Submitted by International Review on

“It not only contains oil and gas resources strategically located near large energy-consuming countries but also is the world's second busiest international sea lane that links North-East Asia and the Western Pacific to the Indian Ocean and the Middle East, traversing the South China Sea. More than half of the world's shipping tonnage sails through the South China Sea each year. Over 80% of the oil for Japan, South Korea and Taiwan flows though the area.

Jose Almonte, former national security adviser to the Philippine government, is blunt about the strategic importance of the area: The great power that controls the South China Sea will dominate both archipelagic and peninsular Southeast Asia and play a decisive role in the future of the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean – together with their strategic sea lanes to and from the oil fields of the Middle East.”1

The South China Sea is not only a vital shipping lane, it is also estimated to be rich in oil, natural gas, precious raw materials and fisheries whose rights of exploitation have not been agreed. These military-strategic, economic factors create an explosive mixture.

The South China Sea is not only a vital shipping lane, it is also estimated to be rich in oil, natural gas, precious raw materials and fisheries whose rights of exploitation have not been agreed. These military-strategic, economic factors create an explosive mixture.

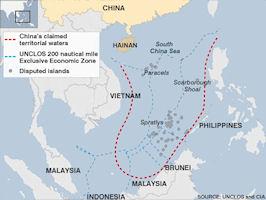

The conflicts between the littoral states over the domination in this zone is not new. In 1978 Vietnam and China clashed over the control of the Spratly islands (Vietnam, which was supported by Moscow at the time, claimed the Spratly islands for itself, the Chinese leader Deng Tsiao Ping warned Moscow that China was prepared for a full-scale war against the USSR). China's more aggressive stand took another turn after 1991 when China took the first steps to fill the power vacuum created by the withdrawal of US forces from the Philippines in 1991. China revived its "historical" claims to all the islets, including the Paracel and Spratly archipelagos, and 80% of the 3.5 million km2 body of water along a nine-dotted U-shaped line, notwithstanding a complete absence of international legal justification. Despite negotiations no resolution has been forthcoming over the two large island groups—the Paracels (or Xisha and Zhongsha), over which China clashed again with Vietnam in 1988 and 1992. The islets can be used as air and sea bases for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance activities, and as base points for claiming the deeper part of the South China Sea for Chinese missile submarines and other vessels. China is reported to be building an land-sea missile base in southern China’s Guangdong Province, with missiles capable of reaching the Philippines and Vietnam. The base is regarded as an effort to enforce China’s territorial claims to vast areas of the South China Sea claimed by neighbouring countries, and to confront American aircraft carriers that now patrol the area unmolested. China has even declared the zone as “a core interest” - raising it to the same level of significance as Tibet and Taiwan.

The SCS is the most fragile, the most unstable zone because China does not compete with just one big rival. It faces a number of smaller and weaker countries – Vietnam, Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia – all of which are too small to defend themselves alone. As a result all the neighbouring countries have to look for help from a bigger ally. This means first and foremost the USA, but also Japan and India which have offered these states their “protection”. The latter two countries have participated in a number of manoeuvres in the area, for example with Vietnam and Singapore.

A main focus of the arms race which has been triggered in Asia can be seen in the SCS countries. Although Vietnam does not have the military and financial means to go toe-to-toe with China, it has been purchasing weapons from European and Russian companies – including submarines. Arms imports are on the rise in Malaysia. Between 2005 and 2009 the country increased its arms imports sevenfold in comparison to the preceding five year period. The tiny city-state of Singapore, which plans to acquire two submarines, is now among the world's top 10 arms importers. Australia plans to spend as much as $279 billion over the next 20 years on new subs, destroyers and fighter planes. Indonesia wants to acquire long-range missiles and purchase 100 German tanks. The Philippines are spending almost $1 billion on new aircraft and radar. China has about 62 submarines now and is expected to add 15 in coming years. India, South Korea and Vietnam are expected to get six more submarines apiece by 2020. Australia plans to add 12 over the next 20 years. Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia are each adding two. Together, the moves constitute one of the largest build-ups of submarines since the early years of the Cold War. Asian nations are expected to buy as many as 111 submarines over the next 20 years.2

2 (www.wsj.com - February 12,2011)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace