6. The cycle of war-reconstruction

- 3776 reads

The self-destruction of Europe during World War I was accompanied by a 15 per cent growth in American production. Amid the chaos of the old continent, the United States discovered an important outlet; Europe had to import masses of consumer goods, means of production and arms from America. Once the war ended, the reconstruction of Europe proved to be the new and important outlet. Through massive destruction with an eye to reconstruction, capitalism has discovered a way out, dangerous and temporary but effective, for its new problems of finding outlets.

During the first war, the amount of destruction was not 'sufficient'; military operations only directly affected an industrial sector representing less than one-tenth of world production (around 5-7 per cent) [1] [1]. In 1929, world capitalism again ran into a crisis situation.

As if the lesson had been well-learned the amount of destruction accomplished in World War 2 was far more intense and extensive. "All in all therefore during the second world war almost a third of the total industrial sector of the world was drawn into the direct arena of military action." [2] [2]

Russia, Germany, Japan, Great-Britain, France and Belgium violently suffered the effects of a war which for the first time had the conscious aim of systematically destroying the existing industrial potential. The 'prosperity' of Europe and Japan after the war seemed already foreseen by the end of the war, (Marshall Plan, etc...).

Contrary to common opinion, 'reconstruction' does not stop when the ruined nation regains its pre-war levels of production: reconstruction does not only involve the directly productive goods but also all the infra-structures and means of life destroyed during the war, even though their reconstruction is not immediately necessary in order to attain pre-war production levels. Reconstruction is never undertaken with pre-war technology; important progress in productivity and the concentration of capital has occurred during the war. Also, the fact that the former levels of production are regained does not necessarily mean that the same mass of value will again be tied up in productive capital. Finally, during their destruction those countries concerned became industrially backward in relation to the other powers. Their reconstruction cannot be considered completed until the moment when they regain not their former levels o production, but ones which make them again internationally competitive.

In this sense, reconstruction characterised the growth of the post-World War 2 period right up to the 1960s and not just to the 1950s as is often supposed.

Permanent armaments production

- 2328 reads

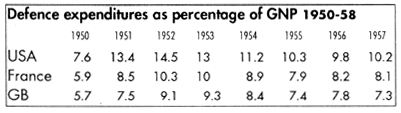

If we remember that the percentage of the American national revenue destined for military purposes was less than 1 per cent in 1929 and that before 1913 the 4 per cent reached by Germany on the eve of the war represented an unprecedented maximum, we will understand the significance of the per centages maintained after 1945.

[2] [21] Claude, p.70

[3] [22] League of Nations, ‘Apercu General Du Commerce Mondial' 1938, cited by Henri Claude, p.30

[4] [23] Claude, p.24

[6] [25] Sternberg, p.494

[7] [26] For example, in 1962 American military expenditure in planes, missiles, electronic and telecommunications equipment accounted for 75 per cent of the total military expenses of the country. Ships, artillery, vehicles and related equipment which were once the mainstay of the armed forces, made up the remaining 25 per cent.

*sv¼v is the definition of the rate of exploitation (or the rate of surplus value).

[10] [29] Claude, p.61

[11] [30] In 1945, there was so much progress in capital concentration in the United States that it has been estimated (Fritz Sternberg) that the 250 largest enterprises produced the equivalent of what some 75,000 industries produced before the conflict.

[12] [31] Speech of May 28, 1941

[13] [32] 9,480,000 unemployed in 1939, 670,000 in 1944, 3,395,000 in 1949 (President's Economic Report, 1950)

[14] [33] United Nations, 26th Session of the General Assembly, United States response to the UN questionnaire on ‘The Economic and Social Consequences of the Arms Race...' 1972, p.48

The slowing down of the growth of the productive forces of capitalism since World War 2

- 3063 reads

The accelerating of the rhythm of development of the productive forces after World War 2 was one of the factors which provoked the split in the '4th International' in 1952. According to the 'Lambertist' faction of the AJS-OCI (The Organisation Communiste Internationaliste is the French Trotskyist group headed by Lambert, formerly linked to the Healyite Socialist Labour League in the UK (now the Workers Revolutionary Party) and the Wolforthite Workers League in the US. The AJS (Alliance de Jeunesse Socialiste, is the youth section of the OCI), the economic premise underlying the possibility of, and necessity for, socialist revolution is the total cessation of the growth of the productive forces. The Lambertists are, in this respect, faithful to the letter to the transitional programme of Trotsky. We have seen at the beginning of this article, the inconsistency of this theory from the marxist point of view.Growth statistics for the period of reconstruction render this theory absurd. In order to bring the statistics into line with their views, the Lambertists insist on the unproductive nature of armaments production. But even if one is certain that arms production acts as a brake on real production, it is statistically impossible to pretend that it has paralysed or 'nullified' the growth of the productive forces since 1945.The stubborn, short-sighted dogmatism of this position is all the more ridiculous in that it violently clashes with another dogma (the transitional programme) so dear to the AJS-OCI: "The USSR is not capitalist, it is a degenerated workers‘ state." Productive forces could thus develop there much more rapidly than in the United States. But Russia devotes a much greater part of its production to armaments than have the greatest Western powers.For the Trotskyists of the official 4th International, (Ligue Communiste -Mandel, defunct), decadence is not defined by the 'clogging' of the growth of the productive forces, but by the slowing down of this growth under the weight of the relations of production. In that they are faithful 'to the letter' to Marx. But if one scratches just a little below the surface, one discovers a patchwork of dogmas as contradictory as those of the AJS.In a pamphlet entitled, "Qu'est-ce-que l'AJS?", Weber, the theoretician of the 4th International, tried to criticise the "absurd theories and grotesque contortions of the Lambertists" on this question [1] [35]. In order to resolve the contradictions apparent in the dogma of the 'degenerated workers' state', (Mandel and Co also believe that there are a lot of countries in the world which are non-capitalist), Weber attributes a productive character to armaments production. To answer the problem of Trotsky's formulation that the premises of socialism are dependent on the arrested growth of productive forces, Weber explains that Trotsky only 'described the reality which was before his eyes in 1938'.As for the problem of defining the characteristics or the content of the slow-down which defines the periods of decadence, the Trotskyists no longer give us anything very concrete to go on. They talk about 'neo-capitalism' which supposedly began right after World War 2 and which is characterised by an "unprecedented economic expansion". They tell us that "the general crisis of capitalism was brought about by the first war"; but they also tell us that it was in 1848, 120 years ago, that Marx denounced the capitalist production as fetters on the development of the productive forces; it was in 1848 that he declared the capitalist mode of production to be "regressive and reactionary" [2] [36]. And they remind us about the sentences in the Communist Manifesto:"For many a decade past the history of industry and commerce is but the history of the revolt of modern productive forces against modern conditions of production...And here it becomes evident, that the bourgeoisie is unfit any longer to be the ruling class in society, and to impose its conditions of existence upon society as an over-riding law". This selection is cited by Weber in order to pose the question, "Is this to say that Marx and Engels were mistaken?" Weber argues that the reply to this question which every Lambertist must unhesitatingly agree to if he takes the Lambertist theses at all seriously, is the following. "If the contradiction between the development of productive forces and the continuation of the capitalist relations of production is expressed purely and simply in terms of the blockage of the productive forces, then Marx and Engels were wrong, not only in 1848 but all their lives, since according to the Lambertist position, the stagnation of the productive forces began in 1914!" More confusion follows: "But the Lambertists theory of a 'clogging' of the productive forces is foreign to marxism..."On the other hand, if you believe that Weber, Marx and Engels are not wrong, then after the infallibility of Trotsky, the infallibility of Marx and Engels is also saved, in Weber's head at least, and the dogma of these different infallibilities is respected. But suddenly you find yourself entangled in the following notions: the decadence of capitalism was under full sway in 1848; the beginning of "the general crisis of capitalism" only in 1914; and the height of the victorious expansion of "neo-capitalism" in 1960! Is the rupture in capitalist development to be situated in the "decades before 1848", "120 years ago" in 1848, or in 1914, or even in 1945 at the beginning of the so-called "neo-capitalism"? When does this famous "epoch of social revolution" of which Marx spoke begin?It would be difficult to piece together any coherent findings in this lamentable theoretical patchwork which was, in any case, elaborated only to salvage a few official Trotskyist dogmas and to justify the 'progressive character' of all bureaucratic movements in the third world, the 'anti-imperialist' nature of Peking and Moscow, and all sorts of opportunisms involving trade unions ('critical' support), elections ('pedagogical' benefits), and reforms ('transitional movements towards socialism'). But in the last analysis, for the Leninists of What Is To Be Done?, all these economic problems of characterising historical periods, etc... are unimportant because these 'scientists' are convinced that the only real problem is revolutionary leadership: "The present crisis in human culture is the crisis in the proletarian leadership." (Trotsky, 1938)There is little to be learned from this theoretical patchwork quilt (which actually serves only as a cloak with which to cover the various types of Trotskyist opportunism), except to realise the necessity of developing a serious definition of what is signified by the slackening in the growth of the productive forces.As we said at the beginning of this article, a period of decadence is expressed by a slackening or slowing down in the growth of the productive forces when:1) such a lack of growth specifically results from the constraints imposed by the relations of production;2) the process is inevitable and irreversible;3) an ever widening gap is created between the actual development of the productive forces and what would have been possible had the fetters constituted by the dominant relations of production been absent.When Marx and Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto, there were periodic slow-downs in growth caused by cyclical crises. During these crises, the fundamental contradictions of capitalism were clearly projected. But these "revolts of the modern forces of production against the modern relations of production" were only the revolts of capitalism's youth. The outcome of these regular explosions was only the strengthening of the system which, during the course of his dramatic ascension, had thrown off its infantile habits along with the last feudal constraints standing in its way. In 1850, only 10 per cent of the world population was integrated into the capitalist relations of production. The wage system had its whole future before it. Marx and Engels had the genius to extract from the crises of capitalism's ascendancy the essence of all crises to come. In so doing, they revealed to future generations the bases of capitalism's most profound convulsions. They were able to do so because from its beginning a social form carries inside itself the seeds of all the contradictions which will carry it to its death. But insofar as these contradictions are not developed to the point of permanently hindering the economic growth, they constitute the very motor of this growth. The slow-downs which the capitalist economy of the nineteenth century joltingly experienced have nothing to do with its permanent and growing fetters. On the contrary, the intensity of these crises was softened by their repetition. Marx and Engels were completely mistaken in their analysis of 1848. (Marx in Class struggles in France as well as Engels in his later introduction to this text, were moreover not afraid to recognise this). Much more lucid was Rosa Luxemburg's analysis in 1898: "If one looks more closely at the different causes of all previous great international crises, one will be convinced that they are all not the expression of the weakness of old age of the capitalist economy but rather of its childhood. We still have not progressed to that degree of development and exhaustion which would produce the fatal, periodic collision of the forces of production with the limits of the market, which is the actual capitalist crisis of old age....If the world market has now more or less filled out, and can no longer be enlarged by sudden extensions; and if, at the same time, the productivity of labour strides relentlessly forward, then in less or more time the periodic conflict of the forces of production with the limits of exchanges will begin, and will repeat itself more sharply and more stormily." (Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or revolution )When the period of post-World War 2 reconstruction opened, a long time had already elapsed since capitalism could "no longer be enlarged by sudden extensions". For decades, the productivity of labour had risen too quickly to be contained within the capitalist relations of production. For thirty years already, repeated and increasingly violent assaults of the forces of production against the barriers which block their development have brutally ravaged the entire society.Only the misery and the barbarism of these years of growing depression can account for the general bewilderment provoked by the economic development which began with reconstruction. For, however one envisages it, this 'development' constitutes in fact the greatest slackening in the growth of the productive forces that humanity has ever known. Never before has the contrast between what is possible and what is actually accomplished reached such proportions. Never "has the continuation of development appeared so much like a decline". (Marx).In order to appreciate the magnitude of this decline many questions might be asked. Should armaments production be included or not in the volume of production effectively realised in order to determine the development of the productive forces? How can we determine the level of production 'which would have been possible'? Must we compare the levels effectively realised with those which would have been reached if economic growth continued to follow the rates achieved during the system's ascendant phase? And, in that case, should we begin from 1913 or 1945? Or should we determine the rates which would have been possible given the existing technology of that time? Is it necessary to consider whether the productive forces 'left on their own' would have developed according to rates which were increasing or which remained constant?

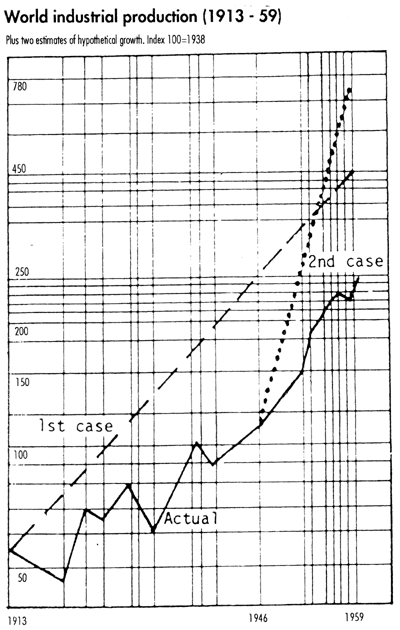

In order to answer these questions we are going to compare the world's industrial production as it developed from 1913 to 1959 (including armaments production) with what would have taken place if industrial growth had continued after 1913 along the same rates attained during the decade 1880-1890. [3] [37] (We will assume a constant rate of development. In reality, this rate would tend to increase under the influence of rising productivity). We are particularly interested in the period which began right after World War 2. The comparison with the hypothetical growth defined in the first example (above) will be completed by a second comparison with another example of hypothetical growth based on new growth rates made possible by the development of technology at the time of World War 2. In order to get a more precise idea of the extent of the decline we will start this hypothetical growth from the end of the war in 1946. For this comparison we have chosen as the growth rate which would have been attainable following World War 2 (if the capitalist relations of production had not hindered development), the rate which was reached by the United States industrial production between 1939 and 1944. The war had opened up important outlets for the American economy and thus enabled the productive apparatus to operate at its maximum strength. However, this rate is limited by the fact that such an immense growth in output involved a type of production which could not be reintegrated into production in order to accelerate, in its turn, further growth; namely, armaments. Moreover, this rate was realised in the United States at the same time that the other powers were war-torn: American economic growth, therefore, could not profit from technological development furnished by international collaboration. We are keeping this rate of growth nevertheless, because it has the virtue of having been actually attained at a given time and thus gives us an appreciation of society's actual technological capacities. The index of United States industrial production went from 109 to 235 between 1939 and 1944 ( 100=1938 ) which is a rate of growth of 110 per cent in five years, (see graph).

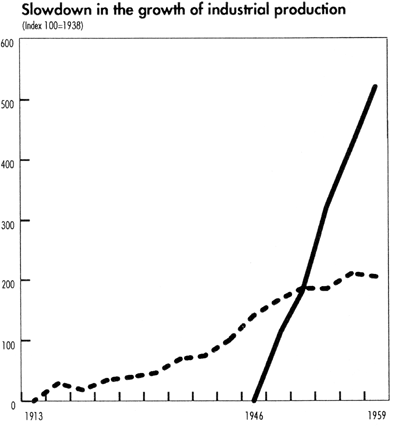

On the graph we can see the divergences which, in both cases, widen with growing rapidity. We can see, even more clearly, the magnitude of these slow-downs by recording their progression on a separate graph. (The first graph is scaled in semi-logarithms so the progression of the divergences is poorly shown.)

These graphs are only very approximate and give a picture which is probably an under-estimation of the actual extent of the brake on the rate of growth. However, they do give a clear idea of the unprecedented effectiveness of this brake, of its irreversible and inevitable character, as well as its uninterrupted increase. The periods during which the gaps are narrowed correspond to the periods of rearmament or reconstruction. Here their function as temporary palliatives clearly stands out.After the slowing down of the growth of productive forces, it is necessary to see whether capitalism after 1914 and especially after 1945 has been condemned to deeper and more widespread crises (the second characteristic of a society's economic decadence). This will lead us to examine the problem of the nature of armaments productions and its limitations. We will first consider the period 1914-46, followed by the period extending from the end of World War 2 to the present.

[1] [38] ‘Qu' est-ce que l ‘AJS', Cahiers rouge, series ‘Marx ou creve' (sic), pp. 13-35

[2] [39] Ibid, p. 30

[3] [40] From 1880 to 1890, the index of industrial production multiplied by 1.6, Sternberg, p.21