Submitted by International Review on

The ravages of the international recession

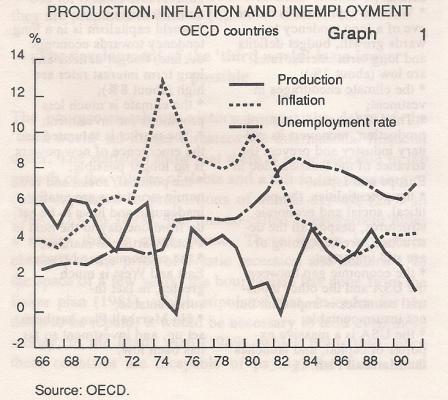

After the recessions of 1967, 71, 75 and 82, in 1986 capitalism again started to slow down. But like a dying animal, it had one last moment of respite: the brutal fall in oil prices along with a massive resort to credit (Table 1) allowed it to hold back the downward plunge in growth. But today the cruel reality of the open recession, which has been put off briefly, has returned with a vengeance: we are seeing a rise in both inflation and unemployment and a fall in growth rates (Graph 1).

|

Table 1: Debt

|

1980

|

|

1990

|

|

|

||||

|

|

Mil$

|

%GNP

|

|

Mil$

|

%GNP

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total public

|

1250

|

46%

|

|

4050

|

76%

|

|

|

|

|

|

Business

|

829

|

30%

|

(1)

|

2100

|

40%

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consumer

|

1300

|

48%

|

(2)

|

3000

|

57%

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total internal

|

3400

|

124%

|

|

9150

|

173%

|

|

|

|

|

|

Debt external

|

+181

|

|

|

-800

|

15%

|

|

|

|

|

|

GNP

|

2732

|

|

|

5300

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) 4 times their cash flow (ie company savings, used to self-finance investments)

(2) In 1989, consumer debt represented 89% of their income.

|

|||||||||

|

Public debt (% of GNP)

|

1973

|

1986

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

USA

|

39.9%

|

56.2%

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Canada

|

45.6%

|

68.8%

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

France

|

25.4%

|

36.9%

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Italy

|

52.7%

|

88.9%

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Japan

|

30.9%

|

90.9%

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Germany

|

18.6%

|

41.1%

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Spain

|

13.8%

|

49.0%

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

The USA, which spearheaded the artificial revival of the 80s, has been the first to enter into recession. The GNP has begun to go backwards: +1.4%, -1.6% and -2.8% respectively for the third and fourth quarters of 1990 and the first quarter of 1991. The other big industrialized countries have either joined the USA or have seen a considerable slow-down in growth rates. But the situation is far more catastrophic in other parts of the planet.

On the one hand, there has been a real fall in production in the Eastern countries (Table 2), where the opening of the Iron Curtain, far from constituting a new field of accumulation for capitalism, has further accelerated the crisis (see the article ‘The USSR in Pieces’ in this issue). Meanwhile the debts of the ‘third world’, despite numerous rescheduling and readjustments, continue to grow (Table 3). South America, a sub-continent that was promised a bright future, is sinking into a terrible recession: its GNP hardly grew by +0.9% in 1989 and went down to -0.8% in 1990. Expressed in term of income per head, its revenues fell to their 1978 level. And we won’t even mention Africa, which is really in the pits. With a population of 500 million, its gross product is equal to that of Belgium with 10 million inhabitants.

|

Table 2

Eastern Countries

|

Inflation

|

Evolution of GNP

|

|

|

|

|

1991

|

1989

|

1990(1)

|

|

|

Bulgarie

|

70%

|

-1.5%

|

-12.0%

|

|

|

Hongrie

|

35%

|

-1.8%

|

-4.5%

|

|

|

Pologne

|

60%

|

-0.5%

|

-12.0%

|

|

|

RDA

|

|

|

-18.0%

|

|

|

Roumanie

|

150%

|

-7.0%

|

-12.0%

|

|

|

Tchecoslovaquie

|

50%

|

+1.7%

|

-4.5%

|

|

|

URSS

|

|

|

-4.5%

|

|

|

Yougoslavie

|

120%

|

+0.8%

|

|

|

|

(1) Estimation de la Commission economique pour r’Europe de ronu

|

|

Table 3

Third World

Debt

(in millions of dollars)

|

|

|

|

|

1980

|

485

|

|

|

1983

|

711

|

|

|

1989

|

1117

|

|

|

1990

|

1184

|

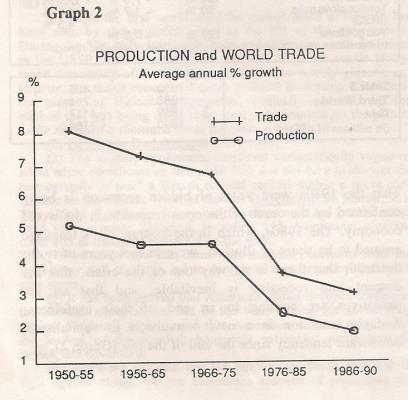

That the 1980s were years of hidden recession[1] are being confirmed by the onset of the open recession in the world economy. The 1980s, which in the bourgeoisie’s language seemed to be years of illusion, were in fact years of truth: the truth that there is no way out of the crisis, that the descent into recession is inevitable, and that all the palliatives are coming to an end of their usefulness. Today’s recession is a new convulsion in capitalism’s downward tendency since the end of the 60s (Graph 2).

Lies about an imminent recovery

If the bourgeoisie does sometimes recognize the reality of the recession, it immediately minimizes it and announces that there’ll be a recovery any minute. The development of credit, the fall in interest rates, German unification, the opening up of the Eastern countries, the reconstruction and economic development of the countries of the Middle East, the arms economy or the end of the war have been invoked one after the other to ease the disquiet in the working class. What is the real situation?

Can the war give a boost to the American economy like the Korean War did?

The Gulf war and the growth in military expenditure since the 1970s can only aggravate the crisis because the economic context is very different from the one after the Second World War:

|

Korean War (1951-52)

* The war took place on the eve of a period of prosperity and reconstruction;

* The USA was in a phase of economic recovery;

* Long term interest rates stood at 2%, the international financial system was stable, and this facilitated investment;

* The budget deficit was low, and made Keynesian policies a possibility.

|

Gulf War (1991)

* The conflict has broken out after 20 years of crisis and in the midst of a period of slowing growth;

* The USA is in a phase of economic recession;

* Inflation is at 6.3% and long term interest rates are 8%, in the context of a very fragile international monetary system; this discourages investment in favor of speculation;

* The budget deficit is colossal, and makes Keynesian policies less and less a possibility; it also prevents a return to the policy of massive rearmament adopted in the 80s.

|

As for the ending of the war, it can only aggravate the crisis whatever the bourgeoisie says. The weight of war costs on the budget deficit and the feeble economic benefits of the war are proof of this[2].

Germany and the East: new markets?

Germany has to face up on the cost of reunification, of the Gulf war and of aid to Eastern Europe aimed at holding back the tide of chaos at its gates. Economically, the ex-GDR is a ruin of little interest. In fact, the idea of putting it back on its feet is a trick, an illusion consciously constructed by the bourgeoisie; to use the terms of the governor of the Bundesbank, reunification is a “veritable economic disaster”[3]. The other illusion kept up by the bourgeoisie, and which has taken in several groups of the political milieu, is the idea of a possible rejuvenation of capitalism following the fall of the Berlin Wall. The comparison has often been made between the situation in the West after World War II, and that in the East today (end of the war economy, Marshall Plan for reconstruction …). But the global context is radically different. The eastern countries are already heavily in debt; new credits have been used essentially to service existing debt rather than to invest. Hyperinflation, insolvency, a succession of anti-crisis plans, devaluation and alterations in the currency, the development of the black market – this has become the common lot of these countries, which are heading towards a ‘third world’ situation[4]. Even in Hungary, the country most open to the West, “there has not to date been any real influx of foreign capital” admits Gyorgy Matolcsy, secretary of state responsible for the government’s economic policy. If nobody wants to buy companies in the ex-GDR, which were the eastern bloc’s best performers and which are supported by West German money, then there will not be a rush to buy and modernize them in other countries! It’s also significant that the BERD[5], given the lack of any interesting investments, has reoriented its activities towards the service sector, especially the institutional councils whose job is to modify legislation in the East. And given the very low purchasing power, the East is not at all a solvent market.

|

The West after World War 2

* tendency towards political stability, governments of national unity, consensus over the higher national interest, dominance of centralizing tendencies;

* Western capitalism is on the eve of a long tendency towards growth, budget deficits and long-term interest rates are low (about 2%);

* the climate encourages investment;

* the USA can sell its surplus production, reconvert its military industry and prevent the advance of the Russian bloc in Europe and Japan

* the potentialities, the political, social and economic structures, despite all the destruction, are kept going or are still important;

* the economic gap between the USA and other industrial countries is important but not insurmountable;

* the USA is a massive exporter of capital, and launches the Marshall Plan.

|

The East Today

* a tendency towards political instability, return to particular interests, calling into question of national unity; centrifugal tendencies are dominant; unfavorable context for economic transition;

* world capitalism is in a long tendency towards economic decline, budget deficits and long term interest rates are high (about 8%);

* the climate is much less propitious for investment;

* the market is saturated and the emergence of new powers is no longer possible;

* the political, social and economic structures are totally inadequate and have to be set up from one day to the next in a totally artificial manner;

* the economic gap between East and West is much greater, in fact insurmountable;

* no Marshall Plan has been set up, and investment so far has been low.

|

Can the Middle East constitute a market that will serve to relaunch the world economy?

The war has bled the economies of the Gulf dry, removing any possibility of a world economic revival thanks to the miracle of petrodollars or the development of economic activity in the region:

* the coppers of the Gulf states are empty; and in these rentier economies, it’s the state which is the main motor of economic life;

* the price of oil has fallen to where it was before the Gulf war, and the revival of production in Kuwait and Iraq threaten to make it fall again;

* the costs of the war for Saudi Arabia have reached the colossal sum of 64 billion dollars, and, for the first time, the country has had to borrow 3.5 billion dollars on the world’s capital markets; Kuwait will have to live on the reserves of Iraq, which before the war possessed a fund of 80 billion dollars; today it owes 100 billion;

* fear of the conflict resulted in 60 billion dollars flowing out of the Gulf and being placed elsewhere.

The policies which made it possible to support world growth in the 80s are no longer viable

The USA stands at the crossroads; it must reduce interest rates[6] if it is to avoid the recession, but these risks provoking a flight of the foreign capital which finances its deficits[7], and also threatens to bring about new surge of inflation. Along with drops in interest rates, the Federal Reserve has also lowered banking reserve limits, in order to encourage lending. In short, this is a renewal of the flight into debt, whose chances of altering the direction of the economy seem slim indeed, while they will at the same time make its contradictions even more explosive. The bourgeoisie is once again trying to get the economic machine moving, but these remedies, so powerful in the past, are today being shown to be totally ineffective: the machine, now completely overloaded, respond less and less to the commands. For example, the American banks, drowning in debt, riddled with failures, are delaying the effects of the lowering of the cost of credit on market rates, and are being drastically selective in their choice of clients they are prepared to lend to[8].

The development of the ‘third world’ is no longer possible

The bourgeoisie shouts victory because the debts of the ‘third world’ no longer threaten the international financial order. The statistics show that there is some decrease in the growth of the volume of debts and a fall in the servicing of dents expressed in proportions of annual exports (28% in 1988, 22% in 1998). But this so-called improvement hides a reality that is much worse. These figures have been obtained at the price of drastic recession and austerity. In the space of a few years, the bourgeoisie has gone from the Baker plan (1985), which stipulated that, in order for the debts to be repaid, it would be necessary to lend even more money, to the Brady plan (1989), which holds that, since these countries are incapable of paying, the banks must cancel part of their credits. And since this has mainly affected the influx of new capital, the chances of any economic development have been put off indefinitely. This is the final nail in the coffin of any illusion in reviving the world economy by handing out credits to the ‘third world’. What’s more, since 1983, the net transfer of capital has gone in the other direction: there is no more money going out of the under-developed countries towards developed ones (170 billion dollars between 1983 and 1989) than money going in. high interest rates, the relative fall in the price of raw materials and the international recession can only further aggravate this situation.

The 1990 UNICEF report estimates that each year 500,000 children die as a result of debt and austerity programs imposed by the IMF on the ‘third world’ countries; that every day 40,000 children die of hunger. Unequal economic relations, the weight of debt, the maintaining of raw material prices at ridiculously low level, the closure of western markets – all this leads to a genocide that is the equivalent of dropping a Hiroshima-sized atomic bomb every two days. This year, 27 million human beings face death through famine in Africa, a third of the active population in the eastern countries will be made unemployed, while in the central countries the working class is being subjected to unprecedented austerity measures, and whole sectors of it are falling into absolute poverty[9]: one child out of eight suffers from hunger in the USA and a seventh of the EEC’s population lives below poverty line. Massive epidemics (such as cholera in South America, in Iraq and in Bangladesh) are decimating a huge part of the labor force. Such a nightmarish balance-sheet is a wholesale condemnation of this barbarous system and demands its overthrow in favor of a society without classes. GA

[1] Concerning the so-called prosperity of the 80s, we said (in IR 59, 4th quarter of 1989) that we should beware of relying on “the raw figures for growth in production, without considering what it consisted of, nor who was to pay for it”, and the report concludes: “In the final analysis, for years a large part of world production has been not sold but simply given away. This production which may indeed correspond to commodities that have really been produced, is not the production of value, which in the end is the only thing that interest capitalism. It has not made possible a real accumulation of capital. Capital has been reproduced on an ever narrower foundation. Taken as a whole, capital has not become richer, but on the contrary poorer.”

[2] The bubble of the ‘market of the century’ has already burst: Kuwait is already revising its estimates of reconstruction costs downwards, from $40-50 billion to $10-30 billion.

[3] Up till now, only 455 firms out of the 4500 to be privatized have been bought up , just over one tenth.

[4] We are already seeing a real process of ‘third world-shaking’:

- privatization of the ex-GDR is not launching production: 70.3% of investment has gone towards setting up a distribution network;

- in Poland, a country which has been more transformed than any other, it’s the sectors lowest value which have resisted the best; this country, like the other eastern countries, is going to confined to the production of raw materials or to the production of cheap goods requiring a large and low paid workforce;

- the conditions offered at the level of the autonomy of management or of the repatriation of profits will prevent any real local economic benefits accruing.

[5] THE Bank for Reconstruction in the East

[6] The US lending rate went from 7% to 5.5% between December 1990 and April 1991. This succession of reductions shows the growing pessimism of the American authorities on any quick recovery for the economy.

[7] Already capital is tending to quit the USA to invest in Germany and Japan. In August 1990, of the 32 billion dollars put into circulation by the state, only 10% was bought up by the Japanese, whereas in the past they would usually account for one third. Because of this, US rates cannot be kept so low for very long.

[8] At present the gap between the lending rate and the base rate offered by the banks is very high: 3%.

[9] According to an enquiry conducted by the University of Bristol, 5.5 million Britons lived in poverty in 1984 (the defining criterion was absence of both bed, toilet, and fridge). Today, they number 11 million: 18% of the population, almost 1 person in every 5. Ten million people live in unheated houses, and 5 million only one have one meal a day.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace