International Review 157 - Summer 2016

The summer of 2016 has been marked by signs of growing instability and unpredictability on a world scale, confirming that the capitalist class is finding it increasingly difficult to present itself as the guarantor of order and political control. The botched coup and subsequent wave of repression in Turkey, a strategically vital lynchpin of the global imperialist arena; the “blow back” of the chaos in the Middle East in the form of terrorist outrages in Germany and France; the intense political tremors provoked by the EU referendum result in the UK and the awful prospects taking shape with Trump’s presidential candidacy in the US: all these phenomena, so full of dangers for the ruling class, are no less threatening to the working class, and it is a major challenge to the revolutionary minorities within our class to develop a coherent analysis which cuts through the ideological fog obscuring these events.

It is not possible, in this International Review, to cover all these elements of the world situation. With regard to the coup in Turkey in particular, we want to take the time to discuss its implications and work on a clear analytical framework. For the moment we intend to focus on a series of questions which seem to us to be even more urgent to clarify: the implications of “Brexit” and the Trump candidacy; the national situation in Germany, in particular the problems created by the European refugee crisis; and the social phenomenon common to all these developments: the rise of populism.

We ourselves have been late to recognise the significance of the populist movements. Hence, the text on populism presented in this issue is an individual contribution, written to stimulate reflection and discussion in the ICC (and hopefully beyond). It argues that populism is the product of an impasse which lies at the heart of society; even if the bourgeois state is giving rise to factions and parties which are attempting to ride this tiger, the result of the EU referendum in the UK and Trump’s ascendancy in the Republican Party demonstrate that this is no easy ride and can even deepen the political difficulties of the ruling class.

The purpose of the article on Brexit and the US presidential elections is to apply the ideas of the text on populism to a concrete situation. It is also intended to correct an idea present in previous articles published on our site, that the Brexit referendum [2] result is somehow a "success" for bourgeois democracy, or that the rise of populism [3] today "strengthens democracy".

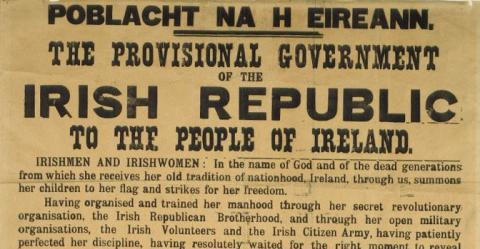

We also publish two historical articles on the national question, focusing on the case of Ireland. They are included not simply because we have reached the centenary of the 1916 Dublin rising, but because this event (and the subsequent history of the Irish Republican Army) was one of the first clear signs that the working class could no longer ally itself with nationalist movements or incorporate “national” demands in its programme; and because today, faced with a new surge of nationalism in the centres of the capitalist system, the necessity for revolutionaries to affirm that the working class has no country is more urgent than ever. As the Report on the German national situation puts it, overcoming the boundaries of the nation is the awesome challenge confronting the proletariat in the face of globalised capitalism and the false alternatives of populism:

“Today, with contemporary globalisation, an objective historical tendency of decadent capitalism achieves its full development: each strike, each act of economic resistance by workers anywhere in the world, finds itself immediately confronted by the whole of world capital, ever ready to withdraw production and investment and produce somewhere else. For the moment, the international proletariat has been quite unable to find an adequate answer, or even to gain a glimpse of what such an answer might look like. We do not know if it will succeed in the end in doing so. But it seems clear that the development in this direction would take much longer than did the transition from trade unionism to mass strike. For one thing, the situation of the proletariat in the old, central countries of capitalism – those, like Germany, at the “top” of the economic hierarchy – would have to become much more dramatic than is today the case. For another, the step required by objective reality – conscious international class struggle, the “international mass strike” – is much more demanding than the one from trade union to mass strike in one country. For it obliges the working class to call into question not only corporatism and sectionalism, but the main, often centuries- or even millennia-old divisions of class society such as nationality, ethnic culture, race, religion, sex etc. This is a much more profound and more political step”.

ICC, August 2016

- 1444 reads

On the question of populism

- 3101 reads

The article that follows is a document under discussion in the ICC, written in June of this year, a few weeks before the “Brexit” referendum in the UK. The corresponding article in this issue of the Review is an attempt to apply the ideas put forward in this text to the concrete situations posed by the referendum result in Britain and by the candidature of Trump in the US.

We are presently witnessing a wave of political populism in the old central countries of capitalism. In states where this phenomenon is more long established, such as France or Switzerland, the right wing populists have become the biggest single political party at the electoral level. More striking however is the encroachment of populism in countries which until now were known for the political stability and efficiency of the ruling class: the USA, Britain, Germany. In these countries, it is only very recently that populism has succeeded in having a direct and serious impact.

The contemporary upsurge of right wing populism

In the United States the political establishment initially strongly underestimated the presidential candidature of Donald Trump in the Republican Party. His bid was at first opposed more or less openly both by the established party hierarchy and by the religious right. They were all taken aback by the popular support he found both in the Bible belt and in the old urban industrial centres, in particular among parts of the “white” working class. The ensuing media campaigns designed to cut him down to size, led among others by the Wall Street Journal and the East Coast media and financial oligarchies, only increased his popularity. The partial ruining of important layers of the middle, but also of the working classes, many of whom lost their savings and even their homes through the financial and property crashes of 2007/08, has provoked outrage against the old political establishment which rapidly intervened to save the banking sector, while leaving to their fate those small savers who had been trying to become owners of their own home.

The promises of Trump to support small savers, to maintain health services, to tax stock exchange and financial big business, and to keep out immigrants feared as potential competitors by parts of the poor, have found an echo both among Christian religious fundamentalists and more left, traditionally Democratic voters who, only a few years before, would not even have dreamt they could vote for such a politician.

Almost half a century of bourgeois political “reformism”, during which candidates of the left, whether at the national or municipal/local level, whether in parties or trade unions, having been elected to allegedly defend workers’ interests, consistently upheld those of capital instead, have prepared the ground for the proverbial “man on the street” in America to consider supporting a multi-millionaire like Trump, with the assumption that he at least cannot be “bought” by the ruling class.

In Britain the main expression of populism at the moment seems to be not a particular candidate or political party (although the UKIP1of Nigel Farage has become a major player on the political stage), but the popularity of the proposal to leave the European Union, and of deciding this by referendum. The fact that this option is opposed by most of the mainstream of the finance world (City of London) and of British Industry has, here also, tended to increase the appeal of “Brexit” among parts of the population. Apart from representing particular interests of parts of the ruling class much more closely tied to the former colonies (the Commonwealth) than to continental Europe, one of the motors of this opposition current seems to be to take the wind out of the sails of new right wing populist movements. Perhaps the likes of Boris Johnson and other Tory “Brexit” advocates would, in the event of an eventual exit, be the ones who would then have to salvage whatever can be saved by trying to negotiate some kind of a close associated status to the European Union, presumably along the lines of that of Switzerland (which usually adopts EU regulations, without however having any say in formulating them).

But it is also possible that politicians of the Conservative Party have themselves become infested by the populist mood, which, in Britain also, gained ground rapidly after the financial and housing crises which negatively affected significant parts of the population.

In Germany, where, after World War II, the bourgeoisie has always succeeded until now in preventing the establishment of parliamentary parties to the right of Christian Democracy, a new populist movement appeared on the scene, both on the streets (Pegida) and at the electoral level (Alternative für Deutschland) in response, not to the “financial” crisis of 2007/08 (which Germany weathered relatively unscathed) but to the ensuing “Euro-Crisis”, understood by part of the population as a direct threat to the stability of the joint European currency, and thus to the savings of millions of people.

But no sooner was this crisis defused, at least for the moment, than there began a massive influx of refugees, provoked in particular by the Syrian civil and imperialist war and by the conflict with ISIS in the north of Iraq. This re-energised a populist movement which was beginning to falter. Although a sizeable majority of the population still support the “welcoming culture” of chancellor Merkel and of many leaders of the German economy, attacks against refugee shelters have multiplied in many parts of the country, while in parts of the former GDR2 a veritable pogrom mood has developed.

The degree to which the rise of populism is linked to the discrediting of the party political establishment is illustrated by the recent presidential elections in Austria, the second round of which was fought between candidates of the Greens and the populist right, whereas the main parties, the Social Democrats and the Christian Democrats, who together have run the country since the end of World War II, both suffered an all time electoral debacle.

In the wake of the Austrian Elections, political observers in Germany have concluded that a continuation of the present Christian and Social Democratic coalition in Berlin after the next general elections would be likely to further favour the rise of populism. In any case, whether through Grand Coalitions between left and right parties (or “cohabitations” like in France), or through the alternation between left and right governments, after almost half a century of chronic economic crisis and around thirty years of capitalist decomposition, large parts of the population no longer believe there is a significant difference between the established left and right parties. On the contrary, these parties are seen as constituting a kind of cartel defending their own interests, and those of the very rich, at the expense of those of the population as a whole, and of those of the state. Because the working class, after 1968, failed to politicise its struggles and to take further significant steps towards developing its own revolutionary perspective, this disillusionment presently above all fans the flames of populism.

In the Western industrial countries, in particular after 9/11 in the USA, Islamist terrorism has become another factor accelerating populism. At present this poses a problem for the bourgeoisie in particular in France, which has once again become a focus of such attacks. The need to counter the continuing rise of the Front National was one of the motives for the anti-terrorist state of emergency and for the war language of François Hollande after the recent attacks, posing as the leader of an alleged international coalition against ISIS. The loss of confidence of the population in the determination and the capacity of the ruling class to protect its citizens at the security (not only the economic) level is one of the causes of the present populist wave.

The roots of contemporary right wing populism are thus diverse and vary from country to country. In the former Stalinist countries of Eastern Europe they seem to be linked to the backwardness and parochialism of political and economic life under the previous regimes, as well as to the traumatising brutality of their transition to a more effective, Western style capitalism after 1989.

In as important a country as Poland the populist right already runs the government, while in Hungary (a centre of the first wave of the proletarian world revolution in 1917-23), the regime of Victor Orban more or less openly promotes and protects pogromist attacks.

More generally, reactions against “globalisation” have been a leading factor of the rise of populism. In Western Europe, the mood “against Brussels” and the EU have long belonged to the staple diet of such movements. But today, such an atmosphere has also appeared in the United States, where Trump is not the only politician threatening to ditch the TTIP3 free trade agreement being negotiated between Europe and North America.

This reaction against “globalisation” should not be confused with the kind of neo-Keynesian correction to the (real) excesses of neo-liberalism propounded by representatives of the left such as ATTAC. Whereas the latter put forward a responsible coherent alternative economic policy for the national capital, the populist critique represents more a kind of political and economic vandalism, such as already partly manifested itself as a moment of the rejection of the Maastricht Treaty in referendums in France, the Netherlands and Ireland.

The possibility of government participation by contemporary populism and the balance of forces between bourgeoisie and proletariat.

The populist parties are bourgeois fractions, part of the totalitarian state capitalist apparatus. What they propagate is bourgeois and petty bourgeois ideology and behaviour: nationalism, racism, xenophobia, authoritarianism, cultural conservatism. As such, they represent a strengthening of the domination of the ruling class and its state over society. They widen the scope of the party apparatus of democracy and add fire-power to its ideological bombardment. They revitalise the electoral mystification and the attractiveness of voting, both through the voters they mobilise themselves and through those who mobilise to vote against them. Although they are partly the product of the growing disillusionment with the traditional parties, they can also help to reinforce the image of the latter, who in contrast to the populists can present themselves as being more humanitarian and democratic. To the extent that their discourse resembles that of the fascists in the 1930s, their upsurge tends to give new life to anti-fascism. This is particularly the case in Germany, where the coming to power of the “fascist” party led to the greatest catastrophe in its national history, with the loss of almost half of its territory and its status as a major military power, the destruction of its cities, and the virtually irreparable damage to its international prestige through the perpetration of crimes which have gone down as the worst in the history of humanity.

Nevertheless, and as we have seen until now, above all in the old heartlands of capitalism, the leading fractions of the bourgeoisie have been doing their best to limit the rise of populism and, in particular, to prevent if possible its participation in government. After years of mostly unsuccessful defensive struggles on their own class terrain, certain sectors of the working class today even seem to feel that you can pressurise and scare the ruling class more by voting for the populist right than by workers’ struggles. The basis for this impression is that the “establishment” really does react with alarm to the electoral success of the populists. Why this reticence of the bourgeoisie in face of “one of its own”?

Until now we have tended to assume that this is above all because of the historic course, (i.e. the still undefeated status of the present generation of the proletariat). Today it is necessary to re-examine this framework critically in face of the development of social reality.

It is true that the establishment of populist governments in Poland and Hungary is relatively insignificant compared to what happens in the old Western capitalist heartlands. More significant however is that this development has not for the moment led to a major conflict between Poland and Hungary and NATO or the EU. On the contrary, Austria, under a social democratic chancellor, after initially imitating the “welcoming culture” of Angela Merkel in summer 2015, soon followed the example of Hungary in erecting fences on its borders. And the Hungarian prime minister has become a favourite discussion partner of the Bavarian CSU who are part of Merkel’s government. We can speak of a process of mutual adaptation between populist governments and major state institutions. Despite their anti-European demagogy, there is no sign for the moment of these populist governments wanting to take Poland or Hungary out of the EU. On the contrary, what they now propagate is the spreading of populism within the European Union. What this means, in terms of concrete interests, is that “Brussels” should interfere less in national affairs, while continuing to transfer the same or even more subventions to Warsaw and Budapest. For its part, the EU is adapting itself to these populist governments, who sometimes are praised for their “constructive contributions” at complicated EU summits. And while insisting on the maintenance of a certain minimum of “democratic standards”, Brussels has refrained for the moment from imposing any of the threatened sanctions on these countries.

As for Western Europe, Austria, it should be recalled, was already a forerunner in once including the party of Jörg Haider as junior partner in a coalition government. Its aim in so doing – that of discrediting the populist party by making it assume responsibility for running the state – partly succeeded. Temporarily. Today however the FPÖ4, at the electoral level, is stronger than ever before, almost winning the recent presidential elections. Of course in Austria the president plays a mainly symbolic role. But this is not the case in France, the second economic power and the second concentration of the proletariat in continental Western Europe. The world bourgeoisie is looking anxiously towards the next presidential election in that country, where electorally the Front National is the leading party.

Many of the political experts of the bourgeoisie have already concluded from the apparent failure of the Republican Party in the USA to prevent the candidature of Trump, that sooner or later the participation of populists in western governments has become more or less inevitable, and that it would be better to start to prepare for such an eventuality. This debate is a first reaction to the recognition that the attempts, to date, to exclude or limit populism have not only reached their own limit but have even begun to have the opposite effect.

Democracy is the ideology best suited to developed capitalist societies and the single most important weapon against the class consciousness of the proletariat. But today the bourgeoisie is confronted with the paradox that, by continuing to keep at arms length parties which do not abide to its democratic rules of “political correctness”, it risks seriously damaging its own democratic image. How to justify the maintenance in opposition indefinitely of parties with a sizable, eventually even with a majority share of votes, without discrediting oneself and getting caught up in inextricable argumentative contradictions? Moreover, democracy is not only an ideology but a highly efficient means of class rule – not least because it is able to recognise and adjust to new political impulses coming from society as a whole.

It is in this framework that the ruling class today poses the perspective of possible populist involvement in government in relation to the contemporary balance of class forces with the proletariat. Present trends indicate that the big bourgeoisie itself does not think that a still undefeated working class necessarily excludes such an option.

To begin with, such an eventuality would not mean the abolition of bourgeois parliamentary democracy, such as was the case in Italy, Germany or Spain in the 1920/30s after the defeat of the proletariat. Even in Eastern Europe today the existing right wing populist governments have not tried to outlaw the other parties or establish a system of concentration camps. Such measures would indeed not be accepted by the present generation of workers, particularly in the western countries, and perhaps not even in Poland or Hungary.

In addition however, and on the other hand, the working class, although not definitively historically defeated, is presently weakened at the level of its class consciousness, its combativeness and its class identity. The underlying historical context here is above all the defeat of the first world revolutionary wave at the end of World War I and the depth and length of the counter-revolution which followed it.

In this context, the first cause of this weakening is the inability of the class, for the moment, to find an adequate answer, in its defensive struggles, to the present stage of state capitalist management, that of “globalisation”. In its defensive struggles, the workers rightly sense that they are immediately confronted with world capitalism as a whole. Because today not only trade and commerce but also, and for the first time, production is globalised, the bourgeoisie can rapidly reply to any local or national scale proletarian resistance by transferring production elsewhere. This apparently overwhelming instrument of the disciplining of labour can only effectively be counteracted by international class struggle, a level of combat which the class in the foreseeable future is still incapable of attaining.

The second cause of this weakening is the inability of the class to continue to politicise its struggles after the initial impetus of 1968/69. What resulted is the absence of the development of any perspective for a better life or a better society: the present phase of decomposition. In particular, the collapse of the Stalinist regimes in eastern Europe appeared to confirm the impossibility of an alternative to capitalism.

During a brief period, maybe from 2003 to 2008, there were tender, relatively inconspicuous first signs of a beginning of the necessarily long and difficult process of proletarian recovery from these blows. In particular, the question of class solidarity, not least between the generations, began to be put forward. The anti-CPE5 movement of 2006 was the high point of this phase, because it succeeded in making the French bourgeoisie back down, and because the example of this movement and its success inspired sectors of youth in other European countries, including Germany and Britain.

However, these first fragile buds of a possible proletarian recovery were soon frozen to death by a third negative wave of events of historic importance in the post 1968 phase, constituting a third major setback for the proletariat: the economic calamity of 2007/08, followed by the present wave of war refugees and other migrants – the biggest since the end of World War II.

The specificity of the 07/08 crisis was that it began as a financial crisis of enormous proportions. As a result, for millions of workers, one of its worst effects, in some cases even the main one, was not direct wage cuts, tax hikes or mass lay-offs imposed by employers or the state, but loss of homes, savings, insurance policies, and so on. These losses, at the financial level, appear as those of citizens of bourgeois society, not specific to the working class. Their causes remain unclear, favouring personalisation and conspiracy theories.

The specificity of the refugee crisis is that it takes place in the context of “Fortress Europe” (and Fortress North America). As opposed to in the 1930s, since 1968 the world capitalist crisis has been accompanied by an international state capitalist management under the leadership of the bourgeoisie of the old capitalist countries. As a result, after almost half a century of chronic crisis, Western Europe and North America still appear as havens of peace, prosperity and stability, at least by comparison with the “world outside”. In such a context, it is not only the fear of the competition of the immigrants which alarms parts of the population, but also the fear that the chaos and lawlessness perceived as coming from the outside, will, along with refugees, gain access to the “civilised” world. At the present level of the extension of class consciousness it is too difficult for most workers to understand that both the chaotic barbarism on the capitalist periphery and its increasing encroachment on the central countries are the result of world capitalism and of the policies of the leading capitalist countries themselves.

This context of the finance, Euro and then the refugee crises have, for the moment, nipped in the bud the first embryonic strivings towards a renewal of class solidarity. This is perhaps at least partly why the Indignados struggle, although it lasted longer and in some ways appeared to develop more in depth than the anti-CPE, failed to stop the attacks in Spain, and could so easily be exploited by the bourgeoisie to create a new left political party: Podemos.

The main result, at the political level, of this new surge of decline in solidarity from 2008 to today has been the strengthening of populism. The latter is not only a symptom of the further weakening of proletarian class consciousness and combativeness, but itself constitutes a further active factor in this. Not only because populism makes inroads into the ranks of the proletariat. In fact, the central sectors of the class still strongly resist this influence, as the German example illustrates. But also because the bourgeoisie profits from this heterogeneity of the class to further divide and confuse the proletariat. Today we seem to be approaching a situation which, at a first glance, has certain similarities with the 1930s. Of course, the proletariat has not been defeated politically and physically in a central country, as took place in Germany at the time. As a result, anti-populism cannot play exactly the same role as that of antifascism in the 1930s. It also seems to be a characteristic of the phase of decomposition that such false alternatives themselves appear less sharply contoured than before. Nevertheless, in a country like Germany, where eight years ago the first steps in politicisation of a small minority of searching youth were being made under the influence of the slogan “down with capitalism, the nation and the state”, today they are being made in the light of the defence of the refugees and the “welcoming culture” in confrontation with the neo-Nazis and the populist right.

In the whole post 1968 period, the weight of anti-fascism was at least attenuated by the fact that the concretisation of the fascist danger lay either in the past, or was represented by more or less marginalised right wing extremists. Today the rise of right wing populism as a potentially mass phenomenon gives the ideology of the defence of democracy a new, much more tangible and important target against which it can mobilise.

We will conclude this part by arguing that the present growth of populism and of its influence on bourgeois politics as a whole is also made possible by the present weakness of the proletariat.

The present debate within the bourgeoisie about the rise of populism

Although the bourgeois debate about how to deal with a resurgent populism is only beginning, we can already mention some of the parameters being put forward. If we look at the debate in Germany – the country where the bourgeoisie is perhaps the most aware and vigilant about such questions – we can identify three aspects being put forward.

Firstly that it is a mistake for the “democrats” to try and fight populism by adopting its language and proposals. According to this argument, it was this copying of the populists which partly explains the fiasco of the governing parties at the recent elections in Austria, and which helps to explain the failure of the traditional parties in France to stop the advance of the FN. The populist voters, they argue, prefer the original to any copy. Instead of making concessions, they argue, it is necessary to emphasise the antagonisms between “constitutional patriotism” and “chauvinist nationalism”, between cosmopolitan openness and xenophobia, between tolerance and authoritarianism, between modernity and conservatism, between humanism and barbarism, According to this line of argumentation, Western democracies today are “mature” enough to cope with modern populism while maintaining a majority for “democracy” if they put their positions forward in an “offensive” manner. This is the position for instance of the present German chancellor Angela Merkel.

Secondly, it is insisted, the electorate should be able to recognise again the difference between right and left, correcting the present impression of a cartel of the established parties. This idea, we suspect, was already the motivation for the preparation, over the past two years, by the CDU-SPD6 coalition, of a possible future Christian Democratic coalition with the Greens after the next general elections. The exit from atomic power after the Fukushima catastrophe announced not in Japan but in Germany, and the recent euphoric support of the Greens for a “welcoming culture” towards refugees associated not with the SPD but with Angela Merkel, were the main steps to date of this strategy. However, the unexpectedly rapid electoral rise of the AfD today threatens the realisation of such a strategy (the present attempt to bring the liberal FDP7 back into parliament might be in response to this, since this party could eventually join a “Black-Green” coalition). In opposition the SPD, the party which in Germany led the “neo-liberal revolution” with its Agenda 2010 under Schröder, could then adopt a more “left” stance. As opposed to the Anglo-Saxon countries, where the conservative right under Thatcher and Reagan imposed the necessary “neo-liberal” measures, in many European continental countries the left (as the more political, responsible and disciplined parties) had to participate or even lead their implementation.

Today however it has become clear that the necessary stage of neo-liberal globalisation was accompanied by excesses which sooner or later will have to be corrected. This was particularly the case after 1989, when the collapse of the Stalinist regimes appeared overwhelmingly to confirm all the ordo-liberal8 theses about the unsuitability of a state capitalist bureaucracy to run the economy. Such excesses are now increasingly been pointed to by thoughtful bourgeois commentators. For instance, it is not absolutely indispensable for the survival of capitalism that a tiny fraction of society owns almost all the wealth. This can be damaging, not only socially and politically but even economically, since the very rich, instead of spending the lion’s share of their wealth, are above all concerned about preserving its value, thus augmenting speculation and withholding solvent purchasing power. Equally, it is not absolutely necessary for capitalism that the competition between nation states takes, to the present extent, the form of the cutting taxes and state budgets so that the state can no longer undertake necessary investments. In other words, the idea is that, through an eventual comeback of a kind of neo-Keynesian correction, the left, whether in its traditional form or through new parties like Syriza in Greece or Podemos in Spain, might regain a certain material basis for posing as an alternative to the ordo-liberal conservative right.

It is important however to note that today’s reflections within the ruling class about a possible future role of the left are not in the first instance inspired by fear (in the immediate) of the working class. On the contrary, many elements of the present situation in the main capitalist centres indicate that the first aspect determining the policy of the ruling class is presently the problem of populism.

The third aspect is that, like the British Tories around Boris Johnson, the CSU9, the “sister” party of Merkel’s CDU, thinks that parts of the traditional party apparatus should themselves apply elements of populist policy. We should note that the CSU is no longer the expression of traditional Bavarian, petty bourgeois backwardness. On the contrary, alongside the adjacent southern province of Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria is today economically the most modern part of Germany, the backbone of its high-tech and export industries, the production base of companies such as Siemens, BMW or Audi.

This third option propagated in Munich of course collides with the first one mentioned above propounded by Angela Merkel, and the present head-on confrontations between the two parties are not just electoral manoeuvres or (real) differences between particular economic interests, but also differences of approach. In view of the chancellor’s present determination not to change her mind, certain representatives of the CSU have even begun to “think aloud” about putting up their own candidates in other parts of Germany in opposition to the CDU at the next general elections.

The idea of the CSU, like that of parts of the British Conservatives, is that if it has become inevitable, to a certain extent, that populist measures are taken, it is better if they are applied by an experienced and responsible party. In this manner, such often irresponsible measures could at least be limited on the one hand, and compensated for by auxiliary measures on the other hand.

Despite the real friction between Merkel and Seehofer, as between Cameron and Johnson, we should not overlook the element of division of labor between them (one part “offensively” defending democratic values, the other recognising the validity of the “democratic expression of enraged citizens”).

At all events, what this discourse, taken as a whole, illustrates, is that the leading fractions of the bourgeoisie are beginning to reconcile themselves to the idea of populist governmental policies of some kind and to some degree, as is already partly being practised by the Brexit Tories or the CSU.

Populism and Decomposition

As we have seen, there has been, and there remains a massive reticence of the main fractions of the bourgeoisie in Western Europe and North America towards populism. What are its causes? After all, these movements in no way put capitalism in question. Nothing they propagate is foreign to the bourgeois world. Unlike Stalinism, populism does not even put in question the present forms of capitalist property. It is an “oppositional” movement of course. But so, in a certain sense, were Social Democracy and Stalinism, without this preventing them from being responsible members of governments of leading capitalist states.

To understand this reticence, it is necessary to recognise here the fundamental difference between present day populism and the left of capital. The left, even when they are not former organisations of the workers’ movement (the Greens for instance), although they can be the best representatives of nationalism and the best mobilisers of the proletariat for war, base their attractiveness on the propagation of former or distorted ideals of the workers’ movement, or at least of the bourgeois revolution. In other words, as chauvinist and even anti-Semitic as they can be, they do not deny in principle the “brotherhood of humanity” and the possibility of improving the state of the world as a whole. In fact, even the most openly reactionary neo-liberal radicals claim to pursue this goal. This is necessarily the case. From the onset, the claim of the bourgeoisie to be the worthy representative of society as a whole was always based on this perspective.

None of this means that the left of capital, as part of the rotten society, does not also put forward racist, anti-Semitic poison of a similar kind to the right wing populists!

As opposed to this, populism embodies the renunciation of such an “ideal”. What it propagates is the survival of some at the expense of others. All of its arrogance revolves around this “realism” it is so proud of. As such, it is the product of the bourgeois world and its world view – but above all of its decomposition.

Secondly, the left of capital proposes a more or less coherent and realistic economic, political and social programme for the national capital. As opposed to this, the problem with political populism is not that it makes no concrete proposals, but that it proposes one thing and its opposite, one policy today and another tomorrow. Instead of being a political alternative, it represents the decomposition of bourgeois politics.

This is why, at least in the sense the term is being used here, it makes little sense to speak of the existence of a left populism as a kind of pendant to that of the right.

Despite similarities and parallels, history never repeats itself. The populism of today is not the same thing as the fascism of the 1920s and 1930s. However, fascism then and populism now have, in some ways, similar causes. In particular, both are the expression of the decomposition of the bourgeois world. With the historic experience of fascism and above all of national socialism behind it, the bourgeoisie of the old central capitalist countries today is acutely aware both of these similarities, and of the potential danger they represent to the stability of capitalist order.

Parallels to the rise of national socialism in Germany

Fascism in Italy and in Germany had in common the triumph of the counter-revolution and the insane fantasy of the dissolution of the classes into a mystical community after the prior defeat (mainly through the weapons of democracy and the left of capital) of the revolutionary wave. In common also is their open contestation of the imperialist carve up and the irrationality of many of their war goals. But despite these similarities (on the basis of which Bilan was able to recognise the defeat of the revolutionary wave and the change in the historic course, opening the way for the bourgeoisie to mobilise the proletariat for world war), it is worthwhile – in order to better understand contemporary populism – to look more closely at some of the specificities of historic developments in Germany at the time, including where they differed from the much less irrational Italian fascism.

Firstly, the shaking of the established authority of the ruling classes, and the loss of confidence of the population in its traditional political, economic, military, ideological and moral leadership was much more profound than anywhere else (except Russia), since Germany was the main loser of the first world war, and emerged from it in a state of economic, financial and even physical exhaustion.

Secondly, in Germany much more than in Italy, a real revolutionary situation had arisen. The way the bourgeoisie was able to nip in the bud, at an early stage, this potential, should not lead us to underestimate the depth of this revolutionary process, and the intensity of the hopes and longings which it awakened and which accompanied it. It took almost six years, until 1923, for the German and the world bourgeoisie to liquidate all the traces of this effervescence. Today it is difficult for us to imagine the degree of disappointment caused by this defeat, and the bitterness it left in its wake. The loss of confidence of the population in its own ruling class was thus soon followed by the much more cruel disillusionment of the working class towards its own (former) organisations (social democracy and trade unions), and disappointment about the young KPD10 and the Communist International.

Thirdly, economic calamities played a much more central role in the rise of National Socialism than was the case with fascism in Italy. The hyper-inflation of 1923 in Germany (and elsewhere in Central Europe) undermined the confidence in the currency as the universal equivalent. The great depression which began in 1929 thus took place only six years after the trauma of hyper-inflation. Not only did the great depression hit a working class in Germany whose class consciousness and militancy were already smashed; the way the masses, intellectually and emotionally, experienced this new episode of the economic crisis was to an important extent modified, pre-formatted so to speak, by the events of 1923.

The crises in particular of decadent capitalism affect every aspect of economic (and social) life. They are crises of (over) production – of capital, commodities, of labour power – and of appropriation and “distribution”, financial and monetary speculation and crashes included. But unlike expressions of the crisis that appear more at the point of production, such as redundancies and wage cuts, the negative effects on the population at the financial and monetary levels are much more abstract and obscure. Yet their effects can be equally devastating for parts of the population, just as their repercussions can be even more world-wide, and spread even faster than ones taking place closer to the point of production. In other words, whereas the latter expressions of the crisis tend to favour the development of class consciousness, those coming more from the financial and monetary spheres tend to do the opposite. Without the aid of marxism it is not easy to grasp the real links between for instance a financial crash in Manhattan and the resulting default of an insurance company or even a state on another continent. Such dramatic systems of interdependence blindly created between countries, populations, social classes, which function behind the backs of the protagonists, easily lead to personalisation and social paranoia. That the recent sharpening of the crisis of capitalism was also a financial and banking crisis, linked to speculative bubbles and their bursting, is not just bourgeois propaganda. That a speculative false manoeuvre in Tokyo or New York can trigger off the collapse of a bank in Iceland, or rock the property market in Ireland, is not fiction but reality. Only capitalism creates such life or death inter-dependence between people who are completely indifferent to each other, between protagonists who are not even aware of each others’ existence. It is extremely difficult for human beings to cope with such levels of abstraction, whether intellectually or emotionally. One way to cope is personalisation, ignoring the real mechanisms of capitalism: it is all the fault of evil forces who deliberately set out to harm us. It is all the more important to understand this distinction between these different kinds of attacks today when, no longer mainly the petty bourgeoisie and the so-called middle classes lost their savings, as in 1923, but millions of workers who own or try to own their own homes, have savings, insurance policies etc.

In 1932 the German bourgeoisie, which already planned to go to war mainly against Russia, found itself confronted by a National Socialism which had become a real mass movement. To a certain extent the bourgeoisie was trapped, the prisoner of a situation it was largely responsible for having created. It could have opted for going to war under a Social-Democratic government, with the support of its trade unions, in a possible coalition with France and even Britain, initially even as a junior partner. But this would have entailed confronting or at least neutralising the Nazi movement, which had not only become too big to handle, but also mainly regrouped that part of the population which was longing for war. In this situation, the German bourgeoisie made the mistake of believing it could make use of the Nazi movement at will.

National Socialism was not simply a regime of mass terror exercised by a small minority against the rest of the population. It had a mass base of its own. It was not only an instrument of capital imposed on the population. It was also its opposite: a blind instrument of atomised, pulverised and paranoiac masses wanting to impose itself on capital.

National Socialism therefore was prepared, to an important extent, by the profound loss of confidence of large parts of the population in the authority of the ruling class and its capacity to run society effectively and afford a minimum of physical and economic security to its citizens. Bourgeois society was shaken to its foundations, first by World War I, then by economic catastrophe: the hyperinflation resulting from the World War (on the losers’ side) and the Great Depression of the 1930s. The epicentre of this crisis was the three empires – the German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian – all of which collapsed under the blows of defeat in war and the revolutionary wave.

Whereas the revolution initially succeeded in Russia, it failed in Germany and in the former Austro-Hungarian empire. In the absence of a proletarian alternative to the crisis of bourgeois society, a deep void opened up, centred around Germany and, let us say, continental Europe north of the Mediterranean basin, but with world-wide ramifications, engendering a paroxysm of violence and pogroms centred around the themes of anti-Semitism and anti-Bolshevism, culminating in the Holocaust and the mass liquidation of whole populations in particular on the territory of the USSR under German occupation.

The form taken by the counter-revolution in the Soviet Union played an important role in the development of this situation. Although there was no longer anything proletarian about Stalinist Russia, the violent expropriation of the peasantry (the collectivisation of agriculture and the liquidation of the “Kulaks”) terrified not only small property owners and savers in the rest of the world, but also many big ones. This was particularly the case in continental Europe, where these property owners (which could include the modest owners of their own dwellings) unprotected (unlike their British and American counterparts) from “Bolshevism” by seas or oceans, had little confidence in the existing unstable European democratic or authoritarian regimes at the beginning of the 1930s to protect them against expropriation by crisis or by “Jewish Bolshevism”.

We can conclude from this historical experience that, if the proletariat is unable to put forward its own revolutionary alternative to capitalism, the loss of confidence in the capacity of the ruling class to “do its job” eventually leads to a revolt, a protest, an explosion of a very different kind, one which is not conscious but blind, directed not towards the future but the past, based not on confidence but fear, not on creativity but on destructiveness and hate.

A second crisis of confidence in the ruling class today

This process we have just described was already the decomposition of capitalism. And it is more than understandable that many marxists and other astute observers of society in the 1930s expected this tendency soon to engulf the whole world. But as it turned out, this was only the first phase of this decomposition, not yet its terminal phase.

Above all, three factors of world historic importance pushed back this tendency to decomposition:

- firstly the victory of the anti-Hitler coalition in World War II, which considerably raised the prestige of Western democracy, in particular of the American model, on the one hand, and “socialism in one country” and the Soviet model on the other;

- and secondly the post World War II “economic miracle” above all in the Western bloc.

These two factors were the doing of the bourgeoisie. The third one was the doing of the working class: the end of the counter-revolution, the return of the class struggle to the centre stage of history, and with it the reappearance (however confused and ephemeral) of a revolutionary perspective. The bourgeoisie, for its part, responded to this changed situation not only with the ideology of reformism, but also with real material (of course temporary) concessions and improvements. All this enforced, among the workers, the illusion that life could improve.

As we know, what led to the present phase of decomposition was essentially the stalemate between the two principal classes, the one unable to unleash generalised war, the other unable to move towards a revolutionary solution. With the failure of the 1968 generation to further politicise its struggles, the events of 1989 thus inaugurated, on a world scale, the present phase of decomposition. But it is very important to understand this phase not as something stagnant, but as a process. 1989 marked above all the failure of the first attempt of the proletariat to re-develop its own revolutionary alternative. After 20 years of chronic crisis, and of worsening of the conditions of the working class and the world population as a whole, the prestige and authority of the ruling class was also eroded, but not to the same extent. At the turn of the millennium there were still important counter-tendencies enhancing the reputation of the leading bourgeois elites. We will mention three here.

Firstly, the collapse of Eastern bloc Stalinism did not at all damage the image of the bourgeoisie of the former Western bloc. On the contrary, what it appeared to disprove was the possibility of an alternative to Western democratic capitalism. Of course, part of the 1989 euphoria was quickly dispelled by reality, such as the illusion of a more peaceful world. But it remained true that 1989 had at least lifted the Damocles sword of the permanent threat of mutual annihilation in a nuclear World War III. Also, after 1989, both World War II and the ensuing Cold War between East and West could credibly be made to appear, in retrospect, as having been the product of “ideology” and “totalitarianism” (thus the fault of fascism and “communism”). At the ideological level it is extremely fortunate for the Western bourgeoisie that the new more or less open imperialist challenger to the USA today is no longer Germany (nowadays itself “democratic”) but “totalitarian China”, and that much of the contemporary regional wars and terrorist attacks can be attributed to “religious fundamentalism”.

Secondly the present “globalisation” stage of state capitalism, already introduced beforehand, made possible, in the post 1989 context, a real development of the productive forces in what until then had been peripheral countries of capitalism. Of course the BRICS11 states, for instance, constitute anything but a model of how workers in the old capitalist countries would want to live. But on the other hand they do create the impression of a dynamic world capitalism. It is worth noting, in view of the importance of the question of immigration for populism today, that these countries are seen at this level as making a contribution to stabilising the situation, since they themselves absorb millions of migrants who might otherwise move towards Europe and North America.

Thirdly, the really breathtaking developments at the technological level, which have revolutionised communication, education, medicine, daily life as a whole, once again create the impression of a vibrant society (vindicating, by the way, our own understanding that the decadence of capitalism does not mean the halt of the productive forces or technological stagnation).

These factors (and there are probably others), although unable to prevent the present phase of decomposition (and with it already a first development of populism), were still able to attenuate some of its effects. As opposed to this, the contemporary bolstering of this same populism today indicates that we may be approaching certain limits of these mitigating effects, perhaps even opening up what we might call a second stage in the phase of decomposition. This second stage, we would argue, is characterised by a growing loss, among increasing parts of the population, of confidence in the willingness or capacity of the ruling class to protect it. A process of disillusionment which, at least for the moment, is not proletarian, but profoundly anti-proletarian. Behind the finance, the Euro and the refugee crises, which are more triggering factors than root causes, this new stage is of course the result of the accumulated effects, over decades, of deeper lying factors. First and foremost the absence of a proletarian revolutionary perspective on the one side. On the other side (that of capital), there is its chronic economic crisis, but also the effects of the ever more abstract character of the mode of functioning of bourgeois society. This process, inherent to capitalism, witnessed a dramatic acceleration in the past three decades with the sharp reduction, in the old capitalist countries, of industrial and manual labour, and of bodily activity in general through mechanisation and the new media such as personal computing and the Internet. Parallel to this, the medium of universal exchange has been largely transformed from metal and paper to electronic cash, which is part of a wider process involving a radical separation from the body and its sensual reality.

Populism and violence

At the basis of the capitalist mode of production is a very specific combination of two factors: economic mechanisms or “laws” (the market) and violence. On the one hand: the precondition for equivalent exchange is the renunciation of violence: exchange instead of robbery. Moreover, wage labour is the first form of exploitation where the obligation to work, and the motivation in the labour process itself, is essentially an economic one rather than imposed by direct physical force. On the other hand, in capitalism the whole system of equivalent exchange is based on an original non-equivalent exchange – the violent separation of the producers from the means of production (“primitive accumulation”) which is the precondition for the wage system, and which is a permanent process in capitalism, since accumulation itself is a more or less violent process (see Luxemburg’s Accumulation of Capital). This permanent presence of both poles of this contradiction (violence and the renunciation of violence), and the ambivalence this creates, permeates the whole of life in bourgeois society. It accompanies every act of exchange, where the alternative option of robbery is ever present. Indeed, a society based at its roots on exchange, and therefore on the renunciation of violence, must enforce this renunciation with the threat of violence, and not only the threat – with the actual use of its laws, justice apparatus, police, prisons etc. This ambiguity is ever present particularly in the exchange between wage labour and capital, where economic coercion is supplemented by physical force. It is specifically present wherever the instrument of violence par excellence in bourgeois society is directly involved – the state. In its relation with its own citizens (coercion and extortion) and with other states (war), the instrument of the ruling class to suppress robbery and chaotic violence is itself, at the same time, the generalised, sanctified robber.

One of the focal points of this contradiction and ambiguity between violence and its renunciation in bourgeois society lies in each of its individual subjects. Living a normal, functional life in the present day world requires the renunciation of a plethora, of a whole world of bodily, emotional, intellectual, moral, artistic, creative needs. As soon as mature capitalism has passed from the stage of formal to that of real domination, this renunciation is no longer in the first instance enforced mainly through external violence. Indeed, each individual is more or less consciously confronted with the choice either of adapting to the abstract functioning of this society or of being a “loser”, possibly landing in the gutter. Discipline becomes self-discipline, but in such a way that each individual becomes the repressor of his own vital needs. Of course, this process of self-disciplining also contains a potential for emancipation, for the individual and above all for the proletariat as a whole (as the self disciplined class par excellence) to become master of its own destiny. But for the moment, in the “normal” functioning of bourgeois society, this self-discipline is essentially the internalisation of capitalist violence. Because this is the case, in addition to the proletarian option of the transformation of this self-discipline into a means of the realisation, the revitalisation of human needs and creativity, there also slumbers another option, that of the blind redirection of internalised violence towards the outside. Bourgeois society always needs and offers an “outsider” in order to maintain the (self) discipline of those who allegedly belong. This is why the blind re-externalisation of violence by the bourgeois subjects “spontaneously” directs itself (i.e. is predisposed or “formatted” to do so) against such outsiders (pogromisation).12

When the open crisis of capitalist society reaches a certain intensity, when the authority of the ruling class is damaged, when bourgeois subjects start to doubt the capacity and determination of the authorities to do their job, and in particular to protect them against a world of dangers, and when an alternative – which can only be that of the proletariat – is missing, parts of the population start to protest and even revolt against their ruling elite, not with the goal of challenging their rule, but in order to oblige them to protect their own “law-abiding” citizens against “outsiders”. These layers of society experience the crisis of capitalism as a conflict between its two underlying principles: between the market and violence. Populism is the option for violence to solve the problems the market cannot solve, and even to solve the problems of the market itself. For instance, if the world labour market threatens to flood the labour market of the old capitalist countries with a wave of have-nots, the solution is to put up fences and police at the frontier and shoot whoever tries to cross it without permission.

Behind populist politics today lurks the thirst for murder. The pogrom is the secret of its existence.

Steinklopfer, 8th June 2016.

1 United Kingdom Independence Party

2 The German Democratic Republic, the old East German Stalinist regime.

3 Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership

4 Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (Austrian Freedom Party)

5 Contrat Premier Emploi: see our Theses on the spring 2006 students' movement in France [4] in International Review n°125

6 Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands, currently the ruling party in Germany in a “grand coalition” with the “Socialist” Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands

7 Freie Demokratische Partei, a “liberal-democratic” party which previously held the balance between SPD and CDU.

8 The German equivalent of neo-liberalism, emphasizing the free market but also the role of the state in protecting the free market

9 Christlich-soziale union

10 Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, the German section of the Third International.

11 Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa

12See the writings of the German researcher into anti-semitism Detlev Claussen.

General and theoretical questions:

- Populism [5]

Rubric:

Brexit, Trump: Setbacks for the ruling class, nothing good for the proletariat

- 2173 reads

The referendum that went out of control

More than thirty years ago in the “Theses on Decomposition”,1 we said that the bourgeoisie would find it more and more difficult to control the centrifugal tendencies of its own political apparatus. What this might mean concretely is demonstrated by the “Brexit” referendum in Britain, and Donald Trump’s candidature for the presidency in the United States. In both cases, unscrupulous political adventurers from the ruling class have exploited the populist revolt of those who have suffered most from the economic upheavals of the last thirty years, for their own self-aggrandisement.

The ICC has been late to recognise the rise of populism and to take account of its consequences. This is why we are publishing now a general text on populism, which is still under discussion in the organisation.2 The article that follows aims to apply the main ideas put forward in the discussion text to the specific situations of Britain and the USA. In a rapidly evolving world situation, it has no pretension to being complete, but we hope that it will give food for thought and further discussion.

The ruling class’ loss of control has never been more strikingly evident than in the spectacle of unprecedented shambolic disorder presented by the EU referendum in Britain and its aftermath. Never before has Britain’s capitalist class so far lost control of the democratic process, never before has it found its vital interests at the mercy of adventurers like Boris Johnson or Nigel Farage.

The failure on all sides to prepare for the consequences of Brexit shows the extent of the disarray within the British ruling class. Within hours of the results being announced, the main Leave campaigners were explaining to their supporters that the £350 million per week extra for the NHS3 which they had promised a Brexit vote would bring – and a figure which had been plastered all over the sides of the Leave campaign buses – was in the nature of a “typing error”. Within days, Farage had resigned as UKIP4 leader, dumping the whole Brexit mess in the laps of his fellow Leavers; Boris Johnson’s former director of communications Guto Harri declared that Johnson’s “heart wasn’t in the Brexit campaign”, and there is more than a strong suspicion that Johnson’s espousal of the Brexit cause was a purely opportunistic, self-serving manoeuvre designed to boost his leadership challenge to David Cameron; Michael Gove, who had been Johnson’s campaign manager all through the referendum and was supposed to run Johnson’s campaign for PM (and who had repeatedly declared his own lack of interest in the job), stabbed Johnson in the back with only two hours to go before the candidature deadline, putting forward his own name for leader on the grounds that his longtime friend Johnson was not fitted to be PM; Andrea Leadsom entered the Tory leadership race as a firm Leave supporter – having declared only three years previously that leaving the EU would be a “disaster” for Britain. Lies, hypocrisy, double-dealing – none of this is new to ruling class politics of course. What is striking is the loss, within the world’s most experienced ruling class, of any sense of the state, of an overriding historic national interest which goes beyond personal ambition or the petty rivalries of cliques. To find a comparable episode in the life of the English ruling class, we would have to return to the Wars of the Roses (as dramatised in Shakespeare’s life of Henry VI), the last gasp of a decaying feudal order.

The unpreparedness of the financial and industrial bosses for a Leave victory is equally striking, especially given all the signs that the result was going to be “the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life” (if one may be permitted to quote the Duke of Wellington after the Battle of Waterloo).5 Sterling’s immediate collapse by 20%, then 30%, against the dollar is an indication that Brexit was not an expected result – it had not been factored in to Sterling’s value before the referendum. We were treated to the unedifying spectacle of banks and businesses rushing for the exit as they looked to move offices, or even incorporation, to Dublin or Paris. George Osborne’s snap decision to reduce corporation tax to 15% was clearly an emergency move to keep companies in Britain, the British economy being one of the world’s most dependent on FDI (Foreign Direct Investment).

The Empire strikes back

All this being said, Britain's ruling class is not out for the count. Cameron’s immediate replacement as PM by Theresa May (not initially expected before September) – a solid and competent politician who had campaigned discreetly for Remain – and the demolition jobs done by the press and Tory MPs on her opponents Andrea Leadsom and Michael Gove, demonstrate a real capacity for rapid, coherent reaction on the part of the ruling class’ dominant state factions.

Fundamentally, this situation is determined by the evolution of world capitalism and the balance of class forces. It is the product of a more general dynamic towards the destabilisation of coherent bourgeois policies in the present stage of decadent capitalism. The driving forces behind the tendency towards populism are not the subject of this article: they are analysed in the “Discussion contribution on the problem of populism” mentioned above. But these general international phenomena take concrete shape under the influence of specific national histories and characteristics. Hence the Tory party has always had its “Eurosceptic” wing which has never really accepted Britain’s membership of the EU and whose origins we can define as follows:

Britain’s – and before it England’s – geographical position off the coast of Europe has meant that Britain has been able to remain detached from European rivalries in a way that continental states cannot; its relatively small size, and its non-existence as a land power, has meant that it could never hope to dominate Europe as France did until the 19th century or Germany since 1870, but could only defend its vital interests by playing the main powers against each other and avoiding commitment to any of them.

Britain’s geographical position as an island, and its status as the world’s first industrial nation, have determined its rise as a maritime world imperialism. Since at least the 17th century, the British ruling classes have had a world outlook, which again let them maintain a certain aloofness from solely European politics.

This situation changed radically after World War II, first because Britain’s status as a dominant world power was no longer sustainable, second because modern military technology (airpower, long-range missiles, nuclear weapons) meant that isolation from European politics was no longer an option. One of the first to recognise this changed situation was Winston Churchill, who in 1946 called for the creation of a “United States of Europe”, but his position was never wholly accepted within the Conservative Party. Opposition to membership of the EU6 grew as Germany increased in strength, especially after the collapse of the USSR and Germany’s reunification in 1990 substantially increased the latter’s weight in Europe. During the referendum campaign, Boris Johnson famously caused a scandal by saying that the EU was an instrument of German domination “à la Hitler”, but he was hardly being original. The same sentiments, in much the same language, had already been expressed in 1990 by Nicholas Ridley, then a minister in Thatcher’s government. It is a sign of the loss of authority and discipline within the post-war political apparatus that whereas Ridley was immediately forced to resign from government, the repercussions for Johnson have been membership of the new cabinet.

Britain’s one-time status, and loss of status, as the world’s greatest imperial power is a deeply-rooted psychological and cultural phenomenon within the British population (including the working class). The national obsession with World War II – the last time Britain could appear to act as an independent world power – illustrates this perfectly. A part of the British bourgeoisie, and still more the petty bourgeoisie, has still not got the message that Britain is today merely a second or third rate power. Many of the Leave campaigners appeared to believe that if only Britain were free of the “shackles” of the EU, the world would rush to buy British goods and services – a fantasy for which the British economy is likely to pay a heavy price.

This sensation of resentment and anger at the outside world for a loss of imperial power is comparable to that felt by a part of the American population as a result of the United States’ perceived loss of status (a constant theme of Trump’s calls to “Make America a great again”) and inability to impose its own rule as it could during the Cold War.

The referendum as a concession to populism

The populist antics of Boris Johnson are more spectacular, and got more media hype, than David Cameron’s old school upper-crust “responsible” persona. But in reality, Cameron is a better indication of how far the rot has gone in the ruling class. Johnson may have been the principal actor, but it was Cameron who set the stage by using the promise of a referendum for party political advantage to win the last general election. By its very nature, a referendum is more difficult to control than a parliamentary election and as such always represents a gamble.7 Like an addict in a casino, Cameron showed himself to be a repeat gambler, first with the referendum on Scottish independence which he won by the skin of his teeth, then with Brexit. His Conservative Party, which has always presented itself as the best defender of the economy, the Union,8 and national defence, has ended up putting all three at risk.

Given the difficulty of manipulating the results, plebiscites about important matters of national interest are for the most part an unwarranted risk for the ruling class. In the classical concept and ideology of parliamentary democracy, even in its decadent sham form, such decisions are supposed to be taken by “elected representatives” advised (and lobbied) by experts and interest groups – not by the population at large. From the point of view of the bourgeoisie, it is a pure aberration to ask millions to decide on complex issues like the EU Constitutional Treaty of 2004, when the mass of voters were unwilling and even unable to read or understand the treaty text. No wonder the ruling class so often got the “wrong” result in the referenda held over this treaty (in France and the Netherlands in 2005, in Ireland in 2008 with the first referendum on the Treaty of Lisbon).9

There are those within the British bourgeoisie today who seem to hope that the May government will pull off the same trick as the French and Irish governments after their botched referenda over the Constitutional Treaty, and somehow just ignore or overturn the referendum. This seems to us unlikely, at least in the short term, not because the British bourgeoisie is more ardently democratic than its fellows but precisely because ignoring the “democratic” expression of the “popular will” merely gives credit to populist ideas and makes them more dangerous.

Theresa May's strategy so far has thus been to make the best of a bad job and to set out down the Brexit path with three of the best-known Leavers in ministerial posts, with responsibility for organising Britain's disentanglement from the EU. Even May’s appointment of the clown Johnson as Foreign Minister – greeted abroad with a mixture of horror, hilarity, and disbelief – is certainly part of this broader strategy. By putting Johnson in the hot seat of the negotiations to leave the EU, May has made sure that the Leavers’ main mouth will have to take much of the flak – and the discredit – for what will almost certainly be unfavourable terms, and is prevented from sniping from the sidelines.

The perception, especially by those who are voting for the populist movements in Europe or the USA, that the whole democratic process is a swindle because the elite simply ignores inconvenient results, is a real threat to the effectiveness of democracy itself as a system of class rule. In the populist conception of politics, “direct decision making by the people” is supposed to circumvent the corruption of elected representatives by the established political elites. This is why in Germany such referendums are excluded by the post-war constitution following the negative experience of the Weimar Republic and their use in Nazi Germany.10

The election that ran off the rails

If Brexit was a referendum that got out of control, Trump’s selection as Republican candidate for the US presidency in 2016 is an election that ran off the rails. When Trump’s candidacy was first declared it was barely taken seriously: the front runner was Jeb Bush, member of the Bush dynasty, preferred choice of the Republican grandees, and as such potentially a powerful fundraiser (always a crucial consideration in US elections). But against all expectations, Trump triumphed in the early primaries and went on to win state after state. Bush fizzled like a damp squib, other candidates were never much more than also-rans, and Republican Party bosses ended confronting the unpalatable prospect that the only candidate with any chance of defeating Trump was Ted Cruz, a man considered by his Senate colleagues as wholly untrustworthy, and only marginally less egotistical and self-serving than Trump himself.

The possibility that Trump might beat Clinton is in itself an indication of how insane the political situation has become. But already, Trump’s candidacy has sent shock waves through the whole system of imperialist alliances. For 70 years, the USA has been the guarantor of the NATO alliance whose effectiveness depends on the inviolability of reciprocal defence: an attack on one is an attack on all. When a potential US President calls into question the NATO alliance, and US readiness to honour its treaty obligations, as Trump has done by declaring that a US response to a Russian attack on the Baltic states would depend on whether in his judgment they had “paid their way”, it certainly sends shivers down the collective spines of the East European ruling classes that confront Putin’s Mafia state directly, not to mention of those Asian countries (Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Philippines) that are relying on America to protect them from the Chinese dragon. Almost equally alarming is the strong possibility that Trump simply does not know what is going on, as suggested by his recent statement that there are no Russian troops in the Ukraine (apparently unaware that Crimea is still considered part of the Ukraine by everybody except the Russians).

Not only that, Trump has gone on to welcome the Russian secret services hacking into the Democratic Party’s IT systems and more or less invited Putin to do his worst. How much, if at all, this will damage Trump is hard to tell, but it is worth recalling that ever since 1945 the Republican Party has been vigorously, if not rabidly anti-Russian, in favour of a powerful military establishment and a massive military presence world-wide no matter what the cost (it was Reagan’s colossal military build-up that really sent the budget deficit through the roof).

This is not the first time the Republican Party has fielded a candidate regarded as dangerously extreme by its leadership. In 1964 it was Barry Goldwater who won the primaries, thanks to support from the religious right and the “conservative coalition” – the forerunners of today’s Tea Party. His programme was at least coherent: drastic reduction of the Federal government especially social security, military strength and readiness to use nuclear weapons against the USSR. This was a classic far-right programme, but one that fitted not at all with the needs of US state capitalism and Goldwater went on to be heavily defeated in the election, partly as a result of the failure of the Republican hierarchy to back him.

Is Trump just a Goldwater 2.0? Not at all, and the differences are instructive. Goldwater’s candidacy represented a seizure of the Republican Party by the “Tea Party” of the time, which was sidelined for years following Goldwater’s crushing electoral defeat. It is no secret that the last couple of decades have seen a comeback for this tendency which has made a more or less successful takeover bid for the GOP.11 However, the Goldwater supporters were, in the truest sense, a “conservative coalition”: they represented a real conservative tendency within an America undergoing profound social changes (feminism, the Civil Rights movement, the beginning of opposition to the Vietnam War, and the breakdown of traditional values). Although many of the Tea Party’s “causes” may be the same as Goldwater’s, the context is not: the social changes he opposed have taken place, such that the Tea Party is not so much a coalition of conservatives as an alliance of hysterical reaction.

This has created increasing difficulties for the big bourgeoisie, which cares little or nothing about these social and “cultural” issues and is basically interested in US military strength and the free trade from which it profits. It has become a truism that anyone running in a Republican primary must prove himself “irreproachable” on a whole series of issues: abortion (you must be “pro-life”), gun control (against it), fiscal conservatism and lower taxation, “Obamacare” (socialism, it should be abolished: indeed Ted Cruz based a part of his credentials on a publicity-seeking filibuster against Obamacare in the Senate), marriage (sacred), Democratic Party (if Satan had a party this would be it). Now, in the space of a few short months, Trump has in effect eviscerated the Republican Party. Here we have a candidate who has shown himself “unreliable” on abortion, on gun control, on marriage (three times in his case), and who has in the past donated money to the Devil herself, Hillary Clinton. In addition, he proposes to raise the minimum wage, maintain Obamacare at least in part, return to an isolationist foreign policy, let the budget deficit go through the roof, and expel 11 million illegal immigrants whose cheap labour is vital to US business.