Submitted by ICConline on

ICC Day of Discussion, 23 June 2012-07-25

This is a summary of the discussion that took place after the presentation on art. The full version of this can be found here: https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201206/4977/notes-toward-history-art-ascendant-and-decadent-capitalism

Presentation

The presentation introduced the online text and summarised its main points.

Art and culture are closely related to the widening discussions in the ICC on questions of ethics, science, etc., and in particular to the deepening of our understanding of decadence. The effect of decadence on art and culture tells us more about the nature and evolution of decadence.

The text started as a personal attempt to understand modern art. It doesn’t answer questions on ‘what is art?’, the role of art, or art in previous class societies. It also became clear that artistic movements cannot be defined or judged in the same way as political movements.

Bourgeois art history is completely mystified about modern art ‘modernism’ because it lacks an understanding of decadence – the key piece of the puzzle. It’s necessary to go back to Marx and Engels and particularly Trotsky who is an important point of departure on art in decadence.

A summary of key points from the text:

- Bourgeois modern art comes very late in capitalism, c 1870s. Impressionism emerges only c 30 years before onset of decadence.

- Trotsky says that art is the most ‘sensitive’ and ‘vulnerable’, part of culture, and it therefore acts as a ‘weather vane’ or harbinger of decadence.

- The onset of decadence can be seen early in art, eg. Munch’s ‘The Scream’ (used on the Decadence pamphlet cover), 1893.

- Artistic movements pre-1914 (post-impressionism, cubism, expressionism) are ambivalent, containing both progressive and reactionary elements.

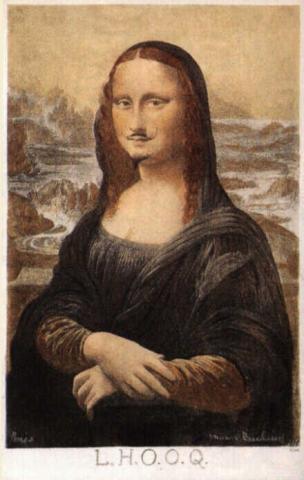

- Dada is an early response to war and decadence (1915). It veers towards anarchism – wants to demolish culture and abolish art.

- Once the proletariat moves, then art moves towards it. Despite the ‘avant garde’ in art, it’s the proletariat which is the dynamic factor (especially in Germany and Russia).

- Situationists identify the 1920s as the ‘end of modern art’, eg. James Joyce Finnigan’s Wake, Malevich’s ‘White square on a white background’ – representing a breakdown of traditional forms of bourgeois art.

- Russia is the highest point of modern art - artists are involved with the revolution, abandoning ‘pure’ art to work in industrial production to transform the lives of the exploited.

- But the revolution is defeated. Stalinism = socialist realism. All further art tends to reflect decadence – ‘development as decay’ (Marx) – the development of art is a good illustration of decadence.

- In 68, there are radical art movements but not as significant as you might expect. Recuperated. The Situationists say it’s all a spectacle. Can there be a future revolutionary art?

- The Dadaists are wrong to abolish all art and start again. The proletariat needs to appropriate the best of bourgeois culture and that of earlier times – eg. the Renaissance. What is there in decadence to build on? (Shouts of surrealism, jazz ‘death metal’!)

Discussion

The discussion recognised that this can only be an introduction to the subject but underlined the importance of art and literature to the workers’ movement. Art enhances the appreciation of life, eg. the cave paintings of Lascaux. It is the externalisation of our inner life, our humanity.

We need to go back to the beginning to revive the Marxist view of art, as with religion. The Second International was able to devote more time to this but its work is not easily available. With the revolutionary wave and decadence and the ensuing fragmentation revolutionaries have not had the time to devote to the question. It has taken the ICC time to get round to these questions.

Some of the limitations of the text were highlighted, eg. it doesn’t mention female artists or folk art or art outside Europe. Art is a global historical phenomenon. We also need to recognise that the activity of ‘artists’ in class society is based on the suppression of the ability of others.

There is no such thing as Marxist art or ‘socialist realism’. Marxism provides an historical framework for understanding the different phases of artistic expression and critical judgement of artistic representation.

Decadence is not a total halt to the ‘creative forces’, eg. James Joyce’s Ulysses was important for the development of literature. Artistic creativity didn’t die in decadence but it changes the historical context it takes place in.

Can we talk of ‘bourgeois art’? What makes it bourgeois? There is no corresponding ‘proletarian art’. Also, can we generalise about the meaning of individual artistic works or do they remain personal? eg. Munch’s ‘Scream’.

‘Retro’ popular culture is a symptom of culture in decadence. Historically this was also a sign of the onset of decadence, eg. Russia in 1905, harking back to an earlier, more stable and comforting epoch, at the same time as experiments in theatre flowered in the revolution.

Since the beginning of 20thc the visual arts have been regurgitating Dada. There has been very little new since then; even progressive developments like Surrealism could only have come from Dada. Surrealism is arguably the most significant artistic development in decadence, owing a huge debt to Dada. It tried to develop a theoretical understanding of art and human revolution taking on Marxism and psychoanalysis but this was unachievable with the revolution in decline.

We need to understand the extent of state control of art in decadence and its complete commodification, not just by fascism and Stalinism: it was most pernicious in the west – eg USA and the rise of cinema, with funding of different art movements as a tool of imperialism.

Cultural developments are related to massive social struggles, eg in the 60s music was a harbinger of the class struggle but the connection is not mechanical.

‘Postmodernism’ seems to be acknowledgement by bourgeois academia that they have run out of ideas – everything is just another story. But this also gives people liberty to do anything as nothing matters any more.

The working class is arguably the driving force of art in last 1-200 years but it is hijacked by bourgeoisie, eg. hip hop. The split between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art leads to a kind of workerism which rejects certain forms of art, eg. opera.

Capitalism has the technological capability to create new forms of art but it also means the legal fetters of copyright to ‘own’ and therefore restrict access to it, ie. a form of censorship.

The summing up accepted the point that there is no ‘bourgeois modern art’ but rather ‘modern art movements in bourgeois society’. The best tendencies in art always tends to go beyond the limitations of the ideology of the society where they emerge.

The text does not pretend to be a history of global art but we need to understand the most advanced tendencies in the capitalist system, which are clearest in the heartlands of Europe and USA.

While movements like jazz, Bauhaus etc., have their roots in the revolutionary wave, art in the post-war period is much more characterised by decadence. Munch’s ‘The Scream’ illustrates the point that while the subject matter may be personal, the expression of alienation as a valid subject for art was a sign of the onset of decadence.

The discussion has only begun. There is a lot more to say about the culture industry and the way capitalism developed after the post-war boom - Adorno and others have written a huge amount on this. The capitalist state’s ideological apparatus has a huge effect on cultural production. Finally, we have not really said anything about art in the specific phase of decomposition.

MH 7/12

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace