Submitted by ICConline on

We can hardly get away this year from a whole variety of historical experts telling us how the First World War actually got started and what it was really about. But very few of them – not least the left wing ideologues who are full of criticism about the sordid ambitions of the contending royal dynasties and ruling classes of the day –tell us that the war could not be unleashed until the ruling classes were confident that plunging Europe into a bloodbath would not in turn unleash the revolution. The rulers could only go to war when it was clear that the ‘representative’ of the working class, the Socialist parties grouped in the Second International, and the trade unions, far from opposing war, would become its most crucial recruiting sergeants. This article begins the task of reminding us how this monstrous betrayal could take place.

When war broke out in August 1914, it hardly came as a surprise for the populations of Europe, especially the workers. For years, ever since the turn of the century, crisis had followed on crisis: the Moroccan crises of 1905 and 1911, the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, just to name the most serious of them. These crises saw the great powers going head to head, all of them engaged in a frantic arms race: Germany had begun a huge campaign of naval construction, which Britain had inevitably to answer. France had introduced three-year military service, and huge French loans were financing the modernisation of Russia’s railways, designed to transport troops to its frontier with Germany, as well as that of Serbia’s army. Russia, following the debacle of its war with Japan in 1905, had launched a thoroughgoing reform of its armed forces. Contrary to what all today’s propaganda about its origins tells us, World War I was consciously prepared and above all desired by all the ruling classes of all the great powers.

So it was not a surprise – but for the working class, it came as a terrible shock. Twice, at Stuttgart in 1907 and at Basel in 1912, the Socialist parties of the 2nd International had solemnly committed themselves to defend the principles of internationalism, to refuse the enrolment of the workers in war, and to resist it by every means possible. The Stuttgart Congress adopted a resolution, with an amendment proposed by its left wing – Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg: “In case war should break out [it is the Socialist parties’] duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilize the economic and political crisis created by the war to rouse the masses and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule”. Jean Jaurès, the giant of French socialism, declared to the same Congress that “Parliamentary action is no longer enough in any domain... Our adversaries are horrified by the incalculable strength of the proletariat. We have proudly proclaimed the bankruptcy of the bourgeoisie. Let us not allow the bourgeoisie to speak of the bankruptcy of the International”. In July 1914, Jaurès had a statement adopted by the French Socialist Party’s Paris Congress, to the effect that: “Of all the means used to prevent and stop a war, the Congress considers as particularly effective the general strike, organised internationally in the countries concerned, as well as the most energetic action and agitation”.

And yet, in August 1914 the International collapsed, or more exactly it disintegrated as all its constituent parties (with a few honourable exceptions, like the Russians and the Serbs) betrayed its founding principle of proletarian internationalism, in the name of “danger to the nation” and the defence of “culture”. And needless to say, every ruling class, as it prepared to slaughter human lives by the millions, presented itself as the high point of civilisation and culture – its opponents of course, being nothing more than bloodthirsty brutes guilty of the worst atrocities...

How could such a disaster happen? How could those who, only a few months or even a few days previously, had threatened the ruling class with the consequences of war for its own rule, now turn round and join without protest in national unity with the class enemy – the Burgfriedenpolitik, as the Germans called it?

Of all the parties in the International, it is the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, the Germany Social-Democratic Party (SPD) which bears the heaviest responsibility. Not that the others were guiltless, especially not the French Socialist Party. But the German party was the flower of the International, the jewel in the crown of the proletariat. With more than a million members and more than 90 regular publications, the SPD was far and away the strongest and best organised party of the International. On the intellectual and theoretical level, it was the reference for the whole workers’ movement: the articles published in its theoretical review Neue Zeit (New Times) set the tone for marxist theory and Karl Kautsky, Neue Zeit’s editor, was sometimes considered as the “pope of marxism” As Rosa Luxemburg wrote: “By means of countless sacrifices and tireless attention to detail, [German Social Democracy] have built the strongest organization, the one most worthy of emulation; they created the biggest press, called the most effective means of education and enlightenment into being, gathered the most powerful masses of voters and attained the greatest number of parliamentary mandates. German Social Democracy was considered the purest embodiment of Marxist socialism. German Social Democracy had and claimed a special place in the Second International – as its teacher and leader” (Junius Pamphlet).

The SPD was the model that all the others sought to emulate, even the Bolsheviks in Russia. “In the Second International the German ‘decisive force’ played the determining role. At the [international] congresses, in the meetings of the International Socialist Bureau, all awaited the opinion of the Germans. Especially in the questions of the struggle against militarism and war, German Social Democracy always took the lead. ‘For us Germans that is unacceptable’ regularly sufficed to decide the orientation of the Second International, which blindly bestowed its confidence upon the admired leadership of the mighty German Social Democracy: the pride of every socialist and the terror of the ruling classes everywhere” (Junius Pamphlet). It was therefore down to the German Party to translate the commitments made at Stuttgart into action and to launch the resistance to war.

And yet, on that fateful day of 4th August 1914, the SPD joined the bourgeois parties in the Reichstag to vote for war credits. Overnight, the working class in all the belligerent countries found itself disarmed and disorganised, because its political parties and its unions had gone over to the enemy class and henceforth would be the most energetic organisers not of resistance to war, but on the contrary of society’s militarisation for war.

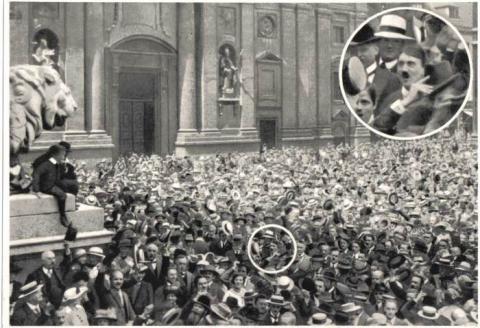

Today, legend would have it that the workers were swept away like the rest of the population by an immense wave of patriotism, and the media love to show us film of the soldiers seen off to the front by a cheering population. Like many legends, this one has little to do with the truth. Yes there were demonstrations of nationalist hysteria, but these were mostly the actions of the petty bourgeoisie, of young students drunk with nationalism. In France and in Germany, the workers demonstrated in their hundreds of thousands against the war during July 1914: they were reduced to impotence by the treason of their organisations.

In reality of course, the SPD’s betrayal did not happen overnight. The SPD’s electoral power hid a political impotence, worse, it was precisely the SPD’s electoral success and the power of the union organisations that reduced the SPD to impotence as a revolutionary party. The long period of economic prosperity and relative political freedom that followed the abandonment of Germany’s anti-socialist laws in 1891 and the legalisation of the socialist parties, ended up convincing the union and parliamentary leadership that capitalism had entered a new phase, and that it had overcome its inner contradictions to the point where socialism could be achieved, not through a revolutionary uprising of the masses, but through a gradual process of parliamentary reform. Winning elections thus became the main aim of the SPD’s political activity, and as a result the parliamentary group became increasingly preponderant within the Party. The problem was that despite the workers’ meetings and demonstrations during electoral campaigns, the working class did not take part in elections as a class, but as isolated individuals in the company of other individuals belonging to other classes – whose prejudices had to be pandered to. Thus, during the 1907 elections, the Kaiser’s Imperial government conducted a campaign in favour of an aggressive colonial policy and the SPD – which up to then had always opposed military adventures – suffered considerable losses in the number of seats in the Reichstag. The SPD leadership, and especially the parliamentary group, concluded that it would not do to confront patriotic sensitivities too openly. As a result, the SPD resisted every attempt within the 2nd International (notably at the Copenhagen Congress in 1910) to discuss precise steps to be taken against war, should it break out.

Moving within the bourgeois world, the SPD leadership and bureaucracy increasingly took on its colouring. The revolutionary ardour which had allowed their predecessors to oppose the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 faded in the leadership; worse still it came to be seen as dangerous because it might expose the Party to repression. By 1914, behind its imposing façade, the SPD had become “a radical party like the others”. The Party adopted the standpoint of its own bourgeoisie and voted the war credits: only a small minority stood firm to resist the debacle. This hunted, persecuted, imprisoned minority laid the foundations of the Spartakus group which was to take the lead of the 1919 German revolution, and found the German section of the new International, the KPD.

It is almost a banality to say that we are still living today in the shadow of the 1914-18 war. It represents the moment when capitalism encircled and dominated the entire planet, integrating the whole of humanity into a single world market – a world market which was then and still is today the object of all the great powers’ covetous desires. Since 1914, imperialism and militarism have dominated production, war has become world- wide and permanent.

It was not inevitable that World War I should develop as it did. Had the International remained true to its commitments, it might not have been able to prevent the outbreak of war but it would have been able to encourage the inevitable workers’ resistance, give it a political and revolutionary direction, and so open the way, for the first time in history, to the possibility of creating a world- wide human community, without classes or exploitation, so bringing an end to the misery and the atrocities that a decadent and imperialist capitalism has ever since inflicted on humanity. This is no mere pious wish. On the contrary, the Russian revolution is the proof that the revolution was not, and is not only necessary, but possible. It was the masses’ immense assault on the heavens, this great upsurge of the proletariat, that made the international ruling classes tremble and forced them to bring the war to an end. War or revolution, socialism or barbarism, 1914 or 1917...: humanity’s only alternative could not be clearer.

Sceptics will say that the Russian revolution remained isolated and finally went down to defeat by the Stalinist counter-revolution, and that 1914-18 was followed by 1939-45. This is perfectly true. But if we are to avoid drawing false conclusions, then we need to understand the whys and wherefores rather than swallow whole the endless official propaganda. In 1917, the international revolutionary wave began in a context where the divisions of war were profoundly anchored, and the ruling class exploited these divisions to overcome the working class. Disoriented and confused, the proletariat failed to unite in one vast international movement. The workers remained divided between “victors” and “vanquished”. The heroic revolutionary uprisings, like that of 1919 in Germany, were drowned in blood, largely thanks to the traitorous workers’ party, the Social Democracy. This isolation made it possible for international reaction to defeat the Russian revolution and prepare the ground for a second world-wide butchery, confirming once again the historic alternative that is still before us: “socialism or barbarism”!

Jens

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace