International Review no.128 - 1st quarter 2007

- 8236 reads

Capitalist chaos without end

- 2919 reads

The dramatic situation of a Middle East that has been plunged into chaos reveals the profound cynicism and duplicity of the bourgeoisie in all countries. Each one of them pretends that it wants to bring peace, justice and democracy to the populations who have been subjected to daily horrors and massacres for years. But their fine speeches are just a mask for the defence of sordid imperialist interests and a justification for military and diplomatic interventions which are the main cause behind today's worsening conflicts. The cynicism and hypocrisy of it all have been confirmed in particular by the hurried execution of Saddam Hussein, which is just one illustration of the bloody settling of scores between rival bourgeois factions.

Why the hurry to execute Saddam Hussein?

The judgement and execution of Saddam Hussein were spontaneously hailed by Bush as a "victory for democracy". There's some truth in this: the bourgeoisie has so often justified its crimes in the name of democracy. We have already devoted an article to the subject in this Review (International Review n°66, 1991, "The massacres and crimes of the great democracies"). With boundless cynicism, Bush also announced on 5 November 2006, when he was in Nebraska in the middle of an election campaign, that the death sentence handed out to Saddam was "a justification for the sacrifices willingly accepted by the US forces" since March 2003 in Iraq. So for Bush the hide of a murderer is worth the more than 3000 young Americans killed in Iraq (that's more than the victims of the destruction of the Twin Towers), most of them in the flower of their youth. And the hundreds of thousands of Iraqi dead since the beginning of the American intervention count for nothing at all. In fact, since the US occupation began, there have been more than 600,000 deaths and the Iraqi government is no longer counting so as not to "undermine morale".

The USA had every interest in ensuring that the execution of Saddam took place before the next round of trials. The reason for this is they would have brought up far too many compromising facts. It has been deemed necessary to obscure all memory of the total support given by the US and the Western powers to Saddam's policies between 1979 and 1990, and in particular during the war between Iraq and Iran between 1980 and 1988.

One of the main accusations against Saddam was the deadly use of chemical weapons against 5000 Kurds in Halabjah in 1988. This massacre was part of a war which cost 1,200,000 dead and twice as many wounded, and throughout which "the Butcher of Baghdad" was supported by the US and most of the Western powers. Having been taken by the Iranians, the town was then re-taken by the Iraqis who decided to carry out an operation of repression against the Kurdish population. The massacre was only the most spectacular in a campaign of extermination baptised "Al Anfal" ("war booty"), which claimed 180,000 Iraqi Kurdish victims between 1987 and 1988.

Saddam began this war by attacking Iran with the full support of the Western powers. After the emergence of a Shi'ite Islamic republic in Iran in 1979, with Ayatollah Khomeini denouncing the US as the "Great Satan", and after US president Carter's failure to overturn the regime, Saddam Hussein took on the role regional cop for the US and the Western bloc by declaring war on Iran and weakening it through 8 years of war. The Iranian counter-attack would have resulted in victory for Tehran if Iraq had not been given US military support. In 1987, the Western bloc led by the US mobilised a formidable armada in the waters of the Gulf, deploying more than 250 war-ships from nearly all the major Western countries, with 35,000 men on board and equipped with the most sophisticated war-planes. Under the guise of "humanitarian intervention", this force destroyed an oil platform and several of the Iranian navy's most effective ships. It was thanks to this support that Saddam was able to sign a peace agreement which allowed Iraq to keep its pre-war borders.

Saddam originally came to power with the support of the CIA, executing his Shi'ite and Kurdish rivals but also other Sunni chiefs within the Baath party, who were falsely accused of conspiring against him. He was courted and honoured as a great statesman for years, being recognised for example as a "great friend of France" (and of Chirac and Chevènement in particular). The fact that he distinguished himself throughout his political career by bloody executions and massacres of all kinds (hangings, beheadings, torturing opponents, use of chemical weapons, slaughter of the Shi'ite and Kurdish populations) never bothered any bourgeois politician until it was "discovered" on the eve of the Gulf War that Saddam was a bloody and frightful tyrant.1 We should also remember that Saddam was lured into a trap when he believed that he had been given the green light by Washington to invade Kuwait in the summer of 1990, thus providing the US with a pretext to mount a gigantic military mobilisation against him. Thus the US set up the first Gulf War of January 1991 and from now on Saddam Hussein would be deemed public enemy number one. The Desert Storm campaign, presented by the official propaganda as a "clean war", a kind of video war game, actually cost 500,000 lives in 42 days, with 106,000 air raids dropping 100,000 tons of bombs, experimenting with the whole gamut of murderous weapons (napalm, cluster bombs, depression bombs...). Its essential aim was to make a demonstration of the crushing military superiority of the US and to force its former allies, now becoming potentially dangerous imperialist rivals, to take part in the war under US command at a moment when the old bloc alliances were falling apart.

With the same degree of Machiavellianism, the US and its "allies" were soon involved in further machinations. Having called upon the Kurds in the North and the Shi'ites in the South to rise up against the Saddam regime, they left him with the elite troops he needed to drown these rebellions in blood, since they had every interest in keeping Iraq together. The Kurdish population in particular was subjected to the most atrocious massacres.

The hired hacks of European media, even joined by Sarkozy the hitherto pro-American French presidential hopeful, are now hypocritically denouncing the "poor choice", the "mistake", the "botched job" of Saddam's hurried execution. It is true that the circumstances of the execution will further exacerbate hatred between the religious groupings. It may have pleased the more fanatical Shi'ite groupings but certainly not the Sunnis, while the fact that it took place at the beginning of Eid, a very important festival in Islam, shocked most Muslims. What's more, Saddam Hussein may now be seen by generations who have not lived under his iron heel as a martyr.

But none of the bourgeoisies had a choice in the matter because they had the same interest as the Bush administration in seeing this execution rushed through in order to hide and erase the memory of their complicity in the atrocities of the past and their responsibility in the spiral of barbarism going on today. The situation in the Middle East is reaching the heights of absurdity, but it is only a symbol of the total impasse the system has reached everywhere.2

The headlong flight into war in the Middle East

Recent developments in the conflict between Israel and the various Palestinian factions, who have also been at each others' throats, have reached the height of absurdity. What is striking is the way that the different bourgeoisies involved have been pushed by the force of circumstances to take decisions which are altogether contradictory and irrational, even from the standpoint of their short-term strategic interests.

When Ehud Olmert offered his hand to the president of the Palestinian Authority Mahmoud Abbas, along with a few concessions to the Palestinians such as the withdrawal of a number of roadblocks and the promise to unfreeze $100 million in "humanitarian aid", the media immediately began talking about the revival of the peace process. Mahmoud Abbas has certainly tried to cash in on these offers in his competition with Hamas, since the aim of these pseudo-concessions was to show that his policy of cooperation with Israel could bring advantages.

But it was Ehud Olmert himself who largely sabotaged any common approach with the president of the Palestinian Authority when he was compelled by the pressure from the ultra-conservative factions in his government to renew the policy of implanting Israeli settlements in the occupied territories and to step up the destruction of Palestinian houses in Jerusalem.

The accords between Israel and Fatah resulted in Israel authorising Egypt to deliver arms to Fatah in order to give it an advantage in its struggle against Hamas. However, the umpteenth Sharm-el-Sheikh summit between Israel and Egypt was totally overshadowed by the Israeli army's new military operation in Ramallah on the West Bank and by the renewed air-raids in the Gaza Strip in response to sporadic rocket fire. So the message about wanting to revive peace talks was drowned out and Israel's intentions made to look very contradictory.

Another paradox is that at the moment that Olmert and Abbas met, and just before the Israel-Egypt summit, Israel announced that it possesses nuclear weapons and made open threats about using them. Although this warning was directed essentially against Iran, which is trying to attain the same status, it goes out indirectly to all Israel's neighbours. How were the latter to start negotiations with such a belligerent and dangerous power?

Furthermore, this declaration can only push Iran to move further in the same direction and legitimate its ambitions to becoming a gendarme and a protector of the region, resorting to the same logic of "deterrence" as all the great powers.

But it is not just the Zionist state which is acting in this way - it looks as if each protagonist is becoming increasingly incapable of acting for the best defence of its strategic interests.

Abbas for example has taken the risk of unleashing a test of strength with the militias of Hamas and has poured oil on the fire by announcing his aim of holding elections in Gaza. This could only be seen by Hamas, which was "democratically" elected only last January, as a real provocation. But this test of strength, which has also taken the form of bloody street-fighting, was the only way that the Palestinian Authority could try to break out of the Israeli blockade and the blocking of international aid in force since Hamas came to power. Not only has the blockade been a disaster for the local population, which has been unable to go to work outside the areas boxed in by the Israeli army and police, it has also provoked the strike by 170,000 Palestinian civil servants in Gaza and the West Bank who have not been paid any wages for months (especially in vital sectors like health and education). The anger of the civil servants, which extends into the ranks of the police and the army, has been exploited both by Hamas and by Fatah as a means to recruit people for their respective militias, each one blaming the situation on the other, while young kids between 10 and 15 are being enrolled en masse as cannon fodder in this murderous conflict.

Hamas meanwhile has been trying to take advantage of the confusion by negotiating directly with Israel for an exchange of prisoners, proposing to swap the Israeli corporal captured in June for some of its own activists.

The bloody chaos that has come out of a year's explosive co-habitation between the elected Hamas government and the president of the Palestinian Authority remains the only prospect. Given this suicidal policy, there should be no illusions about the truce agreed at the end of the year between the Fatah and Hamas militias. It will certainly be punctuated by murderous confrontations: car bombs, street battles, kidnapping, all of it sowing terror and death among the already impoverished population of the Gaza strip. And to cap it all, the Israeli raids on the West Bank or the brutal searches by the Israeli army and police mean that children and school students are regularly being killed in the crossfire, while the Israeli proletariat, already bled white by the war effort, is subjected to revenge operations by Hamas on the one hand and Hezbollah on the other.

At the same time, the situation in South Lebanon, where UN forces have been deployed, is far from being secure. Instability has increased since the assassination of the Christian leader Pierre Gemayel. There has been a major demonstration of force by Hezbollah and other Shi'ite militias, as well as by the Christian faction led by General Aoun who has provisionally rallied to Syria, besieging the presidential palace in Beirut for several days, while at the same time armed Sunni groups were threatening the Lebanese parliament and its Shi'ite president Nabil Berri. Tension between the rival factions is reaching a peak. As for the UN mission - disarming Hezbollah - no one takes that seriously.

In Afghanistan, the deployment of 32,000 troops under NATO's international forces and of 8500 Americans has proved ineffective. The struggle against al Qaida and the Taliban, who have carried out at least a hundred attacks in the south of the country, is getting inexorably bogged down. The balance sheet of this guerrilla war is 4,000 dead for 2006 alone. Pakistan, which in principal is the USA's ally, still serves as a base for al Qaida and the Taliban.

Each state, each faction is pushed headlong into military adventurism, regardless of the defeats they suffer.

The most revealing impasse is the one facing the world's strongest power. The policy of the American bourgeoisie is caught up in all sorts of contradictions. The report by James Baker, former adviser to Bush senior and appointed by the federal government, concluded that the war in Iraq has been a failure and advocated a change of policy: opening diplomatic relations with Syria and Iran and gradually withdrawing the 144,000 troops stuck in Iraq. And what happened? Bush junior was forced to renew part of his administration, notably by replacing Rumsfeld with Robert Gates as Defence Secretary; a number of people were made scapegoats for the Iraq fiasco and have been got rid of, notably two major commanding officers of the occupation forces in Iraq. But above all Bush has announced a new "surge" of US troops to Iraq: 21,500 reinforcements, for an army already heavily dependent on reservists, are to be sent to "secure" Baghdad. The shift in the majority in both houses of Congress, now dominated by the Democrats, has changed nothing: any disengagement or refusal to release new military credits for the war in Iraq will be seen as an admission of weakness by the US and the Democrats don't want to assume responsibility for this. The whole American bourgeoisie, like all the other bourgeois cliques or states, is caught in the infernal machine of militarism, where every new attempt to defend its imperialist interests against its rivals only ends up making matters worse.

The African continent: another edifying illustration of capitalist barbarism

Terrible atrocities are commonplace on the African continent today. After decades of slaughter in Zaire and Rwanda, after the confrontation between cliques in the Ivory Coast, further exacerbated by rivalries between the great powers, other regions are being bathed in blood and fire.

In Sudan, the "rebellion" against the pro-Islamist government in Khartoum is today split up into a myriad of different factions, all fighting among themselves, manipulated by this or that power in an increasingly unstable game of alliances. In the last three years, the Darfur region in the west of Sudan has seen 400,000 deaths and more than a million and half refugees; hundreds of villages have been destroyed and the former inhabitants pushed into immense camps in the desert, dying of hunger, thirst and disease, regularly suffering the attacks of various armed gangs or of the Sudanese government forces. The flight of rebel forces has led to the conflict being exported to other regions, notably the Central African Republic and Chad. This has in turn compelled France to get more and more involved militarily in order to preserve its remaining hunting grounds in Africa, in particular by taking an active part in the battles launched against the Sudanese government from Chad.

Since the overthrow of the former dictator Siyad Barre in 1990, which accompanied the fall of his protector, the USSR, Somalia has been in state of chaos, torn apart by a non-stop war between innumerable clans, mafia gangs of killers and pillagers ready to sell their services to the highest bidder, imposing a reign of terror and desolation across the whole country. The Western powers, which descended on this country between 1992 and 1995, have had to fight a losing battle in the face of this chaos and decomposition: the spectacular landing of the US marines ended in a pathetic fiasco in 1994, leaving the way open to total anarchy. The settling of scores between these gangs of assassins has left 500,000 dead since 1991. The Union of Islamic Courts, which is one of these gangs hiding under a veneer of Sharia law and "radical" Islam, finally grabbed hold of the capital Mogadishu in May 2006 with a few thousand armed men. The transitional government exiled to Baidoa then called on its powerful neighbour, Ethiopia, to save the day.3 The Ethiopian army, with the overt support of the US, bombarded the capital, forcing the Islamic troops to flee within a few hours, most of them going to the south of the country. Mogadishu is a frightful ruin whose population has been reduced to living hand to mouth. A new provisional government supported from a discreet distance by the Ethiopian army has been set up but its appeal to the population to hand in its weapons has had no result. After the clear victory of Ethiopia, the truce could only be provisional and precarious because the Islamic "rebels" are in the process of re-arming, in particular through the porous southern border with Kenya. But the rebels may get support from elsewhere, such as Sudan, Eritrea - Ethiopia's traditional rival - and Yemen. This uncertain situation is worrying for the US given that the Horn of Africa, with the military base in Djibouti and Somalia's position on the route to the Middle East and Asia, is one of the most strategic zones in the world. This is what prompted the US to intervene directly on 8 January, bombing the south of the country where the rebels have taken refuge; the White House claimed that they are being directly manipulated by Al Qaida. Neither the US, nor France, nor any other great power can play a stabilising role or act as a barrier to the spread of military barbarism in Africa or any other part of the world, whatever government is in power. On the contrary, their imperialist interests are pushing them to step up the death and destruction in an increasingly uncontrolled manner.

The plunging of a growing part of humanity into this kind of barbarism and chaos is the only future that capitalism can offer. Imperialist war is today mobilising the wealth of science, technology and human labour not to improve humanity's well-being, but to destroy these riches, to accumulate ruins and corpses. Imperialist war, which is undermining the heritage of centuries of human history and threatens to engulf and overwhelm the whole of humanity, is an expression of a profoundly aberrant social system whose survival has become an insane disaster for human society.

More than ever, the only possible hope lies in the overthrow of capitalism, in the establishment of social relations freed from the contradictions which are strangling society, by the only class that can bring humanity a future: the working class.

Wim 10.1.07

1 Another of the region's tyrants, Hafez-el-Assad of Syria, has since his death been dubbed a great statesman in reward for rallying to the Western camp during the period of the blocs, despite a career that was just as bloody as Saddam's.

2 Certain bourgeois writers are quite capable of seeing the unbearable accumulation of barbarism in the world today: "Barbarism follows barbarism to give birth to more barbarism. A video circulates on the internet, the latest contribution to the festival of unspeakable images, from the beheadings carried out by Zarkawi to the humiliated bodies piled up by GI's at Abu Ghraib (...) The terrible secret services of the former tyrant are succeeded by the Interior Ministry's death squads dominated by the pro-Iranian Badr Brigades (...) Whether in the name of Bin Ladenist terrorism, the struggle against the Americans, or the Shi'ite power, the murders directed against the Iraqi civilians have this in common: they are carried out under the law of individual impulse. Scoundrels of all kinds are springing up in the ruins of Iraq. Lying is the norm; the police practise kidnapping and banditry; men of God decapitate and eviscerate; the Shi'ite does to the Sunni what he himself has suffered" (the French weekly Marianne, 6.1.07). But all this is put down to "individual impulses" and in the end to "human nature". What such writers cannot understand is that this barbarism is a historical product of the capitalist system; and that there exists a historic class capable of bringing it to an end: the proletariat.

3 Ethiopia, also a former bastion of the USSR, has become a US stronghold in the region since the fall of Mengistu in 1991.

Recent and ongoing:

- War in Iraq [1]

History of the CNT (1910-13): The birth of revolutionary syndicalism in Spain

- 5529 reads

In continuity with the series on revolutionary syndicalism which we began in International Review n°118 [2] , the article below is the first in a series of articles on the experience of the Spanish CNT.

Today, a new generation of workers are gradually getting involved in the class struggle against capitalism. This confrontation raises a great many questions, one of the most frequent of which is the union question. It is no secret that the workers remain suspicious of the official unions, and the idea of a "revolutionary unionism" continues to hold a certain attraction; the idea, that is, of organising outside the state structure with the aim of unifying the immediate struggle and also the revolutionary struggle.

By examining the experience of the French CGT and the IWW in North America we have shown that this idea is unrealistic and utopian but the example of the CNT shows is even more striking, as we will now see. From the beginning of the 20th century history has repeatedly shown by experience that syndicalism and revolution are contradictory terms that cannot possibly be united.1

The contradictions of Spanish capitalism and the influence of Anarchism

Today, the CNT and anarchism are seen as inseparable. Anarchism, which played a minor part in the great workers' movements of the 19th and 20th centuries,2 presents the CNT as the proof that its ideology is able to build an extensive mass organisation that can play a decisive role in the workers' struggles, as did the Spanish CNT from 1919 to 1936.

However it was not anarchism that created the CNT because at its inception it had a revolutionary syndicalist orientation, although this does not mean that anarchism was completely absent from its foundation or that it did not leave its mark on the development of the organisation.3

As we have already shown in other articles in this series - we will not go back over this here - revolutionary syndicalism is an attempt to respond to new conditions: capitalism was no longer at its zenith and was gradually entering its decadent phase, which was clearly demonstrated by the immense slaughter of the First World War. Confronted with this reality, larger and larger sectors of the working class became aware of the rampant opportunism of the socialist parties - corrupted by parliamentary cretinism and reformism - as well as the bureaucratisation and conservatism of the unions. There were two kinds of reaction to this; on the one hand a revolutionary tendency within the socialist parties (the left formed by those groups whose best known militants were Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Pannekoek, etc) and on the other hand revolutionary syndicalism.

These general historic conditions are equally valid for Spain although they were also marked by the backwardness and the specific conditions of Spanish capitalism. Two of these particularities had a decisive, negative weight on the proletariat of the period.

The first contradiction was the obvious absence of any real economic unity among the various zones of the Iberian peninsula. This produced localist and regionalist dispersion which gave rise to a series of uprisings within the various regions, the most important of which was the republican cantonal insurrection of 1873. Because of its federalist positions anarchism proved a suitable representative of these archaic historic conditions: the autonomy of each region or zone, which declared itself sovereign and only accepted the fragile and random union of the "solidarity pact". As Peirats4 says in his work, The CNT in the Spanish revolution, "this programme, that of Bakunin's Alliance, suited the temperament of the Spanish underprivileged very well. The federal vision introduced by the Bakuninists was like rain upon damp soil because it resurrected memories of local rights, of village charters and the free municipalities of the Middle Ages" (page 3, volume 1).5

Given the general backwardness and the explosive differences in economic development of the various regions, the bourgeois state, although constitutional in form, in fact depended on the brute force of the army to ensure social cohesion. It unleashed periodic repression mainly against the proletariat and, to a lesser extent, against the middle classes in the towns. Not only the workers and the peasants, but also wide sections of the petty bourgeoisie, felt completely excluded from a state that was liberal in theory but violently repressive and authoritarian in practice and which was controlled by bosses who ignored the parliamentary system and its policies. This gave rise to a visceral apoliticism that was expressed in anarchism but which was also very strong within the working class. These general conditions resulted in the weakness of the Marxist tradition in Spain on the one hand and the strong influence of anarchism on the other. The group around Pablo Inglesias6 remained faithful to the Marxist current in the IWA and formed the Socialist Party in 1881.7 However the organisation was always extremely weak politically, to the point that Munis8 said that many of its leaders had never read anything by Marx: "The most fundamental and important works of theory had not been translated. And the few that had been published (the Communist Manifesto, Anti-Dühring, Misery of Philosophy, Utopian and Scientific Socialism) were read more by bourgeois intellectuals than by the socialists" (Signposts to Defeat, Promise of Victory, p59).9 This is why the party moved so rapidly towards opportunism and was one of the most right wing parties of the whole Second International.

As regards the anarchist tendency, it would take a detailed study to understand all its various currents and the many positions contained within it. We would also have to distinguish the majority of militants sincerely committed to the proletarian cause and those who passed themselves off as their leaders. In general, the latter, apart from a few honest ones, betrayed at every step those "principles" that they ostensibly defended. We need do no more than recall the shameful actions of Bakunin's followers in Spain at the time of the cantonal insurrection of 1873, which Engels denounced so brilliantly in his pamphlet, The Bakuninists at work: "The same people who rejected the Hague resolution on the political attitude of the working class and who trampled under foot the Rules of the [International Working Men's] Association, thus bringing division, conflict and confusion into the Spanish Section of the International; the same people who had the effrontery to depict us to the workers as ambitious place-hunters, who, under the pretext of establishing the rule of the working class, sought to establish their own rule; the same people who call themselves autonomists, anarchist revolutionaries, etc., have on this occasion flung themselves into politics, bourgeois politics of the worst kind. They have worked, not to give political power to the working class -- on the contrary this idea is repugnant to them -- but to help to power a bourgeois faction of adventurers, ambitious men and place-hunters who call themselves Intransigent (irreconcilable) Republicans."10

After this episode and in the context of the international reflux of struggles that followed the defeat of the Paris Commune, the Spanish bourgeoisie unleashed a violent repression which lasted many years. In the face of state terror and its own ideological confusion, the anarchist current had only two inalienable certainties: federalism and apoliticism. These certainties aside, it constantly came up against a dilemma: should it carry forward an open struggle in order to create a mass organisation? Or should it carry out minority and clandestine actions on the basis of the anarchist slogan "the propaganda of the deed"? This dilemma plunged the movement into complete paralysis. In Andalusia this oscillating sometimes took the form of a "general strike" in the form of local, isolated uprisings which were easily crushed by the Guardia Civil and were followed by brutal repression. At other times it was expressed in "exemplary actions" (setting fire to crops, plundering farms, etc) which the government exploited to unleash new waves of repression.11

1900 - 1910: the international tendency towards the mass strike

The CNT was born in Barcelona, the main industrial concentration in Spain, on the basis of the historic conditions which existed internationally during the early decades of the 20th century. As we have shown elsewhere,12 the workers' struggle was tending to develop into the revolutionary mass strike, the most advanced example of which was to be seen in the 1905 Russian Revolution.

In Spain also, the change in historical period was expressed in new forms of workers' struggle. Two episodes, which we will describe briefly, illustrate this tendency: the 1902 strike in Barcelona and the Tragic Week of 1909, which also took place in Barcelona.

The former started in December 1901 with the engineering workers demanding the 9-hour day. When they were confronted with repression and the outright refusal of the bosses, the solidarity of the Barcelona proletariat spilled onto the streets. They arose massively and spontaneously at the end of January 1902 without the least encouragement from any union or political organisations. For several days, mass meetings united workers of all trades. However, as there was no echo in the rest of the country, the strike got progressively weaker. There were various factors that contributed to this situation. On the one hand the open sabotage of the Socialist Party, which even went so far as to block the solidarity funds from the British trade unions. On the other hand, there was the passivity of the anarchist societies.13 At the same time the Workers' Federation of the Spanish Region, which had been newly formed (1900) on an "apolitical" basis,14 was also absent and defended this by saying that "the metal workers of Barcelona have never belonged to any political or social grouping and were not disposed to collective action"15 This experience shook the existing workers' organisations profoundly because it did not follow the traditional "schema" of the struggle: it was neither a general strike according to the anarchist conception nor actions intended to put pressure on employers within a strictly trade and economic framework, in accordance with the vision of the Socialists.

The Tragic Week of 1909 came about as a massive popular reaction against the embarkation of troops for Morocco.16 In this movement too we see expressed active class solidarity, the extension of the struggles and the demonstrators taking

possession of the streets. All of this was done on the immediate initiative of the workers without any previous planning or calls from the political organisations. The economic struggle and the political struggle were united. There were two aspects; firstly there was the solidarity of all sectors of workers with the strikers in the textile industry, the most important in Catalonia. Secondly, the refusal of imperialist war was expressed by the mobilisation against the embarkation of soldiers for the war in Morocco. Under the destructive influence of bourgeois republicanism, led by the famous demagogue Lerroux,17 the movement degenerated into violent and sterile actions, the most spectacular of which were the setting fire to churches and convents. The government made use of all this to unleash another wave of repression, which took a particularly barbaric and sadistic form.

This was the situation in 1907 which saw the birth of Workers' Solidarity (which would become the CNT three years later). Workers' Solidarity united five tendencies that were present in the workers' milieu:

- "pure" trade unionism, which was very radical, but apolitical and corporatist;

- the Catalan socialists, who acted independently of the rigid and schematic directives from the centre in Madrid;

- the revolutionary syndicalists, a tendency recently emerged from the socialist unions, though influenced by anarchism;18

- the anarchists who, in Catalonia, participated in union action;

- finally, the members of the demagogic republican party of Lerroux, cited above.

The predominant concern was to form a single, unitary organisation which would weld together the entire class for struggle.

During this period, the theories of French revolutionary socialism were widely circulated. Anselmo Lorenzo, a prominent Spanish anarchist , had translated the The Union by Emile Pouget in 1904; José Prat translated and distributed other works, those by Pouget, Pelloutier and Pataud19 for example. In his own work The Bourgeoisie and the Proletariat (1908), Prat summarised revolutionary syndicalism by saying that it "in no way accepts the present order; it suffers it in the hope that union power can destroy it. By means of increasingly generalised strikes it gradually revolutionises the working class and moves towards the general strike. It snatches from the bourgeois bosses all the immediate improvements that are positive but its aim is the complete transformation of the present society into a socialist society. Through its action as a political agent it brings about economic and socialist revolution."

The founding of the CNT at the 1910 Congress

Workers' Solidarity had intended to hold its Congress at the end of September 1909 in Barcelona. However the congress could not take place because of the events of the Tragic Week and the repression that followed it. The First Congress of the CNT was therefore put off until 1910.

This organisation, that has been presented ever since as the model of anarcho-syndicalism, was in fact founded on the basis of revolutionary syndicalist positions: "there was not the slightest reference to anarchism, either as an aim or a basis for action or in terms of principles, etc. Moreover during the Congress the discussions, the resolutions and the Manifestos of the Confederation made not the slightest allusion to the theme of anarchism in a way that would suggest that there was a preponderant weight of this political current or at least that it had a certain influence on the new Confederation. It came across as a completely neutral organ, if the exclusive practice of revolutionary syndicalism can be understood in this way. It was apolitical in the sense that it did not participate in the game of politics or in the process of the government of society. However it was political in the sense that it proposed to replace the present system of social government by a different system based on its own union organisation." (A. Bar, The CNT in the red years).20

Nevertheless, it would of course be wrong to think that the CNT was not influenced by anarchist positions. This can be seen in the three pillars of revolutionary syndicalism that we have examined in the previous articles in this series that analysed the experience of the French CGT and the American IWW: apoliticism, direct action and centralism.

Apoliticism

As we have seen in our previous articles, revolutionary syndicalism claims above all to be "sufficient unto itself": the union should provide the working class with its unitary organ of struggle, the means of organising future society, and even the framework for its theory, although the latter was generally under-estimated. Political organisations were often considered not so much as dangerous as useless. In France, this current nonetheless produced theoretical thinking and writing, thanks to which, for example, its positions reached Spain. But in Spain itself, revolutionary syndicalism remained entirely "practical"; it produced practically no theoretical work and its most important documents were the resolutions adopted at the Congress, in which the level of discussion was very limited. "Spanish revolutionary syndicalism was faithful to one of the basic principles of syndicalism: to be a means of action, a practice and not just a theory. For this reason, contrary to what happened in France, it is very unusual to find theoretical works from Spanish revolutionary syndicalism... The clearest declarations of revolutionary syndicalism are in fact the documents of the organisations, the manifestoes and agreements of Workers' Solidarity as well as of the CNT." (A. Bar, ibid)

It is remarkable that the Congress did not devote a single session to the international situation or to the problem of war. It is even more significant that there was no discussion around the recent events during the Tragic Week which encapsulated a multitude of burning issues (war, direct solidarity in the struggle, the extremely negative role of Lerroux's republicanism).21 From this we can draw the conclusion that there was a reluctance to analyse the conditions of the class struggle and the historic period, difficulty in carrying out theoretical reflection and consequently in drawing the lessons of the experience of the struggle. Instead there was a whole session devoted to a confused and interminable debate on how to interpret the phrase "the emancipation of the workers must be the task of the workers themselves". This ended up with the declaration that only manual workers could carry out this struggle and that intellectual workers must be kept to one side and accepted only as "collaborators".

Direct action

This was considered by the majority of workers to be the main difference in practice between the new organisation, the CNT, and the socialist UGT. In fact we can say that this was the very basis of the constitution of the CNT as a national union (no longer restricted to Catalonia). "The initiative to transform Workers' Solidarity into a Spanish Confederation did not come from the Confederation itself but from numerous entities outside Catalonia. The latter were motivated by the desire to unite with the societies which had not belonged to the General Workers' Union up to then and were interested in the means offered by the direct struggle" (José Negre, quoted by A. Bar in the work quoted above).

Many regroupments of workers in other regions of Spain had had enough of the reformist cretinism of the UGT, of its bureaucratic rigidity and its "quietism" - as many critical socialists recognised. So they greeted with enthusiasm the new workers' union which advocated direct mass struggle and a revolutionary perspective, even if this remained pretty vague. However there is one misunderstanding that ought to be cleared up: direct action is not the same thing as the mass strike. Struggles that break out without the workers having been called out but as a result of a subterranean maturation; general assemblies in which the workers reflect and decide together; massive street demonstrations; the organisation taken in hand directly by the workers without waiting for directives from the leaders: these characterise the workers' struggle in the historic period of capitalist decadence. But they have nothing whatever to do with direct action, by which groups constituted spontaneously by affinity carry out minority actions of "expropriation" or of "propaganda by the deed". The methods of the mass strike spring from the collective and independent action of the workers whereas the methods of direct action depend on the "sovereign will" of small groups of individuals. Enormous confusion has been caused by the amalgamation of "direct action" and the new methods of struggle developed by the class such as in 1905 in Russia or those of Barcelona in 1902 and 1909, that we have mentioned above.This confusion has dogged the CNT throughout its history.

This confusion was expressed in sterile debate between those for and those against the "general strike". The members of the PSOE were against the general strike, seeing in it the abstract and voluntarist attitude of anarchism which throws itself into this or that struggle in order to "transform it arbitrarily into revolution". They were no more capable than their colleagues in Europe's other socialist parties of understanding that the change in historic conditions meant that the Revolution was no longer a distant ideal, it had become the main axis around which must be united all efforts as regards the struggle and class consciousness.22 Rejecting the anarchists' "sublime, great and majestic Revolution", they remained equally ignorant of the concrete changes in the historic situation.

On the other hand, the revolutionary syndicalists wanted sincerely to take the struggle in hand, to develop assemblies and massive struggles but they dressed this up in the old clothes of the general strike, completely dependent on the unions. Although the theses of "direct action" and the "general strike" seemed very radical they were of necessity limited to the economic terrain and so took the form of a more or less radical union economism. It did not express the depth of the struggle, on the contrary it expressed its limitations: "The Confederation and the sections integrated into it must always fight on a purely economic terrain, that is on the terrain of direct action" (CNT Statutes).

Centralism

A large part of the discussion at the Congress was devoted to the organisational question: how should a national union be structured? The rejection of centralisation and extreme federalism meant that the anarchist position prevailed on this point. So in the early period of its existence (up until the 1919 congress) the CNT adopted a structure that was completely anachronistic, formed of a juxtaposition of trade based societies on the one hand and of local federations on the other.

The events in Russia in 1905 proved that the unity of the working class was a revolutionary social force which organised in a centralised fashion. The Petersburg soviet regrouped workers regardless of sector or category and was also open to the intervention of revolutionary groups. Unfortunately the CNT passed motions that went in quite the opposite direction.

On the one hand, influenced by federalism, in response to the extreme misery and hateful brutality of the capitalist regime local groups threw themselves periodically into insurrections that resulted in the declaration of libertarian communism in one locality. These met with brutal repression from bourgeois forces. In the five years preceding the First World War, this happened frequently in Andalucia and also in regions such as Valencia, where agriculture was more developed. One well-known example is the movement that broke out in 1912 in Cullera, a wealthy farming and industrial centre: a movement of day labourers took over the local council building and declared "libertarian communism" in the region. Completely isolated, they were brutally suppressed by the armed forces and the Guardia Civil together.

On the other hand whole groupsof workers were embroiled in corporatism.23 The method of the latter is to model the workers' organisation on the myriad of subdivisions and complexity of the capitalist organisation of production . The effect of this is to develop among the workers a narrow mindedness of the "every man is master in his own house" type. For corporatism, unity is not the unity of all workers, irrespective of trade, industry, or company, in a single and unique collective but the formation of a "pact for solidarity and mutual defence" between independent and sovereign parts of the working class. This vision is expressed in the rules adopted by the Congress which went so far as to accept the existence of two distinct societies for the same trade in the same locality.

Conclusion

One highly significant theme ran through the 1910 Congress. The very day that it began the workers of Sabadell (an industrial area near Barcelona) were engaged in a generalised strike in solidarity with their comrades of Seydoux, who had suffered several disciplinary sackings. The strikers sent delegates to the Congress to ask that it call for a general strike in solidarity. The Congress showed great enthusiasm and sympathy. However it adopted a resolution based on outworn union ideas that were increasingly being overtaken by the fresh wind of the mass workers' struggle: "We propose to the Congress that it adopt as a measure of solidarity with the strikers of Sabadell that all delegates here present encourage their respective entities to perform their solemn duty. That is, that they carry out the decisions of the delegate assemblies of Workers' Solidarity of Barcelona by materially aiding the strikers." This confused and hesitant motion was a real cold shower for the workers of Sabadell and they ended up by going back to work completely defeated.

This episode symbolises the contradiction which was to mark the evolution of the CNT in the period to come. It held the heart of an impetuous proletarian life beating within it, one that wanted to respond to the increasingly explosive situation within which capitalism was locked. However, by the way it responded, revolutionary syndicalism, was shown to be increasingly inadequate and counterproductive and would, in the end, be a hindrance rather than a help.

We will examine this question in the next article, in which we will analyse the action of the CNT in the difficult period of 1914-1923: the CNT faced with war and revolution.

RR and CMir (15th June 2006)

1 CGT - Confédération Générale du Travail, CNT - Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, IWW - International Workers of the World.

2 Its influence was very limited during the Paris Commune and its presence was insignificant in 1905 and 1917 in Russia, as it was in Germany 1918-23.

3 The preface to a book on the proceedings of the Constituent Congress of the CNT (Editorial Anagramme 1976) acknowledges that the CNT "was neither anarcho-collectivist nor anarcho-communist and not even completely revolutionary syndicalist but was rather apolitical and federalist."

4 Among anarchist historians Peirats is one of the best known and is widely recognised for his rigour. The work referred to is considered to be a point of reference in the Spanish anarchist milieu.

5 On the next page, Peirats develops the following idea: "in contrast to the unitary spirit, which is the reflection of a unified landscape - that of the meseta - the borders of the peninsula , with their mountain chains, their valleys and plains form a circle of compartments which house an infinite variety of peoples, languages and traditions. Every zone or nook of this uneven landscape is a sovereign entity, jealous of its institutions, proud of its freedom. This is the birthplace of Spanish federalism. This geographic configuration was always a seedbed of abutting autonomous zones, some of which were separatist, a retort to the absolutism of the East (...) Between separatism and absolutism, federalism lost its way. The latter is based on the free and voluntary connection of all the autonomous units; from individuals to natural regions or those with affinitary links and including free districts. The warm welcome that was accorded in Spain to certain ideological influences coming from abroad by no means contradicts the existence of a home grown federalism that was scarcely mitigated by centuries of extortion. It rather confirms it. (...) The Bakuninist ambassadors sowed their federalist seed - libertarianism - among the Spanish working class" (ibid, p18). Through associated labour at an international level, the working class represents the conscious unification - freely undertaken - of the whole of humanity. This is radically opposed to federalism which is an ideology that reflects dispersion, the fragmentation of the petty bourgeoisie and of the archaic modes of production that preceded capitalism.

6 Pablo Iglesias (1850-1925) founder and leader of the PSOE until his death.

7 IWA - International Workingmen's Association (the First International), PSOE - Partido Socialista Obrero Español.

8 Spanish revolutionary (1911-1989). He came from Trotsky's Left Opposition but broke with it when it capitulated by participating in the Second World War, and continued to defend class positions against the Trotskyists. Founder of the group FOR (Fomento Obrero Revolucionario). See our article in the International Review n°58, "In memory of Munis, a militant of the working class".

9 See our commentary on this book in our Spanish language brochure: "1936: Franco and the Republic massacre the workers"

10 See Archive of Marxist authors: 'The Bakuninists at Work [3]'.

11 In 1882-1883, the state unleashed ferocious repression against day labourers and anarchists under the pretext that it was fighting against a society that organised such attacks; La Mano Negra. The existence of this society has never been proved.

12 See our series on the 1905 revolution beginning in the International Review n°120.

13 The openly anarchist historian, Francisco Olaya Morales makes the following statement in his book History of the Spanish Workers' Movement (1900-1936): "at the end of December, the strike committee contacted some anarchist societies but they refused to join the committee on the grounds that it had transgressed the rule of direct action" (sic) (page 54).

14 We will come back to this experience latter.

15 See Olaya's book referred to in a previous note, p54.

16 Spanish capital was engaged in a costly war in Morocco in defence of its imperialist interests (to take possession of a number of colonial zones by picking up the remains left by the big powers). This war made it necessary to send a continuous supply of troops, so sacrificing a large number of workers and peasants. Many young men knew that being sent to Morocco meant, not only that they would have to suffer the misery of life in the barracks, but also that they would die or be invalids for the rest of their lives.

17 A dubious individual and an adventurer, founder of the radical party, which was important in Spanish politics until the 1930s.

18 Unlike the French experience (see the articles from this series in International Review n°118 and 120), or that of the IWW in the USA (see n°124 and 125 of the Review), in Spain no revolutionary syndicalist tendency found a clear expression in written works or even in articles. It was made up of trades unions which had broken from the Socialist Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), and some anarchists like José Prat (of whom more later) who were more open to the different tendencies existing in the workers' movement.

19 Theoreticians of French revolutionary syndicalism. See the articles in this series previously referred to.

20 When the anarchist historian, Francisco Olaya Morales, talks about the period of the CNT's founding in his book History of the Spanish Workers' Movement (1900-1936), he says clearly (p277 onwards) that the socialists participated in the founding and in the early life of the CNT. He quotes José Prat, an anarchist author although independent (mentioned above) who was in favour of this participation.

21 There was only a brief mention in passing about the painful problem of the number of prisoners.

22 This is the problem that Rosa Luxemburg clarified in this period, when she examined the huge mass strike of 1905: "On the other hand, the incessant economic war waged by the workers against capital keeps combative energy on the alert even in times of political calm. It constitutes a sort of permanent reservoir of energy from which the political struggle continually draws fresh forces. At the same time the tireless work of chipping away for reforms unleashes here or there sharp conflicts from which political struggles suddenly burst forth. In brief, the economic struggle provides a continuity, it is the thread that ties together the various political knots; the political struggle is a periodic fertilisation that prepares the soil for the economic struggles. Cause and effect succeed one another and alternate constantly. So, in a period of mass strike, the economic factor and the political factor, far from being completely distinct or even mutually exclusive, as the schema of the pedants affirms, represent two complementary aspects of the proletarian class struggle in Russia." (Mass strike, party and unions)

23 The following example illustrates the weight of corporatism. In 1915 the Federation Committee of Reus, an industrial zone near Tarragona - dominated by the socialists - signed an agreement with the bosses behind the backs of the striking workers which resulted in the defeat of the latter. The petitions that the workers circulated, asking that the Committee campaign for a general solidarity strike, were buried. The Committee, which was dominated by men, was suspicious of the demands of the women and gave preference to the interests of the sector - the engineering workers - that the majority of them came from. They did so to the detriment of the basic interests of the working class as a whole, which lay in expressing an indispensable solidarity with the female comrades in struggle.

Deepen:

History of the workers' movement:

- 1936 - Spain [5]

Political currents and reference:

Profit rates and capitalist decadence - reply to the CWO

- 4687 reads

In the first part of his article, we saw that, contrary to what is often asserted, it is not the mechanism of the tendency towards the fall in the rate of profit which is at the heart of Marx's analysis of the economic contradictions of the capitalist system, but the fetter that the wage labour relationship places upon the ultimate demand of society: "The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses, in the face of the drive of capitalist production to develop the productive forces as if only the absolute consumption capacity of society set a limit to them" (Marx, Capital, Vol 3, Chapter 30: "Money capital and real capital: 1", p615). [1] This is the consequence of the subordination of the world to the dictatorship of wage labour, which enables the bourgeoisie to appropriate a maximum of surplus labour. But as Marx explains, the frenetic production of commodities engendered by the exploitation of the workers gives rise to a piling up of products which grows more rapidly than the solvent demand of society as a whole: "When considering the production process we saw that the whole aim of capitalist production is appropriation of the greatest possible amount of surplus-labour ... in short, large-scale production, i.e., mass production. It is thus in the nature of capitalist production, to produce without regard to the limits of the market." [2] This contradiction periodically provokes a phenomenon hitherto unknown in the whole history of humanity: the crises of overproduction: "an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity - the epidemic of over-production."[3] "The immense but intermittent elasticity of the factory system, combined with its dependency on the universal market, necessarily gives birth to feverish production, followed by a glut on the markets, whose contraction then leads to paralysis. The life of industry is thus transformed into a series of periods of average activity, prosperity, overproduction, crisis, and stagnation".[4]

More precisely, Marx situates this contradiction between the tendency towards the frenetic development of the productive forces and the limitations to the growth of society's ultimate consuming power given the relative impoverishment of the wage labourers: "To each capitalist, the total mass of all workers, with the exception of his own workers, appear not as workers, but as consumers, possessors of exchange values (wages), money, which they exchange for his commodity."[5] Now, following Marx, "the consumer power of society is not determined either by the absolute productive power, or by the absolute consumer power, but by the consumer power based on antagonistic conditions of distribution,[6] which reduce the consumption of the bulk of society to a minimum varying within more or less narrow limits."[7] It thus follows that "Over-production is specifically conditioned by the general law of the production of capital: to produce to the limit set by the productive forces, that is to say, to exploit the maximum amount of labour with the given amount of capital, without any consideration for the actual limits of the market or the needs backed by the ability to pay"[8] This is the heart of the marxist analysis of the economic contradictions of capitalism: the system must ceaselessly increase production while consumption cannot, within the present class structure, follow an identical rhythm.

In the first part of our article, we also saw that, in its internal mechanism, the tendency for the rate of profit to fall could well run alongside the emergence of crises of overproduction. Indeed, this idea appears in many places in Marx's work, for example in the chapter of Capital on the internal contradictions of the law of the falling rate of profit: "Over-production of capital is never anything more than overproduction of means of production (...) a fall in the intensity of exploitation below a certain point, however, calls forth disturbances, and stoppages in the capitalist production process, crises, and destruction of capital."[9] However, for Marx it was neither the exclusive nor even the main cause of the contradictions of capitalism. Furthermore, in the Preface to the 1886 English edition of Book 1 of Capital, when Engels is summarising Marx's conception, he does not refer to the tendency for the rate of profit to fall but to the contradiction which Marx constantly underlined between "the absolute development of the productive forces" and "the limitations on the growth of society's ultimate consuming power": "While the productive power increases in a geometric, the extension of markets proceeds at best in an arithmetic ratio. The decennial cycle of stagnation, prosperity, over-production and crisis, ever recurrent from 1825 to 1867, seems indeed to have run its course; but only to land us in the slough of despond of a permanent and chronic depression".[10]

Thus, as we will show, and as will be clear to anyone who approaches this question in a serious and honest way, the CWO[11] defends, on the question of the fundamental causes of the economic crises of capitalism and of the decadence of this mode of production, a different analysis from the one defended in their day by Marx and Engels. They have every right to do so, and even the responsibility to do so if they consider it necessary. Whatever the depth and value of his contribution to the theory of the proletariat, Marx was not infallible and his writings should not be seen as sacred texts. The writings of Marx must also be subjected to a critique by the marxist method. This is the approach that Rosa Luxemburg adopts in The Accumulation of Capital (1913) when she brings to light the contradictions in Volume II of Capital with regard to the schemas of enlarged reproduction. This said, when you put a part of Marx's work into question, political and scientific honesty demands that you openly and explicitly take responsibility for such an approach. This is exactly what Rosa Luxemburg did in her book and it was this which provoked such hostility among the "orthodox marxists" who were so scandalised by anyone putting Marx's writings into question. Unfortunately this is not what the CWO does when it moves away from Marx's analysis while claiming to remain loyal to it, and at the same time accusing the ICC of distancing itself from materialism and thus from marxism. For our part, if we take up Marx's analyses here, it is because we consider them to be correct and because they take into account the reality of capitalism.

Thus, having examined this question on the theoretical level in the first part of this article, we are going to show how empirical reality totally invalidates the theory of those who make the evolution of the rate of profit the alpha and omega of the explanation of crises, wars and decadence. To do this, we will continue to base ourselves on the critique of Paul Mattick's analysis adopted by the IBRP, which argues that on the eve of World War I the economic crisis had reached such proportions that it could no longer be resolved through the classic means of devalorising fixed capital (i.e. bankruptcies) as it had during the 19th century, but now demanded the physical destruction that comes with war: "Under 19th century conditions it was relatively easy to overcome over-accumulation by means of crises that more or less affected all capital entities on an international scale. But at the turn of the century a point had been reached where the destruction of capital through crisis and competition was no longer sufficient to change the total capital structure towards a greater profitability. The business cycle as an instrument of accumulation had apparently come to an end; or rather, the business cycle became a cycle of world wars. Although this situation may be explained politically it was also a consequence of the capitalist accumulation process (...) The resumption of the accumulation process in the wake of a ‘strictly' economic crisis increases the general scale of production. War, too, results in the revival and increase of economic activity. In either case capital emerges more concentrated and more centralised. And this both in spite and because of the destruction of capital." (Paul Mattick as quoted in the article in Revolutionary Perspectives n°37).[12]

This is the IBRP's analysis of capitalism's entry into its phase of decadence. On this basis, the latter accuses us of idealism because we do not advance a clearly economic analysis to explain every phenomenon in society and decadence in particular: "In the materialist concept of history the social process as a whole is determined by the economic process. The contradictions of material life determine the ideological life. The ICC is asserting, in the most casual way, that an entire period of capitalism's history has ended and another has opened up. Such a major change could not occur without a fundamental change in the capitalist infrastructure. The ICC must either support its assertions with an analysis from the sphere of production or admit that they are pure conjecture." (Revolutionary Perspectives n°37). This is what we are now going to discuss.

Historical materialism and a mode of production's entry into decadence

In the belief that it is making good use of the marxist method, the IBRP has found, in the councilist Paul Mattick, the "material bases" for the opening up of capitalism's period of decadence. Unfortunately for the IBRP, if the marxist method - historical and dialectical materialism - could be summed up as looking for an economic explanation for every single phenomenon in capitalism, then, as Engels said, "the application of the theory to any period of history would be easier than the solution of a simple equation of the first degree."[13]. What the IBRP quite simply forgets here is that marxism is not just a materialist method of analysis but also a historical and dialectical one. So what does history tell us about a mode of production's entry into decadence on the economic level?

History tells us that no period of decadence has begun with an economic crisis! There is nothing surprising in this because a system at its apogee is in its period of greatest prosperity. The first manifestations of decadence can therefore only appear in a very weak manner at this level; they appear above all in other areas and on other levels. Thus, for example, before plunging into endless crises on the material level, Roman decadence first of all expressed itself in the halting of its geographical expansion in the second century AD, by the first military defeats at the edges of the Roman empire during the third century, as well as by the first simultaneous outbreak of slave revolts all over the colonies. Similarly, before getting stuck in economic crises, famines, plague and the Hundred Years War, the first signs of the decadence of the feudal mode of production appeared in the end of the land clearances for new estates in the last third of the 13th century.

In both these cases, economic crises as products of blockages in the substructure only developed well after the entry into decadence. The passage from ascendance to decadence of a mode of production on the economic level can be compared to the changing of the tides: at its highest point, the sea seems to be at its most powerful and its retreat is almost imperceptible. But when contradictions in the economic underpinnings begin to gnaw away at society at a deep level, it is the superstructural manifestations which appear first.

The same goes for capitalism: before appearing on the economic and quantitative level, decadence found expression as a qualitative phenomenon at the social, political and ideological level, through the exacerbation of conflicts within the ruling class, leading to the First World War, by the state taking control of the economy for the needs of war, through the betrayal of social democracy and the passing of the unions into the camp of capital, through the eruption of a proletariat that demonstrated its capacity to overthrow the domination of the bourgeoisie and through the introduction of the first measures aimed at the social containment of the working class.

It is thus quite logical and fully coherent with historical materialism that capitalism's entry into decadence did not express itself first of all through an economic crisis. The events which took place at this point did not yet fully express all the characteristics of its phase of decadence; they were an exacerbation of the dynamics that belonged to its ascendant period, in a context which was in the process of profound modification. It was only later on, when the blockages at the substructural level had done their work, that the economic crises now began to fully unfold. The causes of decadence and of the First World War are not to be found in a certain rate of profit or an economic crisis that was nowhere to be seen in 1913 (see below) but in a totality of economic and political causes, as explained in International Review n°67.[14] The prosperity of capitalism during the Belle Epoque was fully recognised by the revolutionary movement at the time of the Communist International (1919-28). At its First Congress, in the Report on the World Situation written by Trotsky, the CI noted that "the two decades preceding the war were a period of particularly powerful capitalist growth".

An empirical invalidation of the thesis of Mattick and the IBRP

This theoretical and empirical observation drawn from the evolution of past modes of production is fully confirmed by capitalism. Whether we examine the rate of growth, the rate of profit, or other economic parameters, there is no confirmation of the theory of Mattick and the IBRP, according to which capitalism's entry into its phase of decadence and the outbreak of the First World War was the product of an economic crisis following a fall in the rate of profit, necessitating a massive devalorisation of capital through the destruction caused by war.

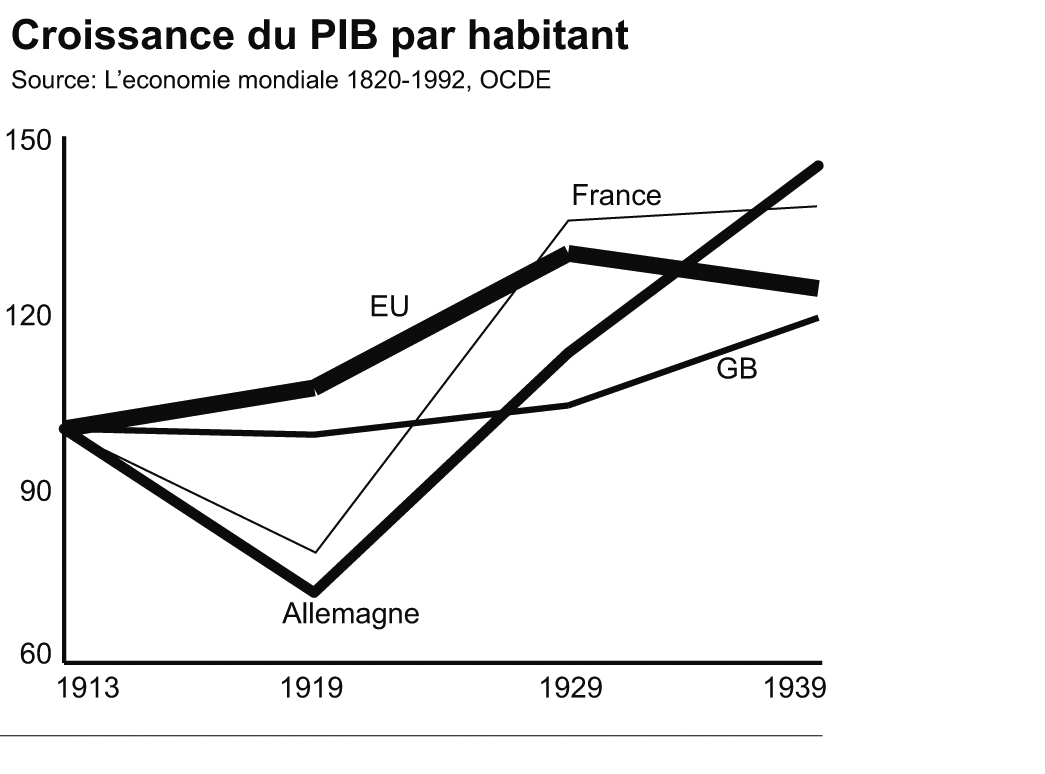

The growth-rate of GNP, measured in volume by inhabitant (thus with inflation deducted) was on the rise throughout the ascendant period of capitalism, reaching a culminating point on the eve of 1914. All the figures we publish below show that the period leading up to the First World War was the most prosperous in the whole history of capitalism up to that point. This observation remains constant regardless of what indicators we use:

|

Growth in Gross World Product per inhabitant |

|

|

1800-1830 |

0,1 |

|

1830-1870 |

0,4 |

|

1870-1880 |

0,5 |

|

1880-1890 |

0,8 |

|

1890-1900 |

1,2 |

|

1900-1913 |

1,5 |

|

Source : Paul Bairoch, Mythes et paradoxes de l'histoire économique, 1994, éditions la découverte, p.21. |

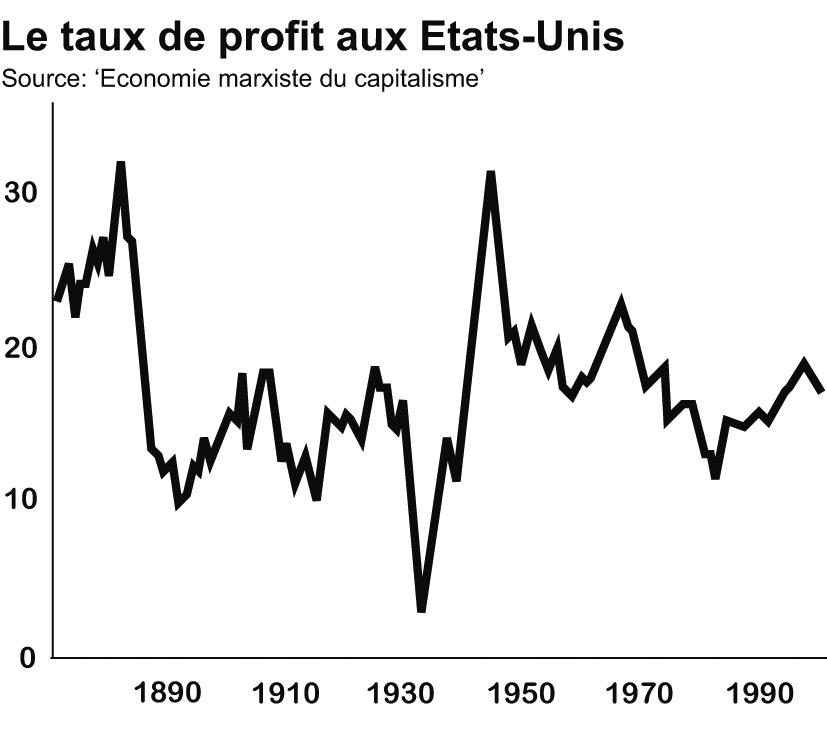

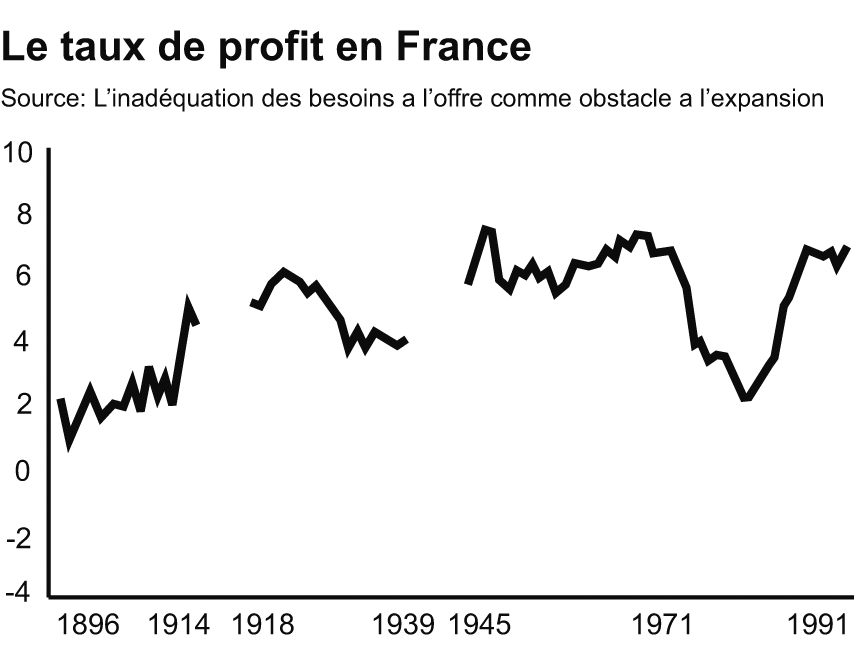

The same is true if we examine the evolution of the rate of profit, which is the variable taken into account by all those who make this question the key to understanding all the economic laws of capitalism. The graphs for the USA and France which we reproduce below also show that there is no confirmation of the theory of Mattick and the IBRP. In France, neither the level, nor the evolution of the rate of profit can in any way explain the outbreak of the First World War since the rate had been on the rise since 1896 and had been rising even more sharply from 1910 on! Nor can the rate of profit explain the USA's entry into the 1914-18 war: oscillating around 15% since 1895, it was on the rise after 1914 and reached 16% at the time the US entered the war in March-April 1917! Neither the level, nor the rate of profit on the eve of the First World War are able to explain the outbreak of the war or capitalism's entry into its phase of decadence.

|

|

Production industrielle mondiale |

Commerce mondial |

|

1786-1820 |

2,48 |

0,88 |

|

1820-1840 |

2,92 |

2,81 |

|

1840-1870 |

3,28 |

5,07 |

|

1870-1894 |

3,27 |

3,10 |

|

1894-1913 |

4,65 |

3,74 |

|

Source : W.W. Rostow, The world economy, history and prospect, 1978, University of Texas Press. |

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that the first perceptible economic signs of a turning point between ascendance and decadence did begin to emerge at this time: not at the level of the evolution of the rate of profit as Mattick and the IBRP wrongly claim, but at the level of a lack of final demand, with the appearance of the premises of a saturation of markets relative to the needs of accumulation on a world scale, as had been predicted by Engels and Rosa Luxemburg (see the first part of this article). This was also noted by the same report by the Third International cited above, which goes on to say "Having tested out the world market through their trusts, cartels and consortiums, the rulers of the world' destiny took into account that this mad growth of capitalism must run up against the limits of the world market's capacity". Thus, in the USA, after a vigorous growth over 20 years (1890-1910), during which the index of industrial activity multiplied by 2.5, the latter began to stagnate between 1910 and 1914 and only picked up in 1915 thanks to the export of military equipment to Europe. Not only did the American economy lose its dynamism on the eve of 1914, but Europe also experienced certain conjunctural difficulties linked to the limitations of world demand, and tried, more and more vainly, to turn towards external markets: "But, under the influence of the crisis that was developing in Europe, the following year (1912) saw a reversal of the conjuncture (in the USA)....Germany then went through a period of accelerated expansion. In 1913 industrial production was 32% above the 1908 level... With the internal market being incapable of absorbing such a level of production, industry turned towards external markets, with exports rising by 60% as against 41% for imports... the turn-around took place at the beginning of 1913... unemployment began to develop in 1914. The depression was mild and short-lived: a temporary recovery began in the spring of 1914. The crisis, having begun in Germany, then spread to the UK... the repercussions of the German crisis were felt in France in August 1913...In the US, it was not until the beginning of 1915 that production began to develop under the influence of war demand" (all these figures, as well as this passage, are taken from the Les crises économiques, PUF no.1295, 1993, p42-48).

These conjunctural difficulties developing on the eve of 1914 were so many precursors of what would become a permanent economic difficulty for decadent capitalism: a structural lack of solvent markets. However, it has to be said that the First World War broke out in a general climate of prosperity and not of crisis, i.e., of a continuation of the Belle Epoque: "The last years of the pre-war period, like the years 1900-1910, were particularly good ones for the three great powers who participated in the war (France, Germany and Britain). From the point of view of economic growth, the years 1909 to 1913 without doubt represented the four best years in their history. Apart from France where the year 1913 was marked by a slow-down in growth, this year was one of the best years of the century, with an annual growth rate of 4.5% in Germany, 3.4% in Britain, with France at a mere 0.6%. The bad results in France can be entirely explained by the 3.1% fall in agricultural production."[15]The war thus broke out before the beginning of a real economic crisis, almost as if the latter had been anticipated; indeed this was noted in the above-cited report from the First CI Congress: "...they tried to find a way out of this situation by a surgical method. The sanguinary crisis of the World War was intended to supersede an indefinitely long period of economic depression". This is why all the revolutionaries of the time, from Lenin to Rosa Luxemburg via Trotsky and Pannekoek, while pointing to the economic factor among the causes of the outbreak of the First World War, did not describe it as an economic crisis or a fall in the rate of profit but as the exacerbation of the previous imperialist tendencies: the continuation of the imperialist scramble to grab the remaining non-capitalist territories of the globe[16] or the dividing up of the markets and no longer the conquest of new ones.[17]

Alongside these "economic" observations, all these illustrious revolutionaries wrote at length about a series of other factors in the political, social and inter-imperialist domains. Thus, for example, Lenin insisted on the hegemonic dimension of imperialism and its consequences in the decadent phase of capitalism "(1) the fact that the world is already partitioned obliges those contemplating a redivision to reach out for every kind of territory, and (2) an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry between several great powers in the striving for hegemony, i.e., for the conquest of territory, not so much directly for themselves as to weaken the adversary and undermine his hegemony. (Belgium is particularly important for Germany as a base for operations against Britain; Britain needs Baghdad as a base for operations against Germany, etc.)". This new characteristic of imperialism underlined by Lenin is essential to understand because it meant that "the conquest of territories" in the course of inter-imperialist conflicts in decadence has less and less economic rationality but rather takes on an increasingly strategic dimension: "Belgium is particularly important for Germany as a base for operations against Britain; Britain needs Baghdad as a base for operations against Germany, etc."[18]

So while we can indeed see the first signs of economic difficulty on the eve of 1914, these remained very limited, comparable to previous cyclical crises and not at all on the scale of the long crisis which was to begin in 1929 or as deep as the current crises; at the same time they appeared not at the level of a fall in the rate of profit but of a saturation of the markets, which was to prove the defining characteristic of the decadence of capitalism on the economic level as Rosa Luxemburg predicted: "the more numerous are the countries who have developed their own capitalist industry, and the more the need for the extension and the capacity of extension of production increases on the one hand, the less the capacity for the realisation of production increases in relation to the former. If we compare the bounds made by British industry in the years 1860-70, when Britain still dominated the world market, with its growth in the last two decades, since which time Germany and the United States of America have made considerable gains on the world market at Britain's expense, it becomes clear that growth has been much slower than before. The fate of British industry thus depends on German industry, North American industry, and in the end the industry of the world. At each stage of its development, capitalist production irresistibly approaches the epoch in which it will only be able to develop with increasing slowness and difficulty."[19]

From this short empirical examination, it is clear that the First World War did not break out in the wake of a fall in the rate of profit, nor of an economic crisis as Mattick and the IBRP claim. It now remains to examine the complement to the thesis of the IBRP, i.e. to verify empirically whether the destruction resulting from war was the basis for a rediscovered ‘prosperity' in peacetime, thanks to a re-establishment of the rate of profit through the destruction caused by war.

The inter-war period disproves the IBRP's thesis