2015 - International Review

- 1894 reads

International Review - Winter 2015

The articles published in this issue of the International Review first appeared on the web site in 2014 and can be found under that year.

The article on the 2nd International can be found in the World War I special issue

- 1768 reads

100 years after World War I, the struggle for proletarian principles is as relevant as ever

- 1678 reads

One hundred years ago, the war enters a new year of slaughter. It was supposed to have been "over by Christmas", but Christmas has been and gone and the war continues.

On Christmas Eve, fraternisations along the front line give rise to the "Christmas Truce". On their own initiative, and to the consternation of their officers, the soldiers – workers and peasants in uniform – spontaneously leave their trenches to exchange beer, cigarettes, and food. The General Staffs on both sides, taken by surprise, do not know how to react.

These fraternisations pose the question: what would have happened if there had been a workers’ Party, and International, capable of giving them a broader vision, allowing them to bear fruit and become a conscious opposition not only to the war but to its causes? But the workers have been abandoned by their parties: worse still, these parties have become the recruiting officers of the riling class. Behind the firing squads that await deserters and mutineers, stand the "socialist" ministers. The betrayal of the socialist parties in most of the belligerent nations has meant that the International has collapsed, incapable of applying the resolutions adopted by the Congresses of Stuttgart in 1907 and Basel in 1912: this collapse is the theme of one of the articles in this issue.

The New Year begins, but there will be no "Christmas Truce" in 1915: uneasy, the General Staffs will tighten discipline and shell the front lines next Christmas, to nip in the bud any attempt by soldiers and workers to bring the war to an end.

And yet, painfully and without any overall plan, the workers’ resistance re-emerges. In 1915 there will be more fraternisations on the fronts, major strikes in Scotland’s Clyde Valley, demonstrations of German working women against rationing. Little groups, like Die Internationale (of which Rosa Luxemburg is a member) or the Lichtstrahlen group in Germany, survivors of the wreckage of the International, begin to organise despite censorship and repression. In September, some of them will take part in the first international conference of socialists against the war, in the Swiss village of Zimmerwald. This conference, and the two that follow it, will confront the same problems as the 2nd International: is it possible to pursue a policy of "peace" without a policy of revolution? Is it possible to imagine rebuilding the International on the basis of the pre-1914 unity which has been revealed as an illusion?

This time, the left will win the battle, and the 3rd International which will come out of Zimmerwald will be explicitly communist, revolutionary, and centralised: it will be the answer to the failure of the International, just as the Soviets in 1917 will be the answer to the bankruptcy of unionism.

Almost 30 years ago (in 1986), we commemorated the 70th anniversary of Zimmerwald in an article published in this Review. Six years after the failure of the International Conferences of the Communist Left1, we wrote: "Like at Zimmerwald, the regroupment of revolutionary minorities is posed acutely today (…) Faced with the present stakes, the historic responsibility of revolutionary groups is posed. Their responsibility is to engage in the formation of the world party of tomorrow, whose absence can be cruelly felt today (…) The failure of the first attempt at conferences (1977-80) does not invalidate the necessity of such places of confrontation. This failure is a relative one: it is the product of political immaturity, of sectarianism and of the irresponsibility of a part of the revolutionary milieu which is still suffering the weight of the long period of counter-revolution (…) Tomorrow, new conferences of groups descending from the Left will be held".2

We cannot but accept that our hopes, our confidence of those years have been bitterly disappointed. Of the groups that took part in the Conferences, only the ICC and the ICT (ex-IBRP, created by Battaglia Comunista of Italy and the CWO of Britain shortly after the Conferences) remain.3 While the working class has not let itself be enrolled under the colours of generalised imperialist war, neither has it been able to impose its own perspective on bourgeois society. As a result, the class struggle has proven unable to impose on the revolutionaries of the Communist Left even a minimal sense of responsibility: there have been no more Conferences, and our repeated calls for a minimum of common action by internationalists (in particular at the time of the Gulf Wars during the 1990s) have fallen on deaf ears. The spectacle presented by anarchism is, if possible, even more deplorable. Few have emerged with honour (the KRAS in Russia is an admirable exception) from the lapse into nationalism and anti-fascism as a result of the wars in Ukraine and Syria.

Nor has the ICC been spared, in this situation characteristic of the general atmosphere of social decomposition. Our organisation is shaken by a profound crisis, which demands of us an equally profound calling into question and theoretical reflection if we are to face up to it. This is the theme of the article on our Extraordinary Conference, also published in this issue.

Crises are never comfortable, but without crises there is no life and they can be both healthy and necessary. As our article emphasises, if there is one lesson to be learned from the betrayal of the Socialist parties and the collapse of the International, it is that the unruffled path of opportunism leads to death and betrayal, and that the political struggle of the revolutionary left has never avoided confrontation and crisis.

ICC, December 2014

1 We refer our readers to the article ‘Sectarianism, an inheritance from the counter-revolution that must be transcended’ https://en.internationalism.org/ir/22/sectarianism [2]

2International Review n°44, 1st quarter 1986

3The GCI having gone over to the enemy camp when it gave its support to the Peruvian Shining Path movement.

Rubric:

International Review 155 - Summer 2015

In this summer of 2015, the centenary of the Great War – as it is still called – is behind us. The wreaths on the monuments to the fallen faded long ago, the town halls’ temporary exhibitions have been folded and put away, the politicians have given their fine hypocritical speeches, and life can return to whatever passes for “normal”.

In 1915, the war is anything but finished. Nobody any longer has the slightest illusion that the troops will be “home by Christmas”. Ever since the German army’s advance was halted on the river Marne in September 1914, the conflict has been bogged down in trench warfare. During the second battle of Ypres, in April 1915, the Germans used poison gas for the first time, and this will soon be put to use by the armies on both sides of the front. Already, the dead are numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

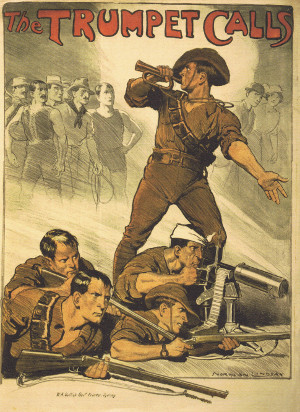

The war will be long, the suffering terrible, and the cost ruinous. How can the populations be made to accept the horror to which they are subjected? This is to be the cynical task of the warring states’ propaganda bureaux, and it is the subject of our first article. Here, as in so many other domains, 1914 marks the opening of a watershed period which will see the step-by-step installation of an omnipresent state capitalism, the only response possible to capitalism’s decadence as a social form.

In 1915, we also begin to see the first signs of working class resistance, especially in Germany where the Socialist Party’s parliamentary fraction no longer votes unanimously for war credits as it had done the previous August. The revolutionaries Otto Rhle and Karl Liebknecht, who were the first to break ranks and oppose the war, have been joined by others. The movement of opposition to the war, bringing together a handful of militants from the various belligerent nations, will give rise in September 1915 to the first Zimmerwald Conference.

The groups who came together in the Swiss village of Zimmerwald were far from presenting a united front. Alongside Lenin’s revolutionary Bolsheviks, for whom the only answer to imperialist war was the civil war for the overthrow of capitalism, there was a – much more numerous – current which still hoped to reach an accommodation with the Socialist Parties that had gone over to the enemy. This was known as the “centrist” current, and it was to play an important part in the difficulties and ultimate defeat of the German revolution in 1919. This is the theme of an internal text written by Marc Chirik in December 1984, substantial extracts of which we are publishing here. The centrist USPD is no more, but it would be a mistake to think that centrism as a form of political behaviour has disappeared as a result; on the contrary, as this text shows, centrism is especially characteristic of decadent capitalism.

To conclude, we also publish in this issue a new article in our series on the class struggle in Africa, notably in this case, in South Africa. We deal here with the dark period between World War II and the world wide renewal of class struggle at the end of the 1960s; despite the divisions imposed by the sinister apartheid regime, we show that the class struggle did indeed survive and that it is far from being a mere accessory to the nationalist movement led by Nelson Mandela’s ANC.

ICC, July 2015

- 1257 reads

The birth of totalitarian democracy

- 5164 reads

Propaganda during World War I

"The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country" (Edward Bernays, Propaganda, 1928).

Propaganda was not invented in World War I. When we admire the lines of tributaries carved on the monumental staircase of Persepolis, laying the produce of the empire before the great King Darius, or the deeds of the Pharaohs immortalised in the stone of Luxor, or the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, we are looking at works of propaganda, designed to communicate a monarch’s power and legitimacy to his subjects. The imperial theatre of troops on parade in Persepolis would have been perfectly recognisable to the British Empire of the 19th century, which itself staged immense and colourful displays of military power at the “Durbars” held in Delhi on great royal occasions.

But while propaganda was not new in 1914, the war profoundly altered its form and its significance. In the years after the war, “propaganda” became a dirty word synonymous with the dishonest manipulation, or fabrication, of information by the state.1 By the end of World War II, following the experience of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia, it took on still more sinister overtones: omnipresent, excluding all other sources of information, invading every corner of private life, propaganda came to be presented as an equivalent to brainwashing. But in reality, Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia were merely crude caricatures of the ubiquitous propaganda machine set up in the Western democracies post-1918, building with ever-growing sophistication on the techniques first developed on a large scale during the war. When Edward Bernays,2 whose seminal work on propaganda we have quoted at the beginning of this article, left the US Committee on Public Information (in reality, the government office of war propaganda) at the end of the war, he established himself as a consultant to private industry not in propaganda but in “public relations” - a term which he himself coined. This was a deliberate and conscious decision: even at such an early date, Bernays knew that the word “propaganda” had become indelibly stained in the public mind with the taint of “untruth”.

World War I marked the moment that the capitalist state first undertook the massive and totalitarian control of information, through propaganda and censorship, directed towards a single over-riding aim: victory in all-out war. As in all other aspects of social life – the organisation of production and finance, the social control of the population and especially of the working class, the transformation of a parliamentary democracy of opposing bourgeois interests into an empty shell – World War I marked the beginning of the state’s absorption and control of social thought and action: state capitalism. After 1918 the men who, like Bernays, had worked for government propaganda departments during the war, fanned out into private industry to become PR men, advertising consultants, experts in “communication” as it is called today. This did not mean an end to state involvement; quite the contrary, it continued a process begun during the war of constant osmosis between the state and private industry. Propaganda did not go away, but it did disappear: it became such a ubiquitous and normal part of everyday life that it became invisible, one of the most insidious and powerful elements of today’s “totalitarian democracy”. When George Orwell wrote his great and chilling novel 1984 (in 1948, hence the title), he imagined a future where every citizen would be obliged to have a screen installed in his home through which he could be subjected to state propaganda: sixty years on, people buy their own TV sets, and willingly sit down to be entertained by products whose sophistication leaves Big Brother’s Ministry of Truth in the shade.3

The approach of war confronted Europe’s ruling classes with a historically unprecedented problem, though the full implications only emerged as war progressed. First, this was a total war involving vast masses of troops: never before in the modern world had such a proportion of the male population been under arms. Second – and in part as a result – the war involved the entire civilian population in the manufacture of military supplies both directly offensive (canon, rifles, ammunition...) and equipment (uniforms, food, transport). Men were conscripted en masse to the front; women were drawn en masse into the factories and hospitals. The war also had to be financed; it was impossible to take on such enormous costs through taxation, and a major preoccupation of state propaganda was to call on the nation’s savings through the sale of war bonds. Because the whole population was directly involved in the war, the whole population had to be convinced that the war was right and necessary, and this was not something that could simply be assumed in advance:

“So great are the psychological resistances to war in modern nations that every war must appear to be a war of defence against a menacing, murderous aggressor. There must be no ambiguity about whom the public is to hate. The war must not be due to a world system of conducting inter national affairs, nor to the stupidity or malevolence of all governing classes, but to the rapacity of the enemy. Guilt and guilelessness must be assessed geographically, and all the guilt must be on the other side of the frontier. If the propagandist is to mobilize the hate of the people, he must see to it that everything is circulated which establishes the sole responsibility of the enemy. Variations from this theme may be permitted under certain contingencies which we shall undertake to specify, but it must continue to be the leading motif.

The governments of Western Europe can never be perfectly certain that a class-conscious proletariat within the borders of their authority will rally to the clarion of war”.4

Propaganda, communist and capitalist

Etymologically the word propaganda means that which is to be propagated, distributed, from the Latin propagare: to distribute. It was used notably in the name of an organism of the Catholic Church created in 1622: the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Ministry for Propagating the Faith). By the end of the 18th century, with the bourgeois revolutions the term also began to be used for propaganda in secular activities, especially for the spreading of political ideas. In What is to be done?, Lenin followed Plekhanov, saying that: “A propagandist presents many ideas to one or a few persons; an agitator presents only one or a few ideas, but he presents them to a mass of people.”

In his 1897 text on “The tasks of the Russian Social-Democrats”, Lenin insisted on the importance of “spreading by propaganda the teachings of scientific socialism (…) spreading among the workers a proper understanding of the present social and economic system, its basis and its development, an understanding of the various classes in (…) society, of their interrelations, of the struggle between these classes (…) an understanding of the historical task of international Social-Democracy...”. Over and over again, Lenin insists on the need to educate conscious workers (“Letter to the Northern Union of the RSDLP, 1902), that to do this the propagandists must first educate themselves, must read, study and gain experience (“Letter to a comrade on our organisational tasks”, September 1902), that the socialists consider themselves heirs to the best of previous culture (“What heritage do we reject?”, 1897). Propaganda then, for communists, is education, the development of consciousness and a critical spirit, inseparable from a determined and conscious effort by the workers themselves to acquire this consciousness.

Compare this to Bernays: “The steam engine, the multiple press, and the public school, that trio of the industrial revolution, have taken the power away from kings and given it to the people. The people actually gained power which the king lost. For economic power tends to draw after it political power; and the history of the industrial revolution shows how that power passed from the king and the aristocracy to the bourgeoisie. Universal suffrage reinforced this tendency, and at last even the bourgeoisie stood in fear of the common people. For the masses promised to become king.

Today, however, a reaction has set in. the minority has discovered a powerful help in influencing majorities. It has been found possible so to mould the mind of the masses that they will throw their newly gained strength in the desired direction (…) Universal literacy was supposed to educate the common man to control his environment. Once he could read and write he would have a mind fit to rule. So ran the democratic doctrine. But instead of a mind, universal literacy has given him rubber stamps inked with advertising slogans, with editorials, with published scientific data, with the trivialities of the tabloids and the platitudes of history, but quite innocent of original thought. Each man’s rubber stamps are the duplicates of millions of others, so that when those millions are exposed to the same stimuli, all received identical imprints (…)

As a matter of fact, the practice of propaganda since the war has assumed very different forms from those prevalent twenty years ago. This new technique may fairly be called the new propaganda.

It takes account not merely of the individual, nor even of the mass mind alone, but also and especially of the anatomy of society, with its interlocking group formations and loyalties. It sees the individual not only as a cell in the social organism but as a cell organized into the social unit. Touch a nerve at a sensitive spot and you get an automatic response from certain specific members of the organism.”5

Bernays had been deeply impressed by the theories of Freud, in particular his work Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse (“Group psychology and the analysis of the Ego”); far from seeking to educate and develop the conscious mind, he considered that the work of the propagandist was to manipulate the unconscious. “Trotter and Le Bon”, he wrote, “concluded that the group mind does not think in the strict sense of the word. In place of thoughts it has impulses, habits, and emotions” (op.cit. p73). Consequently, “If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind, is it not possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without them knowing about it?” (p71). In whose name is this manipulation to be undertaken? Bernays uses the expression “invisible government”, and it is clear that he is referring here to the big bourgeoisie or even to its upper reaches: “The invisible government tends to be concentrated in the hands of the few because of the expense of manipulating the social machinery which controls the opinions and habits of the masses. To advertise on a scale which will reach fifty million persons is expensive. To reach and persuade the group leaders who dictate the public’s thoughts and actions is likewise expensive” (op.cit. p63).

Organising for war

Bernays’ book was written in 1928, and drew in large part on his work as a propagandist during the war. But in August 1914 this was still in the future. European governments had long been accustomed to manipulating the press by “planting” stories and even complete articles, but now this had to be organised – like the war itself – on an industrial scale: the aim, as the German General Ludendorff wrote, was “to mould public opinion without appearing to do so”.6

There is a striking difference in the approach adopted by the continental powers, and that taken by Britain and later America. On the continent, propaganda was first and foremost a military affair. The Austrians, surprisingly, were quickest off the mark: on 28th July 1914, while the war was still a localised conflict between Serbia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the KuK KriegsPressequartier (Imperial and Royal war press bureau) was established as a division of the Army High Command. In Germany, control of propaganda was at first divided between the Army General Staff’s War Press Office and the Nachrichtenabteilung (News Department) of the Foreign Ministry, which was limited to organising propaganda in neutral countries; in 1917, the military created the Deutsche Kriegsnachrichtendienst (German War News Service), which kept control of propaganda to the end.7 In France, a Section d’Information publishing military bulletins and later whole articles, was set up in October 1914 as a division of Military Intelligence. Under General Nivelle, this became a “Service d’Information pour les Armées”, and it was this organism that accredited journalists to the front. The Foreign Ministry had its own “Bureau de la Presse et de l’Information”, and it was only in 1916 that the two were brought together in a single “Maison de la Presse”.

Britain, with its 150 years experience of running a vast empire on the basis of a small island population, was both more informal and more secretive. The War Propaganda Bureau set up in 1914 was run not by the military, but by the Liberal politician Charles Masterman. It was never known by this name, but simply as “Wellington House”, a building housing the National Insurance Commission which the Propaganda Bureau used as a front. At least at the outset, Masterman concentrated on coordinating the work of well-known authors like John Buchan and HG Wells,8 and the Bureau’s output was impressive: by 1915 it had published 2.5 million books, as well as circulating a newsletter to 360 American newspapers.9 By the end of the war, Britain's propaganda effort was in the hands of two newspaper magnates: Lord Northcliffe (owner of the Daily Mail and Daily Mirror) was in charge of British propaganda first in the USA then in enemy countries, while Max Aitken, later Lord Beaverbrook, took responsibility for a full-blown Ministry of Information that was to replace the Propaganda Bureau. Lloyd George, Britain’s Prime Minister during the war, responded to protests at the undue influence thus handed to the press barons, that “he had found that only newspapermen could do the job”. This is according to Lasswell who goes on to remark that “Newspapermen win their daily bread by telling their tales in terse, vivid style. They know how to get over to the average man in the street, and to exploit his vocabulary, prejudices, and enthusiasms (…) they are not hampered by what Dr Johnson has termed ‘needless scrupulosity’. They have a feeling for words and moods, and they know that the public is not convinced by logic but seduced by stories”.10

When the United States entered the war in 1917, its propaganda was immediately put on an industrial footing, with all the country’s genius for logistics. According to George Creel, who ran the “Committee on Public Information”, “Thirty odd booklets were printed in several languages, 75 million copies were circulated in America, and many millions of copies were circulated abroad (…) The Four-Minute Men11 commanded the volunteer services of 75,000 speakers, operating in 5,200 communities, and making a total of 775,190 speeches12 (…) it used 1,438 drawings prepared by volunteers for the production of posters, window cards and similar material (…) Moving pictures were commercially successful in America and effective abroad, such as ‘Pershing’s Crusaders’, ‘America’s answer’, and ‘Under 4 Flags’, etc”.13

The mention of volunteers is significant of the developing symbiosis between the overt state apparatus and civil society that is characteristic of democratic state capitalism: thus Germany had its Pan-German League and its Fatherland Party, Britain its Council of Loyal British Subjects and British Empire Union, and America its American Patriotic League and Patriotic Order of Sons of America (which were essentially vigilante groups).

On a grander scale, the film industry14 acted both independently and under government auspices, and in a less formal mixture of the two. In Britain, the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee – not strictly a government agency but rather an informal grouping of MPs – commissioned the recruiting film You! In 1915. On the other hand, the first major feature-length movie of the war – The Battle of the Somme, 1916 – was produced by an industry cartel, the British Topical Committee for War Films, which paid for permits to film at the front and then sold the resulting film to the government. In Germany, the film producer Oskar Messner established a virtual monopoly over war reporting thanks to his control of government permits to film at the front. Towards the end of the war, in 1917, Ludendorff established the Universum-Film-AG (known as Ufa) for the purpose of “patriotic instruction”; it was financed jointly by state and private industry, and after the war was to become Europe’s biggest private film company.15

To conclude on a technical note. Perhaps the greatest single prize in the propaganda war was the support of the United States. The British here had an immense advantage: right at the outset of the war, the Royal Navy cut Germany’s undersea transatlantic cable, and from then on all communication between Europe and the Americas could only pass through London. Germany attempted to respond using the world’s first radio transmitter at Nauen, but this was before radio had become a means of mass communication and its impact was marginal at most.

The purpose of propaganda

What was propaganda for? At the most general level, propaganda aimed at something that had never been done before: to bind together all the material, physical, and psychological energies of the nation and to direct them towards a single aim – the crushing defeat of the enemy.

Relatively little propaganda was aimed directly at the troops in combat. This may seem paradoxical, but it reveals a certain reality at the foundation of all propaganda: although its underlying theme is a lie – the idea that the nation is united, above social classes, and that all have an equal interest in its defence – it loses its effectiveness when it is too much at odds with the lived reality of those it aims to influence.16

Troops at the front in World War I generally derided the grossest propaganda directed at them, and succeeded in producing their own “press” which caricatured the yellow press delivered to them in the trenches: the British had the Wipers Times,17 the French had La Rire aux Éclats, Le Poilu, and Le Crapouillot. German troops did not believe their propaganda either: in July 1915, a Saxon regiment at Ypres sent a message to the British line, asking them to “Send us an English newspaper so that we may hear the verity”.

Propaganda was also aimed at enemy troops, the French and British in particular taking advantage of the prevailing westerly winds to send balloons to drop leaflets over Germany. There is little evidence that this had very much effect.

The main emphasis, then, was on the home front, rather than the fighting troops, and here we can distinguish several main aims whose relative importance varied according to the specific circumstances of each country. Three stand out especially:

-

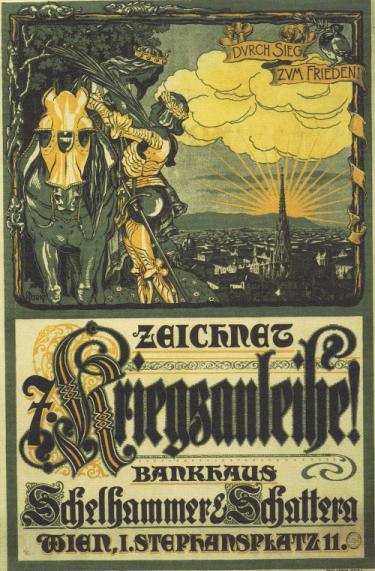

Financing the war. Even at the outset, it was obvious that normal income would not meet the cost of the conflict, which rose dramatically as the war dragged on. The solution was to call on the nation’s accumulated savings through war loans, which remained voluntary even in the autocratic regimes.18

-

Recruitment for the armed forces. For the powers of the European continent, where compulsory military service was a long-standing fact,19 the issue of recruitment did not really arise. In the British Empire and the United States it was another matter: Britain only introduced conscription in 1916, Canada did so in 1917, while in Australia two referendums on conscription were defeated and the country relied entirely on volunteers; in the USA, a Draft Bill was ready as soon as the country entered the war, but the lack of enthusiasm for the war among the working population was such that the government in effect had to “recruit” Americans to support the Draft.

-

Support for industry and agriculture. The nation’s entire productive apparatus must be constantly keyed to the highest pitch and directed wholly to military purposes. Inevitably this means austerity for the population in general, but it also means a vast upheaval in the organisation of industry and agriculture: the men at war must be replaced by women in the fields and factories.

So much for the Home Front, but what of abroad? The 1914-18 war was, for the first time in history, a truly world war and as such the attitudes adopted by neutrals and allies could be of critical importance. The question was posed immediately by Britain's economic blockade of the German coast, imposed on all shipping including that of neutrals: what attitude to this clear violation of international agreements on the freedom of the seas would neutral governments adopt? But by far the most important effort towards neutral states was aimed by both sides at bringing the USA – the only great industrial power not involved in war from the beginning – into the conflict. America’s intervention on behalf of the Entente was by no means a foregone conclusion: it might remain neutral, picking up the pieces once the Europeans had fought themselves to exhaustion; should it enter the war, it might even do so on the German side: Britain was its main commercial and imperial rival, and there was an old historical antipathy to Britain going back to the American revolution and the 1812 war between the two countries.

How propaganda worked

The propaganda objectives that we have just outlined are, in themselves, rational, or at the least accessible to rational analysis. But this begs the question that the vast mass of the population might well have asked: why should we fight? what is this war for? Why, in short, is propaganda necessary? How can millions of men be persuaded to hurl themselves into the maelstrom of murder that was the Western Front, year after year? How can millions of civilians be made to accept the slaughter of sons, brothers, husbands, the physical exhaustion of factory labour and the privations of rationing?

The reasoning of pre-capitalist societies no longer held true. As Lasswell points out: “The bonds of personal loyalty and affection which bound a man to his chief have long since dissolved. Monarchy and class privilege have gone the way of all flesh and the idolatry of the individual passes for the official religion of democracy. It is an atomised world...”.20 But capitalism is not only the atomisation of the individual, it has also called into being a social class inherently opposed to war and capable of overthrowing the existing order, a revolutionary class unlike any other because its political power is founded on consciousness and understanding. It is a class which capitalism itself has been forced to educate so that it can fulfil its role in the productive process. How then to appeal to a literate working class schooled in political debate?

In these conditions, propaganda “is a concession to the rationality of the modern world. A literate world, a schooled world, prefers to thrive on argument and news (…) All the apparatus of diffused erudition popularizes the symbols and forms of pseudo-rational appeal: the wolf of propaganda does not hesitate to masquerade in the sheepskin. All the voluble men of the day – writers, reporters, editors, preachers, lecturers, teachers, politicians – are drawn into the service of propaganda to amplify a master voice. All is conducted with the decorum and trappery of intelligence, for this is a rational epoch, and demands its raw meat cooked and garnished by adroit and skilful chefs”. These “new chefs” must serve up the “raw meat” of unavowable emotion: “A new flame must burn out the canker of dissent and temper the steel of bellicose enthusiasm”.21

In a sense we can say that the problem facing the ruling class in 1914 is one of different perspectives for the future: up until 1914, the Second International had repeatedly declared, in the most solemn terms, that the war which it rightly saw as imminent would be fought for the interests of the capitalist class, and had called on the international working class to oppose it� w�ith the perspective of revolution, or at the very least mass international class struggle;22 for the ruling class, the real perspective of war, of appalling bloodshed in defence of the interests of a small class of exploiters, must therefore at all costs be concealed. The bourgeois state must assure itself of the monopoly of propaganda by smashing or seducing the organisations which give expression to the working-class perspective, and at the same time hide its own perspective under the illusion that the conquest of the enemy will open up a new period of peace and prosperity – a “new world order”, as George Bush once put it.

This introduces two fundamentals of war propaganda: “war aims”, and the hatred of the enemy. The two are closely connected. “To mobilize the hatred of the people against the enemy, represent the opposing nation as a menacing, murderous aggressor (…) It is through the elaboration of war aims that the obstructive role of the enemy becomes particularly evident. Represent the opposing nation as satanic; it violates all the moral standards (mores) of the group and insults its self-esteem. The maintenance of hatred depends upon supplementing the direct representations of the menacing, obstructive, satanic enemy, by assurances of ultimate victory”.23

Already prior to the war, a good deal of work had been done by psychologists on the existence and nature of what Gustave Le Bon24 called the “group mind”, a form of collective unconscious formed by “the crowd” in the sense of the anonymous mass of atomised individuals, cut off from social ties and obligations, which is characteristic of capitalist society and especially of the petty bourgeoisie. Lasswell comments that “Every school of psychological thought seems to agree (…) that war is a type of influence, which has vast capacities for releasing repressed impulses and for allowing their external manifestations in direct form. There is thus a general consensus that the propagandist is able to count upon very primitive and powerful allies in mobilising his subjects for war-time hatred of the enemy”. He also quotes from John A Hobson’s The psychology of jingoism (1900),25 which speaks of “a coarse patriotism, fed by the wildest rumours and the most violent appeals to hate and the animal lust for blood, [that] passes by quick contagion through the crowded life of the cities, and recommends itself everywhere by the satisfaction it affords to the sensational cravings. It is less the savage feeling for personal participation in the fray than the feeling of a neurotic imagination that marks Jingoism”.26

There is a certain contradiction here nonetheless. Capitalism, as Rosa Luxemburg said, likes to present, and indeed has, a cultured self-image;27 yet beneath the surface lies a seething volcano of hatred and violence which occasionally breaks through into the open – or is put to use by the ruling class. The question remains: is this violence a return to primal aggressive instincts or is it caused by the neurotic, anti-human nature of capitalist society? It is certainly true that human beings have asocial, aggressive instincts as well as social ones. Yet there is a fundamental difference between the social life of archaic societies and capitalism. In the former, aggression is held in check and regulated by a whole web of social interactions and obligations outside of which life is not merely impossible but unimaginable. In capitalism, the tendency is towards the individual’s detachment from all social ties and responsibilities,28 whence an immense emotional impoverishment and a lack of resistance to the anti-social instincts.

An important element of the culture of hatred within capitalist society, is the guilty conscience. This did not appear with capitalism: on the contrary, if we follow Freud it is an ancient attainment of human culture. Human beings’ ability to think and so to choose between two different courses of action places them before the choice between good and evil, and hence before moral conflict. The sense of guilt is a consequence of this very freedom, which is both a product of culture springing from the ability to think, yet at the same time largely unconscious and so open to manipulation. One mechanism that the unconscious uses to deal with guilt is through projection: guilt is projected onto "the other". The guilty conscience’s self-hatred is relieved by being projected towards the outside, onto those who have suffered injustice and who are thus the cause of guilty feelings.

Some might object that capitalism is hardly the first society in which murder, exploitation, and oppression have existed – and this of course is true. The difference with all previous societies is that capitalism claims to be based on the “rights of man”: when Genghis Khan massacred the population of Khorasan, he did not claim to be doing it for their own good. The oppressed, enslaved, and exploited populations of imperialistic capitalism weigh on the conscience of bourgeois society, whatever the self-serving justifications (usually backed up by the church) it may have invented for itself. Prior to World War I, the hatred of bourgeois society had been directed logically against the most downtrodden sections of society: the precursors to the hate-mongering images of Germans are thus to be found in the caricatures of the Irish in Britain, and the negroes in the United States in particular.

Hatred of the enemy is far more effective if it can be combined with a conviction in one’s own righteousness. Hatred and humanitarianism are thus close companions in war-time.

It is striking that the politically more backward, autocratic regimes of Germany and Austria-Hungary were unable to wield these weapons with the success and sophistication of the British and French, and later the Americans. Most caricatural in this respect was Austria-Hungary, a sprawling multi-ethnic empire made up in large part of minorities infected by a fractious nationalism. Its semi-feudal, aristocratic ruling caste, cut off from the aspirations of its population, had none of the versatile unscrupulousness of a Poincaré, a Clemenceau, or a Lloyd George. Its social vision was limited to the Vienna Ring, a multi-cultural city of which Stefan Zweig could write that “Life was pleasant in this atmosphere of spiritual conciliation and, all unbeknown to himself, each bourgeois of this city was raised by his education to that cosmopolitanism which repudiates all narrow nationalism, to the dignity, in short, of a citizen of the world”. Small wonder then, that Austro-Hungarian propaganda combined medieval imagery with art nouveau style: St George overcoming an enemy reduced to the mythical anonymity of a dragon; of the handsome prince in shining armour escorting his lady to the sunlit kingdom of peace (both these posters are for war loans).

For all its brutal Prussian heavy-handedness, the German aristocratic caste still preserved a certain sense of noblesse oblige, at least in its own vision of itself that it sought to portray to the outside world. According to Lasswell, German ineffectiveness could be blamed on the lack of imagination of the Germany military, who kept control of the propaganda throughout, but there was more to it than that: in early 1915 the Leitsätze der Oberzensurstelle (the censorship bureau) laid down the following guidelines for journalists: “The language towards the enemy states can be hard (…) The pureness and the greatness of the movement that seized our people demand a dignified language (…) Calls for barbaric warfare, extermination of foreign people are disgusting; the army knows where severity and clemency should reign. Our shield must remain pure. Similar callings by the enemy yellow press are no excuse for such behaviour on our part”.

The British and French had no such qualms, any more than did the Americans.29

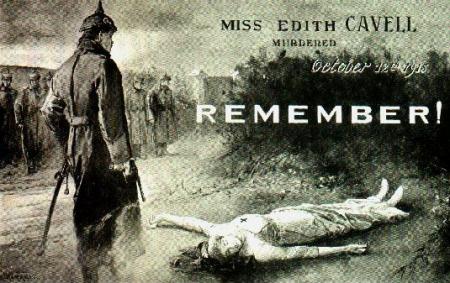

The contrast between the British and German handling of the Edith Cavell affair is striking in this respect. Edith Cavell was a British nurse who worked for the Red Cross in Belgium, continuing to do so under the German occupation. At the same time, she was helping British, French and Belgian troops escape to Britain via Holland (there have also been unconfirmed suggestions that she was working for British intelligence). Cavell was arrested by the Germans, tried and found guilty of treason under German military law, and shot by firing squad in 1915. This was a gift from heaven for the British, who raised an enormous scandal aimed both at recruitment in Britain and at discrediting the German cause in the USA. A torrent of posters, postcards, pamphlets and even postage stamps kept the tragic fate of nurse Cavell constantly before the public mind (in this poster she appears a good deal younger than she was in reality).

Not only were the Germans hopelessly inept at responding, they proved equally incapable of using their own opportunities. “Shortly after the Allies had created the most tremendous uproar about the execution of Nurse Cavell, the French executed two German nurses under substantially the same circumstances”, Lasswell tells us.30 An American newspaperman asked the officer in charge of German propaganda why they did not “raise the devil about those nurses the French shot the other day”, to which the German replied: “What? Protest? The French had a perfect right to shoot them!”.

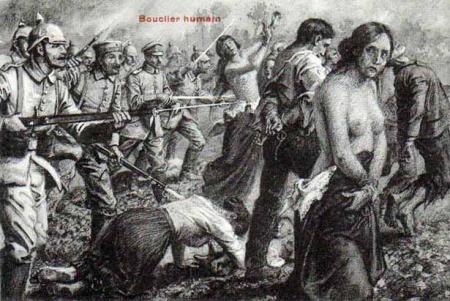

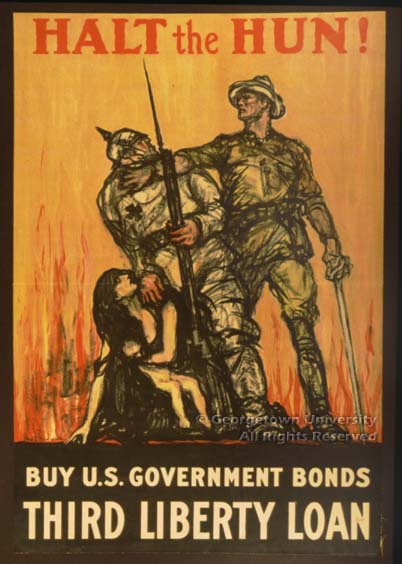

The British made enormous use of Germany’s occupation of Belgium, not without a good dose of cynicism since the German invasion merely forestalled Britain’s own war plans. Much was made of the most lurid atrocity stories: German troops were bayoneting babies, making soap out of corpses, tying priests upside-down on the clappers of their own church bells, etc., etc. To give such fanciful tales more weight, the British commissioned a report on “Alleged German atrocities”, chaired by Viscount James Bryce, who had been a respected ambassador to the USA (1907-13) and was known as a scholar imbued with, and sympathetic to, German culture (he had studied at Heidelberg) – so many guarantees of impartiality. Since atrocities are inevitable when a raw conscript army officered by political incompetents is engaged among a rebellious civilian population,31 some of those condemned by the “Bryce Report” as it became known, were undoubtedly true. However, there is no doubt either that the Committee was unable to interview any witnesses of the supposed atrocities, and that the majority were pure fabrications especially the most revolting tales of rape and mutilation. Nor were the Allies above using a touch of pornographic sensationalism, with posters portraying women in suggestive states of undress, a simultaneous appeal to prudery and salaciousness.

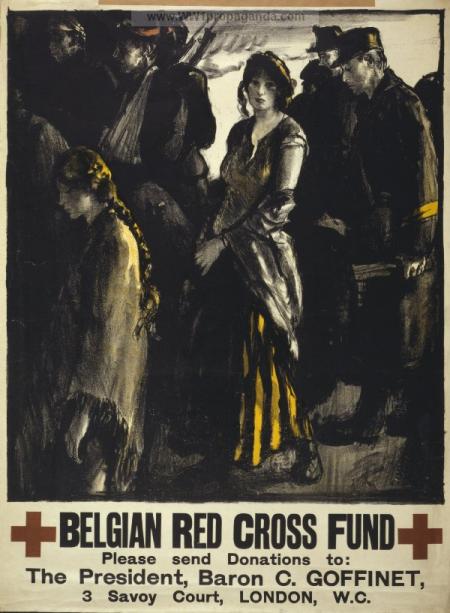

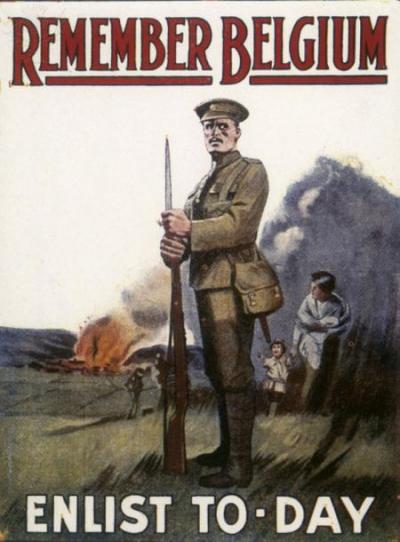

The appeals for help to Belgian widows and orphans issued by organisations like the “Committee for Belgian Relief”, with the aid of an illustrious galaxy of literary stars, including (in Britain) Thomas Hardy, John Galsworthy and George Bernard Shaw amongst the best known,32 or for funds to support the Belgian Red Cross, were the precursors of today’s “humanitarian” military interventions supported by intellectuals like Bernard Henri-Lévy (though one would hesitate to compare, in terms of talent, an Henri-Lévy with a Thomas Hardy). The plight of Belgium, indeed, was used over and over again in a multitude of contexts: in recruitment, to denounce German barbarism or perfidious disregard for diplomatic treaties (much was made of Germany’s reneging on its commitment to honour and defend Belgian neutrality), and, importantly, to win American sympathy for the Franco-British cause.

German attempts to respond to the barrage of Allied hate campaigns, based on atrocity stories and cultural animosity, remained legalistic, literal-minded, and unimaginative. In effect, the Germans remained on the back foot, constantly forced to react to Allied attacks and incapable making effective use of the Allies’ own contraventions of international law – as we can see in the Cavell case.

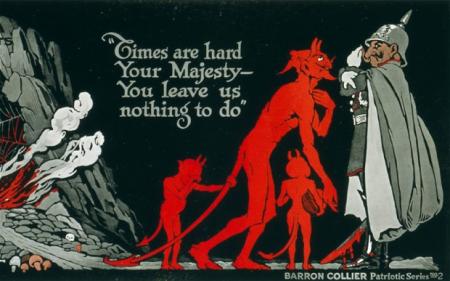

In writing of hate campaigns and atrocities, Lasswell makes the point that “It is always difficult for many simple minds inside a nation to attach personal traits to so dispersed an enemy as a whole nation. They need to have some individual on whom to pin their hate. It is therefore important to single out a handful of enemy leaders and load them down with the whole decalogue of sins”. And he continues, “No personality drew more abuse of this sort in the last war than the Kaiser”.33 The Kaiser was made to epitomise everything barbaric, militaristic, brutal, autocratic – “The Mad Dog of Europe”, as he was christened by the British Daily Express, or even the Beast of the Apocalypse according to the Parisian Liberté. The parallels with the propaganda use of Saddam Hussein or Osama Bin Laden to justify the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are obvious.

Hatred of what is different, of whatever is outside the group, is a powerful unifying psychological force. Warfare – and above all the total war of national masses – demands that the nation’s psychological energies be welded into a single effort. The entire nation must be aware of itself as a unity, which means eradicating from conscious awareness the indubitable fact that this unity is unreal, a myth, since in reality the nation is made up of opposing classes with antagonistic interests. One way of achieving this is to emphasise a figurehead of national unity, which may be real, symbolic, or both. The autocratic regimes had the ruler: the Tsar in Russia, the Kaiser in Germany, the Emperor in Austria-Hungary. Britain had the King and the symbolic figure of Britannia, France and the United States had the Republic, personified respectively as Marianne and Liberty. The drawback of such positive symbolism is that it can also fall victim to criticism especially should the war go badly. The Kaiser, after all, was also a figure of Prussian militarism and junkerdom which was far from arousing universal enthusiasm in Germany; the King in Britain could also be associated with an arrogant and privileged aristocratic ruling caste. Hatred directed outside the nation, at the enemy, has no such disadvantages. The hated figure’s defeats may make him contemptible but never less hateful, while his successes only make him more so. “The leader or leading idea might also, so to speak, be negative; hatred against a particular person or institution might operate in just the same unifying way, and might call up the same kind of emotional ties as positive attachment”.34 We are tempted, indeed, to say that the more society is fractured and atomised, the sharper the real class contradictions within it, the greater the emotional and spiritual emptiness of its mental life, the greater are its reserves of frustration and hatred and the more effectively can these be redirected into hatred of an external enemy. Or to put it another way, the further a society has moved towards advanced capitalist totalitarianism, be it Stalinist, fascist or democratic, the more will the ruling class use hatred of the outside as a means to unite an atomised and disunited social bodyody.

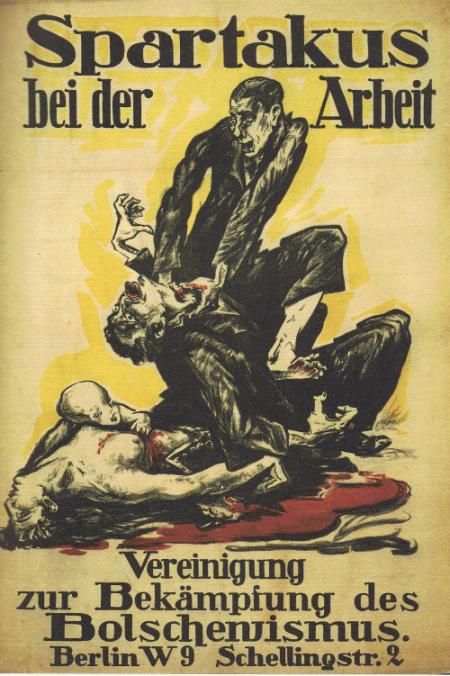

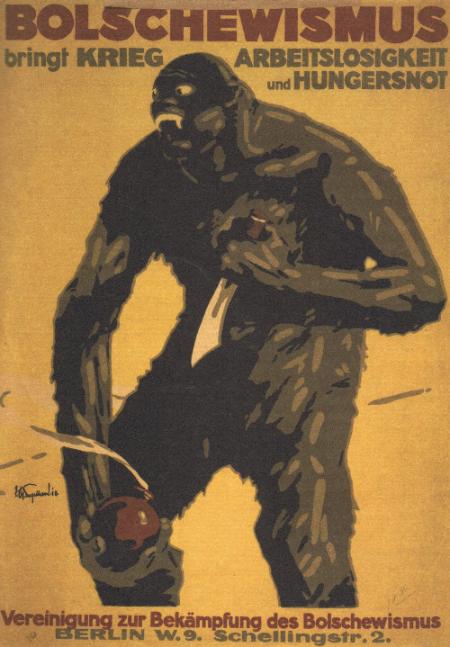

It was only in 1918 that posters appeared in Germany, that could be said to prefigure the Nazis anti-Jewish propaganda. It was directed, not against Germany’s military enemies, but against the internal threat from the working class, and especially from its most combative, class-conscious and dangerous element: Spartacus.

These posters were both produced by a right-wing “Union for struggle against Bolshevism”, allied to the same Freikorps units of disbanded soldiers and lumpen elements that were to assassinate Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, at the behest of the Social-Democratic government. One wonders what workers thought of the idea that it was Bolshevism that was responsible for “War, unemployment, and hunger” as the poster on the right pretends.

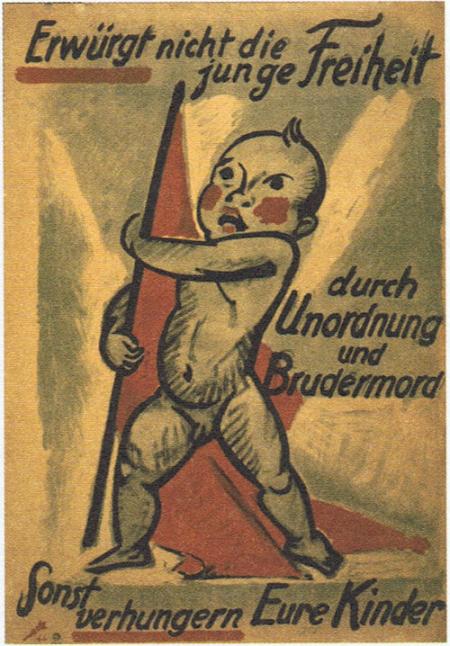

Just as the SPD used the Freikorps while disowning it, the poster above – presumably by the SPD since the baby is clutching a red flag – avoids referring to Bolshevism or Spartakus directly, but still puts out the same message: “Don’t strangle baby Freedom with disorder and crime! Otherwise, our children will die of hunger!”.

The psychology of propaganda

For Bernays, as we have seen above, propaganda was directed at the “impulses, habits, and emotions” of the masses. It seems to us undeniable that the theories of Le Bon, Trotter, and Freud on the over-riding importance of the unconscious mind, and above all what Bernays terms the “group mind”, strongly influenced the production of propaganda, at least in the Allied countries. It is therefore worth considering its themes in this light. Rather than concerning ourselves with the fairly straightforward message - “support the war” - let us look at its vehicle: the emotional wellsprings that propaganda sought to press into service.

We are struck first by the fact that this overwhelmingly patriarchal society, engaged in warfare whose combatants are all men and where war is still seen as a strictly male preserve, choose women as a national symbol: Britannia, Marianne, Liberty, Eternal Rome. These female figures can be extremely ambiguous. Britannia – a mixture of Athena and the indigenous Boadicea – tends to be statuesque and regal, but she can also be motherly, sometimes explicitly so; Marianne, bare-breasted, is generally heroic but she can be downright alluring on occasion, as can Roma; Liberty manages to play in every key – majestic, maternal, and enticing all at once.

Britain and America also have their father symbols: John Bull and Uncle Sam, both of whom are shown pointing sternly out of their posters “wanting YOU! For the armed forces”. One British poster rather optimistically features a marriage of Britannia with Uncle Sam.

The real art of propaganda lies in suggestion rather than clarity, and this ambiguous combination, or rather confusion of imagery, loads the message with all the powerful emotions of childhood and family. Guilt fuelled by sexual desire and sexual shame is a powerful driver, especially for the young men at whom the recruiting campaigns were directed. These were critical in the “Anglo-Saxon” countries where conscription was introduced late (Britain, Canada), with much controversy (USA) or not at all (Australia). In Britain, indeed, the use of sexual shame was made absolutely explicit, in the “White Feather campaign” organised by Admiral Charles Fitzgerald, with the enthusiastic support of the suffragette leaders Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst: this involved recruiting young women to hand a white feather – a traditional symbol of cowardice – to men not in uniform.35

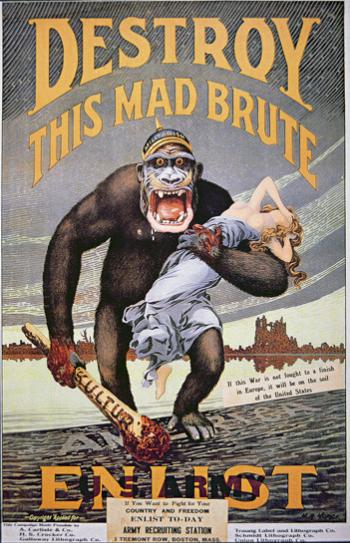

The “King Kong” coiffed with a German helmet (in the poster above), and carrying a semi-naked female, is a typically American effort to manipulate feelings of sexual insecurity. The black ape ravishing the white innocent is a classic theme of the anti-negro propaganda prevalent in the United States well into the 1950s and 60s, which played on the supposed “animality” and sexual prowess of black men portrayed as a threat to “civilised” white womanhood, and of course by implication to her male “protector”.36 This made it possible, in the American south, for the white planter aristocracy to tie the “poor white trash” to support for the existing order of segregation and class rule, whereas their real material interests should have made them natural allies of the black worker.37 The myth of “white superiority”, with all its accompanying emotions of sexual shame, fear, domination and violence, infested American society including the working class – prior to World War I, the only union to form chapters where blacks and whites were on an equal footing, was the revolutionary syndicalist IWW.38

The other side of the coin to sexual shame and fear is the image of “man as protector”. The modern soldier, a worker in uniform whose life in the trenches will be one of mud, lice, and imminent death from shells and bullets fired by an enemy he cannot even see, is portrayed over and over again as the gallant defender of hearth and home against a bestial (if often unseen) foe.

Propaganda thereby carried out a veritable hijack on one of the proletariat’s prime principles: solidarity. From its beginnings, the working class had had to fight for the protection of women and children, especially to shield them from the unhealthiest or most dangerous employment, to limit their working hours, or to outlaw their subjection to night work. By protecting the reproduction that only women can assume, the workers’ movement took on the solidarity both between the sexes and towards future generations, just as the creation of the first retirement pension funds outside state control expressed its solidarity towards the older generations no longer apt for work.

At the same time, from the outset marxism has both defended the equal status of the sexes as a condition sine qua non of communist society, and shown that women’s emancipation through wage labour is a precondition for this objective.

Nonetheless, it is undeniable that patriarchal attitudes remained deeply anchored in society as a whole, including in the working class: we will not be rid of millennia of patriarchy in a few decades. To assert their independence, women still had to organise separately in special sections within the unions and the socialist parties. Rosa Luxemburg’s example is striking in this respect: the SPD leadership thought they could reduce her influence by encouraging her to limit herself to the organisation of "women’s business" – something she refused outright. Propaganda sought to subvert solidarity with women by transforming it into the "chivalrous" protection of women, which of course is nothing but the counterpart to the reality of women’s inferior status within class society.

This idea of manly duty – more especially the duty of the knight – to protect “widows and orphans” and the poor and oppressed, strikes deep roots in European civilisation, going back to the medieval church’s efforts to establish its moral authority over the warrior aristocracy. It might seem far-fetched to connect the propaganda of 1914 with an ideology promoted for very different reasons a thousand years previously. But ideologies remain like a sediment in society’s mental structures, even when their material underpinning has long disappeared. Moreover, what one might call "medievalism" was used by both the big and small bourgeoisie in Germany and Britain – and so, by extension, in the United States – during the 19th century’s massive surge industrialisation in order to give a solid foundation to the national principle. In Germany, where national unity still remained to be built, there was an entirely conscious effort to create the vision of a "volk" united by a common culture; it is to be found, for example, in the Grimm brothers great project to resuscitate the popular culture of myths and legends. In Britain, the notion of "the liberties of free-born Englishmen" could be traced back to the Magna Carta signed by King John in 1206. The medieval idiom exerted a strong influence not only in church-building – no Victorian suburb would be complete without its mock-medieval church – but also on scientific institutions like the magnificent Natural History Museum, or on railway stations like St Pancras (both in London). Not only did workers live in a physical space marked by medieval imagery, the same idiom entered the workers’ movement, for example in William Morris’ utopian novel News from Nowhere. Even in the United States, the first real trade union called itself “The Knights of Labor”. The aristocratic ideals of “chivalry” and “gallantry” were thus very present – and very real – in a society which, on the level of day-to-day economic life, was given over to greed, the ruthless exploitation of labour, and a bitter conflict between the capitalist and proletarian classes.

If war propaganda diverted the solidarity between the sexes into a reactionary chivalric ideology, it also subverted the masculine solidarity between factory workers. In 1914, any worker knew the importance of solidarity in the workplace. But despite the International, the workers’ movement remained a collection of national organisations: day-to-day solidarity was towards familiar faces. It was above all the recruitment propaganda that made use of this themes, and nowhere more so than in Australia where there was no conscription. To show solidarity is no longer to struggle with your comrades against war, but to take your place alongside comrades in uniform, at the Front. Since this is necessarily a male solidarity, there are – as in the “defence of the family” - strong overtones of “manliness” in many of these posters.

Inevitably, pride and shame go together so that the proud assertion of masculinity that comes (or is supposed to come) with being part of a fighting corps, has its counterpoint in guilt at “not doing one’s bit”, at not sharing the manly suffering of one’s comrades. It was perhaps some such mix of emotions that drove the war poet Wilfred Owen to return to the front after recovering from a nervous breakdown, despite his horror at the war and his deep loathing for the ruling classes – and the yellow press – that he held responsible for this.39

Freud believed not only that the “group mind” was ruled by the emotional unconscious, but that it represented an atavistic return to a more primitive mental state characteristic of archaic societies and of childhood. The ego, with its usual self-conscious calculation of personal advantage, could be submerged in the “group mind” and in this condition would be capable of actions that the individual would not contemplate, both for better or for worse, becoming capable of great savagery or great heroism. Bernays and his propagandists undoubtedly agreed with this view, at least up to a point – but they were more interested in the mechanics of manipulation than with theory and they certainly did not share Freud’s deep pessimism about human civilisation and its prospects, above all after the experience of World War I. Where Freud was a scientist whose aim was to further humanity’s understanding of itself by bringing the unconscious to consciousness, Bernays – and of course his employers – were interested in the unconscious only insofar as it allowed them to manipulate a mass that must remain unconscious. Lasswell considers that one can participate in the “group mind” even when one is alone; he makes the point that propaganda seeks to be omni-present in the individual’s life, to take every opportunity (street hoardings, advertising in public transport, the press, etc.) to affect his thinking as a member of a group. We touch here on a whole range of questions far too complex to be treated in this article: the relationship between the individual’s psychology profoundly influenced by his personal history, and the prevalent “psychological energies” (for want of a better term) in society as a whole. But there can be no doubt, in our view, that these “psychological energies” exist, and that the ruling class studies them and seeks to use them in order to manipulate the mass for its own ends. Revolutionaries ignore them at their peril – not least because we do not exist outside bourgeois society and are also subjected to its influence.

Today, the war propaganda of 1914 can seem naïve, absurd, even grotesque. The 19th century’s naivety has been cauterised from society by two world wars and one hundred years of capitalist decadence and barbaric warfare. The development of cinema, television, radio, the omnipresence of the visual media, and the universal education demanded by the production process, have made society more sophisticated; it is also, perhaps, more cynical. But this does not make it immune from propaganda. On the contrary, not only have propaganda techniques been constantly refined, what was once merely commercial advertising has become one of propaganda’s principal forms. Advertising – as Bernays said it should – has long since ceased merely plugging products: it promotes a world-view within which the product becomes desirable, and this world-view is deeply, viscerally bourgeois (and petty-bourgeois) and reactionary (and never more so than when it pretends to be “rebellious”).

But the purposes of bourgeois propaganda is not only to inculcate, to propagate; it is also, perhaps even above all, to hide, to conceal. Let us remember Lasswell’s words quoted at the beginning of this article: “The war must not be due to a world system of conducting inter national affairs, nor to the stupidity or malevolence of all governing classes...”. The difference with communist propaganda is stark for the communists (as Rosa Luxemburg did in the Junius pamphlet) aim to reveal, to strip bare, to make comprehensible and therefore open to revolutionary change, the social order that confronts the working class. The ruling class seeks to submerge rational thought and conscious knowledge of social existence. The more "democratic" the society, the truer this is, for the greater the appearance of choice and "freedom", the more care must be taken to ensure that the population makes the "right choice" in complete freedom. Communist propaganda seeks on the contrary to help the revolutionary class to free itself from class society’s ideology, including when this is deeply rooted in the unconscious. It aims to ally rational consciousness with the development of the social emotions, and to make each individual aware of himself not as a helpless atom, but as one link in a great association extended not only geographically – because the working class is inherently internationalist – but also historically, into both the past and the future which we have yet to build.

Jens / Gianni, 7th June, 2015

1A book by the British pacifist Arthur Ponsonby, Falsehood in wartime, published in 1928, caused an enormous uproar by detailing the mendacious nature of the most widespread anti-German atrocity stories: it went through 11 print editions between 1928 and 1942.

2Edward Bernays (1891-1995) was born in Vienna, the nephew both of Sigmund Freud and of his wife Anna Bernays. His family moved to New York in the year after his birth, but as an adult he kept in close contact with his uncle and was deeply influenced by his ideas, as well as by the studies on crowd psychology published by Gustave Le Bon and William Trotter. By all accounts, he was deeply impressed by the impact that US President Woodrow Wilson made on European crowds when he toured the continent at the end of the war; he attributed this to the success of US propaganda for Wilson’s “14 Points” peace programme. In 1919 he opened an office as “Public Relations Counsellor” and became a well-known and highly influential manager of advertising campaigns for major US corporations, notably American Tobacco (Lucky Strike cigarettes) and United Fruit. His book on Propaganda can be seen as an advertising prospectus to potential clients.

3One classic early example of the symbiotic relationship between state propaganda and private PR is the 1954 publicity campaign, masterminded by Edward Bernays’ company on behalf of the United Fruit Corporation, to justify the CIA-sponsored overthrow of the newly elected Guatemalan government (which intended to nationalise uncultivated land owned by United Fruit), and its replacement by a military regime of fascist death squads, all in the name of “defending democracy”. The techniques used against Guatemala in 1954 were first sketched out by state propaganda departments during World War I.

4Harold Lasswell, Propaganda technique in the World War [4], 1927 (available online at https://babel.hathitrust.org/ [5]). Harold Dwight Lasswell (1902-1978) was one of the foremost American political scientists of his day, introducing for the first time into the discipline, new methods based on statistical measurement, content analysis, etc. He was especially interested in the psychological aspect of politics and the workings of the “group mind”. During World War II, he worked for the American army’s political warfare unit. Although raised in small-town Illinois he had a broad education, being introduced by one of his uncles to the work of Freud, and to the works of Marx and Havelock Ellis by one of his teachers. His 1927 doctoral thesis, from which we quote extensively in this article, was probably the first in-depth study of the subject.

5Edward Bernays, Propaganda, Ig Publishing, 2005, pp47, 48, 55.

6Lasswell, op.cit., p28)

7See Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War, Penguin Books, 1999, pp224-5).

8See also our article "Truth and memory, art and propaganda": https://en.internationalism.org/internationalreview/201502/12275/truth-a... [6]

9Ferguson, op.cit., p223

10Op.cit., p32.

11The “Four-Minute Men” were a remarkable and uniquely American invention. Volunteers would deliver a four-minute speech (on themes provided by the Creel Committee) at all kinds of places where an audience would be guaranteed: street corners during market days, in cinemas while reels were changed, and so on.

12Since the USA only entered the war in April 1917, they were delivering more than 1000 speeches every day. It is estimated that they were heard by 11 million people.

13Quoted in Lasswell, op.cit., pp211-212. We have limited ourselves to the most significant elements in Creel’s list.

14Cinema, despite being silent, was already a major medium of public entertainment. In Britain alone in 1917, there were already more than 4000 cinemas playing to audiences of 20 million every week (cf. John MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire, Manchester University Press, 1984, p69).

15Cf. Ferguson, op.cit., pp226-225

16We can take two admittedly extreme examples to illustrate this point: it was notorious, by the 1980s, that nobody in the Eastern Bloc countries believed any official propaganda; by the end of World War II, the German population no longer believed anything they read in print – with the exception, for some, of the horoscope, which was duly prepared every day by the Propaganda Ministry (cf. Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich, MacMillan 1970, pp410-411.

17“Wipers” being the English distortion of Ypres, the section of the front where a large part of the British army was concentrated and which saw one of the war’s most murderous engagements.

18The war was also financed through loans abroad, most importantly by France and Britain borrowing in the United States. “As [President] Woodrow Wilson put it, the beauty of having financial leverage over Britain and France was that ‘when the war is over we can force them to our way of thinking’” (Ferguson, op.cit., p329).

19Indeed, shortly before the outbreak of war the French had raised the duration of military service to three years.

20Lasswell, op.cit., p222

21Lasswell, op.cit., p221

22This was the public, official agitation of the International. Events were tragically to show that the International’s apparent strength hid a profound weakness which in 1914 led its constituent parties to betray the workers’ cause and lend their support to their respective ruling classes. See our article 1914: How the 2nd International failed [7].

23Lasswell, op.cit., p195

24Gustave Le Bon (1841-1931) was a French anthropologist and psychologist, whose major work La psychologie des foules was published in 1895.

25John Atkinson Hobson (1858-1940) was a British economist who opposed the development of imperialism, believing it contained the seeds of international conflict. Lenin drew extensively on (and polemicised with) Hobson’s major work Imperialism (1902), in his own Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism.

26“Jingoism” is an English term for aggressive patriotism, derived from a popular British song at the time of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877:

“We don't want to fight but by Jingo if we do

We've got the ships, we've got the men, we've got the money too

We've fought the Bear before, and while we're Britons true

The Russians shall not have Constantinople”.

27The “cultured surface” is not only a mask. Capitalist society also contains within itself a dynamic towards the development of culture, science, and art. To deal with this here however, would take too long and distract from our main argument.

28Or as Margaret Thatcher once said, there is no society, only individuals and their families.

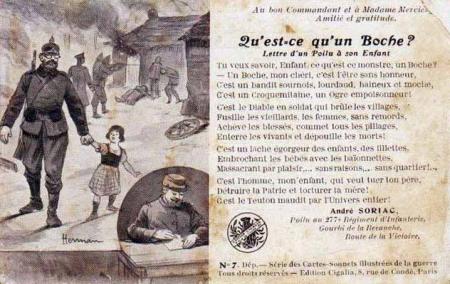

29The postcard contains a “poem” supposedly written by a French infantryman to his daughter on the theme “What is a Boche (perjorative French term for a German)?

“Do you want to know, child, what is this monster, a Boche?

A Boche, dear, is a being without honour,

A cunning heavy-handed bandit, full of hatred and ugly with it,

A Bogeyman, a poisoning Ogre!

He’s the Devil disguised as a soldier who burns down villages,

Shoots the old men and women, without remorse,

Finishes off the wounded and robs the dead!

He’s a cowardly cut-throat of children and little girls,

Spitting babies with his bayonet,

Killing for pleasure, for no reason, without pity!

This is the man, my child, who wants to kill your father,

Destroy the Fatherland and torture your mother!

This is the Teuton damned by the whole Universe!”

30Op. cit., p32

31We need only remember the example of the Vietnam war, where atrocities such as the My Lai massacre were frequent and attested.

32Cf. Lasswell, op.cit., p138

33Lasswell, op.cit., p88. Though one wonders whether one should consider it a “quality” of less “simple” minds that they should be capable of hating an entire nation without a hate figure to focus on...

34Freud, Group psychology..., quoted in Adorno, Freudian theory and the pattern of fascist propaganda.

35As can be imagined, this was deeply resented by men on leave from the front, when they found themselves being given a white feather, but it could also be devastating: the present author’s grandfather was a 17-year old apprentice in a Newcastle steel works when he was given a white feather by his own sister – driving him to enlist in the Navy by lying about his age.

36Given that – in a white-dominated patriarchal society – sexual predation was above all the fact of white males on black women, this would almost be funny were it not so vile.

37As was indeed the case, embryonically, in the 18th century: cf Howard Zinn’s People’s history of the United States.

38International Workers of the World.

39Owen’s motivations were certainly much more complicated, as they must be for an individual. He was also an officer, and felt a responsibility towards “his” men.

Historic events:

- World War I [8]

General and theoretical questions:

- Democracy [9]

People:

- Sigmund Freud [10]

- Edward Bernays [11]

- Harold Lasswell [12]

- Kaiser Wilhelm II [13]

- Edith Cavell [14]

Rubric:

Zimmerwald and the centrist currents in the political organisations of the proletariat

- 1935 reads

The article we publish here is a contribution by comrade MC to the internal debate of the 1980s, with the aim of fighting against centrist positions towards councilism within the ICC. MC was the signature of Marc Chirik (1907-1990), a former militant of the communist left and the main founding member of the ICC (see International Reviews nºs 61 and 62).

It may seem surprising that a text whose title refers to the Zimmerwald Conference held in September 1915 against the imperialist war was written in the context of an internal debate in the ICC around the question of councilism. In fact, as the reader will see, this debate was obliged to widen out to more general questions which had already been posed for a century and which are just as relevant today.

We have given an account of this debate on centrism towards councilism in issues nº40 to 44 of the International Review (1985-6). We refer the reader in particular to the article in issue nº 42 of the Review, “Centrist slidings towards councilism”. This article presents the origins of the debate which we will summarise here in order to make certain aspects of MC’s polemic more understandable.

At the 5th congress of the ICC, and especially afterwards, a series of confusions emerged within the organisation with regard to the analysis of the international situation; in particular, a position on the development of consciousness within the proletariat which was influenced by a councilist vision. This position was mainly put forward by comrades of the section in Spain (referred to as “AP” in MC’s text, the name of the section’s publication, Acción Proletaria).

“The comrades who identified with this analysis thought that they were in agreement with the classic theses of marxism (and of the ICC) on the problem of class consciousness. In particular, they never explicitly rejected the necessity for an organisation of revolutionaries in the development of consciousness. But in fact, they had ended up with a councilist vision:

by presenting consciousness as a determined and never a determining factor in the class struggle;

by considering that the ‘one and only crucible of class consciousness is the massive, open struggle’, which leaves no place for revolutionary organisations;

by denying any possibility of the latter carrying out the work of developing and deepening class consciousness in phases of reflux in the struggle.

The only major difference between this vision and councilism is that the latter takes the approach to its logical conclusion by explicitly rejecting the necessity for communist organisation whereas our comrades did not go as far as this.” 1

One of the major themes of this approach was the rejection of the notion of the “subterranean maturation of consciousness”, which actually meant excluding the possibility of revolutionary organisations developing and deepening communist consciousness outside the open struggles of the working class.

As soon as he became aware of the documents that expressed this point of view, our comrade MC wrote a contribution aimed at combating it. In January 1984, the plenary meeting of the central organ of the ICC adopted a resolution that took position on the erroneous analyses which had been expressed, in particular on the councilist conceptions involved:

“When this resolution was adopted, the ICC comrades who had previously developed the thesis of ‘no subterranean maturation', with all its councilist implications, acknowledged the error they had made. Thus they pronounced themselves firmly in favour of this resolution and notably of point 7 whose specific function was to reject the analyses which they had previously elaborated. But at the same time, other comrades raised disagreements with point 7 which led them either to reject it en bloc or to vote for it ‘with reservations', rejecting some of its formulations. We thus saw the appearance within the organisation of an approach which, without openly supporting the councilist theses, served as a shield or umbrella for these theses by rejecting the organisation's clear condemnation of them or attenuating their significance. Against this approach, the ICC's central organ was led in March ‘84 to adopt a resolution recalling the characteristics of:

‘opportunism as a manifestation of the penetration of bourgeois ideology into proletarian organizations, and which is mainly expressed by:

a rejection or covering up of revolutionary principles and of the general framework of marxist analyses;

a lack of firmness in the defence of these principles;

centrism as a particular form of opportunism characterised by:

a phobia about intransigent, frank and decisive positions, positions that take their implications to their conclusions;

the systematic adoption of medium positions between antagonistic ones;

a taste for conciliation between these positions;

the search for a role of arbiter between these positions;

the search for the unity of the organisation at any price, including that of confusion, concession on matters of principle, and a lack of rigour, coherence and cohesion in analyses.’

And the resolution concludes that ‘within the ICC at the moment there is a tendency towards centrism - ie towards conciliation and lack of firmness - with regard to councilism.’”2