Submitted by International Review on

The last recession (2000-2001) dealt a serious blow to all the theoretical flights of fancy that had developed around the supposed "third industrial revolution" based on the micro-processor and new information technologies, just as the collapse on the stock exchange demolished all the blather about a new "ownership capitalism" where wage labourers were to become participating shareholders – the umpteenth version of the worn-out myth of "popular capitalism", whereby each worker is supposed to become a "proprietor" through the ownership of a few shares in "his" company.

Since then, the US has succeeded in limiting the extent of the recession, while Europe has got stuck in near stagnation. And so we are told, over and over again, that the secret of the American recovery lies in a greater openness to the "new economy", and in its more deregulated and flexible labour market. By contrast, the lethargy of the recovery in Europe is supposedly explained by its backwardness in both domains. To overcome this, the European Union has adopted the objectives laid down in the so-called "Lisbon strategy", which aims to create, by 2010, "the most competitive and dynamic knowledge economy in the world". In the "employment guidelines" laid down by the European commission, and referred to by the new constitution, we can thus read the member states must reform "overly restrictive employment legislation which affects the dynamic of the labour market" and promote "diversity in terms of Labour contracts, notably as far as working time is concerned". In short, the ruling class is trying to turn the page on the last recession and stock market collapse and to present these as if they were no more than minor details on the road towards growth and competitiveness. They are playing us the old tune of a better future... if only the workers will consent to a few extra sacrifices before they finally reach the earthly paradise. But the reality is very different, as this article aims to show through a marxist analysis of the bourgeoisie's own official statistics. The final part of this article is devoted to refuting the analytical method for understanding the crisis, developed by another revolutionary organisation: Battaglia Comunista.

A systemic crisis

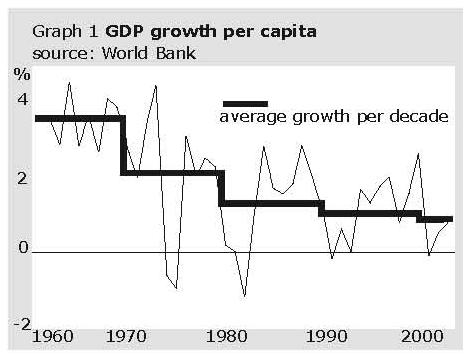

The last recession is far from being a mere unfortunate accident: it is the sixth to strike the capitalist economy since the end of the 1960s (see graph n°1).

In 1967,1970-71,1974-75,1988-82,1991-93 and 2001-02 each recession tended to be both longer and deeper than the previous one, within the context of the constant decline in the average growth rate of the world economy decade on decade. They were not merely setbacks on the way towards "the most competitive and dynamic economy in the world", they were so many stages in the slow but inexorable descent into the abyss which is leading the capitalist mode of production to bankruptcy. Despite all the triumphal speeches about the "new economy", the liberalisation of markets, the enlargement of Europe, the technological revolution, globalisation, not to mention all the repeated puffing of the performance of supposedly emerging countries, at the opening of markets in the Eastern bloc, the development of Southeast Asia and China... the growth rate of world GDP per person has continued to decline decade on decade.[1] Certainly, if we look at indicators such as unemployment, the rate of growth, the rate of profit or international trade, then the present crisis is far from the collapse experienced by the capitalist economy worldwide during the 1930s, and its rhythm is much slower. Since then, and especially since World War II, national economies have increasingly come under an ever more omnipresent direct and indirect control by the state. To this should be added the establishment of economic control at the level of each imperialist bloc (through the creation of organisations such as the IMF for the Western bloc and COMECON for the Eastern bloc).[2] With the disappearance of the blocs the same international institutions have either disappeared or lost their influence on the political level, although in some cases they continue to play a certain role on the economic level. This "organisation" of capitalist production for decades to kept control of the system's own contradictions to a much greater extent than was possible during the 1930s, and explains the slow development of the crisis today. But alleviating the effects of these contradictions is not the same thing as resolving them.

Ever more feeble recoveries

The evolution of the economy today is not like a yo-yo, whose ups and downs are a vital part of its movement. It is part of an overall tendency towards decline, which although it is slow and gradual thanks to the regulatory intervention of the state and international institutions, is nonetheless irreversible.

This is the case with the much vaunted American recovery, so often set up as an example: the United States may have succeeded in limiting the extent of the recession but only at the cost of creating new imbalances which will make the next recession even deeper and its effects still more dramatic for the working class and all the exploited of the earth. If all we did was to note the existence of economic recoveries after each recession, then this would be a pure empiricism, which would not advance us one iota in understanding why the rate of growth of the world economy has declined continuously since the end of the 1960s. The evolution of the economic situation since then reveals the fundamental contradictions of capitalism, and consists of a series of recessions and recoveries, the latter being each time based on more fragile foundations. As far as the recovery of the US economy after the recession of 2000-2001 is concerned, we can see that it is essentially based on three high-risk factors: 1) a rapid and massive increase in the budget deficit; 2) a recovery in consumer spending based on growing debt, the disappearance of national savings, and external financing; 3) the spectacular fall in interest rates that herald increased instability on international money markets.

1) A record growth in the budget deficit

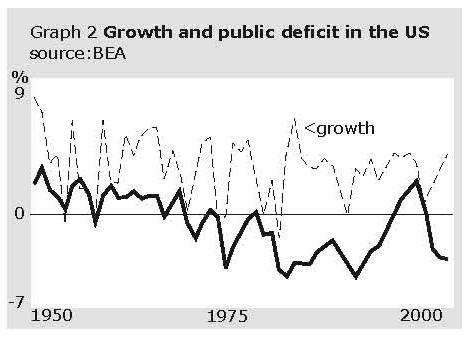

Since the end of the 1960s, we can see clearly (graph n°2) that the recessions in 1967,1970, 1974-75 and 1980-82 were increasingly deep (the dotted line tracks the growth rate of American GDP), whereas those of 1991 and 2001 appear to have been less extensive and separated by longer periods of recovery (1983-1990 and 1992-1999). Are we to suppose that these are the effects of the emergence of this new economy that we are so often told about? Do we see here a reversal of the tendency begun in the world's most advanced economy and which asks no more than to spread throughout the world if only others will copy America's recipes? This is what we will now examine.

To say that economic recoveries exist, even if they are less vigorous than before, does not take us much further unless we examine what drives them. To do so, we have matched the evolution of the United States budget deficit (solid line in graph n°2) with growth in GDP: this demonstrates clearly not only that each phase of recovery is preceded by a major increase in the budget deficit, but also that on each such occasion the latter is greater in either size or duration than on the previous one. Consequently, both the longer phases of recovery during the 1980s and 1990s and the relatively moderate nature of the recessions are explained above all by the size of the US budget deficit. The recovery after the recession of 2000-2001 is no exception to the rule. Without a historically unprecedented budget deficit, both in terms of its size and of the rapidity with which it developed, American "growth" would look more like deflation. From a surplus of 2.4% in 2000, the budget deficit has now reached 3.5% as a result of the decrease in taxation (essentially for higher incomes) and increased military spending. Moreover, and contrary to the promises of the presidential campaign, the priorities defined for 2005 should lead to an increase in the deficit, given the increases in military and security spending and substantial tax handouts for the rich.[3] The few measures planned to limit this deficit will lead to still greater austerity for the exploited, since it is planned to reduce spending that benefits the poor.[4]

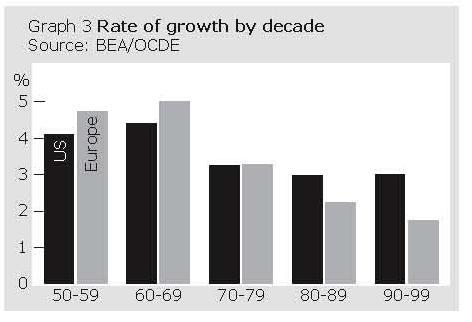

Moreover, we also need to put paid to the myth of a turnaround begun in the United States, since when we look at growth rates by decade following the decline which set in at the end of the 1960s, these remain stationary at around 3%, in other words at a lower level than during previous decades... and the two hundredths of a percentage point (!) increase for the period 1990-1999 over 1980-1989 can certainly not be considered as a change in tendency (graph n°3).

It is clear that the idea of a new phase of growth led by the United States is nothing but a myth maintained by bourgeois propaganda, refuted by the relative decline in European performance which, up until the 1980s, was catching up with the US.[5] The better health of the American economy comes not so much from its greater efficiency as a result of investment in the so-called "new economy", but from a thoroughly traditional and gigantic level of debt throughout the economy, which moreover has to be financed by the rest of the world. This is true both of the increase in the budget deficit and for the other fundamentals of the American economic recovery which we will examine below.

2) Debt fuels a recovery in consumer spending

One of the reasons for relatively higher growth in the United States is sustained consumer spending thanks to the following measures:

-

The spectacular decline in taxation which has maintained the spending of the rich, at the cost of further damage to the federal budget;

-

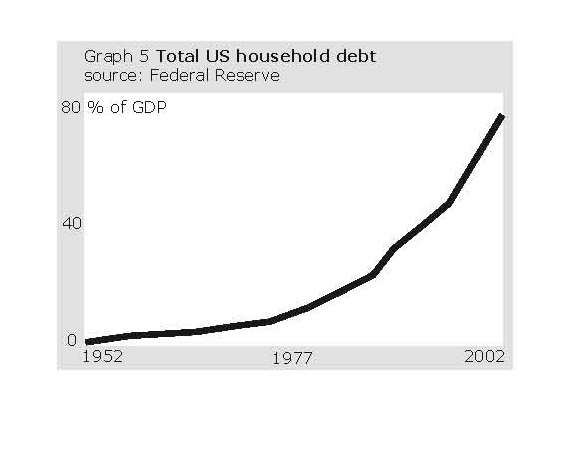

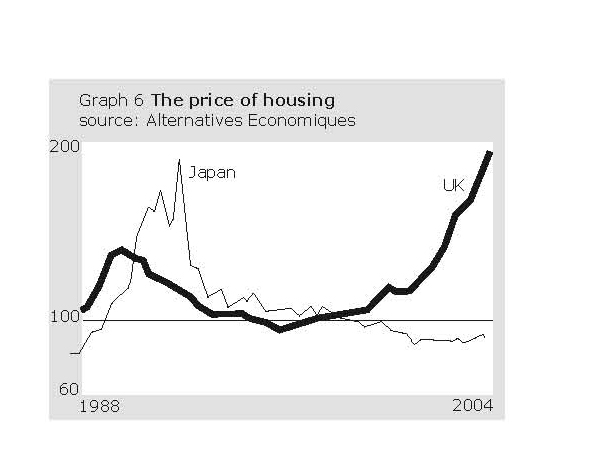

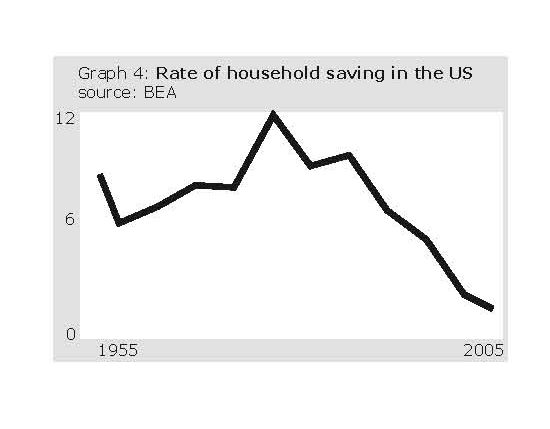

the decline both in interest rates, which have fallen from 6.5% at the beginning of 2001 to 1% in mid-2004, and in savings (graph n°4), which has had the effect of raising household debt to record levels (graph n°5) and unleashing a speculative bubble in the housing market (graph n°6).

Such dynamic consumer spending poses three problems: the growth in debt threatened by a crash in the housing market; a growing trade deficit (rising from 4.8% of US GDP in 2003 to 5.7% in 2004: more than 1% of world GDP) and an increasing inequality in incomes.[6] As graph n°4 shows, at the beginning of the 1980s household savings stood at between 8 and 9% of income after tax. Since then, this rate has declined to about 2%. And consumer spending is at the root of the United States' growing trade deficit. The US imports ever more goods and services than it sells abroad. Such a situation, where the United States increasingly lives on credit from the rest of the world, is only possible because the countries which receive an excess of dollars as a result of their trade surplus with the US are prepared to invest them on the American money markets rather than demand their conversion into other currencies. This mechanism has swollen gross US debt towards the rest of the world from 20% of GDP in 1980 to 90% in 2003, beating a 110 year-old record.[7] This debt relative to the rest of the world inevitably weakens the income of American capital which has to finance the interest. This raises the question of how long the American economy can go on sustaining such a level of debt.

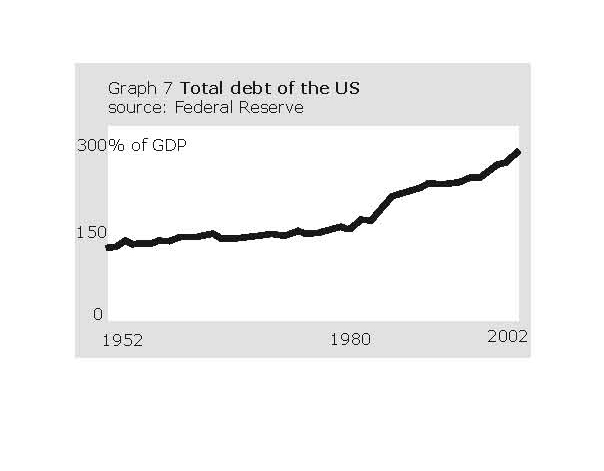

Moreover, American household debt is only part of an overall tendency within the American economy, whose indebtedness has risen to an enormous 300% of GDP in 2002 (graph n°7), which in reality stands at 360% if we add in gross federal debt. Concretely this means that in order to repay its total debt the American economy would have to work for nothing for three years. This demonstrates what we said previously, that the shorter recessions and longer recoveries since the beginning of the 1980s, which are supposedly the proof of a new tendency to growth based on a "third industrial revolution", are in fact meaningless because they are based not on a "healthy", but on an increasingly artificial growth.

|

|

| Graph 4: The rate of saving is the relationship between households’ total spending on goods and services (including housing) and their income after tax. This graph shows clearly that if United States growth rates were higher than those in Europe during the 1980s, this is not to do with the onset of the new phase of growth based on the so-called third industrial revolution tied to the “new economy”, but amongst other things to a constant fall in the rate of savings. The United States is spending its own savings and investments from the rest of the world. |

|

| Graph 5: Household debt has reached historically unprecedented levels. The growth in this debt has accelerated since the end of the 1960s, each percentage point of economic growth was based on a much faster increase in household debt. About three-quarters of this debt consists of mortgages: households borrow large sums on the basis of property values all the more readily in that interest rates on these loans are currently very low ("house values" here represents the share of mortgages in the total debt). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Flow of funds accounts of the US, 6 June 2002 |

|

| Graph 6: With the notable exceptions of Japan (still digesting its housing crash), and of Germany, the inflation in property prices is affecting the whole OECD. "L'état de l'économie 2005", in Alternatives Economiques n°64 |

|

| Graph 7: Total US debt increases slowly from 1952 until the early 1980s, then doubles in the space of 20 years. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Flow of funds accounts of the US, 6 June 2002 |

3) Falling interest rates allow a competitive devaluation of the dollar

Finally, the third factor in the American recovery is the progressive fall in interest rates from 6.5% at the beginning of 2001 to 1% in mid-2004, which has made it possible to support the domestic market and to maintain a policy of competitive devaluation of the dollar on international markets.

These low interest rates have made possible a growing level of debt (notably through cheaper mortgages) and have allowed consumer spending and the housing market to sustain economic activity despite the decline in employment during the recession. That is, the share of household spending in GDP which was around 62% from the 1950s to the 1980s, has increased to over 70% at the beginning of the 21st century.

Furthermore, the response to the US trade deficit has been a considerable decline in the dollar (about 40%) in relation to non-aligned currencies, essentially the euro (and in part the yen). In effect the US economy is growing on credit and at the expense of the rest of the world, since it is financed by foreign capital thanks to the dominant position of the United States. Any other country placed in such a situation would be obliged to raise its interest rates enough to attract foreign capital.

Economic dynamics since the end of the 1960s

As we have seen, the recovery that followed the 2001 recession is even more fragile than its predecessors. It is one in a series of recessions which themselves concretise the tendency to a constant decline in rates of growth, decade on decade, since the end of the 1960s. If we are to understand this tendency towards declining growth rates, and especially its irreversible nature, then we must return to its underlying causes.

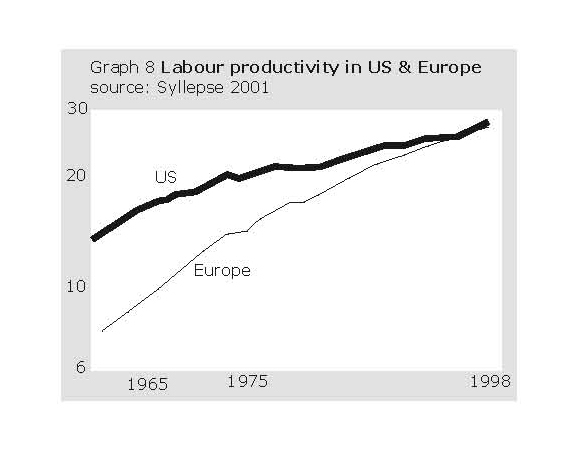

The exhaustion of the economic impetus after World War II, as the rebuilt European and Japanese economies began to flood the world with surplus products (relative to the solvent market), was followed by a slowdown in the growth of labour productivity, from the mid-1960s for the United States and the beginning of the 1970s for Europe (graph n°8).

Since the increase in productivity is the main endogenous factor that counters the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, a slowdown in the growth of productivity puts pressure on the rate of profit and therefore also on other fundamental variables of the capitalist economy: notably the rate of accumulation[8] and economic growth.[9] Graph n°9 shows clearly this fall in the rate of profit, beginning in the mid-1960s for the United States and the early 1970s for Europe, and continuing until 1981-82.

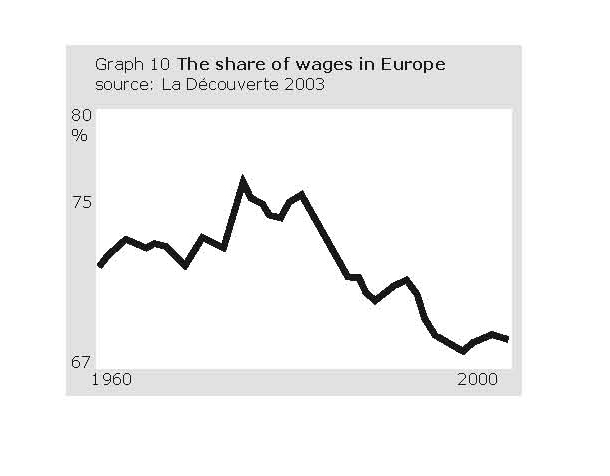

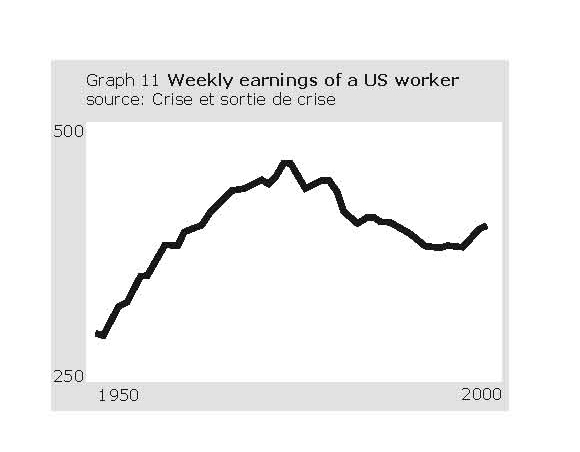

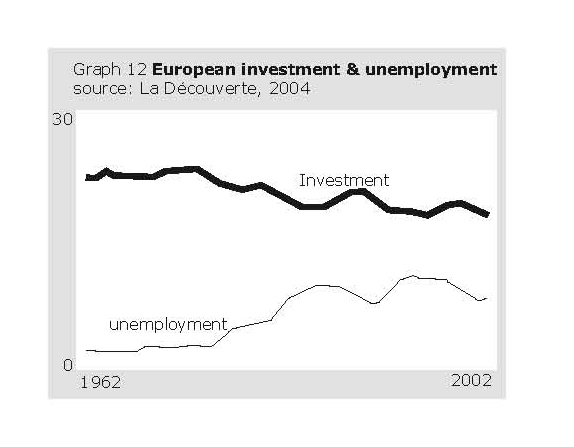

As this graph clearly shows, the fall in the rate of profit was reversed at the beginning of the 1980s and has remained firmly positive since then. The fundamental question is therefore to determine the cause of this reversal, since the rate of profit is a synthetic variable which is determined by numerous parameters that we can summarise under the following three headings: the rate of surplus value, the organic composition of capital, and labour productivity.[10] Essentially, capitalism can escape from the tendency of the rate of profit to fall either "upwards", by increasing labour productivity, or "downwards" through austerity at the expense of wage earners. The data presented in this article demonstrate clearly that the upturn in the rate of profit is not the result of new gains in productivity engendering a decrease or a slowdown in the growth of the organic composition of capital following a "third industrial revolution based on the microprocessor" (the so-called "new economy") but is due to direct and indirect wage austerity and the rise in unemployment (graph n°10,11,12).

Fundamental to the present situation is the fact that neither accumulation (graph n°12), nor productivity (graph n°8), nor growth (graph n°1) have kept up with the 25-year upturn in company profitability: on the contrary, all these fundamental variables have remained depressed. And yet historically, a rise in the rate of profit tends to draw with it the rate of accumulation and therefore of productivity and growth. We therefore need to pose the following fundamental question: why, despite the renewed health and upward orientation of the rate of profit, have capital accumulation and economic growth not followed?

The answer is given by Marx in his critique of political economy and especially in Capital where he puts forward his central thesis of the independence of production and the market: "the mere admission that the market must expand with production, is, on the other hand, again an admission of the possibility of over-production, for the market is limited externally in the geographical sense, the internal market is limited as compared with a market that is both internal and external, the latter in turn is limited as compared with the world market, which however is, in turn, limited at each moment of time, [though] in itself capable of expansion. The admission that the market must expand if there is to be no over-production, is therefore also an admission that there can be over-production. For it is then possible – since market and production are two independent factors – that the expansion of one does not correspond with the expansion of the other";[11] "The conditions of direct exploitation, and those of realising it, are not identical. They diverge not only in place and time, but also logically. The first are only limited by the productive power of society, the latter by the proportional relation of the various branches of production and the consumer power of society".[12] This means that production does not create its own market (inversely, by contrast, the saturation of the market necessarily has an impact on production, which is then voluntarily limited by the capitalists in an attempt to avoid total ruin). In other words, the fundamental reason behind capitalism's situation where company profitability has been re-established, but without productivity, investment, the rate of accumulation and therefore of growth, following, is to be sought in the inadequacy of solvent outlets.

This inadequacy of solvent outlets is also at the root of the so-called tendency towards the "financiarisation of the economy". If today's abundant profits are not reinvested this is not because of the low profitability of invested capital (if we were to follow the logic of those who explain the crisis solely through the tendency of the rate of profit to fall), but because of the lack of sufficient outlets. This is illustrated clearly by graph n°12 which shows that, despite the upturn in profits (the marginal rate measures the relationship of profit to added value) as a result of the increase in austerity, the rate of investment has continued to decline (and so therefore has economic growth) which explains the rise in unemployment and in non-reinvested profit which is then distributed in the form of financial revenue.[13] In the United States, financial revenue (interest and dividends, excluding capital gains) represented on average 10% of total household income between 1952 in 1979 but rose progressively between 1980 and 2003 to reach 17%.

Capitalism has only been able to control the effects of its contradictions by putting off the day of reckoning. It is not resolved them, it has only made them more explosive. The present crisis, as it demonstrates the impotence of the economic organisation and policies established since the 1930s and World War II, threatens to be both more serious and more indicative of the level reached by the contradictions of the system than all its predecessors.

|

| Graph 8: Labour productivity in the United States and Europe (Average for Germany, France and Great Britain). Labour productivity as calculated here concerns all companies. The United States is shown as a solid line and Europe as a thin line. Labour productivity is the quotient of production, corrected for inflation (constant 1990 dollars), by the number of hours worked: it is thus expressed in dollars per hour. The logarithmic scale allows us to visualise growth rates by the greater or lesser steepness of the curtain (the increasing shallowness of the curve thus indicates a diminution in the rate of growth of labour productivity). We can readily identify the break point in the mid-1960s for the United States and in the first half of the 1970s for Europe. Thus in Europe, labour productivity rose from seven dollars per hour in 1961 to 14 dollars per hour in 1975, whereas the rise from 14 to 28 dollars per hour in 1998 took 23 years.* The small fluctuations in the curve are the effects of upturns and downturns in activity. Because the graph uses purchasing power parity indexes, the absolute levels are comparable (whereas European labour productivity was half that of the United States in 1960, we can see that Europe has since then caught up). * during the 1950-60s the growth rates for labour productivity in the G6 (United States, Japan, Germany, France, Britain, Italy) were in the region of 6%. Since the 1980s they have turned around 2.5%, in other words they have fallen by more than half. |

|

| Graph 9: The rate of profit is calculated here for the whole private economy, as the ratio between a broad measure of profit (production less the total labour cost) and the stock of fixed capital (net of amortization). Taxes (on profits), interest payments, and dividends, for profits. G Dumesnil and D Lévy, published in La finance mondialisée, editor F Chesnais, ed. La Découverte, 2004, pp71-98 |

|

| Graph 10: Every year, society produces a certain added value in the form of a given volume of goods and services: the gross domestic product (GDP). For companies, this added value is divided between profit and wages (wages paid directly to the workers, and indirect wages in the form of social security payments). The graph shows the evolution of wages as a percentage of GDP. We can see clearly that the rate has fallen over the last 20 years. M Husson, Les casseurs de l'Etat social, ed. La Découverte, 2003 |

|

| Graph 11: Multiplied by 1.7 between the end of the war and 1970, weekly industrial wages (in 1990 dollars) have fallen to the level of the late 1950s. G Dumesnil and D Lévy, Crise et sortie de crise |

|

| Graph 12: Following the application of austerity programmes, the decline in labour costs has increased the competitivityof production costs, which however have not been wholly reflected in a fall in prices, thus increasing company profit margins. The recovery in profits has not, however, led to an increase in investment, which has continued to decline. It it this phenomenon which explains the so-called "financiarisation of the economy": instead of being reinvested, the increased profit is distributed in the form of finance revenue. But if the stagnation of wage costs has fed finance revenue rather than investment, this is not because "bad finance capital" is a parasite on "good productive capital", as the leftists and anti-globalists would have us believe, but because the intrinsic nature of capitalist social relations limits the development of solvent demand. The source of the crisis lies in the very foundations of the capitalist system, not in a "bad" capitalism chasing out the "good" and which needs to be disciplined by more regulations and "democratic control". M Husson, op. cit. |

Another analysis of the crisis by Battaglia Comunista

We have seen above that the bourgeoisie's explanations are not worth a penny and are nothing other than a pure mystification to hide its system's historic bankruptcy. Unfortunately, some revolutionary political groups have also adopted these conceptions - voluntarily or not - either in their official or in their leftist and anti-globalist versions. We will look here more particularly at the analyses produced by Battaglia Comunista.[14]

We should start by pointing out that everything we have seen above constitutes a clear refutation of the foundations of the "analysis" of the crisis in terms of a "third industrial revolution" and of the "parasitic financiarisation" of capitalism and the "recomposition of the working-class" which Battaglia seems to have taken directly from the bourgeoisie’s propaganda manuals for the former, and from the leftists and anti-globalists for the latter.[15] Battaglia Comunista is utterly convinced that capitalism is in the midst of a "third industrial revolution marked by the microprocessor" and is undergoing a "restructuring of its productive apparatus" and a "resulting demolition of the previous composition of the class", thus making possible "a long resistance to the crisis of the cycle of accumulation".[16] At this point we should make a number of comments:

1) First of all, if capitalism really were in the midst of a "industrial revolution" as Battaglia Comunista claims, then we should at least - by definition - be seeing an upturn in labour productivity. And indeed this is what Battaglia thinks is happening, since they declare forthrightly and without any empirical verification that "the profound restructuring of the productive apparatus has brought with it a dizzying increase in productivity", an analysis repeated in the latest issue of their theoretical review: "... an industrial revolution, in other words of the processes of production, has always had the effect of increasing labour productivity...".[17] But, as we have seen above, the reality in terms of labour productivity is the opposite to the bluff maintained by bourgeois propaganda and swallowed whole by Battaglia Comunista. This organisation seems to be unaware that the growth in labour productivity began to decline more than 35 years ago and that it has more or less stagnated since the 1980s (graph n°8)![18]

2) We have seen that, for Battaglia, "the third industrial revolution based on the microprocessor" is so powerful that it has "generated dizzying gains in productivity" making it possible to "reduce the increase in the growth of organic composition". But even a cursory examination of the real dynamic of the rate of profit demonstrates that the recession of 2000-2001 in the United States was preceded in 1997 by a temporary downturn[19] (graph n°9), notably because the famous "new economy" led to an increase in capital, in other words to a rise in organic composition and not to a decline as Battaglia pretends.[20] The new technologies have certainly made possible some gains in productivity[21] but these have been insufficient to compensate for the cost of investment despite the decline in their relative price, which has in the end weighed on the organic composition of capital and has since 1997 led to a downturn in US profit rates. This point is important since it demolishes any illusions in capitalism's ability to free itself from its fundamental laws. The new technologies are not a magic wand which would make it possible to accumulate capital for free.

3) Moreover, if labour productivity really were undergoing a "dizzying increase" then, for anyone who knows Marx, the rate of profit would be rising. Indeed this is what Battaglia Comunista suggests, though without saying so explicitly, when they declare that "... unlike previous industrial revolutions (...) the one based on the microprocessor (...) has also reduced the cost of innovation, in reality the cost of constant capital, thus diminishing the increase in the organic composition of capital".[22] As we can see, Battaglia does not deduce from this that there has been an increase in the rate of profit. Have they forgotten that "if productivity rises faster than the composition of capital, then the rate of profit does not decline, on the contrary it will rise", as its fraternal organisation, the CWO, wrote some time ago (in Revolutionary Perspectives n°16 old series, "Wars and accumulation", pp 15-17)? Battaglia prefers to talk discreetly of "the diminution in the increase of the growth of organic composition" as a result of "the dizzying growth in productivity following the industrial revolution based on the microprocessor" rather than of a rise in the rate of profit. Why such contortions, why try to hide economic reality from their readers? Quite simply because to recognise such an implication of their own observation (whether right or wrong) of the evolution of labour productivity would contradict their eternal dogma as to the unique source of the crisis: the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Battaglia Comunista, which never misses an occasion to reassert its eternal credo that the rate of profit is always pointed downwards, is so preoccupied with "understanding the world" outside the supposedly abstract schemas of the ICC that they seem not to have realised that the rate of profit has been resolutely pointed upwards for a quarter-century (graph n°9) and not downwards as they continue to claim! This 28-year blindness has only one explanation: how else could they continue to talk about the crisis of capitalism without calling into question their dogma explaining crises solely by the tendency of the rate of profit fall, when in fact the latter has been oriented upwards since the beginning of the 1980s?

4) Capitalism survives not by rising, thanks to "an industrial revolution" and "dizzying new gains in productivity" as Battaglia Comunista claims, but by decline, through a drastic reduction in the mass of wages dragging the world into poverty and, at the same time, reducing in part its own outlets. Anyone who analyses attentively the driving forces behind this quarter-century rise in the rate of profit will see that it springs not from "dizzying rises in productivity" and "the diminution in the increase in organic composition" but in an unprecedented austerity at the expense of the working-class as we have seen above (graphs n°10 to 12).

Capitalism's present configuration thus utterly refutes all those who make the mechanism of the "tendency of the rate of profit fall" the sole explanation of the economic crisis, given that for 25 years the rate of profit has been rising. If the crisis continues today despite renewed company profitability, it is because companies no longer expand production as they once did, given the limitation and therefore the inadequacy of their outlets. This reveals itself in anaemic investment and therefore weak growth. Battaglia Comunista is incapable of understanding this because they have not understood Marx's fundamental thesis as to the independence between production and the market (see above), and have traded it in for an absurd idea which makes the development or the limitation of the market depend entirely on the sole dynamic upwards or downwards of the rate of profit.[23]

Given these repeated blunders, which reveal their incomprehension of the most elementary notions, we can only repeat our advice to Battaglia Comunista: revise your ABC of marxist economic concepts before trying to play teacher and excommunicators with the ICC. In fact, Battaglia's recent decision to refuse any reply to our organisation has come just in time to hide their increasingly obvious inability to confront our arguments politically.[24]

Contrary to the "abstract schemas" of the ICC, which are supposedly "outside historical materialism", Battaglia tells us that they have "... studied the administration of the crisis by the West both in all its financial aspects and on the terrain of the restructuring engendered by the wave of the microprocessor revolution".[25] However, we have seen that Battaglia's "study" is nothing other than an insipid copy of leftist and anti-globalist theories about the "parasitism of financial rent".[26] Their copy is not only insipid it is moreover totally incoherent and contradictory since they have failed to master the marxist economic concepts that they claim to work with. And while they do not understand these concepts, they do not hesitate to transform them as they please, as with the marxist thesis on the independence of production and the market which, in the secret world of Battaglia's dialectic, is transformed into a law of the strict dependence between "... the economic cycle and the process of valorisation which make the market 'solvent' or 'insolvent'" (op cit). We expect something better than a string of nonsense from critical contributions that claim to re-establish marxism against the so-called idealist vision of the ICC.

Conclusion

On all major questions of economic analysis Battaglia Comunista fall systematically into the trap of appearances in themselves, instead of trying to understand the essence of things from the standpoint of a marxist analytical framework. We have seen that Battaglia Comunista has swallowed all the bourgeoisie's talk about the existence of a third industrial revolution merely on the basis of the empirical appearance of a few technological novelties in the microelectronics and information technology sectors, however spectacular these may be,[27] and as a result have arrived at the purely speculative deduction that there are "dizzying gains in productivity" and "a reduction in the cost of constant capital thus diminishing the increase in organic composition". On the contrary, a rigorous marxist analysis of the fundamental variables that determine the dynamic of the capitalist economy (the market, the rate of profit, the rate of surplus value, the organic composition of capital, labour productivity, etc.) allow us to understand not only that this is in large part of media bluff, but in valorisation the reality is the opposite of the bourgeoisie's claims, echoed by Battaglia Comunista.

Understanding the crisis is not an academic exercise but essentially a militant activity. As Engels said "The task of economic science is rather to show that the social abuses which have recently been developing are necessary consequences of the existing mode of production, but at the same time also indications of its approaching dissolution, and to reveal within the already dissolving economic form of motion, the elements of the future new organisation of production and exchange which will put an end to those abuses." And this becomes possible with real clarity "Only when the mode of production in question has already described a good part of its descending curve, when it has half outlived its day, when the conditions of its existence have to a large extent disappeared, and its successor is already knocking at the door".[28] This is the meaning and the aim of revolutionary work at the level of economic analysis. It allows us to understand the context for the evolution of the balance of class forces and certain of its determining factors, since capitalism's entry into its decadent phase provides the material and potentially the subjective conditions for the proletariat to undertake the insurrection. This is what the ICC has always tried to demonstrate in its analyses. Battaglia Comunista, by abandoning the concept of decadence[29] and by adopting an academic and mono-causal vision of the crisis has begun to forget how to do this. Their "economic science" no longer service to demonstrate the " social abuses" of capitalism or the " indications of its approaching dissolution" as the founders of marxism urged us to do, but rather to fob us off with leftist and anti-globalist prose about "capitalism's capacity for survival" through the "financiarisation of the system", the "recomposition of the proletariat", and to cap it all "the fundamental transformation of capitalism" thanks to the so-called "third industrial revolution based on the microprocessor", new technologies, etc.

Today finds Battaglia Comunista completely disorientated and no longer really knowing what to defend in front of the working-class: is the capitalist mode of production in decadence or not?[30] Is it the capitalist mode of production or the capitalist social formation which is in decadence?[31] Has capitalism been "in crisis for more than 30 years"[32] or is it going through "a third industrial revolution based on the microprocessor" leading to "a dizzying increase in productivity"?[33] Is the rate of profit rising as the statistical data demonstrates or is it still falling as Battaglia invariably repeats, to the point where capitalism is obliged to proliferate war around the world in order to avoid bankruptcy?[34] Is capitalism today in a dead-end or does it still have before it "a long capacity for resistance" thanks to "a third industrial revolution",[35] or does it even have its own "solution" to the crisis thanks to war: "In the imperialist era global war is capital's way of 'controlling', of temporarily resolving, its contradictions" (IBRP platform)? These questions are fundamental if we are to orientate ourselves in the present situation. On these questions Battaglia Comunista can do no more than go around in circles: they are incapable of offering a clear response to the proletariat.

CC

1 Unfortunately, we do not have space here to deal with cases of China and India. We will return to them in a later issue of this Review.

2 As institutions at the level of the blocs, these organisations are (or were) fundamentally the expression of a balance of forces based on the economic and above all the military power of the bloc's leading power, respectively the United States and the USSR.

3 70% of tax reductions benefit households whose incomes are in the highest 20%.

4 Food stamps for the poorest families will be reduced, depriving 300,000 people of this aid; budget provision for aid to poor children is frozen for five years, and medical coverage for the poor is to be cut.

5 From 45% of American growth in 1950, the combined economies of Germany, France, and Japan represented up to 80% in the 1970s, only to fall to 70% in 2000.

6 On the eve of World War II, the richest 1% of US households had about 16% of total national income. At the end of the war, this fell to 8%, where it remained until the beginning of the 1980s. Since then, it has risen again to the pre-war level (T Piketty, E Saez, 2003, "Income inequality in the United States, 1913-1998", in The quarterly journal of economics, vol CXVIII, n°1, pp 1-39).

7 Net debt, which takes account of US income from foreign investment, is equally significant, since it has moved from a negative position in 1985 (ie US income from foreign investment was greater than the income derived by other countries from their investment in America) to a positive one, to reach 40% of GDP in 2003 (ie the income derived by other countries from their investment in the US is now substantially greater than that derived by the US from its investments abroad).

8 The rate of capital accumulation is the relationship between investment in new fixed capital and the existing stock.

9 See also our article in International Review n°115: " The crisis reveals the historic bankruptcy of capitalist productive relations".

10 These three parameters can themselves be broken down and are determined by the evolution of working hours, real wages, the degree of mechanisation, the value of the means of production and consumption, and the productivity of capital.

11 Marx, Grundrisse.

12 Marx, Capital, Part III: "The law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall", Chapter XV "Exposition of the internal contradictions of the law". https://www.marxists.org

13 Reality has thus disproved a hundred-fold the theory – still repeated ad nauseam today – of Germany's Social Democratic chancellor Helmut Schmidt: "The profits of today are tomorrow's investments and jobs after tomorrow". The profits are there, but not the investment, or the jobs!

14 We will return to other analyses that are current in the little academic and parasitic milieu, in the framework of our articles on the crisis and of our series on "The theory of decadence at the heart of historical materialism".

15 "The profits from speculation are so large that they are attractive not only to 'classical' companies but also to many other, such as insurance companies or pension funds of which Enron is an excellent example (…) Speculation represents the complementary, not to say the main means for the bourgeoisie to appropriate surplus value (…) A rule has been imposed, fixing 15% as the minimum target profit for capital invested in companies (…) The accumulation of financial and speculative profit feeds a process of deindustrialisation that brings unemployment and poverty in its wake all over the planet" (the IBRP in Bilan et Perspectives n°4, pp6-7).

16 "The long resistance of Western capital to the crisis of the cycle of accumulation (or to the actualisation of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall) has up to now avoided the vertical collapse that hit the state capitalism of the soviet empire. This resistance has been made possible by four fundamental factors: 1) the sophistication of international financial controls; 2) a profound restructuring of its productive apparatus which has brought about a dizzying rise in productivity (…); 3) the resulting demolition of the previous composition of the class, with the disappearance of outdated tasks and roles, and the appearance of new tasks, new roles, and new types of proletarian (…) The restructuring of the productive apparatus has come at the same time as what we can define as capitalism's third industrial revolution (…) The third industrial revolution is marked by the microprocessor" (Prometeo, n°8, December 2003, "Proposed IBRP theses on the working class in the present period and its perspectives" – our translation).

17 Prometeo, n°10, December 2004, "Decadence and decomposition, the products of confusion".

18 The slightly faster increase in productivity in the United States during the second half of the 1990s (which made possible an acceleration in the rate of accumulation supporting American growth) in no way contradicts its massive decline since the end of the 1960s (graph n°8). We will return to this point in greater depth in future articles. We should point out, however, that this phenomenon is at the basis of a very low level of job creation compared to previous recoveries; that the recovery itself is half-hearted; that there is some doubt as to whether these gains in productivity will prove long-lasting, and that any hope of them spreading to other leading economies is all but non-existent. In the USA, moreover, a computer is accounted as capital, whereas in Europe it is accounted as intermediate consumption. As a result, US statistics tend to overestimate GDP (and therefore productivity) compared to European ones, since they include depreciation of capital. When we correct for this bias, and for hours worked, then we can see that the difference in productivity gains between Europe and the US during 1996-2001is very slight (1.4% against 1.8% respectively), and that these gains remain very low compared to the 5-6% gains in productivity during the 1950s and 60s.

19 This turnaround was a temporary one, since the rate of profit began rising again in mid-2001 and recovered its 1997 level at the end of 2003. The recovery was achieved thanks to a strict limitation on hiring, to the point were it was described as a "jobless recovery", but also by classic measures for raising surplus value, such as an increase in hours worked and wage freezes made all the easier by the weak labour market. The brake on the rate of accumulation also made it possible to lighten the load of capital's organic composition, which weighs on its profitability.

20 For a serious analysis of this process, see P Artus' article "Karl Marx is back" published in Flash N°2002-04, as well as his book La nouvelle économie (Repères – La Découverte n°303), an extract of which we reprint at the bottom of this article.

21 Though we should add that "many studies have shown that without the introduction of flexible working practices, the 'new economy' would not have improved companies' efficiency" (P Artus, op cit).

22 Prometeo, n°10, December 2004, "Decadence and decomposition, the products of confusion".

23 "[for the ICC] this contradiction between the production of surplus value and its realisation, appears as an overproduction of goods, and thus asa cause of the saturation of markets, which in its turn interferes with the system of production, so making the system as a whole incapable of counteracting the fall in the rate of profit. In Fact, the process is the reverse (…) It is the economic cycle and the process of valorisation which makes the market 'solvent' or 'insolvent'. One can only explain the ‘crisis’ of the market from the starting point of the contradictory laws which regulate the process of accumulation. (presentation by Battaglia to the first conference of groups of the communist left in Texts and Proceedings of the International Conference. P.24).

24 "we have declared that we are no longer interested in any kind of debate/confrontation with the ICC (…) If these are – and they are – the ICC's theoretical foundations, then the reason that we have decided not to waste any more time, paper, or ink discussing or even in polemic with them, should be clear" (Prometeo, n°10, op cit), and "We are tired of discussing about nothing when we have work to do trying to understand what is going on in the world" ("Reply to the stupid accusations of an organisation in the process of disintegration", once published on the IBRP web site).

25 Prometeo, n°10, op cit

26 See also our article "The Crisis Reveals the Historic Bankruptcy of Capitalist Productive Relations", in International Review n°115.

27 For more details on the bluff of the so-called third industrial revolution, see our article in International Review n°115. We reproduce a few extracts here: "The 'technological revolution' only exists in the campaigns of the ruling class and in the heads of those who swallow them. More seriously, the empirical observation that the increase in productivity (progress in technology and the organisation of labour) has been constantly slowing down since the 1960s, contradicts the media image of increasing technical change, a new industrial revolution supposedly borne on a wave of computing, telecommunications, the Internet, and multimedia. How are we to explain the strength of this mystification, which turns reality upside down in the heads of every one of us?

Firstly, we should remember that the increases in productivity were much more spectacular immediately following World War II than those which are presented today as a 'new economy' (…) since the 'Golden 60s', the increase in productivity has fallen continuously (…) Furthermore, there is a constantly encouraged confusion between the appearance of new commodities for consumption and the progress of productivity. The tide of innovation, and the proliferation of the most extraordinary new consumer products (DVD, GSM phones, the Internet, etc.) is not the same thing as an increase in productivity. An increase in productivity means the ability to reduce the resources needed to produce a commodity or a service. The term 'technical progress' should always be understood as progress in the 'techniques of production and/or organisation', strictly from the standpoint of the ability to economise the resources used in the production of a commodity or the supply of a service. No matter how extraordinary, the progress of digital technology is not expressed in significant increases in productivity within the productive process. This is the bluff of the 'new economy'".

28 Anti-Dühring, "Subject matter and method".

29 See our series on "The theory of decadence at the heart of historical materialism", begun in International Review n°118.

30 This is why Battaglia Comunista has announced, in Prometeo n°8, a major study on the question of decadence: "…the aim of our research will be to verify whether capitalism has exhausted the thrust of its development of the productive forces, and if this is true then when, to what extent, and above all why" ("For a definition of the concept of decadence", December 2003).

31 "We are thus certainly confronted with a form of increase of the barbarity of the social formation, of its social, political, and civil relationships, and indeed – since the 1990s – in a return to the past in the relationship between capital and labour (with the return to the search for absolute as well as relative surplus value, in the purest Manchester style), but this 'decadence' does not concern the capitalist mode of production but its social formation in the present cycle of capitalist accumulation, in crisis for more than 30 years!" (Prometeo n°10, op cit). We will return, in a future article, to this theoretical fantasy of a capitalist "social formation" being decadent independently of the capitalist "mode of production"! We will simply point out here that in the words of Engels quoted above, as in all his and Marx's works (see our article in n°118 of this Review, the latter always talk of the decadence of the mode of production, never of the social formation.

32 "…the present cycle of capitalist accumulation, in crisis for more than 30 years!" (see note 31).

33 Prometeo n°8, op cit.

34 "According to the marxist critique of political economy, there exists a very close relationship between the crisis of capital's cycle of accumulation and war, due to the fact that at a certain point in any cycle of accumulation, because of the tendency of the average rate of profit to fall, there appears a veritable over-accumulation of capital, such that destruction through war becomes necessary for a new cycle of accumulation to begin" (Prometeo ,°8, December 2003, "La guerra mancata").

35 "The long resistance of Western capital to the crisis of the cycle of accumulation (or to the actualisation of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall) has up to now avoided the vertical collapse…" (see above, note 16).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace