Submitted by International Review on

In the first part of his article, we saw that, contrary to what is often asserted, it is not the mechanism of the tendency towards the fall in the rate of profit which is at the heart of Marx's analysis of the economic contradictions of the capitalist system, but the fetter that the wage labour relationship places upon the ultimate demand of society: "The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses, in the face of the drive of capitalist production to develop the productive forces as if only the absolute consumption capacity of society set a limit to them" (Marx, Capital, Vol 3, Chapter 30: "Money capital and real capital: 1", p615). [1] This is the consequence of the subordination of the world to the dictatorship of wage labour, which enables the bourgeoisie to appropriate a maximum of surplus labour. But as Marx explains, the frenetic production of commodities engendered by the exploitation of the workers gives rise to a piling up of products which grows more rapidly than the solvent demand of society as a whole: "When considering the production process we saw that the whole aim of capitalist production is appropriation of the greatest possible amount of surplus-labour ... in short, large-scale production, i.e., mass production. It is thus in the nature of capitalist production, to produce without regard to the limits of the market." [2] This contradiction periodically provokes a phenomenon hitherto unknown in the whole history of humanity: the crises of overproduction: "an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity - the epidemic of over-production."[3] "The immense but intermittent elasticity of the factory system, combined with its dependency on the universal market, necessarily gives birth to feverish production, followed by a glut on the markets, whose contraction then leads to paralysis. The life of industry is thus transformed into a series of periods of average activity, prosperity, overproduction, crisis, and stagnation".[4]

More precisely, Marx situates this contradiction between the tendency towards the frenetic development of the productive forces and the limitations to the growth of society's ultimate consuming power given the relative impoverishment of the wage labourers: "To each capitalist, the total mass of all workers, with the exception of his own workers, appear not as workers, but as consumers, possessors of exchange values (wages), money, which they exchange for his commodity."[5] Now, following Marx, "the consumer power of society is not determined either by the absolute productive power, or by the absolute consumer power, but by the consumer power based on antagonistic conditions of distribution,[6] which reduce the consumption of the bulk of society to a minimum varying within more or less narrow limits."[7] It thus follows that "Over-production is specifically conditioned by the general law of the production of capital: to produce to the limit set by the productive forces, that is to say, to exploit the maximum amount of labour with the given amount of capital, without any consideration for the actual limits of the market or the needs backed by the ability to pay"[8] This is the heart of the marxist analysis of the economic contradictions of capitalism: the system must ceaselessly increase production while consumption cannot, within the present class structure, follow an identical rhythm.

In the first part of our article, we also saw that, in its internal mechanism, the tendency for the rate of profit to fall could well run alongside the emergence of crises of overproduction. Indeed, this idea appears in many places in Marx's work, for example in the chapter of Capital on the internal contradictions of the law of the falling rate of profit: "Over-production of capital is never anything more than overproduction of means of production (...) a fall in the intensity of exploitation below a certain point, however, calls forth disturbances, and stoppages in the capitalist production process, crises, and destruction of capital."[9] However, for Marx it was neither the exclusive nor even the main cause of the contradictions of capitalism. Furthermore, in the Preface to the 1886 English edition of Book 1 of Capital, when Engels is summarising Marx's conception, he does not refer to the tendency for the rate of profit to fall but to the contradiction which Marx constantly underlined between "the absolute development of the productive forces" and "the limitations on the growth of society's ultimate consuming power": "While the productive power increases in a geometric, the extension of markets proceeds at best in an arithmetic ratio. The decennial cycle of stagnation, prosperity, over-production and crisis, ever recurrent from 1825 to 1867, seems indeed to have run its course; but only to land us in the slough of despond of a permanent and chronic depression".[10]

Thus, as we will show, and as will be clear to anyone who approaches this question in a serious and honest way, the CWO[11] defends, on the question of the fundamental causes of the economic crises of capitalism and of the decadence of this mode of production, a different analysis from the one defended in their day by Marx and Engels. They have every right to do so, and even the responsibility to do so if they consider it necessary. Whatever the depth and value of his contribution to the theory of the proletariat, Marx was not infallible and his writings should not be seen as sacred texts. The writings of Marx must also be subjected to a critique by the marxist method. This is the approach that Rosa Luxemburg adopts in The Accumulation of Capital (1913) when she brings to light the contradictions in Volume II of Capital with regard to the schemas of enlarged reproduction. This said, when you put a part of Marx's work into question, political and scientific honesty demands that you openly and explicitly take responsibility for such an approach. This is exactly what Rosa Luxemburg did in her book and it was this which provoked such hostility among the "orthodox marxists" who were so scandalised by anyone putting Marx's writings into question. Unfortunately this is not what the CWO does when it moves away from Marx's analysis while claiming to remain loyal to it, and at the same time accusing the ICC of distancing itself from materialism and thus from marxism. For our part, if we take up Marx's analyses here, it is because we consider them to be correct and because they take into account the reality of capitalism.

Thus, having examined this question on the theoretical level in the first part of this article, we are going to show how empirical reality totally invalidates the theory of those who make the evolution of the rate of profit the alpha and omega of the explanation of crises, wars and decadence. To do this, we will continue to base ourselves on the critique of Paul Mattick's analysis adopted by the IBRP, which argues that on the eve of World War I the economic crisis had reached such proportions that it could no longer be resolved through the classic means of devalorising fixed capital (i.e. bankruptcies) as it had during the 19th century, but now demanded the physical destruction that comes with war: "Under 19th century conditions it was relatively easy to overcome over-accumulation by means of crises that more or less affected all capital entities on an international scale. But at the turn of the century a point had been reached where the destruction of capital through crisis and competition was no longer sufficient to change the total capital structure towards a greater profitability. The business cycle as an instrument of accumulation had apparently come to an end; or rather, the business cycle became a cycle of world wars. Although this situation may be explained politically it was also a consequence of the capitalist accumulation process (...) The resumption of the accumulation process in the wake of a ‘strictly' economic crisis increases the general scale of production. War, too, results in the revival and increase of economic activity. In either case capital emerges more concentrated and more centralised. And this both in spite and because of the destruction of capital." (Paul Mattick as quoted in the article in Revolutionary Perspectives n°37).[12]

This is the IBRP's analysis of capitalism's entry into its phase of decadence. On this basis, the latter accuses us of idealism because we do not advance a clearly economic analysis to explain every phenomenon in society and decadence in particular: "In the materialist concept of history the social process as a whole is determined by the economic process. The contradictions of material life determine the ideological life. The ICC is asserting, in the most casual way, that an entire period of capitalism's history has ended and another has opened up. Such a major change could not occur without a fundamental change in the capitalist infrastructure. The ICC must either support its assertions with an analysis from the sphere of production or admit that they are pure conjecture." (Revolutionary Perspectives n°37). This is what we are now going to discuss.

Historical materialism and a mode of production's entry into decadence

In the belief that it is making good use of the marxist method, the IBRP has found, in the councilist Paul Mattick, the "material bases" for the opening up of capitalism's period of decadence. Unfortunately for the IBRP, if the marxist method - historical and dialectical materialism - could be summed up as looking for an economic explanation for every single phenomenon in capitalism, then, as Engels said, "the application of the theory to any period of history would be easier than the solution of a simple equation of the first degree."[13]. What the IBRP quite simply forgets here is that marxism is not just a materialist method of analysis but also a historical and dialectical one. So what does history tell us about a mode of production's entry into decadence on the economic level?

History tells us that no period of decadence has begun with an economic crisis! There is nothing surprising in this because a system at its apogee is in its period of greatest prosperity. The first manifestations of decadence can therefore only appear in a very weak manner at this level; they appear above all in other areas and on other levels. Thus, for example, before plunging into endless crises on the material level, Roman decadence first of all expressed itself in the halting of its geographical expansion in the second century AD, by the first military defeats at the edges of the Roman empire during the third century, as well as by the first simultaneous outbreak of slave revolts all over the colonies. Similarly, before getting stuck in economic crises, famines, plague and the Hundred Years War, the first signs of the decadence of the feudal mode of production appeared in the end of the land clearances for new estates in the last third of the 13th century.

In both these cases, economic crises as products of blockages in the substructure only developed well after the entry into decadence. The passage from ascendance to decadence of a mode of production on the economic level can be compared to the changing of the tides: at its highest point, the sea seems to be at its most powerful and its retreat is almost imperceptible. But when contradictions in the economic underpinnings begin to gnaw away at society at a deep level, it is the superstructural manifestations which appear first.

The same goes for capitalism: before appearing on the economic and quantitative level, decadence found expression as a qualitative phenomenon at the social, political and ideological level, through the exacerbation of conflicts within the ruling class, leading to the First World War, by the state taking control of the economy for the needs of war, through the betrayal of social democracy and the passing of the unions into the camp of capital, through the eruption of a proletariat that demonstrated its capacity to overthrow the domination of the bourgeoisie and through the introduction of the first measures aimed at the social containment of the working class.

It is thus quite logical and fully coherent with historical materialism that capitalism's entry into decadence did not express itself first of all through an economic crisis. The events which took place at this point did not yet fully express all the characteristics of its phase of decadence; they were an exacerbation of the dynamics that belonged to its ascendant period, in a context which was in the process of profound modification. It was only later on, when the blockages at the substructural level had done their work, that the economic crises now began to fully unfold. The causes of decadence and of the First World War are not to be found in a certain rate of profit or an economic crisis that was nowhere to be seen in 1913 (see below) but in a totality of economic and political causes, as explained in International Review n°67.[14] The prosperity of capitalism during the Belle Epoque was fully recognised by the revolutionary movement at the time of the Communist International (1919-28). At its First Congress, in the Report on the World Situation written by Trotsky, the CI noted that "the two decades preceding the war were a period of particularly powerful capitalist growth".

An empirical invalidation of the thesis of Mattick and the IBRP

This theoretical and empirical observation drawn from the evolution of past modes of production is fully confirmed by capitalism. Whether we examine the rate of growth, the rate of profit, or other economic parameters, there is no confirmation of the theory of Mattick and the IBRP, according to which capitalism's entry into its phase of decadence and the outbreak of the First World War was the product of an economic crisis following a fall in the rate of profit, necessitating a massive devalorisation of capital through the destruction caused by war.

The growth-rate of GNP, measured in volume by inhabitant (thus with inflation deducted) was on the rise throughout the ascendant period of capitalism, reaching a culminating point on the eve of 1914. All the figures we publish below show that the period leading up to the First World War was the most prosperous in the whole history of capitalism up to that point. This observation remains constant regardless of what indicators we use:

|

Growth in Gross World Product per inhabitant |

|

|

1800-1830 |

0,1 |

|

1830-1870 |

0,4 |

|

1870-1880 |

0,5 |

|

1880-1890 |

0,8 |

|

1890-1900 |

1,2 |

|

1900-1913 |

1,5 |

|

Source : Paul Bairoch, Mythes et paradoxes de l'histoire économique, 1994, éditions la découverte, p.21. |

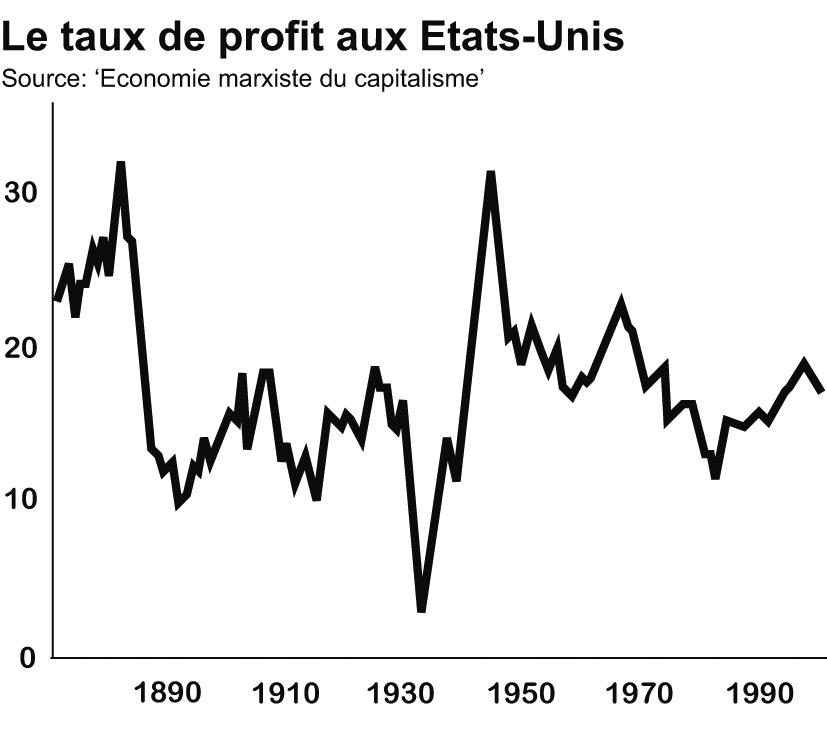

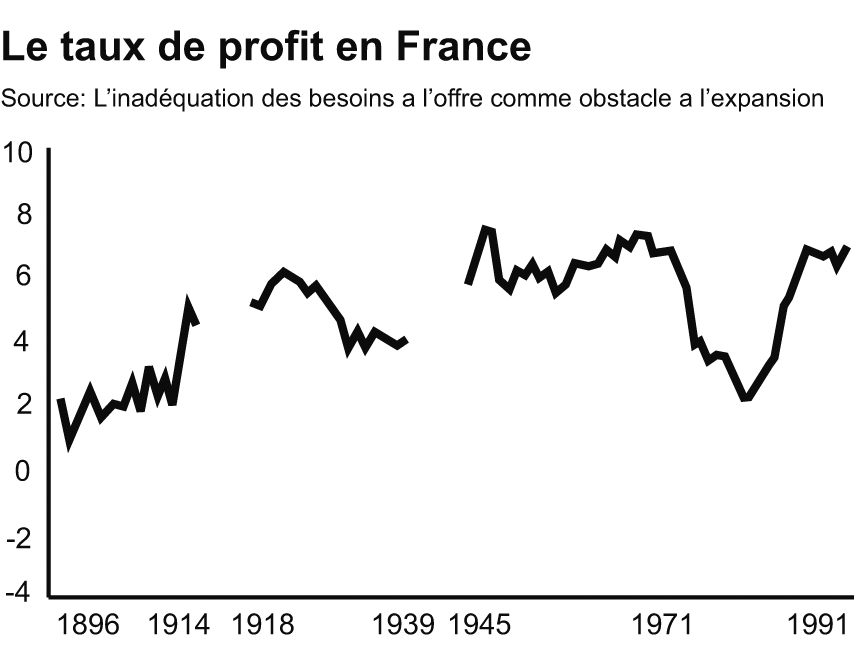

The same is true if we examine the evolution of the rate of profit, which is the variable taken into account by all those who make this question the key to understanding all the economic laws of capitalism. The graphs for the USA and France which we reproduce below also show that there is no confirmation of the theory of Mattick and the IBRP. In France, neither the level, nor the evolution of the rate of profit can in any way explain the outbreak of the First World War since the rate had been on the rise since 1896 and had been rising even more sharply from 1910 on! Nor can the rate of profit explain the USA's entry into the 1914-18 war: oscillating around 15% since 1895, it was on the rise after 1914 and reached 16% at the time the US entered the war in March-April 1917! Neither the level, nor the rate of profit on the eve of the First World War are able to explain the outbreak of the war or capitalism's entry into its phase of decadence.

|

|

Production industrielle mondiale |

Commerce mondial |

|

1786-1820 |

2,48 |

0,88 |

|

1820-1840 |

2,92 |

2,81 |

|

1840-1870 |

3,28 |

5,07 |

|

1870-1894 |

3,27 |

3,10 |

|

1894-1913 |

4,65 |

3,74 |

|

Source : W.W. Rostow, The world economy, history and prospect, 1978, University of Texas Press. |

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that the first perceptible economic signs of a turning point between ascendance and decadence did begin to emerge at this time: not at the level of the evolution of the rate of profit as Mattick and the IBRP wrongly claim, but at the level of a lack of final demand, with the appearance of the premises of a saturation of markets relative to the needs of accumulation on a world scale, as had been predicted by Engels and Rosa Luxemburg (see the first part of this article). This was also noted by the same report by the Third International cited above, which goes on to say "Having tested out the world market through their trusts, cartels and consortiums, the rulers of the world' destiny took into account that this mad growth of capitalism must run up against the limits of the world market's capacity". Thus, in the USA, after a vigorous growth over 20 years (1890-1910), during which the index of industrial activity multiplied by 2.5, the latter began to stagnate between 1910 and 1914 and only picked up in 1915 thanks to the export of military equipment to Europe. Not only did the American economy lose its dynamism on the eve of 1914, but Europe also experienced certain conjunctural difficulties linked to the limitations of world demand, and tried, more and more vainly, to turn towards external markets: "But, under the influence of the crisis that was developing in Europe, the following year (1912) saw a reversal of the conjuncture (in the USA)....Germany then went through a period of accelerated expansion. In 1913 industrial production was 32% above the 1908 level... With the internal market being incapable of absorbing such a level of production, industry turned towards external markets, with exports rising by 60% as against 41% for imports... the turn-around took place at the beginning of 1913... unemployment began to develop in 1914. The depression was mild and short-lived: a temporary recovery began in the spring of 1914. The crisis, having begun in Germany, then spread to the UK... the repercussions of the German crisis were felt in France in August 1913...In the US, it was not until the beginning of 1915 that production began to develop under the influence of war demand" (all these figures, as well as this passage, are taken from the Les crises économiques, PUF no.1295, 1993, p42-48).

These conjunctural difficulties developing on the eve of 1914 were so many precursors of what would become a permanent economic difficulty for decadent capitalism: a structural lack of solvent markets. However, it has to be said that the First World War broke out in a general climate of prosperity and not of crisis, i.e., of a continuation of the Belle Epoque: "The last years of the pre-war period, like the years 1900-1910, were particularly good ones for the three great powers who participated in the war (France, Germany and Britain). From the point of view of economic growth, the years 1909 to 1913 without doubt represented the four best years in their history. Apart from France where the year 1913 was marked by a slow-down in growth, this year was one of the best years of the century, with an annual growth rate of 4.5% in Germany, 3.4% in Britain, with France at a mere 0.6%. The bad results in France can be entirely explained by the 3.1% fall in agricultural production."[15]The war thus broke out before the beginning of a real economic crisis, almost as if the latter had been anticipated; indeed this was noted in the above-cited report from the First CI Congress: "...they tried to find a way out of this situation by a surgical method. The sanguinary crisis of the World War was intended to supersede an indefinitely long period of economic depression". This is why all the revolutionaries of the time, from Lenin to Rosa Luxemburg via Trotsky and Pannekoek, while pointing to the economic factor among the causes of the outbreak of the First World War, did not describe it as an economic crisis or a fall in the rate of profit but as the exacerbation of the previous imperialist tendencies: the continuation of the imperialist scramble to grab the remaining non-capitalist territories of the globe[16] or the dividing up of the markets and no longer the conquest of new ones.[17]

Alongside these "economic" observations, all these illustrious revolutionaries wrote at length about a series of other factors in the political, social and inter-imperialist domains. Thus, for example, Lenin insisted on the hegemonic dimension of imperialism and its consequences in the decadent phase of capitalism "(1) the fact that the world is already partitioned obliges those contemplating a redivision to reach out for every kind of territory, and (2) an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry between several great powers in the striving for hegemony, i.e., for the conquest of territory, not so much directly for themselves as to weaken the adversary and undermine his hegemony. (Belgium is particularly important for Germany as a base for operations against Britain; Britain needs Baghdad as a base for operations against Germany, etc.)". This new characteristic of imperialism underlined by Lenin is essential to understand because it meant that "the conquest of territories" in the course of inter-imperialist conflicts in decadence has less and less economic rationality but rather takes on an increasingly strategic dimension: "Belgium is particularly important for Germany as a base for operations against Britain; Britain needs Baghdad as a base for operations against Germany, etc."[18]

So while we can indeed see the first signs of economic difficulty on the eve of 1914, these remained very limited, comparable to previous cyclical crises and not at all on the scale of the long crisis which was to begin in 1929 or as deep as the current crises; at the same time they appeared not at the level of a fall in the rate of profit but of a saturation of the markets, which was to prove the defining characteristic of the decadence of capitalism on the economic level as Rosa Luxemburg predicted: "the more numerous are the countries who have developed their own capitalist industry, and the more the need for the extension and the capacity of extension of production increases on the one hand, the less the capacity for the realisation of production increases in relation to the former. If we compare the bounds made by British industry in the years 1860-70, when Britain still dominated the world market, with its growth in the last two decades, since which time Germany and the United States of America have made considerable gains on the world market at Britain's expense, it becomes clear that growth has been much slower than before. The fate of British industry thus depends on German industry, North American industry, and in the end the industry of the world. At each stage of its development, capitalist production irresistibly approaches the epoch in which it will only be able to develop with increasing slowness and difficulty."[19]

From this short empirical examination, it is clear that the First World War did not break out in the wake of a fall in the rate of profit, nor of an economic crisis as Mattick and the IBRP claim. It now remains to examine the complement to the thesis of the IBRP, i.e. to verify empirically whether the destruction resulting from war was the basis for a rediscovered ‘prosperity' in peacetime, thanks to a re-establishment of the rate of profit through the destruction caused by war.

The inter-war period disproves the IBRP's thesis

Very well, the IBRP would no doubt respond, but if the outbreak of the First World War cannot be explained either by a fall in the rate of profit nor by an economic crisis that forced capitalism to devalorise on a massive scale, devalorisation still took place during the course of the war as a result of massive destruction; and it is this which is at the basis of the economic growth and of the rise in the rate of profit after the war: "It was on the basis of this devaluation of capital and cheapening of labour power that rates of profit were increased and it was on this that the recovery period up to 1929 was based." (Revolutionary Perspectives n°37).

What really happened? Was there in fact a "devalorisation of capital" and a "devalorisation of labour power" during the war, allowing for a "reestablishment" until 1929, a reestablishment that supposedly allowed a recovery of the rate of profit following the destruction caused by war? It is empirically very easy to refute this idea of the economic rationality of the First World War since "during the First World War 35% of the accumulated wealth of mankind was destroyed" (Revolutionary Perspectives n°37); far from having "laid the basis for periods of renewed accumulation of capital" (Revolutionary Perspectives n°37) this resulted on the contrary in a stagnation of world trade during the whole inter-war period as well as the worst economic performances in the whole history of capitalism.[20]

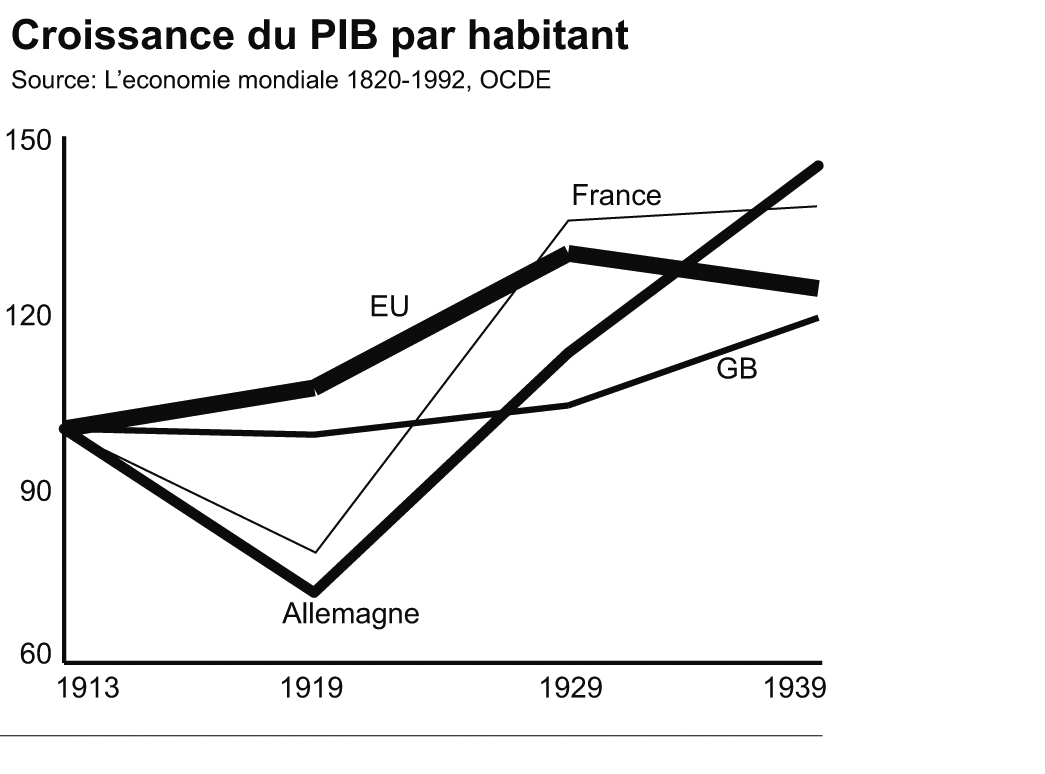

If we examine in a bit more detail the growth of GNP by inhabitant during this troubled inter-war period by taking the beginning of the period of capitalist decadence as a reference point (1913), the end of the First World War (1919), the year of the outbreak of the great crisis of the 1930s (1929) as well as the situation on the eve of the Second World War (1939), we can see the following evolution.

The very feeble growth during this whole period (in the order of plus or minus 1% only per year on average) shows that the destruction of war did not constitute a stimulant to economic activity in the way that Mattick and the IBRP claim. This table also shows that the situations were very divergent and that it was by no means the countries most involved in the war who came out best in the very short period of reconstruction and recovery between 1919 and 1929. War was certainly not good business for Britain, since it only exceeded its 1913 level by 4 points, nor for Germany with hardly 13 points! For the latter country, the strong growth during the years 1929-39 was based essentially on the arms expenditure that generalised during the 1930s, since the index of its industrial production, which was 100 in 1913 was only at 102 in 1929; whereas the proportion of military expenditure in its GNP, which was still only 0.9% in the years 1929-32, rose brutally after 1933 to 3.3% and went on growing, reaching 28% in 1938![21]

In conclusion, nothing, either theoretically, historically, and still less empirically, supports this idea of Mattick's, taken up by the IBRP, that war has such regenerative effects on the economy: "War ... results in the revival and increase of economic activity" (Revolutionary Perspectives n°37). If there is any truth in what the IBRP is saying, it is a truth proclaimed by all revolutionaries since 1914 - that the war was a catastrophe which had no precedent in human history. Not only on the economic level (more than third of the world's wealth was ruined) but also on the social level (ferocious exploitation of a labour force reduced to extreme poverty), the political level (with the treason of the great organisations of the proletariat forged so painfully over a half century of struggles - the Socialist parties and the trade unions) and on the human level (20 million soldiers killed or wounded and another 20 million dead from the Spanish flu epidemic after the war). Since nothing since then has attested to the economic rationality of war, the IBRP should reflect a bit more before attacking our view that war in the decadent phase of capitalism has become irrational "Instead of seeing war as serving an economic function for the survival of the capitalist system, it has been argued by some left communist groups, notably the Internationalist Communist Current (ICC), that wars serve no function for capitalism. Instead, wars are characterised as ‘irrational', without either short or long-term function in capitalist accumulation." (Revolutionary Perspectives n°37).

Instead of rushing to call us idealists, the IBRP would do better to take off its vulgar materialist spectacles and return to an analysis which is a bit more historical and dialectical, since a detailed examination of what the IBRP calls "the economic process" "material life", "the capitalist infrastructure", "the sphere of production" teaches us that there was no open crisis nor fall in the rate of profit before the First World War and no miraculous peacetime recovery on the basis of the destruction caused by war. We therefore invite the IBRP to verify its claims more seriously before enshrining as truth what turns out to be desire rather than reality, and before accusing others of idealism when it is itself not even capable of producing a "materialist analysis" able to give a coherent account of reality.

The falling rate of profit is not adequate for explaining crises, wars and reconstructions

If the theory of Mattick and the IBRP is not at all verified with regard to the First World War, is it not attested by other periods? Is it possible to refute this theory in general? This is what we aim to examine next.

To approach this question, we will base ourselves on two curves indicating the rate of profit in the long term with regard to the USA on the one hand and France on the other. We would of course have liked to have presented this in relation to Germany, but, despite our research, we have only been able to trace its evolution in the period after 1945 and for a few dates prior to that. Unfortunately, the lack of homogeneity in the mode of calculating for these different dates makes it difficult to analyse the process of evolution. According to the data we do have, however, with a few variations, we can consider the curve for France to be characteristic of the general evolution of the old continent.[22]

Is the level and/or the evolution of the rate of profit able to explain wars?

As we have already shown, the graph of the evolution of the rate of profit in France indicates very clearly that it does not explain the outbreak of the First World War since the rate had been growing since 1896 and had been growing even more strongly after 1910! We can now see that the same thing goes for the Second World War, since on the eve of hostilities, the level of the rate of profit of the French economy was very high (double what it was during the period of prosperity between 1896 and the First World War!) and after a fall during the 1920s, it remained stable throughout the 30s.

Moreover, if the war could be explained by the level and/or tendency for the rate of profit to fall, then it becomes impossible to understand why the Third World War did not break out during the second half of the 1970s, since the rate of profit was definitely declining from 1965 on and reached levels much lower than in 1914 and 1940 - when according to the IBRP it reached thresholds that provoked the First and Second World Wars!

As for the USA, the falling rate of profit cannot explain its entry into the First World War because it was on the rise some years before it joined the conflict. The same goes for the Second World War since the US rate of profit was recovering very vigorously during the decade preceding its entry into the war: in 1940 it got back to the level before the crisis and had reached an even higher level at the moment it entered the war.

In conclusion, contrary to the theory of Mattick and the IBRP, whether we are talking about the old continent or the new, neither the level nor the evolution of the rate of profit can explain the outbreak of the two world wars. Not only do we n see that the rate of profit was not declining on the eve of the world conflicts - for the most part it had been rising for a number of years! To say the least, this must put into question the theory of the economic rationality of war professed by the IBRP, since what rationality could there be for capitalism to go to war and undertake a massive destruction of its capital at a time when the rate of profit was soaring? Understand it if you can!

Does the level and/or the evolution of the rate of profit explain the post-war prosperity?

The dynamic towards a rising rate of profit preceded World War II, so much so that in 1940, i.e. before America entered the war, the USA had recovered the average level it had reached before the great crisis of 1929, a level which would also be the same as that of the Reconstruction boom after the Second World War. At the time it entered the war the level was even higher. From that point, neither the re-establishment of the rate of profit, nor the economic prosperity of the post-war period can be explained by the destructions caused by war. It had been the same for the previous war since the dynamic towards a recovery in the rate of profit had preceded America's engagement in the conflict, and there was no significant rise in the rate after the war. Once again, neither the level, nor the tendency of the rate of profit after the First World War can be explained by America's entry into the war.

As for France, its rate of profit did not significantly improve after the First World War because, after a tiny rise of 1% between 1920 and 1923, the rate fell by 2% during the course of the 20s and then stabilised during the 30s. Only the clearly higher rate of profit after the Second World War in comparison to the pre-war situation could give any credence - in this case, and only in this case - to the IBRP's hypothesis. We will see however in the next parts of this article that the post-war prosperity owes nothing to the destruction and other economic consequences of the war.

In conclusion, it has to be said that capital's return to profitability precedes the military conflicts and the destruction caused by the war! War and its destruction thus has little to do with the revival of the rate of profit. The idea that this destruction regenerated the rate of profit, which in turn allowed a return to prosperity after the war, are just as phantasmal as the rest of the IBRP's theory.

Can the level or evolution of the rate of profit explain the crises?

Can the level and/or the rate of profit explain the 1929 crash and the crisis of the 1930s? Contrary to what the IBRP argues, it cannot be the level of the rate of profit in the USA that explains the outbreak of the crisis since in 1929 it was higher than it had been during the two previous decades of economic growth. As for the orientation of the rate of profit, it is true that it was heading downwards just before the crisis of 1929 - both in the US and in France - but this was very limited both in intensity and in duration. Thus, in France, the fall in the rate of profit between 1973 and 1980 was much more dramatic than at the time of the crisis of 1929, without this producing consequences of the same breadth (a brutal deflation leading to a very pronounced fall in production). Although unfolding over a longer period, the same can be said for the USA, since the fall in the rate of profit between the end of the 60s and the beginning of the 80s was hardly any lower than during the crisis of 1929, without this engendering the same spectacular consequences. In both cases, the difference with the present crisis can be linked to the state capitalist measures used to artificially boost solvent demand, indicating that its the latter factor which is the decisive variable in explaining crises.

The inability of the IBRP to understand the evolution and persistence of the present crisis

The evolution of the present crisis clearly shows that the theory of crisis based solely on the evolution of the rate of profit is totally unsatisfactory. The IBRP tells us that the cycle of accumulation gets blocked or stagnates when the rate of profit becomes too low and that it can only recover following the destructions of war, which permit the devalorisation and renewal of fixed capital: "The law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall means that at certain point the cycle of accumulation is arrested or stagnates. When this happens only a massive devaluation of existing capital values can start accumulation again. In the twentieth century the two world wars were the outcomes. Today we have had thirty plus years of stagnation and the system has only limped along through the massive accumulation of debt, both public and private."[23]

But then:

a) how can the IBRP explain that the crisis persists and gets worse when the rate of profit has been rising vigorously since the beginning of the 80s and has even returned to the levels it reached during the Reconstruction? (see the graph...);

b) how can the IBRP explain that, with an analagous level of profit during the 1960s, neither productivity, nor growth, nor accumulation recovered as its theory would predict;[24]

c) how can the IBRP explain that the rate of profit was able to revive fully when we are told that this can only happen through a "massive devaluation of existing capital values"? Since the Third World War has not taken place, where is the IBRP to find this "massive devaluation of existing capital" that can account for this revival in the rate of profit?

The IBRP has attempted to answer the third question: how to explain the current spectacular rise in the rate of profit without there having been a massive devaluation following destructions caused by war?

The IBRP puts forward two arguments. The first consists of taking up the arguments which we levelled at them in our polemic in International Review n°121, i.e. that the rate of profit can rise, not only following a massive devaluation of fixed capital but also with an increase in the rate of surplus value (or rate of exploitation).[25] Now, this has very clearly been the case since the drastic austerity that has hit the working class (freezing and reduction of wages, increasing rhythm and hours of labour, etc) and makes it possible to explain this revival in the rate of profit. The second argument by the IBRP consists of substituting the destruction/devaluations of a war that hasn't taken place with the twaddle of bourgeois propaganda about the so-called new technological revolution. It would seem that the latter has the same effect: diminishing the price of fixed capital following the gains in productivity brought about by this new technological revolution. This is doubly false because gains in productivity have been stagnating in all the developed countries, demonstrating that the so-called "new technological revolution" with which the IBRP constantly assaults our ears is nothing but a copy of the propaganda coming out of the bourgeois media.[26]

With the aid of these two arguments (the rise in the rate of profit thanks to austerity, and the diminution of the value of fixed capital thanks to the new technological revolution) the IBRP thinks that it has triumphantly explained the revival of the rate of profit. Very well, but the problem remains, and it has even shot itself in the foot by aggravating its own contradictions, since:

a) Now that the IBRP recognises that there has been a rise in the rate of profit,[27] how can it explain why a new cycle of accumulation has not begun, since all the conditions for it are present: "Thus, in the expression of the rate of profit, the numerator (s) is increased while the denominator (c+v) is decreased, and the rate of profit increased. It is on the basis of the increased rate of profit that a new cycle of accumulation can be started". The persistence of the crisis then becomes a mystery.

b) Following Mattick's theory, the IBRP claims that when the rate of profit rises on the basis of a reduction in the organic composition of capital and a rise in the rate of surplus value, the crisis is reabsorbed.[28]How can the IBRP explain how the crisis has continued to get worse even when the rate of profit has continued to rise since the 1980s?

c) The whole argument of the IBRP has been that "at the turn of the century a point had been reached where the destruction of capital through crisis and competition was no longer sufficient to change the total capital structure towards a greater profitability. The business cycle as an instrument of accumulation had apparently come to an end; or rather, the business cycle became a cycle of world wars". But now we have to say that with the new explanation the IBRP is offering us, capitalism has indeed been able to boost the rate of profit without resorting to a massive devalorisation of fixed capital through war. This was also the case in the USA after 1932, i.e. ten years before this country entered the war!

d) If capitalism is going through a new technological revolution enabling it to strongly reduce the cost of fixed capital without resorting to war, and if at the same time it has notably increased its rate of surplus value, what is the difference with the ascendant phase? How can the IBRP continue to argue that capitalism is senile, since it has succeeded in reviving its profit rate without resorting to the massive destruction caused by war, which according to the IBRP is the only way of re-launching the cycle of accumulation in the decadent epoch?

e) Finally, if capitalism is going through a new technological revolution and the IBRP recognises that the rate of profit has significantly increased, why does it continue to sing the same refrain, affirming that capitalism is in crisis because the rate of profit is so low? "The crisis at the start of the 1970s is a consequence of the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall: it does not mean that capitalism stops making profits but it does mean that their average profit rates are so low" ("The Turner Plan: it's time to pension off capitalism", Revolutionary Perspectives n°38, March 2006). Again, understand it if you can! It is indeed very difficult to free yourself from a dogma and put it into question when its been your trade mark from the beginning!

All these contradictions and insoluble questions simply and purely invalidate the thesis of Mattick and the IBRP who claim that only the level and/or variation in the rate of profit can explain the crisis and its evolution. For our part, all these mysteries are obviously only comprehensible if you integrate the central thesis elaborated by Marx, i.e. "society's limited power of consumption" or the saturation of solvent markets (see the first part of this article). For us, the response is extremely clear - the rate of profit could only have increased following a rise in the rate of surplus value brought about by incessant attacks on the working class and not through a change in organic composition on the basis of an imaginary "new technological revolution". It is this lack of solvent markets which explains why today, despite the re-establishment of the rate of profit, accumulation, productivity and growth have not taken off again: "The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses, in the face of the drive of capitalist production to develop the productive forces as if only the absolute consumption capacity of society set a limit to them". This response is extremely simple and clear but it is incomprehensible to the IBRP.

This inability to understand and integrate the totality of Marx's analyses and to break away from this dogma of the crisis being caused uniquely by the falling rate of profit is one of the major obstacles to their understanding. We will examine this further in the next part of this article, by going to the roots of the divergences between Marx's analysis of crises and the pale, emasculated copy set up by the IBRP.

C Mcl.

[1] Marx, Capital, Volume III This analysis elaborated by Marx obviously has nothing to do with the underconsumptionist theory of crises, which he denounced elsewhere:"it is said that the working class receives too small a share of its own product, and that this evil could be remedied by giving it a greater share of this product, and therefore higher wages. But we need only remember that crises are always preceded precisely by a period of a general increae in wages, where the working class does indeed win a greater share of the fraction of annual capital destined for consumption. From the point of view of these knights of ‘simple' (!) common sense..." (Capital). As Marx said you would have to be very naïve to believe that the economic crisis could be resolved by an increase in wages since this could only take place to the detriment of profits and thus of productive investment.

[2] Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, part II, chapter XVII, ‘Ricardo's Theory of Accumulation and a Critique of it. The Contradiction Between the Impetuous Development of the Productive Powers and the Limitations of Consumption Leads to Over-production'.

[3] Communist Manifesto, "Bourgeois and proletarians"

[4] Marx, Capital.

[5] Marx, Grundrisse, "Chapter on Capital, Circulation Process of Capital"

[6] Marx is talking here about wage labour which is at the heart of this "antagonistic conditions of distribution" in which the class struggle regulates the division between the capitalists' tendency to extort a maximum of surplus labour and the resistance to this by the workers. It is this conflict which partly explains the natural tendency for capitalism to restrict as much as it can the amount devoted to wages in favour of the amount taken in profit, or, in other words, to increase the rate of surplus value: surplus value divided by wages can also be called the rate of exploitation: "the general tendency of capitalist production is not to elevate, but to reduce the average level of wages" (Marx, Wages, Prices and Profits).

[7] Marx, Capital, Volume III, Chapter 15

[8] Marx, Capital, Volume IV, Chapter 17, "Theories of Surplus Value"

[9] Capital, Vol III Part III, Chapter 15, "Exposition of the Internal Contradictions of the Law"

[10] Cited in the preface to the English edition of Volume I of Capital (1886)

[11] The CWO (Communist Workers Organisation) is, with Battaglia Comunista, one of the two pillars of the IBRP (International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party). We will use these initials throughout this text.

[12] Paul Mattick Marx and Keynes, Merlin, 1969 p 135.

[13] Engels, letter to J Bloch, 21 September 1890: "According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. Other than this neither Marx nor I have ever asserted. Hence if somebody [such as the IBRP - ed.] twists this into saying that the economic element is the only determining one, he transforms that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, senseless phrase. The economic situation is the basis, but the various elements of the superstructure - political forms of the class struggle and its results, to wit: constitutions established by the victorious class after a successful battle, etc., juridical forms, and even the reflexes of all these actual struggles in the brains of the participants, political, juristic, philosophical theories, religious views and their further development into systems of dogmas - also exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their form. There is an interaction of all these elements in which, amid all the endless host of accidents (that is, of things and events whose inner interconnection is so remote or so impossible of proof that we can regard it as non-existent, as negligible), the economic movement finally asserts itself as necessary. Otherwise the application of the theory to any period of history would be easier than the solution of a simple equation of the first degree....Marx and I are ourselves partly to blame for the fact that the younger people [such as the IBRP - ed.] sometimes lay more stress on the economic side than is due to it. We had to emphasise the main principle via-a-vis our adversaries, who denied it, and we had not always the time, the place or the opportunity to give their due to the other elements involved in the interaction. But when it came to presenting a section of history, that is, to making a practical application, it was a different matter and there no error was permissible. Unfortunately, however, it happens only too often that people [such as the IBRP - ed.] think they have fully understood a new theory and can apply it without more ado from the moment they have assimilated its main principles, and even those not always correctly".

[14] This analysis was clearly put forward by our organisation during its 9th Congress in 1991: "While it is clear that in the last instance imperialist war derives from the exacerbation of economic rivalries between nations, itself the result of the crisis of the capitalist mode of production, we must not make a mechanistic link between the different manifestations of the life of decadent capitalism. (...) This was already true for the First World War which did not break out as a direct result of the crisis. There was, in 1913, a certain aggravation of the economic situation but this was not especially greater than what had happened in 1900-1903 or 1907. In fact, the essential causes for the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 resided in:

a) the end of the dividing up of the world among the great capitalist powers. Here the Fashoda crisis of 1898 (where the two great colonial powers, Britain and France, found themselves face to face after conquering the bulk of Africa) was a sort of symbol of this and marked the end of the ascendant period of capitalism;

b) the completion of the military and diplomatic preparations constituting the alliances which were going to confront each other;

c) the demobilisation of the European proletariat from its class terrain faced with the threat of war (in contrast to the situation in 1912, when the Basle congress was held) and the dragooning of the class behind the flags of the bourgeoisie, made possible above all by the open treason of the majority of the leaders of social democracy, a point that was carefully verified by the main governments.

It was thus mainly political factors which, once capitalism had entered into decadence, had proved that it had reached an historic impasse, determined the actual moment for the war to break out" (pages 23 & 26)

[15] Paul Bairoch, Mythes et paradoxes de l'histoire économique, Editions la Découverte, p193.

[16] "Modern imperialism is not the prelude to the expansion of capital, as in Bauer's model; on the contrary, it is only the last chapter of its historical process of expansion; it is the period of universally sharpened world competition between the capitalist states for the last remaining non-capitalist areas on earth" (Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital - an Anti-critique ‘Imperialism'); "this live, unhampered imperialism, (Germany) coming upon the world stage at a time when the world was practically divided up, with gigantic appetites, soon became an irresponsible factor of general unrest" (Rosa Luxemburg, Junius Pamphlet, Chapter 3).

[17] "Thanks to her colonies, Great Britain has increased the length of ‘her' railways by 100,000 kilometres, four times as much as Germany. And yet, it is well known that the development of productive forces in Germany, and especially the development of the coal and iron industries, has been incomparably more rapid during this period than in Britain - not to speak of France and Russia. In 1892, Germany produced 4.9 million tons of pig-iron and Great Britain produced 6.8million tons; in 1912, Germany produced 17.6 million tons and Great Britain 9 million tons. Germany, therefore, had an overwhelming superiority over Britain in this respect. The question is: what means other than war could there be under capitalism to overcome the disparity between the development of productive forces and the accumulation of capital on the one side, and the division of colonies and spheres of influence for capitalism on the other? (...) 5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest powers is completed. Imperialism is capitalism at that stage of development at which ... the division of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalist powers has been completed." (Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, Complete Works Vol. 22, VII ‘Imperialism, as a special stage of capitalism' p266-267, p275-276)

[18] This takes us back to the polemic that we have had with the IBRP over the numerous wars in the Middle East. The IBRP argues that these conflicts have an economic rationality from the American point of view, since the latter aims to defend its oil rents, whereas we have opposed to this Lenin's thesis by showing that the ‘conquest of Iraqi territory' was done not so much for its own sake but to weaken Europe and sap its power and influence. The obvious fact that this conflict has been a bottomless pit for the USA, in which they will never get any serious income from oil because they are totally incapable of controlling the territory and would now like to get out of it, shows how correct Lenin's analytical framework is.

[19] Introduction a l'economie politique, edition 10/18, p 298-299

[20] For world trade: 0.12% between 1913-1938, or in other words 25 time less than between 1870-1893 (3.10%) and 30 times less than between 1893-1913 (3.74%) ( W W Rostow, 1978, The World Economy, History and Prospects, University of Texas Press). The world growth of GNP per inhabitant would only be 0.91% during the period 1913-50 as against 1.30% between 1870 and 1913 - i.e. 43% more; 2.93% between 1950 and 1973 - i.e. three times more - and 1.33% between 1973 and 1998, i.e. 43% more during this long period of crisis (Maddison Angus, L'Economie Mondiale, 2001, OECD)

[21] This was also partly the case for Japan, where the percentage was only 1.6% in 1933 to reach 9.9% in 1938. On the other hand it was not the case for the USA where the percentage was only 1.3% in 1938 (all theses figures are taken from Paul Bairoch, Victoires et deboires III, Folio, p 88-89)

[22] It would be most inappropriate for the IBRP to reply that its theory only applies to Germany, the country which declared war, since, on the one hand, it is up to the IBRP to provide us with the empirical proof, and, on the other hand, this would be in total contradiction with the whole argument of the IBRP which deals with the worldwide roots of the 1914-18 war and the entry of capitalism into decadence (also, it talks indifferently about Europe or the US in its article). Its argumentation - and this is quite logical - has never been located at the national level alone. Furthermore, even supposing that the rate of profit in Germany was falling on the eve of the First World War and rose afterwards, the problem would still remain, because how can we explain the entry of capitalism into its phase of decadence at the world level when the fall in the rate of profit can only be verified in one country?

[23] www.ibrp.org/english/aurora/10/make_poverty_history_make_capitalism_history

[24] cf the graph for France as well as the one published in the International Review n°121 for all the G8 countries. Both show a similar evolution, i.e. a very clear divorce between a rising rate of profit and a fall in all other economic variables

[25] "the crisis itself however serves to re-establish the correct proportion between the elements of capital and allow reproduction to restart. It does this in two principal ways, the devaluation of constant capital and increasing the rate of surplus value or the ratio s/v"

[26] We can see that increases in productivity have remained at a very weak level by looking at the graph for France as well as the graph for the countries of the G8 (the eight most important economies in the world) published in International Review n°121. In reality, only the US has seen any kind of increase in productivity but explaining this conjunctural rise would take us outside the framework of this article.

[27] This recognition is in reality very partial - the IBRP just pays it lip service, when you consider that the rate of profit has been rising vigorously and continuously since the beginning of the 1980s, and that from then on it reached heights comparable with the 1960s.

[28] "In theory, according to Marx, a sufficient increase of surplus value will change a period of capital stagnation into one of expansion", Paul Mattick, Marx and Keynes, p92, or again, "in the world at large and in each nation separately, there is overproduction only because the level of exploitation is insufficient. For this reason, overproduction is overcome by an increase in exploitation - provided, of course, that the increase is large enough to expand and extend capital and thereby increase the market demand" (ibid, p82). Unfortunately for Mattick, the configuration of capitalism since 1980 (but also between 1932 and the Second World War) delivers a striking refutation of his theories since despite a very strong increase in exploitation, there has not been a revival in the expansion of capital and of market demand.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace