ICConline - 2015

- 2269 reads

January 2015

- 1304 reads

Massacre in Paris: terrorism is an expression of rotting bourgeois society

- 2920 reads

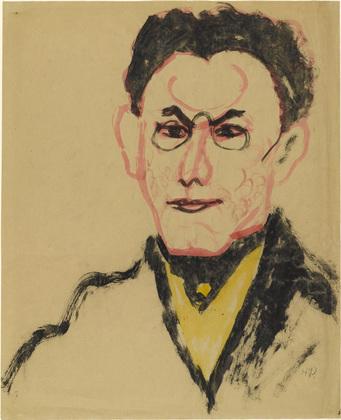

Cabu, Charb, Tignous, Wolinski, among the twenty killed in the attacks in Paris on 7 and 9 January, these four were a kind of symbol. They were the priority targets. And why? Because they stood for intelligence against stupidity, reason against fanaticism, revolt against submission, courage against cowardice1, sympathy against hatred, and for that specifically human quality: humour and laughter against conformism and dull self-righteousness. We may reject and oppose some of their political positions, some of which were totally bourgeois2. But what was being hit was what was best about them. This barbaric rampage against people who were just cartoonists or shoppers at a kosher supermarket, gunned down just because they were Jews, has provoked a great deal of emotion, not only in France but all over the world, and this is quite understandable. The way this emotion is now being put to use by all the licensed representatives of bourgeois democracy must not hide the fact that the indignation, anger and profound sadness which gripped millions of men and women, and led them to come out spontaneously onto the streets on 7 January, was a basic and healthy reaction against this despicable act of barbarism.

Cabu, Charb, Tignous, Wolinski, among the twenty killed in the attacks in Paris on 7 and 9 January, these four were a kind of symbol. They were the priority targets. And why? Because they stood for intelligence against stupidity, reason against fanaticism, revolt against submission, courage against cowardice1, sympathy against hatred, and for that specifically human quality: humour and laughter against conformism and dull self-righteousness. We may reject and oppose some of their political positions, some of which were totally bourgeois2. But what was being hit was what was best about them. This barbaric rampage against people who were just cartoonists or shoppers at a kosher supermarket, gunned down just because they were Jews, has provoked a great deal of emotion, not only in France but all over the world, and this is quite understandable. The way this emotion is now being put to use by all the licensed representatives of bourgeois democracy must not hide the fact that the indignation, anger and profound sadness which gripped millions of men and women, and led them to come out spontaneously onto the streets on 7 January, was a basic and healthy reaction against this despicable act of barbarism.

A pure product of the decomposition of capitalism

Terrorism is not new3. What is new is the form that it has taken and which has developed since the mid 80s to become an unprecedented global phenomenon. The series of indiscriminate attacks that hit Paris in 1985-86, which, clearly, was not carried out by small isolated groups but bore the signature of a state, inaugurated a new era in the use of terrorism that has reached hitherto unknown levels and claimed a growing number of victims.

The terrorist attacks by Islamist fanatics are not new either. The history of this new century has regularly witnessed this, and on a much greater scale than the Paris attacks of early January 2015.

The kamikaze aeroplanes that crashed into the Twin Towers in New York September 11, 2001, opened a new era. For us it is clear that the US Secret Service let it happen and even facilitated these attacks, which allowed the American imperialist power to justify and unleash the war in Afghanistan and Iraq, just as the Japanese attack against the naval base of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, foreseen and wanted by Roosevelt, had served as a pretext for the entry of the US into World War II4. But it is also clear that those who had taken control of the aircraft were completely delusional fanatics who thought they could gain entry to paradise by killing on a vast scale and sacrificing their own lives.

Less than three years after New York, March 11, 2004, Madrid was the scene of a terrible massacre: "Islamist" bombs caused 200 deaths and over 1,500 injuries in the Atocha station; human bodies were so mangled that they could only be identified by their DNA. The following year, on 7 July 2005, it was London that was struck by four explosions, also on public transport, killing 56 people and leaving 700 wounded. Russia also has experienced several Islamist attacks in the 2000s, including that of 29 March 2010 that killed 39 and injured 102. And of course, the peripheral countries have not been spared, especially Iraq since the US invasion in 2003 and as we saw again just recently in Pakistan, in Peshawar, where last December 141 people, including 132 children, were killed in a school5.

This attack, in which children were a deliberate target, shows, in all its horror, the increasing barbarism of these followers of "Jihad". But the attack in Paris on 7 January, although much less deadly and horrific than the one in Pakistan, expresses a new dimension of this slide into barbarism.

In all previous cases, however revolting the massacre of civilians, including children, there was some "rationality": it was to retaliate or attempt to pressure the state and their armed forces. The Madrid massacre of 2004 was meant to "punish" Spain for its involvement in Iraq alongside the United States. The same goes for the London bombings in 2005. The attack in Peshawar was aimed at putting pressure on the Pakistani military by slaughtering their children. But in the case of the attacks in Paris on January 7, there was not the slightest "military objective", even an illusory one. The Charlie Hebdo cartoonists and their colleagues were murdered to "avenge the Prophet" since the newspaper had published caricatures of Mohammed. And this happened not in a country ravaged by war or ruled by religious obscurantism, but in France, "democratic, secular and republican" France.

Hatred and nihilism are always a key driver in the activities of terrorists, especially those who deliberately sacrifice their lives to kill as massively as possible. But this hatred that turns humans into cold killing machines, with no regard for the innocent they kill, has as its main target this other "killing machine" - the state. None of that on 7 January in Paris: here obscurantist hatred and the fanatical thirst for revenge could be seen in their purest form. Its target is the other, the one who does not think like me, and especially the one who thinks, because I've decided not to think, that is to say, to exercise this faculty proper to the human species.

It is for this reason that the killings of 7 January caused such an impact. In a way, we are faced with the unthinkable: how can human minds, educated in a "civilized" country, get drawn into such a barbaric and absurd project similar to that of the most fanatical Nazis with their burning of books and extermination of the Jews?

And that’s not the worst of it. The worst part is that the extreme act of the Kouachi brothers, of Amedy Coulibaly and their accomplices, is only the tip of an iceberg of a whole movement that thrives mainly in poor neighbourhoods, a movement that was expressed when a number of young people put forward the idea that "Charlie Hebdo had it coming for insulting the prophet", and that the killing of the cartoonists was something "normal".

This is also a manifestation of the advance of barbarism, the breakdown in our "civilized" societies. This descent of a part of the youth, and not only those who have been through the process of immigration, into hatred and religious obscurantism - this is one symptom among many of the putrefaction of capitalist society, but a particularly significant pointer to the gravity of the present crisis.

Today, all over the world (in Europe as well, and especially in France), many young people with no future, living chaotic daily lives, humiliated by successive failures, by cultural and social poverty, become easy prey to unscrupulous recruiters (often related to states or political expressions such as ISIS) that drain these misfits into their networks through conversions as sudden as they are unexpected, turning them into potential hit men or cannon fodder for the "jihad". Lacking their own perspective on the current crisis of capitalism, which is an economic crisis but also a social, moral and cultural one; faced with a society that is rotting on its feet and oozing destruction from every pore, for many of these young people life seems pointless and worthless. Their despair can often take on the religious colouring of a blind and fanatical submission, inspiring all sorts of irrational and extreme behaviour, fuelled by a suicidal nihilism. The horror of capitalist society in decay, which elsewhere creates huge numbers of child soldiers (for example in Uganda, Congo and Chad, especially since the early 1990s) is now giving birth, in the heart of Europe, to young psychopaths, professional cold blooded killers, completely desensitised and capable of the worst without expecting any reward for it. In short, this rotting capitalist society, left to its own morbid and barbaric dynamics, can only lead the whole of mankind towards bloody chaos, towards murderous insanity and death. As can be seen from the growth of terrorism, it is producing more and more totally desperate individuals, who have been ground down to the point of being capable of the worst atrocities. In short, it moulds these terrorists in its own image. If such "monsters" exist it is because capitalist society has become "monstrous." And if not all the young people affected by this obscurantist and nihilistic trend enrol directly in "jihad", the fact that many of them regard those who have taken this step as "heroes" or as agents of "justice” constitutes proof of the increasing weight of despair and barbarism invading society.

The odious "democratic" recuperation

But the barbarism of the capitalist world is not expressed only in these terrorist acts and the sympathy they meet in a part of the youth. It is also expressed in the vile way that the bourgeoisie is recuperating these dramas.

At the time of writing this article, the capitalist world, headed by the principal “democratic” leaders, is about to carry out one of its most sordid operations. In Paris, on Sunday, January 11, a huge street demonstration has been planned, around President Holland and all the political leaders of the country, together with world leaders such as Angela Merkel, David Cameron, the heads of government of Spain, Italy and many other European countries, but also the King of Jordan, Mahmoud Abbas, President of the Palestinian Authority, and Benjamin Netanyahu, Prime Minister of Israel6.

While hundreds of thousands of people spontaneously took to the streets on the evening of January 7, the politicians, starting with François Hollande, and the French media began their campaign: "It’s the freedom of the press and democracy which are under threat "," We must mobilise and unite to defend the values of our republic. " Increasingly, in the gatherings that followed those of 7 January, we heard the French national anthem, the "Marseillaise," whose chorus says "water our furrows with the blood of the impure!" …"National Unity", "defence of democracy", these are the messages that the ruling class wants to get into our heads, that is to say the slogans which justified the dragooning and massacre of millions of workers in the two world wars of the twentieth century. Hollande also said it in his first speech: by sending the army into Africa, especially Mali, France has already begun the fight against terrorism (just as Bush explained that the US military intervention in 2003 Iraq had the same purpose). The imperialist interests of the French bourgeoisie obviously have nothing to do with these interventions!

Poor Cabu, Charb, Tignous, Wolinski! Fanatical Islamists killed them the first time. They had to be killed a second time by these representatives and "fans" of bourgeois "democracy", all these heads of state and government of a decaying world system that is responsible for the barbarism invading human society: capitalism. And these political leaders do not hesitate to use terror, assassinations, and reprisals against civilians when it comes to defending the interests of this system and its ruling class, the bourgeoisie.

The end of the barbarity expressed by the killings in Paris in January 2015 will certainly not come from the actions of those who are the main supporters and guarantors of the economic system that generates this barbarity. It can only result from the overthrow of this system by the world proletariat, that is to say, by the class whose association produces most of the wealth of society, and its replacement by a truly universal human community no longer based on profit, competition and the exploitation of man by man but based on the abolition of these vestiges of human prehistory. A society which will be "an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all" 7 , communist society.

Révolution Internationale (11/01/2014)

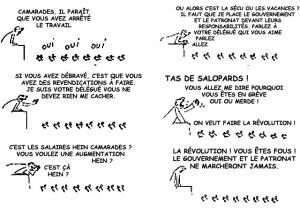

The cartoon is by Wolinski, from 1968: the workers call for revolution, the union official replies: “you’re crazy – the government and the bosses will never allow it!”

1� For years, these cartoonists had regularly been receiving death threats

2� Didn’t the ‘soixante-huitard’ Wolinski work for the Communist Party’s paper L’Humanité for several years? Didn’t he himself write “we made May 68 so as not to become what we did become?

3� In the nineteenth century, small minorities in revolt against the state, like the populists in Russia and some anarchists in France or Spain, resorted to terrorist acts. These sterile violent actions have always been used by bourgeois against the workers’ movement to justify and legalise repression

4� See the article on our website: ‘Pearl Harbor 1941, the 'Twin Towers' 2001: Machiavellianism of the US bourgeoisie’. https://en.internationalism.org/ir/108_machiavel.htm [1]

5� And only a few days before the Paris attacks, the Islamist Boko Haram group in Nigeria carried out its worst ever atrocity, indiscriminately slaughtering up to 2000 residents of the town of Baga. This has received only minimal media coverage.

6� The call for the rally for "National Unity" was unanimous on the part of unions and political parties (only the National Front will not be present), but also the media. Even the sports newspaper L’Équipe called for the demonstration!

7� Marx, The Communist Manifesto, 1848

Geographical:

- France [2]

General and theoretical questions:

- Decomposition [3]

- Religion [4]

- Terrorism [5]

People:

Recent and ongoing:

- Paris killings [10]

Rubric:

The film "Merry Christmas" and the real story of the 1914 Christmas Truce

- 5198 reads

NWF2JBb1bvM [11]

The article that follows was originally published in 2006 in French, following the box-office success of the French film "Joyeux Noël". If we are publishing it now, it is because the 1914 Christmas Truce has become something of a media celebrity 100 years after the event with its own website, and even an advert for Sainsbury’s supermarkets taking the Truce as a theme. Needless to say, the ruling class presents it as a victory for "humanity" but one which had no future: "inevitably" the war went on, the idea that the simple soldiers could take matters into their own hands and bring the war to an end by overthrowing the entire capitalist system that engendered it. We are invited to remember the Christmas Truce, the better to make us forget the revolutionary potential of fraternisation.

"The 1914-18 war as you have never seen it before at the cinema". So begins the enthusiastic review in the magazine Historia of Christian Carion’s film Joyeux Noël,1 which came to cinema screens on 9th November 2005 and has been selected to represent France at the 2006 Oscars.

"The 1914-18 war as you have never seen it before at the cinema". So begins the enthusiastic review in the magazine Historia of Christian Carion’s film Joyeux Noël,1 which came to cinema screens on 9th November 2005 and has been selected to represent France at the 2006 Oscars.

What is so great about this film that it should deserve such an enthusiastic reception?

The film’s producer has chosen to focus on a "special moment" in the vast butchery of the Great War: 24th December 1914, the first Christmas Eve since the outbreak of war the previous August. That evening, as Carion says in the novel inspired by his film, "the unimaginable happened". Despite the orders for mutual slaughter, despite the hatred for the "Hun" or the "Französe" taught them ten years before on the benches of their primary schools with just this war in view, the soldiers on each side of the front put down their guns, sang Christmas carols, then spontaneously left their trenches to shake hands and share wine, schnapps, bread and cigarettes. According to the military archives, in some places football matches were even organised for the following day. These fraternisations are the film’s subject-matter.

Obviously, the ruling class does not make just any film a candidate for an Oscar, especially when it deals with such a sensitive subject as the Christmas Truce. If it does so, then this is clearly a sign that Carion’s film suits it perfectly.

The scenes where we witness the soldiers’ fraternisation cannot help but leave us overcome with emotion. Nonetheless, the meaning – or rather the absence of meaning – that is given to the event itself comes as a slap in the face to the viewer, and is nothing less than a falsification of history.

In the end, the 1914 Christmas Truce is reduced to a mere, though beautiful, parenthesis in the war, quickly closed for "business as usual" must go on. The dialogue between the French, British and German officers is instructive in this respect:

"‘The war’s outcome won’t be decided this evening... Nobody could reproach us for putting aside our guns on Christmas Eve!’.

‘Don’t worry! It’s just for one night’ went on Horstmayer [the German officer], trying to ‘reassure’ his French opposite number".

In the novel’s epilogue, we can read the following conclusion: "Needless to say, the war reasserted itself (…) When Christmas 1915 came around, the General Staffs on each side had learned their lesson and left nothing to chance: they ordered the shelling of areas which they considered too peaceful. There were to be no more fraternisations as in 1914". End of story. To repeat the words of the French officer Audebert "the parenthesis was closed".

Even in 1914 the press, especially in Britain, was aware of the Christmas Truce and did nothing to hide it. On the contrary, the filled their columns with similar sentiments to those we find today in Merry Christmas. Thus we could read on the Manchester Guardian of 7th January 1915: "‘But they went back to their trenches’, a shrewd and inhuman observer from another planet might say, ‘and brutally continued to kill and be killed. Obviously there is nothing to be expected from such noble sentiments’. To which we would rightly reply that much remains to be done: Belgium must still be delivered from the terrible yoke that weighs her down and Germany must be taught that culture cannot be imposed by the sword".2

"The is still much to be done, so no more of this nonsense and let us return to our trenches" is precisely what Carion makes his soldiers say, for example when one of his main characters, the German soldier Nikolaus, refuses to desert as his girlfriend encourages him to do because after all "I am a soldier here! I have duties, obligations just like the others!".

It is in this cheap moralising that the film slides over into pure fiction, a fantasy of the ruling class which rewrites history to suit itself and so confiscates it from the working class.

The fraternisations of Christmas 1914 were no "miracles without a future", no "intermission before the next act of the terrible drama" in the words of the historian Malcolm Brown, joint author with Marc Ferro of Meetings in No Man's Land, which appeared in bookshops shortly before the film came out.

On the contrary, both before December 1914 and throughout the war, fraternisations took place repeatedly on all the fronts: on the Western front between German, British and French troops, on the Eastern front between Russians and Germans or Austro-Hungarians, or on the Italian front between Austrians and Italians. Everywhere saw the same scenes: sharing food, drink, or cigarettes passed between the trenches, the same attempts to exchange a few words (some deeply regretted their inability to speak the language of those opposite them). Soldiers would often agree to avoid killing each other (the historians speak of agreements to "live and let live"). Attempts at fraternisation were sometimes pushed to the point that officers were sometimes forced to ask the enemy’s artillery to force their troops back to their trenches.

The idea that the fraternisations had "no future" implies another untruth: the idea that they were "rare and limited". "Without a future" also means "without any hope of putting an end to the carnage". With the support of a whole army of historians, the film sets out to empty the events of any political content. As Marc Ferro says "They were a cry of despair against useless offensives, from soldiers at the end of their tether... But they were not a step towards a questioning of the war" and above all "they had no revolutionary content".

If there were a Nobel Prize for hypocrisy, Marc Ferro would be a serious contender. It is surely obvious that when soldiers who have been ordered to massacre each other, put down their guns and shake hands instead, this calls the war into question de facto.

"The fraternisations had no political meaning". On the contrary, they expressed the international nature of the working class, the fact that workers have no interest in massacring each other for the interests of their exploiters and the nation. The fraternisations, and then the mutinies that came after December 1914 expressed a growing revolt within the working class, at the front and in the rear, against the suffering imposed by the war, which reached a crescendo in the Russian Revolution of 1917. There is no lack of examples of the implications of the Christmas Truce. The French corporal Louis Barthas writes in his war diaries3 that in the sector of Neuville-Saint-Vast the trenches flooded and French and German soldiers left them to fraternise. Later, after giving a short speech, a German soldier broke his rifle in a gesture of anger and "both sides applauded, and sang the Internationale". Another French soldier reports in January 1917 that "The boches [French slang for the Germans] made signs with their rifles that they would not fire on us and if they were forced to they would raise their rifle-butts in the air" (a well-known signal for mutiny). According to Barthas again, this time in the Vosges in 1917: "one [German] soldier took his rifle, waved its butt in the air, and finally aimed it not at us, but towards the German rear. It was very explicit and we concluded that he meant to say that they should shoot not at us but at those who led them".

The workers’ movement understands very well the value and the meaning of the fraternisations. In an article in Pravda (28th April 1917), Lenin expressed it very well: "The capitalists either sneer at the fraternisation of the soldiers at the front or savagely attack it (…) The class-conscious workers, followed by the mass of semi-proletarians and poor peasants guided by the true instinct of oppressed classes, regard fraternisation with pro found sympathy. Clearly, fraternisation is a path to peace. Clearly, this path does not run through the capitalist governments, through an alliance with them, but runs against them. Clearly, this path tends to develop, strengthen, and consolidate fraternal confidence between the workers of different countries. Clearly, this path is beginning to wreck the hateful discipline of the barrack prisons, the discipline of blind obedience of the soldier to “his” officers and generals, to his capitalists (for most of the officers and generals either belong to the capitalist class or protect its interests). Clearly, fraternisation is the revolutionary initiative of the masses, it is the awakening of the conscience, the mind, the courage of the oppressed classes; in other words, it is a rung in the ladder leading up to the socialist proletarian revolution.

Long live fraternisation! Long live the rising world-wide socialist revolution of the proletariat!"4

This is the reality that the film Merry Christmas obscures. It highlights the fraternisations of 1914 only to hide their content and their future significance in the outbreak of proletarian revolution in Russia 1917. For all its humanist and pacifist sentiments, this kind of film renders the fraternisations meaningless, to confiscate the working class’ memory, and so its revolutionary perspective.

Azel, 2nd January 2006

1Christian Carion’s own reflections on the making of the film can be found on the BBC web site.

2This quotation, taken from our article, has been translated back from the French. We hope to have rendered the spirit if not the exact words of the original.

3Les carnets de guerre de Louis Barthas, tonnelier, 1914-1918, Éditions La Découverte, 2003

4Pravda (28th April 1917), https://marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/apr/28e.htm [12]

Historic events:

- World War I [13]

- Christmas Truce [14]

Rubric:

February 2015

- 1334 reads

Doctor Bourrinet, fraud and self-proclaimed historian

- 6102 reads

On 8th November 2014, a conference was held in Marseille on the subject of "The radical left of the 1920s, internationalism and proletarian autonomy".

Before we give an account of the meeting itself, we aim to provide our readers with some background information on the conference speaker, Philippe Bourrinet, presented in the publicity as "the author of various articles and books on the revolutionary workers’ movement and a member of the Smolny press collective".1 Otherwise, it would be impossible to understand either Philippe Bourrinet’s presentation or the discussion that followed.

One might paraphrase Marx’s famous polemic against Proudhon2 as follows:

"Philippe Bourrinet has the misfortune of being peculiarly misunderstood. Among those who are interested in or claim to belong to the Communist Left, he passes for a serious and honest historian. Among historians, he passes for a defender of the Communist Left’s ideas and a connoisseur of its main organisation, the ICC, since everybody knows that he was a militant of the ICC for more than fifteen years. As militants of the ICC, and therefore attached to a serious and honest understanding of history (though we do not claim to be historians), we desire to protest against this double error".

As a foreword to our protest against the ignorance of which Philippe Bourrinet is a victim, let us revisit a few episodes of his political career, since this will allow us to refute many of the false ideas about him which are in circulation these days.

Philippe Bourrinet as a militant of the ICC

After a short stay in the ranks of the Trotskyist organisation Lutte Ouvrière, at the beginning of the 1970s Philippe Bourrinet entered the Révolution internationale group, shortly thereafter to become the section in France of the ICC. Since he had a ready pen and extensive knowledge, he was soon given the responsibility of writing articles for the organisation, under the name of Chardin. He also entered the ICC’s central organ shortly after its creation in 1975, one of the reasons for this nomination being his linguistic ability, notably in German.

Philippe Bourrinet had begun his studies in history, and it was agreed between him and the ICC that he should devote his Master’s dissertation to a study of the Italian Communist Left, so that this could be published by our organisation as a pamphlet. He received the fullest support for this work, which of course benefited his own university career, from our organisation: not only material support but also political support, since our comrade Marc Chirik,3 who had been a member of the Italian Left, provided him with an extensive documentation and first-hand information, as well as precious advice. As planned, his dissertation was published shortly afterwards by our organisation, in book format. Considered as a work of the ICC, and putting forward the ICC’s analyses, it was unsigned, like all our pamphlets.

After the book was published, we encouraged Philippe Bourrinet to undertake a similar study of the Dutch-German Communist Left for his doctoral thesis. The first chapters were published in issues 45, 50, and 52 of the ICC’s International Review. Once again, Philippe Bourrinet benefited from the ICC’s complete political and material support.4 He submitted his thesis in March 1988, and we then began the long work on the book’s layout, delivering it to the printers in November 1990; Philippe Bourrinet had left the ICC a few months beforehand. He gave no political reasons for his resignation, saying only that he no longer wanted to be a militant.

Philippe Bourrinet, member of the "Société des Gens des Lettres"

Two years later, we received in our PO Box, without the slightest accompanying letter, a copy of two surprising documents [15]. The first, dated 21/08/1992, was the "Receipt for the submission by Philippe Bourrinet of a manuscript entitled The Dutch Communist Left 1907-1950". This receipt was issued by the copyright department of the Société des Gens des Lettres.5 The second document, dated 27th July 1992, was even more surprising. It was a typewritten text titled "Concerning the anonymous publications distributed by the International Communist Current group (ICC) in France and elsewhere".

In this document, we read that "The book titled THE DUTCH LEFT, signed ‘International Communist Current’, printed in November 1990 by the ‘Litografia Libero Nicola, Napoli’ and distributed in France and Belgium, was entirely written by Philippe BOURRINET, doctor at the University of Paris 1 – Sorbonne (22nd March 1988)". This was perfectly true. But there followed a series of allegations, accusing the ICC of "piracy", which we desired to clarify with Philippe Bourrinet. Accordingly, a delegation from the ICC met him in a café on the Place de Clichy in Paris, close to where he lived at the time. This delegation pointed out to Philippe Bourrinet the truth of the matter, none of which he attempted to contradict. The delegation asked him why, all of a sudden, he was making such a fuss about his name not appearing on the book on the Dutch Left, since he had never before made this demand. He replied that it would be useful for him to appear as the book’s author in view of an upcoming job application, and that he wanted his name to figure on future editions. Although in his statement, Philippe Bourrinet had made a series of outrageous attacks against the ICC, we decided not to hold it against him: we did not, for example, put anything in the way of his professional ambitions. We decided to accede to his demand, but since the French edition had already been printed we told him that it was too late for this version of the book, on which he agreed. We therefore undertook to publish in any future edition, the following brief statement: "This book, which first appeared in French in 1990, is published under the responsibility of the ICC. It was written by Philippe Bourrinet in the context of his work for his university doctorate, but it was prepared and discussed by the ICC when the author was one of its militants. For this reason it was conceived and published as the collective work of the ICC, without an author's signature and with his total agreement.

Philippe Bourrinet has not been in the ICC since April 1990, and he has since published editions of this book under his own name, with the addition of certain 'corrections' linked to the evolution of his political positions.

For its part, the ICC fully intends to continue its policy of publishing this book. It should be clear that our organization cannot be held responsible for any additional or divergent political positions that Philippe Bourrinet might integrate into the editions produced under his own responsibility."6

Philippe Bourrinet accepted this proposal.

For the ICC, the matter was closed and we no longer paid much attention to the career of Doctor Bourrinet.7 Our inattention was all the greater in that his later literary efforts were of incomparably lesser quality and interest than the two books on the Italian and Dutch-German Lefts. We did of course notice, on the Internet, that Doctor Bourrinet had republished the two documents, with a few modifications of the ICC’s original which brought the text closer to the positions of councilism. It turned out that in the Postface to the new edition of the Dutch-German Left, Doctor Bourrinet wrote: "The present edition contains defects inevitable in a work carried out within the university framework. There also appears the author's membership of the aforementioned group [the ICC], in the form of traces of ideology at a remove from a rigorous marxist analysis of the revolutionary movement and theory (…) I have tried as far as possible to remove or diminish the passages which contained too much ‘anti-councilist’ polemic, specific to the group whose influence I was under at the time".

In this passage, we learn several things. First, that Doctor Bourrinet had to leave the ICC to acquire at long last "a rigorous marxist analysis of the revolutionary movement and theory". He forgets to mention that it was the Révolution Internationale group (the future ICC section in France) which taught him the basics of marxism, when he had just left Lutte Ouvrière, a group which – whatever its claims to the contrary – has nothing to do with either marxism or the revolutionary movement. He also accredits the idea – so popular with university "marxism" – that one can remain a "marxist" while avoiding any form of political organisation fighting for the defence of proletarian principles. This idea is very close to degenerate councilism’s rejection of the need for such an organisation – which explains why so many "marxist professors" have such an affinity with councilism. We could answer Doctor Bourrinet’s viewpoint with these words of the ICC militant... Philippe Bourrinet: "Unlike the Otto Rühle variety of ‘councilism’ in the 1920s, or the Dutch variety in the 1930s, today’s councilist current has broken with the ‘council communist’ tradition of the Communist Left. It corresponds much more to the revolt of fractions of the petty bourgeoisie or of proletarian elements suspicious of any political organisation. The councilist danger of tomorrow will not appear with the defeat of the revolution, as was the case during the 1920s in Germany, it will appear at the beginning of the revolutionary wave and will be the negative moment of the proletariat’s coming to consciousness" (from the Proceedings of a study day on the danger of councilism, held by the ICC’s section in France in April 1985, p19).

"Workerism co-exists only too well, one can even say perfectly, with intellectualism. In this sense, we have seen a kind of petty-bourgeois anarchism, in the sense of the rejection of any form of authority or organisation, etc, etc; similar to the vision of the workerist intellectual already condemned by Lenin in What is to be done?" (ibid., p32).

And finally, we learn that at the time, the militant Philippe Bourrinet made these mistakes because he was "under the influence". Doctor Bourrinet, just for once you are far too modest!8 The militant Philippe Bourrinet was not "under the influence" of the ICC’s positions, on the contrary he was their determined and talented defender in the organisation’s struggle against the tendencies towards councilist positions in its midst. This is precisely why the ICC entrusted him with the article that took up the cudgels publicly against these tendencies (See International Review no.40, "The function of revolutionary organizations: The danger of councilism").

Having revised the two texts on the Italian Left and the Dutch-German Left, Doctor Bourrinet had new editions printed, which he put on sale on the Internet. These texts obviously had slightly more content and slightly fewer errors than those published by the ICC. Amongst other things, they expressed the good Doctor’s new theoretical line. And these changes were of considerable value: whereas the ICC sold its book on the Dutch-German Left for 12 euros, the good Doctor’s price was 75€ [16]. Similarly for the Italian Left, the price was not 8€ but 50€ [17] (40€ for the English edition [18]).9 Of course, the good Doctor’s editions had colour covers! In a famous letter of 18th March 1872 to the French publisher of Capital, Marx wrote "I welcome your idea of publishing the translation of Das Kapital as a periodical. In this format it will be more accessible to the working class, and for me this consideration overrides all others". Clearly, this is not the kind of consideration that carries much weight with Doctor Bourrinet, whose methods are more like those of the private medical Doctors whose fees are ten times higher than those of the general practitioner, with the added benefit of allowing them to avoid any contact with the sweaty masses.

Is stinginess the explanation for the exorbitant prices of Doctor Bourrinet’s works? Not impossible, since the militant Philippe Bourrinet was known for his stinginess in the ICC, and got teased for it by Marc Chirik, at the time the treasurer of the ICC’s section in France. That said, it is unlikely that the good Doctor’s avarice, however obsessive it might be, has rendered him completely stupid. Even an idiot can see that the Doctor’s works are unlikely to find any buyers, even if the ICC were to put an end to its own distribution as the Doctor never stops demanding that we do.10 More likely, the Doctor’s elevated prices are no higher than his elevated esteem for his works and his own good self. To sell his literary production "on the cheap" (and it must be more valuable, in his estimation, than Capital), would be to minimise their value, according to the classic and contemptible bourgeois logic which we have already seen in his appeal to the "Société des Gens des Lettres". If our explanation is incorrect, Doctor Bourrinet need only supply his own, which we will gladly publish, as well as any reply he cares to give to this article.

Doctor Bourrinet, liar and slanderer

But all these examples of Doctor Bourrinet’s petty-mindedness and bad faith pale into insignificance beside the slander he directed at our organisation in 1992. We did not react publicly at the time; we intend to do so now, because since March 2012 they have been smeared across the Internet. On the site www.left-dis.nl/f/ [19] there is now a title "Une mise au point publique (Paris, décembre 91) sur le parasitisme 'instinctif' de la secte 'CCI'. Mars 2012" ("Public statement (Paris, December 1991) on the ‘instinctive’ parasitism of the ‘ICC’ sect"). The title links to a PDF11 containing all the above-mentioned documents received by the ICC in 1992, to which we will now return.

In the "Statement" of 27th July 1992, we read:

"On the occasion of the publication of the author’s doctoral thesis, and of his previous Master’s dissertation on the Italian Communist Left (1926-1945), without the author's agreement, and with arbitrary additions and cuts made by this group, which thinks it owns the document under the pretext that the undersigned author was once a member of the ICC, the following clarification is necessary for the reader:

This work was published anonymously by the ICC in 1991, in French, without the author's agreement and without warning him in advance, and without his corrections. The author was confronted with a fait accompli, a veritable act of ‘piracy’.

[There then follows the passage quoted above in which we learn that Philippe Bourrinet is a doctor of the University of Paris 1, and another giving the circumstances in which he submitted his thesis.]

This book is a continuation of that on THE ITALIAN COMMUNIST LEFT 1912-1945, a Master’s dissertation by the same author (Paris 1 – Sorbonne, 1980, supervised by Jacques Droz).

This dissertation was published in 1981 and 1984, anonymously – in French and Italian – by the ICC group, with the tacit, and only the tacit, agreement of the author".

Let us begin with "the tacit, and only the tacit, agreement" that the militant Philippe Bourrinet gave for the publication of the work on the Italian Communist Left, without mentioning the author's name. What is this can of worms Doctor Bourrinet, you pitiful hypocrite? Did you or did you not agree that the text you wrote should be published as an ICC pamphlet? When you discussed at length with other militants of the organisation, about the layout and the cover for this pamphlet (where indeed, the author's name does not figure), did you do so "tacitly"?

As for the work on the Dutch-German Left, which was supposedly published without the agreement of the shiny new "Doctor" Bourrinet, we’re surprised your nose didn’t get in the way when you were writing: it must have stuck out further than Pinocchio’s! Really Doctor Bourrinet, you are the most arrant liar to pretend that you were confronted with a "fait accompli". And here is the proof that you are a liar, in an article published in our International Review no.58 (3rd Quarter 1989) and titled "Contribution to a history of the revolutionary movement: Introduction to the Dutch-German Left", where we read: "The history of the international communist left since the beginning of the century, such as we've begun to relate in our pamphlets on the ‘Communist Left of Italy' isn't simply for historians. It's only from a militant standpoint, the standpoint of those who are committed to the workers' struggle for emancipation, that the history of the workers' movement can be approached. And for the working class, this history isn't just a question of knowing things, but first and foremost a weapon in its present and future struggles, because of the lessons from the past that it contains. It's from this militant point of view that we are publishing as a contribution to the history of the revolutionary movement a pamphlet on the German-Dutch communist left which will appear in French later this year. The introduction to this pamphlet, published below, goes into the question of how to approach the history of this current".

Who then is the slimeball of an ICC militant, justifying in advance the "piracy" of Doctor Bourrinet’s thesis, the willing accomplice in a manoeuvre intended to confront the good Doctor with a "fait accompli"? The article is signed Ch, alias Chardin, alias... the militant, Philippe Bourrinet.

So here we have the militant Philippe Bourrinet ("under the influence" in all likelihood), who takes responsibility publicly and in writing for the ignominious crime that the ICC is about to commit on poor Doctor Bourrinet. But, at the moment that this article is written, he has already received his doctorate from the University of Paris 1 – Sorbonne. In other words, one of those most responsible for the infamous acts against Doctor Bourrinet, is none other than Doctor Bourrinet himself. Is Doctor Bourrinet a masochist? At all events, he is certainly an out and out liar, of that there is no shadow of a doubt. A contemptible liar and slanderer.

The threats of Doctor Bourrinet the shopkeeper

One might imagine that Doctor Bourrinet could not stoop any lower than he did in March 2012, with this publication of his 20-year old documents: if so, one would be mistaken. At the same time, several militants of the ICC received a registered letter dated 23rd March 2012 [20], from the Legal department of the Société des Gens des Lettres. Here follow the main passages:

"We intervene in the name of Mr Philippe Bourrinet, member of the Société des Gens des Lettres, on the matter of his dissertation and his theses (…)

We are most surprised to discover that these two works are the object of systematic forgery, thus damaging both the property rights and the moral right of Mr Bourrinet.

We therefore ask that you immediately cease all use of these texts, either on the different Internet sites where they may be found, or in printed publications.

If he does not obtain satisfaction, the author reserves the right to take any action he deems appropriate".

In other words, Doctor Bourrinet "reserves the right" to set the law on certain ICC militants, should the ICC continue to distribute the books on the Dutch-German and the Italian Left. And the best of it is, that one of the militants targeted by this threatening letter was also one of those who was most involved in giving Doctor Bourrinet material support for his thesis, by using the photocopying services at his job (at the risk of getting into serious trouble with his employer, up to and including the sack), to copy hundreds upon hundreds of pages (drafts of Philippe Bourrinet’s work so that it could be proofed by other militants, collections of publications of the Communist Left that had been lent to him, copies of his dissertation and thesis for the University...).

Today, Doctor Bourrinet – with his characteristic cowardice, since he hides behind the Société des Gens des Lettres, who he has got on-board by lying to them – has the ludicrous pretension to lay claim to the heritage of the Communist Left, and to texts of the workers’ movement which belong to nobody if not to the working class, and of which proletarian organisations are the custodians, and the political and moral guarantors. This philistine thinks he can behave like any vulgar capitalist protecting his patents, putting it about that the product of the universal history of the exploited class is a commodity that can be reduced to the "intellectual property" of his own pathetic individuality. This is the merest swindle, a takeover bid worthy of Hollywood. The working class does not produce militants as individuals, but revolutionary organisations which are the product of struggle and a historic continuity. This is already contained in the 1864 Statutes of the IWA: "In its struggle against the collective power of the possessing classes the proletariat can act as a class only by constituting itself as distinct political party, opposed to all the old parties formed by the possessing classes." (Article 7a). Workers’ organisations defend principles which are the fruit of historical experience. In this sense, the work of their militants is part of a movement which is not and cannot be their "personal property". The ICC’s statutes state with the utmost clarity something which was once a morally self-evident fact within the proletariat: "every militant who leaves the ICC, even as part of a split, returns to the organisation all the material means (money, technical material, stocks of publications, internal bulletins etc.) which had been put at the militants disposal" (our emphasis).

Here then is Doctor Bourrinet’s true face! Grab his swag, and then turn to bourgeois justice out of personal vengeance and to flatter his injured vanity. This violation of his initial moral commitment, when he was a militant, is not merely pitiful, it is completely foreign to the workers’ movement. This pettifogging, petty-bourgeois legalism, fuelled by personal revenge, is something unheard of in the Communist Left that this fraud claims to defend. What terms should one use to speak of Doctor Bourrinet? So many spring to mind that we are left at a loss which to choose, so let us just say that he is "unspeakable".

Doctor Bourrinet slanderer of our comrade Marc Chirik

This is not the end of the unspeakable Doctor’s exploits. Not only is he ready to use the vilest methods to damage his one-time organisation, the ICC, he also sets out to attack the memory of a militant who played a determining role in its formation: Marc Chirik, deceased in December 1990.

To this end, he uses a biographical sketch published on his web site [21], and which includes, amongst others, those published at the end of his new version of the book on the Italian Left.

In the biographical sketch published at the end of the book, he permits himself a petty attack on Marc Chirik: "For Jean Malaquais, the friend of a lifetime, he embodied a certain kind of political ‘prophet’". On Doctor Bourrinet’s web site, the sentence is longer and the attack more open: "For Jean Malaquais, the friend of a lifetime, he embodied a certain kind of political ‘prophet’, constantly trying to prove to others and to himself that he had ‘never made a mistake’".12 We recognise here the style of the two-faced Doctor Bourrinet. He starts with the "friend of a lifetime" the better to put over a negative image, without saying that while Malaquais was a great writer and a fine polemicist who shared the positions of the Communist Left, he did not have the personality of a communist militant, nor an understanding of what it means to be one. In the days when Malaquais lived in Paris and came frequently to our public meetings, he asked at one point to join the ICC; Marc Chirik had little difficulty persuading the other comrades that we could not accept his candidature, given his often haughty attitude both to our militants and to our activities.

This sketch of Marc Chirik is petty-minded sniping, but worse is to come. In an addition, Doctor Bourrinet repeats the vilest slanders put about against our organisation, in particular by the pack of hooligans and grasses that called itself the "Internal Fraction of the ICC":

"In 1991-93, very shortly after his death, Marc Chirik’s group was shaken by a furious ‘war of succession’ between the ‘leaders’ to put themselves at the head of the ‘masses’ of the ICC, in reality the most grotesque conflicts worthy of an asylum".

Doctor Bourrinet then passes the microphone to the "adversaries" of our comrade and our organisation, to heap a cartload of muck on both:

"For his political adversaries, Marc Chirik remained a figure of the past, attached to the worst aspects of the Leninist and Trotskyist current, a remote disciple of Albert Treint, stooping to ‘Zinovievist’ manoeuvres and not hesitating – during yet another split, in 1981, to carry out ‘Chekist raids’ against ‘dissidents’, to ‘defend the organisation’ and to ‘recover its equipment’.

Exercising a monolithic control over ‘his’ organisation, Marc Chirik thus helped to plunge it, from an early stage, into a sort of paranoid psychosis. A sombre reality which, in the eyes of many ex-militants, tore apart the ‘Chirikist’ organisation, whose most visible defects were: political dishonesty raised to the level of a categorical imperative, ‘police tactics of harassment’, a carefully cultivated atmosphere of ultra-sectarian paranoia using the ‘theory of the plot’ ad nauseam, and recommending, to resolve political divergences, the prophylactic eradication of the ‘parasitism’ of ‘enemy organisations’.

To conclude:

-

a triumphant (and accepted) return of ‘repressed’ Stalinism in ‘praxis’;

-

a superficial attachment to the ‘acquisitions of Freudianism’ where the ‘struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie’ lives alongside ‘the eternal struggle of Eros and Thanatos’, and between ‘good’ and ‘evil’, the latter being the ‘proletarian morality’ of which the ICC is the custodian through its ‘central organs’;

-

a quasi-religious devotion to Darwinism, as a method for ‘selecting’ the most ‘adapted’ political species, under cover of the development of the ‘social instinct’ of which the ICC is the ultimate incarnation;

-

under the ‘virtuous’ mantle of ‘proletarian morality’, the triumph behind the scenes of political amoralism, the ‘eternal return’ of ‘Nechaev’s catechism’ where anything goes to destroy a political enemy".

As anyone can see, the accusations repeated by Doctor Bourrinet are not only aimed at Marc Chirik and the ICC when he was alive, but largely post-date his death. For example, the ICC never discussed Darwinism or published articles on the subject in Marc Chirik’s lifetime. Only since 2009, 20 years after his death, did the ICC deal with the question in our internal discussions or publish articles on the subject. In fact, Doctor Bourrinet’s intention is to kill two birds with one stone: to demolish both Marc Chirik and the ICC, whose principal founder he was.

In fact, this veritable inventory of accusations offers us a condensed version of the "Bourrinet method". He bows to the formal respect of historiographical standards by following his sketch with a bibliography where, indeed, we can find the sources for all these insanities. But so vast is this bibliography that the slanderous publications are drowned there. Moreover, it is difficult even for a "specialist" to access many of the texts referred to, such that most readers are unlikely to check "who said what". And this is precisely what counts. If one were to include, in a biography of Trotsky, a passage on what his political adversaries said about him, and if amongst the accusations were one claiming that he had been "an agent of Hitler", then the mere fact that the accusation came from Vyshinsky, the prosecutor at the Moscow trials, would be enough to discredit it. We have no intention of burdening the reader with a systematic refutation of all the slanders directed at Marc Chirik and the ICC in the articles so obligingly referenced by the good Doctor. Suffice it to say that for the most part they come from ex-members of the ICC who, for whatever reason, are eaten up by a tenacious hatred for our organisation. Some are still under the influence of anarchist ideas which have lead them to adopt the slogan "Lenin=Stalin". Others have felt that the organisation did not appreciate their true worth, or couldn’t face up to criticism and found that the defence of their hurt pride was more important than the defence of communist positions. Others have distinguished themselves by thuggish behaviour, while still being ready to call the police when the ICC visited them to recover equipment stolen from our organisation. Still others – or the same – continue to defend the dubious element Chénier, excluded in 1981, and who was shortly after to be found making a career for himself in the Socialist Party then in power.

If Doctor Bourrinet repeats certain accusations whose absurd, and even insane, character is obvious to anyone, it is probably not because he thinks that they will be believed as such, but because they make it possible to put about the idea that "there’s no smoke without fire", and that "even if it’s exaggerated, there must be some truth behind it". The Bourrinet method again: if you throw enough mud, something will always stick.

One final word on this. Doctor Bourrinet has written biographical notes of many militants of the Communist Left, but only Marc Chirik has had the privilege, of having not only his militant life, but also the accusations made against him, exposed in detail. All this without, needless to say, so much as a word about, or a reference to the texts (articles, interventions on forums, etc.) which refute these accusations, and all this in the name of "serious", "honest" historical research!13

Let us return then to the idea that Doctor Bourrinet is "a serious and honest historian". As Marx put it, we must "protest" against any such idea. In his 1989 article for our press, announcing the forthcoming publication of the ICC’s Dutch-German Communist Left, the good Doctor referred to several serious and honest historians of the workers’ movement: Franz Mehring, Leon Trotsky, both revolutionary militants, but also George Haupt, who was "far from being a revolutionary" to use Doctor Bourrinet’s words: "On this point it's worth again citing the historian Georges Haupt, who died in 1980, and was known for the seriousness of his works on the IInd and IIIrd Internationals:

‘With the aid of unprecedented falsifications, treating the most elementary historical realities with contempt, Stalinism has methodically rubbed out, mutilated, remodelled the field of the past in order to replace it with its own representations, its own myths, its own self-glorification(...)’".

The least one can say is that the same "probity" hardly characterises Doctor Bourrinet. As we have seen, he hesitates not a moment to proffer the most colossal lies when it suits him – whenever historical reality does not fit his own "self-glorification". When he was a militant of the ICC, Doctor Bourrinet produced work that was interesting, important, and honest. Since then, it is possible that some of his studies may have been honest, if not necessarily interesting or important. But what is sure, is that his honesty flies out the window whenever the subject concerns his obsessive pet hates: the militant Marc Chirik and the International Communist Current. After all, there are Stalinist historians who have produced excellent studies of the Paris Commune, but it would be too much to expect that they would be capable of doing the same for the history of the "Communist" Parties.

As far as the other illusions about Doctor Bourrinet are concerned – that he is "a defender of the Communist Left’s ideas and a connoisseur of its main organisation, the ICC" – here again, what we have said above shows that these are far from the truth. As a connoisseur of the ICC, we have seen better: either he takes the insane accusations of the ICC and Marc Chirik’s "political adversaries" at face value, in which case his "knowledge" is worthy of Hello! magazine or Minute,14 or he does not, which is worse. As for the defence of the ideas of the Communist Left, there is nothing to expect from someone whose overriding obsession is the defence of... his intellectual property, and who, to do so, has no hesitation in bringing in the bourgeois state. When one claims to defend certain ideas, the least that can be expected is that one does not act in flagrant contradiction to those ideas. There is nothing to be expected of someone who is devoured by hatred to the point where he can cover in shit the memory of Marc Chirik, one of the very rare militants of the Communist Left who, rather than remaining welded to his initial positions, was capable of integrating the essential insights of both the Italian and the Dutch-German Communist Left, and defending them to his dying day.

For Doctor Bourrinet, the ideas of the Communist Left are mere stock in trade, inherited from the days when he was a militant, and which he is trying as best he can to capitalise in the service of his need for social recognition (since he can’t make any money out of it).

Doctor Bourrinet, the petty-bourgeois democrat

To demonstrate this assertion conclusively, it is worth reading the biographical sketch devoted to Lafif Lakhdar (deceased July 2013), published on the site Controverses which presents itself as a "Forum for the Internationalist Communist Left" – a sketch signed Ph B (the good Doctor, in person no less).15 In the introduction, Lafif Lakhdar is presented as "an Arab intellectual, writer, philosopher and rationalist, a militant in Algeria, the Middle East and France. Known as ‘the Arab Spinoza’". In the sketch itself, we learn that "From 2009 onwards he took part, with the philosopher Mohammed Arkoun (1928-2010), in UNESCO’s Aladdin project, an ‘intellectual and cultural programme’ launched with the patronage of UNESCO, Jacques Chirac, and Simone Weil". We also learn that "In October 2004, he co-authored, together with numerous liberal Arab writers, a Manifesto published on the web (www.elaph.com [22], www.metransparent.com [23]) calling on the UN to set up an international tribunal to judge terrorists, and organisations or institutions inciting terrorism". Frankly, we have great difficulty seeing what this biography is doing on a "Forum for the Internationalist Communist Left", and why someone who claims to belong to the Communist Left should write it. As far as one can judge from this, Lafif Lakhdar was probably a man full of good intentions and not without a certain courage in standing up to the threats of Islamist fanatics, but whose action was entirely within the framework of bourgeois "democracy", and in defence of the illusions thanks to which the bourgeoisie maintains its domination. For anyone who had anything to do with the Communist Left, it would be out of the question to call on the UN (that "den of thieves" to use Lenin’s expression about the League of Nations) "to set up an international tribunal to judge terrorists". Should we react to terrorist attacks by demanding that the bourgeois state strengthen its police and judicial arsenal?16 Indeed, amongst Lafif Lakhdar’s achievements, there is one that Doctor Bourrinet does not mention (did he forget, or did he hide it?): an open letter dated 16th November 2008 to the new President of the United States, Barrack Obama, suggesting that he "change the world in 100 days by concluding a reconciliation between Jews and Arabs".17 In the letter, we find the following passages:

"Solving this conflict, with its explosive mixture of religion and politics, would be an agreeable surprise from you to the peoples of the region and the world. It would have undoubtedly a positive psychological impact on all the other crises, including the world financial crisis.

How can this be achieved? (…)

Send an American peace delegation headed by President Clinton and the outgoing Israeli President Ehud Olmert,18 and made up of Prince Talal Ben-Abdul Al-Aziz, the symbolic representative of the Arab peace initiative, and of Walid Khalid and Shibli Talham as representatives of the Palestinian people.

And what is the solution?

First of all, the application of Mr Clinton’s parameters which give the Jews what they have been lacking since the destruction of the Temple in 586BCE, and to the Palestinians what they have never had in their history: an independent state. Then, the application of Ehud Olmert’s ‘advice’ to his successor, which would accord the Palestinians the major part of their demands...".

And the letter concludes:

"President Barack Obama, it is said that you have little experience; by solving, in your administration’s first hundred days, a century-old conflict which has provoked five bloody wars and two intifadas, you would demonstrate to the world that you are a competent and responsible leader, and make a gift to the 80% of the world population who prayed for your success and so celebrated your victory". Could the Communist Left do no better than that?

Doctor Bourrinet’s biographical sketch of Lafif Lakhdar is published on the site Controverses under the heading "Internationalists". But what exactly is an internationalist? Someone who not only denounces chauvinism and military barbarism, but who defends to the utmost the only perspective that can put an end to them: the overthrow of the capitalist system by the world proletarian revolution. And this necessarily involves the denunciation of all pacifist and democratic illusions, and all the bourgeoisie’s political forces that spread them, however "democratic", "enlightened" or well-intentioned they may be. Whoever has not understood this stands not on proletarian ground, but on that of the bourgeoisie or the petty bourgeoisie. Our eminent Doctor (just like the equally eminent publishers of Controverses) clearly does not know the difference between a democratic humanist bourgeois and an internationalist, in other words a revolutionary. And this is because Doctor Bourrinet’s viewpoint is not that of the working class but of the petty bourgeoisie. This is clear enough in our account of the Doctor’s behaviour since he left the ICC, but his sketch of Lafif Lakhdar confirms it in as striking a manner as you could wish.

In fact, Doctor Bourrinet’s frantic search for official social recognition, his use of bourgeois institutions, and the state, to defend his "copyright" and his "intellectual property", his pettiness, his bad faith, his lies, his cowardice, and to cap it all, his hatred for the organisation and the militants thanks to whom he was able to write his two books, all the Doctor’s contemptible behaviour since 1992, are not merely expressions of his personality. They are also, and much more, the expression of his belonging to the social category which most concentrates all these moral defects: the petty bourgeoisie.

As we shall now see, the conference where Doctor Bourrinet figured as speaker amply confirms everything we have said about his person.

A significant conference

Doctor Bourrinet began with a long and soporific introduction. But the lethargy that crept over the audience (including the chair) was not merely because the Doctor has all the charisma of an oyster. More fundamentally, it was the fruit of a speech without soul or fighting spirit, at the end of which the chair could conclude that "the past is past" and that "questions today are posed differently".

There followed logically a whole series of "new" questions from the audience, such as "the situation in the prisons" (very new!) and of "precarious labour", etc. In short, the sole effect of Doctor Bourrinet’s discourse was to present the tradition of the Communist Left as something without interest for the present or the future, something from a vanished past to be read about in books fit only to gather dust on the shelf, at the disposal of university researchers.

In other words, Doctor Bourrinet’s presentation confirmed what all his behaviour up to then had already revealed: that henceforth, for our good Doctor, the history of the Communist Left has become a mere academic discipline and has nothing to do with the words of the militant Philippe Bourrinet, when as Chardin he wrote that it was: "(...) first and foremost a weapon in its present and future struggles, because of the lessons from the past that it contains" (International Review no.58, ibid).

But there’s more to come! Doctor Bourrinet made the most of the soporific effect of his presentation to slip in, as is his wont, a few historical falsifications – in perfect conformity with his tendency to "rearrange" history to suit himself.

He thus described the different Communist Lefts (of Italy, Holland, and Germany) as if they were completely isolated from each other, as if they had no interaction with each other. Nothing could be farther from the truth! It is true that in 1926, the Italian Left refused a proposal from Karl Korsch (then member of a group in Germany around the review Kommunistische Politik) for a common declaration by all the Left currents of the day (cf letter from Bordiga to Korsch of 28th October 192619). But the Left Fraction of the Italian Communist Party, which published Prometeo in Italian from 1929, and then Bilan in French from 1933, not only had the firm intention to confront its positions with those of the other left currents, above all with those of Trotsky’s Left Opposition and of the Dutch-German Left, it also adopted several positions of the latter current. For example, the analysis of national liberation struggles worked out by Rosa Luxemburg within the German and Polish Social-Democracy, then taken up by the German Left, was integrated into Bilan’s positions at the end of the 1930s.

Better still, this "expert" of the Communist Left even managed to ignore completely the very existence of the French Communist Left (Gauche Communiste de France, GCF). Just as, in Stalin’s day, people disappeared from photographs at each rewriting of official history, so our good Doctor somehow "forgot" all about this group, created at the end of World War II, in 1944. And with good reason: the distinguishing feature of the GCF (which published Internationalisme) was precisely its profound synthesis of the Lefts of different countries, in continuity with the work of Bilan. By drawing its inspiration from Bilan’s theoretical advances, and still more from its vision of a living, non-dogmatic marxism, open to every expression of the proletariat internationally, the GCF prevented this little group from falling into oblivion, and made it on the contrary a bridge between the best proletarian traditions of the past, and the future of the proletarian struggle. In other words, when Doctor Bourrinet wipes the GCF from the whiteboard of history he also, in a sense, wipes out Bilan, he breaks the historic continuity between revolutionary groups, and he breaks the transmission of this precious experience of our illustrious predecessors. In a word, he disarms the proletariat before its class enemy.

All this is perfectly deliberate on Doctor Bourrinet’s part. He knows perfectly well the GCF’s existence and its place in history. This is not the fruit of an unfortunate forgetfulness, or of ignorance; it is a deliberate effort to hide a truth which he would prefer to ignore: that the GCF made a contribution of prime importance to the thought of the Communist Left.

Why so? The answer is simple. Purely out of hatred for the ICC, the only organisation which explicitly claims a descent from the GCF, and out of hatred for the militant who played a key role in the formation of the ICC and was the main thinker behind the GCF: Marc Chirik.

Doctor Bourrinet’s hatred, which we have already seen at work in his various writings, was laid out for all to see at this public conference.

When the ICC’s delegation tried to call out the good Doctor for his falsifications and his "intellectual property", he became perfectly hysterical (as everyone could see): "you are terrorists and cheats", he cried, "you have forced many militants to resign from the ICC by stifling them" – in other words, he repeated all the slanders of "Marc Chirik’s political adversaries" which he has reported so "objectively" in the biographical sketch published on his web site.

Up to now, our Doctor has spread his venom from the shelter of official bodies, "doctored" biographical sketches, and "statements" on the Internet. This time, for once, he has dared do so in public, before four militants of the ICC. Such a change in attitude calls for an explanation.

As we have seen, Doctor Bourrinet is the prototypical petty bourgeois: cowardly, dishonest, and little inclined to spit his bile in the light of day, except... when the wind of rumour swells the cries of hatred against the ICC. Then he gets drunk on "courage" and is ready to take his part in the vilest of slander and the lowest of threats against our organisation. Through the centuries, calls to pogrom have always been thus: each participant makes his own wretched contribution according to his own motives, all different but all equally shabby and full of hate. Almost every time, this kind of barbaric dynamic is started by some kind of provocateur – whether a professional or an amateur is really immaterial. It is precisely into this that our unspeakable Doctor has plunged, hook line and sinker. After reading the anti-ICC prose of the IGCL,20 that seedy bunch of police-like back-room plotters with its provocateur Juan, the good Doctor has perked up no end and is ready to answer the call to villainy and hatred.

On 28th April 2014, the IGCL21 published an article as bad as anything by a professional provocateur. This slanderous text was titled "A new (and final?) crisis in the ICC!",22 and announced with ironic delight the ICC’s disappearance... which turned out to be "thoroughly exaggerated".23 But however unfounded, the mere idea that the ICC is weakened, almost at death’s door, has galvanised all those who are obsessed with the hope of seeing us dead and buried. And it is in this "courageous" crowd that we find the Doctor Bourrinet, all hot and flustered at the idea that he too can now howl with the wolves against the ICC. But even the encouragement of the provocateurs of the IGCL was not enough to give him pluck; he needed the comforting company of an acolyte alongside him, small in brain but big in brawn, and above all with the mentality of the hoodlum ready for any underhand villainy against the ICC: none other than Pédoncule,24 always ready to reassure and motivate our Doctor should his courage fail him during the conference. This individual has an edifying, and violent, pedigree: physical aggression against one of our women comrades, aggression against another comrade threatened with the switch-blade he always carries on him, and threats to "slit the throat" of yet another.25

The association of the Doctor and the hooligan (which could have been made into a French movie with Jean-Louis Trintignant and Depardieu in the title roles) may seem paradoxical, but should come as no surprise. The alliance between the intellectual petty bourgeoisie and the lumpenproletariat is not new, and in general it comes when they confront a common enemy: the revolutionary proletariat. In 1871, the majority of French writers (with the noteworthy exceptions of Arthur Rimbaud, Jules Vallès, and Victor Hugo) lined up with the scum of Paris to cheer on the Versaillais who slaughtered the Commune: the former with the pen, the latter more concretely through grassing and assassination.26 In 1919, the "honorable" leaders of German Social-Democracy used the lumpenproletariat grouped in the Frei Korps (the predecessors of the Nazis) to assassinate thousands of workers, at the same time as they murdered Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, the German revolution’s leading lights. Today, the petty bourgeois Bourrinet, Doctor of the University of Paris 1 – Sorbonne, teams up with Pédoncule the Ripper: what could be more normal? Both share the same obsessive hatred of the ICC; both want to see the disappearance of the ICC, in other words of the main organisation defending internationally the positions of the Communist Left.

As far as we are concerned, we intend to continue distributing the two books on the Italian Left and on the Dutch-German Left, whether Doctor Bourrinet likes it or not. And we urge our readers to read these books, written by Philippe Bourrinet when he was a militant of the ICC. They have lost none of their value just because, since then, the militant has become a Doctor and betrayed the cause to which he had been committed in his youth. Nor we will we give up denouncing the Doctor’s infamy, his lies, his slanders, and his contemptible efforts to call the institutions of the bourgeois state to his aid to threaten our militants and satisfy his hatred. He need not, however, worry that we will send a commando to "slit his throat" – we will leave that kind of thing to his bodyguard, Pédoncule the Ripper.

The history of the workers’ movement is littered with militants who once defended revolutionary proletarian positions, only to change camp and capitulate to bourgeois ideology to put themselves at the service of the ruling class. We all know what happened to Mussolini, who was a leader of the Italian Socialist Party’s left wing prior to World War I. Plekhanov, who introduced marxism to Russia and was one of the foremost figures in the struggle against Bernstein’s revisionism at the end of the 19th century, turned into a dyed-in-the-wool social chauvinist in 1914. Kautsky, the 2nd International’s "pope of marxism" and Rosa Luxemburg’s comrade-in-arms up to 1906, in 1914 put his pen to serve, de facto, the imperialist war, and condemned the 1917 revolution in Russia, all the while proclaiming formally his attachment to marxism, right up to his death in 1938.

Today, Doctor Bourrinet continues to proclaim his formal attachment to the Communist Left and its positions. But this is a swindle. The Communist Left is not just a matter of political positions. It also means loyalty to principles, refusal to compromise, a will to struggle for the revolution, an immense courage – all qualities of which Doctor Bourrinet is utterly bereft. Read today The Italian Communist Left, and The Dutch-German Communist Left, not as Doctor Bourrinet’s "intellectual property", but in the spirit of Philippe Bourrinet a quarter-century ago: "It's only from a militant standpoint, the standpoint of those who are committed to the workers' struggle for emancipation, that the history of the workers' movement can be approached".

International Communist Current, 15/01/2015

1The Smolny collective is a publisher specialising in the publication of books on the workers’ movement, in particular of the Communist Left. See our article in French "Les éditions Smolny participent à la récupération démocratique de Rosa Luxemburg [24]"

2"M. Proudhon has the misfortune of being peculiarly misunderstood in Europe. In France, he has the right to be a bad economist, because he is reputed to be a good German philosopher. In Germany, he has the right to be a bad philosopher, because he is reputed to be one of the ablest French economists. Being both German and economist at the same time, we desire to protest against this double error." Marx, Foreword to Poverty of Philosophy, 1847

3See our articles published in International Review [25] nos.65-66 [25]

4This material support included the payment of much of the cost of his documentary research, including the purchase of large quantities of micro-films from the Amsterdam International Institute for Social Research.

5The Société des Gens des Lettres is a French organism dating from the early 19th century, and devoted in particular to the judicial protection of copyright on behalf of its author members. Copies of the documents in question are attached to this article.

6This appeared in the English edition, The Dutch and German Communist Left, published in 2001.

7We will henceforth accord the Doctor his official title. This cannot but satisfy his intense desire for social recognition.

8And, we would add, a hypocrite. But that is the rule rather than the exception.

9The price list can be found at left-dis.nl/f/livre.htm [26]. Should the link disappear – one never knows! – we have of course kept a screen print as the site appeared on 15th January 2015.