoisie and its world view, expressing itself in the magnificent flowering of art and science in the period of the Renaissance. And even mystical and millenarian movements like the Anabaptists were, as Engels pointed out, often intimately linked to the communist aspirations of the exploited classes. Such movements could not yet provide a historically viable alternative to the old system of exploitation, and their millenarian dreams were more often fixated on a primitive past than a more advanced future, but they nevertheless played a key role in the processes bringing about the destruction of the decaying mediaeval hierarchy.

In a decadent epoch, the general cultural decline is never absolute: at the artistic level, for example, the stagnation of the old schools can also be countered by new forms which above all express a human protest against an increasingly inhuman order. The same can be said at the level of morality. If morality is ultimately an expression of the social nature of mankind, and if periods of decadence are expressions of the break-down of social relations, then they will tend to be characterised by a concomitant break-down in morality, a tendency towards the collapse of basic human ties and the triumph of the anti-social impulses. The perversion and prostitution of sexual desire, the flourishing of casual murder, robbery and fraud, and above all the suspension of the moral order in warfare become the order of the day. But again, this should not be seen in a rigid and mechanical way, in which periods of ascent are marked by superior human behaviour and periods of decline by a sudden plunge into wickedness and depravity. The undermining and shattering of old moral certainties can equally express the rise of a new system of exploitation, in comparison to which the old order may seem comparatively benign, as noted in the Communist Manifesto with regard to the rise of capitalism:

"The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors', and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment'. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom - Free Trade".

And yet, such is the understanding of Hegel's ‘Cunning of Reason' in the thinking of Marx and Engels that they were able to recognise that this moral ‘decline', this commodification of the world, was in fact a force for progress which was helping to sweep away the static feudal order that lay behind it and pave the way for the genuinely human moral order that lay in front of it.

[1] Preface to A contribution to the critique of political economy.

[2] For example, the settled and already quite hierarchical hunting societies which were able to hold extensive food stocks, the various semi-communist forms of agrarian production, the ‘tributary empires' formed by semi-barbarian pastoralists like the Huns and the Mongols, etc

[3] Among the Australian tribes when the traditional way of life was still in force, the hunter who brought in the game kept nothing for himself, but immediately handed over the product to the community in the shape of certain complex kinship structures. According to the work of the anthropologist Alain Testart, Le Communisme Primitif, 1985, the term primitive communism should only be applied to the Australians, which he sees as the last remnant of a social relationship which had probably been general during the palaeolithic period. This is a matter for debate. Certainly even among the nomadic hunter-gatherer peoples, there are wide differences in the way that the social product is distributed, even though all of them give priority to the maintenance of the community, and as Chris Knight points out in his Blood Relations, Menstruation and the Origins of Culture, 1991, what he calls the ‘own-kill rule' (ie prescribed limits on what the hunter may consume of his kill) is extremely widespread among hunting peoples.

[4] It must of course be borne in mind that the dissolution of primitive social relations was not a one-off event but followed very different rhythms in different parts of the globe; it is a process spanning millennia and it is only now reaching its last tragic chapters in the remotest regions of the globe, such as the Amazon and Borneo.

[5] Capital, 1, Part IV, Chapter XIV

Deepen:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Germany 1918-19 (iii): Formation of the party, absence of the International

- 5744 reads

When World War I broke out, the socialists met on 4th August 1914 to engage the struggle for internationalism and against the war: there were seven of them in Rosa Luxemburg's apartment. This reminiscence, which reminds us that the ability to swim against the current is one of the most important of revolutionary qualities, should not lead us to conclude that the role of the proletarian party was peripheral to the events which shook the world at that time. The contrary was the case, as we have tried to show in the first two articles of this series to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the revolutionary struggles in Germany. In the first article, we put forward the thesis that the crisis in the Social-Democracy, in particular in the German SPD[1] - the leading party of the Second International - was one of the most important factors making it possible for imperialism to march the proletariat to war. In Part 2 we argued that the intervention of revolutionaries was crucial in enabling the working class, in the midst of war, to recover its internationalist principles, thus making possible the ending of the imperialist carnage by revolutionary means (the November Revolution of 1918). In so doing, they set down the foundations for a new party and a new International.

And in both of these phases, we pointed out, the capacity of revolutionaries to understand the priority of the moment was the precondition to their playing such an active and positive role. After the breaking up of the international in face of war, the task of the hour was to understand the causes of this fiasco, and to draw the lessons. In the struggle against war, the responsibility of true socialists was to be the first to raise the banner of internationalism, to light up the path towards revolution.

The councils and the class party

The workers' uprising of 9th November 1918 brought the war to an end on the morning of November 10th 1918. The German Emperor and countless German princelings were overthrown - a new phase of the revolution was beginning. Although the November uprising was led by the workers, Rosa Luxemburg called it the "revolution of the soldiers". This was because the spirit which dominated it was that of a profound longing for peace. A desire which the soldiers, after four years in the trenches, embodied more than any other social group. This was what gave that unforgettable day its specific colour and its glory, and which fed its illusions. Since even parts of the bourgeoisie were relieved that the war was finally over, general fraternisation was the mood of the day. Even the two main protagonists of the social struggle, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, were affected by the illusions of 9th November. The illusion of the bourgeoisie was that it could still use the soldiers coming from the front against the workers. In the days which followed, this illusion dissipated. The "grey coats"[2] wanted to go home, not to fight the workers. The illusion of the proletariat was that the soldiers were already on their side and wanted revolution. During the first sessions of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils which were elected in Berlin on November 10th, the soldiers' delegates nearly lynched those revolutionaries who spoke of the necessity to continue the class struggle, and who identified the new Social Democratic government as the enemy of the people.

These workers' and soldiers' councils were, in general, marked by the weight of human inertia which curiously marks the beginning of every great social upheaval. Very often, soldiers elected officers as their delegates, and workers appointed the same Social-Democratic candidates they had voted for before the war. Thus, these councils found nothing better to do than appoint a government led by the warmongers of the SPD, and to decide their own suicide in advance by calling general elections to a parliamentary system.

Despite the hopelessness of these first measures, the workers' councils were the heart of the November Revolution. As Rosa Luxemburg pointed out, it was above all the appearance of these organs which proved and embodied the essentially proletarian character of this upheaval. But now a new phase of the revolution was opened up, in which the central question was no longer that of the councils but of the class party. The phase of illusions was coming to an end, the moment of truth, the outbreak of civil war was approaching. The workers' councils, through their very function and structure as organs of the masses, are capable of renewing and revolutionising themselves from one day to the next. The central question now was: would the determined revolutionary, proletarian outlook gain the upper hand within the councils, within the working class?

In order to be victorious, the proletarian revolution needs a unified, centralised political vanguard in which the class as a whole has confidence. This was perhaps the most important lesson of the October Revolution in Russia the previous year. The task of this party, as Rosa Luxemburg had argued in 1906 in her pamphlet about the Mass Strike, is no longer to organise the masses, but to give the class a political leadership, and a real confidence in its own capacities.

The difficulties in the regroupment of revolutionaries

But at the end of 1918 in Germany there was no such party in sight. Those socialists who opposed the pro-war policies of the SPD were mainly to be found in the USPD, the former party opposition subsequently excluded by the SPD. A mixed bunch with tens of thousands of members, from pacifists and those who wanted a reconciliation with the warmongers, to principled revolutionary internationalists. The main organisation of these internationalists, the Spartakusbund, was an independent fraction within the USPD. Other, smaller internationalist groups, such as the IKD[3] (which emerged from the left opposition in Bremen) were organised outside the USPD. The Spartakusbund was well known and respected among the workers. But the recognised leaders of the strike movements against the war were not these political groups, but the informal structure of factory delegates, the "revolutionäre Obleute". By December 1918 the situation was becoming dramatic. The first skirmishes leading to open civil war had already taken place. But the different components of a potential revolutionary class party - the Spartakusbund, the other left elements in the USPD, the IKD, the Obleute were still separate entities, and still mainly hesitant.

Under the pressure of events, the question of the foundation of the party began to be posed more concretely. In the end, it was dealt with in a great hurry.

The first national congress of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils had come together in Berlin on 16th December. While 250,000 radical workers demonstrated outside to put pressure on the 489 delegates (of whom only 10 represented Spartakus, 10 the IKD), Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were not allowed to address the meeting (under the pretext that they had no mandate). When this congress concluded by handing over its power to a future parliamentary system, it became clear that revolutionaries would have to reply to this in a unified manner.

On 14th December 1918, the Spartakusbund published a programmatic declaration of principles: What does the Spartakusbund want?

On 17th December, a national conference of the IKD in Berlin called for the dictatorship of the proletariat, and for the formation of a class party through a process of regroupment. The conference failed to reach agreement on whether or not to participate in the coming elections to a national parliamentary assembly.

Around the same time, leaders within the left of the UPSD, such as Georg Ledebour, and among the factory delegates, such as Richard Müller, began to raise the question of the need of a united workers' party.

At the same moment, delegates of the international youth movement were meeting in Berlin, where they set up a secretariat. On 18th December, an international youth conference was held, followed by a mass meeting in Berlin Neukölln, where Karl Liebknecht and Willi Münzenberg spoke.

It was in this context that a meeting in Berlin of Spartakusbund delegates decided on 29th December to break with the USPD and form a separate party. Three delegates voted against this decision. The same meeting called for a joint conference of Spartakus and the IKD, to begin in Berlin the following day, at which 127 delegates from 56 cities and sections participated. This conference was partly made possible through the mediation of Karl Radek, delegate of the Bolsheviks. Many of these delegates did not realise until their arrival that they had been summoned to form a new party[4]. The factory delegates were not invited to participate, since it was felt that it would not yet be possible to unite them with the very decided revolutionary positions defended by a majority of the often very young members and supporters of Spartakus and the IKD. Instead, it was hoped that the factory delegates would join the party once it had been formed.[5]

What became the founding congress of the KPD brought together leading figures of the Bremen Left (including Karl Radek, althought he represented the Bolsheviks at this meeting), who felt that the foundation of the party was long overdue, and of the Spartakusbund, such as Rosa Luxemburg and above all Leo Jogiches, whose principle worry was that this step might be premature. Paradoxically, both sides had good arguments to justify their stances.

The Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) sent six delegates to the conference, two of whom were prevented from participating by the German police.[6]

The founding congress: a great programmatic advance