Submitted by ICConline on

5: The War in Spain - No Betrayal!

The period between 1936 and 1939 was marked by the definitive consolidation of military preparations, and by the extension of conflicts in Asia and Europe. Even more than the Sino-Japanese conflict, the war in Spain was to serve as a testing ground for the latest weapons - the weapons that were to be used in the World War 2.

In contrast to the previous period, the Italian Fraction was to underestimate the danger. A part of the organisation even came to believe that the events in Spain marked the beginning of the world revolution. The majority, while opposing this position, thought that each local conflict was bringing closer the world-wide confrontation between bourgeoisie and proletariat.

The civil war in Spain was thus to play a decisive role in the life of the ‘Bordigist’ Fraction, on the one hand threatening its existence, on the other hand consolidating it.

The Italian Left had attentively followed the evolution of the Spanish situation since 1931. The political convulsions which had led to the Republic’s creation had given rise to a lively polemic between the Fraction and Trotsky, who implicitly defended the new regime as ‘anti-feudal’. Prometeo had been the only publication in the revolutionary milieu to denounce the Republic as reactionary and anti-working class. This analysis was one of the main reasons for the split between the ‘Trotskyist’ current and the ‘Bordigists’.

Up to 1936, Prometeo and Bilan saw no reason to modify their analysis. On the contrary, they pointed out that, even more than the defunct monarchy, the Republic was leading a determined offensive against the Spanish workers, in order to destroy any possibility of a class reaction: “... October 1934 marks the frontal battle to obliterate all the forces and organisations of the Spanish proletariat” (Bilan no. 12, October 1934, ‘L’Ecrasement du proletariat espagnol’). The Italian Fraction rejected any choice other than that between bourgeoisie and proletariat:

“Left-right, Republic monarchy, supporting the left and the Republic against the right in view of the proletarian revolution, these are the choices and positions defended by the different currents acting within the working class. But the real choice is elsewhere and consists in the opposition between capitalism and the proletariat, the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie in order to crush the proletariat, or the dictatorship of the proletariat in order to erect a bastion of the world revolution for the suppression of states and classes.” (Bilan no. 12, op cit).

Faced with the Popular Front, Bilan, as in France, denounced “the democratic forces of the bourgeois left” which “have shown that they are not a step leading to the victory of the proletarian revolution, but the last rampart of the counter-revolution” (Bilan no. 33, July-August 1936, ‘En Espagne, bourgeoisie contre prolétariat’). Indeed, “the accentuation of the government’s leftward course was the signal for an even stronger repression against the workers”, (ibid)

For Bilan, the Spanish situation could in no way be compared to the Russian. In a country “in which capitalism has been formed for centuries”, there was no possibility of a bourgeois revolution. The struggle was not between ‘feudalism’ and a ‘progressive bourgeoisie’, but between capitalism - however backward - and socialism.

In July 1936, Franco made his ‘pronunciamiento’. The putsch provoked the uprising of the workers of Barcelona and Madrid. Militias were formed, without the Republican government being overturned. Was this a revolution?

The majority of the Fraction, confronted with the dramatic events in Spain

Very quickly a discussion opened up in the Italian Left, between those who were talking about a revolution, and those who saw the July uprising as “a bloody social tumult, incapable of reaching the level of an insurrectionary uprising”. At the beginning, the majority current which defended the second position was a substantial minority. In the Brussels section, only Vercesi and Gatto Mammone were opposed to the militants who wanted to go to Spain to fight in the militias of the POUM and the CNT, “to defend the Spanish revolution”. The same thing happened in the Paris section, where the tendency which rallied to the analysis of Vercesi and Mammone was in a minority at first. But within a few months, a majority developed against sending militants to Spain to fight in the military fronts and for “the transformation of the imperialist war into a civil war”.

What were the arguments of the majority?

• the absence of a class party. According to the conception of the Italian Left, only the party could give life and consciousness to the proletariat. While it did not exclude the upsurge of proletarian movements without the party, the existence of the latter expressed the ripening of a revolutionary situation. Although sometimes and especially in the case of Vercesi, it supported the idea that without a powerful party, like the Bolshevik party, the working class no longer existed, this was far from being its position in 1936. The Fraction distinguished between the proletariat taken sociologically, which could be derailed from the revolutionary path, and the proletariat as a revolutionary class moving towards the seizure of power.

If the party did not exist it was “because the situation had not permitted its formation”. For the Fraction, without a revolutionary situation there was no revolutionary party, and inversely without a revolutionary party the revolutionary situation was absent. Neither the POUM nor the CNT, which were participating in the Popular Front through the Generalidad in Catalonia and were diverting the proletariat away from a frontal attack on the Republican state, could be described as revolutionary.

“The first phase of poor material armament but intense political armament was succeeded by one marked by the growth of technical instruments at the disposal of the workers and the progressive transportation of the latter from their original class basis to the opposite basis: that of the capitalist class.”

In place of class frontiers, the only ones which could have disintegrated Franco’s regiments and restored confidence to the peasants terrorised by the right, other frontiers arose, specifically capitalist ones, and the Union Sacrée was made a reality through the imperialist carnage, region against region, town against town, within Spain, and by extension, state against state in the two blocs, democratic and fascist.

It was no longer a matter of two classes confronting each other, but two factions of the Spanish bourgeoisie, supported by the imperialist blocs. “Armed struggle on the imperialist level” had become “a tomb for the proletariat”. In effect, “in the present period of the decline of capitalism, no war can have a progressive value except the civil war for the communist revolution”.

• the strength of the Spanish bourgeoisie. Though economically weak the Spanish bourgeoisie had not been deprived of its repressive apparatus. While Franco led the military attack, the Republican bourgeoisie manoeuvred in the most consummate manner in order to disarm the workers ideologically “by the judicial legalisation of the arming of the workers” and the incorporation of the militias into the state. But it was above all the POUM and the CNT which played the decisive role in enrolling the workers for the front. The two organisations ordered an end to the general strike without having played any part in unleashing it. The strength of the bourgeoisie was expressed not so much by Franco, but by the existence an extreme left able to demobilise the Spanish proletariat.

“When the capitalist attack was unleashed by Franco's uprising, neither the POUM nor the CNT dreamed of calling the workers into the streets...

“Through its slogan of a return to work, the POUM clearly expressed the turning point in the situation and the bourgeoisie's manoeuvre of putting an end to the general strike, then by issuing decrees to avoid a workers' reaction and finally, by pushing the workers out of the towns towards the siege of Zaragossa. (Bilan no. 36, Oct-Nov 1936, ‘La Leçon des Evénements d’Espagne’).

Certainly, as Bilan recognised, at the end of July, the regular army had been “practically dissolved”, but thanks to these two parties and the Stalinist PSUC “it was gradually reconstituted with the columns of militiamen whose general staff remained clearly bourgeois...”

Finally, Bilan added, the power of the Republican state was definitely consolidated on 2 August, when the Catalonia Generalidad decided “to call several classes to arms”. The civil war between bourgeoisie and proletariat became a plain war between rival bourgeois factions, under the leadership of the coalition Republican government supported by the Poumists and the anarchists.

• The trap of ‘collecivisation’ and violence. Many militants saw in the collectivisation of factories and land the real expression of the ‘Spanish revolution’. But in any genuine proletarian revolution, politics comes before economics. It is only under the dictatorship of the proletariat, after the capitalist state has been smashed, that there can be economic measures in the interest of the proletariat. For Bilan:

“The way to develop the class struggle does not reside in successively enlarging material conquests when the enemy's instrument of domination remains intact, but through the opposite road of unleashing proletarian movements. The socialisation of an enterprise when the state apparatus remains standing is a link in the chain tying the proletariat to its enemy both on the internal front and on the imperialist front of the antagonism between fascism and antifascism, whereas the outbreak of a strike for the slightest class demand (and that even in a ‘socialised’ industry) is a link that can lead towards the defence and the victory of the Spanish and international proletariat.” (Bilan no. 34, August-September 1936, ‘Au front impérialiste du massacre des ouvriers espagnoles il faut opposer le front de classe du prolétariat international’).

Violence against the capitalists, the priests, the big landowners was no more revolutionary. Proletarian violence can only have class content if it attacks the state system. Socialism is the destruction of capitalism as a social organisation, and not of its symbols: “The destruction of capitalism is not the physical and even violent destruction of the persons who incarnate the regime, but of the regime itself” (Bilan no. 38, January 1937, ‘Guerre impérialiste ou guerre civile?’).

• The Union Sacrée and the banning of strikes. It was antifascism and the military struggle which had created a situation of Union Sacrée. As in 1914, the ‘external danger’ had served as a pretext for depriving the proletariat of its only real weapon: the general strike. On the one hand the PSUC, in Mundo Obrero of 3 August, had proclaimed “no strikes in democratic Spain”. On the other hand, “in October the CNT issued its union directives in which it forbade any kind of struggle for immediate demands and made the increase of production the most sacred duty of the worker” (Bilan no. 36, Oct-Nov 1936). Finally, to complete the Union Sacrée and ‘social solidarity’, the factory committees and workplace control committees “were transformed into organs that had to run production and were thus deformed in their class significance” (ibid).

• the isolation of the Spanish proletariat. It was the international victory of the counter-revolution which explained this defeat and the massacre of the Spanish workers at the front:

“Without the annihilation of the most advanced proletariats, we would never have had such a tragedy... In Spain the conditions did not exist for the battles of the Iberian proletariat to be the signal for a world-wide revival of the class, even though the economic, social and political contrasts were more profound here than in other countries.” (ibid).

Bilan added that it was therefore impossible to reverse the present situation “once the infernal machine was in motion” (no. 38, Dec 1936); that this desperate situation “was simply the reflection of a balance of forces between classes unfavourable to the proletariat” (Bilan no. 36, Oct 1936, ‘L’isolement de notre fraction devant les Evénements d’Espagne’).

These in brief were the arguments of the majority of the Fraction. It was conscious of going against the tide at a time when in all countries people were joining up with the ‘international brigades’ or volunteer militias. Against the participation in the war in Spain, Bilan was for desertion from the army and fraternisation between the soldiers of both camps, as in 1917. The Fraction “vehemently calls on the workers of all countries” not to “sacrifice their lives in order to accredit the massacre of the workers in Spain”; to refuse “to go off with the international columns in Spain” and to break the tragic isolation of the Spanish proletariat by engaging in “their class struggle against their own bourgeoisie” (Bilan no. 36, Oct 1936, ‘La Leçon des Evénements d’Espagne’). This position which was clearly in continuity with the ‘revolutionary defeatism’ of the Bolsheviks, was concisely condensed in this appeal to the workers of all countries:

Against volunteering, desertion.

Against the struggle against the ‘Moors’ and the fascists, fraternisation.

Against the Union Sacrée, the development of class struggle on both fronts. Against the demand to raise the blockade of arms for Spain, struggles for class demands in all countries and opposition to all transportation of arms...

Against the call for class collaboration, the call for the class struggle and proletarian internationalism (Bilan no. 38, Dec 1936-Jan 1937. ‘Guerre impérialiste ou guerre civile?’).

The Italian Left insisted that its position did not mean opening the way to the defeat of the workers in the face of fascism; on the contrary, by attacking the Republican state machine, the proletariat of Catalonia, Castille, the Asturias and Valencia would have facilitated the insurrection of the workers on the other side of the military frontier and the paralysis of the Francoist army. In fact, this attack was the only way of “disintegrating the regiments of the right”, of “smashing the plans of Spanish and international capitalism” (no. 34, op cit.).

The majority was ready to defend its principles to the last, convinced that “the cruel development of events has not only left the whole of (its) political positions intact, but has most tragically confirmed them”. Whatever happened it would remain “immovably anchored in the class foundations of the proletarian masses” (Bilan no. 36, Oct-Nov 1936 ‘La consigne de l’heure: ne pas trahir’).

Towards a split: arguments and activity of the minority in Spain

The minority, which had appeared in July 1936, was in total disagreement with the majority analysis. All of those who were regrouped around it in August-September left for Barcelona, where they formed a section of 26 members. Among them were founding members of the Fraction, like Candiani (E.Russo), Mario di Leone, Bruno Zecchini, Renato Pace, and Piero Corradi. Most of them came from the Parisian federation. This was a brutal haemorrhage for a section of 40-50 militants. In other sections and federations, the minority was tiny.

The minority’s analysis was based on a serious overestimation of the Spanish situation, springing from a sentimental reaction rather than a real and mature reflection. For the minority, the Republican state had virtually disappeared and power was in the hand of ‘workers’ organisations’, about whose nature it was not very precise: “The real government is in the hands of workers’ organisations; the other, the legal government is an empty shell, a simulacrum, a prisoner of the situation”. (Bilan no. 35 Sept-Oct 1936 ‘La Révolution Espagnole’ by Tito). In fact, the minority was above all fascinated by the acts of violence and expropriation: “the burning of churches; confiscation of goods; occupation of houses and property; requisitioning of newspapers; summary condemnations and executions, these are the formidable, ardent, plebian expressions of this profound overturning of class relations which the bourgeois government cannot prevent” (ibid).

In this text we can see the minority contradicting itself. At one and the same time it proclaimed the disappearance and the existence of a Republican government. Touched by the Spanish drama, it was more disposed to action than to a real study of the balance of forces which was little by little being revealed in its true light.

Its position was close to that of the POUM and the French Trotskyists. It thought that the fundamental duty of any revolutionary was first to fight on the military front against fascism, and then to overturn the Republican government. The position of the majority seemed to it to be not only “a manifestation of insensitivity and dilettantism” but “incomprehensible and practically counter-revolutionary”. To make “no distinction between the two fronts” meant “facilitating the victory of Franco and the defeat of the proletariat” (Prometeo, 1/11/1936, ‘Critique révolutionnaire ou défaitisme?’, Minority of the Paris Federation).

This did not mean that it supported the Republican government. “No comrade of the minority has claimed that we have to support Azana or Caballero in Spain” (ibid). But wasn’t its “revolutionary criticism” implicitly a ‘critical support’? Against the majority, the minority argued that this government was historically equivalent to the Kerensky government in 1917 faced with Kornilov’s offensive. But it added that it was above all necessary to fight against “the brutal attack of the capitalist reaction” represented by the Spanish Kornilov [2].

It supported the military struggle in a somewhat embarrassed manner. No doubt, under the pressure of the majority, it did not exclude the possibility, “if the two rival imperialist blocs intervene in Spain -which would provoke a world conflagration”, that it would be necessary “to oppose both imperialisms”. In this case, “the war would be an imperialist war” which it would reject (ibid).

In fact, within Spain, the minority was unable to distinguish itself from the POUM and the CNT which had decreed a truce with the Caballero-Azana government. The Barcelona group, which published texts in La Batalla, the organ of the POUM, affirmed that the latter constituted a “vanguard” which had before it “a great task and an extreme responsibility” (motion of 23 August 1936, Bilan no. 36). For the majority, on the contrary “the POUM is a terrain on which the forces of the enemy are acting, and no revolutionary tendency can develop within it” (ibid).

Like the POUM and the CNT, the minority soon declared themselves to be against workers’ strikes for economic defence, which had to take second place to military tasks:

“How can you call for agitation in the factories, provoke strikes, when the fighters at the front need the factories to work in order to supply and support the struggle? Today in Catalonia, you cannot even put forward simple economic demands. We are in a revolutionary period. The class struggle is manifested in the armed struggle.” (Prometeo, op. cit.)

The two positions were irreconcilable and a split appeared inevitable. By going to Barcelona to join the militias, by organising itself outside the Italian Fraction, by forming an autonomous section, the minority was moving towards a break. It refused to pay dues and to distribute the Italian press. Soon, under the command of Candiani, it formed the Lenin column in the military front in Huesca.

There, at the beginning of September, three delegates of the majority - Mitchell (who was still in the Belgian LCI), Turriddu Candoli and Aldo Lecci met up with the minority for a totally fruitless discussion. The delegates from the majority found it equally impossible to hold a dialogue with Gorkin from the POUM leadership. Only a discussion with the anarchist teacher Camillo Bemeri, had any positive results [3].

The fact that the majority sent a delegation to Spain showed that it was not indifferent to the events. Despite its isolation and the certain risks it took in defending its positions (the delegates were nearly assassinated in Barcelona on coming out of the POUM’s offices), the majority was determined to carry the discussion to the end, without conceding an inch on its positions. It was aware that a “grave crisis” had opened up, “inevitably posing the problem of a split”, which, however, it hoped would be “ideological and not organisational” (Bilan no. 34, Aug-Sept 1936, ‘Communique of the executive commission’).

The Executive Commission of the Italian Fraction, even though it could have made play of the minority’s infringement of discipline, did not want to resort to measures of exclusion. Having a very high idea of organisation which “resides... in each of its militants” (Bilan no. 17, April 1935), it tried to preserve the organisation’s integrity, and if this proved impossible, to allow for a split to take place on the clearest possible basis. It decided “not to cut off the discussion so as to allow the organisation to benefit from the contribution of comrades who have not been able to intervene actively in the debate” and from “a more complete clarification of the fundamental divergences which have appeared” (Bilan no. 34. ibid). In order to do this, the EC opened the columns of an entre page of Prometeo to the minority in order that they could express their divergences. It was even prepared to pay for the publication of a paper by the minority until the Congress of the Fraction, which was due to be held at the beginning of 1937. As a precondition, the minority was to respect organisational discipline, and the majority refused to recognise the Barcelona Federation.

But the minority, while making use of the facilities for discussion, refused to accept these proposals. It formed itself into a ‘Coordinating Committee’ and sent out a communique which was a real ultimatum. It demanded recognition of its group; denied “any solidarity with or responsibility for the positions taken by the majority of the Fraction”; demanded, despite the EC’s veto, the right to “defend the Spanish Revolution with guns in hand, even on the military front”; considered that “the conditions for a split (were) already posed”; authorised “the comrades of the minority to combat the majority’s positions and not to distribute the press and any other document based on the official positions of the Fraction”. Finally the communique ‘demanded’ that this agenda be published in the next issue of Prometeo and Bilan. This was done in Bilan no. 35, Sept-Oct 1936.

In any other organisation such an attitude would have merited expulsion. The EC chose not to do so. It soon recognised the ‘coordinating committee’ and even the Barcelona Federation. It wanted at all cost to “avoid disciplinary measures and convince the comrades of the minority to coordinate themselves in order to form a current of the organisation orienting itself towards demonstrating that the other current had broken with the fundamental bases of the organisation and that it remained its real and loyal defender” (communique of the EC, 29/11/36). Certainly, the EC felt a split to be inevitable; it was not the militants it wanted to exclude, but the “political ideas” which “far from being able to engender real solidarity with the Spanish proletariat have accredited among the masses forces which are profoundly hostile to them and which capitalism is using for the extermination of the working class in Spain and all countries” (Bilan, ibid).

In November the split was consummated on both sides. The minority refused to participate at the Congress of the Fraction and to send its political literature to the EC so that it could acquaint itself with it. Proclaiming any discussion with the Fraction to be useless, it entered into contact with the antifascist organisation ‘Giustizia e Liberta’. This was one of the reasons why the Executive Commission excluded as “politically unworthy” the members of the ex-minority, whose activity was a “reflex of the Popular Front within the Fraction” (‘Communique of the EC’, op cit) [4].

When, at the beginning of 1937, the militias were militarised and formally integrated into the state under a central command, the members of the ex-minority left Spain. Soon afterwards they joined Union Communiste, of which they remained members until the war.

Just before May, the Italian Fraction’s delegate in Spain returned to France. Soon after that it became known that the workers of Barcelona had been massacred by the police, who were heavily infiltrated by the PSUC. The CNT intervened to ask the workers not to take up arms, and to go back to work, “in order not to obstruct the war effort”.

The Italian Fraction saw its whole analysis confirmed in these tragic events. It immediately issued a leaflet, in French and Italian, distributed to workers in France and Belgium: “Bullets, machine guns, prisons, this is how the Popular Front replies to the workers of Barcelona who have dared to resist the capitalist attack” (Bilan no. 41, May-June 1937). This leaflet-cum-manifesto noted that “the carnage in Barcelona is the foretaste of still more bloody repression against the workers in Spain”. It denounced the slogan of “arms for Spain” which had “resounded in the workers’ ears”: “these arms have been used to shoot their brothers in Barcelona”. It saluted Bemeri, assassinated by the Stalinist secret service, as one if its own. But all these deaths “belonged to the whole world proletariat”. In no way could they be “claimed by currents which on 19 July, had led the workers away from their class terrain and pushed them into the jaws of antifascism”.

All the deaths in Barcelona, finally, bore witness to the definitive passage of ‘centrism’ (ie the CPs) and of anarchism “to the other side of the barricade”, just like the opportunists of social democracy in 1914.

This manifesto was signed by the Italian Fraction and the new Belgian Fraction (see below) of the International Communist Left. The moment had come to “forge the first links of the international communist left”.

More than ever, the communist left found itself isolated from the groups with which it had, with ups and downs, been in contact. With different nuances, Union Communiste, the Ligue des Communistes Internationalistes, the Revolutionary Workers’ League and the Communist League of Struggle had adopted the same position as the minority in Bilan.

In the USA, during the events in Spain, the New York Federation had once again to confront Hugo Oehlers’ RWL which reproached the International Communist Left for putting forward “the slogan of revolutionary defeatism, which means putting the two belligerent groups on the same level, without making any distinction”. Like the Trotskyist groups, it saw Bilan’s intransigent refusal to support the war in Spain as an “ultra-leftist position” which “plays the game of the fascists, just as the reformists and centrists are playing the game of the Popular Front”.

The RWL’s attitude to the war in Spain was contradictory: while calling on the Spanish proletariat to join in the military fronts, it declared the necessity to “overturn the Popular Front government, which means the DEFEAT of the Popular Front government”, and this “before the decisive struggles against fascism have been won”. (‘Reply by the RWL to a letter from the New York Federation’, in Bilan no. 45, December 1937).

Only the Mattick group linked to the Dutch-German Left through the Groep van Internationale Communisten (GIC), and which had published International Council Correspondence since 1934, seemed to have the same position as Bilan in rejecting enrolment on the military front. But not with the same clarity, since it published a text by the GIC translated from Persdienst, whose position was identical to that of all the groups mentioned. In this text, which affirmed that any proletarian revolution “could only be victorious if it is international”, otherwise it would be “crushed by force of arms or deformed by imperialist interests”, the conclusion went against the premises:

“The Spanish workers cannot allow themselves to struggle effectively against the unions, because this would lead to a complete failure on the military fronts. They have no alternative: they must struggle against the fascists to save their lives, they have to accept any aid no matter where it comes from,” (in I.C.C. no. 5-6, June ‘37, ‘Anarchism and the Spanish Revolution’ by H. Wagner).

Up until World War 2, the Italian Left does not seem to have had any relationship with Mattick’s group. The direct consequence of events was to make all these groups fold in on themselves, to conserve their orientation faced with the flood of war. The profound divergences between these revolutionary groups resulted in mutual distrust and isolation. In all cases, Bilan’s profound coherence on the war in Spain contrasted with the hesitation and incoherence of the other groups, who remained half-way between Trotskyism and the Communist Left.

This oscillation was clearly reflected in both Union Communiste and the LCI in Belgium. UC had not sent militants to the militias. Only Emile Rosijansky, the former leader of the ‘Jewish Group’, had joined on his own initiative. It contented itself with giving moral support to the ‘workers’ militias’ and the two organisations which it saw as the avant-garde. It criticised them for their “major errors”, but it saw the POUM above all as “called upon to play an important role in the international regroupment of revolutionaries”, on the condition that it rejected the defence of the USSR and distanced itself from the London Bureau. In L’lntemationale, UC often played the part of adviser to the POUM, and rejoiced in the fact that its review was read by anarchist and Poumist youth.

Ideologically and organisationally, it remained close to Trotskyism, out of which it had emerged, even if it criticised Trotsky’s “opportunism”. At the end of 1936, it took part, with this current and certain syndicalists in the creation of a ‘committee for the Spanish Revolution’.

Its analysis of the situation in Spain was extremely contradictory. The same article could declare that “the revolution in progress” had dismantled the Republican state, whose “machine had burst into countless pieces under the pressure of the forces in struggle” and, in another paragraph, that “there remains much to demolish, because the democratic bourgeoisie is clinging to the last surviving fragments of bourgeois power”. Similarly, UC called for a “struggle to the death against the fascists” and the destruction of the power of the “antifascist bourgeoisie”. It did not however make it clear how this second form of struggle would be possible when the workers were mobilised on the military front.

The lack of logic could be seen with regard to the slogan of the CP and the French Trotskyists which called for “arms for Spain”. On the one hand, L’Internationale proclaimed that the “non-intervention” (by the Popular Front) was a blockade against the Spanish Revolution; on the other that “the struggle to give effective support to our comrades in Spain amounts in reality to the revolutionary struggle against our own bourgeoisie” (6). Later on, UC affirmed the “bankruptcy of anarchism in the face of the problem of the state” and said that “the Spanish Revolution is in retreat” while “imperialist war is threatening”. That is to say, that this organisation, unlike Bilan, reacted in the wake of events, without a general theoretical position on the Spanish question. This is why the Italian Left criticised it so strongly and located it, on the map of political geography, in the ‘swamp’.

We will not go into the LCI’s position on Spain. They merely repeated the conception of the minority in Bilan and of the UC. Just like the RWL, they denounced Bilan’s “counter- revolutionary positions”: “break-up of the military fronts, fraternisation with Franco’s troops, refusal to supply the Spanish government militias with arms”; negating “the opposition between fascism and democracy” (Bulletin, March 1937).

The attitude of the Italian Fraction in Brussels towards the LCI had from the beginning been one of a fraternal search for political discussion, and even collaboration, since as much as possible the two organisations published each other’s texts and contributions. Even on the question of Spain, the Italian Left, supported within the LCI by Mitchell’s minority, carried on a discussion that was patient and fraternal in tone. Vercesi, in an article in Bilan, summarised the divergences without acrimony or hostility:

“For comrade Hennaut, it is a question of going beyond the antifascist phase to arrive at the stage of socialism; for us it is a question of negating the programme of antifascism, for without this negation the struggle for socialism is impossible.” (Bilan no. 39, Jan-Febr 1937, ‘Nos divergences avec le camarade Hennaut’).

Other deep-seated disagreements existed on the questions of the party, the state and the Russian Revolution. On all these points, the LCI majority was close to the Dutch Left.

The birth of the Belgian Fraction (February 1937)

It was the question of Spain which put an end to the joint work between Bilan and Hennaut’s group. In February 1937, the LCI held its national conference in Brussels. Mitchell (Jehan) wrote, in the name of the minority, a resolution defending the position of the Italian Left on the Spanish events. The conference, which approved Hennaut’s resolution on Spain, decided to exclude all those who supported Jehan’s text and to break off political relations with the Italian Left. The split was complete.

The minority had not been looking for a split - it had been imposed on it. It wanted the separation to take place on the clearest possible basis.

In April that same year the first issue of the publication of the Belgian Fraction of the International Communist Left appeared: Communisme. This monthly review published 24 issues up until the war. It represented an expansion of the Italian Left’s presence in Belgium.

The Belgian Fraction’s ‘Declaration of Principles’ showed that it was not distinct from the Italian Left. Basing itself on the body of doctrine elaborated by Prometeo and Bilan, it presented the fundamental positions of the Italian Communist Left in the most synthetical manner.

The Belgian group was not large (a maximum of 10 militants). It had all the support of the Italian Fraction in Brussels, since it was in this town that the minority in the LCI had been formed. It was a group largely made up of young people but, like the Italian Left, it had the advantage of having emerged, via the LCI, out of the old movement as it had developed in the PCB (Belgian Communist Party). It was formed after being involved in internal and external discussion with the ‘Bordigist’ group since 1932, and had thus acquired a high degree of political and theoretical homogeneity. Like Vercesi in the Italian Fraction, Mitchell (from his real name Melis) had played a decisive role in the foundation of the Belgian Fraction. Holding an important post in an English bank, he helped to orient the Italian Left towards a deeper study of economic phenomena, and particularly the roots of the “decadence of capitalism”. Because of his personality and the rigour of his theoretical and political thinking, he was certainly one of the few who could counterbalance the crushing influence of Vercesi. His death at Buchenwald during the war was to weigh heavily on the development of the Italian and Belgian Communist Left.

Contacts with Mexico: Paul Kirchhoff and the Grupo de Trabajadores

Politically isolated, the International Communist Left only had a real existence in two countries. It was thus with great surprise that in June 1937, it received from far-away Mexico - where it had never had any contacts - a leaflet denouncing the ‘massacre in Barcelona’ in May. Signed by the Grupo de Trabajadores Marxistas de Mexico, it was in complete harmony with the positions of Bilan and Prometeo. It attacked the Cardenas government which had been the most ardent supporter of the Spanish Popular Front and had sent arms to the Republicans. This government aid, camouflaged under a “false workerism”, had contributed to the massacre of our “brothers in Spain”. It warned that “the defeat suffered by the workers in Spain must not be repeated in Mexico”. The Mexican workers thus had to fight for “an independent class party”, against the Popular Front and for the dictatorship of the proletariat. Only “the struggle against the demagogy of the government, alliance with the peasants and the struggle for the proletarian revolution in Mexico under the banner of a new communist party” would “guarantee our victory and be the best aid we can give to our brothers in Spain”.

Like the Italian and Belgian Lefts, it called on the workers of Spain to break with the Socialists, Stalinists, anarchists, all of whom were “in the service of the bourgeoisie” and to “turn the imperialist war into a civil war”, through the fraternisation of armies and the constitution of a “soviet Spain” [7].

Such a convergence of positions undoubtedly showed that the ‘Marxist Workers’ Group’ was well acquainted with the orientation of the Italian Left.

A few weeks later, the Italian and Belgian Left - but also Union Communiste - received a circular from this group about the campaign of slander waged against it by the Trotskyist group in Mexico, the Liga Comunista [8]. The militants of the MWG were denounced in IV Internacional as “agents of the GPU” and “agents of fascism”. In a country where the Mexican CP and the police did not hesitate to resort to assassination, this denunciation was to put these militants into the gravest danger - militants who undeniably defended the cause of the proletariat with the greatest firmness and energy, whatever one’s view of their political positions. The August issue of IV Internacional contained the most serious accusations:

“...the individuals cited, or rather the provocateur Kirchoff, called for not supporting the Spanish workers under the pretext that to demand more arms and munitions for the antifascist militias is to … support the bourgeoisie and imperialism. For these people, who cover themselves with an ultra-leftist mask, the sum total of Marxism consists ... in the abandonment of the trenches by the workers at the front. In this way the German and his instruments Garza and Daniel Ayala reveal themselves as agents of fascism, whether consciously or unconsciously - it matters little, given the consequences.”

Bilan and Communisme sent an open letter to the centre for the IVth International and to the Trotskyist PSR in Belgium, demanding clarification. This letter received no reply. It showed that this denunciation was at root political, and that the methods of Trotsky and his followers were curiously redolent of those of Stalinism. Bilan concluded that:

“… it has been clearly established that it was above all because these comrades have adopted an internationalist position analogous to the one proclaimed by marxists during the 1914-18 war ... that they have been denounced as provocateurs and agents of fascism.” (Bilan no. 44, Oct-Nov 1937).

In fact, the militants cited by the Trotskyist organisation were not all unknown figures. And for good reason! Garza and Daniel Ayala had come out of the Liga Comunista in Mexico. They had broken with it because of its support for the ‘progressive’ character of the nationalisations carried out by the Cardenas government, its support for the Spanish Republican government, and its attitude in the Sino-Japanese war in which it took the side of the Chinese government.

As for the ‘provocateur Kirchoff’ - who was known under the pseudonym Eiffel and whose real name was Paul Kirchoff - he was also not unknown to the revolutionary movement. The one whom the Liga Comunista called “the German”, the “agent of Hitler”, had since 1920 been a militant of the German Communist Left. A member of the KAPD since its foundation - and also of the ‘sister’ organisation of the KAPD, the AAU, in Berlin - he participated in the work of this current until 1931. An ethnologist by profession, he left Germany for the USA that year. From 1931 to 1934, he was a member of the IKD in exile, also of the Latin American Department of the International Left Opposition. In September 1934, he was one of the 4 members (out of 7) of the leadership of the IKD in exile who rejected the policy of entrism into social democracy and who described this policy as “complete ideological capitulation to the 2nd International”. Having broken with Trotsky, he was until 1937 [9] a member of the political bureau of Oehler’s Revolutionary Workers’ League. Expelled from the US, he had to take refuge in Mexico. In contact with the RWL, which he represented vis-à-vis the Trotskyist Liga Comunista, he defended the positions of the Italian Left as a minority within that group. On the events in Spain, he presented a motion proclaiming the failure of the RWL: “The events in Spain have put every organisation to the test; we have to admit that we have not passed this test. Having said this, our first duty is to study the origins of this failure”. The Eiffel motion, like that of the LCI minority, clearly implied a split:

“The war in Spain began as a civil war, but was rapidly transformed into an imperialist war. The whole strategy of the world and Spanish bourgeoisie has consisted in carrying out this transformation without changing appearances and letting the workers think they were still fighting for their class interests. Our organisation has kept up this illusion and supported the Spanish and world Bourgeoisie by saying: 'The working class in Spain must march with the Popular Front against Franco, but must prepare to turn its guns on Caballero tomorrow’.” (in L’Internationale no. 33,18/12/37, ‘La RWL et ses positions politiques’).

Having broken with the RWL, Eiffel and a small group of workers and former Trotskyist militants formed themselves into an independent political group. In September 1938 they published the first issue of Comunismo, which had two and possibly three issues before disappearing in the whirlpool of the world war.

If the MWG had been formed in Europe, it would probably have been linked organisationally with the International Communist Left. Geographical isolation condemned the small Mexican group to live by itself in the most total isolation, in a country dominated by the ideology of ‘anti-imperialism’ and the ‘workerist’ nationalism of Cardenas. In order to survive, Comunismo kept in written contact with the Italian and Belgian Fractions. It recognised that it was “the work of these two groups which had inspired its effort to create a communist nucleus in Mexico”. “Stimulated by this international support and by the letters sent us by the Italian and Belgian comrades”, the militants of the MWG, like them, proposed to make a critical ‘balance sheet’ of the Communist International, in order to create “solid bases for the future communist party of Mexico”.

In the theoretical and political domain, the Mexican communist left showed great boldness, going resolutely against the stream in a country where any group situating itself on an internationalist terrain was open to the most serious threats. Unlike the Stalinists and Trotskyists, Comunismo defined the oil nationalisations in Mexico as reactionary “in the imperialist phase of capitalism” where “there cannot be any progressive measures on the part of decomposing capitalist society and its official representative: the capitalist state”. The strengthening of this state could only have one goal: to save the global property of the national capitalism within the context of imperialist decadence and to protect it against ‘its’ workers and peasants. Furthermore, the nationalisation of oil did not put an end to the domination of foreign imperialism. By going against British interests, Cardenas had merely strengthened the grip of the USA on the Mexican state.

Taking up the thesis of Rosa Luxemburg, the MWG rejected any defence of ‘national liberation struggles’. “Even in the oppressed countries”, the workers have no fatherland or ‘national interest’ to defend. “One of the fundamental principles which has to guide our whole tactic on the national question”, Comunismo continued, “is anti-patriotism...whoever proposes a new tactic which goes against this principle abandons the ranks of marxism and goes over to the enemy”.

The positions of the MWG seemed to the Italian Left like “rays of light” coming from a distant country in the worst conditions of existence. They demonstrated that the positions it defended were not merely products of its own imagination, but of a whole movement of the communist left which went beyond the restricted boundaries of Europe.

What balance-sheet did the International Communist Left draw from the whole debate which it had carried out, directly or indirectly, on the two continents of Europe and America:

• “The task of the hour: no betrayal”. In order to prepare the revolution in the next world war every political group of the communist left had to hold on to the principles of internationalism, against the stream. The counter-revolution exerted a merciless pressure: as in 1914, the historic period was “a period of extreme selection of the cadres of the communist revolution where you have to know how to remain alone in order not to betray” (Bilan no. 39, Jan-Feb 1937, ‘Que Faire? Retourner au parti communiste, messieurs!’). The war in Spain had carried out this pitiless selection, demarcating the proletarian from the capitalist camp:

“The war in Spain has been decisive for everyone: for capitalism, it has been the means to enlarge the front of forces working for war, to incorporate anti-fascism, the Trotskyists, the so-called left communists and to stifle the workers’ awakening which appeared in 1936; for the left fractions, it has been the decisive test, the selection of men and ideas, the necessity to confront the problem of war. We have held on, and, against the stream, we are still holding on.” (Bilan no. 44, October 1937, ‘La guerre impérialiste d’Espagne et le massacre des mineurs asturiens’).

• “The virtue of isolation”. The Italian Left made these words of Bordiga its own, not with satisfaction but with bitterness. It remarked that its isolation was not fortuitous:

“It is the consequence of a profound victory of international capitalism, which has even succeeded in corrupting the groups of the communist left whose spokesman has up till now been Trotsky” (Bilan no. 36).

But this terrible isolation was a precondition for the life, the very survival, of all the revolutionary elements. The latter, in order to move towards the formation of left fractions in all countries, had to “desert the dens of the counter-revolution; destroy them, and thus preserve the minds of working class militants who can work for communist clarification”. It was not possible “to transform the capitalist terrain into a proletarian terrain” (Octobre, no. 4, April 1938, ‘Pour une fraction française de la gauche communiste’). On this capitalist terrain, the Italian left placed not only the anarchists and the Trotskyists, but also Union Communiste, the RWL and the LCI who had “gone over to the other side of the barricade during the massacre in Spain”. (Bilan no. 40, ‘La pause de Monsieur Leon Blum’, April-May 1937).

The International Bureau of the Fractions: the weakness of the Communist Left

Insisting that the future world communist party could only be born out of the left fractions, the Italian and Belgian Fractions formed, in early 1938, the International Bureau of the Left Fractions whose organ was Octobre. The balance-sheet of 10 years of existence could, it seemed, close on a positive note, with the foundation of the Belgian Fraction, the contacts with Comunismo, but above all the hope of being able rapidly to form a French Fraction, since there had been a certain influx of French militants.

The other side of the coin to this international organisation of the communist left, which it saw as the basis for the creation of a new Communist International, was the creation of an anti-Italian Left coalition to the left of Trotskyism. In March 1937, on the initiative of Union Communiste, an international conference was held in Paris. Union Communiste had invited the POUM and the organisations of the IVth International, who didn’t reply. All the groups which had been opposed to Bilan on the question of Spain were there: The LCI, the minority of the Italian Fraction, the RWL represented by Oehler, Field’s group, the League for a Revolutionary Workers’ Party, the GIC from Holland (represented by Canne-Meijer) and individuals like Miasnikov, Maslow and Ruth Fischer, representing the old Russian and German oppositions. The failure of this conference led to the RWL creating an ‘international contact commission’, since UC was unable to take up the task of international coordination [11].

The cordon sanitaire which all these groups had in fact put around the Italian Left undoubtedly limited the efforts of the two Fractions to regroup the revolutionary elements which existed on both continents. An overestimation of its forces soon led the ICL to develop a theory that the way was open to the upsurge of the world revolution, under its leadership. Seeing the revolution on the horizon, it lost sight of the war which was lapping at its feet.

Indirectly, the minority of the Italian Left had a posthumous revenge. Although the majority had always fought the minority’s view that the revolution was possible at any moment, it was now the former which joined them in underestimating the danger of war. Another posthumous victory of the minority was chalked up when, shortly before its disappearance, Bilan started a campaign of solidarity for all the victims of the war in Spain. With the aim of showing that “the left fractions are not insensitive to the martyrdom and suffering of the war in Spain”. Bilan and Communisme decided to create a fund of financial solidarity to help the victims of the war, whether “fascist” or “anti-fascist”, “the families of all, the children of all” [12].

This campaign began from a political vision, which was to differentiate itself from the two military camps. But it ended up in a sort of ‘Red Cross’ under the auspices of the Italian Left. While this was not the Italian Left’s intention, Vercesi in 1944 acted as the executor of this campaign, when he founded, in Brussels, an Italian Red Cross to help “all Italians who are victims of the war” [13].

Isolated politically, the communist left was led into the trap of denying its isolation, denying the reality of the danger of war, and of finding non-political recipes to break out of it. Profoundly affected by the Spanish drama, deeply wounded by the split in its ranks, it gave way to the indirect penetration of positions which had always been alien to it and which the minority had defended better than anyone in 1936.

Notes

[1] A police report dealing with the Brussels section (‘Direzione centrale Della P.S., sezione prima no. 441/032029’) noted that on 1st August 1936, a discussion had emerged on the events on Spain. There was a vote on the enrolment of militants in the ‘revolutionary legions’. For, were Russo, Romanelli, Borsacchi, Atti, Consonni. Against, only Verdaro and Perrone.

[2] Jean Rabaut (op cit.) wrongly asserts that "the Bordigists stuck the schema of the beginnings of the Russian revolution onto the reality of the Spanish events”. The majority rejected any assimilation of the Spanish events with those of February 1917. It was the minority who saw July 1936 as a repetition of ‘February’, and Franco’s attack as an undertaking similar to Kornilov’s. For Bilan, for there to be a ‘Kornilov’, there also had to be dual power - the power of the state and the power of the soviets. In Spain, after a few days of indecision, there was only one power - that of the Republican state, alongside the forces of Franco.

[3] A short account of the activity of the minority and the majority in Spain can be found in Battaglia Communista, no. 6, 1974, ‘Una pagina di storia nella nostra frazione all’estero (1927-43)’. This article, based on the testimony of old militants of the Fraction, retraces the activity of Aldo Lecci, one of the most determined spokesmen of the majority. From this trip by three delegates from the Italian Left was born the pamphlet by Mitchell (Jehan): The War in Spain, 1937, edited by the Belgian Fraction (reprinted in Invariance no. 8, Oct-Dec 1969, and, published in English in Revolutionary Perspectives no. 5, 1976).

[4] This exclusion, or rather this separation on both sides, did not stop Bilan from saluting with emotion the memory of Mario di Leone (1890-1936), known in the Fraction as Topo, and a militant since he left Russia for France in 1929. He died in Barcelona of a heart attack. He was the only member of the minority not to return alive from Spain (cf. Bilan no. 37, for his biography).

[5] According to H.Chazé (in Jeune Taupe no. 6, July 1975), Union Communiste “took in the quasi-totality of the Parisian Bordigists (most of them Italians), 20 good worker comrades who had not digested the lunatic position of the Belgian Bordigists and of Vercesi (no Bordigist party in Spain, so no revolution) on the revolutionary movement on the Peninsula...”. Caught up in his polemic with Bilan, or lacking information, Chazé is deforming reality here. While the figure given for the minority is correct, it is not true that they represented the “quasi-totality of Parisian Bordigists”. At the beginning they were a majority in the Paris section, but they were a minority in the Parisian Federation which grouped together all the sections of the Paris region. Moreover, the Executive Committee of the Federation took a position against the minority right from the start.

[6] L’Internationale no. 23, 28 Oct 1936, in Chronique de la Révolution Espagnole (1933-39) by Chazé, Spartacus, 1979.

[7] ‘La masacre de Barcelona: una leccion para los trabajadores de Mexico’, Mexico, DF, mayo de 1937, Apartado postal 9018.

[8] ‘Grupo de trabajadores marxistas: a las organizaciones obreras del pais y del extranjero’. This text retraced the itinerary of the militants of the group, and denounced the “campaign of slanders” by the Liga Comunista and the PCM (Mexican Communist Party). It explained the positions of the MWG on Spain and the Sino-Japanese war.

[9] On the political itinerary of Paul Kirchhoff (1900-72), cf. apart from the above text, the passages in the complete works of Trotsky, vols. 4 and 6. His positions in the RWL appear in L’Internationale no. 33, 18/12/37.

[10] After 1939, it is impossible to know what happened to the MWG. We only know when Kirchhoff died. (The principal texts of Comunismo were translated in L'Internationale no. 34 and 39; Communisme no. 4 and Bilan no. 43, and reproduced in the ICC’s International Review (nos: 10 (July 1977), 19 & 20 (Oct and Dec 1979).

[11] cf. Lf Internationale no. 27, 10 April 1937, ‘La conférence internationale des 6 et 7 mars’.

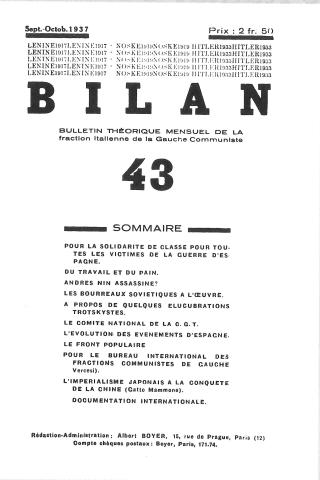

[12] “The Belgian and Italian Fractions, faced with the impossibility of participating in any of the forms and organs of solidarity set up by the Popular Front, but wishing to participate in class solidarity without falling into the grip of the imperialist war, have decided to create a solidarity fund for all the proletarian victims of Spain.” (Bilan no. 43, Sept-Oct 1937, ‘Pour la solidarité de classe pour toutes les victimes de la guerre d’Espagne’)

[13] This campaign, which was based on the idea of the trade union united front, led the Belgian Fraction, or at least a minority of it, to participate in an ‘International Commission for Aid to Spanish Refugees’. From the trade union or humanitarian united front to the position of the anti-fascist front, there was only one step to take, and this was taken by Vercesi in 1944-45 (see below). This campaign met with strong opposition in the Italian Fraction in Marseille and Paris (cf. II Seme Comunista, no. 4 and 5, Nov 1937 and Feb 1938).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace