Submitted by ICConline on

Exhibition ‘Bauhaus: Art as Life’ at the Barbican, London. Till August 12th.

The German Bauhaus 1919-1933, the world's most famous art school, was planned as a model of socialistic design and production. Bauhaus, literally translated into English, means ‘house of construction’.

Let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen without the class-distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsmen and artist! Let us together desire, conceive and create the new building of the future, which will combine everything - architecture and sculpture and painting - in a single form which will one day rise towards the heavens from the hands of a million workers as the crystalline symbol of a new and coming faith.

Bauhaus manifesto, April 1919.

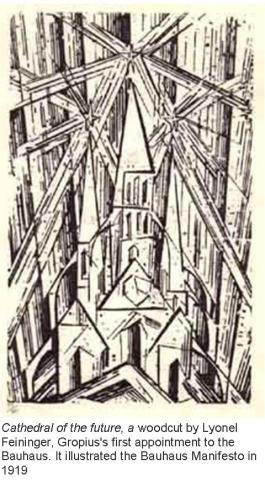

The architect Walter Gropius, former chairman of the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Art Soviet), wrote this rather romantic manifesto as founder of the new school. He distilled its aims more prosaically a few years later in the slogan ‘Art and technology, a new unity’.

The intention was to breakdown the distinction between:

high and low art (the Bauhaus incorporated the old fine art academy and the school for crafts in Weimar)

luxury art for the privileged and poorly made junk for the masses

industrial and handicrafts production

Artistic creation was to become an integral part of social life rather than a privileged niche within it. he creative process, previously surrounded by mystery, was to be clarified. Printing, pottery, textiles, metal work, furniture, theatre, were all to be integrated within a new modern architecture of light and space. Festivals, plays, parties, play were deliberately fostered to link the artistic community together and help put student and teacher on an equal footing. Hence the aptness of the title of the Barbican exhibition 'Art as Life'. And the title Lyonel Feininger gave to a woodcut illustrating the first Bauhaus manifesto: 'The cathedral of socialism'.

Despite its short life the Bauhaus has had an immense impact that is felt to this day. For example:

modernist architecture, known as the international style, of which the Bauhaus was a progenitor, has left an indelible imprint on building design. Even architectural trends that have reacted against it, like post-modernism, show by their very name that the international style remains a reference point

graphic design (advertising, magazine, newspaper and web design) would be impossible today without the Bauhaus pioneers

art education today retains the main innovation of the Bauhaus curriculum: a foundation course of basic principles and investigation, to be followed by several years specialisation in a particular field

Why was it so influential?

The October Revolution in Russia in 1917 and the revolutionary wave it inspired throughout Europe in the following years, especially in Germany, seemed, after the mass destruction of the First World War, to offer a new way of living. In the world of art the Bauhaus exemplified this spirit of modernity that today, walking around the exhibition, still inspires. In a society that seems to conspire against man, the Bauhaus held out the hope that modern industry could be re-fashioned for his benefit.

The Bauhaus was part of a wider international movement that attempted to break the stranglehold of bourgeois philistinism on art. Trends like Dada and Expressionism in Germany, De Stijl in Holland, Le Corbusier’s L’Esprit Nouveau in France, all shared similar goals. The Bauhaus was staffed by some of the best known international talents of the time: Walter Gropius himself, and later the architect Mies Van der Rohe, and painters like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky.

Indeed, in the same period, a Constructivist art school, the Vkhutemas (Higher Art and Technical Studios), with similar principles, but with far fewer resources, was founded in Russia, with the belief that a new proletarian artistic culture could be created on the ashes of the bourgeois regime. Kandinsky, who had helped formulate the curriculum of the Vkhutemas, moved to the Bauhaus in 1921.

Architecture and design were to be brought into harmony with mass industrial production. Hitherto these disciplines had lagged far behind the progress of technology and were still trying to imitate outmoded forms that were appropriate to pre-industrial methods of production, a trend heavily influenced by the conservatism of the bourgeoisie. According to the Bauhaus new forms had to be developed to express the possibilities of new technology at the service of the masses.

The Bauhaus’ radical espousal of modern materials and techniques (such as buildings made of steel and glass; furniture made from metal tubing); their principles of 'less is more', ‘truth to materials’ (elimination of decorative imitation and embellishment) and 'form follows function' (to take a small example: a chess set displayed in the exhibition was designed according to the moves of the pieces rather than composed of traditional figures!), created a new aesthetic sense and developed the appropriate skills to satisfy them.

Ironically in Russia the new materials were so scarce that wood was often used by constructivist architects to imitate the appearance of steel!

But could the Bauhaus help transform artistic production in a socialist direction?

Capitalism, in certain periods, has shown a capacity for tolerating educational experiments like the Bauhaus. In the early twenties, in the midst of working class revolt, and the threat of revolution, the Social Democratic Party, the main support of the Weimar Republic, had a strong interest in presenting the latter as a socialist alternative to the danger of a German October. With the reflux of the proletarian movement however the Bauhaus found funding increasingly difficult to obtain and in 1926 it was forced to move from Weimar to Dessau, and from there, in a last ditch move, to Berlin in 1932 where it was finally forced to close by the newly elected Nazi Government in 1933. For the latter modern art itself was ‘cultural Bolshevism’. The National Socialists had no intention of spending ‘German taxes’ on the upkeep of an avantgarde institution that included foreigners and Jews.

In Russia, the Bolsheviks, through the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment, founded the Vkhutemas in 1920. Anatoly Lunacharsky, the commissar, favoured the artistic avantgarde. Nevertheless Lenin and Trotsky didn't subscribe to the idea of the former Bolshevik Alexandr Bogdanov that it was possible to create a new proletarian culture from scratch within the isolated soviet bastion. The political power and the relations of production of the bourgeoisie had first to be crushed on a world scale before an extended process of developing a new classless culture could begin in earnest. Within this perspective the working class would have to absorb the achievements of previous cultures rather than simply recreating anew.

The Vkhutemas were closed in 1930 as the Stalinist counter-revolution was tightening its grip on cultural life under the doctrine of socialist realism.

In the end, whatever advances are made within capitalism in the field of education, the ruling class is obliged to subordinate them to its imperialist, political and economic objectives.

The Bauhaus ethos presupposed a system of social production orientated toward consumption and the satisfaction of human needs. But capitalism, while it must satisfy human needs in order to sell goods, nevertheless subordinates this aim for a more pressing one: profit. And if this aim can’t be met, due to the lack of solvent buyers for example, neither can human need.

Capitalist production, in its quest for profit, tries to reduce the consumption of the masses as much as possible by keeping wages to a minimum and by cheapening the production of consumer goods.

For this reason it has proved impossible, despite the great impact of the Bauhaus style, to bridge the gap between quality production for a small luxury market, and low-cost, badly made substitutes for the mass of the population.

Moreover, in the capitalist production process, the quest for profit demands a strict hierarchical division of labour and the unquestioning obedience of the worker, even in the ‘creative industries’. Instead of elevating the craftsman to the status of an artist, as the Bauhaus wanted, capitalism tends to demean him still further to the level of a machine minder – when it is not making him unemployed!

In 2005, according to the United Nations, about 100 million people were homeless in the world. 1 billion people were living in shanty towns. No doubt these numbers have increased since then. The beautiful dream of the Bauhaus appears to have been completely dashed.

But the productive forces of society, which include those of artistic culture, will continue to rebel against the grip of the capitalist relations of production. They will continue to point toward a new society and inspire us.

In this sense it is not the Bauhaus that has failed – it will remain an historical landmark of cultural progress – but capitalism itself.

Como 24/7/12

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace