Submitted by ICConline on

6: Towards war or revolution? (1937-39)

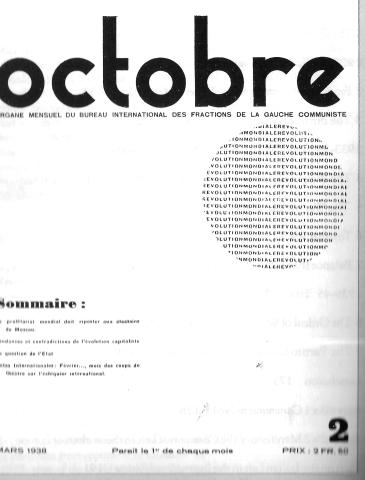

In February 1938, the first issue of Octobre appeared. Five issues were published, up until August 1939. This review was the monthly organ of the International Bureau of the Fraction of the Communist Left. Like Bilan it was printed in Brussels, where the editorial work was done. Legal responsibility for the publication was in the name of Albert Boyer in Paris. The events in Spain had led Gaston Davoust (Chazé) to refuse to go on assuming such responsibility for the organs of the International Communist Left.

An international review, Octobre was to have appeared in three languages: French, German, and English. The Communist Left announced that “soon it would publish the English and German editions” and appealed vigorously to “German comrades” owing to “its real difficulties in producing German translations”.

The disappearance of Bilan and its replacement by Octobre was symptomatic of a profound change of orientation in the Italian and Belgian Fractions. The cover was decorated with a circle representing the terrestrial globe, over which were printed the words ‘world revolution’. The title Octobre clearly showed that the Communist Left believed that the world was on the eve of a new ‘Red October’.

The constitution of an International Bureau at the end of the year 1937 corresponded to the hope of forming the bases of a new International. The example of Zimmerwald, which had been at the origin of the 3rd International, was in the minds of all the militants. The betrayal, since 1933, of all the Communist and Trotskyist parties - like social democracy in 1914 - meant, for the Italian Left, that it alone had the task of being the centre of a 4th International. The work done in the past, which “has consisted above all in making contact with the individuals who, in different countries, have taken a position of combat against the imperialist war”, had now to give way to “another phase of work towards the constitution of left fractions” (Bilan no. 43, ‘Pour le bureau international des fractions communistes de gauche’, by Vercesi).

The creation of an International Bureau linking the two Fractions undoubtedly represented a strengthening of the Italian Communist Left. The constitution of an international centre before the outbreak of the war - the Zimmerwald left animated by the Bolsheviks had emerged during the World War - gave the illusion of being better prepared than the Bolsheviks themselves.

Apparently the ‘balance sheet’ was closed, with “the liquidation of all the groups who have since terminated their evolution”; ideologically, the International Bureau had the impression that, in the proletariat, this liquidation had left it a clear field, had put it in a situation where the treason of the old ‘workers’ parties’ had been clearly marked, without the need to go through a brutal and demoralising second ‘4 August 1914’.

But was the ‘bilan’ really closed? The discussions which continued in the two Fractions, through Octobre and the internal bulletin, II Seme Comunista, on the questions of the state and of the unions, showed that this ‘bilan’ was in fact far from complete (see next chapter).

War or revolution?

Above all, as local wars got nearer to Europe, heralding the final conflagration, the position of the International Communist Left became less assured. ‘Localised’ wars announcing the world revolution? World imperialist war? War or revolution - or war and revolution? This was the historical dilemma posed each day to the two Fractions. The cohesion of the ‘Bordigist’ organisation depended on its capacity to respond clearly to this situation.

In continuity with Lenin and Trotsky’s 3rd International, the Italian Left, from the beginning, did not try to avoid the dilemma which had been posed by marxist theoreticians: ‘war or revolution’? It was within this tradition of the Comintern that Bilan in December 1933 evaluated the existing relationships between these two historical poles:

“In the imperialist phase of capitalism, and from the general point of view, there are only two outcomes: the capitalist one of war, the proletarian one of revolution. It is only the insurrection of the workers which can prevent the outbreak of the war.” (Bilan no.2, ‘Une victoire de la contre-révolution: les Etats-Unis reconnaissent l’URSS’).

The publication of Bilan corresponded to the affirmation that a whole series of proletarian defeats, from 1923 to 1933, had opened up a historic course towards world war. Ideologically this was expressed in the triumph of the counter-revolution in Russia and within the parties of the Comintern. The Italian Fraction’s certainty that war was inevitable was not based on a fatalist conception of history, any more than it implied a renunciation of any intervention in the French, Belgian and American proletariat. On the contrary, through leaflets and manifestoes, the Italian Left continually warned the workers - even in the euphoria of the strikes of 1936 - of the danger of a world conflict. But as long as the balance of forces had not changed in favour of the proletariat, the course towards war remained open.

In fact, the annihilation of the proletariat had already been completed; in this annihilation - which was more ideological than physical - the role of Russia had been decisive:

“War is only possible through the elimination of the proletariat as a class from the historical scene. This in turn is brought about by a long work of corruption of the proletarian organisms, who end up betraying and rallying to the cause of the enemy.” (Bilan no. 16, March 1935, ‘Projet de résolution sur la situation internationale’, by Phillippe) [1].

But if the war demanded this annihilation of the proletariat, how would it have the strength to transform the imperialist war into a civil war? Could the world revolution arise out of a total defeat?

According to the Italian Left, war would, as in 1917, necessarily lead to revolution. It even thought that “in comparison to the previous war, it is certain that the role of the proletariat will be enormously increased, and that the possibility of a resurgence of class struggle will be all the greater”. It considered that the growing accumulation of arms implied “the necessity to set up enormous industrial workshops and to make the whole population participate in them”. This would “enable the proletariat to become aware of its interests more quickly because circumstances would show it that it is less difficult to challenge discipline and hierarchy in the workshops than in the ranks of an army in trenches far away from the home front”. (Bilan no. 16, March 1935 ‘Projet de résolution sur la situation internationale’, by Phillippe).

This extremely optimistic view, defended by Vercesi, was not accepted unanimously in the Italian Fraction. In a discussion article, Gatto Mammone implicitly attacked this perspective of a quasi-automatic transformation of world war into revolution, all the more because Vercesi had underlined the “pulverisation of the proletariat”:

“… those who stress most strongly the proletariat’s powerlessness, dislocation, and pulverisation before the war, also insist most strongly on the immediate class capacities of the workers after the war. They thus attribute a sort of thaumaturgic virtue to the war in itself as a factor in the maturation of the proletariat, and look with haughty disdain at those who believe in a more or less long phase of transition and in the bourgeoisie's capacity for manoeuvre during these moments.” (Bilan no. 29, March-April 1936).

However, the strikes in France and Belgium, and above all the war in Spain - even though the majority saw this as an imperialist war, the rehearsal for a confrontation between the ‘democratic’ and ‘fascist’ blocs - were to plunge the Italian Fraction, and to a lesser extent the Belgian Fraction, into an attitude of expectantly and hopefully waiting for the war. All these social movements, despite being crushed, could be seen as harbingers of the world revolution.

Theoretically, however, the Italian Left could not be content with simply reacting after the event. It had both to verify the validity of its 1933 prognosis that war was inevitable, and to see whether the changes that had taken place in capitalism since the crises of 1929 did not imply changes in the historic perspective, and thus in communist politics.

The theoretical debate in the Italian Left revolved around three themes:

- the nature of war since 1914, and the communist attitude towards it;

- the economic and social implications of the war economy;

- the nature of local conflicts since 1937, and the revolutionary perspective.

It was crucially important for the Italian Left to grasp the nature of wars in a period which it defined - in the tradition of the Comintern’s first congresses - as that of the decadence of capitalism. This theory of decadence determined all the political positions that the Italian Left took up in each conflict.

The roots of imperialist war: the decadence of capitalism

Like Lenin, to whom it referred, the Fraction saw imperialism as the final stage of capitalism. In this phase in the transformation of capital, there was a struggle between different capitalist states to divide and re-divide the globe, in particular for the control of sources of raw materials needed for production. Nevertheless, this theory tended to ignore the problem of the markets needed for all the commodities produced. The stammerings of the Russian communist movement in its attempt to define the historical period opened up in 1914 left a whole field of theory to go into.

It was the discovery of Rosa Luxemburg’s works, newly translated into French, that was to direct the Italian Left towards a theory based on the affirmation of the decadence of capitalism and the saturation of the world market. The crisis of 1929, a world crisis of overproduction, seemed to provide striking confirmation of the theses which Luxemburg had defended in The Accumulation of Capital in 1913. It appeared as a clear refutation of Bukharin’s theory, which had asserted that there were no limits to capitalist expansion outside the direct sphere of production [2]; the development of the latter was held back and contradicted only by the tendency for the rate of profit to fall. In the 1930s, even non-marxists, faced with a crisis which was no longer local and conjunctural as in the 19th century, but truly world-wide, did not hesitate to talk about the decline and decadence of capitalism. The very length of the crisis from 1929 to the end of the world war, the dizzying fall in production and world trade, the development of autarchic policies showed that the crisis of 1929 was not a ‘classical’ crisis that would be quickly overcome by a new surge in the productive apparatus. [3]

It was Mitchell and the Belgian Fraction who were to take up and develop the ‘Luxemburgist’ theories which had been defended more intuitively than in depth by the Italian Fraction. Mitchell’s contributions were decisive. They appeared in Bilan in a series of articles entitled ‘Crise et cycles dans l’économie du capitalisme agonisant’ (nos.10 and 11, August and September 1934). The pamphlet he published in 1936, in the name of the LCI, Le problème de la Guerre, developed the political implications of this analysis.

Mitchell showed that the 19th century had been the epoch of the full ascendancy of the capitalist mode of production, with the increasing development of a world market. This development had a progressive character in that it was ripening the conditions for the revolution:

“It was this fundamental, motivating law of capitalist ‘progress’ which pushed the bourgeoisie ceaselessly to transform into capital a growing fraction of the surplus value extorted from the workers, and consequently, to develop incessantly the productive capacities of society. Thus its historical and progressive mission was revealed. On the other hand, from the class standpoint, capitalist ‘progress’ meant growing proletarianisation and the endless intensification of exploitation. Capitalism was not progressive by nature, but by necessity. It remained progressive as long as it could make progress coincide with the interests of the class which it expressed.” (‘Le Problème de la Guerre’, January 1936).

The crises which regularly disturbed the process of accumulation in this phase were “chronic crises”. Periods of crisis and prosperity were “inseparable and conditioned each other reciprocally”. Here Mitchell referred to Rosa Luxemburg for whom “crises appeared as a means to further stoke up the fires of capitalist development”.

The contradictions which underlay the capitalist system - the tendency to accumulate ever more capital and to metamorphose this into an excess of commodities on the national market - were resolved through the extension of the market, and above all through capital’s penetration into extra-capitalist zones. In his series of studies, Mitchell affirmed that “the annexion to the capitalist market of new zones, new regions, where backward economies survived, and which could serve capitalism as outlets for its products and its capital” provided a solution to this contradiction. Colonial wars had the function of enlarging the capitalist market. The national wars which had “supported the bourgeois revolutions of the previous century” were succeeded by colonial wars which, by completing capitalism’s domination over the globe, accelerated the contradictions of a system that had become imperialist:

“... extensive colonialism was limited in its development, and capitalism, an insatiable conquerer, soon exhausted all the available extra-capitalist outlets. Inter-imperialist competition, deprived of any way out, moved towards imperialist war.” (Bilan no. l 1, op.cit.).

Once the world had been divided up by the various imperialisms, capitalism world-wide ceased to be progressive:

“Once these big capitalist groups had finished dividing up all the good land, all the exploitable wealth, all the spheres of influence, in short all the comers of the world where labour could be despoiled and turned into gold for piling up in the national banks in the metropoles, the progressive mission of capitalism was also finished.” (‘Le Problème de la Guerre’)

The war of 1914 meant “the decline, the decomposition of capitalism”. “The era of specifically colonial wars was definitively over”, to be replaced by the era of “imperialist war for a new division of the market between the old imperialist democracies whose wealth went a long way back and which were already parasitical, and the young capitalist nations which had arrived late on the scene.” (ibid)

War no longer expressed the ascent of capitalism, but its general decadence, characterised by “the revolt of the productive forces against their private appropriation”. From being “chronic” the crisis became permanent, “a general crisis of decomposition”, which “history would register as a series of bloody and agonising convulsions” (Bilan no. ll, op.cit.). According to Mitchell the characteristics of this were:

- “a general and constant industrial overproduction”;

- “permanent mass unemployment, aggravating class contrasts”;

- “chronic agricultural overproduction”;

- “a considerable slow-down in the process of capitalist accumulation resulting from the narrowing of the field for the exploitation of labour power (organic composition) and the continuous fall in the rate of profit”.

On the basis of this theoretical analysis, examining the crisis of 1929, Mitchell concluded that “capitalism was being pushed irresistibly towards its destiny, towards war” (ibid), a war which would involve “a gigantic destruction of inactive productive forces and of innumerable proletarians ejected from production” (‘Le Problème de la Guerre’).

Thus, the wars of the decadent epoch could not be compared to the national wars of the previous century. They were no longer the product of a few states like Germany or Italy, but derived from a global process pushing all states towards war. There could no longer be any “just wars” or opposition between “reactionary states and progressive states.” (ibid)

The political consequences of this analysis were in continuity with the positions of the Bolsheviks and Rosa Luxemburg. “The two terms of the historic alternative” were “proletarian revolution or imperialist war” (ibid).

Consequently the two Fractions rejected any form of ‘national defence’ in any country, including the USSR, as well as any ‘pacifist’ policy like that of the ‘Amsterdam-Pleyel Committee’ in the 1930s. For the Fractions, as in 1914, the only possible struggle was not for ‘peace’ but for the world revolution, against any ‘fascist’ or ‘anti-facist’ war, which could only mean the destruction of the proletariat:

“War is not an accidental but an organic manifestation of the capiitalist regime. The dilemma is not 'war or peace’ but ‘capitalist regime or proletarian regime’. To struggle against war is to struggle for the revolution.” (Bilan no. 11, ‘La Russie entre dans la SDN’).

“The working class can only call for one kind of war: the civil war directed against the oppressors in each state and concluding in the victory of the insurrection.” (Bilan no. 11, ‘Projet de résolution sur la situation internationale’ by Phillippe).

On the basis of this whole analysis of the world-wide decadence of the capitalist system, the Italian and Belgian Fractions deduced that national liberation struggles by the colonial peoples were impossible and could only be a link in the chain of imperialist war.

The reactionary function of national movements in the colonies

Against Lenin and the theses of the 2nd Comintern Congress, which called for support to national movements in the colonial countries, the Italian Left openly took up the positions of Rosa Luxemburg.

Bilan, whom Union Communiste accused of being “more Leninist than Lenin” was not afraid of opposing Lenin on this question, or of challenging Marx’s position in the previous century. As it said, “Marxism is not a bible, it is a dialectical method; its strength resides in its dynamism, in its permanent tendency to elevate the formulations acquired by the proletariat in its march towards the revolution...” (Bilan no. 14, January 1935, ‘Le Problème des minorites nationals’).

Bilan thus rejected not only “the right of peoples to self-determination” posed by Lenin in 1917, but also the Baku theses which preached “the holy war of the coloured peoples against imperialism”. Bilan courageously rejected the sacred dogmas and, in evaluating these movements, saw them as the antithesis of the proletarian revolution, and as being tied up with imperialism:

“...we have no fear in showing that Lenin's formulation on national minorities has been overtaken by events and that the position he applied after the war has shown itself to be in contradiction with the fundamental aim given to it by its author: to aid the development of the world revolution.

“Nationalist movements, terrorist gestures by representatives of oppressed nationalities today express the impotence of the proletariat and the approach of war. It would be wrong to see their movements as an ally of the proletarian revolution, because they can only develop on the basis of the crushing of the workers and thus in connection with the movements of opposing imperialisms.” (Bilan no. 14, ‘Le Problème des minorites nationales’).

This analysis, which differentiated Bilan from other currents of the inter-war period, such as Trotskyism, was not however unique to Bilan. It was also defended by Union Communiste which took up the tradition of the German Left on the national and colonial question, as represented by the KAPD and the Groep van Internationale Communisten (GIC). [4].

On the theoretical level, Bilan based its position of refusing in principle to support national and colonial movements on the impossibility of development. The imperialism of the great industrial powers stood against the constitution of new autonomous capitalist nations, which could only be subordinated to imperialism:

“Metropolitan capitalism, sinking under the weight of a productive apparatus which it can no longer make full use of, cannot tolerate the constitution in the colonies of new industrialised capitalist states capable of competing with it, as was the case with the old colonies like Canada, Australia and America. Imperialism stands against any developed industrialisation, any economic emancipation, any national bourgeois revolution.” (‘Le Problème de la Guerre’).

On the political level, the Italian Left considered that the crushing of the Chinese proletariat by the 'indigenous’ bourgeoisie in 1927 had sufficiently demonstrated the reactionary role of any national and colonial bourgeoisie faced with its real enemy the proletariat. Consequently, “any progressive evolution in the colonies has become bound up not with so-called wars of emancipation of ‘oppressed’ bourgeoisies against the domination of imperialism, but with civil wars of the proletariat and the peasant masses against their direct exploiters with insurrectionary struggles carried out in liaison with the advanced proletariat in the metropoles”.

When the conflicts between Italy and Ethiopia, then between China and Japan broke out, the Italian Fraction refused to give any support to the Negus or Chiang. Supporting them meant not only apologising for the butchers of the indigenous workers and peasants, but aided the march towards world war, where each local conflict expressed the confrontation between the imperialist powers in order to divide up the world.

Thus, the civil war in every country, the struggle of the proletariat “against its own bourgeoisie, whether fascist or democratic, progressive or reactionary 'oppressed’ or 'imperialist’” appeared to Bilan and Communisme as the only historic alternative to any other war which “independent of its aspects” was “imperialist”. (Communisme no. 9, 15 Dec. 1937 ‘La guerre impérialiste en Chine et le problème de l’Asie’, résolution of the Belgian Fraction).

The discussions over the war economy

While the theoretical and political framework of the Communist Left was posed in a rigorous manner, its actual analysis of the march towards war remained partly undecided.

From 1936 on, the Italian Fraction began to become preoccupied with a phenomenon which had plunged it into great perplexity: the war economy. As early as 1933-34, a revival of economic activity had been seen in every country. In Germany, in Russia, in the USA, unemployment tended to diminish, the indices of growth in production became healthier. The military budget was three times what it had been in 1913. Through its orders, the state was supporting a whole market for arms. Would the production of arms, by providing outlets for production, allow capitalism to do without a war? [5].

If the war economy represented a way out of the world crisis, how was one to explain the multiplication of armed conflicts from Asia to Africa, from Spain to central Europe? Was it that by using ‘localised’ wars as an outlet for the arms it had accumulated, the war ecomomy was putting off or even cancelling the world war?

Finally, did the rise in wages and the reduction in the working day in countries like France and Belgium, the Keynesian policies of ‘full employment’ and ‘maintaining consumption’ in the USA and Britain mean that the perspective of proletarian revolution was becoming more distant? In this case, did it mean that economic struggles - whose potentially revolutionary character the Italian Left had always underlined - had become futile if, as in 1936, they only tied the workers to the governments who made concessions to them?

All these questions began to preoccupy the Fraction from 1936 on, without a satisfactory answer being given. The debate which took place in the ‘Bordigist’ organisation was to reveal profound differences, with the most serious consequences.

The ‘orthodox’ position of the Italian Left on the war economy was defended above all by Mitchell, who, in the Belgian Fraction, had followed the world economic situation in great detail. For him, and for others in both Fractions, the war economy was simply economic war turning into military war.

Its function was thus in contradiction with the ‘classical’ development of capitalism founded on the enlarged reproduction of capital and of the productive forces. It had a negative effect, by congealing capital accumulated on a world scale, capital which was not reinvested in the productive sector, and above all, through the massive destruction of capital by the arms it produced. Communisme (no. 12, ‘Rapport sur la situation internationale’) stated very clearly that “...war production involves a colossal unproductive consumption of the labour and wealth which are the vital resources of society”. The Belgian review added that war could not be an ‘economic’ way out for the system when considered from the global rather than the national standpoint. World and even local war meant “the annihilation of millions of proletarians and the destruction of incalculable riches embodying capitalist surplus value”. It is interesting to note that this text did not exclude the possibility of a period of reconstruction since the phase of destruction “would be followed by a phase of ‘reconstruction’ and the reanimation of moribund bourgeois society” (ibid).

Vercesi and a part of the Italian Fraction, on the other hand, thought that the phenomenon of a revival of production through the growth in arms production required a modification of theory. The phenomenon of state capitalism in all countries, which the Italian Left saw as a “world-wide tendency”, and the “manipulation of the weapon of credit”, seemed particularly significant. While they “only allowed for an industrial development in the particular domains of military production”, they could “nevertheless serve the interests of capitalism, above all by preventing an economic collapse...” (Bilan no. 24, Oct-Nov. 1935, ‘La tension de la situation italienne et internationale’).

In fact Vercesi and his tendency were more or less saying that state capitalism, on the basis of the war economy, represented a new solution to the crisis, resolving the question of the realisation of production on the world market:

“The present economy, dominated by the hegemony of war production, makes it possible to prevent the market from being immediately overloaded by the invasion of the predominant part of production, and because of this, both economic and class contrasts have shifted: it is no longer the market which reveals the antagonistic basis of the capitalist structure, but the fact that from now on the greater part of production is deprived of any possibility of finding an outlet.”

If arms production overcame the contradiction of the market, it necessarily had to overcome the system’s contradictions as they erupted into economic crisis:

“This transplantation of the axis of the capitalist production has as its direct repercussion in the structure of the system a gigantic elevation in the rate of surplus value, without the resulting production immediately leading to an outbreak of the contrasts specific to the bourgeois regime.” (Bilan no. 41, May-June 1937, report on the international situation presented by Vercesi to the Congress of the Italian Fraction).

Vercesi, basing his analysis on the measures taken by the Popular Front and the New Deal, deduced that in this manner capitalism could reduce social tensions by according substantial reforms to the workers:

“... capitalism is managing to raise the rate of exploitation while at the same time conceding wage increases, paid holidays, reductions in the working day.” (Bilan no. 43, Sept-Oct. 1937, ‘Pour le Bureau International des Fractions Communistes de Gauche’, by Vercesi).

In these conditions, struggles for immediate demands lost any class content. Economic struggles could no longer lead to revolution. Only the direct struggle for revolution could revive the class antagonisms:

“... in the new economic situations which have succeeded the gigantic crisis which opened in 1929, the immediate demand of the working class consists not in calling for wage increases, but in the direct struggle to prevent the setting up of war economies.

“...the class antagonism can only arise out of the contrast between capitalism instituting a situation of imperialist war and the proletariat struggling for the communist revolution.” (Bilan no. 41 op.cit.).

By contrast, in the Belgian Fraction, Mitchell emphasised that the war economy meant neither improvement in real wages, nor the suppression of the economic antagonisms determined by the appropriation of surplus value.

Without denying that the general strike of 1936 had led to wage rises, he insisted that French capitalism could not allow a rise in real wages: “any rise in real wages would automatically lower the rate of exploitation, since... the growth of one inevitably reduces the other.” (Communisme no. 7, Oct. 1937). The intensification of productivity after June 1936, the cascade of devaluations (up to 50% in 18 months), 35% inflation in a few months reduced these wage increases to nothing, resulting in an inexorable fall in real wages. In fact, “the error consisted in thinking that what had been conceded under the pressure of the masses could be definitively incorporated into the programme of capitalism. The truth is that the Popular Front is seeing its theory of increasing the buying power of the masses consecrated by the facts in spite of itself, and that consequently its credit among the masses has been strengthened. This is the political gain for capitalism which makes up for the economic losses brought about by the Matignon agreement.” (ibid).

The Belgian Fraction thus vigorously opposed Vercesi’s theory about the disappearance of the economic struggle, according to which “successful struggles for demands in some way lead to the workers collaborating with the organisation and functioning of the war economy, and thus to adhering to the policy of the Union Sacrée which is precipitating them towards imperialist massacre” (Communisme no. 8, Nov. 1937, ‘Les convulsions de la décadence capitaliste dans la France du Front Populaire’). Against this view, Mitchell, while conceding that the partial struggle remained the least elevated form of the class struggle, insisted that the economic struggle “still remains an expression of class contrasts and cannot be anything else”. It was not “an objective in itself, but a means, a point of departure”. Its importance remained crucial “when the workers use their specific weapon, the strike, which is precisely what capitalism wants to destroy”. In a “profoundly reactionary phase” it would have been utopian to replace the economic struggle with “the struggle for power” and would run the risk of falling into the position of Trotsky which called for “the expropriation of the capitalists” in France, (ibid).

Vercesi was to defend this theory of the war economy up until the war (see below). He had not yet made the leap to saying that the proletariat had disappeared socially - this came later. Indeed he was one of those who saw the world revolution on the horizon. If the proletariat could no longer struggle on the economic level, its struggle immediately became revolutionary, spontaneously breaking out on the political level. The new historic period would be one of a civil war by the world bourgeoisie to destroy the revolutionary forces of the proletariat country by country.

Since the war in Ethiopia, a generalised war seemed to be in the offing, and it was difficult to deny all the conflicts which signalled this process. All the members of the International Communist Left were unanimous in thinking that the revolution would come out of the war. How could Vercesi reconcile this certainty with his theory of the war economy, the implicit result of which was to deny that world war was capitalism’s only way out?

• The Theory of ‘Localised Wars. In 1937, at the foundation of the International Bureau of the Fractions, Vercesi and a small minority gave an answer which could appear coherent. The war economy made inter-imperialist conflicts secondary. The bourgeoisie could postpone the world war. By drawing on classical marxist theory, which holds that all history is the history of the class struggle, they asserted that the only contradiction undermining capitalist society was a social one, the opposition between bourgeoisie and proletariat:

“As far as I am concerned, I believe that this conflagration (the war) will not take place and that from now on the only form of war corresponding to current historical evolution is the civil war between classes, whereas inter-imperialist contrasts can be taken towards a non-violent solution. …

“Inter-imperialist competition is a secondary and never a fundamental element. In 1914 it played an important role, but again only as an accessory: the essential thing was the struggle between capitalism and the proletariat” (Bilan no. 43, op.cit.).

They deduced from this that imperialist war had changed its function. It was no longer a question of “conquering new markets” (Bilan no. 38, ‘Guerre civile ou guerre impérialiste?’), nor even of a redivision of the world. War had become “the extreme form of capitalism’s struggle against the working class”. It had only one aim: to massacre the proletariat, “the destruction of the proletariat of each country” (ibid) [6].

This theory was profoundly marked by the events in Spain, where the workers’ uprising of July ’36 had been derailed into an imperialist war. When a war broke out, this could only mean that a revolutionary proletarian movement had been crushed by resorting to the modern form of imperialist war:

“Each time a war breaks out, the problem is not ‘what imperialist interests are at stake?’. The problem that has to be posed is rather ‘what social contrasts are being deviated towards the war?’” (Bilan no. 46, ‘Contrastes inter-impérialistes ou contrastes de classes: la guerre impérialiste en Chine’).

For the bourgeoisie, these ‘localised wars’ also had the advantage that they prevented generalised war, that they “diverted their conflicts into zones where they did not confront each other directly”. While at the same time feeding their economies with arms production. This meant that there was an “inter-imperialist solidarity” (ibid).

Pushed to its most absurd conclusions, this theory had a dual effect:

• the Fractions had a tendency to see each attack on the proletariat as announcing the revolution. Thus, Bilan could write that “Stalin, the last reserve of world capitalism, through the very excessiveness of the tortures he is inflicting” heralded “the approach of great revolutionary storms” (Bilan no. 39, January-February 1937, ‘Les proçes de Moscou’) Every defeat seemed to miraculously metamorphose into victory;

• the Fractions did not understand the significance of Munich and the occupation of Czeckoslavakia. They believed that the bourgeoisie was trying to avoid a world conflict, haunted by the fear of provoking a new October 1917 [7].

In fact, although there was strong opposition to the theses of Vercesi and his tendency, both Fractions were profoundly confused by all this. Believing in the possibility of a revolution coming out of a world war, they considered that the different imperialisms had every interest in avoiding one. At the same time, they could hardly deny the real danger of world war. Thus disorientated, they found it “difficult to say whether capitalist society was definitively moving towards world war, or whether the perspective opening up was the development of the class struggle towards the revolution” (Communisme no. 3, June 1937, ‘La situation internationale: tendances de révolution capitaliste’)

This inability to take position decisively on the historic course considerably weakened the Fractions. Since the revolution did not come, the theory no longer corresponded to reality. Demoralisation began to take its toll. Resignations multiplied. Octobre suspended publication for a year, until its last issue in August 1939. In the opinion of its own members (among others, Mitchell, Vercesi and Jacobs), the International Bureau was suffering from a “syncope”, a sort of anaemia. Discussion within the Fractions did not produce a coherent and homogeneous position.

In fact, there were three positions confronting each other on the eve of the war:

• Vercesi’s position, still defending the theory of localised wars;

• the position of Mitchell in particular, that Munich would lead to a world conflagration, in which the fascist states would suffer their final defeat;

• a third position believing in “an evolution of world capitalism towards the establishment of regimes of fascist terror in all countries” (Octobre no. 3, ‘Manifesto of the International Bureau of Left Fractions’).

A few days before the war, Octobre had to admit that “the Munich events have profoundly shaken the two Fractions... In the Belgian Fractions, two currents have tried to define themselves; in the Italian Fraction the demarcation is not so clear” (Octobre no. 5, ‘Declaration of the International Bureau of the Fractions of the Communist Left’) [8].

The war was to confirm how bad this situation really was.

Notes

[1] ‘Phillipe’ was the nom de plume Vercesi sometimes used when writing articles for Bilan.

[2] cf. Bukharin’s book, Imperialism and the Accumulation of Capital (reply to Rosa Luxemburg). In the Communist International after 1925, a violent attack was launched against the ‘Luxemburgist’ theses. Its aim was to show the validity of ‘socialism in one country’, since capitalism was able to postpone its contradictions into the far future. According to Bukharin, these contradictions could only develop sharply through “the revolt of the coloured peoples”, depriving “imperialism” of its economic bases. Economically speaking, the main contradiction was the tendency for the rate of profit to fell, and not the markets, which Bukharin called the “third persons”.

[3] Sternberg (in the appendices of The Conflict of the Century) notes that between 1929 and 1932, world production had fallen from 100 to 69. In the USA, production fell by 50%. The number of unemployed in the industrialised countries went from 10 million to 40 million. During the crisis, the value of world trade in dollars fell by 60%.

[4] At the beginning, the Dutch Left, while rallying to Rosa Luxemburg’s theses on the national and colonial question made one exception in its condemnation of ‘national liberation struggles’: the Dutch East Indies.

[5] In his study, Sternberg showed that the indices of industrial production, in relation to the 1929 basis, had gone up by 126 by 1938; in the USA, to 113 by 1937, only to go down to 89 in 1938. But “during the same period world trade did not once return to the 1929 level, much less go beyond it”.

[6] This theory of Vercesi’s, which the LC1 wrongly attributed to all the members of the two Fractions, was described by the LC1 as “purely and simply denying imperialist contradictions, just as it denies any opposition between fascism and democracy”. In its Bulletin of March 1937, the LCI added that “The conception that the bourgeoisie is one and indivisible internationally necessarily has to lead to negating imperialist antagonisms or reducing them to almost nothing. The minimisation of these antagonisms has to lead to the idea that war is the specific struggle of the bourgeoisie against the proletariat. One can hardly imagine a worse aberration.”

[7] A leaflet of the Belgian Fraction distributed after Munich declared: “By concluding the Munich pact, the international bourgeoisie has cynically demonstrated that it knows how to shove aside the quarrels between imperialist clans when it sees the spectre of the revolution emerging. Already caught up in the tumult of mobilisation, already agitated by war fever, it has, in a last minute turn-around, put off the perspective of a world conflict because it has a clear memory of October 1917, because it has a clear memory of its reawakening as a class.” It is true that it added: “To the war threat of 28th September, you must reply by developing your struggles in all countries” (Communisme no. 19, October 1938, ‘A la ‘paix’ impérialiste, il faut opposer la révolution’).

[8] In the Italian Fraction, however, some militants in Paris and Marseilles vigorously opposed the theses of ‘localised wars’ and the war economy. One of these was at the origins of the French Fraction of the Communist Left which arose in 1942 (see below).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace