1995 - 80 to 83

- 5307 reads

International Review no.80 - 1st quarter 1995

- 4003 reads

1995: 20 years of the ICC

- 16617 reads

The text published below was written in 1995, 20 years after the founding congress of the International Communist Current in 1975.

We reprint this text in order to give our readers an introduction to the history of our organisation, and an insight into the method which inspired its creation as an international regroupment of local organisations. This remains our method to this day.

Twenty years ago, in January 1975, the International Communist Current was formed. This is a considerable lifespan for a proletarian organisation, when we consider that the IWA only survived 12 years (1864-76), the Socialist International 25 years (1889-1914), and the Communist International 9 years (1919-28). Obviously, we do not pretend that our organisation has played a part comparable to that of the workers' Internationals. Nonetheless, the ICC's 20 years of experience belongs entirely to the proletariat, whence our organisation springs just as did the Internationals of the past, and as do the other organisations which defend communist principles today. In this sense it is our duty, and this anniversary provides us with an opportunity, to pass on to our class some of the lessons which we draw from these two decades of combat.

The comparison between the ICC and the organisations which have marked the history of the workers' movement, especially the Internationals, is disconcerting: whereas the latter organisations included or influenced millions, even tens of millions of workers, the ICC is only known, throughout the world, to a tiny minority of the working class. This situation, which is also the lot of all the other revolutionary organisations, should encourage us to modesty. It should not, however, lead us to underestimate the work we do accomplish, and still less should it discourage us. Ever since the proletariat first appeared as an actor on the social scene a century and a half ago, its historic experience has shown that the periods when revolutionary positions exerted a real influence over the working masses have been relatively limited. And moreover, it is on the basis of this reality that the bourgeoisie's ideologues have claimed that the proletarian revolution is a pure utopia, since most workers do not think it either necessary or possible. This phenomenon, which was already apparent when mass workers' parties existed, at the end of the 20th century, has been further amplified by the defeat of the revolutionary wave which followed World War I.

The working class made the world bourgeoisie tremble, and the latter took its revenge by subjecting its enemy to the longest counter-revolution in its history. And the spearhead of the counter-revolution was precisely those organisations - the socialist and communist parties, and the trades unions - which the working class had founded for its own combat, but which had gone over to the bourgeois camp. The vast majority of the socialist parties were already in the service of the bourgeoisie during the War, calling the on workers for "National Unity", and in some countries even joining the governments which had unleashed the imperialist slaughter. Then, when the revolutionary wave unfurled following the October 1917 revolution in Russia, these same parties played the part of executioners for the bourgeoisie, either by deliberately sabotaging the movement, as in Italy in 1920, or by ordering and organising the murder of workers and revolutionaries in their thousands, as in Germany in 1919. Later on, the communist parties, which had been formed around those socialist party fractions that refused to join the imperialist war effort, and which had taken the lead in the revolutionary wave by rallying around the Communist International (founded in March 1919), went down the same path as their socialist predecessors. Dragged down by the defeat of the world revolution, and by the degeneration of the revolution in Russia, they joined the capitalist camp during the 1930's, to become the most faithful recruiting sergeants for World War II in the name of anti-fascism and "defence of the socialist fatherland". Having been the main architects of the "resistance" movements against the German and Japanese occupying armies, they continued their dirty work by exercising a ferocious control over the workers during the reconstruction of the ruined capitalist economies.

Throughout this period the massive influence that the socialist or "communist" parties were able to have of the working class stifled the consciousness of workers, steeped them in chauvinism and either turned them away from any perspective for the overthrow of capitalism or confused this perspective with the strengthening of the democratic bourgeoisie or subjected them to the lie that the capitalist states of the Eastern bloc were "socialism" incarnate. During this "midnight in the century" the real communist forces who were chased out of the degenerating Communist International were in a situation of extreme isolation when they weren't actually exterminated by Stalinist or fascist agents of the counter-revolution. In the worst conditions in the history of the workers' movement the handful of militants who managed to escape the wreckage of the Communist International worked to defend communist principles in order to prepare the future historic resurgence of the proletariat. Many lost their lives or were worn out to the point that their organisations - the fractions and groups of the communist left - disappeared or else were crippled by sclerosis.

The terrible counter-revolution which crushed the working class following its glorious battles after World War I lasted for nearly forty years. But once the last fires of the reconstruction following the second world war had gone out and capitalism was again faced with the open crisis of its economy at the end of the 60s, the proletariat raised its head once more. May 1968 in France, the "rampant May" in Italy in 1969, workers' struggles in the winter of 1970 in Poland and a whole series of workers' struggles in Europe and on other continents: the counter-revolution was over. The best proof of this fundamental change in the course of history was the appearance and development in various parts of the world of groups who based themselves, often in a confused way, on the traditions and positions of the Communist Left. The ICC was formed in 1975 as a regroupment of some of these formations that the historic resurgence of the proletariat had produced. That fact that since then the ICC has not only continued to exist but has grown, doubling the number of sections is excellent proof of this historic resurgence of the proletariat, an excellent indication that the latter has not been defeated and that the historic course is still towards class confrontations. This is the first lesson to be drawn from the 20 years existence of the ICC against the idea shared by many other groups of the Communist Left who think that the proletariat hasn't yet emerged from the counter-revolution.

In International Review n°40, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the ICC, we drew a number of lessons from our experience in this earlier period. We recall them briefly here to underline some of the points we made about the period that followed. However before making such an assessment we must quickly go back to the history of the ICC. And for readers who are unacquainted with the article of 10 years ago we reprint large extracts from it here which deal with this history.

The constitution of an international pole of regroupment

The "prehistory" of the ICC

"The first organised expression of our Current appeared in Venezuela in 1964. It consisted of very young elements who had begun to evolve towards class positions through discussions with an older comrade who had behind him the experience of being a militant in the Communist International, in the left fractions which were excluded from it at the end of the 1920s - notable the Left Fraction of the Communist Party of Italy - and who was part of the Gauche Communiste de France until its dissolution in 1952. Straight away this small group in Venezuela - which, between 1964 and 1968 published ten issues of its review Internacionalismo - saw itself as being in political continuity with the positions of the Communist Left, especially those of the GCF. This was expressed in particular through a very clear rejection of any policy of supporting so-called "national liberation struggles", a myth that was very prevalent in Latin American countries and that weighed heavily on elements trying to move towards class positions. It was also expressed in an attitude of openness towards, and making contact with, other communist groups - an attitude which had previously characterised the International Communist Left before the war and the GCF after it. Thus the group Internacionalismo established or tried to establish contacts and discussions with the American group News and Letters (...) and in Europe with a whole series of groups who were situated on class positions (...) With the departure of several of its elements for France in '67 and '68, this group interrupted its publication for several years, before Internacionalismo (new series) began in 1974 and the group became a constituent part of the ICC in 1975.

"The second organised expression of our Current appeared in France in the wake of the general strike of May '68 which marked the historic resurgence of the world proletariat after more than 40 years of counter-revolution. A small nucleus was formed in Toulouse around a militant of Internacionalismo. This nucleus participated actively in the animated discussions of Spring '68, adopted a 'declaration of principles' in June and published the first issue of Révolution Internationale (RI) at the end of that year. Straight away, this group continued Internacionalismo's policy of looking for contact and discussion with other groups of the proletarian milieu both nationally and internationally. (...) From 1970 onwards, it established closer links with two groups who managed to swim out of the general decomposition of the councilist milieu after May '68: the 'Organisation Conseilliste de Clermont Ferrand" and "Cahiers du Communisme di Conseils (Marseille)", following an attempted discussion with the GLAT which showed that this group was moving further and further away from marxism. Discussion with the former two groups, however, proved much more fruitful and after a whole series of meetings in which the basic positions of the Communist Left were examined in a systematic manner, RI, the OC of Clermont and CCC came together in 1972 around a platform which was a more detailed and precise version of RI's declaration of principles of 1968. This new group published the Revue Internationale as well as a Bulletin d'Etude at de Discussion and was to be at the centre of a whole work of international contact and discussion in Europe up until the foundation of the ICC two and a half years later.

"On the American continent, the discussions that Internacionalismo had with News and Letters left some traces in the USA and, in 1970, a group was formed in New York (part of which was made up of former members of News and Letters) around an orientation text with the same basic positions as Internacionalismo and RI (...) The new group began to publish Internationalism and like its predecessors set about establishing discussions with other communist groups. Thus it maintained contacts and discussions with Root and Branch in Boston, which was inspired by the councilist ideas of Paul Mattick, but these proved not to be fruitful since the Boston group was more and more turning into a club or marxology. In 1972, Internationalism sent a proposal for international correspondence to twenty groups, in the following terms:

"(...) 'Together with the heightened activity of the working class there has been a dramatic growth in the number of revolutionary groups having an internationalist communist perspective. Unfortunately, contact and correspondence between these groups has largely been haphazard and episodic. Internationalism makes the following proposal with a view towards regularising and expanding contact and correspondence between groups having an internationalist communist perspective (...)

"In its positive response, RI said:

"'Like you we feel the necessity for the like and activities of our groups to have as international a character as the present struggles of the working class. This is why we have maintained contact through letters or directly with a certain number of European groups to whom your proposal was sent. (...) We think that you initiative will make it possible to broaden the scope of these contacts and at the very least, to make our respective positions better known. We also think that the perspective of a future international conference is the logical follow-on from the establishment of this political correspondence (...)

"In its response, RI thus underlined the necessity to work towards international conferences of groups of the Communist Left, without any idea of haste: such a conference should be held after a period of correspondence. This proposal was in continuity with the repeated proposals it had made (in '68, '69 and '71) to the Partito Comunista Internazionalista (Battaglia Comunista - BC) to call such conferences, since at the time this organisation was the most important and serious group in the camp of the Communist Left in Europe (alongside the PCI - Programma Comunista, which was basking in the comfort of its splendid isolation). But despite Battaglia's open and fraternal attitude, these proposals had each time been rejected (...).

"In the end, Internationalism's initiative and RI's proposal did lead, in '73 and '74, to the holding of a series of conferences and meetings in England and France during the course of which a process of clarification and decantation got under way, notably with the evolution of the British group World Revolution (which came out of a split in Solidarity) towards the positions of RI and Internationalism. WR published the first issue of its magazine in May 1974. Above all, this process of clarification and decantation created the bases for the constitution of the ICC in January '75. During this period, RI had continued its work of contact and discussion at an international level, not only with organised groups but also with isolated elements who read its press and sympathised with its positions. This work led to the formation of small nuclei in Spain and Italy around the same positions and who in '74 commences publication of Accion Proletaria and Rivoluzione Internazionale.

"Thus, at the January '75 conference were present Internacionalismo, Révolution Internationale, Internationalism, World Revolution, Accion Proletaria and Rivoluzione Internazionale, who shared the political orientations which had been developed since 1964 with Internacionalismo. Also present were Revolutionary Perspectives (who had participated in the conferences of '73-'74), the Revolutionary Workers' Group of Chicago (with whom RI and Internationalism had begun discussions in '74) and Pour Une Intervention Communiste (which published the review Jeune Taupe and had been formed around comrades who had left RI in '73 (...). As for the group Workers' Voice, which had participated actively in the conferences of the previous years, it had rejected the invitation to this conference because it now considered that RI, WR, etc were bourgeois groups (!) because of the position of the majority of their militants on the question of the state in the period of transition from capitalism to communism (...).

"This question was on the agenda of the January 1975 conference... However it wasn't discussed at the conference which saw the need to devote the maximum of its time and attention to questions that were much more crucial at that point:

that analysis of the international situation;

the tasks of revolutionaries within it;

the organisation of the international current.

"Finally the six groups whose platforms were based on the same orientations decided to unify themselves into a single organisation with an international central organ and publishing a quarterly review in three languages - English, French and Spanish (...) - which took over from RI's Bulletin d'Etude et de Discussion. The ICC had been founded. As the presentation to number 1 of the International Review said, "a great step forward has just been taken". The foundation of the ICC was the culmination of a whole work of contacts, discussions and confrontations between the different groups which had been engendered by the historic awakening of the class struggle. (...) But above all it lay the bases for even more considerable work to come.

The first ten years of the ICC: the consolidation of an international pole

"This work can be seen by the readers of the International Review and of our territorial press and confirms what we wrote in the presentation to International Review n°1:

'Some people will consider that the publication of the Review is a precipitous action. It is nothing of the kind. We have nothing in common with those noisy activists whose activity is based on a voluntarism as frenzied as it is ephemeral' (1) (...)

"Throughout the ten years of its existence, the ICC has obviously encountered numerous difficulties, has had to overcome various weaknesses, most of which are linked to the break in organic continuity with the communist organisations of the past, to the disappearance of sclerosis of the left fractions who detached themselves from the degenerating Communist International. It has also had to combat the deleterious influence of the decomposition and revolt of the intellectual petty bourgeoisie, an influence that was particularly strong after '68 and the period of the student movements. These difficulties and weaknesses have for example expressed themselves in various splits - which we have written about in our press - and especially by the major convulsions which took place in 1981, in the ICC as well as the revolutionary milieu as a whole, and which led to the loss of half our section in Britain. In the face on the difficulties in '81, the ICC was even led to organise an extraordinary conference in January '82 in order to reaffirm and make more precise its programmatic bases, in particular concerning the function and structure of the revolutionary organisation. Also, some of the objectives the ICC set itself have not been attained. For example, the distribution of our press has fallen short of what we had hoped for. (...)

"However, if we draw up an overall balance sheet of the last ten years, it can clearly be seen to be a positive one. This is particularly true if you compare it to that of other communist organisations who existed after 1968. Thus, the groups of the councilist current, even those who tried to open themselves up to international work like ICO, have either disappeared or sunk into lethargy: the GLAT, ICO, the Situationist International, Spartacusbond, Root and Branch, PIC, the councilist groups of the Scandinavian milieu... the list is long and this one is by no means exhaustive. As for the organisations coming from the Italian Left and who all proclaim themselves to be THE PARTY, either they haven't broken out of their provincialism, or have dislocated and degenerated towards leftism like Programma (2), or are today imitating, in a confused and artificial way, what the ICC did ten years ago, as is the case with Battaglia and the CWO. Today, after the so-called International Communist Party has collapsed like a pack of cards, after the failure of the FOR in the USA (the FOCUS group), the ICC remains the only communist organisation that is really implanted on an international scale.

"Since its formation in 1975, the ICC has not only strengthened its original territorial sections but has implanted itself in other countries. The work of contact, discussion and regroupment on an international scale has led to the establishment of new sections of the ICC:

- 1975: the constitution of the section in Belgium which published the review, now a newspaper, Internationalisme, in two languages (French and Dutch), and which fills the gap left by the disappearance in the period after World War II of the Belgian Fraction of the International Communist Left.

- 1977: constitution of the nucleus in Holland, which began publication of the magazine Wereld Revolutie. This was particularly important in a country which has been the stamping ground of councilism.

- 1978: constitution of the section in Germany which began publication of the IR in German and, the following year, of the territorial magazine Weltrevolution. The presence of a communist organisation in Germany is obviously of the highest importance given the place occupied by the German proletariat in the past and the role it is going to play in the future.

- 1980: constitution of the section in Sweden which publishes the magazine Internationell Revolution. (...)

"If we underline the contrast between the relative success of our Current and the failure of other organisations, it's because this demonstrates the validity of the orientations we have put forward in twenty years of work for the regroupment of revolutionaries, for the construction of a communist organisation. It is our responsibility to draw out these orientations for the whole communist milieu.

The main lessons of the first 10 years of the ICC

"The bases on which our Current has carried out this work of regroupment even before its formal constitution are not new. In the past they have always been the pillars of this kind of work. We can summarise them as follows:

- the necessity to base revolutionary activity on the past acquisitions of the class, on the experience of previous communist organisations; to see the present organisation as a link in a chain of past and future organs of the class;

- the necessity to see communist positions and analyses not as a dead dogma but as a living programme which is constatly being enriched and deepened;

- the necessity to be armed with a clear and solid conception of the revolutionary organisation, of its structure and its function within the class."

These lessons that we drew 10 years ago (and which are more developed in International Review n°40 which we recommend our readers to refer to) obviously remain valid today and our organisation has striven constantly to put them into practice. However while during the first 10 years of its existence its central task was to build an international pole of regroupment for revolutionary forces, its main responsibility in the subsequent period has been to confront a series of trials ("trials by fire" in a way) that have come out of the convulsions taking place in the international situation in particular.

Trial by fire

At the 6th Congress of the ICC which was held in November 1985, a few months after the 10 year anniversary of the ICC we said:

"At the beginning of the 80s the ICC characterised them as 'the years of truth'; years in which the main stakes for the whole of society would be revealed in all their terrible breadth. Half way through the decade the evolution of the international situation has fully confirmed this analysis:

- by a further aggravation of the convulsions of the world economy which has been manifested since the beginning of the 80s by the most serious recession since the 30s;

- by an intensification of tensions between the imperialist blocs which occurred in teh same period and was expressed in a considerable increase in military expenditure and through the development of clamorous war campaigns with Reagan as chantre , head of the most powerful bloc;

- by the resurgence of class struggle during the second half of 1983 after its momentary reflux from 1981 to 1983 just before and after the repression of the workers in Poland. This resurgence is characterised by a hitherto unprecedented simultaneity of the struggles especially in the important centres of capitalism and of the working class in western Europe" (Resolution on the international situation, International Review n°44).

This framework proved valid until the end of the 80s even though the bourgeoisie did what it could to present the "recovery" of 1983 to 1990, that was on the basis of the number 1 world power going into huge debt, as the "definitive end" of the crisis. As Lenin said, facts are stubborn and since the beginning of the 90s capitalism's tricks have led to an open recession even more long and brutal than the previous ones; this has been transformed the euphoria of the average bourgeois into a profound moroseness.

Likewise the wave of workers' strikes that began in 1983 continues with moments of reflux and moments of greater intensity up to 1989 which forced the bourgeoisie to bring forward various forms of base unionism (such as coordinations) in order to counteract the growing discredit of the official union structures.

However one aspect of this framework was dramatically put into question in 1989; that of imperialist conflicts. It's not that the marxist theory had been suddenly proved wrong by the "overcoming" of such conflicts but rather that one of the two main protagonists of such conflicts, the eastern bloc, collapsed dramatically. What we called the "years of truth" had proved fatal for an aberrant regime that had been built on the ruins of the 1917 revolution and for the bloc it dominated. An historic event of such breadth that overturned the map of the world created a new situation unprecedented in history in the sphere of imperialist conflicts. The latter took on forms hitherto unknown that revolutionaries have a responsibility to understand and analyse.

At the same time these upheavals that affected those countries that presented themselves as "socialist" dealt a very heavy blow to the consciousness and combativeness of the working class which had to face the most serious reflux since the historic resurgence at the end of the 60s.

So the international situation in the last ten years has compelled the ICC to confront the following challenges:

- to be an active factor in the class combats that took place between 1983 and 1989;

- to understand the significance of the 1989 events and the consequences they would have in the sphere of imperialist conflicts as well as the class struggle;

- more generally to develop a framework to understand the period in the life of capitalism of which the colllapse of the eastern bloc was the first great manifestation.

An active factor in the class struggle

After the 6th Congress of the section in France (the largest in the ICC) held in 1984 the 6th ICC Congress placed this concern at the heart of its agenda. However the effort made by our international organisation over several months to rise to its responsibilities towards the class at the beginning of 11984 came up against the persistence within its ranks of conceptions that underestimated the function of the revolutionary organisation as an active factor in the proletarian struggle. The ICC identified these conceptions as a result of centrist slidings towards councilism. This was mainly a product of the historic conditions in which it was constituted as among the groups and elements who participated in its formation there existed a strong distrust of anything resembling Stalinism. In line with councilism these elements tended to put on the same level Stalinism, the conceptions of Lenin on the organisational question and the very idea of the proletarian party. During the 70s the ICC had made a critique of Stalinist conceptions but it hadn't gone far enough and so these continued to weigh on certain parts of the organisation. When the struggle against the vestiges of councilism began at the end of 1983 a number of comrades refused to see the reality of their councilist weaknesses, fantasising that the ICC was conducting a "witch hunt". To avoid the problem posed; centrism towards councilism, they "discovered" that centrism can no longer exist in the decadent period of capitalism (3). Added to such political incomprehensions these comrades, most of whom were intellectuals unwilling to accept criticism, felt a sense of wounded pride as well as "solidarity" towards their friends whom they deemed to be unfairly "attacked". As we pointed out in the International Review n°45 it was a sort of "remake" of the 2nd Congress of the POSDR in which centrism on the organisational question and the weight of the circle spirit, which meant that links of affinity took priority over political relationships, led the Mensheviks to split. The "tendency" that was formed at the beginning of 1985 was to follow the same pathe and split at the time of the 6th Congress of the ICC to constitute a new organisation, the "External Fraction of the ICC" (FECCI). However there is a big difference between the fraction of the Mensheviks and that of the FECCI. The former was to prosper by gathering together the most opportunist currents of Russian Social Democracy and ended up in the bourgeois camp whereas the FECCI has collapsed, keeping more and more of a low profile and producing its publication, International Perspectives at greater and greater intervals. n the end the FECCI rejected the platform of the ICC although at their formation they gave as their main task the defence of this same platform that the ICC which according to them was "degenerating", was in the process of betraying.

At the same time as the ICC was fighting against the vestiges of councilism within it, it participated actively in the struggle of the working class as our territorial press throughout this period shows. Despite the smallness of its forces our organisation was present in the various struggles. Not only did it distribute its press and leaflets, it also participated directly whenever possible in workers' assemblies to defend the need for the extension of the struggles and workers' control over them outside the various union forms; "official" unionism or "rank-and-file" unionism. So in Italy during the schools' strike in 1987 our comrades' intervention had a not negligible impact within the COBAS (rank and file committees) where they were present before these organisms were recuperated by rank-and-file unionism with the reflux in the movement. During this period one of the best indication that our positions were beginning to have an impact among the workers was the fact that the ICC became a particular object of hatred for some of the leftist groups. This was especially so in France where at the time of the strike on the railways at the end of 86 and of the strike in the hospitals in Autumn 88 the Trotskyist group "Lutte Ouvrière" mobilised its "strong arm men" to prevent our militants from intervening in the assemblies called by the "co-ordinations". At the same time ICC militants actively participated in - and were often the animators of - several struggle groups that drew together workers who felt the need to regroup outside the unions to push the struggle forward.

Obviously we mustn't "exaggerate" the impact that revolutionaries, and our organisation in particular, were able to have on the workers' struggles between 1983 and 1989. Generally the movement remained imprisoned by unionism, its "rank-and-file" variations taking the baton from the official unions where the latter had been too discredited. Our impact was very immediate and was anyway limited by the fact that our forces are still very small. But the lesson that we must learn from this experience is that when struggles develop revolutionaries find an echo when they're present because the positions they defend and the perspectives they put forward answer the questions that workers are asking. And for this to be true there's no need whatever for them to "hide their flag" or make the slightest concession to the illusions that may still weigh on the consciousness of the workers, particularly on the question of unionism. This is a valid lesson for all revolutionary groups which are often paralysed when confronted with struggles because the latter don't yet raise the question of capitalism's overthrow so they feel obliged to work with rank-and-file structures "to be heard" and thus give credibility to these capitalist organs.

Understanding the significance of the 1989 events

Just as it is the responsibility of revolutionaries to be present "on the ground" when there are workers' struggles they must also be able at any moment to give the working class as a whole a clear framework of analysis for what's happening in the world.

An important aspect of this task is the understanding of the economic contradiction that affect the capitalist system. Those revolutionary groups who are unable to demonstrate the insoluble nature of the crisis that the system's drowning in show that they haven't understood the marxist tradition they lay claim to and are of no use to the working class. This is so with a group like "Ferment Ouvrier Révolutionnaire" for example who refused even too acknowledge that there was a crisis. Their eyes were so glued to the specific characteristics of the 1929 crisis that they denied all the evidence over the years... until they disappeared.

It's also up to revolutionaries to be able to evaluate the steps that the movement of the class has accomplished; to recognise the moments when it's going forward and also those when it is in retreat. This task firmly conditions the kind of intervention to make among the workers because then the movement is going forward their responsibility is to push it to its limits and in particular to call for its extension. When it's in retreat to call the workers to struggle is to push them to fight in isolation and to call for extension is to contribute to the extension... of the defeat. It's often precisely at such moments that the unions call for extension.

Finally following and understanding the various imperialist conflicts also constitutes a responsibility of the greatest importance for communists. A mistake in this sphere can have dramatic consequences. For example at the end of the 30s the majority of the Italian Communist Fraction with Vercesi, its main animator, at its head, beleived that the different wars of the period, notably the war in Spain, in no way augured a generalised conflict. The outbreak of world war in September 1939 left the Fraction completely crippled and it was several years before they were able to reconstitute themselves in the south of France and take up militant work again.

As for the present period it was extremely important to be clear on the events taking place during the summer and autumn of 1989 in the eastern bloc countries. For its part the ICC mobilised itself to understand what was happening from the time that Solidarnosc came to power in Poland in the middle of the summer when usually "current affairs" are on holiday." (4) It adopted the position that what was happening in Poland was a sign that all the European Stalinist regimes were entering a crisis of unprecedented depth: "The perspective for all the Stalinist regimes is...by no means a "peaceful democratisation" or a "recovery" of the economy. With the intensification of the world crisis of capitalism these countries entered a period of convulsions of a breadth unknown even in their past that is "rich" in violent upheavals" (International Review n°59, "Capitalist convulsions and workers' struggles"). This idea is developed further in the "Theses on the economic and political crisis in the USSR and in the eastern countries" drafted on 15 September (almost two months before the fall of the Berlin wall) and adopted by the ICC at the beginning of October. In these theses we read (see International Review n°60):

"...since virtually the only cohesive factor in the Russian bloc is that of armed force, any policy which tends to push this into the background threatens to break up the bloc. Already, the Eastern bloc is in a state of growing dislocation. For example, the invective traded between East Germany and Hungary, between "reformist" and "conservative" governments, is not just a sham. It reveals real splits which are building up between different national bourgeoisies. In this zone, the centrifugal tendencies are so strong that they go out of control as soon as they have the opportunity (...)

We find a similar phenomenon in the peripheral republics of the USSR. These regions are more or less colonies of Tsarist or even Stalinist Russia (eg the Baltic countries annexed under the 1939 Germano-Soviet pact). However, unlike the other great powers Russia has never been able to decolonise, since this would have meant losing all control over these regions, some of which are vital economically. The nationalist moevements which today are profiting from a loosening of central control by the Russian party, are developing more than half a century late relative to the movements which hit the British and French empires; their dynamic is towards separation from Russia" (Point 18).

"...however the situation in the Eastern bloc evolves, the events that are shaking it today mean the historic crisis, the definitive collapse of Stalinism (...) In these countries, an unprecedented period of instability, convulsions and chaos has begun, whose implications go far beyond their frontiers. In particular, the weakening, which will continue, of the Russian bloc, opens the gates to a destabilisation of the whole system of international relations and imperialist constellations which emerged from World War II with the Yalta Agreements" (Point 20).

A few months later (January 1990), this last idea was given greater precision:

"The world's geopolitical configuration as it has lasted since World War II has been completely overturned by the events of the second half of 1989. There are no longer two imperialist blocs sharing the world between them. It is obvious (...) that the Eastern bloc has ceased to exist (...).

Does this disappearance of the Eastern bloc mean that capitalism will no longer be subjected to imperialist confrontations? Such a hypothesis would be entirely foreign to marxism (...) Today, the collapse of this bloc can absolutely not given renewed credence to such analyses: this collapse will eventually bring with it the collapse of the Western bloc (...) The disappearance of the Russian imperialist gendarme, and that to come of the American gendarme as far as its one-time "partners" are concerned, opens the door to the unleashing of a whole series of more local rivalries. For the moment, these rivalries and confrontations cannot degenerate into a world war (...) However, with the disappearance of the discipline imposed by the two blocs, these conflicts are liable to become more frequent and more violent, especially of course in those areas where the proletariat is weakest (...)

The disappearance of the two major imperialist constellations which emerged from World War II brings with it the tendency towards the recomposition of two new blocs. Such a situation, however, is not yet on the agenda..." (International Review n°61, "After the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, destabilisation and chaos").

Events since then, especially the crisis and war in the Gulf in 1990-91, have only confirmed our analyses (5). Today, the whole world situation, and notably what is happening in ex-Yugoslavia, is a blinding proof of the complete disappearance of all the imperialist blocs, just as some European countries, France and Germany in particular, are trying with great difficulty to encourage the formation of a new bloc based on the EEC, which would be capable of standing up to the power of the United States.

As far as the evolution of the class struggle is concerned, the Theses of the summer of 1989 also took position:

"Even in its death throes, Stalinism is rendering a last service to the domination of capital: in decomposing, its cadaver continues to pollute the atmosphere that the proletariat breathes (...) We thus have to expect a momentary retreat in the consciousness of the proletariat (...) In particular, reformist ideology will weigh very heavily on the struggle in the period ahead, greatly facilitating the action of the unions.

Given the historic importance of the facts that are determining it, the present retreat of the proletariat - although it doesn't call into question the historic course, the general perspective of class confrontations - is going to be much deeper than the one which accompanied the defeat of 1981 in Poland" (Point 22).

Once again, the last five years have amply confirmed this forecast. Since 1989, we have witnessed the most serious retreat by the working class since historic re-emergence at the end of the 60s. Revolutionaries had to be prepared for this situation in order to adapt their intervention accordingly, and above all, not to "throw the baby out with the bathwater" by mistaking the long reflux for a definitive incapacity of the proletariat to conduct and develop combats against capitalism. In particular, the signs of renewed workers' combativity, especially autumn 92 in Italy and autumn 93 in Germany (see International Review nos 72 and 75), should neither be overestimated (given the extent of the proletarian retreat), not underestimated, since they are the forerunners of an inevitable recovery in the combat and development of class consciousness throughout the industrialised countries.

Marxism is a scientific method. However, unlike the natural sciences it cannot verify its theories in laboratory conditions, or by improving its recording technology. Marxism's "laboratory" is social reality, and it demonstrates its validity through its ability to forecast that reality's evolution. The fact that the ICC was thus able to forecast, from the first symptoms of the Eastern bloc's collapse, the main events which were to shake the world in the five years that followed should not be put down to an aptitude for reading tea-leaves or astrological charts. It is simply the proof of the ICC's attachment to the marxist method, which is responsible for the success of our forecasts.

This being said, it is not enough to call yourself marxist to be able to use the method successfully. In fact, our ability to understand rapidly what was at stake in the world situation flows from the application of the method which we have taken from Bilan, and which we described ten years ago as one of the main lessons of our own experience: the necessity of attaching oneself firmly to the gains of the past, the necessity of regarding communist positions and analyses as a living programme, not a dead dogma.

The 1989 Theses thus began by recalling, in the first ten points, the framework that our organisation had adopted at the beginning of the 80s, following the events in Poland, for understanding the characteristics of the Eastern bloc countries. It was this analysis that allowed us to demonstrate that the Stalinist régimes of the Eastern bloc were finished. And it was a much older gain of the workers' movement (pointed out in particular by Lenin against Kautsky) - the understanding that there cannot exist only one imperialist bloc - that allowed us to declare that the end of the Eastern bloc opened the way to the disappearance of the Western bloc also.

Similarly, to understand what was happening, we had to call into question a schema which had remained valid for more than forty years: the world's division between a Western bloc led by the USA, and an Eastern bloc led by the USSR. We also had to be capable of understanding that the Russia which had been built little by little since the time of Peter the Great, would not survive the loss of its empire. Once again, there is no special merit in being able to call into question the schemas of the past. We did not invent this approach. It has been taught us by the experience of the workers' movement, and especially by its main fighters: Marx, Engels, Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin...

Finally, understanding the upheavals at the end of the 80s meant placing it within a general analysis of the present stage of capitalism's decadence.

The framework for understanding capitalism's present period

This is the work that we began in 1986, with the idea that we had entered a new phase in capitalist decadence: the system's decomposition. This analysis was laid out at the beginning of 1989 in the following terms:

"Up to now, the class combats which have developed in the four corners of the planet have been able to prevent decadent capitalism from providing its own answer to the dead end of its economy: the ultimate form of its barbarity, a new world war. However, the working class is not yet capable of affirming its own perspective through its own revolutionary struggles, nor even of setting before the rest of society the future that it holds within itself.

It is precisely this temporary stalemate, where for the moment neither the bourgeois nor the proletarian alternative can emerge openly, that lies at the origin of capitalism's putrefaction, and which explains the extreme degree of decadent capitalism's barbarity. And this rottenness will get still worse with the inexorable aggravation of the economic crisis" (International Review n°57, "The decomposition of capitalism").

Obviously, as soon as the Eastern bloc's collapse became clear, we placed this event within the framework of decomposition:

"In reality, the present collapse of the Eastern bloc is another sign of the general decomposition of capitalist society, whose origins lie precisely in the bourgeoisie's own inability to give its own answer - imperialist war - to the open crisis of the world economy" (International Review n°60, "Theses...", Point 20).

Similarly, in January 1990, we brought out the implications for the proletariat of the phase of decomposition, and of the new configuration of the imperialist arena:

"Given the world bourgeoisie's loss of control over the situation, it is not certain that its dominant sectors will today be capable of enforcing the discipline and coordination necessary for the reconstitution of military blocs (...) This is why in our analyses, we must clearly highlight the fact that while the proletarian solution - the communist revolution - is alone able to oppose the destruction of humanity (the only answer that the bourgeoisie is capable of giving to the crisis), this destruction need not necessarily be the result of a third World War. It could also come about as a logical and extreme conclusion of the process of decomposition.

(...) the continuing and worsening rot of capitalist society will have still worse effects on class consciousness than during the 1980s. It weighs down the whole of society with a general feeling of despair; the putrid stink of rotting bourgeois ideology poisons the very air that the proletariat breathes. Right up to the pre-revolutionary period, this will sow further difficulties in the way of the development of class consciousness" (International Review n°61, "After the collapse of the Eastern bloc, destabilisation and chaos").

Our analysis of decomposition thus allows us to highlight the extreme gravity of what is at stake in the present historic situation. In particular, it leads us to underline that the proletariat's road towards the communist revolution will be much more difficult that revolutionaries thought in the past. This is another lesson that we must draw from the ICC's experience during the last ten years, and one which recalls Marx's concern last century: that revolutionaries do not have the vocation of consoling the working class, but on the contrary of emphasizing both the absolute necessity and the difficulty of its historic combat. Only with a clear consciousness of this difficulty will the proletariat (and the revolutionaries with it) be able to avoid discouragement in adversity, and find the strength and lucidity to overcome the barriers on the road to the overthrow of this society of exploitation (6).

In this evaluation of the ICC's last ten years, we cannot overlook two important elements of our organisational life.

The first is very positive: it is the extension of the ICC's territorial presence, with the formation in 1989 of a nucleus in India, which publishes Communist Internationalist in Hindi, and of a new section, with its publication Revolucion Mundial, in Mexico, a country of the greatest importance in Latin America.

The second fact is much sadder: it is the death of our comrade Marc, on 20th December 1990. We will not here go back over the vital part he played in the formation of the ICC, and before that in the combat of the left communist fractions during the darkest hours of the counter-revolution. A long article (International Review n°65-66) has already dealt with this. Let us say simply that, while the convulsions of world capitalism since 1989 have been a "test of fire" for the ICC, as for the milieu as a whole, the loss of our comrade has been for us another "test of fire". Many groups of the communist life did not survive the death of their main inspirer. This was the case for the FOR, for example. Some "friends" have also predicted, with deep "concern", that the ICC would not survive without Marc. And yet, the ICC is still there, and it has held its course for four years despite the storms it has encountered.

Here again, we do not ascribe any particular merit to ourselves: the revolutionary organisation does not exist thanks to any one of its militants, however valorous. It is the historic product of the proletariat, and if it fails to survive one of its militants then this is because it has failed to take up correctly the responsibility that the class has given it, and because the militant has himself, in a certain sense, failed. If the ICC has been successful in surmounting the tests it has encountered, this is above all because it has always had the concern to attach itself to the experience of the communist organisations that preceded it, and to see its role as a long term combat rather than one in view of any immediate "success". Since the last century, this has been the approach of the clearest and most solid revolutionary militants: we look back to them, and in large part is our comrade Marc who taught us to do so. He also taught us, by his example, the meaning of militant devotion, without which a revolutionary organisation cannot survive, however clear it may be:

"His greatest pride lay not in the exceptional contribution he made, but in the fact that he had remained faithful in all his being to the combat of the proletariat. This too, is a precious lesson to the new generations of militants who have never had the opportunity to experience the immense devotion to the revolutionary cause of past generations. It is on this level, above all, that we hope to rise to the combat. Though now without his presence, vigilant and clear-sighted, warm and passionate, we are determined to continue" (International Review n°66, "Marc").

Twenty years after the formation of the ICC, we continue the combat.

FM

1) The fact that today we are publishing Interntional Review no 80 shows that it has maintained an unbroken regularity.

2) In the early 80s, the PCI-Programma renamed its publication to Combat. Combat slid rapidly towards leftism. Since then, some elements of the group have renewed the publication of Programma Comunista, which defends classic Bordigist positions.

3) On this subject, see the articles published in International Review n°41 and 45.

4) It should be said that almost all the groups of the proletarian milieu completely failed to understand the events of 1989, as we showed in the articles "The wind from the East and the response of revolutionaries", and "Faced with the upheavals in the East, a vanguard that came late", in International Review n°61-62. The prize goes without any doubt to the EFICC (which had left the ICC on the grounds that the latter was degenerating and incapable of carrying out any theoretical work): the EFICC took TWO YEARS to realise that the Eastern bloc had disappeared (see the article "What use is the EFICC?", in International Review n°70).

5) We have given an account of these events in International Review n°64-65. In particular, even before "Desert Storm", we wrote: "In the new historical period which we have entered, and which the Gulf events have confirmed, the world appears as a vast free-for-all, where the tendency of "every man for himself" will operate to the full, and where the alliances between states will be far from having the stability that characterised the imperialist blocs, but will be dominated by the immediate needs of the moment. A world of bloody chaos, where the American policeman will try to maintain a minimum of order by the increasingly massive and brutal use of military force" ("Militarism and Decomposition", International Review n°64). Similarly, we rejected the idea put about by the leftists, but shared by most of the groups of the proletarian milieu, that the war in the Gulf was a "war for oil" (see "The proletarian political milieu faced with the Gulf war).

6) It is not necessary here to go back over our analysis of decomposition at greater length. It appears in all our texts dealing with the international situation. Let us just add that, through a debate in depth throughout the organisation, this analysis has been made progressively more precise (on this subject, see our texts "Decomposition, the ultimate phase of capitalist decadence", "Militarism and Decomposition", and "Towards the greatest chaos in history", published in International Review n°62, 64, and 68 respectively).

Site structure:

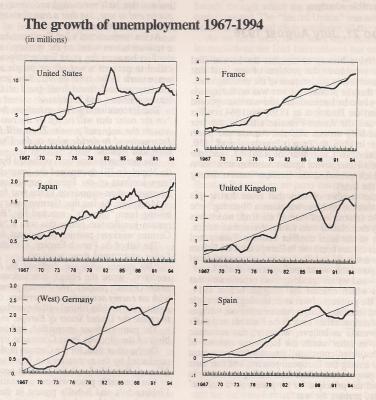

25 years of growing unemployment

- 2994 reads

For a quarter of a century, since the end of the 1960s, the scourge of unemployment has continued to extend and intensify throughout the world. This development has been more or less regular, going through more or less violent accelerations and refluxes. But the general upward tendency has been confirmed in recession after recession.

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [2]

- Unemployment [3]

Economic Crisis: A "Recovery" Without Jobs

- 2742 reads

Apparently all the economic statistics are clear: the world economy is finally coming out of the worst recession since the war. Production is increasing, profits are returning. The medicine seems to have worked. And yet no government dares cry victory, all of them are calling for still further sacrifices, all remain extremely prudent, and above all, every one of them says that as far as unemployment is concerned - ie the main issue - there's not a great deal to look forward to[1].

But what kind of recovery is it that doesn't create jobs or only creates precarious ones?

During the last two years, in the Anglo-Saxon countries, which are supposed to be the first to have come out of the open recession which began at the end of the 80s, the 'recovery' has essentially taken the form of an extreme modernization of the productive apparatus in enterprises which survived the disaster. Those who did survive did so at the price of violent restructurations, resulting in massive lay-offs and no less massive expenditure on replacing living labor with dead labor, with machines. The increase in production noted by the statistics in recent months is essentially the result not of an increase in the number of workers reintegrated into employment but of a greater productivity on the part of those who have kept their jobs. This increase in productivity, which for example accounts for 80 % of the rise in production in Canada, one of the countries who have advanced the furthest into the 'recovery', is mainly due to very high investment into the modernization of machinery and communications, into the development of automation - not into the opening of new factories. In the USA it's this investment into equipment, principally computers, which explains the growth of investment in recent years. Investment in non-residential building is virtually stagnant. Which means that existing factories are being modernized but new ones aren't being built.

A Mickey Mouse recovery

In Britain today, while the govermnent never stops singing about the continual fall in unemployment, nearly 6 million people are working an average 14.8 hours a week. It's these kind of precarious and poorly paid jobs which are swelling the employment statistics. The British workers call them "Micky Mouse jobs".

Meanwhile the program of restructuring the big enterprises continues: 1,000 jobs cut in one of Britain's main electricity companies; 2,500 in the second largest telephone company.

In France, the Society Nationale des Chemins de Fer (railways) have announced 4,800 job-cuts for 1995; Renault 1,735, Citroen 1,180. In Germany, the giant Siemens company has announced that it will cut "at least" 12,000 jobs in 1994-5, after the 21,000 already gone in 1993.

The lack of markets

For each enterprise, increasing productivity is a precondition for survival. Globally speaking, this ruthless competition leads to important gains in productivity. But this poses the problem of the existence of sufficient markets to absorb the growing amount of production that the enterprises can ensure with the same number of workers. If the markets are insufficient, job-cuts are inevitable.

"We have to raise productivity by 5 or 6% per year, and as long as the market doesn't progress more quickly, jobs will go". This is how the French car bosses summed up their situation at the end of 1994[2].

Public Debt

How can the market be made to "progress"? In International Review 78 we showed how, in the face of the open recession since the end of the 80s, governments have resorted massively to public debt.

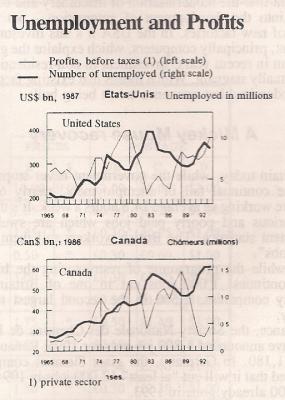

This debt has made it possible to finance the expenditure which helps create 'solvent' markets for an economy which is cruelly lacking in such things because it can't create them spontaneously. The spiraling growth in the debts of the main industrial countries is part of the basis for the re-establishment of profits[3].

Public debt allows 'idle' capital, which finds it harder and harder to find profitable emplacements, to function as state bonds, assured of convenient and reliable returns. The capitalist can extract his surplus value not from his own management of capital, but from the work of the state which levies taxes[4].

The mechanism of the public debt takes the form of a transfer of values from part of the capitalists and workers to the holders of state bonds, a transfer which follows the path of taxes then of interest drawn from the debt. This is what Marx called "fictitious capital" .

The stimulating effects of public debt are risky, but the dangers it accumulates for the future are guaranteed (see 'New financial storms ahead' in International Review no 78). The present 'recovery' will be very expensive tomorrow on the financial level.

For the proletarians, this means that on top of the intensification of exploitation at the workplace, taxation will get heavier and heavier. The state has to levy a growing mass of taxes to reimburse capital and the interests on the debt.

Destroying capital to maintain its profitability

When the capitalist economy is functioning in a healthy manner, the increase or maintenance of profits is the result of the growth in the number of workers exploited and the capacity to extract a greater mass of surplus value from them. When it is suffering from a chronic illness, despite the reinforcement of exploitation and productivity, the lack of markets prevents it from maintaining its profits without reducing the number of workers to exploit, without destroying capital.

Although capitalism draws its profits from the exploitation of labor, it finds itself in the 'absurd' situation of having to pay the unemployed, workers who are not working, as well as having to pay peasants not to produce, to leave their fields lying fallow.

The social costs of ‘maintaining incomes' have reached up to 10% of the annual production of certain industrial countries. From capital's point of this is a mortal sin, an aberration, pure waste, the destruction of capital. With all the sincerity of a convinced capitalist, the new Republican spokesman of the House of Representatives, Newt Gingrich, went on the warpath against all "the government aid to the poor".

But capital's point of view is that of a senile system, which is destroying itself in convulsions that are dragging the world into endless barbarism and despair. The aberration is not that the bourgeois state throws a few crumbs to people who aren't working, but the fact that there are people who can't play a part in the productive process at a time when the cancer of material poverty is spreading all over the planet.

It's capitalism that has become a historical aberration. The current 'recovery' without jobs is further confirmation of this. The only real 'medicine' for the economic organization of society is the destruction of capitalism itself, the inauguration of a society where the objective of production is no longer profit, the return on capital, but the pure and simple satisfaction of human needs.

**********

"It goes without saying that political economy only considers the proletarian as a worker: he is the one who having neither capital nor ground rent, lives solely by his labor, by an abstract and monotonous labor. It can thus affirm that, just like a beast of burden; the proletarian deserves to earn enough to be able to work. When he is no longer working, political economy no longer considers him to lie a human being; it abandons this consideration to criminal justice, to the doctors, to religion, to statistics, to politics, to public charity" (Marx, Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy).

[1] The official predictions of the OECD announce a diminution in the rate of unemployment in 1995 and 1996. But the level of these reductions is miniscule: 0.3% in Italy (unemployment officially stands at 11.3% in 1994; by 1996 it is supposed to go down to 11 %); 0.5% in the USA (from 6.1 % in 94 to 5.6 % in

96); 0.7% in Western Europe generally (from 11.6% to 10.9%). In Japan no reduction is in sight.

[2] Liberation, 16.12.94

[3] Between 1989 and 1994, the public debt, measured as a percentage of gross national production, went from 53 to 65 % in the USA, from 57 to 73 % in Europe; in 1994, this percentage reached 123 in Italy, 142 in Belgium.

[4] This evolution of the ruling class into a parasitic body that lives off its state is typical of decadent societies. In the late Roman Empire as in decadent feudalism this phenomenon was one of the main factors in the massive development of corruption.

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [2]

- Unemployment [3]

Imperialist Conflicts: Each against All

- 2676 reads

The anarchy and chaos which today characterizes the relations between fractions of the bourgeoisie, in particular at the international level, is not only the product of the earthquake represented by the collapse of the eastern bloc. This collapse, which is still taking its course as can be seen by the present events in the Caucasus, is itself the manifestation of a deeper reality, the same reality that explains the war in ex-Yugoslavia, or the fact that 900,000 Rwandans are rotting in refugee camps in Zaire: the advanced decadence of capitalism, its decomposition as a social system.

When a social system enters into its phase of decadence, that is to say when the social relations of production which characterize it become obsolete, no longer adapted to the possibilities and necessities of society, the very basis for the profits and privileges of the ruling class is reduced, made more fragile. The cohesion of the ruling class then tends to disintegrate into an infinite number of conflicting interests. Like hungry beasts who can only survive at the expense of others, more and more fractions of the class in power start tearing each other apart, devastating the civilization they once helped to build. Just as the numerous armies of decadent Rome ruined what was left of a decomposing Empire with their incessant conflicts, just as the feudal lords of the late Middle Ages destroyed whole harvests with their permanent local conflicts, so the imperialist powers of our century have made humanity go through the worst destructions in its history. The means and dimensions of the drama have changed. Catapults made of wood and animal skins have given way to guided missiles, and the battlefield has assumed the dimensions of the entire planet. But the nature of the phenomenon is the same. Society is destroying itself in an indescribable chaos, the prisoner of economic and social relations that have become too narrow ... Today, however, the very survival of humanity is at stake.

The forces of disintegration at work

To measure the reality of the chaos that now dominates international relations, we can distinguish two points of departure. On the one hand there is the general, 'ordinary', omnipresent chaos which is spreading everywhere; on the other hand, within all this, there are more important antagonisms, expressing the tendency towards the reconstitution of blocs or alliances and indicating the most decisive lines of force: this is the case with the antagonism between the former bloc leader, the USA, and a reunified Germany which is the candidate for the role of leader of a new bloc.

Ordinary chaos

The more the governments organize international meetings and summits between the statesmen of the big powers, the more the divisions between them break out into the open. The international organizations, whether it's the UN, NATO, the Western European Union or others, appear more and more as grotesque and impotent masquerades where the only thing that outdoes hypocrisy is cynicism. The media lament the 'misunderstandings' between the member countries, the 'differences in method' which are paralyzing these temples to the 'concert of nations'. But the reality of international relations is the reign of each against all. Each country is constantly caught between the necessity to defend its interests against those of others, which implies a proliferation of antagonisms with other countries, and, at the same time, the necessity for alliances that will enable it to survive in an ever more irrational and ruthless war. The fact that millions of victims pay for these antagonisms every year, all over the planet, does not halt this game of massacre between national capitals, and above all between the great powers.

The last months of 1994 have been rich in new manifestations of this frenetic chaos in which alliances are made and unmade against a background of ever-increasing instability.

The most tangible sign of the depth and importance of this instability today is the current evolution of the relations between the USA and Britain. What was once an unchanging point of reference in international relations is now going through its most difficult moments since the Suez crisis of 1956. The Economist, in its annual supplement, has talked of a "fading friendship". A report by the Pentagon goes along the same lines, accusing France of fuelling the war in Yugoslavia in order to poison relations between the USA and Britain.

During an ordinary summit at Chartres, in October 1994, Britain and France decided to set up a "group of combined aerial forces" and to work together towards an inter-African intervention force that would serve to "keep the peace" in English and French speaking Africa. The British no longer see the Western European Union as a "French submarine within NATO", and the journalists insist on the strength represented by this alliance between the only two nuclear powers in Europe.

Thus, Britain is moving further and further away from the USA; in order to defend its own interests, it is tending to adopt policies that are openly opposed to the USA, as we can see in Africa and above all in the Balkans.

The American-Russian alliance, that other pillar of the construction of the "new world order" has also been put to a

severe test. The question of the enlarging of NATO towards countries that were once part of the USSR's bloc (what Russia calls its "nearby abroad"), in particular Poland and the Czech republic, has more and more become a major bone of contention between the two powers. "No third country can dictate the conditions for enlarging NATO", as an American official dryly declared in the face of Russian protests.

The Franco-German axis, the spinal column of the European Union, has also been put into question: "We are light years from the German position" declared a French official, summarizing France's opposition to any "communitarianisation" of the foreign and security policies of the European Union. France fears that Europe will become a "German super-state". At the same time, Germany is nervous about a Franco-British alliance in 1995 against the prospect of a German-dominated federal Europe, an alliance that would have the sole purpose of countering Bonn's hegemonic ambitions.

Today the cohesion of the great blocs of the cold war seems like a distant memory of unity and order; the 'concert of nations' has become a barbaric cacophony. A cacophony whose face is that of the 500,000 victims of genocide in Rwanda, of the millions of corpses bloodying the planet from Cambodia to Angola, from Mexico to Afghanistan.

In this same process of disintegration, the break-up of the ex-USSR has not yet run its course. The Russian Federation, which sought to be the last bulwark against the centrifugal forces that had carried off the old empire, finds itself confronted with these same forces within itself, as well as in Moldova, Tadjikstan, Georgia, Abkhazia, Tatarstan ... the massive intervention of the Russian army in Chechnya[1] expresses the will of a part of the Russian ruling class to put an end to these tendencies which are continuing to dislocate what was, five years ago, the most

extensive imperialist power on the planet.

But decomposition has reached such a level in the ex-USSR that this operation aimed at 'restoring order' is turning into a new source of internal chaos.

On the ground, the resistance to Russian intervention has been more violent and 'popular' than was foreseen. In an atmosphere of nationalist and anti-Russian hysteria within the population, the president of Chechnya, Dudayev, launched an appeal in the face of the Russian army advance, declaring that "the earth under their feet must bum! It's a war to the death!". The president of the Russian republic of Ingushia, another Caucasian

republic close to Chechnya, announced the threat of the extension of the conflict, proclaiming that "the war for the Caucasus has begun!"

From the start, the Russians met with fierce resistance which cost them dear in men and materials.

But this operation has also led to new fractures within the Russian ruling class itself, which is already well-rotted. At the battle front, right at the beginning, one of the Russian generals (Ivan Babichev) refused to advance on the capital Grozny and fraternized with the Chechen population: "It is not our fault that we are here. This operation contradicts the Constitution. It is forbidden to use the army against the people". At the time of writing, several other generals on the ground have rallied to this protest.

In Moscow the divisions are also dramatic. "In Russia today there are two Chechen conflicts, one in the Caucasus, and another, more dangerous one in Moscow" declared Emile Paine, one of Yeltsin's advisers. A number of 'celebrated' military figures have stood against the intervention, as well as Yeltsin's former prime minister, Egor Gaidar, and Gorbachev ...

For President Clinton the crisis in Chechnya is an "internal problem" and for Willy Claes, the general secretary of NATO, it's an "inside business". "It's not in the interest of the USA and certainly not of the Russians to have a Russia that is going towards disintegration" declared Warren Christopher on TV, on 14 December, showing the profound disquiet of the American bourgeoisie towards the problems of its ally.

But the problem is not so "internal" as one might be led to believe. On the one hand because Chechnya has a certain sympathy from foreign forces, in particular neighboring Turkey and, probably, from Germany. On the other hand because this situation is only a spectacular expression of a world-wide process.

This dramatic putrefaction of the situation in Russia is not simply, as liberal speechmakers would have it, the consequence of the damage done by Stalinism (fraudulently identified with communism); it is not a specificity of Eastern Europe. Russia is just one of the places where the generalized decomposition of world capitalism is most advanced.

The tendencies towards the reconstitution of blocs

A universe of imperialist brigands cannot exist without there being a tendency towards the constitution of gangs and gang leaders. The multiple conflicts between capitalist nations inevitably tend to structure themselves in line with the antagonisms between the most powerful ones. And, among these, the one between the two main bosses stamps its imprint on all the others: the opposition between the USA and a reunified Germany, between the former chief of the western bloc and the only serious pretender to the leadership of a new bloc. This conflict runs

through the political life of numerous countries.

For example: the summit of the Islamic Conference held in Casablanca in December 1994 could not avoid becoming a clash between the Islamic countries allied to the USA and those allied to Europe. From the beginning, the camp led by Hassan II of Morocco (the recognized spearhead of American diplomacy) and Egypt's Mubarak (the country in the world which, next to Israel, receives the most aid from America) made an attack on " certain Islamic states" which support terrorists and which have "sold their souls to the Devil" , ie to Iran and Sudan, whose links with European powers are well-known.

In Turkey, at the end of November 94, the minister of foreign affairs, the social-democrat Soysal, who is somewhat pro-European and anti-American, resigned from the government.

In Mexico, in the state of Chiapas where the Zapatistas are to be found, there are two governors: one from the PRI, the government party since 1929 which has always worked as a solid ally of the 'Yankee' big brother despite using an 'anti-imperialist' rhetoric; the other, Avendano, the governor allied to the Zapatistas, who refuses to recognize the election of the PRI candidate due to frauds, and who controls a third of the province's municipalities. The latter has declared that only Europe can give him the necessary support for him to triumph.

In Europe itself, the question of the choice between the American option and the Germano-European one has rent the ruling classes. In Britain, within the party in power, there's been a set-to illustrated recently by the fact that the 'Euro-skeptics' practically put Major in a minority in the House of Commons on the question of contributions to the European Union. Major even envisaged the possibility of a referendum on the question.

In Italy, a country that was long considered to be "America's aircraft carrier in Europe", but also as one of the pillars of the European Union, the war between the two camps has torn the political class apart, even if what's really at stake is usually kept hidden. However, Carlo de Benedetti, one of the main figures amongst the national bosses, did not hesitate to attack the pro-American Berlusconi government in explicit terms: "Italy is distancing itself from Europe and entering into a spiral of destruction". It's this basic antagonism which is at the root of the

country's current governmental instability.

In France's political class, now in the midst of a presidential election campaign, there are also profound divisions over this question, particularly in the parties of the governmental majority.

Because they are not faced with a choice of this kind, only the German and American bourgeoisies seem to be somewhat coherent at the level of their international policy, even if this is not without its difficulties.

*****

Since the collapse of the USSR, Germany has made many advances on the international level: apart from its reunification, it has developed with some assurance its spheres of influence among the countries of central Europe, former members of the eastern bloc; it has intensified its links with countries as strategically important as Turkey, Iran or Malaysia; it has carried on building and enlarging the European Union, integrating new countries that are particularly close to it, such as Austria; in ex-Yugoslavia, it has imposed the international recognition of

its allies Slovenia and Croatia, which has opened up its access to the Mediterranean. The new reunified Germany has thus unequivocally affirmed that it is the only credible candidate for forming a new bloc opposed to that of the USA.

America's international policy has consisted of an offensive which has two main objectives: on the one hand, to preserve the dominant position of American capital; on the other hand, to systematically destroy the positions of its new European rivals.

The USA has been reaffirming its position as number one power by resorting to spectacular military operations, which often compel its former allies to line up behind it (Gulf war of 91, intervention in Somalia, invasion of Haiti, new operation in the Gulf in 94, etc); by keeping alive the international organisms formed at the end of the second world war to ensure its control over its allies, such as NATO, although the main targets of this tactic have not been taken in ("More than ever, the USA wants to make NATO an appendage of the State department and of Washington ". as a French diplomat declared recently[2]; by consolidating and fortifying its closest spheres of influence by creating 'free trade areas' such as NAFTA, which regroups the USA, Canada and Mexico, or the plan for areas regrouping the whole Pacific zone or the entire American continent (during December 94 Clinton convened two spectacular summits, first in Malaysia then in Miami, to get these projects off the ground).