International Review no.41 - 2nd quarter 1985

- 3427 reads

What point has the crisis reached? - The dollar: the emperor has no clothes

- 2224 reads

In the epoch of computers, of communication by satellite, information circulates at the speed of light around the globe, and exchange likewise. A few telephone calls, and billions of dollars have changed hands. Fortunes are made or lost in the space of a few minutes. The dollar continues its frenzied spree across the planet in an incessant movement: from New York to Chicago, from Chicago to Tokyo, from Tokyo to Hong-Kong, to Zurich, Paris, London...each financial centre serves as a sounding board for the others in maintaining the incessant movement of capital.

The rise of speculation

The dollar is the world currency par excellence; over 80% of world trade is conducted with dollars. Fluctuations of the dollar’s course affect the entire world economy. And the dollar’s course is anything but stable: over January and February1985 the dollar has continued its blazing, soaring ascent, at first by centimes a week in relation to the French franc, and accelerating its movement by 10 centimes a day subsequently. On February 27, after the alarmist declarations of Volcker, president of the American Federal Bank, and the intervention of the big central banks, there was a slithering drop. In the space of a few minutes the dollar shifted, in relation to the French franc, from 10.61 to 10.10 only to rise to 10.20FF : 40 centimes of a loss vis-a-vis the franc, a 5% devaluation vis-a-vis the German mark. In this way more than 10 billion dollars went up in smoke on the world market. Already, in September ‘84, the dollar went down by 40 centimes in one day, but that didn’t stop it resuming its ascent subsequently under the pressure of international speculation.

Why the dollar is soaring?

The economists are at a loss. And so, Otto Pohl, governor of the West German Federal Bank, at a symposium of the top nobs of international finance, remarked ironically: “The dollar is miraculous, and on this point our vision is confused, but after discussion we will be confused at a higher level.” Not very reassuring for the world economy.

What’s so miraculous about the present ‘health’ of the dollar in relation to other currencies? Simply that the present rise of the dollar’s course does not at all correspond to the economic reality of the competitiveness of American capital in relation to its competitors. The dollar is enormously overvalued.

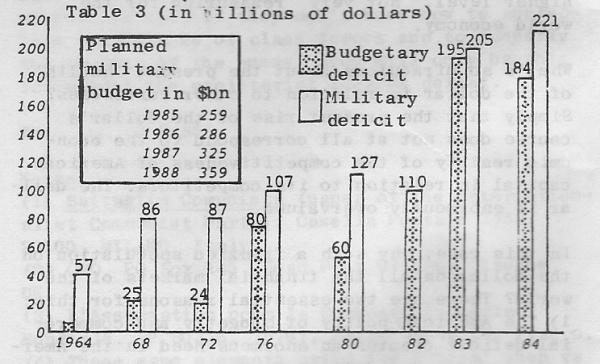

In this case, why such a frenzied speculation on the dollar on all the financial markets of the world? There are two essential reasons for this: 1) The American policy of budgetary and commercial deficit creates an enormous need in the American economy for dollars to cover this. The budgetary deficit reached $195bn in 1983 and $184bn in 1984 (see table 3) and the commercial deficit amounted to $123.3bn in 1984. And this deficit is not shrinking, as table 1 shows.

TABLE I (in billions of dollars) | ||

| Commercial deficit | Budgetary deficit |

January 1984 | 9.5 | 5.62 |

January 1985 | 10.3 | 6.38 |

And the timid propositions to reduce the budgetary deficit announced by Washington since December1984 aren’t going to put a brake on this tendency. On the contrary, they will merely pressure speculators and push the dollar up even further. Which is effectively what is happening. 2) The USA is the leading world economic power, the fortress of international capital. With the recovery slowing up and the risk of recession looming on the horizon, the capital of the entire world flocks to the USA in order to try and save itself from the threatening reflux. The present movement of speculation is the sign of the worried state of international finance.

Indebtedness: A time bomb at the heart of world economy

In order to cover its deficits, the USA goes into debt. The US cannot make too much use of the printing press for fear of triggering off an uncontrollable inflationary process. Instead it draws in foreign capital. But as Volcker says: “The United States cannot live indefinitely beyond its means thanks to foreign capital.” And indeed, the present indebtedness is phenomenal.

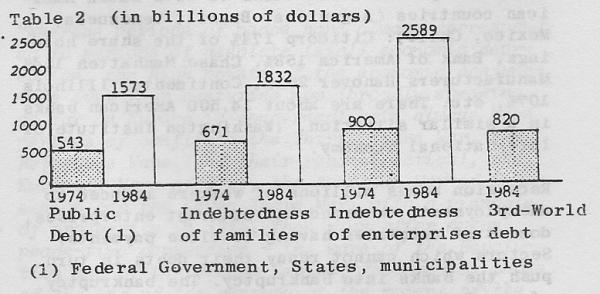

The total debt of the USA is $6000bn. Such dizzying figure lose their meaning - a 6 followed by 12 noughts! That amounts to two years of the production of the USA, six of Japan, ten of Germany!

The public debt, which is alone $1500bn, required the payment of around $100bn interest in 1984, and the services on debts will surpass $214bn in 1989. At this rate the USA will become a debtor in relation to the rest of the world in 1985.

For any of the underdeveloped countries, such a situation would be catastrophic. The IMF would intervene urgently to impose a draconian austerity plan. This shows that the present strength of the dollar is a gigantic cheat of economic laws. The USA profits from its economic and military strength in order to impose its law on the world via the dollar - its national currency but at the same time the principal international exchange currency.

Do the economic laws no longer play their role? Is the dollar dodging all the rules? Is its ascent unstoppable and inevitable? Certainly not. The policies of state capitalism can postpone the day of reckoning of the crisis through monetary policies, but this only pushes the contradictions to a higher, more explosive level.

The declarations of Volcker which provoked the fall of the dollar’s course on February 27th are unambiguous on this point. He himself, having a year ago declared that the foreign debt was “a pistol pointing to the heart of the United States” followed this up by saying that “in view of the extent of the budgetary deficit, the swelling of American borrowing abroad contains the seeds of its own destruction”, and he added the precision in relation to the course of the dollar “I can’t predict when but the scenario is in place.”

The recession looming on the horizon

The growth of the American economy, which was very marked in the spring of 1984, has slowed up these last months. Orders from industry have slowed down: August - 1.7%, September - 4.3%, October - 4.7%, December - 2.7%. The growth of GNP, which reached 7.1% in the spring, was only 1.9% by the third quarter of 1984.

The American deficit no longer suffices, despite its importance, to maintain the world mini-recovery, the effects of which anyway mainly touched the USA while Europe was stagnating. The specter of recession is looming on the horizon, and this perspective cannot but stir up the horror of the capitalist financiers.

All the big American banks have lent out enormous sums, up to ten times their real resources. For example, to mention simply the commitment of the principal American banks to five Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico, Chile): Citicorp 174% of the share holdings, Bank of America 158%, Chase Manhattan 154%, Manufacturers Hanover 262%, Continental Illinois 107%, etc. There are about 14,500 American banks in a similar situation. (Washington Institute of International Economy)

Recession means millions of workers reduced to unemployment, thousands of bankrupt enterprises, dozens of countries having to close payments. Sectors which cannot repay their debts in turn push the banks into bankruptcy. The bankruptcy of the Continental Illinois could only be averted by injecting a further $8bn thanks to the aid of other banks and of the American state. But what’s coming up on the horizon will not be so easy to absorb. What is in the making is the bankruptcy of the international financial system, with the dollar at the heart of this bankruptcy.

A brief recession of only six months would increase the federal deficit from $200bn to $500bn, according to a study by Chase Econometrics. In the face of such a situation, the USA would haveno other choice but to cover this deficit through a massive recourse to printing money, since the capital of the entire world would no longer suffice, thereby relaunching the galloping inflationary spiral which Reagan puffs himself up about having vanquished. Such a situation could only provoke a panic on the financial markets, leading to a return to speculative tendencies, this time acting against the dollar, plunging the world economy into the throes of a recession the like of which it has never known before, and all this going hand in hand with hyperinflation.

That is the scenario which Volcker was talking about. It is a catastrophic scenario. The American government is trying to utilize each and every artifice in order to hold back this day of reckoning: suppression of orders at their source, the internationalization of the yen, Reagan’s appeals to the Europeans to put themselves more in debt in order to support the American effort and maintain economic activity. But all these expediencies are not enough, and the present headlong flight can only show the impasse of world capitalism and announce the future catastrophe.

What are the consequences for the working class?

The Reaganite recovery is essentially limited to the USA where the rate of unemployment fell by 2.45%. In 1984, in contrast, for the entirety of the underdeveloped countries, there was a plunge into a bottomless misery, a situation of famine such as in Ethiopia or Brazil, whereas in Europe the relative maintenance of the economy hasn’t prevented an increase in unemployment: 2.5% in 1984 in the EEC. With the let-up of the recovery, these last months have seen an upsurge of unemployment: 600,000 more unemployed for the EEC in January 1985, 300,000 alone for West Germany, which, with this progression, has beaten its record of 1953 with 2.62 million unemployed. The perspective of the recession implies an explosion of unemployment and a descent into a Third-Worldlike misery at the heart of industrial capitalism. The complete collapse of the illusion in the possibility of an economic recovery will show the impasse of capitalism to the entire world proletariat. This poses all the more the necessity to put forward a revolutionary perspective as the sole means of survival for humanity, since capitalism is heading for its destruction.

World capitalism is in an economic impasse, on the edge of the cliff, and the bourgeoisie itself is beginning to take account of this. It is pushed more and more from the economic terrain towards the military level in a headlong flight towards economic catastrophe.

The American budgetary deficit goes essentially to finance its war effort in which gigantic sums of capital are engulfed and sterilized (see table 3).

In January 1985 orders in durable goods increased by 3.8% in the USA. But if we take away military orders, there was in fact a drop of 11.5% of incoming orders. Behind the accelerated nose-dive in the economic crisis which is shaping up is the exacerbation and acceleration of inter-imperialist tensions, the mad rush of the bourgeoisie towards war. Capitalism no longer has a future to offer humanity. The last illusions in its capacity to find a way out, through a hypothetical technological revolution, are being dashed against the reality of bankruptcy.

President Reagan will certainly not go down in history as the matador who conquered the crisis, but as the president of the biggest economic crisis that capitalism has ever known. The reckoning of a reverse has begun; the recession cannot be averted. This recession will signify a new acceleration of tensions, a deepening of class antagonisms. On the capacity of the proletariat to develop its struggles, to put forward a revolutionary perspective, depends the future of humanity. Capitalism is heading towards bankruptcy and the whole of humanity risks being wiped out in a new nuclear holocaust.

The dollar is still the dollar-emperor ruling the entire world economy. But the emperor is naked and this fact will soon pierce the smokescreen for capitalist propaganda.

JJ 2.3.85

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [1]

Internal debate: The ICC and the politics of the "lesser evil"

- 2293 reads

In IR 40 we printed an article called ‘The Danger of Councilism' which defends the position the ICC has reached after more than a year of debate. In this debate, the ICC on the one hand reaffirmed that the perspectives of the proletarian struggle demand a clear rejection of the erroneous conceptions of ‘substitutionism' (the conception that the party is the unique repository of consciousness, leading to the conception of the dictatorship of the party) and ‘councilism' (the conception of consciousness as a simple reflection of immediate struggles, leading to the minimization of the function of the party and the negation of its necessity). On the other hand, the ICC was led to state precisely why, under the conditions of our period, the weaknesses and errors of a ‘councilist' type constitute a greater obstacle, a ‘greater danger', than the errors and conceptions of ‘substitutionism'. The ICC has not hesitated to systematize and refine its positions on consciousness, councilism, centrism, intervention, etc, by freeing them from any imprecisions and confused interpretations. But while the ICC sees this orientation as a way to place its positions on a terrain more firmly attached to the basis of marxism and at the same time to make them more able to deal with the questions raised by the acceleration of history, the article we are printing below sees this as a "new orientation", the acceptance of a theory of the "Lesser of two evils". It expresses the position of' minority comrades who have formed a tendency within the ICC. We can only regret that the article poses many questions without, in our opinion, trying to respond to the arrumentation of the article criticized. From our point of view, it expresses a centrist tendency in relation to councilism, because although it platonically asserts the danger of ‘councilism', it basically attenuates councilism's danger and only offers as a ‘perspective' that ... all errors are dangerous for the proletariat. We shall answer the different points raised in this article in the next issue of the Review.

ICC

*********************

In IR 40 is an article called ‘The Danger of Councilism' defending the new orientation of the ICC. According to this new theory, councilism is today, and will be in the future, the greatest danger for the working class and its revolutionary minorities, a greater danger than substitutionism. In this article we wish to express the position of a minority of comrades in the ICC who do not agree with this new orientation.

There is no question that councilist positions are a danger; they have been in the past and will be in the future. Councilism - the rejection of the need for the organization of revolutionaries, the party and its active and decisive role in the working class' coming to consciousness - is, as the ICC has always said, a danger, particularly for the revolutionary political milieu including the ICC, because the end result of such a theorization is to deprive the working class of its indispensable instrument.

The divergence is not on whether councilism represents a danger but:

a) over the new unilateral theory of councilism, the greatest danger;

- because it is accompanied by a dismissal of substitutionism as "a lesser danger";

- because it turns its back on the essential danger for the proletariat coming from the capitalist state and its extensions in the working class (the left parties, leftists, rank and file unionism etc, the mechanism of capitalist recuperation in the era of state capitalism) and focuses instead on a so-called inherent councilist defect of the "proletariat of the advanced countries";

- because it can only lead and is already leading to serious regressions on the meaning of the lessons drawn from the first revolutionary wave and from the workers' movement in general in the period of decadence;

b) on the implications of this theory on the understanding of the development of class consciousness: tending to reduce class consciousness to "theory and program" (IR 40) and the role of the class to assimilation of the program;

c) on a theory of "centrism/opportunism" which claims that "hesitation" and "lack of will" are the permanent ills of the working class movement; in the name of this theory, political parties and elements which definitively betrayed the proletariat are now put back into it, blurring class lines.

In this article, we shall only deal with the first aspect: the theory of councilism, the greatest danger. Discussion will continue on centrism and class consciousness in other articles to appear soon in our press.

Councilism, the greatest danger?

The article in IR 40 develops the following argumentation:

- the danger of substitutionism exists only in periods of reflux in a revolutionary wave;

- the danger of councilism is, on the contrary, "a much greater danger, especially in periods of a rising revolutionary wave";

- substitutionism can only find a fertile field in underdeveloped countries; councilist-type reactions are more characteristic of the workers in advanced like the workers in Germany during the first revolutionary wave;

- substitutionism is an "error", a "unique phenomenon ... of the geographic isolation of a revolution in only one country, an objective factor of substitutionism which is no longer possible." (IR 40)

********************

What are these so-called "councilist reflexes" of rising class struggle, how can they be identified? According to the article they are everything from ouvrierism, localism, tail-ending, modernism, any apolitical reactions of workers, the petty-bourgeoisie, immediatism, activism and .... indecision. In short, the ills of creation. If every time the class hesitates, or falls into immediatism, if every time revolutionaries fall victim to tail-ending or fail to understand the way to form the party, it is interpreted as a manifestation of councilism, then ‘councilism' is indeed the new leviathan.

Through this trick of 'definitions', all the subjective weaknesses of the working class become councilist reflexes and the remedy is ... the party. In other words, the ICC, the proletarian political milieu and the entire working class will be protecting itself from any immediatism, petty-bourgeois influence, hesitation and so on by recognizing that the number one enemy is "underestimating", "minimizing" the party.

This whole idea of having to choose between 'under' or 'over'-estimating the party, this new variation of the politics of the lesser evil that the ICC had always rejected on a theoretical level, is being re-introduced on a practical level under the pretext of wanting to present a more "concrete" perspective to the class: we have to now agree to say to the workers that the danger of councilism is greater than that of substitutionism - otherwise the workers won't have any "perspective"!

Make your choice, comrades: if substitutionism is a danger for you, you are yourselves just councilists. If you refuse to choose sides, you are the carriers of "centrist oscillations in relation to councilism", "councilists who dare not speak their names." (IR 40)

It is claimed that "history" has proven this theory of councilism, the greatest danger. What history exactly? The ICC has always criticized in the German revolution the errors of Luxemburg and the Spartakists, the positions of the Essen tendency, of the anti-party tendency of Ruhle expelled from the KAPD in 1920 and the split of the AAUD(E) and in general, the disastrous consequences of the hesitation of the proletariat and the lack of confidence of revolutionaries in their role. Yet we have never before pretended to find the cause of this in a latent ‘councilism' of the proletariat of advanced countries. We have never tried to fit history into any cyclical theory of councilism as the greatest danger before a revolution and substitutionism only after a revolution.

Other than gratuitous assertions, the only ‘proof' offered in the article in the last issue is that "just as Luxemburg was in 1918, non-worker militants of the party will be in danger of being excluded from any possibility of speaking before the councils." And again in World Revolution 78 (December 1984): "the real danger facing the class is not that it will place ‘too much' confidence in its revolutionary minorities, but that it will deny them a hearing altogether." Here we are supposed to recognize the German proletariat's ‘councilism' against Luxemburg.

All this is a gross distortion of history. In December 1918 at the National Council of the Workers' Councils in Germany, none of the Spartakus League, workers or not, could defend their positions - not because the working class didn't allow them to but because Spartakus was a faction within the USPD.

"...to consider the fate of the Congress, we must first of all establish the relationship between the Spartacus League and the Independents. For when you read the Congress report you must certainly have wondered what had happened to the Spartakus group. You knew that some of us were there and you may have asked where were they? Or if you listened to any speeches you might have asked what were the fundamental differences between the Spartakus group and the Independents?...we were tied to the Independent faction, which hung around our necks like a millstone... which succeeded in interfering with the list of speakers and paralyzed our activities at every turn." (Levine's ‘Report on the First All-German Soviet Congress', in The Life of a Revolutionary, pp.190-192).

The revolutionary positions of Spartakus (that the councils declare themselves the supreme power, that they appeal to the world proletariat, that they support the Russian soviets, that they hear Luxemburg and Liebknecht speak on this) were presented and defended by the USPD ... which wanted to dissolve the councils in the Constituent Assembly. Spartakus (like the majority of the Communist International later on) wanted to "influence the masses" by trying to co-opt the USPD, "by seeing it as the right wing of the workers movement and not as a faction of the bourgeoisie." (IR. 2) But the ICC today, with its theory of ‘centrism', now sees the USPD, the party of Kautsky, Bernstein and Hilferding, as proletarian instead of recognizing it for what it was: an expression of the radicalization of the political apparatus of the bourgeoisie, a first expression of the phenomenon of leftism, the extreme barrier of the capitalist state against the revolutionary threat. Already in the past, it was Spartakus that got co-opted by seeing itself as an opposition within the USPD, the left- wing of social democracy, still clinging to the outmoded notion of a ‘right', ‘left' and ‘centre' in the working class. Failing to draw this lesson today is an open door to leftist recuperation.

All this has nothing to do with the myth about workers refusing to listen to revolutionaries because workers were or are councilists.

The errors of revolutionaries in the German revolution cannot be explained by an "underestimation of the role of the party." It isn't that they weren't ‘active enough' or didn't realize they had to intervene in struggle. The will to assume their role was definitely there. The tragedy was that they didn't know what to do, how to do it and with whom - in other words, what the new period of decadence meant for the communist program.

The difficulties revolutionaries faced in Germany are not attributable to a councilism of the German proletariat or its advance guard. They were fundamentally due to the general difficulty in all countries in getting free of social democracy, of its conception of the mass party and of substitutionism. At the time of the revolution, the predominant conception among revolutionaries and in the proletariat in Germany was not that the workers' councils were going to solve everything in and of themselves but that a party had to assume the power delegated by the councils. In actual fact, the councils were led to give their power to the social democracy.

How can anyone deny this obvious truth?

For the defenders of substitutionism, it's easy: when the class gave its power to the social democracy it was wrong; when it gave it to the Bolsheviks it was right. The whole thing is for the class to ‘trust' the ‘right' party. The ICC hasn't fallen into this of course. But for the ICC, turning power over to the social democracy is apparently no proof that substitutionism is a danger in the upsurge. No, according to IR 40 it was just an example of the "naivety" of the workers!

Bourgeois parties and leftists, you see, cannot be called substitutionist because they "want to deviate the struggle." It's when those who don't want to destroy the workers make a mistake that substitutionism comes into play. Thus, the same position, depending whose lips say it, can be a bourgeois position or not.

The minimization of substitutionism

In fact, unlike the position on unions and electoralism in the ascendant period of capital, substitutionism was always a bourgeois position, applying the model of the bourgeois revolution to the proletarian one. But because revolution was not yet historically possible, revolutionaries did not realize all the implications of this position. As the proletarian revolution approached, they began to feel the need for a major clarification of the program but were unable to develop all the ramifications of a new coherence. The first revolutionary wave exposed the substitutionist position on the party and all it implied about the relation of party and class for what it really is: a bourgeois position whatever the subjective intentions of those who defend it.

But for this new theory of councilism, the greatest danger in the upsurge, substitutionism is only a danger when the reflux of struggles gives strength to the counter-revolution. In other words, the counter-revolution is the greatest danger when it is already under your nose. Seeing its roots, going to the root of the matter is not necessary. First things first! First, fight ‘councilism'. Then we'll see what the proletariat can do with its parties.

The meaning and danger of substitutionism shrinks down to almost nothing. In referring to the Russian revolution the IR 40 explicitly states that before 1920 substitutionism didn't influence the degeneration of the revolution: "Only with the isolation and degeneration of the revolution did Bolshevik substitutionism become a really active element in the defeat of the class." (WR 73)

"From the pretension of directing the class in a military manner (cf. the "military discipline" proclaimed at the Second Congress), it was only one step to the conception of a dictatorship of the party, emptying the workers' councils of their real substance." (IR 40)

But the workers' councils in Russia didn't begin to be emptied of their proletarian life in 1920. On the contrary, that was the time of the last convulsions against the suffocation of the councils. The roots of this go back right to the day after the insurrection by the councils. This has always been the ICC position on the Russian revolution: "Since the seizure of' power the Bolshevik Party had entered into conflict with the unitary organs of the proletariat and presented itself as a party of government." (ICC pamphlet, Communist Organizations and Class Consciousness)

And we've shown this in many articles right from the beginning of the ICC while defending the proletarian character of October.

To say that the Bolsheviks' conceptions on the party were the cause of the degeneration is absolutely false but to assert, as the ICC apparently wants to today, that the Bolsheviks' positions did not play an active role (when they were wrong just as when they were correct) is untenable as a marxist position.

By reducing substitutionism, the ideological expression of the division of labor in class society, to a negligible quantity, the new ICC theory ends up by minimizing the danger of state capitalism, the political apparatus of the state and the mechanism of its ideological functioning.

The example of 1905, or even 1917 in Russia, is not the most telling way to predict how the bourgeoisie in the advanced countries will protect itself against revolution. The German bourgeoisie, warned after the first shock in Russia, with a more sophisticated political arsenal, was able to penetrate the councils from within not only by the industrialists who ‘negotiated' with the councils but especially through the social democracy's sabotage. The social democracy (and the Independents) far from "forbidding all parties" as the IR seems to fear as the greatest danger, accepted all of them and demanded proportional representation in the government. It even asked Spartakus to join the SPD/USPD government. To recuperate the movement, the SPD played on all the siren songs (contrary to the ‘councilism/substitutionism' divisions of the new theory): in some regions only workers could vote, in others it was the whole "population", or more representation for small factories; for and against the soldiers' councils, depending on how they went. Anything to win: recognizing and praising the councils, ouvrierism, democratism, the phraseology of the Russian revolution; anything to turn the workers from a final assault on the state. And all the while they were preparing the massacre. Spartakus itself didn't understand the radicalization of the bourgeoisie. And not one voice, even of the left clearer than Spartakus, was raised in protest from the beginning against this bourgeois vision of the relation between class and party in general.

In the future, the bourgeoisie will use anything and everything. Do we really believe that the bourgeoisie will not penetrate the councils? Or that the capitalist class is going to count on some fancied "councilist reflexes" of the workers sparing its system? Or will it simply rely on "councilist organizations" of the "petty bourgeoisie" as the IR suggests? The scenario seems to be that in a councilist fever the workers risk forbidding all parties in the councils ... and what will the bourgeoisie be doing through all this? Saying "good, at least there won't be the proletarian party there either"? Grudgingly, the IR admits that there may be base unionists in the councils. But how? As individuals? Who is behind base unionism if it isn't leftists, Stalinists and other organized political expressions? The struggle of the future won't be around forbidding parties but around which program and the need for the final assault on the state with all its tentacles.

This new theory mistakes the way the real danger for the working class - the capitalist state and all its extensions - will operate and vitiates the denunciation of substitutionism by presenting it as this ‘lesser evil'.

Today and tomorrow

It is impossible to work towards the dictatorship of the proletariat, to accelerate the process of consciousness in the class, by presenting substitutionism and anti-partyism as separate notions, one of which it is essential to understand but the other not so important. The only way to contribute is to consistently denounce the shared theoretical foundation of both substitutionism and anti-partyism and to defend a non-bourgeois vision of the relation of party and councils without concessions to any so-called lesser evils/dangers.

It is not as though the working class has never found the way to overcome the contradiction of substitutionism/anti-partyism. In the course of the revolutionary wave, the proletariat - despite its tragic defeat - was able to give expression to the political positions of the KAPD which rejected substitutionism yet reaffirmed the need for a party, offering elements towards understanding its true role. This heritage, because it was the highest point of the last wave, will be the departure point of the renaissance of tomorrow's workers' movement.

One of the greatest weaknesses of revolutionaries has always been to want to explain the slow, uneven, difficult process of the development of class consciousness throughout the whole history of the proletariat by defects in the proletariat itself (its ‘trade unionism', its ‘anarchism', its ‘councilism', its ‘integration into capitalism', etc) .

This new theory is just a reflection of a certain discouragement with the difficulty the working class has in generalizing its struggle, in asserting its own perspectives for society. This difficulty can only be overcome through the development of struggles and the experience acquired through these battles that will allow the class to rediscover its historical potential. This potential is not only the party but also the councils and communism itself. Seeing ‘councilism' in the class' difficulty in asserting itself today is just a plain mystification. The working class is no more fundamentally sapped by councilism than by Leninism or Bordigism - but it must painfully shake off all aspects of the dead weight of the counter-revolutionary period.

The proof that the weight of the errors of the counter-revolutionary period is diminishing both in relation to councilism and Bordigism (the PCI, Programma Comunista) can be seen in the decantation process that has occurred in the political milieu these past 15 years. Bourgeois ideas on substitutionism and anti-partyism have their main defend ers in the political apparatus of the ruling class (leftists, libertarians, etc) but because of the confusions of the counter-revolution, sclerotic proletarian currents have continued to defend these positions with different variations. The resurgence of proletarian struggles makes it possible to sweep away these vestigal positions whether through clarification of these groups or by their disappearance. We are not yet in a revolutionary situation where organizations defending bourgeois positions pass directly into the enemy camp but pressure from the acceleration of history, in the absence of clarification (cf. the failure of the International Conferences) leads to a decantation in the political milieu just as it leads to getting rid of illusions in the class as a whole.

After 15 years of decantation the remains of both the Dutch and the Italian left have both fallen into organizational decay. The course of history today shows the inadequacy and degeneration of both poles.

On the key question of our time, the road to the politicization of workers' struggles, both poles of reference from the past have shown their historic failure through an under-estimation of the present resurgence, an inability to understand its dynamic. Neither councilism nor Bordigism can understand how the revolution will come about or the dynamic of the course towards class confrontation.

Programma's refusal to discuss, the sectarianism and sabotage of the International Conferences by Battaglia and the CWO, have done as much as councilism to sterilize revolutionary energies and hinder the clarification so necessary to the regroupment of revolutionaries.

The IR 40 article makes no mention of this historic decantation nor can its new theory of councilism, the greatest danger, explain it.

The ICC now seems to want to polemicize with figments of its imagination. In the IR it's now Battaglia and the CWO who are ‘councilists' because their factory groups and gruppi sindicali are supposedly examples of the KAPD's confusions on the AAUD and not, as in fact they are, examples of the plain old party ‘transmission belts' to the class - an idea shared by many traditional currents of the Third International.

Desparately searching for a greater councilist danger, the IR finally fixes on "individualist petty bourgeois ideology" being the mortal scourge of the councils of tomorrow. At a time when everything points to the obvious fact that the illusions of the ‘60s are way behind us and that only collective struggle has any chance at all to make any dent in the system, how can anyone seriously maintain that "the greatest danger" for the revolution is petty bourgeois individualism?

The future evolution of the political milieu will not be a farcical repetition of May ‘68. Moreover, to think that the weight of the petty bourgeoisie is only channeled into ‘councilism' is nonsense.

The proletarian political milieu of the future will be formed on the lessons of the decantation process of today. Councilism will not be the greatest danger in the future any more than it was in the past.

The origins of the debate

When an organization starts to dabble in the politics of the lesser of two evils, it doesn't necessarily realize that it's going to end up distorting its principles. The process has its own logic.

As the IR article states, a confusion developed in the organization on the "subterranean maturation of consciousness". On the one hand, there was a rejection of the possibility of the development of class consciousness outside of open struggle (and the non-marxist idea that class consciousness is just a reflection of reality and not also an active factor within it). On the other, there was a theorization which held that the proletariat's difficulties in going beyond the union framework required a qualitative leap in consciousness which would happen through a pure "subterranean maturation" during a "long reflux" after the defeat in Poland. Aside from this idea of a long reflux which was quickly proven wrong by the resurgence of class struggle, this debate revealed how difficult it is to understand - in real terms and not just in theory - the path of the politicization of workers' struggles via a resistance to economic crisis today and, more generally, the framework given by the period of state capitalism for the maturation of the subjective conditions of revolution.

The existence of a subterranean maturation of class consciousness, the development of a latent revolutionary consciousness in the working class through its experience in the crisis and through the intervention of communist minorities within it, is a fundamental element of the entire conception of the ICC, the negation of both councilism and Bordigism. It was thus necessary to correct these confusions and clarify in depth. But even though subterranean maturation is explicitly rejected by both Battaglia and the CWO for example (see Revolutionary Perspectives 21) because this is perfectly consistent with the ‘Leninist' theory of the trade union consciousness of the working class (which Lenin defended at various times but not at others) and by the theorizations of degenerated councilism (but not by all of the Dutch left before the Second World War); the ICC decided that the rejection of subterranean maturation was ipso facto the fruit of councilism in our ranks. In the same way, the appearance of a non-marxist vision that reduced consciousness to a mere epiphenomenon, even though it denies both the role of a heterogeneous but inherent revolutionary consciousness in the class as a whole as well as the active role of revolutionary minorities, was interpreted just as unilaterally as a negation of the party. Thus in a resolution that was supposed to sum up the lessons of this debate, there was the following formulation:

"Even if they form part of a single unity and act upon one another, it is wrong to identify class consciousness with the consciousness of the class or in the class, that is to say its extension at a given moment ... It is necessary to distinguish between that which expresses a continuity in the historical movement of the proletariat,, the progressive elaboration of its political positions and of its program, from that which is linked to circumstantial factors, the extension of their assimilation and of their impact in the class."

This formulation is incorrect. It tends to introduce the notion of two consciousnesses. The notion of ‘extension' and ‘depth' applied to consciousness can and is, by other currents, interpreted as a question of qualitative and quantitative ‘dimensions' - especially since the formulation tends to reduce the question of class consciousness to theory and the role of the class to the ‘assimilation' of the program.

When reservations were expressed on this formulation, the new orientation on councilism, the greatest danger and on centrism were introduced into the organization. The present minority has formed a tendency in relation to all of this new theory in that it represents a regression in the theoretical armory of the ICC.

The stakes of the present debate

This article has had to confine itself to answering the points raised in IR 40. But even though these debates have had only a faint echo in our press up to now, it is necessary to see the whole range of the new theory in order to understand the stakes of this debate.

To quote only our public press:

- In WR, the Kautskyist conception of class consciousness is presented as simply a "bugbear"; the danger of substitutionism a mere diversion raised by ‘councilists'. The fact that giving a bourgeois role to the party does not defend the real function and necessity of the party any more than rejecting all parties, seems to be fading out of our press.

- "The ICC, like the KAPD and Bilan, is convinced of the decisive role of the party in the revolution." (IR 40) But the KAPD and Bilan do not defend the same function and role of the party - why start to blur this? It is true that the Italian left regressed after Bilan but it always basically defended Bordiga's conceptions on the party. Bilan began a very important critique of the party as integrated into the state apparatus but it reprinted as its own Bordiga's texts on the relation of party and class with the same lack of understanding of the role of the councils (seen unilaterally through the prism of the anti-Gramsci struggle) and the development of consciousness and the theory of mediation. Furthermore, the conceptions of Internationalisme in the ‘40s are not the same as Bilan's. And there is yet another evolution between Internationalisme's position on class consciousness and the ICC's .

- In Revolution Internationale 125, the Chauvinistic elements Froissard and Cachin are rebaptised ‘centrists' and ‘opportunists' and thus proletarian according to the ICC's new theory while in reality they were counter-revolutionary elements. Calling them ‘centrists' on the model of the tendencies in the workers' movement in ascendancy only served to give an ideological cover to the disastrous policies of the Communist International against the Left in the formation of the CPs in the west. But the grave danger that the use of this concept of centrism represents in the period of decadence for any revolutionary organization including the ICC can be seen two months later in RI; in no.127 the CP is ‘centrist', in other words not so good but still proletarian, until 1934! This is in explicit contradiction to the Manifesto of the foundation of the ICC: "1924-26: the beginning of the theory of ‘building socialism in one country'. This abandonment of internationalism signified the death of the Communist International and the passage of its parties into the camp of the bourgeoisie."

It is now imperative, whatever the confusions on the use of the term ‘centrism' in the past and even among our own comrades to realize that today any conciliation with the positions of the class enemy in the epoch of state capitalism manifest itself by the direct surrender to and acceptance of capitalist ideology and no longer - as in the period of ascendancy - by the existence of ‘intermediary' positions, neither Marxist nor capitalist. And this realization must come before the gangrene of the theory of ‘centrism' destroys our basic principles.

The present debates coming during an acceleration of history are the price the ICC is paying for the superficiality of its theoretical work in the past few years.

Any attempt to apply the notion of ‘councilism, the greatest danger' coherently will lead to destruction of the ICC's position on class consciousness, the touchstone of a correct understanding of class struggle and the role of the future party within it; on the lessons of the revolutionary wave; on state capitalism; on the class line between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

The ICC's ability to fulfill the tasks it was set up to meet in the future historic confrontation will depend, to a large extent, on our ability, all of us, to overcome the present weaknesses and redirect the orientation of the present debates.

JA

Life of the ICC:

- Life in the ICC [2]

Recent and ongoing:

- Internal Debate [3]

- lesser evil [4]

Socialism or barbarism: War under capitalism

- 2475 reads

"Matters have reached such a pitch that today mankind is faced with two alternatives: it may perish in barbarism, or it may find salvation in socialism. As the outcome of the Great War it is impossible for the capitalist classes to find any issue from their difficulties while they maintain class rule...Socialism is inevitable, not merely because proletarians are no longer willing to live under the conditions imposed by the capitalist class, but further because, if the proletariat fails to fulfill its duties as a class, if it fails to realize socialism, we shall crash down together to a common doom." (Rosa Luxemburg, Speech to the Founding Congress of the KPD)

Announced sixty years ago, this warning has acquired and acquires today an acute reality and current relevance. However, the correctness of this point of view, the only one which corresponds to the historical situation in which we live, does not, despite the sad experience of these sixty years separating us from the moment when those lines were written, represent the most widespread opinion - far from it.

From international confrontations to localized conflicts, localized conflicts preparing new international confrontations, the present and the preceding generations have been so marked by this atmosphere, this situation of permanent world war since the beginning of this century, that they have great difficulty in understanding its meaning and significance, and the perspectives that derive from it.

An all-pervasive ideology

An historical phenomenon, world war, through its omnipresent and permanent character, ends up haunting the spirit and becomes in the common view a natural phenomenon, inherent to human nature. It goes without saying that this mythical view in the true sense of the term is largely nourished, supported and spread by the carriers of the dominant ideology, who are past masters of this permanent situation of war and the preparation for world war.

Pacifist ideology is itself the indispensable complement of this myth since it creates feelings of helplessness about every preparation for or situation of war.

At a moment when tensions are more and more sharpening on a worldwide scale, when the means of destruction are being accumulated at such a rapid pace that it is difficult to keep abreast with it, and when the world economic crisis, the source of world war, is plunging into a bottomless abyss, the old sermons are churned out more than ever.

"In face of the spectacular effectiveness of the American military-industrial system, it must seem astonishing that no consensus has been established in the USA around the idea that war, or its preparation, creates prosperity ...

"Whereas periods of peace have always corresponded to periods of desolate (sic!) economic depression, the high points of the economic conjuncture over four centuries now (broadly speaking, as far as Europe is concerned) have always been periods of conflict: the Thirty Years War, the Religious Wars (and their reconstruction), the European Wars of 1720, the Austrian War of Succession and the Seven Years War, with a pinnacle of prosperity in 1775, then - as after every peace-time depression - the wars of the Revolution and of the French Empire, followed by those of the end of the century at the moment of the Second Empire, then the First and Second World Wars." (J.Grapin, Forteresse America, ed Grasset, p 85)

This quotation summarizes the essentials of the dominant and decadent thought of our epoch. Dressed up in the clothing of common sense and objectivity, its goal is to justify war by a pseudo-prosperity; its method is confusion and historical amalgams, its philosophy returns to the crude morality of man being belligerent by nature. It comes as a surprise to nobody therefore that in the chapter from which the passage quoted was taken, one can read:

"It seems that man is organically incapable of replying to the question, ‘if he isn't making war, what is he to do?'"

We totally reject this ahistorical and metaphysical thought which traces a common trait in every war, from the Middle Ages to the last two world wars.

An amalgam between all the wars in the period to the present day is an abstraction and a complete historical falsehood, Both in their course and implications and in their causes, the wars of the Middle Ages are different to the Napoleonic Wars and the wars of the 18th century, just as the two world wars are different to all of these.

In affirming such absurdities, the theoreticians of the contemporary bourgeoisie stand far below the bourgeois theoreticians of the last century, for example General Von Clausewitz who declared: "Semi-barbarian Tartars, the republics of the ancient world, the lords and the merchant cities of the Middle Ages, the kings of the 18th century, the princes and finally the peoples of the 19th century: all waged war in their own manner, went about it differently, using different means and for different goals ..." (General Von Clausewitz, On War)

That the ideologists, advisers, researchers, parliamentarians, military men and politicians express and defend - and they are appointed to do so - this vision of the world in which war is presented as the driving force of history, is not surprising. What, on the contrary, is really terrible, is when we find this same approach among those who want to be a revolutionary force. Stripped of its moral attributes and other misty considerations about human nature, this time it's through an aura of a supposed materialist anti-marxist approach that certain currents of thought arrive at the same conclusions, considering war to be the driving force of history. This is what is behind the idea that war is a favorable objective condition for a world revolution, behind the judgment of militarism as being a solution to overproduction, behind the vision of wars - and we are dealing here with world wars, peculiar to our epoch - as the means of expression and the solution to the contradictions of capitalism.

We don't want to say here that these elements share the preoccupations of the bourgeoisie and its advisers, something which would be gratuitous and unfounded. We don't question their conviction, but rather their analysis, approach and method.

This consists in brushing over the whole history of this century and of its two world wars, minimizing the present paramount importance of the alternative that is so vital for action: revolution or world war, radical transformation of the means and the goals of production, destruction of bourgeois political power, or the equally radical destruction of human society.

In the period between the two wars, revolutionaries saw in the perspective of a second world war, which approached more rapidly with each year, the future of the revolutionary process. Thus they envisaged this future not as a catastrophic perspective but as one opening the door to revolution as in the years 1917-18. The Second World War and its course cruelly destroyed this illusion. The strength of these comrades resided not in a blind obstinacy incapable of putting in question a false vision contradicted by historical reality, but on the contrary in their capacity to draw the lessons of historical reality, thereby permitting revolutionary theory to make a step forward.

The historical evolution of the question of war

Capitalism was born in dirt and blood, and its worldwide expansion was punctuated in the 19th century by a multitude of wars: the Napoleonic Wars which were to shake the feudal structures which were suffocating Europe, the colonial wars on the African and Asiatic continents, wars of independence such as in the Americas, wars of annexation such as in 1870 between France and Germany, and a host of other ones ...

All of these wars represented either a culminating point in the development of capitalism in its march of conquest across the globe, or the overturning of the old agricultural and feudal political structures in Europe. In other words, through these wars, capital unified the world market while dividing the world into irredeemably competing nations.

But all things come to an end, and the dizzying ascent of capitalism in its conquest of the world came to an end too, in the limitations of the world market. By the end of the last century, the world was divided into colonial ownerships and zones of influence between the different developed capitalist nations. From then on, war and militarism started to take on another dynamic: imperialism, the struggle to the death between the different nations for the division of the world, the limited extent of which no longer sufficed to satisfy the expansionist appetites of them all - appetites which have become immense in relation to their previous development. In order to describe this situation, we couldn't do better than Rosa Luxemburg, who drew the following picture:

"As early as the eighties a strong tendency towards colonial expansion became apparent. England secured control of Egypt and created for itself in South Africa a powerful colonial empire. France took possession of Tunis in North Africa and Tonkin in East Asia; Italy gained a foothold in Abyssinia; Russia accomplished its conquests in central Asia and pushed forward into Manchuria; Germany won its first colonies in Africa and in the South Sea, and the United States joined the circle when it procured the Philippines with ‘interests' in Eastern Asia. This period of' feverish conquests has brought on, beginning with the Chinese-Japanese War in 1898, a practically uninterrupted chain of' bloody wars, reaching its height in the great Chinese invasion and closing with the Russo-Japanese War of 1904.

"All these occurrences, coming blow upon blow, created new, extra-European antagonisms on all sides: between Italy and France in Northern Africa, between France and England in Egypt, between England and Russia in central Asia, between Russia and Japan in Eastern Asia, between Japan and England in China, between the United States and Japan in the Pacific Ocean ...

"... it was clear to everybody therefore, that the secret underhand war of each capitalist nation against every other, on the backs of the Asiatic and African peoples must sooner or later lead to a general reckoning, that the wind that was sown in Africa and Asia would return to Europe as a terrific storm, the more certainly since increased armament of the European states was the constant associate of these Asiatic and African occurrences; that the European world war would have to come to an outbreak as soon as the partial and changing conflicts between the imperialist states found a centralized axis, a conflict of sufficient magnitude to group them, for the time being, into large, opposing factions. This situation was created by the appearance of German imperialism." (Rosa Luxemburg, The Junius Pamphlet)

With the First World War, war thus radically changed its nature, its form, its contents and its historic implications.

As its name implies, it becomes worldwide, and it impregnates the entire life of society in a permanent manner. The capitalist world as a whole cannot re-establish a semblance of peace, except in order to wipe out a revolutionary upsurge such as in 1917-18-19, or, under the irresistible pressure of contradictions which it does not control, in order to prepare a new conflict at a higher level.

This was the case between the two world wars. And since the Second World War, the world has not witnessed a single moment of real peace. Already at the end of the last one, the axis of a future world war was posed - namely the confrontation between the Russian and American blocs. Similarly, the dimension which it would take was established by the atomic bombardment of Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

Thus, whereas in the last century militarism remained a peripheral component of industrial production, and whereas warlike confrontations themselves found their theatre of operation on the periphery of the developed industrial centers, in our epoch armaments production is bloated out of all proportion to production as a whole and tends to take over all the energies and vital forces of society The industrial centers become the stakes and theatre of military operations.

It is this process of the military sector supplanting and subordinating the economy for its own purposes which we have witnessed since the beginning of the century, a process which today is undergoing a shattering acceleration.

World war has its roots in the generalized crisis of the capitalist economy. This crisis is its source of nourishment. To this extent, world war, the highest expression of the historical crisis of capitalism, summarizes and concentrates in its own nature all the characteristics of a process of self-destruction.

"In these crises a great part not only of the existing products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity - the epidemic of overproduction .... And why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce ." (Communist Manifesto)

From the moment when this crisis can no longer find a temporary outlet in an expansion of the world market, the world wars of our century express and translate this phenomenon of the self-destruction of a system which by itself cannot overcome its historical contradictions.

Militarism as an investment: war and prosperity - militarism and the economy

The worst of errors concerning the question of war is to consider militarism as a ‘field of accumulation', an investment of some kind which will be profitable in periods of war, and war itself to be a means, if not ‘the means' of the expansion of capitalism.

This conception, when it is not a simple justification for militarism as with the ideologies of the bourgeoisie already quoted, consists of a schematic vision on the part of revolutionaries, coming for the most part from a wrong interpretation of wars in the last century.

The exact position of militarism in relation to the totality of the process of production could give rise to illusions in the phase of worldwide capitalist expansion and the creation of the world market. By contrast, the historical situation opened up with the First World War, in placing war in an entirely different context to that of the preceding century, cleared up any ambiguities about a ‘military investment'. In the last century, when wars remained local and short-lived, militarism did not represent a productive investment in the true sense of the term, but always a wasteful expenditure. In any case, the source of profit did not lie in the exploitation of the workforce in uniform mobilized under the national flag, in the productive forces immobilized in the forces of destruction which weaponry represents, but solely in the enlargement of the colonial empire, of the world market, in the sources of raw materials exploitable on a large scale and at almost zero wage costs, in newly-created political structures permitting a capitalist exploitation of the work force. In the decadent era, apart from companies producing armaments, capital, considered globally, draws no profit whatsoever from armaments production and the maintenance of a standing army. On the contrary, all the costs engendered by militarism are going down the drain. Anything that goes through the industrial production of armaments in order to be transformed into means of destruction cannot be re-introduced in the process of production with the aim of producing new values and commodities. The only thing which armaments can give rise to is destruction and death - that's all.

This argument about ‘military investment', basing itself on the experience of the wars of the last century, is not new We can find exactly the same thing being defended by Social Democracy at the time of the 1914-18 war. Listen again to Rosa Luxemburg:

"According to the official version of the leaders of the Social Democracy, that was so readily adopted without criticism, victory of the German forces would mean, for Germany, unhampered, boundless industrial growth; defeat, however, industrial ruin. On the whole, this conception coincides with that generally accepted during the war of 1870. But the period of capitalist growth that followed the war of 1870 was not caused by the war, but resulted rather from the political union of the various German states, even though this union took the form of the crippled future that Bismarck established as the German Empire. Here the industrial impetus came from this union, inspite of the war and the manifold reactionary hindrances that followed in its wake. What the victorious war itself accomplished was to firmly establish the military monarchy and Prussian Junkerdom in Germany; the defeat of France led to the liquidation of its Empire and the establishment of a republic.

But today the situation is different in all of the nations in question. Today war does not function as a dynamic force to provide for rising young capitalism the indispensable political conditions for its 'national' development." (Rosa Luxemburg, Junius Pamphlet)

Moreover, this quotation is of twofold interest, because of its content, to be sure, but also because it stems from Rosa Luxemburg. As it happens, all the revolutionary militants who defend the idea that militarism can constitute a ‘field of accumulation' for capital draw on the argumentation in a text by the very same Rosa Luxemburg, a text written before the war of 1914-18 (The Accumulation of Capital) and which contains a chapter in which she herself defends the erroneous idea that militarism constitutes a ‘field of accumulation'.

We see here, how the experience of the First World War made her radically revise her position (an example which our comrades should follow!)

War and prosperity

The other facet of this myth of militarism as an investment can be expressed in the following manner: the military domain perhaps burdens public finances at the beginning, provoking enormous deficits, devouring a large part of the social wage, consuming an important and essential part of the productive apparatus which of itself can no longer be used for the production of the means of consumption - but, after the wars, all these ‘investments' are justified by a new phase of prosperity Conclusion: military investment does not become productive immediately, in the short term, but it does so in the long term.

The so-called ‘prosperity' which followed the First World War was relative and limited. In fact, until 1924, Europe was sunk in an economic mire (especially in Germany where this more took on cataclysmic proportions), so that by 1929, its production levels had hardly caught up with those of 1913. The only country where this term had a semblance of reality was the USA (from where the term ‘prosperity' originated), a country whose contribution to the war was the most limited in duration and which suffered no destruction on its own soil.

As far as the period of reconstruction following World War II is concerned, while it spanned the years from 1950 to the end of the ‘60s, this is fundamentally because the productive apparatus of the leading economy of the world, far ahead of all the others, that of the USA, had not been destroyed by the war. With a production representing 40% of total world production, the USA could permit Europe and Japan to reconstruct, despite the terrible destruction of the Second World War. Having arrived late on the world market, benefitting from the immense resources offered by the vast American continent, both with regard to materials and extra-capitalist markets, American capitalism - up until the mid-twenties - followed a somewhat specific dynamic in becoming the principal economy of the world, while old Europe was being plunged into crisis (the USA only participated in the First World War, very minimally). It's only around 1925 that, having exhausted the resources of its own dynamic, US capital began to plunge into crisis, a crisis with the dimensions of the American economy.

It's in this way that the American economy, with the Second World War, turned all its energy ‑ militarily, to be sure - towards the rest of the world, while still being spared the destruction of war on its own soil.

One of the manifestations of this situation was the constitution of the Russian bloc, and at the end of the Second World War this gave rise to the conditions for a new worldwide confrontation, the preparations for which are accelerating today.

In twenty years world capitalism has cleared out every crack and crevice, exploited to the last square foot of the globe every possibility of extending the world market. One of the expressions of this is decolonization which opened these pseudo-autonomous nations to the free play of the competition of the world market - in other words to the struggle for influence between the two great imperialist blocs. This results in the fanning of the flames of local conflicts which, from Africa to Asia, have continued ever since as moments in the confrontation between the two great imperialist blocs.

One can call this ‘prosperity' perhaps; we for our part call it by its name: butchery, barbarism and decadence.

War as a controllable process

We have stated above that the characteristic of the crisis of overproduction, self-destruction, finds its highest expression in world war.

The same goes for the capacity of capitalism to control the military spiral and the mechanisms of war. Just as the bourgeoisie is incapable of mastering the process which plunges the economy into a chronic and increasingly devastating crisis, it is incapable of mastering the increasingly murderous military machine which menaces the very existence of humanity.

Moreover, as with the economic crisis, each measure which the bourgeoisie takes to protect itself rebounds against it. Just as, in face of overproduction, it decides on a policy of general indebtedness, not seeing that this policy of desperation projects the crisis to previously unattained heights - and with no way leading back; in the same way, in face of the military threat posed by its adversary, a particular bourgeois bloc decides to develop more and more powerful weaponry, not seeing that the adversary ends up doing the same, and that this race never stops.

The characteristics of nuclear armaments make this situation very clear. At the end of the Second World War they had become a dissuasive force: the USSR would never have taken the risk of a world war in face of the menace of the atomic umbrella of the US bloc. However, by the end of the ‘50s, the USSR had equipped itself with armaments of a similar nature. For the first time in its history the USA found itself menaced on its own territory.

At this point we were still being reassured: nuclear armaments would remain a ‘deterrent force'. An immense chasm separated classical armaments from nuclear armaments, and the latter were supposed to have the vocation of holding back the two great world powers from any step towards a direct confrontation.

The history of these last 15 years, from the end of reconstruction to the present day, has swept aside this happy dream. In the course of these 15 years we have witnessed, slowly at first but in an accel‑erating manner, a process of the modernization of every kind of armaments, both conventional and nuclear. Nuclear weaponry has been miniaturized and diversified. Long-range missiles with massive firepower (inter-continental missiles) are being supplemented by middle-range types with a selective firepower (the famous SS-20 and Pershing which are springing up like mushrooms in eastern and Western Europe); these weapons are aimed at making possible a geographically limited nuclear confrontation.

Moreover, in addition to the parade of nuclear weapons developed for the purpose of retaliation, there is the development of defense systems, in other words of selective anti-missile systems, systems culminating at the present moment in what is known as 'star wars', with the employment of satellites.

On the other hand, conventional weaponry, in the process of its accumulation and modernization, is itself integrating its own nuclear firepower; a development which finds its clearest contemporary expression in the neutron bomb, a ‘close combat' nuclear weapon, in other words usable in a conventional conflict. A happy prospect and a fine success!

The alibi for the bombardment of Nagasaki and Hiroshima was, as stupid as it may seem today, ‘peace'. The same goes for the first big atomic bombs. In reality, the historical crisis of capitalism and the armaments race which it gives rise to has only succeeded in closing the gap which used to exist between conventional and nuclear weaponry, thereby delivering the material means of escalating the lowest level of conventional conflict to the highest level of massive destruction.

In conclusion we can say not only that the bourgeoisie is incapable of controlling armaments development today, but that in the event of a world-wide conflict it will not be able to control a terrible escalation towards generalized destruction.

From a certain point of view, the slogan ‘socialism or barbarism' is outdated today. The development of the decadence of capitalism means that today things must be posed as follows: socialism or the continuation of barbarism, socialism or the destruction of humanity and of all life-forms on earth.

We have arrived today at a fateful point in the history of humanity, where the existence of fantastic material and scientific capacities provide the means either for self-destruction or for total liberation from the scourge of class society and of scarcity.

We have dealt elsewhere with the argument that war will be a favorable condition for a revolutionary initiative (see our articles in IR 18 - ‘The Historic Course' - and 30 - ‘Why the Alternative is War or Revolution'). Here, therefore, we shall only examine some aspects of this question.

Those who affirm that world war is a favorable, even necessary condition for a revolutionary process, base this extremely dangerous assertion on ‘historical experience': the history of the Paris Commune which arose after the siege of Paris in the war of 1870, and even more so the experience of the Russian Revolution.

Our way of viewing history teaches us exactly the contrary. The experience of the first revolutionary wave, which gave rise to a fantastic uprising in which the working class succeeded in emerging from the butchery and the ruins of four years of war and affirm its revolutionary internationalism, will not repeat itself.

Looked at more closely, the situation at the beginning of this century shows us that this was a particular situation from which we cannot extrapolate the characteristics of our century, unless we do so negatively.

In any case, it mustn't be lost sight of that the first revolutionary wave, launched in Russia, did not spread to the principal countries. Neither in Britain nor in France, and even less so in the USA, did the working class succeed in taking up the revolutionary flame lit in Russia and in Germany.

We are not inventing anything in drawing the balance sheet that war is the worst possible situation in which to launch a revolutionary process At the beginning of this century in Germany for example, revolutionaries drew the same lesson:

"The revolution followed four years of tear, four years during which, schooled by the social democracy and the trade unions, the German proletariat had behaved with intolerable ignominy and had repudiated its socialist obligations ... We Marxists, whose guiding principle is a recognition of historical revolution, could hardly expect that in Germany which had known the spectacle of 4th August, and which during more than four years had reaped the harvest soon on that day, there should suddenly occur on 9th November, 1918 a glorious revolution, inspired with definite class consciousness and directed towards a clearly conceived aim. What happened on 9th November was more the collapse of the existing imperialism than a victory for a new principle." (Rosa Luxemburg, ‘Speech to the Founding Congress of the KPD')

The Second World War, much more devastating and murderous, longer and more colossal, expressing at a higher level its worldwide character, did not in the least give rise to a revolutionary situation anywhere in the world. In particular, what allowed for fraternizations at the front during the First World War - the prolonged trench warfare in which the soldiers of the two camps were in direct contact - could not be repeated during the Second World War with its massive use of tanks and aircraft. Not only did the Second World War not constitute a fertile terrain for the beginning of a revolutionary alternative, its disastrous consequences lasted much longer than the war itself. Thereafter, it took two decades before the struggle, the combativity and the sparks of consciousness of the proletariat reappeared in the world at the end of the ‘60s.

Twice this century, world war has rung out the darkest hour. The second time, the raging storm of barbarism unleashed on humanity was incomparably more powerful and destructive than the first time. Today, if such a catastrophe were to take place again, the very existence of humanity would be under threat. Apart from the ideological plague which, in a war situation, infests the consciousness of millions of workers, erecting an iron barrier against any tentative towards a revolutionary transformation, the objective situation of a world turned to ruins would wipe out this possibility.

In the event of a third world war, not only would any possibility of historically overcoming capitalism be swept away, but moreover we can be almost certain that humanity itself would not survive it. This underlines the crucial importance of the present struggles of the proletariat as the only obstacle to the outbreak of this cataclysm.

M. Prenat

General and theoretical questions:

The Constitution of the IBRP: An Opportunist Bluff, Part 2

- 3474 reads

IR-41, 2nd Quarter 1985

INTRODUCTION

Our intention in the first part of this article (see IR 40 [7]) was to show that the formation of the International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party by the PCInt (Battaglia Comunista) and the Communist Workers’ Organisation is in no way positive for the workers’ movement. This, not because we enjoy playing the part of the “eternal disparager”, but because:

-- the IBRP’s organisational practice has no solid basis, as we have seen during the International Conferences;

-- BC and the CWO are far from clear on the fundamental positions of the communist programme – on the trade union question in particular.

In this second part, we return to the same themes. On the parliamentary question, we shall see that the IBRP has ‘resolved’ the disagreements between BC and the CWO by ‘forgetting’ them. On the national question, we will see how BC/CWO’s confusions have led to a practice of conciliation towards the nationalist leftism of the Iranian UCM [1] [8].

THE QUESTION OF PARLIAMENTARISM

As with the union question, BC’s 1982 platform is neither different nor clearer on the parliamentary question than the Platform of 1952: BC has simply crossed out the more compromising parts. In 1982, as in 1952, BC writes:

“From the Congress of Livorno to today, the Party has never considered abstention from electoral campaigns as one of its principles, nor has it ever accepted, nor will it accept, regular and undifferentiated participation in them. In keeping with its class tradition, the Party will consider the problem of whether to participate on each occasion as it arises. It will take into account the political interests of the revolutionary struggle...” (Platform of the PCInt, 1952 and 1982).

But whereas in 1952, BC spoke of “the Party’s tactics (participation in the electoral campaign only, with written and spoken propaganda; presentation of candidates; intervention in parliament)” (1952 Platform), today, “given the line of development of capitalist domination, the Party recognises that the tendency is towards increasingly rarer opportunities for communists to use parliament as a revolutionary tribune.” (1982 Platform). When it comes down to it, this argument is of the same profundity as that of any bourgeois party which decides not to contest a seat for fear of losing its deposit.

For once, the CWO does not agree with its “fraternal organisation”:

“Parliament is the fig-leaf behind which hides the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. The real organs of power in fact lie outside parliament... to the point where parliament is no longer even the executive council of the ruling class, but merely a sophisticated trap for fools... (...)... The concept of electoral choice is today the greatest swindle ever.” (Platform of the CWO, French version) [2] [9].

If the CWO want to take BC for fools, fine. But they should not do the same with the rest of the revolutionary milieu nor with the working class in general. Here is the IBRP, the self-proclaimed summit of programmatic clarity and militant will, englobing two positions which are not only different, but incompatible, antagonistic even. And yet, we have never seen so much as a hint of a confrontation between these two positions. As we have already pointed out [3] [10], the platform of the IBRP resolves the question, not by ‘minimising’ it, but by... ‘forgetting’ it. Perhaps this is the “responsibility” that we “have a right to expect from a serious leading force”.